Abstract

This study introduces an end-to-end Reinforcement Learning (RL) approach for controlling Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) with slung loads, addressing both navigation and obstacle avoidance in real-world environments. Unlike traditional methods that rely on separate flight controllers, path planners, and obstacle avoidance systems, our unified RL strategy seamlessly integrates these components, reducing both computational and design complexities while maintaining synchronous operation and optimal goal-tracking performance without the need for pre-training in various scenarios. Additionally, the study explores a reduced observation space model, referred to as CompactRL-8, which utilizes only eight observations and excludes noisy load swing rate measurements. This approach differs from most full-state observation RL methods, which typically include these rates. CompactRL-8 outperforms the full ten-observation model, demonstrating a 58.79% increase in speed and a ten-fold improvement in obstacle clearance. Our method also surpasses the state-of-the-art adaptive control methods, showing an 8% enhancement in path efficiency and a four-fold increase in load swing stability. Utilizing a detailed system model, we achieve successful Sim2Real transfer without time-consuming re-tuning, confirming the method’s practical applicability. This research advances RL-based UAV slung-load system control, fostering the development of more efficient and reliable autonomous aerial systems for applications like urban load transport. A video demonstration of the experiments can be found at https://youtu.be/GtGHhOCmy3M.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intelligent Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have become indispensable across various domains such as delivery services 1,2,3, inspection 4, and transportation systems due to their ability to operate in diverse and challenging environments 5,6. Notably, UAVs with slung loads are transforming air delivery systems by enabling the rapid transport of essential items like packages, medicines, food, and mail to both remote and urban areas 1,7. These cargo-bearing UAVs, especially multirotors, are highly valued for autonomous cargo delivery owing to their high maneuverability and hovering capability 7. This capability is critical for applications ranging from disaster relief 8 to scientific research 1. Additionally, their low cost, ease of handling, and minimal environmental requirements make them superior to traditional manned aerial vehicles in fields such as military operations, agriculture, and forestry 9,10,11. Recent advancements highlight the significant potential of multirotors for aerial load delivery using slung loads 12,13. A UAV slung-load system allows efficient load transport without compromising the UAV’s dynamic performance 12, whereas using a gripper can hinder the UAV’s attitude dynamics and necessitate close ground approaches, increasing ground effect risks 12,14. The challenge of controlling UAVs for transporting suspended loads has been a subject of extensive research due to its complexity and practical significance 15. The UAV slung-load system, with its eight degrees-of-freedom (DOF) and only four control inputs, presents a challenging double under-actuated system that exhibits strong nonlinearity and dynamic coupling complexities 15. Addressing these challenges, a variety of control strategies have been developed to improve UAV positioning and mitigate load oscillations.

Early approaches to UAV load transportation primarily employed conventional fixed-gain linear control techniques due to their simplicity and ease of implementation 15. While these methods provided a foundational framework, they often struggled to manage the nonlinear dynamic interactions between the UAV and its payload, particularly during high-maneuverability scenarios. This limitation stems from the fact that both PID and LQR controllers rely on linearization around specific operating points. Consequently, their performance was often compromised when dealing with the inherent nonlinearities introduced by moving loads, as well as the unpredictable conditions typical in UAV operations 16. Moreover, fixed-gain linear controllers inherently lack adaptive mechanisms, making them less robust in handling disturbances and uncertainties that are common in real-world operations.

Control strategies for UAV load transportation have evolved towards sophisticated nonlinear approaches, with researchers exploring adaptive control techniques to address system complexities13,17,18. However, these methods often require extensive system knowledge and complex tuning. A significant challenge lies in the mismatch between the inherent Multi-Input Multi-Output (MIMO) nature of these systems and the Single-Input Single-Output (SISO) design of most control solutions, often leading to performance degradation. Furthermore, most of these recent control approaches have been designed for obstacle-free environments, whereas in real-world applications, systems often need to navigate around obstacles.

As the limitations of adaptive control methods became increasingly apparent, researchers explored intelligent control approaches, with a particular focus on Reinforcement Learning (RL) 19,20,21. RL techniques offered the promise of adaptive control strategies capable of handling the complex, high-dimensional nonlinear dynamics 22,23. RL involves an agent learning through trial-and-error interactions within an environment to make sequential decisions 24. The agent evaluates its actions using a value function, and the integration of neural networks for value function approximation and action generation marks the advent of Deep Reinforcement Learning 25. This adaptability has shown great potential in addressing tracking, motion control and navigation problems in unmanned systems 5,6,26,27. Li et al. made significant strides in this direction by proposing an RL method using Deep Q-Networks to plan swing-free trajectories for UAVs carrying suspended loads 9. Their approach, which relied on a discretized action space, demonstrated the potential of RL in this domain. However, the discretization of the action space potentially limited the system’s capacity to achieve finer control over continuous spaces, highlighting an area for future improvement. Panetsos et al. utilized the Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3) algorithm to control multi-rotor UAVs with cable-suspended loads 10. Their approach aimed to minimize swing during transportation and integrated the learned policy network within a UAV’s cascaded control architecture, replacing the conventional PID controllers. These works designed the controller for an obstacle-free environment for a UAV slung-load system, while in a real-world setting this system can encounter obstacles while navigating. Moreover, a significant portion of RL research in robotics remains confined to simulations due to the Sim2Real gap 28. This gap arises when an agent trained in simulation does not perform effectively in the real world, often due to discrepancies between simulated and actual system dynamics 29. Addressing the Sim2Real gap is crucial for the practical deployment of RL in real-world applications 29.

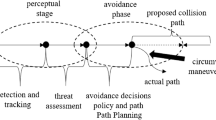

Early RL applications showed promise in generating swing-free trajectories 1,30,31; however, they often relied on separate path planning algorithms and obstacle avoidance mechanisms. This separation introduced considerable design complexity and led to asynchrony between goal tracking and obstacle avoidance tasks, inherently increasing the risk of instability, collisions, and necessitating re-tuning of operational coefficients for different scenarios. More importantly, many recent studies have employed full-state observations, including load swing rates, to train RL models 32. This approach proves impractical in real-world scenarios, as load swing rate data is prone to sensor noise and difficult to obtain reliably 33.

To address critical gaps, this research presents a reduced-observation-space RL framework that integrates path planning, load swing suppression, and obstacle avoidance, while effectively filtering out noisy load swing rate measurements. This integrated approach aims to reduce system complexity, enhance real-time performance, and improve adaptability to varying operational conditions. By leveraging RL’s capacity to learn optimal policies in complex, multi-objective scenarios, our work seeks to advance UAV load transportation systems that can efficiently navigate obstacles, minimize load swing, and optimize paths simultaneously, without relying on separate algorithms for each task. Furthermore, our approach directly tackles the Sim2Real gap through the use of detailed system modeling, enabling successful transfer from simulation to real-world settings, eliminating the need for time-consuming fine-tuning. This end-to-end solution offers a more efficient and practical approach to UAV slung-load control in environments with a static obstacle.

To this end, the proposed contributions of this work are summarised as follows:

-

1.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that proposes an end-to-end RL based solution, that integrates control, path planning, and obstacle avoidance into a single framework, for navigation of UAV slung-load system in the presence of a static obstacle in the environment with real-world experimental validation.

-

2.

In contrast to the existing RL methods focused on full observation space (UAV position and velocity, obstacle position, and load swing angle and angular rates) 34, three separate navigation modules 31, and complex tuning process 13,35, we introduce a simplified reduced-observation space RL model, CompactRL-8, by eliminating the load swing angular rates.

-

3.

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed approach, we conducted extensive comparisons in simulations, benchmarked against state-of-the-art methods, including a full observation space variant (FullRL-10), inspired by 9,10, SLQ-MPC 36, and adaptive controller 37, using performance metrics such as speed, obstacle clearance, and path efficiency. These results were validated through real-world experiments, confirming the robustness of the RL agent without the need for fine-tuning.

Background

Proximal policy optimization

RL is a machine learning paradigm aimed at learning an optimal policy, \(\pi ^*\), that maximizes cumulative rewards through interactions with an environment. These environments are typically modeled as Markov Decision Processes (MDPs), characterized by a set of states (\(\mathscr {S}\)), actions (\(\mathscr {A}\)), state transition probabilities (\(\mathscr {P}\)), reward functions (\(\mathscr {R}\)), and a discount factor (\(\gamma\)). The goal in RL is to find a policy that maximizes the expected sum of discounted rewards, defined by the value function \(V^\pi (s)\) 24.

The UAV slung-load system is rigorously modeled as MDP, formally delineated by the tuple \((\mathscr {S}, \mathscr {A}, \mathscr {P}, \mathscr {R}, \gamma )\):

-

\(\mathscr {S} \in \mathbb {R}^n\), \(n\) \(\textemdash\) state space dimension

-

\(\mathscr {A} \in \mathbb {R}^m\), \(m\) \(\textemdash\) action space dimension

-

\(\mathscr {P}: \mathscr {S} \times \mathscr {A} \times \mathscr {S} \rightarrow [0, 1]\)

-

\(\mathscr {R}: \mathscr {S} \times \mathscr {A} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\)

-

\(\gamma \in (0, 1)\), discount factor

Each state \(s_t \in \mathscr {S}\) and action \(a_t \in \mathscr {A}\) at discrete time \(t\) are vectors in their respective spaces. The transition probability function \(\mathscr {P}\) satisfies the Markov property, such that \(\mathscr {P}(s_{t+1}|s_t, a_t)\) depends only on the current state \(s_t\) and action \(a_t\), not on the sequence of events that preceded it.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is a state-of-the-art policy gradient algorithm in RL 38, particularly effective for continuous action spaces. PPO improves upon previous methods by addressing stability and complexity issues, offering a robust and simplified approach to policy optimization. It utilizes a clipped surrogate objective function to constrain the magnitude of policy updates, thereby maintaining stability during training. The core idea of PPO is to maximize a “surrogate” objective function:

where,

-

\(\theta\) represents the policy parameters

-

\(\hat{\mathbb {E}}_t[...]\) denotes the empirical expectation over a finite batch of samples

-

\(r_t(\theta )\) is the probability ratio between the new and old policy:

$$r_t(\theta ) = \frac{\pi _\theta (a_t|s_t)}{\pi _{\theta _{old}}(a_t|s_t)}$$ -

\(\hat{A}_t\) is an estimator of the advantage function at t

-

\(\epsilon\) is a hyperparameter, typically set to 0.1 or 0.2

The clipping function \(\text {clip}(r_t(\theta ), 1-\epsilon , 1+\epsilon )\) constrains the probability ratio \(r_t(\theta )\) to stay within the interval \([1-\epsilon , 1+\epsilon ]\). This clipping mechanism ensures that the objective function penalizes policy updates that move \(r_t(\theta )\) too far from 1, effectively limiting the size of policy updates.

PPO typically uses separate neural networks for the policy \(\pi _\theta (a_t|s_t)\) and the value function \(V_\phi (s_t)\). The overall optimization problem can be formulated as:

where,

-

\(\phi\) denotes the parameters of the value function \(V_\phi (s_t)\)

-

\(L^{VF}(\phi )\) is the squared-error loss \((V_\phi (s_t) - V_t^{targ})^2\) for the value function

-

\(S\pi _\theta\) is an entropy bonus to encourage exploration

-

\(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are coefficients

PPO commonly uses Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE) to compute the advantage function \(\hat{A}_t\):

where,

-

\(\delta _t = R_t + \gamma V(s_{t+1}) - V(s_t)\) is the TD residual

-

\(\gamma\) is the discount factor

-

\(\lambda\) is the GAE parameter

PPO is particularly suited for continuous control tasks, as it handles large and complex action spaces with smoother policy updates, reducing the risk of performance degradation from excessive changes. Its balance of exploration and exploitation enables the development of robust policies that generalize well from simulated environments to real-world applications, making it an ideal choice for training UAV slung-load systems in this research.

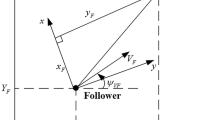

UAV slung-load model

This section presents the mathematical model of the UAV slung-load system used to train the RL agent in simulation, as depicted in Fig. 1. The RL agent is responsible for generating reference velocities for the UAV, which serve as its action outputs. These reference velocities are then passed to an inner-loop controller that commands the UAV’s motors. Training the RL agent on the nonlinear model ensures it captures the complex interactions of the real-world system, allowing for a direct transfer from simulation to reality due to the close match between the two 23.

The complete system is represented by a set of coupled nonlinear differential equations that describe the dynamics of the UAV and the suspended load. The equations of motion for the quadrotor in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions, incorporating the effects of the suspended load, are given by:

where \(\mathfrak {J} = m_l L_r\). The angular dynamics of the load along the \(x\) and \(y\) axes are:

In these equations:

The suspended load primarily affects the lateral dynamics of the UAV slung-load system. Since the payload is suspended from the center of gravity of the multirotor, it does not create moments that alter the UAV’s attitude dynamics; thus, the attitude dynamics remain unaffected by the load15.

To implement the reference velocities generated by the RL agent, an inner-loop controller is employed. This controller receives the reference velocities and translates them into motor commands for the UAV. The inner-loop controller is designed using the linearized dynamics of the multirotor UAV, comprising of attitude dynamics \(G_{att}(s)\) and lateral dynamics \(G_{lat}(s)\), which are obtained through decoupling and linearization of the system 39,40. It’s important to note that, unlike the inner-loop controller, the RL agent is trained on the nonlinear dynamics of the UAV, as described in (3)–(6).

Problem formulation

This study aims to develop an end-to-end RL approach for UAV-slung load systems that integrates control, path planning, and obstacle avoidance into a unified framework. The primary challenge is to design and implement a reduced observation space model with an effective reward function that, when trained with the PPO algorithm, yields a robust control policy capable of efficient navigation and obstacle avoidance in complex environments, while also demonstrating successful Sim2Real transfer for practical real-world applications.

Consider a UAV-slung load system operating in a two-dimensional plane with the fixed altitude. The system’s state evolves in a continuous-time, nonlinear dynamical system described by:

where \(\textbf{x} \in \mathscr {S} \subset \mathbb {R}^n\) is the state vector, \(\textbf{u} \in \mathscr {A} \subset \mathbb {R}^m\) is the control input vector, and \(f: \mathscr {S} \times \mathscr {A} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^n\) is a nonlinear function describing the system dynamics.

The system is subject to the following assumptions 15:

-

1.

The load is suspended from the center of gravity of the multirotor.

-

2.

The suspension connection is frictionless.

-

3.

The suspended payload is a point-mass.

-

4.

The suspension cable is massless and rigid (always in tension).

-

5.

The load swing angle is constrained: \(|\alpha _t|, |\beta _t| \le \frac{\pi }{2}\).

The objective is to find an optimal policy \(\pi _\theta ^*\), with observation space \(\mathscr {O} \subseteq \mathscr {S}\) a subset of the state space, that maximizes the expected cumulative discounted reward, defined by the value function:

where \({R_t}\) is the reward at time step t. The PPO algorithm is employed to solve this optimization problem. \(\pi _\theta : \mathscr {O} \rightarrow \mathscr {A}\) be a stochastic policy parameterized by \(\theta\), mapping observations to actions.

The action output \(\textbf{u}_t \in \mathscr {A} \subset \mathbb {R}^2\), from the RL agent based on the optimal policy to reach the goal state \(\textbf{g} = \begin{bmatrix} x_g&y_g \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb {R}^2\), is defined as:

where \(v_{t,x}^{cmd}, v_{t,y}^{cmd}\) are the commanded velocities in x and y directions, respectively.

Methodology

The primary objective of this study is to introduce and evaluate a simplified eight-observation model for end-to-end RL solution, as the framework depicted in Fig. 2, for UAV slung-load systems referred to as CompactRL-8. This streamlined approach is designed to enhance navigation and obstacle avoidance capabilities. Our methodology aims to demonstrate the superiority of CompactRL-8 by comparing it with a more complex ten-observation variant (FullRL-10). We investigate how this strategic reduction in the observation space impacts the RL agent’s performance, focusing on improvements in control accuracy, operational efficiency, and task performance.

The training procedure and the associated exploration were conducted entirely in simulation using MATLAB/Simulink, with episodes terminating based solely on their length to allow full exploration and learning. The PPO agent was trained with stochastic exploration based on entropy, where initial policy outputs were highly stochastic due to an entropy regularization term in the PPO objective, which decayed over time to encourage convergence toward deterministic behavior. The system was excited using randomly sampled actions from a Gaussian policy. Stability during early training was maintained through several mechanisms: PPO’s clipped surrogate objective limited magnitude of policy updates, reducing instability from high-variance exploration; action outputs were bound to adhere to realistic actuator limits, preventing physically infeasible behavior; and all episodes were run for a fixed number of steps, ensuring stable temporal credit assignment. Only fully trained policies, with deterministic action selection, were deployed on the physical system, ensuring safe and repeatable real-world execution. The hyperparameters are summarized in Table 1.

In CompactRL-8 the observation space, denoted by the 8-dimensional vector \(\textbf{o}_t^{(1)}\), is comprised of:

where \(d_{t,x}^g\) and \(d_{t,y}^g\) represent the Euclidean distances from the UAV’s current position to the goal in the x and y directions, respectively. These distances are crucial for guiding the agent towards the desired goal location. The inclusion of \(v_{t,x}\) and \(v_{t,y}\), which denote the UAV’s velocities in the x and y directions, enables the agent to perceive and respond to its current motion dynamics. The observation vector also incorporates the load swing angles \(\alpha _t\) and \(\beta _t\), which quantify the oscillations of the slung load in the longitudinal and lateral planes, respectively. These angles play a critical role in ensuring stable and controlled flight maneuvers while transporting the slung load. Furthermore, the Euclidean distance \(d_t^{obs}\) from the UAV to the obstacle is incorporated, enabling the agent to perceive and respond to potential collision hazards. Finally, the elapsed time \(t_t\) is included, which may aid the agent in learning temporal patterns and adapting its behavior accordingly.

In contrast, FullRL-10 employs a slightly different observation space, which is a 10-dimensional vector \(\textbf{o}_t^{(2)}\) at time t, comprising the following elements:

In this variant, the rate of change of the load swing angles, \(\dot{\alpha }_t\) and \(\dot{\beta }_t\), is included in this observation space, providing the agent with complete information about the oscillatory dynamics of the load.

The observation spaces \(\textbf{o}_t^{(1)}\) and \(\textbf{o}_t^{(2)}\) are elements of the Euclidean spaces \(\mathbb {R}^{8}\) and \(\mathbb {R}^{10}\), respectively, with their components representing various physical quantities and their corresponding units. For instance, \(d_{t,x}^g\), \(d_{t,y}^g\), \(d_t^{obs} \in \mathbb {R}\) are distances measured in meters (m), \(v_{t,x}\), \(v_{t,y} \in \mathbb {R}\) are velocities measured in meters per second (m/s), \(\alpha _t\), \(\beta _t \in \mathbb {R}\) are angles measured in radians (rad), \(\dot{\alpha }_t\), \(\dot{\beta }_t \in \mathbb {R}\) are angular rates measured in radians per second (rad/s), and \(t_t \in \mathbb {R}^+\) is the elapsed time measured in seconds (s).

The action space \(\mathscr {A}\) is a subset of the Euclidean space \(\mathbb {R}^2\), defined as:

where \(v_{x}^{ref}\) and \(v_{y}^{ref}\) are the reference velocities in the x and y directions, respectively, bounded by the maximum allowable velocities of \(\pm 1\) m/s.

To guide the agent’s learning process, the reward function \(R_t\) is defined as:

where

The reward function was designed to balance goal-directed efficiency with obstacle avoidance, reflecting both domain-specific considerations and empirical validation. The first term, \(\left( \sqrt{d_{x,l}^2 + d_{y,l}^2}\right) t\), encourages the agent to minimize the Euclidean distance between the slung load and the goal location, scaled by the elapsed time t. This time-weighted formulation promotes rapid convergence toward the goal while inherently accounting for the oscillatory dynamics of the slung load, which are influenced by the UAV’s motion and load swing angles. The second term, \(\mathbb {I}(d_t^{\text {obs}} < d_{\text {t}_o}) \frac{1}{(d_t^{\text {obs}})^2 + d_{\text {safe}}}\), imposes a proximity-based penalty when the UAV approaches an obstacle. The indicator function \(\mathbb {I}(\cdot )\) activates the penalty only when the UAV is within a threshold distance \(d_{\text {t}_o}=0.3\) from an obstacle. The denominator includes a safety margin \(d_{\text {safe}}=0.01\) to ensure a smooth and numerically stable gradient, thereby discouraging risky navigation behavior without inducing singularities in the reward landscape during training. To preserve the natural scale of each term and avoid introducing additional hyperparameters that could destabilize training, both components were assigned unit coefficients. Extensive experimentation with alternative formulations and weightings demonstrated that the adopted structure offered a robust balance between performance and stability. Thus, this formulation was selected through iterative tuning guided by domain insights and practical constraints imposed by the training environment. Fig. 3 outlines the structured process used to design and tune the reward function, integrating domain knowledge with empirical validation.

A high-level overview of the full training and deployment pipeline is provided in Algorithm 1.

Results and discussion

This section outlines a set of experiments designed to validate our end-to-end RL technique to achieve the objective of navigating the UAV slung-load system in a 2D plane, at a fixed altitude, in the presence of an obstacle. We begin by detailing the experimental setups. Subsequently, we present the simulation results, including the comparisons, and finally present the experimental results to validate our findings in simulation.

Experimental setup

The experimental setup used in this work consists of a Kopis CineWhoop 41 quadrotor. The low-level controller of the multirotor was run on the onboard Raspberry Pi. The RL agent was implemented using MATLAB/Simulink on the ground station with Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-1165G7 computer. An OptiTrack motion capture system was used to obtain the position and velocity of the quadrotor and the load for real-world experimental testing. The communication, at 200 Hz, between the motion capture system, the RL agent, and the onboard flight controller is achieved through a Robot Operating System (ROS) interface. The ROS/OptiTrack integration operates over the same local network, minimizing transmission delays. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 4 and the physical setup is shown in Fig. 5. The system parameters used to train the agent based on the physical platform are listed in Table 2.

In our simulation studies, we evaluated CompactRL-8 and FullRL-10 under different environmental configurations to provide a comprehensive assessment of their performance across varied scenarios. For CompactRL-8, we set the goal location at (2.5, 2.5) with an obstacle at (0.8, 0.8), while for FullRL-10, the goal was positioned at (0.75, 0.75) with an obstacle at (0.3, 0.3). Both simulations initiated from the origin (0, 0). To ensure meaningful comparisons despite these differing setups, we employed normalized metrics throughout our analysis. These normalized measures allowed us to evaluate the relative performance of each algorithm within its respective environment, enabling valid cross-scenario comparisons. The use of normalized metrics mitigates the impact of absolute distance differences, focusing instead on the algorithms’ efficiency and effectiveness in achieving their goals relative to their specific environmental constraints. Through this methodology, we have obtained an understanding of each algorithm’s performance characteristics across different environmental scales and complexities, while maintaining the validity of our comparative analysis.

For the real-world experiments, the goal location for was extended to (3, 3), and the obstacle was repositioned to (1, 1). These modifications were made to assess the adaptability of our RL agent better. By altering the goal and obstacle positions from those in the simulation, we aimed to evaluate the agent’s ability to generalize its learned policy to new spatial configurations, ensuring it adapts to environmental changes rather than relying on memorization of specific positions.

Comparative algorithms

This study conducts a performance comparison of our proposed CompactRL-8 method with FullRL-10, inspired by 9,10, adaptive controller 37 and SLQ-MPC 36. While the key parameters of the adaptive controller and SLQ-MPC are maintained as presented in37 and36, respectively. The parameters of our approach are configured as outlined in Table 1, selected based on pilot experiments.

Simulation results

The simulations were conducted to evaluate the performance of the RL agent in navigating the UAV slung-load system towards the goal location while avoiding obstacles and damping the load swing.

Simulation result for CompactRL-8: The left side of the figure displays the 3D trajectory of the UAV, with snapshots illustrating the UAV and its slung load (represented by UAV and small red markers) at various points along the path. On the right, three subplots are shown: the top subplot depicts the UAV’s position in the X-Y plane, the middle subplot illustrates the time evolution of the UAV’s X and Y coordinates, and the bottom subplot shows the time variation of the slung load angles \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\).

Simulation result for FullRL-10: The left side of the figure displays the 3D trajectory of the UAV, with snapshots illustrating the UAV and its slung load (represented by UAV and small red markers) at various points along the path. On the right, three subplots are shown: the top subplot depicts the UAV’s position in the X-Y plane, the middle subplot illustrates the time evolution of the UAV’s X and Y coordinates, and the bottom subplot shows the time variation of the slung load angles \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\).

In the simulation tests for CompactRL-8, the agent successfully navigated the UAV slung-load system towards the goal, traversing a mean distance of 4.34 meters in less than 15 seconds. The simulation plot for CompactRL-8 (Fig. 6) provides a visual representation of the UAV’s motion path. The plot shows a smooth and efficient trajectory towards the goal, with the UAV effectively avoiding the obstacle located at (0.8, 0.8). The load swing angles, as depicted in the subplots, exhibit well-damped oscillations, indicating the agent’s proficiency in minimizing load swing oscillations even over longer distances.

In FullRL-10, the UAV traversed a mean distance of 1.64 meters to reach the goal location, taking approximately 9 seconds. The relatively shorter distance and time can be attributed to the proximity of the goal to the starting position. However, it is noteworthy that the agent maintained a mean minimum clearance of 0.05 meters from the obstacle, showing close obstacle clearance. The plots in Fig. 7 provides a visual representation of the simulation results. The plot clearly shows the UAV maneuvering along a nearly straight-line trajectory towards the goal while being closely clearing the obstacle, indicated by the asterisk symbol. The load swing angles, depicted in the subplots, exhibit small oscillations throughout the trajectory.

Notably, the agent maintained a mean minimum clearance of 0.5 meters from the obstacle in CompactRL-8, a larger clearance compared to FullRL-10. This observation suggests that the agent comfortably clears the obstacle and adapted its navigation strategy to account for the obstacle.

The mean speed of the UAV was \(0.289 \ m/s\) for CompactRL-8 and \(0.182 \ m/s\) for FullRL-10. In real-world scenarios, UAVs often encounter obstacles that prevent them from taking the shortest possible path (i.e., the Euclidean distance) between the start and goal points. As a result, the UAV must navigate around these obstacles, leading to a longer actual path.

Although CompactRL-8 and FullRL-10 were evaluated under different configurations, with variations in goal locations and obstacle placements, the core structure of the task remained consistent across both setups. To ensure a fair and objective comparison, all reported performance metrics, including path length, speed, and load swing, were normalized with respect to the specific geometric layout of each configuration. This normalization accounts for differences in spatial arrangement and enables meaningful comparison of relative policy performance, rather than raw distance or trajectory shape.

To evaluate the efficiency of the path taken, we use the Path Efficiency (PE) metric. It provides information on how well the control algorithm performs in avoiding obstacles while minimizing the total travel distance. It is computed by comparing the actual path length traversed by the UAV slung-load system to an optimal reference path, defined as the shortest (Euclidean) path that also satisfies a minimum clearance constraint of \(0.3 \ m\) from the obstacle. This provides a quantitative assessment of trajectory efficiency relative to a feasible, collision-free baseline.

PE is defined as:

where,

-

\(L_{\text {opt}}\) is the Euclidean distance between the start and goal points, observing the minimum clearance constraint.

-

\(L_{\text {actual}}\) is the actual path length taken by the UAV slung-load system.

For instance, in our experiments, the Euclidean distance (\(L_{\text {opt}}\)) between the start and goal points for CompactRL-8 was 3.53 m. However, due to the presence of an obstacle along the direct path, the UAV slung-load system had to navigate around it, resulting in an actual path length (\(L_{\text {actual}}\)) of 4.34 m.

Substituting these values into (10), we obtain:

A PE value of 1 indicates a perfectly optimal path, while a value less than 1 indicates a less efficient path. In this case, a PE of 0.813 suggests that the actual path taken by the UAV is approximately 81.3% as efficient as the optimal Euclidean path.

Our results, summarized in Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate the efficiency of our proposed method in comparison to state-of-the-art approaches from the literature. Our method demonstrates superior flexibility in handling diverse goal locations and obstacle scenarios. While the adaptive controller 37 does not explicitly address obstacle avoidance, our approach successfully navigates around obstacles. This capability is crucial for real-world applications.

CompactRL-8 achieves a path efficiency of 81.34%, surpassing the 75% efficiency of the SLQ-MPC approach 36. This indicates that our algorithm generates more optimal trajectories, potentially leading to energy savings in practical deployments. We impose a maximum speed limit of 1 m/s to ensure practical deployability, prioritizing stability and safety over raw speed. The mean speed of our method is lower to balance efficient movement with minimal load disturbance.

A key strength of our approach is the exceptional load stability it achieves. Our method limits the peak load swing to 5 degrees, significantly outperforming the adaptive controller 37 (30 degrees) and SLQ-MPC 36 (20 degrees). This dramatic reduction in load swing is critical for applications involving sensitive or hazardous materials in crowded environments, where having minimum load swing is important.

The radar plot in Fig. 8 compares the multi-objective performance of the control methods: Proposed (CompactRL-8), SLQ-MPC, and Adaptive Controller. The performance metrics evaluated include Path Efficiency, Load Stability, and Obstacle Handling. Each axis represents a performance metric, and the distance from the center to the plotted line indicates the relative performance for each method. Higher values towards the outer edge denote better performance in the respective metric. Marker points on each line highlight specific performance scores. The plot illustrates the strengths and weaknesses of each method across the evaluated criteria.

Our results reflect a sophisticated multi-objective optimization approach. By simultaneously considering path efficiency, obstacle avoidance, and load stability, our method achieves a more balanced performance profile. This holistic approach is particularly valuable in complex, real-world scenarios where multiple, often competing, objectives must be satisfied.

Experimental results

Experiment result for CompactRL-8: The main plot (left) shows the 3D path of the UAV, with snapshots of the UAV slung-load system (indicated by UAV and small red markers) at various points along the trajectory. The right side of the figure contains three subplots: the top subplot presents the UAV’s position in the X-Y plane. The middle subplot shows the time evolution of the UAV’s X and Y coordinates. The bottom subplot shows the angles \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) of the slung load over time.

To validate the simulation findings and assess the performance of the proposed RL agent in real-world scenarios, a series of experiments were conducted using the UAV slung-load system. These experiments aimed to evaluate the agent’s ability to navigate the UAV slung-load system towards the goal location while avoiding obstacles and minimizing load swing oscillations under practical conditions.

The plots in Fig. 9 shows the results for the experimental tests for CompactRL-8. It shows the UAV’s motion path exhibits a smooth and efficient trajectory towards the goal, successfully avoiding the obstacle. However, the load swing angles in the longitudinal and lateral planes reveal less well-damped oscillations compared to the simulations. This discrepancy could be attributed to several factors, including the rotor wash (strong downward air current) that affects the thin load cable, which might cause the load to swirl and induce oscillations. Environmental factors such as wind also play a role.

Discussions

The results from both simulations and real-world experiments provide valuable insights into the performance and adaptability of the RL agent in controlling UAV slung-load systems. The comparison between CompactRL-8 and FullRL-10 reveals significant differences in performance and highlights key factors influencing the system’s behavior.

In the simulations, both cases demonstrated the agent’s ability to navigate towards the goal while avoiding obstacles. Compact-RL8 exhibited adaptability to increased distances, maintaining a larger clearance from the obstacle, whereas, FullRL-10 had a much smaller clearance from the obstacle.

The experimental results demonstrated the agent’s adaptability and performance. CompactRL-8’s experimental setup closely mirrored the simulation, and the results showed consistent performance in navigation and obstacle avoidance. However, the load swing angles showed less damped oscillations than in simulations, likely due to real-world factors such as rotor wash and measurement inaccuracies.

The results demonstrates the superior performance of CompactRL-8, which excluded load swing rates from the observation space. This simplification of the state representation appears to have allowed the agent to focus on critical aspects of the task, such as goal-reaching and obstacle avoidance, leading to more stable and reliable performance. This observation aligns with the principle of state abstraction in RL, where removing less relevant information can improve learning efficiency and generalization42.

To further clarify these discrepancies, we summarize in Table 5 the main sources of mismatch between simulation and reality. While the simulator captured motor and aerodynamic behavior with high fidelity using identified UAV parameters, certain unmodeled effects, such as rotor wash interacting with the suspended cable and sensor feedback inaccuracies, had a non-negligible influence on the load swing dynamics. Notably, swirling of the load cable due to rotor-induced turbulence likely degraded the accuracy of motion capture system pose estimates, leading to erroneous state observations that the policy treated as real perturbation. This sensing-induced mismatch contributed to the sustained oscillations seen in the experimental results.

Despite these mismatches, the trained policy was able to operate robustly when deployed on hardware without any fine-tuning or online adaptation. This is a key advantage of reinforcement learning: the policy is trained as a closed-loop control law that maps observations directly to actions based on empirical interaction, rather than relying on an explicit system model. As a result, the learned behavior remains reactive and robust to moderate discrepancies in dynamics, sensor delays, or external perturbations. Furthermore, the PPO algorithm optimizes long-term return using actual experience under the learned policy, which enhances generalization. The entropy-driven exploration during training also encourages coverage of diverse state regions, contributing to the policy’s resilience during real-world execution.

Conclusions

This study presents an RL approach for navigation and obstacle avoidance in UAV slung-load systems operating in complex environments. Our approach harnesses the power of RL to develop an end-to-end control solution capable of guiding the UAV-load system to a target location while adeptly avoiding obstacles and minimizing load oscillations. The focus of our study was to present an end-to-end RL approach with a reduced observation space to decrease computational and design complexity. Through extensive simulations and real-world experiments, we demonstrated that our RL agent, achieved proficiency in navigation and obstacle avoidance. The proposed model showed improvement in speed and obstacle clearance compared to the 10-observation variant. In contrast to existing methods, our method unified control, path planning and obstacle avoidance resulting in improved path efficiency. In addition, our study successfully validated the simulation findings in real-world experimental settings, which reinforces the practical applicability of our approach.

Although the results of this study are highly encouraging, several avenues for future research can be explored. Future work could consider dynamic environments, where the goal location and obstacles may change during flight. Furthermore, investigating transfer learning and domain adaptation techniques could improve task performance and facilitate the generalization of the trained RL agent to different scenarios, potentially reducing the need for extensive retraining.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Faust, A., Palunko, I., Cruz, P., Fierro, R. & Tapia, L. Automated aerial suspended cargo delivery through reinforcement learning. Artif. Intell. 247, 381–398 (2017).

Haddad, A. G., Mohiuddin, M. B., Boiko, I. & Zweiri, Y. Fuzzy ensembles of reinforcement learning policies for systems with variable parameters. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters (2025).

Muthusamy, P. K. et al. Aerial manipulation of long objects using adaptive neuro-fuzzy controller under battery variability. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–20 (2025).

Mohiuddin, M., Hay, O. A., Abubakar, A., Yakubu, M. & Werghi, N. UAV-assisted logo inspection: Deep learning techniques for real-time detection and classification of distorted logos. In 2024 8th International Conference on Robotics, Control and Automation (ICRCA), 428–432 (IEEE, 2024).

Yue, K. Multi-sensor data fusion for autonomous flight of unmanned aerial vehicles in complex flight environments. Drone Syst Appl 12, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1139/dsa-2024-0005 (2024).

He, Y., Hou, T. & Wang, M. A new method for unmanned aerial vehicle path planning in complex environments. Sci. Rep. 14, 9257. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60051-4 (2024).

Lin, D., Han, J., Li, K., Zhang, J. & Zhang, C. Payload transporting with two quadrotors by centralized reinforcement learning method. IEEE Trans Aerosp Electron Syst 60(1), 239–251 (2023).

Chehadeh, M. et al. Aerial firefighting system for suppression of incipient cladding fires. Field Robot 1, 203–230 (2021).

Li, R., Yang, F., Xu, Y., Yuan, W. & Lu, Q. Deep reinforcement learning-based swing-free trajectories planning algorithm for UAV with a suspended load. In 2022 China Automation Congress (CAC), 6149–6154 (IEEE, 2022).

Panetsos, F., Karras, G. C. & Kyriakopoulos, K. J. A deep reinforcement learning motion control strategy of a multi-rotor UAV for payload transportation with minimum swing. In 2022 30th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED), 368–374 (IEEE, 2022).

Tran, V. P., Mabrok, M. A., Anavatti, S. G., Garratt, M. A. & Petersen, I. R. Robust adaptive fuzzy control for second-order Euler-Lagrange systems with uncertainties and disturbances via nonlinear negative-imaginary systems theory. IEEE Trans Cybern 54(9), 5102–5114 (2024).

Tang, S., Wüest, V. & Kumar, V. Aggressive flight with suspended payloads using vision-based control. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 3, 1152–1159. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2018.2793305 (2018).

Tran, V. P., Santoso, F., Garrat, M. A. & Anavatti, S. G. Neural network-based self-learning of an adaptive strictly negative imaginary tracking controller for a quadrotor transporting a cable-suspended payload with minimum swing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68, 10258–10268 (2020).

Sreenath, K., Lee, T. & Kumar, V. Geometric control and differential flatness of a quadrotor UAV with a cable-suspended load. In 52nd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, 2269–2274, doi:10.1109/CDC.2013.6760219 (2013).

Mohiuddin, M. B. & Abdallah, A. M. Dynamic modeling and control of quadrotor slung-load system using PID and nonlinear backstepping controller. In AIAA Scitech 2021 Forum, 0107, doi:10.2514/6.2021-0107 (2021).

Lee, S. & Son, H. Antisway control of a multirotor with cable-suspended payload. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 29, 2630–2638. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCST.2020.3035004 (2021).

Tran, V. P., Santoso, F., Garrat, M. A. & Petersen, I. R. Adaptive second-order strictly negative imaginary controllers based on the interval type-2 fuzzy self-tuning systems for a hovering quadrotor with uncertainties. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 25, 11–20 (2019).

Tran, V. P., Mabrok, M. A., Anavatti, S. G., Garratt, M. A. & Petersen, I. R. Robust fuzzy Q-learning-based strictly negative imaginary tracking controllers for the uncertain quadrotor systems. IEEE Trans Cybern 53, 5108–5120 (2022).

Belkhale, S. et al. Model-based meta-reinforcement learning for flight with suspended payloads. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 6, 1471–1478. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2021.3057046 (2021).

Lee, G., Kim, K. & Jang, J. Real-time path planning of controllable UAV by subgoals using goal-conditioned reinforcement learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 146, 110660 (2023).

Sitong, Z., Yibing, L. & Qianhui, D. Autonomous navigation of UAV in multi-obstacle environments based on a deep reinforcement learning approach. Appl Soft Comput J 115, 81–94 (2022).

Mohiuddin, M. B., Boiko, I., Azzam, R. & Zweiri, Y. Closed-loop stability analysis of deep reinforcement learning controlled systems with experimental validation. IET Control Theory Appl https://doi.org/10.1049/cth2.12712 (2024).

Mohiuddin, M. B., Haddad, A. G., Boiko, I. & Zweiri, Y. Zero-shot sim2real transfer of deep reinforcement learning controller for tower crane system. IFAC-PapersOnLine 56, 10016–10020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2023.10.867 (2023).

Sutton, R. S. Learning to predict by the methods of temporal differences. Mach. Learn. 3, 9–44 (1988).

Mnih, V. et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 518, 529–533. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14236 (2015).

Feiyu, Z., Dayan, L., Zhengxu, W., Jianlin, M. & Niya, W. Autonomous localized path planning algorithm for UAVs based on TD3 strategy. Sci. Rep. 14, 763. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51349-4 (2024).

Sun, W., Sun, P., Ding, W., Zhao, J. & Li, Y. Gradient-based autonomous obstacle avoidance trajectory planning for B-spline UAVs. Sci. Rep. 14, 14458. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65463-w (2024).

Truong, J., Chernova, S. & Batra, D. Bi-directional domain adaptation for sim2real transfer of embodied navigation agents. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 6, 2634–2641. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2021.3062303 (2020).

Zhao, W., Queralta, J. P. & Westerlund, T. Sim-to-real transfer in deep reinforcement learning for robotics: A survey. In 2020 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), 737–744, https://doi.org/10.1109/SSCI47803.2020.9308468(2020).

Faust, A., Palunko, I., Cruz, P., Fierro, R. & Tapia, L. Learning swing-free trajectories for UAVs with a suspended load. In 2013 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, pp. 4902–4909, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA.2013.6631277(IEEE, 2013).

Faust, A. et al. PRM-RL: Long-range robotic navigation tasks by combining reinforcement learning and sampling-based planning. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pp. 5113–5120, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA.2018.8461096(IEEE, 2018).

Morimoto, J. & Doya, K. Reinforcement learning state estimator. Neural Comput 19, 730–756. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco.2007.19.3.730 (2007).

Zhou, T., Chen, M. & Zou, J. Reinforcement learning based data fusion method for multi-sensors. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sin 7, 1489–1497. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2020.1003180 (2020).

Son, C. Y., Seo, H., Kim, T. & Jin Kim, H. Model predictive control of a multi-rotor with a suspended load for avoiding obstacles. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pp. 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA.2018.8460749(IEEE, 2018).

Tran, V. P., Mabrok, M. A., Garratt, M. A. & Petersen, I. R. Hybrid adaptive negative imaginary-neural-fuzzy control with model identification for a quadrotor. IFAC J Syst Control 16, 100156 (2021).

Son, C. Y., Kim, T., Kim, S. & Kim, H. J. Model predictive control of a multi-rotor with a slung load for avoiding obstacles. In 2017 14th International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots and Ambient Intelligence (URAI), pp. 232–237 (IEEE, 2017).

Chang, P., Yang, S., Tong, J. & Zhang, F. A new adaptive control design for a quadrotor system with suspended load by an elastic rope. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 19073–19092 (2023).

Schulman, J., Wolski, F., Dhariwal, P., Radford, A. & Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06347 (2017).

Alkayas, A. Y., Chehadeh, M., Ayyad, A. & Zweiri, Y. Systematic online tuning of multirotor UAVs for accurate trajectory tracking under wind disturbances and in-flight dynamics changes. IEEE Access 10, 6798–6813. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3142388 (2022).

Peringal, A., Chehadeh, M., Boiko, I. & Zweiri, Y. Relay-based identification of aerodynamic and delay sensor dynamics with applications for unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Sens J 24(8), 13085–13094 (2024).

Holybro. Holybro_Kopis_CineWhoop(Analog VTx version)_Manual. Holybro.

Bruin, T., Kober, J., Tuyls, K. & Babuška, R. Integrating state representation learning into deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 3, 1394–1401. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2018.2800101 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Khalifa University and KU Center for Autonomous Robotic Systems (KUCARS) for supporting this work under Award No. RC1-2018-KUCARS, and RIG-2023-076.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B.M. conceptualized the study, designed the methodology, curated the data, developed the software, conducted the investigation, performed the formal analysis, and wrote the original draft. I.B. supervised the work, conceptualized the study, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. V.P.T. contributed to visualization and conceptualization of the study, curated the data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.G. provided guidance and oversight during the work, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.A. provided guidance and oversight during the drafting process of the manuscript and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Y.Z. supervised the work, secured funding, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohiuddin, M.B., Boiko, I., Tran, V.P. et al. Reinforcement learning for end-to-end UAV slung-load navigation and obstacle avoidance. Sci Rep 15, 34621 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18220-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18220-6