Abstract

HIV reservoir latently persists in people with HIV (PWH) despite long-term antiretroviral therapy (ART). Total HIV DNA quantification is commonly employed as a surrogate marker to assess the size of the viral reservoir. We developed a duplex digital PCR assay to easily quantify the total HIV DNA in PWH on the microfluidic automated Absolute Q™ digital PCR platform. We assessed the linearity, specificity, sensitivity, and precision targeting the HIV LTR and the human RPP30 gene. We evaluated the assay in clinical samples from 50 PWH on ART and six ART-naïve PWH. The assay showed good linearity (R² = 0.977, p < 0.0001) and a 95% lower limit of detection of 79.7 HIV DNA copies/10⁶ cells. Repeatability and reproducibility were acceptable for 1,250 copies/10⁶ cells (CV = 8.7% and 10.9%) but higher variability for 150 copies/10⁶ cells (CV = 26.9% and 19.9%). Total HIV reservoir was detected in all PWH samples, with statistically significant differences between ART-treated and ART-naïve PWH (p < 0.0001). Positive strong correlation (rho = 0.868, p < 0.0001) was observed between the HIV reservoir in CD4 + T cells and PBMCs from 15 ART-treated PWH. Our assay expands the range of digital PCR platforms available for accurate HIV reservoir quantification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The HIV latent reservoir is primarily established in CD4 + T cells early after HIV infection and remains integrated into the host genome throughout life, despite antiretroviral therapy (ART)1,2. HIV reservoir rapidly decays in the first year of ART3,4; afterward, the decay slows or stops5. This latent reservoir constitutes the major barrier to an HIV cure6. Therefore, accurately measuring the latent HIV reservoir is crucial for monitoring the effectiveness of therapeutic strategies aimed at achieving HIV remission or cure.

The most widely used biomarker for assessing HIV reservoir is total HIV DNA quantification7. This approach measures both integrated and non-integrated viral genomes, including extrachromosomal 2-LTR circles, 1-LTR circles, and linear forms. Total HIV DNA assay quantifies all forms of HIV DNA but does not differentiate between replication-competent productive viruses and non-replicative defective forms, requiring more complex techniques such as the viral outgrowth assay (QVOA) and the intact proviral DNA assay (IPDA)8,9. The total HIV DNA assay targets conserved regions of the viral genome within the long terminal repeat (LTR)10gag11 or pol12 and is commonly performed in real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) platforms with singleplex assays7. However, qPCR methods exhibit some limitations: they provide an indirect measurement relying on standard curves generated from HIV-infected cell lines (e.g., 8E5, ACH2)13 and show limited sensitivity for detecting low-abundance target molecules14. In persons with HIV (PWH) who maintain long-term viral suppression on ART, the HIV reservoir is estimated to range from fewer than 100 to 3,000 HIV DNA copies per million of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)15,16,17,18. Thus, highly precise and sensitive quantification methods are critical for measuring the total HIV DNA reservoir.

Digital PCR (dPCR) has emerged as a promising quantification method in virology, offering both absolute quantification and high sensitivity14,19,20. It enables detection of low-abundance target molecules, allows effective multiplexing when target genes quantities differ significantly and offers greater tolerance to PCR inhibitors21,22,23. This technology partitions the sample into thousands of independent reaction chambers and directly counts the positive partitions containing the target molecule. Then, a Poisson statistical calculation is applied to provide an absolute value in copies/µl eliminating the need of standard curves24. Sample partitioning can be achieved through several approaches, including microdroplet generation and microchamber arrays25,26.

Droplet-based digital PCR (ddPCR), which partitions the sample into microdroplets, is the most widely adopted dPCR method for quantifying the HIV reservoir, enabling multiplex measurements25. However, microdroplet generation can be labor-intensive and time-consuming and variation in droplet size can affect fluorescence signals27,28,29. In contrast, microchamber array plate-based digital PCR (pdPCR) platforms offer fully automated workflows for sample partitioning into microchambers, PCR amplification and image acquisition, thereby reducing hands-on time, total assay duration and contamination risk, as well as eliminating droplet size and number variability30,31. Given these advantages, along with its multiplexing capacity27pdPCR warrants evaluation for its utility in quantifying total HIV DNA.

In this study, we used the Absolute Q™ digital PCR platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), based on microfluidic chamber array plates, to develop a duplex assay for quantifying total HIV DNA, in accordance with the recommendations of the digital MIQE guidelines32. In this platform, sample partitioning, thermocycling, and imaging are integrated into a single, fully automated instrument. We evaluated the linearity, specificity, sensitivity and reproducibility of the total HIV DNA assay targeting the LTR-RU5 HIV-1 region, and validated its application to clinical samples from PWH, including individuals who have not initiated ART and those currently receiving ART.

Results

Development of the duplex pdPCR assay for total HIV-1 DNA quantification

We first optimized the duplex pdPCR assay by testing different denaturation, annealing and extension conditions, as well as varying the number of cycles (Supplementary Table S1). The 2D plots generated after the PCR assay showed optimal positive FAM (LTR-RU5 HIV-1) and VIC (RPP30) fluorescence separation under the following PCR conditions: 10 s at 96 °C for denaturation, 50 s at 60 °C for annealing and extension, 40 amplification cycles, 900 nM LTR-RU5 HIV and RPP30 primer concentration and 250 nM LTR-RU5 HIV and RPP30 probe concentration (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Shorter annealing and extension times and less amplification cycles increased the intermediate fluorescence signal in the 2D plots complicating thresholding (Supplementary Fig. S1b).

Assay performance is shown in Fig. 1, observing a reduction in the number of positive partitions proportional to the applied sample dilution, with no positive signals detected in the no-template control (NTC). Specificity was confirmed using genomic DNA from HIV-negative donors, where no positive signal was obtained for HIV-1 target. Additionally, no bleed-through was observed between fluorescence channels, demonstrating clear discrimination of signals (Supplementary Fig S2). Singleplex assays quantifying either LTR-RU5 HIV or RPP30 in 8E5 cells produced results consistent with those from the duplex assay (Supplementary Table S2).

Representative pdPCR 2D plots showing assay performance. 8E5 cells were subjected to serial dilutions ranging from 180 to 11.25 ng. The input DNA (ng) and the observed HIV and RPP30 copies are indicated in the tables. Blue points indicate positive partitions for LTR-RU5 HIV (FAM channel) and green points represent positive partitions for RPP30 gene (VIC channel). Thresholds were established to distinguish between positive and negative partitions. Samples from HIV-negative donors served as negative controls for HIV target amplification. NTC: no-template control.

Assay linearity

To evaluate linearity, sensitivity and precision of the assay we used a batch of 8E5 cells containing 0.8 HIV copies/cell, value calculated with the Absolute Q™ digital PCR instrument. Significant linear correlation was observed between the expected and the measured concentration in total HIV-1 copies/10⁶ cells (R² = 0.977, p < 0.0001), confirming the linearity of the multiplex pdPCR assay across the tested range of 5,000 to 78 HIV DNA copies/106 cells (Fig. 2a). We also determined the linearity of HIV-1 and RPP30 target quantification in singleplex assays relative to input DNA concentration. Both HIV-1 and RPP30 targets showed good linearity across the tested range of 270 ng to 16.8 ng (R² = 0.999, p < 0.0001 and R² = 0.998, p < 0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 2b).

Linear dynamic range of the total HIV DNA assay. (a) Measured concentration plotted against the expected total HIV copies/10⁶ cells in serial dilutions of 8E5 cell DNA spiked into PBMCs DNA from an HIV-negative donor. (b) Total HIV copies and total RPP30 copies plotted against the input DNA concentration of the singleplex assays. Data was fitted to a simple linear regression model.

Limits of detection and quantification

The estimated lower limit of detection with 95% confidence (LLOD 95%) was 79.7 HIV DNA copies/10⁶ cells (log 1.9 copies/10⁶ cells) with a 95% confidence interval of 47.72 to 323.3 HIV copies/10⁶ cells (Fig. 3). The limit of quantification (LOQ) of the assay, defined as the concentration of HIV copies detected with 100% accuracy, was determined to be 5 HIV copies/reaction.

LLOD 95% of the total HIV DNA assay. Probability of detecting HIV (%) in 2-fold serial dilutions of 8E5 cell DNA spiked into PBMCs DNA from an HIV-negative donor, ranging from 5000 to 9.8 HIV copies/10⁶ cells, as analyzed by probit regression. The red dotted line represents the 95% probability of detection which corresponds to the LLOD95%. The blue area shows the 95% Confidence Interval.

Assay repeatability and reproducibility

Precision was assessed at two HIV DNA levels (1,250 and 150 HIV copies/10⁶ cells). For repeatability (intra-assay variability), the coefficient of variation (CV%) was 8.7% for 1,250 HIV copies/10⁶ cells and 26.9% for 150 HIV copies/10⁶ cells. For reproducibility (inter-assay variability), the CV% was 10.9% for 1,250 HIV copies/10⁶ cells and 19.9% for 150 HIV copies/10⁶ cells.

We also evaluated the precision of the assay across different input DNA concentrations using 8E5 cells (ranging from 270 ng to 16.9 ng) and PBMCs from an ART-treated HIV-infected participant (ranging from 330 ng to 165 ng) (Table 1). We found that HIV-DNA quantification was highly consistent regardless of input DNA amount, with a CV% of 2.7% for 8E5 cells (mean 0.8 × 106 HIV copies/10⁶ cells) and 11.5% for PBMCs (mean 1,160 HIV copies/10⁶ cells).

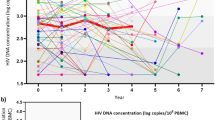

Evaluation of total HIV DNA quantification in clinical samples

Following optimization of the pdPCR assay, we quantified the total HIV DNA in 50 PWH on stable ART (< 50 HIV-RNA copies/mL), 6 ART-naïve PWH with detectable viremia (> 50 HIV-RNA copies/mL) and 4 HIV-negative donors. In ART-treated PWH, total HIV DNA was quantified in CD4 + T cells, obtaining values ranging from 21.5 to 5,694 HIV copies/10⁶ CD4 + T cells (median 995.3 HIV copies/10⁶ CD4 + T cells; IQR 646.9-1,572). No positive partitions were detected in HIV-negative control samples, confirming the assay´s specificity. In ART-naïve PWH, total HIV DNA ranged from 4,612 to 36,919 HIV copies/10⁶ PBMCs (median 16,565 HIV copies/10⁶ PBMCs; IQR 6,560 − 35,465), levels significantly higher than those observed in samples from PWH on ART (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4a). No CD4 + T cell samples were available for ART-naïve PWH.

Total HIV DNA quantification in clinical samples using pdPCR. (a) Box-and-whiskers plots of total HIV DNA in PBMCs from ART-naïve PWH with detectable viral load (VL) (n = 6), and in PBMCs (n = 15) and CD4 + T cells (n = 50) from ART-treated PWH with undetectable VL. Dotted line indicates de LLOD95%. Box plots show the median and the interquartile range (25% percentile and 75% percentile). Lower and upper whisker limits correspond to the minimum and maximum data values. Data was compared with Wilcoxon’s rank sum test. (b) Comparison of total HIV DNA in PBMCs and CD4 + T cells from the same ART-treated participants with undetectable VL (n = 15) using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. (c) Spearman correlation between PBMCs and CD4 + T cells from the same ART-treated participants with undetectable VL (n = 15).

Total HIV reservoir was also measured in PBMCs from 15 participants of the ART-treated PWH group, obtaining values from 98.6 to 1,925 HIV copies/10⁶ PBMCs (median 506.1 HIV copies/10⁶ PBMCs; IQR 312.2-766.7) (Fig. 4a). The values obtained in PBMCs were significantly lower than those in CD4 + T cells (p = 0.0001) (Fig. 4b). Moreover, the reservoir in PBMCs and CD4 + T cells showed a strong positive correlation (rho = 0.868, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

The droplet dPCR-based total HIV DNA assay12,18,33,34,35 was adapted and optimized for use on the microchamber array plate-based Absolute Q™ digital PCR instrument, showing that this platform enables sensitive and accurate quantification of the total HIV DNA. Our study evaluated key parameters of the multiplex pdPCR assay, including linearity, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and reproducibility, in controlled experiments.

This assay was designed to achieve ultrasensitive quantification of total HIV DNA in the context of PWH on ART. Therefore, the optimization experiments were performed using a dynamic range that encompasses the typical levels of total HIV reservoir observed in this population15,16,17,18. The analytical sensitivity, evaluated by the LLOD at 95%, fell within the range reported in previous ddPCR and microchamber dPCR assays, where the LLOD 95% values ranged from 30 to 150 HIV copies/10⁶ cells18,36,37. Sensitivity can be improved by analyzing larger DNA pools processing additional replicates35. The limit of quantification, defined as the lowest concentration detected with 100% accuracy, was 5 HIV copies per reaction well, though this pdPCR can detect as low as 1 copy per reaction well. Assay variability was higher for low HIV reservoirs, since small differences in the number of positive partitions on the pdPCR chip result in significant variation when calculating the number of HIV copies/10⁶ cells. Similarly, recent duplex dPCR studies have reported CV% values of approximately 21–22% for samples containing 100 HIV copies/106 cells18,36demonstrating comparable repeatability. Despite the high CV% for low reservoir levels, the high sensitivity of digital PCR allows the analysis of clinical samples with low viral reservoirs that might not be detectable with other qPCR-based methods14,21,34,38.

This pdPCR assay is suitable for quantifying total HIV DNA in samples with limited availability, as results obtained with low input DNA are consistent with those observed from higher input DNA. Optimization of input DNA is required as low DNA concentrations reduce the probability of detecting low-level molecules, while high DNA concentrations can saturate the microchambers, limiting accurate quantification of the endogenous gene by Poisson statistics39. Multiplexing this assay to detect both HIV and a host genome gene in a single well reduces the amount of DNA required and minimizes variability from sample dilution and technical errors.

Absolute quantification with digital PCR platforms avoids the need for a standard curve, reducing variability between laboratories40. Classical qPCR assays commonly use the 8E5 cell line for the relative quantification of the HIV reservoir. However, this cell line has been observed to lose HIV copies during in vitro culture13,36as shown in our results. This fact may potentially impact HIV reservoir measurements by qPCR assays in long-term patient follow-ups13,36.

Total HIV DNA was detected in all 56 clinical samples analyzed, with the lowest value at 21.5 HIV copies/10⁶ cells. This supports the sensitivity of this pdPCR assay to quantify the HIV reservoir in individuals receiving long-term antiretroviral therapy. The levels of total HIV DNA in CD4 + T cells and PBMCs from virally suppressed PWH on ART were comparable to those previously reported with other digital PCR platforms, which found median values ranging from 400 to 1,000 HIV copies/10⁶ CD4 + T cells18,41,42,43 and 100 to 400 HIV copies/10⁶ PBMCs18,35,36,41. In this study, total HIV DNA in PBMCs and CD4 + T cells from ART-treated PWH was strongly correlated. Thus, using CD4 + T cells instead of PBMCs increases the probability of detection and improves assay precision by enriching cells that are more likely to harbor HIV reservoirs. Consistent with previous studies, the mean reservoir size was significantly larger in ART-naïve participants compared to those on ART35,44,45.

The Absolute Q™ digital PCR platform can detect up to four different targets within a single sample well, making it a highly suitable tool for analyzing additional regions of HIV. This approach offers deeper insights into the size, replicative capacity and evolution of the HIV reservoir46,47,48. Furthermore, as pdPCR platforms become increasingly widespread, available guidelines, such as the dMIQE guidelines, play a key role in supporting the optimization of standardized protocols, thereby promoting reproducibility across studies32.

Limitations of this study include the lack of comparative analysis against other real-time quantitative PCR or digital droplet PCR platforms; it was conducted exclusively on the Absolute Q™ digital platform using standardized control cell lines. This platform allows for the processing of only 16 samples per run, significantly increasing the analysis time for multiple replicates. While this assay quantifies total HIV DNA, it does not provide information about replication-competent viruses, as IPDA and QVOA assays do. However, several studies have reported that total HIV DNA levels strongly correlate with the frequency of cells harboring replication-competent viruses, making total HIV DNA quantification an informative and feasible approach for estimating the HIV reservoir49,50. We used a set of primers and probe targeting the LTR-RU5 region, a highly conserved HIV region, however mutations in this region would compromise the assay’s efficacy for HIV detection. Finally, although the pdPCR platform reduces laboratory requirements and minimizes manual processing compared to droplet-based methods, its cost and technical demands may still limit its applicability in low-resource settings.

In conclusion, the ability to quantify total HIV DNA using this platform expands the range of tools available for measuring the HIV reservoir in clinical samples. This could enable more laboratories to adopt digital platforms for HIV reservoir quantification as an alternative to quantitative PCR. Digital PCR platforms based on microfluidic chamber array plates feature an automated process on a single device that reduces hands-on time, facilitating easier implementation in laboratories. The assay requires a relatively small sample volume, making it particularly suitable for studies where sample availability is limited. Additionally, its low limit of detection makes this assay particularly valuable for evaluating curative strategies aimed at HIV eradication. Finally, this assay could be adapted to measure the reservoir in other tissue types beyond blood, providing a more comprehensive understanding of reservoir size and its evolution in long-term treated individuals.

Methods

Cell line samples and participants

The 8E5 cell line, containing one integrated HIV copy per cell genome, was used to develop the pdPCR assay for quantifying total HIV DNA. The 8E5 cells were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program (catalogue number ARP-95), contributed by Dr. Thomas Folks. For this study, we used a sub-culture that had undergone only a single passage prior to experiments.

For assay validation in clinical samples, we used PBMCs and/or CD4 + T cells from 50 virologically suppressed PWH on ART and 6 ART-naïve PWH with detectable viremia, randomly selected from a registered sample collection (registration number: C.0005530) at National Biobank Registry, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid, Spain). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of La Paz University Hospital, and we obtained written informed consent for all participants. Inclusion criteria for ART-treated PWH were: HIV antibody positive, a stable ART regimen (no change in ART for at least 3 months) and a serum HIV-RNA load (VL) of < 50 copies/mL for at least 1 year prior to sample collection. Inclusion criteria for ART-naïve PWH were: HIV antibody positive, no ART initiation, and serum HIV-RNA levels > 50 copies/mL. Participant characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table S3. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and other relevant guidelines.

PBMCs and CD4 + T cells isolation and DNA extraction

PBMCs were isolated from whole fresh peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation using SepMate™ tubes (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) and stored in aliquots of 5 × 106 cell pellets at −80 °C. CD4 + T cells were isolated from PBMCs by negative selection using immunomagnetic cell separation (CD4 + T Cell Isolation Kit; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and stored in aliquots of 5 × 106 cell pellets at −80 °C. Genomic DNA was isolated from 8E5 cells, PBMCs and CD4 + T cells pellets using the QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol and stored at −20 °C. The purity and integrity of the extracted DNA were assessed by spectrophotometry using a Nanodrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer and by gel electrophoresis.

Probes and primers

For measuring total HIV DNA, we used a previously described51 prime/probe set targeting HIV-1 LTR-RU5 region: forward primer (5′-TTAAGCCTCAATAAAGCTTGCC-3′), reverse primer (5′-GTTCGGGCGCCACTGCTAGA-3′) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) and probe (5′−6-FAM-CCAGAGTCACACAACAGACGGGCACA-MGB-3′) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). We used a second, previously published primer/probe set targeting RPP30 gene12 for host genomic DNA quantification: forward primer (5’-GATTTGGACCTGCGAGCG-3’), reverse primer (5’-GCGGCTGTCTCCACAAGT-3’) and probe (5’–VIC-CTGACCTGAAGGCTCT-MGB-3’). The specificity of primers and probes was confirmed in silico using the NCBI BLAST tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Detailed information on the primer/probe sets is provided in Supplementary Table S4.

Total HIV DNA assay in microchamber array plate-based dPCR (pdPCR)

Total HIV DNA assay was developed on the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio Absolute Q™ Digital PCR system (ThermoFisher scientific). The reaction mixture contained 900 nM of forward and reverse HIV LTR-RU5 and RPP30 primers, 250 nM of HIV LTR-RU5 and RPP30 probes, 1X Applied Biosystems™ Absolute Q™ DNA Digital PCR Master Mix and template DNA in a final volume of 10 µl. Up to 340 ng of genomic DNA was added per well to ensure accurate quantification of both HIV-DNA and RPP30 gene. In each well of the microfluidic 16-well array plate (MAP16), 9 µl of the reaction mixture were loaded, followed by the addition of 15 µl of QuantStudio™ Absolute Q™ Isolation Buffer on top without mixing. All PCR runs included both a no-template control (NTC) and a negative control using genomic DNA from HIV-negative donors. MAP16 plates were transferred to the dPCR platform for sample partitioning, PCR amplification and image acquisition. The optimal PCR conditions were: 96 °C for 10 min for initial enzyme activation, followed by 40 cycles of 96 °C for 10 s for denaturation and 60 °C for 50 s for annealing and extension.

Each well of the MAP16 plate contains a chip with 20,480 microchambers. During the PCR assay, each sample is partitioned into the 20,480 microchambers of the chip, each containing either one or zero copies of the target molecule. Each microchamber allows an individual PCR reaction, producing a positive fluorescence signal if the target molecule is present. The positive and negative fluorescent signals of the microchamber chip are then transformed into two-dimensional (2D) plots. After fluorescence thresholding, the fraction of positive microchambers is fitted to a Poisson distribution to determine the absolute target copy number (copies/µL) in the input reaction mix (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Data analysis

QuantStudio Absolute Q™ Digital PCR Software (Version 6.3.2) was used to analyze the pdPCR results. For sample analysis, the microchamber chip quality must meet the following criteria: no reading issues, uniform reagent distribution into the microchambers, and a minimum of 19,000 fully occupied microchambers with reaction mixture out of the 20,480 total microchambers. Reaction mixture contains a passive reference ROX dye to evaluate the reagent distribution automatically. 2D plots were analyzed setting threshold levels manually based on HIV positive, HIV negative and no-template DNA control samples. RPP30 copy number was used to normalize the cell input. After thresholding and Poisson statistical analysis, the absolute target copy number (copies/µL) is obtained for each gene. To obtain the number of Total HIV copies/10⁶ cells, we applied the following: \(\:Total\:HIV\:copies/10^6\:cells=\frac{HIV\:copies/\mu\:L}{\left(\right(RPP30\:copies/\mu\:L)/(2\:copies/cell\left)\right)}\:x10^6\:\).

Assay linearity

To assess the linear dynamic range of the duplex pdPCR assay, DNA from 8E5 cells was subjected to 2-fold serial dilutions into a constant amount of PBMCs DNA from an HIV-negative donor. This approach maintained a constant number of cells input across all dilutions while varying the number of HIV copies (from 5,000 to 78 HIV DNA copies/106 cells). Assays were conducted across five independent runs with duplicates. To evaluate the linearity of the singleplex assays for the HIV target and RPP30, 8E5 cell DNA was subjected to 2-fold serial dilutions into H2O, ranging from 270 ng to 16.8 ng.

Limits of detection and quantification

The analytical sensitivity was evaluated by determining the 95% lower limit of detection (LLOD95%), through 2-fold serial dilutions of 8E5 cell DNA into a constant amount of PBMCs DNA from an HIV-negative donor, yielding concentrations ranging from 5,000 to 9.8 HIV copies/10⁶ cells, equivalent to 220 to 0.5 HIV copies per reaction. Each concentration was tested in up to 10 replicates.

Assay repeatability and reproducibility

For the precision assessment, 8E5 cell DNA was spiked into PBMCs DNA from an HIV-negative donor to obtain final concentrations of 1,250 and 150 HIV copies/106 cells. To evaluate the repeatability (intra-assay variability), samples at both concentrations were tested 6 times within a single run, and the coefficient of variation (CV%) was calculated. To assess reproducibility (inter-assay variability), samples were analyzed in 5 independent runs in duplicate, and the CV% was determined.

Assay precision across different input DNA concentrations was assessed using 8E5 cells DNA (ranging from 270 ng to 16.9 ng) and PBMCs DNA from an HIV-infected participant (ranging from 330 ng to 165 ng), with each condition tested in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Simple linear regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the assay linear dynamic range. The lower limit of detection 95% (LLOD95%) was calculated using probit regression analysis in MedCalc Software 23.0.2 (MedCalc, Ostend, Belgium). Reproducibility and repeatability analysis are presented by the coefficient of variation (CV%). Wilcoxon’s rank sum test was used to compare results between ART-treated and ART-naïve PWH. Spearman correlation and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was used to assess the correlation and differences of total HIV DNA between PBMCs and CD4 + T cells of the same participants. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism version 10.4 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chun, T. W. et al. Early establishment of a pool of latently infected, resting CD4 + T cells during primary HIV-1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 95, 8869–8873 (1998).

Siliciano, J. D. et al. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4 + T cells. Nat. Med. 9, 727–728 (2003).

Perelson, A. S. et al. Decay characteristics of HIV-1-infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature 387, 188–191 (1997).

Kulpa, D. A. & Chomont, N. HIV persistence in the setting of antiretroviral therapy: when, where and how does HIV hide? J. Virus Erad. 1, 59–66 (2015).

Gandhi, R. T. et al. Selective decay of intact HIV-1 proviral DNA on antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 223, 225–233 (2021).

McMyn, N. F. et al. The latent reservoir of inducible, infectious HIV-1 does not decrease despite decades of antiretroviral therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 133, e171554. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI171554 (2023).

Rouzioux, C., Avettand-Fenoël, V. & Total HIV DNA: a global marker of HIV persistence. Retrovirology 15, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12977-018-0412-7 (2018).

Belmonti, S., Di Giambenedetto, S. & Lombardi, F. Quantification of total HIV DNA as a marker to measure viral reservoir: methods and potential implications for clinical practice. Diagnostics (Basel). 12, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12010039 (2021).

Abdel-Mohsen, M. et al. Recommendations for measuring HIV reservoir size in cure-directed clinical trials. Nat. Med. 26, 1339–1350 (2020).

Avettand-Fènoël, V. et al. LTR real-time PCR for HIV-1 DNA quantitation in blood cells for early diagnosis in infants born to seropositive mothers treated in HAART area (ANRS CO 01). J. Med. Virol. 81, 217–223 (2009).

Klatt, N. R. et al. Limited HIV infection of central memory and stem cell memory CD4 + T cells is associated with lack of progression in viremic individuals. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004345. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004345 (2014).

Strain, M. C. et al. Highly precise measurement of HIV DNA by droplet digital PCR. PLoS One. 8, e55943. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055943 (2013).

Busby, E. et al. Instability of 8E5 calibration standard revealed by digital PCR risks inaccurate quantification of HIV DNA in clinical samples by qPCR. Sci. Rep. 7, 1209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01221-5 (2017).

Gleerup, D., Trypsteen, W., Fraley, S. I. & De Spiegelaere, W. Digital PCR in virology: current applications and future perspectives. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 29, 43–54 (2025).

Hocqueloux, L. et al. Long-term antiretroviral therapy initiated during primary HIV-1 infection is key to achieving both low HIV reservoirs and normal T cell counts. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 1169–1178 (2013).

von Wyl, V. et al. Early antiretroviral therapy during primary HIV-1 infection results in a transient reduction of the viral setpoint upon treatment interruption. PLoS One. 6, e27463. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027463 (2011).

Piketty, C. et al. A high HIV DNA level in PBMCs at antiretroviral treatment interruption predicts a shorter time to treatment resumption, independently of the CD4 nadir. J. Med. Virol. 82, 1819–1828 (2010).

Yuan, L. et al. Development of a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction assay for the sensitive detection of total and integrated HIV-1 DNA. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 137, 729–736 (2024).

Sancha Dominguez, L., Suárez, C., Sánchez Ledesma, A., Muñoz Bellido, J. L. & M. & Present and future applications of digital PCR in infectious diseases diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 14, 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14090931 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Global trends in the application of droplet digital PCR technology in the field of infectious disease pathogen diagnosis: A bibliometric analysis from 2012 to 2023. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 111, 116623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2024.116623 (2024).

Taylor, S. C., Laperriere, G. & Germain, H. Droplet digital PCR versus qPCR for gene expression analysis with low abundant targets: from variable nonsense to publication quality data. Sci. Rep. 7, 2409. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02217-x (2017).

Bernardi, S. et al. Digital PCR (dPCR) is able to anticipate the achievement of stable deep molecular response in adult chronic myeloid leukemia patients: results of the DEMONSTRATE study. Ann. Hematol. 104, 207–217 (2024).

Kaur, C., Adams, S., Kibirige, C. N. & Asquith, B. Absolute quantification of rare gene targets in limited samples using crude lysate and DdPCR. Sci. Rep. 15, 9744. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94115-w (2025).

Sedlak, R. H. & Jerome, K. R. Viral diagnostics in the era of digital polymerase chain reaction. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 75, 1–4 (2013).

Kojabad, A. A. et al. Droplet digital PCR of viral DNA/RNA, current progress, challenges, and future perspectives. J. Med. Virol. 93, 4182–4197 (2021).

Mao, X., Liu, C., Tong, H., Chen, Y. & Liu, K. Principles of digital PCR and its applications in current obstetrical and gynecological diseases. Am. J. Transl Res. 11, 7209–7222 (2019).

Mirabile, A. et al. Advancing pathogen identification: the role of digital PCR in enhancing diagnostic power in different settings. Diagnostics (Basel). 14, 1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14151598 (2024).

Dobnik, D. et al. Inter-laboratory analysis of selected genetically modified plant reference materials with digital PCR. Anal. Bioanal Chem. 410, 211–221 (2018).

Kokkoris, V., Vukicevich, E., Richards, A., Thomsen, C. & Hart, M. M. Challenges using droplet digital PCR for environmental samples. Appl. Microbiol. 1, 74–88 (2021).

Sánchez-Martín, V. et al. Comparative study of droplet-digital PCR and absolute Q digital PCR for ctdna detection in early-stage breast cancer patients. Clin. Chim. Acta. 552, 117673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2023.117673 (2024).

Ren, J. et al. A Chamber-Based digital PCR based on a microfluidic chip for the absolute quantification and analysis of KRAS mutation. Biosens. (Basel). 13, 778. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios13080778 (2023).

dMIQE Group, Huggett, J. F. & The Digital, M. I. Q. E. Guidelines update: minimum information for publication of quantitative digital PCR experiments for 2020. Clin. Chem. 66, 1012–1029 (2020).

Chung, H. K. et al. Development of droplet digital PCR-Based assays to quantify HIV proviral and integrated DNA in brain tissues from viremic individuals with encephalitis and virally suppressed aviremic individuals. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0085321 (2022). 10.1128/spectrum.00853 – 21.

Powell, L. et al. Clinical validation of a quantitative HIV-1 DNA droplet digital PCR assay: applications for detecting occult HIV-1 infection and monitoring cell-associated HIV-1 dynamics across different subtypes in HIV-1 prevention and cure trials. J. Clin. Virol. 139, 104822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104822 (2021).

Reed, J. et al. Validation of digital droplet PCR assays for cell-associated HIV-1 DNA, HIV-1 2-LTR circle, and HIV-1 unspliced RNA for clinical studies in HIV-1 cure research. J. Clin. Virol. 170, 105632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2023.105632 (2024).

Renault, C. et al. Accuracy of real-time PCR and digital PCR for the monitoring of total HIV DNA under prolonged antiretroviral therapy. Sci. Rep. 12, 9323. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13581-8 (2022).

Vicenti, I. et al. External quality assessment of HIV-1 DNA quantification assays used in the clinical setting in Italy. Sci. Rep. 12 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07196-2 (2022).

Bosman, K. J. et al. Comparison of digital PCR platforms and semi-nested qPCR as a tool to determine the size of the HIV reservoir. Sci. Rep. 5, 13811. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13811 (2015).

Quan, P. L., Sauzade, M. & Brouzes, E. dPCR: A technology review. Sens. (Basel). 18, 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18041271 (2018).

Whale, A. S. et al. International interlaboratory digital PCR study demonstrating high reproducibility for the measurement of a rare sequence variant. Anal. Chem. 89, 1724–1733 (2017).

Gálvez, C. et al. Atlas of the HIV-1 reservoir in peripheral CD4 T cells of individuals on successful antiretroviral therapy. mBio 12, e0307821. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.03078-21 (2021).

Saborido-Alconchel, A. et al. Long-term effects on immunological, inflammatory markers, and HIV-1 reservoir after switching to a two-drug versus maintaining a three-drug regimen based on integrase inhibitors. Fron Immunol. 15, 1423734. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1423734 (2024).

Bachmann, N. et al. Determinants of HIV-1 reservoir size and long-term dynamics during suppressive ART. Nat. Commun. 10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10884-9 (2019).

Chéret, A. et al. Impact of early cART on HIV blood and semen compartments at the time of primary infection. PLoS One. 12, e0180191. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180191 (2017).

Chéret, A. et al. Combined ART started during acute HIV infection protects central memory CD4 + T cells and can induce remission. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 2108–2120 (2015).

Delporte, M. et al. Integrative assessment of total and intact HIV-1 reservoir by a 5-Region multiplexed rainbow DNA digital PCR assay. Clin. Chem. 71, 203–214 (2025).

Van Snippenberg, W. et al. Triplex digital PCR assays for the quantification of intact proviral HIV-1 DNA. Methods 201, 41–48 (2022).

Levy, C. N. et al. A highly multiplexed droplet digital PCR assay to measure the intact HIV-1 proviral reservoir. Cell. Rep. Med. 2, 100243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100243 (2021).

Eriksson, S. et al. Comparative analysis of measures of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 eradication studies. Plos Pathog. 9, e1003174. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003174 (2013).

Kiselinova, M. et al. Integrated and total HIV-1 DNA predict ex vivo viral outgrowth. Plos Pathog. 12, e1005472. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1005472 (2016).

Liszewski, M. K., Yu, J. J. & O’Doherty, U. Detecting HIV-1 integration by repetitive-sampling Alu-gag PCR. Methods 47, 254–260 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Merck Sharp and Dohme (grant number MISP: IISP 101566), Instituto de Salud Carlos III-European Regional Development Fund (grant number PI24/00927) and Fundación para la Investigación Biomédica Hospital Universitario La Paz (grant number LA-2023.064). L.G.G. was supported by a predoctoral training in health research fellowship from Instituto de Salud Carlos III-European Regional Development Fund (FI23/00061).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.G.G, A.E.C, J.R.C and B.R conceived the study and designed the experiments. L.G.G conducted the experiments. L.G.G, A.E.C and B.R reviewed and interpreted the results. C.M and JR.A acquired and managed the clinical data. JR.A and B.R acquired the funding. L.G.G wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gutiérrez-García, L., Esteban-Cantos, A., Rodríguez-Centeno, J. et al. Duplex digital PCR assay on microfluidic chamber arrays for total HIV DNA reservoir quantification in persons with HIV. Sci Rep 15, 31658 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17392-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17392-5