Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a prevalent metabolic disorder characterized by hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation. With limited therapeutic options available, there is growing interest in safe bioactive compounds that target underlying mechanisms. Aloesin, a chromone isolated from Aloe vera, possesses potent antioxidants and hypoglycemic properties; however, its protective effect against NAFLD has not been previously examined. This study investigated the hepatoprotective potential of aloesin in rats with high-fat diet (HFD)-induced NAFLD, focusing on the role of Nrf2 signaling. Adult male Wistar rats were divided into seven groups (n = 8/group): control, control + aloesin (200 mg/kg), HFD alone, HFD + aloesin (50, 100, or 200 mg/kg), and HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) + brusatol (0.2 mg/kg, i.p.). Treatments were administered twice weekly for 12 weeks. Aloesin dose-dependently improved metabolic and hepatic profiles, reducing body and liver weights, fasting glucose, insulin, HbA1c, HOMA-IR, and serum and hepatic levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, and LDL-c, with 200 mg/kg showing the greatest efficacy. It increased hepatic glucokinase and decreased G6Pase activity. Liver histology revealed restored architecture and reduced inflammation. Serum ALT, AST, and GGT were significantly lowered. Molecular analyses showed increased nuclear Nrf2 and antioxidant markers (GSH, SOD, HO-1), with suppressed NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6, Bax, and caspase-3, and upregulated Bcl-2. Aloesin also modulated lipid metabolism by decreasing SREBP1 and increasing PPARα expression. These effects were reversed by brusatol, confirming Nrf2 pathway involvement. In conclusion, aloesin confers potent Nrf2-mediated protection against NAFLD, with 200 mg/kg as the optimal therapeutic dose.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) stands as the most prevalent hepatic condition, characterized by the accumulation of excessive fat in liver cells stemming from factors other than alcohol consumption1. It encompasses a spectrum of liver abnormalities, spanning from simple steatosis (fatty liver) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer1. Additionally, NAFLD correlates with obesity, insulin resistance (IR), type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome2. Over recent decades, global rates of NAFLD have surged, reaching 25.7% in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by 2018 3.

The pathogenesis of NAFLD remains predominantly enigmatic, involving intricate interactions among peripheral and hepatic IR, dyslipidemia, oxidative stress, and inflammation4. Peripheral IR serves as a primary trigger in the development and progression of NAFLD. It facilitates lipolysis in white adipose tissue (WAT), elevating circulating levels of free fatty acids (FFAs) and their hepatic uptake5,6. Consequently, these FFAs undergo esterification, fostering dysregulated intrahepatic de novo lipogenesis, triglyceride (TG) accumulation, and lipotoxicity5. This lipotoxic milieu, accompanied by increased accumulation of lipid metabolites such as ceramides and diacylglycerols (DAG), augments reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and disrupts antioxidant systems, impairing mitochondrial function and escalating oxidative stress, hepatocellular injury, hepatic insulin resistance, and inflammation5,6,7. Expansion of WAT and co-existing peripheral IR further exacerbate hepatic inflammation and IR by amplifying the release and influx of inflammatory cytokines from adipose tissue to the liver5.

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) emerges as a principal master survival transcription factor, orchestrating antioxidant expression and cellular redox potential8. Nrf2 activities are chiefly regulated by cytoplasmic activation. Keap1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1), a cytoplasmic protein, binds to Nrf2, stimulating its proteasomal degradation under non-stressful conditions. ROS and electrophilic species modify Keap1, prompting Nrf2 nuclear translocation where it binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs), inducing the transcription of several antioxidants8. Nrf2 also modulates tissue-specific processes, suppressing inflammation, gluconeogenesis, lipogenesis, and apoptosis by regulating various cell receptors, cytoplasmic proteins, enzymes, and transcription factors9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Hyperglycemia is the prime culprit in impairing Nrf2 signaling in the liver during obesity and IR. Hyperglycemia can upregulate Keap1 directly or induce methylation of the ARE4 region, which typically binds to Nrf2 18,19,20. Furthermore, hyperglycemia enhances Nrf2 degradation via non-Keap1-dependent mechanisms, such as activating glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), which phosphorylates and degrades Nrf2 21. The role of Nrf2 in NAFLD pathogenesis is well-documented; Nrf2 deficiency in mice exacerbates hepatic steatosis and hepatocyte injury by enhancing oxidative stress, inflammation, lipogenesis, and apoptosis22,23,24. Conversely, livers of high-fat diet (HFD)-fed animals exhibit reduced Nrf2 transcription and activation, accompanied by increased Keap1 expression and Nrf2 degradation25,26,27. Nrf2 activators mitigate these pathological mechanisms, forestalling hepatic steatosis and NAFLD28,29,30emphasizing the importance of Nrf2 balance as a potential therapeutic target for NAFLD management.

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in isolating active compounds from plants for NAFLD treatment31. Numerous studies highlight the potential of Aloe vera (A. vera) in addressing metabolic disturbances and liver damage in chronic disorders such as diabetes mellitus and obesity. Daily consumption of A. vera extract lowers fasting plasma glucose and improves lipid profiles in pre-diabetic individuals32reduces body weight, hyperglycemia, and hypertriglyceridemia in HFD-diabetic rats33stimulates thermogenesis and browning of adipose tissue, enhances insulin release in HFD-fed mice34and attenuates hepatic steatosis and liver damage in HFD-fed rats by suppressing lipid peroxidation, inflammation, and apoptosis while increasing glutathione antioxidant levels35. Similar hypolipidemic and hepatic antioxidant effects of A. vera are observed in HFD and high fructose-fed rats36and it attenuates oxidative stress in the kidneys and livers of diabetic animals37,38. These beneficial effects are attributed to A. vera’s high content of active ingredients such as vitamins (e.g., B12, C, E, and A), hydrolysis and antioxidant enzymes (peroxidases, catalases, and amylases), sugars, fatty acids, saponins, and phenolic compounds (aloin, aloesin, aloe-emodin, emodin, etc.)39.

Aloesin, a prominent chromone isolated from A. vera gel, demonstrates robust antioxidant properties in vitro, surpassing other polyphenols from green tea and grape seed extract as well as vitamins C and E40,41. It exhibits potent ROS scavenging activity and suppresses inflammation by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2)41 and reduces systemic oxidative stress in diabetic animals and subjects41. Aloesin-rich extracts from A. vera inhibit lipid peroxidation40and a combination of A. vera inner leaf gel powder standardized to contain 2–4% aloesin, known as Loesyn or UP780, reduces fasting glucose, improves insulin clearance, increases adipokine secretion from adipose tissue, and reduces fatty liver deposition in HFD-fed animals42. Moreover, loesyn lowers blood glucose levels and HbA1C in diabetic animals and subjects43,44.

However, the individual therapeutic potential of aloesin against NAFLD remains largely uncharacterized, representing a critical gap in the current understanding of its pharmacological activity. Therefore, the present study was designed to evaluate whether chronic administration of Aloesin can mitigate hepatic steatosis and liver injury in a rat model of high-fat diet (HFD)-induced NAFLD. Furthermore, to elucidate the underlying mechanism, we employed brusatol, a well-established pharmacological inhibitor of Nrf2, to determine whether the metabolic and hepatoprotective effects of aloesin are mediated through activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway.

Materials and methods

Animal subjects

For this investigation, Wistar albino rats weighing 120 ± 15 g were sourced from and housed at the animal units of King Saud University, KSA. The rats were accommodated in standard laboratory cages with appropriate wood shavings and maintained under controlled temperature (20–22 °C) and humidity (40–60%). A 12-h light-dark cycle was maintained throughout the study period. Diet and water were provided ad libitum, and environmental enrichment items such as gnawing blocks, tunnels, and nesting materials were supplied to promote well-being and behavioral health. Daily monitoring by trained personnel ensured the rats’ welfare and timely reporting of any signs of distress, illness, or abnormal behavior.

Ethical statements

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Ethics Reference No: KSU-SE-23-20). Furthermore, the study followed the US National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication no. 85 − 23, revised 1996).

Accordance statement

The authors confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the full ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Dietary regimen

Two diets were used: a control diet (D12450B) and a high-fat diet (HFD, D12492), both sourced from Research Diets, Inc., New Jersey, USA. The control diet provided 3.85 kcal/g (16.1 kJ/g) of energy, comprising 10% fat, 70% carbohydrates, and 20% protein. The major constituents included casein, cellulose, sucrose, corn starch, and lard. The HFD, on the other hand, provided 5.24 kcal/g (21.9 kJ/g) of energy, comprising 60% fat, 20% protein, and 20% carbohydrate, with casein, cellulose, sucrose, and lard as the major ingredients.

Experimental design

Aloesin (S9284) obtained from Sigma Aldrich (USA) was freshly dissolved in 0.1% DMSO. One week after an acclimatization, a total of 56 adult male Wistar rats were randomly divided into seven groups (n = 8 per group) as follows: A total of 56 male Wistar rats were randomly divided into seven groups (n = 8 per group) as follows: (1) Control (standard diet + vehicle); (2) Control + aloesin (200 mg/kg); (3) HFD model (vehicle); (4) HFD + aloesin (50 mg/kg); (5) HFD + aloesin (100 mg/kg); (6) HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg); and (7) HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) + brusatol (0.2 mg/kg) (an Nrf2 inhibitor, 2 mg/kg). Brusatol (0.2 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally twice per week (i.p.; 2×/week), while aloesin was given orally twice weekly for a duration of 12 weeks. In the last group, brusatol was always administered to rats two hours before treatment with aloesin45,46 .

Regimen procedure and selection of doses

Previous experiments in our laboratory have established that 12 weeks of high-fat diet (HFD)- induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in Wistar rats is marked by peripheral insulin resistance (IR), hepatic oxidative stress and inflammation, alongside diminished Nrf2 activation and elevated NF-κB expression26In addition, we have previously used intraperitoneal bustaol administration (0.2 mg/kg; twice/peek) to block the activity of Nrf2 in the intestine and liver of HFD rats45,46 .

Euthanasia, blood and tissue collection

Upon completion of the study, following a 10-hour fasting period, the rats were anesthetized with an 80:10 (v/v) mixture of ketamine and xylazine hydrochloride. Blood samples were collected from the right ventricle for the isolation of serum and plasma. Subsequently, euthanasia was performed following ethical guidelines by neck dislocation, and livers were harvested, washed, and processed for further analysis. Tissue samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in formalin for subsequent biochemical and histological evaluations.

Biochemical analysis in serum and blood samples

Serum and plasma samples underwent biochemical analysis using ELISA kits tailored for rats. These kits, sourced from Cayman Chemicals, CA, USA (No. 589501 and 10009582), and Crystal Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL, USA (No. 80300), measured glucose, insulin, and HbA1C levels in blood plasma, respectively. The Homeostasis Model of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the formula: HOMA-IR = (fasting insulin [ng/mL] × fasting glucose [mg/dL])/405 47. Serum cholesterol (CHOL) level was determined using the ECCH-100 kit from BioAssay Systems, CA, USA. Additionally, ELISA kits from MyBioSource, CA, USA (MBS014345, MBS702165, MBS726298) were used to measure levels of free fatty acids (FFAs), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), and triglycerides (TG). Levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured using kits from MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA (MBS269614, MBS9343646), and Cosmo Bio, CA, USA (CSB-E13023r-1), respectively. All measurements were conducted twice for 8 samples per group, following the guidelines provided with each kit.

Hepatic lipid extraction and measurement

Lipids were extracted from frozen liver tissues following the protocol by Folch et al.48. Liver tissues (100 mg) were homogenized in a chloroform and methanol mixture (2:1 v/v), and the resulting homogenate was centrifuged to separate the lipid-containing chloroform layer. The lipid film obtained after solvent evaporation was dissolved in isopropanol. Measurements of FFAs, TGs, and CHOL were performed using the same kits employed for serum analysis. All parameters were analyzed for n = 8 samples per group, as per the suppliers’ instructions.

Analysis of liver homogenates

Total cell homogenates from liver tissues were prepared by homogenizing tissue samples (100 mg) in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. Supernatants obtained after centrifugation were stored at − 70 °C until use. Levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), malondialdehyde (MDA), total glutathione (GSH), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were measured using ELISA kits from Abcam, Cambridge, UK (ab100785), R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA, and AFG Scientific, IL, USA (EK720188, EK720816, EK720658, EK720889), respectively. Rat-specific ELISA kits were used to measure glucose-6-phosphatase (6-Pase) and glucokinase levels from MyBioSource, CA, USA (MBS097902, MBS453149). Kits from BioVision, CA, USA (E4513, LS-F11016, LS-F4135) were employed to measure Bax, Bcl-2, and caspase-3 levels, respectively. Analyses were conducted for each group with n = 8 samples, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Biochemical analysis in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions

Nuclear proteins were prepared using specific isolation kits (50,296) from Active Motif, CA, USA. ELISA kits from Abcam, Cambridge, UK (ab2072223, ab133112) were utilized to analyze nuclear extracts for the activities of Nrf2 and NF-κB, respectively. Each group consisted of eight samples, and all protocols were followed as instructed by the respective kit.

Real-time PCR in hepatic tissue

mRNA expression of Keap1, Nrf2, NF-κB, SREBP1, and PPARα was assessed by qPCR. All primers were designed by ThermoFisher and have been previously described in full in studies on rats26. After RNA extraction from frozen liver samples using TRIZOL reagent, cDNA was synthesized using K1621 cDNA synthesis kits from Thermo Fisher. Amplification reactions were performed using a CFX96 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad) and the SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix kit (172–5200, Bio-Rad). The expression of target genes was normalized to β-actin using the transcription levels of each target. Six samples were used in each group for amplification reactions.

Liver histology

Liver tissues were fixed in formalin, deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin under a light microscope to examine cellular architecture and tissue morphology49.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (Version 8). Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and a one-way ANOVA test was used for statistical analysis. Significance levels were evaluated with Tukey’s test as a post hoc procedure (p < 0.05). Means ± standard deviation (SD) were used to express all data.

Results

A non-Keap1-dependent mechanism stimulated the transactivation of Nrf2 activity in the livers of both control and HFD-fed rats upon Aloesin treatment

Compared to control rats, HFD-fed rats exhibited significantly elevated hepatic mRNA levels of Nrf2 and Keap1 (Fig. 1A, B). No significant alterations in the mRNA levels of Nrf2 or Keap1 were observed in the livers of control rats treated with aloesin (Fig. 1A). Similarly, there were no significant differences in the mRNA levels of Nrf2 and Keap1 between the HFD group and those treated with aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg). Conversely, the nuclear protein levels of Nrf2 significantly increased in the livers of control rats treated with aloesin (200 mg/kg) compared to control rats and in all HFD-fed groups receiving aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg) compared to the HFD model group (Fig. 1B). Notably, the increase in nuclear protein levels of Nrf2 in the livers of HFD + aloesin-treated rats exhibited a dose-response pattern, peaking in the group receiving the highest aloesin dose (200 mg/kg). Conversely, the nuclear protein levels in the livers of HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) + brusatol-treated rats were significantly lower compared to those in HFD + aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg) groups, though not significantly different from the levels in HFD model rats (Fig. 1B).

mRNA levels of Nrf2 and Keap1 (A) and nuclear protein levels of Nrf2 (B) in the liver of all groups of rats. Data were analyzed by Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s t-test as post hoc. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 8 rats/group. avs. control groups, bvs. control + aloesin, cvs. HFD, dvs. HFD + (50 mg/kg), evs. HFD + aloesin (100 mg/kg), and fvs. HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg).

Aloesin mitigated body weight gain, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance (IR) in a dose and Nrf2-dependent manner without affecting food intake

In HFD-fed rats, there was a notable increase in final body and liver weights, as well as in food intake. These rats also demonstrated elevated fasting glucose, insulin, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR levels, accompanied by increased hepatic G6Pase enzyme activity, which promotes gluconeogenesis. Additionally, HFD-fed rat livers displayed decreased levels of glucokinase, a key glycolysis enzyme (Table 1). Treatment with the highest aloesin dose (200 mg/kg) did not alter final body and liver weights or food intake in control rats, but significantly reduced fasting glucose, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR levels (Table 1). Conversely, a dose-dependent decline in body and liver weights, as well as fasting glucose, insulin, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR levels, was observed in HFD rats with an increase in aloesin dose. The most significant changes were observed at the highest dose, where markers were not significantly different from control levels (Table 1). Notably, there were no significant differences in food intake between the HFD model groups and those receiving aloesin. Moreover, aloesin treatment (200 mg/kg) in control rats significantly increased hepatic glucokinase levels and decreased G6Pase levels (Table 1). Similar dose-response reductions in G6Pase levels, accompanied by a dose-dependent increase in glucokinase levels, were observed in HFD rats treated with aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg). In contrast, final body and liver weights, fasting glucose, insulin, HbA1c, HOMA-IR, and hepatic G6Pase levels were significantly higher, while hepatic glucokinase levels were lower in HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) + brusatol-treated rats compared to HFD + aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg) treated rats. These markers did not significantly differ from those in the HFD model rats.

Aloesin attenuates hyperlipidemia in HFD-fed rats in a dose and Nrf2-dependent mechanism

Total fat weights, as well as serum, hepatic, and stool levels of TGs and CHOL, were significantly higher in HFD rats as compared to the control and control + aloesin-treated rats (Table 2). In addition, the serum of HFD rats showed higher levels of LDL-c and FFAs as compared to those of control rats. Stool levels were not significantly different when control rats were compared with control + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats or when HFD rats were compared to all other treated HFD rats (Table 2). Control rats fed aloesin (200 mg/kg) showed significantly lower serum and hepatic levels of TGs and CHOL, and their serum showed significantly lower levels of LDL-c than control rats (Table 2). In addition, all aloesin HFD-treated rats (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg) showed significantly lower fat weights, serum TGs, CHOL, LDL-c, and FFAs, and hepatic TGs and CHOL as compared to HFD model rats. The reduction in all these markers was progressive, and maximum reduction was seen in the HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats as compared to other treated groups. The reduction in all these biochemical ends was diminished in the HFD + alosein (200 mg/kg) + brustaol-treated rats. The serum and hepatic levels of all these lipids were not significantly different between the HFD rats and the levels of the HFD + alosein (200 mg/kg) + brustaol-treated rats.

Aloesin reduced liver damage and mitigated the increase in liver enzymes in HFD-fed rats in a dose and Nrf2-dependent manner

Control and control + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats showed normal liver histology, with intact hepatocyte cords, centrally located nuclei, and no evidence of lipid accumulation or inflammation (Fig. 2A,B). These groups also showed no significant differences in serum liver function markers—ALT, AST, and GGT—compared to untreated controls (Table 3). Conversely, HFD-fed rats exhibited extensive hepatic damage, including hepatocyte membrane disruption, ballooning degeneration, hepatocyte loss, and widespread cytoplasmic lipid vacuolization of varying sizes (Fig. 2C), alongside significantly elevated serum ALT, AST, and GGT levels (Table 3). Treatment with aloesin resulted in dose-dependent histological improvement. The HFD + aloesin (50 mg/kg) group showed mild-to-moderate reductions in hepatocellular vacuolation and inflammation (Fig. 2D), while the 100 mg/kg dose showed more substantial recovery of liver architecture (not shown). The 200 mg/kg aloesin-treated group exhibited near-complete preservation of normal hepatic morphology, minimal lipid accumulation, and markedly reduced inflammatory infiltration (Fig. 2E,F), with serum liver enzyme levels approaching those of control rats (Table 3). However, in the HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) + brusatol group, histological damage was re-established, with prominent hepatocellular vacuolization, distorted liver architecture, and inflammatory infiltration (Fig. 2G,H), accompanied by elevated liver enzyme levels (Table 3), confirming the role of Nrf2 in mediating aloesin’s protective effects.

Histological evaluation of the livers of all groups of rats as routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) at 200X. Images (A, B) were obtained from control and control + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats and showed normal features, including a contract central vein in which normally rounded and intact hepatocytes are radiating (long arrow) with normal sinusoids (arrow heads). Image (C) was taken from a model rat that fed the HFD and showed several pathological features, including a large number of cytoplasmic vacuoles that cover almost the whole field (long black arrow) with an increased number of infiltrating immune cells (yellow arrow). In addition, the livers of this group of cells showed too many pyknotic cells (short black arrow) and hemorrhage in the central vein (arrow head). (D): was taken from HFD + aloesin (50 mg/kg)-fed rats and showed an obvious reduction in the number and size of cytoplasmic vacuoles in many hepatocytes (long black arrow). However, many pyknotic cells (short black arrow) and a large number of immune cells (yellow arrow) were still seen. Images (E, F) were obtained from the HFD + aloesin (100 and 200 mg/kg)-treated cells, respectively, and show an obvious and gradual reduction in the number of hepatocytes with cytoplasmic vacuoles (long arrow) and an increased number of normal hepatocytes (short arrow). The majority of the cells appeared normal in the livers of HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg (image (E)); however, even though they are reduced in number, some immune cells are still seen in image (E), which represents the HFD + aloesin (100 mg/kg). Images (G, H) were taken from HFD and aloesin (200 mg/kg) + brusatol-treated rats and show almost similar features to those seen in the model HFD group (Image (C)), including a large number of hepatocytes with different sizes of cytoplasmic vacuoles (black arrow), pyknotic cells (arrowhead) and infiltrating immune cells (yellow arrow).

Aloesin suppressed lipid peroxidation and enhanced antioxidant enzymatic and non-enzymatic markers in HFD-fed rat livers in a dose and Nrf2-dependent mechanism

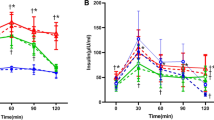

HFD-fed rat livers showed significantly higher levels of MDA (a marker of lipid peroxidation) and significantly lower levels of GSH, SOD, and HO-1 compared to control rats (Fig. 3A–D). Conversely, control + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats exhibited significantly lower MDA levels but higher GSH, SOD, and HO-1 levels compared to control rats, and HFD-fed rats treated with all aloesin doses showed similar changes compared to HFD model rats (Fig. 3A–D). Moreover, HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats exhibited higher MDA levels and reduced GSH, SOD, and HO-1 levels compared to rats treated with lower aloesin doses, though not statistically different from control rats (Fig. 3A–D). However, HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) + brusatol-treated rats showed higher MDA levels and decreased GSH, SOD, and HO-1 levels compared to HFD + aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg)-treated rats, and no significant differences from HFD model rats.

Hepatic levels of total reduced glutathione (GSH, A), superoxide dismutase (SOD, B), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1, C), and malondialdehyde (MDA, D) in the liver of all groups of rats. Data were analyzed by Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s t-test as post hoc. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 8 rats/group. avs. control groups, bvs. control + aloesin, cvs. HFD, dvs. HFD + (50 mg/kg), evs. HFD + aloesin (100 mg/kg), and fvs. HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg).

Aloesin attenuated the upregulation and activation of NF-κB and suppressed the increase in TNF-α and IL-6 in HFD-fed rat livers in a dose and Nrf2-dependent manner

HFD-fed rat livers showed significantly higher levels of IL-6 and TNF-α, as well as higher mRNA and nuclear levels of NF-κB compared to control rats (Fig. 4A–D). However, control + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats showed no significant differences in hepatic markers compared to control rats (Fig. 4A–D). Conversely, significant reductions in IL-6 and TNF-α levels, as well as mRNA and nuclear levels of NF-κB, were observed in HFD + aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg)-treated rats compared to HFD-fed rats (Fig. 4A–D). These reductions were most pronounced in HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats, with levels not significantly different from control rats. However, levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and NF-κB were significantly higher in HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) + brusatol-treated rats compared to HFD + aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg)-treated rats, with no significant differences from HFD model rats.

Hepatic levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α, A) and interleukin 6 (IL-6), mRNA of NF-κB (C), and nuclear levels of NF-κB (D) in the liver of all groups of rats. Data were analyzed by Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s t-test as post hoc. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 8 rats/group. avs. control groups, bvs. control + aloesin, cvs. HFD, dvs. HFD + (50 mg/kg), evs. HFD + aloesin (100 mg/kg), and fvs. HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg).

Aloesin alleviated apoptotic markers and increased Bcl2 anti-apoptotic protein levels in HFD-fed rat livers by stimulating Nrf2

Control + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats exhibited significantly higher Bcl2 levels and no significant differences in Bax and caspase-3 levels compared to control rats (Fig. 5A–C). Additionally, the Bax/Bcl2 ratio was significantly lower in control + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats compared to control rats (Fig. 5D). Conversely, HFD-fed rat livers showed significantly lower Bcl2 levels and higher Bax and caspase-3 levels, along with an increased Bax/Bcl2 ratio compared to control rats (Fig. 5A–D). These markers were significantly reversed in HFD + aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg)-treated rats compared to HFD-fed rats, with the most significant changes observed with the highest aloesin dose. However, these markers did not significantly differ between control and HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) treated rats. Interestingly, levels of apoptotic markers were not significantly different between HFD-fed rats and HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) treated rats.

Hepatic levels of caspase-3 (A), Bcl2 (B), and Bax (C), as well as the ratio of bax/Bcl2 (D) in the liver of all groups of rats. Data were analyzed by Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s t-test as post hoc. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 8 rats/group. avs. control groups, bvs. control + aloesin, cvs. HFD, dvs. HFD + (50 mg/kg), evs. HFD + aloesin (100 mg/kg), and fvs. HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg).

Aloesin regulated the activities of SREBP1 and PPARα by activating Nrf2

HFD-fed rat livers showed significantly increased mRNA levels of SREBP1 and significantly lower levels of PPARα compared to control rats (Fig. 6A, B). However, control + aloesin (200 mg/kg) and HFD + aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg)-treated rat livers showed significantly reduced SREBP1 levels and increased PPARα levels compared to control or HFD rats, respectively (Fig. 6A, B). These changes showed dose-responses, with the most significant alterations observed in HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg)-treated rats compared to HFD + aloesin (50 and 100 mg/kg). Conversely, mRNA levels of PPARα were significantly reduced, but SREBP1 levels were significantly increased in HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) + brusatol-treated rats compared to HFD + aloesin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg) treated rats. Additionally, hepatic mRNA levels of these factors did not significantly differ between HFD model rats and HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg) + brusatol-treated rats.

Hepatic mRNA levels of SREBP1 (A) and PPARα (B) in the liver of all groups of rats. Data were analyzed by Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s t-test as post hoc. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 8 rats/group. avs. control groups, bvs. control + aloesin, cvs. HFD, dvs. HFD + (50 mg/kg), evs. HFD + aloesin (100 mg/kg), and fvs. HFD + aloesin (200 mg/kg).

Discussion

In this study, aloesin emerges as a promising therapeutic agent for combating obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in rats, demonstrating efficacy in a dose-dependent manner. Particularly, the highest aloesin dose (200 mg/kg) not only inhibited fat accumulation and body weight gain but also prevented the progression of hepatic steatosis and injury induced by a high-fat diet (HFD). This protective effect was achieved through various mechanisms, including mitigation of lipid peroxidation, enhancement of antioxidant levels, reduction of inflammation and apoptosis, and improvement of metabolic parameters such as adiposity, insulin resistance (IR), hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia. Additionally, aloesin exerted regulatory control over key transcription factors involved in lipogenesis, oxidative stress, and inflammation, including SREBP1, PPARα, NF-κB, and Nrf2. Notably, the observed effects of aloesin were independent of food intake or final body weights. Moreover, inhibition of Nrf2 by brusatol reversed the beneficial effects of aloesin, highlighting the critical role of Nrf2 in mediating its therapeutic effects.

The expansion of adipocyte size and number, known as adiposity, is a central mechanism contributing to the onset of metabolic syndrome and NAFLD by exacerbating insulin resistance (IR) in white adipose tissue (WAT) and muscles50. Among the various models used to induce obesity, IR, and NAFLD in rodents, HFD stands out for its efficacy in stimulating calorie intake, adipogenesis, inflammation, and oxidative stress51. Multiple studies have underscored the anti-obesity and anti-adipogenic properties of several A. vera species, with researchers proposing diverse mechanisms of action, including modulation of gut microbiota composition, suppression of appetite, activation of thermogenesis-related genes, inhibition of pre-adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis, and reduction of intestinal fat absorption 34,52,53. Advanced fractionation studies have identified numerous bioactive compounds in A. vera with anti-diabetic and anti-obesity effects, such as anthocyanidins (e.g., cyanidin, peonidin, malvidin), flavones (e.g., apigenin and luteolin), flavonols (e.g., quercetin, gallic acid, kaempferol, and fisetin), flavanones (e.g., hesperetin), isoflavones (e.g., genistein and daidzein), and phytosterols (e.g., lophenol and cycloartenol), which exert their anti-obesity effects by modulating adipogenesis and thermogenesis through various molecular targets54,55,56. Moreover42, demonstrated that the polysaccharide fraction of A. vera is particularly effective in reducing body weight by suppressing appetite.

The study conducted by Jung et al.57 validated the obesity model induced by chronic high-fat diet (HFD) feeding, evidenced by significant increases in final body weights, fat pad weight, and levels of fasting glucose, insulin, and HOMA-IR in rats. Notably, control rats administered aloesin showed no mortality or adverse effects, consistent with the safety profile demonstrated by Lynch et al.58 in both male and female rats at a dosage of up to 1000 mg/kg. Of particular interest was the significant reduction in body and fat weights observed in HFD-fed rats post-treatment with aloesin, without affecting food intake. Conversely, aloesin had no impact on food intake or body weight in control rats, indicating its effectiveness specifically in obesity. Insulin, known for its anabolic role in regulating lipid synthesis genes and transcription factors59was a focal point of investigation. Furthermore, it was discovered that the effect of aloesin is Nrf2-dependent. Treatment of HFD-fed rats with brusatol, an Nrf2 inhibitor, reversed the reduction in body and fat weights, elevating circulating levels of glucose, insulin, and free fatty acids (FFAs), as well as HOMA-IR levels. These findings align with existing data supporting the protective role of Nrf2 against HFD-induced obesity and adipogenesis. Studies have shown that deficiency or inactivation of Nrf2 leads to severe insulin resistance (IR) and metabolic syndrome in rodents60,61,62. Also, Pharmacological activators of Nrf2, such as imidazolide, oltipraz, parthenolide, and epigallocatechin 3-gallate, have demonstrated preventive effects against obesity and IR by stimulating Nrf2 signaling in adipose tissue, along with hypoglycemic and anti-hyperlipidemic effects in diabetic animals63,64,65,66. Mechanisms underlying the suppression of adipose tissue lipogenesis and IR by Nrf2 involve inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation, as well as stimulation of oxygen consumption, energy expenditure, and thermogenesis, as extensively reviewed by Li et al.17.

During obesity, hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia become dominant and true risk factors for the development of metabolic syndrome, NAFLD, and cardiovascular disorders67. Within this view, IR stimulates lipolysis in the adipose tissue and enhances the influx of FFAs to the liver, which promotes lipotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and endoplasmic reticulum68. All these factors contribute to stimulating lipogenesis, gluconeogenesis, and hepatocyte injury68. SREBP1 and PPARα are two major transcription factors that are predominately expressed in the liver to regulate lipid metabolism69,70. SREBP1 stimulates TGs synthesis while PPARα suppresses lipotoxicity by stimulating the mitochondrial β-oxidation and the carnitine-shuttle pathway69. In the liver of HFD rats with NAFLD, SREBP1 is abnormally upregulated while PPARα transcription is reduced71,72,73. This was attributed to the cumulative effect of several factors, such as hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, inflammation, and hepatic IR71,74,75,76. In addition, the ratio of SREBP1/PPARα is significantly high and is positively associated with the degree of IR and hepatic steatosis77. Therefore, suppressing SREBP1 or activating PPARα are major targets to treat and alleviate NAFLD78.

The hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of A. vera and its active ingredients were also documented at the experimental and clinical levels and included acting by several mechanisms53,78 7980, . A. vera total extract prevented hepatic steatosis and liver damage in alcoholic and NAFLD by suppressing SREBP1 and activating PPARα54,81,82,83. The phenols and saponin fractions of A. vera showed potent inhibitory effects on several enzymes of hepatic lipogenesis84. Also, aloenin and barbaloin anthrachinonic derivatives stimulated insulin secretion by preserving the pancreatic beta cell damage in STZ-treated rats85. In addition, an aloe-based composition, UP780, attenuated fasting hyperglycemia in diabetic mice by blood glucose-lowering activity44. Opposing this, the aloin hypoglycemic effect was shown to be mediated by stimulating glycolysis enzymes such as hexokinase and pyruvate dehydrogenase and altering gut microbiota86,87. Furthermore, the polyphenols and flavonoids-rich fraction of A. vera attenuated hepatic lipogenesis by reducing adipose tissue lipogenesis and IR, altering gut microbiota, and suppressing several lipogenic targets such as C/EBPα, SREBP-1 C, acetyl-CoA carboxylase, and fatty acid synthase53. Phytosterols, lophenol, and cycloartenol, isolated compounds, also inhibited hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia in Zucker diabetic mice by attenuating obesity and improving peripheral IR66,88. They also reduced fasting in Zucker diabetic fatty rats by suppressing the major gluconeogenic enzymes (G6Pase and PEPCK)54. These phytosterols were also able to stimulate FA oxidation by acting as PPARα ligands89.

In this investigation, we have observed that aloesin exerts an inhibitory effect on SREBP1 mRNA levels while concurrently upregulating PPARα transcription in the livers of both control and high-fat diet (HFD)-fed rats. These effects corresponded with decreased hepatic and circulating levels of triglycerides (TGs) and cholesterol (CHOL) and were reliant on Nrf2 activation. Notably, no alterations in TGs and CHOL levels were noted in rat stool samples following aloesin administration, suggesting that the hypolipidemic effects of aloesin may not involve modulation of intestinal absorption. However, it is noteworthy that these hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of aloesin appear to be secondary to its ability to attenuate obesity, adiposity, and peripheral insulin resistance, as previously discussed. Remarkably, the hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects, as well as the regulatory effects of aloesin on SREBP1 and PPARα, were also evident in the livers of control rats, where no changes in body weight or adiposity were observed with aloesin administration. This suggests a potential central action of aloesin on the liver to enhance Nrf2 activity, thereby suppressing gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis. This aligns with a previous microarray study in high-fat diet-fed mice, demonstrating that aloesin (Loesyn or UP780) modulated various pathways involved in liver lipid metabolism by enhancing insulin signaling in adipose tissue and muscle, along with GLUT-4 expression, ultimately leading to reduced hepatic lipid uptake and diminished expression of SREBP1 and fatty acid biosynthesis. Furthermore, our findings are unique in demonstrating that aloesin can regulate hepatic SREBP1 and PPARα through Nrf2 stimulation. Nrf2 has been reported to play a role in lipid synthesis and glucose release. Additionally, aloesin, via Nrf2 stimulation, inhibited hepatic gluconeogenesis and promoted glycolysis in rat livers, contributing to its apparent hypoglycemic effect. This is supported by previous research indicating that Nrf2 not only acts as an antioxidant stimulator but also enhances hepatic insulin signaling and reduces gluconeogenesis by suppressing key enzymes such as glucose-6-phosphatase (G6P) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Pepck). Moreover, Nrf2 activators have been shown to inhibit hepatic lipogenesis by decreasing expression and activation of liver X receptor-alpha (LXRα), SREBP1, fatty acid synthase (FAS), and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC1). Additionally, Nrf2 stimulates fatty acid uptake and oxidation by regulating CD36 expression and upregulating PPARα, carnitine palmitoyltransferase I/II (CPT I/II), and peroxisomal acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 (ACOX1), the initial enzyme in beta-oxidation. However, whether aloesin acts to suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis or intestinal glucose absorption was not investigated in this study, and further research is warranted.

However, hepatic inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis represent significant pathological mechanisms underlying the NAFLD progression90,91,92. Following the onset of insulin resistance (IR) during obesity, there is an escalation in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inflammatory cytokine production in the liver, resembling a “second hit” that promotes fibrosis, hepatocyte apoptosis, and hepatic IR93. Conversely, several studies have implicated ROS, stemming from endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial damage, and diminished antioxidant capacity, as primary instigators of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis during NAFLD and NASH progression7,93. Furthermore, impaired Nrf2 function has been identified as a key mechanism driving NAFLD progression to NASH by depleting antioxidants, enhancing NF-κB activity, increasing inflammatory cytokine production, and promoting apoptosis23,24. In this context, Nrf2 not only elevates endogenous antioxidants within cells but also inhibits NF-κB, which is typically upregulated in the livers of NAFLD animals, thus suppressing inflammatory cytokine and ROS generation94,95. Moreover, Nrf2 mitigates NAFLD-induced intrinsic cell apoptosis by upregulating the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 9, which binds to the pro-apoptotic Bax protein to inhibit mitochondrial cytochrome-c release and subsequent caspase activation in the livers of NAFLD animals95.

The primary novel finding of this study was to illustrate that aloesin serves as an activator of Nrf2, offering protection against NAFLD by mitigating oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. Treatment with aloesin not only elevated mRNA and nuclear levels of Nrf2 in both high-fat diets (HFD)-fed and control rats but also correlated with increased levels of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione (GSH), and Bcl2, alongside a concomitant reduction in nuclear levels of NF-κB. Additionally, there was a significant decrease in total cellular levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), interleukin-6 (IL-6), caspase-3, and Bax. These findings corroborate the involvement of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in NAFLD pathogenesis, supporting previous studies. Notably, HFD stimulation of keap1 expression, as reported by other authors, was observed. However, aloesin treatment did not significantly alter Keap1 transcription in the livers of treated groups, suggesting direct stimulation of Nrf2 expression and reduction of Nrf2-Keap1 interaction by aloesin. This may be attributed to aloesin’s hypoglycemic effect, as hyperglycemia is suggested as a major trigger inhibiting Nrf2 expression, degradation, nuclear translocation, and transcriptional activity. Intriguingly, brusatol treatment reversed the inhibitory effect of aloesin on NF-κB, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) while enhancing apoptotic markers, including Bax and caspase-3, and reducing Bcl2 levels in the livers of HFD + aloesin-treated rats. These results suggest that the anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of aloesin are secondary to its antioxidant activity and the upregulation of the Nrf2/antioxidant axis, confirming ROS as the upstream inducer of inflammation and apoptosis.

Several plant phytochemicals, including those derived from Aloe vera (A. vera), have been shown to prevent or treat liver disorders and NAFLD by activating the Nrf2/antioxidant pathways. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of A. vera have been extensively documented in the literature, with evidence indicating its ability to scavenge antioxidants, suppress NF-κB, and reduce inflammatory cytokine production. Chromones isolated from various A. vera species have exhibited potent antioxidants and anti-inflammatory potential comparable to vitamin C. Notably, the antioxidant activity of aloesin surpasses that of green tea, as reported by prior studies. Additionally, aloesin has been demonstrated to act as an inhibitor of tyrosinase activity, a free radical scavenger, and a stimulator of cyclin E-dependent kinase activity.

As observed from all these data, our findings demonstrated a clear dose–response relationship, where aloesin at 50 and 100 mg/kg provided partial improvements, while the 200 mg/kg dose resulted in near-complete restoration of hepatic architecture, significant reductions in serum transaminases (ALT, AST, GGT), and marked suppression of lipid accumulation and inflammation in liver tissue. These protective effects were observed both histologically and biochemically, as well as at the molecular level. The enhanced efficacy of the 200 mg/kg dose may be attributed to more robust activation of the Nrf2 pathway, as evidenced by greater nuclear Nrf2 levels and downstream antioxidant responses (e.g., elevated GSH, SOD, and HO-1), along with more potent suppression of NF-κB signaling, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and apoptotic mediators. Additionally, only the 200 mg/kg dose normalized SREBP1 and PPARα expression levels, suggesting that this higher dose exerts a more comprehensive regulatory effect on hepatic lipid metabolism.

Conclusions

Given the central role of Nrf2 in coordinating antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic responses, the ability of aloesin to activate this pathway, independent of Keap1 transcriptional regulation, positions it as a promising candidate for targeted therapeutic strategies. Further investigations employing advanced genetic and pharmacological tools are warranted to dissect the precise molecular interactions of aloesin within the Nrf2 regulatory network.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

References

Wungjiranirun, M., Wong, N., Jou, J. & Moylan, C. A. Updates in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Liver Disease. 22, 157–161 (2023).

Jennison, E. & Byrne, C. D. Recent advances in NAFLD: current areas of contention. Fac. Reviews. 12, 10 (2023).

Alswat, K. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease burden–Saudi Arabia and united Arab emirates, 2017–2030. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 24, 211–219 (2018).

Pouwels, S. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a review of pathophysiology, clinical management and effects of weight loss. BMC Endocr. Disorders. 22, 63 (2022).

Buzzetti, E., Pinzani, M. & Tsochatzis, E. A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 65, 1038–1048 (2016).

Ziolkowska, S., Binienda, A., Jabłkowski, M., Szemraj, J. & Czarny, P. The interplay between insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress, base excision repair and metabolic syndrome in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11128 (2021).

Delli Bovi, A. P. et al. Oxidative stress in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. An updated mini review. Front. Med. 8, 595371 (2021).

Bukke, V. N., Moola, A., Serviddio, G., Vendemiale, G. & Bellanti, F. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2-mediated signaling and metabolic associated fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 6909 (2022).

Niture, S. K. & Jaiswal, A. K. Nrf2 protein up-regulates antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 and prevents cellular apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 9873–9886 (2012).

Kitteringham, N. R. et al. Proteomic analysis of Nrf2 deficient Transgenic mice reveals cellular defence and lipid metabolism as primary Nrf2-dependent pathways in the liver. J. Proteom. 73, 1612–1631 (2010).

Huang, J., Tabbi-Anneni, I., Gunda, V. & Wang, L. Transcription factor Nrf2 regulates SHP and lipogenic gene expression in hepatic lipid metabolism. Am. J. Physiology-Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. 299, G1211–G1221 (2010).

Olagnier, D. et al. Nrf2, a PPARγ alternative pathway to promote CD36 expression on inflammatory macrophages: implication for malaria. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002254 (2011).

Tanaka, Y., Ikeda, T., Yamamoto, K., Ogawa, H. & Kamisako, T. Dysregulated expression of fatty acid oxidation enzymes and iron-regulatory genes in livers of Nrf2‐null mice. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 27, 1711–1717 (2012).

Ludtmann, M. H., Angelova, P. R., Zhang, Y. & Abramov, A. Y. Dinkova-Kostova, A. T. Nrf2 affects the efficiency of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Biochem. J. 457, 415–424 (2014).

Wang, X., Li, C., Xu, S., Ishfaq, M. & Zhang, X. NF-E2-related factor 2 deletion facilitates hepatic fatty acids metabolism disorder induced by high-fat diet via regulating related genes in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 94, 186–196 (2016).

Slocum, S. L. et al. Keap1/Nrf2 pathway activation leads to a repressed hepatic gluconeogenic and lipogenic program in mice on a high-fat diet. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 591, 57–65 (2016).

Li, L. et al. Is Nrf2-ARE a potential target in NAFLD mitigation? Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 13, 35–44 (2019).

Zhong, Q., Mishra, M. & Kowluru, R. A. Transcription factor Nrf2-mediated antioxidant defense system in the development of diabetic retinopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 3941–3948 (2013).

Mishra, M., Zhong, Q. & Kowluru, R. A. Epigenetic modifications of Nrf2-mediated glutamate–cysteine ligase: implications for the development of diabetic retinopathy and the metabolic memory phenomenon associated with its continued progression. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 75, 129–139 (2014).

Kowluru, R. A. & Mishra, M. Epigenetic regulation of redox signaling in diabetic retinopathy: role of Nrf2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 103, 155–164 (2017).

Miller, W. P. et al. The stress response protein REDD1 promotes diabetes-induced oxidative stress in the retina by Keap1-independent Nrf2 degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 7350–7361 (2020).

Sugimoto, H. et al. Deletion of nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 leads to rapid onset and progression of nutritional steatohepatitis in mice. Am. J. Physiology-Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. 298, G283–G294 (2010).

Ke, Z. et al. Tangeretin improves hepatic steatosis and oxidative stress through the Nrf2 pathway in high fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease mice. Food Funct. 13, 2782–2790 (2022).

Tang, W., Jiang, Y. F., Ponnusamy, M. & Diallo, M. Role of Nrf2 in chronic liver disease. World J. Gastroenterology: WJG. 20, 13079 (2014).

Al-Hussan, R., Albadr, N. A., Alshammari, G. M., Almasri, S. A. & Yahya, M. A. Phloretamide prevent hepatic and pancreatic damage in diabetic male rats by modulating Nrf2 and NF-κB. Nutrients 15, 1456 (2023).

Al Jadani, J. M. et al. Esculeogenin A, a glycan from tomato, alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats through hypolipidemic, antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory effects. Nutrients 15, 4755 (2023).

Farage, A. E. et al. Betulin prevents high fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by mitigating oxidative stress and upregulating Nrf2 and SIRT1 in rats. Life Sci. 322, 121688 (2023).

Mohs, A. et al. Hepatocyte-specific NRF2 activation controls fibrogenesis and carcinogenesis in steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 74, 638–648 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway exacerbates cholestatic liver injury. Commun. Biology. 7, 621 (2024).

Tian, C., Huang, R. & Xiang, M. SIRT1: Harnessing multiple pathways to hinder NAFLD. Pharmacol. Res. 203, 107155 (2024).

Simental-Mendía, L. E. et al. Beneficial effects of plant-derived natural products on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pharmacological Prop. Plant-Derived Nat. Prod. Implications Hum. Health, 257–272 (2021).

Alinejad-Mofrad, S., Foadoddini, M., Saadatjoo, S. A. & Shayesteh, M. Improvement of glucose and lipid profile status with Aloe Vera in pre-diabetic subjects: a randomized controlled-trial. J. Diabetes Metabolic Disorders. 14, 22 (2015).

Javaid, S. & Waheed, A. Hypoglycemic and hypotriglyceridemic effects of Aloe Vera whole leaf and sitagliptin in diabetic rats. International J. Pathology, 48–52 (2020).

Tada, A. et al. Investigating anti-obesity effects by oral administration of Aloe Vera gel extract (AVGE): possible involvement in activation of brown adipose tissue (BAT). J. Nutri. Sci. Vitaminol. 66, 176–184 (2020).

Klaikeaw, N., Wongphoom, J., Werawatganon, D., Chayanupatkul, M. & Siriviriyakul, P. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant effects of Aloe Vera in rats with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. World J. Hepatol. 12, 363 (2020).

Abubakar, A. M., Dibal, N. I., Attah, M. O. O. & Chiroma, S. M. Exploring the antioxidant effects of Aloe vera: potential role in controlling liver function and lipid profile in high fat and Fructose diet (HFFD) fed mice. Pharmacol. Research-Modern Chin. Med. 4, 100150 (2022).

Bolkent, S. et al. Effect of Aloe Vera (L.) burm. Fil. Leaf gel and pulp extracts on kidney in type-II diabetic rat models. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 42, 48–52 (2004).

Can, A. et al. Effect of Aloe Vera leaf gel and pulp extracts on the liver in type-II diabetic rat models. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 27, 694–698 (2004).

Sánchez, M., González-Burgos, E. & Iglesias, I. Gómez-Serranillos, M. P. Pharmacological update properties of Aloe Vera and its major active constituents. Molecules 25, 1324 (2020).

Añibarro-Ortega, M. et al. Extraction of Aloesin from Aloe Vera rind using alternative green solvents: process optimization and biological activity assessment. Biology 10, 951 (2021).

Yagi, A. et al. Antioxidant, free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory effects of Aloesin derivatives in Aloe Vera. Planta Med. 68, 957–960 (2002).

Yimam, M. et al. UP780, a chromone-enriched Aloe composition improves insulin sensitivity. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 11, 267–275 (2013).

Devaraj, S. et al. Effects of Aloe Vera supplementation in subjects with prediabetes/metabolic syndrome. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 11, 35–40 (2013).

Yimam, M. et al. Blood glucose Lowering activity of Aloe based composition, UP780, in Alloxan induced insulin dependent mouse diabetes model. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 6, 61 (2014).

Yahya, M. A. et al. Isoliquiritigenin attenuates high-fat diet-induced intestinal damage by suppressing inflammation and oxidative stress and through activating Nrf2. J. Funct. Foods. 92, 105058 (2022).

Alshareef, N. S., AlSedairy, S. A., Al-Harbi, L. N., Alshammari, G. M. & Yahya, M. A. Carthamus tinctorius l.(safflower) flower extract attenuates hepatic injury and steatosis in a rat model of type 2 diabetes mellitus via Nrf2-dependent hypoglycemic, antioxidant, and hypolipidemic effects. Antioxidants 13, 1098 (2024).

Roza, N. A., Possignolo, L. F., Palanch, A. C. & Gontijo, J. A. Effect of long-term high-fat diet intake on peripheral insulin sensibility, blood pressure, and renal function in female rats. Food Nutr. Res. 60, 28536 (2016).

Folch, J., Lees, M. & Stanley, G. S. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509 (1957).

Bancroft, J. D. & Gamble, M. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques (Elsevier health sciences, 2008).

Kalavalapalli, S. et al. Adipose tissue insulin resistance predicts the severity of liver fibrosis in patients with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 108, 1192–1201 (2023).

van der Heijden, R. A. et al. High-fat diet induced obesity primes inflammation in adipose tissue prior to liver in C57BL/6j mice. Aging (Albany NY). 7, 256 (2015).

Shin, E. et al. Dietary Aloe improves insulin sensitivity via the suppression of obesity-induced inflammation in obese mice. Immune Netw. 11, 59–67 (2011).

Fu, S. et al. Aloe vera-fermented beverage ameliorates obesity and gut dysbiosis in high-fat-diet mice. Foods 11, 3728 (2022).

Misawa, E. et al. Oral ingestion of Aloe Vera phytosterols alters hepatic gene expression profiles and ameliorates obesity-associated metabolic disorders in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 2799–2806 (2012).

Khalilpourfarshbafi, M., Gholami, K., Murugan, D. D. & Sattar, A. Abdullah, N. A. Differential effects of dietary flavonoids on adipogenesis. Eur. J. Nutr. 58, 5–25 (2019).

Yunusoglu, O., Türkmen, Ö., Berköz, M., Yıldırım, M. & Yalın S. In vitro anti-obesity effect of Aloe Vera extract through transcription factors and lipolysis-associated genes. Eastern J. Medicine 27 (2022).

Jung, J. H., Hwang, S. B., Park, H. J., Jin, G. R. & Lee, B. H. Antiobesity and antidiabetic effects of Portulaca oleracea powder intake in high-fat diet‐induced obese C57BL/6 mice. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 5587848 (2021). (2021).

Lynch, B., Simon, R. & Roberts, A. Subchronic toxicity evaluation of Aloesin. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 61, 161–171 (2011).

Cignarelli, A. et al. Insulin and insulin receptors in adipose tissue development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 759 (2019).

Xue, P. et al. Adipose deficiency of Nrf2 in ob/ob mice results in severe metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 62, 845–854 (2013).

Liu, Z. et al. Deletion of Nrf2 leads to hepatic insulin resistance via the activation of NF-κB in mice fed a high-fat diet. Mol. Med. Rep. 14, 1323–1331 (2016).

Gutiérrez-Cuevas, J. et al. The role of NRF2 in obesity-associated cardiovascular risk factors. Antioxidants 11, 235 (2022).

Shin, S. et al. Role of Nrf2 in prevention of high-fat diet-induced obesity by synthetic triterpenoid CDDO-imidazolide. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 620, 138–144 (2009).

Yu, Z. et al. Oltipraz upregulates the nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 [corrected](NRF2) antioxidant system and prevents insulin resistance and obesity induced by a high-fat diet in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetologia 54, 922–934 (2010).

Sampath, C., Rashid, M. R., Sang, S. & Ahmedna, M. Green tea Epigallocatechin 3-gallate alleviates hyperglycemia and reduces advanced glycation end products via nrf2 pathway in mice with high fat diet-induced obesity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 87, 73–81 (2017).

Kim, C. Y., Kang, B., Suh, H. J. & Choi, H. S. Parthenolide, a feverfew-derived phytochemical, ameliorates obesity and obesity-induced inflammatory responses via the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway. Pharmacol. Res. 145, 104259 (2019).

Cetin, E. G., Demir, N. & Sen, I. The relationship between insulin resistance and liver damage in non-alcoholic fatty liver patients. Med. Bull. Sisli Etfal Hosp. 54, 411 (2020).

Manco, M. Insulin resistance and NAFLD: a dangerous liaison beyond the genetics. Children 4, 74 (2017).

Wang, Y., Nakajima, T., Gonzalez, F. J. & Tanaka, N. PPARs as metabolic regulators in the liver: lessons from liver-specific PPAR-null mice. International journal of molecular sciences 21, (2020). (2061).

Li, N. et al. SREBP regulation of lipid metabolism in liver disease, and therapeutic strategies. Biomedicines 11, 3280 (2023).

Moslehi, A. & Hamidi-Zad, Z. Role of SREBPs in liver diseases: a mini-review. J. Clin. Translational Hepatol. 6, 332 (2018).

Badmus, O. O., Hillhouse, S. A., Anderson, C. D., Hinds Jr, T. D. & Stec, D. E. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): functional analysis of lipid metabolism pathways. Clin. Sci. 136, 1347–1366 (2022).

Pawlak, M., Lefebvre, P. & Staels, B. Molecular mechanism of PPARα action and its impact on lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 62, 720–733 (2015).

Zhou, C. et al. High glucose microenvironment accelerates tumor growth via SREBP1-autophagy axis in pancreatic cancer. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Res. 38, 302 (2019).

Kusnadi, A. et al. The cytokine TNF promotes transcription factor SREBP activity and binding to inflammatory genes to activate macrophages and limit tissue repair. Immunity 51, 241–257 (2019). e249.

Pettinelli, P. et al. Enhancement in liver SREBP-1c/PPAR-α ratio and steatosis in obese patients: correlations with insulin resistance and n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid depletion. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-molecular Basis Disease. 1792, 1080–1086 (2009).

Pan, J. et al. Natural PPARs agonists for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 151, 113127 (2022).

Pothuraju, R., Sharma, R. K., Onteru, S. K., Singh, S. & Hussain, S. A. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of Aloe Vera extract preparations: A review. Phytother. Res. 30, 200–207 (2016).

Rahoui, W. et al. Beneficial effects of Aloe Vera gel on lipid profile, lipase activities and oxidant/antioxidant status in obese rats. J. Funct. Foods. 48, 525–532 (2018).

Gao, Y., Kuok, K. I., Jin, Y. & Wang, R. Biomedical applications of Aloe Vera. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59, S244–S256 (2019).

Saito, M. et al. Aloe Vera gel extract attenuates ethanol-induced hepatic lipid accumulation by suppressing the expression of lipogenic genes in mice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 76, 2049–2054 (2012).

Nguyen, T. K., Phung, H. H., Choi, W. J. & Ahn, H. C. Network Pharmacology and molecular Docking study on the multi-target mechanisms of Aloe Vera for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis treatment. Plants 11, 3585 (2022).

Rajasekaran, S., Sivagnanam, K. & Subramanian, S. Antioxidant effect of Aloe Vera gel extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats. Pharmacol. Rep. 57, 90–96 (2005).

Beppu, H. et al. Antidiabetic effects of dietary administration of Aloe arborescens miller components on multiple low-dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes in mice: investigation on hypoglycemic action and systemic absorption dynamics of Aloe components. J. Ethnopharmacol. 103, 468–477 (2006).

Wolever, T. M., Campbell, J. E., Geleva, D. & Anderson, G. H. High-fiber cereal reduces postprandial insulin responses in hyperinsulinemic but not normoinsulinemic subjects. Diabetes Care. 27, 1281–1285 (2004).

Zhong, R. et al. Anti-diabetic effect of Aloin via JNK-IRS1/PI3K pathways and regulation of gut microbiota. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 11, 189–198 (2022).

Al-Sowayan, N. S. & AL-Sallali, R. M. The effect of Aloin in blood glucose and antioxidants in male albino rats with Streptozoticin-induced diabetic. J. King Saud University-Science. 35, 102589 (2023).

Tanaka, M. et al. Identification of five phytosterols from Aloe Vera gel as anti-diabetic compounds. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 29, 1418–1422 (2006).

Nomaguchi, K. et al. Aloe Vera phytosterols act as ligands for PPAR and improve the expression levels of PPAR target genes in the livers of mice with diet-induced obesity. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 5, e190–e201 (2011).

Kanda, T. et al. Apoptosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 24, 2661 (2018).

Smirne, C. et al. Oxidative stress in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Livers 2, 30–76 (2022).

Song, C., Long, X., He, J. & Huang, Y. Recent evaluation about inflammatory mechanisms in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1081334 (2023).

Ma, Y., Lee, G., Heo, S. Y. & Roh, Y. S. Oxidative stress is a key modulator in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Antioxidants 11, 91 (2021).

Wu, L. & Xie, Y. Effect of NF-κB on the pathogenic course of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue ban = J. Cent. South. Univ. Med. Sci. 42, 463–467 (2017).

Park, J. S., Rustamov, N. & Roh, Y. S. The roles of NFR2-regulated oxidative stress and mitochondrial quality control in chronic liver diseases. Antioxidants 12, (2023). (1928).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend thanks to the Ongoing Research Funding Project (ORF-2025-84), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.A., L.N.A. and G.M.A.; methodology, S.M.A., A.S. and M.A.Y.; investigation, M.A.Y.; resources, G.M.A.; writing—original draft, S.M.A. and M.A.Y.; writing—review and editing, G.M.A. and N.A.A; supervision, L.N.A. and N.A.A.; project administration, M.A.Y.; funding acquisition, G.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alamri, S.M., Al-Harbi, L.N., Alshammari, G.M. et al. Aloesin activates Nrf2 signaling to attenuate obesity-associated oxidative stress and hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet-fed rats. Sci Rep 15, 34888 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18477-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18477-x