Abstract

This study examined the predictive performance of cardiovascular disease (CVD)-specific mortality using traditional statistical and machine learning models with non-invasive indicators, and assessed whether adding blood lipid profiles improves prediction. Data were from 1,749,444 Korean adults (44.7% female) from the Korea Medical Institute. Non-invasive predictors included sex, age, waist-to-height ratio, diabetes, hypertension, and physical activity; invasive variables included triglycerides, fasting glucose, and cholesterol. CVD-specific mortality was tracked over a 10-year follow-up. We applied Cox proportional hazards models (with and without elastic net penalty), Random Survival Forest, Gradient Boosting Survival, and Survival Tree models. Predictive performance was compared using area under the curve (AUC), c-index, and Brier score. All models using only non-invasive predictors achieved AUCs > 0.800 and were not inferior to models including blood profiles. Machine learning models showed slightly higher predictive performance over time than traditional models, but differences were not substantial. Both approaches appear valid for predicting CVD-specific mortality using non-invasive data. Machine learning models may offer marginally improved prediction, and the addition of invasive variables may not substantially enhance model performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) stands as the leading global cause of mortality, contributing to 32% of all deaths1. In Korea, CVD-specific mortality ranks as the second leading cause of death2. Fatalities stemming from CVD often manifest abruptly, with cardiac arrest frequently preceding demise, and frequently occur without preceding prognostic indicators or discernible symptoms3,4,5. Consequently, averting cardiovascular-related deaths constitutes paramount importance, prompting the development of risk assessment models aimed at the prediction and mitigation of CVD.

There have been well-established CVD risk prediction models, including the Framingham Risk Score model developed in the United States6,7 and the SCORE Project developed in Europe8. These prediction models serve as web-based tools to aid clinicians in decision-making regarding CVD risk management in primary medical institutions and are valuable in personal healthcare9. However, the application of the Framingham Risk Score model may lead to an overestimation of risk in Koreans10, and to date, there is no established CVD or CVD mortality prediction model specifically tailored for the Korean population. Furthermore, foreign prediction models may exhibit racial and/or cultural disparities7,8,10,11; therefore, it could be challenging to apply and generalize to the Korean population.

Currently, in Korea, there are CVD prediction services offered by the Korean National Health Insurance Service and national health examination CVD risk assessment models4,12. However, the predictive performance of these models utilizing age, blood pressure, blood indicators, diabetes, and smoking may not be sufficiently accurate for CVD prediction services4. Additionally, there is a lack of long-term follow-up data representing Koreans for future health risk assessment purposes12.

To address the limitations of current CVD prediction models, numerous studies have examined model validation for predicting CVD using both traditional statistical methods6,7,8,9,10,11,12 and the increasingly popular machine learning techniques13. However, research on models specifically predicting mortality from CVD remains inadequate, with no studies comparing the predictive efficacy of traditional statistical approaches to newer machine learning methods in developing such models. Therefore, this study seeks to fill this gap by leveraging long-term large cohort data representative of Koreans to develop a predictive model capable of easily and accurately self-assessing the risk of death from CVD.

The objective of this study was to assess and contrast the predictive abilities for CVD mortality of conventional statistical techniques and machine learning analyses, encompassing both modifiable and non-invasive factors, such as physical activity and anthropometric indicators. These variables, straightforward to measure and closely linked to lifestyle, are incorporated as predictive factors in the model for predicting mortality from CVD. Furthermore, our study examined the predictive ability of the traditional statistical approach, which relies solely on non-invasive variables, in comparison to the machine learning statistical method when additional invasive variables (e.g., blood indicators) are integrated into the predictive model.

Results

Participants characteristics

Table 1 presents an overview of the general characteristics of both deceased and surviving participants from CVD. Participants who died from CVD were generally older and had more unfavorable cardiometabolic profiles, including higher blood pressure, glucose, triglycerides, and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. They also had lower physical activity levels, particularly in walking and overall activity. Body mass index did not differ significantly in men but was higher in women with CVD events. Among the total participants, 1,791 participants died from CVD, with 1,357 being male and 434 females, indicating a higher mortality rate among men compared to women (Supplemental Table 1; P < 0.001). Diabetes, and hypertension had a higher prevalence in men than in women (P < 0.001). The results of the CVD prediction model utilizing traditional statistical methods are presented in Supplemental Table 2. Across all participants, an increase in WHtR corresponds to an elevated risk of CVD mortality, with the risk ratio increasing significantly in the presence of hypertension, and diabetes (all P < 0.001).

Predictive performance using non-invasive variables only

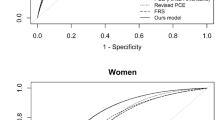

The predictive performance of the both traditional statistical methods and machine learning approach models in the Validation Set, specifically including non-invasive variables is presented in Fig. 1. To evaluate the time-dependent ROC-AUC, the mean ROC-AUCs of the Cox proportional hazards model and with elastic net penalty were 0.829 (95% CI: 0.811–0.847) and 0.806 (95% CI: 0.786–0.832) across all participants. The mean ROC-AUCs of Survival Tree, RSF, and GBS were 0.820 (95% CI: 0.803–0.840), 0.836 (95% CI: 0.813–0.856), and 0.837 (0.819–0.853) across all participants, respectively.

Prediction performance of cardiovascular disease mortality prediction model using traditional statistical methods and machine learning approach adjusting for non-invasive variables only (A, all participants; B, male; C, female). Adjusted for age, sex, diabetes status, hypertension status, physical activity level, and waist to height ratio. Abbreviations: PH, proportional hazard; RSF, Random Survival Forest; GBS, Gradient Boosting Survival; AUC, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Predictive performance using non-invasive plus invasive variables

Furthermore, the predictive performance of the both traditional statistical methods and machine learning approach models in the Validation Set, specifically including non-invasive plus invasive variables is presented in Fig. 2. The mean ROC-AUCs of the Cox proportional hazards model and with elastic net penalty were 0.833 (95% CI: 0.816–0.852) and 0.813 (95% CI: 0.788–0.831) across all participants. The mean ROC-AUCs of Survival Tree, RSF, and GBS were 0.819 (95% CI: 0.800-0.836), 0.844 (95% CI: 0.819–0.859), and 0.841 (0.816–0.854) across all participants, respectively. Overall, the predictive performance of both traditional statistical methods and machine learning prediction models was superior in females compared to males. Models that included invasive variables showed slightly higher predictive performance than those incorporating non-invasive variables only. However, the difference in predictive performance between models using non-invasive variables only vs. those with the additional inclusion of invasive variables was not significant, although this difference could not be statistically examined.

Prediction performance of cardiovascular disease mortality prediction model using traditional statistical methods and machine learning approach adjusting for both non-invasive and invasive variables (A, all participants; B, male; C, female). Adjusted for age, sex, diabetes status, hypertension status, physical activity level, waist to height ratio, fasting glucose, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride. Abbreviations: PH, proportional hazard; RSF, Random Survival Forest; GBS, Gradient Boosting Survival; AUC, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Predictive accuracy based on Brier scores

The predictive performances, expressed by the Brier score, of both traditional statistical methods and machine learning approach models in the Validation Set are presented. This includes models using non-invasive variables only (Supplemental Fig. 1) and models using both non-invasive and invasive variables (Supplemental Fig. 2). When evaluated in terms of the Brier score and integrated Brier score, the Cox PH and RSF models exhibited the lowest values, indicating relatively better predictive accuracy compared to the other models. Furthermore, the difference in predictive performance between models using only non-invasive variables and those including additional invasive variables was minimal, although this difference could not be statistically examined.

Comparative model performance based on ROC-AUC and c-Index

The comparative performance results for predicting CVD mortality (by including non-invasive variables only) among the Cox proportional risk models and with elastic net penalty using traditional statistical methods and the three machine learning models (RSF, GBS, Survival Tree) are presented in Table 2. Overall, the GBS model showed the highest ROC-AUC, and c-index compared to the other models. Furthermore, machine learning models appeared to outperform models using traditional statistical methods in terms of discriminatory performance and predictive accuracy, however, there were no notable differences, although this difference could not be statistically examined. The comparative performance results for predicting CVD mortality (by including both non-invasive and invasive variables) are presented in Table 3. Overall, the RSF or GBS model showed the highest ROC-AUC, and c-index compared to the other models. Similar to the prediction models using non-invasive variables only, machine learning models appeared to outperform models using traditional statistical methods in terms of discriminatory performance and predictive accuracy, however, there were no notable differences, although this difference could not be statistically examined.

Discussion

Utilizing large-scale longitudinal data, this study examined Koreans, incorporating non-invasive measurement indicators relevant to predicting CVD-specific mortality alongside additional blood indicators. First of all, all prediction performances examined in this study using non-invasive variables appear to be sufficiently valid in predicting CVD mortality. Overall, the predictive ability of the machine learning-based predictive model surpassed that of traditional statistical methods. Interestingly, there was no significant disparity in predictive performance between the model incorporating non-invasive predictive indicators only vs. the one integrating blood indicators when using either traditional statistical or machine learning methods.

The results of comparing the performance of models predicting CVD mortality over a 10-year observation period, which was divided into 10 equal intervals (each containing approximately 10% of the CVD mortality cases), showed that overall, machine learning-based models demonstrated higher predictive performance compared to Cox proportional hazard models for most segments during the observation period. The potential rationale for this is hypothesized as follows. First, the Cox proportional hazard model requires that the predictor variables used do not violate the proportional hazard assumption14. However, in practice it is common for the hazard ratio to change over time. For example, as age increases, the risk of mortality also tends to increase, and besides age, there is the possibility that the hazard ratio may be unstable over time15. Considering the biological and physiological responses, this assumption is often not valid15, and stratifying variables arbitrarily can lead to a deterioration in the predictive performance of the model16. Second, there is a limitation to applying the Cox proportional hazards model to high-dimensional data with a large number of predictor variables and computational complexity17. In contrast, algorithms used in machine learning-based prediction models such as RSF and GBS do not have assumption constraints on predictor variables like the proportional hazards assumption in the Cox model. Therefore, the selection of predictor variables is more flexible, and unlike Cox proportional hazards, these algorithms may be more appropriate for analyzing high-dimensional data. Furthermore, when stratifying variables, traditional statistical methods often rely on the discretion of the researcher to categorize continuous variables into discrete categories, which may lack clear criteria in some cases. In contrast, RSF can find the optimal split points based on the Gini index or entropy, which allows for a consistent and quantitative approach to finding the best split points that can most effectively differentiate between deceased and surviving individuals18. Additionally, the boosting algorithms used in this study have the characteristic of assigning weights to data that the prediction model fails to learn properly, thereby reconstructing the training data and boosting models with poor predictive performance through learning19,20. Third, unlike traditional statistical-based prediction models, the ensemble learning-based prediction models used in this study have improved predictive performance compared to conventional statistical models by preventing biased results and enabling more rational inference21,22.

Despite the superiority of RSF and GBS models, as shown by slightly higher time-dependent AUCs, the Cox model consistently showed lower Brier scores, suggesting better calibration. This indicates a trade-off: machine learning-based models may excel at distinguishing between high- and low-risk individuals, while the Cox model may provide more accurate absolute risk estimates. These findings highlight the need to consider both discrimination and calibration when evaluating prognostic models and suggest that combining strengths from both modeling approaches may offer a more robust framework for CVD mortality prediction.

In previous studies using traditional statistical methods, superior predictive performance was reported by including blood indicators in addition to non-invasive variables4,6,7,8,10. Our study found that a predictive model for CVD mortality rates including non-invasive predictive variables only was not inferior to the model including blood indicators. However, as the absolute difference in predictive performance was minimal and varied depending on sex and analytical approach, further research is needed to determine whether predictive models incorporating blood indicators provide more precise predictions of CVD mortality rates or if simpler predictive models demonstrate sufficient predictive performance.

In addition to biological differences, disparities in the occurrence of metabolic diseases, including cardiovascular conditions, exist between sexes. Therefore, previous studies have also segmented CVD prediction models by sex7,8,10,11. Besides such sex disparities, variations in life expectancy between males and females may also have influenced the results of our predictive model to some extent7. In previous studies evaluating CVD prediction, it has been noted that predictive performance varies with the passage of time (age), and although there is no consistent pattern, sex differences exist7. Furthermore, given the substantial observed sex disparity in CVD mortality rates in our study, such differences could have contributed to variations in predictive performance.

The Cox proportional hazards model is a well-established statistical method traditionally used in clinical research, and its primary purpose lies in inferential analysis, to estimate the effect of covariates on the hazard of an event. In contrast, machine learning models, including RSF and GBS, are optimized for predictive accuracy. In this study, the Cox model was used both as a reference model and to identify statistically significant predictors of CVD mortality, whereas the machine learning algorithms were implemented with the primary goal of enhancing risk prediction performance. Our findings underscore the distinction between inferential and predictive modeling approaches. While the Cox model offers interpretable associations between risk factors and outcomes, it is not inherently optimized for prediction. In contrast, the ML models in our study demonstrated stronger time-dependent discrimination, highlighting their potential utility in risk prediction applications.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to compare the predictive performance of CVD mortality prediction models using traditional statistical methods and machine learning techniques, using a large-scale longitudinal dataset representing Korean adults. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, study findings may not be generalized to wider populations. The predictive performance of various CVD prediction models may differ among different cultural and racial groups4,11. In addition to this, our cohort, from a nationwide health-screening dataset, is skewed toward younger adults (median age 39 years; 11% ≥60 years), leading to a lower CVD mortality incidence than the general Korean population. Although the large person-time provided sufficient power, the relative paucity of older participants may limit generalizability to high-risk older groups. Furthermore, due to the limited availability of predictive variables in our study, there were constraints in utilizing the advantages of machine learning algorithms that integrate diverse variables to derive predictive outcomes. Moreover, although our study examined a large dataset, there were relatively few cases of CVD mortality. High censoring rates in survival analysis can result in reduced statistical power and potentially biased or unstable hazard ratio estimates. These issues are particularly relevant in rare event scenarios, where overfitting or exaggerated risk estimates may occur in complex models. However, a large nationally representative cohort with extended follow-up in this study offers sufficient person-time for modeling. Furthermore, we applied internal validation strategies and multiple modeling approaches to ensure the robustness of our findings. While this study aimed to develop CVD risk models in Korean using population-based data, we acknowledge that its applicability to clinical or high-risk populations may require further validation and model refinement. Additional work with a large dataset that includes more cases of CVD is warranted to confirm and expand upon our findings. Lastly, due to the dynamic nature of survival analysis data, where the distribution and variance of survivors and non-survivors continuously change over time, conventional statistical tests, such as Delong’s test23, cannot be applied to compare the performances of the prediction models. Thus, it was not possible to technically compare their differences. Instead, we estimated the 95% confidence intervals for the time-dependent AUC via repeated bootstrap sampling and presented the differences in AUC between the models as an alternative approach.

Both traditional statistical and machine learning models using non-invasive indicators demonstrated excellent predictive performance for CVD mortality during a 10-year follow-up period based on a Korean medical dataset. Moreover, the predictive performance of models using non-invasive indicators only was not inferior to those incorporating blood indicators for prediction. Furthermore, when compared to models using traditional statistical methods, those using machine learning techniques demonstrated superior performance in predicting mortality during the 10-year follow-up period. Although further research in various settings is warranted to validate our results, our findings could be a milestone in the development of a healthcare system specifically focused on the CVD mortality prediction models. Our study results imply potential improvements in risk assessment and long-term prognostication for CVD-specific mortality, advocating for the adoption of non-invasive and machine learning-based approaches in healthcare decision-making to enhance patient outcomes.

Methods

Data and study participants

We used the data from a longitudinal study tracking 1,749,444 adults aged 20 and above who attended health checkups at the Korea Medical Institute (KMI) comprehensive screening centers (Seoul, Suwon, Busan, Daegu, Gwangju, and Jeju) between January 2011 and December 2019. KMI centers provide standardized examinations that are subsidized by the National Health Insurance Service and therefore collect participants from all provinces, yielding a sample reflective of the general working-age population. Of the initial participants surveyed at KMI and who completed the health questionnaire, physical, anthropometric, and laboratory assessments, a total of 1,739,903 individuals were included in the analysis, excluding 9,541 individuals who died from causes unrelated to CVD. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in advance, and the study received approval from the Yonsei University Bioethics Committee. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Measurements

Physical activity

Physical activity levels were assessed using KMI’s Korean standardized questionnaire along with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire24. The intensity of physical activity was quantified using metabolic equivalent task (MET) values, with walking assigned a value of 3.3 METs, moderate-intensity activities rated at 4.0 METs, and high-intensity activities at 8.0 METs or higher. Total physical activity was then converted into MET-minutes per week, factoring in both the duration (in minutes) and frequency (times per week) of participation. For analytical purposes, physical activity was categorized into three groups: inactive, minimally active, and active, based on IPAQ criteria. Specifically, minimally active was defined as meeting at least one of the following criteria: engaging in at least three days of vigorous activity for a minimum of 20 min per week, or participating in moderate-intensity activity or walking for at least 30 min on at least five days per week, or any combination of walking, moderate, and vigorous activity for a minimum of five days per week, amounting to at least 600 MET-minutes per week. Active individuals were those who either engaged in vigorous activities on at least three days per week, accumulating at least 1500 MET-minutes per week, or participated in walking for at least seven days per week, along with a combination of moderate and vigorous activities totaling at least 3000 MET-minutes.

Sociodemographics, health characteristics, and clinical measures

Sex and age were measured using a general questionnaire. Additionally, the waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) was calculated by dividing waist circumference by height, using measurements obtained from the KMI health examination data. The KMI health examination data also included major chronic disease status, including the presence or absence of diabetes, and hypertension (yes/no). Blood indicators including triglycerides, fasting blood glucose, and high-density/low-density lipoprotein cholesterol were measured after a 12-hour fast using a blood analyzer (Hitachi-7600 analyzer; Hitachi Ltd., Japan).

Cardiovascular disease mortality

CVD mortality was defined as follows: among the deceased individuals within a 10-year follow-up period, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), encompassed essential hypertension, hypertensive heart disease, angina, acute myocardial infarction, other acute ischemic heart diseases, chronic ischemic heart disease, pulmonary embolism, other pulmonary heart diseases, acute and subacute endocarditis, acute myocarditis, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrest, paroxysmal tachycardia, cardiac fibrillation and flutter, cardiac arrhythmia, heart failure, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, other non-traumatic intracranial hemorrhages, cerebral infarction, other cerebrovascular diseases, sequelae of cerebrovascular diseases, mesenteric sclerosis, and aortic aneurysm dissection.

Statistical analysis, predictive model development, and performance evaluation

All conventional statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 25.0, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics and frequency analyses were conducted to assess the general characteristics of the participants at baseline concerning CVD mortality. Differences in general characteristics between men and women were analyzed using independent samples t-tests or Chi-square tests as appropriate. For predictors, missing values were observed for 352,165 instances of walking physical activities, 39,754 for WHtR, 30,044 for waist circumferences, 25,924 for fasting blood glucose 19,490 for body mass index, 19,489 for body weight, 19,405 for height, 18,826 for moderate physical activities, and 15,041 for high-intensity physical activities. Missing values were addressed using the MissForest library25, which employs machine learning-based Random Forest techniques to impute missing values by learning from the characteristics and distribution of data.

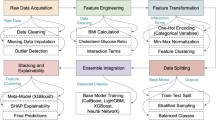

For the machine learning analysis, 1,390,489 participants (80% of the total) were allocated to the “Model Building Set (Train & Internal Validation Set),” while the remaining 20% (n = 347,623) participants were assigned to the “Validation Set (Test Set).” A predictive model for CVD mortality was constructed using the model building set, and its performance was assessed using the Validation Set, representing data encountered by the developed model for the first time. Survival analysis was conducted, with the survival function estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model and the Cox proportional hazards model with elastic net penalty26 and predictive algorithms such as Random Survival Forest (RSF), Gradient Boosting Survival (GBS), and Survival Tree models. For the Cox proportional hazards models, the proportional hazards assumption was assessed using both graphical methods (log-minus-log plots) and Schoenfeld residual tests. These diagnostics indicated no major violations of the proportional hazard assumption for the primary predictors. The performance of the developed predictive model was evaluated based on the time-dependent area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC)27 and the c-index28 for discriminatory performance, and the time-dependent Brier score and the integrated Brier score29 for predictive accuracy.

Predictors (i.e., exposure variable) included age at baseline, sex, duration of observation period, presence of diabetes, hypertension, physical activity levels (inactive, minimally active), and WHtR. CVD mortality within a 10-year period was the primary outcome of interest. Furthermore, we compared the predictive abilities between the model using non-invasive predictors only vs. the model integrating additional blood indicators (invasive variables; triglyceride, fasting blood glucose, high/low-density lipoprotein cholesterol), presumed to confer enhanced predictive capacity. Prior to conducting the predictive model analysis, Cox regression analysis was used to identify predictors that potentially violated the proportional risk assumption30. Categorical variables were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier analysis method19. In the survival curve analysis based on the level of physical activity, an intersection emerged between participants categorized as active and those classified as minimally active around 3 years following the observation period. To further assess this observation, an additional Schoenfeld residual test was performed14,31, affirming the ongoing statistical significance of the risk ratio for CVD mortality concerning physical activity across the duration of the study. A significant temporal variation in the risk ratio of CVD mortality was observed with respect to age among the continuous variables. Consequently, an interaction variable, denoted as age*observation period, was derived and incorporated into the predictive model. This replacement was implemented to address the violation of the proportional risk assumption associated with the age variable30. However, including the age*observation period term did not materially change the prediction results; therefore, we presented the models without this term. Predictor selection followed a sequential two-step process. First, a multivariable Cox model was fitted for inferential screening to remove variables lacking a statistically or clinically meaningful association with CVD mortality4,6,7,8,10. Second, the retained variables were passed through an ensemble feature-selection framework (filter, wrapper and embedded algorithms)32. The final predictor set was entered unchanged into both the Cox (elastic-net) and the three machine-learning models (RSF, GBS, Survival Tree). By holding the predictor set constant, this design attributes performance differences exclusively to the modeling approach. Subsequently, the development and validation of predictive models were conducted using the Jupyter notebook integrated development environment, Python version 3.8.8.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request. All statistical analyses and machine learning procedures, including model training, validation, and performance evaluation, were conducted using Python (ver. 3.8.8.). The full analysis code, including scripts for data preprocessing and model implementation, is available at: https://github.com/Seong-Gyu-Choi/Koraen-specific_CVD_risk_model/blob/main/CVD_Risk_model.ipynb.

References

Benjamin, E. J. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 137 (12), e67–e492. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558 (2018).

Statistics Korea (KOSTAT). Causes of mortality statistics. 2022. website: (2021). https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a20108100000&bid=11773&act=view&list_no=421206

Fishman, G. I. et al. Sudden cardiac death prediction and prevention: report from a National heart, lung, and blood Institute and heart rhythm society workshop. Circulation 122 (22), 2335–2348. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976092 (2010).

Jung, K. J. et al. The ACC/AHA 2013 pooled cohort equations compared to a Korean risk prediction model for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 242 (1), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.07.033 (2015).

Markwerth, P. et al. Sudden cardiac death—update. Int. J. Legal Med. 135, 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-020-02481-z (2021).

D’Agostino Sr, R. B. et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham heart study. Circulation 117 (6), 743–753. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579 (2008).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Framingham risk score and prediction of lifetime risk for coronary heart disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 94 (1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.023 (2004).

Conroy, R. M. et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in europe: the SCORE project. Eur. Heart J. 24 (11), 987–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00114-3 (2003).

Wells, S. et al. Cohort profile: the PREDICT cardiovascular disease cohort in new Zealand primary care (PREDICT-CVD 19). Int. J. Epidemiol. 46 (1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv312 (2017).

Ahn, K. A. et al. Framingham Equation Model Overestimates Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease in Korean Men and Women. Epidemiology and Health. ;28(2):162–170. website: (2006). https://www.e-epih.org/journal/view.php?number=54

Selvarajah, S. et al. Comparison of the Framingham risk score, SCORE, and WHO/ISH cardiovascular risk prediction models in an Asian population. Int. J. Cardiol. 176 (1), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.066 (2014).

Yun, J. M. et al. Prediction of cardiovascular disease in Korean population: based on health risk appraisal of National health screening program. J. Korean Med. Association. 1975 (8456), 2093–5951. https://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2017.60.9.746 (2017).

Krittanawong, C. et al. Machine learning prediction in cardiovascular diseases: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 16057. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72685-1 (2020).

Dessai, S. & Patil, V. Testing and interpreting assumptions of COX regression analysis. Cancer Res. Stat. Treat. 2 (1), 108–111. https://doi.org/10.4103/CRST.CRST_40_19 (2019).

Kuitunen, I. et al. Testing the proportional hazards assumption in Cox regression and dealing with possible non-proportionality in total joint arthroplasty research: methodological perspectives and review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 22 (1), 489. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04379-2 (2021).

Stensrud, M. J. & Hernán, M. A. Why test for proportional hazards? JAMA 323 (14), 1401–1402. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1267 (2020).

Ternès, N., Rotolo, F. & Michiels, S. Empirical extensions of the Lasso penalty to reduce the false discovery rate in high-dimensional Cox regression models. Stat. Med. 35 (15), 2561–2573. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6927 (2016).

Ziegler, A. & König, I. R. Mining data with random forests: current options for real-world applications. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Min. Knowl. Discovery. 4 (1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1114 (2014).

Dietterich, T. G. Ensemble methods in machine learning. In: Multiple Classifier Systems: First International Workshop, MCS 2000 Cagliari, Italy, June 21–23, 2000 Proceedings 1. Springer; (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-45014-9_1

Schapire, R. E. The strength of weak learnability. Mach. Learn. 5, 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00116037 (1990).

Bühlmann, P. Bagging, Boosting and Ensemble Methods (Springer, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21551-3_33

Sagi, O. & Rokach, L. Ensemble learning: A survey. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. ;8(4):e1249. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1249

DeLong, E. R., Vernon, W. B. & Bollinger, R. R. Sensitivity and specificity of a monitoring test. Biometrics 947–958. https://doi.org/10.2307/2530966 (1985).

Oh, J. Y. et al. Validity and reliability of Korean version of international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) short form. J. Korean Acad. Family Med. 28 (7), 532–541. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.2012.33.3.144 (2007).

Tang, F. & Ishwaran, H. Random forest missing data algorithms. Statistical Analysis and Data Mining: The ASA Data Sci. J. ;10(6):363–377. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/sam.11348. (2017).

Wu, Y. Elastic net for cox’s proportional hazards model with a solution path algorithm. Statistica Sinica. 22, 27. https://doi.org/10.5705/ss.2010.107 (2012).

Bowers, A. J. & Zhou, X. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under the curve (AUC): A diagnostic measure for evaluating the accuracy of predictors of education outcomes. J. Educ. Students Placed Risk (JESPAR). 24 (1), 20–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2018.1523734 (2019).

Harrell Jr, F. E., Lee, K. L. & Mark, D. B. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat. Med. 15 (4), 361–387. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4 (1996).

Graf, E. et al. Assessment and comparison of prognostic classification schemes for survival data. Stat. Med. 18 (17-18), 2529–2545. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990915/30)18:17/18<2529::aid-sim274>3.0.co;2-5 (1999).

Hess, K. R. Graphical methods for assessing violations of the proportional hazards assumption in Cox regression. Stat. Med. 14 (15), 1707–1723. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780141510 (1995).

Abeysekera, W. & Sooriyarachchi, M. Use of schoenfeld’s global test to test the proportional hazards assumption in the Cox proportional hazards model: an application to a clinical study. (2009). https://doi.org/10.4038/jnsfsr.v37i1.456

Chen, C. W. et al. Ensemble feature selection in medical datasets: combining filter, wrapper, and embedded feature selection results. Expert Syst. 37 (5), e12553. https://doi.org/10.1111/exsy.12553 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants who were included in the Korea Medical Institute medical examination data. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2024S1A5B5A16024593). This work was supported by the Yonsei Signature Research Cluster Project (2024-22-0009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S.K. analyzed data and drafted, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; M.O. consulted on analyses and drafted, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; L.D.H. consulted on analyses and drafted, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; J.S.H. consulted on analyses and drafted, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; J.Y.J. designed the study, consulted on analyses, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, S., Oh, M., Lee, D.H. et al. Invasive and non-invasive variables prediction models for cardiovascular disease-specific mortality between machine learning vs. traditional statistics. Sci Rep 15, 35093 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18853-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18853-7