Abstract

Existing research indicates that bicalutamide and zoladex show significant potential in treating prostate cancer. However, in the clinical application of treating benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), it is limited due to relatively severe side effects, and the specific mechanism of action has not been fully studied. This research aimed to identify and validate key genes linked to the effects of bicalutamide and zoladex in BPH, potentially guiding the development of targeted therapeutic strategies. BPH-related datasets were retrieved from publicly available databases (|log2FC| > 0.5, p value < 0.05). Initially, intersection genes were identified by overlapping results from differential expression analysis (comparing BPH and control groups) with the target genes of bicalutamide and zoladex, which were sourced from database searches. Key genes were then pinpointed using protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, machine learning algorithms (SVM-RFE and Random Forest), and gene expression analyses (IHC, immunohistochemical). To explore the biological mechanisms underlying these genes, functional enrichment (GO, KEGG and GSEA) molecular docking analyses were performed, construction of lncRNA miRNA mRNA molecular regulatory network, transcription factor (TFs) regulatory network, SNPs analysis, and disease prediction. Validation of gene expression levels was conducted through IHC analysis of clinical samples. The study identified NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD as critical genes associated with BPH, all showing significantly reduced expression in BPH samples. These genes were notably co-enriched in the “oxidative phosphorylation” pathway. Moreover, CLPP, HMGCR, and NQO1 exhibited strong binding affinities with bicalutamide and zoladex. Specifically, the NQO1-bicalutamide interaction had a binding energy of -10.8 kcal/mol, while the NQO1-zoladex interaction demonstrated a binding energy of -38.05 kcal/mol. IHC analysis revealed significantly higher expression levels of NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD in the treated group compared to the untreated group. This study underscores NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD as potential therapeutic targets for BPH, offers mechanistic insights into the efficacy of bicalutamide and zoladex and provides novel insights into potential therapeutic strategies for patients with BPH. However, attention should still be paid to the control of side effects in their clinical application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common urological disorder affecting middle-aged and elderly men, characterized by the non-malignant proliferation of prostatic glandular and stromal cells, resulting in prostate enlargement1. This enlargement can compress the urethra, causing bladder outlet obstruction and leading to lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), which encompass both storage symptoms (e.g., increased urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia) and voiding symptoms (e.g., weak urine stream, hesitancy, dysuria)2,3. BPH is strongly age-dependent, with histological evidence of hyperplasia observed in approximately 50% of men aged 51–60, rising to 90% in those over 804,5,6. As the global population ages, BPH has become a major public health concern affecting male health7. Beyond diminishing quality of life through symptoms like nocturia and social limitations, BPH can lead to serious complications such as acute urinary retention, recurrent urinary tract infections, bladder stones, and potentially hydronephrosis8. In advanced cases, chronic obstruction can result in hydronephrosis and renal dysfunction9.

Current treatments for BPH include pharmacological management and surgical intervention10. First-line pharmacological options involve α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists (e.g., tamsulosin) and 5α-reductase inhibitors (e.g., finasteride)11. α1-blockers provide rapid symptom relief by relaxing prostate smooth muscle but may cause dizziness or orthostatic hypotension12. In contrast, 5α-reductase inhibitors reduce prostate volume over time but are associated with a higher risk of sexual dysfunction, including erectile dysfunction and decreased libido13,14. Surgical options, particularly transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), remain the gold standard but are not without risks and postoperative complications4,15. Current treatments largely focus on symptom management rather than halting disease progression. Both pharmacological and surgical approaches carry distinct side effects or complications. Therefore, there is a pressing need to develop safer and more effective therapeutic strategies, especially those that can fundamentally reverse the hyperplastic process. The pathogenesis and progression of BPH are multifactorial, primarily involving hormonal imbalances (such as abnormal dihydrotestosterone activity), chronic inflammation, and changes in the interactions between prostate stromal and epithelial cells16.

Bicalutamide (a non-steroidal anti-androgen) and goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) are commonly employed in clinical prostate cancer (PCa) treatment protocols17. Although these two drugs are mainly used in the treatment of prostate cancer, their core action targets and related pathways also play a key regulatory role in the pathological process of BPH. Previous studies have illustrated the potential therapeutic connection between these drugs and BPH18,19. BPH is a urinary system disease with a relatively high incidence among middle-aged and elderly men, and its pathogenesis is closely related to the dysregulation of the androgen signaling pathway6. Researchers have already applied anti-androgen strategies to treat and alleviate BPH20. For example, Kim et al. improved BPH in rats by regulating androgen receptor signaling through Cinnamomum cassia and Rosa21. Although the exact mechanism by which androgens influence BPH remains to be elucidated, there is sufficient data linking androgens and the androgen receptor pathway to BPH22. Bicalutamide exerts its effects by selectively antagonizing the androgen receptor, whereas goserelin lowers testosterone levels by inhibiting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, a mechanism that could potentially regulate the pathological progression of BPH18,23. Notably, emerging evidence suggests that BPH and PCa may share common transcriptional regulators and signaling pathways, providing a foundational theoretical framework for investigating the molecular mechanisms of BPH within the context of bicalutamide- and goserelin-based therapies24. Network pharmacology, an interdisciplinary field that integrates systems biology, bioinformatics, and traditional pharmacology, offers a comprehensive approach to analyze the multi-target, synergistic effects of drugs. It can accurately predict potential adverse effects25 and establish a scientific basis for expanding drug indications by constructing a multidimensional “drug-target-disease-pathway” interaction network.

This study utilized transcriptomic data relevant to BPH from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, in conjunction with target genes of bicalutamide and zoladex identified through public data searches. Through differential expression analysis, protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis, machine learning, and gene expression analysis, key genes (Genes with significant expression differences (P < 0.05) and consistent expression patterns in both datasets) linked to the effects of bicalutamide and zoladex in BPH were identified. Functional analysis, correlation analysis, regulatory network analysis, and molecular docking were then performed to further investigate the potential mechanisms in patients with BPH. Finally, immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis was carried out to validate the expression of key genes in clinical samples. Collectively, these analyses provide novel insights into potential therapeutic strategies for patients with BPH.

Materials and methods

Data collection

In this study, BPH-related datasets were obtained from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Specifically, the GSE7307 dataset (platform: GPL570) provided transcriptomic data from 7 BPH tissue samples and 12 control tissue samples (samples derived from human prostate tissue), while the GSE132714 dataset (platform: GPL16791) contained transcriptomic data from 18 BPH tissue samples and 4 control tissue samples26. Robust Multi-array Analysis (RMA) was used for background correction, normalization, and data polishing.

Differential expression analysis

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between BPH and control samples in the GSE7307 dataset were identified using the “limma” package (v 3.54.1)27, with the criteria of |log2 fold-change (FC)| > 0.5 and P < 0.05. A volcano plot and heatmap were generated to visualize the DEGs. The volcano plot, created using the “ggplot2” package (v 3.3.6)28, displayed all DEGs, with the top 10 up-regulated and down-regulated genes labeled according to their log2 FC, ranked from highest to lowest. The heatmap, generated using the “ComplexHeatmap” package (v 2.14.0)29, focused on the top 10 up-regulated and down-regulated genes.

Function analysis of intersection genes and identification of candidate genes

In the present study, the chemical structures of bicalutamide and zoladex were retrieved from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and saved in SDF format. To identify the target genes of these drugs, the PharmMapper database (http://www.lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/) and the Universal Protein Resource database (UniProt, https://www.uniprot.org/) were utilized. Human protein targets were selected, with the number of returned targets set to 300.

The target genes of bicalutamide and zoladex were then intersected with the DEGs to identify common genes associated with BPH, using the “VennDiagram” package (v 1.7.3)30. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were performed to explore the biological functions and pathways of these common genes, using the “clusterProfiler” package (v 4.6.2)31 (P < 0.05). A PPI network was constructed to examine interactions among the intersection genes, employing the STRING database (https://string-db.org/) with a confidence score threshold of ≥ 0.4. After removing outlier genes, the resulting PPI network was visualized using Cytoscape (v 3.9.1)32.

Subsequently, the Stress and Betweenness algorithms in the cytoHubba plug-in for Cytoscape were applied to assess the importance of each node in the PPI network. The top 30 genes identified by each algorithm were selected and overlapped as candidate genes for further analysis.

Machine learning

Based on these candidate genes, the Support Vector Machine Recursive Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE) and Random Forest (RF) algorithms were applied to the GSE7307 dataset to further identify feature genes. The SVM-RFE method iterates in the process of gradually reducing the combination of all input genes to a single gene combination. In each iteration, it calculates the importance ranking, removes the less important genes, and then re-ranks the importance using the remaining genes. This cycle is repeated to obtain the importance of each gene, as well as the error rate and accuracy rate (calculated as (true positives + true negatives) / total number of samples) of the combination in each iteration. The point with the lowest error rate is selected as the optimal combination. The SVM-RFE algorithm was implemented using the “caret” package (v 6.0.93)33, with 5-fold cross-validation employed to optimize the model and minimize error. The Random Forest (RF) method uses Gini, i.e., Gini index, to calculate the impact of each variable on the heterogeneity of observations at each node of the classification tree, thereby comparing the importance of variables. The larger this value, the greater the importance of the variable. Simultaneously, the RF algorithm was executed using the “randomForest” package (v 4.7–1.1)34, selecting genes based on their importance value exceeding the median. The intersection of genes identified by both SVM-RFE and RF was determined using the “ggvenn” package (v 0.1.9) (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggvenn), which facilitated the identification of feature genes.

Determination and function analysis of the key genes

To identify key genes associated with BPH, gene expression analyses were performed on feature genes from both the GSE7307 and GSE132714 datasets, comparing BPH and control samples. The Wilcoxon test was applied to evaluate the significance of gene expression differences, with a threshold of P < 0.05. Genes demonstrating significant expression differences (P < 0.05) and consistent expression patterns across both datasets were designated as key genes for BPH. The results were visualized using the “ggplot2” package (v 3.3.6).

To further explore the biological functions and signaling pathways of these key genes, functional enrichment analysis was conducted using the GSE7307 dataset. First, Spearman correlation coefficients between the key genes and other genes were calculated and ranked (from high to low) using the “psych” package (v 2.2.9)35. The background gene set “c2.cp.kegg.v7.4.symbols.gmt” was sourced from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB, http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was then performed using the “clusterProfiler” package (v 4.6.2), with a significance threshold set at |Normalized Enrichment Score (NES)| > 1 and P < 0.05. The top five enriched pathways were identified and ranked by P-value, from lowest to highest. These pathways were visualized using the “enrichplot” package (v 1.18.3)36.

GeneMANIA (https://genemania.org/) was employed to identify genes functionally related to the key genes, and a gene-gene interaction (GGI) network was constructed.

Comprehensive analysis of key genes: interaction, functional similarity, subcellular localization, and chromosomal distribution

To better understand the interaction relationships among key genes, Spearman correlation analysis was conducted using the GSE7307 dataset, with the criteria of a |correlation coefficient (cor)| > 0.30 and P < 0.05. The functional similarity between key genes was assessed using the “GOSemSim” package (v 2.24.0)37, with a similarity score threshold of 0.5.

To investigate the subcellular localization of the proteins encoded by these key genes, data from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) were utilized. This resource provides detailed information on protein sequences and functional annotations, including subcellular localization predictions38. Additionally, the chromosomal distribution of key genes was analyzed using the “RCircos” package (v 1.2.2)39.

Regulation network analysis

To elucidate the molecular regulatory mechanisms of the key genes, two distinct regulatory networks were constructed. First, microRNAs (miRNAs) targeting the key genes were predicted using two databases: miRDB (http://www.mirdb.org/) and miRanda (http://mirtoolsgallery.tech/mirtoolsgallery/node/1055). Key miRNAs were identified by overlapping predictions from both databases. Subsequently, the starBase database (https://rnasysu.com/encori/) was used to predict long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that targeted the key miRNAs. These relationships were integrated to construct a comprehensive lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network. Additionally, the NetworkAnalyst database (https://www.networkanalyst.ca/NetworkAnalyst/) was employed to predict transcription factors (TFs) targeting the key genes, and a TF-mRNA regulatory network was established.

Both the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA and TF-mRNA regulatory networks were visualized using Cytoscape (v 3.9.1). Finally, network centrality analysis was performed using the cytoHubba plugin in Cytoscape to explore how these regulators influence or prioritize key genes in the network.

Integrated analysis of SNP variations, disease associations, and molecular Docking for key genes

To assess the impact of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on key genes, variations within these genes were analyzed using the Rare Disease Data Center (RDDC, https://rddc.tsinghua-gd.org/zh). Additionally, the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD, https://ctdbase.org/) was employed to identify diseases associated with the key genes. For each key gene, the top 20 related diseases were selected based on inference scores, ranked from highest to lowest, to construct a key gene-disease network.

To further validate the binding potential of bicalutamide and zoladex to the key genes, molecular docking analysis was conducted. The protein crystal structures of the key genes (acting as receptors) were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/), while the 3D molecular structures of the drugs (acting as ligands) were sourced from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Molecular docking was performed using CB-Dock (http://clab.labshare.cn/cb-dock/php/blinddock.php), and the binding energies were calculated. A binding energy below − 5.0 kcal/mol generally indicates a strong affinity between the drug and the key gene, suggesting effective molecular interaction.

Immunohistochemical (IHC)

To validate the expression of key genes in clinical samples, IHC analysis was performed. A total of 10 tissue samples were collected from the Affiliated BenQ Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. These included 5 samples from non-intervention normal patients with BPH (untreated group) and 5 samples from patients with PCa treated with bicalutamide and zoladex (treated group). The untreated group tissue samples from patients with suspected prostate cancer were obtained through prostate needle biopsies. After pathological diagnosis confirmed prostate cancer, BPH tissues were identified and selected from these biopsy samples by two independent pathologists, as not all sampled tissue cores contained carcinoma. The treated group patients diagnosed with clinically significant malignancies received 3 months of neoadjuvant therapy (bicalutamide 50 mg po qd + goserelin 10.8 mg ih 12w). Only one patient experienced the side effect of excessive sweating. Post-therapy BPH tissue specimens were subsequently acquired via laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. All participants provided informed consent, and the study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, receiving approval from the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University Affiliated BenQ Hospital (AF-42-2.0). Initially, tissue samples from both groups were carefully washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove any residual debris. They were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 to 48 h to preserve cellular structure. After fixation, the samples underwent dehydration using a graded ethanol series (75–100%), clearing with xylene to remove any alcohol, infiltration with paraffin, and embedding into paraffin blocks for sectioning. The sections were cut to a uniform thickness of 3 μm.

For the IHC assay, tissue sections were first baked at 64 °C for 1 h to ensure adherence to the slides. The sections were then dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated through a graded ethanol series (100–70%), and subjected to antigen retrieval using a citrate buffer solution to expose epitopes for enhanced antibody binding. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min to prevent nonspecific staining. The sections were sealed with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37 °C for 30 min to block nonspecific antibody binding. Primary antibodies (listed in Supplementary Table S1) were diluted in 2% BSA and incubated with the sections overnight at 4 °C for specific antigen binding. After washing, a reaction enhancer was applied to amplify the signal, followed by incubation with anti-mouse IgG polymer at 37 °C for 30 min. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used for color development, and the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for 5 min for contrast. Finally, the tissue sections were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (70–100%), cleared with xylene, and mounted with neutral gum for long-term storage and analysis. Details of the experimental reagents used are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Whole-slide scanning and analysis were performed to evaluate staining results. Image analysis was conducted using ImageJ-pro-plus software (v 6.0)40, and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (v 10.1.2)41. A significance threshold of P < 0.05 was applied to determine statistical significance. Blinded scoring was performed for the IHC results: statistics were conducted by 3 analysts, with the final result taking the average value. Grading criteria for expression levels: statistical analysis of staining positivity rate. Quantitative analysis of IHC images: after calculating the positive area using ImageJ software, it was normalized to relative expression values.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using R software (v 4.2.2). Differences between groups were assessed using the Wilcoxon test (P < 0.05). The significance levels were set as follows: ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, and ns represented not significant.

Results

Acquisition of 25 candidate genes for BPH

Differential expression analysis identified 10,148 DEGs, with 21 genes up-regulated and 10,127 down-regulated in BPH samples (Fig. 1a-b). In addition, we used the PharmMapper and UniProt databases to predicted 288 protein product targets of genes for bicalutamide and 290 protein product targets of genes for zoledronic acid, respectively. After merging these genes, a total of 831 target genes were obtained. Furthermore, we identified 288 genes targeting bicalutamide and 290 genes targeting zoladex. Merging these resulted in a total of 831 target genes (Supplementary Table S3). Notably, some genes were associated with multiple gene names, suggesting potential isoforms or aliases.

(a) DEGs Volcano plotof dataset GSE7307. The x-axis represents log2FC, the y-axis represents -log10(pvalue), red dots represent up-regulated genes, blue dots represent down-regulated genes, and gray dots represent genes with non-significant differences. (b) DEGs heatmap of dataset GSE7307.The upper part is a density heatmap of the expression levels of the top 10 up- and down-regulated genes, showing lines for the five percentiles and the mean value; the lower part is a heatmap of the expression levels of the top 10 up- and down-regulated genes. (c) Gene intersection Venn diagram (d) GO gene enrichment map. Left half shows GO enrichment analysis. Inner circle has bars for z-scores (higher bars mean darker and more upregulated). Outer circle is a scatter plot of pathway genes, highlighting up/downregulated ones. Right half details GO-rich pathways, dividing top 5 gene-rich pathways into BP, CC, and MF. (e) The left half shows enriched gene names. Darker colors mean higher logFC values; blue indicates downregulated genes. The right half shows enriched functional pathways, colored differently. Larger color blocks mean more genes are enriched in the pathway. (f) PPI protein interaction network. PPI protein interaction network: Circles denote genes, lines indicate interactions, and color from yellow to purple shows degree size from small to large. (g)Venn diagram of central genes.

The 10,148 DEGs were intersected with the 831 target genes, resulting in 179 common genes (Fig. 1C). Functional enrichment analysis revealed that these 179 intersection genes were significantly associated with 1,768 GO terms, including 1,512 biological processes (BPs), 61 cellular components (CCs), and 195 molecular functions (MFs) (Supplementary Table S4). Examples of enriched GO terms include “ribose phosphate metabolic process” (BP), “vesicle lumen” (CC), and “protein serine/threonine kinase activity” (MF) Fig. 1D. These findings offer valuable insights into the biological pathways and cellular functions potentially disrupted in BPH.

The 179 intersection genes were significantly enriched in 148 KEGG pathways, including the “PI3K-Akt signaling pathway,” “MAPK signaling pathway,” and “proteoglycans in cancer” (Fig. 1E). These pathways are known to be crucial in cell proliferation, apoptosis, and cancer progression, implying their involvement in BPH pathogenesis.

To further investigate the interactions among these genes, a PPI network was constructed, consisting of 174 genes and 1,255 interactions (average node degree: 0.474) (Fig. 1F). Notably, AKT1 and ALB showed strong interactions with genes such as CDC42 and EGFR, highlighting key molecular players that may drive the disease mechanism and serve as potential therapeutic targets for BPH.

Finally, 25 candidate genes were identified by overlapping the top 30 genes identified through the Stress and Betweenness algorithms (Fig. 1G).

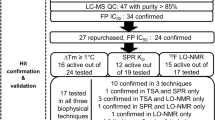

Identification of NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD as key genes for BPH

The SVM-RFE algorithm, based on the initial selection of 25 candidate genes, identified 5 key genes (Fig. 2A). The RF algorithm, in turn, identified 12 genes (Fig. 2B), where the x-axis shows mean decrease Gini, reflecting the importance of each variable, with higher values indicating greater importance. A subsequent overlap of genes identified by both SVM-RFE and RF algorithms yielded 5 feature genes: NQO1, HSPA8, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD (Fig. 2C). Gene expression analysis across two independent datasets (GSE7307 and GSE132714) revealed that NQO1 (P = 0.0004), CLPP (P = 0.0054), HMGCR (P = 0.000261), and SORD (P = 0.0001) were significantly downregulated in BPH samples (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2D-E). This diagram highlights expression differences in the training set and their differential expression in the validation set. These findings highlight the potential of these genes in BPH pathogenesis and their promise as therapeutic targets for the disease.

Exploration of the functions and pathways associated with the key genes

GSEA analysis revealed that NQO1 was significantly enriched in 66 pathways, CLPP in 74 pathways, HMGCR in 65 pathways, and SORD in 57 pathways (Supplementary Table S5). Notably, all key genes were significantly co-enriched in pathways related to “oxidative phosphorylation,” “Huntington’s disease,” “Parkinson’s disease,” and “peroxisome” (Fig. 3A-D, GSEA enrichment analysis of key genes CLPP, HMGCR, NQO1, SORD). These pathways suggest that these genes are involved in critical processes such as cellular energy metabolism, molecular mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases, and organelle functions. GeneMANIA analysis identified 20 genes associated with the key genes. For example, NQO1 was linked to PDLIM4, CLPP to MSMO1, HMGCR to HMGCs1, and SORD to GCLM. These gene interactions were implicated in key processes such as the “sterol biosynthetic process,” “secondary alcohol biosynthetic process,” and “cholesterol metabolic process” (Fig. 3E). These associations highlight the potential roles of the key genes in cellular metabolism and signaling pathways.

(a-d) GSEA enrichment analysis of the key gene CLPP, HMGCR, NQO1, SORD. (e) GGI Network. The center circle represents 4 key genes, while the outer circle includes 20 other genes related to the key genes. The thickness of the lines indicates the strength of interaction, with thicker lines denoting stronger interactions. The color of the lines represents different types of interactions. Each gene is divided into different color modules, with each module representing a specific function.

Unveiling the comprehensive characterization and localization of key genes

Correlation analysis revealed significant positive correlations among the four key genes (cor > 0.80, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). Among the key genes, HMGCR exhibited the strongest correlation with SORD (cor = 0.96, P < 0.001). Additionally, SORD and HMGCR displayed higher functional similarity compared to the other two key genes (Fig. 4B). This suggests that HMGCR and SORD may collaborate synergistically in similar biological processes. Subcellular localization analysis revealed that NQO1 is located in the cytoplasm, CLPP and SORD in the mitochondria, and HMGCR in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane (Fig. 4C). Chromosomal localization analysis showed that NQO1 is located on chromosome 16, CLPP on chromosome 19, HMGCR on chromosome 5, and SORD on chromosome 15 (Fig. 4D). These localization results offer valuable insights into the functional compartmentalization of the key genes within the cell and their genomic distribution.

(a) Key Gene Correlation Analysis. Red indicates a positive correlation, the stronger the correlation, the redder the color, blue indicates a negative correlation, the stronger the correlation, the bluer the color, the * in the circle represents P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001, the stronger the significance, the larger the circle. b) Functional Similarity Analysis of Key Genes. The vertical axis represents key genes, the horizontal axis represents the score corresponding to each gene, one color represents one gene, and the vertical line in the middle of the color represents the median of the scores. (c) Subcellular localization of proteins encoded by key genes. The yellow color indicates the location of the key genes. (d)Chromosomal Localization Analysis of Key Genes.

Exploring the underlying molecular mechanisms of key genes

In this study, 24 key miRNAs targeting the key genes and 94 lncRNAs regulating these miRNAs were identified, leading to the construction of a lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network (Fig. 5A). Notable relationships included LINC01278-“hsa-miR-605-3p”-NQO1, FTX-“hsa-miR-219a-2-3p”-SORD, ZFAS1-“hsa-miR-548o-3p”-HMGCR, and MIR497HG-“hsa-miR-216a-3p”-CLPP. Additionally, TFs targeting these key genes were predicted through NetworkAnalyst, identifying 33 TFs for NQO1, 28 for CLPP, 17 for HMGCR, and 9 for SORD (Fig. 5B). For example, ZNF644 targeted both HMGCR and SORD, SP1 targeted both SORD and CLPP, while NP2F6 and MYNN targeted both HMGCR and NQO1. Moreover, MAZ, ZNF394, and SMAD5 co-targeted both HMGCR and CLPP. TFs such as PHF8 and ELF1 were also identified as co-targeting both NQO1 and CLPP. Finally, through network centrality analysis, we explored how these regulators influence or prioritize key genes in the network. The results showed that the Degree (degree centrality, representing the number of direct connections of a node) was HMGCR (23) > SORD (20) > CLPP (18) > NQO1 (15) (Supplementary Table S6). These results suggest complex regulatory interactions within the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA network and highlight potential transcriptional regulatory mechanisms influencing the expression of key genes involved in the study.

(a) lncRNA-miRNA regulatory network. Red circles represent key genes, green arrows represent miRNAs, and yellow indicates lncRNAs. (b) TF-Critical Gene Regulatory Network. Red circles represent critical genes, and blue polygons represent transcription factors. (c) Key gene CLPP SNPs variation chart. Key gene CLPP SNPs variation chart. Red indicates pathogenic, yellow indicates possibly pathogenic, purple indicates possibly benign, green indicates benign, gray indicates uncertain, and the superscript number indicates the number of mutations. (d)Key Gene-Disease Network. Key Gene-Disease Network Note: In the figure, red nodes represent key genes, and pink nodes represent diseases.

To further investigate the genetic basis of disease mechanisms, SNP analysis within NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD was performed. The results showed that SNPs in CLPP exhibited a higher degree of disease association compared to those in the other key genes (Fig. 5C, Supplemental Fig. 1). This highlights the significant role CLPP may play in the disease process. Furthermore, diseases such as necrosis, hyperplasia, and inflammation were predicted to co-target all key genes, further emphasizing their involvement in the disease mechanisms (Fig. 5D).

Investigation of the binding affinities between bicalutamide, zoladex, and key genes

Molecular docking analysis was conducted to investigate the binding interactions between bicalutamide, zoladex, and key genes. Due to the unavailability of the 3D structure of SORD, molecular docking could not be performed for this gene. The analysis revealed strong binding affinities between CLPP, HMGCR, NQO1, and both drugs (Table 1; Fig. 6A-F). For example, the interaction between NQO1 and bicalutamide resulted in a favorable binding energy of -10.8 kcal/mol, with key interactions observed at residues Y129, F107, and E118 (Fig. 6A). Likewise, the NQO1-zoladex interaction showed a binding energy of -38.05 kcal/mol (Fig. 6D). These results suggest that NQO1, CLPP, and HMGCR are promising targets for bicalutamide and zoladex, providing valuable insights into their therapeutic potential for modulating BPH disease pathways.

(a-f) CLPP-Bicalutamide molecular docking details (left) and overall view (right). CLPP-Bicalutamide molecular docking details (left) and overall view (right). Blue, red, and yellow represent protein structures, gray inside represents the drug structure, amino acid residue structures are around the drug, and the gray dashed lines connect the two parts that interact.

Evaluation of key gene expression in the before-medication group and the after-medication group

In IHC staining, the positive signal of the target protein is visualized by DAB (brownish yellow) and positive staining for target proteins NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD appeared brown-yellow. The results indicated that the expression levels of NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD were significantly higher in the treated group compared to the untreated group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7A-B). These findings suggest that treatment with bicalutamide and zoladex may enhance the expression of these key proteins, potentially indicating their involvement in the therapeutic response.

Discussion

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a prevalent urological disorder characterized by prostate enlargement and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Current clinical treatments, such as α-blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors, primarily focus on symptom management, while bicalutamide and Zoladex—drugs used for PCa—may offer novel therapeutic potential for BPH through mechanisms that remain insufficiently understood17,42,43,44,45. This study identified four key genes (NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD) that were significantly downregulated in BPH tissues. Further Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis revealed an upregulation of these genes following drug treatment, suggesting their involvement in the pathophysiology of BPH.

NQO1 (NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1) is a key antioxidant enzyme that primarily facilitates reduction reactions within cellular environments, particularly by reducing toxic quinone compounds. The enzyme’s primary function is to convert oxidized quinones into alcohols, mitigating oxidative stress and cellular damage. As an integral part of the cellular antioxidant defense system, NQO1 protects against damage caused by free radicals and other harmful agents. Additionally, NQO1 has been implicated in the pathogenesis and progression of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and other chronic conditions46,47,48. This study observed a significant underexpression of NQO1 in BPH tissues, potentially indicating a weakened antioxidant defense mechanism in patients with BPH. Such a deficiency could contribute to the accumulation of oxidative damage in prostate cells. In PCa, NQO1 underexpression has been linked to tumor progression46. This is the first report identifying NQO1 underexpression in BPH, suggesting a potential protective role in benign hyperplasia.

CLPP (Caseinolytic Protease P) is a vital protease within the mitochondria, responsible for the degradation of damaged or excess proteins. CLPP functions as part of a proteasome complex, driving ATP-dependent protein degradation. Its crucial role in intracellular protein turnover links it to the pathogenesis of various diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders49,50,51. The reduced expression of CLPP in BPH may contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, impairing energy metabolism and regulating apoptosis, which can promote abnormal prostate cell proliferation. In neurodegenerative diseases, mutations in CLPP are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction52. This study is the first to report the altered expression of CLPP in BPH, potentially indicating metabolic disruptions in prostate cells.

HMGCR (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase) is a critical enzyme primarily found in the liver and other tissues, playing a key role in cholesterol biosynthesis53. The enzymatic activity of HMGCR is crucial for regulating cholesterol levels in the body. As cholesterol is essential for maintaining cell membrane integrity, hormone production, and vitamin D synthesis, HMGCR has become a significant focus in the study of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, as well as in the development of pharmacological interventions like statins54,55,56. A reduction in HMGCR expression may impair cholesterol synthesis, potentially destabilizing cell membranes, disrupting hormone synthesis, and indirectly promote prostate cell proliferation. In cardiovascular diseases, HMGCR inhibition is known to reduce cholesterol levels54. The observation of HMGCR underexpression in BPH suggests that disrupted cholesterol metabolism might contribute to BPH pathogenesis.

SORD (Sorbitol Dehydrogenase) is an enzyme involved in sorbitol metabolism, where it catalyzes the conversion of sorbitol into fructose, thereby preventing its accumulation and alleviating complications related to diabetes57. SORD also plays a role in carbohydrate metabolism and cellular osmoregulation, helping maintain intracellular environmental stability58,59,60. A decrease in SORD expression can result in sorbitol buildup, leading to oxidative stress and cellular damage, which may exacerbate prostate tissue hyperplasia. In diabetic complications, SORD deficiency is linked to sorbitol accumulation58. This study is the first to report SORD underexpression in BPH, suggesting that disturbed glucose metabolism might contribute to BPH progression.

IHC analysis demonstrated that the expression of NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD significantly increased in samples treated with bicalutamide and goserelin (P < 0.05). This pharmacological intervention appears to enhance antioxidant capacity (via NQO1), restore mitochondrial function (via CLPP), regulate cholesterol metabolism (via HMGCR), and improve glucose metabolism (via SORD), all of which may inhibit abnormal prostate cell proliferation. The upregulation of these genes correlates with symptom improvement in BPH, indicating their potential as novel therapeutic targets. For example, targeted activation of NQO1 or supplementation with mitochondrial protease (CLPP) may help mitigate BPH progression. Although NQO1 and HMGCR have been previously studied in the context of PCa, their roles in BPH represent novel findings, suggesting common metabolic abnormalities between the two conditions. Moreover, the involvement of CLPP and SORD in diabetes and neurodegenerative diseases suggests that BPH pathogenesis may be influenced by broader metabolic disorders, providing valuable insights for cross-disease research46,47,48,49.

The co-enrichment of key genes (NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, SORD) in oxidative phosphorylation and peroxisomal pathways suggests that BPH pathogenesis involves interconnected mitochondrial and peroxisomal dysfunction. Oxidative phosphorylation, crucial for ATP synthesis and ROS regulation61, appears to be impaired in BPH, as evidenced by the downregulation of CLPP, which disrupts mitochondrial protein homeostasis, and the deficiency of NQO1, which diminishes antioxidant capacity. This disruption may shift prostate cells toward glycolytic metabolism (the Warburg effect), promoting hyperplasia62. Concurrent peroxisomal dysfunction, indicated by dysregulation of SORD and HMGCR, likely disrupts lipid metabolism and redox balance, leading to the accumulation of toxic lipids (e.g., ceramides) and ROS-induced stromal damage63,64. These pathways are metabolically interconnected through acetyl-CoA exchange and ROS cross-talk. NQO1 stabilizes organelle membranes by reducing quinones, while HMGCR and SORD preserve membrane integrity through cholesterol and glucose metabolism. The combined disruption of energy metabolism and lipotoxic stress creates a pathogenic microenvironment that favors prostate cell proliferation and fibrotic remodeling, hallmarks of BPH.

Current treatment strategies for BPH mainly rely on α-receptor blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors, but they are associated with side effects such as dizziness and sexual dysfunction65. This study found that bicalutamide and zoladex can upregulate the expression of 4 key genes and have strong binding affinity with CLPP, HMGCR, and NQO1, suggesting that these two drugs may treat BPH by regulating metabolic and oxidative stress pathways. Clinically, for patients with poor response to traditional treatments, low-dose combination therapy with bicalutamide or goserelin may be considered. However, it is necessary to refer to their usage experience in prostate cancer and closely monitor side effects caused by changes in sex hormone levels (such as decreased testosterone), such as reduced libido. In addition, efforts can be made to develop new biomarker detection kits. These 4 key genes are lowly expressed in BPH tissues and significantly upregulated after treatment, which can serve as potential markers for evaluating therapeutic efficacy, reflecting the degree of recovery of antioxidant and mitochondrial functions, and guiding efficacy judgment and dosage adjustment.

The role of miRNAs in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and BPH has attracted significant attention. In HCC, miR-216a-3p has been shown to inhibit cancer cell proliferation by targeting the AKT/mTOR pathway66. In BPH, however, miR-216a-3p plays a more complex role, promoting prostate cell proliferation by targeting the mitochondrial protease CLPP and disrupting mitochondrial homeostasis. Similarly, miR-128-3p has been implicated in BPH by targeting HMGCR, the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis, thereby affecting cholesterol metabolism and indirectly stimulating proliferation67. TF MYNN exacerbates oxidative damage and inflammation in BPH by inhibiting NQO1, while ZNF644 contributes to lipotoxicity and metabolic disorders by repressing genes related to cholesterol and glucose metabolism (e.g., HMGCR, SORD). Additionally, MAZ induces mitochondrial dysfunction and osmotic imbalance, further promoting glandular proliferation by inhibiting CLPP and SORD68.

It is hypothesized that miR-216a-3p, miR-128-3p, and TFs ZNF644 and MAZ may form a feedback loop that synergistically downregulates NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, and SORD, thereby exacerbating oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, and cell proliferation67. Network centrality analysis revealed that HMGCR is the most core protein among these 4 nodes and may undertake core regulatory functions in the network. SORD shows an overall performance close to HMGCR, especially comparable to HMGCR in terms of bottleneck effect and betweenness, making it an important secondary core node in the network. NQO1 has fewer direct connections but performs well in bottleneck effect and betweenness, indicating that although its local connections are slightly weak, it still plays an intermediary role in some key pathways. CLPP has a relatively large number of direct connections (18), but its bottleneck score and betweenness are the lowest, suggesting that it is mainly involved in local dense interactions and has a weak mediating and controlling effect on the global network.This study represents the first attempt to construct the regulatory networks of BPH, encompassing both the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA and TF-mRNA networks. However, further experimentation is required to validate these targeting relationships and expression levels.

Bicalutamide and norethindrone have demonstrated strong binding affinities for target proteins (NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR), with norethindrone binding to NQO1 at a binding energy of -38.05 kcal/mol69,70. These results suggest that these drugs could potentially treat BPH by activating antioxidant mechanisms, repairing mitochondria, and inhibiting cholesterol synthesis, among other effects. The efficacy of multi-target drugs, which simultaneously interact with multiple proteins such as NQO1, CLPP, and HMGCR, may be enhanced. Additionally, gene expression levels could serve as predictive biomarkers for drug efficacy. Currently, bioinformatics approaches are used for prediction, but further validation through dual luciferase reporter assays, qPCR, or Western blotting is necessary to confirm the targets and expression changes.

The present study has the following limitations: First, the sample information in the dataset lacks detailed annotations and the sample size is small (n = 10), which may affect the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the samples used for immunohistochemistry are heterogeneous, with only 5 samples in each group, which may impact the robustness of the results. Second, the use of zoladex and bicalutamide for BPH treatment can affect non-disease targets and cause changes in sex hormones, with potential drug side effects, leading to restrictions in clinical application. Moreover, the regulatory networks of TFs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs lack experimental validation and require further verification.

In the future, we will expand the sample size, seek multi-center and more comprehensive data for analysis, and attempt in-depth analyses based on subtype classification to improve the generalizability, depth, and accuracy of the research results. We will also optimize the sampling method for clinical samples and increase the number of samples to avoid sample heterogeneity and enhance the reliability of the results. Second, we will attempt to verify the mitochondrial function of CLPP through gene knockout/overexpression experiments. Third, surface plasmon resonance/ion mobility detection (SPR/ITC) can be used to confirm the binding affinity. In addition, we will conduct experiments in BPH tissues or related cell lines to explore how these regulatory interactions (TFs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs) are involved in the pathogenesis of BPH. We will also try to construct animal models for drug efficacy, safety, and toxicology experiments to evaluate the side effects of zoladex and bicalutamide in BPH treatment, and explore the possibility of drug modification (such as reducing side effects) or combination therapy to enhance their clinical value, so as to balance academic discoveries with clinical reality.

This study integrated transcriptomics and network pharmacology to identify four downregulated genes (NQO1, CLPP, HMGCR, SORD) in BPH, which were upregulated following bicalutamide/Zoladex treatment, indicating potential therapeutic applications. Co-enrichment of these genes in oxidative phosphorylation and peroxisome pathways underscores metabolic dysregulation in BPH pathogenesis. Molecular docking revealed robust drug-gene interactions, such as NQO1-Norlevo with a binding energy of -38.05 kcal/mol, while regulatory networks implicated upstream factors like hsa-miR-216a-3p and ZNF644 in gene suppression.

Data availability

The data used in this study were publicly obtained from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (GSE7307 and GSE132714). Codes for bioinformatic analysis can be browsed on http://github.com/pgh128/project1.git.

References

Madersbacher, S., Sampson, N. & Culig, Z. Pathophysiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia and benign prostatic enlargement: a Mini-Review. Gerontology 65 (5), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496289 (2019).

Miernik, A. & Gratzke, C. Current treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Dtsch. Arztebl Int. 117 (49), 843–854. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2020.0843 (2020).

Langan, R. C. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prim. Care. 46 (2), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2019.02.003 (2019).

Kim, E. H., Larson, J. A. & Andriole, G. L. Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Annu. Rev. Med. 67, 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-063014-123902 (2016).

Miernik, A. & Gratzke, C. Current treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 118, 6. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m (2021).

Culig, Z., Madersbacher, S. & Sampson, N. Pathophysiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia and benign prostatic enlargement: a mini-review. Gerontology 65, 5 (2019).

Launer, B. M., McVary, K. T., Ricke, W. A. & Lloyd, G. L. The rising worldwide impact of benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 127 (6), 722–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.15286 (2021).

Macey, M. R. & Raynor, M. C. Medical and surgical treatment modalities for lower urinary tract symptoms in the male patient secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia: a review. Semin Intervent Radiol. 33 (3), 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1586142 (2016).

Zambon, J. P., Koslov, D. S., Mihai, B. & Badlani, G. H. Bladder and ureteral dysfunction leading to hydronephrosis and hydroureteronephrosis in adults. Urology 117, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2017.11.049 (2018).

Presicce, F., De Nunzio, C. & Tubaro, A. Can Long-term LUTS/BPH Pharmacological treatment alter the outcomes of surgical intervention?? Curr. Urol. Rep. 18 (9), 72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11934-017-0721-8 (2017).

Osman, T. et al. Evaluation of Tamsulosin 0.4 mg versus 0.8 mg in management of lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic enlargement. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 56 (6), 1811–1816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-023-03912-7 (2024).

Yu, Q. et al. New strategies for Inhibition of non-adrenergic prostate smooth muscle contraction by Pharmacologic intervention. Prostate 79 (7), 746–756. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.23780 (2019).

Halawani, A. et al. Risks and side effects in the medical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate Int. ;12, 1 (2024).

Gandhi, J. et al. The impact and management of sexual dysfunction secondary to Pharmacological therapy of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Transl Androl. Urol. 6, 4 (2017).

Dykes, T. A. et al. Epidemiology and treatment modalities for the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Transl. Androl. Urol. 8, 5 (2019).

Inamura, S. & Terada, N. Chronic inflammation in benign prostatic hyperplasia: pathophysiology and treatment options. Int. J. Urol. 31 (9), 968–974. https://doi.org/10.1111/iju.15518 (2024).

Gu, W. et al. Rezvilutamide versus bicalutamide in combination with androgen-deprivation therapy in patients with high-volume, metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (CHART): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 23 (10), 1249–1260. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00507-1 (2022).

Eri, L. M. & Tveter, K. J. Effects of bicalutamide and leuprolide on prostate-specific antigen (PSA), acid phosphatase (ACP) and prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 4 (3), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.pcan.4500504 (2001).

Abo El-Enen, M. et al. Goserelin acetate before transurethral resection of moderately enlarged benign prostatic hyperplasia: prospective randomised-controlled clinical trial. Arab. J. Urol. 14 (1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aju.2015.09.007 (2016).

Welén, K. & Damber, J. E. Androgens, aging, and prostate health. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 23 (6), 1221–1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-022-09730-z (2022).

Kim, M., Tran, P., Yin, J., Song, J. & Kim, H. Cinnamomum cassia and Rosa laevigata mixture improves benign prostatic hyperplasia in rats by regulating androgen receptor signaling and apoptosis. Nutrients 15 (4), 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15040818 (2023).

Nicholson, T. M. & Ricke, W. A. Androgens and estrogens in benign prostatic hyperplasia: past, present and future. Differentiation 82 (4–5), 184–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diff.2011.04.006 (2011).

Caprino, L. Farmaci per Il Trattamento dell’ipertrofia prostatica Benigna [Drugs for the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy]. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 52 (2), 87–92 (2000).

Shah, A. et al. Mechanistic targets for BPH and prostate cancer—a review. Rev. Environ. Health ;35, 3 (2020).

Nogales, C. et al. Network pharmacology: curing causal mechanisms instead of treating symptoms. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 43 (2), 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2021.11.004 (2022).

Liu, D. et al. Integrative multiplatform molecular profiling of benign prostatic hyperplasia identifies distinct subtypes. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 1987. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15913-6 (2020).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (7), e47. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015).

Gustavsson, E. K. et al. Ggtranscript: an R package for the visualization and interpretation of transcript isoforms using ggplot2. Bioinformatics 38 (15), 3844–3846. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac409 (2022).

Gu, Z. Complex heatmap visualization. iMeta 1 (3), e43. https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.43 (2022).

Chen, H. & Boutros, P. C. VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinform. 12, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-35 (2011).

Yu, G. et al. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16 (5), 284–287. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0118 (2012).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13 (11), 2498–2504. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1239303 (2003).

Mahmoudian, M. et al. Stable iterative variable selection. Bioinformatics 37 (24), 4810–4817. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btab501 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Unveiling the key genes, environmental toxins, and drug exposures in modulating the severity of ulcerative colitis: a comprehensive analysis. Front. Immunol. 14, 1162458. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1162458 (2023).

Robles-Jimenez, L. E. et al. Worldwide traceability of antibiotic residues from livestock in wastewater and soil: a systematic review. Anim. (Basel). 12 (1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12010060 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Cuproptosis related genes associated with Jab1 shapes tumor microenvironment and Pharmacological profile in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 13, 989286. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.989286 (2022).

Yu, G. et al. GOSemSim: an R package for measuring semantic similarity among GO terms and gene products. Bioinformatics 26 (7), 976–978. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq064 (2010).

Shen, Y. et al. Critical evaluation of web-based prediction tools for human protein subcellular localization. Brief. Bioinform. 21 (5), 1628–1640. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbz106 (2020).

Zhang, H., Meltzer, P. & Davis, S. RCircos: an R package for circos 2D track plots. BMC Bioinform. 14, 244. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-244 (2013).

Hu, Y. et al. Combination usage of adipocount and Image-Pro plus/imagej software for quantification of adipocyte sizes. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 642000. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.642000 (2021).

Mitteer, D. R. & Greer, B. D. Using GraphPad prism’s heat maps for efficient, fine-grained analyses of single-case data. Behav. Anal. Pract. 15 (2), 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00664-7 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Identification of predictors based on drug targets highlights accurate treatment of Goserelin in breast and prostate cancer. Cell. Biosci. 11 (1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-020-00517-w (2021).

Li, H. et al. Role of α1-blockers in the current management of hypertension. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich). 24 (9), 1180–1186 (2022).

Gadzhieva, Z. K. & Kazilov, Y. B. Urologiia 1, 91–98 (2016).

Corona, G. et al. Sexual dysfunction in subjects treated with inhibitors of 5α-reductase for benign prostatic hyperplasia: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Andrology 5 (4), 671–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12353 (2017).

Jahan, N. et al. Neferine improves oxidative stress and apoptosis in benign prostate hyperplasia via Nrf2-ARE pathway. Redox Rep. 26 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510002.2021.1871814 (2021).

Ross, D. & Siegel, D. The diverse functionality of NQO1 and its roles in redox control. Redox Biol. 41, 101950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2021.101950 (2021).

Khan, A. E. M. A., Arutla, V. & Srivenugopal, K. S. Human NQO1 as a selective target for anticancer therapeutics and tumor imaging. Cells 13 (15), 1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13151272 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Genetic variants of CLPP and M1AP are associated with risk of Non-Small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 11, 709829. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.709829 (2021).

Lee, Y. G. et al. LONP1 and CLPP cooperatively regulate mitochondrial proteostasis for cancer cell survival. Oncogenesis 10 (2), 18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41389-021-00306-1 (2021).

Kumar, R. et al. A mitochondrial unfolded protein response inhibitor suppresses prostate cancer growth in mice via HSP60. J. Clin. Invest. 132 (13), e149906. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI149906 (2022).

Devlin, C. M., Simms, M. S. & Maitland, N. J. Benign prostatic hyperplasia—what do we know? BJU Int. 127 (4), 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.15229 (2021).

Chen, W. et al. The potential role and mechanism of circrna/mirna axis in cholesterol synthesis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 19 (9), 2879–2896. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.84994 (2023).

Fang, S. et al. Association between genetically proxied PCSK9 Inhibition and prostate cancer risk: a Mendelian randomisation study. PLoS Med. 20 (1), e1003988. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003988 (2023).

Basavaraj, P. et al. Alpinumisoflavone exhibits the therapeutic effect on prostate cancer cells by repressing AR and Co-Targeting FASN- and HMGCR-Mediated lipid and cholesterol biosynthesis. Life (Basel). 12 (11), 1769. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12111769 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Identification of coding region SNPs from specific and sensitive mRNA biomarkers for the Deconvolution of the semen donor in a body fluid mixture. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 52, 102483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2021.102483 (2021).

Zhu, Y. et al. Sorbitol reduction via govorestat ameliorates synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration in sorbitol dehydrogenase deficiency. JCI Insight. 8 (10), e164954. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.164954 (2023).

Cortese, A. et al. Biallelic mutations in SORD cause a common and potentially treatable hereditary neuropathy with implications for diabetes. Nat. Genet. 52 (5), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-0615-4 (2020).

Pons, N. et al. SORD-related peripheral neuropathy in a French and Swiss cohort: clinical features, genetic analyses, and sorbitol dosages. Eur. J. Neurol. 30 (7), 2001–2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.15793 (2023).

Lasorsa, F. et al. Emerging hallmarks of metabolic reprogramming in prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (2), 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24020910 (2023).

Li, S. et al. NOSTRIN is involved in benign prostatic hyperplasia via Inhibition of proliferation, oxidative stress, and inflammation in prostate epithelial cells. Transl Androl. Urol. 13 (9), 2055–2069. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau-24-209 (2024).

Zheng, K., Chen, S. & Hu, X. Peroxisome Proliferator-activated receptor gamma Coactivator-1 alpha: a Double-edged sword in prostate cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 22 (7), 541–559. https://doi.org/10.2174/1568009622666220321110926 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Simvastatin improves benign prostatic hyperplasia: role of Peroxisome-Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ and classic WNT/β-Catenin pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (5), 4911. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054911 (2023).

Zheng, T. et al. Functional mechanism of hsa-miR-128-3p in epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic cancer cells via ZEB1 regulation. PeerJ 10, e12802. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.12802 (2022).

Lee, K. S. et al. A prospective, randomized, open-label, parallel trial comparing the efficacy of α-blocker or 5α-reductase inhibitor withdrawal to continued combination therapy on the maintenance of lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate 84 (4), 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.24663 (2024).

Zhou, L. et al. Decoding CeRNA regulatory network and autophagy-related genes in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 225, 997–1009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.11.162 (2023).

Mou, S. I. et al. Comprehensive characterization of coding and non-coding single nucleotide polymorphisms of the myoneurin (MYNN) gene using molecular dynamics simulation and Docking approaches. PLoS One. 19 (1), e0296361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296361 (2024).

Lerner, L. B. et al. Management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA GUIDELINE PART I-Initial Work-up and medical management. J. Urol. 206 (4), 806–817. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000002183 (2021).

Chen, N. et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of Goserelin 10.8-mg depot in Chinese patients with localized or locally advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 20 (12), 1047–1059. https://doi.org/10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2023.0335 (2024).

Weijers, J. A. M. et al. A randomized phase II trial on the addition of dutasteride to combined androgen Blockade therapy versus combined androgen Blockade therapy alone in patients with advanced or metastatic salivary duct carcinoma - the DUCT study protocol. BMC Cancer. 24 (1), 1174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12889-0 (2024).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Guohui Peng . and Fei Zuo .; methodology, Zicun Liang .; software, Fei Zuo .; validation, Jiuming Li ., Fei Han .; formal analysis, Fei Zuo .; investigation, Hua Shen .; resources, Guohui Peng .; data curation, Fei Zuo .; writing—original draft preparation, Zicun Liang .; writing—review and editing, Guohui Peng .; visualization, Fei Han .; supervision, Guohui Peng .; project administration, Bin Zhang . All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, G., Liang, Z., Zuo, F. et al. Identification of genes related to the effects of bicalutamide and zoladex on benign prostatic hyperplasia. Sci Rep 15, 32901 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18211-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18211-7