Abstract

The development of new energy vehicles, particularly electric vehicles (EVs) and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (HFCVs), represents a strategic initiative to address climate change and foster sustainable development. Integrating PV with hydrogen production into hybrid electricity-hydrogen energy stations enhances land and energy efficiency but introduces scheduling challenges due to uncertainties. A multi-time scale scheduling framework, which includes day-ahead and intraday optimization, is established using fuzzy chance-constrained programming to minimize costs while considering the uncertainties of PV generation and charging/refueling demand. Correspondingly, trapezoidal membership function and triangular membership function are used for the fuzzy quantification of day-ahead and intraday predictions of photovoltaic power generation and load demands. The system achieves 29.37% lower carbon emissions and 17.73% reduced annualized costs compared to day-ahead-only scheduling. This is enabled by real-time tracking of PV/load fluctuations and optimized electrolyzer/fuel cell operations, maximizing renewable energy utilization. The proposed multi-time scale framework dynamically addresses short-term fluctuations in PV generation and load demand induced by weather variability and temporal dynamics. By characterizing PV/load uncertainties through fuzzy methods, it enables formulation of chance-constrained programming models for operational risk quantification. The confidence level – reflecting decision-makers’ reliability expectations – progressively increases with refined temporal resolution, balancing economic efficiency and operational reliability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transportation is one of the major contributors to carbon emissions in the world. Developing new energy vehicles (NEVs) represents a strategic initiative to address climate change and promote sustainable development1. However, it faces challenges such as lagging infrastructure development. Integrating renewable energy power generation and energy storage into electric vehicles (EVs) charging stations and EV battery swapping stations can significantly enhance the comprehensive benefits of these facilities while reducing indirect carbon emissions caused by power transmission2,3. For hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (HFCVs), utilizing renewable energy to produce hydrogen at hydrogen refueling stations is a clean and efficient approach to harnessing hydrogen energy4,5,6,7. Nevertheless, planning and building EV charging stations or hydrogen refueling stations independently may result in land wastage and low energy supply reliability. Integrating photovoltaic (PV) generation and hydrogen production into the integrated electric-hydrogen energy stations that serve both EVs and HFCVs will improve the utilization efficiency for land and energy.

The low-carbon operation methodology for an integrated hydrogen energy system was proposed in8, and the system’s operating costs and carbon emissions were reduced effectively. The collaborative optimization approach, which smooths load curves and reduces equipment capacity configuration, was developed for integrated energy stations and electric-thermal-cooling networks in9,10,11. The bi-level optimal configuration method, which satisfied the multiple load demands and reduced cost, was introduced for islanded integrated thermal-electric-hydrogen energy systems with economic objectives12. A day-ahead optimal operation strategy was presented in13 for regional integrated energy systems incorporating hydrogen system thermal recovery, thereby improving both energy utilization efficiency and economic performance. However, the scheduling models involved above rely on deterministic optimization, overlooking the dynamic uncertainties of renewable energy generation and ev/hfcv demands. This limitation reduces operational robustness with fluctuations.

In recent years, several optimization methods, including stochastic optimization, robust optimization, and distributionally robust optimization, have been employed to deal with the dynamic uncertainties of renewable energy generation and demands14,15,16,17. The planning model, which optimized investment decision for facilities such as hydrogen pipelines, hydrogen refueling stations, power-to-gas (p2g) devices, and renewable energy generators, for hydrogen supply infrastructure integrated with renewable energy was established in18 to fully leverage the advantages of electric-hydrogen energy station for new energy vehicles in terms of economy and low-carbon performance while enhancing equipment utilization. In19, a two-stage stochastic programming model for the high-temperature electrolysis system under load uncertainty was proposed to investigate the impacts of power fluctuation rate and operation strategy on the optimal capacity. The continuous-time robust unit commitment model incorporating high-resolution wind power uncertainty was formulated in20 to enhance the robustness of dispatch schemes. In21, a day-ahead multi-objective optimal dispatch model for a regional integrated energy system incorporating load and photovoltaic uncertainties was established to optimize the operating cost in day-ahead scheduling. In22, a multi-stage dynamic programming approach for electric-hydrogen coupled microgrids was developed to determine the optimal configuration capacities and the investment timing of equipment, while enhancing the model’s adaptive capability to multiple uncertainties through a hybrid optimization framework. In23, a distributionally robust optimization model for hydrogen refueling stations was developed to establish scheduling solutions that balance conservative and optimistic operational scenarios, while achieving coordinated interaction between refueling stations and upstream power networks. The study further demonstrated that fuzzy optimization can effectively characterize uncertainties under incomplete or uncertain variable information. The above model, while accounting for the impact of uncertainty on scheduling, provides a relatively simplistic consideration of the relationship between time precision and scheduling effectiveness. It primarily relies on fixed time intervals to design the day-ahead scheduling scheme, without delving into the influence of time granularity on scheduling outcomes.

Given the observed characteristic of progressively improved forecasting accuracy for renewable energy generation and load demand with temporal scale refinement, a multi-time scale rolling optimization framework can mitigate the impacts of prediction errors on optimization outcomes. In24, a three-temporal-scale optimization model spanning day-ahead, intra-day rolling, and real-time horizons was developed, incorporating electric-gas-heat-hydrogen demand response and a stepwise carbon emission pricing mechanism. This framework systematically unlocks the flexibility potential of system components while achieving low-carbon system operations through temporal coordination of multi-energy synergies. Considering the impacts of energy and load demand uncertainties on scheduling schemes, a multi-time scale coordinated optimization framework for energy hubs integrating multi-energy flows and heterogeneous energy storage was developed in25. The proposed method effectively reduced the impacts caused by load fluctuations through spatiotemporal coordination of multi-energy complementarity. In26, an optimization model for the microgrid considering multi-time scale energy storage was proposed, incorporating electrical energy storage (ees) and thermal energy storage (tes) as short-term storage mediums with hydrogen energy storage (hes) serving as long-term storage. However, few studies quantify risk-confidence trade-offs in energy scheduling. A fuzzy chance-constrained programming (fccp) model incorporating source-load uncertainty was proposed in27. This methodology enhances dispatch reliability and economic efficiency in integrated energy systems, with operational efficacy substantiated via multi-scenario simulations.

This paper proposes a multi-temporal-scale operational framework for electric-hydrogen energy stations serving new energy vehicles, integrating day-ahead optimization and intra-day rolling optimization through a fuzzy chance-constrained approach. The developed architecture significantly enhances clean energy absorption capacity, then improves economy and reliability in electric-hydrogen energy supply infrastructures. Table 1 compares the proposed method with prior integrated energy scheduling approaches, highlighting key distinctions.

Materials and methods

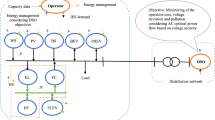

Architecture of an integrated electric-hydrogen energy station

Figure 1 Shows the architecture of an integrated electric-hydrogen energy station for new energy vehicles incorporating photovoltaic generation and hydrogen production-storage systems. The energy station consists of the following functional units: photovoltaic (pv) power generation, electrolyzer, hydrogen storage tank, hydrogen fuel cells, hydrogen refueling dispensers, battery swapping system, and charging piles.

The system achieves energy coupling between electricity and hydrogen through the coordinated operation of electrolysis-based hydrogen production units and fuel cells, enabling the simultaneous provision of electric charging/swapping and hydrogen refueling services for new energy vehicles. The electrical load demands of the electric-hydrogen energy station are primarily satisfied by the output of pv generation and the distribution network. During periods of insufficient pv generation, electricity procurement transactions with external electricity suppliers through the grid are implemented to ensure supply adequacy. Hydrogen loads are fulfilled by hydrogen produced through electrolysis processes and stored in hydrogen storage tanks, with the entire hydrogen production-storage chain specifically dedicated to meeting the hydrogen demand of hfcvs.

Within the integrated energy station, hydrogen production using electrolysis serves as the exclusive source for supplying hydrogen to hfcvs. This integration, coupled with hydrogen storage systems, enables on-site consumption of clean energy sources (e.g., pv) and leverages off-peak electricity pricing to reduce operational costs. During short-term power shortages, such as inclement weather impairing pv generation, grid failures (planned maintenance or unplanned outages), or abnormally high electricity market prices, electrolytic hydrogen production is halted, and fuel cells are activated to prioritize the emergency power supply. This ensures system stability while preventing conflicts in energy allocation.

Analytical model of subsystem

PV generation

The pv generation system serves as the primary on-site electric power generation unit within the integrated electric-hydrogen energy station. Given forecasted solar irradiance and temperature data within the designated station area, the pv output power can be formulated as Eq. (1).

Where, \(P_{{{\text{PVC}}}}^{t}\) denotes the real-time PV power generation (kW), \({P_{{\text{STC}}}}\) represents the rated power generation of PV under standard test conditions (STC) (kW), \(G_{{\text{C}}}^{t}\) specifies the measured solar irradiance during operation (kW/m²), \({G_{{\text{STC}}}}\) indicates the solar irradiance under STC, typically 1 kW/m², \(T_{{\text{C}}}^{t}\) defines the real-time PV cell temperature (°C),\({T_{{\text{STC}}}}\) refers to the reference cell temperature under STC, conventionally 25 °C, \({\beta _{\text{T}}}\) signifies the power temperature coefficient (%/°C), \({\eta _{{\text{PV}}}}\) quantifies the PV system conversion efficiency (%), \(T_{{\text{h}}}^{t}\) characterizes the ambient temperature during operation (°C), \(T_{{\text{C}}}^{t}\) defines the real-time PV cell temperature (°C), \({T_{\text{N}}}\) corresponds to the PV module temperature at STC (°C).

Electrolysis-based hydrogen production

The water electrolysis system generates hydrogen and oxygen by applying direct current (dc) to electrolyzers, following the electrochemical reaction:

2 H₂O → 2 H₂(g) + O₂(g) (electrical energy input)

Due to the negligible thermal energy consumption (typically < 5% of total energy input) compared to the dominant electrical energy demand, the thermal requirements of electrolyzers are neglected in this study. Currently, three predominant electrolyzer technologies exist: proton exchange membrane (pem) electrolyzers, alkaline electrolyzers, and solid oxide electrolyzers. The pem electrolyzer is selected for this hydrogen production system based on its proven technological maturity, rapid start-stop capability, structural simplicity, and high electrolytic efficiency.

The hydrogen production is mathematically formulated as Eq. (2).

Where, \(E_{{{\text{EL}}}}^{t}\) denotes the hydrogen production of the electrolyzer (Nm³), \(P_{{{\text{EL}}}}^{t}\) represents the input electric power of electrolyzer (kW), \(\eta _{{{\text{EL}}}}^{t}\) defines the electrolytic hydrogen production efficiency (%), \({\text{LH}}{{\text{V}}_{{{\text{H}}_2}}}\) is specified as the lower heating value (LHV) of hydrogen, 10.79 MJ/Nm³ under STC, \(\sigma\) corresponds to the energy conversion factor between kW·h and MJ (1 kW·h = 3.6 MJ), \(\Delta t\) quantifies the temporal resolution of the model (h).

The operation efficiency of electrolyzers exhibits a nonlinear relationship with input electric power, which can be approximated as a quadratic function of the per-unit input power, as expressed in Eq. (3).

Where,\({P_{{\text{ELN}}}}\) denotes the rated power of the electrolyzer (kW), and \({\zeta _{{\text{EL,i}}}}\) represents the efficiency coefficient of the hydrogen production.

Fuel cell

The fuel cell can convert stored hydrogen into electrical energy through the electrochemical reaction:

2 H₂(g) + O₂(g) → 2 H₂O(l) + electrical energy

The hydrogen output power of fuel cell is mathematically modeled as Eq. (4), incorporating polarization curve characteristics and thermodynamic constraints.

Where, \(P_{{{\text{FC}}}}^{t}\) denotes the hydrogen output power of the fuel cell (kW), \(E_{{{\text{FC}}}}^{t}\) represents the hydrogen supply from the storage tank to the fuel cell (Nm³), \({\eta _{{\text{FC}}}}\) defines the hydrogen-electric conversion efficiency (%).

The hydrogen-electric conversion efficiency of the fuel cell demonstrates a nonlinear correlation with the output power, which can be approximated as a quintic function of the per-unit output power, as expressed in Eq. (5).

Where, \({P_{{\text{FCN}}}}\) specifies the rated power of the fuel cell(kW), \({\zeta _{{\text{FC}},i}}\) corresponds to the efficiency function coefficient.

Hydrogen storage tank

The hydrogen produced from electrolysis is stored in hydrogen storage tanks, simultaneously fulfilling the hydrogen refueling demand for hfcvs and the hydrogen supply for fuel cells. High-pressure gaseous storage technology, characterized by high storage efficiency and low hydrogen permeation rates, has been widely adopted in hydrogen refueling stations and similar infrastructure applications.

The capacity of the hydrogen storage tank is mathematically formulated as Eq. (6).

Where, \(E_{{{\text{HS}}}}^{t}\) denotes the inventory of the hydrogen storage tank (Nm³), \(E_{{{\text{HFCV}}}}^{t}\) represents the hydrogen refueling demand for HFCVs (Nm³), \({\eta _{{\text{SE}}}}\) defines the hydrogen storage efficiency (%), and \({\eta _{{\text{RE}}}}\) corresponds to the hydrogen release efficiency (%).

Problem formulation

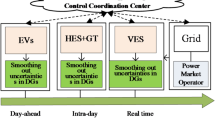

Multi-time scale scheduling for integrated electric-hydrogen energy station

Leveraging the characteristic that forecast accuracy for pv generation and electric-hydrogen loads improves with temporal resolution refinement, a multi-time scale scheduling framework, which incorporates supply-demand balance and relevant operation constraints, is established for integrated electric-hydrogen energy stations. The proposed framework targets minimizing cost and comprises two coordinated phases: day-ahead scheduling and intraday rolling optimization with 15-minute resolution intervals. The multi-time scale scheduling framework is illustrated in fig. 2.

Fuzzy chance constrained programming

Photovoltaic generation and load demands exhibit inherent uncertainty due to weather variability, temporal fluctuation, and other environmental factors. These variables containing uncertainty can be characterized as fuzzy variables through the trapezoidal membership function. This paper employs fuzzy chance-constrained programming to address operational uncertainties in the integrated electric-hydrogen energy station. The fuzzy chance-constrained programming can be expressed as :

Where, \({\varvec{x}}\) denotes the decision vector, \(\varvec{\psi}\) represents the fuzzy vector characterized by trapezoidal membership functions, \(f{\text{(}}{\varvec{x}},\varvec{\psi}{\text{)}}\) defines the objective function, \(g{\text{(}}{\varvec{x}},\varvec{\psi}{\text{)}}\) corresponds to the constraint functions, \({\text{Cr\{ }} \cdot {\text{\} }}\) quantifies the credibility measure of event occurrence, \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) specify the predefined confidence levels set by decision-makers, \({\text{min }}\bar {f}\) represents the pessimistic value of the objective function and is defined as the minimum satisfying the credibility condition \({\text{Cr\{ }}f{\text{(}}{\varvec{x}},\varvec{\psi}{\text{)}} \leqslant \bar {f}{\text{\} }} \geqslant \beta\).

Fuzzy chance-constrained day-ahead scheduling optimization

Objective function

The day-ahead scheduling optimization aims to minimize the total operating costs of the energy station, as formulated in Eq. (8).

Where, \({f_{\text{B}}}\)denotes the total cost under day-ahead scheduling (¥) and superscript I indicates the parameter associated with day-ahead stage, \({f_{{\text{OM,B}}}}\) represents the operation and maintenance cost of energy station equipment (¥), \({f_{{\text{G,B}}}}\) corresponds to the cost of electricity procurement from the grid (¥), \({f_{{\text{CE,B}}}}\) quantifies the carbon emission cost calculated based on real-time carbon intensity factors (¥).

Cost of operation & maintenance

Where, T represents the time intervals in day-ahead stage, \(\Delta t\) represents day-ahead scheduling temporal resolution, \(\tilde {P}_{{{\text{PVC,B}}}}^{t}\)、\(\tilde {P}_{{{\text{EV,B}}}}^{t}\)、\(\tilde {P}_{{{\text{PB,B}}}}^{t}\) denote fuzzy representations of forecasted values for PV power generation (kW), electric vehicle (EV) charging power (kW), and battery swapping power (kW), \(P_{{{\text{EL,B}}}}^{t}\)、\(P_{{{\text{FC,B}}}}^{t}\) denote input power to electrolyzers (kW) and output power from fuel cells (kW), \(E_{{{\text{HS,B}}}}^{t}\) represents inventory of the hydrogen storage tank (Nm³), \({k_{{\text{PV}}}}\)、\({k_{{\text{EL}}}}\)、\({k_{{\text{FC}}}}\)、\({k_{{\text{PB}}}}\)、\({k_{{\text{EV}}}}\)、\({k_{{\text{HS}}}}\) denote the maintain coefficients for PV, electrolyzer, fuel cell, battery swapping station, charging piles, and hydrogen storage tank, respectively, \({k_{{\text{comp}}}}\) denotes the compression factor of hydrogen storage tank.

Cost of electricity procurement

Where, \(P_{{{\text{G}},{\text{B}}}}^{t}\) represents the electricity power of purchase from the grid (kW), \(c_{G}^{t}\) represents the procurement price of electricity (¥/kW·h).

Cost of carbon emission

The energy station generates no direct carbon emissions. However, indirect carbon emissions arise from electricity procurement via transmission with the grid. The corresponding carbon emission costs are formulated as Eq. (11).

Where, \({c_{{\text{coal}}}}\) represents the price of carbon allowance (¥/kgCO₂), \({\lambda _{{\text{coal}}}}\) denotes the grid carbon emission factor (kgCO₂/kW·h).

Constraints

The day-ahead scheduling of integrated energy stations requires compliance with supply-demand equilibrium constraints for both electric power and hydrogen energy, as well as operational constraints of critical equipment.

Equilibrium constraint of electric power

Where, \({\gamma _1}\) represents the confidence level, \({\eta _{{\text{AC/DC}}}}\) denotes the conversion efficiency of the AC-DC converter(%), and \({\eta _{{\text{DC/DC}}}}\)corresponds to the conversion efficiency of the DC-DC converter(%).

Equilibrium constraint of hydrogen energy

Where, \(\tilde {E}_{{{\text{HFCV,B}}}}^{t}\) indicate the fuzzy representation of forecasted values for the hydrogen refueling demand of HFCVs(Nm³).

Operational constraints of equipment

Under standard operation conditions, electrolyzers and fuel cells are subject to mutually exclusive operation. Furthermore, their power outputs must comply with the following constraints:

Where, \({P_{{\text{EL,max}}}}\) denotes the maximum power of hydrogen production of electrolyzers(KW), \({P_{{\text{FC,max}}}}\) represent the maximum power of electric generation of fuel cells(KW), and \(I_{{{\text{EF}}}}^{t}\) is a Boolean variable enforcing mutually exclusive operation constraints between these two systems during identical time periods.

Electrolyzers and hydrogen fuel cells exhibit controllable power output and rapid start-stop capabilities, yet remain subject to the following ramping constraints:

Where, \(R_{{{\text{EL,up}}}}^{{}}\) and \(R_{{{\text{EL,down}}}}^{{}}\) denote the maximum rate of ramp-up and ramp-down for electrolyzers respectively, while \(R_{{{\text{FC,up}}}}^{{}}\) and \(R_{{{\text{FC,down}}}}^{{}}\) represent the corresponding maximum rate of ramp-up rate and ramp-down for fuel cells (kW/h).

The hydrogen storage tank shall comply with the capacity constraint:

Where, \(E_{{{\text{HS,B,min}}}}^{t}\) and \(E_{{{\text{HS,B,max}}}}^{t}\) denote the upper bound and lower bound of tank capacity respectively (Nm³).

Furthermore, the hydrogen storage tank must comply with the storage rate constraint and the release rate constraint:

where \({R_{HS,down}}\) and \({R_{HS,up}}\) represent the maximum storage and release rates of the hydrogen storage tank respectively(Nm³/h).

Fuzzy chance-constrained intraday rolling optimization

Intraday rolling optimization

Under actual operation conditions, the stochasticity, intermittency, and volatility inherent in PV power generation and load demands lead to progressive deterioration of prediction accuracy with extended temporal horizons. Consequently, day-ahead scheduling can only yield coarse dispatch schemes. Such schemes necessitate refinement through intraday optimization with finer temporal resolution (e.g., 15-minute intervals) to mitigate the impact of prediction errors on integrated energy station operations, thereby enhancing both operational reliability and economic efficiency of multi-energy dispatch strategies.

This stage incorporates refined PV generation and load demand prediction errors based on the day-ahead scheme. According to updated forecasting data, the intraday rolling optimization model adjusts hydrogen storage levels, equipment dispatch schedules, and grid purchase quantities. To maintain coherence and stability of the operation scheme across the scheduling horizon, scheme adjustment penalties are integrated into the objective function of cost. The temporal sequence of intraday rolling optimization is illustrated in Fig. 3.

This model executes every 15 min within a 4-hour moving horizon (16 intervals). At the current time t, the integrated electric-hydrogen energy station dynamically adjusts operation schemes for periods \({\text{[}}t+1,t+17{\text{]}}\) based on ultra-short-term PV generation and load demand forecasts reported every 15 min. To mitigate control oscillations caused by repeated adjustments, real-time corrective control is exclusively implemented for the terminal two intervals [t + 16, t + 17] during each optimization cycle. Through continuous backward-rolling optimization, the operational scheme progressively converges to actual operating conditions with enhanced fidelity.

Objective function

The objective function of the intra-day optimization model still aims to minimize the operation cost of the energy station. To encourage the accuracy of the day-ahead schemes and reduce the adjustment of the intra-day optimization, the objective function of the intra-day optimization model adds an adjustment cost term based on the day-ahead scheduling optimization model. The objective function of the intra-day optimization model is

Where, \({f_{\text{I}}}\) denotes the operational costs of the energy station and subscript I indicates parameters associated with intraday optimization, \({f_{{\text{OM,I}}}}\) represents equipment maintenance costs, \({f_{{\text{G,I}}}}\) corresponds to electricity procurement costs, \({f_{{\text{CE,I}}}}\) quantifies carbon emission penalties, \(f_{{\text{R}}}\) captures schedule adjustment penalty. The mathematical expression for these cost components is detailed in Eq. (21).

Where, \(T^{'}\)denotes the number of intraday optimization intervals (\(\ T^{'} = 16\)), \(P_{{EL,I}}^{{t^{'} }}\) and \(P_{{FC,I}}^{{t^{'} }}\)denote the fuzzy representations of forecast values for PV power generation, electric vehicle charging demand, and battery swapping power, respectively, incorporating temporal uncertainty through trapezoidal membership functions, \(P_{{EL,I}}^{{t^{'} }}\) and \(P_{{FC,I}}^{{t^{'} }}\) correspond to electrolyzer input power and hydrogen fuel cell generation power, with operation constraints derived from electrolyzer power fluctuation characteristics, \(E_{{HS,I}}^{{t^{'} }}\)quantifies hydrogen storage levels in pressurized tanks, while \({\lambda _{{\text{R,HS}}}}\)、\({\lambda _{{\text{R,G}}}}\)、\({\lambda _{{\text{R,EL}}}}\)、and \({\lambda _{{\text{R,FC}}}}\) represent dynamic adjustment coefficients for hydrogen storage, grid electricity procurement, electrolyzer input power, and fuel cell generation power.

Constraints

The constraint conditions of the intraday-rolling optimization model align with those established in the day-ahead optimization framework. It should be noted that during the intraday rolling optimization stage, given that the prediction accuracy is already sufficiently high and the current time period is very close to the actual operation period, the confidence level should be set at a relatively large value to reflect the decision-maker’s higher requirements for the reliability of the energy station’s operation plan.

Analytical reformulation of fuzzy chance constraints

Membership function for fuzzy parameters

The fuzzy parameters \({\tilde {\psi }_F}\), representing PV power generation and load demand forecasts, are characterized by trapezoidal membership function as defined in Eq. (22).

Where, \(\mu {\text{(}}{\psi _{\text{F}}}{\text{)}}\) denotes the membership degree, \({\psi _{\text{F}}}\) denotes the forecast values for PV power generation and load demand, \({\psi _{{\text{F1}}}}\)—\({\psi _{{\text{F4}}}}\) define the trapezoidal support intervals that determine the confidence level transition thresholds.

Fuzzy variables and their parametric representation can be formulated as:

Where, \({\varphi _1}\)—\({\varphi _4}\) denote scaling coefficients obtained through historical datasets of PV generation and load demand, \({\psi _{{\text{FC}}}}\)represent the forecast value of the variables.

Triangular membership degeneracy occurs when \({\varphi _2}={\varphi _3}=1\). It means\({\psi _{{\text{F2}}}}={\psi _{{\text{F3}}}}={\psi _{{\text{FC}}}}\), and reflects decision-makers’ heightened confidence in forecast accuracy. Trapezoidal membership function and triangular membership function are shown in Fig. 4.

In this paper, the fuzzification of PV power generation is noted as:

Where, \(P_{{{\text{PVC}}1}}^{t}\)-\(P_{{{\text{PVC4}}}}^{t}\) denote the scaling coefficients obtained through historical datasets of PV generation.

The fuzzification of load demands are noted as:

Where, \(\tilde {P}_{{{\text{EV}}}}^{t}\)represents the fuzzification of electric vehicle charging demand and \(P_{{{\text{EV1}}}}^{t}\)—\(P_{{{\text{EV4}}}}^{t}\) denote their scaling coefficients, \(\tilde {P}_{{{\text{PB}}}}^{t}\)represents the fuzzification of battery swapping power and \(P_{{{\text{PB1}}}}^{t}\)—\(P_{{{\text{PB4}}}}^{t}\) denote their scaling coefficients, \(\tilde {E}_{{{\text{HFCV}}}}^{t}\)represents the fuzzification of hydrogen refueling demand and \(E_{{{\text{HFCV1}}}}^{t}\)—\(E_{{{\text{HFCV4}}}}^{t}\) denote their scaling coefficients.

In view of the feature that the prediction accuracy improves as the time scale shortens, this paper adopts the trapezoidal membership function to fuzzify the day-ahead predictions of PV power generation and load demand and uses the triangular membership function to fuzzify the intra-day predictions.

Analytical reformulation

The crux of solving fuzzy chance-constrained programming lies in effectively processing chance constraints and deriving their deterministic equivalence. The original problem becomes numerically solvable only after converting fuzzy chance constraints into clear equivalence classes through analytical reformulation.

The constraint function is defined as

Where \({h_n}{\text{(}}{\varvec{x}}{\text{), }}n=1,2, \cdots ,N\)are the coefficients of the constraint function, \({\tilde {\psi }_n}\) represents the fuzzy variable characterized by trapezoidal membership parameters.

When the fuzzy attenuation coefficient satisfies \(\alpha>0.5\), the constraint function can be transformed into the following clear equivalence class:

Where,

For example, the equilibrium constraint of electric power given by Eq. (12) can be transformed into its clear equivalence class Eq. (27) through the defuzzification methodology outlined above.

The transformed clear equivalence class model exhibits no essential distinctions from deterministic models. The conversion results for fuzzy chance-constrained expressions containing fuzzy variables in day-ahead and intraday optimization models are detailed in Appendix A.

Linearization of the model

The objective function and constraints of the multi-time-scale optimized operation model constructed above contain nonlinear terms. In order to reduce the difficulty of solving, improve the operational efficiency, and solve it using the existing commercial solver, it is necessary to linearize the nonlinear terms in the model.

For example, the objective function, formula (9), contains an absolute value term and needs to be linearized. By introducing the auxiliary variable \(U_{n}^{t}\)、 \(\delta _{n}^{t}\)、\(\varepsilon _{n}^{t}\) and the constraint condition (3), formula (9) can be equivalently expressed as:

Where, M is a relatively large constant. Other nonlinear expressions in the multi-time-scale optimized operation model can also be linearized similarly.

Results and discussion

Example parameters

An integrated electric-hydrogen energy station incorporating photovoltaic generation and hydrogen production/storage facilities is selected as a case study to validate the effectiveness of the proposed fuzzy chance-constrained multi-time scale optimization scheme.

The integrated electric-hydrogen energy station (shown as Fig. 1.) occupies a total area of 6,000 m², with rooftop photovoltaic deployment restricted to ≤ 37% of the total footprint (2,220 m²). The station has 1,000 photovoltaic panels (1,910 × 1,134 mm), each rated at 450 W. Technical specifications of energy station components are detailed in Table B.1 of Appendix B. Procurement pricing of electricity follows the time-of-use (TOU) tariffs for commercial and industrial users, as specified in Table B.2 of Appendix B.

The day-ahead and intraday forecasting for PV generation and load demands are presented in Fig. C.1 of Appendix C. Significant discrepancies are observed between day-ahead and intraday predictions, with prediction errors quantified in Table 2. Given the inherent uncertainties in PV generation and load demands, these variables are characterized as fuzzy variables with trapezoidal membership functions, whose parameters are detailed in Table 3. A confidence level vector \(\vec {\gamma }=\left[ {{\gamma _1},{\gamma _2}} \right]=\left[ {0.7,0.9} \right]\)is adopted across multiple temporal resolutions.

The case is computationally implemented using the Gurobi solver (v10.0.1) with Python 3.10.

Operation situation analysis

Demand and supply of electricity and hydrogen

The demand-supply situations of the integrated electric-hydrogen energy station about electricity and hydrogen are illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6. It can be revealed from the supply-demand profiles that the multi-timescale optimization enables the integrated energy station to fully satisfy the charging or refueling demands of electric-hydrogen vehicles while maximizing local consumption of renewable energy through electricity-hydrogen coupling mechanisms. During periods of PV generation surplus exceeding electrical load demands, the system dispatches electrolyzers to utilize excess PV generation for hydrogen production, which is stored in hydrogen tanks for refueling applications. Conversely, when PV generation falls short of electrical demands, the IEHS purchases from the grid with a time-of-use (TOU) price. Specifically, during short-term power shortages, such as inclement weather impairing PV generation, grid failures (planned maintenance or unplanned outages), or abnormally high electricity market prices, electrolytic hydrogen production is halted, and fuel cells are activated to prioritize the emergency power supply.

Analysis of scheduling

To further validate the detailed operational adjustments enabled by the multi-time scale optimization methodology for integrated electric-hydrogen energy stations, there are two distinct operational schemes to be implemented for comparative analysis.

Scheme 1: Day-ahead scheduling only.

Scheme 2: Multi-time scale rolling optimization with 15-minute temporal resolution.

The results of optimization scheduling, including PV dispatching, electricity procurement from the grid, input to the electrolyzer, output from the fuel cell, and storage level of the hydrogen tank, are shown in Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11, and costs under both schemes are presented in Table 4.

The comparative analysis demonstrates that light discarding or unwanted power purchases will occur to compensate for the deviation caused by the imprecise time scale if day-ahead scheduling is carried out only. This is because the day-ahead scheme cannot respond in time to the uncertainty of PV generation and load demands caused by weather, time, and other factors. Therefore, the inaccurate scheduling scheme is not conducive to the local consumption of clean energy, nor to reducing the cost of energy stations.

In contrast, Scheme 2 implements intraday rolling adjustments at 15-minute intervals to dynamically refine the day-ahead schedule. This approach effectively tracks short-term fluctuations in PV generation and load demands, enabling precise adjustments to electrolyzer input and fuel cell output. The dynamic coordination between electrolyzers and fuel cells (Figs. 9 and 10) enables adaptive energy conversion across time scales. This bidirectional conversion mechanism transforms PV intermittency into dispatchable resources.

Notably, while the multi-time scale approach introduces additional operation costs due to increased equipment dispatch frequency (e.g., 91.60% higher electrolyzer operating time), the refined intraday adjustments at 15-minute resolution enable precise tracking of short-term PV and load fluctuations. Indeed, by mitigating forecast errors, the multi-time scale rolling optimization scheme minimizes peak-time electricity purchases (from ¥1563.30 to ¥1104.49 during TOU peak periods) and improves the utilization rate of PV. Excitedly, the increase in operation costs is far lower than the decline in curtailed electricity procurement. Consequently, the multi-time scale scheduling optimization achieves a 29.37% reduction in carbon emissions and 17.73% lower annualized costs compared to Scheme 1. It stems from two synergistic effects: (1) Intraday adjustments avoid peak electricity purchases (Fig. 8) through hydrogen-to-power conversion; (2) Carbon cost savings are achieved by reducing grid dependence during high-emission periods.

These significant improvements confirm the critical importance of addressing uncertainties and utilizing multi-time scale coordination highlighted in previous works14,15,16,17,20,21,22, 27. Specifically, the dynamic tracking of short-term fluctuations enabled by our intraday rolling optimization echoes the effectiveness of similar approaches proposed in24,25,26, demonstrating tangible economic and environmental benefits. These results directly demonstrate that the FCCP-based multi-time scale framework effectively resolves the scheduling challenges posed by PV/load unpredictability, as initially hypothesized in Sect. 1. Specifically, the real-time tracking capability illustrated in Figs. 9, 11 validates the core premise that dynamic electrolyzer/fuel cell coordination can transform uncertainty management into economic and environmental gains.

Furthermore, compared to the deterministic optimization models applied to similar infrastructure in8,12,13 the FCCP-based multi-time scale scheduling explicitly incorporates and manages prediction error attributed to the uncertainties (Table 2), leading to more robust and cost-effective operation, as evidenced by the reduced curtailment and peak electricity purchases shown in Figs. 7, 8.

The effect of confidence level

The confidence level indicates both the magnitude of uncertainty in forecasting PV generation and load demands, as well as the expected degree of satisfaction of fuzzy chance constraints. Consequently, setting the confidence level to increase with decreasing time scales allows for reflecting the time-variant characteristics of forecasting errors about PV generation and loads and the expectations of the decision-maker. The effect of confidence level on system operating costs is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5 provides quantitative validation for the economy-reliability trade-off hypothesis proposed in Sect. 1. It shows that an equilibrium mechanism between economy and reliability depends on the appropriate setting of confidence levels. During the intraday rolling optimization phase, an elevated confidence level reflects the heightened expectations of decision-makers regarding the operational reliability of power stations. It should be emphasized that the refinement process in 15-minute ahead scheduling will escalate system reserve requirements due to enhanced reliability constraints, thereby increasing operating costs and compromising the economic efficiency of power station operations.

The analysis of the confidence level’s impact (Table 5) extends the findings of27 by demonstrating the practical trade-off mechanism between economy and operational reliability within the specific context of a multi-time scale scheduling framework for electric-hydrogen stations. The progressive increase in confidence level \(\gamma\) with finer temporal resolution reflects the time-variant characteristics of forecasting errors and provides decision-makers with a quantifiable lever to balance risk and cost, an aspect less explored in general fuzzy optimization studies.

Limitations and future research

Fixed efficiency for electrolyzers/fuel cells (Sect. 2.2) neglects degradation effects for large-hour operation. Long-term simulations suggest this may overestimate economic profits by 12–15%.

Furthermore, the FCCP-based scheduling assumes static TOU electricity prices during intraday optimization (Sect. 3.4), which cannot capture real-time market volatility. Sensitivity analysis indicates this simplification may reduce economic benefits by 5–8% during extreme price fluctuations. Future work will integrate reinforcement learning for dynamic price adaptation.

Conclusion

This paper addresses the economic and low-carbon operation of integrated electric-hydrogen energy stations (IEHSs) for NEVs and overcomes operational uncertainties via a novel multi-time scale framework. While studies like24,25,26 have explored multi-time scale optimization in integrated energy systems, the work significantly extends this concept by formulating a fuzzy chance-constrained programming (FCCP) model specifically tailored for the uncertainties inherent in integrated electric-hydrogen stations serving both EVs and HFCVs. This novel framework, combining multi-time scale rolling optimization with credibility-based uncertainty characterization (Sect. 3), allows for explicit operational risk quantification. The proposed FCCP-based multi-time scale framework significantly extends previous deterministic optimization efforts and uncertainty-handling methods by providing a robust and adaptable solution tailored for the operational uncertainties in integrated electric-hydrogen stations.

The results confirm the substantial economic and environmental benefits achievable through dynamic multi-time scale optimization leveraging electrolyzer/fuel cell flexibility, aligning with and quantitatively substantiating the value propositions highlighted in works like27. Practically, the dynamic coordination of electrolyzers and fuel cells enables real-time balancing of PV fluctuations, reducing grid dependency during peak hours (Table 4). This mitigates grid congestion risks while the hydrogen storage offers ancillary service potential and supports decarbonizing transport infrastructure. Future studies will explore integration with large-scale smart grids.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- NEVs:

-

New energy vehicles

- EVs:

-

Electric vehicles

- HFCVs:

-

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles

- PV:

-

Photovoltaic

- P2G:

-

Power-to-gas

- PEM:

-

Proton exchange membrane

- EES:

-

Electrical energy storage

- TES:

-

Thermal energy storage

- HES:

-

Hydrogen energy storage

- IEHS:

-

Integrated electric-hydrogen station

- STC:

-

Standard test conditions

- LHV:

-

Lower heating value

- DA:

-

Day-ahead

- TOU:

-

Time-of-use

- FCCP:

-

Fuzzy chance-constrained programming

References

The State Council. Notice of the issuance of the development plan for the new energy vehicle industry (2021–2035) 2020-11-02. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2020-11/02/content_5556716.htm

Yang, M. et al. Comprehensive benefits analysis of electric vehicle charging station integrated photovoltaic and energy storage. J. Clean. Prod. 302, 126967 (2021).

Yang, L. & Ribberink, H. Investigation of the potential to improve DC fast charging station economics by integrating photovoltaic power generation and/or local battery energy storage system[J]. Energy 167, 246–259 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Review on key technologies of hydrogen generation, storage and transportation based on multi-energy complementary renewable energy. Trans. China Electrotechnical Soc. 36 (03), 446–462 (2021).

Zhang, W., Maleki, A. & Nazari, M. A. Optimal operation of a hydrogen station using multi-source renewable energy (solar/wind) by a new approach. J. Energy Storage. 53, 104983 (2022).

Abdin, Z. & Mérida, W. Hybrid energy systems for off-grid power supply and hydrogen production based on renewable energy: A techno-economic analysis. Energy. Conv. Manag. 196, 1068–1079 (2019).

Xing, X. et al. Modeling and operation of the power-to-gas system for renewables integration: a review. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 4 (2), 168–178 (2018).

Deng, J. et al. Low-carbon optimized operation of integrated energy system considering electric-heat flexible load and hydrogen energy refined modeling. Power Syst. Technol. 46 (05), 1692–1704 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Energy station-network collaborative planning with flexible load. J. Electr. Eng. 17 (02), 176–186 (2022).

Nourollahi, R. et al. Peak-Load management of distribution network using conservation voltage reduction and dynamic thermal rating. SUSTAINABILITY 14 (18), 11569 (2022).

Nourollahi, R. et al. Hybrid robust-CVaR optimization of hybrid AC-DC microgrid. In: 11th Smart Grid Conference. (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Optimal configuration of CHHP Island IES considering different charging modes of electric vehicles. Power Syst. Technol. 46(10), 3869–3880 (2022).

Luo, X. et al. A day-ahead dispatching method of regional integrated electric-hydrogen energy systems considering the heat recycle of hydrogen systems. Trans. China Electrotechnical Soc. 38 (23), 6359–6372 (2023).

Xu, H. & Li, H. Planning and operation stochastic optimization model of power systems considering the flexibility reformation. Power Syst. Technol. 44 (12), 4626–4638 (2020).

Xu, C. et al. Distributionally robust optimal dispatch method considering mining of wind power statistical characteristics. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 46 (02), 33–42 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. An uncertainty hydro/PV/load typical scenarios generating method based on deep embedding for clustering. Proceedings of the CSEE. 40(22): 7296–7306. (2020).

Tan, C. et al. Multi-time scale operation optimization of EHHGS considering equipment uncertainty and response characteristics. J. Clean. Prod. 382, 135106 (2023).

Gan, W. et al. Multi-network coordinated hydrogen supply infrastructure planning for the integration of hydrogen vehicles and renewable energy. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 58 (2), 2875–2886 (2021).

Qi, R. et al. Two-stage stochastic programming-based capacity optimization for a high-temperature electrolysis system considering dynamic operation strategies. J. Energy Storage. 40, 102733 (2021).

Zhou, B. et al. Continuous-time modeling based robust unit commitment considering beyond-the-resolution wind power uncertainty. Trans. China Electrotechnical Soc. 36 (07), 1456–1467 (2021). (in Chinese).

Wang, J. et al. Multi-objective optional day-ahead dispatching for regional integrated energy system considering uncertainty. Power Syst. Technol. 42 (11), 3496–3506 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Multi-stage dynamic programming method for hydrogen-electric coupled microgrid considering multiple uncertainties. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 43 (12), 77–83150 (2023).

Yuan, T. et al. Synergistic optimal operation of electricity-hydrogen systems considering hydrogen refueling loads for fuel cell vehicles. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 47 (05), 16–25 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Multi-time scale low-carbon operation optimization strategy of integrated energy system considering electricity-gas-heat-hydrogen demand response. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 43 (01), 16–24 (2023).

Cheng, S. et al. Multi-time scale coordinated optimization of an energy hub in the integrated energy system with multi-type energy storage systems. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 47, 101327 (2021).

Dong, H. et al. Low carbon optimization of integrated energy microgrid based on life cycle analysis method and multi-time scale energy storage. Renew. Energy. 206, 60–71 (2023).

Qiu, G. et al. Fuzzy optimal scheduling of integrated electricity and natural gas system in industrial park considering source-load uncertainty. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 42 (05), 8–14 (2022).

Funding

This research is supported by Science and Technology Project of State Grid Jibei Electric Power Company Limited (B30185240003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZHOU Lixia and LI Hao wrote the main manuscript text. BO Bo and YANG Po carried on the case study. JIAO Dongxiang and ZHAO Shengqi performed the data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

The clear equivalence class of the operation & maintenance cost formula (9).

The clear equivalence class of equilibrium constraint of electric power Eq. (12).

The clear equivalence class of equilibrium constraint of hydrogen energy Eq. (13).

Appendix B

Appendix C

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Bo, B., Yang, P. et al. Multi-time scaling optimization for electric station considering uncertainties of renewable energy and EVs. Sci Rep 15, 34579 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18051-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18051-5