Abstract

Copper pollution in hypersaline environments poses a significant challenge due to the inefficiency of conventional bioremediation strategies under high salinity and metal stress. Halophilic archaea represent a promising solution for heavy metal removal in saline environments due to their biocompatibility and cost-effectiveness. Here, we investigated the copper removal potential of a Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5, a halophilic archaeon isolated from the Urmia Lake in Iran. This strain exhibited copper tolerance (MIC: 80 mg/L Cu²⁺) and tolerance to several other toxic metals, including cadmium (Cd²⁺), cobalt (Co²⁺), lead (Pb²⁺), zinc (Zn²⁺), and arsenite (As³⁺) under 15% (w/v) salinity. A Central Composite Design (CCD) was employed within the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize three key parameters: pH, initial copper concentration, and inoculum percentage, to maximize copper removal. The resulting model was statistically significant (R² = 0.9972, p < 0.0001) and attained a maximum copper removal efficacy of 90.8% at pH 8.1, 28.8 mg/L Cu²⁺, and 4.8% (v/v) inoculum. Microscopic and spectroscopic analyses revealed that copper removal occurred through both biosorption and bioaccumulation mechanisms, supported by increased extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) production and specific functional group interactions identified via FTIR. The results demonstrate that Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 exhibits marked tolerance to copper and efficiently removes copper ions from saline environments, making it a valuable candidate for sustainable bioremediation under extreme conditions. This is the first report on optimization of copper bioremoval in a Halalkalicoccus strain using RSM, underscoring its biotechnological significance for green environmental management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contamination from copper ions (Cu²⁺) in water threatens aquatic ecosystems and human health, as copper can penetrate aquatic ecosystems directly and indirectly1,2. Due to water’s high solvating capacity, maintaining its purity is challenging. Over recent years, the increasing contamination of aquatic ecosystems has had a significant impact on living organisms3. The United Nations World Water Development Report (WWDR) highlights that one of the major factors causing environmental pollution is the inefficient management of wastewater. Approximately 80–90% of wastewater produced worldwide remains untreated and may infiltrate surface water and groundwater and pollute waters and surrounding soil4. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the maximum allowable concentration of copper in drinking water is 1.3 mg/L. Exceeding this limit poses risks to human health and the environment. Therefore, effective treatment of wastewater and soil contaminated with copper is essential to reduce these risks5.

Bioremediation is an innovative, eco-friendly approach, employing living organisms such as algae, microorganisms, and plants to remove heavy metal ions from polluted sites6. Ideal bioremediation techniques should be low-cost, straightforward, and sustainable. Metal-resistant microorganisms present an efficient, economical alternative for environmental copper remediation, particularly in high-salinity settings where traditional methods often fail7,8.

Halophilic archaea are extremophilic microorganisms belonging to the Archaea domain that are well adapted to environments with elevated salt concentrations, such as salt lakes and saline industrial effluents from industries like textile, tanning, dyeing, petrochemical, oil extraction, and canning. However, they are rarely found in general industrial or municipal effluents. Most halophilic archaea display a Gram-negative-like staining behavior and employ the “salt-in” strategy to maintain osmotic balance9,10,11. These organisms possess unique physiological and molecular features, including enzymes and proteins that are adapted to work efficiently under high-salt conditions. Glycosylation of the surface layer (S-layer) proteins increases cell stability, while the accumulation of acidic amino acids on the protein surfaces, together with water molecules interacting with these negative charges, prevents protein aggregation and precipitation9.

Therefore, due to the remarkable metabolic and molecular adaptations of halophilic archaea for surviving in high-salt environments, they are considered promising candidates for the development of bioremediation strategies aimed at the removal of heavy metals from contaminated environments9,10. They can be used directly to treat industrial waste or effluents, making this method more cost-effective than utilizing non-halophilic microbial species, as it eliminates the need for pre-treatment through reverse osmosis, electrolysis, or water distillation12,13.

The key mechanisms used by halophilic archaea to cope with heavy metal stress are biosorption (passive adsorption of metals on the cell surface), bioaccumulation (active uptake into the cell), enzymatic transformation of toxic metals to less harmful forms, and precipitation of metals as insoluble particles. These metabolic strategies allow halophilic archaea to survive and function in harsh environments where conventional microbial processes are often ineffective9,10,11.

Urmia Lake, located in northwest Iran, is the largest body of saline water in the Middle East and contains elevated levels of heavy metals14. Therefore, this region is an ideal candidate for isolating strains that can tolerate heavy metals, such as copper, for potential bioremediation applications.

Several studies conducted in recent years have shown that halophilic microorganisms have good potential for heavy metal absorption. Archaea have robust cellular structures and metabolism and constitute a large group of halophilic microorganisms. However, their metal tolerance capabilities have been investigated in only a limited number of studies15. While the One Factor at a Time (OFAT) approach is common, it does not account for interactions between variables. In contrast, RSM integrates statistical and mathematical modeling to optimize multiple parameter efficiency16.

Here, we employed an RSM to investigate the copper tolerance and bio-removal efficiency of the halophilic archaeal strain Dap5. Anthocyanin colorimetric analysis was used as a cost-effective and efficient method for measuring copper ion concentrations. Additionally, the mechanisms involved in copper tolerance and removal were explored, with a focus on biosorption characterization and optimizing the bioremediation process using FTIR, SEM-EDS, and TEM analyses.

Results and discussion

Strain Dap5 formed circular, convex, medium-sized, opaque, smooth, and pinkish-orange colony morphology on SW-23 medium. By Gram staining, under bright-field microscopy, the cells were Gram-negative-like and coccoid. Figure 1 presents the microscopic and colony morphology of strain Dap5.

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of copper ions

Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5, isolated from Urmia Lake, demonstrated copper tolerance with an MIC of 80 mg/L. As shown in Fig. 2a, the isolated strain displayed enhanced growth in the presence of copper ions up to 40 mg/L compared to the control, which contrasts with the findings of Fu et al. (2025) and Choińska et al. (2018), who reported better growth in control conditions and toxic effects of copper on their strains17,18. Lewis et al. (2019) suggested that the observed phenomenon may be linked to the role of copper as a cofactor for ammonia monooxygenase enzymes in ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria19. Additionally, copper is vital for several electron carriers in these organisms, which are key to the nitrogen fixation cycle20. This hypothesis is supported by EDS analysis, which indicates a nitrogen peak in the copper-treated sample but not in the control sample, suggesting the potential of copper involvement in the nitrogen cycle in strain Dap5. However, additional experiments are required to confirm this relationship.

Effects of copper and physicochemical parameters on the growth of Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5. (a) Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of copper: Strain Dap5 showed tolerance to copper up to 80 mg/L in SW-23 medium. Notably, growth was enhanced at copper concentrations up to 40 mg/L compared to the control. Although growth was significantly reduced at 80 mg/L, the strain maintained the ability to grow at this concentration. All differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05). (b) Influence of physicochemical factors in the absence of copper: The effects of (1) Salinity, (2) pH, and (3) Temperature on Dap5 growth were assessed without copper. Optimal growth was observed at 15% NaCl, 40 °C, and pH 8.0, with the highest biomass recorded on day 6. (c) Influence of physicochemical factors in the presence of copper. (1) Copper ion concentration. (2) Salinity. (3) pH, and (4) Temperature. Under 40 mg/L copper, the strain exhibited the same optimal growth conditions (15% NaCl, 40 °C, pH 8.0) as in the absence of copper, but maximum growth was achieved one day earlier, on day 5.

Various microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and archaea, have been studied for their copper resistance. Additionally, archaea such as Halobacterium salinarum and Nitrososphaera viennensis demonstrate this resistance. While many studies have explored the bioremediation potential of microorganisms in copper-contaminated environments, research on copper removal by halophilic archaea, such as Halalkalicoccus sp., is limited21,22.

Characterization of the copper-tolerant halophilic archaeon

The Dap5 isolate grew at NaCl concentrations ranging from 10 to 30%, at temperatures between 20 °C and 40 °C, and a pH level of 6.5 to 8.5; Maximum growth was achieved at 15% NaCl, 40 °C, and pH 8.0 on day 6. The growth curves are shown in Fig. 2b.

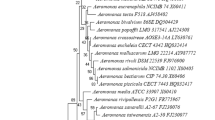

Based on the 16 S rRNA gene sequence analysis, the archaeon exhibited the highest similarity of 98.74% with Halalkalicoccus paucihalophilus DSM 24,557 over a 1046 bp region, with 70.8% completeness. The phylogenetic tree of archaeal strain Dap5 is shown in Fig. 3. The morphological characterization of the Dap5 were consistent with those described by Liu et al. (2013) regarding the Halalkalicoccus paucihalophilus strain DSM 24,55723. Furthermore, the optimal conditions identified here closely matched those observed in that study. Based on these findings, the strain Dap5 is designated Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 in this study.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of the 16 S rRNA gene sequence of strain Dap5 (PV052243). Strain Dap5 is closely related to species within the genus Halalkalicoccus. Methanospirillum hungatei CaP2L-L1A (MW498161) was used as the outgroup. The sequence had a length of 1046 bp with 70.8% completeness, and bootstrap values were calculated based on 500 replicates. The scale bar represents 0.02 substitutions per nucleotide site.

Growth of Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 in the presence of copper

The growth curve analyses revealed that Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 responds differently to varying copper concentration. The strain’s growth in the presence of copper at 10, 20, and 40 mg/L exceeded that observed under control conditions without copper, while higher copper concentrations significantly inhibited growth. As shown in Fig. 2c, at copper concentrations up to 40 mg/L Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 reached maximum growth one day earlier, on day 5.

Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 exhibited optimal growth at 15% (w/v) NaCl with 40 mg/L copper, similar to its growth in the absence of copper. In contrast, Al-Mailem et al. (2018) reported that optimal salt concentrations for growth varied with copper presence in other isolates, reporting improved growth at specific salinities and lower copper concentrations (10 and 20 mg/L CuSO₄)24, whereas Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 showed better performance at 40 mg/L copper. This study also indicated that copper supplementation shortened the occurrence maximum growth by one day, diverging from Feng et al. (2020), who highlighted copper toxicity in Acidithiobacillus caldus25.

As shown in Fig. 2b–c, the growth curves were plotted on a semi-logarithmic scale (Log10 on the y-axis) to accurately represent the growth of Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5. This adjustment enabled precise identification of the exponential phase and determination of the timing of maximum growth. Notably, the exponential phase of growth is depicted as a straight line on this semi-logarithmic plot, allowing for precise identification of the exponential growth phase and determination of the timing of maximum growth.

A study showed that environmental pH significantly affects the bioavailability of heavy metal ions and their affinity for cell surface ligands, making pH as a key factor in metal ion tolerance26. The optimal growth of Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 in SW broth occurred at 15% (w/v) NaCl, 40 mg/L copper, temperature of 40 °C, and pH of 8.0. This finding aligns with the study of Majumder et al. (2017), which identified pH 8.0 as optimal for Acinetobacter guillouiae in MSM (Minimal Salt Media) medium with 80 mg/L Coper, while observing reduced growth at pH levels below 6.0 and above pH 8.0. with maximum biomass (3.2 g/L) at pH 8.0 under control conditions27.

Optimization and characterization of copper biosorption by Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 using response surface methodology

The RSM-based Central Composite experimental design was employed to optimize the copper biosorption. A total of 20 experiments were designed and executed, as shown in Fig. 4a. The key parameters for this study were pH, inoculation percentage, and initial copper concentration.

Experiments were conducted according to the software-generated experimental matrix. To quantify the residual copper in each batch, standard curves were established using anthocyanin extracted from eggplant peels (Fig. 4b1) and cyanidin extracted from red cabbage (Fig. 4b2).

Anthocyanins are water-soluble pigments known for their strong UV-visible absorbance, served as sensitive indicators. Parizadeh et al. (2023) demonstrated that eggplant (Solanum melongena) peels-derived anthocyanins can detect copper ions between concentration range of 10 to 400 mg/L28. Additionally, Khaodee et al. (2021) revealed that red cabbage (Brassica oleracea) anthocyanins can measure copper ion concentrations as low as 20 mg/L29,30. The present study employed anthocyanins from both sources to measure copper ion concentrations. The copper removal efficiency of Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 was calculated as the system response; results are presented in Fig. 4a.

Analysis of variance

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the statistical validity of the experimental data and partition the variation attributable to individual model factors. The two-way ANOVA confirmed that a quadratic polynomial model adequately fit the data for copper removal, with detailed results provided in Table 1.

The selected model was statistically significant, while the lack-of-fit was not, indicating a suitable model fit. The parameters with p-values less than 0.05 are considered significant. This suggests the selected quadratic model effectively described the relationship between independent variables (pH, inoculation percentage, and metal concentration) and the response variable (copper removal efficiency) for Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5. Most factor interactions were statistically significant, with the exception of the interaction between inoculation percentage and pH, and one second-order interaction involving copper concentration. These results underscore the importance of key interaction terms in the model.

The determination regression coefficients (R²) and adjusted R² (R²Adj) for copper removal indicated a high dependence and correlation between observed and predicted values of responses. The adjusted coefficient of determination (R²Adj = 0.9947) showed that the model explained 99.47% of the total experimental variance. Furthermore, the predicted R² (R²pred = 0.9885) demonstrated strong predictive capability, with a difference of less than 0.2 compared to the adjusted R², further supporting the model’s validity. Regression coefficients are summarized in Table 1.

Therefore, this quadratic model is both statistically significant and suitable for describing the effects of pH, inoculation percentage, and copper concentration on copper removal by Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5. The following significant polynomial quadratic model describes the empirical relationship between the response and the independent variables. Positive coefficients indicate direct effects, while a negative coefficient indicates inverse effects.

Analysis of residual graphs

Figure 5a illustrates the key diagnostic plots used to evaluate the model. The normal probability plot (Fig. 5a1) indicates that the residuals are evenly distributed around the reference line, confirming data normality. The Random scatter in the Residuals vs. Predicted (Fig. 5a2) and Residuals vs. Run (Fig. 5a3) plots suggests both model adequacy and independence of errors across experimental runs. Cook’s Distance (Fig. 5a4) values remain below the critical threshold, indicating no influential outliers are present. The Box-Cox plot (Fig. 5a5) shows that the current Lambda is close to the optimal value and within acceptable limits, so data transformation is unnecessary. Collectively, these analyses support the validity and statistical adequacy of the model.

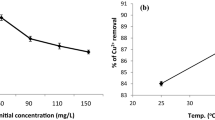

Analysis of residual graphs, 2-D and 3-D response surface plots, and desirability ramp for optimizing copper removal parameters. (a) Diagnostic residual plots: (1) Normal probability plot confirmed the normality assumption; (2) Residuals vs. predicted values showed a random scatter, indicating homoscedasticity and model adequacy; (3) Residuals vs. run order confirmed the independence of residuals over time; (4) Cook’s distance plot revealed no influential outliers; and (5) Box-Cox plot indicated that no data transformation was required. These diagnostics collectively confirm the adequacy and validity of the fitted model. (b) 2D and 3D response surface plots. In all plots, the red color indicates the highest response, while dark blue represents the lowest response. For each 3D plot, the third parameter is fixed at its central value. (1) The A-axis denotes pH and the B-axis shows inoculation percentage. (2) The A-axis indicates pH and the B-axis shows the initial copper concentration. (3) The A-axis represents inoculation percentage and the B-axis shows the copper concentration. (c) Desirability ramp charts for the optimization of initial solution pH, copper concentration, and inoculation percentage to maximize copper removal efficiency. The optimal values for each parameter and the predicted maximum removal percentage are indicated. This figure was created by using Design-Expert software (version 12.0.3.0, Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, USA).

Analysis of 2D and 3D surface response plots

Figure 5b presents 2D and 3D response surface plots illustrating the interactive effects of process variables on copper removal efficiency. Figure 5b1 shows that increasing both pH (Factor A) and inoculation percentage (Factor B) leads to higher copper removal efficiency. Figure 5b2 demonstrates that lower copper concentrations, combined with optimal inoculation percentages, improve removal. Figure 5b3 highlights that higher pH values and lower copper concentrations together enhance biosorption efficiency. Overall, these plots provide visual insight into how adjusting these variables can optimize copper removal.

Copper removal optimization

Figure 5c shows the optimization ramp plot for copper removal. All parameters were maintained within their specified ranges to maximize copper removal efficiency, and the most favorable conditions identified by the desirability function were selected for further testing.

The optimal conditions predicted by the software for copper bioremediation were pH 8.1, copper concentration 28.8 mg/L, and inoculation percentage 4.8%, with a predicted removal efficiency of 92.0%. Experimental validation under these conditions yielded a copper removal rate of 87.3% as measured by anthocyanin-based sensing and 90.8% by ICP-MS, both values closely aligning with the model prediction. Analysis of the washing solution from treated cells indicated that 19.88% of the removed copper (2.5 mg/L) was desorbed, confirming that a significant fraction of copper was adsorbed onto the biomass during biosorption. Examination of the cell pellet further verified copper accumulation, supporting the occurrence of both surface adsorption and possible intracellular uptake.

These results are in line with earlier studies showing that pH, copper concentration, and inoculation percentage are critical factors influencing the efficiency of microbial copper removal. Variations in pH impact biosorption by affecting cell surface charge, membrane permeability, and metal ion valency. Previous research on various microbial strains (e.g., Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Pseudomonas azotoformans, and Microbacterium oxydans) confirms that higher pH and optimized copper and biosorbent levels enhance biosorption efficiency18,30,31,32,33.

Overall, this study underscores the importance of optimized experimental parameters for effective heavy metal remediation using halophilic microorganisms. However, since experiments were performed under controlled laboratory conditions and not with real wastewater, further studies are necessary to evaluate the applicability of these findings in real-world conditions.

SEM-EDS analysis

SEM assessed the morphological changes due to copper ion removal in Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 (Fig. 6a1, 6b1). The analysis showed a marked increase in extracellular polymeric compounds in the treated samples compared to the control group. Based on previous studies, these compounds possess a negative charge due to the presence of functional groups such as deprotonated carboxyl, phosphate, and sulfate groups at neutral or alkaline pH. This negative charge enables them to non-specifically bind metal cations, thereby limiting the entry of heavy metal ions into the cells and reducing their toxic effects34.

Despite this increase, no differences in cell size or appearance were observed. However, treated samples displayed copper deposits on their surfaces. These findings align with EDS elemental analysis (Fig. 6b3), which confirmed the presence of copper in treated cells, while control cells showed no copper on their surface. The detailed weight percentages of all detected elements are presented in Fig. 6. A similar metal bioremoval mechanism was reported by Lin et al. (2020) and Feng et al. (2020)25,35.

Mechanisms of copper removal and interaction with surface functional groups in Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 using SEM, TEM, EDS, and FTIR analyses. (a) Control sample and (b) Copper-treated sample: (1) SEM images show an increase in EPS production in the copper-treated sample; (2) TEM images highlight bioaccumulated copper, indicated by the red arrow in the treated sample; (3) Both the EDS spectra and the corresponding tables of elemental weight percentages demonstrate copper biosorption on the cell surface. (c) FTIR spectra identify functional groups involved in copper binding to the cells, where the red graph represents copper-treated cells and the black graph represents control cells.

TEM analysis

TEM analysis was performed to investigate the impact of copper ions on Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 cells. Copper exposure resulted in dark spots within the cells, likely indicating copper accumulation (Fig. 6a2, 6b2). This observation aligns with the metal biosorption mechanism described by Lin et al. (2020)35. Moreover, the extracellular polymeric layer surrounding the control cells is relatively thinner than the treated cells, supporting the SEM micrographs of increased polymer layer production. The copper tolerance in microorganisms is associated to their ability for biosorption and chelation36. In addition, the treated samples exhibited fibrous particles in the background, within which dark particles were embedded. These dark particles may represent copper ions chelated by compounds secreted by this strain.

FTIR spectroscopic analysis

The functional groups involved in copper absorption by Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 were analyzed using FTIR spectroscopy. The FTIR spectra of cells grown with and without copper (Fig. 6c) showed that most peaks were shared between samples, differing by just one unique peak37. The copper-treated sample displayed a peak at 3290 cm⁻¹, corresponding of -OH stretching vibrations from alcohols and carboxylic acids, consistent with findings reported by Feng et al. (2020) for copper-treated Acidithiobacillus caldus25. Table 2 shows IR absorption peak shifts that suggest different functional groups on the surface of the strain.

Additionally, SEM micrographs suggest an increase in the secretion of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in response to copper ions. The observed peak at 3290 cm⁻¹ may be attributed to functional groups associated with EPS components. According to previous studies, these substances may include high molecular weight compounds such as polysaccharides, proteins, and nucleic acids38. Some microbial EPS can facilitate the bioremediation of toxic metal ions by mitigating oxidative stress through the formation of complex precipitates39.

In the present study, several peaks in the range of 500–4000 cm⁻¹ shifted and became sharper in the copper-treated samples, suggesting alterations in functional groups associated with copper tolerance mechanisms. Notably, significant sharpening was noted at 2937, 1621, 1398, 1054, and 624 cm⁻¹, particularly at 1621 cm⁻¹, which is attributed to alkene groups in unsaturated fatty acids and phospholipids. The peak at 1054 cm⁻¹ relates to ether and alcohol groups and potential S = O stretching in sulfoxides. These changes may indicate increased bond density and modifications in electronic distribution due to copper exposure.

Additionally, wavenumbers at 2937, 2001, and 1054 cm⁻¹ shifted to lower frequencies, indicating decreased bond energy and changes in electronic structure, notably at 2937 cm⁻¹, linked to alkyl groups in lipids. In contrast, peaks at 1621, 1398, and 624 cm⁻¹ shifted to higher frequencies, suggesting increased bond strength or altered bond polarity, particularly the considerable shift at 1621 cm⁻¹ associated with alkene groups. While these shifts are insightful, minor variations in some peaks likely negligible.

Spectral changes observed between 1400 and 720 cm⁻¹, corresponding to polysaccharides, suggest the involvement of archaeal cell wall polysaccharides are involved in copper interactions40. Overall, identifying the functional groups at microbial active sites is crucial for elucidating the biosorption mechanisms for heavy metals, as demonstrated with Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5.

Effects of toxic metal ions on copper removal and growth of Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5

Contaminated wastewater often contains a mixture of metals, which can hinder the removal of copper by microorganisms. This interference may result from competition for adsorption sites, variations in metal concentration, and alterations in adsorbent properties. Because functional groups on the cell surface are generally non-specific, other metals can compete with copper for adsorption, potentially reducing its uptake. Additionally, chemical interactions between multiple metals and the adsorbent can further decrease adsorption efficiency41.

This study investigated the simultaneous effects of zinc, arsenic, cobalt, cadmium, lead, and mercury on copper removal by Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5. The strain exhibited tolerance to all tested metal ions (Fig. 7). Quantitative analysis revealed a hierarchy in the impact of these ions on copper removal, ranked from least to most significant: cobalt, arsenic, cadmium, lead, zinc, and mercury. Findings from Kumar et al. (2020b) support these results, indicating that arsenic facilitates copper adsorption more effectively than lead, though neither enhances copper uptake as much as copper alone; synergistic effects were not observed42. These findings are consistent with the trends observed in this study.

Conclusion

This study examined copper removal and tolerance in the halophilic archaeon Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5. Although halophilic archaea are highly resistant to extreme environments, their bioremediation capacity of heavy metals remains underexplored. Here, Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 tolerated copper up to 80 mg/L, which is within the environmentally relevant range of copper pollution (2.5–10,000 mg/L)43. While conventional physicochemical methods can reduce bulk copper levels, they often leave residual ions. The bioremoval ability of Dap5 may offer an effective solution for advanced treatment and regulatory compliance44.

Previous studies on halophilic archaea and copper have primarily addressed maximum tolerated concentrations, passive removal, or molecular mechanisms, typically portraying copper as an inhibitory factor and neglecting its physiological effects or the potential for growth promotion. For instance, studies involving Halobacterium salinarum have mostly focused on measuring copper resistance, usually reporting copper as a growth-inhibiting factor, without investigating its comprehensive resistance mechanisms21,45,46,47.

In contrast, this study documented a significant increase in Dap5 growth at copper concentrations up to 40 mg/L, without alteration of optimal growth conditions and with copper serving as a growth promoter rather than an inhibitor, suggesting a potential link with copper’s role in nitrogen fixation; however, further research is required to confirm this hypothesis. Response surface methodology (RSM), was employed to systematically optimize bioremoval conditions; pH, inoculum level, and copper concentration were identified as key determinants of removal efficiency, with a maximum of 28.84 mg/L achieved. Additionally, a rapid, eco-friendly anthocyanin-based colorimetric assay was applied, providing a cost-effective and accurate alternative to conventional copper quantification.

An integrated study combining quantitative copper removal measurements with electron microscopy (including EDS mapping) visualization demonstrated that both passive (biosorption) and active (bioaccumulation) mechanisms, along with enhanced EPS production, contributed to copper removal in live Dap5 cells thus providing a broader perspective than previous studies limited to a single mechanism or dead biomass.

Due to its unique properties, Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 shows significant potential for practical, cost-effective copper remediation in wastewater and may be applicable at industrial scale. Future research should aim to optimize bioreactor conditions and investigate advances in nanobiotechnology, encapsulation techniques, such as using alginate-based beads or sheets, and genome editing to enhance removal efficiency and microbial performance, thereby supporting large-scale environmental applications.

Materials and methods

Strain and culture

The halophilic archaeal strain Dap5 was isolated from Urmia Lake, an environment with extreme conditions. It was cultured in seawater minimal medium (SW-23) containing 23% (w/v) total salts, which included (g/L): NaCl, 195; MgCl₂, 34.5; MgSO₄, 49.4; KCl, 5.0 and yeast extract, 3.048. The strain was preserved in 20% (v/v) glycerol at − 70 °C. All media were sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 20 min. Yeast extract was obtained from Ibresco (Zistkaavesh Iranian Co., Iran), and all other chemicals were purchased from Merck (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of copper ions

The broth dilution method was assessed to investigate copper’s minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). A stock solution of CuSO₄.5H2O was prepared to a final concentration of 10,000 mg/L and filter-sterilized through a 0.22 μm membrane filter (filter Membrane Solutions, USA). SW-23 minimal medium was supplemented with increasing copper concentrations of 10, 20, 40, 80, 160 mg/L. Freshly grown Dap5 (1 × 10⁸ CFU/mL) was added at 2% (v/v) to 20 mL of these media in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks and incubated at 40 °C and 150 rpm. After 6 days of incubation, optical density (OD) at 630 nm was measured using a microplate reader (MPR4, Hiperion, Germany). All experiments were performed in triplicate. The MIC was defined as the lowest copper concentration that inhibited visible growth, using copper-free controls for comparison.

Growth optimization and molecular characterization of the halophilic archaeon

To determine optimal growth conditions, the effects of NaCl concentration, temperature, and pH were examined. For NaCl optimization, 20 mL of SW medium was prepared with NaCl at 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% (w/v), inoculated with 2% (v/v) of a freshly grown culture (1 × 10⁸ CFU/mL), and incubated at 40 °C with agitation at 150 rpm. For temperature optimization, the strain was inoculated in 20 mL of SW medium and incubated at 20 °C, 30 °C, and 40 °C under the same conditions. For pH optimization, 20 mL of SW broth was adjusted to pH 6.5, 7.0, 7.5, 8.0, and 8.5 using NaOH and HCl, inoculated, and incubated as described previously. Growth was monitored by measuring optical density at 630 nm every 24 h. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

The isolated strain was identified by manually extracting genomic DNA49 and assessed by horizontal gel electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel. The 16 S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene was amplified by PCR using universal primers 21 F (5´-TTCCGGTTGATCCYGCCGGA-3’) and 1492R (5´-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’)50. The PCR reaction mixture contained 5.0 µL template DNA, 1.25 µL of each primer, 12.5 µL Taq 2X PCR Master Mix (Euro genome GmbH, Cologne, Germany), and molecular-grade water to a final volume of 30.0 µL. PCR conditions were: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, primer annealing at 60 °C for 1 min, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

The amplification of the 16 S rRNA gene was confirmed by 1% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis The PCR product was sequenced using the Sanger method by Genfanavaran Inc. (Iran). Sequence similarity was determined using the EzBiocloud server (www.ezbiocloud.net)51. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Clustal W, and phylogenetic analysis was conducted in MEGA 11 software using Kimura’s two-parameter model and the neighbor-joining (NJ) method, with bootstrap support from 500 replications. Related taxa sequences were obtained from the GenBank database. The resulting sequence has been deposited in GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and has accession number PV052243.

Effect of different parameters on the growth of Halalkalicoccus strain Dap5 in the presence of copper

Based on the prior optimization results, the growth of strain Dap5 was investigated under various conditions: copper concentrations (0, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 mg/L), NaCl concentrations (10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30%), temperatures (20 °C, 30 °C, and 40 °C), and pH (6.5, 7.0, 7.5, 8.0, and 8.5). For each experiment, 20 mL of SW broth in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks was inoculated with 2% (v/v) of a freshly grown Dap5 culture at 1 × 10⁸ CFU/mL, and incubated at 40 °C with agitation at 150 rpm. Growth was monitored by measuring OD at 630 nm at 24-hour intervals. Control flasks without copper were prepared under identical conditions. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Copper removal experiment

Experimental design and statistical analysis

Central Composite Design (CCD) was employed as an optimization tool within RSM to evaluate the effects of three independent variables on copper biosorption by the strain Dap5. The selected variables and their three levels (−1, 0, + 1), based on previous studies22,52, were:

-

A (pH): 6.5, 7.5, 8.5.

-

B (inoculation percentage): 2.0%, 4.5%, 7.0%.

-

C (initial metal concentration): 10, 45, 80 mg/L.

CCD involved 2n factorial runs, 2n axial runs, and nc center runs. The total number of experimental runs (N) is given by Eq. 1, where “n” is the number of independent factors53:

The response variable, representing the copper adsorption capacity of strain Dap5, was determined through batch adsorption, with optimization and prediction conducted using Design-Expert 12.0.0 software.

Twenty batch biosorption experiments were conducted in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 20 mL SW medium with 15% NaCl, varying in pH, copper concentration, and inoculation percentage. Media were adjusted to the desired pH values and autoclaved; copper was added and the flask left at room temperature for two hours prior to inoculation to allow any possible chemical precipitation to occur. After this incubation period, the initial copper concentration was measured, followed by inoculation with freshly grown Dap5 cultures (1 × 10⁸ CFU/mL) at the indicated percentage. Flasks were incubated under the previously determined optimal growth conditions with copper.

Anthocyanins were used to selectively bind to copper ions at pH 7.0, leading changes to color changes measured by UV-VIS spectrophotometry (Shimadzu UV160U, Japan). Anthocyanins from eggplant peel were used for determining copper concentrations of 10–100 mg/L, while cyanidin extracted from red cabbage was used for 0–10 mg/L, both obtained via solvent extraction methods. Eggplant peel anthocyanin was extracted using a modified method by Minabi-Nezhad et al. (2023) protocol, using 1.5 M HCl and 95% ethanol (15:85 ratio)54. Cyanidin was extracted by a modified Khaodee et al. (2014) method, using 2 M HCl and 95% ethanol (15:85 ratio), with purification by chloroform and concentrated HCl. The precipitated cyanidin chloride was dried and dissolved in 95% methanol at a 3:10 (w/v) ratio29. Anthocyanin extraction was confirmed by the Shinoda test, and standard calibration curves were generated for each anthocyanin in the presence of copper ions54.

After incubation, cultures were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was filtered, collected in sterile microtubes, acidified with 1 M HCl. The remaining Cu2+ ion concentration in the supernatant was analyzed using an anthocyanin colorimetric method.

All measurements were performed in triplicate. Absorbances were read at 559 nm for eggplant peel anthocyanin and 590 nm for red cabbage cyanidin. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) was also employed to validate the copper concentration results obtained through the anthocyanin method, following the Standard Method 3120 for metals analysis55. The copper removal efficiency was calculated according to Eq. 2.

Where C0 and Ce represent the initial and final copper concentrations, respectively.

Confirmation of cu²+ accumulation and adsorption

To confirm Cu²⁺ accumulation in strain Dap5, 1 g of dried biomass from cultures grown under optimized conditions was rinsed with 0.1 M HNO₃ to remove adsorbed copper ions. Two sets of biomass samples were prepared: one rinsed (to measure intracellular copper accumulated in the cells) and one non-rinsed (to determine total Cu²⁺ uptake). Both sample sets were digested using an acid oxidative solution of HNO₃ and H₂SO₄ in a 3:1 (v/v) ratio. Copper concentrations were quantified using the anthocyanin colorimetric method and ICP-MS. The amount of Cu²⁺ accumulated within the biomass was determined by subtracting the adsorbed copper (from the rinsed biomass) from total uptake (from the non-rinsed sample), as described by Kumar and Dwivedi (2021)56.

SEM and EDS analysis

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to examine the effect of copper ions (Cu2+) stress on cell surface morphology. Dap5 cells were cultured in SW broth under optimal copper removal conditions as determined earlier, alongside a control group grown without copper, both at 40 °C and 150 rpm. Samples were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min, rinsed three times with PBS (pH 7.4), fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and stored overnight at 4 °C. The cells were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (20–100%), dried, mounted, sputtered with gold, and analyzed by SEM–EDS (TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic).

TEM analysis

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) was performed to investigate intracellular copper accumulation. Dap5 was cultured in SW broth under optimal copper removal conditions, along with a control group grown without copper. Samples were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min, rinsed three times with PBS (pH 7.4), and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution. The cells were then embedded in epoxy resin, and thin sections were prepared for analysis using transmission electron microscopy (TEM Philips EM208S 100 kV, Netherlands).

FTIR spectroscopy

Fourier-transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed to identify functional groups on Dap5 cell surface involved in copper binding. Cells were cultured in SW broth under optimal copper removal conditions and in control medium without copper. Following centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 15 min, the cells were washed three times with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and dried at 45 °C for 48 h. The dried biomass was ground with KBr to a fine powder, and the IR spectrum was measured in the 500–4000 cm⁻¹ range using a Bruker Tensor 27 FT-IR Spectrometer.

Effects of other heavy metals on Cu2+ removal

To assess the impact of various heavy metals (Zn²⁺ as ZnSO4, Hg2+ as HgCl2, Cd²⁺ as CdCl2, Co²⁺ as CoCl2, Pb²⁺ as Pb(NO3)2 and As³⁺ as NaAsO2) on strain Dap5 growth and copper removal, cells were cultured in SW broth under optimized copper removal conditions. Each flask contained 10 mg/L of each metal ion plus the optimal copper concentration and was incubated at 40 °C and 150 rpm. After incubation, cultures were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant was filtered. The remaining Cu²⁺ concentration in the supernatant was analyzed using the anthocyanin colorimetric method and ICP-MS.

The concentration of 10 mg/L for each toxic metal ion was selected based on previous studies, which demonstrated that this level is sufficient to observe competitive effects without overwhelming or saturating the system. This approach provides clearer insight into the relative influence of each metal ion under environmentally relevant conditions.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 10.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) was utilized for data visualization and statistical analyses. Data were analyzed by one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett’s multiple-comparison posttest (p < 0.05). Design Expert version (version 12.0.3.0, Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN) was employed for experimental design, statistical analyses, and to generate two- and three-dimensional surface plots.

Data availability

The sequence data from this study has been submitted to GenBank (https:/www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and has accession number PV052243.

References

Yuan, Y. et al. Portable bifunctional kits for polychromatic visual assay of Tetracycline and copper(II). Microchem J. 209, 112723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2025.112723 (2025).

Jadoon, I. et al. A. F. Health risk assessment and levels of heavy metals contaminated drinking water used by both adults and children from Nawanshahr town. Global NEST J. 27 (4). https://doi.org/10.30955/gnj.07139 (2025).

Shahzad, T., Nawaz, S., Jamal, H., Akhtar, F. & Kamran, U. A review on cutting-edge three-dimensional graphene-based composite materials: redefining wastewater remediation for a cleaner and sustainable world. J. Compos. Sci. 9, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9010018 (2025).

Amoatey, P. et al. A critical review of environmental and public health impacts from the activities of evaporation ponds. Sci. Total Environ. 796, 149065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149065 (2021).

Arbabi, M. & Golshani, N. Removal of copper ions (Cu (II)) from industrial wastewater: a review of removal methods. Int. J. Epidemiol. Res. 3, 283–293 (2016).

Ayangbenro, A. S. & Babalola, O. O. A new strategy for heavy metal polluted environments: a review of microbial biosorbents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 14, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010094 (2017).

Mad, D., Voica, A., Bartha, L., Banciu, H. L. & Oren, A. Heavy metal resistance in halophilic bacteria and archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 363, fnw146. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnw146 (2016).

Abdel-Razik, M. A., Azmy, F., Khairalla, A. S. & AbdelGhani, S. Metal bioremediation potential of the halophilic bacterium Halomonas sp. strain WQL9 isolated from lake qarun, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 46, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejar.2019.11.009 (2020).

Martínez-Espinosa, R. M. Halophilic archaea as tools for bioremediation technologies. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 108 (401). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-024-13241-z (2024).

Martínez Martínez, G., Pire, C. & Martínez-Espinosa, R. M. Hypersaline environments as natural sources of microbes with potential applications in biotechnology: the case of solar evaporation systems to produce salt in Alicante County (Spain). Curr. Res. Microb. 3, 100136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmicr.2022.100136 (2022).

Mainka, T., Weirathmüller, D., Herwig, C. & Pflügl, S. Potential applications of halophilic microorganisms for biological treatment of industrial process Brines contaminated with aromatics. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 48 (1–2). https://doi.org/10.1093/jimb/kuab015 (2021). kuab015.

Dutta, B. & Bandopadhyay, R. Biotechnological potentials of halophilic microorganisms and their impact on mankind. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 11, 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-022-00252-w (2022).

Sahoo, S. & Goli, D. Bioremediation of lead by a halophilic bacterium Bacillus pumilus isolated from the Mangrove regions of Karnataka. J. Environ. Res. Dev. 9, 106–110. https://doi.org/10.21275/ART20204172 (2020).

Khosravi, R. et al. Health and ecological risks assessment of heavy metals and metalloids in surface sediments of urmia salt lake, Northwest of Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 195, 403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-023-10946-y (2023).

Krzmarzick, M. J., Taylor, D. K., Fu, X. & McCutchan, A. L. Diversity and niche of archaea in bioremediation. Bioremediat. J. 22, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3194108 (2018).

Kapahi, M. & Sachdeva, S. Bioremediation options for heavy metal pollution. J. Health Pollut. 9, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5696/2156-9614-9.24.191203 (2019).

Liu, B. B. et al. Halalkalicoccus Paucihalophilus sp. nov., a halophilic archaeon from Lop Nur region in xinjiang, Northwest of China. ANTON LEEUW INT. J. G. 103, 1007–1014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-013-9880-x (2013).

Fu, K., Fan, L., Ji, J. & Qiu, X. Copper tolerance of Trichoderma Koningii Tk10. Microbiol. Res. 16, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16010018 (2025).

Gorman-Lewis, D., Martens-Habbena, W. & Stahl, D. A. Cu(II) adsorption onto ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 255, 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2019.04.011 (2019).

Matse, D. T., Jeyakumar, P., Bishop, P. & Anderson, C. W. N. Copper induces nitrification by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea in pastoral soils. J. Environ. Qual. 52, 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20440 (2023).

Baati, H. et al. Resistance of a Halobacterium salinarum isolate from a solar saltern to cadmium, lead, nickel, zinc, and copper. ANTON LEEUW INT. J. G. 113, 1699–1711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-020-01475-6 (2020).

Reyes, C. et al. Copper limiting threshold in the terrestrial ammonia oxidizing archaeon Nitrososphaera viennensis. Res. Microbiol. 171, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2020.01.003 (2020).

Choińska-Pulit, A., Sobolczyk-Bednarek, J. & Łaba, W. Optimization of copper, lead and cadmium biosorption onto newly isolated bacterium using a Box-Behnken design. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 149, 275–283. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.12.008 (2018).

Al-Mailem, D. M., Eliyas, M. & Radwan, S. S. Ferric sulfate and proline enhance heavy-metal tolerance of halophilic/halotolerant soil microorganisms and their bioremediation potential for spilled oil under multiple stresses. Front. Microbiol. 9, 394. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00394 (2018).

Feng, S., Hou, S., Cui, Y., Tong, Y. & Yang, H. Metabolic transcriptional analysis on copper tolerance in moderate thermophilic bioleaching microorganism Acidithiobacillus Caldus. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47, 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10295-019-02247-6 (2020).

Amoozegar, M. A., Ghazanfari, N. & Didari, M. Lead and cadmium bioremoval by Halomonas sp., an exopolysaccharide-producing halophilic bacterium. Prog Biol. Sci. 2, 1–11 (2012).

Majumder, S., Gangadhar, G., Raghuvanshi, S. & Gupta, S. A comprehensive study on the behavior of a novel bacterial strain acinetobacter guillouiae for bioremediation of divalent copper. Bioproc Biosyst Eng. 38, 1749–1760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00449-015-1416-5 (2015).

Parizadeh, P., Moeinpour, F. & Mohseni-Shahri, F. S. Anthocyanin-induced color changes in bacterial cellulose nanofibers for the accurate and selective detection of Cu(II) in water samples. Chemosphere 326, 138459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138459 (2023).

Khaodee, W., Aeungmaitrepirom, W. & Tuntulani, T. Effectively simultaneous naked-eye detection of Cu(II), Pb(II), Al(III), and Fe(III) using Cyanidin extracted from red cabbage as a chelating agent. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 126, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2014.01.125 (2014).

Khaodee, W. et al. Simple detection kit for copper(II) ion in water using solid sorbent modified with cyaniding extract from red cabbage. Naresuan Univ. J. Sci. Technol. 29 (3). https://doi.org/10.14456/nujst.2021.30 (2021).

Ghosh, A. & Saha, P. D. Optimization of copper bioremediation by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia PD2. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 1, 159–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2013.04.012 (2013).

Heidari, P., Mazloomi, F. & Sanaeizade, S. Optimization study of nickel and copper bioremediation by Microbacterium oxydans strains CM3 and CM7. Soil. Sediment. Contam. Int. J. https://doi.org/10.1080/15320383.2020.1738335 (2020).

Ting, Y. G. et al. Biosorption of copper(II) from aqueous solution by Bacillus subtilis cells immobilized into Chitosan beads. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 23, 1804–1814. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1003-6326(13)62664-3 (2013).

Zeng, W. et al. Role of extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) in toxicity response of soil bacteria Bacillus sp. S3 to multiple heavy metals. Bioproc Biosyst Eng. 43, 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00449-019-02213-7 (2020).

Lin, H., Wang, C., Zhao, H., Chen, G. & Chen, X. A subcellular-level study of copper speciation reveals the synergistic mechanism of microbial cells and EPS involved in copper binding in bacterial biofilms. Environ. Pollut. 263, 114485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114485 (2020).

Diep, P., Mahadevan, R. & Yakunin, A. F. Heavy metal removal by bioaccumulation using genetically engineered microorganisms. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 6, 157. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2018.001 (2018).

Nandiyanto, A., Ragadhita, R., Fiandini, M. & Ijost, I. Interpretation of fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR): A practical approach in the polymer/plastic thermal decomposition. Indones J. Sci. Technol. 8 (1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijost.v8i1.53297 (2023).

Flemming, H. C. et al. Microbial extracellular polymeric substances in the environment, technology, and medicine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 23, 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-024-01098-y (2025).

Gupta, P. & Diwan, B. Bacterial exopolysaccharide-mediated heavy metal removal: A review on biosynthesis, mechanism, and remediation strategies. Biotechnol. Rep. 13, 58–71 (2017).

FTIR functional group database table with search - InstaNANO. https://instanano.com/all/characterization/ftir/ftir-functional-group%20search/ (2025). accessed April 25th.

Zhang, J., Yang, K., Wang, H., Lv, B. & Ma, F. Biosorption of copper and nickel ions using Pseudomonas sp. in single and binary metal systems. Desalin. Water Treat. 57, 2799–2808. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2014.983177 (2014).

Kumar, V. & Dwivedi, S. K. Bioremediation mechanism and potential of copper by actively growing fungus Trichoderma lixii CR700 isolated from electroplating wastewater. J. Environ. Manage. 277, 111370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111370 (2021).

Liu, Y., Wang, H., Cui, Y. & Chen, N. Removal of copper ions from wastewater: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20 (5), 3885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053885 (2023).

Oladimeji, T. E. et al. Review on the impact of heavy metals from industrial wastewater effluent and removal technologies. Heliyon 10 (23), e40370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e40370 (2024).

Saez-Zamacona, I., Grindlay, G. & Martínez-Espinosa, R. M. Evaluation of Haloferax mediterranei strain R4 capabilities for cadmium removal from Brines. Mar. Drugs. 21 (2), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/md21020072 (2023).

Völkel, S., Fröls, S. & Pfeifer, F. Heavy metal ion stress on Halobacterium salinarum R1 planktonic cells and biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 9, 3157. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.03157 (2018).

Hegazy, G. E., Soliman, N. A., Ossman, M. E. & Elshafei, M. M. Isotherm and kinetic studies of cadmium biosorption and its adsorption behaviour in multi-metals solution using dead and immobilized archaeal cells. Sci. Rep. 13, 2550. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29456-5 (2023).

Tavoosi, N., Sepahi, A. & Kiarostami, A. V., & others. Arsenite tolerance and removal potential of the indigenous halophilic bacterium, Halomonas elongata SEK2. Biometals. 37, 1393–1409. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-024-00612-2

Straková, D., Sánchez-Porro, C., de la Haba, R. R. & Ventosa, A. Decoding the genomic profile of the halomicroarcula genus: comparative analysis and characterization of two novel species. Microorganisms 12 (2), 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12020334 (2024).

Ben Hamad Bouhameda, S., Chaari, M., Baati, H., Zouari, S. & Ammar, E. Extreme halophilic archaea: Halobacterium salinarum carotenoids characterization and antioxidant properties. Heliyon 10 (17), e36832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e36832 (2024).

Yoon, S. H. et al. Introducing ezbiocloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67, 1613–1617. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.001755 (2017).

Parmar, P., Shukla, A., Goswami, D., Patel, B. & Saraf, M. Optimization of cadmium and lead biosorption onto marine Vibrio alginolyticus PBR1 employing a Box-Behnken design. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 4, 100043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceja.2020.100043 (2020).

Owolabi, R. U., Usman, M. A. & Kehinde, A. J. Modelling and optimization of process variables for the solution polymerization of styrene using response surface methodology. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 30, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksues.2015.12.005 (2018).

Minabi-Nezhad, M., Moeinpour, F. & Mohseni-Shahri, F. S. Development of a green metallochromic indicator for selective and visual detection of copper(II) ions. Sci. Rep. 13, 12501. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39556-x (2023).

Standard methods committee of the american public health association american water works association, & water environment federation. (Year). 3120 Metals by plasma emission spectroscopy. In Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (eds Lipps, W. C. et al.) (APHA, ). https://doi.org/10.2105/SMWW.2882.047.

Kumar, V. & Dwivedi, S. K. Mycoremediation of heavy metals: processes, mechanisms, and affecting factors. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 10375–10412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11491-8 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank Shubham Pandey, Bhavna Parmar, and Anjali Gupta for their helpful feedback on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. M.A. supervised the work and developed the idea. F.G. performed the experiments and F.G., A.S, M.A., and S.A.S.F. analyzed and interpreted the data. F.G., A.S. and M.A. discussed the paper and F.G. and A.S. drafted the manuscript and R.K. edited the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghasemi, F., Safarpour, A., Shahzadeh Fazeli, S.A. et al. Optimization of copper bioremoval from hypersaline environments by the halophilic archaeon Halalkalicoccus sp. Dap5 via response surface methodology. Sci Rep 15, 31656 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17576-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17576-z