Abstract

To describe the real-world efficacy and safety outcome measurements of faricimab use in treatment-resistant neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) in a cohort of Asian patients. A tertiary hospital in central Singapore serving a resident population of approximately 1.5 million. Retrospective chart review of patients with nAMD previously treated using intravitreal bevacizumab, ranibizumab or aflibercept and were switched to faricimab between August 2022 to August 2023. Patients were switched to faricimab due to either the ineffectiveness of prior anti-VEGF agents to achieve retinal dryness or inadequate treatment intervals. Only patients who had at least one follow-up visit after switching to faricimab were included in the analysis. Primary outcome measures included best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in ETDRS letter score and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) measurements including central subfield thickness (CST), presence or absence of intraretinal fluid (IRF), subretinal fluid (SRF), intraretinal cysts and subretinal hyperreflective material (SRHM). Secondary outcome measures included adverse events and treatment history such as the mean number of injections and treatment intervals. One hundred and nineteen eyes (117 patients) with a mean age of 75.6 (58–93 years) were switched to faricimab and included in the analysis. Of these, 55 (47.0%) were males. The mean number of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections received was 28.2 ± 19.5 prior to switching to faricimab. The majority of these were switched from ranibizumab (26.1%) and aflibercept (73.1%). At baseline, BCVA was 62.7 ± 19.9 letter and mean CST on OCT was 352.5 μm ± 128.5 μm. Only 11 (9.2%) eyes were dry on OCT at baseline: 39.5% had presence of IRF, 72.3% had presence of SRF, 41.2% had presence of intraretinal cysts, and 50.4% had presence of SRHM. After switching to faricimab, the eyes received a mean of 4.8 ± 2.7 faricimab injections up to the time of data cut-off. At last visit, the mean BCVA maintained at 60.3 ± 20.7 letter and mean CST reduction was − 41.6 μm (p < 0.001). Compared to baseline, 49 (41.2%) were dry on OCT: 24.4% had presence of IRF, 41.2% had presence of SRF, 29.4% had presence of intraretinal cysts, and 48.7% had presence of SRHM (all p < 0.001). No serious ocular adverse events were reported. Switching patients with nAMD to faricimab in real-world scenarios has demonstrated the ability to maintain vision while adding anatomical gains in those previously resistant to alternative anti-VEGF therapy. Faricimab is well-tolerated with no serious ocular adverse events reported.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of visual impairment in the elderly, with its global prevalence projected to reach 288 million by 20401. While no effective treatments were available for advanced AMD until the early 2000s, the introduction of intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents has revolutionized care for neovascular AMD (nAMD), which, despite affecting only 20% of AMD patients, causes 90% of severe central vision loss in affected patients2,3. Approved anti-VEGF drugs, such as ranibizumab, aflibercept, and brolucizumab, along with off-label bevacizumab, have significantly improved outcomes. However, the need for frequent, indefinite injections places a considerable burden on patients and healthcare systems, with the high injection frequency often affecting patient compliance and consequently treatment outcomes4.

Faricimab, the latest treatment approved by the FDA as of early 2022, is a dual-targeting monoclonal antibody designed to inhibit both VEGF-A and angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), key molecular pathways involved in neovascularization and vascular leakage5. Ang-2 is believed to play a significant role in destabilizing blood vessels and promoting increased exudation. By specifically targeting Ang-2 in addition to VEGF-A, faricimab seeks to offer a more comprehensive approach to preventing these processes while enhancing blood vessel stability6. Its efficacy has been demonstrated in the TENAYA and LUCERNE trials, where it was found to be as effective as aflibercept in improving best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at the primary endpoints (weeks 40, 44, and 48). Furthermore, both trials highlighted faricimab’s primary advantage: the ability to safely extend injection intervals beyond those of existing monospecific anti-VEGF therapies. Approximately 45% of patients maintained 16-week intervals between treatments, while nearly 80% achieved intervals of 12 weeks or longer7.

While the results are promising, these studies may not fully capture real-world scenarios. A notable limitation is their focus solely on treatment-naive patients with newly diagnosed nAMD. In clinical practice, many patients are already on anti-VEGF therapies but struggle with treatment-resistant disease activity8. Naturally, physicians are likely to prioritize switching these individuals—who face a significant treatment burden—to faricimab in hopes of reducing injection frequency. Moreover, real-world studies account for variations in physician practices, treatment protocols, and diverse patient populations, making them crucial for validating clinical trial outcomes in broader and more practical settings9,10,11,12. The TRUCKEE study serves as a notable example, extending the investigation to real-world patients receiving faricimab for nAMD treatment. This multicenter, retrospective chart review highlighted the maintenance or improvement of visual acuity in patients with nAMD, accompanied by a rapid enhancement of anatomical parameters13.

We aimed to evaluate the real-world efficacy and safety of faricimab use in a cohort of Asian patients with treatment-resistant neovascular AMD.

Methods

This study was a retrospective single-center (Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore) chart review of consecutive patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) previously treated using intravitreal bevacizumab, ranibizumab or aflibercept and were switched to faricimab between August 2022 to August 2023. We included all patients aged 50 years and older with a clinical diagnosis of exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD) or polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) with at least one follow-up visit after switching to faricimab. Patients with macular neovascularization secondary to other etiologies – such as high myopia, uveitis, trauma, angioid streaks, or inflammatory chorioretinopathies were excluded from the analysis. In addition, we excluded patients with ocular conditions that could significantly affect visual acuity or OCT interpretation, including diabetic macular edema, severe glaucoma, retinal vein occlusion, and significant media opacities that precluded high-quality OCT imaging. All patients underwent measurements of best-correct visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular pressure, clinical examination by a fellowship trained retinal specialist and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan (Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) at every visit. BCVA measurements included Snellen visual acuity obtained with patients’ own corrective spectacles, additional pinhole testing, and/or manifest refraction whenever available. Patients were switched to faricimab due to either the ineffectiveness of prior anti-VEGF agents to achieve retinal dryness or inadequate treatment intervals. Retinal dryness was defined as the absence of any intraretinal or subretinal fluid on OCT of the macula, and the absence of hemorrhage on clinical examination. Inadequate treatment interval refers to injection intervals that were deemed too short – a joint decision by the physician and patient with the goal of achieving a longer and more sustainable treatment interval to lower patients’ burden of care. In our practice, we generally consider treatment intervals as “inadequate” if patients required a persistent 4–6 weekly injection interval for more than 3–6 months. If patients were switched to faricimab due to the inability to achieve retinal dryness, they were initially dosed at 4-week intervals until retinal dryness was achieved, after which the treatment intervals were extended by 2 to 4 weeks. For patients switched to faricimab due to inadequate treatment intervals, they commenced faricimab at the last treatment interval achieved with the previous anti-VEGF agent before extending.

The primary outcome measures included BCVA in ETDRS letter score and central subfield thickness (CST) measurement on OCT. Secondary outcome measures included the presence or absence of intraretinal fluid, subretinal fluid, intraretinal cysts and subretinal hyperreflective material on OCT, adverse events, and treatment history such as the mean number of injections and treatment intervals. Intraretinal cysts were identified as well-demarcated, round or oval hyporeflective spaces located within the retinal layers often accompanied with retinal thickening. Degenerative retinal cysts representing chronic retinal degeneration rather than active exudation are distinguished from intraretinal cysts by their location in the outer retina, tubular appearance, stability in size over time and lack of response to treatment were excluded from the definition of intraretinal cysts. Intraretinal fluid was defined as localized thickening or widening of the retinal architecture relative to a normal, healthy retina14. Snellen visual acuity was converted to the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) BCVA scoring via the formula: ETDRS letter score = 85 + 50 x log10 (Snellen fraction).

The study conformed to the guidelines (https://ethics.gri.nhg.com.sg/investigator-manual/) as prescribed by the institutional review board (National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board) and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent has been waived by National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board due to the retrospective nature of the study. The study protocols for data collection and HIPAA identifiers anonymization prior to analysis were in accordance with NHG Research Data Policy Version 2.0 dated 09 May 2023 and approved by Assistant Chief Medical Board (Research) at the institution.

OCT images were graded by trained graders using standardized grading protocols. CST was measured in the central (1 mm) subfield of the ETDRS grid using the proprietary Heidelberg viewer software. Graders screened each OCT B-scan for segmentation errors and manually adjusted these when errors were present. The presence of intraretinal fluid, subretinal fluid, intraretinal cysts and subretinal hyperreflective material was manually graded. While our study did not include formal grading of color fundus photography, fluorescein angiography (FA), or indocyanine green angiography (ICG), the OCT images were extensively reviewed in conjunction with electronic medical records. These records included detailed documentation of hemorrhages and other pertinent findings observed during clinical examinations.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-square tests were used to compare the proportions of various groups, and paired t-tests were used to compare means between variables, with a p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

One hundred and nineteen eyes of 117 patients with a mean age of 75.6 years (range 58–93 years) were switched to faricimab and included in the analysis. Of these, 62 (52.9%) were females. Of the 119 eyes, 69 eyes had type 1 macular neovascularisation (MNV), 7 eyes had type 2 MNV, none had type 3 MNV and 43 eyes had PCV. The mean number of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections received was 28.2 ± 19.5 prior to switching to faricimab. Amongst the switchers, 87 (73.1%) were switched from aflibercept, 31 (26.1%) were switched from ranibizumab and 1 (0.8%) was switched from bevacizumab. 106 (90.6%) were switched due to the ineffectiveness of prior anti-VEGF agents to achieve retinal dryness and 11 (9.4%) were switched due to inadequate treatment intervals. Of the 119 eyes that were switched to faricimab injections, 14 eyes received only a single faricimab injection with just one follow-up visit; the mean follow-up duration for this subgroup was 5.2 weeks (range 1 to 9 weeks).

Table 1 summarizes the demographics data included in the analysis.

Efficacy

At baseline, BCVA was 62.7 ± 19.9 letters and mean CST on OCT was 352.5 μm ± 128.5 μm. Eleven (9.4%) eyes were dry on OCT. Of those that had fluid on OCT, 47 (39.5%) had presence of intraretinal fluid, 86 (72.3%) had presence of subretinal fluid, 49 (41.2%) had presence of intraretinal cysts, and 60 (50.4%) had presence of subretinal hyperreflective material.

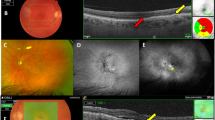

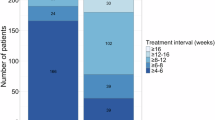

The mean follow-up period after switching to faricimab was 31.61 weeks (range 1 to 74 weeks). After switching to faricimab, the eyes received a mean of 4.8 ± 2.7 faricimab injections up to the time of data cut-off. The median number of injections received was 5 and the median injection interval was 6 weeks, compared to 7 weeks prior to switching. (Table 1) At last visit, mean BCVA was 60.3 ± 20.7 letters and mean CST was 310.9 ± 129.8 μm. (Table 1) This represented a mean BCVA change of −2.4 letters (p = 0.013) and mean CST reduction of −41.6 μm (p < 0.001). Forty-nine (41.2%) eyes were dry on OCT (p = 0.112). Of those that had fluid on OCT, 29 (24.4%) had presence of intraretinal fluid, 49 (41.2%) had presence of subretinal fluid, 35 (29.4%) had presence of intraretinal cysts, and 58 (48.7%) had presence of subretinal hyperreflective material (all p < 0.001). The reduction rates of fluid in the various retinal compartments on OCT is presented in Fig. 1. There was greater anatomical benefit observed switching from ranibizumab compared to switching from aflibercept. (Fig. 2)

A subgroup analysis of the study cohort of 105 eyes that received more than one Faricimab injection was also performed. Among the 105 eyes with more than one injection, the baseline mean BCVA was 62.9 ± 20.0 letters, and the last visit mean BCVA was 60.1 ± 20.9 letters, representing a mean change of −2.7 letters (p = 0.008). The baseline mean CST was 347.7 ± 121.7 μm, and the last visit mean CST was 305.5 ± 118.4 μm, representing a mean change of −42.2 μm (p < 0.001).

Safety

No cases of serious ocular adverse events such as infectious endophthalmitis, retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) tears, intraocular inflammation, vasculitis or occlusive vasculitis were reported in our series of eyes treated with intravitreal faricimab injections.

Discussion

Our study showed that switching patients with treatment resistant nAMD to faricimab demonstrated the ability to maintain vision while adding anatomical gains. At final visit, there was a mean BCVA change of −2.4 letters and mean CST reduction of −41.6 μm. The number of eyes with absence of fluid in the retina increased by 345% while the number of eyes with the presence of IRF, IR cysts, and SRF on OCT showed decreases ranging between 28.6 and 43.0%. Intraretinal cystic lesions observed on OCT may represent either active exudation or chronic retinal degenerations. In our study, we observed an overall reduction in both the numbers and sizes of intraretinal cysts following Faricimab injections, suggesting that the majority of the intraretinal cysts observed on OCT in this cohort likely represented cysts associated with active exudation rather than retinal degeneration. No new safety signal of faricimab usage were detected in this study. Our data demonstrates the additional efficacy afforded by switching to faricimab in our cohort of Asian patients with treatment-resistant nAMD.

Despite the effectiveness of anti-VEGF agents, a significant subset of patients with nAMD exhibit treatment resistance, characterized by persistent fluid and associated vision loss. These treatment resistant cases have always been a challenge for physicians. The 2-year results from the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatment Trials (CATT) showed that 51.5% of eyes treated with monthly ranibizumab and 67.4% with monthly bevacizumab had persistent fluid on OCT. Similarly, the VIEW-2 trial demonstrated that 19.7% of eyes receiving monthly aflibercept still had fluid on OCT after one year, highlighting a significant proportion of patients with suboptimal treatment outcomes15,16.

Treatment-resistant nAMD can arise from various pathophysiological factors. Alternative angiogenic pathways, such as those involving Ang-2, may drive disease progression despite VEGF inhibition, while chronic retinal inflammation promotes neovascularization through pro-inflammatory cytokines17. Genetic polymorphisms, particularly in complement and inflammatory pathway genes, may predispose some individuals to reduced anti-VEGF response, highlighting the need for personalized treatment strategies. Additionally, altered pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics can result in drug tolerance, where the therapeutic effects diminish over time and tachyphylaxis where there is a rapid decrease in response to repeated drug administration4,7. Fibrotic changes in the retina may also impede drug penetration and efficacy. These factors highlight the complexity of treatment resistance and the need for more comprehensive therapeutic approaches18.

The enhanced efficacy observed with faricimab is likely due to its increased drying effect, evident even after the first dose, in our patients refractory to previous treatments. In our study, the number of patients without fluid in the retina increased from 11 at baseline to 49 at the final visit. Additionally, the proportion of patients with intraretinal fluid, intraretinal cysts, and subretinal fluid declined between 28.6 and 43.0%. Similarly, real-world data from Ng et al. showed that 40% of patients achieved first-dose dryness, and nearly 75% experienced reductions in retinal fluid, despite prior extensive anti-VEGF treatment19. Faricimab is a bispecific antibody designed to simultaneously inhibit both VEGF-A and Ang-2. This dual mechanism of action is thought to address multiple pathways involved in the pathophysiology of nAMD. VEGF-A plays a crucial role in the formation of abnormal blood vessels and increased vascular permeability, leading to fluid accumulation in the retina. Ang-2 destabilizes blood vessels and promotes inflammation and leakage. The combined inhibition of VEGF-A and Ang-2 not only targets the primary pathway of angiogenesis and vascular permeability but also addresses secondary mechanisms involving vascular stability and inflammation. This comprehensive blockade can lead to improved drying effects and better management of retinal fluid even in patients who have become refractory to other treatments7. Furthermore, its higher 6 mg dose compared to other anti-VEGF agents (e.g., ranibizumab at 0.5 mg, aflibercept at 2 mg) may overcome tolerance to lower-dose treatments, providing a more sustained and comprehensive therapeutic effect.

Real-world observations of anti-VEGF injections often fall short of replicating the stellar results seen in clinical trials, largely due to differences in patient populations, adherence to treatment protocols, and real-world treatment regimens. Unlike tightly controlled clinical trials, real-world studies often reflect the diversity of clinical settings, including treatment-resistant cases, co-morbidities, and varying physician practices. These studies are invaluable for assessing the practical effectiveness and safety of anti-VEGF therapies across broader, more heterogeneous populations, providing insights that help refine treatment approaches, identify gaps in care, and inform future research to optimize patient outcomes.

The findings of our study closely align with those of other early real-world studies involving cohorts with treatment resistant disease. These studies highlight the anatomical efficacy but limited functional improvement of faricimab in patients with recalcitrant nAMD, despite prolonged treatment with various other single-target anti-VEGF therapies13. In the TRUCKEE study, patients switched from any anti-VEGF therapy (N = 337 eyes) demonstrated a modest, statistically non-significant mean BCVA increase of + 0.7 letters and a significant mean CST reduction of − 25.3 μm, while maintaining a similar treatment interval to their previous agent. These patients, characterized by high treatment needs with an average of 31.1 prior injections, had a mean treatment interval of 44.2 days before switching, which remained consistent at 43.5 days post-switching.

In comparison, our study showed a mean BCVA change of − 2.4 letters which was statistically non-significant, but a more substantial mean CST reduction of − 41.6 μm (p < 0.001). Patients in our cohort had a mean of 28.2 intravitreal anti-VEGF injections prior to switching to faricimab, with a median injection interval of 6 weeks, compared to 7 weeks before the switch. These findings underscore the utility of faricimab in addressing anatomical improvements in difficult-to-treat nAMD cases, particularly for patients with significant treatment histories, while emphasizing the need for further research into optimizing functional outcomes. Further exploring the limited functional improvement observed in treatment-resistant cases, this outcome likely reflects the chronic nature of the disease and the associated structural retinal alterations, damage and fibrosis in this patient population20. Unlike treatment-naive patients, these individuals are less likely to achieve functional gains in BCVA, making vision maintenance the primary treatment goal.

Faricimab has demonstrated a generally acceptable safety profile, with ocular adverse events consistent with those expected from intravitreal anti-VEGF treatments7,8. Most of the adverse events tend to be associated with intravitreal anti-VEGF injections in general but were not specific to faricimab19. In the TENAYA and LUCERNE trials, intraocular inflammation (IOI) rates were low (2.0% with faricimab vs. 1.2% with aflibercept), with most cases resolving by week 487. RPE tears were another rare complication reported, with an incidence of 1-1.36% of patients in these trials7,21. Notably, our study did not observe any serious ocular adverse events, including RPE tears, intraocular inflammation, occlusive vasculitis, or endophthalmitis.

These findings have significant real-world implications, especially for the Asian cohort. Faricimab’s ability to maintain or improve BCVA and reduce CST suggests it is a viable option for patients who have suboptimal responses to bevacizumab, ranibizumab, or aflibercept. This can potentially extend the therapeutic options for clinicians managing difficult-to-treat nAMD cases. The potential for extended treatment intervals with faricimab can reduce the burden of frequent injections, improving patient compliance and quality of life. This is particularly important in Asia, where logistical challenges and access to healthcare can impact treatment adherence. Switching to an agent such as Faricimab offers a potential avenue for treating persistent nAMD activity.

As this was a retrospective study, there are some inherent limitations such as potential selection bias and the lack of a randomized control group. BCVA measurements included Snellen visual acuity obtained with patients’ own corrective spectacles, additional pinhole testing, and/or manifest refraction whenever available, which may have introduced confounders in the analysis of BCVA changes. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, treatment protocol and follow-up intervals were not standardized, and injection intervals – including the definition of inadequate treatment intervals – were based on subjective criteria determined by the treating physician’s clinical judgement and best practices. Additionally, the study duration was insufficient to determine whether there was an increase in treatment intervals or a reduction in the number of injections required after switching to faricimab, despite the favorable anatomical outcomes described. As a result, there was an incongruous follow-up duration before and after the switch to Faricimab. Therefore, the comparison of the total number of injections before and after the switch was not standardized to a fixed time frame which limits a direct comparison of treatment intervals. Ideally, a follow-up period of at least six months for all patients would allow for a more accurate assessment of the peak therapeutic effects of Faricimab after sufficient loading as well as its longer-term anatomical and visual outcomes. Further research is needed to identify the optimal timing for patients to switch from monospecific anti-VEGF therapy to bispecific anti-VEGF/Ang2 therapy for maximum benefit. We did not perform an analysis on treatment outcomes based on individual subtypes of MNV as the sample size was too small to draw meaningful and reliable conclusions regarding any potential differences in treatment response between the various subtypes of nAMD and PCV eyes. In addition, the OCT images were not specifically evaluated for the presence or progression of GA. As the potential association between anti-VEGF therapy and GA progression is an adverse event that has been discussed in previous studies22, the absence of GA assessment represents a limitation of this analysis. Further research is needed to better understand the development and progression of GA in patients treated with Faricimab and to clarify its potential impact on long-term visual outcomes.

14 of the 119 eyes received only a single faricimab injection with one follow up visit, which may limit the ability to fully assess the drug’s therapeutic effect, as optimal outcomes typically require at least 3 to 4 injections to achieve the peak therapeutic effects of Faricimab. Therefore, we performed a sub-analysis of the study cohort comparing the outcomes of the 105 eyes that received more than one Faricimab injection with the overall cohort including the 14 eyes that received only a single injection. The findings from this sub-analysis suggest that inclusion of the 14 eyes in the overall analysis of the study cohort did not skew the results of this study in an erroneous direction.

Despite the limitations, we believe these data offer useful insights into real-world treatment patterns and may help inform clinicians about the potential impact of switching to faricimab in routine practice. Future studies with fixed follow-up intervals and larger cohorts are warranted to enable more accurate comparisons, and including diverse populations from different regions in Asia would help to validate these findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that switching patients with treatment-resistant nAMD patients to faricimab provides a viable and effective therapeutic option, particularly in a predominantly Asian cohort within a real-world setting. More specifically, it has shown that faricimab has the ability to maintain vision while adding anatomical gains in those previously resistant to alternative anti-VEGF therapy. Additionally, it has shown a favorable safety profile, with no serious ocular adverse events reported in our study.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the institutional (National Healthcare Group) data security policy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wong, W. L. et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2 (2), e106–e116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70145-1 (2014).

Flores, R. et al. Age-Related macular degeneration: pathophysiology, management, and future perspectives. Ophthalmologica 244 (6), 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517520 (2021).

Flaxel, C. J. et al. Age-Related macular degeneration preferred practice Pattern(R). Ophthalmology 127 (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.024 (2020). p. P1-P65.

Tan, C. S. et al. Neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration (nAMD): A review of emerging treatment options. Clin. Ophthalmol. 16, 917–933. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S231913 (2022).

Khan, M. et al. Targeting angiopoietin in retinal vascular diseases: A literature review and summary of clinical trials involving faricimab. Cells 9 (8). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9081869 (2020).

Khanani, A. M. et al. Efficacy of every four monthly and quarterly dosing of faricimab vs Ranibizumab in neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration: the STAIRWAY phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 138 (9), 964–972. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.2699 (2020).

Heier, J. S. et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of intravitreal faricimab up to every 16 weeks for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (TENAYA and LUCERNE): two randomised, double-masked, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet 399 (10326), 729–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00010-1 (2022).

Leung, E. H. et al. Initial Real-World experience with faricimab in Treatment-Resistant neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration. Clin. Ophthalmol. 17, 1287–1293. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S409822 (2023).

Stanga, P. E. et al. Faricimab in neovascular AMD: first report of real-world outcomes in an independent retina clinic. Eye (Lond). 37 (15), 3282–3289. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-023-02505-z (2023).

Kishi, M. et al. Short-Term outcomes of faricimab treatment in Aflibercept-Refractory eyes with neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration. J. Clin. Med. 12 (15). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12155145 (2023).

Hikichi, T. Investigation of satisfaction with short-term outcomes after switching to faricimab to treat neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 67 (6), 652–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10384-023-01024-4 (2023).

Inoda, S. et al. Visual and anatomical outcomes after initial intravitreal faricimab injection for neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration in patients with prior treatment history. Ophthalmol. Ther. 12 (5), 2703–2712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-023-00779-w (2023).

Khanani, A. M. et al. The real-world efficacy and safety of faricimab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: the TRUCKEE study – 6 month results. Eye (Lond). 37 (17), 3574–3581. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-023-02553-5 (2023).

Tan, C. S. et al. N, Predictors of persistent disease activity following anti-VEGF loading dose for nAMD patients in singapore: the DIALS study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020 Aug 6. 20(1): p. 324 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-020-01582-y

Heier, J. S. et al. Intravitreal Aflibercept (VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 119 (12), 2537–2548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.006 (2012).

Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials Research. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results. Ophthalmology 119 (7), 1388–1398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.053 (2012).

Sharma, D., Zachary, I. & Jia, H. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to Anti-VEGF therapy for neovascular eye diseases. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 64 (5), 28. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.64.5.28 (2023).

Yang, S., Zhao, J. & Sun, X. Resistance to anti-VEGF therapy in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a comprehensive review. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 10, 1857–1867. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S97653 (2016).

Ng, B. et al. Real-World data on faricimab switching in Treatment-Refractory neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration. Life (Basel). 14 (2). https://doi.org/10.3390/life14020193 (2024).

Pandit, S. A. et al. Clinical outcomes of faricimab in patients with previously treated neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol. Retina. 8 (4), 360–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oret.2023.10.018 (2024).

Ahn, J. et al. Retinal pigment epithelium tears after Anti-Vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration. Ophthalmologica 245 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000514991 (2022).

Eshtiaghi, A. et al. Geographic atrophy incidence and progression after intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents for age-related macular degeneration: A Meta-Analysis. Retina 41 (12), 2424–2435. https://doi.org/10.1097/iae.0000000000003207 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.N, K.L, N.W.K wrote the main manuscript.E.N, K.L, T.Z.H, A.T were involved in data collection.N.W.K prepared Figs. 1 and 2 and analyzed the data.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Wei Kiong Ngo has received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Bayer, Novartis, Roche and Zeiss. He has received lecture fees from AbbVie, Bayer, Novartis, Roche and Zeiss. He has received travel support from AbbVie, Roche and Zeiss. Louis Wei Yi Lim has received research grant from Novartis.All the remaining authors declare no conflict of interest. Open access fees for this publication were supported by an independent educational grant from Roche.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Neo, E., Liang, K.W.O., Toh, Z.H. et al. Real world outcomes of faricimab in treatment resistant neovascular age-related macular degeneration among Asian patients. Sci Rep 15, 33672 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18376-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18376-1