Abstract

Ovarian torsion (OT), a critical gynecological emergency caused by ovarian twisting and vascular compromise, risks necrosis without prompt intervention. This study evaluated dual-modal photoacoustic/ultrasound imaging for early detection and chronic hypoxia monitoring in OT. Rat models of complete/partial OT were established, with photoacoustic imaging (PAI) tracking tissue oxygen saturation (sO₂) over time, compared to color Doppler parameters (color pixel density [CPD]) and spectral Doppler parameters (peak systolic velocity [PSV], resistance index [RI]). In short-term (6-hour) torsion, PAI and CPD showed similar declining trends, but PAI provided superior sO₂ quantification. In long-term models, PAI detected significant sO₂ reductions at 12 and 24 h, whereas CPD declined only within the first 12 h, highlighting PAI’s enhanced accuracy for hypoxia assessment during the 12–24 h window. Histological analysis confirmed that PAI-measured hypoxia correlated with tissue injury severity. These findings demonstrate PAI’s reliability in evaluating hypoxia progression and tissue damage, facilitating precise early diagnosis and time-sensitive monitoring in prolonged OT. Combining ultrasound with PAI offers a more effective diagnostic tool for assessing OT progression, particularly in guiding timely interventions for long-term torsion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian torsion (OT) occurs when the adnexa and its supporting ligaments twist, leading to impaired ovarian blood flow1,2. It can be classified into complete and partial torsion, with or without an accompanying adnexal mass. OT accounts for approximately 3% of gynecological emergencies, with an incidence of 9.9 cases per 100,000 women of reproductive age and 2.7% of pediatric abdominal pain cases3,4. If left untreated, OT can lead to ischemic necrosis, infertility, and life-threatening complications5. Diagnosis is particularly challenging in pediatric cases, where atypical symptoms and communication barriers further complicate the evaluation. Early diagnosis and prompt intervention are crucial for preserving ovarian function, but due to the nonspecific nature of symptoms, surgical confirmation is often required, leading to delayed6.

Despite the availability of Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as diagnostic tools, they have certain limitations, including radiation exposure and prolonged imaging procedures7,8. Despite being the most utilized diagnostic tool in clinical practice, Utrasound Imaging (USI) exhibits considerable variability in sensitivity (46%-74%), primarily attributed to technical constraints and operator-dependent factors9,10,11. One critical technical factor is the transducer bandwidth: narrower bandwidth limits axial resolution and reduces the system’s capability to accurately differentiate small or deeply located structures, thereby increasing measurement uncertainty12,13. Additionally, beam steering errors—arising from transducer array limitations or inaccuracies in beamforming algorithms—can introduce spatial distortions and imaging artifacts, which compromise the fidelity of tissue characterization14,15. Patient-specific factors further complicate measurement accuracy; variations in anatomical geometry and body habitus, including obesity and difficulty in maintaining optimal probe contact, adversely affect acoustic coupling and signal quality16,17. Moreover, patient movement during scanning introduces additional signal variability. Operator-dependent factors, such as proficiency in probe positioning, applied pressure, and experience with real-time image interpretation, significantly influence image quality and reproducibility, contributing further to sensitivity discrepancies18,19,20. To mitigate these challenges, advancements in probe design, automated scanning protocols, and standardized training are critical to improve USI reliability and reduce operator-related biases. Furthermore, conventional imaging techniques cannot directly assess tissue oxygen saturation (sO₂), making it challenging to effectively evaluate tissue hypoxia21. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a more sensitive method to evaluate the duration of ovarian ischemia and the severity of tissue hypoxia, both of which are crucial for the accurate diagnosis of OT. Such a method would provide essential support for clinical decision-making, assisting surgeons in determining whether ovarian detorsion or oophorectomy is required.

Dual-modal photoacoustic and ultrasound Imaging offers unique advantages by combining structural and functional imaging22,23. It quantifies sO₂ through non-invasive detection of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin, enabling real-time monitoring of tissue sO₂24,25,26.

Experiments by Mengyu Zhou et al. have shown that photoacoustic imaging (PAI) can accurately diagnose testicular torsion in its early stages27. Research by Sugiura et al. demonstrated that PAI can continuously monitor sO₂ recovery after reperfusion in a rat model of acute mesenteric ischemia28. Additionally, Hallasch et al. found that PAI, by assessing tissue sO₂, can detect the early stages of psoriatic arthritis29. Although PAI has shown potential in other ischemic diseases, its application in OT remains relatively limited. We innovatively applied high-resolution PAI to the long-term ovarian torsion model, and systematically evaluated its advantages in hypoxia monitoring and determination of tissue functional status by comparing with traditional ultrasound means, aiming to achieve more accurate judgment of ischemia duration and assessment of the degree of tissue damage, and thus provide a more instructive imaging basis for clinical treatment decisions.

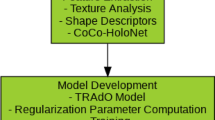

The prognosis and successful treatment of OT are significantly influenced by the extent of ovarian hypoxia30. This study employs dual-modal photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging for in vivo quantification of tissue sO₂ in OT rat model. By establishing animal models and conducting in vivo experiments, the changes in ovarian tissue sO₂ over time were evaluated (Fig. 1). We hypothesize that the application of PAI for tissue sO₂ assessment (Table 1) could provide a novel approach for the early diagnosis of OT and the evaluation of tissue damage in chronic cases. This study (Fig. 2) aims to (1) validate dual-modal PAI/USI for early OT diagnosis, (2) quantify hypoxia progression in partial vs. complete torsion, and (3) correlate PAI sO₂ with histopathology. Our findings demonstrate PAI’s superiority in detecting prolonged hypoxia, supporting its integration into clinical workflows for timely intervention.

Results

Color Doppler Flow Imaging (CDFI) of OT rat models within 6 h

During the 6-hour observation period, ovarian blood flow was assessed by measuring Color Pixel Density (CPD) in ovarian parenchyma (Fig. 3; Table 2). While the normal group maintained stable blood flow (Fig. 3a, b; Table 2), the 180° torsion group showed a significant reduction at 2 h post-torsion compared to normals and pre-torsion levels (P < 0.05), with a progressive but non-significant decline thereafter (Fig. 3a, c; Table 2). In contrast, the 360° torsion group exhibited undetectable blood flow from 2 h post-torsion onward (Fig. 3a, d; Table 2). In addition, anatomical landmark CPD images (Supplementary Fig. 1) are labeled for the reader’s understanding.

CDFI of Ovarian Blood Flow Changes in the Early Stage of OT Model. (a) Representative CDFI showing ovarian blood flow in the normal group, 180° partial torsion group, and 360° complete torsion group at pre-torsion (0 h) and post-torsion time points (2, 4, and 6 h). Panels (b-d) present quantifiable linear graphs illustrating the relative CPD values at various time points for the normal group, the partial torsion group (180°), and the complete torsion group (360°), respectively. The scale bar represents 1 mm. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences compared to the 0-hour time point (P < 0.05).

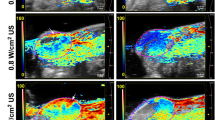

PAI-based sO₂ mapping in OT rat models during 6-hour observation

To quantify temporal changes in ovarian tissue oxygen saturation (sO₂) over a 6-hour period, sO₂ levels were measured, and the results are presented in Fig. 4; Table 3. In the normal group, sO₂ distribution remained relatively stable throughout the observation period (Fig. 4a, b; Table 3). In the 180° torsion group, sO₂ levels decreased significantly within the first two hours (P < 0.05), followed by a gradual but statistically insignificant decline over the remaining 4 h (Fig. 4a, c; Table 3). In contrast, the 360° torsion group demonstrated a more pronounced reduction in sO₂ during the initial 2 h, with levels stabilizing thereafter (Fig. 4a, d; Table 3). Notably, the decline in sO₂ was significantly greater in the 360° group compared to the 180° torsion group (P < 0.05).

PAI of sO₂ in early OT models. (a) Ultrasound grayscale images and corresponding sO₂ maps for the normal group, partial torsion group (180°), and complete torsion group (360°), captured before torsion (0 h) and at 2, 4, and 6 h post-torsion. The ovarian region is delineated by dashed lines. (b-d) Quantitative line graphs depicting relative sO₂ levels for the normal group, 180° (partial torsion) group, and 360° (complete torsion) group at each time point. Scale bar: 1 mm. *Indicates statistically significant differences compared to the 0-hour time point (P < 0.05).

Pulsed wave (PW) doppler analysis of partial OT rat models (within 6 h)

In complete OT, blood flow signals were absent within 2 h, rendering PW Doppler measurements unfeasible. To assess the diagnostic utility of PW Doppler in a partial OT rat model, we quantified the ovarian artery Peak Systolic Velocity (PSV) and Resistance Index (RI) at 2, 4, and 6 h hours post-torsion and compared these values with baseline (pre-torsion) measurements.

As shown in Fig. 5a, b, before torsion, the PSV was 67.21 ± 14.54 which decreased to 60.73 ± 7.80 at 2 h, 59.65 ± 9.56 at 4 h, and 51.63 ± 11.23 at 6 h. The RI values before torsion and at 2, 4, and 6 h after torsion were 59.88% ± 4.87%, 54.56% ± 2.34%, 51.87% ± 3.14%, and 54.42% ± 5.35%, respectively (Fig. 5a, c). Compared to the baseline values before torsion, the changes in PSV and RI at different time points did not reach statistical significance.

Spectral Doppler USI evaluation of partial OT models at 0 h (pre-torsion) and 2, 4, and 6 h post-torsion. Panel (a) shows the spectral Doppler USI images of partial OT models at 0 h (pre-torsion) and at 2, 4, and 6 h post-torsion. Panel (b) presents the boxplot of PSV in the ovarian artery, while panel (c) displays the boxplot of the RI in the ovarian artery. Data are presented as box-and-whisker plots, with the box representing the 25th and 75th percentiles and the whiskers indicating the minimum and maximum values.

PAI of long-term partial OT rat models

Evaluating tissue viability in long-term partial OT rat model and determining the feasibility of ovarian preservation surgery remain critical clinical challenges. In this study phase, we aimed to explore the utility of PAI in measuring tissue sO₂ as a biomarker of ovarian viability and its potential to guide ovarian preservation strategies.

Figure 6a, b illustrates the progressive decline in tissue sO₂ levels in partial OT groups over time: normal group, 60.86% ± 1.846; 6-hour partial OT group, 54.12% ± 0.37; 12-hour partial OT group, 52.29% ± 1.37; and 24-hour partial OT group, 47.26% ± 3.94. Significant differences were observed between the normal and 6-hour groups (P = 0.05), 6-hour and 12-hour groups (P = 0.016), and 12-hour and 24-hour groups (P = 0.035). These findings demonstrate the utility of PAI for continuous monitoring of ovarian tissue function during partial torsion.

CDFI of long-term partial OT rat models

CDFI was performed in parallel with PAI to enable comparative analysis. The ovarian CPD measurements in the partial OT models demonstrated progressive changes across experimental groups (Fig. 7a, b). Quantitative analysis revealed CPD values of 10.60% ± 2.33 in normals, which decreased to 4.40% ± 1.99, 2.52% ± 2.026, and 2.23% ± 1.176 in the 6-hour, 12-hour, and 24-hour partial torsion groups, respectively. Statistical evaluation using appropriate tests showed significant differences in CPD values between the normal group and both 6-hour and 12-hour torsion groups (P < 0.05). However, no statistically significant difference was detected when comparing the 12-hour and 24-hour torsion groups (Fig. 7b), suggesting a potential plateau in CPD reduction after 12 h of partial torsion.

Ultrasound (US) and Photoacoustic (PA) sO₂ results of prolonged normal, torsion, and recovery in partial and complete OT rat models

As shown in Fig. 8a, compared with the normal group, partial OT resulted in a significant decrease in sO2 signals at both 12 h and 24 h post-torsion. Following ovarian detorsion (Fig. 8b), the sO2 signal at 12 h significantly increased and approached baseline levels, showing no significant difference compared to the normal group (P = 0.3825). However, despite an increase in sO2 signals after 24 h partial OT detorsion (Fig. 8c), values remained significantly lower than those of the control group (P < 0.0001). Similarly, as depicted in Fig. 9a, complete OT induced a pronounced reduction in sO2 signals at both 12 h and 24 h compared to normal ovaries (12 h: P = 0.0005; 24 h: P < 0.0001). Although sO2 signals improved post-detorsion (Fig. 9b, c), they remained significantly different from normal values with quantified results revealing statistically significant differences at both time points (12 h: P < 0.0001; 24 h: P < 0.0001).

US and PA sO₂ results of prolonged normal, torsion, and recovery in partial OT rat model. (a) Partial OT at 12 h and 24 h US and PA sO₂ plots. (b) Quantitative analysis of sO₂ levels based on the PAI images in 12 h. (c) Quantitative analysis of sO₂ levels based on the PAI images in 24 h. Scale bar: 2 mm.

US and PA sO₂ results of prolonged normal, torsion, and recovery in complete OT rat model. (a) Complete OT at 12 h and 24 h US and PA sO₂ plots. (b) Quantitative analysis of sO₂ levels based on the PAI images in 12 h. (c) Quantitative analysis of sO₂ levels based on the PAI images in 24 h. Scale bar: 2 mm.

Analysis of tissue section results

In this experiment, histomorphologic changes were observed in normal ovarian tissues by twisting them to different degrees and for different durations (Fig. 10). In normal ovaries, follicles were morphologically intact, granulosa cells were well arranged, and oocytes were in the center, surrounded by a single layer of flattened granulosa cells, and the outermost layer was surrounded by the basement membrane. In the partially twisted 180° group (12 h and 24 h), separation of the oocyte from the basement membrane was observed, and the granulosa cell morphology gradually changed from flat to rounded, however, no obvious edema formation was observed. In contrast, in the group treated with full 360° torsion, a high degree of edema was observed at 12 h, which was further aggravated at 24 h, and the cellular morphology also changed significantly, indicating that severe torsional injury could lead to significant disorganization of the ovarian tissue structure and cellular morphology abnormalities.

Discussion

OT is a critical obstetric and gynecological emergency requiring prompt diagnosis and intervention to preserve ovarian function31,32. The severity of tissue hypoxia and the duration of torsion are pivotal factors influencing clinical decision-making10. However, diagnosing OT remains challenging due to its non-specific symptoms, such as acute abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. This difficulty is exacerbated in pediatric and adolescent patients, who may have limited ability to communicate their symptoms, making it harder for clinicians to accurately assess the duration of torsion and the extent of ovarian hypoxia.

USI, a widely used diagnostic tool for OT, is non-invasive, radiation-free, and efficient. While USI demonstrates high diagnostic accuracy for complete OT, its performance in detecting partial OT is less reliable, often yielding false-negative results. Furthermore, Additionally, the classic diagnostic signs of USI, such as the whirlpool sign, can be influenced by the operator’s skill, leading to variability in diagnostic sensitivity.

In contrast, PAI, an emerging imaging modality, offers unique advantages by generating detailed sO₂ maps, providing functional insights into tissue hypoxia33. PAI is user-friendly and enables quantitative assessment of tissue sO₂, significantly enhancing its diagnostic potential for OT.

This study investigated the application of PAI in monitoring ovarian ischemia using an animal model. The results demonstrated that PAI not only effectively diagnoses both complete and partial OT but also exhibits strong concordance with USI findings. Importantly, PAI outperformed USI in evaluating tissue hypoxia. In the complete OT group, CPD values dropped to zero within two hours post-torsion, rendering USI ineffective for assessing tissue sO₂. In contrast, PAI revealed a marked decrease in tissue sO₂ within the initial two hours, with no further alterations noted between two and six hours, highlighting its efficacy in quantifying tissue hypoxia. These findings confirm that while USI is effective for diagnosing complete OT, integrating PAI provides a more accurate assessment of ovarian tissue hypoxia.

In the partial OT model, CPD values at 2, 4, and 6 h showed a statistically significant decrease compared to baseline (0 h). However, clinical studies have highlighted that CPD measurements are influenced by the angle of the ultrasound beam, limiting their precision7. Similarly, PW Doppler analysis revealed a decline in PSV and RI of the ovarian artery at 2, 4, and 6 h, though these changes were not statistically significant. These results suggest that spectral Doppler has limited sensitivity in diagnosing partial OT.

Although the combined presentation of B-mode ultrasound, Doppler, and PAI images is helpful for visual comparison of different imaging modalities, in practice, combining three images with different fields of view into a single image may result in some of the detailed information being overlooked (Supplementary Fig. 2). To fully retain the rich information in each image, this paper chooses to present the images in different fields of view separately, to more comprehensively demonstrate the diagnostic features of each imaging modality and its complementary advantages.

PAI demonstrated superior performance in the partial OT rat model, revealing a progressive reduction in tissue sO₂ levels at 2, 4, and 6 h. Unlike USI, PAI is unaffected by the angle of the ultrasound beam, facilitating quantitative analysis of changes in oxygenated hemoglobin. This feature overcomes the angle-dependent limitations of color Doppler imaging, significantly enhancing diagnostic accuracy for partial OT, particularly in quantifying tissue sO₂ levels.

Comparative analysis among the normal, partial torsion, and complete torsion groups demonstrated statistically significant differences in tissue sO₂ values across all groups. These findings highlight PAI’s high precision in assessing the degree of ovarian tissue hypoxia, particularly in the early diagnosis of OT.

For partial OT, surgical intervention within 24 h can potentially salvage the affected ovary31. However, the lack of reliable tools to assess the extent of ovarian damage complicates surgical decision-making34. To evaluate PAI’s utility in assessing long-term OT, this study conducted a second-phase experiment, establishing partial OT models (180°) at 6, 12, and 24 h and comparing them with a normal group.

PAI results demonstrated a progressive decrease in ovarian tissue sO₂ across the normal group, 6-hour, 12-hour, and 24-hour partial torsion groups (Fig. 7). Quantitative analysis revealed statistically significant differences in sO₂ values between the normal group and the 6-hour group, the 6-hour and 12-hour groups, and the 12-hour and 24-hour groups. These differences correlated positively with the duration of torsion, underscoring PAI’s ability to estimate the duration of partial OT and assess hypoxia severity. In contrast, CDFI failed to detect significant changes between the 12-hour and 24-hour groups, indicating its inability to assess prolonged OT beyond 12 h.

PA sO2 measurements demonstrate that short-term (12 h) partial OT can restore oxygenation to near-normal levels with no significant difference compared to the control. In contrast, complete OT results in persistent hypoxia even after detorsion. Moreover, prolonged partial OT (24 h) also leads to severe irreversible damage. These findings underscore the critical need for sensitive and high-resolution early diagnostic techniques such as PAI to enable timely detection and intervention in OT. The histological results showed that different twisting angles and time had significant effects on the pathological changes of ovarian tissue, and the damage caused by full 360° twisting was more serious than partial twisting. The histological results showed that different twisting angles and time had significant effects on the pathological changes of ovarian tissue, and the damage caused by full 360° twisting was more serious than partial twisting.

These findings highlight PAI’s clinical value in guiding surgical planning and improving outcomes for OT patients, particularly adolescents. By integrating PAI with USI and clinical assessments, unnecessary oophorectomies can be avoided, preserving ovarian function.

The PAI/USI hybrid imaging platform combines the superior optical contrast of photoacoustics with the deep tissue penetration of ultrasound, enabling simultaneous acquisition of anatomical and functional tissue data. This system not only visualizes the anatomical distribution of hypoxic regions but also provides quantitative sO₂ values35,36,37. These features assist surgeons in estimating the duration of OT and formulating appropriate surgical plans. Additionally, PAI’s ease of operation reduces detection time and minimizes reliance on operator experience.

Despite the promising results, several challenges remain for the clinical implementation of PAI. First, the optical penetration depth of current PAI devices is limited, and standardized clinical equipment is lacking38.

Future advancements should focus on developing intracavitary probes to reduce the distance between the imaging probe and the ovary. Additionally, the development of portable and user-friendly PAI systems will facilitate broader clinical adoption and application. PAI system used in this article is a high-frequency small animal photoacoustic/ultrasound fusion imaging device that excels in life sciences and medical research due to its high resolution (~ 50 μm axial, ~ 110 μm lateral) and deep imaging penetration (1–2 cm). The accompanying probe design encompasses a 33 MHz ultrasound transducer, which effectively balances ultrasound and photoacoustic signal acquisition. The laser light path is typically delivered by fiber optics. Optimization of the size and structure of the fiber optics allows for more compact and efficient laser coupling, which is conducive to reducing the size of the probe, even for endoscopic or interventional applications. PAI systems leveraging existing US infrastructure reduce expenses. Integration with clinical US devices for real-time sO₂ mapping.

Future clinical applications must address several key challenges. Enhancing light delivery efficiency through advanced fiber-optic designs, implementing adaptive image reconstruction algorithms, and integrating complementary modalities such as transvaginal ultrasound probes with embedded optical components may improve depth penetration and signal quality. Furthermore, the use of exogenous contrast agents with higher optical absorption or targeted molecular probes could enhance PA contrast at clinically relevant depths. In summary, while our system demonstrates promising preclinical results, clinical translation will necessitate technological advancements to overcome inherent optical and anatomical barriers intrinsic to human pelvic imaging.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the significant potential of PAI in the early diagnosis and long-term assessment of OT. By accurately quantifying tissue sO₂, PAI provides a more reliable evaluation of tissue hypoxia compared to traditional color Doppler ultrasound, particularly in partial torsion cases where ultrasound sensitivity is limited. The ability of PAI to continuously monitor oxygen levels over time offers critical insights into the extent of ovarian damage, aiding in timely surgical decision-making and potentially preserving ovarian function. The integration of PAI with ultrasound imaging enhances diagnostic accuracy, especially in pediatric and adolescent cases where symptoms are often non-specific.

Methods

Animal model

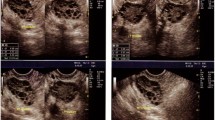

In this study, SPF-grade female SD rats (4–5 weeks old, weighing 100–120 g) were used to establish an OT model. The animals were provided by Guangdong Zhiyuan Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). After anesthesia was induced with an intraperitoneal injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg), surgery was performed using sterile techniques. A longitudinal midline abdominal incision was made to expose the abdominal cavity. The intestines were gently moved aside, and the right uterus and its appendages were located. The right ovary was torsed and fixed to the peritoneum below the right kidney using sutures (Supplementary Fig. 3). After successful surgery, USI was performed to capture the long-axis and cross-sectional views of the twisted ovarian pedicle. The long-axis view showed crossed blood flow in the pedicle, while the cross-sectional view revealed a vortex-like blood flow, confirming the ovarian pedicle torsion (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). We established a complete OT model (360° torsion of the ovarian pedicle), where color Doppler confirmed the absence of significant blood flow signals. A partial OT model (180° torsion of the ovarian pedicle) retained partial blood flow signals, which were decreased compared to the normal group (P < 0.05)39. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Zhiyuan Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd. (AL07155). This study is performed in accordance with relevant national regulations. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Experimental protocol

Animals were randomized into torsion severity groups (complete/partial) using a block design. This study was conducted in two phases: the first phase focused on the early diagnosis of OT at different degrees within the first 6 hours, while the second phase evaluated ovarian damage in partial torsion cases over 24 hours. Both phases employed dual-modal photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging, and the PAI results were compared with the outcomes of color Doppler and spectral Doppler ultrasound imaging.”

In the first-phase experiment, 15 mice were randomly assigned to three groups: the normal group (sham surgery, n = 3), the partial torsion group (180° right OT, n = 6), and the complete torsion group (360° right OT, n = 6). At 0 h (pre-torsion), 2 h, 4 h, and 6 h, dual-modal photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging were performed. PAI was used to monitor sO₂ and obtain the ovarian sO₂ map40. Additionally, color Doppler and spectral Doppler techniques were used to monitor changes in ovarian blood flow, as well as changes in ovarian artery PSV and RI.

In the second-phase experiment, 24 rats were randomly assigned to four groups: the normal group (normal rats), the 6-hour partial OT group, the 12-hour partial OT group, and the 24-hour partial OT group. For ethical reasons, the data from the 6-hour partial OT group in the first phase were directly included in the second-phase experiment. During the experiment, PAI was used to assess ovarian tissue sO₂ and acquire sO₂ map, while USI was employed to capture color CDFI to monitor local hemodynamic parameters (CPD) in the different partial OT model groups.

Explanation of the deviations associated with the doppler shift control angle

To minimize angle-related bias in our experiments, all Doppler measurements were performed using a vertical imaging approach, where the ultrasound beam is as close as possible to being parallel to the expected predominant blood flow direction. Specifically, the probe was positioned such that the insonation angle θ remained close to 0°, or at least well below 20°, where cosine-related errors are minimal and velocity estimates remain reliable. This vertical imaging configuration effectively reduces Doppler angle dependence and improves measurement consistency.

Moreover, the PAI system incorporates real-time angle correction tools allowing operators to adjust calculation parameters based on the estimated flow direction. Combined with careful probe positioning and stabilization during acquisition, these measures ensured that angle-related deviations were controlled to the greatest extent possible.

Dual-modal photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging for OT

First, the ovary was twisted by open surgery, followed by suture fixation, and finally, imaging acquisition was performed. The laser fluence was maintained below the ANSI safety limits for small animal imaging (≤ 20 mJ/cm²), ensuring safe and consistent illumination. The acquisition settings involved a sampling rate of 128 MHz with a maximum photoacoustic frame rate of 20 frames per second. Wavelength tuning was performed in 1 nm steps within the range of 680 to 970 nm to optimize the spectral contrast for oxygen saturation measurements. For image reconstruction, we employed a standard delay-and-sum beamforming algorithm integrated in the PAI system software, with default parameters optimized for high spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio. Post-processing included spectral unmixing for sO₂ quantification, which was conducted using a built-in linear regression method based on known absorption spectra of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin.

Dual-modal photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging of OT was performed using Vevo 3100 system (FUJIFILM VisualSonics, Canada) and Vevo® LAZR-X system (FUJIFILM VisualSonics, Canada) equipped with a broadband transducer (MX400: 18–38 MHz; center frequency: 30 MHz). Among them, data collection in Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 used the Vevo 3100 imaging platform. Subsequent figures (Figs. 8 and 9) used the Vevo® LAZR-X system. Dual-wavelength PAI at 750 nm and 850 nm was utilized to quantify sO₂ in biological tissues. This method is based on the differential molar extinction coefficients of deoxyhemoglobin (HbR) and oxyhemoglobin (HbO₂)41. In addition, USI was utilized to acquire CPD and measure the ovarian artery’s PSV and RI using spectral Doppler mode.

Histological analysis

At the end of imaging, mice were euthanized (Gradual injection of CO₂ (30–70% over 4 min) followed by a quick guillotine), ovaries were extracted and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Paraffin-embedded and sectioned, the tissue sections were then stained and the images were scanned for analysis.

Statistical analysis

The Kruskal-Wall is test was used to evaluate significant differences among the normal group, partial torsion group, and complete torsion group within the OT model over a 6-hour period. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to further analyze changes within each group. For the partial torsion (180°) group, the Friedman test was employed to assess differences in PSV and RI across time points (0, 2, 4, and 6 h).

Additionally, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to analyze intergroup differences in sO₂ and CPD values under prolonged OT. All statistical analyses were performed using the SciPy library in Python, including Kruskal-Wallis, Friedman, and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, to ensure comprehensive nonparametric evaluation of both intergroup and intragroup differences.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mandelbaum, R. S. et al. Conservative surgery for ovarian torsion in young women: perioperative complications and national trends. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 127, 957–965. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16179 (2020).

Akdam, A. et al. Recurrent ovarian torsion: risk factors and predictors for outcome of oophoropexy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 29, 1011–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2022.05.007 (2022).

Wattar, B. et al. Accuracy of imaging modalities for adnexal torsion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 128, 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16371 (2021).

Tielli, A. et al. Ovarian torsion: diagnosis, surgery, and fertility preservation in the pediatric population. Eur. J. Pediatr. 181, 1405–1411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04352-0 (2022).

Nur Azurah, A. G. et al. Update on the management of ovarian torsion in children and adolescents. World J. Pediatr. 11, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-014-0536-3 (2015).

Sandrieser, L., Perricos, A., Husslein, H., Wenzl, R. & Kuessel, L. Fertility preserving management of ovarian torsion. Fertil. Steril. 120, 1257–1258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.08.012 (2023).

Dawood, M. T. et al. Adnexal torsion: review of radiologic appearances. Radiographics 41, 609–624. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2021200118 (2021).

Duigenan, S., Oliva, E. & Lee, S. I. Ovarian torsion: diagnostic features on CT and MRI with pathologic correlation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 198, W122–131. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.10.7293 (2012).

Garde, I. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound signs for detecting adnexal torsion: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecology: Official J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 61, 310–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.24976 (2023).

Nakamata, A. et al. Imaging features of uncommon entities that manifest with torsion. Radiographics 44, e230101. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.230101 (2024).

Peña, J. E., Ufberg, D., Cooney, N. & Denis, A. L. Usefulness of Doppler sonography in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Fertil. Steril. 73, 1047–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00487-8 (2000).

Zhang, Y., Mao, S. & Zhang, F. Evaluating the role and diagnostic performance of ultrasound in diagnosing soft tissue tumors and pseudotumors in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Med. Dev. 21, 841–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/17434440.2024.2393349 (2024).

Kothapalli, S. R. et al. Simultaneous transrectal ultrasound and photoacoustic human prostate imaging. Sci. Transl. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aav2169 (2019).

Ma, J., Ma, X. & Xu, L. Optical ultrasound sensing for biomedical imaging. Measurement 200, 111620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111620 (2022).

Nandy, S. et al. Evaluation of ovarian cancer: initial application of coregistered photoacoustic tomography and US. Radiology 289, 740–747. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018180666 (2018).

Sharma, H. et al. Knowledge representation and learning of operator clinical workflow from full-length routine fetal ultrasound scan videos. Med. Image. Anal. 69, 101973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2021.101973 (2021).

Oh, D., Kim, H., Sung, M. & Kim, C. Video-rate endocavity photoacoustic/harmonic ultrasound imaging with miniaturized light delivery. J. Biomed. Opt. 29 https://doi.org/10.1117/1.Jbo.29.S1.S11528 (2024).

Christensen-Jeffries, K. et al. Super-resolution ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound. Med. Biol. 46, 865–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.11.013 (2020).

Qu, Y. et al. Transvaginal fast-scanning optical-resolution photoacoustic endoscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 23, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.Jbo.23.12.121617 (2018).

Shengfeng, L. et al. Deep learning in medical ultrasound analysis: A review. Engineering 5, 261–275 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2018.11.020

Lv, J., Xu, Y., Xu, L. & Nie, L. Quantitative functional evaluation of liver fibrosis in mice with dynamic contrast-enhanced photoacoustic imaging. Radiology 300, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2021204134 (2021).

Wang, Z., Yang, F., Zhang, W. & Yang, S. Quantitative and anatomical imaging of human skin by noninvasive photoacoustic dermoscopy. Bio Protoc. 12, e4372. https://doi.org/10.21769/BioProtoc.4372 (2022).

Zhang, J., Duan, F., Liu, Y. & Nie, L. High-Resolution photoacoustic tomography for early-stage cancer detection and its clinical translation. Radiol. Imaging Cancer. 2, e190030. https://doi.org/10.1148/rycan.2020190030 (2020).

Cao, R. et al. Hemodynamic and oxygen-metabolic responses of the awake mouse brain to hypercapnia revealed by multi-parametric photoacoustic microscopy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 41, 2628–2639. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678x211010352 (2021).

Sun, N. et al. Development of a photoacoustic microscopy technique to assess peritubular capillary function and oxygen metabolism in the mouse kidney. Kidney Int. 100, 613–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2021.06.018 (2021).

Gerling, M. et al. Real-time assessment of tissue hypoxia in vivo with combined photoacoustics and high-frequency ultrasound. Theranostics 4, 604–613. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.7996 (2014).

Zhou, M. et al. Visualizing the early-stage testicular torsion by dual-modal photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging. Photoacoustics 31, 100523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacs.2023.100523 (2023).

Sugiura, T. et al. Predicting intestinal viability by consecutive photoacoustic monitoring of oxygenation recovery after reperfusion in acute mesenteric ischemia in rats. Sci. Rep. 11, 19474. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98904-x (2021).

Hallasch, S., Giese, N., Stoffels, I., Klode, J. & Sondermann, W. Multispectral optoacoustic tomography might be a helpful tool for noninvasive early diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis. Photoacoustics 21, 100225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacs.2020.100225 (2021).

Psilopatis, I. et al. Ovarian torsion in polycystic ovary syndrome: A potential threat? Biomedicines 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11092503 (2023).

Dasgupta, R. et al. Ovarian torsion in pediatric and adolescent patients: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Surg. 53, 1387–1391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.10.053 (2018).

Bar-On, S. et al. Emergency laparoscopy for suspected ovarian torsion: are we too hasty to operate? Fertil. Steril. 93, 2012–2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.022 (2010).

Chen, J. et al. Expanded porphyrins: functional photoacoustic imaging agents that operate in the NIR-II region. Chem. Sci. 12, 9916–9921. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1sc01591e (2021).

Ryles, H. T., Hong, C. X., Andy, U. U. & Farrow, M. R. Changing practices in the surgical management of adnexal torsion: an analysis of the National surgical quality improvement program database. Obstet. Gynecol. 141, 888–896. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000005142 (2023).

Xie, Z. et al. In vivo assessment of inflammation in carotid atherosclerosis by noninvasive photoacoustic imaging. Theranostics 10, 4694–4704. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.41211 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Aggregation-Induced absorption enhancement for deep Near-Infrared II photoacoustic imaging of brain gliomas in vivo. Adv. Sci. (Weinheim Baden-Wurttemberg Germany). 6, 1801615. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201801615 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Noninvasive photoacoustic computed tomography/ultrasound imaging to identify high-risk atherosclerotic plaques. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 49, 4601–4615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-022-05911-9 (2022).

Mantri, Y. & Jokerst, J. V. Impact of skin tone on photoacoustic oximetry and tools to minimize bias. Biomed. Opt. Express. 13, 875–887. https://doi.org/10.1364/boe.450224 (2022).

Chang, H. C., Bhatt, S. & Dogra, V. S. Pearls and pitfalls in diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Radiographics 28, 1355–1368. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.285075130 (2008).

Needles, A. et al. Development and initial application of a fully integrated photoacoustic micro-ultrasound system. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 60, 888–897. https://doi.org/10.1109/tuffc.2013.2646 (2013).

Dolet, A. et al. In vitro and in vivo multispectral photoacoustic imaging for the evaluation of chromophore concentration. Sens. (Basel) 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21103366 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Ms. Shasha Hong for her assistance in data sorting and verification during the revision stage.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions statement LZ, FM, and XZ contributed equally to this work. GL and QW supervised the study. LZ, FM, XZ, LL, WL, YC, SD, and BZ participated in the design, implementation, and data analysis of the experiments. LZ and FM wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Zhiyuan Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd. (AL07155). This study is performed in accordance with relevant national regulations. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Meng, F., Zu, X. et al. Dual-modal photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging for early diagnosis of ovarian torsion and evaluation of long-term tissue hypoxia. Sci Rep 15, 40675 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17381-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17381-8