Abstract

This work introduces a novel framework for analyzing wave propagation in hydro-semiconductors by simultaneously incorporating fractional-order heat conduction, temperature-dependent thermal conductivity, and rotational effects into a unified photo-thermoelastic model. Unlike previous studies that considered these effects separately, the present model couples nonlocal fractional heat transport with variable thermal conductivity in a rotating semiconductor medium. Analytical solutions are obtained using the normal mode method, and numerical results illustrate how fractional derivatives and temperature-dependent conductivity jointly reshape thermal, mechanical, and carrier wave behaviors compared to classical theories. The findings provide new physical insights into nonlocal, memory-driven, and anisotropic transport phenomena in advanced semiconductor systems, which are not captured by conventional thermoelasticity models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coupling of thermal, mechanical, and optical fields in semiconductor materials has garnered substantial attention due to its relevance in cutting-edge applications such as optoelectronic devices, nanotechnology, and energy-efficient systems. This interaction becomes particularly significant in hydro-semiconductors, materials that simultaneously exhibit hydrodynamic and semiconductor behaviors under combined thermal and mechanical influences. The present study focuses on a complex physical framework involving fractional-order heat conduction, variable thermal conductivity, and rotational effects within hydro-semiconductors, where thermal, acoustic, and optical waves propagate under multifaceted conditions. Despite the growing demand for precise thermal management and wave control in semiconductor-based technologies, the combined influence of these factors remains underexplored. Specifically, the integration of fractional heat conduction models and temperature-dependent thermal conductivity under rotational effects presents a novel approach, offering new insights into nonlocal, memory-dependent, and anisotropic wave behavior in such advanced materials.

Classical thermoelasticity theory, originally formulated by Duhamel and Neumann, establishes the fundamental principles governing the interaction between temperature fields and mechanical deformation in elastic media1. This theory has since evolved into generalized frameworks such as the Lord–Shulman (LS)2 and Green–Lindsay (GL)3 models, which address the infinite heat propagation speed limitation of Fourier’s law by incorporating thermal relaxation times. These generalized models allow for the simultaneous treatment of thermal and elastic wave propagation in materials subjected to dynamic thermal loads4,5,6. More recently, the scope of thermoelasticity has expanded through the introduction of nonlocal and fractional-order theories, enabling the modeling of nanoscale effects and memory-dependent behavior. These developments are especially pertinent to semiconductor materials, where localized thermal and mechanical phenomena govern device performance7,8,9,10.

The introduction of rotation further complicates the thermoelastic response of hydro-semiconductors. Rotational motion induces Coriolis and centrifugal forces, altering the dispersion and amplitude of propagating waves. This is particularly relevant in rotating semiconductor components such as gyroscopes and microsensors, where wave precision is essential11,12,13,14. In hydro-semiconductors, rotational effects also interact with the movement of charge carriers, resulting in anisotropic propagation and nonlinear dynamic responses. The synergy among rotational motion, fractional heat conduction, and spatially varying thermal conductivity creates a rich and challenging physical environment in which classical models often fall short15,16,17.

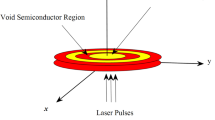

Semiconductors, known for their tunable electrical conductivity, form the foundation of modern electronic and photonic systems18. When exposed to optical and thermal stimuli, their behavior becomes more complex, necessitating the application of photo-thermoelasticity, a theory that accounts for the coupling of photon-induced thermal and elastic fields19,20. This framework is particularly valuable for describing the thermal–mechanical response of semiconductors under laser excitation and pulsed thermal loads21,22,23,24. The integration of photo-thermoelasticity with hydrodynamic modeling offers a powerful tool for examining the behavior of wave propagation under extreme and dynamic excitation conditions25,26.

Conventional Fourier-based heat conduction models assume an immediate response to thermal perturbations, which proves inadequate for materials exhibiting nonlocal or memory-driven thermal behavior27. Fractional-order heat conduction theories address this limitation by incorporating fractional derivatives, thereby enabling the characterization of sub-diffusive and super-diffusive heat transport. These models are particularly useful in capturing the heat conduction phenomena at nanoscales and under short-time excitations, such as those observed in advanced semiconductor devices28,29. When applied in conjunction with photo-thermoelasticity, fractional heat models enhance the understanding of thermomechanical wave propagation under non-equilibrium thermal conditions.

Hydro-semiconductors represent a specialized class of materials wherein the charge carriers (electron–hole plasma) behave as a compressible, viscous fluid, resulting in significant interactions between thermal, optical, and mechanical fields30,31,32,33. This fluid-like behavior introduces additional transport phenomena such as viscosity and inertia, which modify the wave propagation characteristics in ways that differ from conventional semiconductors34,35,36. These materials are of particular importance in high-frequency, high-power, and nanoscale applications, where traditional models fail to capture the intricate dynamics of coupled field behavior37,38,39. When combined with photo-thermoelasticity, hydrodynamic modeling enables a more comprehensive analysis of wave interaction in complex semiconducting environments40,41,42,43,44,45.

Furthermore, the assumption of constant thermal conductivity in classical models often does not hold for real-world applications. In many semiconducting materials, thermal conductivity varies with temperature, carrier concentration, and spatial gradients, significantly influencing heat and wave transport46,47. This variability leads to nonlinear thermal responses, wherein wave speed and attenuation depend on local thermal gradients. In hydro-semiconductors, the interplay between variable thermal conductivity and hydrodynamic charge transport amplifies the complexity of thermal, acoustic, and optical wave behavior48,49,50.

Recent advances in fractional-order thermoelasticity have demonstrated its effectiveness in capturing memory-dependent and nonlocal heat transport phenomena. Tiwari and Mukhopadhyay51 analyzed harmonic plane wave propagation under fractional heat conduction, providing a solid foundation for fractional thermoelastic wave studies, while Tiwari52 extended this framework to magneto-thermoelastic interactions with variable thermal and electrical conductivity, highlighting the importance of multiphysical couplings in realistic materials. In a related direction, Yu et al.53 employed nonlocal thermoelasticity to explain size-dependent damping mechanisms in nanostructures, thereby underlining the role of nonlocal effects in wave attenuation at small scales. Furthermore, Saeed et al.54 applied fractional calculus to fluid models, illustrating how local and nonlocal kernels can effectively describe ramped boundary conditions, which parallels the fractional modeling strategies employed in thermoelastic and semiconductor systems.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has systematically investigated the combined influence of fractional heat conduction, variable thermal conductivity, and rotational dynamics in hydro-semiconductor media. While fractional-order models capture memory-dependent heat transport and variable conductivity accounts for nonlinear thermal responses, their simultaneous interaction with rotation has not been addressed in the literature. This work fills that gap by presenting a comprehensive analytical and numerical study, offering new perspectives for wave propagation in rotating semiconductor systems. By incorporating photo-thermoelastic and hydrodynamic theories within a fractional framework, this work presents a novel and comprehensive approach to modeling wave propagation in rotating semiconductor systems. The findings offer valuable insights into the multi-physics interactions that govern advanced semiconductor behavior. Through graphical and comparative analyses, the influence of fractional parameters, thermal conductivity variation, and rotational effects is elucidated, paving the way for future innovations in the design of optoelectronic, thermoelectric, and micro-electromechanical devices.

Mathematical model and basic equations

The study employs a hydro-photo-thermoelasticity framework, which considers photo-generated carrier interactions, thermal expansion, and mechanical stress. The governing equations are derived based on the fundamentals of poro-thermoelasticity theory, with suitable modifications to integrate both rotational dynamics and variable thermal conductivity. This approach enables a comprehensive understanding of wave behavior in rotating hydro-semiconductors, highlighting the combined influence of thermal, optical, and mechanical fields. Rotation introduces Coriolis \(2\underline{\Omega } \,{\text{x }}\underline{{{\dot{\text{u}}}}}\) and centrifugal forces \(\underline{\Omega } \,{\text{x}}(\underline{\Omega } \,{\text{x}}\underline{u} )\), where \(\Omega\) represents the uniform angular velocity(\(\underline{\Omega } \, = \Omega \hat{n}\)) and \(\hat{n}\) is the unit vector aligned with the rotation axis. The system’s behavior is governed by the intricate interplay between thermal conduction, fluid motion, elastic deformations, and optical fields. Thermal conductivity effects, along with fractional heat conduction, are incorporated to account for scale-dependent responses and memory-driven thermal dynamics within the material. To obtain the main equations, we combine the laws of conservation of momentum, energy, and mass with constitutive relations for the fractional thermal behavior. This approach enables a comprehensive understanding of wave behavior in rotating hydro-semiconductors, highlighting the combined influence of thermal, optical, and mechanical fields.

-

i.

Charge Carrier Density \(N\) or plasma (Photo-thermal effects):

In semiconductor materials, the interaction of light with the medium generates photo-induced charge carriers, such as electrons and holes, leading to a change in the charge carrier density. This phenomenon, known as the photo-thermal effect, plays a significant role in the thermal and mechanical response of the medium due to the coupling between optical excitation, thermal conduction, and elastic deformations30,41,43.

$$\frac{\partial N}{{\partial t}} = D_{E} \nabla^{2} N - \,\frac{N}{\tau } + \kappa \;T.$$(1)Here \(\kappa\) is the thermal activation coupling coefficient.

-

ii.

Equation of Motion with Rotation.

The Equation of Motion with Rotation describes the dynamic behavior of a medium under the influence of rotational effects, where the inclusion of Coriolis and centrifugal forces modifies the motion of the system, leading to anisotropic wave propagation and altered mechanical responses36,44:

$$\begin{gathered} (\lambda + \mu )\nabla (\nabla \cdot \mathop{u}\limits^{\rightharpoonup} ) + \mu \nabla^{2} \mathop{u}\limits^{\rightharpoonup} - \nabla P - \gamma \nabla T - \delta_{n} \nabla N = \hfill \\ \,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,(\ddot{\underline {u} } + \underline{\Omega } \,{\text{x}}(\underline{\Omega } \,{\text{x}}\underline{u} ) + 2\underline{\Omega } \,{\text{x }}\underline{{{\dot{\text{u}}}}} ). \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$(2)where \(\varepsilon^{2} = \sqrt {ae_{0} /l}\) denotes the nonlocal parameter, \(l\) represents the external length scale, \(a\) expresses the internal length scale, and \(e_{0}\) is the non-dimensional material property coefficient.

-

iii.

The fractional heat equation.

The fractional heat equation generalizes the classical heat conduction model by incorporating fractional derivatives of order \(\alpha\)(\(\alpha\) represents the parameter of fractional), which account for memory effects, providing a more accurate description of thermal behavior in materials with variable thermal conductivity31,36,50:

$$\nabla .(K\nabla T) - (1 + \tau_{0}^{\alpha } \frac{{\partial^{\alpha } }}{{\partial t^{\alpha } }})\left( {m\frac{\partial T}{{\partial t}} - \gamma T_{o} \frac{\partial e}{{\partial t}}} \right) + \frac{{E_{g} }}{\tau }N = 0.$$(3)where \(\frac{{\partial^{\alpha } }}{{\partial t^{\alpha } }}\) expresses the \(\alpha\)-order fractional derivative (weak diffusion appears when \(0 < \alpha < 1\), \(\alpha = 1\) gives the strong diffusion, super-diffusion appears when, and ballistic diffusion is obtained when \(\alpha = 2\)) that can be applied to any function \(n(t)\), yields46:

$$\mathop {\lim }\limits_{\alpha \to 1} \frac{{d^{\alpha } }}{{dt^{\alpha } }}n(t) = n^{\prime}(t).$$(4) -

iv.

Fluid Flow Equation:

The fluid flow equation for a poro-semiconductor medium describes the movement of charge carriers as a fluid, considering the effects of porosity, pressure gradients, and interactions with thermal and mechanical fields, which are essential for analyzing coupled wave propagation38,39,40:

$$b_{w} (\alpha_{w} \frac{\partial T}{{\partial t}} - \frac{\partial e}{{\partial t}}) - \rho_{w} \frac{{\partial^{2} e}}{{\partial t^{2} }} + \nabla^{2} P = 0,$$(5)where \(m = n_{0} \rho_{w} C_{w} + (1 - n_{o} )\rho_{s} C_{s}\) and \(b_{w} = \frac{{g\rho_{w} }}{{k_{d} }}\).

-

v.

The constitutive relations are32,36:

$$\sigma_{iI} = \lambda u_{r,r} \delta_{iI} + \mu u_{I,i} + \mu u_{i,I} - (P + \gamma T - \delta_{nI} N)\delta_{iI} .$$(6)

In many semiconductor materials, the thermal conductivity is not constant but varies with temperature, carrier density, or other factors, influencing heat distribution within the medium. Variable thermal conductivity \(K(T)\) introduces additional complexity to thermal wave propagation, as the material’s ability to conduct heat becomes dependent on the local conditions, leading to non-linear temperature gradients and altering the wave behavior. The linear dependent temperature form of thermal conductivity with a small negative constant \(K_{1}\), is:

The Kirchhoff transformation is a mathematical technique used to simplify heat conduction problems, particularly when dealing with varying material properties such as temperature-dependent thermal conductivity. By transforming the temperature field into a new coordinate system, the Kirchhoff transformation linearizes the governing equations, making it easier to solve for temperature distributions and analyze thermal wave propagation in media with spatially varying thermal properties.

According to the linear form of thermal conductivity, it yields:

When the non-linear terms are ignored, Eq. (8) can be rewritten as:

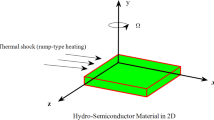

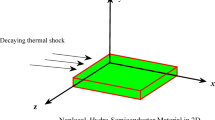

Studying the problem in a 2D hydro-semiconductor medium (in the xz-plane) involves analyzing the complex interactions between thermal, acoustic, and optical waves within a material subjected to various physical fields. In this context, the displacement field in 2D takes the form of a vector function \(\mathop{u}\limits^{\rightharpoonup} = (u,0,w)\;\;;\;u = u(x,z,t)\;\;,\;w = w(x,z,t),\,e = \frac{\partial u}{{\partial x}} + \frac{\partial w}{{\partial z}}\;\), which describes the deformation of the medium at any given point in space and time. This displacement field incorporates the effects of thermal expansion, mechanical stress, and photo-induced carrier generation, all of which contribute to the material’s overall dynamic behavior. The governing equations for such a system are derived from the principles of hydro-photo-thermoelasticity, considering the two-dimensional nature of the medium, and accounting for rotational, thermal, and mechanical influences. In this case the 2D main governing equations with variable thermal conductivity (Eqs. (7)–(10)) take the following form:

To simplify the governing equations that can be reduced into dimensionless form, we introduce dimensionless variables by scaling the original variables with respect to their characteristic scales. By applying these scaling transformations, the equations are simplified, making them more manageable and revealing the key parameters that govern the system’s behavior. This approach not only reduces the complexity of the problem but also allows for a clearer understanding of the dominant physical effects and their relative importance.

Using Eq. (15) and the transformation, yields46:

here

By using these scalar potentials \(\Pi (x,\,y,\,t)\) and \(\psi (x,\,y,\,t)\), the displacement components can be written as the gradient of the irrotational potential and the curl of the solenoidal potential, thus decoupling the system into more manageable equations. This formulation helps in reducing the complexity of the problem, especially in media where rotational effects and fluid–structure interactions play significant roles. Specifically, the displacement components can be expressed as47,48:

These relationships help decouple the system and make the analysis of wave propagation in such complex media more tractable. This approach greatly simplifies the equations of motion, especially when dealing with a rotational and poroelastic medium. In this case, the equations of motion (17) and (18) can be introduced in the following form:

Solution to the problem

The normal mode technique is a powerful analytical method used to solve complex wave propagation problems, particularly in systems with multiple coupled fields such as thermal, mechanical, and optical waves. In this approach, the solution is assumed to be a sum of harmonically oscillating functions, each corresponding to a specific frequency of oscillation. The normal mode technique simplifies the analysis of wave interactions in heterogeneous media, such as hydro-semiconductors, by allowing the separation of different wave components (e.g., thermal, acoustic, or optical) and their contributions to the overall response of the system31,38:

where \(\omega\) represents the frequency, \(b\) is the wave number for each mode, and \(N^{*} ,e^{*} ,\Pi^{*} ,\psi^{*} ,P^{*} ,\tilde{T}^{*}\) and \(\sigma_{ij}^{*}\) express the amplitude based on the axis \(x\). Substituting these expressions into the governing equations leads to a set of coupled equations for each mode as:

where \(\frac{d}{dx} = D\), \(\alpha_{1} = b^{2} + \varepsilon_{1} + \omega \,\varepsilon_{2}\), \(\alpha_{2} = b^{2} - \Omega^{2} - \omega^{2}\), \(\alpha_{3} = b^{2} + \omega (1\, + \tau_{0}^{\alpha } \omega^{\alpha } )\), \(\alpha_{4} = \varepsilon_{8} \omega (1\, + \tau_{0}^{\alpha } \omega^{\alpha } )\), \(\alpha_{5} = \omega (\varepsilon_{4} + \omega \varepsilon_{6} )\), \(\alpha_{6} = i\omega \varepsilon_{5}\), \(\alpha_{7} = 2\omega \Omega\), \(\alpha_{9} = 2B^{2} \Omega \omega\), \(\alpha_{8} = b^{2} - B^{2} (\omega^{2} \, - \Omega^{2} )\,\).

The elimination technique for \(N^{*} ,e^{*} ,\Pi^{*} ,\psi^{*} ,P^{*} ,\tilde{T}^{*}\) and \(\sigma_{ij}^{*}\) that helps to simplify complex coupled systems by reducing the number of variables:

Here

\(A_{1} = \alpha_{1} \alpha_{3} - \varepsilon_{3} \varepsilon_{7}\), \(A_{2} = \alpha_{5} + \alpha_{4} + \beta_{1} A_{5}\), \(A_{3} = \alpha_{7} \alpha_{9} \varepsilon^{2} (\varepsilon^{2} A_{5} + 2\beta_{2} )\), \(A_{4} = \beta_{1} (\alpha_{8} + \alpha_{2} \beta_{3} )\), \(A_{5} = \alpha_{1} + \alpha_{3}\), \(A_{6} = \alpha_{2} \alpha_{8}\), \(A_{11} = \beta_{3} A_{1} + A_{4} A_{5} + A_{6}\), \(A_{7} = \varepsilon^{2} (\varepsilon^{2} A_{1} + 2\beta_{2} A_{5} - \beta_{2}^{2} )\), \(A_{8} = \beta_{3} (b^{2} + \alpha_{1} ) + \alpha_{8}\)s, \(A_{9} = \beta_{1} \beta_{3} - \alpha_{7} \alpha_{9} \varepsilon^{4}\), \(A_{10} = \beta_{3} A_{5} + \alpha_{8}\), \(A_{16} = \beta_{3} \alpha_{1} + \alpha_{8}\), \(A_{12} = A_{1} (\alpha_{8} + \alpha_{2} \beta_{3} ) + \alpha_{2} \alpha_{8} A_{5}\). \(A_{13} = A_{5} \beta_{2}^{2} + 2\varepsilon^{2} A_{1} \beta_{2}\), \(A_{14} = \alpha_{1} b^{2} \beta_{3} + \alpha_{8} (\alpha_{1} + b^{2} )\), \(A_{15} = A_{1} \beta_{3} - \alpha_{8} A_{5}\), \(A_{17} = \beta_{3} b^{2} + \alpha_{8}\), \(A_{18} = \alpha_{8} (\alpha_{2} \beta_{1} + \alpha_{5} ) - \alpha_{7} \alpha_{9} \beta_{2}^{2}\).

To represent an ordinary differential equation (ODE), such as Eq. (32), in a factored form, the goal is to express it as a product of simpler terms, which can make it easier to solve or analyze. Here is a general approach to rewriting an ODE in a factored form:

\(k_{n}^{2} (n = 1,2,3,4)\)are the roots (chosen in positive and real) of the characteristic Eq. (39). The solution to the homogeneous Eq. (39) will take the form:

where

\(a_{n}^{*} = \frac{{ - \varepsilon_{3} }}{{k_{n}^{2} - \alpha_{1} }},\quad b_{n}^{*} = \frac{{k_{n}^{4} - (\alpha_{1} + \alpha_{3} )k_{n}^{2} + A_{1} }}{{\alpha_{4} (k_{n}^{2} - \alpha_{1} )(k_{n}^{2} - b^{2} )}},c_{n}^{*} = \frac{{\alpha_{9} (\varepsilon^{2} k_{n}^{2} - B_{2} )(k_{n}^{4} - (\alpha_{1} + \alpha_{3} )k_{n}^{2} + A_{1} )}}{{\alpha_{4} (k_{n}^{2} - \alpha_{1} )(B_{3} k_{n}^{2} - \alpha_{8} )(k_{n}^{2} - b^{2} )}}\), \(d_{n}^{*} = - \frac{{\alpha_{5} (k_{n}^{4} - (\alpha_{1} + \alpha_{3} )k_{n}^{2} + A_{1} ) + \alpha_{4} \alpha_{6} (k_{n}^{2} - \alpha_{1} )}}{{\alpha_{4} (k_{n}^{2} - \alpha_{1} )(k_{n}^{2} - b^{2} )}}\).

From the boundary conditions, \(M_{n}\) (are unknown coefficients) can be obtained. To express the 2D displacement components \(u\) and \(w\) in terms of a scalar potential \(\Pi\) and a vector potential \(\psi\), we use the following standard decomposition in the context of a fractional-rotational and poroelastic semiconductor medium:

Assuming that Eqs. (32) and (33) provide relationships between the strain and stress tensors, we can express the stress–strain relation in a reformulated form:

Boundary conditions

In the context of wave propagation problems, the decay parameter often refers to how the amplitude of a wave decays or diminishes with distance. For boundary conditions involving the decay parameter, especially in problems related to wave propagation in elastic, poroelastic, or hydroelastic media, these conditions typically specify how the waves behave at the boundaries, especially as they extend to infinity or approach a boundary where their effect diminishes. To obtain the values of \(M_{n}\), some boundary conditions at \(\,x = 0\) involving a decay parameter for a hydro-semiconductor are introduced42,43:

-

1.

If the system involves waves propagating outward in a semi-infinite domain, the thermal boundary condition can be expressed in terms of a decay parameter. If thermal effects are present, a similar decay condition can be applied to the temperature field.

$$\tilde{T}^{*} (0,z,t) = T_{0} \exp ( - \lambda t).$$(45)where \(\lambda\) the decay parameter is associated with the rate of thermal diffusion. The decay parameter plays an important role in defining the boundary conditions for wave propagation problems in media with rotational, poroelastic, and photothermal effects. By introducing a decay factor (exponential), these boundary conditions help model the dissipation of wave amplitude, stress, strain, or energy at the boundary, allowing for more realistic solutions that consider damping.

-

2.

In the context of hydroelastic media (e.g., in a hydro semiconductor medium or similar systems), the excess pore water pressure boundary condition is crucial for modeling the behavior of the fluid phase (e.g., water or another fluid) within the pores of the material. The excess pore pressure reflects the deviation of the pore pressure from its equilibrium value and can significantly affect wave propagation, especially in porous materials. If the boundary is impermeable, meaning there is no flow of fluid through the boundary, the excess pore pressure at the boundary is either constant \(P_{0}\)(is the prescribed excess pore pressure at the boundary):

$$P(0,z,t) = P_{0} .$$(46) -

3.

The carrier density boundary condition in a semiconductor or hydro-semiconductor medium governs the distribution of charge carriers (such as electrons or holes) at the material’s surface or interface. This is a crucial factor in many semiconductor physics problems, especially when photothermal or photoelastic effects are considered, and it can influence the propagation of waves within the material. For a system with waves propagating in the semiconductor, the carrier density may decay as it moves away from a source or the material’s boundary. This can happen, for instance, when the semiconductor is excited by a localized source, and the carrier density decreases with distance from the source. With equilibrium carrier concentration \(N_{0}\), this condition takes the form:

$$N^{*} (0,z,t) = N_{0} \exp ( - \lambda t).$$(47) -

4.

The boundary conditions for stress generally specify the mechanical behavior at the surface of the material or the interface with other materials (e.g., air). If the stress at the boundary is known and fixed (for example, from an external force or a uniform pressure applied on the surface), the boundary condition can specify the stress directly. This condition is common when a uniform load or pressure \(\varphi_{1}\) is applied to the material:

$$\sigma_{xx} (0,\,z,\,t) = \,\, - \varphi_{1} .$$(48)

It is noted that the boundary conditions (45)–(48) are expressed in terms of the nondimensional variables defined in Eqs. (15)–(22). By applying boundary conditions (45)–(48) and using normal mode analysis, the problem is reduced to a system of equations for the spatial components of the fields.

These equations can then be solved to obtain the mode shapes and dispersion relations for the system, which describe how the fields propagate and interact under the influence of external forces, rotational fields, and other material effects.

Validation

To assess the validity of the proposed model and its predictions related to wave propagation, thermal diffusion, and mechanical stress in hydro-semiconductors subjected to rotational effects, variable thermal conductivity and fractional-order derivatives, several key scenarios were considered.

The rotation effect

When the rotational angular parameter is disregarded (\(\Omega = 0\)), the study focuses on variable thermal conductivity and the behavior of a fractional hydro-semiconductor medium. In this case, the motion equation is simplified as outlined in44:

The variable thermal conductivity impacts

When the variable thermal conductivity is excluded (\(K_{1} = 0\) and \(K = K_{0}\)), the analysis is carried out for a fractional hydro-semiconductor medium with rotational effects. The resulting motion equations are derived as presented in41:

The fractional parameter

The heat equation is an extension of the classical form, incorporating fractional derivatives to capture scale-dependent and memory effects. When the fractional derivative of order \(\alpha\) is set to 1 (\(\alpha = 1\)), the heat equation reverts to its classical form as follows43:

The photo-thermoelasticity theories

When the thermal relaxation time effect is ignored (\(\tau_{o} = 0\)), the equations reduce to classical coupled thermoelasticity theory (CD)47. On the other hand, when \(\tau_{o} > 0\) is considered, the model predicts the Lord and Shulman (LS) model.

Numerical results and discussions

In this section, we present the numerical results and a thorough discussion of our study, which is based on the physical constants of poro-silicon (PSi) for performing the calculations. The computations are conducted using MATLAB to ensure precision in the modeling and analysis process. All parameters are expressed in SI units to maintain uniformity and standardization throughout the study. The following analysis provides a comprehensive review of the numerical solutions and their significance in the context of the poroelastic model. The physical constants specific to the PSi medium are listed in Table 149,50.

The influence of variable thermal conductivity

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of variable thermal conductivity \(K_{1}\) on the propagation of primary physical fields (temperature, horizontal and vertical displacements, carrier density, normal stress, and excess pore water pressure) against the distance \(x\) for a fractional heat order of \(\alpha = 0.5\), under the influence of rotational fields and the decay parameter \(\lambda = 0.3\). Three cases are presented: \(K_{1} = 0\)(constant thermal conductivity), \(K_{1} = - 0.03\), and \(K_{1} = - 0.06\)(temperature-dependent thermal conductivity). Temperature Field \(T\): The results show a sharp initial peak, followed by a gradual decay. With increasing thermal conductivity dependence (\(K_{1} = - 0.03\), and \(K_{1} = - 0.06\)), the temperature decreases more rapidly, indicating enhanced thermal diffusion due to the temperature-dependent thermal conductivity, which accelerates heat dissipation. The oscillatory behavior of horizontal displacement diminishes with increased thermal conductivity variation. The amplitude reduces notably for higher \(K_{1}\), reflecting the energy loss through enhanced thermal conduction, which suppresses the mechanical response. Similar to horizontal displacement, vertical displacement exhibits higher initial amplitudes for smaller \(K_{1}\) and diminishes more rapidly as thermal conductivity becomes temperature-dependent. This demonstrates the coupled effect of thermal and mechanical fields, where temperature variations dampen the mechanical wave propagation. The carrier density decreases more steeply with increasing thermal conductivity dependence. This behavior indicates that the thermal effect accelerates the redistribution of photo-generated carriers, reducing their concentration over shorter distances. The stress field displays pronounced oscillations with smaller \(K_{1}\) increases in magnitude (\(K_{1} = - 0.06\)), the oscillations are dampened, reflecting the influence of thermal diffusion on mechanical stress, where enhanced heat conduction mitigates stress accumulation. The pore pressure initially increases and then oscillates as the distance progresses. Higher thermal conductivity variation (\(K_{1} = - 0.06\)) amplifies the oscillations, indicating that thermal effects strongly influence fluid flow behavior within the porous medium. The results emphasize the significant role of variable thermal conductivity in the coupled photo-thermo-mechanical responses of hydro-semiconductor media. As thermal conductivity becomes more temperature-dependent, thermal diffusion increases, leading to faster dissipation of thermal energy, reduced mechanical wave amplitudes, and accelerated redistribution of carriers and fluid pressure. The rotational field and decay parameter further influence wave attenuation and propagation characteristics, highlighting the interplay between thermal, mechanical, and fluid fields in such complex media.

The impact of the fractional-order parameter

Figure 2 illustrates the impact of the fractional-order parameter on the key dimensionless physical fields (temperature, displacements, carrier density, stress, and pore water pressure) in a hydro-semiconductor medium under rotational effects and variable thermal conductivity, with a decay parameter. Three cases are considered: \(\alpha = 0\)(classical derivative, CD), \(\alpha = 0.5\)(fractional case, FR), and \(\alpha = 1\) (local derivative, LS model). The temperature field reveals that the classical derivative (\(\alpha = 0\)) decays more rapidly compared to the fractional case and local derivative, indicating that fractional effects extend the influence of thermal diffusion over a larger spatial domain. The two displacement components show significant oscillations, with \(\alpha = 0.5\) producing intermediate damping behavior, highlighting the fractional model’s role in balancing local and nonlocal characteristics. Carrier density (middle-right) exhibits sharper peaks in the local case (\(\alpha = 1\)), while the fractional case smoothens the distribution. Stress and excess pore water pressure display oscillatory behavior, with the fractional case providing a transition between highly damped (\(\alpha = 0\)) and less damped (\(\alpha = 1\)) responses. This analysis reveals that the fractional-order parameter significantly influences wave propagation, thermal diffusion, and mechanical responses, offering a versatile framework to capture both local and memory-dependent behaviors in hydro-semiconductor systems under rotational effects. These findings reveal behaviors not captured by previous classical or fractional-only models, confirming that the simultaneous treatment of fractional conduction, rotation, and variable conductivity yields qualitatively new wave propagation characteristics.

Impact decay parameter

Figure 3 illustrates the wave propagation of the primary physical fields against distance \(x\) for varying decay parameters under the combined effects of a rotational field and variable thermal conductivity \(K_{1} = - 0.06\) with fractional heat order \(\alpha = 0.5\). The results demonstrate that the decay parameter significantly influences the amplitude and attenuation of the wave profiles. For temperature and carrier density fields, increasing the decay parameter leads to more rapid attenuation as the distance increases, indicating stronger energy dissipation. The horizontal and vertical displacements exhibit oscillatory behavior, with the amplitude and wavelength varying based on the decay parameter, reflecting the influence of thermal and rotational effects on elastic deformation. Similarly, the normal stress and excess pore water pressure fields show more pronounced oscillations and slower attenuation for smaller decay parameters, while larger values accelerate the damping of oscillations. Physically, this suggests that higher decay parameters enhance energy dissipation and reduce wave propagation effects, while the rotational field and variable thermal conductivity modulate the interaction between thermal, mechanical, and elastic responses in the medium.

Wave propagation of the primary physical fields against distance for different decay parameter values under the influence of a rotational field, fractional order, and variable thermal conductivity. The computations are carried out to demonstrate the effect of decay parameters on wave oscillatory behavior.

Parameter ranges and stability

To ensure that the obtained analytical and numerical solutions are physically meaningful and stable, the material constants and governing parameters must lie within admissible ranges. The following restrictions are imposed:

-

Fractional-order parameter: \(0 < \alpha \le 1\). Values less than unity capture subdiffusive and memory-dependent heat transport, while \(\alpha = 1\) recovers the classical Fourier conduction case.

-

Thermal conductivity parameter: \(K(T) = K_{0} (1 + K_{1} T)\) requires \(1 + K_{1} T > 0\), which is satisfied for small negative \(K_{1}\).

-

Decay parameter: \(\lambda > 0\), representing exponential attenuation of waves. Larger values increase damping.

-

Rotational parameter: \(\Omega > 0\), representing angular velocity; finite positive values are considered in this study.

-

Porosity: \(0 < n_{o} < 1\), ensuring realistic hydro-semiconductor behavior.

-

Other material constants: Lamé’s constants satisfy \(\mu > 0\) and; densities \(\lambda\)\(\rho ,\rho_{s} ,\rho_{w} > 0\); diffusion coefficient \(D > 0\); relaxation times \(\tau_{0} > 0\); and heat capacities \(C_{E} > 0\).

These restrictions guarantee thermodynamic consistency and stability of the model. The simulations reported here are based on the physical constants of poro-silicon (Table 1), but the methodology is general and can be applied to other hydro-semiconductor materials as long as the above parameter conditions are satisfied.

Validation with earlier studies

It is important to emphasize that the present results are consistent with previously published works in special cases. When the fractional-order parameter is set to unity (\(\alpha = 1\)), our results reduce to those of the classical Fourier conduction model, in agreement with43. Similarly, neglecting variable thermal conductivity recovers the results reported in41, while ignoring rotational effects yields the outcomes of44. Furthermore, when the thermal relaxation parameter is considered, the solutions converge to the Lord–Shulman model, while neglecting it recovers the classical coupled thermoelasticity (CD) theory47. These consistencies confirm the correctness and reliability of the present computational framework.

It is worth noting that while direct experimental validation of the present fractional-rotational hydro-semiconductor model remains challenging due to the complexity of simultaneously accounting for rotation, variable thermal conductivity, and fractional heat transport, our approach is consistent with the physical mechanisms reported in fractional thermoelasticity literature51,53,54. The agreement of our results with well-established limiting cases (Fourier, LS, fractional-only, and rotation-only models) provides strong theoretical validation. Future studies may extend this work toward experimental or molecular-dynamics-based comparisons to further substantiate the applicability of the proposed framework in realistic semiconductor systems (see Table 2).

Conclusions

The main novelty of this study lies in the integration of fractional-order heat conduction with temperature-dependent thermal conductivity in a rotating hydro-semiconductor medium. This combined framework advances beyond existing models by capturing both nonlocal memory-driven effects and nonlinear conductive responses under rotation, offering new predictive capabilities for optoelectronic, thermoelectric, and microelectromechanical applications. This study presented a comprehensive model for wave propagation in hydro-semiconductor media by simultaneously incorporating fractional-order heat conduction, temperature-dependent thermal conductivity, and rotational effects within a unified photo-thermoelastic framework. Unlike classical and fractional-only approaches, the proposed model accounts for memory-driven heat transport, nonlinear thermal conductivity, and Coriolis-induced anisotropy, thereby providing a broader and more realistic description of thermal, mechanical, and carrier field interactions. The numerical results revealed that fractional-order parameters extend the thermal influence range and provide smoother transitions between local and nonlocal responses, while temperature-dependent conductivity accelerates energy dissipation and strongly modulates displacement, stress, and pore pressure oscillations. The decay parameter was shown to control the attenuation rate, whereas rotational effects introduced significant modifications in wave dispersion and anisotropy.

Validation against limiting cases confirmed consistency with Fourier conduction, Lord-Shulman, and previously reported fractional and rotational models, establishing the correctness of the present formulation. From an application standpoint, the findings have direct implications for micro- and nano-scale technologies, including MEMS/NEMS, optoelectronic systems, bio-sensing devices, and thermal management in semiconductor manufacturing. In geophysical and energy engineering contexts, the model also provides insights into wave behavior in porous thermoelastic media subjected to rotational forces. Future research may extend this framework to nonlinear excitations, transient regimes, and multi-dimensional geometries, thereby enabling broader applicability in advanced semiconductor and energy-harvesting technologies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(\lambda ,\,\mu > 0\) :

-

Lame’s parameters

- \(\delta_{n} = (3\lambda + 2\mu )d_{n}\) :

-

Deformation potential coefficient

- \(T\) :

-

Absolute temperature

- \(T_{0} \;\) :

-

Reference temperature

- \(\gamma = (3\lambda + 2\mu )\alpha_{s}\) :

-

The thermal expansion of volume

- \(\alpha_{s}\) :

-

The thermal expansion coefficient of semiconductor grains

- \(\rho_{s} > 0\) :

-

Density of semiconductor grains

- \(\rho_{w} > 0\) :

-

Density of pore water

- \(\rho > 0\) :

-

The density of the medium

- \(d_{n}\) :

-

The electronic deformation coefficient

- \(C_{e}\) :

-

Specific heat of the medium

- \(K_{0} > 0\) :

-

Constant thermal conductivity

- \(D_{E}\) :

-

The carrier diffusion coefficient

- \(\tau > 0\) :

-

Lifetime

- \(t\) :

-

Time variable

- \(E_{g}\) :

-

The energy gaps

- \(u_{i}\) :

-

Displacement vector

- \(N\) :

-

Carrier concentration (density)

- \(m\) :

-

Volumetric heat capacity of medium

- \(0 < n_{o} < 1\) :

-

Porosity

- \(\tau_{0}\) :

-

Thermal memory

- \(P\) :

-

Excess pore water pressure

- \(\alpha_{w}\) :

-

Thermal expansion coefficient of pore water

- \(g\) :

-

Gravity

- \(\sigma_{ij}\) :

-

The stress tensor

- \(C_{w} > 0\) :

-

Heat capacity of pore water

- \(C_{s} > 0\) :

-

Heat capacity of semiconductor grains

- \(k_{d}\) :

-

Coefficient of permeability

- \(P\) :

-

Excess pore water pressure

- \(e\) :

-

Cubical dilatation

- \(d_{n}\) :

-

The coefficient of electronic deformation

References

Biot, M. A. Thermoclasticity and irreversible thermodynamics. J. Appl. Phys. 27, 240–253 (1956).

Lord, H. W. & Shulman, Y. A generalized dynamical theory of thermolasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 15, 299–306 (1967).

Green, A. E. & Lindsay, K. A. Thermoelasticity. J. Elasticity. 2, 17 (1972).

Green, A. & Naghdi, P. A reexamination of the basic results of themomechanics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 432, 171–194 (1991).

Green, A. & Naghdi, P. On undamped heat waves in an elastic solid. J. Therm. Stresses 15, 252–264 (1992).

Tzou, D. Y. A unified field approach for heat conduction from macro to micro scales. ASME J. Heat Transf. 117, 8–16 (1995).

Youssef, H. M. Theory of two-temperature-generalized thermoelasticity. IMA J. Appl. Math. 71, 383–390 (2006).

Hetnarski, R. B. & Ignaczak, J. Generalized thermoelasticity. J. Therm. Stresses 22, 451–476 (1999).

Lata, P. & Kaur, I. A study of transversely isotropic thermoelastic beam with green-Naghdi type-II and type-III theories of thermoelasticity. Appl. Appl. Math. 14(1), 17 (2019).

Lotfy, Kh. Mode-I crack in a two-dimensional fibre-reinforced generalized thermoelastic problem. Chin. Phys. B 21(1), 014209 (2012).

Ailawalia, P. & Singh, N. Effect of rotation in a generalized thermoelastic medium with hydrostatic initial stress subjected to ramp type heating and loading. Int. J. Thermophys. 30, 2078–2097 (2009).

Abbas, I. & Kumar, R. Response of thermal source in initially stressed generalized thermoelastic half-space with voids. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 11(6), 1472–1479 (2014).

Bachher, M., Sarkr, N. & Lahiri, A. Generalized thermoelastic infinite medium with voids subjected to an instantaneous heat source with fractional derivative heat transfer. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 89, 84–91 (2014).

Ailawalia, P. & Marin, M. Response of a semiconducting medium under photothermal theory due to moving load velocity. Waves Random Complex Media 32(4), 1644–1653. https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2020.1831709 (2020).

Marin, M., Öchsner, A. & Bhatti, M. Some results in Moore-Gibson-Thompson thermoelasticity of dipolar bodies, (ZAMM) Zfur Angew. Math. Mech. 100(12), e202000090 (2020).

Lotfy, Kh. & Hassan, W. Effect of rotation for two-temperature generalized thermoelasticity of two-dimensional under thermal shock problem. Math. Probl. Eng. 13, 297274. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/297274 (2013).

Abo-Dahab, S., Abd-Alla, A. & Alqarni, A. A two-dimensional problem with rotation and magnetic field in the context of four thermoelastic theories. Results Phys. 7, 2742–2751 (2017).

Gordon, J., Leite, R., Moore, R., Porto, S. & Whinnery, J. Long-transient effects in lasers with inserted liquid samples. Bull. Am. Phys. Soc. 119, 501–510 (1964).

Kreuzer, L. Ultralow gas concentration infrared absorption spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 42(7), 2934–2943 (1971).

El-Sapa, S., Almoneef, A., Lotfy, Kh., El-Bary, A. & Saeed, A. Moore-Gibson-Thompson theory of a non-local excited semiconductor medium with stability studies. Alex. Eng. J. 61(12), 11753–11764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2022.05.036 (2022).

Hosseini, S. & Zhang, C. Plasma-affected photo-thermoelastic wave propagation in a semiconductor Love-Bishop nanorod using strain-gradient Moore–Gibson–Thompson theories. Thin-Walled Struct. 179, 109480 (2022).

Abouelregal, A., Sedighi, H. & Megahid, S. Photothermal-induced interactions in a semiconductor solid with a cylindrical gap due to laser pulse duration using a fractional MGT heat conduction model. Arch. Appl. Mech. 93, 2287–2305 (2023).

Liu, J., Han, M., Wang, R., Xu, S. & Wang, X. Photothermal phenomenon: Extended ideas for thermophysical properties characterization. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 065107. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0082014 (2022).

Lotfy, Kh., Elidy, E. & Tantawi, R. Photothermal excitation process during hyperbolic two-temperature theory for magneto-thermo-elastic semiconducting medium. SILICON 13, 2275–2288 (2021).

Lotfy, Kh., El-Bary, A., Ismail, E. & Atef, H. Analytical solution of a rotating semiconductor elastic medium due to a refined heat conduction equation with hydrostatic initial stress. Alex. Eng. J. 59(6), 4947–4958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2020.09.012 (2020).

Lotfy, Kh., El-Bary, A. & El-Sharif, A. Ramp-type heating microtemperature for a rotator semiconducting material during photo-excited processes with magnetic field. Results Phys. 19, 103338 (2020).

Askar, S., Abouelregal, A., Marin, M. & Foul, A. Photo-thermoelasticity heat transfer modeling with fractional differential actuators for stimulated nano-semiconductor media. Symmetry 15, 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15030656 (2023).

Zakaria, K., Sirwah, M., Abouelregal, A. & Rashid, A. Photo-thermoelastic model with time-fractional of higher order and phase lags for a semiconductor rotating materials. SILICON 13, 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-020-00451-z (2021).

Zenkour, A. & Abouelregal, A. Fractional thermoelasticity model of a 2D problem of mode-I crack in a fibre-reinforced thermal environment. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 5(2), 269–280 (2019).

Adel, M., Lotfy, Kh., Yadav, A. & Ibrahim, E. Orthotropic rotational semiconductor material with piezo-photothermal plasma waves with moisture plasma diffusion and laser pulse. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. https://doi.org/10.1002/zamm.202301004 (2024).

Liu, H. & Wang, F. A novel semi-analytical meshless method for the thickness optimization of porous material distributed on sound barriers. Appl. Math. Lett. 147, 108844 (2024).

Kumar, R. & Devi, S. Thermomechanical interactions in porous generalized thermoelastic material permeated with heat sources. Multidiscip. Model. Mater. Struct. 4, 237–254 (2008).

Sherief, H. & Hussein, E. A mathematical model for short-time filtration in poroelastic media with thermal relaxation and two temperatures. Transp. Porous Media 91, 199–223 (2012).

Abbas, I. & Youssef, H. Two-dimensional fractional order generalized thermoelastic porous material. Latin Am. J. Solids Struct. 12, 1415–1431 (2015).

Wei, W., Zheng, R., Liu, G. & Tao, H. Reflection and refraction of P wave at the interface between thermoelastic and porous thermoelastic medium. Transp. Porous Media 113, 1–27 (2016).

Schanz, M. Poroelastodynamics: linear models, analytical solutions, and numerical methods. Appl. Mech. Rev. 62(3), 030803. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3090831 (2009).

Marin, M., Hobiny, A. & Abbas, I. Finite element analysis of nonlinear bioheat model in skin tissue due to external thermal sources. Mathematics 9(13), 1459 (2021).

Abousleiman, Y. & Ekbote, S. Solutions for the inclined borehole in a porothermoelastic transversely isotropic medium. Trans. ASME. E J. Appl. Mech. 72, 102–114 (2005).

Booker, J. & Savvidou, C. Consolidation around a spherical heat source. Int. J. Solids Struct. 20, 1079–1090 (1984).

Biot, M. Variational Lagrangian-thermodynamics of non-isothermal finite strain mechanics of porous solids and thermomolecular diffusion. Int. J. Solids Struct. 13, 579–597 (1977).

Xiong, C., Ying, G. & Yu, D. Normal mode analysis to a poroelastic half-space problem under generalized thermoelasticity. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 14(5), 930–949. https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-78253611 (2017).

Marin, M., Abbas, I. & Kumar, R. Relaxed Saint-Venant principle for thermoelastic micropolar diffusion. Struct. Eng. Mech. 51(4), 651–662 (2014).

Kimmich, R. Strange kinetics, porous media, and NMR. J. Chem. Phys. 284, 243–285 (2002).

Alshehri, H. & Lotfy, Kh. A novel hydrodynamic semiconductor model under Hall current effect and laser pulsed excitation. Phys. Fluids 36(12), 122005. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0241229 (2024).

Raddadi, M., Alotaibi, M., El-Bary, A. & Lotfy, Kh. A novel generalized photo-thermoelasticity model for hydro-poroelastic semiconductor medium. AIP Adv. 14(12), 125104 (2024).

Youssef, H. & El-Bary, A. Thermal shock problem of a generalized thermoelastic layered composite material with variable thermal conductivity. Math. Probl. Eng. 2006(87940), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/mpe/2006/87940 (2006).

El-Sapa, Sh., Lotfy, Kh., Elidy, E., El-Bary, A. & Tantawi, R. Photothermal excitation process in semiconductor materials under the effect moisture diffusivity. SILICON 15, 4171–4182 (2023).

Yasein, M., Mabrouk, N., Lotfy, Kh. & El-Bary, A. The influence of variable thermal conductivity of semiconductor elastic medium during photothermal excitation subjected to thermal ramp type. Results Phys. 15, 102766 (2019).

Abbas, I., Hobiny, A. & Marin, M. Photo-thermal interactions in a semi-conductor material with cylindrical cavities and variable thermal conductivity. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 14(1), 1369–1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/16583655.2020.1824465 (2020).

Sharma, A., Sharma, J. & Sharma, Y. Modeling reflection and transmission of acoustic waves at a semiconductor: fluid interface. Adv. Acoust. Vib. 2012, 637912 (2012).

Tiwari, R. & Mukhopadhyay, S. On harmonic plane wave propagation under fractional order thermoelasticity: an analysis of fractional order heat conduction equation. Math. Mech. Solids 22(4), 782–797. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081286515612528 (2015).

Tiwari, R. Magneto-thermoelastic interactions in generalized thermoelastic half-space for varying thermal and electrical conductivity. Waves Random Complex Media 34(3), 1795–1811. https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2021.1948146 (2021).

Yu, Y. J., Tian, X. G. & Liu, J. Size-dependent damping of a nanobeam using nonlocal thermoelasticity: extension of Zener, Lifshitz, and Roukes’ damping model. Acta Mech. 228, 1287–1302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-016-1769-0 (2017).

Saeed, S. T., Riaz, M. B. & Baleanu, D. A fractional study of generalized Oldroyd-B fluid with ramped conditions via local & non-local kernels. Nonlinear Eng. 10(1), 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1515/nleng-2021-0013 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORFFT-2025-049-1), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.A. and I.E. Project administration, conceived of the presented idea and visualization, and wrote the manuscript. M.A. developed the theory and performed the computations. A.E. and K.L. Data curation, verified the analytical methods; encouraged the methodology. F. A. to investigate and supervise the findings of this work. L. J. software, validation, reviewing, and editing. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the preparation of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elshazly, I.S., Alshormani, F., El Nasr, M.A. et al. Fractional heat conduction with variable thermal conductivity in rotating hydro-semiconductors. Sci Rep 15, 34889 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18621-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18621-7