Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated that cathepsin B is up-regulated in the myocardium of both mice and humans with pathological cardiac hypertrophy. However, it remains unknown whether cathepsin B is detectable in human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) and whether its expression is associated with pathological hypertrophy. In this study, immunofluorescence staining confirmed the presence of cathepsin B in human PBLs. Western blotting analysis and correlation studies further revealed a positive correlation between cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs and that in cardiac tissues (r = 0.441, p = 0.017). We also investigated the association between cathepsin B expression level in PBLs and cardiac structure and function. Quantitative PCR and western blotting analyses indicated that patients with left ventricular hypertrophy, particularly those with eccentric hypertrophy, exhibited significantly elevated cathepsin B expression in PBLs (p < 0.001). Logistic regression analysis identified cathepsin B as an independent risk factor for left ventricular hypertrophy (odds ratio = 4.863, 95% confidence interval: 1.341–17.632). Receiver operating characteristic analysis further supported its diagnostic value (area under the curve = 0.748, p = 0.001). In summary, cathepsin B levels in PBLs positively correlates with myocardial levels and may serve as a peripheral biomarker for diagnosing maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pathological cardiac hypertrophy is typically a precursor to heart failure and is characterized by an increase in cardiomyocyte size and thickening of the ventricular wall in response to increased workload or cardiac insult1,2. Although this hypertrophic response is initially adaptive and compensatory, prolonged exposure to stress can result in ventricular dilation, cardiac dysfunction, and ultimately heart failure3,4. Despite significant progress has been made in elucidating the underlying mechanisms of pathological cardiac hypertrophy, effective measures for assessing the progression of myocardial hypertrophy remain limited5,6.

Cathepsin B is a lysosomal cysteine protease that was originally synthesized as a precursor form in the endoplasmic reticulum and contains a signal peptide and a propeptide. The signal peptide guides the precursor into the endoplasmic reticulum cavity and is excised to form enzymegen. Enzymogen is modified in the Golgi apparatus and transported to lysosomes via the M6P receptor-mediated pathway. In the acidic environment of lysosomes, the propeptide is excised, generating a mature single-chain form (~ 30 kDa). In some cases, the single-chain can be further hydrolyzed into double-stranded forms (a light chain ~ 5–7 kDa and a heavy chain ~ 20–25 kDa, linked by disulfide bonds)7. Both the mature single-chain and double-chain forms have complete catalytic domains, and the active sites of the double-chain are fully exposed, so it have higher enzymatic activity than the single-chain8. Mature single-chain form is mainly localized in lysosomes, and a few can be secreted extracellularly to promote extracellular matrix remodeling9. Double-chain form is strictly localized in the lysosome, involved in physiological processes such as antigen presentation and autophagy-lysosomal degradation. Under pathological conditions, when the lysosomal membrane is damaged, it will infiltrate the cytoplasm and trigger cell apoptosis10.

Recent studies have highlighted the role of dysregulated cathepsin B, in the development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy11,12,13,14,15. Studies using murine models have shown that both the expression and activity of cathepsin B are elevated in hypertrophic myocardial tissue induced by angiotensin II and pressure overload. Moreover, cathepsin B knockout has been shown to attenuate pathological hypertrophy7,16,17,18. Elevated cathepsin B expression has also been observed in the myocardium of patients with dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy19,20. Our previous work demonstrated a significant correlation between calcineurin expression in human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) and that in myocardial tissue in patients with valvular atrial fibrillation or heart failure21,22. Although upregulation of cathepsin B in myocardial tissue is well-documented in both animal models and human cardiac hypertrophy, its expression in PBLs and its clinical significance have not yet been investigated. In this study, we aimed to investigate the association between cathepsin B expression in PBLs and pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

Results

Expression of cathepsin B in human PBLs

Immunofluorescence staining confirmed the localization of cathepsin B in PBLs (Fig. 1A). The protein levels of cathepsin B in PBLs and left atrial appendage tissues from 30 patients were assessed using western blotting analysis. As illustrated in Fig. 1B, The protein bands of cathepsin B in myocardial tissues were mainly distributed at the 25 kDa level, and the majority of cathepsin B protein in PBLs was presented at the 30 kDa level. Thus, we speculate that the cathepsin B in myocardial tissues mostly exist in double-chain form, while the protein in PBLs mainly exist in mature single-chain form. Furthermore, the correlation between cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs and those in myocardial tissue was analyzed, and a significant positive correlation was observed between them (r = 0.441, p = 0.017). Therefore, the expression of cathepsin B in PBLs may reflect its levels in myocardial tissue to a certain extent.

Expression of cathepsin B (CTSB) in human PBLs. (A) Immunofluorescence staining deteced the cathepsin B expression in human PBLs. No-primary control refers to the condition without primary antibody incubation. Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) Cathepsin B protein expession in both PBLs and in left atrial appendage tissues from 30 patients were assessed using western blotting analysis. Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Cathepsin B protein levels were calculated by the ratio of the gray value of its protein band to the gray value of tubulin. Spearman correlation was used to analyze the correlation between the protein levels of cathepsin B in PBLs and that in myocardial tissues. The shaded area represent 95% confidence bands.

Comparison of the baseline data of the subjects

As summarized in Table 1, significant differences were noted between the non-left ventricular hypertrophy (non-LVH) and LVH groups in terms of age, body mass index (BMI), NT-proBNP, serum creatinine, and histories of hypertension and atrial fibrillation. Specifically, the LVH group exhibited higher NT-proBNP and serum creatinine levels, as well as a longer history of hypertension compared to the non-LVH group. Furthermore, echocardiographic parameters, including left atrial diameter (LAD), left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (LVDD), interventricular septal thickness (IVST), and left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPWT), were significantly higher in the LVH group than in the non-LVH group (p < 0.001), whereas the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was significantly lower (p < 0.001). Additionally, age, BMI, NT-proBNP, serum creatinine, history of atrial fibrillation, and echocardiographic indices showed statistically significant differences among groups with varying left ventricular geometrical configuration groups (see Supplementary Table 1). Other indicators did not differ significantly.

Comparison of cathepsin B expression in PBLs among different groups

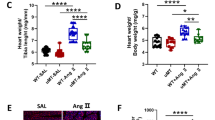

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and western blotting analyses were conducted to compare cathepsin B expression in PBLs across different groups. As shown in Fig. 2A, the qPCR results indicated that cathepsin B mRNA levels in PBLs were significantly higher in the LVH group than in the non-LVH group (p = 0.027). Similarly, western blotting analysis demonstrated a marked increase in cathepsin B protein levels in the LVH group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). Subgroup analysis based on left ventricular geometry revealed that both mRNA and protein levels of cathepsin B in PBLs were significantly elevated in the eccentric hypertrophy (EH) group compared to the normal geometry (NG), centripetal remodeling (CR), and centripetal hypertrophy (CH) groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2C-D). Notably, no significant differences were observed between the CR and CH groups compared to the NG group. In summary, cathepsin B expression in PBLs was significantly upregulated in patients with LVH, particularly in those with EH.

Comparison of the expression of cathepsin B in PBLs. (A) The qPCR analysis of cathepsin B mRNA levels in PBLs among the non-LVH (n = 60) and LVH (n = 30) groups. (B)Western blotting analysis was used to detected the cathepsin B protein levels among the non-LVH (n = 61) and LVH (n = 28) groups. Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. (C) The qPCR detected cathepsin B mRNA levels in PBLs of the NG (n = 27), CR (27), CH (n = 16), and EH (n = 13) groups. (D) The cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs of the NG (n = 39), CR (22), CH (n = 11), and EH (n = 17) groups. Annotation: CTSB, cathepsin B; NG, normal geometry; CR, centripetal remodeling; CH, centripetal hypertrophy; EH, eccentric hypertrophy; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01,***p < 0.001.

Diagnostic efficiency of cathepsin B in PBLs for LVH

Binary logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify factors influencing LVH. Cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs and other clinical indices showing significant differences (p < 0.05) were included in the univariate logistic regression analysis. Variables with statistical significance (p < 0.05) were subsequently included in a multivariate logistic regression model to control potential confounders. As shown in Table 2, the results indicated that age, BMI, NT-proBNP, serum creatinine, and history of hypertension were significant factors for LVH (p < 0.05). Furthermore, cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs was identified as an independent risk factor for LVH (p = 0.016, B = 1.582, odds ratio [OR] = 4.863, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.341–17.632). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to evaluate the diagnostic performance of cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs for LVH. As shown in Fig. 3, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.748 (p = 0.001, 95% CI: 0.616–0.881), indicating moderate diagnostic efficacy. Furthermore, a polynomial logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors influencing the progression of left ventricular geometry. Variables included cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs and other clinical indices that showed significant differences in baseline data (p < 0.05). As shown in Supplementary Table 2, cathepsin B protein levels significantly influenced the development of left ventricular configuration (p = 0.002, B = 1.665, OR = 5.258, 95% CI: 1.831–15.253).

Correlation analysis between the cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs and clinical indicators

Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the relationship between cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs and various clinical indicators. As illustrated in Fig. 4, cathepsin B protein levels were significantly associated with several echocardiographic parameters, including LAD (r = 0.392, p < 0.001), LVDD (r = 0.320, p = 0.002), IVST (r = 0.250, p = 0.018), LVPWT (r = 0.258, p = 0.014), left ventricular mass index (LVMI) (r = 0.384, p < 0.001), and LVEF (r = −0.442, p < 0.001). Additionally, cathepsin B protein levels were positively correlated with NT-proBNP (r = 0.403, p = 0.002) and serum creatinine (r = 0.241, p = 0.024). In summary, cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs showed strong correlations with both cardiac and renal function indicators.

Spearman correlation analysis between the cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs and clinical indicators. The protein levels of cathepsin B in PBLs was measured by western blotting analysis. The shaded area represent 95% confidence bands. Annotation: CTSB, cathepsin B; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; IVST, interventricular septal thickness; LVPWT, left ventricular posterior wall thickness; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that cathepsin B expression in PBLs positively correlates with its expression in the myocardial tissue and is up-regulated in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), particularly in those with eccentric hypertrophy. Cathepsin B in PBLs may serve as a potential biomarker for diagnosing maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy.

Pathological cardiac hypertrophy can contribute to heart failure, and both conditions are ultimately life-threatening. The compensatory stage of cardiac hypertrophy is typically characterized by LVH and ventricular wall thickening, whereas the decompensated stage involves ventricular dilation and impaired cardiac function23. The transition from adaptive to maladaptive remodeling is accompanied by various changes in cardiomyocytes, including apoptosis, electrophysiological alterations, metabolic shifts, maladaptive gene expression, excessive autophagy, and fibrosis6,23. Therefore, identifying clinically relevant mediators of maladaptive remodeling is essential for improving outcomes in patients with pathological hypertrophy and heart failure.

Cathepsin B, a lysosomal cysteine protease, plays a vital role in numerous physiological processes beyond its proteolytic function in lysosomes, such as extracellular matrix degradation, innate immunity, and programmed cell death24,25,26,27,28,29. An increasing number of studies have highlighted the involvement of cathepsin B in cardiovascular pathologies, including hypertension, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathies, and heart failure30. Upregulation of myocardial cathepsin B has been observed in both murine models of myocardial hypertrophy and in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy16,17,18,19,20,31. However, it remains unknown whether cathepsin B is expressed in PBLs, and if so, whether it could serve as a peripheral biomarker for pathological cardiac hypertrophy. This study aimed to address these questions.

Immunofluorescence staining confirmed the presence of cathepsin B in human PBLs. Western blotting was performed to detect the cathepsin B protein levels in myocardial tissues and PBLs. Interestingly, the results indicated that cathepsin B in myocardial tissues may be predominantly in double-chain form, whereas in PBLs, the protein might mainly be in mature single-chain form. The reason for this difference in expression might be related to different functional requirements of myocardial tissue and PBLs, as well as tissue-specific expression. Myocardial tissue has an active metabolism, continuous demand for protein turnover, and is rich in lysosomes. The low pH environment and cathepsin D in lysosomes can cleave single-chain cathepsin B into more active double-chain form32. However, the lysosomal system in lymphocytes may not be as developed as that in myocardial cells, resulting in insufficient cleavage of single-chain cathepsin B. Additionally, lymphocytes may regulate the activation state of cathepsin B to avoid excessive inflammatory responses33. We further found that its expression in PBLs was positively correlated with its expression in myocardial tissue, suggesting that cathepsin B levels in PBLs may reflect the expression levels in myocardium.

Furthermore, we assessed the association between cathepsin B expression in PBLs and cardiac structure and function. The results showed significantly elevated cathepsin B levels in PBLs of patients with LVH, particularly in those with eccentric hypertrophy, an established manifestations of decompensated cardiac hypertrophy. These results suggested that cathepsin B expression in PBLs is associated with maladaptive hypertrophy. Increasing evidence suggests that cardiomyocyte death plays a role in the transition from compensatory to decompensated remodeling. This includes forms of cell death such as apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy, and pyroptosis34,35. Cathepsin B has been implicated in multiple forms of programmed cell death, including apoptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, necroptosis, and autophagic cell death36. We therefore hypothesized that cathepsin B may contribute to the development of decompensated hypertrophy by promoting cardiomyocyte death. Future research is warranted to investigate this hypothesis.

Binary logistic regression and ROC curve analyses indicated that the protein level of cathepsin B in PBLs has diagnostic value for LVH. Our data indicated that a history of hypertension was not an independent risk factor for LVH, potentially due to adherence to anti-hypertensive therapy mitigating its effects on cardiac hypertrophy. Furthermore, multinomial logistic regression analysis identified cathepsin B protein levels as an independent factor influencing the progression of left ventricular geometry, further validating the role of cathepsin B in the pathogenesis of pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

Additionally, we analyzed the correlation between cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs and other clinical indicators. Significant positive correlations were observed with cardiac structure and function parameters such as left atrial diameter (LAD), left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (LVDD), interventricular septal thickness (IVST), left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPWT), left ventricular mass index (LVMI), and NT-proBNP. A significant negative correlation was observed with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Collectively, these findings suggest that cathepsin B in PBLs has potential as both a peripheral biomarker for diagnosing maladaptive myocardial hypertrophy and an indicator of cardiac function.

Moreover, cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs positively correlated with serum creatinine levels. Previous studies have shown that cathepsin B is involved in renal remodeling in patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease37,38, and serum cathepsin B levels have been associated with age-related decline in renal function in the general population37. In our study, patients with overt renal insufficiency were excluded; therefore, elevated cathepsin B in PBLs may reflect subclinical renal dysfunction.

This study has several limitations. The patient samples were obtained from a single center, which may introduce selection bias. Due to the difficulty in obtaining ventricular tissue, only the left atrial appendage samples were collected, potentially introducing additional bias. Moreover, while we observed a correlation between cathepsin B levels in PBLs and pathological cardiac hypertrophy, causality has yet to be established and warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate that cathepsin B in PBLs may serve as a non-invasive biomarker for diagnosing maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy, offering valuable insights into disease progression and potential therapeutic monitoring. Further multi-center studies and mechanistic investigations are needed to validate and expand upon these findings.

Methods

Subjects and samples

A total of 225 hospitalized patients (68.5 ± 0.86 years, 63% male) were enrolled, with a mean Body Mass Index (BMI) of 24.89 ± 0.25 kg/m². Among them, there were 30 patients who underwent heart valve surgery, their left atrial appendage tissue and preoperative venous blood were obtained. The remaining 195 patients were from the department of cardiology, their peripheral venous blood was collected. Inclusion criteria: the patients with hypertension, ischemic cardiomyopathy, or valvular heart disease, who were hospitalized in the Department of Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery of Shandong Provincial Hospital, and aged ≥ 18 years and signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria: the patients combined with acute heart failure, viral myocarditis, autoimmune diseases, malignant tumors, acute and chronic infections, severe liver and kidney insufficiency.

The study was discussed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital. We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Echocardiography

All the enrolled patients underwent color Doppler echocardiography in the cardiac ultrasound laboratory of our hospital, and the indicators of measurement were as follows: aod aortic dimension (AOD), right atrial diameter (RAD), right ventricular dimension (RVD), left atrial diameter (LAD), left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (LVDD), interventricular septal thickness (IVST), left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPWT), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The body surface area (BSA), left ventricular mass (LVM), left ventricular mass index (LVMI) and left ventricular relative wall thickness (LVRWT) were calculated separately according to the following equations39.

\(BSA\,=\,0.0061 \times H\left( {cm} \right)\,+\,0.0128 \times W\left( {kg} \right) - 0.1529\)

(H is the height of the patient, and W is the weight of the patient.)

\(LVM = 0.8 \times 1.04 \times [(LVEDD{+}IVST{+}LVPWT)^{3} - LVEDD^{3} ]{+}0.6\)

\(LVMI\,=\,LVM/BSA\)

\(LVRWT=(2 \times LVPWT)/LVEDD\)

LVH was defined as LVMI greater than 115 g/m2 in men or 95 g/m2 in women.

Grouping

The enrolled patients were divided into the LVH and non-LVH groups based on LVMI. According to LVMI and LVRWT (Table 3), the patients were classified into four groups: the normal geometry (NG), centripetal remodeling (CR), centripetal hypertrophy (CH), and eccentric hypertrophy (EH)40.

Extraction of human peripheral blood lymphocytes

5 ml venous blood was collected from the enrolled patient and placed in the EDTA anticoagulant tube for the extraction of peripheral blood lymphocytes. The whole blood was diluted with 5 ml PBS buffer, and 5 ml of the Human Lymphocyte Separation Medium (Cat. No. P8900, Solarbio) was added to the centrifuge tube, then the diluted whole blood was slowly and gently transferred and flattened above the liquid level of the separation solution, centrifuged at 1000×g for 30 min at room temperature (RT). After centrifugation, there is a distinct stratification: the top layer is the diluted plasma, the middle layer is the separation medium, the white film layer between the plasma and the separation medium is the lymphocytes layer, and the bottom layer is the red blood cells and granulocytes. The white film layer was carefully aspirated into a centrifuge tube containing 10 ml PBS buffer and then centrifuged at 250×g for 10 min at RT. Subsequently, the cell precipitate was washed again. The lymphocytes were retained for subsequent operations.

Immunofluorescence staining

Collected peripheral blood lymphocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and subsequently washed three times with PBS. Cells were resuspended with PBS buffer, and 50ul of the cell suspension was dropped onto poly-L-lysine coated slide (Cat. No. YA0170, Solarbio) and dried naturally at RT. Then, they were permeated with 0.4% Triton X-100 (Cat. No. P0096, Beyotime) for 30 min and blocked in 2% BSA (Cat. No. ST2249, Beyotime) for 1 h at RT. Cell samples was incubated overnight with anti-cathepsin B (1:300) (Cat. No. 12216-1-AP, Proteintch) at 4℃. The no-primary control group was incubated overnight by 2% BSA at 4℃. After washed with PBS for three times, the cells were incubated with CoraLite594-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at RT. The cell nuclei were stained with DAPI for 10 min at RT. Images were acquired using a positive fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS BX63).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA from PBLs were isolated using RNA isolater Total RNA (Cat. No. R711-01, Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The cDNA was prepared using the HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+ gDNA wiper) (Cat. No. R323-01, Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The primer sequences used for qPCR are listed in Table 4. The PCR was carried out with cDNA using SYBR Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit (Cat. No. AG11718, Accurate Biotechnology, Co., Ltd). The amplification procedure was 30 s at 95℃, then followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95℃ and 30 s at 60℃. Thermal cycling and fluorescence detection were performed by QuantStudioTM 12 K Flex. The level of cathepsin B was normalized to GAPDH. The relative mRNA expression of cathepsin B were calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method.

Western blotting analysis

The human PBLs and myocardial tissue were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer (Cat. No. P0013B, Beyotime) and phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride (Cat. No. ST506, Beyotime). Then, the cell lysate was centrifuged at 12,000×g for 15 min at 4℃and the supernatant was retained. The protein concentration was quantified by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Cat. No. P0012, Beyotime). Protein samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE gel (Cat. No. PG112, Epizyme), and then transferred to PVDF membranes (Cat. No. IPVH00010, Millipore). The PVDF membranes were blocked by 5% skim milk for 1 h at RT and subsequently incubated with specific primary antibodies for 10–15 h at 4℃. The primary antibodies were used as follows: anti-cathepsin B (1:2500) (Cat. No. 12216-1-AP, Proteintch) and anti-Alpha Tubulin (1:5000) (Cat. No. 11224-1-AP, Proteintch). After that, the membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline containing 1% Tween-20 (TBST) for three times, and then incubated with secondary antibody (1:10000) (Cat. No. PR30011, Proteintch) for 1 h at RT. Subsequently, the membranes were washed with TBST for three times. Western blotting results were detected with chemiluminescent analyzer (ProteinSimple, USA) and immunoblot intensities were analyzed with ImageJ v1.8.0.112 software (National Institutes of Health). Cathepsin B protein levels were calculated by the ratio of the gray value of its protein band to the gray value of tubulin.

Statistical analysis

The IBM SPSS Statistics 25 was used for statistical analysis. Measurement data with normal distribution were represented as mean ± standard deviation (\(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\) ±ན), and the comparison among two groups was analyzed using the unpaired t test and four groups was using one-way ANOVA; The measurement data with non-normal distribution were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR), and the comparison two groups was analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test and four groups was using Kruskal-Wallis test. The count data were presented as numbers and percentages (%), and the comparison among groups was performed using the Chi-square (χ2) test. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to identify the influencing factors of LVH. The diagnostic efficacy of cathepsin B protein levels in PBLs for LVH was evaluated by the ROC curve analysis. Two-sided test, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CTSB:

-

Cathepsin B

- PBLs:

-

Human peripheral blood lymphocytes

- LVH:

-

Left ventricular hypertrophy

- LVMI:

-

Left ventricular mass index

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- AOD:

-

Aod aortic dimension

- RAD:

-

Right atrial diameter

- RVD:

-

Right ventricular dimension

- LAD:

-

Left atrial diameter

- LVDD:

-

Left ventricular end-diastolic dimension

- IVST:

-

Interventricular septal thickness

- LVPWT:

-

Left ventricular posterior wall thickness

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- BSA:

-

Body surface area

- LVM:

-

Left ventricular mass

- LVMI:

-

Left ventricular mass index

- LVRWT:

-

Left ventricular relative wall thickness

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- QPCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RT:

-

Room temperature

- TBST:

-

Tris-buffered saline containing 1% Tween-20

- ROC:

-

The receiver operating characteristic

- CAD:

-

Coronary atherosclerotic heart disease

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- NG:

-

Normal conformation

- CR:

-

Centripetal remodelling

- CH:

-

Centripetal hypertrophy

- EH:

-

Eccentric hypertrophy

References

Goto, J. et al. HECT (Homologous to the E6-AP carboxyl Terminus)-Type ubiquitin E3 ligase ITCH attenuates cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway. Hypertension 76 (6), 1868–1878 (2020).

Đorđević, D. B., Koračević, G. P., Đorđević, A. D. & Lović, D. B. Hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. J. Hypertens. 42 (9), 1505–1515 (2024).

Schiattarella, G. G. & Hill, J. A. Inhibition of hypertrophy is a good therapeutic strategy in ventricular pressure overload. Circulation 131 (16), 1435–1447 (2015).

Braunwald, E. Heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 1 (1), 1–20 (2013).

Cluntun, A. A. et al. The pyruvate-lactate axis modulates cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Cell Metabol. 33 (3), 629–648e10 (2021).

Oldfield, C. J., Duhamel, T. A. & Dhalla, N. S. Mechanisms for the transition from physiological to pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 98 (2), 74–84 (2020).

Turk, V. et al. Cysteine cathepsins: from structure, function and regulation to new frontiers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1824 (1), 68–88 (2012).

Musil, D. et al. The refined 2.15 A X-ray crystal structure of human liver cathepsin B: the structural basis for its specificity. EMBO J. 10 (9), 2321–2330 (1991).

Zhang, Y. et al. Piezo1-Mediated mechanotransduction promotes cardiac hypertrophy by impairing calcium homeostasis to activate calpain/calcineurin signaling. Hypertens. (Dallas Tex. : 1979). 78 (3), 647–660 (2021).

Hook, V. et al. Cathepsin B in neurodegeneration of alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury, and related brain disorders. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Proteins Proteom. 1868 (8), 140428 (2020).

Sevenich, L. & Joyce, J. A. Pericellular proteolysis in cancer. Genes Dev. 28 (21), 2331–2347 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Targeting Calpain for heart failure therapy: implications from multiple murine models. JACC Basic. Translational Sci. 3 (4), 503–517 (2018).

Letavernier, E. et al. Targeting the calpain/calpastatin system as a new strategy to prevent cardiovascular remodeling in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circul. Res. 102 (6), 720–728 (2008).

Wang, F. et al. Silica nanoparticles induce pyroptosis and cardiac hypertrophy via ROS/NLRP3/Caspase-1 pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 182, 171–181 (2022).

Lutgens, S. P., Cleutjens, K. B., Daemen, M. J. & Heeneman, S. Cathepsin cysteine proteases in cardiovascular disease. FASEB Journal: Official Publication Federation Am. Soc. Experimental Biology. 21 (12), 3029–3041 (2007).

O’Toole, D. et al. Signalling pathways linking cysteine cathepsins to adverse cardiac remodelling. Cell. Signal. 76, 109770 (2020).

Wu, Q. Q. et al. Cathepsin B deficiency attenuates cardiac remodeling in response to pressure overload via TNF-α/ASK1/JNK pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 308 (9), H1143–H1154 (2015).

Liu, A., Gao, X., Zhang, Q. & Cui, L. Cathepsin B Inhibition attenuates cardiac dysfunction and remodeling following myocardial infarction by inhibiting the NLRP3 pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 16 (5), 7873 (2017).

Cheng, X. W. et al. Role for cysteine protease cathepsins in heart disease: focus on biology and mechanisms with clinical implication. Circulation 125 (12), 1551–1562 (2012).

Ge, J. et al. Enhanced myocardial cathepsin B expression in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 8 (3), 284–289 (2006).

Li, C. et al. Relationship between calcineurin - nuclear factor of activated T cells pathway and atrial fibrillation in patients with valvular heart disease. J. Shandong Univ. (Med Edition) 8, 47–51. (2014).

Wang, M. M., Zhao, Y., Liu, W., Zhang, J. & Wang, J. C. A preliminary report on the correlation between calcineurin Mrna levels in peripheral blood lymphocytes and myocardial tissue in patients with heart failure. Chin. J. Circulation. 02, 113–116 (2008).

Tham, Y. K., Bernardo, B. C., Ooi, J. Y., Weeks, K. L. & McMullen, J. R. Pathophysiology of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure: signaling pathways and novel therapeutic targets. Arch. Toxicol. 89 (9), 1401–1438 (2015).

Sloane, B. F. et al. Cathepsin B and tumor proteolysis: contribution of the tumor microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol. 15 (2), 149–157 (2005).

Chou, M. Y., Liu, D., An, J., Xu, Y. & Cyster, J. G. B cell peripheral tolerance is promoted by cathepsin B protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 120 (16), e2300099120 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Cathepsin B promotes sepsis-induced acute kidney injury through activating mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Front. Immunol. 13, 1053754 (2023).

Man, S. M. & Kanneganti, T. D. Regulation of lysosomal dynamics and autophagy by cathepsin b/cathepsin B. Autophagy 12 (12), 2504–2505 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. Cathepsin B aggravates acute pancreatitis by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome and promoting the caspase-1-induced pyroptosis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 94, 107496 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Cathepsin B aggravates coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis through activating the inflammasome and promoting pyroptosis. PLoS Pathog. 14 (1), e1006872 (2018).

Cai, Z., Xu, S. & Liu, C. Cathepsin B in cardiovascular disease: underlying mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 28 (17), e70064 (2024).

Stoka, V., Turk, V. & Turk, B. Lysosomal cathepsins and their regulation in aging and neurodegeneration. Ageing Res. Rev. 32, 22–37 (2016).

Turk, V., Turk, B. & Turk, D. Lysosomal cysteine proteases: facts and opportunities. EMBO J. 20 (17), 4629–4633 (2001).

Riaz, S. et al. Anti-hypertrophic effect of Na+/H + exchanger-1 Inhibition is mediated by reduced cathepsin B. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 888, 173420 (2020).

Diwan, A. & Dorn, G. W. 2 Decompensation of cardiac hypertrophy: cellular mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Physiol. (Bethesda). 22, 56–64 (2007).

Lan, C. et al. SerpinB1 targeting safeguards against pathological cardiac hypertrophy and remodelling by suppressing cardiomyocyte pyroptosis and inflammation initiation. Cardiovasc. Res. 121 (1), 113–127 (2025).

Xie, Z. et al. Cathepsin B in programmed cell death machinery: mechanisms of execution and regulatory pathways. Cell. Death Dis. 14 (4), 255 (2023).

Musante, L. et al. Proteases and protease inhibitors of urinary extracellular vesicles in diabetic nephropathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 289734 (2015).

Wang, N. et al. The association of serum cathepsin B concentration with age-related cardiovascular-renal subclinical state in a healthy Chinese population. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 65, 146–155 (2016).

Chen, S. C. et al. Body mass index, left ventricular mass index and cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Med. Sci. 351 (1), 91–96 (2016).

Mancia, G. et al. 2023 ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European society of hypertension: endorsed by the international society of hypertension (ISH) and the European renal association (ERA). J. Hypertens. 41 (12), 1874–2071 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients who agreed to provide samples for this study. We are extremely grateful to the relative clinicians, nurses in Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University for their contributions during the sample collection process. We also would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China [grant number 2020YFC2008900].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DF: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, and Writing-original draft; DF, CL, WG, SZ, YW, and GZ: Sample selection; DF, YS, YD and JW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, and Writing-review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University. Written informed consent was also obtained from the patient for the acquisition of blood and left atrial appendage specimens.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, D., Li, C., Gao, W. et al. Cathepsin B in human peripheral blood lymphocytes as a peripheral biomarker for cardiac hypertrophy. Sci Rep 15, 32980 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17641-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17641-7