Abstract

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3β) is a serine/threonine kinase implicated in various diseases such as Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and cancer, making it a pivotal therapeutic target. This study uniquely integrates a curated phytochemical library with comprehensive ADMET filtering and 200 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to identify stable GSK-3β inhibitors, offering deeper mechanistic and dynamic insights than previous docking-based studies. ADMET profiling shortlisted 49 compounds, with uzarigenin, jatrophone, chrysin, and podolide exhibiting superior binding affinities compared to Tideglusib (-8.53 kcal/mol). Among these, jatrophone displayed the highest binding affinity (9.00 kcal/mol), followed by uzarigenin (8.63 kcal/mol) and podolide (8.60 kcal/mol), indicating stronger interactions with GSK-3β. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed stability for uzarigenin and podolide over 200 nanoseconds, supported by RMSD, SASA, and Rg analyses. Principal component and covariance analyses revealed strong residue interactions in these complexes. KEGG pathway analysis highlighted the role of GSK-3β inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease, Wnt signaling, and cancer pathways. This study identifies phytochemicals with potential therapeutic applications for neurodegenerative, cancer, and metabolic diseases, warranting further experimental validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) is a largely conserved serine/threonine protein kinase integral to regulating various cellular processes, playing a vital part in the collaboration of both catabolic and anabolic pathways. It has two functionally distinct isoforms, α and β, originally discovered in the environment of glycogen metabolism1,2,3. Over time, GSK-3 has surfaced as a ubiquitous controller of multiple signaling pathways. The phosphorylation of tyrosine and serine regulates the activity of the GSK-3β enzyme. Phosphorylation of tyrosine activates the enzyme, while phosphorylation of serine inhibits it. There have been reports of around 100 proteins targeted for phosphorylation by GSK-3β. Among the myriad molecular targets explored for cancer treatment, GSK-3β has surfaced as a promising target due to its multifaceted role in cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation4,5,6,7. Dysregulation of GSK-3β has been intertwined with the pathogenesis of several cancers, making it an implicit target for remedial intervention8.

GSK-3β is intertwined in various conditions through its regulation of metabolism, cell cycle, and gene expression9. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), GSK-3β phosphorylates tau protein, leading to neurofibrillary tangles, and promotes amyloid-β production via amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing10. In cancer, GSK-3β modulates cell proliferation and apoptosis, with its deregulation contributing to tumor genesis through the WNT/β-catenin pathway11. In diabetes, GSK-3β's overactivity disrupts insulin signaling, thus causing insulin resistance. GSK-3β influences inflammation and vulnerable responses, impacting rheumatoid arthritis and habitual seditious conditions12. It also plays a part in mood disorders like bipolar disorder and depression, where interventions like lithium show remedial efficacy13. GSK-3β's influence extends beyond the excrescence cell natural pathways, impacting the excrescence medium and vulnerable response modulation14. The kinase plays a vital part in regulating vulnerable cell functions, including those of T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells, which are essential factors of the antitumor immune response15.

Inhibition of GSK-3β has shown implicit not only in suppressing excrescence growth but also in enhancing antitumor efficacy, thereby furnishing a binary medium of action for cancer therapy11. The activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway leads to the phosphorylation of GSK-3β at specific inhibitory serine residues9. This phosphorylation can activate various transcription factors that play roles in cancer development. Examples of these transcription factors include activating protein-1 (AP-1), cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element-binding protein (CREB), β-catenin, c-Myc, and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB)16,17. Additionally, various upstream proteins can inactivate GSK-3β18. These proteins include P70S6 kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (MAPKAP kinase-1), protein kinase C (PKC), and cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA). Each of these nonsupervisory kinases can impact the activity of GSK-3β19. CREB DNA-binding activity is inhibited by GSK-3β and facilitated by lithium. The distribution of GSK-3β within the cell can impact these kinases, while scaffolding proteins can limit relations between GSK-3β and these kinases, thereby regulating their activities.

Phosphorylation of GSK-3β at the tyrosine point (Tyr 134, 140, 216, 221, etc.) is controlled by several kinases. These include the calcium-dependent tyrosine kinase, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2(PYK2), cAMP-actuated protein tyrosine kinase, Zaphod kinase 1 (ZAK1), and Fyn17. The phosphorylation of GSK-3β at the Tyr point is also regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK1/2)20. Computational studies, including molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, give precious insight into the list relations and stability of implicit impediments. These in silico approaches grease the rapid-fire webbing of large emulsion libraries, vaticination of medicine efficacy, and optimization of pharmacokinetic parcels, significantly accelerating the development of new GSK- 3β impediments21,22. Recent in silico studies have demonstrated the power of computational tools in predicting the structural and functional effects of disease-related mutations and drug interactions. For example, mutations in PI3KCA, PLK1, and CK1δ have been linked to cancer progression, while SNPs in CEP and OCA2 genes affect gene regulation and protein stability23,24,25,26,27,28. These studies underscore the relevance of molecular docking, MD simulations, and SNP analysis in biomedical research.

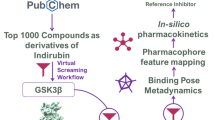

There are several existing drugs known to inhibit GSK-3β, such as lithium citrate, used in bipolar disorder treatment, and tideglusib, for AD. Although GSK-3β inhibitors show promise for therapeutic use, several challenges have been identified in their development. Issues such as poor specificity, off-target effects, and undesirable toxicity profiles have limited their clinical application29,30,31,32. Despite their efficacy, these drugs often have significant side effects and limitations in long-term use, prompting the search for alternatives33,34. Phytochemicals, natural compounds in plants like flavonoids, alkaloids, and terpenoids, have emerged as promising alternatives due to their lower toxicity, antioxidant properties, multi-targeted action, and ease of integration into the diet. These advantages make phytochemicals a safer and potentially more effective option for therapeutic intervention in cancer and other conditions involving GSK-3β dysregulation35. The current study seeks to explore the potential of phytochemicals as inhibitors of GSK-3β, a key regulator in various pathological processes, including cancer. Through computational approaches such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, we aim to identify phytochemicals that exhibit strong binding affinities to GSK-3β and could serve as safer, more effective therapeutic alternatives to existing inhibitors. The integration of network pharmacology, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and principal component analysis (PCA) provides a comprehensive and multi-dimensional approach that enhances the precision, reliability, and depth of drug discovery, offering a more robust and validated understanding of compound-target interactions. By doing so, the limitations of current GSK-3β inhibitors, such as side effects and low selectivity, could be overcome and provide a foundation for future experimental validation and therapeutic development. Compared to the previous studies, this approach integrates a uniquely curated phytochemical library, robust dual platform docking, and extensive 200 ns MD simulations, providing detailed insights into compound stability and interaction dynamics.

Materials and methods

Ligand selection

Phytochemicals with anti-cancer, anti-tumor, and anti-Alzheimer properties have been retrieved in the field of ligand prediction. A thorough examination of pertinent literature was undertaken to extract information regarding medicinal plants or their constituent phytochemicals that demonstrate characteristics suggestive of anti-cancer or cancer preventive or anti-carcinogenic activity. The botanical names of these plants were used as search terms in Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases (https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/). The acquired results were subsequently examined to identify potential phytochemicals with the mentioned characteristics. For the positive control, tideglusib (PubChem CID 1313622) has been selected.

Protein selection and active site prediction

The structure of GSK-3β in complex with a natural inhibitor [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]triazine (6H0U) was selected from RSCB PDB (https://www.rcsb.org) with a resolution of 2.30 Å for the docking process to know more about the active side of that protein36. Missing loops or residues were modeled. Polar hydrogens were added, and protonation states were assigned for pH 7.4 using the GROMACS pdb2gmx tool. All crystallographic water molecules were removed. Protonation states were assigned at pH 7.4 using GROMACS default parameters. Gasteiger charges were applied to ligands, and missing atoms or residues were modeled using the pdbfixer tool. The active region on the surface of the protein that performs the protein function is known as a protein-ligand binding site. To avoid blind docking, the specific amino acid residue of protein-ligand interaction was predicted using CASTP v3.0 (http://sts.bioe.uic.edu/castp/calculation.html). The CASTp server was used with a default probe radius of 1.4 Å, which simulates the size of a water molecule and is commonly used for surface and pocket analysis37.

ADMET profiling

For ADME profiling, the SwissADME server (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php) was employed. To perform the ADME analysis, the canonical SMILES strings of the ligands were required. These SMILES strings were used as input to the pkCSM server (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm) for toxicity profiling. All canonical SMILES were stored in a text document and subsequently uploaded to the pkCSM server. The resulting data were downloaded in CSV format and sorted based on the following criteria (Table 1).

Molecular docking of phytochemical

The compounds that have successfully undergone ADMET profiling were chosen for molecular docking with the selected protein. The ligands have been analyzed in mgltool 1.5.7 (https://ccsb.scripps.edu/mgltools/). The target protein was transformed into pdbqt format, and a grid box was established based on its active site. Hydrogen atoms were positioned on the polar regions, and Kollman charges were incorporated during protein preparation. Afterward, the docking results were evaluated for binding affinity, and all the resulting docked conformations were saved in a pdbqt file. The docking results were expressed as a negative score in units of kcal/mol, with a lower score indicating a higher binding affinity.

The result was visualized using the Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer 2021 and PyMol. The output files, output.pdbqt, and macromolecule, were opened concurrently in the PyMol software. During the docking process, a total of 9 distinct conformations were generated. However, for analysis, only the conformations with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0 were taken into consideration. The docking affinity was compared with the positive control and natural ligand of the erk protein, and the top result was selected for the simulation process. The ligand and protein formed a protein-ligand docking complex, which was saved in the pdb format for subsequent analysis and generation of binding site figures. All docking studies were targeted toward the ATP-binding site of GSK-3β based on the co-crystallized ligand in PDB ID: 6H0U. Although allosteric inhibition is a promising avenue, this study did not identify or explore alternative binding pockets. To validate the docking protocol, the co-crystallized ligand from PDB ID: 6H0U was redocked, and the RMSD between the experimental and docked pose was found to be within 2.0 Å, supporting docking reliability.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

The simulation used the CHARMM36m force field, and the system was solvated using the TIP3P water model. Na+ and Cl- ions were added to neutralize the system and reach a 0.15 M salt concentration. Temperature was maintained at 300 K using the V-rescale thermostat and pressure at 1 atm using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat. The system underwent energy minimization followed by 100 ps NVT and 100 ps NPT equilibration before the 200 ns production run. The 200 ns duration was chosen as it typically captures essential conformational rearrangements and has been widely used to assess inhibitor stability in similar protein-ligand systems38. The CHARMM36m force field was used for the protein throughout all simulations to ensure consistency, while ligand topologies were generated using the General Amber Force Field (GAFF) via ACPYPE. This combination was validated for compatibility through literature benchmarks and energy minimization convergence. Each complex underwent a 200 ns MD production run, allowing sufficient time to evaluate ligand stability and dynamic behavior within the active site. The 200 ns trajectory was based on a single simulation run per complex. While trends are consistent with the literature, future studies should include multiple replicates to ensure statistical confidence. Structural stability was further analyzed using RMSD, radius of gyration (Rg), RMSF, and hydrogen bond analysis, ensuring that the observed conformational changes accurately reflect biological conditions. These carefully chosen simulation parameters reinforce the credibility of our findings and provide insights into the stability of phytochemicals as potential GSK-3β inhibitors.

The analysis of the MD simulation data comprised the calculation of several parameters, namely the root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration (Rg), and solvent accessible surface area (SASA)39. The duration of 200 ns for the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was chosen based on its ability to provide sufficient time for the protein-ligand complex to achieve conformational stability and explore its binding interactions. This timescale is commonly used in computational studies for validating the stability of small-molecule inhibitors in protein-ligand complexes, as it typically captures critical events such as backbone relaxation, interaction stabilization, and fluctuations in active site residues. The ggplot2 package (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/) was used in RStudio to create visualizations for each analysis. Additionally, principal component analysis (PCA) and the covariance matrix of protein were analyzed for further validation of the result. Simulation results were visualized and analyzed with the grace tool in the Linux operating system. The graph was displayed in.png format in the result section.

Metabolic pathway analysis

Metabolic pathway analysis was performed by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes KEGG (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html). The KEGG pathway is a collection of manually drawn pathway maps representing our knowledge of the molecular interaction, reaction, and relation networks for metabolism, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, cellular processes, organismal systems, human diseases, and drug development40.

Results

Prediction of active sites for GSK-3β

The identification of active sites on the GSK-3β protein was conducted using CASTP v3.0, a computational tool for locating and measuring pockets and voids on protein surfaces (http://sts.bioe.uic.edu/castp/calculation.html). The CASTp v3.0 analysis identified a total of 15 pockets on the surface of GSK-3β. The largest pocket, with a surface area of 1739.261 Ų and a volume of 1456.678 ų, was selected as the most suitable binding site for docking studies. This pocket was chosen due to its well-defined shape, accessibility, and potential to accommodate the ligand effectively. While the other pockets identified by CASTp were smaller and not as easily accessible, this largest pocket was determined to be the most promising for ligand binding and subsequent docking analysis. In addition to surface area and volume, the chosen pocket also showed optimal depth and accessible mouth area suitable for ligand accommodation, based on CASTp scoring. Although conservation scores were not explicitly analyzed, the pocket aligns with known ATP-binding motifs. These active sites are critical regions on the protein where ligands, such as the selected phytochemicals, can bind. The residues identified as active sites were verified (Fig. 1 and Table S1). These residues play a crucial role in the binding process, where the phytochemicals interact with the GSK-3β protein, potentially inhibiting its activity.

The hydrophobicity distribution and active sites of GSK-3β. The protein surface is colored according to hydrophobicity values, with the scale ranging from -3.00 (blue, indicating high hydrophilicity) to 3.00 (brown, indicating high hydrophobicity). The active site of the protein is circled and magnified to show detailed features. The inset provides a closer view of the active site, highlighting regions with varied hydrophobic properties.

Ligand extraction

Phytochemicals were chosen as primary ligands for the inhibition of the GSK3β protein due to their potential anti-cancer properties. Dr. Duke’s database was utilized to extract ligands based on their anti-cancer, anti-tumor, and anti-Alzheimer activities. Initially, 918 phytochemicals were identified. After removing duplications, a total of 761 unique compounds remained for further analysis.

ADMET profiling of sorting phytochemicals

ADMET profiling was performed for the 761 phytochemicals sorted. The compounds were analyzed further for some threshold points such as poor absorption or permeation is expected to occur more frequently in the discovery setting when the number of H-bond donors exceeds 5, the number of H-bond acceptors reaches 10, the molecular weight (MWT) exceeds 500, and AMES toxicity and hepatotoxicity should be negative41. Most of the phytochemicals did not satisfy the threshold point that was sought for further analysis. Among the total of 761 compounds, only 49 phytochemicals and 1 positive control were filtered according to the threshold point (Table 2). To ensure the clinical relevance of the shortlisted compounds, a rigorous ADMET screening approach was implemented. The 49 selected phytochemicals underwent stringent filtering based on Lipinski’s Rule of Five, which included molecular weight (≤500 Da), hydrogen bond donors (≤5), hydrogen bond acceptors (≤10), and XLOGP3 (≤5) to ensure drug-like properties. Additional toxicity screening criteria were applied, including hepatotoxicity, AMES toxicity, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, eliminating compounds with unfavorable toxicity risks. This approach ensured that only compounds with favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles were shortlisted. Furthermore, the selected compounds were benchmarked against the positive control (tideglusib) for comparative pharmacokinetic assessment. While computational ADMET profiling provides strong preliminary insights, future experimental validation will be necessary to confirm their clinical translatability.

The GSK-3β inhibitor (positive control) exhibits hepatotoxicity, whereas the remaining compounds that satisfy all the associated criteria have been selected for subsequent processing (Table 2). The other parameters of ADMET profiling results, such as molecular weight, heavy atoms, rotatable bonds, h-bond acceptors, H-bond donors, max. tolerated dose (human), skin sensitization, and minnow toxicity were also analyzed and summarized (Table S2). All these findings suggest that these compounds are suitable for further examination through docking and stability testing. However, it is important to note that computational ADMET profiling provides preliminary insights, and while these compounds showed promising drug-like properties, the possibility of off-target effects remains a potential concern.

Molecular interaction at the active site

The ADMET filtered 49 phytochemicals, and positive control was further analyzed through docking in triplicates using two platforms, AutoDock Vina-1.5.7 and PyRx (Table S3). Phytochemicals with a higher binding affinity than the positive control (-8.56±0.05) were considered potential inhibitors, and their interacting residues were analyzed further (Table 3). The binding affinities and stability of uzarigenin and podolide were compared to Tideglusib, which served as the positive control. However, other established GSK-3β inhibitors, such as lithium chloride, CHIR99021, and SB216763, were not included in this analysis as the primary focus of the study was on phytochemicals42. Including these compounds would require a broader scope encompassing both natural and synthetic inhibitors.

The interaction of the complexes provides a detailed analysis of the binding interactions between the enzyme’s active site and various ligands, including a control compound and four complexes (Table 3). In this study, we have identified key residues involved in the binding interactions with GSK-3β. These residues play critical roles in the enzyme’s active site and contribute significantly to its catalytic function. Previous studies have highlighted similar binding motifs, emphasizing their relevance in GSK-3β's regulation of cellular processes, including glycogen synthesis and apoptosis43. This indicates that the specific interactions between these residues and inhibitors may offer insights into the design of more targeted therapeutic agents for diseases related to GSK-3β dysregulation The control, tideglusib, forms hydrophobic interactions with residues such as Cys199, Val70, Lys85, and Ala83, with bond distances from 3.59179 Å to 5.09786 Å, and a hydrogen bond with Cys199 at 4.13342 Å. Complex 1 (Uzarigenin) shows a binding affinity with an Autodock Vina score of -8.63±0.04 Kcal/mol and a PyRx score of -8.5 Kcal/mol, interacting hydrophobically with several residues and forming strong hydrogen bonds, with distances as short as 2.35384 Å. Complex 2 (Podolide) exhibits robust binding with scores of -8.6 Kcal/mol (Autodock Vina) and -8.67±0.05 Kcal/mol (PyRx), interacting hydrophobically with residues and forming hydrogen bonds with distances of 2.49443 Å and 2.59469 Å. Complex 3 (Jatrophone) has the highest binding affinity, with an Autodock Vina score of -9±0 Kcal/mol and a PyRx score of -8.5 Kcal/mol, showing hydrophobic interactions and a notable hydrogen bond with Cys199 at 3.31299 Å. Complex 4 (Chrysin) shows binding scores of -8.5 Kcal/mol for both Autodock Vina and PyRx, with hydrophobic interactions and a significant hydrogen bond with Asp133 at 2.02206 Å, indicating strong electrostatic stabilization (Table 3). Various molecular interactions have been observed between the target protein and the four different ligands, showcasing a diverse range of binding mechanisms. The molecular docking configurations correspond to the complexes, demonstrating the interactions between a control compound, Tideglusib, and four phytochemicals with specific amino acid residues of a protein. The control shows interactions with residues such as Cys199 and Ala83. Complexes 1 to 4- uzarigenin, podolide, jatrophone, and chrysin, respectively, highlight various binding interactions and affinities. The Common residues are Val70, Ala83, Cys199, Leu188, and Tyr 140 (Fig. 2). Notable residues include Cys199, Val70, and Ala83, which were found to form significant hydrophobic and hydrogen bond interactions with the ligand. Additionally, Lys85 and Leu188 also play critical roles in stabilizing the binding complex. These residues, which are part of the active site, contribute to the functional importance of GSK-3β in cellular regulation and suggest potential targets for therapeutic development in diseases related to GSK-3β dysregulation (Table S1).

3D interaction diagrams of ligands with the active site of GSK-3β. Each subfigure represents a different ligand: (A) Tideglusib, (B) Uzarigenin, (C) Podolide, (D) Jatrophone, and (E) Chrysin. The interactions are categorized as follows: green dash lines- Conventional Hydrogen Bond, Light Green dash lines- Pi-Donor Hydrogen Bond, Purple dash lines-Pi-Sigma, Yellow Dash lines -Pi-Sulfur, Pink Dash lines- Pi-Alkyl. Ligands are shown in the middle with red color, and the Residues are shown with the color of blue. Surrounding residues involved in interactions are labeled with their amino acid name and residue number.

Molecular dynamics simulation analysis

A simulation lasting 200 nanoseconds was conducted to assess the stability of the binding. The simulation results were evaluated using RMSD, RMSF, SASA, and radius of gyration analysis. The binding grooves of the compounds under investigation were compared and found to have a significant level of similarity in their spatial layouts. Only the complexes exhibiting better RMSD, RMSF, SASA, and gyration metrics during MD simulation were shown in the binding grooves. These stable complexes demonstrated deep binding grooves with shared common residues for interaction (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the residues that were involved in interactions showed remarkable similarity across all the compounds. The presence of congruency in the binding grooves and interacting residues indicates a consistent way of binding, which strengthens the probability of a common molecular process or target interaction. The pocket region of the complex (Fig. 3) depicts all the ligands that were bound in the same pocket and the residues that mimicked each other.

A hydrophobic surface map of a protein with different ligands highlighting its binding interactions. (A) Shows the overall protein structure with hydrophobic (brown) and hydrophilic (blue) regions, focusing on a key binding site. (B) Control (Tideglusib CID-11313622) displays this site in its unbound state, emphasizing the hydrophobic characteristics. (C) Complex 1 (Uzarigenin CID-92760) and (D) complex 2 (Podolide CID-99535). Zoom into the same binding site, illustrating how different ligands interact with the protein. These panels reveal changes in the binding pocket’s surface properties upon ligand binding, providing insights into the molecular interactions and potential binding affinities of the complexes.

The RMSD of Protein-ligand complexes over a 200 ns time scale indicates the stability of the interactions. RMSD, a measure of the deviation of the protein and ligand over time, serves as a good benchmark for stability. Control (Tideglusib) RMSD, protein deviates between approximately 0.2 nm and 0.6 nm, indicating some structural flexibility but overall stability (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the ligand RMSD, shown, ranges from about 0.2 nm to 1.4 nm, demonstrating significant deviations and suggesting a lack of stable contact with the protein. Complex 1 (Uzarigenin) shows notable deviations with protein RMSD ranging from 0.25 nm to 1.25 nm and ligand RMSD from 0.25 nm to 1.25 nm, indicating initial instability but stabilizing around 0.75 nm after 75 ns (Fig. 4B). The initial instability observed in uzarigenin’s RMSD values may be attributed to transient conformational adjustments within the protein-ligand complex as the compound settles into the binding pocket. This behavior suggests that uzarigenin undergoes significant structural reorganization during the early phase of the simulation. However, its eventual stabilization after approximately 75 ns indicates that these adjustments lead to a more energetically favorable binding conformation. The stabilization is further supported by consistent interactions observed in SASA and radius of gyration analyses. While the initial instability may reflect a need for a longer binding equilibration phase compared to other ligands like podolide, the overall stability achieved later in the simulation demonstrates uzarigenin-s strong potential as a GSK-3β inhibitor. Complex 2 (Podolide) exhibits more stable binding with minor fluctuations, maintaining protein RMSD around 0.5 nm and ligand RMSD around 0.5-0.75 nm (Fig. 4C). Further investigations are required to fully understand the binding characteristics and fluctuations in these complexes. The other complexes showed poor stability based on the simulation results (Fig. S1, A and B).

A 200-nanosecond simulation to measure the root mean square deviation (RMSD) And Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF). Graphs represent Control RMSD (A), Complex 1 RMSD (B), Complex 2 RMSD (C), Control RMSF (D), Complex 1 RMSF (E), and Complex 2 RMSF (F) analyses for protein and ligand interactions over 200 ns. The First three plots display two lines: the blue line represents the protein RMSD, and the maroon line represents the ligand RMSD. RMSD values are plotted on the Y-axis in nanometers (nm), and time is plotted on the X-axis. (D-F) Display RMSF of protein over time. The fluctuation primarily arises when the ligand interacts with the protein residues. Control exhibits multiple significant fluctuations. Complex 1 shows moderate fluctuations with better stability. Complex 2 demonstrates minimal fluctuations, indicating the highest stability.

The Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis is a valuable tool for quantifying localized variations along the protein chain, with peaks indicating regions of highest fluctuation during the simulation. Typically, the N- and C-terminal tails exhibit greater fluctuations compared to other protein regions. Secondary structure elements like alpha helices and beta strands exhibit greater rigidity and less fluctuation than unstructured loop regions (Fig. 4, D-F). In the control with tideglusib (Fig. 4D), RMSF values range from approximately 0.1 nm to 0.8 nm, with peaks indicating higher flexibility around residue indices 50, 150, and 200, and a significant peak near 400. For complex 1 with uzarigenin (Fig. 4E), the RMSF values range from about 0.1 nm to 0.9 nm, showing similar peaks at residue indices 50, 150, and 200; and a prominent peak near 375, suggesting regions of increased flexibility. In complex 2 with podolide (Fig. 4F), RMSF values range from approximately 0.1 nm to 1.0 nm, with peaks at similar residue indices, highlighting the regions of the protein with greater flexibility, particularly near residue 375. These observations indicate that while the protein exhibits inherent flexible regions, the binding of uzarigenin and podolide introduces slightly higher flexibility compared to the control. The other complexes exhibit several significant fluctuations based on the simulation RMSF analysis (Fig. S1, C, and D).

The SASA analysis over the 200 ns simulation reveals distinct differences in solvent accessibility between the unbound and ligand-bound states of the protein. The SASA analysis provides insights into the structural stability of the protein-ligand complex by measuring the extent of solvent exposure to the protein surface. In this study, we observed that the unbound control (tideglusib) fluctuated within 210.0-215.0 nm², whereas the bound complexes (uzarigenin and podolide) exhibited SASA values ranging from 205.0 to 217.5 nm² (Fig. 5A). The slightly lower SASA values for uzarigenin indicate that ligand binding promotes protein compactness, stabilizing the structure without excessive expansion or solvent exposure. Meanwhile, podolide demonstrated SASA fluctuations like the control, suggesting a well-fitted ligand without significant disruption to protein conformation. The stability of these complexes is further reinforced by consistent RMSD and Rg values, confirming that both phytochemicals maintain strong interactions with GSK-3β without inducing destabilizing conformational changes. These findings highlight the potential of uzarigenin and podolide as stable inhibitors, warranting further experimental validation. During MD, uzarigenin formed strong hydrogen bonds with Lys183 (2.35 Å) and Gln185 (2.40 Å), and hydrophobic contacts with Val70, Ala83, and Leu188. Podolide displayed hydrogen bonding with Arg220 (2.49 Å) and Tyr221 (2.59 Å), stabilizing through hydrophobic contacts with Tyr140 and Leu188. Jatrophone showed the highest binding affinity and maintained hydrogen bonding with Cys199 (3.31 Å) and strong hydrophobic interactions with Val70 and Leu188 throughout the simulation. These interactions were persistent across the trajectory, contributing to each ligand’s stability. The remaining complexes, which showed poor stability during RMSD analysis, also showed poor stability in the SASA analysis (Fig. S2A).

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) and Radius of Gyration (Rg) over time for various protein-ligand complexes. (A) The figure presents the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations for tideglusib and two complexes: Complex_1-92760 and Complex_2-99535. The Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) over time, with the x-axis representing the simulation time in nanoseconds (ns) and the y-axis indicating the SASA in nanometers squared (nm²). (B) Depicts the radius of gyration over time, with the x-axis representing simulation time in picoseconds (ps) and the y-axis showing the radius of gyration in nanometers (nm). The control group is shown in green, complex 1 (92760) in orange, and complex 2 (99535) in blue.

The radius of gyration (Rg) analysis over the 200 ns simulation provides insight into the compactness and structural stability of the protein in both unbound and ligand-bound states. The radius of Gyration varies between 2.14 nm and 2.24 nm over 200,000 ps, with the control fluctuating around 2.16-2.20 nm, complex 92,760 showing a slightly tighter range (2.15-2.19 nm), and complex 99,535 closely mirroring the control (2.16-2.20 nm) (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that the presence of the complexes does not cause significant deviations in SASA, or gyration radius compared to the control. The gyration information of the remaining complexes, which showed poor stability during RMSD analysis, has also been analyzed and found minor fluctuations over time (Fig. S2B). Proteins with moderate compactness, indicated by their radius of gyration, showed increased gyration values upon ligand binding due to structural disruption. The Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) analysis revealed that moderate gyration and higher molecular surface area provided multiple binding sites, while moderate SASA indicated structural stability. Lowering gyration (Fig. 5B) and SASA (Fig. 5A) is necessary for stronger binding affinity. The remaining complexes, which showed poor stability during RMSD analysis, also showed poor stability in the gyration analysis (Fig. S2B).

PCA analysis

The PCA results of these three complexes have been analyzed (Fig. 6). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was utilized to evaluate the global conformational dynamics of GSK-3β in both ligand-bound and unbound states, providing insights into protein flexibility and stability. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) accounted for most of the variance in motion, highlighting the most dominant structural changes induced by ligand binding.

Principal Component Analysis of Molecular Dynamics Data. This figure presents the PCA results for three different complexes, including control (A), Complex 1 (B), and Complex 2 (C). In each panel, the top row shows scatter plots of the principal components (PCs): PC1 vs. PC2, PC1 vs. PC3, and PC2 vs. PC3. The axes labels indicate the percentage of variance explained by each PC. The bottom row includes scree plots depicting the proportion of variance explained by each eigenvalue rank. The color gradient from blue to red represents the progression of samples over time or another relevant metric.

The PCA results revealed that ligand binding significantly altered the protein’s conformational landscape. The unbound GSK-3β exhibited broader dispersion, indicating higher structural flexibility, whereas the ligand-bound complexes (uzarigenin and podolide) showed a more compact clustering pattern, suggesting a restriction of large-scale domain movements. This stabilization effect was particularly evident in the eigenvalue distributions, where both uzarigenin and podolide reduced large-scale protein fluctuations compared to the unbound control.

These findings support the therapeutic potential of uzarigenin and podolide as GSK-3β inhibitors by demonstrating their ability to restrict excessive protein motion and stabilize the active-site conformation. The reduction in large amplitude fluctuations suggest enhanced ligand retention within the binding pocket, which is critical for sustained inhibition and drug efficacy. Additionally, the clustering pattern of tideglusib (control) was comparable to that of the strong-binding phytochemicals, reinforcing the hypothesis that these compounds may exhibit similar stabilizing effects on GSK-3β.

By limiting conformational fluctuations, uzarigenin and podolide enhance the structural integrity of GSK-3β, which may contribute to greater binding affinity and prolonged inhibitory activity. These insights highlight the significance of PCA in understanding ligand-induced stability, further supporting the potential therapeutic relevance of the identified phytochemicals.

PCA analysis of each component percentage indicates different aspects of the protein-ligand interaction: PC1 might indicate how strongly the ligand binds to the protein, PC2 could represent the flexibility of the protein-ligand complex, and PC3 might capture variations in the shape complementarity between the protein and ligand44. The control (Fig. 6A), PC1 vs. PC2, shows the data distribution with PC1 explaining 27.83% and PC2 explaining 12.17% of the variance, indicating distinct conformational states. PC2 vs. PC3 displays the distribution along PC2 (12.17%) and PC3 (6.17%), providing a 3D view. PC1 vs. PC3 illustrates the distribution along PC1 and PC3, while eigenvalue rank plot shows PC1, PC2, and PC3 explaining 27.83%, 12.17%, and 6.17% of the variance, respectively. For Complex 1 (Fig. 6B), the PC1 vs. PC2 shows PC1 explaining 11.45% and PC2 explaining 10.75%, indicating different conformational states. The PC2 vs. PC3 shows the distribution between PC2 and PC3, with PC3 explaining 5.3%. The PC1 vs. PC3 shows the variance between PC1 and PC3, and the eigenvalue rank plot indicates PC1, PC2, and PC3 explaining 11.45%, 10.75%, and 5.3%, respectively. For complex 2 (Fig. 6C), the PC1 vs. PC2 shows PC1 explaining 28.71% and PC2 explaining 13.33%, indicating distinct conformational clusters. The PC2 vs. PC3 shows the variance between PC2 and PC3, with PC3 explaining 6.06%. The PC1 vs. PC3 shows the distribution between PC1 and PC3, and the eigenvalue rank plot shows PC1, PC2, and PC3 explaining 28.71%, 13.33%, and 6.06%, respectively.

The highest percentage of variance explained is indicated by the single component with the highest variance (PC1). Complex 1 yields the most favorable outcomes, followed by Complex 2 and Control. By considering the components that capture substantial variation, Complex 1 exhibits a sum of 46.17% and 53% in the first two components, indicating improved variances. Complex 1 exhibits superior performance in both analyses, whether considering a singular component with the highest variance or a collection of components that account for a substantial proportion of the data’s variance (Table 4).

Covariance analysis

The covariance analysis for the four protein-ligand complexes provides insights into the correlated motions between residues during the simulation. Each panel (Fig. 7; A, B, and C) represents the covariance matrix of residue fluctuations for a different complex, where the color intensity indicates the degree of correlation (blue for negative, red for positive).

The covariance analysis of the protein-ligand complexes reveals distinct patterns of residue interactions. (A) Control shows a range of covariance values from -0.135 nm² to 0.762 nm², exhibiting both positive and negative correlations with several distinct clusters of coordinated motions, particularly around residues 75-150 and 225-300. (B) Complex 1, with a covariance range from -0.119 nm² to 0.538 nm², has fewer and less intense correlations, indicating fewer coordinated residue movements. (C) Complex 2 shows a similar pattern to Complex 2, with covariance values ranging from -0.119 nm² to 0.567 nm², featuring scattered clusters of moderate correlations.

Control shows the highest intensity and clustering of correlated motions, indicating a more coordinated movement of residues (Fig. 7A). Complexes 1 (Fig. 7B) and 2 (Fig. 7C) display fewer and less intense correlations, suggesting more independent movements. The range of covariance values is the highest in control. Complexes 1 and 2 have narrower ranges, indicating less variation in residue movements. The positively correlated motions are more prominent in Control, suggesting stronger interactions and coordination among residues. Complexes 1 and 2 show fewer positively correlated regions, indicating more isolated residue movements. Complexes 1 and 2 show less intense and fewer correlated motions, indicating more independent residue movements45. These results suggest that control has the most dynamic and interconnected residue interactions, while complexes 1 and 2 are more stable with isolated residue interactions.

Metabolic pathway analysis

The KEGG pathway analysis gives insightful data about how the proteins are regulated and act as coactivators for other signaling pathways. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed for GSK-3β, and the results highlight nine key pathways46. The KEGG pathway analysis parameters were chosen based on gene count threshold, false discovery rate (FDR), and protein overlap across pathways to ensure biologically relevant findings. Pathways with at least 7 gene associations were considered, with the AD pathway showing the highest observed gene count (9). A stringent FDR cutoff (<1.0E-08) was applied to minimize false-positive results, and the strongest pathway (AD) had an FDR of 7.91E-13, reinforcing its significance. Additionally, core regulatory proteins such as GSK3β, APC, AXIN1, DVL1, AKT1, and CTNNB1 were consistently enriched across multiple pathways, further validating their relevance in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic diseases. These criteria ensured that only highly significant pathways were considered, supporting the therapeutic implications of GSK-3β inhibition. Future research may involve experimental validation of these enriched pathways to further confirm their role in disease modulation. Wnt signaling, breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and gastric cancer pathways each have 8 genes and an FDR of 6.28E-13, sharing key proteins such as APC, AXIN1, AXIN2, GSK3B, FRAT1, DVL1, and CTNNB1. The pathway in cancer is notable with an FDR of 1.10E-09. Pathways regulating the pluripotency of stem cells and the Hippo signaling pathway each involve 7 genes with FDRs of 2.10E-11 and 2.82E-11, respectively, and include proteins like AKT1 and DVL149,50,51. Lastly, the human papillomavirus infection pathway has an FDR of 3.08E-09, highlighting the involvement of similar proteins across these significant pathways50. Based on the pathway analysis, the most significant pathway for GSK-3β inhibition is the AD pathway, with an observed gene count of 9 and the lowest false discovery rate (FDR) of 7.91E-1353. This suggests that GSK3β plays a critical role in the AD pathway, making it the most significant pathway in this context52,53 (Table 5).

Discussion

GSK-3β is implicated in the pathogenesis of various diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, diabetes, and inflammation. In AD, GSK-3β activation increases amyloid-beta (Aβ) and the development of neurofibrillary tangles, disrupting material transport between axons and dendrites. The inhibition of GSK-3β has been shown to reduce tau phosphorylation and tau toxicity, offering potential therapeutic benefits54,55. The study identified several potent phytochemicals as potential GSK-3β inhibitors through ADMET profiling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations. The ADMET analysis filtered 49 phytochemicals with optimal pharmacokinetic properties for further docking studies. Uzarigenin (CID 92760) and podolide (CID 99535) have shown better binding stability during simulation over time, which could suggest the potential phytochemicals for GSK-3β. The effective inhibition of GSK-3β could lead to advancements in the treatment of multiple diseases like cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and metabolic disorders.

GSK-3β inhibition has been widely explored using synthetic inhibitors such as lithium chloride, CHIR99021, and tideglusib, which have demonstrated therapeutic potential in treating neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and metabolic disorders. However, these inhibitors often suffer from poor selectivity, toxicity concerns, and off-target effects, limiting their clinical utility. In contrast, this study advances current knowledge by identifying phytochemicals as promising natural alternatives with potentially higher specificity and lower toxicity. The molecular docking results revealed that uzarigenin (-8.63 kcal/mol) and podolide (-8.6 kcal/mol) exhibited stronger or comparable binding affinity to the standard inhibitor tideglusib (-8.56 kcal/mol), suggesting their potential as effective GSK-3β inhibitors. However, the differences in binding affinities among uzarigenin, podolide, and Tideglusib are marginal, raising the need for statistical validation. Without standard deviations or statistical tests, it is difficult to determine whether these differences are statistically significant or within the variability range of docking calculations. Given the small differences in docking scores, which typically fall within a ±0.5 kcal/mol margin of computational variability, future studies should include multiple replicates and statistical error analysis to validate binding trends more robustly, whether these binding affinities represent a significant improvement over Tideglusib or are merely within expected computational fluctuations. Unlike previous studies that focused primarily on docking analyses, this study employed molecular dynamics simulations, confirming that uzarigenin and podolide maintain stable interactions with GSK-3β over 200 ns, with consistent RMSD, SASA, and PCA clustering results. Additionally, KEGG pathway analysis demonstrated that these phytochemicals modulate critical pathways involved in AD, Wnt signaling, and cancer-related mechanisms, indicating a broad-spectrum therapeutic impact. By integrating docking, molecular dynamics, and pathway analysis, this study expands the scope of GSK-3β inhibitor research and highlights phytochemicals as potential lead compounds for safer and more selective drug development. Phytochemicals offer a promising alternative to synthetic GSK-3β inhibitors, which often suffer from poor selectivity, toxicity, and off-target effects. Unlike traditional ATP-competitive inhibitors, phytochemicals may act through allosteric modulation, reducing the risk of cross-inhibition with other kinases. Phytochemicals offer a promising alternative to synthetic GSK-3β inhibitors, which often suffer from poor selectivity, toxicity, and off-target effects. Unlike traditional ATP-competitive inhibitors, phytochemicals may act through allosteric modulation, reducing the risk of cross-inhibition with other kinases56.

GSK-3β is implicated in the pathogenesis of various diseases like AD, cancer, diabetes, inflammation, etc57. In inflammation, the roles of NEMO, TLR/TNFR, IKK, and NFKB in inflammatory signaling are depicted, underlining the broad impact of GSK-3β (Fig. 8) on various cellular functions and disease mechanisms58,59,60. While this study primarily focuses on the interactions of the identified phytochemicals with GSK-3β, it is important to note that these compounds may also exhibit multi-target potential. Previous research suggests that similar phytochemicals can interact with other key molecular targets involved in various diseases, including neurodegenerative conditions and metabolic disorders, further enhancing their therapeutic potential. PCA results reveal significant insights into the conformational dynamics of the protein-ligand complexes. Complexes 1_uzarigenin and Complex 2_podolide exhibited the highest proportion of variance explained by the first principal component (27.83% and 28.71%, respectively), indicating substantial conformational variations. These complexes also displayed distinct clustering patterns in the scatter plots, suggesting dynamic and stable interactions. Conversely, the control showed overlapping clusters, indicating moderate conformational variations and less coordinated interactions. These findings align with the molecular dynamics simulations, where complexes 1 and 2 demonstrated greater stability61,62,63. The covariance analysis showed distinct patterns of residue interactions, highlighting the coordinated movements in the complexes, which are critical for understanding the stability and efficacy of the inhibitors64. The metabolic pathway analysis using KEGG pathway enrichment provided valuable insights into the regulatory mechanisms involving GSK-3β. The analysis highlighted key pathways, such as AD, Wnt signaling, and various cancer-related pathways, emphasizing the broad impact of GSK-3β inhibition65. These pathways involve critical proteins like APC, AXIN1, AXIN2, GSK3B, MAPT, FRAT1, DVL1, AKT1, and CTNNB1, which play pivotal roles in disease progression and cellular functions (Fig. 8)66.

An illustration of the signaling pathways involved in the regulation of gene expression. The diagram illustrates the interconnected pathways of EGFR, PI3K, PDK1, AKT, and PTEN, highlighting their roles in the regulation of GSK3 and its downstream effects on TSC1, TSC2, RHEB, and mTORC1. The WNT signaling pathway influences B-Catenin activity, which in turn impacts the same downstream pathways. Additionally, the diagram shows the role of NEMO, TLR/TNFR, IKK, and NFKB in inflammatory signaling.

A recent study has identified cefixime and ceftriaxone as potential GSK3β inhibitors through molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and in vitro screening. The study highlights the potential of these compounds in modulating GSK-3β activity67. Another Study screened natural compounds to identify novel GSK-3 inhibitors, employing comprehensive in silico and biochemical approaches. Molecular docking and pharmacokinetics analysis identified Psoralidin and Rosmarinic acid as potential GSK-3 inhibitors, with Psoralidin serving as a better inhibitor for GSK-3β and Rosmarinic acid for GSK-3β68. Another study conducted a computational screening of a library of anti-cancer compounds to identify potential GSK3β inhibitors. The screening process involved docking-based virtual screening, physicochemical and ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulations, leading to the identification of BMS-754,807 and GSK429286A as having high binding affinities to GSK-3β69.

The overall significance of our study lies in the identification of new potential GSK-3β inhibitors from phytochemicals, which can be further explored for their multi-use potential in treating diseases associated with both GSK-3β and other signaling proteins70. However, this study is limited by the absence of experimental validation. To validate computational results, researchers often perform both in vitro (outside a living organism) and in vivo (within a living organism) experiments, comparing the outcomes to assess the model’s accuracy and predictive power. To verify the computational findings, an in vitro kinase inhibition assay using purified GSK3β protein could be performed to assess the binding affinity and inhibitory activity of the selected phytochemicals. Furthermore, cell line-based/model organisms could be employed to examine their effects on GSK3β-mediated signaling pathways in relevant disease models. These experimental approaches will provide essential validation for the computational predictions and strengthen the translational potential of our findings. Phytochemicals that demonstrated the highest binding affinity, strong interaction with key GSK3β active site residues, and favorable ADMET properties will be prioritized for experimental validation. All these aspects are crucial for real-world applications as they determine the compound’ s therapeutic potential, safety, and efficacy. Computational analysis is helping to shortlist potential compounds and reduce the wet lab workload. Special attention will be given to compounds predicted to cross the blood-brain barrier for neurological disorders and those with suitable pharmacokinetic properties for systemic diseases such as diabetes. Prioritizing these aspects will help identify the most promising candidates for further preclinical development. To address discrepancies between computational predictions and experimental results, the molecular docking and dynamics simulation protocols need to be refined by incorporating experimentally validated datasets to enhance prediction accuracy. Additionally, machine learning-based predictive models will be explored to improve the reliability of binding affinity and activity predictions. If inconsistencies arise, a structure-activity relationship analysis could be conducted to identify modifications that could improve phytochemical efficacy.

While synthetic inhibitors like CHIR99021 or SB216763 were not included in our docking comparison, future studies incorporating these could provide a more holistic benchmark of phytochemical efficacy. Future work should include these assays to confirm the computational predictions and further assess the therapeutic potential of the designed compounds. This could streamline drug development processes and enhance therapeutic efficacy across multiple conditions. Taken together, this study successfully identified potent phytochemical inhibitors for GSK-3β using a comprehensive computational approach. Further experimental validation and optimization of these inhibitors could lead to significant advancements in therapeutic strategies targeting GSK-3β.

Conclusion

This study has successfully identified potent inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3β) using a comprehensive in silico approach, with uzarigenin and podolide emerging as top candidates. The results suggest promising therapeutic potential for treating diseases such as Alzheimer’s, cancer, and metabolic disorders. Although the current study is computational, future work will involve experimental validation of top candidates through in vitro kinase inhibition assays and cellular models to assess the biological activity and therapeutic potential of uzarigenin, podolide, and other lead phytochemicals. Further optimization of these phytochemicals could improve their pharmacological properties, leading to the development of novel drug candidates. Additionally, long-term studies should explore the broader implications of GSK-3β inhibition across other disease pathways and evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of these compounds. Ultimately, this research could contribute to the creation of multifunctional therapeutics targeting GSK-3β for a wide range of chronic and complex diseases.

Data availability

All data supporting the described findings of the study can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon request.

Abbreviations

- GSK-3β:

-

Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Beta

- ADMET:

-

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity

- RMSD:

-

Root mean square deviation

- RMSF:

-

Root mean square fluctuation

- SASA:

-

Solvent accessible surface area

- Rg:

-

Radius of gyration

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- MD:

-

Molecular dynamics

- Wnt:

-

Wingless/integrated

- CTNNB1:

-

Catenin beta-1

- APC:

-

Adenomatous polyposis coli

- AXIN1/AXIN2:

-

Axis inhibitor 1/2

- MAPT:

-

Microtubule-associated protein tau

- FRAT1:

-

Frequently rearranged in advanced t-cell lymphomas 1

- DVL1:

-

Disheveled segment polarity protein 1

- AKT1:

-

AKT serine/threonine kinase 1

References

Ali, A., Hoeflich, K. P. & Woodgett, J. R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3: properties, functions, and regulation. Chem. Rev. 101, 2527-2540 (2001).

Doble, B. W. & Woodgett, J. R. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1175-1186 (2003).

Jope, R. S. & Johnson, G. V. The glamour and gloom of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 95-102 (2004).

Eldar-Finkelman, H. Glycogen synthase kinase 3: an emerging therapeutic target. Trends Mol. Med. 8, 126-132 (2002).

Sahin, I. et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta inhibitors as novel cancer treatments and modulators of antitumor immune responses. Cancer Biol. Ther. 20, 1047-1056 (2019).

Arciniegas Ruiz, S. M. & Eldar-Finkelman, H. Glycogen synthase Kinase-3 inhibitors: preclinical and clinical focus on CNS-A decade onward. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 14, 792364 (2021).

Yuskaitis, C. J. et al. Lithium ameliorates altered glycogen synthase kinase-3 and behavior in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Biochem. Pharmacol. 79, 632-646 (2010).

McCubrey, J. A. et al. GSK-3 as potential target for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Oncotarget 5, 2881-2911 (2014).

Beurel, E., Grieco, S. F. & Jope, R. S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 0, 114-131 (2015).

Sayas, C. L. & Ávila, J. GSK-3 and tau: A key duet in alzheimer’s disease. Cells 10, 721 (2021).

Domoto, T., Uehara, M., Bolidong, D. & Minamoto, T. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β in cancer biology and treatment. Cells 9, 1388 (2020).

Henriksen, E. J. & Teachey, M. K. Acute in vitro Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 potentiates insulin signaling in type I skeletal muscle of Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Metabolism 56, 931-938 (2007).

Jope, R. S. & Roh, M. S. Glycogen synthase Kinase-3 (GSK3) in psychiatric diseases and therapeutic interventions. Curr. Drug Targets. 7, 1421-1434 (2006).

Duda, P. et al. Targeting GSK3 and associated signaling pathways involved in cancer. Cells 9, 1110 (2020).

Yang, L., Li, A., Lei, Q. & Zhang, Y. Tumor-intrinsic signaling pathways: key roles in the regulation of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. J. Hematol. Oncol. 12, 125 (2019).

Summers, S. A. et al. The role of glycogen synthase kinase 3β in Insulin-stimulated glucose Metabolism *. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 17934-17940 (1999).

Hartigan, J. A., Xiong, W. C. & Johnson, G. V. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β is tyrosine phosphorylated by PYK2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284, 485-489 (2001).

Grimes, C. & Jope, R. CREB DNA binding activity is inhibited by glycogen synthase kinase-3β and facilitated by lithium. J. Neurochem. 78, 1219-1232 (2001).

Shin, S., Wolgamott, L., Yu, Y., Blenis, J. & Yoon, S. O. Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β promotes p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K) activity and cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 108, E1204-E1213 (2011).

Sayas, C. L., Ariaens, A., Ponsioen, B. & Moolenaar, W. H. GSK-3 is activated by the tyrosine kinase Pyk2 during LPA1-mediated neurite Retraction. Mol. Biol. Cell. 17, 1834-1844 (2006).

Bhardwaj, V. K. & Purohit, R. A comparative study on inclusion complex formation between Formononetin and β-cyclodextrin derivatives through multiscale classical and umbrella sampling simulations. Carbohydr. Polym. 310, 120729 (2023).

Bhardwaj, V., Singh, R., Singh, P., Purohit, R. & Kumar, S. Elimination of bitter-off taste of stevioside through structure modification and computational interventions. J. Theor. Biol. 486, 110094 (2020).

Gopalakrishnan, C., Kamaraj, B. & Purohit, R. Mutations in MicroRNA binding sites of CEP genes involved in cancer. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 70, 1933-1942 (2014).

Kalsi, N., Gopalakrishnan, C., Rajendran, V. & Purohit, R. Biophysical aspect of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and role of oncogenic mutants (E542K & E545K). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 34, 2711-2721 (2016).

Kamaraj, B. & Purohit, R. Computational screening of disease-associated mutations in OCA2 gene. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 68, 97-109 (2014).

Kamaraj, B., Rajendran, V., Sethumadhavan, R. & Purohit, R. In-silico screening of cancer associated mutation on PLK1 protein and its structural consequences. J. Mol. Model. 19, 5587-5599 (2013).

Kumar, A., Rajendran, V., Sethumadhavan, R. & Purohit, R. Relationship between a point mutation S97C in CK1δ protein and its affect on ATP-binding affinity. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 32, 394-405 (2014).

Sharma, B., Bhattacherjee, D., Zyryanov, G. V. & Purohit, R. An insight from computational approach to explore novel, high-affinity phosphodiesterase 10A inhibitors for neurological disorders. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 41, 9424-9436 (2023).

Beurel, E., Grieco, S. F. & Jope, R. S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 148, 114-131 (2015).

Cohen, P. & Goedert, M. GSK3 inhibitors: development and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 479-487 (2004).

Maqbool, M. & Hoda, N. GSK3 inhibitors in the therapeutic development of diabetes, cancer and neurodegeneration: past, present and future. Curr. Pharm. Des. 23, 4332-4350 (2017).

Meijer, L. et al. GSK-3-selective inhibitors derived from Tyrian purple indirubins. Chem. Biol. 10, 1255-1266 (2003).

Martínez-González, L. et al. Tideglusib, a Non-ATP competitive inhibitor of GSK-3β as a drug candidate for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8975 (2021).

Snitow, M. E., Bhansali, R. S. & Klein, P. S. Lithium and therapeutic targeting of GSK-3. Cells 10, 255 (2021).

Roy, A. et al. Flavonoids a Bioactive Compound from Medicinal Plants and Its Therapeutic Applications. Biomed Res Int 5445291 (2022). (2022).

Redenti, S. et al. A Triazolotriazine-Based dual GSK-3-/CK-1δ ligand as a potential neuroprotective agent presenting two different mechanisms of enzymatic Inhibition. ChemMedChem 14, 310-314 (2019).

Tian, W., Chen, C., Lei, X., Zhao, J. & Liang, J. CASTp 3.0: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W363-W367 (2018).

Huang, J. et al. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods. 14, 71-73 (2017).

Abraham, M. J. et al. High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1. GROMACS, 19-25 (2015).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672-D677 (2025).

Chandrasekaran, B., Abed, S. N., Al-Attraqchi, O., Kuche, K. & Tekade, R. K. Chapter 21 - Computer-Aided Prediction of Pharmacokinetic (ADMET) Properties. in Dosage Form Design Parameters (ed. Tekade, R. K.) 731-755Academic Press, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814421-3.00021-X

Domínguez, J. M. et al. Evidence for irreversible Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β by Tideglusib. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 893-904 (2012).

Ilouz, R., Kowalsman, N., Eisenstein, M. & Eldar-Finkelman, H. Identification of novel glycogen synthase Kinase-3β substrate-interacting residues suggests a common mechanism for substrate recognition*. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30621-30630 (2006).

David, C. C. & Jacobs, D. J. Principal component analysis: A method for determining the essential dynamics of proteins. In Protein Dynamics: Methods and Protocols (ed. Livesay, D. R.) 193-226 (Humana, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-62703-658-0_11.

Lange, O. F. & Grubmüller, H. Full correlation analysis of conformational protein dynamics. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 70, 1294-1312 (2008).

Du, J. et al. A decision analysis model for KEGG pathway analysis. BMC Bioinform. 17, 407 (2016).

Xu, X., Zhang, M., Xu, F. & Jiang, S. Wnt signaling in breast cancer: biological mechanisms, challenges and opportunities. Mol. Cancer. 19, 165 (2020).

Groenewald, W., Lund, A. H. & Gay, D. M. The role of WNT pathway mutations in cancer development and an overview of therapeutic options. Cells 12, 990 (2023).

Liu, L. J. et al. Aberrant regulation of Wnt signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 22, 7486-7499 (2016).

Graham, S. Human papillomavirus: gene expression, regulation and prospects for novel diagnostic methods and antiviral therapies. Future Microbiol. 5, 1493-1506 (2010).

Hooper, C., Killick, R. & Lovestone, S. The GSK3 hypothesis of alzheimer-s disease. J. Neurochem. 104, 1433 (2008).

Lauretti, E., Dincer, O. & Praticò, D. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 signaling in alzheimer-s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Res. 1867, 118664 (2020).

Llorens-Marítin, M., Jurado, J., Hernández, F. & Ávila, J. GSK-3β, a pivotal kinase in alzheimer disease. Front Mol. Neurosci 7, (2014).

Shri, S. R., Manandhar, S., Nayak, Y. & Pai, K. S. R. Role of GSK-3β inhibitors: new promises and opportunities for alzheimer-s disease. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 13, 688-700 (2023).

Balboni, B., Masi, M., Rocchia, W., Girotto, S. & Cavalli, A. GSK-3β allosteric inhibition: A dead end or a new Pharmacological frontier? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 7541 (2023).

Paul, J. K. et al. Advancing alzheimer’s therapy: computational strategies and treatment innovations. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 18, 270-282 (2025).

Yu, H., Xiong, M. & Zhang, Z. The role of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 16, 1209703 (2023).

Mussbacher, M. et al. Cell Type-Specific roles of NF-κB linking inflammation and thrombosis. Front Immunol 10, (2019).

Guo, Q. et al. NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy: new insights and translational implications. Sig Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 1-37 (2024).

Medunjanin, S. et al. GSK-3β controls NF-kappaB activity via IKK-/NEMO. Sci. Rep. 6, 38553 (2016).

Kitao, A. Principal component analysis and related methods for investigating the dynamics of biological macromolecules. J 5, 298-317 (2022).

Maisuradze, G. G., Liwo, A. & Scheraga, H. A. Principal component analysis for protein folding dynamics. J. Mol. Biol. 385, 312-329 (2009).

David, C. C. & Jacobs, D. J. Principal component analysis: A method for determining the essential dynamics of proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 1084, 193-226 (2014).

Szurmant, H. et al. Co-Evolving motions at Protein---Protein interfaces of Two-Component signaling systems identified by covariance analysis. Biochemistry 47, 7782-7784 (2008).

Cruchaga, C. et al. Proteogenomic analysis of human cerebrospinal fluid identifies neurologically relevant regulation and informs causal proteins for alzheimer’s disease. Res. Sq Rs 3 Rs-2814616. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2814616/v1 (2023).

Li, C., Furth, E. E., Rustgi, A. K. & Klein, P. S. When you come to a fork in the road, take it: Wnt signaling activates multiple pathways through the APC/Axin/GSK-3β complex. Cells 12, 2256 (2023).

Nassar, H., Sippl, W., Dahab, R. A. & Taha, M. Molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations and in vitro screening reveal cefixime and ceftriaxone as GSK-3β covalent inhibitors. RSC Adv. 13, 11278-11290 (2023).

Ahmad, F. et al. Natural compound screening predicts novel GSK-3β isoform-specific inhibitors. Biochimie 225, 68-80 (2024).

Hua, L. et al. Identifying promising GSK-3β inhibitors for cancer management: a computational pipeline combining virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulations. Front Chem 11, (2023).

Jiang, X. Y. et al. Dual GSK-3-/AChE inhibitors as a new strategy for multitargeting Anti-Alzheimer-s disease drug discovery. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 9, 171-176 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the logistic support and laboratory facilities of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mahir Azmal and Jibon Kumar Paul performed experiments, methodology, analyzed data, validation, visualization, wrote the initial draft, and contributed equally. Omar Faruk Talukder and ANM Shah Newaz Been Haque performed the experiments, analyzed the data and citation. Ajit Ghosh conceived and designed the experiments, supervised, and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors read the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azmal, M., Paul, J.K., Talukder, O.F. et al. Computational identification of phytochemicals as glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) inhibitors for therapeutic applications in chronic diseases. Sci Rep 15, 34882 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17343-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17343-0