Abstract

Understanding cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) dynamics is crucial in the fields of neurosurgery and physiology. The myodural bridge (MDB), a dense connective tissue structure connecting the suboccipital muscles to the cervical spinal dura mater, has recently emerged as a novel regulatory component of the CSF dynamic system. Recent studies have shed light on its potential role in modulating CSF circulation, emphasizing the need to further investigate the underlying mechanisms by which the MDB influences CSF dynamics. The obliquus capitis inferior muscle is one of the suboccipital muscles. The main aim is to investigate the temporal and spatial variations in CSF pressure during electrical stimulation of the obliquus capitis inferior muscles. Thirteen anesthetized healthy Beagles were used. The pressure catheters were surgically implanted to monitor the pressure at four distinct locations: the right lateral ventricle pressure (LVP), the right frontal pole pressure (FPP), the right occipital pole pressure (OPP), and the lumbar subarachnoid pressure (LSP) between the L1 and L2 vertebrae. CSF pressure was recorded by the BL-420 F biological data acquisition and analysis system. One needle-electrode was inserted into the obliquus capitis inferior muscle, and electrical stimulation was applied on side. This comprehensive approach allowed for a detailed assessment of CSF pressure dynamics in response to the stimulation. During electrical stimulation, the CSF pressure exhibited significant spatial variations, with notable increases observed in the first peak of LVP, FPP, and OPP compared to baseline levels. Additionally, the plateau values of FPP, OPP, and LSP were significantly elevated. The mean pressure in these regions exhibited a mild increase during electrical stimulation. A statistically significant rise was only observed in FPP. Simultaneous monitoring of cranial and spinal CSF pressures revealed temporal changes in the propagation of pressure waves within the brain and subarachnoid space. Specifically, the first peak of intracranial CSF pressure occurred earlier than that in the lumbar subarachnoid space. Within the cranial cavity, the first peak time of OPP was the earliest, whereas that of FPP was the latest. The suboccipital muscles influence the occipital cistern through the MDB, generating pressure waves that spread through the subarachnoid space and the ventricles and maintaining local high pressure at frontal region. Pressure waves in the CSF diffuse from the occipito-atlantal cistern to the cranial cavity and spinal canal, following stable spatiotemporal patterns. This diffusion depends on anatomical structures and the distance from the occipito-atlantal cistern. This mechanism is one of the ways the MDB complex drives CSF circulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) plays a crucial role in the central nervous system, providing neurotrophic support to neural tissues, facilitating metabolic waste removal, and offering biomechanical protection1,2,3. Studies have identified multiple factors that modulate CSF dynamics, including cardiopulmonary, vasomotor, musculoskeletal, and craniofacial mechanisms4. However, the relative contributions and intricate interactions of these factors within the CSF system remain least understood. Gaining deeper insights into CSF dynamics is essential for advancing neurosurgical and physiological knowledge.

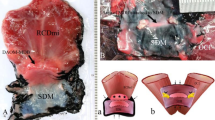

Recent breakthroughs have unveiled a novel regulatory component within the CSF system, known as the myodural bridge (MDB). This structure, recognized as an evolutionarily conserved feature, has been identified across a diverse range of vertebrates, including marine species, terrestrial mammals, reptiles, and birds, suggesting its status as a homologous organ5,6,7,8,9,10. Functioning as a fibrous link, the MDB connects the suboccipital muscles to the cervical spinal dura mater, traversing the posterior atlanto-occipital and atlantoaxial interspaces11,12,13. It originates from several important structures in the suboccipital region: the rectus capitis posterior minor muscle (RCPmi), the rectus capitis posterior major muscle (RCPma), the obliquus capitis inferior muscle (OCI), and the nuchal ligament14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

Currently, the role of the MDB in CSF circulation remains widely debated. Several studies suggest that interventions targeting the MDB can induce significant changes in CSF pressure within both the cranial cavity and spinal canal4,21,22,23. For instance, Xu et al. demonstrated that CSF pressure in the lumbar region markedly increased during head-nodding movements in humans21. Similarly, Young et al., in their study on Alligator mississippiensis, observed that twitching or training stimulation of the suboccipital muscles led to a reduction in CSF pressure4. Ma et al. reported a significant rise in spinal canal CSF pressure during electrical stimulation of the OCI in Beagles22. Additionally, Li et al. developed an experimental animal model by injecting ACE-031 into the suboccipital musculature of rats, which induced hyperplasia of these muscles and resulted in a notable increase in intracranial pressure. On contrary, physical removal of the MDB was associated with a significant decrease in intracranial pressure23. These findings collectively highlight the critical influence of the MDB and suboccipital musculature on CSF dynamics and intracranial pressure regulation.

However, the precise role of the MDB in the global regulation of CSF pressure remains poorly understood, despite its evident significance in influencing CSF flow dynamics. To address this gap, the current study investigates changes in CSF pressure at multiple anatomical locations before and during electrical stimulation of the OCI muscle in Beagles. By systematically monitoring these pressure variations, the study aims to provide deeper insights into the dynamic mechanisms through which the MDB modulates CSF circulation, offering valuable insights to its functional role in this complex physiological process.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. Animals were provided by Dalian Medical University, and experimental protocols involving animals were approved by the Ethics Committee of Dalian Medical University (Dalian, China, Ethics number: 2023-004). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental animals

A total of 13 healthy Beagle dogs (mean body weight: 14.59 ± 2.47 kg, 9 Males and 4 females) were sourced from the Laboratory Animal Center of Dalian Medical University. All dogs were fasted for approximately 12 h and hydrated for 4 h before the examination.

Surgical procedure

Anesthesia was induced by administering an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital at a dosage of 30 mg/kg. All surgical procedures were carried out with the animals positioned in the prone position.

Anesthesia was induced by administering an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital at a dosage of 30 mg/kg. All surgical procedures were carried out with the animals positioned in the prone position.

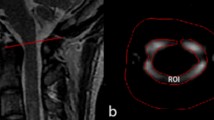

CSF pressure monitoring: A puncture needle was carefully inserted into the subarachnoid space between the L4 and L5 from the dorsal side. To minimize the influence of Beagle size and anatomical variations on CSF flow dynamics, a heparinized catheter was positioned in the subarachnoid space at the L1/L2 level. A midline skin incision of 4–5 cm was Made on the Head to expose the parietal bone. A burr-hole, approximately 8 mm in diameter and 10 mm lateral to midline, was created in the right parietal bone using a cranial drill. The burr-hole (insertion point) was 42 mm forward along the midline from the sagittal crest of the occipital bone (Fig. 1). A catheter was placed in the right lateral ventricle through the hole to a depth of 18 mm. Two additional catheters were placed in the subarachnoid space, one at the frontal pole (25 mm anterior to burr-hole) and one at the occipital pole (25 mm posterior to burr-hole). The burr-hole was then sealed with bone cement to ensure stability. The catheters were connected to a blood pressure sensor (PT-102, sensitivity: 100 Mv/mmHg, resolution: 0.006 mmHg). CSF pressure data were continuously recorded using the biological data acquisition and analysis system (BL-420 F, ChengDu Techman SoftWare Co., Ltd., China. URL link https://bioon.com.cn/product/show_product.asp? id=226902).

A burr-hole (indicated by blue circle) was carefully created in the right parietal bone, positioned 42 mm anterior to the sagittal crest of the occipital bone along the midline. A catheter was inserted in the right lateral ventricle through this burr-hole. Additionally, two more catheters were placed in the subarachnoid space: one at the frontal pole (25 mm anterior to the burr-hole, marked by a red star) and another at the occipital pole (25 mm posterior to the burr-hole, also marked by a red star).

Electrical stimulation of the OCI muscle: A midline skin incision measuring 10 to 12 cm was made on the neck to expose the OCI muscles. Electrical stimulation was delivered using the BL-420 F biological function laboratory system. One needle-electrode was inserted into middle region of the OCI muscle, and stimulation was applied on side a time with an output voltage of 10 V, a wavelength of 30 ms, and a frequency of 30 Hz. The stimulation was repeated three times on each side of the OCI muscle, with each session lasting 10 s. The right lateral ventricle pressure (LVP), the right frontal pole pressure (FPP), the right occipital pole pressure (OPP), and the lumbar subarachnoid pressure (LSP) were recorded during the electrical stimulation. The hydrostatic pressure used as the zero-reference point for CSF pressure measurements was defined as the level of the platform on which the Beagles were positioned in the prone position.

Blood pressure and heart rate were continuously monitored using a high-precision blood pressure sensor (PT-102). Respiratory activity was tracked using a bandage type respiratory sensor (HX200). All physiological signals were recorded in real-time via the BL-420 F data acquisition system. Following the completion of the experiment, the dogs were humanely euthanized by air embolism while under deep anesthesia.

Data collection and analysis

Quantitative analysis of CSF pressure was conducted in both the cranial cavity and lumbar subarachnoid space for all included subjects. Measurements were taken before and during electrical stimulation. Spatial parameters of CSF pressure were evaluated based on the first peak value, plateau phase value, and mean value (Fig. 2). Temporal parameters were assessed by measuring the first peak time and the effective duration of CSF pressure changes induced by electrical stimulation.

Data were recorded both before and during the electrical stimulation sessions. To account for potential muscle fatigue, the most pronounced change in CSF pressure observed across the three stimulation trials was selected for analysis. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 26.0). Continuous variables were analyzed using paired samples t-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), medians and quartiles, depending on the distribution. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparisons.

The figure provided a comprehensive representation of the spatial and temporal dynamics of CSF pressure changes during electrical stimulation on the OCI of the beagles. This model effectively captured the dynamic changes in CSF pressure, providing a detailed visualization of the response to electrical stimulation. Black arrow: the start of electrical stimulation; Blue arrow: the onset of increased CSF pressure; Green arrow: the first peak of CSF pressure; Yellow arrow: the last peak of CSF pressure; Red arrow: the end of the increased CSF pressure. Key measurements included as follows. First peak value: the initial pressure peak observed following electrical stimulation (value indicated by the green arrow); Plateau phase value: the average pressure value between the first and last pressure peaks (green to yellow arrow); Mean value: the average pressure value calculated from the onset to the conclusion of the increased CSF pressure (blue to red arrow); First peak time: The time interval from the start of electrical stimulation to the occurrence of the first pressure peak (the time that from black to blue arrow); Effective duration: the time span between the onset and termination of the increased CSF pressure (blue to red arrow). These measurements collectively described the dynamic changes in CSF pressure following electrical stimulation, including the initial response intensity, stable-phase pressure levels, overall pressure changes, response speed and the duration of pressure increase. The arrow indicators marked critical time points, facilitating the analysis and comparison of CSF pressure characteristics under different conditions.

Results

CSF pressure data were successfully collected from 13 beagles. No significant alterations in blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate were observed during the electrical stimulation (Table1)

A comparative analysis of blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate was conducted to evaluate potential physiological changes before and during electrical stimulation. No statistically significant differences were observed in these parameters, indicating that the electrical stimulation did not elicit notable systemic physiological responses. This suggested that the observed changes in CSF pressure were likely attributable to the localized effects of the stimulation rather than systemic alterations. BP, blood pressure.

Spatial variations of the CSF pressure

The CSF pressures across different regions during electrical stimulation of the OCI were illustrated in Fig. 3 and summarized in Table 1. Compared to baseline measurements, the first peak values of LVP (P = 0.049), FPP (P = 0.047) and OPP (P = 0.047) showed significant increases. Additionally, significant differences were observed in the plateau phase values of FPP (P = 0.003), OPP (P = 0.032) and LSP (P = 0.040). The mean pressure values in all four regions (LVP, FPP, OPP and LSP) increased during electrical stimulation; however, only the increase of FPP (P = 0.037) showed significant. These findings highlight the regional variations in CSF pressure dynamics in response to OCI stimulation.

The figure displayed CSF pressure traces recorded from the same Beagle specimen during electrical stimulation. The traces represent pressure variations in the following regions: the right lateral ventricle (black trace), the right frontal pole (blue trace), the right occipital pole (yellow trace), and the lumbar subarachnoid space (green trace). In addition to CSF pressure, blood pressure and respiration rate were simultaneously recorded. A notable rise in CSF pressure was observed in all monitored regions during electrical stimulation of the OCI. This figure illustrated the synchronized CSF pressure dynamics across multiple regions, providing insights into the systemic response to OCI stimulation. LVP, right lateral ventricle pressure; FPP, right frontal pole pressure; OPP, right occipital pole pressure; LSP, lumbar subarachnoid pressure; BP, blood pressure; R, respiration.

The table summarized the spatial variations in CSF pressure across four regions; LVP, FPP, OPP, and LSP during electrical stimulation. Key parameters include the first peak value, plateau phase value, and mean value of CSF pressure. LVP, right lateral ventricle pressure; FPP, right frontal pole pressure; OPP, right occipital pole pressure; LSP, lumbar subarachnoid pressure. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Temporal variations of the CSF pressure

Table 3 summarizes the temporal variations in CSF pressure across four regions during electrical stimulation of the OCI. The chronological order of the first peak time was as follows: OPP (0.28s), LVP (0.42s), FPP (0.50s), and LSP (0.64s). The first peak in intracranial CSF pressure occurred earlier than that in the lumbar subarachnoid space, suggesting a faster response within the cranial cavity and a delayed response in the LSP. Within the cranial cavity, OPP exhibited the earliest first peak time, while the FPP showed the latest. These results suggested that the earlier first peak time in intracranial regions (OPP, LVP, FPP) compared to LSP may reflect differences in the propagation of pressure waves or neural signaling pathways.

No significant differences were observed in the effective duration of electrical stimulation across all monitored regions, suggesting consistent temporal responses to stimulation despite regional variations in the timing of the first peak. This uniformity in effective duration indicates that electrical stimulation exerts a homogeneous influence on CSF pressure dynamics, even though localized differences in peak timing exist.

The table presented the temporal variations in CSF pressure during electrical stimulation, including the first peak time and effective duration for each region. The first peak time indicated the time from the onset of stimulation to the first pressure peak, while the effective duration represented the time span of increased CSF pressure. LVP, right lateral ventricle pressure; FPP, right frontal pole pressure; OPP, right occipital pole pressure; LSP, lumbar subarachnoid pressure.

Discussion

Spatial and Temporal response of CSF pressure during the electrical stimulation

As a novel regulatory component within the CSF system, previous studies have measured intracranial and spinal CSF pressure after interventions targeting the MDB. There is a lack of dynamic monitoring of spinal and intracranial multi-point CSF fluid pressure4,21,22,23. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to provide the evidence of CSF redistribution during electrical stimulation of the OCI. Our findings demonstrated significant changes in CSF pressure within both the cranial cavity and spinal subarachnoid space, including the lateral ventricle, frontal and occipital regions of the intracranial subarachnoid space, and the lumbar subarachnoid space at the L1/L2 level. These results highlight the dynamic and coordinated nature of CSF pressure regulations across multiple regions, offering new insights into the mechanisms underlying CSF dynamics during OCI stimulation.

The spatial characteristics of changes in CSF pressure showed a significant increase in the first peak values of CSF pressure of the lateral ventricle (LVP), frontal region (FPP) and occipital region (OPP), as well as the plateau phase values of CSF Pressure of the frontal region, occipital region and lumbar region (LSP). Additionally, the mean value of CSF Pressure of the frontal region showed a marked increase. The occipito-atlantal cistern (OAC) was previously described as an enlarged subarachnoid space at the occipito-cervical junction24. Functioning as a pivotal hub, the OAC serves as a primary site of action for the MDB, facilitating the flow of CSF from the cisterna magna to the surrounding subarachnoid spaces. Measurement sites within the cranial cavity, being closer to the OAC than the lumbar subarachnoid space, exhibiting more immediate pressure changes. Furthermore, the results of plateau phase analyses reflected the cumulative effects of electrical stimulation, while the unique anatomical location of the lateral ventricle and the dynamics of CSF production in it may explain its absence of a significant increase in the plateau phase values. The analyses of mean values illustrated the overall effects in CSF pressure during electrical stimulation, with a statistically significant increase observed only in the frontal region. These results indicate that the frontal region is the most responsive region in terms of spatial changes, with CSF pressure showing a sustained and significant increase throughout the entire stimulation period. So it would be suggested that regular head movements could create a persistent area with high pressure in the frontal region in the cranial cavity.

Regarding temporal characteristics, the first peak time in intracranial CSF pressure occurred earlier than in the lumbar spinal subarachnoid space. The first peak values represented immediate response elicited by electrical stimulation of the OCI (Fig. 4). Within the cranial cavity, the chronological order of the first peak time was the occipital region, lateral ventricle, frontal region, and lumbar region. These findings suggest that the timing of the first peak is closely related to the distance from the OAC. This pattern suggested that the transmission of CSF pressure induced by the MDB propagated in a wave-like manner. It would be demonstrated that the global CSF pressure changes across the cranial cavity and spinal canal in response to OCI stimulation, highlighting the dynamic and coordinated regulation of CSF pressure. This insight is crucial for understanding the physiological mechanisms of CSF pressure regulation and the impact of neural stimulation on CNS fluid dynamics.

The pattern of temporal variations of the first peak during the electrical stimulation. Compared to baseline measurements, CSF pressure increased significantly in all four monitored regions, with notable rise in the first peak values of the LVP, FPP and OPP. It demonstrated the redistribution of CSF within both the cranial cavity and spinal subarachnoid space. The chronological order of the first peak time was as follows: OPP (0.28s), LVP (0.42s), FPP (0.50s), and LSP (0.64s). This figure illustrated the wave-like propagation of CSF pressure changes, emphasizing the temporal and spatial redistribution of CSF during electrical stimulation. LVP, right lateral ventricle pressure; FPP, right frontal pole pressure; OPP, right occipital pole pressure; LSP, lumbar subarachnoid pressure; red asterisk, indicated the occipito-atlantal cistern (OAC), a key site for CSF dynamics.

The MDB provides a unique physiological mechanism for CSF circulation

The MDB is a fibrous structure that connects the suboccipital musculature to the cervical spinal dura mater11,12,13. Among the muscles involved in Head movements, the MDB connects the upper cervical spinal dura to three deep suboccipital muscles, including the RCPmi, the RCPma, and OCI. In 2014, we first proposed a functional hypothesis suggesting that the MDB might serve as a physiological driver for CSF circulation24.

Xu et al. investigated CSF flow dynamics at the craniocervical junction in healthy volunteers using cine phase-contrast MRI, comparing flow waveform parameters before and after one minute of head rotation and head nodding21,25. Their findings revealed that CSF flow rates at the level of the upper border of atlas during ventricular diastole significantly increased with head-rotation but decreased with head-nodding. Conversely, CSF pressure at the L3-L4 level was markedly increased with head-nodding. Head rotation exhibited a strong tendency to enhance CSF flow into the cranial cavity. Further supporting this mechanism, Ma et al. observed that electrical stimulation of the OCI in Beagles significantly increased CSF pressure in the lumbar subarachnoid space, without inducing significant cardiovascular or respiratory changes that could influence CSF pressure22. Based on these studies, we analyzed the global changes in CSF pressure resulting from MDB activation, uncovering a potential mechanism by which the MDB dynamically regulated CSF circulation. These findings collectively highlight the MDB’s role as a critical contributor to the physiological forces driving CSF dynamics. Previous studies on human, dogs, rats, and crocodiles have found that the muscular dura mater bridge has a dynamic effect on CSF circulation, however, the mechanism has not been thoroughly elucidated4,11,13,21,22,23,25. Based on these studies, we analyzed global CSF pressure changes following MDB activation, revealing a potential mechanism through which the MDB dynamically regulates CSF circulation. These findings highlight the MDB’s role as a key contributor to the physiological forces governing CSF dynamics.

In a recent study, the “OAC” was identified as an enlarged subarachnoid space, extending from the foramen magnum to the level of the C2 \26. The dorsal subarachnoid space at the occipito-cervical junction was believed to consist of two distinct components: the cisterna magna and the OAC. This expanded space, which accommodates a substantial volume of CSF, likely played a crucial role in maintaining the stability of CSF dynamics. Based on the present results, during head and neck movements, the MDB induces localized CSF pressure changes at the OAC, and these kinetic effects of the CSF propagate as pressure waves around the subarachnoid space in the cranial cavity and vertebral canal, and then facilitating CSF circulation. A significant portion of CSF from the ventricles flows into the cisterna magna and OAC, subsequently distributing to the subarachnoid spaces surrounding the brain and spinal cord through a dynamic mechanism. This highlights the MDB’s role in dynamically redistributing CSF to ensure efficient fluid movement within the central nervous system, offering new insights into the mechanisms underlying CSF dynamics during OCI stimulation.

In addition, there is a view that the veins and lymphatic plexus surrounding the frontal region served as important pathways for CSF outflow. Smyth et al., demonstrated that after injecting tracers into the OAC, the tracers accumulated around the transverse sinuses and the junction of the rostral rhinal vein with the superior sagittal sinus, eventually appearing in the cervical lymph nodes27. Similarly, Yoon et al. identified the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus as a critical region for CSF outflow in mice using fluorescent CSF tracers28. The olfactory turbinates contained an extensive lymphatic network that communicated with the subarachnoid space through specialized connections with the olfactory nerves29,30. In this study, electrical stimulation of OCI resulted in a significant and sustained increase of CSF pressure in the frontal region throughout the entire stimulation period. It may be attributed to a local high pressure at the frontal region as the anterior termination of the cranial cavity, where CSF pressure tends to accumulate and oscillate. So we hypothesize that the MDB-induced increase in the frontal region may enhance CSF outflow into the cervical lymphatic system. Pathological alterations in the MDB could potentially contribute to a range of neurological disorders through this mechanism, highlighting the MDB’s role in maintaining CSF dynamics and its broader implications for neurological health31,32. This study investigated the relationship between pressure waves, spatial parameters, and viscosity in driving fluid dynamics, proposing that temporospatial variations in pressure-induced differentials may influence cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation. The findings highlight the need for comprehensive experimental investigations to elucidate the multifactorial mechanisms governing this process and to validate the functional efficacy of CSF movement.

Several important limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the relatively small sample size may affect the external validity and generalizability of the results. Second, all experiments were performed in the prone position, which may not accurately represent normal human physiological conditions. Third, the number of measurement points was constrained by surgical complexity and instrument limitations, potentially limiting the comprehensiveness of the data. In addition, this study only observed the contraction of the OCI during electrical stimulation, and it remains unclear whether electromyographic activity occurred in the surrounding muscles. Arterial pressure monitoring alone may not sufficiently reflect changes in thoracic venous pressure induced by electrical stimulation, although no systemic responses or significant alterations in physiological parameters (blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate) were observed. In future studies, we plan to incorporate electromyographic recordings and central venous pressure monitoring to enhance experimental accuracy. Finally, all measurements were conducted under barbiturate anesthesia, which may influence CSF secretion and flow, potentially leading to deviations from normal physiological conditions. These limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the findings and designing future research.

Conclusion

This study provides the first comprehensive analysis of the temporal and spatial characteristics of the dynamic effects of the MDB on CSF circulation. The influence of the MDB on CSF dynamics is closely associated with its distance from the OAC and its unique anatomical structure, which connects the suboccipital muscles to the dura mater. The CSF flow driven by the MDB propagates as pressure waves, with the frontal pole serving as a focal point for CSF pressure concentration. These findings provide a novel perspective on the mechanisms governing CSF dynamics, highlighting the MDB’s critical role in regulating fluid movement within the central nervous system.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Spector, R., Keep, R. F., Snodgrass, R., Smith, S., Johanson, C. & Q. R. & E. A balanced view of choroid plexus structure and function: focus on adult humans. Exp. Neurol. 267, 78–86 (2015).

Tumani, H., Huss, A. & Bachhuber, F. The cerebrospinal fluid and barriers - anatomic and physiologic considerations. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 146, 21–32 (2017).

Cheng, L. et al. Detection of Glioma-Related hotspot mutations through sequencing of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-Derived Circulating tumor DNA: A pilot study on CSF-Based liquid biopsy for primary spinal cord Astrocytoma. Neurospine 20, 701–708 (2023).

Young, B. A. et al. Variations in the cerebrospinal fluid dynamics of the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). Fluids Barriers CNS. 18, 11 (2021).

Zhang, J. H. et al. Connection of the posterior occipital muscle and dura mater of the Siamese crocodile. Anat. Rec (Hoboken). 299, 1402–1408 (2016).

Liu, P. et al. The myodural Bridge existing in the nephocaena phocaenoides. PLoS One. 12, e0173630 (2017).

Dou, Y. R. et al. Existence and features of the myodural Bridge in Gallus domesticus: indication of its important physiological function. Anat. Sci. Int. 94, 184–191 (2019).

Okoye, C. S., Zheng, N., Yu, S. B. & Sui, H. J. The myodural Bridge in the common rock pigeon (Columbia livia): morphology and possible physiological implications. J. Morphol. 279, 1524–1531 (2018).

Zheng, N. et al. The universal existence of myodural Bridge in mammals: an indication of a necessary function. Sci. Rep. 7, 8248 (2017).

Young, B. A. & Cramberg, M. J. Treadmill locomotion in the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) produces dynamic changes in intracranial cerebrospinal fluid pressure. Sci. Rep. 12, 11826 (2022).

Hack, G. D., Koritzer, R. T., Robinson, W. L., Hallgren, R. C. & Greenman, P. E. Anatomic relation between the rectus capitis posterior minor muscle and the dura mater. Spine 20(23), 2484–2485 (1995).

Zheng, N. et al. Orientation and property of fibers of the myodural Bridge in humans. Spine J. 18, 1081–1087 (2018).

Palomeque-Del-Cerro, L. et al. A systematic review of the Soft-Tissue connections between neck muscles and dura mater: the myodural Bridge. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 42, 49–54 (2017).

Dean, N. A. & Mitchell, B. S. Anatomic relation between the nuchal ligament (ligamentum nuchae) and the spinal dura mater in the craniocervical region. Clin. Anat. 15, 182–185 (2002).

Johnson, G. M., Zhang, M. & Jones, D. G. The fine connective tissue architecture of the human ligamentum Nuchae. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 25, 5–9 (2000).

Pontell, M. E., Scali, F., Enix, D. E., Battaglia, P. J. & Marshall, E. Histological examination of the human obliquus capitis inferior myodural Bridge. Ann. Anat. 195, 522–526 (2013).

Mitchell, B. S., Humphreys, B. K. & O’Sullivan, E. Attachments of the ligamentum Nuchae to cervical posterior spinal dura and the lateral part of the occipital bone. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 21, 145–148 (1998).

Nash, L., Nicholson, H., Lee, A. S. J., Johnson, G. M. & Zhang, M. Configuration of the connective tissue in the posterior atlanto-occipital interspace: a sheet plastination and confocal microscopy study. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 30, 1359–1366 (2005).

Humphreys, B. K., Kenin, S., Hubbard, B. B. & Cramer, G. D. Investigation of connective tissue attachments to the cervical spinal dura mater. Clin. Anat. 16, 152–159 (2003).

Zheng, N. et al. The myodural Bridge complex defined as a new functional structure. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 42, 143–153 (2020).

Xu, Q. et al. Head-nodding: a driving force for the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid. Sci. Rep. 11, 14233 (2021).

Ma, Y. et al. The morphology, biomechanics, and physiological function of the suboccipital myodural connections. Sci. Rep. 11, 8064 (2021).

Li, C. et al. The relationship between myodural bridges, hyperplasia of the suboccipital musculature, and intracranial pressure. PLoS One. 17, e0273193 (2022).

Zheng, N. et al. Definition of the to be named ligament and vertebrodural ligament and their possible effects on the circulation of CSF. PLoS One. 9, e103451 (2014).

Xu, Q. et al. Head movement, an important contributor to human cerebrospinal fluid circulation. Sci. Rep. 6, 31787 (2016).

Li, Y. F. et al. A valuable subarachnoid space named the occipito-atlantal cistern. Sci. Rep. 13, 12096 (2023).

Smyth, L. C. D. et al. Identification of direct connections between the dura and the brain. Nature 627, 165–173 (2024).

Yoon, J. H. et al. Nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus is a hub for cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Nature 625, 768–777 (2024).

Zakharov, A., Papaiconomou, C. & Johnston, M. Lymphatic vessels gain access to cerebrospinal fluid through unique association with olfactory nerves. Lymphat Res. Biol. 2, 139–146 (2004).

Maloveska, M. et al. Dynamics of Evans blue clearance from cerebrospinal fluid into meningeal lymphatic vessels and deep cervical lymph nodes. Neurol. Res. 40, 372–380 (2018).

He, Y. et al. Denervation of rectus capitis posterior minor as neglected factor in Chiari malformation type I revealed by double blinded prospective study. Sci. Rep. 15, 9197 (2025).

Pan, D. S. et al. A new concept and surgical approach for Chiari malformation type I based on the protection and strengthening of the myodural Bridge. Sci. Rep. 15, 9445 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Fatemeh Mehrabi of Anesthetist nurse/MBBS 2023 student at Dalian Medical University for language support.

Funding

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers: NSFC32100928 and NSFC32071184).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S.B.Y., H.J.S.; Formal analysis: H.C.C., Y.C.H.; Methodology: X.Y.Y., K.Q.Y., Y.M., J.W., D.M.H., J.Z.; Project administration: S.B.Y., D.Z.G.; Writing-original draft: X.Y.Y.; Writing – review & editing: X.Y.Y., K.Q.Y., M.A.A.S., S.B.Y., H.J.S. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Dalian Medical University (Ethics number: 2023-004).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary Material 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, XY., Yang, KQ., Ma, Y. et al. Temporal and spatial variations in CSF pressure are influenced by electrical stimulation of the OCI muscles in beagles. Sci Rep 15, 33560 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18555-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18555-0