Abstract

To investigate the impact of retinal fluid dynamics on visual outcomes in patients with treatment-naïve neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) treated in the real world over 5 years using approved AI-based fluid monitoring. Real-world data comprising OCT scans and electronic medical records from 148 patients (187 eyes) were extracted from the Fight Retinal Blindness! (FRB! ) Zürich database. OCT scans were analysed using an approved AI algorithm (RetInSight, Vienna, Austria) to quantify fluid volumes by compartements. The impact of fluid persistence and fluctuations on BCVA change was assessed using forward stepwise regression and mixed models. Fluid compartments were further categorized into quartiles (SD-Qs), and the effect of fluid fluctuations on BCVA analysed (SD-Q1 least and SD-Q4 greatest variability of fluctuations). The greatest PED fluctuations in the central 1-mm showed an accentuated BCVA decrease after 2 and 4 years (estimate: -0.07, P = 0.019; estimate: -0.15, P < 0.01). After 4 years, eyes in SD-Q4 compared with SD-Q1 with greater PED fluctuations in the central 1-mm and 6-mm area were affected by a significant mean reduction in BCVA (-5.7 letters (P = 0.013); -6.1 letters (P = 0.015)). Greater intraretinal fluid (IRF) fluctuations (central 1-mm) (SD-Q4 compared with SD-Q1) were associated with a significantly worse mean BCVA by -6.8 letters (P = 0.018) after 5 years. Fluid persistence was not associated with statistically significant BCVA changes. In routine clinical management of nAMD, greater fluctuations of PED and IRF correlate with worse BCVA outcomes over long-term follow-up. A well-suited treatment regimen is required in the real world which can be utilized with AI-based fluid monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) revolutionized various domains of medicine, and ophthalmology stands out as a prime beneficiary of AI-driven technologies1. Notably, over the past two decades, optical coherence tomography (OCT) and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapies have played pivotal roles in addressing neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD). The growing prevalence of patients has prompted a revaluation of treatment strategies to adapt and optimize therapy approaches. Integrating AI into OCT imaging will not only become necessary to manage the rising number of AMD cases but also holds the potential to achieve advances in early diagnosis, personalized treatment strategies, and, ultimately, improved patient outcomes. nAMD is characterized by the formation of macular neovascularisations (MNV) within and/or beneath the neurosensory retina, with a high risk of fluid accumulation – including sub-retinal pigment epithelial fluid (pigment epithelial detachment (PED)), subretinal fluid (SRF) and intraretinal fluid (IRF) – as well as blood exudation2. PEDs are defined as a separation of the retinal pigment epithelium and its basal lamina from the underlying bruch’s membrane3. nAMD progresses rapidly if left untreated or inadequately managed and can result in severe and irreversible vision impairment4. Intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF, which effectively reduces retinal fluid volumes and helps preserve visual acuity (VA), is the current gold standard for treating nAMD5,6,7. OCT serves as a critical and non-invasive tool for monitoring disease activity in nAMD, primarily assessing retinal thickness and the presence or absence of fluid. Almost all major studies in nAMD have defined a zero tolerance to any fluid presence on OCT scans for the retreatment criteria with anti-VEGF substances8,9,10. However, it is noteworthy that the subjective assessment of fluid presence varies among ophthalmologists and reading centres11. Quantitative fluid assessment in OCT imaging offers a distinct advantage over such qualitative fluid assessments by providing an objective and standardized method for measuring fluid presence12.

Another substantial challenge in nAMD treatment lies in the heterogenous response to anti-VEGF therapy among individual patients. Furthermore, when and if disease reactivation will reappear after a phase of disease stabilization is near unpredictable13. Despite intensive treatment, a completely dry stage of the disease is hardly ever reached in a substantial proportion of eyes.

Recent studies have independently evaluated the impact of fluid fluctuations and persistence on best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA)14,15,16. Initial findings showed that IRF correlated with poorer baseline (BSL) BCVA and long-term outcomes17,18. However, persistent IRF and SRF did not necessarily lead to worse long-term BCVA, after adjusting for BSL predictors14,15. Some studies even suggested that persistent SRF might be tolerated without losing BCVA14,19. IRF is associated with worse long term BCVA and induces the risk of developing scars15.

Recent investigations revealed that eyes which presented with high IRF volumes had worse visual outcomes compared to eyes with lower IRF volumes20,21. Evidently, the sustained presence of fluid may not be the primary factor posing a meaningful threat to vision in nAMD therapy; instead, it appears that fluid fluctuation could exert a substantial influence on the decline in VA. A recent post-hoc real-world data analysis revealed that the greatest macular fluid fluctuations affected VA negatively by a worsening of almost two Snellen Chart lines after 2 years of anti-VEGF treatment in patients with nAMD16.

Fluid persistence and fluctuations were analysed separately over a 2-year period in different data sets in three recent studies14,15,16. Our study is the first to analyse fluid fluctuations and persistence with the help of AI segmentation over 5 years of follow-up in a real-world patient data set provided by the Fight Retinal Blindness! (FRB! ) Registry of the University Hospital Zürich. The FRB! Registry is a dedicated web-based data system developed to collect data from real-world patients with retinal diseases. Its purpose is to evaluate the efficacy, safety and potential side effects of novel treatments. The advantage of the FRB! Registry, where all different treatment patterns of the real world are collected, is its high-quality data from routine clinical practice20,22,23.

The aim of our study was to investigate the impact of retinal fluid dynamics on visual outcomes using a validated and EU medical device regulation (MDR)-approved AI-based fluid monitoring clinical decision support system (CDSS) on a high-quality, real-world data set spanning 5 years.

Methods

Patient inclusion and follow-up

Patients diagnosed with treatment naïve nAMD in at least one eye were identified from the FRB! Registry of the University Hospital Zürich20,22,23. All OCT scans were imaged with a spectral domain OCT (Spectralis HRA + OCT, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). The study was conducted in adherence with the tenants of the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the institutional review board (Cantonal Ethics Committee Zurich, Switzerland) for data and by the Medical University of Vienna (Vienna, Austria) ethics committee for this post hoc analysis. The FRB! Zürich cohort has been previously described in more detail20,23 The nature of the study is exploratory and therefore p-values have to be interpreted purely in a descriptive manner. In summary, inclusion criteria were treatment-naïve eyes with nAMD, ≥ 50 years of age, a minimum follow-up of 24 months and BCVA values at the end and the beginning of each follow-up year. Exclusion criteria at BSL were subfoveal atrophy or fibrosis and other retinal diseases which potentially affected BCVA. Due to the proactive real-world scenario, patients were treated by retinal experts in a treat and extend regimen. Patients were treated with any licensed anti-VEGF agent (aflibercept or ranibizumab) and data from both eyes could be included. Only scans with > = 19 B-scans and scans with a “field of view” that indicated a fovea-centred scan were included.

To analyze long-term structural and functional (BCVA) changes, we defined a structured framework of time intervals. The follow-up began after the initial treatment phase (baseline to month 3), which was excluded from the longitudinal analysis to minimize short-term fluctuations associated with treatment initiation. Each subsbequent year of follow-up was divided into 12-month annual OCT-BCVA matching windows:

-

“Y1: Months 3–15”.

-

“Y2; Months 15–27”.

-

“Y3; Months 27–39”.

-

“Y4; Months 39–51”.

-

“Y5; Months 51–63”.

In addition to these annual OCT-BCVA matching windows, we defined cumulative follow-up intervals to evaluate progressive anatomical and functional changes over multiple follow-up years:

-

“FY2: Months 3–27”.

-

“FY3; Months 3–39”.

-

“FY4; Months 3–51”.

-

“FY5; Months 3–63”.

The time windows begin three months after the first anti-VEGF injection to account for initial treatment phase, under the assumption that by this point, the macula is expected to be dry following completion of the loading phase. Baseline to month 3 was called the initial treatment phase. The analysis of the variables of the follow-up intervals and OCT-BCVA matching window Y1 start three months after the first injection. To better understand the different time windows, they are shown in the supplementary content: supplement Fig. 1. To assess the impact of fluid dynamics on BCVA over time, we conducted analyses across both cumulative follow-up intervals and OCT-BCVA matching windows. This dual-window approach was chosen to provide both time-specific and aggregate perspectives on the relationship between fluid features and visual outcomes. Annual OCT-BCVA matching windows were used to identify whether specific post-diagnosis periods were particularly sensitive to fluid-related changes, while cumulative follow-up intervals allowed for assessment of the overall disease burden.

Patients must have received at least one anti-VEGF injection at BSL. The initial treatment phase was defined as the first 3 months after BSL. At least two OCT scans had to be available for this phase. Patients must have had at least three OCT scans in each time window to be eligible for the analysis of each respective annual OCT-BCVA matching windows. To account for the variability inherent in real-world data, we applied different time windows for assigning BCVA measurements to corresponding visits. A 30-day time window was used for months 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12, while a broader time window was applied to visits at months 15, 21, 27, 39, 45, 51, 57, and 63. This approach follows the precedent set by Chakravarthy et al.16, who used similar windows to balance data availability and temporal precision in long-term observational studies. Additionally, a 3-week window was used to match OCT scans with BCVA measurements at the specified time points. Patients who did not have at least three OCT scans in each annual OCT-BCVA matching window were excluded. These patients had missed visits or shown a suboptimal treatment response due to inadequate adherence. BCVA was measured with the Snellen Chart and converted to numbers of letters on the logarithm of the minimum angle of Resolution (logMAR) visual acuity chart. A brief description of the baseline and follow-up characteristics of the FRB! Zürich cohort can be found in Table 1.

Automated quantification of retinal fluid

OCT scans were analysed using a medical device regulation (MDR 2017/745) approved and fully automated artificial intelligence algorithm, Fluid Monitor (RetInSight, Vienna, Austria), to quantify IRF, SRF and PED in the central 1-mm and 6-mm macular area (for fluid fluctuations) and the entire central 6-mm area of the central macula (for fluid persistence). For this study, the term central macula refers to the 6-mm macular area centered on the fovea, while the central 1-mm area corresponds to the foveal center, representing the region of highest visual acuity. Each voxel of the OCT scans was classified by the algorithm based on multiscale convolutional neural networks. Each fluid compartment (IRF, SRF, PED) was segmented and quantified, in nanolitres (nL), in the central 1-mm and entire 6-mm area. The AI algorithm segmented and quantified all PEDs, including serous and fibrovascular subtypes. The full volume of each PED was measured, independent of internal content, to capture the overall RPE elevation. Figure 2 shows examples of native B-scans and B-scans segmented with the Fluid Monitor. Persistent fluid for each fluid compartment was defined as the presence of SRF and IRF on ≥ 80% or PED on ≥ 60% of all OCT scans within each annual OCT-BCVA matching window. PED as a feature was identified if the detachment of the retinal pigment epithelium was > 400 μm in width and > 75 μm in height, or > 200 μm in height as previously defined24.

B-scan segmentation with the Vienna Fluid Monitor. (a) Representative B-scan on SD-OCT (left), B-scan segmented using the Fluid Monitor algorithm: automated segmentation of intraretinal fluid (yellow) and subretinal fluid (blue) (right). (b) Representative B-scan on SD-OCT (left): automated segmentation of subretinal fluid (blue) and pigment epithelial detachment (orange) (right).

Statistical analysis and association between fluid dynamics and BCVA

The effect of all fluid variables on the change in BCVA was calculated using forward stepwise regression and mixed effect models. Forward stepwise selection was used to select explanatory variables in each annual OCT-BCVA matching windows and cumulative follow-up intervals separately. Forward selection was applied because many explanatory variables are highly correlated. The following variables were introduced into the forward stepwise regression analysis age at baseline; treatments per window; visual acuity change per window; IRF, SRF and PED volumes in the 1-mm and 1–6 mm area of each window; IRF, SRF and PED persistence in the 6-mm area of each window and IRF, SRF and PED fluctuation of the 1-mm area of each window. For the mixed effect models, we decided to include only the central 1-mm area for fluid fluctuations due to statistical multicollinearity as the central 1-mm is more likely to impact BCVA directly. The regression coefficients (estimate) indicate the strength and direction of the relationship between each predictor variable. For each study eye, the standard deviation (SD) of IRF, SRF and PED volumes on all available OCT scan volumes was computed and calculated. The inclusion of both eyes from a single patient was adjusted by incorporating a random effect for each patient in the mixed model. This method controls for the correlation between the two eyes, ensuring that the analysis accurately reflects the non-independence of the data.

For additional analysis, the SD of PED, SRF and IRF volumes was sorted into quartiles, representing quartile 1 (SD-Q1) with the least and quartile 4 (SD-Q4) with the greatest fluid fluctuations. Statistical analysis was performed with R statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A significance level of α = 0.05 was chosen for all statistical tests.

Results

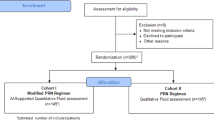

A total of 430 eyes from 215 patients were initially screened. In total, 20,590 OCT scans were evaluated. After automated determination of inclusion/exclusion criteria fulfilment based on each patient’s medical history, 235 eyes of 173 patients were eligible for this investigation. Additional manual screening of all BSL scans by two retinal experts (PF and VM) excluded 48 eyes (25 patients) due to simultaneous ocular pathologies within the central 1-mm of the macula or missing BCVA or OCT data in at least 2 years of follow-up visits and verification that the OCT scan was fovea-centered with no adjustments needed during the manual screening. The final sample consisted of 187 eyes from 148 patients with treatment-naïve nAMD (Fig. 1). Overall, 9198 OCT Scans were segmented, annotated and evaluated. A a dedicated baseline and follow-up profile for the analyzed cohort can be seen in Table 1.

Time-independent variables

The inclusion criteria were fulfilled by 187 eyes of 148 patients. Of the 148 patients, 109 had one eye and 39 had both eyes included in the study. The median age in the cohort was 79 years (CI: 73–84). The distribution of the number of patients and eyes represented per annual OCT-BCVA matching window is shown in Fig. 3.

Time-dependent variables

The mean number of injections was 3.18 (SD = 0.9) for the initial treatment phase, consistent with the completion of a full standard loading dose, 7.57 (SD = 3.1) in OCT-to-BCVA matching window Y1 (m3 - m15), 7.2 (SD = 3.42) in Y2 (m15 - m27), 7.19 (SD = 3.55) in Y3 (m27 - m39), 6.98 (SD = 3.36) in Y4 (m39 - m51), and 6.46 (SD = 3.81) in Y5 (m51 - m63). The distribution of eyes with persistent fluid for all the annual OCT-BCVA matching windows and follow up intervals is documented in the supplementary content: supplement Tables 1 and 2. The number and percent of eyes with at least one change of persistent status based of persistent status in window can be seen in the supplementary content: supplement Table 3.

Multivariable step-forward regression model for the impact of retinal fluid on VA change

A statistically significant reduction in BCVA was seen in the annual OCT-BCVA matching window Y1, after the initial treatment phase m3 until m15. The strongest association factor for this negative outcome was the BCVA at the beginning of the time window (m3) (estimate: -0.21, P-value: <0.01). The highest PED fluctuations showed a negative impact on BCVA, with significant results in the follow-up time intervals FY2 and FY4 (m3 - m27: estimate: -0.07, P-value = 0.019; m3 to m51: estimate: -0.15, P-value: <0.01). In the follow-up time interval FY5, there were no significant correlations for BCVA change from m3-m63, probably due to a large drop in the number of patients between the time windows. IRF and SRF fluctuation showed no statistically significant association with BCVA change in the multivariable model. Persistent fluid was also not significantly associated with BCVA change. The results from the multivariable step-forward regression model can be found in the supplementary content: supplement Table 4.

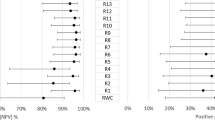

Fluid fluctuations categorized into quartiles

A consistent association between fluid fluctuation and function was identified and was dependent on fluid types. The association of fluid fluctuations (central 1-mm area) and function are illustrated for the follow-up time intervals from m3 up to 5 years (m63) in Fig. 4. In the 2 years of follow-up time interval, eyes with the highest IRF fluctuations showed worse BCVA, but without statistical significance. In the 4 years of follow-up time interval, eyes in SD-Q4 compared with those in SD-Q1 with higher PED fluctuations in the central 1-mm and 6-mm area were associated with a significant mean reduction in BCVA by -5.7 letters (P = 0.013) and by -6.11 letters (P = 0.015). SRF fluctuations did not show any trends in BCVA change when comparing quartiles SD-Q1 to SD-Q4 in the 1- and 6-mm area. Greater fluctuations in IRF (in the central 1-mm area) (SD-Q1 compared with SD-Q4) were found to be associated with a significant reduction in BCVA by -6.8 letters (P = 0.018) after 5 years of follow-up time interval (FY5). All calculated quartiles of fluid compartments and the quartile range for the central 1 mm area can be seen in the supplementary content: supplement Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14.

Mean and 95% confidence intervals of BCVA change from Month 3 to Month 15, 27, 39, 51 and 63 by IRF, SRF and PED fluctuations (Standard Deviation) in Quartiles 1 to 4 in the central 1-mm area. Mean BCVA changes for the Quartiles 1 to 4 for the OCT Biomarker of IRF fluctuation from Month 3 to Month 15 (a), Month 27 (b), Month 39 (c), Month 51 (d), Month 63 (e), BCVA changes for the Quartiles 1 to 4 for the OCT Biomarker of SRF fluctuation from Month 3 to Month 15 (f), Month 27 (g), Month 39 (h), Month 51 (i), Month 63 (j), BCVA changes for the Quartiles 1 to 4 for the OCT Biomarker of PED fluctuation from Month 3 to Month 15 (k), Month 27 (l), Month 39 (m), Month 51 (n), Month 63 (o).

Discussion

In this study, we performed a comprehensive investigation of the effects of fluid fluctuations and persistence on the change in BCVA during a 5-year follow-up of treatment-naïve nAMD eyes using a clinically available and approved AI-based fluid monitoring tool. A real-world setting analysis was made possible by data from the FRB! Registry. We found that higher fluctuations in PED and IRF were associated with a statistically significant difference in BCVA decrease over long-term follow-up.

Fluid fluctuations have been postulated to detrimentally impact long-term BCVA in nAMD eyes. The SD of macular volumes was used to measure fluctuation severity in a retrospective analysis of fluctuating macular volumes in nAMD eyes16.

We calculated the impact of fluid fluctuation by using forward stepwise regression and mixed effect models. We found that the fluctuation of PED in 2 and 4 years of follow-up time intervals(central 1-mm area) had a significant negative effect on BCVA (PED fluctuation FY2: estimate − 0.071, P = 0.019, PED fluctuation FY4: estimate: -0.147, P < 0.01). To reinforce our findings, we categorized the fluctuations into quartiles in a secondary analysis and compared them (SD-Q1 vs. SD-Q4). We found that after 4 years of follow-up time interval (FY4), of SD-Q4 compared with SD-Q1, higher PED fluctuations were associated with a significant mean reduction in BCVA by − 5.7 letters (P = 0.013) in the central 1-mm area and by -6.1 letters (P = 0.015) in the 6-mm macular area. After 5 years of follow-up time interval, eyes with the greatest IRF fluctuations (SD-Q4) compared with eyes with the least fluctuations (SD-Q1) had worse BCVA by − 6.8 letters (P = 0.018) in the central 1-mm area. Thus, the cumulative follow-up time intervals (FY1 to FY5) were chosen for the analysis, instead of analysing each year separately because RPE and photoreceptor damage seems to be a continuous and long-term process. Macular atrophy development in nAMD eyes treated with anti-VEGF is a topic of frequent discussion20,25,26. Greater fluctuations in foveal centre point thickness have been shown to correlate with developing atrophy27. Although the aetiology of macular atrophy is still unclear, the literature indicates that the main clinical risk factors for its development in nAMD eyes are the absence of SRF in the study eye, the presence of IRF in the study eye, and macular atrophy in the fellow eye at BSL25. However, not only the presence or absence of fluid might play a role in atrophy development. An association has been postulated between greater retinal thickness variation, BCVA worsening and macular atrophy development27. As shown in our study, fluid fluctuations increase the risk of vision loss, which may be related to photoreceptor and RPE damage.

Chakravarthy et al., who used SD to measure fluctuating macular fluid volumes in a 2-year follow-up of real-world patients with nAMD, found that by 2 years the fluctuation of SRF, PED and IRF had a negative impact on BCVA, with IRF showing the most linear association. They postulated that the fluctuation of total fluid (combined fluctuation of SRF, IRF and PED) had the greatest negative impact on BCVA after 2 years of follow-up in eyes treated with anti-VEGF16. In contrast to our study, we did not find significant associations between BCVA loss and SRF fluctuations over five years of follow-up. Our findings are supported by a recent study in treatment naïve nAMD eyes where significant associations between BCVA loss and fluctuations in total fluid, CSFT, IRF, and PED, but not SRF were reported in a two years follow-up28. This suggests that the impact of SRF fluctuations on BCVA may not be consistent across cohorts and highlight the need for further research to clarify its prognostic relevance. Another study reported that fluctuation in central retinal thickness caused a worse long-term BCVA in the higher quartile after 24 months of follow-up29. Although central retinal thickness is a widely recognized measure, it is not endorsed as a primary or secondary outcome measure for the quantification of exudative activity or treatment guidance30. The AI-based algorithm used in our study for quantifying retinal fluid volumes in nL across the different compartments provides a more detailed analysis than central macular thickness variation.

The question arises in clinical practice of whether the presence of persistent fluid can be tolerated or if it negatively affects visual outcomes. Our analysis did not reveal any statistically significant association of BCVA decrease in eyes with persistent SRF, IRF or PED after 5 years follow-up. Our findings are supported by other studies where non-active SRF persistence appeared to be tolerable14,15,19. The FLUID Study investigated the effect of actively tolerating a certain amount of SRF in treatment-naïve nAMD and concluded BCVA outcomes after 2 years were non-inferior to those of the SRF intolerant group (23). Nonetheless, a recent analysis of the FLUID study cohort using a trained AI-guided OCT volumetric scan quantification tool could not find a statistically significant difference in SRF volumes between the SRF tolerant and intolerant group (32).

However, researchers investigating the impact of predominantly persistent IRF on long-term BCVA in eyes enrolled in the CATT trials assigned to PRN treatment concluded that IRF was independently associated with worse long-term VA outcomes through year 2 and a higher risk of scar development15.

Due to the proactive real-world treatment regimens (treat and extend) applied in our cohort, fluid volumes may have been minimized and, hence, large fluid fluctuations generally prevented. This might explain the low fluid volumes and fluid fluctuations in our study and signal that a meaningful correlation is only identifiable in regimens where fluid presence is a criterion for retreatment. Moreover, retreatment numbers were markedly high compared with other real-world registries such as LUMINOUS31 and IRIS32 assuming that a considerable proportion of patients might have received monthly retreatment3.

The limitations of this study are all inherent to its retrospective character with a relatively small sample size. Furthermore, due to the extended follow-up period of 5 years and the real-world nature of the study, the sample size showed an important decrease, especially after year 3. Furthermore, treatment regimens and reinjection criteria are individually selected by treating physicians in routine clinical care of real-world patients. However, as with any transformative technology, challenges pertaining to data quality, validation, privacy, and algorithmic bias must be carefully addressed to ensure the ethical and clinical reliability of AI-assisted approaches.

Another limitation was the temporal shift in predictive significance - where PED fluctuation was associated with BCVA loss after cumulative follow-up intervals 2 and 4 years, while IRF fluctuation became significant after 5 years – likely reflects both methodological and biological factors. Sarraf et al. found that greater variability in PED thickness between weeks 12 and 96 was associated with significantly poorer visual outcomes suggesting PED instability as a potential marker of long-term prognosis3. Our data show wide interquartile variability in PED volumes during the cumulative follow-up time intervals 2 and 4 years, suggesting fluctuation driven impact in a subset of patients, sufficient to impact BCVA. One possible explanation is that, in large prospective anti-VEGF trials retreatment criteria typically includ new hemorrhage, loss of ≥ 5 ETDRS letters, presence or increase of IRF or SRF, but PED is not considered in these criteria, which could affect real-world treatment regimens. In contrast in Table 1 shows that IRF volumes peaked and anti-VEGF injections declined after 5 years of follow-up, which might explain the increased impact on BCVA of higher IRF fluctuations. Secondly, patients with better early outcomes or fewer recurrences are more likely to be lost to follow-up while those who remain tend to have a more aggressive or unstable disease.

A key limitation of this study is its exploratory nature. The statistical analyses conducted were aimed at descriptive interpretation rather than confirmatory conclusions. Multiple hypothesis testing was not adjusted using strict corrections (e.g., Bonferroni adjustment) to preserve the ability to detect meaningful exploratory findings. Given the exploratory nature of the study, we should rely on predefined relationships of interest based on prior assumptions and conduct targeted tests accordingly. While this approach aligns with the study’s objectives and supports the interpretation of the findings, it acknowledges the inherent trade-off of potential type I error inflation. We chose annual and cumulative windows to balance clinical relevance and statistical robustness. Annual analysis allowed us to detect potentially critical disease phases, while cumulative data reflected long-term burden. Mixed-effects models with time-varying covariates complemented this by accounting for intra-patient correlation and fluid dynamics over time.

Another limitation was that > = 19 B-scans were included for the analysis. Increasing the density of B-scans may enhance the accuracy and robustness of AI-driven fluid volume analysis in OCT. However, a prior study demonstrated that employing a minimum of 16 equally spaced B-scans consistently produces volume maps resembling ground-truth values33.

The strengths of the study are the high-quality data collected in the FRB! Platform22,23, including the large number of OCT scans from only one device (OCT Spectralis, Heidelberg, Heidelberg Engineering, Germany). Segmentation was performed using an extensively validated, reliable and MDR-approved algorithm, which benefits the comparison of fluid dynamics. Statistical analysis was performed using multiple test models to identify and report only stronger correlations.

In conclusion, this study helps to better understand the impact of fluid fluctuations and persistence on long-term BCVA. Evidence shows that specific fluid fluctuations indicating active macular neovascularizations are harmful and require a well-suited and personalised treatment regimen in the real world. Monitoring retinal fluid with an automated quantitative fluid assessment supported by AI tools and closely following fluid dynamics during the course of therapy in a prospective manner would improve the benefit and reliability of therapy. By enhancing early diagnosis, tailoring treatment strategies, and refining disease monitoring, the integration of AI into OCT imaging for nAMD represents a pivotal juncture in the advance of ophthalmic care. Further prospective studies are needed to identify the optimal fluid-related variables for compiling a reliable and comparable base for patient management in nAMD.

Data availability

The data from the Fight Retinal Blindness Zurich database are not publicly available but can be accessed upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Abràmoff, M. D. et al. Automated analysis of retinal images for detection of referable diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 131, 351–357. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.1743 (2013).

Spaide, R. F. et al. Consensus nomenclature for reporting neovascular age-related macular degeneration data: consensus on neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration nomenclature study group. Ophthalmology 127, 616–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.11.004 (2020).

Sarraf, D. et al. Pigment epithelial detachment thickness and variability affects visual outcomes in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina 44, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000003935 (2024).

Wong, T. et al. The natural history and prognosis of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 115 https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2007.03.008 (2008).

Jaffe, G. J. et al. Macular morphology and visual acuity in the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology 1860–1870 (2013).

Brown, D. M. et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 1432–1444. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMOA062655 (2006).

Rosenfeld, P. J. et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 1419–1431. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMOA054481 (2006).

Augsburger, M., Sarra, G. M. & Imesch, P. Treat and extend versus pro re Nata regimens of Ranibizumab and Aflibercept in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a comparative study. Graefe’s Archive Clin. Experimental Ophthalmol. 257, 1889–1895. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00417-019-04404-0/FIGURES/3 (2019).

Silva, R. et al. Treat-and-Extend versus monthly regimen in neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration: results with Ranibizumab from the TREND study. Ophthalmology 125, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2017.07.014 (2018).

Martin, D. F. et al. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl. J. Med. 364, 1897–1908. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMOA1102673 (2011).

Schmidt-Erfurth, U. & Waldstein, S. M. A paradigm shift in imaging biomarkers in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 50, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PRETEYERES.2015.07.007 (2016).

Keenan, T. D. L. et al. Retinal specialist versus artificial intelligence detection of retinal fluid from OCT: Age-Related eye disease study 2: 10-Year Follow-On study. Ophthalmology 128, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2020.06.038 (2021).

Funk, M. et al. Neovascular Age-related macular degeneration: intraocular cytokines and growth factors and the influence of therapy with Ranibizumab. Ophthalmology 116, 2393–2399. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2009.05.039 (2009).

Core, J. Q. et al. Predominantly persistent subretinal fluid in the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmol. Retina. 5, 962–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oret.2021.06.003 (2021).

Core, J. Q. et al. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid in the comparison of Age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmol Retina. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ORET.2022.03.024 (2022).

Chakravarthy, U. et al. Impact of macular fluid volume fluctuations on visual acuity during anti-VEGF therapy in eyes with nAMD. Eye (Basingstoke). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-01354-4 (2021).

Simader, C. et al. Morphologic parameters relevant for visual outcome during anti-angiogenic therapy of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 121, 1237–1245. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2013.12.029 (2014).

Ritter, M. et al. Intraretinal cysts are the most relevant prognostic biomarker in neovascular age-related macular degeneration independent of the therapeutic strategy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 98, 1629–1635. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJOPHTHALMOL-2014-305186 (2014).

Guymer, R. H. et al. Tolerating subretinal fluid in neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration treated with Ranibizumab using a Treat-and-Extend regimen: FLUID study 24-Month results. Ophthalmology 126, 723–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.11.025 (2019).

Reiter, G. S. et al. Long-term effect of fluid volumes during the maintenance phase in neovascular age-related macular degeneration in the real world: results from fight retinal blindness! Can. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCJO.2023.10.017 (2023).

Berni, A. et al. Topographical quantification of retinal fluid in type 3 MNV and associations with Short-Term visual outcomes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 269 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2024.08.024 (2024).

Nguyen, V., Barthelmes, D. & Gillies, M. C. Neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A review of findings from the real-world fight retinal blindness! Registry. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 49, 652–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/CEO.13949 (2021).

Mares, V. et al. Approved AI-based fluid monitoring to identify morphological and functional treatment outcomes in neovascular age-related macular degeneration in real-world routine (FRB!). Br. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJO-2022-323014 (2023).

Waldstein, S. M. et al. Morphology and visual acuity in Aflibercept and Ranibizumab therapy for neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration in the VIEW trials. Ophthalmology 123, 1521–1529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.03.037 (2016).

Sadda, S. V. R. et al. Macular atrophy in the HARBOR study for neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 125, 878–886. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2017.12.026 (2018).

Ying, G. S. et al. Sustained visual acuity loss in the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. JAMA Ophthalmol. 132, 915–921. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAOPHTHALMOL.2014.1019 (2014).

Evans, R. N. et al. Associations of variation in retinal thickness with visual acuity and anatomic outcomes in eyes with neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration lesions treated with Anti-Vascular endothelial growth factor agents. JAMA Ophthalmol. 138, 1043–1051. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.3001 (2020).

Martin-Pinardel, R. et al. Fluid fluctuations assessed with artificial intelligence during the maintenance phase impact anti-vascular endothelial growth factor visual outcomes in a multicentre, routine clinical care National age-related macular degeneration database. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 0, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJO-2024-325615 (2025).

Haji, H. et al. Association between structural and functional treatment outcomes in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 00, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/AOS.15233 (2022).

Pawloff, M. et al. A systematic correlation of central subfield thickness (CSFT) with retinal fluid volumes quantified by deep learning in the major exudative macular diseases. Ophthalmology 127, 315–319 (2020).

Holz, F. G. et al. Ranibizumab treatment patterns in prior ranibizumab-treated neovascular age-related macular degeneration patients: Real-world outcomes from the LUMINOUS study. PLoS One. 15 https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0244183 (2020).

Chiang, M. F. et al. The 2016 American academy of ophthalmology IRIS® registry (Intelligent research in Sight) database: characteristics and methods. Ophthalmology 125, 1143–1148. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2017.12.001 (2018).

Velaga, S. B. et al. Impact of optical coherence tomography scanning density on quantitative analyses in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Basingstoke). 31, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.260 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Philipp Fuchs: Performed the literature review and drafted the entire manuscript. Ursula Schmidt-Erfurth: Provided supervision of research and reviewed/edited manuscript. Leonard M. Coulibaly: Reviewed/edited manuscript. Hrvoje Bogunović: Reviewed/edited manuscript. Oliver Leingang: organizing the data, performing statistical analyses, and reviewed/edited manuscript. Anastasiia Gruber: Statistical analysis. Florian Frommlet: Statistical analysis and reviewed/edited manuscript. Virginia Mares: Reviewed/edited manuscript. Daniel Barthelmes: Reviewed/edited manuscript. Gregor S. Reiter: Provided supervision of research and reviewed/edited manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

GSR: Grant from RetInSight. US-E: Scientific consultancy for Apellis, Novartis, Roche, Heidelberg Engineering, Kodiak, RetInSight, Topcon. DB: Scientific consultancy, grants and speaker fees for Bayer and Novartis. HB: Grants from Heidelberg Engineering and Apellis. Speaker fees from Bayer, Roche, and Apellis. VM, OL, PF, LC, FF, AG: No financial support or conflicts of interest. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in adherence with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Cantonal Ethics Committee Zurich, Switzerland) for data use and by the Medical University of Vienna (Vienna, Austria) Ethics Committee for the post hoc analysis. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the need to obtain informed consent was waived by the Cantonal Ethics Committee Zurich, Switzerland, for data use, and by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, for the post hoc analysis.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fuchs, P., Schmidt-Erfurth, U., Coulibaly, L.M. et al. Impact of AI-quantified fluid dynamics on visual outcomes over 5 years in patients with treatment-naïve nAMD from the FRB! registry. Sci Rep 15, 32881 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17417-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17417-z