Abstract

Mycotoxin contamination in poultry feed continues to pose significant challenges for animal health, food safety, and overall public health. In this study, we investigated the antifungal and antitoxigenic activities of hydro-alcoholic extracts and crude essential oils from Clove (Syzygium aromaticum), Cinnamon bark (Cinnamomum verum), Ginger (Zingiber officinale), Neem (Azadirachta indica), and Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum). These plant-derived substances were evaluated both with and without the addition of kaolin clay, targeting major mycotoxins such as Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), Ochratoxin A (OTA), and Fumonisin B1 (FB1) levels (Table 3). Our antifungal assays focused on Aspergillus flavus, A. niger, and Fusarium proliferatum. Among the tested agents, clove and cinnamon oils demonstrated the strongest antifungal properties, with clove oil providing consistent inhibition across all fungal species. Neem extracts exhibited moderate efficacy, particularly in lowering AFB1 concentrations. Notably, the incorporation of kaolin clay (1 mg/g feed) enhanced FB1 detoxification, especially when combined with ginger or clove oils. In contrast, fenugreek-derived products showed minimal antifungal or antitoxigenic effectiveness. These findings highlight the potential of certain plant-based products—namely clove, cinnamon, and neem—used in conjunction with kaolin clay as sustainable alternatives to synthetic chemicals for controlling mycotoxin contamination in poultry feed. Further research is recommended to optimize dosage and application strategies to maximize their efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mycotoxins, which are toxic secondary metabolites predominantly produced by filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Fusarium, present a persistent challenge in agriculture, contaminating a wide array of commodities including cereals, grains, and animal feeds. In poultry production, the most frequently encountered mycotoxins are aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), ochratoxin A (OTA), and fumonisin B1 (FB1). These compounds are well-established for their deleterious effects on poultry health, encompassing immunosuppression, hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and reduced productive performance. Additionally, mycotoxins can be transmitted to humans indirectly through residues in meat and eggs, thereby posing significant public health concerns1,2. Consequently, effective mitigation of mycotoxin contamination in feed is critical both for animal health and food safety.

Conventional approaches to mycotoxin decontamination have included physical, chemical, and biological methods. However, chemical interventions often raise issues regarding safety, environmental impact, and the persistence of chemical residues in animal-derived products. These limitations have catalyzed increased interest in plant-based alternatives. Several studies have documented that essential oils and plant extracts possess both antifungal and mycotoxin-reducing activities3,4,5,6,7,8and are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) for use in food and feed applications.

A range of botanical species, notably clove (Syzygium aromaticum), cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum), neem (Azadirachta indica), ginger (Zingiber officinale), and fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum), have been examined for their antimicrobial properties. Principal bioactive components—such as eugenol, cinnamaldehyde, azadirachtin, and gingerol—demonstrate inhibitory effects on fungal proliferation and mycotoxin biosynthesis9,10,11. In parallel, the application of adsorbent materials such as kaolin clay has been shown to limit mycotoxin bioavailability by binding these toxins within the gastrointestinal tract, thereby reducing systemic absorption12,13. In this study, the evaluation of kaolin clay is limited to in vitro assays, serving as a preliminary assessment of its adsorptive potential when used alone or in combination with plant-derived agents. We acknowledge that in vitro findings do not replicate in vivo efficacy, and further animal studies are necessary to validate the practical effectiveness of kaolin as a feed additive for mycotoxin risk reduction.

Despite encouraging findings in the literature, comprehensive comparative assessments between hydro-alcoholic plant extracts and crude essential oils, especially in combination with kaolin clay, remain limited. Furthermore, systematic data evaluating the efficacy of different concentrations of such treatments against diverse mycotoxigenic fungi and their toxins under feed-relevant conditions are scarce.

This study addresses these knowledge gaps by investigating the antifungal and antitoxigenic effects of selected plant extracts and essential oils—both individually and in combination with kaolin clay—against Aspergillus flavus, A. niger, and Fusarium proliferatum. The principal objective is to determine their potential in reducing contamination by AFB1, OTA, and FB1 in poultry feed. The broader aim is to identify natural, effective, and sustainable interventions for mycotoxin control, with the potential to support the development of biocontrol-based feed additives. Such approaches may reduce reliance on synthetic fungicides, enhance food safety, and improve animal health, particularly in regions characterized by arid and semi-arid climates. The findings of this study are intended to inform the development of safer, plant-based feed management strategies with implications for both animal productivity and public health.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and preparation

Six medicinal plants—clove (Syzygium aromaticum), cinnamon bark (Cinnamomum verum), ginger (Zingiber officinale), neem (Azadirachta indica), fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum), and parsley (Petroselinum crispum)—were selected for their documented antifungal properties. Fresh samples, including leaves, seeds, bark, and rhizomes as appropriate, were sourced from local markets in Saudi Arabia. The plant materials were washed thoroughly with distilled water, air-dried at ambient temperature, and then finely ground using a laboratory mill.

Preparation of plant hydro-alcoholic extracts

Hydro-alcoholic extracts were prepared based on established protocols14,15. Briefly, 20 g of powdered plant material was soaked in 100 mL of a 50% (v/v) hydro-alcoholic solution with hexane for 72 h, with stirring every 24 h using a sterile glass rod. Additionally, a parallel extraction was conducted by macerating 100 g of powdered material in 1 L of 70% (v/v) ethanol for 72 h with periodic agitation. Upon completion, extracts were filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper (Whatman, England). The resulting filtrates were concentrated under reduced pressure at 30 °C using a rotary evaporator to yield semi-solid residues.

Two hydro-alcoholic extraction protocols were included to compare extraction efficiency and maximize the recovery of both polar and non-polar metabolites. The first method (with hexane) facilitated removal of lipophilic impurities prior to ethanol-based extraction, while the direct maceration in 70% ethanol was designed to extract a broader spectrum of bioactive constituents. The parallel use of both methods allowed us to assess which extract demonstrated stronger antifungal and antitoxigenic effects. These extracts were subsequently used to prepare solutions of varying concentrations for further experiments.

Extraction of plant essential oils

Essential oils were extracted from 20 g of powdered plant material using petroleum ether in a Soxhlet extraction apparatus (Büchi E-812), according to the method described by Devi16 with modifications based on Carvatho et al.17. The modifications as follows: the extraction time was extended from 4 to 6 h, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure rather than by atmospheric distillation, to better preserve volatile compounds. These modifications aimed to increase oil yield and minimize the loss of active phytochemicals.

After extraction, the solvent was removed by distillation, and residual solvent was evaporated by oven-drying at 58 ± 2 °C until a stable semi-solid residue was obtained. The extracted oils were weighed, and the yield of each extract was calculated as the dry weight of extract obtained after evaporation divided by the initial dry weight of plant material used, expressed as a percentage. Average yields were as follows: clove, 11.5%; cinnamon, 1.2%; neem, 4.0%; ginger, 3.0%; fenugreek, 2.0%; parsley, 1.0%. The oils were stored at 4 °C until analysis18.

In vitro determination of antifungal activity

The fungal strains employed in this study Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium proliferatum were isolated as environmental strains from poultry feed samples collected in Saudi Arabia. These isolates were previously described and molecularly characterized in published research, ensuring their relevance to feed-associated mycotoxigenic contamination24,25,26. Fusarium proliferatum was selected over F. verticillioides for this study due to its prevalence in the local poultry feed supply, its established status as a significant fumonisin B1 producer within the studied context, and the practical advantage of using locally isolated, molecularly characterized strains. This choice ensures the findings are directly relevant for managing mycotoxin risk in the specific feed materials and environmental conditions addressed by the research.

Antifungal activity was tested against three mycotoxigenic fungi: Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium proliferatum. The in vitro efficacy of crude oils and plant extracts was evaluated using the agar well diffusion method19,20,21. Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) was prepared with 200 g of potatoes, 20 g of dextrose, and 15 g of agar per liter of distilled water and adjusted to pH 5.6 ± 0.2.

Inoculum preparation

Fungal spore suspensions (~ 1 × 10⁶ spores/mL) were prepared from 7-day-old cultures on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA). Spores were harvested in sterile saline containing 0.05% Tween 80 and counted using a hemocytometer. This standardized inoculum was then used for all antifungal assays to ensure reproducibility and consistency across experiments. PDA plates (Himedia, India) were inoculated with 1 mL of fungal spore suspension (approximately 1 × 10⁶ spores/mL). After absorption of the inoculum, 6 mm wells were aseptically bored into the agar and filled with 50 µL of the respective extract or oil. Plates were incubated at 28 °C for five days, and zones of inhibition were measured to assess antifungal efficacy. All assays were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

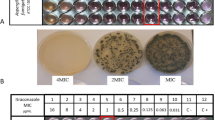

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) against mycotoxigenic fungi

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for hydro-alcoholic plant extracts and essential oils were determined using the serial agar dilution method, consistent with the protocols outlined by Fabry et al.22 and Griffin et al.23. Plant-derived preparations were incorporated into Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 10 µg/mL, with increments of 0.5 µg/mL. (SDA; 40 g dextrose, 10 g peptone, 15 g agar per liter; pH 5.6 ± 0.2) at concentrations from 0.5 to 10 µg/mL, in 0.5 µg/mL increments. The mycotoxigenic fungal strains Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium proliferatum previously isolated from poultry feed samples in Saudi Arabia24,25,26 were spot-inoculated onto the prepared agar plates. These plates were incubated at 28 °C for seven days. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration of the plant preparation that resulted in complete inhibition of visible fungal growth. Control plates, lacking plant extracts or oils, were maintained for comparison.

Antitoxigenic effects of sub-MIC concentrations of plant preparations

The effects of sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (sub-MIC) of hydro-alcoholic extracts and essential oils on mycotoxin production—specifically aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), fumonisin B1 (FB1), and ochratoxin A (OTA)—were assessed in vitro. Fungal cultures were cultivated in SMKY broth medium (composition per L: sucrose, 200 g; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5 g; KNO3, 0.3 g; yeast extract, 7.0 g; pH 5.6 ± 0.2) supplemented with sub-MIC concentrations of plant preparations27,28. For extracts exhibiting MIC activity, concentrations below the MIC were examined; for those without MIC activity, a range from 0.5 to 10 µg/mL (in 0.5 µg/mL increments) was tested. Each concentration was prepared by dissolving the appropriate amount in 0.5 mL of 5% Tween-20 and mixing with 24.5 mL of SMKY medium in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. Controls consisted of SMKY medium with 5% Tween-20 alone. Flasks were aseptically inoculated with 1 mL of fungal spore suspension (~ 10^6 spores/mL) and incubated at 27 ± 2 °C for 10 days. Post-incubation, cultures were filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and filtrates were extracted with 20 mL chloroform in a separatory funnel. The organic extracts were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate on Whatman No. 42 filter paper, evaporated to dryness at 70 °C, and analyzed for AFB1, FB1, and OTA using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described by Behiry et al.21 for AFB1, Gherbawy et al.25 for FB1, and Gherbawy et al.24 for OTA. Chromatographic separation was performed on a C18 reversed-phase column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) with the following mobile phases: methanol: water: acetonitrile (60:20:20, v/v/v) for AFB1 and OTA, and methanol:0.1 M sodium dihydrogen phosphate buffer (75:25, v/v; pH 3.3) for FB1. The flow rate was maintained at 1.0 mL/min, injection volume was 20 µL, and detection wavelengths were set to 365 nm (AFB1), 335 nm (FB1), and 333 nm (OTA). The identities and quantification of peaks were verified against external standards using consistent retention times.

Evaluation of plant extracts and oils on poultry feed with clay as adsorbent

Feed samples were autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min before inoculation with fungal spores to minimize interference by background microflora. Toxin-free poultry feed was supplemented with both MIC and sub-MIC concentrations of the plant preparations21. Treatments were prepared by dissolving the required amount of extract or oil in 5 mL of 5% Tween-20 and mixing with 20 g of feed in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. Flasks were inoculated with 1 mL of fungal spore suspension (~ 10^6 spores/mL) and incubated at 27 ± 2 °C for 10 days. Kaolin clay was included in select in vitro treatments at 1% w/w (10 mg/g feed) to preliminarily assess its ability to adsorb mycotoxins within this artificial feed matrix. It is important to note that kaolin’s principal mechanism is as a gastrointestinal adsorbent in vivo, and these in vitro experiments are not intended as a replacement for in vivo efficacy or safety assessments. The results represent a preliminary screening of binding potential and possible synergism with plant-derived materials; further validation in animal studies is recommended to establish the practical relevance of clay-based interventions. After incubation, mycotoxins were extracted from feed with 50 mL chloroform, dried, and quantified by HPLC20.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 25.0, IBM Corp., USA).

Results and discussion

Mycotoxin contamination in animal feed is a persistent risk to animal and human health29,30. Conventional chemical, physical, and biological mitigation methods present environmental and health concerns31prompting interest in natural alternatives such as plant extracts and essential oils32. Key mycotoxigenic fungi primarily Aspergillus and Fusarium cause substantial losses in storage and distribution33with Aspergillus flavus, A. niger, and Fusarium proliferatum producing major mycotoxins like aflatoxin B1, ochratoxin, and fumonisin B1, frequently found in feed.

Antifungal activity of plant extracts and essential oils

In this study, hydro-alcoholic extracts and crude essential oils from six medicinal plants—clove, cinnamon, ginger, neem, fenugreek, and parsley—were assessed for antifungal effectiveness against three mycotoxigenic fungi: Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium proliferatum. The results, detailed in Fig. 1, demonstrated that antifungal efficacy varied considerably depending on both the plant species and the type of extract examined. Among the tested samples, crude clove oil exhibited the strongest antifungal activity, producing inhibition zones ranging from 20.0 mm (against A. flavus and A. niger) up to 22.0 mm (against F. proliferatum). The hydro-alcoholic clove extract also showed notable inhibitory effects, with inhibition zones between 18.5 and 20.0 mm, highlighting its broad-spectrum antifungal potential. These findings corroborate previous research, which attributes clove’s pronounced antifungal properties largely to its high eugenol content34,35,36.

Cinnamon oil demonstrated notably strong antifungal activity, with inhibition zones ranging from 18 to 20 mm. The hydro-alcoholic extract of cinnamon also exhibited substantial antifungal effects, with inhibition zones between 17 and 18 mm. This efficacy is largely attributed to cinnamaldehyde, a key phenolic component recognized for its broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties12,37,38,39.

Neem extracts displayed moderate inhibitory effects, particularly against F. proliferatum, where inhibition zones reached 12 mm. In comparison, crude neem oil produced slightly smaller zones, ranging from 10 to 11 mm. These results align with existing literature, which credits neem’s antifungal properties primarily to azadirachtin and related limonoids40,41.

By contrast, ginger and fenugreek preparations exhibited limited antifungal efficacy. Crude ginger oil produced inhibition zones of just 7 to 10 mm. Furthermore, both the hydro-alcoholic extracts and oils derived from fenugreek and parsley were largely inactive against the tested fungal strains9,12,42.

The observed inhibition zones for clove, cinnamon, and neem in this study largely align with previous findings regarding their antifungal activity, although some variation in zone diameters is likely due to differences in extraction methods, fungal strains, or assay conditions43,44. Notably, Aspergillus flavus demonstrated the greatest susceptibility, ahead of A. niger and F. proliferatum, which highlights the potential utility of these plant extracts in managing aflatoxin-producing fungi45,46. The generally stronger antifungal effects of essential oils, as compared to hydro-alcoholic extracts, are presumably due to their higher concentrations and improved bioavailability of active phytochemicals such as eugenol and cinnamaldehyde47,48. These results support the possible application of clove, cinnamon, and neem oils as natural fungicides within food safety and agricultural frameworks. Future research should aim to isolate specific bioactive components, clarify their mechanisms of action, and assess their efficacy under field conditions in order to enable the development of effective antifungal formulations.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs)

Figure 2 provides a visual summary—a heatmap—of how various hydro-alcoholic extracts and essential oils from six medicinal plants (Clove, Cinnamon, Ginger, Neem, Fenugreek, and Parsley) perform against three mycotoxigenic fungi: Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium proliferatum. In this heatmap, lighter colors indicate lower minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), signaling greater antifungal activity, while blank (ND) cells mean there was no inhibition within the tested concentrations.

Heatmap of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs, µg/mL) of hydro-alcoholic extracts and crude essential oils from six medicinal plants against Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium proliferatum. The HEATMAP WAS GENERATED USIng GraphPad Prism, version 10.0.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA; https://www.graphpad.com/).

The data are clear: Clove and Cinnamon, especially their essential oils, exhibit the most potent antifungal effects. Clove essential oil stands out with the lowest MICs—0.5 µg/mL for A. flavus and 1.5 µg/mL for both A. niger and F. proliferatum—demonstrating strong inhibitory potential compared to the other treatments34,49. Cinnamon essential oil also displays notable activity, though its MICs are moderately higher. The hydro-alcoholic extracts are less effective: Clove extract MICs range from 4.0 to 4.5 µg/mL, while Cinnamon extract MICs fall between 7.0 and 7.5 µg/mL.

These findings emphasize that the volatile oil components, rather than the crude extracts, are primarily responsible for antifungal efficacy in these plants35,44.

Ginger, Neem, and Fenugreek essential oils demonstrated moderate to low antifungal activity, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) ranging from 6.0 to 7.0 µg/mL, as reported by 42 Prakash et al.42 and Kaur43. In contrast, their respective hydro-alcoholic extracts (GE, NE, FE) did not display measurable MICs under the conditions tested, aligning with the established understanding that essential oils typically exhibit greater antifungal potency than hydro-alcoholic extracts. This is likely due to the higher concentration of lipophilic bioactive compounds present in essential oils50,51. Parsley oils and extracts exhibited the lowest antifungal activity, often failing to inhibit fungal growth at detectable levels.

The observed differences in antifungal efficacy among various plant species and extract types can largely be attributed to variations in their phytochemical composition, particularly phenolics, terpenoids, and flavonoids. These compounds interact with fungal cell wall integrity and metabolic pathways in distinct ways. Essential oils, characterized by their richness in lipophilic constituents, are generally more effective at penetrating fungal cell membranes, resulting in higher antifungal effectiveness43.

Furthermore, the sensitivity of the tested fungal species varied. Fusarium proliferatum, for example, exhibited greater resistance as reflected by higher MIC values and a larger number of not detected (ND) entries in the results. This resistance may be linked to inherent differences in cell wall structure and metabolic defenses across fungal species52.

Mycotoxin reduction in poultry feed

The investigation centered on the effectiveness of plant-based extracts and essential oils—particularly clove and cinnamon—in mitigating mycotoxin levels in poultry feed. As shown in Fig. 3, clove and cinnamon oils significantly reduced Aflatoxin B1 levels across all tested concentrations. Experimental results demonstrated that clove oil, when applied at its minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), achieved complete (100%) elimination of the principal mycotoxins: Aflatoxin B1, Ochratoxin A, and Fumonisin B1. Cinnamon oil produced similarly high levels of reduction, with a marginally reduced effect on Fumonisin B1. The full range of mycotoxin reduction percentages across sub-MIC concentrations of clove and cinnamon preparations is detailed in Table 1.

At concentrations below MIC (Sub-MIC), clove oil retained substantial efficacy, achieving over 50% reduction at 0.25 µg/mL and exceeding 60% at 0.75 µg/mL. Cinnamon oil also displayed a clear dose-response relationship, with mycotoxin reductions surpassing 70% at 1 µg/mL. In contrast, hydro-alcoholic extracts of these spices exhibited lower, though still notable, activity. Clove extract reduced mycotoxin content by approximately 35% at 4 µg/mL, while cinnamon extract reached up to 65% reduction at 7 µg/mL. This difference is likely attributable to the higher concentrations of active antifungal compounds—such as eugenol in clove oil and cinnamaldehyde in cinnamon oil—present in the essential oils relative to the extracts.

The literature consistently supports the antifungal and mycotoxin-reducing properties of clove and cinnamon oils, citing their roles in disrupting fungal cell membranes and inhibiting aflatoxin biosynthesis. Furthermore, their natural origins and favorable safety profiles underscore their potential as environmentally friendly additives in poultry feed.

Neem oil exhibited pronounced efficacy in reducing mycotoxin levels. At minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC), reductions of approximately 77% for AFB1 and 66% for FB1 were observed, with minor variations. Notably, even at sub-MIC concentrations—particularly at or above 5 µg/mL—neem oil maintained substantial antifungal activity, achieving over 80% reduction at 6.5 µg/mL. Ginger oil demonstrated moderate effectiveness, reducing mycotoxin levels by about 60% at concentrations above 5 µg/mL (Table 2).

In contrast, hydro-alcoholic extracts of both ginger and neem resulted in lower maximum reductions. Ginger extract achieved a reduction of roughly 26%, while neem extract reached around 55% at 10 µg/mL. These findings highlight the superior antifungal potency of neem oil, attributable to its bioactive constituents such as azadirachtin. Ginger’s efficacy, while moderate, is associated with compounds like gingerol and shogaol.

Previous studies corroborate these results. Neem oil’s antifungal and antiaflatoxigenic activities have been well documented, particularly its inhibition of both fungal growth and toxin production53,54. Similarly, the antimicrobial properties of ginger oil have demonstrated activity against various mycotoxigenic fungi55. Collectively, these data suggest that neem oil is notably effective for mycotoxin management, while ginger oil offers moderate support.

Fenugreek and parsley extracts and oils

Based on the data, fenugreek and parsley extracts and oils display minimal effectiveness in reducing mycotoxin levels. Parsley preparations, regardless of type or concentration, essentially had no measurable impact. Fenugreek showed only a slight reduction—less than 10%—and only at notably high concentrations (≥ 9 µg/mL)51. These findings indicate that neither plant offers substantial antifungal or mycotoxin-inhibiting activity for use in poultry feed.

Although fenugreek is sometimes noted in the literature for antimicrobial properties, its antifungal performance—especially in the context of mycotoxin reduction—remains weak compared to other botanicals12. Parsley, for its part, tends to exert only modest antimicrobial effects, mainly targeting bacteria rather than fungi56, which is consistent with the absence of significant mycotoxin reduction observed in these experiments.

Overall implications

A comparative review of the data reveals that essential oils derived from cinnamon, clove, and neem demonstrate significant promise as natural agents for mitigating mycotoxins in poultry feed. Their marked efficacy at relatively low, sub-MIC concentrations suggests these oils could serve as practical alternatives to traditional synthetic fungicides or chemical preservatives. Although hydro-alcoholic extracts—particularly neem—were generally less potent, they may still be useful in contexts where essential oils are not feasible. On the other hand, extracts and oils from fenugreek and parsley exhibited minimal antifungal activity, making them less suitable candidates for mycotoxin control. To further advance the use of these plant-based interventions, additional research will be necessary. Key areas for future investigation include the identification of the most active compounds, optimization of product formulations, and comprehensive in vivo evaluations to determine their practical effectiveness as feed additives.

Effect of clay supplementation

This study also assessed the ability of hydro-alcoholic extracts and crude essential oils from selected medicinal plants to reduce concentrations of major mycotoxins—namely, Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), Ochratoxin A (OTA), and Fumonisin B1 (FB1)—in poultry feed. In addition, the effect of supplementing the feed with kaolin clay (at 1 mg/g) on mycotoxin reduction was examined, as detailed in Table 4. It is important to note that, while kaolin and related clay minerals are classically used as feed additives to adsorb mycotoxins within the gastrointestinal tract of animals in vivo, the present assessment is limited to an in vitro experimental setting in order to provide a preliminary screening of their adsorptive potential when combined with plant preparations. The in vitro model does not fully replicate the dynamic physiological processes of the animal digestive tract, and thus, extrapolation of these findings to in vivo efficacy should be approached with caution.

Effect of plant preparations and clay on Mycotoxin reduction

Clove and cinnamon preparations demonstrated the highest efficacy in reducing mycotoxin levels. At minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), both clove hydro-alcoholic extract and essential oil achieved complete (100%) elimination of AFB1, OTA, and FB1 in feed, regardless of the addition of clay. At sub-MIC concentrations, combining clay with clove extracts or oils resulted in a modest but consistent increase in mycotoxin reduction efficiency; for instance, clove oil at 1.0 µg/g with clay achieved a 60–63% reduction, compared to approximately 55–58% without clay.

Cinnamon bark extracts and oils exhibited similar trends. MIC-level treatments led to full toxin elimination, while sub-MIC treatments combined with clay produced slight improvements in reduction percentages. For example, AFB1 reduction using cinnamon extract increased from 52 to 54% when clay was added, suggesting a possible synergistic or additive effect of clay in adsorbing residual mycotoxins and complementing the antifungal properties of these plant compounds57,58,59.

Ginger and neem oils were also effective, achieving near-total mycotoxin reductions at MIC concentrations. At sub-MIC levels, reductions ranged from 50 to 70%, with clay supplementation enhancing efficacy by 3–7% points. Hydro-alcoholic extracts of ginger and neem showed moderate activity at sub-MICs, with reduction rates typically between 15 and 50%, which were further improved by the presence of clay60,61. In contrast, fenugreek preparations exhibited minimal activity, reducing mycotoxin levels by less than 10% even at MIC concentrations. The addition of clay did not significantly enhance fenugreek’s efficacy, consistent with its limited intrinsic antifungal activity.

Impact of clay on mycotoxin detoxification

The incorporation of kaolin clay significantly improved the detoxification of mycotoxins, with particularly notable effects on Fumonisin B1 (FB1). For example, when clay was used alongside clove or ginger oils, FB1 reduction increased from 51 to 55% and from 55 to 68%, respectively. Although clay’s impact on Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) and Ochratoxin A (OTA) was relatively modest in the presence of clove or ginger oils, its effect on FB1 detoxification was much more substantial, underscoring clay’s important, complementary function. Nonetheless, as kaolin’s known mechanism of action primarily involves binding mycotoxins within the digestive tract in vivo, the observed in vitro enhancement should be interpreted as preliminary. The results support further investigation but are not alone sufficient to substantiate gastrointestinal efficacy or safety. In vivo validation using animal feeding trials is required before recommendations regarding practical feed applications of kaolin clay can be made.

Furthermore, in treatments involving cinnamon and neem, the addition of clay resulted in enhanced reductions of both AFB1 and OTA, suggesting synergistic interactions among these components62,63,64. The likely explanation for these outcomes lies in clay’s adsorptive properties, which facilitate the sequestration of mycotoxins and thereby reduce their bioavailability in animal feed65. As illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5, the inclusion of clay with plant-derived treatments led to greater reductions in both Ochratoxin A and Fumonisin B1.

Comparative analysis and mechanisms

From a comparative standpoint, these findings align with previous research indicating that essential oils from clove, cinnamon, and neem contain bioactive compounds—such as eugenol, cinnamaldehyde, and azadirachtin—that inhibit fungal growth and suppress mycotoxin synthesis34,35. The combined application of natural antifungal agents and clay provides a dual-action strategy: biological inhibition of fungal proliferation, coupled with physical binding and removal of residual toxins.

Practical implications

In practical terms, this study demonstrates that certain plant-derived oils, notably from clove, cinnamon, and neem, are effective in reducing mycotoxin contamination in poultry feed. The addition of kaolin clay further enhances this effect, especially for fumonisin B1, which is often difficult to mitigate. However, it is important to emphasize that kaolin’s principal mechanism of action as a mycotoxin adsorbent operates in vivo, by binding toxins within the digestive tract of animals and thereby limiting their absorption. The observed effects of kaolin in this study represent preliminary results from a controlled, in vitro setting and do not fully replicate the complex physiological environment of the animal gastrointestinal tract. These results indicate the potential for integrating both natural antifungal agents and adsorbent minerals into feed formulations as environmentally sustainable alternatives to synthetic preservatives. Given their demonstrated efficacy, safety, and environmental compatibility, these combined interventions offer promising applications in poultry production, particularly in regions where climatic conditions favor fungal growth and mycotoxin contamination63,66. Nevertheless, further validation through in vivo animal studies is essential to confirm their safety, efficacy, and economic feasibility under real-world conditions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study underscores the promising potential of plant-derived antifungal agents—namely, hydro-alcoholic extracts and essential oils from clove (Syzygium aromaticum), cinnamon bark (Cinnamomum verum), neem (Azadirachta indica), and ginger—for reducing mycotoxin contamination in poultry feed. Among these, clove oil demonstrated the most pronounced antifungal and antitoxigenic effects, achieving complete inhibition of fungal growth and full reduction of key mycotoxins (Aflatoxin B1, Ochratoxin A, and Fumonisin B1) at relatively low concentrations. Both cinnamon and neem extracts also exhibited notable efficacy, with neem particularly effective against fumonisin B1. The addition of kaolin clay as an adsorbent further enhanced detoxification, especially with respect to fumonisin B1, by binding residual toxins and decreasing their bioavailability in this in vitro system. However, as clay’s principal mode of action involves adsorption within the animal gastrointestinal tract, the findings here should be regarded as preliminary. While the current in vitro results suggest synergistic or additive benefits when combining plant-derived antifungal compounds and clay, confirmation of these results in vivo—using animal feeding trials—is essential before claiming practical benefits for feed safety or animal health. This combined application of natural plant-based antifungal agents and clay offers a promising, environmentally sustainable approach to improving feed safety and mitigating the risk of mycotoxicosis in poultry production. Given the increasing emphasis on sustainable and safe feed additives, these findings support the practical use of clove, cinnamon, and neem-based formulations, with or without clay, as viable alternatives to synthetic fungicides. Future research should prioritize the optimization of formulation concentrations and combinations, evaluation of storage stability, and, crucially, the conduct of in vivo poultry trials to confirm the efficacy, safety, and economic feasibility of large-scale commercial adoption.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study were included in this manuscript.

References

Akande, K. E., Abubakar, M. M., Adegbola, T. A. & Bogoro, S. E. Nutritional and health implications of Mycotoxins in animal feeds: A review. Pak J. Nutr. 5 (5), 398–403 (2006).

Magnoli, A. P., Poloni, V. L. & Cavaglieri, L. Impact of Mycotoxin contamination in the animal feed industry. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 29, 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2019.08.009 (2019).

Reddy, K. R. N., Nurdijati, S. B. & Salleh, B. An overview of plant-derived products on control of mycotoxigenic fungi and Mycotoxins. Asian J. Plant. Sci. 9 (3), 126–133. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajps.2010.126.133 (2010).

Mahmoud, D. A., Hassanein, N. M., Youssef, K. A. & Abou Zeid, M. A. Antifungal activity of different Neem leaf extracts and the Nimonol against some important human pathogens. Brazil J. Microbiol. 42 (3), 921–930. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-83822011000300021 (2011).

Cabral, L. C., Fernández Pinto, V. & Patriarca, A. Application of plant derived compounds to control fungal spoilage and Mycotoxin production in foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 166 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.05.026 (2013).

Machado, G. O. et al. Wood preservation based on Neem oil: evaluation of fungicidal and termiticidal effectiveness. Prod. J. 63 (5–6), 202–206. https://doi.org/10.13073/FPJ-D-13-00050 (2013).

Vijayalakshmi, A., Sharmila, R., Gowda, N. K. S. & Sindhu, G. Study on antifungal effect of herbal compounds against Mycotoxin producing fungi. J. Agric. Technol. 10 (6), 1587–1597 (2014).

Zhu, Y., Hassan, Y. I., Lepp, D., Shao, S. & Zhou, T. Strategies and methodologies for developing microbial detoxification systems to mitigate Mycotoxins. Toxins 9 (4), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins9040130 (2017).

Hussein, K. A. & Joo, J. H. Antifungal activity and chemical composition of ginger essential oil against ginseng pathogenic fungi. Curr. Res. Environ. Appl. Mycol. 8 (2), 194–203. https://doi.org/10.5943/cream/8/2/4 (2018).

Cai, J. et al. Antifungal and Mycotoxin detoxification ability of essential oils: A review. Phytother Res. 35 (11), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.7281 (2021).

Romoli, J. C. Z., Silva, M. V., Pante, G. C. & Hoeltgebaum, D. Anti-mycotoxigenic and antifungal activity of ginger, turmeric, thyme, and Rosemary essential oils in Deoxynivalenol (DON) and Zearalenone (ZEA) producing Fusarium graminearum. J. Sci. Food Agric. 101 (14), 5904–5912. https://doi.org/10.1080/19440049.2021.1996636 (2021).

Dharajiya, D. et al. Evaluation of antibacterial and antifungal activity of Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) extracts. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 8 (4), 212–217 (2016).

Sipos, P. et al. Physical and chemical methods for reduction in aflatoxin content of feed and food. Toxins 13 (3), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13030204 (2021).

Mathur, A., Verma, S. K., Singh, S. K., Prasad, G. B. K. S. & Dua, V. K. Investigation of the antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activity of compound isolated from Murraya koenigii. J. Med. Plants Stud. 9 (3), 45–50 (2011).

Abubakar, R. A. & Haque, M. Preparation of medicinal plants: basic extraction and fractionation procedures for experimental purposes. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 12 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_175_19 (2020).

Devi, L. J. Evaluation of petroleum ether extracts of some medicinal plants against root knot nematode on soybean. J. Exp. Sci. 1 (10), 20–22 (2010). Retrieved from www.jexpsciences.com.

Carvatho, J. M. F. C., Ferraz, S., Cardosa, A. A. & Dhingra, O. D. Treatment of Phaseolus vulgaris seeds with examyl dissolved in acetone or ethanol for the control of phytonematodes. Revista Ceris. 28, 580–587 (1981).

Kant, R. & Kumar, A. Review on essential oil extraction from aromatic and medicinal plants: techniques, performance and economic analysis. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 30, 100829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2022.100829 (2022).

Ibrahim, F. A. A. & Al-Ebady, N. Evaluation of antifungal activity of some plant extracts and their applicability in extending the shelf life of stored tomato fruits. J. Food Process. Technol. 5 (6). https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7110.1000340 (2014).

Tzortzakis, N. G. Impact of cinnamon oil-enriched on microbial spoilage of fresh product. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 10 (1), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2008.09.002 (2009).

Behiry, S. I. et al. Antifungal and antiaflatoxigenic activities of different plant extracts against Aspergillus flavus. Sustainability 14 (19), 12908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912908 (2022).

Fabry, W., Okemo, P. O. & Ansorg, R. Antibacterial activity of East African medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 60 (1), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(97)00128-1 (1998).

Griffin, S. G., Markham, J. L. & Leach, D. N. An agar Dilution method for the determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration of essential oils. J. Essent. Oil Res. 12 (2), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10412905.2000.9699509 (2000).

Gherbawy, Y. A., Elhariry, H. M., Alamri, S. A. & El-Dawy, E. G. Molecular characterization of ochratoxigenic fungi associated with poultry feedstuffs in Saudi Arabia. Food Sci. Nutr. 8 (10), 5298–5308. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1827 (2020).

Gherbawy, Y. A., Altalhi, A., Ioan, P. & El-Dawy, E. G. A. M. Occurrence of Fusarium species and determination of their toxins from poultry feeds during storage. Int J Microbiol 2024, 3474308. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/3474308

Gherbawy, Y. A., Abdel Fattah, K. E., Altalhi, A., Ioan, P. & Hussein, M. A. Detection of Mycotoxins and aflatoxigenic fungi associated with compound poultry feedstuffs in Saudi Arabia. Microbiol. Res. 16 (1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16010011 (2025).

El-Samawaty, A. M. A., Yassin, M. A., Bahkali, A., Moslem, M. & Abd-Elslam, K. A. Bio-fungicidal activity of Aloe Vera Sap against mycotoxigenic seed-borne fungi. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 20 (6), 1352–1359 (2011).

Makhuvele, R. et al. The use of plant extracts and their phytochemicals for control of toxigenic fungi and Mycotoxins. Heliyon 6 (10), e05291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05291 (2020).

Hussein, H. S. & Brasel, J. M. Toxicity, metabolism, and impact of Mycotoxins on humans and animals. Toxicol 167 (2), 101–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-483X(01)00471-1 (2001).

Awuchi, C. G. et al. Mycotoxins’ toxicological mechanisms involving humans, livestock, and their associated health concerns: A review. Toxins 14 (3), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14030167 (2022).

Atanda, S. A. et al. Mycotoxin management in agriculture. Greener J. Agric. Sci. 3 (2), 176–184 (2013). https://gjournals.org/GJAS

Al-Samarrai, G., Singh, H. & Syarhabil, M. Evaluating eco-friendly botanicals (natural plant extracts) as alternatives to synthetic fungicides. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 19 (4), 673–676 (2012).

Greco, M. V., Franchi, M. L., Rico Golba, S. L., Pardo, A. G. & Pose, G. N. Mycotoxins and mycotoxigenic fungi in poultry feed for food-producing animals. Sci. World J. 2014, 968215. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/968215 (2014).

Chaieb, K. et al. The chemical composition and biological activity of clove essential oil, Eugenia Caryophyllata (Syzygium aromaticum L. Myrtaceae): A short review. Phytother Res. 21 (6), 501–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.2124 (2007).

Pinto, E., Vale-Silva, L., Cavaleiro, C. & Salgueiro, L. Antifungal activity of the clove essential oil from Syzygium aromaticum on Candida, Aspergillus, and dermatophyte species. J. Med. Microbiol. 58 (11). https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.010538-0 (2009).

Nostro, A. et al. Effects of oregano, carvacrol and thymol on Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. J. Med. Microbiol. 56 (4), 519–523. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.46804-0 (2007).

Shreaz, S. et al. Cinnamaldehyde and its derivatives, a novel class of antifungal agents. Fitoterapia 112, 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2016.05.016 (2016).

Kačániová, M. et al. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cinnamomum Cassia essential oil and its application in food preservation. Open. Chem. 19 (1), 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1515/chem-2021-0191 (2021).

Zhang, W., Li, C., Lv, Y., Wei, S. & Hu, Y. Synergistic antifungal mechanism of cinnamaldehyde and Nonanal against Aspergillus flavus and its application in food preservation. Food Microbiol. 121, 104524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2024.104524 (2024).

Biswas, K., Chattopadhyay, I., Banerjee, R. K. & Bandyopadhyay, U. Biological activities and medicinal properties of Neem (Azadirachta indica). Curr. Sci. 82 (11), 1336–1345 (2002).

Subapriya, R. & Nagini, S. Medicinal properties of Neem leaves: A review. Curr. Med. Chem. Anti-Cancer Agents. 5 (2), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.2174/1568011053174828 (2005).

Prakash, B., Singh, P., Kedia, A. & Dubey, N. K. Assessment of some essential oils as food preservatives based on antifungal, antiaflatoxin, antioxidant activities and in vivo efficacy in food system. Food Res. Int. 49 (1), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2012.08.020 (2012).

Kaur, G. Epidemiology and management of post-harvest diseases of kinnow mandarin (Master’s thesis). Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana. (2021).

Bakkali, F., Averbeck, S., Averbeck, D. & Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils – A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 46 (2), 446–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.106 (2008).

Burt, S. Essential oils: their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 94 (3), 223–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.022 (2004).

Reddy, K. R. N. et al. Mycotoxin contamination of commercially important agricultural commodities. Toxin Rev. 28 (2–3), 154–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/15569540903092050 (2009).

Illueca, F. et al. Antifungal activity of biocontrol agents in vitro and potential application to reduce Mycotoxins (Aflatoxin B1 and Ochratoxin A). Toxins 13 (11), 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13110752 (2021).

Soković, M. D., Glamočlija, J. M. & Ćirić, A. D. Natural products from plants and fungi as fungicides. In: Nita M (ed) Fungicides (Chap. 9). IntechOpen. (2013). https://doi.org/10.5772/50277

Laranjo, M., Fernández-León, A. M., Potes, M. E., Agulheiro-Santos, A. C. & Elias, M. Use of essential oils in food preservation. In Méndez-Vilas A (ed) Antimicrob Res: Novel Bioknowledge Educ Programs (pp 177–188). Formatex Research Center. (2017). http://hdl.handle.net/10174/23047

Almeida, N. A. et al. Essential oils: An eco-friendly alternative for controlling toxigenic fungi in cereal grains. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf First published December 19, 2023. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.13251

Pillay, P., Maharaj, V. J. & Smith, P. J. Investigating South African plants as a source of new antimalarial drugs. J. Ethnopharmacol. 119 (3), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.003 (2008).

Abu-Seif, F. A., Abdel-Fattah, S. M., Abo Sreia, Y. H., Shaban, H. & Ramadan, M. M. Antifungal properties of some medicinal plants against undesirable and mycotoxin-producing fungi. J. Food Dairy. Sci. 34 (3), 1745–1756. https://doi.org/10.21608/jfds.2009.112162 (2009).

Aderiye, B. I. & Oluwole, O. A. Antifungal agents that target fungal cell wall components: A review. Agric. Biol. Sci. J. 1 (5), 206–216 (2015). http://www.aiscience.org/journal/absj

Geraldo, M., Arroteia, C. & Kemmelmeier, C. The effects of neem (Azadirachta indica A. Juss [Meliaceae]) oil on Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. medicagenis and Fusarium subglutinans and the production of fusaric acid toxin. Adv Biosci Biotechnol 1(1), 1–6. (2010). https://doi.org/10.4236/abb.2010.11001

Rath, C. C. & Patnaik, A. In-vitro antimycotic activity of selected essential oils and fungicides against Aspergillus Niger and Fusarium oxysporum. J. Exp. Biol. Agric. Sci. 6 (3), 490–497. https://doi.org/10.18006/2018.6(3).490.497 (2018).

Abdullahi, A. et al. Phytochemical profiling and antimicrobial activity of ginger (Zingiber officinale) essential oils against important phytopathogens. Arab. J. Chem. 13 (11), 8012–8025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.09.031 (2020).

Dorman, H. J. D. & Deans, S. G. Antimicrobial agents from plants: antibacterial activity of plant volatile oils. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88 (2), 308–316. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00969.x (2000).

Abbas, H. K. et al. Ecology of Aspergillus flavus, regulation of aflatoxin production, and management strategies to reduce aflatoxin contamination of corn. Toxin Rev. 28 (2–3), 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/15569540903081590 (2009).

Zhang, N. et al. Removal of aflatoxin B1 and Zearalenone by clay mineral materials: in the animal industry and environment. Appl. Clay Sci. 228, 106614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2022.106614 (2022).

Geofrey, N., Turyagyenda, L., Kigozi, A. R. & Mugerwa, S. The role of bentonite clays in aflatoxin-decontamination, assimilation and metabolism in commercial poultry. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 43 (3), 34649–34658. https://doi.org/10.26717/BJSTR.2022.43.006913 (2022).

Mahboubi, M. Zingiber officinale Rosc essential oil, a review on its composition and bioactivity. Clin. Phytosci. 5, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40816-018-0097-4 (2019).

Mossa, I. M. Antifungal effect of Thymus vulgaris methanolic extract on growth of aflatoxins producing Aspergillus parasiticus. Egypt. J. Bot. 61 (2), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejbo.2019.12540.1311 (2021).

Phillips, T. D. et al. Reducing human exposure to aflatoxin through the use of clay: A review. Food Addit. Contam. Part. A. 25 (2), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/02652030701567467 (2008).

Eskola, M. et al. Worldwide contamination of food-crops with mycotoxins: validity of the widely cited ‘FAO estimate’ of 25%. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 60 (16), 2773–2789. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2019.1658570 (2020).

Kihal, A., Rodríguez-Prado, M. & Calsamiglia, S. The efficacy of Mycotoxin binders to control Mycotoxins in feeds and the potential risk of interactions with nutrients: A review. J. Anim. Sci. 100 (11), skac328. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skac328 (2022).

Di Gregorio, M. C. et al. Mineral adsorbents for prevention of Mycotoxins in animal feeds. Toxin Rev. 33 (3), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.3109/15569543.2014.905604 (2014).

Bhat, R., Rai, R. V. & Karim, A. A. Mycotoxins in food and feed: present status and future concerns. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 9 (1), 57–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-4337.2009.00094.x (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU- DSPP-2025-12).

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, Project No. (TU-DSPP-2025-12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Youssuf Gherbawy: Conceptualization, data curation, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review, and editing; Hanan AlOmari: Methodology, writing-original draft preparation; Helal F. Alharthi: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, and funding were performed by the author; Eman El-Dawy: data curation, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review; Pet Ioan: Writing-review and editing and Hesham Elhariry: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing-original draft preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All the authors agreed to participate and publish.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gherbawy, Y.A., AlOmari, H., Al-Harthi, H.F. et al. Sustainable control of aflatoxin B1, ochratoxin A, and fumonisin B1 in poultry feed using plant extracts and clay. Sci Rep 15, 35966 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17693-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17693-9