Abstract

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient, which plays an important role in plant growth and development process and increases crop production. However, excessive nitrogen application will lead to a series of problems such as water eutrophication and economic costs. Therefore, it is of great significance to explore rice low-nitrogen tolerance genes and breed new varieties with higher nitrogen utilization efficiency for improving the economic benefits and agricultural sustainability of agricultural production. In this study, 295 japonica rice varieties were used as materials to measure root dry weight, leaf dry weight and root-shoot ratio at seedling stage under low and high nitrogen conditions. By using Genome-wide association analysis and haplotype analysis of 587 genes among the 47 QTLs obtained, we finally identified significant phenotypic differences between the different haplotypes of the 96 genes. Based on the criteria of |log2FC| > 1 and p < 0.05, 5 genes (Os06g0538400, Os11g0195500, Os11g0213700, Os11g0213800, Os12g0472800) were significantly different in the expression of Longjing 31 (low-nitrogen tolerant variety), but not in Songjing 10 (low-nitrogen sensitive variety), and they were named the more valuable candidate genes for low-nitrogen tolerance. Os11g0213700 and Os11g0213800, as genes containing LRR structure, may regulate root development and low nitrogen stress response by interacting with KAI2. Mining low-nitrogen tolerance genes in rice is of great significance to rice growth and agricultural development. The results of this study provide an important molecular basis for identifying low-nitrogen tolerance genes and breeding low-nitrogen tolerant rice varieties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.), serving as the main carbohydrate source for a majority of the earth’s population, stands as a cornerstone of food security and a vital link in chain of socioeconomic development and ecological balance, embodying its global significance across multiple dimensions of human survival, agricultural sustainability, and cultural diversity1,2. Nitrogen (N) is the most important factor affecting plant growth. Because of the great demand for N in rice growth and development, N is often used to increase rice yield in the process of planting rice3. However, the relationship between rice yield and N application rate is not always proportional, and excessive or absent N fertilizer limits the increase of rice yield. Excessive N fertilizer will also reduce rice quality4, increase field lodging5, and even lead to poor environment6. Consequently, developing rice varieties with enhanced low-N tolerance has become a key breeding priority.

Dry matter distribution, a core processes of plant growth and development, directly affects growth efficiency and yield formation by regulating the allocation of photosynthetic products among roots, stems and leaves7. Root dry weight (RW), leaf dry weight (LW) and root-shoot ratio (RSR) are key indicators reflecting plant resource allocation strategies8. RSR, defined as the ratio of RW to LW, represents the balance of resource distribution between belowground and aboveground plant parts9. Studies have shown that a higher RSR is positively correlated with low-N tolerance, as increased resource allocation to roots enhances N uptake capacity10. Therefore, investigating the relationship between dry matter partitioning and low-N tolerance is of great significance for elucidating the mechanisms underlying rice adaptation to low-N environments and for breeding N-efficient rice varieties.

If it is expected to increase the yield by applying reasonable N fertilizer, we should mainly improve the tolerance of crops to N11. Low-N tolerant rice varieties can still maintain high yield under N reduction conditions12. In addition, people have conducted extensive research on low-N tolerance related indicators, and successfully identified a series of low-N tolerance genes in recent years. Zhang et al.13 found that overexpression of TOND1 can improve tolerance to low-N stress and yield of rice. Liu et al.14 successfully identified OsTCP19 as a negative regulatory gene for the response of tiller number to N in rice. The expression of OsAMT1.2 was also found to be enhanced under low N condition15. In addition, GRF416, OsDof2517 and NRT1.1B18 were also identified as low-N tolerance genes. The study of these genes not only screened the genotypes of low-N tolerant rice varieties, but also helped to understand the response mechanism of rice to N fertilizer, thereby contributing to sustainable agricultural development19.

In recent years, with the development of molecular biology and genomics technology, Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS), RNA-seq and QTL mapping20,21 etc. are widely used in the process of gene identification. At present, GWAS has successfully identified genes related to rice disease resistance22, photoperiod sensitivity23, rice quality24 and yield-related traits25. Studies on the tolerance of rice to abiotic stresses (such as low N, drought) have been extensively conducted26,27. Yu et al. successfully identify OsNLP4 as a N efficient gene in rice by GWAS28. RNA-seq is often used to study the response mechanism of plant abiotic stress29 and the regulation mechanism of plant metabolic pathways (such as photosynthesis)30. With the strategy of combining GWAS and RNA-seq, Li et al. successfully identified heat-resistant candidate genes in rice29. With the strategy of combining QTL mapping and RNA-seq, Yuan et al. successfully revealed OsSTL1 and OsSTL2 as two causal salt tolerance genes31. These studies provide a solid theoretical foundation and genetic resources for molecular improvement of low-N tolerance and yield improvement of rice. However, low-N tolerance is an extremely complex physiological process, and the study of its molecular mechanism still needs to be further explored. These gene discoveries provide a solid theoretical foundation for understanding the mechanisms of low-N tolerance in rice and offer robust theoretical support for yield improvement. Although significant progress has been made in identifying low-N tolerance genes, most studies have primarily focused on mature stages19. In contrast, japonica rice at the seedling stage remains relatively understudied. The seedling stage is particularly critical for root architecture establishment, as early root system development under low-N stress directly determines nutrient acquisition capacity and profoundly impacts subsequent yield potential32. This study aims to integrate RNA-seq and GWAS approaches to identify SNP significantly associated with low-N stress responses and screen candidate genes for N tolerance. The findings are expected to establish a crucial molecular foundation for breeding low-N tolerant rice varieties and provide molecular targets for improving N use efficiency.

Results

Phenotypic data analysis

To assess phenotypic changes under low and high N conditions, LW, RW and RSR at seedling stage of 295 rice varieties were measured (Table S2). Data indices such as mean and coefficient of variation of LW, RW and RSR are shown in Table S2. Under low and high N conditions, the coefficients of variation ranged from 17.41 to 25.77% and 20.2–28.14% respectively. The coefficients of variation of LW, RW and RSR under high N condition were higher than those under low N condition. Among the relative traits, the coefficient of variation of RWR was the highest and that of LWR was the lowest. The highest coefficient of variation for relative RWR was observed under both N conditions. Each trait exhibited had abundant genetic variation and approximate normal distribution (Figs. 1, S1). Since the low-N tolerance is a quantitative trait, the Pearson correlation analysis was performed on these phenotypic traits. The results showed there were extremely significant positive correlations between RW and LW, and between RW and RSR under high, low and relative N conditions (Fig. 2). The correlation coefficients were 0.644 and 0.649 under low N condition, 0.707 and 0.502 under high N condition, and 0.556 and 0.649 under relative condition (Table S3).

Distribution of phenotypic data of 295 rice varieties under high and low N conditions. (A) HLW: Leaf dry weight under high N condition. LLW: Leaf dry weight under low N condition, (B) HRW: Root dry weight under high N condition. LRW: Root dry weight under low N condition, (C) HRSR: Root-shoot ratio under high N condition. LRSR: Root-shoot ratio under low N condition, (D) LWR: Relative value of leaf dry weight under low and high N conditions, (E) RWR: Relative value of root dry weight under low and high N conditions, (F) RSRR: Relative value of root-shoot ratio under low and high N conditions. Lowercase letters represented the significance between low and high N conditions at the 0.05 level. The significant difference analysis was performed using the One-way ANOVA.

Pearson correlation analysis of nine N tolerance-related traits (HLW, LLW, LWR, HRW, LRW, RWR, HRSR, LRSR, RSRR). The upper part of the figure is a significant test label by One-way ANOVA test. *, the difference significance at the 0.05 level. **, the difference significance at the 0.01 level. The lower part is the correlation coefficient between each trait.

QTLs identification

Based on previous studies33, all 295 rice varieties (Table S4) studied showed no significant population stratification. This population could be divided into three subpopulations with low genetic relatedness among individuals, minimizing potential confounding effects in subsequent GWAS analysis. Forty-seven significant leading SNPs were identified by GWAS (Fig. 3, Table S5). A total of 587 genes were identified within these 47 QTL intervals, of which 572 genes were associated with one trait and 15 genes were associated with two traits (Table S6). These significant leading SNPs were important for seedling response to N (LW, RW and RSR). The number of QTLs and leading SNPs associated with LLW, HLW, LWR, LRW, HRW, RWR, LRSR, HRSR and RSRR were 9, 4, 1, 7, 2, 8, 9, 1 and 6, respectively. They were distributed on all 12 linkage groups of rice and could explain phenotypic variation from 7.94 to 12.37%, respectively. These QTLs and significant leading SNPs are likely to have potential application value in further exploration of rice varieties with low-N tolerance in the future.

Manhattan plots of LW, RW and RSR. (A) Manhattan plots of LW under high- N conditions. (B) Manhattan plots of LW under low-N condition. (C) Manhattan plots of relative LW under low and high-N conditions. (D) Manhattan plots of RW under high-N condition. (E) Manhattan plots of RW under low-N condition. (F) Manhattan plots of relative RW under low and high-N conditions. (G) Manhattan plots of RSR under high-N condition. (H) Manhattan plots of RSR under low-N condition. (I) Manhattan plots of relative RSR under low and high-N conditions.

Candidate gene mining

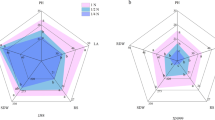

Among these 587 genes, a total of 160 genes exhibited distinct haplotype variations, with 133, 24 and 3 genes having 2, 3 and 4 haplotypes, respectively (Table S6). Based on phenotypic data analysis of 295 japonica rice varieties, we identified that 96 out of these 160 genes exhibited significant phenotypic differences among their haplotypes (Table S7, Fig. S2 ). Therefore, we hypothesized that these 96 genes were candidate genes for low-N tolerance associated with LW, RW and RSR. The pathway with the highest number of enriched genes among these 96 genes was the metabolic pathway, with a total of 4 genes. The number of genes enriched in endocytosis and ribosome pathway were 2, respectively. A total of 27 subcategories were annotated for these 96 genes, including 17 biological process categories, 2 cellular component categories and 8 molecular function categories (Fig. 4). Based on previous research data, we established the following criteria: significant differential expression was defined as |log2FC| > 1 with p < 0.05 in Longjing 31 ( low-N tolerant variety), while no significant differences were observed in Songjing 10 ( low-N sensitive variety). From the initially screened 96 genes, we identified 5 genes that showed significant differential expression specifically in Longjing 3134. These five genes (Os06g0538400, Os11g0195500, Os11g0213700, Os11g0213800 and Os12g0472800) were recognized as more valuable candidate genes (Table 1). qRT-PCR analysis revealed that in Longjing 31, three of these genes were up-regulated while two were down-regulated. No significant differential expression was observed for these genes in Songjing 10 (Fig. 5). The qRT-PCR results for these five candidate genes showed consistent expression trends with the RNA-seq data.

Dominant haplotype analysis of candidate genes

The linkage disequilibrium (LD) of these five candidate genes are shown in Figs. 6A and D and 7A and D. Two different haplotypes were formed by a nonsynonymous SNP in the CDS region of two genes, Os06g0538400, Os12g0472800 (Figs. 6B and 7E). Two different haplotypes of Os06g0538400 showed significant phenotypic differences in LLW and LRW. The Hap1 of Os06g0538400 was the dominant haplotype for LLW and LRW (Fig. 6C). There were significant phenotypic differences between two haplotypes of Os12g0472800 in LWR and RSRR. Hap1 of Os12g0472800 significantly enhanced LWR compared to other haplotypes (Fig. 7E). Two SNPs in the CDS region of Os11g0195500 formed 3 haplotypes which exhibited significant phenotypic differences in LLW, HRW and LRSR. The Hap2 and Hap3 of Os11g0195500 was the dominant haplotype for LLW and LRSR, and the Hap2 was the dominant haplotype for HRW (Fig. 6E, F). Os11g0213700 and Os11g0213800 were located in the same QTL interval, and both of these two genes possessed three haplotypes which were defined by 5 and 2 SNPs in the CDS region, respectively (Fig. 7A–C). The Hap3 of Os11g0213700 was the dominant haplotype for LLW, and the Hap1 was the dominant haplotype for HRSR (Fig. 7C). No nonsynonymous SNPs were identified in the promoter region of any of these 5 genes. There were significant phenotypic differences in RWR and RSRR among different haplotypes of Os11g0213800 (Fig. 7B). Haplotypes of Os11g0213700 exhibited significant phenotypic differences in LLW, RWR and HRSR (Fig. 7C).

Analysis of gene architecture and haplotypes of Os06g0538400 and Os11g0195500. (A) Regional Manhattan plot and linkage disequilibrium (LD) heat map of Os06g0538400. (B) Gene structure of Os06g0538400. (C) Haplotype analysis of Os06g0538400. (D) Regional Manhattan plot and LD heat map of Os11g0195500. (E) Gene structure of Os11g0195500. (F) Haplotype analysis of Os11g0195500. Lowercase letters indicated significance between treatments at the P = 0.05 level. The significant difference analysis was performed using the One-way ANOVA.

Analysis of gene architecture and haplotypes of Os11g0213700, Os11g0213800 and Os12g0472800. (A) Regional Manhattan plot and linkage disequilibrium (LD) heat map of Os11g0213700 and Os11g0213800. (B) Gene structure and haplotype analysis of Os11g0213700. (C) Gene structure and haplotype analysis of Os11g0213800. (D) Regional Manhattan plot and LD heat map of Os11g0213700 and Os12g0472800. (E) Gene structure and haplotype analysis of Os12g0472800. Lowercase letters indicated significance between treatments at the 0.05 level. The significant difference analysis was performed using the One-way ANOVA.

Discussion

N fertilizer is very important for agricultural development35. If N fertilizer is applied excessively, it may result in a series of environmental and ecological problems36. Dry matter allocation is one of the important strategies for plants to adapt to low-N environment37. Under low-N condition, plants maximize dry matter accumulation by optimizing dry matter distribution38. Under low-N condition, low-N tolerant rice varieties typically show higher RW and lower LW39. Although lower LW may lead to a temporary decrease in photosynthetic efficiency, it improves plant N acquisition efficiency from the soil40. In addition, higher RSR is also closely related to the improvement of N use efficiency, because the regulation of dry matter partitioning involves complex genetic and molecular mechanisms41. Key genes in the N signaling pathway (such as NRTs and GS) are also involved in the regulation of dry matter distribution, thus affecting the low-N tolerance of plants42,43. These findings provide an important molecular basis for elucidating the relationship between dry matter distribution and low-N tolerance. Therefore, this study identified low-N tolerance genes by measuring RW, LW and RSR under high and low-N conditions.

At present, it has been studied that plants optimize resource acquisition by adjusting biomass allocation under nutrient stress conditions44. The results of this research demonstrated that under high and low-N conditions, the average LW were 42.07 and 32.14 mg, the RW were 13.61 and 12.94 mg, and the RSR were 0.33 and 0.40, respectively (Table S2). This study found that the rice varieties showed higher RSR under low-N condition (Fig. 1). This distribution pattern indicated that low-N tolerant varieties can allocate more photosynthates to roots to enhance their ability to obtain N from soil. This result is consistent with the research of Poorter7. In addition, higher RSR is also closely related to adaptive changes in root morphology, which further enhances the competitiveness of plants in low-N environment45.

Conventional QTL mapping only utilizes the genetic differences between parents, and GWAS can identify a large number of variations existed in natural populations46. Multiple QTLs related to plant weight, panicle length and other panicle traits were identified through GWAS47. By GWAS, Chen et al.48 located 75 QTLs and identified 5 candidate genes using root morphological traits including diameter and length. In this study, 295 japonica rice varieties were adopted to measure LW, RW and RSR at seedling stage under low and high-N conditions. A total of 587 genes (Table S6) were identified within the 47 QTL intervals in this research, among which 96 genes with different haplotypes will cause significant differences in different traits of 295 rice varieties. Therefore, we hypothesized that these 96 genes are low-N tolerance candidate genes related to LW, RW and RSR.

Low-N tolerance is a complex trait. Many QTLs and genes for low-N tolerance genes have been studied, such as OsMYB30549, OsGS1;150 and OsPTR951. During the last few years, the combined application of GWAS and RNA-seq has made it possible to study the genetics of complex traits52,53. For example, the N utilization-related gene OsNAC68 was successfully identified through combining GWAS and RNA-seq analyses54. In this study, RNA-seq was performed to clarify the expression differences of these 96 genes. RNA-seq was performed on them. Among the 96 haplotype variant genes, 5 genes showed significant differences in the expression of Longjing 31, and were referred to as more value candidate genes. However, there have been no reports of N related on these 5 candidate genes. Studies had shown that some low-N tolerance genes were involved in the regulation of root development and hormone signaling pathways, such as auxin and cytokinin, which play an important role in regulating RSR and root morphology55. These findings provide an important theoretical basis for molecular breeding of low-N tolerant rice. Therefore, we can continue to use the combined application of GWAS and RNA-seq to identify excellent genes associated with N utilization and acquisition.

In this study, five candidate genes were screened, among which Os11g0195500 (OsPAD4) is a known phytoalexin gene belonging to the lipase-like protein family56. This family plays a crucial role in plant immune signaling, particularly in effector-triggered immunity (ETI) and pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) pathways57. Notably, intracellular nucleotide-binding NLR receptors cooperate with helper LRR proteins from the ADR1 and NRG1 families, as well as lipase-like proteins such as PAD4, to induce ETI immune responses58. Functional annotation analysis revealed that Os11g0213700 and Os11g0213800 belong to the NBS-LRR gene family, which is typically associated with disease resistance. MAX2, a ubiquitously expressed protein in plants, contains a characteristic LRR domain and has been demonstrated to interact with KAI2 to regulate plant growth, development, and stress responses. Notably, KAI2-mediated signaling serves as a master regulator of root system architecture59. During the seedling stage, root development directly determines N acquisition efficiency. Under N-deficient conditions, plants employ adaptive strategies including enhanced lateral root formation, increased root hair density, and architectural remodeling of root systems to optimize N uptake and improve low-N tolerance60. These information supports these five candidate genes as low-N tolerance genes, so we will further verify the function. These genes showed different haplotypes, and there were significant differences among different haplotypes. The introduction of favorable alleles in rice varieties can improve N-related traits. For example, the LLW and LRW dominant haplotypes of Os06g0538400 gene showed significant advantages in ‘Liaoyan 16’ and ‘common upland rice’, respectively. The LLW and HRW dominant haplotypes of Os11g0195500 gene showed significant advantages in ‘Liaoyan 16’ and ‘Liaoxing 6’, respectively. Therefore, combining GWAS and RNA-seq is a validated strategy to identify favorable alleles and breed excellent varieties. This not only provides a new perspective for understanding the molecular mechanism of N uptake and utilization in rice, but also provides an important theoretical basis and technical support for the breeding rice varieties with low-N tolerance.

Methods

Plant materials

A collection of 295 japonica rice varieties, including both domestic (China) and international accessions, was analyzed in this study. Firstly, seed dormancy was broken for all 295 varieties, followed by surface sterilization and thorough removal of disinfectant residues. This study adopted a completely randomized two-factor design, comprising 295 varieties and 2 N concentrations, with each treatment combination replicated 3 times biologically. Seeds of each variety were subjected to hydroponic germination in a constant-temperature incubator at 31 °C for 48 h. For each variety, 64 uniformly germinated seeds with synchronized shoot lengths were selected and equally divided into two experimental groups. The germinated seeds were individually transplanted into two 96-well plates (one seedling per well), with each plate placed in a 1 L hydroponic container before being transferred to growth chambers. One group was assigned to the low-N treatment while the other received the high-nitrogen treatment. Each treatment group was established with three biological replicates, with each replicate cultured in a separate 96-well plate. Seedlings were cultivated in climate-controlled greenhouses with strict regulation of temperature and hydration: daytime temperature maintained at 23.8 °C for 10 h and nighttime temperature at 22.4 °C for 14 h, under a constant light intensity of 300 µmol/m²/s. Urea was employed as the N source. During the initial growth phase, all seedlings were grown under high-N conditions (40 ppm) for 5 days to ensure normal growth. Subsequently, the seedlings were divided and maintained under either high-N (40 ppm) or low-N (8 ppm) conditions for an additional 21 days. The nutrient solution was refreshed every 7 days throughout the experimental period34.

Phenotypic data

After 21 days of low and high N cultivation, the leaves and roots of seedings were sampled and cleaned with ultrapure water, killed out in an oven at 105 °C for 30 min, and dried to constant weight at 80 °C. The dry weights of leaves and roots were measured, and the root-shoot ratio was calculated. The relative value of each trait was represented by dividing the phenotypic value under low N condition by that under high N condition. RSR is the ratio of RW to LW.

GWAS

In this study, DNA was extracted from 295 japonica rice varieties, and Illumina HiSeq 2000 was used to perform high-throughput sequencing of qualified sample DNA. 788,396 SNPs with the lowest allele frequency above 0.05 and the deletion rate below 20% were identified and were selected for later analysis. GWAS was performed using the MLM method of Tassel 5.0 software61. The threshold for SNPs significantly associated with traits was set as P < 5.46 × 10− 6, and the Manhattan plot and Q-Q plot were drawn by CMplot software in R language62. To determine the lead SNP (most significant variant), we first removed correlated SNPs within specified physical intervals. Gene annotations within candidate QTL regions were subsequently extracted from the Ensembl Plants database (https://plants.ensembl.org/). The LDBlockShow software was used to calculate the pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) of the leading SNPs. The R2 value was calculated within the intervals of ± 2 Mb for the lead SNP. The average value was calculated based on the top 10% R2 value within the range of 1.5-2 Mb, and was recorded as the background value of LD attenuation. The LD attenuation interval of the leading SNPs was represented by the background value of LD attenuation plus 0.263. If more than two significant SNPs were located in the same LD interval, these SNPs were designated as the same QTL, and the SNP with the smallest P value was regarded as the lead SNP.

Haplotype analysis

The location of each gene was acquired through China Rice Data Center (https://www.ricedata.cn/). Using RiceSNPSeek (https://snp-seek.irri.org/), we retrieved all coding SNPs resulting in amino acid alterations (non-synonymous) within gene exons. The nonsynonymous SNPs located in the exon region and the SNPs located in the 2 kb interval of promoter before ATG were adopted for haplotype analysis.

Candidate gene prediction

Candidate genes were predicted for all genes within the LD attenuation interval of each lead SNPs based on the phenotypic data of 295 japonica rice varieties. RNA-seq data of Longjing 31 (low-N tolerant variety) and Songjing 10 (low-N sensitive variety) were adopted34. Combined with transcriptome data in the low-N tolerant variety Longjing 31, these differential expressed genes which presented phenotypic differences among different haplotypes were defined as more valuable candidate genes. The threshold for determining differential expressed genes is |log2FC| > 1 and p < 0.05.

Quantitative real-Time PCR

The TranZol Up RNA kit (TransGen Biotech) was used to extract total RNA from the samples, and the PrimeScript TM RT Master Mix (Takara Biomedical Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used to synthesize cDNA according to the instructions. The BlazeTaqTM SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix 2.0 (GeneCopoeio, Guangzhou, China) was used for qRT-PCR on the RocheLightCycler96 system. Each sample had 3 biological and technical replicates. The CT values were recorded, and the expression levels of the 5 candidate genes were calculated using the 2 −∆ ∆ CT method. OsActin1 was used as an internal control, and primers design by Primer5.0 software were listed in Table S1.

Data analysis

The mean values, ranges, and coefficients of variation of phenotypic data were recorded and organized using Microsoft Excel. Statistical correlations were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Origin 2021 was adopted to complete the drawing. KEGG and GO analyses were performed to mining enriched pathways among N-specific DEGs through the online platform (https://cloud.metware.cn/ # / tools / tool-list). Pathways showing statistical significance (p < 0.05) were regarded as significantly enriched.

Conclusions

In this study, among 295 japonica rice varieties, seedling responses to N were assessed through LW, RW, and RSR measurements. GWAS identified 47 QTL intervals, and 587 candidate genes. The results of haplotype analysis showed that 160 of the 587 genes presented different haplotype in the association panel. Among the 96 genes with significant differences among different haplotypes, 5 genes had significant differences in the expression of Longjing 31, and were referred to as more valuable candidate genes. These results provided a theoretical basis for screening low-N tolerance genes and breeding new varieties with low-N tolerant. These results provided a theoretical basis for identifying low-N tolerance genes and developing improved varieties, laying the foundation for future breeding efforts utilizing molecular marker-assisted selection or genome-editing approaches to breed novel low-N tolerant varieties.

Data availability

The RNA-seq data for this study can be found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information under the accession number PRJNA835804 (https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/, accessed on 10 June 2023).

References

Khush, G. S. What it will take to feed 5.0 billion rice consumers in 2030. Plant Mol. Biol. 59, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-005-2159-5 (2005).

Mohidem, N. A., Hashim, N., Shamsudin, R. & Che Man, H. Rice for food security: Revisiting its production, diversity, rice milling process and nutrient content. Agriculture 12 (6), 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12060741 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Natural allelic variation in a modulator of auxin homeostasis improves grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency in rice. Plant Cell 33 (3), 566–580. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8080292 (2021).

Zhou, T. et al. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer on structure and physicochemical properties of ‘super’rice starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 239, 116237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116237 (2020).

Qiong, H. O. U., Yuemin, N. I., Ting, Z. U. O., Jian, W. A. N. G. & Wuzhong, N. I. Effects of substituting chemical fertilizers with manure on rice yield and soil labile nitrogen in paddy fields of china: A meta-analysis. Pedosphere 33 (1), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedsph.2022.09.003 (2023).

Tyagi, J., Ahmad, S. & Malik, M. Nitrogenous fertilizers: Impact on environment sustainability, mitigation strategies, and challenges. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19 (11), 11649–11672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-022-04027-9 (2022).

Poorter, H. et al. Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: Meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol. 193 (1), 30–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03952.x (2012).

Hermans, C., Hammond, J. P., White, P. J. & Verbruggen, N. How do plants respond to nutrient shortage by biomass allocation? Trends Plant Sci. 11 (12), 610–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2006.10.007 (2006).

Li, H., Hu, B. & Chu, C. Nitrogen use efficiency in crops: Lessons from Arabidopsis and rice. J. Exp. Bot. 68 (10), 2477–2488. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erx101 (2017).

Moreau, D. et al. Plant traits related to nitrogen uptake influence plant-microbe competition. Ecology 96 (8), 2300–2310. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-1761.1 (2015).

Liu, L. et al. Combination of site-specific nitrogen management and alternate wetting and drying irrigation increases grain yield and nitrogen and water use efficiency in super rice. Field Crops Res. 154, 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2013.08.016 (2013).

Ju, C. et al. Root and shoot traits for rice varieties with higher grain yield and higher nitrogen use efficiency at lower nitrogen rates application. Field Crops Res. 175, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2015.02.007 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. TOND1 confers tolerance to nitrogen deficiency in rice. Plant J. 81 (3), 367–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.12736 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Genomic basis of geographical adaptation to soil nitrogen in rice. Nature 590 (7847), 600–605. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-03091-w (2021).

Lee, S. et al. Concurrent activation of OsAMT1; 2 and OsGOGAT1 in rice leads to enhanced nitrogen use efficiency under nitrogen limitation. Plant J. 103 (1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.14794 (2020).

Gao, Y. et al. MYB61 is regulated by GRF4 and promotes nitrogen utilization and biomass production in rice. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 5219. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19019-x (2020).

Santos, L. A., de Souza, S. R. & Fernandes, M. S. OsDof25 expression alters carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Arabidopsis under high N-supply. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 6, 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11816-012-0227-2 (2012).

Zhang, J. et al. NRT1. 1B is associated with root microbiota composition and nitrogen use in field-grown rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 37 (6), 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0104-4 (2019).

Hu, B., Wang, W., Chen, J., Liu, Y. & Chu, C. Genetic improvement toward nitrogen-use efficiency in rice: Lessons and perspectives. Mol. Plant 16 (1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2022.11.007 (2023).

Brachi, B., Morris, G. P. & Borevitz, J. O. Genome-wide association studies in plants: The missing heritability is in the field. Genome Biol. 12, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2011-12-10-232 (2011).

Ozsolak, F. & Milos, P. M. RNA sequencing: Advances, challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12 (2), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2934 (2011).

Zhao, K. et al. Genome-wide association mapping reveals a rich genetic architecture of complex traits in Oryza sativa. Nat. Commun. 2 (1), 467. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1467 (2011).

Huang, X. et al. Genome-wide association study of flowering time and grain yield traits in a worldwide collection of rice germplasm. Nat. Genet. 44 (1), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.1018 (2012).

Qiu, X. et al. Genome-wide association study of grain appearance and milling quality in a worldwide collection of indica rice germplasm. PLoS One. 10 (12), e0145577. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145577 (2015).

Kadam, N. N., Struik, P. C., Rebolledo, M. C., Yin, X. & Jagadish, S. K. Genome-wide association reveals novel genomic loci controlling rice grain yield and its component traits under water-deficit stress during the reproductive stage. J. Exp. Bot. 69 (16), 4017–4032. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ery186 (2018).

Ahmad, H. et al. Impact of pre-anthesis drought stress on physiology, yield-related traits, and drought-responsive genes in green super rice. Front. Genet. 13, 832542. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.832542 (2022).

Masclaux-Daubresse, C. et al. Nitrogen uptake, assimilation and remobilization in plants: Challenges for sustainable and productive agriculture. Ann. Bot. 105 (7), 1141–1157. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcq028 (2010).

Yu, J. et al. Enhanced OsNLP4-OsNiR cascade confers nitrogen use efficiency by promoting tiller number in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 19 (1), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13450 (2021).

Li, P. et al. Integrating GWAS and transcriptomics to identify candidate genes conferring heat tolerance in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1102938. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1102938 (2023).

Van Moerkercke, A. et al. CathaCyc, a metabolic pathway database built from catharanthus roseus RNA-Seq data. Plant Cell. Physiol. 54 (5), 673–685. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pct039 (2013).

Yuan, J. et al. Genetic basis and identification of candidate genes for salt tolerance in rice by GWAS. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 9958. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66604-7 (2020).

Thi Nong, H. et al. Effect of seedling nitrogen condition on subsequent vegetative growth stages and its relationship to the expression of nitrogen transporter genes in rice. Plants 9 (7), 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9070861 (2020).

Li, N. et al. Genome-wide association study and candidate gene analysis of alkalinity tolerance in Japonica rice germplasm at the seedling stage. Rice 12, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-019-0285-y (2019).

Li, J. et al. Mapping of candidate genes in response to low nitrogen in rice seedlings. Rice 15 (1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-022-00597-x (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Improving nitrogen fertilizer use efficiency and minimizing losses and global warming potential by optimizing applications and using nitrogen synergists in a maize-wheat rotation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 353, 108538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2023.108538 (2023).

Vitousek, P. M. et al. Nutrient imbalances in agricultural development. Science 324 (5934), 1519–1520. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170261 (2009).

Liu, W., Sun, Q., Wang, K., Du, Q. & Li, W. X. Nitrogen limitation adaptation (NLA) is involved in source-to‐sink remobilization of nitrate by mediating the degradation of NRT 1.7 in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 214 (2), 734–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14396 (2017).

Zayed, O. et al. Nitrogen journey in plants: From uptake to metabolism, stress response, and microbe interaction. Biomolecules 13 (10), 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13101443 (2023).

Kraiser, T., Gras, D. E., Gutiérrez, A. G., González, B. & Gutiérrez, R. A. A holistic view of nitrogen acquisition in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 62 (4), 1455–1466. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erq425 (2011).

Evans, J. & Poorter, H. J. P. C. Photosynthetic acclimation of plants to growth irradiance: The relative importance of specific leaf area and nitrogen partitioning in maximizing carbon gain. Plant Cell. Environ. 24 (8), 755–767. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00724.x (2001).

Peng, H., Yan, Z., Chen, Y., Zhao, X. & Han, W. Effects of body size and root to shoot ratio on foliar nutrient resorption efficiency in Amaranthus Mangostanus. Am. J. Bot. 106 (3), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajb2.1246 (2019).

Yan, H. et al. Transcriptome differences in response mechanisms to low-nitrogen stress in two wheat varieties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (22), 12278. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222212278 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Overexpression of cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 gene improves nitrogen absorption and utilization in potato. Horticulturae 9 (10), 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9101105 (2023).

Kiba, T. & Krapp, A. Plant nitrogen acquisition under low availability: Regulation of uptake and root architecture. Plant Cell. Physiol. 57 (4), 707–714. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcw052 (2016).

Useche, A. & Shipley, B. Plasticity in relative growth rate after a reduction in nitrogen availability is related to root morphological and physiological responses. Ann. Bot. 106 (4), 617–625. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcq144 (2010).

Wang, Q., Tang, J., Han, B. & Huang, X. Advances in genome-wide association studies of complex traits in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 133, 1415–1425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-019-03473-3 (2020).

He, N. et al. Fine mapping and cloning of a major QTL qph12, which simultaneously affects the plant height, panicle length, spikelet number and yield in rice (Oryza sativa L). Front. Plant Sci. 13, 878558. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.878558 (2022).

Chen, N. et al. Mapping of candidate genes for nitrogen uptake and utilization in Japonica rice at seedling stage. Genes 15 (3), 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes15030327 (2024).

Wang, D. et al. Overexpression of OsMYB305 in rice enhances the nitrogen uptake under low-nitrogen condition. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 369. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00369 (2020).

Tabuchi, M. et al. Severe reduction in growth rate and grain filling of rice mutants lacking OsGS1; 1, a cytosolic glutamine synthetase1; 1. Plant J. 42 (5), 641–651. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02406.x (2005).

Fang, Z. et al. Altered expression of the PTR/NRT1 homologue OsPTR9 affects nitrogen utilization efficiency, growth and grain yield in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 11 (4), 446–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12031 (2013).

Li, C. et al. GWAS and RNA-seq analysis uncover candidate genes associated with alkaline stress tolerance in maize (Zea Mays L.) seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 963874–963874. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.963874 (2022).

Huang, Z. et al. BSA-seq, and RNA-seq analyses to identify candidate genes associated with male fertility trait in Peach. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 17, 109525. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.963874 (2025).

Xin, W. et al. Candidate gene analysis for nitrogen absorption and utilization in Japonica rice at the seedling stage based on a genome-wide association study. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 12: 670861. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.670861 (2021).

Wang, X., Shen, J. & Liao, H. Acquisition or utilization, which is more critical for enhancing phosphorus efficiency in modern crops? Plant Sci. 179 (4), 302–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.06.007 (2010).

Ke, Y. et al. Rice OsPAD4 functions differently from A Rabidopsis AtPAD4 in host-pathogen interactions. Plant J. 78 (4), 619–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.12500 (2014).

Pruitt, R. N. et al. The EDS1–PAD4–ADR1 node mediates Arabidopsis pattern-triggered immunity. Nature 598 (7881), 495–499. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03829-0 (2021).

Lapin, D., Bhandari, D. D. & Parker, J. E. Origins and immunity networking functions of EDS1 family proteins. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 58, 253–276. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-010820-012840 (2020).

Tal, L. et al. C-terminal conformational changes in SCF-D3/MAX2 ubiquitin ligase are required for KAI2-mediated signaling. New. Phytol. 239 (6). https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19101 (2023).

Kosgey, J. R. et al. Dry matter accumulation and post-silking N economy of ‘stay-green’ maize (Zea Mays L.) hybrids. Eur. J. Agron. 51, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2013.07.001 (2013).

Bradbury, P. J. et al. Software for association Mappping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 23, 2633–2635. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308 (2007).

Li, X. et al. Mapping and candidate gene analysis for alkalitolerance in Japonica rice at the bud stage based on linkage mapping and Genome-Wide association study. Rice 13, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-020-00412-5 (2020).

Dong, S. S. et al. LDBlockShow: A fast and convenient tool for visualizing linkage disequilibrium and haplotype blocksbased on variant call format files. Brief. Bioinform. 22 (4), bbaa227. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaa227 (2021).

Funding

This research is financially supported by the Innovation of Specific Japonica Rice Varieties in Northeast China, Key Research & Development Program of Heilongjiang Province (GA21B002); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 32101748); Research and Application of Key Technologies for Intelligent Farming Decision Platform, An Open Competition Project of Heilongjiang Province, China, No. 2021ZXJ05A03; and the Heilongjiang Province Postdoctoral Research Startup Fund (LBH-Q20066).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.X.: methodology, software, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Y.L.: methodology, validation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. J.W.( Jiaqi Wang): investigation, validation, writing—review and editing. C.L.: investigation, writing—review and editing. M.W.: investigation, validation, writing—review and editing. H.L.: data curation, writing—review and editing. H.Z.: data curation, writing—review and editing. L.Y.: data curation, writing—review and editing.D.Z.: data curation, writing—review and editing. W.X.: Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition.J.W.( Jingguo Wang): Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, S., Liu, Y., Wang, J. et al. Mapping of low-nitrogen tolerance genes in Japonica rice at seedling stage by genome-wide association study. Sci Rep 15, 33190 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17400-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17400-8