Abstract

Sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE) is a major complication in intensive care units, characterized by diffuse brain dysfunction due to systemic inflammation. Despite advances in critical care medicine, SAE remains a key factor in poor patient outcomes, with its pathogenesis closely related to mitochondrial damage and the release of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). In this study, we integrated multiple transcriptomic and single-cell sequencing datasets to comprehensively analyze mitochondrial-associated differentially expressed genes (MitoDEGs) in SAE brain tissues. Using machine learning algorithms, we identified three core biomarkers (ALDH7A1, HOGA1, and AA467197). Functional enrichment analysis showed that the upregulated genes in SAE were mainly involved in immune and inflammatory responses, while the downregulated genes were associated with mitochondrial metabolism and vascular functions. Based on MitoDEGs, clinical subtype analysis shows that changes in mitochondrial function can effectively distinguish three sepsis subtypes (Cluster 1–3). Among these, Cluster 3 had worse prognosis due to enhanced mitochondrial function and activated inflammatory pathways. Immune microenvironment analysis revealed that MitoDEGs were closely associated with damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) signaling and the expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes. Experimental validation showed that exogenous mtDNA significantly increased the levels of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6), thereby aggravating brain tissue pathological damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) are the most prevalent diseases and leading causes of mortality in intensive care units (ICUs)1. Despite significant advancements in modern medicine and healthcare, which have increased survival rates among critically ill patients with sepsis and MODS, clinicians frequently observe a concerning phenomenon: many ICU patients develop disturbances in consciousness or cognitive decline unrelated to their primary disease after its control2. This diffuse cerebral dysfunction and altered consciousness, induced by sepsis, is termed Sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE)3. Notably, SAE can manifest even in the absence of bacterial invasion into the central nervous system or bloodstream. It arises from systemic inflammatory responses triggered by infection, where severe sepsis releases oxidative products, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and other inflammatory mediators that act on the brain. These mediators induce cerebral inflammation, brain edema, neuronal degeneration, microglial activation, and energy metabolism disorders, ultimately leading to acute, diffuse cerebral dysfunction. Central nervous system inflammation plays a pivotal role in this process4.

However, exogenous pathogenic infections are not the sole cause of systemic inflammatory responses5. The endosymbiont hypothesis6 posits that mitochondria evolved from aerobic bacteria engulfed by ancestral eukaryotic cells through long-term symbiotic adaptation. mtDNA shares similarities with bacterial DNA, containing abundant unmethylated CpG sequences that can induce inflammatory responses akin to those triggered by bacterial infections. The mtDNA copy number (mtDNAcn) in each cell reflects mitochondrial health, with both decreased and elevated mtDNAcn indicating potential dysfunction7. During sepsis, excessive mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production6 reduces mitochondrial membrane potential and compromises membrane integrity, leading to the release of mtDNA into the circulation8. Circulating mtDNA, like bacterial and viral unmethylated CpG-DNA, specifically activates Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9). TLR9-mediated neutrophil release of IL-6 and matrix metalloproteinases 8/9 (MMP8/9) synergistically activates inflammasomes9generating cascade-amplified inflammatory responses that contribute to neurological abnormalities and neuropsychiatric symptoms of excitation or inhibition.

Studies have demonstrated that mitochondrial structural and functional impairments in rat brain tissues peak approximately 24 h post-sepsis onset10. Thus, effectively blocking the amplifying effect of circulating mtDNA on cerebral inflammation during sepsis represents a critical therapeutic target for SAE. Under pro-oxidative conditions, abnormal mitochondrial metabolism and respiratory function have been increasingly identified as potential distinguishing features of sepsis11,12. Given the mitochondrial activity abnormalities in SAE pathogenesis, identifying novel key mitochondrial-related genes is essential to better understand SAE mechanisms and develop molecular diagnostics and therapies. The establishment of large-scale sample databases and biochip development enables bioinformatics technologies to elucidate disease components at multi-omics levels. However, to our knowledge, no studies have identified disease-specific biomarkers for SAE through bioinformatics analysis of mitochondrial-related genes.

In this study, we integrated transcriptomic profiling and single-cell technologies to systematically map mitochondrial-associated differentially expressed genes (MitoDEGs)13 within the brain transcriptome of SAE. We further explored the potential regulatory interactions between key MitoDEGs and the immune microenvironment in SAE, as well as their associations with mitochondrial metabolic functions. To bridge central mitochondrial dysfunction with systemic biomarkers, circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA (ccf-mtDNA) was selected as a peripheral indicator of mitochondrial damage. Ccf-mtDNA represents free-floating, non-encapsulated double-stranded DNA fragments released from damaged mitochondria into biological fluids14. Functioning as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP), ccf-mtDNA activates innate immune-inflammatory responses through intercellular signaling15. Given its high detectability in human biofluids (e.g., blood, cerebrospinal fluid), ccf-mtDNA has emerged as a promising biomarker for inflammatory disorders, with established roles in sepsis-related pathologies16,17,18. Therefore, we propose ccf-mtDNA as a systemic marker for assessing mitochondrial dysfunction, and explore its potential association with the molecular subtypes of sepsis-associated encephalopathy, aiming to validate the pathophysiological role of mitochondrial functional changes in sepsis-associated encephalopathy.

Materials and methods

Reagents

The Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining Kit (cat. no. G1120) and Scott’s Bluing Solution (cat. no. G1865) were purchased from Solarbio (USA); Rat Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) ELISA Kit (cat. no. EK0526), Rat Interleukin-6 (IL-6) ELISA Kit (cat. no. EK0412), and Rat Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) ELISA Kit (cat. no. EK0393) were obtained from Boster (USA); HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L), Affinity-purified (cat. no. ZB-2301) was supplied by Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology (ZSGB-BIO, China); Rabbit Polyclonal Anti-AQP4 (cat. no. bs-0634R) and Rabbit Polyclonal Anti-HPA (cat. no. bs-25726R) were purchased from Bioss (China); Rabbit Polyclonal Anti-MMP9 (cat. no. bs-4593R) was obtained from Abcam (UK); and the ONE-4-ALL Genomic DNA Mini-Extraction Kit (cat. no. B618503) was purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

Data acquisition and preprocessing

The RNA - sequencing datasets used in this study were sourced from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo)19. Supplementary Table S1 provides a summary of comprehensive baseline data. The GSE253438 dataset contains 48 samples of young mouse brain tissue, among which 30 are from mice with acute systemic inflammation induced by intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and 18 are from control mice20. The GSE65682 dataset includes 760 blood samples from patients with sepsis21. The GSE198861 dataset describes 24 brain tissue samples from mice with and without microglial depletion after sepsis induction22. The GSE198862 dataset contains 14 transcriptome data of mouse brain tissue on days 3 and 20 after sepsis induction22. GSE198871 is a combination of GSE198861 and GSE198862, with data integration quality assessment presented in Supplementary Figure S1. All datasets have been normalized through annotated probe screening and other data cleaning operations.

Additionally, a single - cell sequencing dataset, GSE10190123, was recruited for this study. Mice of the same age and strain underwent hippocampal DropSeq sequencing on day 4. Quality control and analysis were performed using the “Seurat” R package24. Cells were filtered according to the following criteria: the number of genes must be in the range of 200 to 5000, the proportion of mitochondrial genes should not exceed 5% (pctMT = 5), and the proportion of hemoglobin genes should be less than 5% (pctHB = 5). These thresholds are used to exclude low-quality cells (such as dying cells, which are characterized by low gene counts or high mitochondrial content) and potential double or multiple cells, and can also filter out cells with high hemoglobin gene expression due to red blood cell contamination. The cell data that passed the quality screening were sequentially subjected to basic standardization steps such as NormalizeData, FindVariableFeatures, ScaleData, RunPCA, FindNeighbors, and FindClusters, and cell types were manually annotated based on the CellMarker 2.0 database25.

Identification of MitoDEGs andfunctional enrichment analysis

Using the R package “DESeq2“26differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the SAE and HC groups in the GSE253438 dataset were analyzed. Statistical significance was determined by |log2FoldChange| > 1 and an adjusted p-value < 0.05. The mitochondrial protein database MitoCarta3.0 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mitocarta)27 was used to screen for genes with high-confidence mitochondrial localization. By overlapping the DEGs and mitochondrial-localized genes, SAE-related mitochondrial differentially expressed genes (MitoDEGs) were identified. Subsequently, pathway enrichment analysis was performed on the DEGs: Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses28 were conducted using the R packages “clusterProfiler“29 and “org.Hs.eg.db“30 respectively, with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Consensus clustering based on Mitochondria-Related genes and pathway enrichment analysis in Severity-Based subtypes

Consensus clustering is a technique employed to identify the potential number and composition of clusters within a dataset, such as microarray gene expression data. In this study, we utilized the “ConsensusClusterPlus” R package31 to conduct consensus clustering on the GSE65682 dataset, focusing on mitochondria-related genes, with the aim of more accurately distinguishing sepsis subtypes. The range of cluster numbers was set from 2 to 9, and 100 iterations were performed to assess the stability of clustering. Each time, 80% of the total dataset was randomly subsampled for analysis. The k-means algorithm was employed as the clustering method, and the Euclidean distance was selected as the distance metric (distance = “euclidean”). Then, we used the “Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA)” and “Limma” R packages32 to analyze the altered pathways in different severity subtypes, respectively.

Weighted gene Co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) and machine learning for identifying candidate biomarkers

The R package “WGCNA” was utilized to perform Weighted Gene Co - expression Network Analysis33which helps in pinpointing co - expression modules and their correlation with diseases. We began by selecting MitoDEGs identified in prior studies. The optimal soft - thresholding power β was determined using the “pickSoftThreshold” function, with a mean connectivity R2 threshold of 0.9. An adjacency matrix was converted into a Topological Overlap Matrix (TOM) to calculate gene connectivity and dissimilarity. Co - expression modules were identified via hierarchical clustering and dynamic tree cutting. Modules were associated with diseases by calculating gene significance (GS) and module membership (MM), and genes with the strongest correlation were picked out for further analysis.

To strengthen the selection process of hub candidate genes, three distinct machine learning algorithms were employed. The SVM - RFE method was carried out using the “e1071“34 and “caret“35 packages. The RF method was implemented with the support of the “randomForest” package36. Additionally, the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression, known for its ability to perform variable selection and regularization, was also applied to help identify key genes. The results from each algorithm were analyzed using Venn diagrams to determine the overlapping genes.

Expression analysis and diagnostic evaluation of candidate biomarkers

In this study, the “ggplot2” package37 was used to evaluate and compare the expression levels of potential biomarkers between the control and disease groups, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Additionally, a nomogram was constructed using the “rms“38 package as a visual tool to predict the likelihood of specific outcomes based on the individual scores of candidate genes. Here, the “score” refers to the value assigned to each candidate gene, while the “total score” represents the cumulative score derived from all relevant genes. To evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of the candidate biomarkers, the areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and precision-recall (PR) curve (AUC) were calculated using the “pROC”39and “PRROC”40packages.

Immune infiltration analysis

The CIBERSORT algorithm, based on RNA-seq or microarray data, is a deconvolution method that utilizes linear support vector regression to determine the infiltration abundance of 22 immune cell types within a sample. In this study, the “CIBERSORT” algorithm in R was used to measure the abundance of 22 immune cell types in SAE and healthy samples (GSE253438). The correlation between each central MitoDEG and the 22 immune cells was examined via Spearman’s rank correlation analysis, with results presented in lollipop and heatmap plots. R’s “ComplexHeatmap” package41 was used to create heatmaps and cluster analyses for a visual display of correlations.

Cell-Cell interaction analysis using cellphonedb

This study uses the AddModuleScore42method to calculate scores for gene modules related to damage - associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)43 in cells. By incorporating predefined DAMPs - related feature gene sets, this method quantifies DAMPs - related signaling activity in each cell based on single - cell transcriptomic data. To explore DAMPs’ role in severe sepsis - associated encephalopathy (SAE), CellChat R package (version 1.6.1)44 is used to estimate receptor - ligand pair expression across cell types, determining specific signaling pathways. Receptor - ligand interaction data comes from CellChatDB45. Based on this data, marker genes of source and target cell types in CellChatDB are compared to check for significant associations between cell types with different scores.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) extraction and purification

Take the hippocampus of male SD rats and homogenize with STE buffer. Centrifuge at 1500 rpm for 15 min at 0 °C and take the supernatant; centrifuge the supernatant at 12,000 rpm for 40 min to obtain the precipitate (mitochondria), and repeat the differential centrifugation. Resuspend the precipitate in STE, let it stand at room temperature for 15 min, then centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. Add TEN to the precipitate for suspension, add SDS and ice-bath for 10 min, then add KAC and ice-bath for 30 min. Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 8 min, take the supernatant, add 2 volumes of ethanol, and precipitate at -20 °C for 30 min to obtain crude mtDNA. Add RNase A to the crude DNA and digest at 37 °C for 30 min. After phenol extraction, extract with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol, and then extract again with chloroform. Add ethanol to the supernatant and precipitate at -20 °C. After centrifugation, the purified mtDNA is dissolved in TE, the concentration and purity are measured, adjusted to 10 µg/ml, and stored at -20 °C for later use.

Animal maintaining

In this study, 40 SPF-grade adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (provided by Genebio Company, Guangzhou) were selected. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Ethics Approval No.: 2021-8-013). The SD rats were randomly divided into the sham operation group (Sham, n = 10) and the sepsis model group (CLP, n = 30). One week before the operation, electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring electrodes were implanted, and the rats were fasted for 12 h. All rats were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation. The CLP group underwent cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). The specific operation included ligating the distal 1/3 of the cecum, puncturing twice with a 20-gauge needle, and squeezing out the intestinal contents. The sham operation group received the same operations except for cecal ligation and puncture. After the operation, the animals were housed in an SPF-grade animal laboratory and managed in accordance with international regulations for the use and protection of animals. During the experiment, the rats had free access to food and water, the temperature was maintained at 23 ± 2 °C (with a humidity of 45–65%), and a 12-hour light/dark cycle was controlled. At 8 h after the operation, neurobehavioral scoring was performed to determine whether the SAE model was successfully established. After modeling, 2 animals in the CLP group died, and 10 animals did not meet the criteria for SAE.The 10 rats in the sham operation group were divided into the sham + PBS group (n = 5) and the sham + mtDNA group (n = 5) using the same method. The 10 rats that did not meet the criteria for SAE were included in the sepsis group and divided into the sepsis + PBS group (n = 5) and the sepsis + mtDNA group (n = 5) in the same way mentioned above. The 18 rats with successfully induced models were divided into two groups: SAE + PBS (n = 9) and SAE + mtDNA (n = 9). Twenty-four hours after modeling, 2 ml of PBS and mtDNA (10 µg/ml) were respectively administered via tail vein injection. Twenty-four hours later, the surviving rats were subjected to neurological reflex scoring and EEG monitoring. At the end of the experiment, the rats were euthanized with a high dose of anesthetic agent. Femoral artery blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain tissue samples were collected and stored in a -80 °C freezer for future examination.

Cell culture

Rat microglial cells (from Shanghai, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Cat# ac340723) were cultured in DMEM (GIBCO, Shanghai) with 10% fetal bovine serum. When confluence reached 70%, cells were passaged and grouped into four groups: control, LPS, LPS + mtDNA (10 µl), and LPS + mtDNA (5 µl). Except for the control group treated with PBS, all groups were treated with LPS (1 µg/ml), and the intervention groups received 10 µl–5 µl mtDNA (10 µg/ml) in 2 ml medium. Cells were incubated at 37℃ with 5% CO₂ and collected at 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h for further experiments.

Histological processing and H&E staining

Following fixation and rinsing, brain tissues were dehydrated through an ethanol gradient (70%, 80%, 90%, and absolute ethanol), cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin after wax infiltration. Section (4 μm thickness) were dewaxed, rehydrated, and stained using a hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) kit. Briefly, nuclei were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min, differentiated in 1% acid alcohol (25 s), and blued in warm water (50 °C, 5 min). Cytoplasmic counterstaining was performed with eosin for 2 min. Sections were dehydrated through an ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and mounted with neutral resin for light microscopic observation.

Immunohistochemistry

Deparaffinized brain sections underwent antigen retrieval in citrate buffer, followed by blocking with 5% BSA (37 °C, 30 min). Sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (AQP-4, HPA, MMP-9; 1:100 dilution), then treated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:100, 37 °C, 30 min). DAB (5–10 min) visualized signals, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted.

Enzyme-Linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in serum, CSF, and brain homogenates were measured using commercial ELISA kits. Absorbance at 450 nm was recorded, and concentrations were calculated via standard curve regression.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

Total DNA was extracted (ONE-4-ALL Kit), quantified spectrophotometrically, and amplified using SYBR Green reagents under: 95 °C 30 s (initial denaturation), 40 cycles of 95 °C 5 s, 60 °C 30 s. Melt curve analysis (85 °C) confirmed specificity. Relative mRNA levels (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) were normalized to GAPDH (2 − ΔΔCt method). Absolute mtDNA copies were calculated using plasmid standard curves (Supplementary Table S2).

Statistical analysis

To conduct the statistical analysis, we utilized R software (version 4.2.3), with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

Results

Mitochondrial dysfunction in SAE differential gene expression and pathway analysis

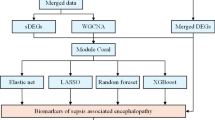

The workflow of this study is illustrated in Fig. 1. Using the GSE253438 dataset, differential expression analysis was performed with DESeq2, identifying a total of 3310 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the SAE group and the control group. The volcano plot (Fig. 2A) revealed 1,524 significantly upregulated and 1,786 downregulated genes in the SAE group. Intersection of these DEGs with 1140 mitochondrial-related genes retrieved from the MitoCarta3.0 database detected 144 overlapping MitoDEGs (38 upregulated and 106 downregulated) in SAE brain tissues (Fig. 2B).

Schematic overview of the study workflow. (1) Identification and validation of mitochondrial differentially expressed genes (MitoDEGs): MitoDEGs were screened using the murine brain transcriptomic dataset (GSE253438), followed by validation and subtyping analysis with human sepsis data (GSE65682); (2) Screening of core biomarkers and diagnostic model construction: Key MitoDEGs (ALDH7A1, HOGA1, AA467197) were identified through WGCNA and machine learning algorithms. A diagnostic nomogram model was established and its performance evaluated in both the training set (GSE253438) and an independent validation cohort (GSE198871); (3) Characterization of the immune microenvironment: Immune infiltration analysis (GSE253438) was integrated with single-cell RNA sequencing data (GSE101901) to systematically profile the dynamic immune landscape in brain tissues of SAE model mice; (4) Experimental validation of mtDNA-mediated inflammatory mechanisms: The critical role of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in microglial inflammatory activation and neuroinflammation in septic rats was experimentally confirmed using animal models. The graphical abstract and workflow of this study were created using Figdraw.

Differentially expressed genes linked to mitochondria and their roles in SAE. A Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE) group and the control group. Genes meeting the significance thresholds (|log2FC| > 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05) are highlighted in red (upregulated in SAE) and blue (downregulated in SAE), respectively. B Venn diagrams displayed the number of MitoDEGs chosen from MitoCarta 3.0’s mitochondria-related genes and up- and down-regulated DEGs. C, D KEGG pathway analysis of upregulated C and downregulated D genes. KEGG is available at www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html and permission for use has been obtained. (E-G) Measurement of mitochondrial DNA copy number levels in serum E, brain tissue (F), and cerebrospinal fluid G, presented as mean ± SD (n = 5–8). The experiment was repeated three times (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). SAE, Sepsis-Associated Encephalopathy; DEG, differentially expressed gene. KEGG, Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

To systematically characterize the biological features of SAE, GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were conducted. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, significantly enriched GO terms were categorized into biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC). Upregulated DEGs in SAE were predominantly associated with immune-related processes, including responses to bacterial-derived molecules, regulation of inflammatory/innate immune responses, and antiviral mechanisms. The downregulated DEGs were enriched in the following terms: extracellular matrix organization, extracellular structure organization, external encapsulating structure organization, vascular process in circulatory system, and transport across blood - brain barrier. KEGG analysis further demonstrated that SAE pathogenesis was closely linked to cytokine-receptor interactions, viral protein-host interactions, COVID-19 signaling, cytoskeleton regulation, neutrophil activation, drug metabolism, and glutathione metabolism (Fig. 2C-D).

Given the crucial role of mitochondria in cellular energy metabolism and immune responses, functional changes in mitochondria often lead to the release of mtDNA, which may play an important role in the pathogenesis of SAE. To test this, we quantified mtDNA levels using real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) in plasma, brain tissues, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) as biomarkers of mitochondrial damage and systemic inflammation.Notably, mtDNA levels in plasma, brain tissues, and cerebrospinal fluid of SAE rats were significantly elevated compared to those in sepsis rats and sham controls (*p* < 0.05) (Fig. 2E–G). This suggests that mitochondrial damage and mtDNA release into the circulation and CNS may contribute to the inflammatory processes and metabolic dysregulation identified in the transcriptomic analyses.

MitoDEGs-Driven molecular subtypes and survival analysis

We used the consensus clustering algorithm to identify different SAE subtype groups based on the MitoDEGs identified in the GSE253438 dataset. The results showed that consensus clustering revealed three molecular subtypes (Cluster 1, Cluster 2, and Cluster 3), with the optimal stability at k = 3. This result is supported by the cumulative distribution function (CDF) curves, and the incremental area change of the maximum consensus score also reaches the minimum (Fig. 3A). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis indicated that there were statistically significant differences in prognosis among the subtypes (log-rank test, P = 0.042). Compared with Cluster 1 and Cluster 2, the survival rate of Cluster 3 was significantly reduced (Fig. 3B).

Characteristics of mitochondrial related gene subgroups. A Consensus matrix of MitoDEGs at k = 3. (B The survival analysis between the three subgroups showed a statistically significant overall difference (P = 0.042). C The expression of MitoDEGs in different subgroups, with red indicating high expression and green indicating low expression.D The expression levels of IL11, CXCL5, AQP1, and AQP5mRNA in different groups. P values were determined by Student’s t-test and Kruskal-Wallis test (NS P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

Mechanistically, Cluster 3 exhibits distinct molecular characteristics. Heatmap analysis highlights the significant upregulation of MitoDEGs in this subtype (Fig. 3C), as well as the increased expression of inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 3D). Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) further revealed significant enrichment of biological processes in Cluster 3. Supplementary Fig. S3A and B illustrate the biological pathways of Cluster 3 compared with Clusters 1 and 2, including GOBP: amino acid transmembrane transport, anterior head development, ammonium transmembrane transport, and amine metabolic process. These findings suggest that Cluster 3 represents a sepsis subtype characterized by altered mitochondrial function and disrupted metabolic reprogramming. This may lead to adverse clinical outcomes through impaired regulation of energy metabolism and inflammatory responses.

Risk prediction and validation of SAE based on WGCNA and machine learning

Based on the GSE253438 dataset, we employed the WGCNA algorithm to identify key gene modules closely associated with the pathogenesis of SAE.A scale-free co-expression network was constructed using WGCNA, which classified 17,221 genes into 8 distinct modules. The topological overlap matrix (TOM) of all module-assigned genes was visualized as a heatmap. Module-trait relationship analysis revealed that the MEturquoise module (containing 5,715 genes) exhibited the strongest positive correlation with SAE (r = 0.88; Fig. 4A–C). Intersection analysis between genes in the MEturquoise module and MitoDEGs yielded 72 overlapping genes.

Identification of potential hub genes. A Heatmap showing the correlation between the SAE and Control groups. The values in the small cells represent the correlation coefficients calculated twice between the eigenvalues of each trait and the eigenvalues of each module, as well as the corresponding statistically significant p-values. The color intensity corresponds to the magnitude of the correlation. A scatter plot of gene significance is also shown. B Soft threshold (power = 8) and scale-free topological fitting index (R2 = 0.9). S Gene hierarchical clustering dendrogram. The horizontal axis represents different genes, while the vertical axis represents the differences between genes. Lower branches indicate reduced differences within the branches (i.e., stronger correlations). D Based on the Lasso regression algorithm, 9 genes corresponding to the lowest binomial deviation are most suitable for SAE diagnosis. E Based on SVM-RFE, the top 12 genes with the smallest error and highest accuracy in SAE were selected. F According to the importance scores of the random forest algorithm in SAE, the top 15 genes were selected and ranked. G The final candidate biomarkers for SAE are shown as overlapping regions in the Venn diagram.

Subsequently, three machine learning models—RF, SVM-RFE, and LASSO—were trained using five-fold cross-validation to screen for SAE-specific diagnostic biomarkers from these 72 candidate genes. LASSO regression identified 9 genes with non-zero coefficients (Fig. 4D), while the SVM-RFE algorithm selected 12 genes demonstrating the lowest root mean square error (Fig. 4E). The RF classifier ranked genes by importance scores and retained those with significance values > 0.5 (Fig. 4F). Venn diagram analysis further prioritized three hub MitoDEGs (ALDH7A1, HOGA1, and AA467197) shared across all three models (Fig. 4G).

To validate the biological significance of ALDH7A1, HOGA1, and AA467197, we conducted comparative analyses between two independent datasets (GSE253438 and GSE198861). The results demonstrated that in the validation set GSE198861, HOGA1 and AA467197 exhibited significant upregulation, while ALDH7A1 showed a marked downregulation trend, with these expression changes directionally consistent with the GSE253438 dataset (Fig. 5A-B). Notably, HOGA1 and AA467197 mRNA levels were higher on day 3 of SAE compared to days 10 and 20. Conversely, ALDH7A1 mRNA levels were lower on day 3 relative to days 10 and 20, suggesting their critical regulatory roles during the acute pathological progression of SAE. To determine whether ALDH7A1, HOGA1, and AA467197 can serve as diagnostic biomarkers for SAE, a nomogram was constructed based on these three genes. In this nomogram, the relative expression level of each gene corresponds to a specific score, and the total score is calculated by summing up the scores of each gene (Fig. 5D).

Evaluation of the diagnostic value and construction of nomograms for candidate biomarkers in the validation datasets. A Differential expression of the three shared genes in the dataset GSE253438. B Differential expression of the three shared genes in the dataset GSE198861. C The detection results of mRNA levels for the genes HOGA1, AA467197, and ALDH7A1 in the GSE198871 dataset across different experimental days. D Nomogram constructed for the three shared genes in the validation dataset GSE198871. E ROC curves of the three shared genes in the GSE253438 dataset. F ROC curves of the three shared genes in the validation dataset GSE198871.

Furthermore, the analyses of ROC curves (Fig. 5E and F) and precision-recall curves (Supplementary Figure S 4) using both the GSE253438 dataset and the independent external validation cohort GSE198871 indicated that these biomarkers have strong diagnostic potential.

Immune microenvironment features reveal mitochondrial gene regulation in SAE

To clarify the immunoregulatory mechanisms of severe sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE), immune infiltration analysis revealed that there are specific patterns of immune changes in the brain tissues of LPS-induced sepsis mouse models (Figs. 6A, B). Specifically, resting NK cells, M1 macrophages, and resting dendritic cells exhibited significantly elevated infiltration levels, whereas resting CD4 + memory T cells, M0 macrophages, and resting mast cells showed markedly reduced infiltration compared to controls. Further analysis of the three hub MitoDEGs demonstrated their divergent immunomodulatory roles. ALDH7A1 expression was positively correlated with M0 macrophages, resting mast cells, and resting CD4 + memory T cells, but negatively correlated with M1 macrophages and resting dendritic cells. In contrast, HOGA1 and AA467197 displayed entirely opposite correlation patterns (Fig. 6C).

Examination of the infiltration of immune cells and the connection between hub genes and distinct immune cells in SAE patients.(A) The bar chart displays the proportions of immune cells in SAE and normal tissues.(B) Heatmap displaying the expression patterns of immune cell types.(C) Heatmap illustrating correlations between genes (HOGA1, ALDH7A1, AA467197) and different immune cell types.(D) Scatter plot matrix demonstrating correlations between genes (HOGA1, ALDH7A1, AA467197) and DAMPs-related genes. (E) Scatter plot matrix for each complex, showing correlations between genes (HOGA1, ALDH7A1, AA467197) and mitochondrial respiratory chain complex-related genes. (F) Correlations between genes (HOGA1, ALDH7A1, AA467197) and inflammatory factors.

Spearman correlation analysis between MitoDEGs and DAMPs-related genes showed that ALDH7A1 was significantly negatively correlated with most DAMPs-associated genes, whereas HOGA1 and AA467197 exhibited positive correlations (Fig. 6D). Additionally, ALDH7A1 expression was inversely associated with mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I-V genes, while HOGA1 and AA467197 showed positive correlations with these genes (Fig. 6E). It is worth noting that ALDH7A1 is negatively correlated with pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1β and TNF-α), whereas HOGA1 and AA467197 are positively correlated with inflammatory mediators. (Fig. 6F).

Overall, the downregulation of ALDH7A1 and the upregulation of HOGA1 and AA467197 may synergistically drive SAE progression by modulating immune cell infiltration, promoting DAMPs signaling, impairing mitochondrial respiratory chain activity, and amplifying inflammatory responses.

Microglia with High DAMPs Scores Regulate Neuroinflammation in SAE through Enhanced Inflammatory Factor Expression and Cellular Interactions.

Through the analysis of the GSE101901 dataset, 12 cell types, including astrocytes and microglia, were identified (Fig. 7A). In the brain tissues of SAE patients, the proportions of astrocytes and microglia significantly increased, while the proportions of CA subtype 1 and CA subtype 2 neurons decreased (Fig. 7B). Using the AddModuleScore algorithm, it was found that microglia and oligodendrocytes had higher DAMPs enrichment scores (Fig. 7C). CellChat analysis revealed that the intensity of ligand-receptor interactions was higher in the high-score group than in the low-score group (Fig. 7D). Scatter plot analysis indicated that astrocytes and oligodendrocyte progenitor cells had high interaction strength and were the core of the cellular communication network, while CA1 neurons had low interaction activity (Supplementary Fig. S5A). Pathway analysis showed that the relative information flow of pathways such as GALECTIN and PDGF was significantly increased in the SAE group (Supplementary Fig. S5B). There were significant differences in the intercellular information flow network between Score Up microglia and Score Down microglia. Figure 7E and Supplementary Fig. 5C show that, compared to the low DAMPs scoring subtype (Score Down microglia), the high DAMPs scoring subtype of microglia (Score Up microglia) exhibits higher interaction intensity and upregulation of inflammatory factor expression. In summary, microglia with high DAMPs scores may play a key role in the neuroinflammatory regulation of SAE by enhancing the expression of inflammatory factors and cellular interactions.

Single-cell sequencing analysis and cell localization. (A) T-SNE plot with cells colored according to annotations. (B) Stacked bar chart showing the percentage of cells in control and SAE samples. (C) T-SNE visualization of high and low DAMPS score distributions. (D) Relationship network between different cell types. (E) Expression of various inflammatory genes in different cell populations.

MtDNA exacerbates SAE pathogenesis via inflammatory pathway activation

Neuroinflammation occupies a central position in the pathogenesis of sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE). Previous bioinformatics analyses have revealed significant associations between mitochondrial differentially expressed genes (MitoDEGs) and immune infiltration or inflammatory pathways. Based on these findings, this study further experimentally validated the crucial role of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in the pathogenesis of SAE. As shown in Fig. 8A, we established a rat model of sepsis-associated brain injury according to the methods and criteria described by Kafa IM et al.46. In vivo experimental results from this model showed that 24 h after intravenous injection of mtDNA, light microscopy revealed no significant abnormalities in the size or morphology of brain tissue cells in the sham-operated group. In contrast, in the sepsis-induced brain injury group, some cells exhibited perinuclear halos, suggesting pyknosis and disorganized cellular arrangement. Compared to the sepsis-induced brain injury group, the brain tissue of the mtDNA-injected group exhibited more severe damage, manifested as significantly greater cellular structural abnormalities and disorganized arrangement (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, the levels of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) in both the brain tissue and plasma of mtDNA-injected rats were also significantly higher than those in the sepsis control group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 8C).

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Stimulation in Septic Rats and Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Inflammatory Response in Microglia(A) Establishment of the SAE Rat Model. (B) Effect of mtDNA on Hippocampal Pathological Alterations in Septic Rats. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used to visualize the tissue sections. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Serum and brain tissue TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels in septic model rats treated with PBS and mtDNA after 24 h. (D) Quantification of mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6. Expression levels were assessed following treatment with LPS, LPS + mtDNA (5 µl), and LPS + mtDNA (10 µl) for 6, 12, and 24 h. Data are presented as fold change relative to PBS-treated controls. *P < 0.05 vs. control group; &P < 0.05 vs. LPS group; #P < 0.05 vs. LPS + mtDNA (5 µl) group. Abbreviations: IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Neuroinflammation serves as the primary pathological basis of septic encephalopathy, with microglial activation playing a pivotal role. Therefore, we selected microglial cells as the research subject to observe the expression changes of pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in response to mtDNA stimulation. In vitro experimental results demonstrated that mtDNA significantly enhanced the LPS-induced inflammatory response in microglial cells. Compared to the LPS stimulation alone group, the secretion levels of these pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) were further elevated (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8D). This result aligns with the activation of pro-inflammatory pathways (such as cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction and NF-κB signaling) identified in prior transcriptomic analyses.

To further explore the role of mtDNA and its downstream signaling pathways, we conducted a comparative analysis on the expression levels of MMP-9, AQP4, and HPA axis-related markers in the hippocampal brain tissues of rats with SAE. The results showed that all the above indicators were highly expressed in the brain tissues of the sepsis encephalopathy rat model, with the most significant upregulation observed in the SE + mtDNA tail vein injection group (Fig. 9).

The effect of mtDNA on the immunoreactivity levels of AQP4, HPA, and MMP − 9 in the hippocampus of septic rats. Compared with the hippocampus of septic rats, the immunoreactivity of AQP4, heparanase, and MMP − 9 in the hippocampus of mtDNA - treated rats was significantly increased. Dark brown indicates immunopositivity. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Discussion

SAE is a common central nervous system complication in patients with sepsis, with an incidence rate ranging from 8 to 70% among sepsis patients46. The pathogenesis of SAE is extremely complex, with inflammation playing a key role. Studies have shown that the characteristic feature of SAE is the increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain, while there is no significant change in cerebral blood flow or direct infection. It is currently believed that the pathogenesis of SAE is closely related to cytokine-mediated microvascular, coagulation system, or organ damage, with neuroinflammation being the underlying cause47. Mitochondrial dysfunction plays an important role in the development of SAE, but research on the role of mitochondrial-related genes in the pathogenesis of SAE remains relatively limited3.

In this study, we integrated multi-omics data to comprehensively analyze the pathological modifications of mitochondria in the SAE environment and identified mitochondrial biomarkers associated with SAE, aiming to provide new insights into the pathogenesis of SAE. Previous studies have demonstrated that mitochondria, as the center of energy metabolism48drive the progression of SAE through kinetic imbalance49oxidative stress50,51and energy metabolism collapse52. Autophagy clearance impairment (disruption of Parkin-dependent/non-dependent pathways) and the release of pro-apoptotic proteins, in concert with calcium overload, activate the caspase cascade, ultimately leading to neuronal programmed death53,54,55. These interactive mechanisms together constitute the multi-dimensional pathological network of brain dysfunction in SAE. In the brain tissue of SAE Mus musculus, 12.6% (144/1140) of mitochondrial-related genes exhibited significant expression differences, indicating widespread disruption of the mitochondrial homeostasis regulation network. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis revealed that upregulated genes were mainly involved in innate immune responses (such as recognition of bacterial molecular patterns and Type I interferon signaling pathways), while downregulated genes were concentrated in processes such as extracellular matrix remodeling (collagen fiber assembly and angiogenesis). This expression pattern further confirms the SAE pathological pattern: On the one hand, overactivation of immune-inflammatory pathways causes neuroinflammation damage56; on the other hand, dysfunction of the vascular support system worsens the metabolic crisis57.

Unlike previous screening methods, this study employed machine learning algorithms to identify SAE-specific diagnostic biomarkers. WGCNA identified modules highly correlated with SAE, and further machine learning models ultimately pinpointed three core MitoDEGs: ALDH7A1, HOGA1, and AA467197. These genes exhibited consistent expression patterns in an independent cohort (GSE198861) and demonstrated strong diagnostic efficacy (ROC-AUC = 0.856). The nomogram constructed based on these biomarkers effectively stratified SAE risk, providing a practical tool for early diagnosis and prognostic assessment.

Mitochondria play a crucial role in integrating cellular immunity, physiological functions, and metabolic regulation. Previous studies have clearly shown that the three genes, ALDH7A1, HOGA1, and AA467197, are closely associated with mitochondrial functions and energy metabolism.The HOGA1 gene encodes the mitochondrial enzyme HOGA1, which can catalyze the final step of mitochondrial hydroxyproline metabolism, converting 4-hydroxy-2-oxoglutarate (HOG) into glyoxylic acid and pyruvate. When the HOGA1 gene mutates, it leads to the deficiency of HOGA1, thereby causing a large accumulation of HOG in mitochondria, and ultimately triggering primary hyperoxalurias (PH). In addition, HOGA1 is highly expressed in the adipose tissue of obese individuals and has a close genetic association with body mass index (BMI). It may function by up - regulating genes related to adipogenesis and inhibiting the expression of genes related to lipolysis58. Moreover, studies have confirmed that HOGA1 also has the effect of inhibiting the growth of various tumors59,60. ALDH7A1 plays an important role in lysine metabolism61. ALDH7A1 is not essential when nutrients are sufficient. However, under energy stress conditions such as hunger and hypoxia, it can inhibit COPI vesicle transport through BARS, thereby maintaining ATP levels and promoting cell survival. At the same time, ALDH7A1 shows specificity in maintaining membrane NADH levels, and membrane NADH is precisely produced by ALDH7A163. Besides, ALDH7A1 can also reduce lipid peroxidation by directly consuming reactive aldehydes and promote the membrane recruitment of FSP1 to resist ferroptosis63.In the B16-F10 melanoma model, the transcription of AA467197 can be induced by interferons (IFN - γ and IFN - β) in the tumor microenvironment, thereby promoting the degradation of NDUFA4. The deficiency of NDUFA4 can trigger mitochondrial stress, leading to the release of mtDNA and the activation of the cGAS - STING pathway, thus amplifying interferon signals64. In addition, the AA467197 gene can also regulate the intensity of immune responses by adjusting the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Under low - dose infection conditions, the abnormal activation of the GSDMD cleavage pathway will significantly aggravate pyroptosis65.

Recent studies have highlighted the significant value of mtDNA in the prognostic assessment of critically ill patients66. Sepsis can induce mitochondrial cellular hypoxia, disrupt the respiratory chain, and ultimately lead to reduced energy production and overexpression of free radicals, thereby exacerbating organ dysfunction12. Therefore, mitochondrial structural and functional impairments play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of SAE. In a SAE mouse model established via cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), severe mitochondrial dysfunction in the hippocampus was observed, accompanied by a significant increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which further induced neuronal apoptosis and enhanced inflammatory responses, thereby promoting the occurrence of SAE14. However, we propose that the role of mitochondria in the pathophysiological processes of SE may extend beyond these mechanisms. According to the theory of DAMPs, in non-infectious immunity, mtDNA, due to its high homology with bacterial DNA, is an important DAMP molecule that can induce innate immune responses in the brain, leading to or amplifying cerebral inflammation15. In vitro experiments have shown that mtDNA can amplify lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation in microglia, with significant increases in TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in the LPS + mtDNA group compared to the LPS group. Similarly, in in vivo experiments, rats injected with mtDNA via the tail vein exhibited significantly higher plasma levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 24 h post-injection compared to control groups, and the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in brain tissue were also significantly higher than those in control groups, confirming that mtDNA can stimulate inflammatory responses in a sepsis rat model. Studies have also demonstrated that plasma free mtDNA is highly expressed in patients with sepsis and correlates with disease severity67. Our experiments similarly found that the level of plasma free mtDNA in sepsis rats was significantly higher than that in control and sham groups, further confirming that the level of plasma free mtDNA is parallel to the severity of sepsis. The level of free mtDNA in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of SAE rats was also higher than that in sepsis and sham groups, suggesting that the level of free mtDNA in CSF is associated with the occurrence of SAE-related brain damage.

It is commonly believed that mtDNA specifically binds to Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) within neutrophils, leading to the phosphorylation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway. Activated neutrophils release matrix metalloproteinases 8/9 (MMP8/9), which disrupt the basement membrane of vascular endothelial cells68resulting in damage to distant organ tissues. Cerebral edema of brain parenchymal cells is a key pathological process in SAE, significantly affecting the recovery of brain cells. Its formation and resolution are closely related to AQP4, which is most abundantly expressed in the gray matter of the brain and spinal cord. HPA is widely expressed in various cells, including neurons, astrocytes, endothelial cells, and macrophages69,70. It is the only known endoglycosidase that degrades heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the extracellular matrix and basement membrane and is involved in neuroinflammatory responses71. Therefore, in the detection and analysis of mtDNA and its downstream signaling pathways, we compared the expression levels of MMP-9, AQP-4, and HPA in the hippocampal brain tissue of SAE rats and found that these proteins were highly expressed in the brain tissue of SAE rats, especially in the SAE + mtDNA tail vein injection group, consistent with the results reported in the aforementioned literature. This indicates that free mtDNA in CSF may act as a special DAMP that binds to TLR9, activates microglia to release MMP-9, and causes brain edema and increased levels of inflammatory factors in the brain.

However, despite the phased achievements of this study, there are still some areas for improvement. In terms of sample selection, the current risk model relies on a limited public database, resulting in insufficient validation. To enhance the credibility and applicability of the model, future research needs to conduct independent prospective cohort analyses and expand the clinical data sample size. Regarding molecular mechanisms, although the study has observed expression differences of ccf-mtDNA in the SAE rat model and changes in the expression levels of MMP-9, AQP-4, and HPA, the specific mechanisms of action between MitoDEGs and these molecules still need to be elucidated. Subsequent research will focus on elucidating the regulatory mechanisms underlying the recruitment and activation of these three genes in innate immune cells of SAE, as well as delineating their mechanistic contributions to modulating cytoplasmic escape of mtDNA.

Conclusion

In summary, this study has established a novel mitochondrial-based molecular signature, encompassing key genes such as ALDH7A1, HOGA1, and AA467197. By integrating bioinformatics analysis and machine learning approaches, we have delved into the interplay between these genes, immune infiltration, and mitochondrial metabolic functions. Additionally, our findings suggest that the levels of mtDNA in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid may serve as critical indicators of SAE progression, providing compelling evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress injury in SAE patients. These discoveries offer new insights into the pathogenesis of SAE and identify potential targets for future clinical interventions.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are available in the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are available in the GEO database ( [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/](https:/www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) ).

References

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315, 801 (2016).

Rengel, K. F., Hayhurst, C. J., Pandharipande, P. P. & Hughes, C. G. Long-term cognitive and functional impairments after critical illness. Anesth. Analgesia. 128, 772–780 (2019).

Helbing, D. L., Böhm, L. & Witte, O. W. Sepsis-associated encephalopathy. CMAJ 190, E1083–E1083 (2018).

Zhang, L. et al. Epidemiological features and risk factors of sepsis-associated encephalopathy in intensive care unit patients: 2008–2011. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 125, 828–831 (2012).

Schroeder, J. E., Weiss, Y. G. & Mosheiff, R. The current state in the evaluation and treatment of ARdS and SIRS. Injury 40 (Suppl 4), S82–89 (2009).

Gray, M. W. Mitochondrial evolution. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 4, a011403 (2012).

Picard, M. Blood mitochondrial DNA copy number: What are we counting? Mitochondrion 60, 1–11 (2021).

Xiang, M. & Fan, J. Pattern recognition receptor-dependent mechanisms of acute lung injury. Mol. Med. 16, 69–82 (2010).

Guo, H., Callaway, J. B. & Ting, J. P. Y. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of action, role in disease, and therapeutics. Nat. Med. 21, 677–687 (2015).

Andersson, J., Libby, P. & Hansson, G. K. Adaptive immunity and atherosclerosis. Clin. Immunol. 134, 33–46 (2010).

Bozza, F. A. et al. Sepsis-associated encephalopathy: A magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 30, 440–448 (2010).

Arulkumaran, N. et al. Mitochondrial Function Sepsis Shock 45, 271–281 (2016).

Yu, H. et al. Screening mitochondria-related biomarkers in skin and plasma of atopic dermatitis patients by bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Front Immunol 15, (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Mitochondria-Targeted peptide reverses mitochondrial dysfunction and cognitive deficits in Sepsis-Associated encephalopathy. Mol. Neurobiol. 52, 783–791 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. Circulating mitochondrial damps cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 464, 104–107 (2010).

Lowes, H., Pyle, A., Santibanez-Koref, M. & Hudson, G. Circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA levels in parkinson’s disease are influenced by treatment. Mol Neurodegeneration 15, (2020).

Ware, S. A. et al. An automated, high-throughput methodology optimized for quantitative cell-free mitochondrial and nuclear DNA isolation from plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 15677–15691 (2020).

Sjövall, F., Morota, S., Persson, J., Hansson, M. J. & Elmér, E. Patients with sepsis exhibit increased mitochondrial respiratory capacity in peripheral blood immune cells. Crit Care 17, (2013).

Barrett, T. et al. NCBI GEO: Archive for functional genomics data sets—update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D991–D995 (2012).

Lu, S. et al. A transient brain endothelial translatome response to endotoxin is associated with mild cognitive changes post-shock in young mice. Neuroscience 555, 194–204 (2024).

Juss, J. et al. Genome-wide transcription profiling in neutrophils in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet 385, S55 (2015).

Chung, H. Y. et al. Microglia mediate neurocognitive deficits by eliminating C1q-tagged synapses in sepsis-associated encephalopathy. Sci. Adv. 9, eabq7806 (2023).

Arneson, D. et al. Single cell molecular alterations reveal target cells and pathways of concussive brain injury. Nat Commun 9, (2018).

Hao, Y. et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 293–304 (2024).

Hu, C. et al. CellMarker 2.0: An updated database of manually curated cell markers in human/mouse and web tools based on scRNA-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D870–D876 (2023).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, (2014).

Rath, S. et al. MitoCarta3.0: an updated mitochondrial proteome now with sub-organelle localization and pathway annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D1541–D1547 (2021).

Kanehisa, M. K. E. G. G. Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Wu, T. et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innov. 2, 100141 (2021).

Carlson, M. org.Hs.eg.db. Bioconductor https://doi.org/10.18129/B9 (2017). BIOC.ORG.HS.EG.DB.

Wilkerson, M. D. & Hayes, D. N. ConsensusClusterPlus: A class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics 26, 1572–1573 (2010).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47–e47 (2015).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, (2008).

Meyer, D., Dimitriadou, E., Hornik, K., Weingessel, A. & Leisch, F. e1071: Misc functions of the department of statistics, probability theory group (Formerly: E1071), TU Wien. R Foundation. https://doi.org/10.32614/cran.package.e1071 (1999).

Kuhn, M. Building predictive models inRUsing thecaretpackage. J Stat. Soft 28, (2008).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer international publishing, 2016).

Harrell, F. E. Jr & rms Regression Modeling Strategies. The R Foundation https://doi.org/ (2009). https://doi.org/10.32614/cran.package.rms.

Robin, X. et al. pROC: An open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics 12, (2011).

Keilwagen, J., Grosse, I. & Grau, J. Area under Precision-Recall curves for weighted and unweighted data. PLoS ONE. 9, e92209 (2014).

Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32, 2847–2849 (2016).

Wang, R. H. & Thakar, J. Comparative analysis of single-cell pathway scoring methods and a novel approach. NAR Genomics Bioinformatics 6, (2024).

Timmermans, K. et al. Plasma levels of danger-associated molecular patterns are associated with immune suppression in trauma patients. Intensive Care Med. 42, 551–561 (2016).

Jin, S. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using cellchat. Nat Commun 12, (2021).

Jin, S., Plikus, M. V. & Nie, Q. CellChat for systematic analysis of cell–cell communication from single-cell transcriptomics. Nat. Protoc. 20, 180–219 (2025).

Kafa, I. M., Bakirci, S., Uysal, M. & Kurt, M. A. Alterations in the brain electrical activity in a rat model of sepsis-associated encephalopathy. Brain Res. 1354, 217–226 (2010).

Taccone, F. S. et al. Sepsis is associated with altered cerebral microcirculation and tissue hypoxia in experimental peritonitis**. Crit. Care Med. 42, e114–e122 (2014).

Van Wyngene, L., Vandewalle, J. & Libert, C. Reprogramming of basic metabolic pathways in microbial sepsis: Therapeutic targets at last? EMBO Mol. Med 10, (2018).

Haileselassie, B. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction mediated through dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) propagates impairment in blood brain barrier in septic encephalopathy. J Neuroinflammation 17, (2020).

Berg, R. M., Møller, K. & Bailey, D. M. Neuro-oxidative-nitrosative stress in sepsis. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 31, 1532–1544 (2011).

Liu, L. et al. Inhalation of hydrogen gas attenuates brain injury in mice with cecal ligation and puncture via inhibiting neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis. Brain Res. 1589, 78–92 (2014).

Marik, P. E. & Raghavan, M. Stress-hyperglycemia, insulin and Immunomodulation in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 30, 748–756 (2004).

Ding, H. et al. Fisetin ameliorates cognitive impairment by activating mitophagy and suppressing neuroinflammation in rats with sepsis-associated encephalopathy. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 28, 247–258 (2022).

Xu, X. et al. Caspase-1 inhibitor exerts brain-protective effects against sepsis-associated encephalopathy and cognitive impairments in a mouse model of sepsis. Brain. Behav. Immun. 80, 859–870 (2019).

Cui, Y. et al. High concentration hydrogen protects Sepsis-Associated encephalopathy by enhancing Pink1/Parkin‐Mediated mitophagy and inhibiting cGAS‐STING‐IRF3 pathway. CNS Neurosci. Ther 31, (2025).

Schwalm, M. T. et al. Acute brain inflammation and oxidative damage are related to Long-Term cognitive deficits and markers of neurodegeneration in Sepsis-Survivor rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 49, 380–385 (2014).

Goldim, M. P. et al. Oxidative stress in the choroid plexus contributes to blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier disruption during sepsis development. Microvasc. Res. 123, 19–24 (2019).

Kim, M. et al. Genetic association-based functional analysis detects HOGA1 as a potential gene involved in fat accumulation. Front Genet 13, (2022).

Tong, Y. et al. Proteogenomic insights into the biology and treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Hematol. Oncol 15, (2022).

Wang, C. et al. HOGA1 suppresses renal cell carcinoma growth via inhibiting the Wnt/β-Catenin signalling pathway. J Cell. Mol. Medi 29, (2025).

Johal, A. S. et al. Restricting lysine normalizes toxic catabolites associated with ALDH7A1 deficiency in cells and mice. Cell. Rep. 43, 115069 (2024).

Yang, J. S. et al. ALDH7A1 inhibits the intracellular transport pathways during hypoxia and starvation to promote cellular energy homeostasis. Nat Commun 10, (2019).

Yang, J. S. et al. ALDH7A1 protects against ferroptosis by generating membrane NADH and regulating FSP1. Cell 188, 2569–2585.e20 (2025).

Clark, M. L. et al. Mitochondrial complex IV remodeling in tumor-associated macrophages amplifies interferon signaling and promotes anti-tumor immunity. Immunity 58, 1670–1687e12 (2025).

Liu, Q., Li, W., Qian, Y., Wang, C. & Xia, P. AA467197 controls the hyperactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome during infection. TIL 1, 100012 (2023).

Harrington, J. S. et al. Circulating mitochondrial DNA as predictor of mortality in critically ill patients. Chest 156, 1120–1136 (2019).

Van Der Slikke, E. C. et al. Association between oxidized nucleobases and mitochondrial DNA damage with long-term mortality in patients with sepsis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 179, 156–163 (2022).

Dimasuay, K. G., Berg, B., Schaunaman, N. & Chu, H. W. Role of myeloid Cell-Specific TLR9 in mitochondrial DNA-Induced lung inflammation in mice. IJMS 24, 939 (2023).

Gingis-Velitski, S., Zetser, A., Flugelman, M. Y., Vlodavsky, I. & Ilan, N. Heparanase induces endothelial cell migration via protein kinase b/akt activation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23536–23541 (2004).

Marchetti, D., Li, J. & Shen, R. Astrocytes contribute to the brain-metastatic specificity of melanoma cells by producing heparanase. Cancer Res. 60, 4767–4770 (2000).

O’Callaghan, P., Zhang, X. & Li, J. P. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans as relays of neuroinflammation. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 66, 305–319 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82060345).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was collaboratively conceived and designed by all authors. Z.Z. Zhang and X.L. Qiu led the conceptualization and developed experimental protocols, including the design and validation of mouse model experiments. Z.Z. Zhang and X. L. Qiu performed the experiments, analyzed data, and interpreted results to validate findings. J.L. Lu, C.X. Xu, and X. Zeng conducted comprehensive literature reviews, synthesized background information, and performed systematic data analysis to ensure contextual and methodological accuracy. J. Huang provided critical clinical insights and contributed to study design discussions. C.Q. Zhao offered biological mechanism interpretations and supported result validation. Y. Zhan supervised the research, performed final manuscript revisions, and ensured scholarly rigor and logical coherence. All authors participated in extensive discussions of the findings and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent for publication

The animal experiments were authorized by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanchang University. This study was carried out in compliance with local laws and institutional guidelines. This study was reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Qiu, X., Zeng, X. et al. Integrated multi omics and machine learning reveal mitochondrial immunometabolic networks in sepsis associated encephalopathy. Sci Rep 15, 33572 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18650-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18650-2