Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a prevalent endocrine disorder among women of reproductive age. Oxidative stress (OS) has been documented to be one of the factors involved in the pathogenesis of PCOS. This research work was designed to assess the impact of Rosa damascena (RD) extract on protective components of OS and the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox2) as OS contributors in a rat model of estradiol valerate (EV)-induced PCOS. Adult female Wistar rats (n = 48) were divided into a control group (n = 12) and a PCOS group (n = 36), with PCOS induced by EV (4 mg/kg/day). To confirm PCOS induction, 6 rats from each group underwent estrous cycle evaluation and ovarian histology. The remaining rats—6 from the control group and 30 from the PCOS group—were assigned to five subgroups: a PCOS model group, a metformin-treated group (200 mg/kg/day), and three groups receiving RD extract at doses of 400, 800, or 1200 mg/kg/day for 28 days. OS parameters and Cox2 gene expression were assessed. OS parameters and the expression of the Cox2 gene were assessed. There were significant increases in OS parameters and decreases in ROS levels in the group with higher doses of RD extract (800 and 1200 mg/kg/day) and metformin compared to the PCOS group. Moreover, there was a significant decrease in Cox2 gene expression levels (P < 0.001). The RD extract showed potential therapeutic effects in alleviating PCOS complications, which seems partly due to improving the dysregulation of OS parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine and metabolic disorder that affects 7–12% of women of reproductive age1. The diagnostic criteria for PCOS are oligo/anovulation, hyperandrogenism (clinical or biochemical), and polycystic ovaries2. PCOS is a multifactorial disorder, and various environmental, growth and genetic factors have been identified in the pathogenesis of PCOS3,4. One of the factors involved in the pathogenesis of this disease is oxidative stress (OS), which is known as an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the antioxidant defense system5. Studies have shown that biochemical parameters related to OS such as catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and total blood antioxidant capacity (TAC) are abnormal in patients with PCOS6,7. These antioxidant enzymes induce protective mechanisms against OS and contribute to the balanced production of ROS by body cells8. PCOS has been linked to metabolic conditions such as obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance (IR), and glucose intolerance9,10. There is a strong association between OS and metabolic disorders such as obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2DM), and metabolic syndrome. In other words, metabolic disorders are characterized by chronic low-grade inflammation and an imbalance between the production of ROS and the body’s ability to neutralize them with antioxidants6. Despite differences in opinions about the core pathophysiology of PCOS, it is widely accepted that this syndrome is associated with chronic inflammation11.

The ovary is a metabolically active organ and produces various growth factors and cytokines that affect metabolism and inflammation12,13. Dysfunction of ovarian metabolism has been linked to various conditions such as PCOS, obesity, and IR14,15. It is accepted that the differential diagnosis of OS from inflammation is difficult because they are usually associated with each other16. Recent evidence has shown a direct relationship between increased inflammatory cytokines and PCOS17. The expression of the cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox2) gene is low in some normal tissues and plays a role in physiological processes such as ovulation and kidney function18,19,20. It takes an upward trend in response to injury, infection, and pro-inflammatory cytokines and contributes to increased inflammation, ROS imbalance, irregular blood flow, and diabetes mellitus21,22.

Currently, the main treatment for managing PCOS includes clomiphene citrate, letrozole, tamoxifen, gonadotropin, and metformin (MET)23. Metformin, the insulin sensitizer, is an oral antihyperglycemic drug widely used to treat T2DM24. According to various studies, this drug reduces OS and inflammatory indices, improves menstrual cycle, ovulation function, IR, and increases pregnancy rate in patients with PCOS24,25. Despite being generally safe and effective, long-term MET use is linked to gastrointestinal adverse effects and vitamin B12 insufficiency. Additionally, serious possible side effects such as lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia have been reported for MET users24. Alternatively, medicinal plants with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and IR-reducing properties could be a rational source of new therapeutic agents for treating PCOS26,27.

It has been reported that Rosa damascena (RD) has pharmacological properties including antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-diabetic, and anti-aging properties28. Moreover, it has anti-inflammatory properties and is proposed as a potential therapeutic and preventive agent for various inflammatory and ROS-related conditions28,29,30. These effects may be attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds, particularly “gallic acid,” and flavonoid compounds, particularly “quercetin,” that have antioxidant effects31,32,33. In our previous study on a rat model of PCOS, RD extract showed promise in improving glycemic control, hormonal balance, lipid profiles, liver function, and ovarian health. Through analyzing the expression of the insulin-like growth factors 1 (Igf1) gene, we suggested that Igf1 could play a role in the pathology of PCOS34.

Apart from our previous study, which provided preliminary evidence that RD may positively influence key aspects of PCOS pathophysiology and supports further investigation into RD as a therapeutic option for managing PCOS, there is currently a lack of research specifically examining RD’s effects on PCOS in vitro or in animal models. Nonetheless, extensive studies have demonstrated RD’s potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, highlighting its potential in conditions marked by OS and inflammation—key mechanisms in the pathogenesis of PCOS.

For example, the crude ethanolic extract of RD flowering tops exhibited significant antioxidant activity in vitro, comparable to ascorbic acid35. Additionally, in a rat model of liver injury, RD reduced liver damage as confirmed by histopathological analysis, indicating its protective effect on tissues under OS35. Further supporting its anti-inflammatory effects, RD essential oil has been shown to reduce OS and downregulate Cox2 expression in the liver tissues of septic rats, highlighting its potential for modulating inflammatory pathways36. Similarly, a study found that the hydroalcoholic extract of RD attenuated oxidative damage in the testicular tissues of rats exposed to sodium arsenite, reinforcing its efficacy in mitigating cellular damage through antioxidant mechanisms37. Moreover, RD extract was found to elevate levels of key antioxidants, including CAT and glutathione, while simultaneously decreasing malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, a marker of OS, in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. This indicates its potential to alleviate oxidative damage and enhance the brain’s antioxidant defense mechanisms38. Further evidence shows RD’s potential for treating inflammation and OS, with studies demonstrating its anti-inflammatory effects in animal pain and swelling models29 reduction of interleukin-6 in obese rats39 and reduction of oxidative damage in a depression model40.

Collectively, these findings suggest that RD’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties may offer therapeutic benefits for managing PCOS. The current work was designed to investigate the effects of a standardized RD extract based on quercetin and gallic acid on protective components of OS and the levels of ROS and Cox2 as OS contributors in a rat model of estradiol valerate (EV)-induced PCOS.

Results

Levels of oxidative stress parameters in the ovarian tissue

Figure 1A indicated that ovarian CAT levels in the PCOS group were significantly reduced by 47% compared to the control group (P < 0.001). MET treatment resulted in an 88% increase in CAT levels relative to the PCOS group (P < 0.001). Additionally, RD extract administration at doses of 400, 800, and 1200 mg/kg led to significant increases in CAT levels by 36% (P < 0.05), 49% (P < 0.01), and 89% (P < 0.001), respectively, when compared to the PCOS group. Among these, the 1200 mg/kg dose was found to be more effective than both the 800 mg/kg (P < 0.05) and 400 mg/kg (P < 0.01) doses in enhancing CAT levels.

Ovarian levels of oxidative stress parameters in Control, PCOS, PCOS + MET, PCOS + RD 400, PCOS + RD 800, PCOS + RD 1200 groups. (A) CAT: Catalase, (B) SOD: Superoxide dismutase, (C) GPx: glutathione peroxidase. (D) TAC: Total antioxidant capacity. Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001vs control group. + P < 0.05, ++ P < 0.01 and +++ P < 0.001 vs. PCOS group. # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 vs. PCOS + RD 1200 group. PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome; MET: Metformin; RD: Rosa damascena.

Figure 1B indicated a significant 38% reduction in ovarian SOD levels in the PCOS group compared to controls (P < 0.001). MET treatment counteracted this decline, resulting in a 46% increase in SOD levels in the PCOS + MET group compared to the PCOS group (P < 0.001). Additionally, RD extract administration led to significant increases in SOD levels by 34% (P < 0.01), 41% (P < 0.01), and 48% (P < 0.001) at doses of 400, 800, and 1200 mg/kg, respectively. Even though increasing doses of RD extract led to lower ovarian SOD levels, the differences across various treatment groups did not achieve statistical significance.

Figure 1C indicated a significant 40% reduction in ovarian GPx levels in the PCOS group relative to controls (P < 0.001). MET treatment resulted in a 62% increase in GPx levels relative to the PCOS group (P < 0.001). Additionally, RD extract administration at doses of 800, and 1200 mg/kg led to significant increases in GPx levels by 44% (P < 0.01) and 58% (P < 0.001), respectively. The difference in GPx enhancement between the two RD extract doses was not statistically significant.

Figure 1D indicated a significant 47% reduction in ovarian TAC levels in the PCOS group relative to the control group (P < 0.001). MET treatment effectively counteracted this decline, leading to an 80% increase in TAC levels in the PCOS + MET group compared to the PCOS group (P < 0.001). Additionally, RD extract administration at 400, 800, and 1200 mg/kg resulted in significant TAC level increases of 46% (P < 0.05), 60% (P < 0.01), and 84% (P < 0.001), respectively. The difference in GPx enhancement between the two 800 mg/kg and 1200 mg/kg RD extract doses was not statistically significant.

Level of ROS in the ovarian tissue

Figure 2 indicated that ovarian ROS levels in the PCOS group were significantly increased by 128% compared to the control group (P < 0.001). MET treatment resulted in a 49% reduction in ROS levels relative to the PCOS group (P < 0.001). Additionally, RD extract administration at doses of 400, 800, and 1200 mg/kg led to significant reductions in ROS levels by 31% (P < 0.01), 36% (P < 0.01), and 51% (P < 0.001), respectively. Even though increasing doses of RD extract led to lower ovarian ROS levels, the differences across various treatment groups did not achieve statistical significance.

Ovarian level of ROS in Control, PCOS, PCOS + MET, PCOS + RD 400, PCOS + RD 800, PCOS + RD 1200 groups. Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). * P < 0.05 and *** P < 0.001 vs. control group. ++ P < 0.01 and +++ P < 0.001 vs. PCOS group. PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome; MET: Metformin; RD: Rosa damascena; ROS: Reactive oxygen species.

mRNA expression of Cox2

Figure 3 indicated that gene expression levels of Cox2 in the PCOS group were significantly increased by 231% relative to controls (P < 0.001). MET treatment resulted in a 61% reduction in Cox2 gene expression levels relative to the PCOS group (P < 0.001). Additionally, administration of RD extract at doses of 800 and 1200 mg/kg resulted in significant reductions in Cox2 gene expression by 56% (P < 0.001) and 63% (P < 0.001), respectively, relative to the PCOS group. The difference in Cox2 reduction between the 800 mg/kg and 1200 mg/kg doses of RD extract was not statistically significant.

Relative mRNA expression of Cox2 in Control, PCOS, PCOS + MET, PCOS + RD 400, PCOS + RD 800, and PCOS + RD 1200 groups. Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001 vs. control group. +++ P < 0.001 vs. PCOS group. PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome; MET: Metformin; RD: Rosa damascena; Cox2: Cyclooxygenase 2.

Discussion

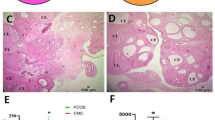

This study explored the therapeutic potential of a standardized RD extract, based on quercetin and gallic acid, in a rat model of PCOS induced by EV. This investigation focuses on the protective components of the OS, such as CAT, SOD, GPx, and TAC, while also examining ROS and Cox2 levels as contributing factors to the OS. Results showed that higher doses, specifically 800 and 1200 mg/kg of RD extract, led to significant improvements in all measured parameters. Notably, the 1200 mg/kg dose was more effective than the 800 mg/kg dose in enhancing CAT levels. The EV-induced rat PCOS model in the current research was confirmed according to our previous study based on abnormal ovarian histology and abnormal estrous cycle in animals after 28 days of continuous EV use34.

PCOS, as the most common endocrine/metabolic disorder in women during the reproductive period, is closely related to OS and chronic and low-grade inflammation2,6,9,41,42. Several lines of evidence have been linked to PCOS status to an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants7. The polyphenolic and flavonoid compounds, particularly gallic acid and quercetin as two main constituents of RD extract have been linked to antioxidant effects32,43,44,45. Several lines of evidence have reported that gallic acid may increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes, including CAT, SOD, GPx, MDA, and reduce the concentration of ovarian pro-inflammatory cytokines, DNA oxidative damage and lipid peroxidation in PCOS model rats46. Moreover, Jahan et al.45 have shown that quercetin may play a role in the improvement of ovarian cysts in PCOS via strong antioxidant potential. In the present study, the CAT, SOD, GPx and TAC levels, as antioxidant enzymes involved in OS protective pathways were significantly reduced in the PCOS group compared to the control group. Our findings showed that RD extract, particularly higher doses, could effectively increase the four enzymes in line with metformin as positive control. These results may indicate that RD extract with its high antioxidant content might have a protective effect against OS. Reviewing the findings of other researchers in the context of protective and antioxidant effects of RD extract, addressed the beneficial effects of RD extract have been extensively studied in various animal models. For instance, it has been shown to mitigate oxidative damage induced by AlCl3 intoxication in Alzheimer’s rat models47. Additionally, RD extract has been found to alleviate aluminum-induced OS, cadmium chloride (CdCl2)-induced OS, and cardiac tissue damage resulting from the CdCl2-induced OS in rat models36,48,49 Moreover, animal models of liver fibrosis showed that RD extract has been found to possess hepatoprotective activities50,51.

ROS is one of the most important indicators to measure the antioxidant effects of plant extracts51. An imbalance in ROS activity may lead to severe OS, which results in severe and excessive damage to biological molecules such as DNA, lipids, and proteins52,53. ROS levels in this study were higher in ovarian tissues of the PCOS group than in the control group. All three doses of RD extract could effectively reduce the ovarian levels of ROS as compared with the PCOS group. RD extract’s antioxidant properties may have the potential to improve OS and reduce ROS levels, which is a possible hypothesis. Kashani et al. demonstrated that antioxidants in the RD were able to neutralize the ROS and interfere with the progression of OS-related diseases54. Nikolova et al. pointed to the protective effects of RD against acute L-dopa oxidative toxicity by neutralizing ROS55,56.

It has been reported that the lack of antioxidants plays a role in reducing the sensitivity of insulin receptors57. In women with PCOS, the prevalence of IR and compensatory hyperinsulinemia is 50–70%, and it can reach 95% in overweight women55,56. Compensatory hyperinsulinemia can stimulate the production of Igf1 which shares 48% of the amino acid sequence with insulin in the liver and other tissues. Igf1 is a hormone which plays a crucial role in regulating physiological processes, including the regulation of blood glucose levels and lipid metabolism. Elevated levels of Igf1 in PCOS can contribute to several metabolic disturbances associated with the condition. In addition to the regulatory impact of Igf1 signaling on glucose and lipid metabolism, several lines of evidence have pointed to the protective role of Igf1 signaling against OS induced various conditions such as Atherosclerosis58 nerve injuries59 OS-induced apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells60. In our previous study, evaluating the effects of RD extract on Igf1 gene expression for the first time, Igf1 gene expression in PCOS rats had been increased markedly compared to the control group. Interestingly, RD extract, in addition to improving glycemic parameters, including fasting blood sugar (FBS), fasting insulin (FINS) and homeostasis model assessment-estimated insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) as well as lipid profile, implying improved insulin sensitivity and a significant decrease in IR, decreased Igf1 gene expression in PCOS rats34. The authors speculate that since in the context of PCOS, the dysregulation of Igf1 signaling may contribute to OS and elevated Igf1 levels could potentially lead to oxidative damage in cells. It is not unreasonable to assume that the beneficial effect of RD against OS may be at least in part through regulating Igf1 signaling.

In the present study, we found that in addition to the impairment of OS parameters, Cox2 was significantly increased in the PCOS group. Treatment with higher doses of RD extract could decrease the expression of the Cox2 gene in ovarian tissue in line with MET. While Cox2 plays a role in some certain physiological processes such as maintenance of renal function, it is primarily known for its role in inflammatory processes22. Previous studies’ findings have shown that Cox2 over-activated or dysregulated activity leads to increased ROS and inflammatory mediators, contributing to OS and tissue damage61,62. Another, research shows that inflammation and ROS imbalance due to increase expression of the Cox2 gene is associated with tissue irregular blood flow and diabetes mellitus21. According to the authors’ knowledge, there was no study on the effects of RD extract on the expression and levels of Cox2 gene in PCOS. It seems that the anti-inflammatory properties of RD are related to the inhibition of nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) signaling pathways as one of the main drivers of the inflammatory response. NF-kB can be activated through phosphorylation by various stimuli including ROS, hyperglycemia, and hyperandrogenism, leading to an increase in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines that are associated with IR63,64. Activation of NF-kB leads to increased expression of the Cox2 gene and is also associated with increased incidence of diabetic complications63,65. Moreover, several studies reported an interaction between Igf1 and Cox2 so that Igf1 receptor activation induces Cox2 expression which is mediated by phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K), Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and Protein kinase C (PKC) signaling pathways66,67,68. Based on our findings, we speculate that the observed reduction in Cox2 expression following RD treatment may indicate a regulatory effect on inflammatory pathways involved in the pathogenesis of PCOS.

Conclusions

In our study using a rat model of PCOS, we found that higher doses of RD extract, specifically 800 and 1200 mg/kg, significantly enhanced protective OS markers, including CAT, SOD, GPx, and TAC, on the one hand, and ROS and Cox2 levels as OS contributors, on the other hand. Given that OS is considered to be one of the key factors involved in the pathogenesis of PCOS, the findings of the current investigation suggest that RD extract may possess the potential to alleviate PCOS-related complications through the improvement of OS-associated parameters. Furthermore, this reduction may reflect the role of Cox2 in mediating OS-related disruptions, suggesting that Cox2 could be a key factor linking OS imbalance to inflammatory processes in PCOS.

Methods

Plant material and preparation of the RD hydroalcoholic extract

Freshly dried RD petals were obtained from Tabriz, East Azerbaijan, Iran, and their identity was formally confirmed by Dr. Hossein Nazemiyeh from the Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. A voucher specimen (No. Tbz-FPh4043) has been deposited in the Herbarium of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, which is publicly accessible34.

The RD extract was evaluated for its phenolic and flavonoid levels through the use of gallic acid and quercetin (Sigma Aldrich Co., USA) and was detected and quantified by HPLC34. Gallic acid and quercetin contents in RD samples were found to be 34.9 ± 3.2 mg/g and 6 ± 0.1 mg/g, respectively, when measured as dry weight. Three doses (400, 800, and 1200 mg/kg of body weight) of this extract were selected based on a previous study34.

Animals and care

Adult female Wistar rats obtained from Royan Research Institute were maintained under standard animal conditions, as detailed in the earlier research34. All experiments were carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines and in accordance with guidelines set by American Veterinary Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki for laboratory animal experiments. The current animal procedure was agreed upon by the Ethics Committee of the Science and Research Branch of Islamic Azad University in Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1397.175).

Estrous cycle monitoring

Daily vaginal smears were taken between 8 and 9 a.m. to track each animal’s estrous cycle. As described in our previous study34 the cycle stages were identified as follows: proestrus was marked by a high number of nucleated epithelial cells; estrus was noted for clusters of cornified squamous epithelial cells; metestrus showed a mix of cell types with a predominance of leukocytes and some nucleated or cornified epithelial cells; and diestrus primarily featured leukocytes. For the induction of PCOS, only rats in the estrus phase were chosen69.

Animal grouping and induction of PCOS

Female rats with regular estrous cycles were divided into two groups. The first group, consisting of 12 rats, served as the control. The second group, comprising 36 rats, received a daily intramuscular injection of EV (Aburaihan Co., Tehran, Iran) at 4 mg/kg, mixed with 0.4 mL of sesame oil, for 28 days to induce PCOS.

After the treatment period, vaginal smears were collected for 14 consecutive days to confirm PCOS induction by monitoring estrous cycle irregularities. Rats displaying disrupted estrous stages in their vaginal smears were selected as having PCOS. To further validate the model, 6 rats from each group were euthanized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (Sigma Aldrich Co., USA) at 60 mg/kg. Their ovaries were then examined histologically to verify the presence of PCOS, which was confirmed by the observation of multiple cysts, consistent with previous reports. The complete validation of the PCOS model, including histopathological confirmation, has been previously published34.

Following the induction of PCOS, the remaining animals were organized into five distinct groups, each consisting of six rats. The control group, with 6 rats, was maintained on a normal diet. The PCOS rats were divided as follows:

PCOS + RD 1200

Received 1200 mg/kg/day of RD extract orally34.

PCOS + RD 800

Received 800 mg/kg/day of RD extract orally34.

PCOS + RD 400

Received 400 mg/kg/day of RD extract orally34.

PCOS + MET

Administered 200 mg/kg/day of MET (Merck Co., Germany) as a positive control70.

PCOS group

Given 1 ml/day of normal saline.

All treatments were administered by oral gavage daily for 28 days.

Sacrifice and sample collection

After the 28-day treatment, the rats were fasted for 12 h. During the estrus stage of the estrous cycle, the animals were deeply anesthetized using an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium at a dose of 60 mg/kg (Sigma Aldrich Co., USA). Once confirmed to be unconscious, euthanasia was performed via cardiac incision. This method was chosen for its reliability and alignment with established ethical standards. Both ovaries were promptly extracted and cleaned after euthanasia.

The right ovaries were preserved in Cryovials (Greiner Bio-One GmbH Co., Germany) for molecular tests and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Finally, the collected tissues were stored at − 80 °C. The right ovaries were quickly frozen at − 80 °C for biochemical measurements.

Tissue homogenization

Ovarian tissue was homogenized in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.40) or 1.15% of 1:9, w/v KCl buffer using a manual glass homogenizer with a tissue homogenizer (Heidolph Co, Germany) in 1/10; w/v phosphate-buffered saline. The homogenate was then centrifuged for 20 min at 4000 RPM (Kokusan H-11n Co. Japan). The supernatant was separated and stored at – 80 °C until analysis.

Biochemical measurements

CAT assay

CAT activity was assessed using an ELISA kit from ZellBio Co. (Germany, Cat no. ZB-CAT-96 A) through a colorimetric method at 405 nm. This assay quantifies the amount of CAT in the sample that can convert 1 µmole of H2O2 into water and oxygen within one minute. The sensitivity of the assay is 0.5 U/mL. The reported coefficients of variation for intra-assay and inter-assay are 6.3% and 7.9%, respectively.

SOD assay

The SOD level was determined using a commercial ELISA kit (ZellBio Co., Germany, Cat no. ZB-SOD-96 A) through a colorimetric method at 420 nm. In this test, the SOD activity unit represented the quantity of the sample that would catalyze the conversion of 1 µmole of O2− into H2O2 and O2 within one minute. This method has the capability to detect SOD with a sensitivity of 1 U/mL. The claimed intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variation were 5.8% and 7.6%, respectively.

GPx assay

The GPx level was assessed using a commercial ELISA kit (ZellBio Co., Germany, Cat no. ZB-GPx-96 A) employing a colorimetric method at 412 nm. In this test, the GPx activity unit represented the quantity of the sample that would catalyze the conversion of 1 µmol of GSH to GSSG within one minute. The sensitivity of the assay is 5 U/mL, and the claimed intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variation is 6.1% and 7.7%, respectively.

TAC assay

TAC was assessed using a commercial ELISA kit from ZellBio Co. (Germany, Cat no. ZB-TAC-96 A) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. This method uses a colorimetric oxidation-reduction reaction measured at 490 nm to determine TAC levels. The antioxidant capacity in the sample was quantified relative to a standard ascorbic acid. The assay’s sensitivity is 0.1 mM (100 µmol/L), and it boasts intra-assay and inter-assay variation coefficients of under 3.4% and 4.2%, respectively.

ROS assay

Ovarian tissue was first homogenized as previously described. Subsequently, 20 µM of the fluorescent dye 2’, 7’-Dichlorofluorescin diacetates (DCF-DA) from Sigma Aldrich Co. (Germany, Cat no. 4091-99-0) was mixed with 100 µL of the tissue supernatant. The mixture was incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 45 min using an incubator from Heraeus Co. (Belgium). After incubation, 900 µL of phosphate buffer was added, and the sample was centrifuged at 2500 RPM and 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was then collected and analyzed using a flow cytometer from BD-Bio Sciences Co. (USA) at an excitation wavelength of 495 nm.

RT- qPCR analysis

Total RNA extraction from ovarian tissue was performed using the RNeasy mini kit from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany, Cat no. 74104) following the provided protocol. RNA concentration and purity were assessed with a 1000 nanodrop spectrophotometer from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) at wavelengths of 260 and 280 nm. The RNA samples were then stored at − 80 °C.

To synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA), the cDNA synthesis kit from Thermo-Fisher Scientific (Fermentas, USA, Cat. No. K1621) was utilized. The PCR reaction mix comprised 10 µL of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix Kit (Amplicon Denmark, Cat no. A190303), 1 µL of cDNA, 0.5 µL each of forward and reverse primers, and 8 µL of nuclease-free water, totaling 20 µL per reaction. The samples underwent incubation according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

Primer sequences for Cox2 and GAPDH (a housekeeping gene) were obtained from the National Biotechnology Information Center (NCBI) and are detailed in Table 1. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was conducted using the ABI Step-One system from Applied Biosystems Inc. (Foster City, CA, USA) with the following cycling conditions: 95 °C for 20 s for enzyme activation, 95 °C for 5 s for denaturation, 60 °C for 30 s for annealing, and 72 °C for 30 s for extension, repeated for 40 cycles. The relative mRNA levels in each sample were calculated based on the threshold cycle (Ct) values relative to GAPDH, using the 2 −ΔΔCT method71.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluations were conducted using Graph Pad Prism® version 06.00 software (San Diego, CA, USA). The data were expressed as mean values with standard error of the mean (SEM). To compare multiple groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied. P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Data availability

Data details can be provided by corresponding author on request.

References

Skiba, M. A., Islam, R. M., Bell, R. J. & Davis, S. R. J. H. Understanding variation in prevalence estimates of polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod .Update. 24(6), 694–709. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmy022 (2018).

Fauser B. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 81(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004 (2004).

Chaudhuri, A. Polycystic ovary syndrome: causes, symptoms, pathophysiology, and remedies. Obes. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obmed.2023.100480 (2023).

Wang, K. & Li, Y. Signaling pathways and targeted therapeutic strategies for polycystic ovary syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1191759 (2023).

Mohammadi, M. Oxidative stress and polycystic ovary syndrome: a brief review. Int. J. Prev. Med. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_576_17 (2019).

Murri, M. et al. Circulating markers of oxidative stress and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 19(3), 268–288. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dms059 (2013).

Yeon Lee, J., Baw, C-K., Gupta, S., Aziz, N. & Agarwal, A. J. C. Role of oxidative stress in polycystic ovary syndrome. Curr. Women’s Health Rev. 6(2), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.2174/157340410791321336 (2010).

Štajner, D. et al. Exploring allium species as a source of potential medicinal agents. Phytother. Res. 20(7), 581–584. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.1917 (2006).

Ehrmann DAJNEJoM. Polycystic ovary syndrome. NEJM. 352(12), 1223–1236. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199509283331307 (2005).

Genazzani, A. D. & Genazzani, A. R. Polycystic ovary syndrome as metabolic disease: new insights on insulin resistance. TouchREVIEWS Endocrinol. 19 (1), 71. https://doi.org/10.17925/EE.2023.19.1.71 (2023).

Ojeda-Ojeda, M., Murri, M., Insenser, M. & Escobar-Morreale, F. HJCpd. Mediators of low-grade chronic inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Curr. Pharm. Des. 19(32), 5775–5791 (2013).

Mohammadi MJIjopm. Oxidative stress and polycystic ovary syndrome: a brief review. Int. J. Prev. Med. 10. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_576_17 (2019).

Schmidt, J. et al. Differential expression of inflammation-related genes in the ovarian stroma and granulosa cells of PCOS women. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 20(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/molehr/gat051 (2014).

Chen, H. et al. The association between genetically predicted systemic inflammatory regulators and polycystic ovary syndrome: a Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 731569. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.731569 (2021).

Brännström Mu, Norman, R. J. H. R. Involvement of leukocytes and cytokines in the ovulatory process and corpus luteum function. Hum. Reprod. 8(10), 1762–1775. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137929 (1993)

Zuo, T., Zhu, M. & Xu, W. J. O. longevity c. Roles of oxidative stress in polycystic ovary syndrome and cancers. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8589318 (2016).

Ciaraldi, T. P., Aroda, V., Mudaliar, S. R. & Henry, R. R. J. M. Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, skeletal muscle and polycystic ovary syndrome: effects of Pioglitazone and Metformin treatment. Metab. 62(11), 1587–1596. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8589318 (2013).

Konturek, P. et al. Society paojotpp. Prostaglandins as mediators of COX-2 derived carcinogenesis in Gastrointestinal tract. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 56, 57–73 (2005).

Hu, T-Y. et al. Anti-inflammation action of Xanthones from swertia Chirayita by regulating COX-2/NF-κB/MAPKs/Akt signaling pathways in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Phytomed. 55, 214–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2018.08.001 (2019).

Cao, Z. et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression via PI3K, MAPK and PKC signaling pathways in human ovarian cancer cells. Cell. Signal. 19 (7), 1542–1553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.028 (2007).

Kaur, B. & Singh, P. J. B. C. Inflammation: biochemistry, cellular targets, anti-inflammatory agents and challenges with special emphasis on cyclooxygenase-2. Bioorg. Chem. 121, 105663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2022.105663 (2022).

Ju, Z. et al. Recent development on COX-2 inhibitors as promising anti-inflammatory agents: the past 10 years. APSB. 12(6), 2790–2807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.01.002 (2022).

Sirmans, S. M. & Pate, KAJCe. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Epidemiol. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S37559 (2013).

Costello, M. F., Shrestha, B., Eden, J., Johnson, N. P. & Sjoblom, P. J. H. R. Metformin versus oral contraceptive pill in polycystic ovary syndrome: a Cochrane review. Hum. Reprod. 22(5), 1200–1209. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dem005 (2007).

Kocer, D., Bayram, F. & Diri, H. J. G. E. The effects of Metformin on endothelial dysfunction, lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 30(5), 367–371. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2014.887063 (2014).

Artimani, T. et al. Evaluation of pro-oxidant-antioxidant balance (PAB) and its association with inflammatory cytokines in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Gynecol. Endocrinol. 34(2), 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2017.1371691 (2018).

Krystofova, O. et al. Effects of various doses of selenite on stinging nettle (Urtica dioica L.). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 7(10), 3804–3815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7103804 (2010).

Boskabady, M. H., Shafei, M. N. & Saberi, Z. Amini SJIjobms. Pharmacol. Eff. Rosa Damascena. 14 (4), 295 (2011).

Hajhashemi, V., Ghannadi, A. & Hajiloo, M. J. I. I. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Rosa damascena hydroalcoholic extract and its essential oil in animal models. IJPR. 9 (2), 163 (2010).

Afsari Sardari, F., Mosleh, G., Azadi, A., Mohagheghzadeh, A. & Badr, P. J. R. J. P. Traditional and recent evidence on five phytopharmaceuticals from Rosa damascena Herrm. RJP. 6(3), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.22127/RJP.2019.89469 (2019).

Kumar, N., Bhandari, P., Singh, B. & Bari, S. S. J. F. Antioxidant activity and ultra-performance LC-electrospray ionization-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry for phenolics-based fingerprinting of Rose species: Rosa damascena, Rosa Bourboniana and Rosa brunonii. Toxicol. C. 47 (2), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2008.11.036 (2009).

Kumar, N., Bhandari, P., Singh, B., Gupta, A. P. & Kaul VKJJoss. Reversed phase-HPLC for rapid determination of polyphenols in flowers of Rose species. J. Sep. Sci. 31(2), 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/jssc.200700372 (2008).

Özkan, G., Sagdiç, O. & Baydar, N. Baydar hjfs, international t. Note: antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Rosa damascena flower extracts. FSTI. 10(4), 277–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1082013204045882 (2004).

Farhadi-Azar, M. et al. Effects of Rosa damascena on reproductive improvement, metabolic parameters, liver function and insulin-like growth factor-1 gene expression in estradiol valerate induced polycystic ovarian syndrome in Wistar rats. Biomed. J.. 46(3), 100538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2022.05.003 (2023).

Alam, M. et al. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective action of the crude ethanolic extract of the flowering top of Rosa damascena. Adv. Traditional Med. 8 (2), 164–170. https://doi.org/10.3742/OPEM.2008.8.2.164 (2008).

Dadkhah, A. et al. Considering the effect of Rosa damascena Mill. Essential oil on oxidative stress and Cox-2 gene expression in the liver of septic rats. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 16(4), 416. https://doi.org/10.4274/tjps.galenos.2018.58815 (2019).

Khorasgani, E. M. & Mahdian, S. Protective role of Rosa damascena Miller hydroalcoholic extract on oxidative stress parameters and testis tissue in rats treated with sodium arsenite. World’s Vet. J.. 2023(2), 324–331. https://doi.org/10.54203/scil.2023.wvj35

Beigom Hejaziyan, L. et al. Effect of Rosa damascena extract on rat model alzheimer’s disease: a histopathological, behavioral, enzyme activities, and oxidative stress study. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2023 (1), 4926151 (2023).

Nasution, M. A. S., Ginting, C. N., Chiuman, L. & Lister, I. N. E. The effect of extract ethanol Rosa damascena to the Interleukin-6 Level of obese rats. InHeNce. https://doi.org/10.1109/InHeNce52833.2021.9537234 (2021).

Nazıroğlu, M., Kozlu, S., Yorgancıgil, E., Uğuz, A. C. & Karakuş, K. Rose oil (from rosa× Damascena Mill.) vapor attenuates depression-induced oxidative toxicity in rat brain. J. Nat. Med. 67, 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11418-012-0666-7 (2013).

Papalou, O., Victor, V. M. & Diamanti-Kandarakis, E. Oxidative stress in polycystic ovary syndrome. Curr. Pharm. Design. 22 (18), 2709–2722 (2016).

Goodarzi, M. O., Dumesic, D. A., Chazenbalk, G., Azziz & RJNre Polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 7 (4), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2010.217 (2011).

Memariani, Z., Amin, G., Moghaddam, G. & Hajimahmoodi, M. J. I. J. B. Comparative analysis of phenolic compounds in two samples of Rosa damascena by HPLC. CDL. 7 (1), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.12692/ijb/7.1.112-118 (2015).

Li, B. et al. Selection of antioxidants against ovarian oxidative stress in mouse model. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 31(12), e21997. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbt.21997 (2017).

Jahan, S. et al. Therapeutic potentials of Quercetin in management of polycystic ovarian syndrome using Letrozole induced rat model: a histological and a biochemical study. J. Ovarian Res. 11, 1–10 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-018-0400-5 (2018).

Mazloom, B. F., Edalatmanesh, M. A. & Hosseini, E. J. R. H. C. The effect of Gallic acid on pituitary-ovary axis and oxidative stress in rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. JRHC. 3 (1), 41–47 (2017).

Beigom Hejaziyan, L. et al. Effect of Rosa damascena extract on rat model Alzheimer’s disease: a histopathological, behavioral, enzyme activities, and oxidative stress study. eCAM. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4926151 (2023).

Hamza, R. Z. et al. Chemical characterization of Taif Rose (Rosa damascena) methanolic extract and its physiological effect on liver functions, blood indices, antioxidant capacity, and heart vitality against cadmium chloride toxicity. AOA. 11(7), 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11071229 (2022).

Rostami, M. et al. Evaluation of the flavonol-rich fraction of Rosa damascena in an animal model of liver fibrosis by targeting the expression of fibrotic cytokines, antioxidant/oxidant ratio and collagen cross-linking. Life Sci. 333, 122143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2023.122143 (2023).

Zahedi-Amiri, Z., Taravati, A. & Hejazian, L. B. J. B. T. E. R. Protective effect of Rosa damascena against aluminum chloride-induced oxidative stress. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 187, 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-018-1348-4 (2019).

Poole, K. M. et al. ROS-responsive microspheres for on demand antioxidant therapy in a model of diabetic peripheral arterial disease. Biomaterials 41, 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.11.016 (2015).

Vamanu, E. & Nita, S. J. B. Antioxidant capacity and the correlation with major phenolic compounds, anthocyanin, and tocopherol content in various extracts from the wild edible Boletus edulis mushroom. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/313905 (2012).

Liu, Y-T. et al. The antioxidant activity and hypolipidemic activity of the total flavonoids from the fruit of Rosa laevigata Michx. 2(03), 175 https://doi.org/10.4236/ns.2010.23027 (2010).

Kashani, A. D., Owlia, P., Rasooli, I. & Rezaei, M. B. J. I. T. Antioxidative properties and toxicity of white rose extract. 2011(5).

Carmina, E. & Lobo, R. A. J. F. (eds), sterility. Use of fasting blood to assess the prevalence of insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. 82(3), 661–665 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.01.041 (2004).

Dunaif AJEr. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: mechanism and implications for pathogenesis. 18(6), 774–800 https://doi.org/10.1210/edrv.18.6.0318 (1997).

Alchami, A., O’Donovan, O., Davies, M. J. O. & Gynaecology, Medicine, R. PCOS: diagnosis and management of related infertility. Gynecol. Obstet. Reprod Med. 25 (10), 279–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogrm.2015.07.005 (2015).

Higashi, Y., Sukhanov, S., Anwar, A., Shai, S. Y. & Delafontaine, P. IGF-1, oxidative stress and atheroprotection. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 21 (4), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2009.12.005 (2010).

Sha, Y. et al. The roles of IGF-1 and MGF on nerve regeneration under Hypoxia- ischemia, inflammation, oxidative stress, and physical trauma. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 24 (2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389203724666221208145549 (2023).

Baregamian, N., Song, J., Jeschke, M. G., Evers, B. M. & Chung, D. H. IGF-1 protects intestinal epithelial cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. J. Surg. Res. 136 (1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2006.04.028 (2006).

Yapca, O. E. et al. Controlled reperfusion for different durations in the treatment of ischemia–reperfusion injury of the rat ovary: evaluation of biochemical features, molecular gene expression. Histopathology 93 (4), 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2014-0359 (2015).

Li, B. et al. COX-2 Inhibition improves immune system homeostasis and decreases liver damage in septic rats. J. Surg. Res. 157(1), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2008.12.020 (2009).

González, F., Rote, N. S., Minium, J., Kirwan JPJTJoCE & Metabolism. Increased activation of nuclear factor κB triggers inflammation and insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91(4), 1508–1512. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2005-2327 (2006).

González, F., Nair, K. S., Daniels, J. K., Basal, E. & Schimke, J. M. Hyperandrogenism sensitizes mononuclear cells to promote glucose-induced inflammation in lean reproductive-age women. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metabol. 302 (3), E297–306. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00416.2011 (2012).

Meyerovich, K., Ortis, F. & Cardozo, A. K. J. J. The non-canonical NF-κB pathway and its contribution to β-cell failure in diabetes. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 61(2), F1–F6. https://doi.org/10.1530/JME-16-0183 (2018).

Cao, Z. et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression via PI3K, MAPK and PKC signaling pathways in human ovarian cancer cells. Cell. Signal. 19(7), 1542–1553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.028 (2007).

Stoeltzing, O. et al. Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression in human pancreatic carcinoma cells by the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-IR) system. Cancer Lett. 258 (2), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2007.09.009 (2007).

Tian, J. et al. Transgenic insulin-like growth factor-1 stimulates activation of COX-2 signaling in mammary glands. Mol. Carcinog. 51 (12), 973–983. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.20868 (2012).

Marcondes, F., Bianchi, F. & Tanno, A. J. B. Determination of the estrous cycle phases of rats: some helpful considerations. Braz. J. Biol. 62, 609–614. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842002000400008 (2002).

Mvondo, M. A., Mzemdem Tsoplfack, F. I., Awounfack, C. F. & Njamen, D. J. B. C. M. Therapies. The leaf aqueous extract of Myrianthus arboreus P. Beauv.(Cecropiaceae) improved letrozole-induced polycystic ovarian syndrome associated conditions and infertility in female Wistar rats. BMC Comp. Altern. Med. 20, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-020-03070-8 (2020).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. J. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods. 25 (4), 402–408. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the Deputy of Research and Technology at Shahid Beheshti University for their financial support of this project. We also acknowledge the contributions of all participants who took part in the study. This research received funding from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran.

Funding

This study funded by the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant number: 3-43016743).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.F-A Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. F.M Visualization, Investigation, review & editing, Conceptualization. M.M Software, Data curation. M.SGN Methodology. M.F Methodology. P.Y Visualization, Methodology. F. RT Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farhadi-Azar, M., Mahboobifard, F., Mousavi, M. et al. Therapeutic efficacy of Rosa damascena Mill. on oxidative stress parameters and cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in estradiol valerate-induced polycystic ovarian syndrome in Wistar rats. Sci Rep 15, 34428 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17484-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17484-2