Abstract

In 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated opioid prescribing guideline to emphasize use of non-addictive pharmacotherapies or nonpharmacologic procedures in place of or as an aid in starting the lowest feasible opioid dosage. However, the impact of nonpharmacologic pain management utilization on concurrent or subsequent opioid therapy dosing remains unexplored. We described patterns of nonpharmacologic pain management utilization prior to initial dose level in patients starting long-term opioid therapy. Utilizing electronic health data, we created a nonpharmacologic pain management utilization code list and applied it in a pre-existing cohort of patients with chronic pain prescribed long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) from August 2016 through September 2021. Univariate descriptions and bivariate associations of covariates with the initial LTOT mean daily morphine milligram equivalents (MME) categories were described via counts, percentages, and chi-square or Kruskal Wallis tests as appropriate. We also conducted a secondary multivariate regression analysis among patients with at least 12 months of health plan enrollment. There were 7679 patients for analysis with initial mean daily LTOT levels spanning 1 to 90 + MME. Nonpharmacologic therapies for pain management were infrequently utilized among patients starting LTOT and were dose dependent. This novel approach to identifying and categorizing nonpharmacologic therapies may help assess their clinical effectiveness in future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An estimated one in five adults in the United States have chronic pain1,2. Opioids were among the first-line treatment options for chronic pain before the addiction and overdose risks of opioids were widely publicized3,4. In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) responded to concerns about opioid pain medication misuse, the challenges of managing patients with chronic pain, and insufficient training in prescribing opioids by issuing recommendations for opioid prescriptions for chronic pain management5. An update of the Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain in 2022 emphasized use of non-addictive pharmacotherapies or nonpharmacologic procedures in place of or as an aid in starting the lowest feasible opioid dosage6. Non-addictive pharmacotherapies and nonpharmacologic procedures range from modestly effective physical therapies7,8 to more invasive interventions such as nerve block injections, radiofrequency denervation, or electric field spinal cord stimulation7,8. In the wake of the CDC recommendations, other clinical practice guidelines generally recommend use of noninvasive nonpharmacologic therapies for subacute, acute, or chronic pain first7,9,10.

The association of nonpharmacologic pain management utilization on concurrent or subsequent opioid therapy dosing in real world practice settings remains unexplored. Moreover, there is no standard approach to identifying nonpharmacologic pain management utilization in electronic health records and claims.

We therefore developed an approach to identify nonpharmacologic pain management utilization in electronic health records and claims and applied it in a pre-existing cohort of patients with chronic pain prescribed long-term opioid therapy (LTOT). Different pain management approaches could also be associated with higher or lower initial daily doses of LTOT. We hypothesized that use of nonpharmacologic pain management would be associated with lower opioid doses during the first 90 days of LTOT while accounting for other types of health care utilization and patient characteristics.

Methods

This was an electronic data-only retrospective cohort analysis. Patient data were from a prior study of the safety of opioid tapering11,12 conducted at Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO), an integrated insurance provider and healthcare delivery organization serving urban and suburban regions of Colorado; Denver Health (DH), a Colorado urban, integrated, safety-net health system; and Marshfield Clinic Health System (MCHS), a healthcare system serving a predominantly north central Wisconsin rural population. From each site, we derived data from secure “warehouse” research databases with patient data collected in electronic health records (EHRs), automated pharmacy records from health system pharmacies, and insurance claims for external medical or pharmacy utilization.

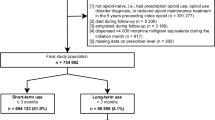

To be included for analysis, patients first needed to meet LTOT criteria defined as at least 3 opioid prescriptions of 1 daily morphine milligram equivalents (MME), dispensed on different dates within 90 days with gaps of ≤ 5 days. The first day of the initial dispensing among the three eligibility dispensings represented the index date – the beginning of LTOT. Patients had to be 18 or older on the index date that spanned from the date range of available procedure data from the prior study ( August 2, 2016, though September 28, 2021). Patients were excluded if they were < 18 years old on the index date; not enrolled in the health plans (KPCO and MCHS) on or before the index date or did not meet empanelment criteria for DH14 for at least 12 months before and after the index date; or received dispensings of buprenorphine or methadone for treatment of opioid use disorder in the 12 months before the index date.

Outcome

The outcome was mean daily MME during the initial 90-day LTOT interval. This continuous measure was also categorized into four groups (1 to 19, 20 to 49, 50 to 89, and ≥ 90 MME).

Nonpharmacologic pain management utilization assessment

We created a novel approach to identifying and categorizing nonpharmacologic therapies for a nonpharmacologic pain management utilization assessment. Nonpharmacologic pain management procedures were identified by Current Procedural Terminology-4 (CPT-4) codes in electronic health records and claims. We first gathered information regarding pain management CPT-4 coding using the following sources: American Medical Association’s CPT 2020 codebook15, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services billing and coding articles16, and study sites’ proprietary documentation on pain management-related conditions and treatment procedures. The latter provided guidance on classifying procedure types specifically described for pain management as injections or nerve implants, physical or occupational therapies, and complementary and alternate medicine (CAM) therapies. Injections or nerve implants procedures included arthrocentesis aspirations, chemodenervation of muscles, epidural injections, implanted neurostimulators, kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty, musculoskeletal injections, nerve blocks, nerve destruction by neurolytic agents, other nervous system injections, or radiofrequency nerve ablation. CAM procedures were acupuncture, chiropractic, or osteopathic procedures for pain relief. Procedure codes were individually reviewed by the investigator (DM) and a physician (IB) and other health services experts to ensure applicability and clinical relevance, and then categorized. Specific CPT-4 codes cross-referenced to the procedure groups are shown in Table 1.

Duplicate procedure codes on the same procedure date were removed for each patient. Total procedures and procedure types were summed for the period 1 to 365 days prior to the index date.

Covariates

We calculated mean daily MME opioid dose up to 1 year prior to the index date per patient as previously described11,12. Before the index date, patients may have been prescribed opioids, but not consistent enough to qualify as LTOT. Follow-up time before the index date was assessed as the number of days from the beginning of patient enrollment or empanelment prior to the index date, which was capped at 365 days.

We included various patient-level characteristics such as: health system, sex (male or female, no other recorded types), race (7 categories collapsed as “White”, “Non-white”, or “Unknown”), ethnicity (as “Hispanic”, “Non-Hispanic” or “unknown”) and age in years at first qualifying LTOT dispensing. Since there were several different patterns of health insurance, they were collapsed into “Federal or State Subsidized,” which included Medicare and/or Medicaid; “Other,” which included various commercial, private payer, self-funded and other insurance types; and “Unknown”.

We also included separate indicators for cancer and mental health diagnosis and the sum of other distinct diagnosis categories related to chronic pain (autoimmune, central sensitizing, gastrointestinal, genetic, infectious, metabolic, musculoskeletal, neurological, psychological, traumatic injury, urogynecological, nonspecific pain) in the year prior to the index date. The diagnoses were identified from International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes occurring in any clinical setting (available upon request).

Statistical methods

Univariate descriptions and bivariate associations of the covariates with the initial LTOT mean daily MME categories were described via counts, percentages, and chi-square or Kruskal Wallis tests as appropriate. Two-sided Cochran-Armitage trend tests were used to assess the occurrence of the three nonpharmacologic pain management categories versus initial baseline LTOT mean daily MME categories.

We also conducted a secondary multivariate regression analysis of the natural log of mean daily MME during the initial 90-day LTOT interval. This was limited to patients with at least 12 months of health plan enrollment prior to the index date. This ensured a more complete capture of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic pain management utilization. In the regression model, we included covariates with no missing values—health plan site (KPCO referent), age (10 year increase), sex (male vs. female), COVID-19 era (during or pre COVID), any ED or inpatient admission (yes/no for each), prior cancer or mental health diagnoses (yes/no for each), prior daily mean 10 MME increase, and any injections, CAM, or physical therapy procedure for pain (yes/no for each). Exponentiated estimates were their relative risks to the referent category or unit of analysis for continuous measures.

All p-values < 0.05 were be interpreted as a statistically significant. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4/STAT 15.1 (Cary, NC).

Results

There were 7679 patients in the final cohort after excluding those with greater than 90 days between their first and third opioid dispensing (75), < 18 years age5, and with buprenorphine or methadone dispensing in the 12 months prior to the index date (70).

There were 4164 patients (54%) that initiated LTOT at less than 20 MME (Table 2). The peak number of patients was in 2017 with declining numbers thereafter (annualized average 1684 from 2016 to 2019) and into the COVID-19 pandemic era of 2020–2021 (annualized average 820). There was a trend toward younger ages with increasing initial LTOT MME levels and females outnumbered males, however there was no apparent relationship of race or Hispanic ethnicity on initial LTOT MME level. Most patients had federal or state subsidized health insurance. There was an increasing proportion of patients with cancer diagnoses within increasing initial LTOT levels and larger proportion with mental health diagnoses with initial LTOT MME of 50 or more. Larger prior mean daily MME was positively associated but highly skewed with increasing initial LTOT levels (Table 3).

There was a significant shift to shorter enrollment duration with increasing initial LTOT level. This was most pronounced at the largest LTOT level > = 90 MME where 38% had at least 1 year enrollment versus 75% for the lowest LTOT level.

All health care utilization metrics were highly skewed towards zero. There was no discernable trend of emergency department utilization with initial LTOT levels, whereas hospitalization was more common among those with a higher initial LTOT level.

Overall, 41% of the patient cohort had at least 1 nonpharmacologic pain management procedure up to 1 year prior to initiating LTOT. There were decreasing significant trends (Cochran-Armitage trend tests: injections or nerve implants, p < 0.0001; physical or occupational therapy, p = 0.0046; complementary or alternative medicine therapy, p = 0.0082) with increasing initial LTOT level for each category of nonpharmacologic pain management (Table 2).

In the secondary multivariate regression analysis, 5112 patients (67%) had at least 12 months of health plan enrollment or empanelment prior to the index date (Table 4). Only the Denver Health site relative to KPCO, 10 year age increase, males vs. females, any emergency or inpatient admissions, any cancer or mental health diagnoses, and any CAM related procedures for pain were significantly associated with a 10 mean daily MME increase of LTOT dosing. Notably, there were null relationships for injections or physical therapy for pain.

Discussion

Using a novel list of nonpharmacologic therapies for pain, we quantified utilization using electronic health records and claims across three health system sites. We found that nonpharmacologic therapies for pain management were infrequently utilized among patients starting LTOT from August 2016 through September 2021. Lower utilization of nonpharmacologic therapies was also associated with increasing initial LTOT level. Since the CDC’s nonpharmacologic pain management recommendation6 was after the date range of the study, it may be several years before a measurable impact on LTOT dosing is found.

Patients starting LTOT at higher mean daily doses, particularly ≥ 90 MME, also had shorter follow-up time prior to the initial LTOT interval. This implies that individuals that recently joined health systems may have greater health care/pain management needs. However, there may also have been incomplete capture of measures of utilization, such as emergency department or inpatient visits and pain management procedures.

In the multivariate regression analysis that controlled for several characteristics, as expected, patients with larger baseline mean daily MME, prior inpatient encounters and cancer diagnoses had significant estimates associated with increasing MME in the initial LTOT interval. However, nerve block injections, radiofrequency denervation, or electric field spinal cord stimulations as a group was not associated with increased MME dose levels. These procedures are an effective non-pharmacologic alternative to opioids and should be utilized when clinically appropriate7,8.

A strength of this study was use of a diverse population from 3 health care systems serving urban, suburban, and rural patients with commercial and subsidized health insurance. We also showed that it is feasible to assess utilization of nonpharmacologic therapies for pain management with electronic medical data. However, there were limitations. Comparing different opioid formulations using MMEs is only suitable for data only research studies such as this one17. MME has inherent limitations in accuracy, variability among individuals and drugs, leading to a high risk of misapplication in clinical practice18. There was also potential for unmeasured confounders and bias from misclassified or missing pain management procedures or opioid dispensings. Relatedly, there were no medical record reviews performed to verify procedures or opioid dosing. Our findings also only addressed utilization but not effectiveness of nonpharmacologic pain management.

This novel nonpharmacologic pain management utilization measure could be replicated in other health systems and validated using medical record review and/or patient surveys. This would quantify the effect of nonpharmacologic therapies for pain management in patients with chronic pain.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to required additional confidential/privacy protections but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dahlhamer, J. et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and High-Impact chronic pain among Adults - United states, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 67 (36), 1001–1006. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2 (2018).

Yong, R. J., Mullins, P. M. & Bhattacharyya, N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the united States. Pain 163 (2), e328–e332. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291 (2022).

Mills, S. E. E., Nicolson, K. P. & Smith, B. H. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br. J. Anaesth. 123 (2), e273–e283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.023 (2019).

Skelly, A. C. et al. Noninvasive nonpharmacological treatment for chronic pain: A systematic review update. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); (2020).

Dowell, D., Haegerich, T. M., Chou, R. & CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 65 (1), 1–49. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1 (2016).

Dowell, D., Ragan, K. R., Jones, C. M., Baldwin, G. T. & Chou, R. Prescribing opioids for Pain - The new CDC clinical practice guideline. N Engl. J. Med. 387 (22), 2011–2013. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2211040 (2022).

Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Pain Management Best Practices: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations.(Accessed 7 August 2023). www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pain-mgmt-best-practices-draft-final-report-05062019.pdf (2019).

Smith, H., Youn, Y., Guay, R. C., Laufer, A. & Pilitsis, J. G. The role of invasive pain management modalities in the treatment of chronic pain. Med. Clin. North. Am. 100 (1), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2015.08.011 (2016).

Qaseem, A. et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American college of physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 166 (7), 514–530. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2367 (2017).

Qaseem, A., McLean, R. M., O’Gurek, D., Batur, P. & Lin, K. Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic management of acute pain from Non-Low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: A clinical guideline from the American college of physicians and American academy of family physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 173 (9), 739–748. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-3602 (2020).

Binswanger, I. A. et al. Opioid dose trajectories and associations with mortality, opioid use disorder, continued opioid therapy, and health plan disenrollment. JAMA Netw. Open. 5 (10), e2234671. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.34671 (2022).

Glanz, J. M. et al. Association between opioid dose reduction rates and overdose among patients prescribed Long-Term opioid therapy. Subst. Abus. 44 (3), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/08897077231186216 (2023).

World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. (2025).

Hambidge, S. J. et al. Integration of data from a safety net health care system into the vaccine safety datalink. Vaccine 35 (9), 1329–1334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.01.027 (2017).

AMA Releases. CPT® code set. (Accessed 12 July 2021). https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-releases-2020-cpt-code-set. (2020).

Example Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare coverage database. Article - billing and coding: Pain management (A52863). (Accessed 9 August 2023). (2023).

Adams, M. C. B., Sward, K. A., Perkins, M. L. & Hurley, R. W. Standardizing research methods for opioid dose comparison: the NIH HEAL morphine milligram equivalent calculator. Pain 166 (8), 1729–1737. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000003529 (2025).

Fudin, J., Raouf, M., Wegrzyn, E. L. & Schatman, M. E. Safety concerns with the centers for disease control opioid calculator. J. Pain Res. 11, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S155444 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank Judith Hase, BS, Morgan Ford, MS, and Melanie Stowell, MSc for project management and data collection assistance; Sai Sudha Medabalimi, MS, MPharm, Kris Wain, MS, and M. Joshua Durfee, MSPH for data collection and quality assurance; and Stanley Xu, PhD, MS for statistical expertise.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA047537. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the study sites.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DM had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.Concept and design: DM, IB, KN, JG.Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: DM, IB, KN, AN, JG.Drafting of the manuscript: DM, IB, JG.Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: DM, IB, KN, AN, MF, DR, JG.Statistical analysis: DM.Obtained funding: IB, JG.Administrative, technical, or material support: DM, MF, DR.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

This data-only study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Interregional Institutional Review Board (IRB) with a waiver of informed consent and with IRB ceding from the other health systems. We confirm that all research was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki13.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McClure, D.L., Binswanger, I.A., Narwaney, K.J. et al. Patterns of long-term opioid therapy with prior nonpharmacologic pain management utilization. Sci Rep 15, 31924 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17979-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17979-y