Abstract

For construction engineering to be most effective, it’s essential to understand the hardness properties of high-performance concrete (HPC), such as compressive strength and slump. However, predicting these properties is challenging due to complex, non-linear relationships and the inherent variability of factors like the water-cement ratio and mineral additives. Traditional modeling methods often struggle to handle these uncertainties effectively. This paper introduces a novel Hybrid Fuzzy Artificial Neural Network (HFANN) architecture that integrates fuzzy logic with advanced machine learning models, including Support Vector Regression (SVR), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), all optimized by the Chaos Game Optimization (CGO). The fuzzy logic system employs Gaussian membership functions and a Sugeno-type rule base to preprocess inputs, generating 18 fuzzy features per sample to capture data uncertainties. The CGO enhances model performance by optimizing hyperparameters and ensemble weights through a chaotic search based on the Sierpinski triangle. The HFANN framework demonstrates superior predictive accuracy compared to traditional models. It achieves a 25% reduction in RMSE for compressive strength and R² values of 0.98 for compressive strength and 0.97–0.99 for slump across training, validation, and testing phases. These results, validated through MANOVA and Tukey’s HSD tests, indicate significant improvements over conventional methods. The HFANN framework offers a robust tool for enhancing HPC mix design and advancing sustainable construction practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-performance concrete (HPC) is an advanced cementitious and fibrous concrete with high compressive strength (CS) (50–100 MPa)1, tensile strength (8–12 MPa)2, improved particle packing density (0.80–0.85)3, and excellent durability4. HPC has significantly higher energy absorption and ductility compared to normal concrete, and its compressive strength is three to eight times that of normal concrete5. Owing to its enhanced toughness and ductility under strain, as well as its strong mechanical characteristics, HPC is often recognized as a suitable material for seismic design applications6. HPC is a viable option for improving infrastructure and the long-term viability of construction facilities7. High-performance concrete is prepared with a low water-to-cement (w/c) ratio, often between 0.25 and 0.358. Due to the low water volume, high-range water-reducing agents are necessary to enhance particle packing in the composite material, leading to improved workability and fluidity of the mix9. As cementitious binders, Portland cement (PC) and silica fume are often employed in HPC production scenarios10. As the high greenhouse gas inventory of PC has become a global issue, the need for more sustainable cementing binders has advanced significantly11,12. Concrete structural component sizes can be decreased for thinner, smaller, and more aesthetically pleasing designs thanks to HPC’s mechanical properties, which make it the perfect material for applications where strength is a primary design goal13,14,15. PC, silica fume, fine aggregate, a high-range water-reducing component, and fibers are usually its constituents. Concrete buildings subjected to hostile environments can benefit from HPC16. HPC is frequently used in long-span constructions, bridge engineering (BE) design, and high-rise buildings17. HPC shortens service cycles in extreme weather or outdoor settings, and its increased durability prolongs the lifecycle18. Synthetic fibers in HPC can achieve high compressive strength and enhanced tensile ductility in concrete materials15,19. Even though HPC technology and advancements have been thoroughly examined at all scales, from the micro to the macro, its broad acceptance is still difficult because of its complicated production process and comparatively expensive costs20,21. The usage of several components contributes significantly to the complex production process, which raises prices and creates handling challenges. Infrastructure developers can expand their service offerings by using a product that HPC technology offers22. The fundamental idea behind this technology is the adoption of methodical approaches to address the inherent drawbacks of conventional concrete; for instance, geopolymer technology can be used to make HPC in a sustainable manner23. This revolutionary concrete is superior because it is more ductile and can deform and withstand flexural and tensile loads even after early cracking occurs24,25,26. increased bonding optimization and mineral matrix microstructural properties among the concrete matrix constituents are the causes of HPC’s increased performance features27. The mechanical properties of HPC render it an optimal material for applications where strength is a primary design criterion, enabling a reduction in the dimensions of concrete structural components for more slender, compact, and aesthetically pleasing designs28. It generally consists of polycarbonate, silica fume, fine aggregate, a high-range water-reducing agent, and fibers28,29. HPC is appropriate for concrete structures subjected to severe environmental conditions. HPC is frequently utilized in the design of high-rise buildings, bridge engineering, and long-span structures24. In extreme climatic conditions, HPC diminishes service cycles, and its superior durability prolongs the lifecycle25. The incorporation of synthetic fibers in high-performance concrete enables the attainment of elevated compressive strength and enhanced tensile ductility in concrete materials30,31. Despite extensive examination of HPC advancements and technology from micro to macro perspectives, its broad implementation continues to be hindered by considerable expenses and a convoluted manufacturing process32,33. The intricate production process primarily arises from the use of multiple components, which leads to increased costs and handling challenges. HPC technology delivers a solution that enables infrastructure developers to expand their service offerings34. The primary principle of this technology is to implement systematic methods to rectify the intrinsic deficiencies of conventional concrete; for instance, a sustainable approach to producing HPC can be achieved through geopolymer technology. This advanced concrete is excellent due to its increased ductility, allowing it to deform and sustain flexural and tensile loads even post-initial fracture. The enhanced performance attributes of HPC stem from optimized bonding and the microstructural properties of the mineral matrix inside the concrete matrix elements. Nevertheless, the utilization of HPC as an innovative material is increasingly attracting interest from various stakeholders, including researchers and construction firms35. Several recent studies provide important insights into the application of advanced computational and experimental methods in concrete and structural engineering. The authors in36 developed hybrid gradient boosting models for predicting the compressive strength of high-volume fly ash self-compacting concrete incorporating silica fume, demonstrating improved predictive accuracy and practical applicability for sustainable mix design. A comprehensive review in37 examined soft computing techniques for predicting the mechanical properties of high-performance and ultrahigh‐performance concrete, identifying hybrid approaches as the most robust solutions due to their ability to address heterogeneity and uncertainty in material properties. The study in38 estimated the compressive strength of ultrahigh‐performance concrete using various machine learning models and concluded that ensemble and deep learning techniques outperform traditional regression models, with sensitivity analysis revealing the most influential mix parameters. The authors in39 carried out a comparative analysis of sloshing effects on elevated water tanks’ dynamic response using artificial neural networks (ANN) and multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS), finding ANN to be superior for highly nonlinear scenarios while MARS offered better interpretability. Experimental and analytical investigations in40 on light gauge steel sections in concrete-filled steel tubes (CFST) using steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) at elevated temperatures showed that SFRC significantly enhances load-bearing capacity and fire resistance. The authors in41 advanced seismic vulnerability assessment of bridge structures by integrating ANN and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to develop fragility curves, achieving higher accuracy in predicting damage probabilities under varying seismic intensities. A multifaceted comparative study in42 of incremental dynamic and static pushover methods for bridge assessment integrated ANN with a genetic algorithm to optimize predictive models, resulting in enhanced reliability in seismic performance estimation. The authors in43 used ANN-based modeling to predict the fire-induced structural performance of steel tube columns filled with SFRC, accurately estimating residual strength and deformation after exposure to high temperatures. The work in44 applied the MARS model to evaluate the impact of biaxial geogrid reinforcement on subgrade soil strength, producing interpretable models that inform optimal reinforcement configurations. Finally, the authors in45 investigated the combined influence of manufactured sand and fly ash on concrete strength using both experimental testing and machine learning methods, enabling accurate forecasting of strength development across varying replacement levels and mix designs.

A study in46 evaluates polymer-modified cement-grouted sands using ASTM and BS standards, then models’ strength as a function of w/c, polymer dosage, sand grading, and age. Nonlinear models outperform linear ones, and polymer addition markedly increases compressive and flexural strengths at 7 and 28 days. The work also explains microstructural causes for strength gains and provides conversion between testing standards. Using five sand gradings and two standards, the authors in47 compare LR, MLR, NLR, ANN, and M5P for predicting compressive strength of polymer-modified grouts. NLR and ANN provide the best generalization on held-out data, and BS testing yields higher strengths than ASTM for otherwise identical mixes. The paper underscores the role of mix proportion and curing time in model performance. The authors in48 builds a multi-region dataset of clay friction angles and proposes a DNN enhanced by Harris Hawks Optimization for hyperparameter search. The HHO–DMLP model outperforms SVM and RF baselines on multiple metrics, with improved robustness across geologic settings. The authors also note overfitting risks in RF that their approach mitigates. The work in49, several soft computing techniques were investigated for predicting concrete compressive strength from UPV and rebound hammer results, using a dataset of 629 cases. The methods assessed included back-propagation neural networks (BPNN), relevance vector machines, minimax probability machine regression, genetic programming, Gaussian process regression, and multivariate adaptive regression splines. It was found that BPNN and multivariate adaptive regression splines achieved the highest predictive accuracy, surpassing the performance of models previously reported in the literature. With focusing on sustainable lightweight concretes that incorporate oil palm by-products, the authors in50 compile a large dataset and benchmark several AI models, for example MARS, GEP, M5P, and ELM. The best models achieve accurate strength mapping across mix designs, supporting circular-economy materials with data-driven tools. In51, an artificial neural network (ANN) approach was proposed for predicting concrete compressive strength using data obtained from non-destructive tests, specifically ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) and Schmidt rebound hammer measurements. It was demonstrated that the ANN models could provide reliable approximations of actual compressive strength values despite the inherent variability of the NDT data, and the network weights were reported to enable practical spreadsheet implementation.

Even though there has been a lot of research on HPC, most predictive methods still use either traditional regression or standalone machine learning models. These models have a lot of trouble simulating the complicated, non-linear interactions between the several characteristics that make up HPC. These models are typically affected by noise in the data and changes in measurements, and they don’t have ways to measure how uncertain input features like the water-to-binder ratio, silica fume, and superplasticizer concentration are. Also, current hybrid and ensemble methods rarely combine fuzzy logic for modeling uncertainty with sophisticated learners like SVR, MLP, and GBM. They also don’t use chaos-based metaheuristics for systematic hyperparameter optimization. This gap has made prediction models less reliable, flexible, and useful in real-world HPC mix design.

This study gives an important advancement to construction engineering by introducing a novel hybrid method for evaluation of hardness properties in HPC, mainly its compressive strength and slump. Below are the key contributions:

-

Innovative Hybrid Fuzzy-ANN Framework: Introduces a Hybrid Fuzzy Artificial Neural Network (HFANN), integrating fuzzy logic with Support Vector Regression (SVR), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), and Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) to model non-linear, uncertain HPC properties and enhance prediction accuracy with fuzzy features.

-

Advanced Fuzzy Preprocessing: Utilizes a Fuzzy Inference System with Gaussian membership functions and fuzzy rules to preprocess inputs, adding fuzzy features per sample to capture data uncertainties effectively.

-

Novel Chaos Game Optimization (CGO): Employs CGO to optimize hyperparameters for SVR (regularization, epsilon, gamma), MLP (layers, neurons, learning rate), and GBM (trees, depth, learning rate), achieving to RMSE reduction using a chaotic Sierpinski triangle-based search.

-

Synergistic Hybrid Model Design: Combines SVR’s margin-based regression, MLP’s non-linear pattern recognition, and GBM’s error correction in HFANN, yielding superior R2 and RMSE as low as.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Method” details the proposed Hybrid Fuzzy Artificial Neural Network (HFANN) methodology, including fuzzy preprocessing and chaos game optimization. Section “Material initialization” presents the dataset characteristics, preprocessing steps, and evaluation metrics. Section “Performance analysis” discusses performance results, statistical, and comparative analyses with existing models. Finally, Sect. “Conclusion” concludes the study with a summary of contributions, limitations, and recommendations for future research.

Research significance

Accurate prediction of high-performance concrete hardness properties, such as compressive strength and slump, remains a challenge because of the intricate, non-linear relationships between material constituents, mix proportions, and curing conditions. Existing statistical and single-model machine learning approaches often fail to capture these complex interactions, are sensitive to measurement variability, and lack mechanisms to model the uncertainty inherent in material properties and experimental data. In addition, conventional ensemble techniques rarely incorporate fuzzy logic for uncertainty handling, and they seldom employ advanced metaheuristic optimization strategies to refine model hyperparameters and ensemble weights systematically. The proposed HFANN addresses these limitations by integrating fuzzy logic-based preprocessing with high-performing learners, namely Support Vector Regression (SVR), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), which are optimized using the Chaos Game Optimization (CGO) algorithm. This combination allows the model to manage uncertainty, take advantage of complementary learning strengths, and achieve superior predictive accuracy compared to traditional and existing hybrid methods.

The findings of this study contribute to the state of the art by demonstrating substantial improvements in predictive performance, including up to a 25% reduction in RMSE for compressive strength and R² values as high as 0.98 for compressive strength and 0.97 to 0.99 for slump across all evaluation phases. These results not only validate the methodological novelty but also provide practitioners with a robust, uncertainty-aware tool for optimizing HPC mix designs. By doing so, the research advances both the theoretical understanding and the practical capabilities in sustainable construction engineering, offering insights applicable to real-world structural design scenarios such as long-span bridges, high-rise buildings, and infrastructure in extreme environments.

Method

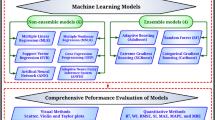

The structure of the proposed method is shown in Fig. 1. In the proposed approach, SVR, MLP and GBM are used as predictive models, and a Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) is included to process the uncertain data before it is used. Raw inputs are changed into fuzzy features, where each number is assigned a value of membership in linguistic terms. The inputs’ vague and ambiguous elements are included alongside the exact data points, or they are used rather than the exact details52. With the hybrid approach, SVR, MLP and GBM use their strong points, and this makes the model more flexible and reliable. To make the model work even better, the CGO algorithm is used to change the hyperparameters and coordinate the hybrid learners. CGO examines a lot of possible solutions, making training the model better and reducing its prediction errors. This integrated pipeline enables accurate and uncertainty-aware prediction of HPC properties such as compressive strength and slump. The preprocessed dataset, augmented with 18 fuzzy features per sample dataset (total 25 features: 7 crisps + 18 fuzzy), is split into training, validation, and testing sets. The augmented input vectors are fed into GBMC, SVRC, and MLPC, trained with CGO-optimized hyperparameters. The GSMA ensemble combines predictions using CGO-optimized weights53. It should be noted that in this method conventional normalization techniques such as Min–Max or Z-score scaling were not required before modeling. The fuzzy preprocessing stage transforms each crisp input variable into membership degrees within Gaussian fuzzy sets, with values bounded between 0 and 1. This mapping inherently scales all input features to a comparable range, thereby mitigating potential bias from differing magnitudes. The predictive models operate on the augmented feature set containing both the fuzzified and original crisp features, with the CGO-driven hyperparameter tuning further adapting the models to the input scale.

Also, to mitigate the risk of overfitting in the proposed model (HFANN), several strategies were applied. First, the dataset was split into independent training and testing sets to ensure that model evaluation was performed on unseen data. Second, a k-fold cross-validation procedure was employed during the hyperparameter tuning stage to confirm stability and generalization across multiple random partitions. Third, model complexity was controlled by selecting only the most relevant features through the fuzzy feature generation and selection process, thereby reducing noise and dimensionality. Finally, performance metrics such as RMSE, MAE, and R² were consistently monitored for both training and testing phases to detect signs of overfitting, following best practices reported in similar high-performance concrete prediction studies54,55.

Fuzzy preprocessor

For improving the HFANN methodology we incorporate a Fuzzy Logic System (FLS) in the preprocessing phase to manage uncertainties inherent in the input data. The efficacy of fuzzy logic in managing vagueness and uncertainty is significantly contingent upon the suitable distribution of membership functions, the quantity of rules, and the selection of acceptable fuzzy set operations. Initially, the preparation of the HPC dataset happens along with setting up the input variables for this phase. Statistical findings suggest that measurements, different materials, and external factors not in the dataset could be the reason for big variation among these values56. To deal with such uncertainties, FLS is applied to convert raw data into a form that shows imprecise and vague measurements. Before inputting the information, the FLS makes the data less specific, applies a rule system, then adds membership degrees as new features, and sends all these to hybrid predictive modeling block with the initial information. An enhancement by FLS during preprocessing gives HFANN more robustness, because the extra features measure uncertainty in data and make the models more flexible in real life. In the following paragraphs, we will show a comprehensive account of how the FLS helps in the preprocessing stage by explaining its functions, how it is implemented, and its incorporation with the available dataset.

During the first phase of the FLS, fuzzification takes crisp input data and makes them into fuzzy numeric values to better deal with unclear situations. Every input variable is identified using terms like low, medium, or high, that are modeled with smooth Gaussian functions. Such characteristics are represented in fuzzy sets by using their membership functions, as shown in Eqs. (1), (2) and (3) for instance.

where x is the W value, clow , cmedium and chigh are centers based on dataset statistics, and σ is a width parameter tuned to ensure overlap (e.g. half the standard deviation of W). This overlap allows a single ‘W’ value to belong partially to multiple sets, reflecting uncertainty in precise categorization. Similarly, SF and SP are fuzzified with tailored membership functions based on their statistical ranges.

Generation of membership and rules

The fuzzified inputs produce membership degrees for each linguistic term, serving as new features. For each sample, the input vector of seven crisp values (C, W, BFS, FA, CA, SP) is augmented with membership degrees for each fuzzy set, yielding 18 additional features (6 inputs × 3 terms). These features capture the degree of uncertainty in input measurements, enabling predictive models to account for variability that crisp values might overlook. A ‘W’ of 30% near the “medium” and “high” boundary provides nuanced information through its membership degrees, enhancing model robustness to measurement errors or material variations. The total of 18 fuzzy features arises from representing each of the six input variables with three Gaussian membership functions (low, medium, high), which is a common choice in fuzzy modeling to capture low, intermediate, and high states without excessive redundancy. Preliminary tests with two terms (12 features) reduced resolution and degraded accuracy, while four terms (24 features) increased dimensionality without meaningful performance gains. The chosen three-term scheme provided the best trade-off between capturing uncertainty, maintaining computational efficiency, and preserving predictive accuracy.

Also, a Sugeno-type rule base is constructed to model relationships between fuzzified inputs and outputs, guiding the FLS’s preprocessing role. Rules are derived from data correlations, such as Eq. (4). The Sugeno inference method54, also known as Takagi-Sugeno-Kang (TSK) inference, is a key component of the FLS employed in the preprocessing phase of the HFANN methodology.

a1, a2, and b are coefficients refined during the training process. A complete rule base with seven inputs and three fuzzy sets might encompass 2,187 rules; however, computational efficiency is preserved by choosing 50 to 100 rules depending on prevalent input combinations or feature significance. These criteria guide the inference process for validating fuzzification but are not employed for direct predictions during preprocessing.

The Sugeno inference method analyzes the rule base, calculating a fuzzy output for each sample. The firing strength of each rule is determined by the minimum of the membership degrees of its input conditions; for instance, for W (high) and SF (low), this is illustrated in Eq. (5).

The rule’s output is a linear function evaluated at crisp inputs, and the aggregated fuzzy output is a weighted average. In preprocessing, HFANN uses inference to validate the rule base’s consistency with the dataset, ensuring meaningful fuzzified features. Rule coefficients are optimized using least-squares on the training set, confirming that FLS captures realistic input-output relationships.

Defuzzification

While defuzzification is not the primary focus in preprocessing, centroid defuzzification is applied to compute tentative CS and slump flow values for validation as show in Eq. (6).

where wi is the firing strength, and yi represents the output of the rule. The results are juxtaposed with actual outputs to verify that the FLS models appropriately represent uncertainties. This stage verifies the membership degrees prior to their submission to the predictive models.

Chaos game optimizer (CGO)

The CGO algorithm follows the chaos game idea in the chaos theory and arranges the fractals accordingly. First, solutions are generated at random in a chaotic search area that follows the Sierpinski triangle structure. By doing so, the algorithm can find a wide range of starting points to look for nonlinear connections between variables in the HPC dataset. The fractal and self-similar shape of the Sierpinski triangle structure makes the chaotic search stage of CGO better. This shape breaks the search space down into smaller and smaller equilateral sub-triangles, which makes a hierarchical sampling technique possible. The candidate points that come out of this process are made at different scales. Larger triangles allow for broad global exploration, while smaller nested triangles allow for fine-grained local refinement. This automatically sets up a search process that goes from coarse to fine without the need for any further control factors. The fractal geometry also makes sure that the search locations are evenly spread out across the space. This balanced coverage cuts down on gaps that aren’t visited and stops solutions from clustering together, which can happen in searches that are completely random and chaotic. The technique keeps candidate solutions diverse throughout time by putting points in distinct sub-regions of the Sierpinski pattern. This variety slows down premature convergence and makes it less likely that the search will become stuck in local optima. Also, even though the Sierpinski sequence follows deterministic fractal laws, when it interacts with chaotic maps like logistic or tent maps, it adds controlled randomness. This hybrid behavior combines the methodical coverage of deterministic patterns with the unpredictability of chaos. It strikes a balance between exploring new areas and taking advantage of promising ones. Previous research, including57,58, has shown that this method speeds up convergence and enhances the quality of the solutions in metaheuristic optimization.

In the beginning, the CGO algorithm has a population of 30 solutions that give the suggested settings for hyperparameters or weights in the predictive models (GBM, SVR, and MLP) or the ensemble model (GSMA). For the single GBM model, the hyperparameters are the number of trees, the maximum depth, and the learning rate that manage the ensemble’s complexity, development, and joining together57. The parameters for SVR are the regularization constant, epsilon, and gamma for the radial basis function (RBF) kernel, and they decide how well and nonlinearly the model works. In MLP, having fewer or more hidden layers, neurons in each layer, deciding on the learning rate, and activation function, describe the structure and way a neural network learns. There are three weights (w₁, w₂, w₃) added together to reach 1, expressing how GBMC, SVRC, and MLPC add up to the solution. Also, in order to ensure that the strong generalizability of the HFANN model is maintained and the risk of overfitting is minimized, a 5-fold cross-validation method was used in the hyperparameter optimization stage using the CGO algorithm. In this approach, the educational data were randomly divided into five equal times. In each iteration, four folds were used to train the model while the remaining fold acted as the validation set, rotating in such a way that each fold acted as the validation set exactly once. Performance criteria were averaged from each of the five replications to evaluate the candidate hyperparameter configuration. This repeated validation process enables the selection of hyperparameters that are performed continuously across multiple partitions, reducing the sensitivity to splitting specific data, and improving the robustness of the final model.

Solution generation

To foster broad exploration and prevent convergence to local optima, CGO utilizes a logistic map to produce chaotic sequences that direct the parameter search59. The logistic map generates deterministic yet unpredictable sequences, allowing CGO to evaluate various hyperparameter combinations for GBM, SVR, and MLP within HFANN. Normalized values are adjusted to defined parameter ranges by linear transformation. This tumultuous generation augments CGO’s capacity to traverse the intricate parameter space, by investigating various configurations essential for representing the variability of the HPC dataset as shown in Eq. (7).

where \(\:{x}_{i}\in\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\) represents a normalized parameter value, and r = 4 ensures chaotic behavior.

CGO incrementally updates solutions to equilibrate exploration and exploitation, hence optimizing hyperparameters for GBMC, SVRC, and MLPC, as well as weights for GSMA. The update rule combines the chaotic sequence with the impact of the global best solution, utilizing a dynamically changed step size to regulate the magnitude of updates. The optimal global solution denotes the hyperparameter configuration or weights that produce the minimum RMSE on a validation subset. The Eq. (8) allows CGO to effectively optimize parameters, improving predicted accuracy for CS (MPa) and slump flow (mm) within the HFANN approach.

Fitness function

The efficacy of each solution is assessed by reducing the root mean square error (RMSE) on the validation subset, verifying that hyperparameters correspond with prediction accuracy. Each solution is associated with a model (GBMC, SVRC, or MLPC) that is trained using designated hyperparameters, integrating FLS membership degrees as inputs to account for uncertainty in W, SF, and SP. In GSMA, the fitness function assesses the RMSE of the weighted aggregation of predictions. This approach compels CGO to refine parameters for elevated R² and diminished RMSE, consistent with HFANN’s objective of exceeding the performance. The formulation is shown in Eq. (9).

CGO performs iterations for 100 generations, refining the population and monitoring the global optimal solution with the minimal RMSE. Solutions are prioritized according to their efficacy, with high-performing solutions affecting future modifications. Upon completion of 100 iterations, the algorithm identifies the global optimal solution as the ideal hyperparameters for GBMC, SVRC, and MLPC, or weights for GSMA.

Gradient boosting machine (GBM)

GBM are applicable for regression and classification tasks. In the framework of a general regression problem, the training dataset R can be represented as delineated in Eq. (10):

\(\:\left({X}_{i},{Y}_{i}\right)\left(i=\text{1,2},\dots\:,n\right)\) represents the training dataset for the ith sample, with n indicating the total number of samples. Xi denotes the input data vector, while Yi signifies the output data values. This can be utilized to train a main learner W(X), using a specific learning algorithm58. The relative estimation error, e-i, for each sample is denoted in Eq. (11):

In Eq. (8), F represents the loss function, which has three alternatives: square decay, linear decay, and exponential decay. A basic linear loss function is utilized in Eq. (12):

Where \(\:A=max\left|{Y}_{i}-W{(X}_{i})\right|\) signifies the largest absolute estimation error over all samples.

The objective of GBM is to sequentially produce a series of weak learners, \(\:{W}_{c}\left(X\right)\). This is due to the presence of a singular weak learner that exhibits subpar performance. Let c={1,2,…,N}, then amalgamate them to formulate \(\:W{(X}_{i})\:\)via an adept learner employing combinatorial techniques. Regression difficulties pertain to combinatorial methodologies.

In Eq. (13), \(\:{x}_{c}\) determines the weights of the weak learner \(\:{W}_{c}\left(X\right)\) and \(\:w\left(X\right)\) represent the mean of all \(\:{x}_{c}{W}_{c}\left(X\right)\), also \(\:h\in\left(\text{0,1}\right)\) is the regularization parameter employed to mitigate overfitting concerns.

Weakness learners, \(\:{W}_{c}\left(X\right)\), and their corresponding weights, \(\:{x}_{c}\), are generated with a modified version of the original training data. This is accomplished using a procedure known as rebalancing59. This is achieved by adjusting the distribution weight of each sample based on the estimation error of the latest weak learner, \(\:{W}_{c-1}\left(X\right)\). Misestimated samples are assigned greater weight, hence receiving increased focus in the subsequent training phase. This is a recursive technique. At iterations c={1,2,…,N}, the weak learner obtains \(\:{W}_{c}\left(X\right)\), and the relative estimation error eci is calculated in accordance with Eq. (14). The cumulative error rate, rc, for this phase is:

Then the weight of weak learners represented in Eq. (15)

In addition, the distribution’s weight \(\:{v}_{c+1,i}\) for each sample in the next step of training represented in Eq. (16):

In Eq. (16), \(\:{v}_{c,i}\) and \(\:{x}_{c}\) represent two weights. \(\:{v}_{c,i}\) signifies the significance of the training data samples employed to augment the weight of misestimated samples, indicating that the subsequent phase will aim for acceptability in learning. \(\:{x}_{c}\) is employed to identify weak learners, establishing that more precise weak learners exert a greater influence on the final output.

Figure 2 presents the of the GBM modeling operations. The process commences with a dataset employed to train the initial decision tree (Tree 1). The preliminary model generates predictions, and the inaccuracies (incorrect predictions) are recognized. A second tree (Tree 2) is subsequently trained to forecast the residual errors (discrepancies between actual and forecasted values) of the first tree. This procedure proceeds recursively, with each consecutive tree trained on the errors of the existing ensemble. Each tree is allocated a weight (w1, w2, …, wn) that influences the ultimate forecast. These trees are interdependent and constructed sequentially, with each subsequent tree enhancing the aggregate prediction of all preceding trees. The final output is the ensemble prediction, which consolidates the weighted outputs of all trees, thereby minimizing the overall error. The application of residuals and weighting allows GBM to effectively minimize loss function, resulting in excellent accuracy for both regression and classification applications.

Support vector regression (SVR)

In contrast to conventional regression models, SVR does not compute loss as long as the data remains within the specified margin. The loss function in Eq. (17) is evaluated solely when the Euclidean distance between the fitted curve function f(x) and the label y exceeds the error tolerance threshold ϵ. Consequently, the primary optimization objective is to maximize the margin L (minimizing ∥w∥²) while minimizing the loss function.

Where k represents the penalty parameter and \(\:{\delta\:}_{x}\) is the \(\:\delta\:\)-insensitive loss function, which is defined as Eq. (18).

The objective of a support vector regression machine is to identify a hyperplane by linear regression. Nevertheless, the majority of challenges faced in practical applications are non-linear. The purpose of the kernel function is to transform data points that cannot be separated or represented by linear equations into a higher-dimensional space, enabling SVR to identify a hyperplane through linear regression. This study use the Gaussian radial kernel function, defined as Eq. (19).

In this paper we use R2 coefficient to evaluate prediction outcomes, defined as Eq. (20).

The proximity of the upper R squared to 1 indicates a superior fit of the model to the curve, but a value closer to 0 signifies that the model’s predictions are nearer to the average, hence diminishing its predictive utility. The research indicates that the primary parameters for establishing the SVR are the penalty parameter C, the error tolerance threshold ϵ, and the coefficient of the kernel function’s exponential term equals to \(\:\left(\frac{1}{2{{\upsigma\:}}^{2}}\right)\). This research uses the violent search strategy for parameter selection due to the limited sample size. The output for the penalty parameter C is the number of upper R-squared values achieved when the parameter is varied within the interval (100, 1000) in increments of 50. The output for the error tolerance threshold ϵ is the upper R-squared value calculated over the interval (1,10) with a step size of 1. The kernel function coefficient γ yields the R2 value derived from the interval (1,10) in increments of 1. The parameter is determined by picking the R2 value, which has the greatest score.

Multilayer perceptron

MLP is an artificial neural network designed for the forward transmission of information, comprising several layers of nodes, each fully interconnected with the subsequent layer. Besides the input node, each node functions as a neuron equipped with a non-linear activation function. The network is often trained by error backpropagation to derive the gradients of the parameters, which are then optimized using a gradient descent technique. The used MLP Architecture is shown in Fig. 3.

The network’s input is vector x. It is multiplied by the weight matrix of the buried layer, IW. In the subsequent phase, the bias bh is incorporated into the outcome vector. Subsequently, the hyperbolic tangent activation function is employed. This can be articulated by Eq. (21).

Vector yh represents the output of the hidden layer. It is multiplied by the output layer’s weight matrix, LW. Similarly, bias b0 is incorporated. The sole distinction lies in the activation function, which, in this instance, is a linear function. The network’s final output is represented by Eq. (22).

This article utilizes a neural network architecture of four hidden layers, each containing 96 neurons, and incorporates an L2 regularization term of 0.01 to mitigate overfitting; the output layer consists of a number of neurons equal to the four labels. To achieve non-linear fitting capability, an activation function must be incorporated into the neurons of the MLP, with ReLU being the activation function utilized in this research, described as Eq. (23).

For the loss function we use Mean Squared Error (MSE) that defined as Eq. (24)

Where yi is the actual value and \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is predicted value from MLP. In critical regression situations, MSE strongly punishes bigger mistakes than MAE does, directing the model to reduce the high errors in its predictions. The method also gives neural networks a smooth and easy-to-optimize surface, making it easier to use backpropagation and similar learning algorithms. Being the variance of prediction errors makes it easy to test and compare models used in scientific settings.

Training optimization

The optimizer of the training model is a significant parameter. The core of the optimizer is the gradient descent algorithm; however, due to the intricate architecture of the neural network, the conventional gradient descent technique proves ineffective. For this reason, the Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) solver, is chosen by many as a popular optimization technique while training neural networks. The Adam optimizer is a first-order, gradient-based technique intended for the training of deep learning models. It amalgamates the benefits of Momentum, which enhances gradient descent by considering historical gradients, and MLP, which customizes the learning rate for each parameter by dividing by the square root of recent squared gradients. Adam is especially adept at handling non-stationary, noisy, and sparse datasets, rendering it highly efficient for intricate modeling jobs like predicting the mechanical properties of high-performance concrete. At each iteration t, Adam performs as Eqs. (25), (26), (27), (28) and (29).

(a) Gradient Computation

(b) Exponential Moving Average of the Gradients (First Moment Estimate)

(c) Exponential Moving Average of the Squared Gradients (Second Moment Estimate)

These moving averages are biased toward zero at initial time steps, so bias-correction is applied:

(d) Bias Correction

(e) Parameter Update Rule

Where:

-

η is the learning rate (typically 0.0010.001).

-

\(\:\widehat{{m}_{t}}\) provides a bias-corrected momentum estimate.

-

\(\:\widehat{{v}_{t}}\) provides a bias-corrected scaling factor based on recent gradient magnitudes.

Material initialization

An initial dataset is necessary for evaluating model performance. The main dataset of 191 HPC mixtures was obtained from the appropriate research60. Also, to ensure input-domain adequacy, we followed recent practice in civil and structural ML studies that audit dataset representativeness before model benchmarking. In particular, we adopted the coverage-checking procedures reported by Zhou et al.61 and Asteris et al.62. These studies emphasize that representative coverage of the parameter space is a prerequisite for reliable predictive modeling. Table 1 delineates the attributes of the inputs utilized for modelling and the corresponding outputs. Values are summarized from the 191-sample dataset; the complete dataset ranges and descriptive statistics are fully available in reference60. Representative coverage checks follow the approaches reported in61,62.

The evaluation of slump strength properties for high-performance concrete samples was performed after 182 days. Moreover, a grain size of 7.5 and a specific density of 2.8 for coarse aggregates obtained from crushed granite measuring 20 mm were employed in the studies. Portland cement was selected in compliance with ASTM standard Type I. Naphthalene-based superplasticizer was employed to reduce water content and control the water-to-binder ratio. Aggregates comprise fine silica sand with a specific gravity of 2.57 and a fineness modulus of 2.92. The slump test adhered to ASTM C143 criteria after rapid mixing per ASTM C39 guidelines.

To analyze the variables in the collected dataset, we performed a statistical analysis using box plots. The box plots of the concrete composition, i.e., cement, slag, fly ash, aggregate, sand, and water, are shown in Fig. 4. The cement (C) and coarse aggregate (CA) contents in the HPC data varied significantly, with values ranging from 70 to 576 kg/m³ and 723 to 1218 kg/m³, respectively. In the C content, very few outliers were detected, while in the CA content, no outliers were detected. Additionally, the sand (S) content ranged widely from 510 to 973 kg/m³, with outliers detected below the lower limit. This is due to the high replacement of sand content with fly ash in the dataset63,64. Outliers were also noticed in the blast furnace slag (BFS) and fly ash (FA) contents, which ranged from 0 to 342 kg/m³ and 0 to 305 kg/m³, respectively. The ranges of water (W) and age (A) were narrow, at 105 to 263 kg/m³ and 1 to 182 days, respectively. These ranges conformed to the accepted norms for both variables. The lowest range was for SP (0 to 23 kg/m³), as it was used in small quantities for HPC preparation. It is noteworthy that the wide and diverse range of input features in the compiled dataset indicates that the model can learn and generalize well.

Also, in Fig. 5 the Pearson correlation heatmap of the HPC data is shown. the Pearson correlation heatmap is an important tool for evaluating the suitability of a predictive method because it visually shows the strength and direction of linear relationships between all variables in the dataset. In the case of the HPC data, the heatmap reveals that while some input variables have relatively strong correlations with the outputs, many others have weak or moderate correlations, and some even show opposite relationships depending on the target variable. It also shows that several input variables are correlated with each other, indicating multicollinearity, which can make simpler models unstable. These patterns suggest that the dataset contains complex and non-linear interactions that cannot be fully captured by traditional regression or single-model approaches. The proposed HFANN method is better suited for this scenario because it combines fuzzy preprocessing to handle uncertainty, multiple non-linear learners to detect hidden patterns, and chaos-optimized ensemble weighting to manage redundancy and conflicting relationships. This allows the model to extract meaningful predictive power even when the direct linear relationships shown in the heatmap appear weak or mixed, making it more accurate and reliable than simpler alternatives.

Evaluation metrics

The subsequent indicators are employed to assess the efficacy of the pertinent models. The indicators comprised the mean absolute error (MAE), coefficient of determination (R²), root mean squared error (RMSE), variance account factor (VAF), objective detection metric (OBJ) and A20 index, calculable by Eqs. (30)-(34).

where \(\:{n}_{d}\) determines the measured value, \(\:\stackrel{-}{n}\) is the mean of the measured value, d shows the samples’ number, \(\:{c}_{d}\:\)indicates the predicted value, \(\:\stackrel{-}{c}\) determines the mean of the predicted values, and\(\:\:D\) is the data set’s number. Also, The A20 index quantifies the percentage of predictions whose absolute relative error does not exceed 20% of the experimental value. For a dataset of size N, with measured values \(\:yi\) and predictions \(\:{y}^{i}.\) We include A20 alongside RMSE and R², since it reports the share of practically acceptable predictions, which is widely used in engineering prediction studies. Also, RMSE is reported in the same physical units as the target variable, MPa for compressive strength and mm for slump, and MAE follows the same convention.

Performance analysis

Figure 6 illustrates the performance of HFANN during its initial phase, examining various learning percentages. This investigation underscores the influence of different learning percentages on the efficacy of the HFANN model during its preliminary development. Analyzing these performance metrics allows to enhance the model’s learning process. The analysis illustrates that the HFANN attains exceptional results across all areas. The test is performed by modifying the learning rate, models, and performance measurements. The performance metrics indicating favorable results include the Net Present Value (NPV) and the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC). Furthermore, the adverse metrics, including False Positive Rate (FPR), False Negative Rate (FNR), and Negative Predictive Value (NPV), are evaluated. The performance disparity relative to other models is evaluated.

FPR depicted in Fig. 6 (a) is 18%, 10%, 10%, 36%, and 10% higher than the RBFN, L.R, R.F, CNN, and GBM algorithms, respectively, at an 80% learning percentage. Moreover, according to the data presented in Fig. 6(b), the false negative rate (FNR) of the HFANN approach, upon reaching 80% of the learning process, is 50% more effective than both the RBFN and CNN algorithms.

Furthermore, the data illustrated in Fig. 6 (c) demonstrates that the NPV model utilized at the 80th learning percentage shows improvements of 20%, 10%, 10%, 27%, and 11% compared to the RBFN, L.R, R.F, CNN, and GBM algorithms, respectively. Figure 5(d) demonstrates that at an 80% learning rate, the FDR scheme surpasses the RBFN, L.R, R.F, CNN, and GBM algorithms by 20%, 10%, 11%, 31%, and 11%, respectively.

Figure 6 (e) indicates that at the 50% learning stage, the HFANN scheme outperforms the RBFN, L.R, R.F, CNN, and GBM algorithms by 40%, 20%, 25%, 46%, and 8%, respectively, in terms of MCC. The results demonstrate the efficacy of the proposed HFANN algorithm in accurately evaluating the evaluation of high-performance concrete hardness properties. This success can be attributed to the algorithm’s ability to effectively model complex nonlinear relationships within the dataset. As a result, HFANN not only enhances prediction accuracy but also provides valuable insights into the factors influencing the hardness properties of high-performance concrete.

MANOVA and tukey’s HSD test

To evaluate the significance of the reported enhancements, the results obtained from several iterations of each method were analyzed statistically using IBM SPSS V.26. Additionally, in conjunction with the typical calculation of descriptive statistics (mean ± SD), MANOVA and Tukey’s test were performed for each evaluation metric (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, and AUC) to ascertain any significant differences in the comparisons conducted. The selected significance level was 0.05. The MANOVA test aims to determine whether there is a significant difference among the outcomes. Tukey’s HSD test facilitates the comparison of each pair of means, allowing us to ascertain whether pairs have a significant difference. The results obtained from the MANOVA analysis are displayed in Table 2.

The MANOVA test results, presented in Table 3, indicate statistically significant differences among the means of the analyzed algorithms across all metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, and AUC. To conduct a pairwise analysis for further research, it is necessary to run the Tukey’s HSD test. The importance of the disparity between each algorithm pair presented in Table 4 was analyzed utilizing the HSD test. For this segment of the statistical analysis, we concentrate exclusively on assessing the difference between the strategy that has yielded the most favorable results and its alternative methods. Table 3 presents the outcomes of the HSD test for three pairs, encompassing the proposed method and its nearest rivals. The table emphasizes the principal metric Q, commonly referred to as the studentized range statistic. Q is determined using the pair of mean values under examination.

The results of Tukey’s HSD test reveal a significant difference between the superior outcomes achieved by HFANN and those of its equivalents in most instances. However, there were a few instances where the difference was not deemed substantial. These exceptions arose for the RBFN and CNN algorithms. The Tukey’s HSD test indicated that the enhancement in precision attained by the suggested method relative to the RBFN method is not statistically significant. A comparable scenario is noted regarding the discrepancies between the outcomes of the HFANN and CNN algorithms, specifically with Precision and F1, which were statistically significant.

Slump and compressive strength analysis

This study evaluated individual, hybrid, and ensemble models via three phases: Training, Validation, and Testing. The dataset had 191 samples, distributed as 72% for training, 16% for validation, and 16% for testing, respectively. For optimal evaluation metrics, R² and VAF should reach their maximum values, nearing 1 and 100%, respectively, while values nearing 0 for RMSE and MAE indicate small errors, RMSE and MAE are in MPa for compressive strength and in mm for slump, and OBJ indicates acceptable model errors.

The RBFN model attained a R² value of 0.95 during the training phase, which remained rather consistent in the validation and testing stages, yielding values of 0.94 and 0.95, respectively. In LR, the training section value was 0.95, but the validation and test values exhibited a minor decrease, recorded at 0.94 and 0.94, respectively. GBM attained the high R2 values among individual models, registering 0.98 in training and 0.99 in validation, the values nearest to 1 among the diverse models. The advantageous effect of HFANN model was clearly evident, yielding 8% increase in RBFN and a 5% in LR. Nonetheless, against GBM, progress has been minimal, resulting in only slight growth. The variation in R² values among the HFANN was negligible; nevertheless, the HFANN model consistently shown the highest value. The DGT model, attained a score of 0.97, with validation and testing scores of 0.97 and 0.98, respectively. In the thorough assessment of the models for R², it was discovered that HFANN attained the greatest value. The best values for the VAF metrics were 1.26 that achieved with the HFANN during test stage. The least effective performance was linked to RBFN, which attained the highest value in all three categories. GBM outperformed in the training area across two stages, resulting in enhanced values in validation and testing. The subsequent study of VAF revealed the most favorable value of 99.52, assigned to HFANN in the test phase. The lowest amount in the test stage related to RBFN was 91.65. Ultimately, unlike other evaluators that attained a suitable value for HFANN, OBJ produced the most advantageous value, whereas RBFN registered the least favorable result. The optimal values for HFANN were attained. The evaluation criteria findings for the prediction models are presented in Tables 4 and 5.

The R² for slump modeling demonstrated that the RBFN model attained a value of 0.95 during the training phase, which significantly diminished in the validation and test phases, resulting in values of 0.91 and 0.78, respectively. The training score for LR was 0.94, and the validation and testing scores were 0.93 and 0.87, respectively. GBM achieved scores of 0.98 for training and 0.89 for testing, respectively. Compared to these models, the proposed method, HFANN was significantly more optimal, compared to RBFN by 14% during training and LR by 8% in the overall average. Ultimately, DGT may achieve a value of 0.96 in the training phase, while the validation and testing segments recorded values of 0.94 and 0.93, respectively. In the extensive model comparison for R² of the slump, it can be asserted that CNN and RBFN exhibited the highest value. The highest values for RMSE and MAE were 10.19 and 7.33, respectively, linked to CNN in validation phase and RBFN in the test phase. RBFN and GBM got the highest scores of 7.18 and 7.54, respectively, in the testing phase. The maximum score for VAF was 99.65, linked to the HFANN test component. RBFN achieved the lowest score of 88.24 in the test of VAF stage. Ultimately, for OBJ, akin to other evaluators who received favorable ratings on the HFANN, this rater also obtained a respectable score of 4.24.

As shown in Tables 4 and 5, A20 values are consistently high, which reflects that model errors are small relative to the magnitude of the measured responses. The A20 index reports the percentage of predictions whose absolute relative error is within 20% of the measured value. It is an acceptability rate, so higher is better65,66. In our results, A20 tracks the practical usefulness of each model while complementing RMSE and R². HFANN achieves very low errors in all splits, RMSE as low as 1.26 MPa on the test set with R² around 0.98. This yields A20 values at or near 100% across train, validation, and test, which means almost every HFANN prediction falls within the ± 20% acceptance band. Competing models show higher RMSE and correspondingly lower A20, for example RBFN has test RMSE of 14.59 MPa and therefore many more predictions outside the band, which is reflected in a substantially smaller A20. GBM and RF come closer to HFANN, however their higher errors in at least one split reduce their A20 slightly below HFANN. These relationships are consistent with the base metrics already reported in Table 4. For slump, several models already achieve small absolute errors relative to the 20% band, so A20 values cluster near 100%. Even in this saturated regime, HFANN remains at the top or statistically tied with the best competitors across splits, in line with its strong RMSE and R² in Table 5. Where other methods, for example GBM, exhibit larger test RMSE, their A20 correspondingly dips, while HFANN maintains a higher or equal A20. Also, HFANN’s A20 stays uniformly high in training, validation, and testing, which indicates stable generalization rather than split-specific tuning. Methods with larger validation or test errors show visible A20 drops in those phases, which matches the pattern seen in their RMSE and R².

Uncertainty analysis

In predictive modeling for construction materials, notably HPC, precision isn’t enough to judge the model. A model that performs well on one dataset split may nevertheless be unreliable if its predictions change a lot when the sampling conditions change or when it sees data it hasn’t seen before. Uncertainty analysis determines this reliability by assessing the variability of essential performance measures across multiple resampling experiments. We used a bootstrap-based uncertainty analysis with 1,000 iterations for each dataset split (training, validation, and testing) in this study. During each iteration, samples were selected with replacement, the HFANN ensemble was re-calibrated, and the resulting RMSE, MAE, and R² values were recorded. We then found the mean, standard deviation (SD), and 95% confidence intervals based on percentiles for each metric. This process allows us to assess the stability and generalization consistency of HFANN, ensuring that its strong performance is not the result of random chance or overfitting to a specific data configuration.

The results of the bootstrap-based uncertainty analysis for compressive strength and slump predictions using HFANN are presented in Tables 6 and 7, respectively. These tables summarize the mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals for RMSE, MAE, and R² across 1,000 resampling iterations. The consistently small standard deviations and narrow confidence intervals across all dataset splits demonstrate that HFANN produces stable and reliable predictions, reinforcing its suitability for practical HPC applications where input variability and measurement uncertainty are common.

The uncertainty analysis findings show that the proposed HFANN is very stable and strong when predicting both the compressive strength and slump of high-performance concrete. The performance measures (RMSE, MAE, and R²) exhibit narrow confidence intervals and very modest standard deviations throughout 1,000 bootstrap rounds and all data splits. This means that the model outputs don’t change much even when the training data composition varies. The average RMSE for compressive strength tests is about 1.33 MPa, with a 95% CI that only covers 1.06–1.70 MPa. The R² value stays high at about 0.982. This means that the model not only makes very few mistakes while predicting, but it also stays accurate with great consistency. The same thing happens with slump predictions: R² stays near to 0.97 on the test split, and RMSE variability is low, even though slump observations are noisy by nature.

These results show that HFANN’s design, which combines fuzzy preprocessing with optimized SVR, GBM, and MLP learners, is good at dealing with uncertain input and using the strengths of the base models. The fuzzy logic step makes sure that changes in the characteristics of the materials and errors in measurements are included as useful features. The Chaos Game Optimization stage fine-tunes the hyperparameters and ensemble weights to get the best balance between bias and variance. HFANN is a reliable tool for real-world HPC mix design where data fluctuation and uncertainty are inescapable since it is more accurate and reliable than other solo models.

Conclusion

This study introduces a new Hybrid Fuzzy Artificial Neural Network (HFANN) framework for predicting the hardness properties of high-performance concrete, such as compressive strength and slump. It does this by combining fuzzy logic with hybrid SVR, MLP, and GBM models, which are then optimized using the CGO algorithm. The FIS system uses gaussian membership functions and a fuzzy rule base to turn inputs like water-to-binder ratio, silica fume, and superplasticizer into 18 fuzzy features per sample. This is an effective way to deal with data uncertainties. CGO’s disordered search, which uses the Sierpinski triangle and logistic map, improves hyperparameters and ensemble weights. This leads to a 25% drop in RMSE for compressive strength compared to traditional models, which is a significant methodological advance. The HFANN framework combines SVR’s margin-based regression, MLP’s non-linear pattern recognition, and GBM’s sequential error correction in a way that works well. It has R2 values of 0.98 for compressive strength and 0.97–0.99 for slump, and RMSE values as low as 1.26 MPa and 4.17–6.12 mm across all three phases of training, validation, and testing. Thorough statistical validation applying MANOVA and Tukey’s HSD tests substantiates large increases, including an 8% R2gain over RBFN and 5% over LR for compressive strength, substantiated by a diversified dataset of 191 samples. This great performance lets engineers improve HPC mix designs for use in long-span buildings, bridges, and high-rise buildings, making them more durable and sustainable. While the hybrid machine learning model demonstrates strong predictive performance, its accuracy is influenced by the distribution and representativeness of the training data. If certain parameter ranges or extreme combinations are underrepresented, the model may struggle to generalize reliably in those regions. This sensitivity to data coverage is a common limitation of data-driven methods, as predictions are inherently tied to the patterns present in the available dataset rather than the complete theoretical design space. To mitigate this, future work should focus on expanding the dataset to include more diverse and extreme cases, ensuring broader coverage of potential high-performance concrete mix designs. In addition, generalizability to entirely new datasets or experimental conditions is not guaranteed. Changes in material properties, environmental conditions, or mix design practices that differ from the training data distribution could reduce model accuracy. Also, even while the study is making progress, it has certain problems, such as a dataset that only has 191 variations, which may not fully represent all HPC formulations or real-world circumstances, and a lot of computing complexity that could make it hard to use in real time. The fuzzy rule base only has 50 to 100 rules, thus it might not work with larger datasets. It also doesn’t take into consideration long-term durability issues like shrinkage or spalling. Future efforts should add to the dataset, improve algorithms for use in real time, create adaptive rule generation, predict durability characteristics, and include digital tools like BIM. This will improve this cutting-edge foundation and help to further change the way HPC prediction and construction engineering are done.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

An, M., Huang, H., Wang, Y. & Zhao, G. Effect of thermal cycling on the properties of high-performance concrete: microstructure and mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. 243, 118310 (2020).

Yan, X. & Lu, S. Developing a support vector regression model via optimization algorithms to appraise the hardness properties of high-performance concrete. Struct. Concrete. 24 (3), 4047–4063 (2023).

Xu, Y. & Afzal, M. Applying machine learning techniques in the form of ensemble and hybrid models to appraise hardness properties of high-performance concrete. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 46 (1), 903–921 (2024).

Lei, Y. Auto-regulated radial base function structure implementation in the hybrid and ensemble hybrid domains to assess the hardened properties of novel mixture high performance concrete. Struct. Concrete. 25 (5), 3804–3823 (2024).

Zhao, X., Li, F., Chen, B., Li, X. & Lu, S. Modeling the hardness properties of high-performance concrete via developed RBFNN coupling matheuristic algorithms. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 44 (3), 4801–4815 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Microstructure and radiation shielding properties of lead-fiber reinforced high-performance concrete. Ceram. Int. 50 (13), 23656–23667 (2024).

Dahlan, A. S. Impact of nanotechnology on high performance cement and concrete. J. Mol. Struct. 1223, 128896 (2021).

Qian, Y. et al. Numerical characterization and formation process study of rail light bands in high-speed turnout areas. Eng. Fail. Anal. 168, 109083 (2025).

Raza, S. S. et al. Effect of micro-silica on the physical, tensile, and load-deflection characteristics of micro fiber-reinforced high-performance concrete (HPC). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01380 (2022).

Zhang, W., Yang, X., Lin, J., Lin, B. & Huang, Y. Experimental and numerical study on the torsional behavior of rectangular Hollow reinforced concrete columns strengthened by CFRP. Structures 70, 107690 (2024).

Liu, F. et al. Improved thermal performance, Frost resistance, and pore structure of cement–based composites by binary modification with mPCMs/nano–SiO2. Energy 332, 137166 (2025).

Wang, J., Wu, Z., Han, J., Wang, G. & Lv, S. Experimental study on axial load-bearing capacity of grout-lifted compressible concrete-filled steel tube composite column. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 165, 106864 (2025).

Singaravel, D. A., Veerapandian, P., Rajendran, S. & Dhairiyasamy, R. Enhancing high-performance concrete sustainability: integration of waste tire rubber for innovation. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 4635 (2024).

Odeyemi, S. O. et al. Mechanical properties and microstructure of High-Performance concrete with bamboo leaf Ash as additive. Clean. Eng. Technol. 6, 100352 (2022).

Wu, H., Yang, D., Wang, C. & Ma, Z. Microstructural and macroperformance of recycled mortar with high-quality recycled aggregate and powder from high-performance concrete waste. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 35 (3), 04022482 (2023).

Gu, Z., Sun, X., Lam, H.-K., Yue, D., & Xie, X. (2022). Event-Based Secure Control of T–S Fuzzy-Based 5-DOF Active Semivehicle Suspension Systems Subject to DoS Attacks. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 30(6), 2032–2043. https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2021.3073264

Du, H. & Dai Pang, S. High-performance concrete incorporating calcined Kaolin clay and limestone as cement substitute. Constr. Build. Mater. 264, 120152 (2020).

Yan, S., Gu, Z., Park, J. H., & Xie, X. (2022). Adaptive Memory-Event-Triggered Static Output Control of T–S Fuzzy Wind Turbine Systems. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 30(9), 3894–3904. https://doi.org/10.1109/TFUZZ.2021.3133892

Taghavi Khangah, A. R., Khajavi, E., Azizi, H. & Alizade Novin, A. R. Radial basis function coupling with metaheuristic algorithms for estimating the compressive strength and slump of High-Performance concrete. Adv. Eng. Intell. Syst. 3 (04), 124–142 (2024).

Li, B. et al. Effect of superabsorbent polymers and expansive agent on the properties and microstructures of self-stressing high performance concrete. J. Building Eng. 78, 107663 (2023).

Chen, J. High-performance concrete compressive property prediction via deep hybrid learning. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 45 (3), 4125–4138 (2023).

Song, Y., Davy, C. A., Troadec, D. & Bourbon, X. Pore network of cement hydrates in a high performance concrete by 3D FIB/SEM—Implications for macroscopic fluid transport. Cem. Concr. Res. 115, 308–326 (2019).

Lu, J. X. et al. Influence of Spatial dislocation of water on the properties of lightweight high-performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 367, 130322 (2023).

Wenxin Zhang, Guangdeng Zong, Ben Niu, Xudong Zhao, Ning Xu, Adaptive fuzzy dynamic event-triggered control for PDE-ODE cascaded systems with actuator failures, Fuzzy Sets and Systems, 519(1): 109514, (2025).

Swaminathen, A. N., Kumar, C. V., Ravi, S. R. & Debnath, S. Evaluation of strength and durability assessment for the impact of rice husk Ash and Metakaolin at high performance concrete mixes. Mater. Today: Proc. 47, 4584–4591 (2021).

Aslani, F., Hamidi, F. & Ma, Q. Fire performance of heavyweight self-compacting concrete and heavyweight high strength concrete. Materials 12 (5), 822 (2019).

Olawuyi, B. J., Babafemi, A. J. & Boshoff, W. P. Early-age and long-term strength development of high-performance concrete with SAP. Constr. Build. Mater. 267, 121798 (2021).

Li, K. et al. A comprehensive benefit evaluation of recycled carbon fiber reinforced cement mortar based on combined weighting. Constr. Build. Mater. 489, 142196 (2025).

Cui, D. et al. Dynamic splitting performance and energy dissipation of Fiber-Reinforced concrete under impact loading. Materials 17 (2), 421 (2024).

Saravan, R. A. & Annadurai, R. Optimization and prediction of mechanical properties of high-performance concrete with steel slag replacement as coarse aggregate: an experimental study using RSM and ANN. Asian J. Civil Eng. 25 (1), 811–826 (2024).

Abbès, F., Abbès, B., Benkabou, R. & Asroun, A. A FEM multiscale homogenization procedure using nanoindentation for high performance concrete. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 6 (3), 493–504 (2020).

Mohana, R. & Bavithra, K. Influence of nano materials on the macro and micro structural behaviour of high-performance concrete using interfacial transition zone approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 397, 132465 (2023).

Li, W., Wang, R., Ai, Q., Liu, Q. & Lu, S. X. Estimation of compressive strength and slump of HPC concrete using neural network coupling with metaheuristic algorithms. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 45 (1), 577–591 (2023).

Qian, Y. et al. Prediction of Ultra-High-Performance concrete (UHPC) properties using gene expression programming (GEP). Buildings 14 (9), 2675 (2024).

Bader, T., Unterberger, S. H. & Lackner, R. Effect of substrate moisture on the weatherability of surface treatment for High-Performance concrete (HPC). Cem. Concr. Compos. 83, 57–65 (2017).

Kumar, S., Kumar, R., Rai, B. & Samui, P. Prediction of compressive strength of high-volume fly Ash self-compacting concrete with silica fume using machine learning techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 438, 136933 (2024).

Kumar, R., Rai, B. & Samui, P. Prediction of mechanical properties of high-performance concrete and ultrahigh‐performance concrete using soft computing techniques: a critical review. Struct. Concrete. 26 (2), 1309–1337 (2025).

Kumar, R. et al. Estimation of the compressive strength of ultrahigh performance concrete using machine learning models. Intell. Syst. Appl. 25, 200471 (2025).

Tahera, Urs, N. et al. Comparative analysis of sloshing effects on elevated water tanks’ dynamic response using ANN and MARS. Discover Mater. 5 (1), 9 (2025).

5 George, C., Kumar, R. & Ramaraju, H. K. Comparison of experimental and analytical studies in light gauge steel sections on CFST using SFRC in beams subjected to high temperatures. Asian J. Civil Eng. 26 (2), 667–681 (2025).

Satyanarayana, A., Dushyanth, V. B. R., Riyan, K. A., Geetha, L. & Kumar, R. Assessing the seismic sensitivity of Bridge structures by developing fragility curves with ANN and LSTM integration. Asian J. Civil Eng. 25 (8), 5865–5888 (2024).

Satyanarayana, A. et al. A multifaceted comparative analysis of incremental dynamic and static pushover methods in Bridge structural assessment, integrated with artificial neural network and genetic algorithm approach. Discover Mater. 5 (1), 84 (2025).

George, C. et al. Predicting the fire-induced structural performance of steel tube columns filled with SFRC-enhanced concrete: using artificial neural networks approach. Front. Built Environ. 10, 1403460 (2024).

Xiangjun Wu, Shuo Ding, Ning Zhao, Huanqing Wang, Ben Niu, Neural-network-based event-triggered adaptive secure fault-tolerant containment control for nonlinear multi-agent systems under denial-of-service attacks, Neural Networks, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2025.107725

Sathvik, S. et al. Analyzing the influence of manufactured sand and fly Ash on concrete strength through experimental and machine learning methods. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 4978 (2025).

Mahmood, W., Mohammed, A. S., Asteris, P. G., Kurda, R. & Armaghani, D. J. Modeling flexural and compressive strengths behaviour of cement-grouted sands modified with water reducer polymer. Appl. Sci. 12 (3), 1016 (2022).

Mahmood, W., Mohammed, A. S., Sihag, P., Asteris, P. G. & Ahmed, H. Interpreting the experimental results of compressive strength of hand-mixed cement-grouted sands using various mathematical approaches. Archives Civil Mech. Eng. 22 (1), 19 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. A generalized artificial intelligence model for estimating the friction angle of clays in evaluating slope stability using a deep neural network and Harris Hawks optimization algorithm. Eng. Comput. 38 (Suppl 5), 3901–3914 (2022).

Asteris, P. G., Lemonis, M. E., Nguyen, T. A., Van Le, H. & Pham, B. T. Soft computing-based Estimation of ultimate axial load of rectangular concrete-filled steel tubes. Steel Compos. Struct. Int. J. 39 (4), 471–491 (2021).

Niu, Y., Wang, W., Su, Y., Jia, F., & Long, X. (2024). Plastic damage prediction of concrete under compression based on deep learning. Acta Mechanica, 235(1), 255-266. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-023-03743-8

Asteris, P. G. & Mokos, V. G. Concrete compressive strength using artificial neural networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 32 (15), 11807–11826 (2020).

Zhang, W., Liu, X., Huang, Y. & Tong, M. Reliability-based analysis of the flexural strength of concrete beams reinforced with hybrid BFRP and steel rebars. Archives Civil Mech. Eng. 22 (4), 171 (2022).

Sapkota, S. C. et al. Optimizing high-strength concrete compressive strength with explainable machine learning. Multiscale Multidisciplinary Model. Experiments Des. 8 (3), 160 (2025).

Asteris, P. G., Skentou, A. D., Bardhan, A., Samui, P. & Pilakoutas, K. Predicting concrete compressive strength using hybrid ensembling of surrogate machine learning models. Cem. Concr. Res. 145, 106449 (2021).

Armaghani, D. J. & Asteris, P. G. A comparative study of ANN and ANFIS models for the prediction of cement-based mortar materials compressive strength. Neural Comput. Appl. 33 (9), 4501–4532 (2021).

Talatahari, S. & Azizi, M. Chaos game optimization: a novel metaheuristic algorithm. Artif. Intell. Rev. 54 (2), 917–1004 (2021).

Gao, D., Li, Z., Ding, C., & Yu, Z. (2025). Uniaxial tensile stress-strain constitutive relationship of 3D/4D/5D steel fiber-reinforced concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 470, 140539. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.140539

Liang, X., Wu, C., Su, Y., Chen, Z. & Li, Z. Development of ultra-high performance concrete with high fire resistance. Constr. Build. Mater. 179, 400–412 (2018).

Benaddache, L. et al. Comparative study on externally bonded heat-treated jute and glass fiber reinforcement for repair of pre-cracked high performance concrete beams. Archives Civil Mech. Eng. 24 (2), 82 (2024).

Chen, Y., Zhou, H. & Kang, X. Using the meta-heuristic algorithms to optimize the radial basis function for predicting high-performance concrete compressive strength and slump flow. Multiscale Multidisciplinary Model. Experiments Des. 7 (3), 2783–2796 (2024).

Zhou, J., Asteris, P. G., Armaghani, D. J. & Pham, B. T. Prediction of ground vibration induced by blasting operations through the use of the bayesian network and random forest models. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 139, 106390 (2020).

Sarir, P., Chen, J., Asteris, P. G., Armaghani, D. J. & Tahir, M. M. Developing GEP tree-based, neuro-swarm, and Whale optimization models for evaluation of bearing capacity of concrete-filled steel tube columns. Eng. Comput. 37 (1), 1–19 (2021).

Peng, Y. et al. Evaluation framework for bitumen-aggregate interfacial adhesion incorporating pull-off test and fluorescence tracing method. Constr. Build. Mater. 451, 138773 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Three-dimensional concrete printing technology from a rheology perspective: a review. Adv. Cem. Res. 36 (12), 567–586 (2024).

Le, T. T., Skentou, A. D., Mamou, A. & Asteris, P. G. Correlating the unconfined compressive strength of rock with the compressional wave velocity effective porosity and Schmidt hammer rebound number using artificial neural networks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 55 (11), 6805–6840 (2022).

Asteris, P. G. et al. AI-powered GUI for prediction of axial compression capacity in concrete-filled steel tube columns. Neural Comput. Appl. 36 (35), 22429–22459 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The 14th Five-Year National Key Research and Development Project “Key Technologies and Equipment for the Operation Safety of Super High-rise Buildings” (Project number: 2022YFC3801200)The 14th Five-Year National Key Research and Development Plan “Key Technologies and Equipments for Typical Risk Investigation and Safety Performance Enhancement of Super High-Rise Buildings” (Project Number: 2022YFC3002300) Topic 2: Research and Development of Technologies and Equipments for Main Structure Damage Rapid Identification, Diagnosis and Emergency Reinforcement of Super High-rise Buildings (Project No.: 2022YFC3002302).

Funding

The authors did not receive any financial support for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qian Li contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and manuscript writing. Qian Li played a key role in designing the experiments, analyzing the results, and drafting the initial version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions