Abstract

Dengue and Chikungunya are caused by the same vectors, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Both mosquitoes are endemic in Pakistan, and various parts of the country experienced outbreaks of Dengue virus over the past decades. However, Chikungunya infection remained either unidentified or misdiagnosed before its outbreak in Karachi during 2018-19. This study aimed to determine the seroprevalence of Dengue virus (DENV) (a flavivirus) and Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) (an alphavirus) in suspected samples of the Pakistani population collected during 2014–2015. Immunological and molecular methods were used for the diagnosis of DENV and CHIKV. The serum samples of both healthy and febrile participants were tested for prior exposure to CHIKV and DENV using indirect IgG ELISA. The current infection of DENV was diagnosed by the presence of NS1 antigen (ELISA) and IgM (ELISA), whereas the active infection of CHIKV was identified by the presence of viral RNA (RT-PCR) and IgM. The seroprevalence of DENV and CHIKV as a single infection was 70% and 17%, respectively. However, 6% of febrile patients tested positive for both DENV and CHIKV, representing co-existence and co-infection of DENV and CHIKV during 2014–2015 in Pakistan. The presence of DENV and CHIKV co-infection evidently proved that CHIKV also caused infection during 2014-15 before its known outbreak of 2018-19. This study addressed gap analysis and highlighted the need for a comprehensive diagnostic approach and facilities in Pakistan for other arboviruses like Zika virus the virus shares the same vectors. In conclusion, developing countries like Pakistan must gain competence in response and preparedness to face future probable co-infection outbreaks of DENV, CHIKV, and other arboviruses in Pakistan. Further surveillance and epidemiological studies are required to determine the true burden of these infections and the spectrum of diseases associated with these exposures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dengue virus (DENV) and Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) are transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. These two utmost significant vectors are susceptible to the virus, support the viral multiplication, and are capable enough to transmit the virus to another host. Aedes aegypti originated in Africa and distributed worldwide, whereas Aedes albopictus was discovered in Asia and is indigenously found in Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the islands of the Western Pacific1.

DENV and CHIKV are single-stranded viruses having positive-sense RNA. The family of DENV is Flaviviridae, and the genus is Flavivirus, having 5 known serotypes (DENV serotypes 1–5). Reference2 Ren Kimura and Susumu Hotta were the scientists who first isolated DENV from blood collected during the 1943 epidemic in Nagasaki, Japan. However, CHIKV is placed under the genus “alphavirus” of the Togaviridae family. Firstly, during an outbreak in 1952 and 1953, CHIKV was retrieved from the febrile patient blood in Tanzania3. The word “Chikungunya” belongs to the Bantu language of the Makonde community, which means “that which bends up” due to the characteristic arthralgia throughout Chikungunya fever. Up till now, 3 notorious strains of CHIKV have been identified, which are Asian-West African, East-Central, and South African4. Mostly, the people who live in tropical and subtropical areas get infected with DENV and CHIKV, as these parts of the world are densely populated with their vector, which is responsible for transmission of these viruses5. Present analogous clinical presentation, particularly in the initial stages of infection6. Therefore, early and accurate diagnosis is imperative. Table 1 summarizes the test parameters to diagnose DENV and CHIKV seroprevalence with respect to the period of illness2,7.

Pakistan is a World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognized Dengue-endemic country. The first outbreak (caused by DENV-2) was reported in 19948. Afterward, intermittent cases of Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever were constantly reported from various locations in Pakistan. The introduction of DENV-1 and DENV-2 was notified.8,9. Furthermore, an outbreak of Dengue fever in the Baluchistan province (causative agents: DENV-1 and DENV-2) was reported by Paul et al. (1998). Furthermore, in Karachi, Pakistan, healthcare facilities experienced an unexpected escalation in the population of patients with Dengue hemorrhagic fever from September to December 200510. DENV-3 was found involved in this epidemic after genotyping. This outbreak was possibly a result of the encounter of DENV-3 in a population with previous sensitization to DENV-1 and DENV-2, resulting in severe disease.9,10. Subsequently, in 2006, Pakistan had its leading and most severe epidemic of Dengue hemorrhagic fever that was caused by DENV-2 and DENV-311. In another study, it is documented that during 2003, 26.3% (3952) tested positive for anti-dengue IgM out of 15,040 patients. Among all tested individuals, 63.2% were male and 36.8% were female. Different sporadic cases were detected throughout 2004 to 2007 to 201012. The re-infection by other serotypes has been found to intensify Dengue severity.13,14. The highest incidence of Dengue epidemics was observed in Karachi after the year 2009. Between 2013 and 2017, there were 17115 confirmed Dengue cases. Previous years showed peak incidence of 5.2% in 2010, 32% in 2013, 16.7% in 2015, 22.5% in 2016, and 12% in 2017. Dengue cases have been more frequent since 2009, while a series of 17,115 Dengue-positive cases were reported between 2013 and 2017 in Karachi15.

Unlike the Dengue virus, the Chikungunya virus was first detected in Pakistan in rodents in 198316. Later in 2011, some patients with Dengue in Lahore also had CHIKV antibodies17. A cross-sectional study (2015-16) in Pakistan was conducted by subjecting serum samples to IgM, RT-PCR (to detect viral RNA), and anti-CHIKV neutralizing bodies18. The research gap of surveillance and demographic analysis was palpable. Moreover, it has been evidently found worldwide that CHIKV remains underreported. The main reason is its similarity of clinical manifestation (fever, rash, and joint pains) with other diseases such as Dengue and Typhoid fever. The rapid diagnostic tests that are available in most laboratories for use in the diagnosis of Chikungunya infections may complicate the diagnostic process, such as IgM antibody detection, which are usually present in the patient’s blood for very long periods19. Many cases of Dengue infection had been misdiagnosed across the world, while the incidence of CHIKV infection is much higher than claimed in previous studies. Furthermore, a recent retrospective study revealed that CHIKV outbreaks occurred but were commonly mistaken for Dengue epidemics worldwide20. In India, co-infection with DENV and CHIKV was found to be 1.15%21. These findings raised the possibility that Chikungunya or other arboviral infections were possibly involved. This highlighted the importance of distinguishing Chikungunya fever from other probable infections to ensure adequate management of the patients. The 2018–19 outbreak studies emphasized a pivotal shift in arboviral research in Pakistan, with a focus on the unnoticed Chikungunya burden and its co-infection with Dengue. Consequently, these results raised the importance of investigating co-existence in the infection episodes of Dengue before 201822,23,24. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the presence of Chikungunya infection and co-infection of Dengue and Chikungunya in terms of current and past infection in the suspected samples collected during 2014–2015 in Pakistan.

Materials and methods

Approval and ethics declaration

The research proposal was accepted and approved by the Board of Advanced Studies and Research (BASR) of Jinnah University for Women, Karachi, Pakistan (BASR/Extr./47th Proc/June). The member of the International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE) ensures research projects adhere to ethical standards and guidelines. BASR has also evaluated the research study that was conducted in accordance with the standard protocols such as WHO. Informed consent was obtained from each participant and their legal guardians. Consent was acquired in black and white from each patient. The clinical trial number was not applicable.

Case selection and clinical samples

A total of 100 archived serum samples were drawn from febrile patients presenting at healthcare facilities in Karachi, Hyderabad, Lahore, and Rawalpindi between 2014 and 2015. The sample size was determined based on the number of available and appropriately stored specimens meeting inclusion criteria, rather than through statistically determined sampling. This was due to practical constraints, including limited access to archived samples, budgetary limitations, and the logistical challenges of cold chain storage at -80 °C. The period of 2014–15 was specifically selected for this study due to the evident research gap in existing literature. No significant studies were reported from Pakistan during the referred timelines on the subject under investigation.

Case definitions were applied according to WHO (2006) and CDC guidelines25,26, identifying suspected arboviral cases as patients with acute onset of fever (> 38.5 °C) accompanied by symptoms such as headache, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, rash, retro-orbital pain, or severe arthralgia/arthritis, and residence in an endemic or epidemic area within 2 weeks prior to symptom onset. Samples were categorized as acute-phase (≤ 8 days post-onset) or convalescent-phase (10–15 days post-onset) per PAHO and CDC (2011) criteria. In addition, patients who tested positive for malaria (ICT or microscopy), typhoid (blood culture), leptospirosis (PCR and ELISA), or leishmaniasis (Giemsa staining LD bodies via microscopy and leishmania antibodies) based on initial hospital diagnostics were excluded to minimize perplexing causes of febrile illness. These samples were then preserved at -80 °C.

Negative samples as control

In addition, a total of 10 serum specimens obtained from healthy individuals without any signs and symptoms of CHIKV or DENV infection were included as negative controls.

Testing

WHO and CDC guidelines were used (Fig. 1). All the serum samples were subjected to ELISA for testing the presence of Dengue NS1 antigen, anti-dengue IgM, anti-dengue IgG immunoglobulins, anti-chikungunya IgM & anti-chikungunya IgG immunoglobulins. In addition, the real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain test was also carried out for the detection of CHIKV RNA. Each specimen was assayed in duplicate25,26,27,28.

Serological testing

Commercial ELISA kits were used for serological detection of IgM and IgG antibodies against both Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) and Dengue virus (DENV), as well as DENV NS1 antigen. All assays were performed following the manufacturers’ instructions.

DENV IgM and IgG ELISA

Detection of anti-DENV IgM and IgG antibodies was conducted using Panbio Dengue IgM and IgG Capture ELISA kits. Assays included control wells (positive, negative, and calibrator), sample incubation, tracer solution (antigen–HRP MAb) application, and colorimetric detection at 450 nm. Classification followed the manufacturer’s cut-off criteria.

DENV NS1 Antigen ELISA

NS1 antigen detection was carried out using the Panbio Dengue Early ELISA kit, with standard procedure for sample addition, incubation, HRP-conjugated MAb binding, substrate reaction, and optical density reading.

CHIKV IgM and IgG ELISA

Anti-CHIKV IgM and IgG were detected using EUROIMMUN ELISA kits. Samples and controls were processed as per kit guidelines, including incubation, washing, enzyme conjugation, substrate addition, and absorbance measurement at 450 nm with a reference filter of 620–650 nm.

All assays were performed in duplicate using the ELX 800 ELISA reader (Biotek). Results were interpreted based on ratio values as positive, negative, or borderline.

RNA extraction

The genomic RNA of CHIKV was extracted by using a volume of 140 µl serum. The QIAGEN QIAmp Viral RNA Mini Kit (No. 52904) was used, and all the manufacturer’s modus operandi were followed. Spin protocol was applied to elute viral RNA using QIA spin columns. A single elution (with 60 µl of elution buffer) is adequate to elute a minimum of 90% of RNA. However, we carried out double elution (2 × 40 µl of buffer), which increases yield up to 10%. The eluted viral RNA was stored at -80 °C until it was used.

Real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain test

All suspected serum samples were tested for CHIV RNA using real-time RT-PCR with a fluorescent probe, employing the QIAGEN QuantiTect Probe RT-PCR kit, currently in use at the Arboviral Diagnostic Laboratory, DVBD, CDC. Dengue-positive samples (n = 2) served as negative controls, alongside negative extraction (n = 1) and no-template controls (n = 1). Positive extraction controls (n = 4), a positive RNA control (n = 1), and an internal RNA control (n = 1) were included to ensure assay validity. Positive controls were provided by the CDC. Amplification was performed on a Cepheid SmartCycler system following standard cycling parameters (PAHO & CDC, 2011). Positive controls were generously provided by CDC.

Results

Age, sex, and regional distribution of suspected patients

Samples of 100 patients from 2014 to 15 were used in this study to assess the hypothesis that earlier Dengue outbreaks may have involved undetected Chikungunya cases. Patients were suspected of mosquito-borne viral infection of Dengue or Chikungunya. Among 100 patients, 59 (59%) were female, while 41 (41%) were male (Table 3).

Mostly patients were in the age range of 31–40, which is 39% of the total population used in the current study, while 22% were in the age range of 41–50. About 63% of the population belongs to urban areas, while 37% are from rural parts.

Sign and symptoms

At the time of sample collections, patients showed some symptoms, which included fever, joint and muscle pain, headache, and abdominal cramps. Most of the patients were suffering from moderate fever as compared to high-grade fever. The frequency of signs and symptoms in 100 enrolled patients that were suspected for Dengue and Chikungunya was also recorded. In total, 65% of people had moderate fever, while 29% of people were suffering from high-grade fever. Histories were taken from patients, and it showed that the duration of fever is majorly around 4–8 days (Table 4). Before admission to the hospital, 42% of patients had anti-malarial therapy, while 27% had received anti-bacterial along with anti-malarial therapy (Table 5).

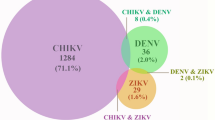

Seroprevalence of Dengue virus and Chikungunya virus

Serum samples were subjected to ELISA for NS1 antigen, anti-dengue IgM, anti-dengue immunoglobulins G (IgG), anti-chikungunya IgM, & anti-chikungunya IgG immunoglobulins detection. For CHIKV RNA detection in suspected sample were also carried out by using Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase PCR. Among suspected blood specimens, 70% were positive for Dengue, while 17% were positive for Chikungunya infection. The frequencies of signs and symptoms in patients with Dengue and Chikungunya-positive samples is shown (Table 6).

To rule out Dengue infection, DENV NS1 was detected. 6 patients showed positive results for DENV NS1. 9 were positive for anti-dengue virus IgM, while 15 patients had positive results for both NS1 antigen and anti-dengue virus IgM, which represent acute infection of Dengue virus. Among 27 patients, secondary infection was found in 5 patients (Table 7). It was done by detecting IgG antibody with anti-dengue virus. Results showed that gender and locality are not linked with DENV incidence. The duration of fever among Dengue patients is varied. 8 (11%) showed the fever duration between 1 and 3 days, while 62 (89%) had the fever duration of 4–15 days. After confirmation of Dengue, symptoms were observed carefully. 100% of the population showed fever, arthralgia (joint pain), and myalgia (muscle pain), followed by abdominal cramps (62%), headache (59%), shoulder pain (55%), back pain (30%), rash (24%), and vomiting (10%). 40% of patients were suggested to have anti-malarial, 26% antibacterial with anti-malarial, and 21% were prescribed only antibacterial therapy.

In total, 17% of patients were positive for Chikungunya. Eleven (11) patients were positive for anti-chikungunya IgM alone with the fever duration of 8–11 days. Only 3 patients were positive for Chikungunya virus RNA with a 1–3 day fever duration. In addition, 3 patients showed anti-chikungunya IgM and CHIKV RNA with the fever from 1 to 3 days. (Table 8)

The frequency of clinical signs and symptoms was compared between patients with Dengue (n = 70) and Chikungunya (n = 17). Using Fisher’s exact test (GraphPad Prism version 8.02), several symptoms were common to both infections, while others showed notable differences in distribution, such as fever, arthralgia, and myalgia, were present in 100% of patients in both groups, with no statistically significant difference (p > 0.9999 for all comparisons). Headache occurred in 59% of Dengue patients and 35% of Chikungunya patients (p = 0.106; 95% CI: 0.123–1.099). Abdominal pain was significantly more frequent in Dengue (62%) than in Chikungunya (5%) (p < 0.0001; 95% CI: 0.003–0.219). Shoulder pain was present in all Chikungunya patients (100%) compared to 55% of Dengue cases (p = 0.0004; 95% CI: 3.222–Infinity). Back pain was reported in 30% of Dengue cases and 35% of Chikungunya cases (p = 0.7716; 95% CI: 0.395–3.747), also showing no significant difference. Rash was observed more often in Chikungunya (47%) than in Dengue (24%), though the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.0775; 95% CI: 0.909–8.625). Vomiting was reported in 17% of Chikungunya patients and 10% of Dengue patients (p = 0.4027; 95% CI: 0.489–8.846), showing no statistically significant difference. Polyarthritis and difficulty in walking were reported in 100% of Chikungunya patients and only 1–2% of Dengue patients, with statistically significant differences (p < 0.0001 for both; 95% CI: 142.4–Infinity). (Table 9)

The statistical tool GraphPad Prism (version 8.02) was used for comparative analysis based on odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values between differential parameters in Dengue and Chikungunya patients revealing significant differences in key clinical manifestations (Table 10; Fig. 2). Myalgia was more frequent in DENV cases (66%) compared to CHIKV (35%), with an OR of 0.284 (95% CI: 0.090–0.822; p = 0.0286). In contrast, several parameters were significantly associated with DENV infection. A fever > 102℉ (39℃) was reported in 66% of DENV patients and was absent in CHIKV cases (OR = 0.000; 95% CI: 0.000–0.479; p = 0.0024). Arthralgia was observed in 100% of CHIKV cases and 50% of DENV cases, resulting in an infinite odds ratio (OR = ∞; 95% CI: 4.06 – ∞; p < 0.0001). No significant differences were observed for headache (p = 0.7814) or bleeding manifestations (p = 0.4032). Rash was also more frequent in CHIKV cases (71%) compared to DENV cases (33%), with an OR of 4.90 (95% CI: 1.63–13.67; p = 0.0061). Shock was observed in 33% of DENV patients and was not present in any CHIKV case (OR = 0.000; 95% CI: 0.000–0.513; p = 0.0045). Hematological parameters also showed marked differences. Leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and increased hematocrit were significantly more common in DENV cases. All of these parameters yielded ORs of 0.000 with p-values < 0.0001 and narrow CIs, indicating strong associations with DENV. Lymphopenia also showed a significant association with DENV (OR = 0.000; 95% CI: 0.000–0.389; p = 0.0024). Thrombocytopenia was present in 100% of DENV cases and in only 35% of CHIKV cases (OR = 0.000; 95% CI: 0.000–0.0383; p < 0.0001).

Co-infections of Dengue virus and Chikungunya virus

In the present study, 6 samples were found positive for both Dengue and Chikungunya. It was confirmed by detecting CHIKV RNA and/or anti-chikungunya IgM in combination with NS1 antigen and/or anti-dengue virus IgM.

Discussion

Our study falls between 2014 and 2015, proficiently covering the whole period of illness including early onset of infection till the convalescent period for both Dengue and Chikungunya infection. This study was first of its type for specific period that is 2014–2015 investigating the seroprevalence of DENV and CHIKV by subjecting all suspected samples for a test suite. Non-structural protein 1 (nsP1) was indirectly detected by targeting the coding region through RT-PCR in CHIKV genome. Moreover, NS1 antigen of DENV was directly detected in the tested samples through ELISA. The IgM and IgG antibodies produced specifically in each case of DENV and CHIKV infection were diagnosed by ELISA. Whereas, initially CHIKV was reported during early 1983 in Pakistan. Later on, a cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Pediatrics, King Edward Medical University/Mayo Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan. A total of 75 serum samples collected during May to October, 2011 from febrile patients. Results declared 3 cases of Chikungunya fever and 33 cases of Dengue fever28,29.

Afterwards, researchers evidently found CHIKV in Pakistan during a seroprevalence study that began in April of 2015 and was continued for 2 years30. A study conducted during 2016 revealed that Chikungunya cases increased in Karachi and connecting areas of Pakistan within months after huge outbreaks in India during 201631.

In this study data analysis was carried out to analyze demographic information and the results of each test confirming the different phase of infection. Our seroprevalence study covered a period of two years (2014-15). Total 100 blood samples meeting the definition of suspected Dengue and Chikungunya infection cases. The targeted cases were enrolled from three cities of Pakistan that were mainly from Karachi (70%) and lesser from Lahore (20%) and Hyderabad (10%). Chiefly, patients were of age range 31–40 (39%) and few patients were 41–50 years old (22%). The enrolled patients of our study comprised of 59% females and 41% males. Among them, the urban cases were 63% in comparison to 37% of rural cases.

All patients were suffering from fever, arthralgia. Myalgia, headache and abdominal pain were appeared with very high percentage that were 98%, 94% and 85% respectively. These symptoms were found at the time when we collected the sample. More than half of the patients (65%) were suffering from fever ranges from 100 to 103℉ and classified as moderate fever. High grade fever ranges from 103 to 105℉ was found in 29% patients. The 88% of patients were having history of fever maximum to 12 days representing the acute phase. Elaborately, this 88% cases included mainly 53% patients with fever history of 4–8 days followed by 20% of > 4 days and 15% with 9–12 days of history of fever. The suspected patients for Dengue and Chikungunya on the basis of symptom had already received anti-malarial therapy and antibacterials in the percentage of 42% and 26%. Usually, it is difficult to differentiate on the basis of symptoms between DENV infection, CHIKV infection, Typhoid (bacterial infection) and Malaria. Therefore, diagnosis prior to antibiotic treatment is logical and justified. Unfortunately, this modus operandi is not being followed in Pakistan due to number of factors like socio-economic condition, lack of diagnostic facilities and awareness.

Results showed seventy (70%) seroprevalence of Dengue infection due to several epidemics of Dengue infection during recent decades in Pakistan. Our results have high seroprevalence rate than other study that showed 38% seroprevalence of Dengue in 2013 during an outbreak in KPK and Punjab. However, Qureshi et al. reported 82% seroprevalence in Lahore during 2012 greater than our noticed Dengue seroprevalence32. In our study we found the incidence of DENV infection was not associated with gender and region. In general, most of the study from subtropical and tropical regions of the world documented that male gender is more susceptible to DENV than feminine. A study from Samanabad and Shalimar town notified 89% male and 35% female cases of DENV. With respect to age group, the highest Dengue incidence was found in 21 to 30 years old patients33.

We reported that 08 (11%) patients were suffering from fever that lasted for 1–3 days whereas 62 cases (89%) had 4–15 days history of fever. Each and every patient had arthralgia and myalgia, but other symptoms found in lower percentage that were abdominal pain (62%), headache (59%), shoulder pain (55%), back pain (30%), rash (24%) and vomiting (10%) among Dengue confirmed patients. In other studies, the patients experienced fever (100%), muscle pain (68.2%), mucocutaneous hemorrhagic manifestations (58.2%), headache (55.5%), cutaneous (53.6%), nausea (39.1%), and visual pain (20%). Unluckily, we found in our study that patients with confirmed Dengue infection were faultily prescribed anti-malarial (40%), antibacterials plus anti-malarial both (26%) and antibacterials (21%) alone without prior diagnostic tests.

Our study revealed the existence of the Chikungunya virus in Pakistan with the seroprevalence rate of 17%. Our findings demonstrated that the occurrence of CHIKV infection was not interrelated to the patient’s sex and region. However, during 2011-12 in India, the most affected age group was 16–45 years. Females were more affected than males34. We reported that all CHIKV-positive patients presented fever, arthralgia, myalgia, shoulder pain, and polyarthritis. Around 76.5% of patients complained of difficulty while walking, 47% showed body rashes, headaches were observed in 35.3%, back pain in 35.3%, and abdominal cramps in 29.4%, while 17% suffered from vomiting. Only 8 (47.5%) CHIKV-positive patients had antibacterial plus anti-malarial therapy. Moreover, 6 (35.3%) were prescribed antimalarial, while 2 (11.8%) were suggested to have antibacterial only. Similarly, in India there was no noteworthy dissimilarity between the genders. The clinical findings, mainly back pain (42%), large joint pain (40%), rashes (23%), and fever (19%), were found along with 28% of complaints of vomiting and small joint pain. In accordance to a study on CHIKV rashes were frequently found in children of age ≤ 10 years (42%), but 91% of patients 11–20 years of age and 40% of patients 21–30 years of age experienced joint pain and swelling30.

In our study we used Panbio kits, which have good sensitivity and specificity. We ruled out the positivity for Dengue infection through detection of the DENV NS1 antigen alone in 6 patients. In our study, 09 samples tested positive for anti-dengue virus IgM, and 15 patients had NS1 antigen and anti-dengue virus IgM, both representing acute phases of Dengue infection. In viral infections, the algorithm for IgG shows a negative IgG test in the acute phase and a positive IgG test in the convalescent phase of the infection. In addition, the IgG/IgM ratio and high titer study are useful for the secondary Dengue infection. We found IgG only in 05 patients along with anti-dengue virus IgM and IgG, both in 27 samples, suggesting the last period of acute and initial phase of convalescent infection.

We declared Chikungunya infection in 17% (n = 17) of patients. It was evidently found that 11 patients possessed anti-chikungunya IgM only with a history of fever for 8–11 days among 17 CHIKV-infected patients. Though 03 patients having fever for 4–8 days tested positive for Chikungunya virus RNA. Furthermore, 03 patients had anti-chikungunya IgM and CHIKV RNA both, along with 1–3 days of history of fever. We used two sets of primer that have an analytical sensitivity of < 1 PFU, and CHIKV was detected in virus-spiked serum samples at a concentration of 10 PFU/mL (75 µL of serum assayed). Therefore, our protocol was according to the international standard.

We found 6 patients carrying DENV and CHIKV infections simultaneously. According to our literature review, these are the first reported cases of co-infection in Pakistan. Scientifically, it was revealed by the presence of CHIKV RNA and/or anti-chikungunya IgM in combination with NS1 antigen and/or anti-dengue virus IgM. Nevertheless, our results indicate that co-infections might have started as early as 2015; however, these were perhaps not identified due to low diagnostic and diagnostic-related knowledge about Chikungunya20,33. By detecting the presence of CHIKV RNA or anti-chikungunya IgM alongside NS1 antigen or anti-dengue IgM antibodies, this study provides the first clear evidence for arboviral co-infections in Pakistan. Similarly, in our neighboring country, i.e., India, co-infection with DENV and CHIKV was detected in 1.15%32. In another study of 2009, one case was reported with the travel history from Singapore to Taiwan. Both viruses were successfully isolated from the co-infected case by using antibody neutralization and a plaque purification technique.

The finding of co-infections of Dengue and Chikungunya modeled in Pakistan has significant consequences for public health practice. Infections from two or more pathogens add to the clinical manifestations and even result in misdiagnosis and wrong treatment. For example, both DENV and CHIKV cause fever, rash, and joint pain, thus complicating the diagnosis of the two diseases and timely treatment. This can be mitigated by the integration of multiplex diagnostic tools as key diagnostic systems within healthcare facilities for simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens35. The study confirms that the arboviral co-infections are not random but rather are products of residences of the vectors influenced by urbanization, climate change, and water management. Such findings demand a vector-control strategy to address several arboviruses concurrently, which could improve campaign impact.

Previously, Nimmannitya et al.. notified the foremost cases of co-infection in Thailand, who detected four co-infected cases among 150 patients diagnosed with either Dengue or Chikungunya infection. Other studies also showed co-infection: 2.6% in 1962; three co-infected cases out of 144 infected patients (2.1%) in 1963; and 12 co-infected cases out of 334 infected patients (3.6%) in 1964. During 1963–1973, co-infection was also reported in South India, and from 372 cases, 2% presented co-infection of DENV and CHIKV. Recent phylogenetic analysis revealed that the Indian CHIKV is highly related to the Asian genotype responsible for the outburst in Thailand during the same period of time36.

Different studies from Southeast Asia reported DENV and CHIKV co-infection as 6.7% in 1970, 6.2% in 1971, and 4.5% in 1972. Till 2004, no reports were found of DENV and CHIKV co-infection in Asia and Africa. In terms of clinical outcome, we did not find any increase in the intensity among our confirmed cases of co-infection. The similar findings indicated that neither symptoms nor clinical outcome was intensified by co-infection33,37. In contrast, Irekeola et al. illustrated a high rate of severe symptoms and poor clinical outcomes among co-infected patients38. They reported 6 co-infected patients; 2 developed DHF with central nervous system progression, and 1 eventually died. They highlighted that the majority of Dengue infections diagnosed were secondary infections, which may be associated with the observed high rates of severe disease without Chikungunya involvement. Additionally, no minutiae were available regarding the symptom intensity for comparison.

The limitation of our study is the lack of national sero-epidemiological data of CHIKV and the co-infection of DENV and CHIKV to be compared in Pakistan. The study is based on a small number (100) of samples collected mainly from Karachi and a few from Lahore and Hyderabad. A study may be designed to carry out the seroprevalence of CHIKV and its coinfection with DENV at the national level to cover all four provinces. Thus, extensive case-to-case analysis and also research in the field of gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis may be carried out.

Our study also highlighted the significant need for timely surveillance and demographical studies at the national level in Pakistan for other vector-borne infections and infections that remain misdiagnosed/undiagnosed or/and underreported. Response and preparedness are the vital demand and fundamental necessity for the betterment of human and environmental health.

Conclusions

This study showed the circulation of DENV and CHIKV and the presence of both antibodies during 2014–2015 in Pakistan. The study also establishes that co-infection occurs and is a major public health concern, especially in a country where DENV infections seem to reoccur frequently. While the rates of CHIKV may seem lower, the consequences cannot be overestimated because of the common Aedes mosquito; the existing unsatisfactory urban sanitation in Pakistan; and the geographical characteristics of the largest Pakistan cities, such as Karachi and Hyderabad. Co-infections between DENV and CHIKV also appear to increase the risks of severe clinical manifestations and in recognizing the diseases. Surprisingly, there is always the possibility of new CHIKV strains penetrating Karachi, adding to the problem since it is one of the leading trade centers, and transmission is likely to happen across borders through the carriage of goods. In addition, the worldwide emergence of concomitant dual and triple infections of DENV, CHIKV, and Zika virus necessitates the surveillance of these vectors in Pakistan to identify potential Zika virus transmission. These recommendations imply that national and international health organizations should enhance the arboviral surveillance and laboratory-based diagnostic facility in the country. Measures of preparedness are significant as a way of controlling and dealing with the increasing threat of arboviral diseases, and they include vector control, epidemic containment, and adequate and commensurate public health response. Mitigating these challenges early enough will go a long way towards saving lives and eradicating future, deeper, widespread diseases within the region.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Battaglia, V. et al. The worldwide spread of Aedes albopictus: new insights from mitogenomes. Front. Genet. 13, 931163. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.931163 (2022).

Mackenzie, J. S. & Lam, S. K. Human arboviruses in eastern, South-Eastern and Southern asia: A brief history of their isolation and characteristics. Springer Nat. Switz. 313–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22003-6_15 (2023).

Alves, E. D. L. Characterization of the immune response following in vitro Mayaro and Chikungunya viruses (Alphavirus, Togaviridae) infection of mononuclear cells. Virus Res. 256, 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2018.08.011 (2018).

Mehlhorn, H. & Heukelbach, J. Infectious Tropical Diseases and One Health in Latin America. 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99712-0 (Springer, 2022).

Li, Z. et al. The worldwide Seroprevalence of DENV, CHIKV and ZIKV infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15 (4), e0009337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009337 (2021).

Das, B. et al. Aedes: What do we know about them and what can they transmit. In Vectors and Vector-Borne Zoonotic Diseases. Savic, S., (eds). 11–32. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.81363 (Intechopen, 2018).

Liu, X. et al. Dynamics of a climate-based periodic Chikungunya model with incubation period. Appl. Math. Model. 80, 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2019.11.038 (2020).

Umair, M. et al. Genomic characterization of Dengue virus outbreak in 2022 from Pakistan. Vaccines 11 (1), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11010163 (2023).

Ul-Rahman, A. et al. Comparative genomics and evolutionary analysis of Dengue virus strains Circulating in Pakistan. Virus Genes. 60 (6), 603–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-024-02100-8 (2024).

Muhammad, U. et al. Dengue virus: epidemiology, clinical aspects, diagnosis, prevention and management of disease in Pakistan. CABI Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1079/cabireviews.2023.0046 (2023).

Tabassum, S. et al. Year-round Dengue fever in pakistan, highlighting the surge amidst ongoing flood havoc and the COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive review. Annals Med. Surg. 85 (4), 908–912. https://doi.org/10.1097/MS9.0000000000000418 (2023).

Naveed, A. et al. Dengue outbreak in Khyber pakhtoonkhwa, Pakistan 2013. Eur. Acad. Res. 1, 3842–3857 (2014).

Biswal, S. et al. Efficacy of a tetravalent Dengue vaccine in healthy children aged 4–16 years: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 395 (10234), 1423–1433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30414-1 (2020).

Balingit, J. C. et al. Role of pre-existing immunity in driving the Dengue virus serotype 2 genotype shift in the philippines: A retrospective analysis of serological data. Int. J. Infect. Diseases: IJID: Official Publication Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 139, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2023.11.025 (2024).

Awan, S. & Mahmood, F. Ecological parameters and Dengue transmission in karachi, pakistan: an eco-epidemiological analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 101, 227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.030 (2020).

Andrew, A. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for the diagnosis of Chikungunya virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16 (2), e0010152. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010152 (2022).

Carvalho, A. M. D. S. A. & Machado, C. M. Emerging tropical viral infections: Dengue, Chikungunya, and zika. 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01751-4_40-1 (Springer, 2020).

Asaga, M. P. et al. An undetected expansion, spread, and burden of Chikungunya and Dengue cocirculating antibodies in Nigeria. Zoonotic Dis. 4 (3), 201–213. https://doi.org/10.3390/zoonoticdis4030018 (2024).

Saeed, A. et al. Modelling the impact of climate change on Dengue outbreaks and future Spatiotemporal shift in Pakistan. Environ. Geochem. Health. 45 (6), 3489–3505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-022-01429-z (2023).

Shahid, U. et al. Comparison of clinical presentation and out-comes of Chikungunya and Dengue virus infections in patients with acute undifferentiated febrile illness from the Sindh region of Pakistan. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14 (3), e0008086. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008086 (2020).

Riaz, M. et al. Evaluation of clinical and laboratory characteristics of Dengue viral infection and risk factors of Dengue hemorrhagic fever: a multi-center retrospective analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 24 (1), 500. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09384-z (2024).

Clinical Testing and Diagnosis for Chikungunya virus Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/Chikungunya/hcp/diagnosis-testing/index.html (Accessed on 15 May 2024).

Guidelines on Clinical Management of Chikungunya Fever. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-on-clinical-management-of-Chikungunya-fever (Accessed on 27 December 2019).

Clinical Testing Guidance for Dengue. https://www.cdc.gov/Dengue/hcp/diagnosis-testing/index.html (Accessed on 26 August 2024).

Dengue guidelines, for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547871 (Accessed on 21 April 2009).

Mehdi, F. et al. Generation of a large repertoire of monoclonal antibodies against dengue virus NS1 antigen and the development of a novel NS1 detection Enzyme-Linked immunosorbent assay. J. Immunol. (Baltimore Md. : 1950). 209 (10), 2054–2067. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.2200251 (2022).

Darwish, M. A. et al. A sero-epidemiological survey for certain arboviruses (Togaviridae) in Pakistan. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77 (4), 442–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/0035-9203(83)90106-2 (1983).

Aamir, U. B. et al. Outbreaks of Chikungunya in pakistan. The lancet. Infect. Dis. 17 (5), 483. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30191-3 (2017).

Barr, K. L. et al. Evidence of Chikungunya virus disease in Pakistan since 2015 with patients demonstrating involvement of the central nervous system. Front. Public. Health. 6, 186. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00186 (2018).

Badar, N. et al. Emergence of Chikungunya virus, pakistan, 2016–2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26 (2), 307–310. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2602.171636 (2020).

Qureshi, E. M. A. et al. Distribution and seasonality of horizontally transmitted Dengue viruses in Aedes mosquitoes in a metropolitan City lahore, Pakistan. Pakistan J. Zool. 51 (1), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjz/2019.51.1.241.247 (2019).

Swain, S. et al. Distribution of and associated factors for Dengue burden in the state of odisha, India during 2010–2016. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 8 (1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-019-0541-9 (2019).

Mahmood, S. et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of Dengue outbreaks in Samanabad town, Lahore metropolitan area, using Geospatial techniques. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191 (2), 55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-018-7162-9 (2019).

Gupta, A. et al. Prevalence of Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika viruses in febrile pregnant women: an observational study at a tertiary care hospital in North India. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 106 (1), 168–173. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.21-0584 (2021).

Soni, S. et al. Dengue, Chikungunya, and zika: the causes and threats of emerging and Re-emerging arboviral. Dis. Cureus 15 (7), e41717. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.41717 (2023).

Sofyantoro, F. et al. Growth in Chikungunya virus-related research in ASEAN and South Asian countries from 1967 to 2022 following disease emergence: a bibliometric and graphical analysis. Globalization Health. 19 (1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-023-00906-z (2023).

Sharif, N. et al. Molecular epidemiology, evolution and reemergence of Chikungunya virus in South Asia. Front. Microbiol. 12, 689979. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.689979 (2021).

Irekeola, A. A. et al. Global prevalence of Dengue and Chikungunya coinfection: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43,341 participants. Acta Trop. 231, 106408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2022.106408 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors highly appreciate Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for generously providing positive controls for chikungunya virus.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.G. Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing & Visualization K.A.Q. Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, & Visualization F.K. Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing S.F.R. Co-supervision, Project administration & Formal analysis S.G.N. Supervision & Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

Every human participant provided their consent. Clinical trial number: not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guhar, D., Qadir, K.A., Khan, F. et al. A retrospective investigation for the seroprevalence of Chikungunya virus and its co-existence with Dengue virus in Pakistani population, 2014–2015. Sci Rep 15, 34564 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17985-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17985-0