Abstract

Obesity demonstrates bidirectional associations with anxiety, depression and sleep quality. Although bariatric surgery effectively alleviates obesity-related mental health issues, the mechanisms and temporal dynamics of mental symptom improvements remain unclear. This longitudinal study aims to explore the time points at which mental health and sleep quality change after bariatric surgery in overweight/obese patients, and explore correlation between anxiety, depression and sleep quality. Seventy-eight overweight/obese patients (OW/OB) who underwent Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy at the Bariatric Center of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital were included by cohort. Sixty-five healthy controls (HC) were matched by age and sex. Patients received Chinese versions of the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) completed during monthly follow-up surveys after surgery. Before surgery, the OW/OB group had significantly worse anxiety, depression, and sleep problems than HC (all p < 0.001). After surgery, BAI and PSQI scores decreased significantly at all time points, and BDI scores began to decrease at 1 year postoperatively compared with baseline (all p < 0.05). There was a stable positive correlation between preoperative body mass index, BAI, BDI, and PSQI scores, which broke down in the postoperative period. Bariatric surgery improved anxiety symptoms and sleep quality in overweight or obese patients, while depressive symptoms showed delayed but statistically significant improvements at later follow-up points. Stable associations between anxiety, depression, and sleep quality in overweight or obese patients may require multiple interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity constitutes a major global health challenges associated with both physical and psychological disorders, causing great hardship for patients1,2. Beyond its metabolic consequences, obesity significantly impacts psychosocial functioning through mechanisms involving body image dissatisfaction and social stigmatization3,4,5. Accumulating evidence demonstrates bidirectional relationships between obesity and mental health disorders, with meta-analytic data confirming anxiety and depression have a positive correlation with obesity6,7. Notably, sleep disturbances—particularly insomnia and sleep-related breathing disorders, have been identified contributing to the development and outcome of obesity, anxiety and depression8,9,10.

Bariatric surgery is a safe, effective, and durable weight loss intervention for patients with obesity, particularly those who have not achieved sustained weight loss through conventional interventions. Meta-analytic evidence indicates that approximately 23% of candidates for bariatric surgery had any mood disorders, 19% had clinically significant depressive symptoms, and 12% had anxiety symptoms11. Bariatric surgery not only reduces obesity-related physical comorbidities, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease12but also correlates with improvements in mental disorders13,14,14. Recently meta-analyses has found patients with obesity have lower depressive and anxiety symptom scores after surgery15,16. However, improvements in anxiety and depression are nonlinear and influenced by complex psychosocial mechanisms, emerging evidence suggests temporal heterogeneity in psychological outcomes: anxiety and sleep quality may improve rapidly (within 6–12 months), whereas depressive symptoms exhibit delayed or attenuated responses, potentially requiring longer follow-up periods (> 12 months) to observe significant changes16,17. Individuals who are trying to lose weight often experience improvements in sleep disturbances, depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms18,19,20. Therefore, focusing on the alterations of sleep quality and mental symptoms is crucial to treat obesity. Improvements in anxiety and depressive symptoms after bariatric surgery are complex and do not change linearly21Sleep Disturbances be improved after bariatric surgery. However, previous reports have not specified the time point at which these alterations should be studied.

Clarify the relationship between sleep disturbances and mental disorders remains crucial for understanding their pathophysiology. While previous study has established sleep disturbances as significant contributors to anxiety and depression development in general populations8the stability of these relationships at specific postoperative phases requires empirical verification. Notably, the dynamic correlations between postoperative sleep quality, anxiety, and depression at specific recovery phases have yet to be systematically investigated. Network analysis as innovative methodological framework for deciphering complex correlations between mental disorders22,23. Network analysis multidimensional representation of mental health constructs, where nodes correspond to specific psychological dimensions(e.g. anxiety, depressive, sleep quality), and the edges between different nodes quantitatively map their bidirectional relationships24. Such methods are particularly suited to uncovering phase-specific correlations—for instance, whether sleep quality mediates early anxiety improvements while depression resolves later, whether these relationships achieve equilibrium at specific postoperative timepoints, stabilization patterns could inform optimal intervention timing. Network analysis provide a new view and tools for understanding mental disorders and co-occur25.

To address this knowledge gap, this study employs a dual-cohort design with matched healthy controls to enhance validity. While the clinical group undergoes longitudinal assessments, control participants provide baseline reference data through single-timepoint evaluations, to explore: (1) the specific time points at which alterations in anxiety, depression, and sleep quality occur after surgery, with particular attention to mid- and long-term alterations. (2) to characterize the stability of correlations between these constructs after bariatric surgery.

Consequently, the present study was performed to prospectively monitor patients’ mental health alterations while simultaneously revealing their correlations through network analysis. We hypothesized that (1) anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and sleep quality can be improved after surgery; (2) the improvement effect after surgery is different for anxiety, depression, and sleep quality, with depression having poorer effects but anxiety and sleep quality having better effects; and (3) a stable network is present between anxiety, depression, and sleep quality.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

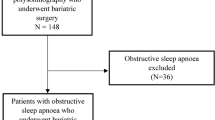

This observational cohort study was performed at Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital from September 2020 to June 2023. We obtained baseline information (age, education years, sex, body mass index, BMI, Beck Depression Inventory II, BDI; Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI) before patients underwent bariatric surgery. The healthy control group (HC) comprised 65 individuals (51 women, 14 men) with healthy BMIs (18.5 kg/m2 < BMI < 24 kg/m2), who were randomly recruited provide baseline reference values without longitudinal follow-up (to prevent practice effects from repeated psychological testing and reduce participant burden). Long-term follow-up surveys were conducted exclusively in the overweight or obesity (OW/OB) group after surgery. Postoperative follow-up examinations were performed at 1-month intervals until 18 months postoperatively and then at 6-month intervals until 24 months postoperatively. Based on the Chinese criteria for overweight and obesity, OW/OB group comprised 78 patients (61 women, 17 men) with overweight or obesity (BMI > 26 kg/m2) who were undergoing Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy at the Weight Loss Metabolism Clinic in Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital. All participants were at least 18 years old, had no other major illnesses, could read and understand the description of each item in the questionnaire, had normal cognitive function, and volunteered to participate. All participants in OW/OB group were followed up for 24 months after bariatric surgery.

The study and the survey obtained ethics approval by the independent IRB of the authors’ institution (Ethics Committee of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, NO 2020–219-(1)). Participants gave informed consent before taking part. Children and youth were not allowed to participate in the survey. All study procedures were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Measurements

Beck depression inventory II

Depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory II26,27a 21-item self-report measure of depression. Each of the 21 items is scored using a 4-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 0 to 63 and is compared to a key to determine the severity of depression. The Chinese version of the BDI scale had good internal consistency in our study.

Beck anxiety inventory

Anxiety was assessed using the BAI28a 21-item self-report measure of anxiety. Each of the 21 items is scored using a 4-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 0 to 63 and is compared to a key to determine the severity of anxiety.

Pittsburgh sleep quality index

Sleep quality was assessed using the PSQI29a self-report questionnaire that assesses sleep quality and disturbances over a 1-month time interval. It includes 18 items consisting of 7 components: subjective quality of sleep, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. The total score ranges from 0 to 21 and is compared to a key to assess the severity of the sleep issue.

Procedure

Based on the Chinese criteria for overweight and obesity, 78 patients with overweight or obesity were recruited into the OW/OB group and 65 individuals with healthy BMIs were recruited into the HC group. Both groups were asked to provide their baseline information. The OW/OB group was followed up and asked to fill out the BAI, BDI, and PSQI questionaries after bariatric surgery. The data were analyzed using bar charts, linear mixed models, and network analysis (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

Basic information and linear mixed model

Descriptive statistics were conducted as follows: normally distributed variables were analyzed using Student’s t-tests and reported as mean ± standard deviation; non-normally distributed variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test and reported as median and interquartile range (P25, P75). Sex distributions between groups were compared using the chi-square test. To assess longitudinal changes in anxiety, depression, and sleep quality after surgery, we used linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) with Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores as outcome variables. In the main models, time was treated as a continuous variable (months postoperatively) to examine overall trends, with a random intercept included for each participant to account for individual variability. The model formula was: BAI/BDI/PSQI ~ 1 + time + (1 | Participant ID).

To evaluate the effect of time on psychological outcomes across different periods, time was divided into five groups: baseline, 1–6, 7–12, 13–18, and 19–24 months after surgery. For additional insight, we performed two types of supplementary analyses: (1) within-person change score models, where ΔBAI, ΔBDI, and ΔPSQI were computed as the difference between each visit and the previous visit for each participant (i.e., value at time t minus value at time t–1), and all predictors were person-mean centered to isolate within-person effects; (2) multilevel cross-lagged regression, in which each outcome at time t + 1 (e.g., PSQI) was regressed on relevant predictors at time t (e.g., PSQI and BAI), with random intercepts for participants.

Network Estimation

Network models were created and analyzed with the quickNet (https://github.com/LeiGuo0812/quickNet) based on the EBICglasso method. In the network, In the network, BMI, BDI, BAI, and PSQI total scores were represented by nodes. Associations between nodes were represented by edges, and the width of the edge represents the magnitude of the partial correlation between the two nodes, with wider edges indicating stronger direct associations. Blue edges indicated positive associations, whereas red edges indicate negative associations30,31. Node size was scaled according to the Expected Influence (EI, the sum of all edge weights connected to a node while retaining the sign of the weights) of each node, with larger nodes indicating greater EI. Expected Influence quantifies both the extent to which a node is connected to the rest of the network and the magnitude and direction of its cumulative influence.

Network comparison

To explore the possible difference in global connectivity and examine the differences in the network before and after bariatric surgery in anxiety, depression and sleep quality. We compared the partial correlation network for the OW/OB group before and after bariatric surgery using the NetworkComparisonTest package in R32. we compared the correlation network at baseline with that at 18 months postoperatively 4.2.2. The comparison was based on a permutation procedure, and the number of permutations was 5000.

All analyses were performed using RStudio (R Foundation), jamovi version 2.3.26 and SPSS version 27.0.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

Group comparisons of the sociodemographic characteristics; the BMI; and the BAI, BDI, and PSQI scores are shown in Table 1. The BMI and BAI, BDI, and PSQI scores in the HC group significantly differed from those in the OW/OB group before surgery; Specifically, the OW/OB group had higher BAI, BDI, and PSQI scores. The median BAI score was significantly lower in the HC than OW/OB group (1.5 [0, 4] vs. 8 [4, 14], respectively; U = 1070.50, p < 0.001). Additionally, the median BDI score before surgery was significantly lower in the HC than OW/OB group (7 [3, 13] vs. 11 [6, 20], respectively; U = 1765.50, p < 0.001). The mean PSQI score was significantly higher in the HC than OW/OB group (8.71 ± 3.93 vs. 6.03 ± 3.37, respectively; t = − 4.38, p < 0.001). Although these differences were statistically significant, it is important to note that the median BAI and BDI scores in the OW/OB group still fell within the range generally considered to reflect mild levels of anxiety and depression. Similarly, their PSQI scores reflected relatively low sleep quality, though not reaching severe impairment thresholds. This distinction provides a more nuanced understanding of the baseline psychological burden among patients with obesity.

Alterations in BAI, BDI, and PSQI scores after bariatric surgery

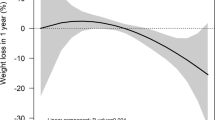

Figure 2 illustrates the modeled trajectories of psychological variables over time based on linear mixed models (LMMs), with time treated as a continuous variable. Detailed numerical results, including estimated marginal means and fixed-effect coefficients, are provided in Supplementary Tables S1–S9.

Compared to baseline, BAI scores showed a significant decrease from month 1 to month 24 (all p < 0.05; Supplementary Table S2). The lowest value observed at month 6 after surgery, but comparisons from month to month showed no statistically significant changes after the first month (Supplementary Table S3). This suggests that anxiety symptoms improved during the first postoperative month and then remained at a lower level.

Compared to baseline, BDI score did not showed a consistent decrease trend during the early postoperative period. At month 3, BDI scores were significantly higher than baseline (p = 0.035), suggesting a possible short-term emotional fluctuation after surgery. This increase was not sustained, and the scores subsequently fluctuated. A significant reduction was first observed at month 13 (p = 0.018), and significant decreases was also be found at months 15 (p = 0.017) and 18 (p = 0.007). However, no significant difference was observed at month 17 (p = 0.436), suggesting a possible fluctuation in symptom improvement. These results indicate a non-linear recovery pattern with variability over time (Supplementary Tables S4–S6).

Compared to baseline, PSQI scores significantly decreased from month 1 to month 18 (all p < 0.05), indicating an early improvement in sleep quality. No significant month-to-month changes were observed after the first month (Supplementary Table S8), suggesting that sleep quality improved early and then remained stable. At month 24, the PSQI score was no longer significantly different from baseline (p = 0.390), reflecting a partial rebound in sleep disturbances. Notably, the score at month 24 was significantly higher than that at month 18 (p = 0.045) (Supplementary Table S9). These findings suggest that sleep quality was improved after surgery and with a partial rebound observed in the later postoperative period.

To complement the month-by-month analyses, we also aggregated monthly data into broader intervals (semesters, Supplementary Tables S10–S12). Monthly analyses captured detailed short-term fluctuations, while semester-based analyses clarified longer-term trends. Anxiety (BAI) showed consistent and significant improvements across all postoperative semesters (all p < 0.05), confirming stable recovery. In contrast, depressive symptoms (BDI) did not significantly improve during the first semester (months 1–6, p = 0.840), with improvements becoming significant only in the second (months 7–12, p = 0.030) and third semesters (months 13–18, p = 0.003), but again became non-significant in the last semester (months 19–24, p = 0.510), indicating fluctuations rather than sustained stability. Similarly, sleep quality (PSQI) improved significantly during the first three semesters (all p < 0.001), but not in the last semester (months 19–24, p = 0.366), suggesting a partial rebound of sleep disturbances in the late postoperative period. Marginal R² values were relatively low across outcomes (BAI: 0.0446; BDI: 0.0139; PSQI: 0.0433), suggesting that time alone explained only a small portion of variance in psychological scores. In contrast, conditional R² values were substantially higher (BAI: 0.719; BDI: 0.795; PSQI: 0.622), indicating that between-subject variability played a major role in shaping psychological recovery.

Within-person change score models showed that individual improvements in anxiety and depression were each significantly associated with better sleep quality, and both contributed independently when included together (Supplementary Table S13). Multilevel cross-lagged regression models indicated that prior sleep quality and depression predicted subsequent changes in these outcomes, while anxiety showed weaker cross-lagged effects (Supplementary Table S14). We also examined whether participants’ years of education influenced psychological outcomes post-surgery. Linear mixed-effects models indicated that education level did not significantly affect changes in anxiety, depression, or sleep quality over time. These findings are summarized here, with detailed statistical results available in Supplementary Tables S15–S17.

Study design. Healthy controls and patients with OW/OB underwent baseline assessment. The OW/OB group was then followed up for 24 months after undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. The data were subsequently analyzed through mixed linear models, network analysis, and bar charts. OW/OB, overweight or obesity.

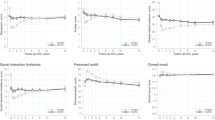

The stable network between BAI, BDI, and PSQI

The network model was used to explore the correlation between anxiety, depression, and sleep quality before surgery (Fig. 3). Node size was scaled according to Expected Influence (EI), with larger nodes indicating greater cumulative influence within the network. We used the NetworkComparisonTest package to compare differences in edge weights between the baseline and the 18 months postoperatively. Significant positive and negative correlations are shown in Fig. 4. the blue edges denote increased correlations between items, the red edges denote decreased correlations, and no edges indicate that no difference was found between network models. There was no alteration between baseline and 18 months postoperatively.

Network between Depression, anxiety, and sleep quality at baseline. (a) The network graph shows association and predictability estimate between depression, anxiety, and sleep quality. The edge width indicate the strength of the association between nodes. Blue edges indicate a positive correlation between nodes. Node size is proportional to the Expected Influence of each node, with larger nodes indicating greater cumulative influence within the network. (b) Expected Influence values for each node. BMI, body mass index; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Positive stable network between depression, anxiety, and sleep quality. Comparison of networks at (a) baseline and (b) 18 months postoperatively. The blue edges indicate an increased correlation, and the red edges indicate a decreased correlation. (c) No edges between the nodes indicates no increased or decreased correlation between network at baseline and 18 months postoperatively. BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to track monthly changes in anxiety, depression, and sleep quality after bariatric surgery. This observational cohort study explored the long-term alterations in anxiety, depression, and sleep quality after bariatric surgery and the correlation between anxiety, depression, and sleep quality.

In line with hypotheses 1 and 2, anxiety symptoms and sleep quality improved significantly, while the improvements in depression symptoms were delayed and less consistent. The improvement effect after surgery for anxiety, depression, and sleep quality is different. Anxiety and sleep quality showed rapid and sustained improvement, whereas depression followed a more complex trajectory. BDI scores were significantly higher at month 3 postoperatively, indicating early emotional fluctuation. The significant decline in BDI scores only emerged after 13 months, suggesting that improvements in depressive symptoms may require more than one year to manifest. Unlike anxiety and sleep—both of which appear more sensitive to early physiological and behavioral changes—depression may be more entrenched and dependent on broader psychosocial adaptation processes that unfold over longer periods. This delayed pattern highlights the importance of extended monitoring and interventions for depressive symptoms in postoperative care.

Clinically, our results suggest a need for tailored psychological support based on the recovery phase. Immediate postoperative efforts may focus on reducing anxiety and improving sleep quality, while structured, longer-term interventions may be necessary to address depressive symptoms, particularly from one year onward. Targeted mental health services—such as screening for residual depression at 12 months or beyond—may enhance overall quality of life and treatment outcomes.

Patients in the OW/OB group had worse levels of anxiety, depression, and sleep quality than those in the HC group before surgery, which is consistent with previous studies33,34,35. Although statistical comparisons revealed significantly higher BAI and BDI scores in the OW/OB group, these median scores remained within the mild symptom range according to established interpretative criteria for both scales. Thus, while psychological distress may be present, the data do not suggest a high burden of diagnosable psychiatric conditions preoperatively. Recognizing this helps avoid over-pathologizing the psychological state of individuals with obesity and underscores the importance of comprehensive evaluation in both research and clinical settings.

Consistent with previous literature, we found significant improvements in anxiety symptoms ppostoperatively36.The literature suggests that elevated proinflammatory cytokines, particularly C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin-6, are present in many patients with anxiety37,38,39. However, not all studies indicated that anxiety can be improvement after bariatric surgery. Rutledge et al. was found that no improvements on anxiety treatment involvement after surgery40. The number of studies found overall improvement in anxiety symptoms after surgery.

A previous study indicated that bariatric surgery can reduce the frequency of conditions that are associated with or cause sleep disruption and can improve sleep quality after surgery21,41,42. Sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) poor sleep quality show a high prevalence in obese adolescents43short duration can lead to weight gain and obesity, due to the potential alterations in hormonal activity and the increase awake time caused caloric intake44,45. One meta-analysis also found that improvement of OSA is more significantly for the individuals who received bariatric surgery than received traditional weight loss interventions18.

In this study, depression symptoms did not show significant improvement during the early postoperative period. This differs from some other studies showing that depressive symptoms can be improved after bariatric surgery15. Additionally, research has shown that not all patients with obesity who undergo bariatric surgery experience improvements in depression, and some patients experience no improvement in depressive symptoms or have an elevated BDI score46. Our monthly follow-up design provided greater temporal resolution to detect that depressive symptom improvement occurs only after one year in our cohort, suggesting a need to re-evaluate expectations for early emotional recovery in clinical practice. Our findings suggest that gender and baseline BMI may influence psychological recovery trajectories. Gender appeared to moderate improvements in sleep quality, while baseline BMI showed a marginal effect on anxiety symptoms.

Consistent with hypothesis 3, the Network analysis results indicated that a stable network among the anxiety, depression and sleep quality. This positive correlation between sleep disturbances, anxiety and depression, which is in line with the correlation between sleep disturbances and mental disorders8. changes in sleep and depression can predict future psychological states, while anxiety showed weaker prospective associations. In the clinical treatment of patients with obesity and anxiety/depression, interventions for anxiety and depression can be used to improve patient compliance and treatment efficacy. Network analysis further confirmed stable interconnections among anxiety, depression, and sleep quality, reinforcing the need for integrated treatment strategies.

Finally, while time accounted for a significant portion of symptom changes, marginal R² values were relatively low, suggesting that time alone explained only a small proportion of the variance. In contrast, high conditional R² values reflected substantial between-subject variability. This heterogeneity underscores the importance of unmeasured individual-level factors—such as psychological resilience, weight loss trajectory, and social support—in shaping recovery47. Future research should explore these factors to better model and personalize mental health outcomes after bariatric surgery.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the bariatric surgery group was not matched to the control group in terms of years of education. However, linear mixed-effects models indicated that education level did not significantly influence postoperative changes in anxiety, depression, or sleep quality. A brief summary of these results has been included in the Results section, with full details provided in Supplementary Tables S15–S17. Second, some patients may have had inadequate energy or time to complete the questionnaire on schedule, instead completing it a few days later than planned. Third, the sample size was small and all participants were from Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital. Finally, the data on postoperative weight were self-reported, which could have introduced bias.

Conclusion

In conclusion, bariatric surgery leads to early improvements in anxiety and sleep quality, while improvements in depressive symptoms emerge more slowly, typically one year postoperatively. A stable network of correlations between anxiety, depression, and sleep quality for patient with overweight or obesity before and after surgery. The relationship between bariatric surgery and mental health is very complex and requires more in-depth research.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the mendeley data repository, [https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/v7ym5f9y9z/1].

Abbreviations

- HC :

-

Healthy control

- OW/OB:

-

Overweight or obesity

- M:

-

Median

- P25:

-

25th percentile

- P75:

-

75th percentile

- p :

-

p value added the following abbreviations at this point: BDI Beck Depression Inventory II ; BAI Beck Anxiety Inventory; PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index;

References

Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 288–298 (2019).

Avila, C. et al. An overview of links between obesity and mental health. Curr. Obes. Rep. 4, 303–310 (2015).

Amiri, S. & Behnezhad, S. Obesity and anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr 33, 72–89 (2019).

Luppino, F. S. et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 67, 220 (2010).

Blüher, M. Metabolically healthy obesity. Endocr. Rev. 41, bnaa004 (2020).

Gariepy, G., Nitka, D. & Schmitz, N. The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. 34, 407–419 (2010).

Rajan, T. & Menon, V. Psychiatric disorders and obesity: A review of association studies. J. Postgrad. Med. 63, 182 (2017).

Alvaro, P. K., Roberts, R. M. & Harris, J. K. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep 36, 1059–1068 (2013).

Baglioni, C. et al. Sleep and mental disorders: A meta-analysis of polysomnographic research. Psychol. Bull. 142, 969–990 (2016).

Ma, Y., Peng, L., Kou, C., Hua, S. & Yuan, H. Associations of Overweight, Obesity and Related Factors with Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders and Snoring in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Survey. IJERPH 14, 194 (2017).

Dawes, A. J. et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery. JAMA 315, 150 (2016).

Adams, T. D. et al. Long-Term Mortality after Gastric Bypass Surgery. N Engl J Med 357, 753–761 (2007).

Arterburn, D. E. et al. Association between bariatric surgery and Long-term survival. JAMA 313, 62 (2015).

Gu, L. et al. A meta-analysis of the medium- and long-term effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. BMC Surg. 20, 30 (2020).

Woods, R. et al. Evolution of depressive symptoms from before to 24 months after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 24, e13557 (2023).

Gill, H. et al. The long-term effect of bariatric surgery on depression and anxiety. J. Affect. Disord. 246, 886–894 (2019).

Martin, D. J. et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on sleep architecture and quality: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. OBES. SURG. 35, 1070–1085 (2025).

Ashrafian, H. et al. Bariatric surgery or Non-Surgical weight loss for obstructive sleep apnoea?? A systematic review and comparison of Meta-analyses. OBES. SURG. 25, 1239–1250 (2015).

Jones, R. A. et al. The impact of adult behavioural weight management interventions on mental health: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews 22, e13150 (2021).

Van Den Hoek, D. J. et al. Mental health and quality of life during weight loss in females with clinically severe obesity: a randomized clinical trial. J Behav Med46, 566–577 (2023).

Lodewijks, Y., Schonck, F. & Nienhuijs, S. Sleep quality before and after bariatric surgery. OBES. SURG. 33, 279–283 (2023).

Borsboom, D. & Cramer, A. O. J. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 91–121 (2013).

Borsboom, D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 16, 5–13 (2017).

McNally, R. J. Can network analysis transform psychopathology? Behav. Res. Ther. 86, 95–104 (2016).

Fried, E. I. et al. Mental disorders as networks of problems: a review of recent insights. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 52, 1–10 (2017).

Beck, A. T. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 4, 561 (1961).

Smarr, K. L. & Keefer, A. L. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D), geriatric depression scale (GDS), hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), and patient health Questionna. Arthritis Care Res. 63, S454–S466 (2011).

Beck, A. T., Brown, G., Epstein, N. & Steer, R. A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 56, 893–897 (1988).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213 (1989).

Opsahl, T., Agneessens, F. & Skvoretz, J. Node centrality in weighted networks: generalizing degree and shortest paths. Social Networks. 32, 245–251 (2010).

Robinaugh, D. J., Millner, A. J. & McNally, R. J. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 125, 747–757 (2016).

Van Borkulo, C. D. et al. Comparing network structures on three aspects: A permutation test. Psychological Methods28, 1273–1285 (2023).

Fatima, Y., Doi, S. A. R. & Mamun, A. A. Sleep quality and obesity in young subjects: a meta-analysis: sleep quality and obesity. Obes. Rev. 17, 1154–1166 (2016).

Quek, Y. H., Tam, W. W. S., Zhang, M. W. B. & Ho, R. C. M. Exploring the association between childhood and adolescent obesity and depression: a meta-analysis: depression and obesity in childhood and adolescence. Obes. Rev. 18, 742–754 (2017).

Moradi, M., Mozaffari, H., Askari, M. & Azadbakht, L. Association between overweight/obesity with depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 555–570 (2022).

Tae, B. et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on depression and anxiety symptons, bulimic behaviors and quality of life. Rev. Col Bras. Cir. 41, 155–160 (2014).

Bankier, B., Barajas, J., Martinez-Rumayor, A. & Januzzi, J. L. Association between anxiety and C-Reactive protein levels in stable coronary heart disease patients. Psychosomatics 50, 347–353 (2009).

Duivis, H. E., Vogelzangs, N., Kupper, N., de Jonge, P. & Penninx, B. W. J. H. Differential association of somatic and cognitive symptoms of depression and anxiety with inflammation: findings from the Netherlands study of depression and anxiety (NESDA). Psychoneuroendocrinology 38, 1573–1585 (2013).

Pierce, G. L. et al. Anxiety independently contributes to elevated inflammation in humans with obesity: anxiety and inflammation in obesity. Obesity 25, 286–289 (2017).

Rutledge, T. et al. Five-Year changes in psychiatric treatment status and Weight-Related comorbidities following bariatric surgery in a veteran population. OBES. SURG. 22, 1734–1741 (2012).

Roberts, C. A. Physical and psychological effects of bariatric surgery on obese adolescents: A review. Front. Pediatr. 8, 591598 (2020).

Toor, P., Kim, K. & Buffington, C. K. Sleep quality and duration before and after bariatric surgery. OBES. SURG. 22, 890–895 (2012).

He, F. et al. Habitual sleep variability, mediated by nutrition intake, is associated with abdominal obesity in adolescents. Sleep Med. 16, 1489–1494 (2015).

St-Onge, M. P., Mikic, A. & Pietrolungo, C. E. Effects of diet on sleep quality. Adv. Nutr. 7, 938–949 (2016).

St-Onge, M. P. & Shechter, A. Sleep restriction in adolescents: forging the path towards obesity and diabetes?? Sleep 36, 813–814 (2013).

Ivezaj, V. & Grilo, C. M. When mood worsens after gastric bypass surgery: characterization of bariatric patients with increases in depressive symptoms following surgery. Obes. Surg. 25, 423–429 (2015).

Sarwer, D. B. & Heinberg, L. J. A review of the psychosocial aspects of clinically severe obesity and bariatric surgery. Am. Psychol. 75, 252–264 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Ke-Jia Wu, Xu-Ge Qi, Hui-Ting Cai for their help with data collection, data analysis and advice on writing the article.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (JZ-D) [82370901]; Shanghai Health Commission project (JZ-D) [NO. 20214098]; Shanghai Science and Technology Committee project (JZ-D) [NO. 22dz1204700]; and National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (JZ-D) [NO. 2022YFC2407004].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chuan-Yu Yin: data curation, formal analyses, methodology, visualization, writing-original draft. Hui-Lin Zhang: writing-reviewing and editing. Lin Liu: writing-reviewing and editing. Xu-Yan Ban: writing-reviewing and editing. Ting Xu, investigation, writing-reviewing and editing. Gang Peng: writing-reviewing and editing. Chen Wang: writing-reviewing and editing. Hong-Wei Zhang: writing-reviewing and editing. Xiao-Dong Han: supervision. Hui Zheng: conceptualization and project administration. Jian-Zhong Di: funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The study and the survey obtained ethics approval by the independent IRB of the authors’ institution (Ethics Committee of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, NO 2020–219-(1). Then, the participants gave informed consent before taking part. Children and youth were not allowed to participate in the survey. All study procedures were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, CY., Zhang, HL., Liu, L. et al. Immediate improvement in anxiety and sleep quality with delayed depression response after bariatric surgery in a longitudinal cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 32973 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17358-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17358-7