Abstract

This work reports the development of a sustainable Al7075 metal matrix composite reinforced with bio-derived activated carbon (AC) obtained from rice hull agricultural waste. Unlike conventional reinforcements such as SiC and Al₂O₃, rice hull-derived AC provides an eco-friendly, lightweight, and cost-effective alternative. The composites were fabricated using ultrasonic stir casting with varying AC contents (2–8 wt%). Microstructural characterization (OM, FESEM-EDS, and XRD) confirmed uniform dispersion of AC and the absence of detrimental Al₄C₃ formation. Mechanical testing revealed that 2 wt% AC yielded the optimum properties, improving hardness (by 21%) and tensile strength (by 23%) compared to unreinforced Al7075. Abrasive wear studies showed enhanced wear resistance and reduced coefficient of friction at the same reinforcement level. Beyond mechanical and tribological assessment, this work introduces a predictive framework using machine learning models (Gradient Boosted Trees, Gaussian Process Regression), which achieved near-perfect accuracy (R² > 0.99 for wear, R² > 0.96 for COF). These findings establish rice hull–derived activated carbon as a viable reinforcement for Al7075 composites and highlight the potential of data-driven approaches in predicting tribological performance, thereby advancing sustainable and intelligent material design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing demand for innovative materials for demanding engineering applications has led to a significant surge in research and development of metallic composites. Among all the metal matrix composites, Al7075 is frequently used in automotive, aerospace, mechanical, and marine industries due to its high strength-to-weight ratio, high tensile strength1,2, high yield strength3, and high elongation4 during the moment of failure. Al7075 alloy is a widely preferred material for many applications in industries. Nevertheless, it has significant drawbacks as well, such as complex welding procedures and high reactivity with oxygen5, high reactivity with water, low tribological resistance6,7 and rapid corrosion by acids8. Powder Metallurgy or stir casting are customary methods to create aluminium matrix composites9,10,11,12. The process evenly distributes particles before the casting using a mechanical stirrer13. The study was carried out on an aluminium matrix supplemented with varying concentrations of silicon carbide (SiC), which is commercially available and very densely made using stir-casting method14. Industrial and agricultural operations produce much waste. The fact that agricultural wastes like fly ash, bagasse, bamboo, rice hulls, coconut shells, and so on are used as reinforcement is heartening. Most waste produced by natural sources is burnt to ashes and creates environmental pollution15. Utilizing natural waste materials can ultimately lower costs and significantly improve the strength-to-weight ratio. Meanwhile, the mechanical and tribological properties of metals/alloys were found to improve from using rice hull. There are many other sources, but rice hull contains a good amount of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Researchers created a capacitor using AC, rice husk, beetroot, and silica impregnation with an optimal specific capacitance of 116 F/g16. In addition to cadmium and copper, the AC made from rice hull and fly ash can adsorb heavy metals such as iron, lead, and nickel, with a 20–60 mg/l capacity17. According to a study, even with a smaller surface area and pore volume than carbon fibre, AC made from rice hulls had a higher adsorption capacity18. This resulted from the rice hull’s higher ash content and higher concentrations of carbon and oxygen atoms. Nitrogen, an inert medium, is frequently employed to activate carbon at elevated temperatures between 600 and 900 °C19,20,21.

P. Saini et al.22 fabricated an Al4043 + SiC composite using the bottom stirring cast technique and analysed its morphological and mechanical properties. They achieved homogeneous dispersion of particles up to 6 wt% SiC but observed agglomeration beyond this point. SiC particles (up to 6 wt%) enhanced the UTS and microhardness of the aluminium matrix composite (AMC). However, at an 8 wt% fraction, these characteristics declined due to particle aggregation and poor interfacial bonding.

Venkataraman et al.23 carried out a study on titanium carbide-reinforced Al 7075 matrix composites which revealed that the wear behaviour of alloys is influenced by titanium carbide content in the microstructure and the applied load. At a lower load, an increase in titanium carbide content decreased the wear rate of the alloy. However, at higher loads of 26.7 and 35.6 N the spray-deposited Al7075 alloy exhibited superior wear resistance compared to Al7075/TiC composites.

Harish et al.24 studied the microstructure and mechanical properties of aluminium matrix composites and found that the addition of fly ash reinforcement significantly improved the composite’s strength.

Many studies have been found on the AI7075-based composite; however, research on activated carbon-mixed AI7075 metal matrix composites and their microstructural, mechanical, and abrasive wear characteristics from the perspective of different activated carbon contents is limited. In this work, metal matrix composites are prepared by reinforcing Al7075 with activated carbon obtained from rice hulls at different weight fractions. These composites are tested for their microstructural, mechanical, and abrasive wear characteristics, which are crucial for suggesting potential applications for these new materials.

It has been noticed that many authors used the waste material as reinforcement to fabricate the composite material and only a few of the researchers used the activated carbon which is obtained from the waste material like rice hull. Therefore, an effort has been made to reinforce various weight fraction of activated carbon (AC) as reinforcement. This work is executed in two steps which includes, extraction of AC from rice hull waste instead of using commercial fillers, which are lighter in weight and density. The activated carbon is used as reinforcement with AA7075 to fabricate a sustainable metal matrix composite.

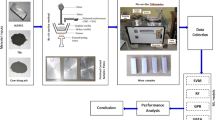

The present work is achieved in two phases. In the first phase, activated carbon was extracted from rice hulls by calcination process, producing a low-density and cost-effective reinforcement material. In the second phase, developed activated carbon was infused into aluminium matrix alloy using ultrasonic stir casting. XRD and FTIR analysis were used to characterize the extracted AC. A field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM), an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis, and elemental mapping were used to assess the material, this process also characterizes the substances (constituents) within the matrix, ensuring their optimal integration to enhance the composite’s properties. Thus, the current aim is to examine the mechanical and tribological properties of aluminium matrix composites that were made in part from bio-waste (rice hull) and to shed light on whether the composite is appropriate for load-bearing applications.

The incorporation of activated carbon as a reinforcement in Al7075 alloy composites presents a compelling strategy for improving mechanical, and tribological properties without compromising on lightweight characteristics. As a sustainable and economically viable material, activated carbon paves the way for greener composite technologies.

Materials and methods

Materials

The matrix material Al7075 alloy which has 2.81 g/cc density was purchased from Venuka Engineering Private Limited, Hyderabad, India. The Activated carbon (AC) is extracted using carburization method from the rice hull. The density of the extracted AC is 1.279 g/cc.

Extraction of activated carbon

Initially, rice hulls were collected from a rice mill and cleaned with water to remove dirt and debris. After cleaning, the rice hulls underwent a leaching process and were then soaked in 1 M HCl for 1 h. Following the acid treatment, the rice hulls were thoroughly washed with distilled water to remove any residual HCl. The washed rice hulls were dried in an oven for 24 h to eliminate moisture. Once moisture-free, the rice hulls were placed in a tubular furnace in an inert atmosphere at 800 °C for 2 h, with a ramping period of 1 h. The calcination process in the inert atmosphere resulted in the extraction of activated carbon, as shown in Fig. 1a.

After the calcination process, the resulting activated carbon was mixed with potassium bromide (KBr) to form a KBr film which acts as a window material. This mixture was then subjected to a hydraulic press to ensure proper formation and densification of the activated carbon film. The final activated carbon product, as shown in Fig. 1a, was obtained through this process.

As shown in Fig. 1b, the activated carbon derived from the rice hulls was confirmed for microstructural, chemical, and morphological analysis. Microstructural, compositional, and morphological aspects of the activated carbon were investigated in Fig. 1b using material characterization methods such Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). The EDS image revealed the presence of activated carbon with 78.05 wt% and an atomic % of 84.98.

Fabrication of Al7075 alloy with AC

A graphite crucible containing Al7075 alloy was filled and heated to 750 °C. To ensure proper melting of Al7075 alloy, the temperature was maintained between 750 °C and 800 °C for an hour. To reduce the quantity of gas present in the aluminium melt, a C2Cl6 degassing tablet was utilized. During molten liquid stirring, coarser grain-sized Mg particles acted as a flux to enhance the wettability of reinforcements. Employing ultrasonic stir casting technique, AC preheated below 500°c was mixed into the liquid and stirred for 20 min at a vertex formation speed of 350–400 rpm by a mechanical stirrer. An elevated melting point of 800 °C was maintained within the crucible to improve the followability of AC and ensure successful sonication. After sonication, Al7075 alloy was set into a graphite crucible and heated to 75 °C for 5 min to break up any agglomerations or clusters in AC reinforcement. The molten liquid was then transferred into a die-steel mould preheated to 500 °C. Over the following 24 h, the mould was allowed to cool down to room temperature spontaneously. Once the cylindrical workpieces were solidified, they were removed from the mould and machined per ASTM specifications for various testing purposes as shown in Fig. 2.

XRD of activated carbon (AC)

Extensive characterization was performed on the specimens produced using a powder X-ray diffractometer (Model: PANALYTICAL XPERT POWDER). The radiation source was CuKα, and the scanning angle was 20° to 60°. The parameters were modified with a step size of 0.02° and a duration of 50 s. These were added to measurement parameters to guarantee precise data capture. Figure 3 displays a XRD patterns of activated carbon at several intensities. A maximum intensity peak was recorded at 2θ = 22° at 550 °C. The comprehensive C (002) peak observed in untreated rice hulls is indicative of their amorphous nature. In contrast, the broad C(111) and C (200) diffraction angle at 2θ = (35° to 40°) and (40° to 50°) respectively detected in rice hulls treated with HCl suggests the presence of carbon in the form of graphite structure25.

FTIR of activated carbon (AC)

This study employed Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to analyse specimens with KBr as window material using a Bruker Alpha II spectrometer.

Due to stretching involving C-H bonds, the signal at 2923.0 cm− 1 suggests the presence of carboxylic acid26. Hemicelluloses are identified by the emergence of the aldehyde group (C = O) at around 1634 cm− 1, whereas lignin is determined by the presence of aromatic compounds at approximately 1500 cm− 1. As seen in Fig. 4, stretching vibration peaks are shown at 1455 cm− 1 caused by carboxylate groups, indicating the composites’ strength27,28.

Density and porosity of the composite

The following formula was used to determine theoretical density (ρt).

The Archimedes principal is used to find the experimental density. The distilled water is used as the buoyant fluid, and it was employed to determine the mole fractions (xi) and densities (ρi) of the specimen; applying Archimedes’ principle, the real density of the composite (ρexp) was determined. In addition, the following equation is used to determine the experimental density (ρexp) and porosity (ϕ) fraction of the composites.

At least three experiments under conditions produced the data used for several studies in the manuscript. The mean ± standard deviation was used to present the results.

Hardness

The hardness of the fabricated composites is evaluated using a Vickers micro-hardness tester according to the ASTM E92. During the test, a duration of 20 s and a consistent force of 1 kg was applied.

Tensile test

To develop a composite material, the fundamental characteristics of engineering materials and the calibre of materials used in the design and construction of mechanical testing are crucial. Testing the material under tension can reveal if it can handle a tensile load.

Following the ASTM E8 standards, the specimens’ tensile properties were determined using a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min and a strain rate of 2.3 × 10–4s–1. Three specimens of each composition, each measuring 25 mm in gauge length and 6 mm and a gauge width, were subjected to stress. Moreover, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was employed for surface morphological examination.

Tribological properties

In compliance with ASTM G99-09 standards, the prepared samples’ wear behaviour was investigated using a (TE-165-LE, Magnum Engineers, India) pin-on-disc tribometer with a disk material of EN32 steel of size, Ø165 mm and 8 mm thickness. The test specimens that were utilized to analyse the abrasive wear of the composite material were sliced into cylindrical pin samples measuring a length of 30 mm and diameter of 8 mm. Grit size grades of (180, 200 and 220 μm) abrasive paper served as the opposite surface. Three separate loads of (10, 15, and 20 N) were applied at a constant speed of 300 rpm for wear studies. The typical room temperature was used for the trials. Friction formula is used for wear coefficient calculation of the composite.

Results and discussions

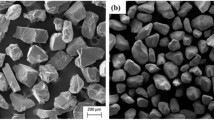

Optical microscopy

Optical microscopy was used to examine the microstructure. The samples were dry polished with emery papers of various grades 200, 400, 600, 800, 2000, and 4000. This was followed by cloth polishing with alumina. Finally, the samples were immersed in Keller’s etchant (a mixture of HCl, HF, HNO3, and Distilled water) for 5 to 7 s. Images were captured at a 200-µm scale of magnification 200X for both unreinforced and reinforced matrix. There were voids and coarse granules in the basic matrix as presented in Fig. 5a. Heavy tension may accumulate in the area around these voids as they have the potential to serve as stress concentrators. These voids could later serve as hubs for the start and propagation of cracks, which would eventually result in a loss of mechanical qualities.

The microstructure of the reinforced Al7075 with the activated carbon is presented in Fig. 5b under the same magnification as that considered for the unreinforced Al7075. Clear differences are observed between the unreinforced and reinforced Al7075. Proper grain formation and uniform reinforcement particle distribution were observed in Fig. 5b, Settlement of fine grains and reinforcement particles at grain boundaries was evident, which could be attributed to additional carbon reinforcement to enhance overall composite strength.

Due to the settlement of activated carbon particles at the boundaries, they are useful in two different aspects. First, these settled carbon particles impeded the dislocation movement, as these dislocations are defects within the crystal structure that move when the material is deformed. When the dislocations encounter these particles, the dislocations are pinned or blocked, and as a result, the resulting material becomes more difficult to deform. In another way, compared to grain interiors, grain boundaries are weaker regions, and the accumulation of activated carbon particles at the grain boundaries strengthens the boundary and enhances the load bearing capacity29,12.

FESEM of unreinforced and reinforced composite

The unreinforced Al7075 and reinforced Al7075 composites were analysed using FESEM along with EDS spectrum. The presence of reinforcement particles was confirmed using EDS element mapping. Figure 6a. shows the FESEM images of the samples in the selected area, as well as the EDS image and compositions of major elements of unreinforced Al7075 in Fig. 6b. Different colours indicate the presence of elements in EDS element mapping, as shown in Fig. 6c.

FESEM images of selected area is illustrated in Fig. 7a and some reinforcing particles settled at the grain boundaries, with activated carbon located grain boundaries. The EDS elemental composition reveals the presence of elements in the composite, with a majority of elements such as Zn, Mg and Cu present along with activated carbon as depicted in Fig. 7b. Furthermore, the complete bonding of activated carbon (AC) to Al7075 alloy matrix and the reinforcing particles’ homogeneous distribution could be seen in Fig. 7c.

From the EDS elemental composition, it is observed that the Al7075 cast alloy contains aluminum, copper, zinc, and manganese. These elements are used to enhance strength, hardness, and toughness, which is clear from Fig. 6.

However, with the addition of activated carbon, some more elements are presented in the Al7075-based composite as depicted in Fig. 7. In addition to the elements in the base alloy, it includes carbon from activated carbon and potentially magnesium. Carbon and magnesium enhance mechanical properties like wear resistance, strength, and hardness.

XRD of unreinforced and reinforced composite

The XRD of unreinforced composite is shown in Fig. 8a. The peaks in the Fig. 8a indicate the presence of crystalline aluminium, which is the primary phase in the alloy. The positions and intensities of these peaks correspond to the crystal planes of aluminium.

Figure 8b shows the XRD of 2% weight% activated carbon reinforced Al 7075 composite. This composite shows peaks corresponding to aluminium (Al) as well as presence of activated carbon (AC). Preventing the formation of aluminium carbide (Al4C3) in composites reinforced with activated carbon (AC) is challenging during preparation. Al4C3 is the most energetically favourable stoichiometry of Al4C3 and negatively impacts the mechanical properties of composites. The likelihood of its formation is highly dependent on the processing temperature, and it becomes inevitable when the fabrication temperature exceeds 500 °C29. Higher temperatures and increased density of defects on the AC surface facilitate the formation of Al4C3. XRD analysis of pure 7075 aluminium alloy and 2wt% composites reveal the absence of characteristic peaks of Al4C3 and other metallic carbides, this absence is attributed to low sintering temperature of about 400 °C as shown in Fig. 8b30,31. The ICDD Pdf card corresponding to the aluminium phase is ICDD PDF #00-04-0787. An Al4C3-free interface is established between the AC and metal matrix, which is advantageous for achieving superior performance in aluminium-activated carbon composites.

Density and porosity measurement

The actual density of the composites consistently falls below the theoretical density across all samples depicted in Fig. 9a. This deviation can be attributed to defects within the composite samples. The casting technique may have introduced trapped gas bubbles or voids, diminishing the overall density. Furthermore, these defects can disrupt atomic arrangements, resulting in local density fluctuations and contributing to general reduction in densities; the research findings were in line with earlier study32.

The density of activated carbon is significantly lower than that of the aluminum matrix. A greater volume is occupied when AC is introduced to the aluminum matrix at varying weight fractions. The greater volume causes the AC particles to gather together, creating agglomerates. Instead of being evenly scattered, the particles are more likely to come into contact with one another, which leads to this agglomeration. The composite may contain areas where the AC particles are not firmly bound to the matrix material due to their aggregation. The porosity occur as a result of these weakly connected areas33. The Archimedes principal has been used to calculate the density. The experimental density (ρexp) and porosity(ϕ) is calculated using the Eqs. 1, 2 and 3 respectively, the corresponding results are shown in Fig. 9a and b.

Hardness of composite

Analysis of Fig. 10 reveals an enhancement in the base material’s microhardness on the reinforcement’s introduction. At 2% weight fraction of activated carbon blended Al7075 composite, the Vickers hardness number increases from 72 HV (as-cast Al7075) to 89.6 HV, representing a 21.08% improvement over as unreinforced Al7075. This improvement may also be attributed to dynamic processes such as recovery and re-crystallization33,34. Similar outcomes were reported in the reinforcement of Al 7075 with various fillers35,36.

In contrast to the composite made with a 2% weight fraction of activated carbon infused composite, the hardness is reduced at other weight fractions like 4%, 6%, and 8%; however, in comparison to the base material (Al7075), the hardness is increased at all weight fractions of activated carbon mixed composite. However, a decline in mechanical properties was observed for 4%, 6% and 8% wt% of AC because of the presence of porosity. The interface bonding between the matrix and the reinforcement was not even, and that resulted in a lack of uniformity37.

Tensile test of composite

Figure 11 illustrates all fabricated composite specimens’ ultimate tensile strength (UTS). Notably, the UTS of Al7075 with activated carbon composite increased by 23.24% for a 2 wt% AC content, followed by a consistent reduction pattern for all other carbon percentages. This improvement is attributed to increased % of AC reinforcement, enhanced between the matrix and reinforcement interfacial bonding, and the strain gradient and grain size strengthening effect in the composites. The ultimate tensile strength rises at the remaining weight fraction when compared to unreinforced Al7075; however, the percentage of improvement decreases as the weight fraction of activated carbon increases.

The incorporation of activated carbon reinforcement in the Al7075 aluminum alloy matrix serves as a nucleation site, influencing the recrystallization process of the aluminum matrix. As these particles are settled at the grain boundary, which is evident from the SEM images presented in Fig. 5b, they are used to lock the movement of the grain boundaries, which reduces the elongation of the composite and makes the composite stronger and these findings are consistent with earlier reports41,45.

The ultimate tensile strength of Al7075 is reduced as the weight% of activated carbon is increased because of the agglomerations of this high-volume, low-density particles. Accumulation of the AC particles results from increasing the weight fraction of activated carbon, which also increases volume. Because of these agglomerations, the effective load distribution is restricted, which causes greater stresses to be concentrated and ultimately leads to failure at lower loads.

Fracture mode was predominant in the tensile fractography of Al7075 and AC, this is evident from features such as facets, cracks, voids, and inter-granular cracks along the fracture surface as illustrated in Fig. 12a. and the de-bonding observed represents the nature of the ductile fracture, as shown in Fig. 12b.

Wear behaviour

The impact of load and reinforcement on weight loss

By varying the load and AC (activated carbon) content in Al7075 matrix alloy, as shown in Fig. 13, the inclusion of AC particles significantly increased the wear resistance. Al7075–AC composite has lower wear rates than the alloy without reinforcement at all tested loads. The wear rate of Al7075 matrix alloy and its composites goes up with heavier loads. More significant loads lead to more plastic deformation, making more wear debris and higher wear rates. Also, there’s more cracking and material loss under heavy loads38.

At a track diameter of 80 mm, the wear rate is highest at 10 N load (0.00018 mm³/m) and was displayed by base metal, while the lowest wear rate at same load (0.000149 mm³/m) was exhibited by 2 wt% AC. When 2% activated carbon is added to the unreinforced Al7075, the wear resistance increases to 17.22%. These observations align with findings from previous research.

The reinforcement of activated carbon into Al7075 matrix generated the aluminium, magnesium and carbon which are evident from EDS elemental composition (Fig. 7). These elements used to increase the wear resistance and hardness39. The elevated hardness values of the composites with AC contribute to improved wear resistance in the specimens40,41.Maximum coefficient of friction COF was observed for Al7075 alloy (base material), and COF for Al7075/ 2 wt% AC exhibits low COF, as depicted in Fig. 14.

Figure 15a, there are minimal grooves but a significant amount of wear debris. The Al7075 alloy seems to have undergone peeling, with material transfer occurring during the wear process, where material from the aluminium alloy’s surface migrates to its counterpart. Additionally, some larger wear debris adhered to the counterpart due to insufficient milling time. In contrast, the counterpart surface of the Al7075/AC composite, depicted in Fig. 15b, appears smooth, with no substances adhering to it. This indicates a more stable wear process compared to the counterpart of Al7075 alloy42,43,44,45,46.

Comparative predictive analysis of wear rate and coefficient of friction using machine learning models

This analysis presents a comprehensive comparison of five machine learning models for predicting wear rate and coefficient of friction (COF) based on tribological testing data. The models evaluated include Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosted Trees (GBT), and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR).

The dataset used in this analysis consists of 27 experimental observations, each characterized by three input parameters and two response variables. The input parameters are load (ranging from 10 to 20 N), rotational speed (RPM, ranging from 300 to 500), and reinforcements percentage which varies from 2 to 6%. The two response variables measured are wear rate and coefficient of friction (COF). Wear rate values in the dataset range from approximately 0.000101 to 0.000782, indicating very fine measurements of material loss under different test conditions. The COF values span from 0.026 to 0.59, capturing a wide spectrum of frictional behaviour across the tested samples. The data covers various combinations of input parameters, providing a comprehensive basis for evaluating the predictive performance of machine learning models on tribological properties.

The methodology for this predictive analysis involved a systematic approach to both data collection and Modeling. Initially, tribological tests were conducted to generate a dataset consisting of 27 observations, each defined by three input parameters, load, rotational speed (RPM), and weight% of reinforcement and two response variables: wear rate and coefficient of friction (COF). The experimental matrix was designed to cover a range of values for each input, ensuring that the effects of varying load, speed, and additive content on wear and friction could be thoroughly assessed.

Following data acquisition, the dataset underwent preprocessing, which included integrity checks to confirm the absence of missing or anomalous values, normalization of input features using Min-Max scaling to standardize their ranges and splitting into training and testing subsets (80% training, 20% testing) with a fixed random state for reproducibility42. This step ensured that the models would be trained and evaluated on consistent data partitions.

Model development involved selecting five regression algorithms, ANN, SVR, RF, GBT, and GPR each Configured with carefully chosen hyperparameters to balance complexity and overfitting risk. The models were trained using the processed training data, with deterministic initialization to guarantee reproducibility. Performance evaluation was carried out using standard regression metrics: coefficient of determination (R²), mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), and root mean squared error (RMSE). These metrics provided a comprehensive assessment of each model’s predictive accuracy for both wear rate and COF47. Finally, the results were visualized using scatter plots comparing actual and predicted values, and performance tables were generated to facilitate direct comparison among the models. This rigorous methodology ensured a robust and transparent analysis of the predictive capabilities of various machine learning approaches for tribological property estimation. The methodology adopted to predict the wear and COF is shown in Fig. 16.

The training protocol for this predictive analysis was designed to ensure robust, reproducible, and fair evaluation of all machine learning models. The model development process incorporated; Consistent initialization is used in which Random state is 42 for all stochastic processes. For Parallel computation, utilized all CPU cores through n jobs is – 1 setting. And for the deterministic workflow, Sequential training without cross-validation is implemented due to small dataset size instead, the test set served as the basis for all performance evaluations. The model selection and configuration listed in Table 1. This protocol ensured that each model was trained under identical conditions, enabling a direct and reliable comparison of their predictive capabilities for both wear rate and coefficient of friction48.

Performance metrics comparison

The performance of each model was evaluated using four standard regression metrics as listed in Tables 2 and 3. The results clearly demonstrate significant differences in predictive capability across the models.

Analysis of model performance for wear rate prediction

The wear rate prediction results reveal a stark contrast between the traditional and advanced regression approaches. This performance gap can be attributed to the complex, nonlinear relationships in tribological data that certain algorithms are better equipped to model.

The High-Performing Models like GBT and GPR models achieved nearly identical, exceptional performance with R² values of 0.9997, indicating almost perfect prediction capability. These models demonstrated remarkably low error metrics with RMSE values of approximately 3.13 × 10–6, which is several orders of magnitude smaller than the actual wear rate values (which are in the 10⁻⁴ range). This extraordinary performance is likely due to the ability of both algorithms to capture complex nonlinear patterns in the data. GBT achieves this through sequential ensemble learning with decision trees, while GPR excels through its probabilistic approach to function approximation.

The Random Forest model also performed excellently with an R² of 0.9932 and RMSE of 1.48 × 10⁻⁵. Although slightly less accurate than GBT and GPR, RF still demonstrated robust predictive capability, leveraging the power of ensemble learning to model the wear rate with high precision.

While the Poor-Performing Models like The ANN and SVR models both failed dramatically at predicting wear rate, with negative R² values indicating performance worse than simply using the mean value as a predictor. The ANN produced extreme errors with an R² of – 25,969,918.18 and RMSE of 0.9167, which is several thousand times larger than the actual wear rate values. This catastrophic performance suggests that the neural network architecture (single hidden layer with 100 neurons) was inappropriate for this small dataset, Potential overfitting occurred during training and the learning process may have fallen into poor local minimum. The SVR model performed better than ANN but still poorly with an R² of – 1.5645. This suggests the chosen kernel and hyperparameters failed to capture the underlying relationships in the data.

Analysis of model performance for COF prediction

The COF prediction results show a similar pattern to the wear rate predictions, though with less extreme differences between the models.

The High-Performing Models like GBT and GPR again emerged as the top performers, both achieving an R² of 0.9646, demonstrating excellent predictive capability for COF values. Their nearly identical performance metrics (MAE of 0.0092 and RMSE of 0.0124) suggest they were equally effective at modeling friction coefficient relationships. These error values represent less than 5% of the average COF value, indicating highly reliable predictions.

The Random Forest model performed well with an R² of 0.8721, though not as exceptionally as for wear rate prediction. This slightly reduced performance may indicate that COF has more subtle nonlinear relationships that the random forest algorithm couldn’t fully capture.

While the Poor-Performing Models the ANN again performed catastrophically with an R² of – 463.3616, producing COF predictions that were entirely uncorrelated with actual values. The SVR also performed poorly with a negative R² of – 0.2919, though its errors were much smaller than the ANN’s.

If we do comparative analysis across response variables, then the consistent performance ranking across both wear rate and COF prediction (GBT/GPR > RF > SVR > ANN) suggests fundamental differences in model suitability for tribological data rather than response-specific issues. The exceptional performance of ensemble methods (GBT, RF) and GPR can be attributed to several factors like Ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships without requiring extensive hyperparameter tuning, Resilience to overfitting on small datasets through ensemble averaging (RF) or regularization (GBT), Natural handling of feature interactions, which are likely important in tribological systems where load, speed, and additive concentration may have interdependent effects. The poor performance of ANN and SVR highlights important limitations due to Neural networks typically require larger datasets to perform well and avoid overfitting, The single hidden layer architecture may have been insufficient for capturing the complexity of the tribological relationships and SVR’s performance is heavily dependent on kernel selection and hyperparameter tuning, which may have been suboptimal for this application.

Inspection of predictions

Examining the actual predictions provides additional insight into model performance differences: For one test sample with an actual wear rate of 0.000102, the predictive performance of different models varied significantly. The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) predicted a wear rate of 1.2750, which is approximately 12,500 times larger than the actual value, indicating a substantial overestimation. The Support Vector Regression (SVR) model predicted 0.0004415, about 4.3 times higher than the actual wear rate. The Random Forest (RF) model yielded a prediction of 0.000111, which is only 1.09 times larger than the actual value. Both the GBT and GPR models produced predictions of 0.0001025, which are almost identical to the actual wear rate (only 1.005 times larger). This example clearly illustrates the significant differences in precision among the models, with GBT and GPR achieving nearly exact predictions.

Similarly, for a test sample with an actual coefficient of friction (COF) of 0.32, the ANN model produced a completely erroneous negative value of -1.3254. The SVR model predicted a COF of 0.4470, corresponding to a 39.7% error. The RF model provided a prediction of 0.3045, resulting in a 4.8% error. Both the GBT and GPR models predicted a COF of 0.3250, which is only 1.6% higher than the actual value. These results further highlight the superior predictive accuracy of the GBT and GPR models compared to the others.

These predictions further highlight the superior accuracy of GBT and GPR models for both response variables from Figs. 17 and 18.

Conclusions

The present study successfully demonstrates the fabrication and evaluation of Al7075/activated carbon composites with dual objectives: (i) to assess the influence of bio-derived AC on mechanical and tribological properties, and (ii) to establish predictive modeling of wear and friction using machine learning. The main conclusions are:

-

Activated carbon derived from rice hulls was effectively utilized as a reinforcement, offering an eco-friendly and lightweight alternative to conventional ceramic fillers.

-

Optical and FESEM analyses confirmed uniform dispersion of AC, while XRD confirmed the absence of Al4C3, ensuring stable reinforcement–matrix interfaces.

-

At 2 wt% AC, the composites exhibited the highest improvement, with tensile strength increased by 23% and microhardness by 21% compared to unreinforced Al7075. Higher AC content (4–8 wt%) led to reduced properties due to agglomeration and porosity.

-

The 2 wt% AC composites achieved the lowest wear rate and coefficient of friction, attributed to increased hardness, effective grain boundary pinning, and stable counter-surface interaction.

-

Among machine learning models tested, Gradient Boosted Trees and Gaussian Process Regression achieved excellent predictive accuracy (R² > 0.99 for wear rate; R² > 0.96 for COF), validating the applicability of data-driven methods in tribology.

-

The synergy of sustainability (bio-waste utilization), improved mechanical/tribological properties, and reliable predictive modeling makes Al7075/AC composites promising for aerospace and automotive components requiring lightweight and wear resistance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Peng, W. et al. November., Effects of different initial states on dynamic tensile properties and microstructure of 7075 aluminum alloy, Mater. Sci. Eng.: A. 891, 2024 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2023.145939

Banoth, S., Suresh Babu, V., Raghavendra, G. & Hari Shankar, P. Study of various types of aluminium alloy grade series and their effect on mechanical performance, Mater. Today: Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.04.635 (2023).

Ammisetti, D. K. & Kruthiventi, S. S. H. Experimental investigation of the influence of various wear parameters on the tribological characteristics of AZ91 hybrid composites and their machine learning modeling. J. Tribol. 146 (5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4064020 (2024).

Kumaraswamy, J., Anil, K. C., Canbay, C. A. & Shivakumar, N. D. Electro-Whirling stir casting: a novel approach for fabricating Al7075/SiC MMCs with enhanced thermal characteristics. Silicon 16 (1), 295–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-023-02678-y (2024).

Mohanty, S. et al. Advanced surface engineering approaches for exotic applications. No 2 Korean Soc. Precision Eng. 25 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-023-00870-z (2024).

Lakkannavar, V., Yogesha, K. B., Prasad, C. D., Mruthunjaya, M. & Suresh, R. A review on tribological and corrosion behaviour of thermal spray coatings. J. Institution Eng. (India): Ser. D. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40033-024-00636-5 (2024).

Banoth, S., Hari Shankar, P., Suresh Babu, V. & Raghavendra, G. Tribological characteristics of aluminium alloy composites manufactured by liquid state casting process—a review, Mater. Today: Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.04.569 (2023).

Karthikraja, M., Ramanathan, K., Loganathan, K. T. & Selvaraj, S. Corrosion behaviour of SiC and Al2O3 reinforced al 7075 hybrid aluminium matrix composites by weight loss and electrochemical methods. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 100 (5), 101002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jics.2023.101002 (2023).

Harrigan, W. C. Commercial processing of metal matrix composites. Mater. Sci. Engi.: A. 244 (1), 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0921-5093(97)00828-9 (1998).

Ramesh, C. S., Keshavamurthy, R., Channabasappa, B. H. & Pramod, S. Friction and wear behavior of Ni-P coated Si3N4 reinforced Al6061 composites. Tribol. Int. 43 (3), 623–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2009.09.011 (2010).

Tjong, S. C. & Tam, K. F. Mechanical and thermal expansion behavior of hipped aluminum-TiB 2 composites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 97 (1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2005.07.075 (2006).

Akhlaghi, F., Lajevardi, A. & Maghanaki, H. M. Effects of casting temperature on the microstructure and wear resistance of compocast A356/SiCp composites: a comparison between SS and SL routes. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 155–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2004.04.328 (2004).

Rosso, M. Ceramic and metal matrix composites: routes and properties. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 175, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2005.04.038 (2006).

Reihani, S. M. S. Processing of squeeze cast Al6061-30vol% SiC composites and their characterization. Mater. Des. 27 (3), 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2004.10.016 (2006).

Saravanan, S. D. & Kumar, M. S. Effect of mechanical properties on rice husk Ash reinforced aluminum alloy (AlSi10Mg) matrix composites. Procedia Eng. 64, 1505–1513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2013.09.232 (2013).

Estrada-Guel, I. et al. Graphite nanoparticle dispersion in 7075 aluminum alloy by means of mechanical alloying. J. Alloys Compd. 483, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.07.190 (2009).

Rahman, M. H. & Al Rashed, H. M. M. Characterization of silicon carbide reinforced aluminum matrix composites. Procedia Eng. 90, 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2014.11.821 (2014).

Kumagai, S., Sato, M. & Tashima, D. Electrical double-layer capacitance of micro- and mesoporous activated carbon prepared from rice husk and beet sugar. Electrochim. Acta. 114, 617–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2013.10.060 (2013).

Hegazi, H. A. Removal of heavy metals from wastewater using agricultural and industrial wastes as adsorbents. HBRC J. 9 (3), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbrcj.2013.08.004 (2013).

Kumagai, S., Shimizu, Y., Toida, Y. & Enda, Y. Removal of Dibenzothiophenes in kerosene by adsorption on rice husk activated carbon. Fuel 88 (10), 1975–1982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2009.03.016 (2009).

Ahmedna, M., Marshall, W. E. & Rao, R. M. Surface properties of granular activated carbons from agricultural by-products and their effects on raw sugar decolorization. Bioresour. Technol. 71 (2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(99)90069-X (2000).

Saini, P. & Singh, P. K. Fabrication and characterization of SiC-reinforced Al-4032 metal matrix composites. Eng. Res. Express. 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-8695/ac4831 (2022).

Ganesh, I. & Advanced, I. Correlation between the characteristics of the mechanically mixed layer and wear behaviour of aluminium, Al-7075 alloy and Al-MMCs and wear behaviour of aluminium, Al-7075 alloy and Al-MMCs, Wear. 245(July), 22–38 (2016).

Bhowmik, A. et al. Analysis of physical, mechanical and tribological behavior of Al7075-fly Ash composite for lightweight applications. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-023-01583-3 (2023).

Ahmad, A. L., Loh, M. M. & Aziz, J. A. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from oil palm wood and its evaluation on methylene blue adsorption. Dyes Pigm. 75 (2), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dyepig.2006.05.034 (2007).

Lin, L. et al. Dye adsorption of mesoporous activated carbons produced from NaOH-pretreated rice husks. Bioresour. Technol. 136, 437–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.048 (2013).

Ojha, S., Pranay, V., Raghavendra, G. & Gara, D. Experimental evaluation and comparison of silica/biocarbon particulate-epoxy composites for high-strength applications. Proc. Inst. Mech. Engineers Part L: J. Mater.: Design Appl. 236(1), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/14644207211043506 (2022).

Rosa, S. M. L., Rehman, N., De Miranda, M. I. G., Nachtigall, S. M. B. & Bica, C. I. D. Chlorine-free extraction of cellulose from rice husk and whisker isolation. Carbohydr. Polym. 87 (2), 1131–1138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.08.084 (2012).

Bartolucci, S. F. et al. Graphene-aluminum nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Engineering: A. 528 (27), 7933–7937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2011.07.043 (2011).

Pérez-Bustamante, R., Bolaños-Morales, D., Bonilla-Martínez, J., Estrada-Guel, I. & Martínez-Sánchez, R. Microstructural and hardness behavior of graphene-nanoplatelets/aluminum composites synthesized by mechanical alloying. J. Alloys Compd. 615, S578–S582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.01.225 (2015).

Deng, C. F., Wang, D. Z., Zhang, X. X. & Li, A. B. Processing and properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced aluminum composites. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A. 444, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2006.08.057 (2007).

Xue, Y., Kelkar, A. & Bai, X. Catalytic co-pyrolysis of biomass and polyethylene in a tandem micropyrolyzer. Fuel 166, 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2015.10.125 (2015).

Yadav, R., Meena, A., Lee, S. Y. & Park, S. J. Experimental tribological and mechanical behavior of aluminium alloy 6061 composites incorporated ceramic particulates using Taguchi analysis. Tribol. Int. 192, 109243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2023.109243 (2024).

Singh, N. K. & Sethuraman, B. Development and characterization of aluminium AA7075 hybrid composite foams (AHCFs) using SiC and TiB2 reinforcement. Int. J. Metalcast. 18 (1), 212–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40962-023-01009-6 (2024).

Chowdary, M. S., Raghavendra, G., Kumar, M. S. R. N., Ojha, S. & Boggarapu, V. Influence of Nano-Silica on enhancing the mechanical properties of sisal/kevlar fiber reinforced polyester hybrid composites. Silicon https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-020-00846-y (2020).

Mohanakumara, K. C., Rajashekar, H., Ghanaraja, S. & Ajitprasad, S. L. Development and mechanical properties of SiC reinforced cast and extruded al based metal matrix composite. Procedia Mater. Sci. 5, 934–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mspro.2014.07.381 (2014).

Butola, R., Ranganath, M. S. & Murtaza, Q. Fabrication and optimization of AA7075 matrix surface composites using Taguchi technique via friction stir processing (FSP). Eng. Res. Express. 1 (2). https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-8695/ab4b00 (2019).

Bharat, N. & Bose, P. S. C. Microstructure, texture, and mechanical properties analysis of novel AA7178/SiC nanocomposites. Ceram. Int. 49 (12), 20637–20650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.03.195 (2023).

Sudarshan & Surappa, M. K. Dry sliding wear of fly ash particle reinforced A356 al composites. Wear 265, 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2007.11.009 (2008).

Ramesh, C. S., Bharathesh, T. P., Verma, S. M. & Keshavamurthy, R. Sand abrasive wear behavior of hot forged al 6061-TiO2 composites. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 21 (1), 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-010-9803-1 (2012).

Kaushik, N. C. & Rao, R. N. The effect of wear parameters and heat treatment on two body abrasive wear of Al-SiC-Gr hybrid composites. Tribol. Int. 96, 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2015.12.045 (2016).

Shah, R. et al. Machine learning in wear prediction. J. Tribol. 147 (4), 040801 (2025).

Kumar, P. & Kumar, B. Effect of T6 heat treatment on mechanical and tribological properties of fabricated AA7075/ZrB2/fly ash hybrid aluminum metal matrix composite by ultrasonic-assisted stir casting enroute. Inter Metalcast. 18, 2396–2414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40962-023-01177-5 (2024).

Verma, A., Baurai, K., Sanjay, M. R. & Siengchin, S. Mechanical, microstructural, and thermal characterization insights of pyrolyzed carbon black from waste tires reinforced epoxy nanocomposites for coating application. Polym. Compos., 41(1), pp.338–349, https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.25373

Kumar, P. & Kumar, B. Synergistic approach to tribological characterization of hybrid aluminum metal matrix composites with ZrB2 and fly ash: experimental and predictive insights. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part. E: J. Process. Mech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089241255931 (2024).

Verma, A., Negi, P. & Singh, V. K. Experimental analysis on carbon residuum transformed epoxy resin: chicken feather fiber hybrid composite. Polym. Compos., 40(7), 2690–2699. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.25067

Nguyen, Q. H. et al. Influence of data splitting on performance of machine learning models in prediction of shear strength of soil. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021 (1), 4832864 (2021).

Hasan, M. S., Wong, T., Rohatgi, P. K. & Nosonovsky, M. Analysis of the friction and wear of graphene reinforced aluminum metal matrix composites using machine learning models. Tribol. Int. 170, 107527 (2022).

Funding

There is no funding received for carrying out this project work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing, Original draft, Review and Editing, Data Curation; S.B.V.: Review and Editing, Data Curation, R.G.: Review and Editing, Data Curation; P.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Review and Editing; S.P.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Review and Editing; P.A.: Review and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Banoth, S., Valasingam, S.B., Gujjala, R. et al. Mechanical performance and predictive tribological modeling of Al7075 composites reinforced with rice hull activated carbon. Sci Rep 15, 35421 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18747-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18747-8