Abstract

About 30% of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) cases are negative on MRI, so quantitative diagnosis based on clinical symptoms becomes challenging. There is an urgent need for an accurate and reliable method to differentiate patients with MRI-negative TLE from healthy individuals. This study aimed to explore the use of machine learning methods to diagnose MRI-negative TLE patients based on single and combined resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) metrics. This study investigates the diagnostic implications of using both singular and composite resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) indices in patients with MRI-negative TLE. We carried out a retrospective analysis of the clinical data and rs-fMRI data of 90 patients with MRI-negative TLE and 90 healthy controls (HCs). Next, the participants were divided into a training set and a test set at 8:2. Functional indices extracted from each brain region included degree centrality (DC), voxel-mirrored homotopic connectivity (VMHC), regional homogeneity (ReHo), fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF), and amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF). A two-sample t-test was utilized to select significant voxels. After this, classification models based on individual rs-fMRI indices and combined rs-fMRI indices were constructed using ML algorithms such as support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), and logistic regression (LR) on the training set. Model performance was evaluated using metrics such as specificity, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), sensitivity, and accuracy, and validations were performed on the test set. Lastly, the feature contribution was assessed using Shapley Additive explanations (SHAP) values. The SVM model employing a combination of rs-fMRI functional indices had optimal performance. On the test set, this model achieved an AUC of 0.89, with an accuracy rate of 82%, where the ALFF values from the cerebellum contributed most significantly to the model. In contrast, ML models based on individual rs-fMRI indices demonstrated inferior classification performance, whereas the RF model using the DC index had the lowest accuracy of 47% on the test set. The SVM model combining the fMRI indices has the greatest potential to distinguish between MRI-negative temporal lobe epilepsy patients and healthy individuals, suggesting a complementary role for the classification of resting-state fMRI indices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Epilepsy ranks among the most prevalent and debilitating chronic neurological disorders worldwide, affecting more than 70 million individuals globally, primarily characterized by recurrent episodes of abnormal neuronal discharges1,2. Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), the leading type of focal epilepsy in adults, exhibits significant resistance to pharmacological treatments and often necessitates further evaluation and surgical interventions3. It is noteworthy that approximately 30% of patients with TLE do not exhibit lesions in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a condition referred to as MRI-negative temporal lobe epilepsy (MRI-NTLE)4. Consequently, epileptic foci are difficult to precisely localize, and it is challenging to formulate diagnostic and therapeutic plans. This adversely affects patients’ life quality and survival, which imposes a significant societal and health burden. In this context, it is necessary to develop more accurate and objective methods for diagnosing MRI-NTLE.

With the advancement of artificial intelligence, ML has an ascendancy in diagnosing, understanding the pathogenesis, and predicting the prognosis of neuropsychiatric disorders5. ML has robust medical diagnostic functional metrics that offer more effective predictions. These capabilities not only allow for the detection of spatial distributions in neuroimaging data but also facilitate the differentiation between individuals with neuropsychiatric disorders and healthy controls (HCs) at a personal level6,7,8. SVMs, a typical ML model, demonstrate strong classification performance and interpretability for multivariate and high-dimensional complex data5. Additionally, the random forest (RF) and logistic regression (LR) models are important for solving classification problems in neuroimaging studies.

Studies have shown that combining SVM with the surface area of the region of interest and cortical thickness has a detection accuracy of 83% for temporal lobe epilepsy9. Both Spitzer et al.10and Yang et al.11 have also developed diagnostic models using structural MRI data, which provide strong support for identifying epilepsy with subtle epileptogenic foci. In recent years, machine learning research based on structural MRI data has made significant progress in the field of epilepsy diagnosis. However, most prior studies on rs-fMRI for epilepsy focused on single functional metrics or structural MRI integration, and comprehensive diagnostic models combining multi-dimensional rs-fMRI indices for MRI-negative TLE remain underexplored. rs-fMRI is a non-invasive neuroimaging technique. It can measure blood oxygenation changes to reflect connectivity between brain regions12,13. The amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF) mainly reflects the level of spontaneous neural activity in the brain14,15,16, while the amplitude score of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF) is an optimization of the ALFF value, which can further improve the specificity and sensitivity of detecting spontaneous neural activity in local brain regions17,18,19. Singh et al.20 found that the brain regions significantly activated by ALFF were mainly located in the executive control network and the default mode network. ReHo reflects the changes in the coordination of neuronal activity in local brain regions21,22. Studies have shown that ReHo values in the precuneus of MRI-NTLE patients are significantly lower, suggesting that epilepsy may affect the synergistic work of localized functional modules in the brain23. VMHC reflects the pattern of information integration and communication between the right hemispheres24, and in previous studies, VMHC-altered brain regions in TLE patients have been found to have a strong association with the directional functional connectivity of multiple brain regions, suggesting that epilepsy may disrupt the functional balance between the left and right hemispheres functional balance25,26,27. DC quantifies the strength of a node by summing the total number of connections to that node, indicating the functional connectivity within the brain network28. These indices, each with distinct characteristics and advantages, provide multifaceted reflections of brain function, which could help the identification and assessment of MRI-NTLE patients. Therefore, we will extract multiple functional indicators of ALFF, fALFF, ReHo, VMHC, and DC for each brain region as features based on an automated anatomical labeling atlas29.

In this study, based on individual and combined rs-fMRI indices, we constructed and tested classification models using SVM, RF, and LR classifiers. This study aims to investigate whether rs-fMRI indices combined with ML can differentiate MRI-NTLE patients from healthy subjects and whether a composite of rs-fMRI indices can aid in classification by providing more comprehensive information. Furthermore, this study assesses the contribution of the rs-fMRI functional index to the classification process.

Materials and methods

90 patients with MRI-NTLE who were seen at our Epilepsy Center from January 2019 to April 2024 were covered. An HC group comprised 90 individuals recruited from our health screening center, totaling 180 participants. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for MRI-NTLE patients were as follows: (1) All epilepsy diagnoses conformed to the diagnostic standards of the International League Against Epilepsy30, primarily based on ictal electroencephalography (EEG) showing epileptiform discharges, clinical manifestations, and medical history. (2) No history of neuropsychiatric disorders or intracranial space-occupying lesions. (3) No evidence of past alcohol or drug misuse. (4) Exclusion of patients with incomplete scan data or poor scan quality. The inclusion criteria of the healthy control group were as follows: (1) No contraindications to MRI examination; (2) Good compliance and cooperation in the examination; (3) No history of neurological or psychiatric disorders or intracranial space-occupying lesions; (4) No history of alcohol and drug abuse. (5) Age and gender were matched with the MRI-NTLE group. Each participant or their relative was briefed on the study specifics and consented formally by signing. Our institution’s Clinical Trials Ethics Committee approved the study.

The basic demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. In this study, the MRI-NTLE patients and the HC did not have notable differences in educational level, age, and gender (P > 0.05). The average duration of illness for the MRI-NTLE patients was 10.52±8.911 years. About 48.9% of the patients in the MRI-NTLE group had bilateral seizures, and about 53.3% of the patients had generalized seizures.

MRI scanning parameters

MRI data for all participants were collected using a GE SIGNA Architect 3.0T scanner with a 48-channel head coil. Lying supine, participants had their heads fixed in place using foam or sponge pads to prevent any head movement. While being scanned, participants were instructed to maintain wakefulness, avoid moving, close their eyes, relax, and avoid any mental activity as much as possible. The rs-fMRI scans utilized a gradient-echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following parameters: slice thickness = 4 mm, matrix = 64 × 64, field of view (FOV) = 240 mm × 240 mm, flip angle (FA) = 90°, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms, no gap, with 36 slices covering 240 time points. A three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence was used to capture the T1-weighted structural images, with parameters: matrix = 256 × 256, FA = 8°, TE = 2.38 ms, FOV = 240 mm × 240 mm, TR = 2400 ms, slice thickness = 1 mm, no gap, comprising 156 slices.

Data preprocessing

Data preprocessing of rs-fMRI was performed using the DPARSF 4.5 software package on a MATLAB 2020a platform (http://rfmri.org/DPARSF). The specific steps included: (1) Format conversion; (2) the first 10 time points removed to mitigate the effects of initial MRI signal instability; (3) Time correction to ensure consistent acquisition start times for each voxel; (4) Motion correction, excluding participants with head movement exceeding 3 mm or rotation beyond 3 degrees; (5) Coregistration of structural images with functional images followed by segmentation into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid using DARTEL; (6) Normalization of images to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space and resampling voxel size to 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm; (7) Nuisance covariate regression, including Friston-24 parameters and signals from white matter and cerebrospinal fluid; (8) A 4 mm Gaussian kernel was used for spatial smoothing, which effectively suppressed the effects of physiological noise and instrumental noise, integrated the signals between neighboring voxels, reduced random fluctuations in the data, and improved the signal-to-noise ratio. Referring to previous studies, the 4 mm Gaussian kernel is especially suitable for functional signal analysis of structures such as the temporal lobe and cerebellum27,31,32; (9) Detrending and band-pass filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz) for reducing the impacts exerted by high-frequency noise and low-frequency drift.

Feature selection

Based on the automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlas, we extracted five resting-state functional metrics from 90 brain regions across the cerebral cortex and subcortical structures, yielding 450 features in total29.

Each rs-fMRI measure was calculated as follows: (1)ALFF was calculated as the square root of the average power spectrum within the 0.01–0.08 Hz band for each voxel. (2)fALFF is the ratio of the power of low-frequency fluctuations (0.01–0.08 Hz) within a voxel to the total power across all frequencies, normalized by the square root of the number of frequency points. (3)ReHo assesses the local synchrony of neuronal activity by calculating Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (KCC) among time series of neighboring voxels within a 26-voxel sphere. (4)VMHC measures the functional connectivity between symmetric regions of the left and right hemispheres. For each voxel, the Pearson correlation coefficient between its time series and that of its mirror voxel in the opposite hemisphere was calculated, followed by spatial averaging. (5)DC quantifies the number of functional connections a brain region has with others within the whole-brain network. In DPARSF, DC was calculated by summing the Pearson correlation coefficients between each voxel’s time series and those of all other voxels, followed by spatial averaging within AAL regions.

It has been shown that dealing with features with high dimensionality and redundancy tends to lead to model overfitting33,34. Thus, feature selection was crucial for improving model performance.

The entire dataset was randomly partitioned into training and test sets at an 8:2 ratio in each iteration. We used the same training set to select features and train the classifier. The test set was used to verify the performance of the classification model. Following that, a two-sample t-test was conducted on the training set to select features with a significance level of P < 0.05 for further analysis. The two-sample t-test classifies features based on the computed t-values, eliminating those with weaker discriminative power to enhance classifier performance13. Subsequently, principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to perform dimensionality reduction on the selected features, thereby further reducing the complexity of the data and enhancing the efficiency of analysis and the interpretability of the results35. In 100 iterations of 8:2 segmentation, PCA was fitted only on the training set features, and the resulting principal component projection matrix was applied to the training and test sets, ensuring that no test set data affected the PCA parameters. Additionally, PCA was performed independently for each iteration to enhance model robustness across different data subsets. For individual rs-fMRI metrics, features were selected following the above steps. For the combined indicators, the features of all five indicators were combined, a t-test was performed, and then dimension reduction was performed by PCA. This approach ensures that single-indicator specificity and cross-indicator complementarity are preserved.

Model construction and evaluation

To optimize model parameters, leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) was applied within the training set during grid search, which means leaving one subject out as the testing data, and the others as the training data36,37. Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel was chosen for its effectiveness in handling non-linearly separable neuroimaging data, as validated in prior epilepsy studies. For the SVM model, the kernel function was predefined as radial basis function (RBF), and grid search was applied to optimize its hyperparameters: gamma (kernel coefficient) and C (regularization strength). The search ranges for gamma and C were set as [(0.0001, 1, 100)] and [(0.0001, 10, 100)], respectively. (The range of hyperparameter settings for the grid search strategy is detailed in Supplementary File 1. The hyperparameter values for the SVM, RF, and LR models are provided in Supplementary File 2).

The performance of each model is comprehensively evaluated by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, and by plotting the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Models with an AUC value closer to 1 are considered to perform better. Additionally, the statistical significance of the model performance is tested through 1000 random permutation tests to assess whether the AUC and accuracy are significantly higher than random values. Finally, the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) method is used for interpretation and visualization. SHAP values are calculated by combining features and determining the contribution of each feature to different combinations, thereby measuring each feature’s contribution to the model’s predictive outcomes38,39. Higher SHAP values indicate a greater contribution to model predictions. All training and testing of ML processes are implemented using the “scikit-learn” package on the Anaconda3 platform (http://www.anaconda.com)40.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (version 26.0) was employed for statistical analyses. Demographic data were analyzed to examine differences between the MRI-NTLE group and the HC group in terms of gender, age, and educational attainment. Differences were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test, independent samples t-test, or Chi-square test, with a significance level set at P < 0.05.

Results

Performance of classification models based on rs-fMRI indices

Table 2 displays the AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of the models based on rs-fMRI indices. Figure 1 illustrates the ROC curves for the three classification models tested on the validation set. All ROC curves were generated using the scikit-learn roc_curve function with default parameters, without additional smoothing. The results indicated that the ML models utilizing combined rs-fMRI indices outperformed those using individual indices, with higher accuracy, AUC, sensitivity, and specificity values. Specifically, the SVM model based on combined rs-fMRI indices exhibited the best performance, with an AUC of 0.98 and an accuracy of 99% on the training set, and an AUC of 0.89 and an accuracy of 82% on the test set. In contrast, classification models based on individual rs-fMRI indices achieved AUC values ranging from 0.53 to 0.79 on the test set. For instance, the model combining the DC index with the RF algorithm showed the lowest accuracy and specificity of 47% and 0.44, respectively, while the model combining ALFF with RF and the model combining fALFF with RF exhibited the lowest sensitivity at 0.35.

ROC Curves of the Three Classification Models in the Test Set. (Note: ALFF, Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuations; fALFF, Fractional Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuations; ReHo, Regional Homogeneity; VMHC, Voxel-Mirrored Homotopic Connectivity; DC, Degree Centrality; SVM, Support Vector Machine; RF, Random Forest; LR, Logistic Regression. ROC curves were plotted based on true labels and model-predicted probabilities in the same 36-case test set. LR models showed relatively smooth curves due to their linear probability estimation, while SVM/RF curves reflect non-linear decision boundaries and ensemble effects without post-processing.)

Feature contribution

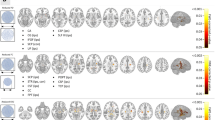

To evaluate the significance of differences in the top 20 features between the two groups, this study first computed the mean absolute SHAP values to determine feature importance. Subsequently, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was employed for intergroup comparisons of individual features. To address the issue of multiple comparisons, the Benjamini-Hochberg method was applied for false discovery rate correction. The results demonstrated that all top 20 features exhibited adjusted P-values < 0.05 after correction, indicating statistically significant differences between MRI-negative temporal lobe epilepsy patients and healthy controls. These findings suggest these features possess robust discriminative power for distinguishing between the two cohorts. The SHAP values for the SVM model based on integrated rs-fMRI indices are illustrated in Fig. 2. The top 20 contributing brain regions are depicted in Fig. 3. To comprehensively understand the selected features, this study employed SHAP values to interpret the importance of features. Relative to the other features extracted, the ALFF value of the cerebellum_3 region had the highest average SHAP value, indicating that this region may have the greatest potential for distinguishing between MRI-NTLE patients and HCs. Additionally, the DC values of the cerebellum_6, the ALFF values of the cuneus, and the VMHC values of the superior temporal gyrus also played important roles in the predictive accuracy of the classification model.

Feature Contributions in the SVM Model Based on Integrated rs-fMRI Indices.(Left: The mean absolute values of SHAP values for each feature. Right: The SHAP values for each feature across individual samples, where each line represents a feature and each dot represents a sample. The horizontal axis indicates the SHAP value).

Discussion

In clinical practice, the diagnosis of MRI-NTLE posed significant challenges due to the absence of detectable structural abnormalities on conventional MRI. Traditional diagnostic approaches were prone to misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis, often resulting in delayed or ineffective therapeutic interventions for patients41. Although advancements in neuroimaging and ML have facilitated progress in epilepsy research, studies specifically targeting MRI-NTLE remained scarce, highlighting an urgent need for reliable diagnostic methodologies. As far as we know, this study was the first to utilize a multi-level rs-fMRI indices approach combined with various ML models to differentiate between MRI-NTLE patients and HCs. We found that ML models based on integrated rs-fMRI indices perform better than those using a single rs-fMRI index, and a single rs-fMRI index cannot provide sufficient information to distinguish between MRI-NTLE patients and healthy individuals. The combined indicators complement each other from the four levels of “activity intensity, local coordination, hemisphere symmetry, and network center”. This multi-dimensional integration can more comprehensively cover the diffuse network abnormalities of MRI-NTLE, rather than the local changes of a single lesion. In addition, combined indicators can reduce the bias of single indicators through multi-dimensional feature averaging, provide a richer feature space, and enable the model to learn more essential pathological patterns. This suggests that combining the five sets of functional indices(ALFF, fALFF, ReHo, VMHC, and DC)provides a more comprehensive representation of the intrinsic functional changes in the brain.

At present, only a few studies have attempted to use brain imaging data combined with ML techniques for MRI-NTLE diagnosis. For example, Bennett et al.42 used multimodal MRI data, including T1, T2, and FLAIR, as input features. They trained a random forest classification model that demonstrated the distinctive abnormal patterns differentiating MRI-NTLE patients from positive TLE patients. Additionally, Yang et al.11 extracted morphological features including surface area, cortical thickness, and gray matter volume. They found that using an extreme learning machine significantly improved the identification of MRI-NTLE, achieving an accuracy of 92.79%. In a more recent study, researchers proposed using diffusion kurtosis imaging data input into an SVM model to identify epilepsy characteristics, achieving an accuracy rate as high as 95.24%43. Recently, certain researchers utilized independent component analysis to extract features from rs-fMRI data for the diagnosis of temporal lobe epilepsy, attaining an accuracy rate of 97.5%. Notwithstanding, in these studies, an independent test dataset was conspicuously absent. This deficiency potentially introduced biases during the model evaluation phase, as it could have led to an overestimation of the model’s performance. However, in these studies, an independent test dataset was absent, which may introduce biases during the model evaluation phase. In contrast, we have meticulously established separate training and test models. This effectively mitigates the risk of model overfitting, thus rendering the results more objective and reliable.

In this study, the classification performance of three models using a single rs-fMRI index was generally mediocre. Among them, the performance of the model based on ReHo was superior to that based on ALFF, fALFF, VMHC, and DC. Moreover, models utilizing integrated rs-fMRI indices outperformed those based on a single index. Previous studies have demonstrated that the ReHo directly correlates with the synchrony of spontaneous neural activity during resting-state conditions and exhibits an association with regional glucose metabolic rates44. This evidence suggests that ReHo may demonstrate superior sensitivity compared to other functional indicators in detecting aberrant neural activity associated with neurological dysfunction. rs-fMRI is a powerful imaging technique that can accurately reflect spontaneous neural activity in the brain during rest13,45. ALFF, fALFF, and ReHo are three reliable for functional metrics that quantify neural activity. They can delineate the brain into functionally specific regions14,17,21. Recent studies have demonstrated that ALFF, fALFF, and ReHo exhibit diagnostic sensitivity comparable to fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and specificity similar to video-electroencephalography (VEEG) in focal epilepsy46. Furthermore, Yang et al.47have proposed that these three metrics provide divergent perspectives on pathophysiological processes and play complementary roles in interpreting localized spontaneous neural activity. VMHC and DC primarily focus on the functional connectivity between different brain regions24,28. Wu et al.48 reported that the functional coordination between homotopic regions in the brains of TLE patients was impaired, suggesting that VMHC could potentially serve as a neuroimaging biomarker for guiding the diagnosis of TLE patients. Additionally, scholars like Song et al. proposed that the combined application of multiple rs-fMRI indices could more comprehensively unveil the abnormal neuronal activities and cognitive function impairments in MRI-NTLE patients49. Furthermore, some scholars conducted research based on multiple rs-fMRI indices from perspectives such as the changes in brain activities in unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy50, the differences in brain activities between left and right-sided temporal lobe epilepsy26, and the differences in brain activities between hippocampal sclerosis and MRI-NTLE51. They discovered that each rs-fMRI index reflected different aspects of brain activities and these indices had complementary effects. Currently, an increasing number of studies have been integrating rs-fMRI indices to enhance classification performance. This approach has been applied to the research of various neuropsychiatric disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease52,53, Parkinson’s disease54,55, and obsessive-compulsive disorder38,56. The results of this study provide a highly valuable theoretical framework for subsequent comprehensive research on the diagnosis of MRI-NTLE, which contributes to a better understanding of the underlying neurophysiological and compensatory processes driving MRI-NTLE.

In this study, the performance of the SVM is markedly superior to that of the LR and RF models. When a large number of features are present, SVM can effectively mitigate the impact of highly correlated noisy features. It is particularly well-suited for high-dimensional and complex datasets, as well as non-linear binary classification tasks57. This suggests that the consistent advantage of SVM over LR and RF is attributed to two interrelated factors: its theoretical applicability to high-dimensional small-sample data and the nonlinear representation ability of the RBF kernel. To address the “black box” issue in ML models and increase their transparency and credibility, we employed SHAP analysis58. This method quantifies the contribution of each feature to the model’s predictions. In the SVM model based on integrated rs-fMRI indices, the cerebellum was the most influential feature, where the ALFF of cerebellum_3 and DC of cerebellum_6 had the largest SHAP values. Traditionally considered a regulator of motor behavior, the cerebellum also influences non-motor functions such as attention, language, memory, and emotion59. This finding aligns with growing evidence that the cerebellum plays a pivotal role in epilepsy beyond motor control, involving three interrelated mechanisms. First, the cerebellum-hippocampus circuit dysfunction may underlie MRI-NTLE pathogenesis. Rondi-Reig60 and Froula J.M. et al.61 found a bidirectional dynamic functional connection between the cerebellum and the hippocampus. Our result of increased cerebellar ALFF may indicate a compensatory response to hippocampal dysfunction, though further metabolic imaging is needed to validate this hypothesis. The cerebellum can suffer acute damage from TLE episodes, leading to emotional disturbances. Research has shown that abnormal changes in cerebellar neurons and atrophic changes during TLE episodes significantly impact the development of epilepsy62,63. Second, the cerebellum’s elevated DC suggests its transformation into a hub of abnormal functional connectivity. Hao et al.64 also suggested that significant changes in the cerebellar region of TLE patients might be associated with recurrent epileptic discharges. This highlights the cerebellum’s considerable role in TLE and indicates that the bidirectional functional connection between TLE and the cerebellum could be a driving factor in epileptic episodes. This is consistent with our SHAP analysis, where cerebellar DC contributed to model predictions alongside ALFF, indicating combined effects of excitability and connectivity abnormalities. Third, the cerebellum’s role in interhemispheric balance may be disrupted in MRI-NTLE. Shi et al. found reduced VMHC in the superior temporal gyrus of TLE patients, reflecting interhemispheric dyssynchrony. Although our study focused on the cerebellum, the co-occurrence of cerebellar ALFF elevation and temporal pole VMHC changes suggests a network-level disturbance involving both cerebellar hyperexcitability and hemispheric functional imbalance.

Notably, the cerebellar findings in our study challenge the traditional view of MRI-NTLE as a purely temporal lobe disorder, highlighting instead a distributed network pathology. The cerebellum’s dual role in motor and non-motor functions may explain why its functional alterations correlate with both seizure control and quality of life in MRI-NTLE patients.

Limitations and prospects

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively limited, increasing the risk of overfitting. Future studies should expand the sample size and conduct multicenter collaborative studies. Second, the current study is mainly based on rs-fMRI data. Combining rs-fMRI with other neuroimaging techniques and clinical data can be explored in the future. Multimodal data fusion can provide information about brain structure, function, and metabolism from multiple dimensions, which can help to understand the pathological mechanisms of MRI-NTLE more comprehensively and improve the accuracy and specificity of diagnosis. Third, the cross-sectional design of this study could not reveal the disease process of MRI-NTLE and the long-term effects of therapeutic interventions on brain function. Future studies could conduct a longitudinal study with long-term follow-up of patients to observe changes in their rs-fMRI indexes over time. Fourth, the choice of a 4 mm smooth kernel in this study is the optimal trade-off based on the current voxel resolution of 3 mm, but there are still shortcomings. In the future, rs-fMRI data with higher spatial resolution should be used, and a 2-3 mm small kernel can be tried to further improve the detail capture ability of cerebellar subregions. At the same time, the ‘adaptive smoothing’ algorithm can be combined to adjust the kernel size based on the brain region structure to achieve more accurate noise suppression. In addition, sensitivity analysis of the model results for different kernel sizes was not included in this study, and this validation will be supplemented later to enhance the robustness of the conclusions. Finally, Common antiepileptic drugs, such as valproate and carbamazepine, may affect low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF/fALFF) and functional connectivity (VMHC/DC) by regulating neuronal excitability. The heterogeneity of drug use among patients in this study was low (mainly two drugs), but in subsequent studies, sensitivity analysis should be performed to exclude patients with specific drugs to verify the robustness of the results, and drug dose and duration should be included to further control the influence.

Conclusion

In summary, using comprehensive rs-fMRI indices can more thoroughly reveal abnormal changes in brain regions and improve diagnostic accuracy. Firstly, the approach combining comprehensive rs-fMRI indices with various ML algorithms shows promising potential in distinguishing MRI-NTLE patients from HC, providing preliminary support for ML-assisted diagnosis of MRI-NTLE. Secondly, abnormal cerebellar neural activity plays a significant role in the diagnosis of MRI-NTLE. The ALFF value of the cerebellum could serve as a neuroimaging biomarker for distinguishing MRI-NTLE, offering objective guidance for future diagnosis and treatment of MRI-NTLE.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because we still have further research to do. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to LY, 2515204692@qq.com.

References

Asadi-Pooya, A. A. & Farazdaghi, M. Clinical characteristics of MRI-negative Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. Acta Neurol. Belg. 123 (5), 1911–1916 (2023).

Löscher, W. et al. Drug resistance in epilepsy: clinical impact, potential mechanisms, and new innovative treatment options [J]. Pharmacol. Rev. 72 (3), 606–638 (2020).

GUO, D. et al. Altered Temporal variations of functional connectivity associated with surgical outcomes in Drug-Resistant Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. Front. Neurosci. 16, 840481 (2022).

Muhlhofer, W. et al. MRI-negative Temporal lobe epilepsy-What do we know? [J]. Epilepsia 58 (5), 727–742 (2017).

Handelman, G. S. et al. eDoctor: machine learning and the future of medicine [J]. J. Intern. Med. 284 (6), 603–619 (2018).

Lao, Z. et al. Morphological classification of brains via high-dimensional shape transformations and machine learning methods [J]. Neuroimage 21 (1), 46–57 (2004).

Orrù, G. et al. Using support vector machine to identify imaging biomarkers of neurological and psychiatric disease: a critical review [J]. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 36 (4), 1140–1152 (2012).

Yang, N. et al. Diagnostic identification of chronic insomnia using ALFF and FC features of resting-state functional MRI and logistic regression approach [J]. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 406 (2023).

Gleichgerrcht, E. et al. Artificial intelligence for classification of Temporal lobe epilepsy with ROI-level MRI data: A worldwide ENIGMA-Epilepsy study [J]. Neuroimage Clin. 31, 102765 (2021).

Spitzer, H. et al. Interpretable surface-based detection of focal cortical dysplasias: a Multi-centre epilepsy lesion detection study [J]. Brain 145 (11), 3859–3871 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Automated detection of MRI-negative Temporal lobe epilepsy with ROI-based morphometric features and machine learning [J]. Front. Neurol. 15, 1323623 (2024).

Khosla, M. et al. Machine learning in resting-state fMRI analysis [J]. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 64, 101–121 (2019).

Teng, J. et al. Brain disease research based on functional magnetic resonance imaging data and machine learning: a review [J]. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1227491 (2023).

Zang, Y. F. et al. Altered baseline brain activity in children with ADHD revealed by resting-state functional MRI [J]. Brain Dev. 29 (2), 83–91 (2007).

Ameen Fateh, A. et al. Static and dynamic changes in amplitude of Low-Frequency fluctuations in patients with Self-Limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (SeLECTS): A Resting-State fMRI study [J]. J. Clin. Neurosci. 129, 110817 (2024).

Jin, B. et al. Functional profile of perilesional Gray matter in focal cortical dysplasia: an fMRI study [J]. Front. Neurosci. 18, 1286302 (2024).

Zou, Q. H. et al. An improved approach to detection of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) for resting-state fMRI: fractional ALFF [J]. J. Neurosci. Methods. 172 (1), 137–141 (2008).

Li, X. et al. Altered spontaneous brain activity as a potential imaging biomarker for generalized and focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures: A resting-state fMRI study [J]. Epilepsy Behav. 140, 109100 (2023).

Chen, L. C., Li, X. & Shen, L. Self-limited focal epilepsy decreased regional brain activity in sensorimotor areas [J]. Acta Neurol. Scand. 143 (2), 188–194 (2021).

Singh, T. B. et al. The assessment of brain functional changes in the Temporal lobe epilepsy patient with cognitive impairment by Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging [J]. J. Clin. Imaging Sci. 10, 50 (2020).

Zang, Y. et al. Regional homogeneity approach to fMRI data analysis [J]. Neuroimage 22 (1), 394–400 (2004).

Xu, H. et al. Neurovascular coupling changes in patients with magnetic resonance imaging negative focal epilepsy [J]. Epilepsy Behav. 138, 109035 (2023).

Huang, H. et al. Abnormalities of regional brain activity and executive function in patients with Temporal lobe epilepsy: A cross-sectional and longitudinal resting-state functional MRI study [J]. Neuroradiology 66 (7), 1093–1104 (2024).

Zuo, X. N. et al. Growing together and growing apart: regional and sex differences in the lifespan developmental trajectories of functional homotopy [J]. J. Neurosci. 30 (45), 15034–15043 (2010).

Shi, K. et al. Impaired interhemispheric synchrony and effective connectivity in right Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. Neurol. Sci. 45 (5), 2211–2221 (2024).

Song, C. et al. Similarities and differences of dynamic and static spontaneous brain activity between left and right Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. Brain Imaging Behav. 18 (2), 352–367 (2024).

Pang, L. et al. Disruption of Cerebellar-Cerebral functional connectivity in Temporal lobe epilepsy and the connection to Language and cognitive functions [J]. Front. Neurosci. 16, 871128 (2022).

Zuo, X. N. et al. Network centrality in the human functional connectome [J]. Cereb. Cortex. 22 (8), 1862–1875 (2012).

Tzourio-Mazoyer, N. et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain [J]. Neuroimage 15 (1), 273–289 (2002).

RINEY, K. et al. International league against epilepsy classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset at a variable age: position statement by the ILAE task force on nosology and definitions [J]. Epilepsia 63 (6), 1443–1474 (2022).

Jarrahi, B. The Influence of Spatial Smoothing Kernel Size on the Temporal Features of Intrinsic Connectivity Networks [J]. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, 2021: 3165–3168. (2021).

Chen, Z. & Calhoun, V. Effect of Spatial smoothing on task fMRI ICA and functional connectivity [J]. Front. Neurosci. 12, 15 (2018).

Chen, C., Weiss, S. T. & Liu, Y. Y. Graph convolutional network-based feature selection for high-dimensional and low-sample size data [J]. Bioinformatics 39(4), 1–7 (2023).

Salerno, S. & Li, Y. High-Dimensional survival analysis: methods and applications [J]. Annu. Rev. Stat. Appl. 10 (1), 25–49 (2023).

Okbay, A. et al. Polygenic prediction of educational attainment within and between families from genome-wide association analyses in 3 million individuals [J]. Nat. Genet. 54 (4), 437–449 (2022).

Xiao, P. et al. Using histogram analysis of the intrinsic brain activity mapping to identify essential tremor [J]. Front. Neurol. 14, 1165603 (2023).

Shi, D. et al. Classification of parkinson’s disease using a region-of-interest- and resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging-based radiomics approach [J]. Brain Imaging Behav. 16 (5), 2150–2163 (2022).

Huang, F. F. et al. Functional and structural MRI based obsessive-compulsive disorder diagnosis using machine learning methods [J]. BMC Psychiatry. 23 (1), 792 (2023).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions [J]. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 1–10 (2017).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python [J]. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Liu, G. et al. Minireview of epilepsy detection techniques based on electroencephalogram signals [J]. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 15, 685387 (2021).

Bennett, O. F. et al. Learning to see the invisible: A data-driven approach to finding the underlying patterns of abnormality in visually normal brain magnetic resonance images in patients with Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. Epilepsia 60 (12), 2499–2507 (2019).

Kang, L. et al. Identifying epilepsy based on machine-learning technique with diffusion kurtosis tensor [J]. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 28 (3), 354–363 (2022).

Nugent, A. C. et al. The relationship between glucose metabolism, resting-state fMRI BOLD signal, and GABAA-binding potential: a preliminary study in healthy subjects and those with Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 35 (4), 583–591 (2015).

Smith, S. M. et al. Resting-state fMRI in the human connectome project [J]. Neuroimage 80, 144–168 (2013).

Chen, Z. et al. The value of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging for detecting epileptogenic zones in patients with focal epilepsy [J]. PLoS One. 12 (2), e0172094 (2017).

Yang, F. et al. A study of spontaneous brain activity on Resting-State functional magnetic resonance imaging in adults with MRI-Negative Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. Neuropsychiatr Dis. Treat. 18, 1107–1116 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. The decreased connectivity in middle Temporal gyrus can be used as a potential neuroimaging biomarker for left Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. Front. Psychiatry. 13, 972939 (2022).

Song, C. et al. More than just statics: static and Temporal dynamic changes in intrinsic brain activity in unilateral Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 16, 971062 (2022).

Song, C. et al. Static and Temporal dynamic alteration of intrinsic brain activity in MRI-negative Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. Seizure 108, 33–42 (2023).

Song, C. et al. Comparision of spontaneous brain activity between hippocampal sclerosis and MRI-negative Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. Epilepsy Behav. 157, 109751 (2024).

Khatri, U. & Kwon, G. R. Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and biomarker analysis using Resting-State functional MRI functional brain network with Multi-Measures features and hippocampal subfield and amygdala volume of structural MRI [J]. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 818871 (2022).

Bolla, G. et al. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of resting-state fMRI driven machine learning algorithms in the detection of mild cognitive impairment [J]. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 22285 (2023).

Pang, H. et al. Use of machine learning method on automatic classification of motor subtype of parkinson’s disease based on multilevel indices of rs-fMRI [J]. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 90, 65–72 (2021).

Long, D. et al. Automatic classification of early parkinson’s disease with multi-modal MR imaging [J]. PLoS One. 7 (11), e47714 (2012).

Bu, X. et al. Investigating the predictive value of different resting-state functional MRI parameters in obsessive-compulsive disorder [J]. Transl Psychiatry. 9 (1), 17 (2019).

Tsai, C. A. & Chang, Y. J. Efficient selection of Gaussian kernel SVM parameters for imbalanced data [J]. Genes (Basel) 14(3), 583 (2023).

Rodríguez-Pérez, R. & Bajorath, J. Interpretation of machine learning models using Shapley values: application to compound potency and multi-target activity predictions [J]. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 34 (10), 1013–1026 (2020).

Argyropoulos, G. P. D. et al. The cerebellar cognitive affective/schmahmann syndrome: a task force paper [J]. Cerebellum 19 (1), 102–125 (2020).

Rondi-Reig, L., Paradis, A. L. & Fallahnezhad, M. A liaison brought to light: Cerebellum-Hippocampus, partners for Spatial cognition [J]. Cerebellum 21 (5), 826–837 (2022).

Froula, J. M., Hastings, S. D. & Krook-Magnuson, E. The little brain and the seahorse: Cerebellar-hippocampal interactions [J]. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 17, 1158492 (2023).

Krook-Magnuson, E. et al. Cerebellar directed optogenetic intervention inhibits spontaneous hippocampal seizures in a mouse model of Temporal lobe epilepsy [J]. eNeuro 1(1), ENEURO.0005-14.2014 (2014).

Marcián, V. et al. Morphological changes of cerebellar substructures in Temporal lobe epilepsy: A complex phenomenon, not Mere atrophy [J]. Seizure 54, 51–57 (2018).

Hao, S. et al. Distinguishing patients with Temporal lobe epilepsy from normal controls with the directed graph measures of resting-state fMRI [J]. Seizure 96, 25–33 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by Science and Technology Department of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Grant:#2023TSYCLJ0027), “Tianshan Talents” Key Talent Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Young Talent Promotion Fund Project (Grant number: # 2024TSYCQNTJ0050), Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Natural Science Foundation Science Fund project (Grant: #2022D01C774), and The 2022 “Youth Scientific Research Sailing” Special Fund of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University (Grant: #2022YFY-QKQN-86).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LY and HK contributed equally.LY wrote the manuscript and handled the data and statistical analysis. HK participated in data acquisition and interpretation of the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. LJ and YW contributed to the conception, design, and implementation plan of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was authorized by the Medical Research Ethics Board of First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and all subjects provided written informed consent forms.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, L., Kukun, H., Wang, Y. et al. Identify MRI negative temporal lobe epilepsy with resting fMRI indicators and machine learning techniques. Sci Rep 15, 40421 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18146-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18146-z