Abstract

Patient satisfaction is a critical dimension of healthcare quality and hospital management, particularly in chronic treatments such as hemodialysis, where patients undergo frequent and time-intensive procedures. Assessing patient satisfaction is inherently a multi-attribute group decision-making (MAGDM) problem that involves both subjectivity and uncertainty, which many existing approaches fail to address adequately. To overcome these challenges, this study proposes a novel patient satisfaction assessment framework that integrates rough numbers with the best-worst method (BWM) and the gained and lost dominance score (GLDS) method. A comprehensive criteria system for evaluating hemodialysis experiences is developed through literature review and expert consultation. Rough numbers are employed to represent the linguistic and uncertain judgments of patients and experts, while the rough BWM determines robust criteria weights and the rough GLDS ranks hospital alternatives by considering both overall and criterion-level performance. The proposed method is validated through a case study of five hospitals in Jinan, China. The results confirm that the framework produces reliable and interpretable rankings, identifies Hospital A as the best-performing institution, and demonstrates robustness under sensitivity analysis. These findings highlight the value of the rough BWM-GLDS method as a practical and transparent tool for evaluating patient satisfaction in healthcare services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The quality of medical services has been traditionally measured by the number of patients receiving treatments and recovered in China, as treatment has been the center of hospital and medical service1. However, with the rapid development of the healthcare industry in China, the focus of medical services has gradually shaped from “treatment-centered” to “patient-centered”2. Properly measuring patient satisfaction with the medical experience could help monitor the performance of medical services and may also implicate ways to improve medical services, and is conducive to hospital management3,4,5. Therefore, patient satisfaction assessment has become an important issue of hospital management and medical service support6,7,8. Patient satisfaction assessment can be generally viewed as a multi-attribute group decision-making (MAGDM) problem, where several criteria such as staff attitude, waiting time, and environment are considered and assessed by the patients9,10,11. Correspondingly, there are mainly three phases for patient satisfaction assessment, namely, (1) the representation of patient satisfaction degree on different criteria, (2) the calculation of assessment criteria weight, and (3) the integration of patient satisfaction degree on different criteria.

One notable part of patient satisfaction assessment is the involvement of patients, as different criteria are assessed by the patients. Though they are not accurate from the professional point of view, the assessments of patients could accurately reflect the subjective and uncertain attitudes of patients toward medical services12,13,14. However, due to the involvement of patients, patient satisfaction assessment could suffer from subjectivity and uncertainty. Conventional patient satisfaction assessment methods usually use numerical scales to represent the satisfaction degree of patients15. However, such a representation is arbitrary as there are many factors even subjectivity and uncertainty affecting the patient satisfaction assessment. One significant challenge for patient satisfaction assessment is that it is often difficult and even impractical for patients to provide accurate judgments as some criteria are qualitative in nature and subjectivity often exists. The linguistic method is a close way to model human cognition through linguistic variables such as “good”, “moderate” and “bad”, so that the assessment criteria could be expressed in a flexible way. Moreover, by using linguistic variables, the subjectivity and uncertainty of patients’ judgments could be modeled16,17,18. However, when many patients are involved, their linguistic judgments should be aggregated, due to the subjectivity and uncertainty of these judgments, how to aggregate individual judgments from group decision-makers and manage the subjectivity among them has become an urgent task19,20. Hence, Zhu et al.21 proposed rough number based on rough set theory to handle subjective judgments of customers and determine the boundary intervals. A rough number is usually expressed by lower limit, upper limit and the rough boundary interval, and it only depends on the original data, i.e., individual judgments of group decision-makers. Hence, rough number could capture the decision-makers’ real intention and improve the objectivity of the decision-making without the requirement of auxiliary information22,23,24.

In patient satisfaction assessment, there are often various criteria, each representing a specific aspect. Normally, these different criteria would have different importance, in other words, different criteria would have different weights. For criteria weight calculation, both the objective weight calculation method such as the entropy-based method25 and the subjective weight calculation method have been applied. However, objective weight calculation methods only focus on the judgment information and cannot reflect experts preferences, whereas subjective weight calculation methods could effectively reflect experts preferences and have been widely used. The analytical hierarchy process (AHP) is the most widely used subjective weight calculation method, and it uses pairwise comparisons to represent the relative importance of one criterion over another26,27. However, the number of pairwise comparisons in AHP is dependent on the number of criteria, when there are n criteria, it will need \(n(n-1)/2\) pairwise comparisons to represent the preference information of all criteria. That is to say, when the number of criteria increases, the computation burden for experts would increase exponentially and the inconsistency will increase, thus leading to inaccurate criteria weights. To this end, Rezaei28 proposed the best-worst method (BWM) by reducing redundant pairwise comparisons. In the BWM, two representative criteria, namely the best (most important) and the worst (least important) criteria are selected in advance, and each criterion is only compared with the best and worst criteria. Thus, the number of pairwise comparisons is \(2n-3\), significantly fewer than AHP29. Due to this advantage, the BWM has attracted significant attention and has been applied to various kinds of problems such as supplier selection30, reliability assessment31 and others32. To capture the uncertainty in experts judgments, various extensions of BWM have been introduced, such as fuzzy BWM33, intuitionistic fuzzy BWM34 and probabilistic linguistic BWM35. However, these extensions are established under the assumption that the best and worst criteria are selected uniformly by the experts, which is not necessarily the case, in addition, these extensions do not take rough number into consideration. Thus, due to the flexibility and effectiveness of rough numbers in representing linguistic and uncertain judgments of decision-makers, the rough BWM is presented to calculate criteria weights with rough numbers.

In order to derive the overall satisfaction degree in terms of different alternatives such as different hospitals based on the satisfaction degrees of each criterion, it is necessary to adopt proper MAGDM methods to aggregate the satisfaction degrees on different criteria. In general, based on the aggregation function, the MAGDM methods could be divided into two kinds: utility-based methods and outranking methods. For the utility-based methods such as the TOPSIS (technique for order preference by similarity to ideal solution)36, MAIRCA (multi-attributive ideal-real comparative analysis)37 and MULTIMOORA (multiplicative multi-objective optimization by ratio analysis)38, though they have shown to be effective and simple in ranking different alternatives, the relationships among different alternatives cannot be accurately measured. Moreover, the chosen alternative is often a compromise solution instead of an optimal one. For outranking methods such as PROMETHEE (preference ranking organization method for enrichment evaluations)39 and ELECTRE (elimination et choix traduisant la realité in French)17, they could model the relations of difference, the preference among alternatives based on pairwise comparisons, thus helping identify an optimal alternative that performs well on all criteria. However, these methods often fail to consider the acceptable margin. In this regard, Wu and Liao40 proposed the gained and lost dominance score (GLDS) method that calculates both the net gained dominance score and net lost dominance score of each alternative, where the net gained dominance score is used to ensure the selected alternative performs well in the general term and the net lost dominance score is used to ensure the selected alternative will not perform too badly under some criteria41,42. Due to the consideration of both overall performance and specific performance of the alternative, the GLDS method has been applied to many problems, including development evaluation43, risk analysis44 and supplier selection45.

Patient satisfaction has increasingly become a cornerstone of modern healthcare quality assessment, complementing traditional measures such as treatment outcomes and recovery rates. In chronic care domains such as hemodialysis, where patients undergo frequent and lengthy treatments, satisfaction is not only an indicator of service quality but also a determinant of treatment adherence and long-term health outcomes. Recent studies confirm that dissatisfaction in such settings can lead to reduced compliance, greater dropout rates, and poorer medical outcomes, thereby threatening the sustainability of healthcare systems46. Consequently, developing a reliable and effective framework to evaluate patient satisfaction is both a clinical and managerial necessity.

Despite its importance, patient satisfaction assessment faces several critical challenges. First, patients’ judgments are inherently subjective and uncertain, often expressed in qualitative terms that are difficult to quantify with precision. Second, the process involves multiple criteria that vary in importance, requiring systematic determination of criteria weights. Third, hospital managers not only need to identify the best-performing institution overall but also to ensure that no alternative performs poorly on critical aspects, since negative experiences can undermine overall patient trust. Current approaches often fail to address these challenges simultaneously: traditional numerical scales inadequately capture uncertainty, methods such as AHP impose heavy cognitive burdens on experts, and many existing aggregation methods overlook worst-case performance.

To address these gaps, this study draws on three methodological advances. Rough numbers provide a transparent, data-driven way to represent uncertain and linguistic patient judgments, avoiding arbitrary membership functions and auxiliary hesitation parameters47,48,49,50. The BWM offers a more efficient and consistent approach to criteria weighting, requiring substantially fewer comparisons than AHP. Moreover, recent extensions of BWM have demonstrated its adaptability and robustness across diverse domains, including sustainability evaluation, supplier selection, and healthcare-related decision-making51,52. Finally, the GLDS method ensures balanced evaluations by considering both net gains and net losses, thus capturing overall quality while preventing serious deficiencies. This combination is particularly well suited to patient satisfaction contexts, where both maximizing positive experiences and minimizing negative ones are crucial.

Taken together, these considerations highlight a clear research gap: existing approaches do not simultaneously (i) model patient judgments under uncertainty with minimal assumptions, (ii) determine reliable and consistent criteria weights efficiently, and (iii) balance overall and worst-case performance in ranking hospitals. Bridging this gap is essential for developing decision-making tools that can provide actionable insights for healthcare management.

Based on this discussion, the study is guided by the following research hypothesis: Integrating rough numbers with the BWM and the GLDS method provides a more robust and interpretable mechanism for patient satisfaction assessment compared with conventional approaches.

This hypothesis underscores the urgency of advancing patient-centered evaluation frameworks that accommodate subjective and uncertain judgments while ensuring transparency and robustness. Confirming this hypothesis will demonstrate the practical value of the proposed model in improving the evaluation and management of healthcare services.

The purpose of this study is to develop a reliable and effective mechanism to assess patient satisfaction with the hemodialysis experience. To achieve that, we extend the BWM and the GLDS method with rough numbers, and integrate these two methods to propose an integrated MAGDM method, called the R-BWM-GLDS method, for assessing patient satisfaction with hemodialysis experience. The main contributions and innovations of this study could be summarized as follows:

-

(1)

A comprehensive assessment index system for patient satisfaction of hemodialysis experience is established through literature analysis and empirical analysis, which includes 13 criteria from 3 different aspects.

-

(2)

The GLDS method is extended with rough numbers, and rough GLDS (R-GLDS) method is proposed. where the assessments of different patients are expressed by rough numbers, and the net gained and lost dominance scores are calculated to assess alternatives.

-

(3)

The R-BWM is combined with R-GLDS method, and the R-BWM-GLDS method is proposed for MAGDM problems, which considers both the overall performance of the alternative and the performance of the alternative under each criterion, so that the selected alternative could be ensured to be optimal.

-

(4)

The patient satisfaction degrees of the hemodialysis experience in five different hospitals are assessed using the proposed method, and the hospitals are ranked according to the satisfaction degrees of patients. Moreover, by using the dominance scores, the performance of different hospitals with regard to each criterion could be measured and analyzed, thus helping managers identify criteria to be improved.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 establishes the criteria system for assessing patient satisfaction with the hemodialysis experience. Section 3 presents the proposed R-BWM-GLDS method for patient satisfaction assessment. A practical case study is studied in Section 4. Section 5 provides further analysis and discussion of the results. Section 6 concludes the paper.

Problem statement

Hemodialysis is a routine treatment for patients with end-stage renal disease, typically performed several times per week and requiring several hours per session. Because of the frequency and intensity of treatment, patient satisfaction depends not only on clinical outcomes but also on the efficiency of service processes, the performance of medical staff, and the quality of the treatment environment. Dissatisfaction in this context may reduce treatment adherence, compromise health outcomes, and diminish overall quality of life. Hence, systematic evaluation of patient satisfaction in hemodialysis departments is critical for continuous quality improvement and effective hospital management.

In this study, five hospitals in Jinan, China are examined as case examples. These hospitals include large tertiary institutions and specialized centers that provide hemodialysis services. Patient surveys are conducted across these hospitals to collect direct feedback on treatment experiences. This case study setting provides a practical context for applying and validating the proposed R-BWM-GLDS method, as it allows comparison of hospital performance while accounting for the subjective and uncertain nature of patient judgments.

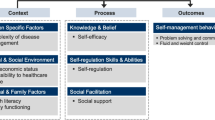

To establish an appropriate evaluation framework, both literature analysis and empirical analysis are conducted. First, a literature search in Web of Science and ScienceDirect using the keywords “patient satisfaction,” “assessment,” and “criteria” identified 21 candidate criteria from previous studies. Second, consultations with 17 experts from tertiary hospitals in Jinan were carried out to refine these criteria and ensure relevance to the hemodialysis context. Based on this combined analysis, 13 criteria were selected as the final assessment framework for patient satisfaction with hemodialysis. These criteria are grouped into three dimensions: hemodialysis process (\(C_1\)), staff performance (\(C_2\)), and treatment environment (\(C_3\)). The hierarchical structure of these criteria, including first-level and second-level elements, is presented in Fig. 1.

-

(1)

Procedures of hemodialysis (\(C_1\)) The aspect of procedures of hemodialysis describes the experience of the patients with the hemodialysis procedure, and it is an important part of the criteria system. There are five sub-criteria in this aspect:

-

(a)

Total waiting time (\(C_{11}\)). Total waiting time refers to the total time from queuing to the completion of hemodialysis. It is obvious that the shorter the total time is, the more satisfied the patients are.

-

(b)

Procedures before hemodialysis (\(C_{12}\)). Procedures before hemodialysis include changing clothes, weighing, measuring blood pressure, finding the bed. Whether the bed is easy to find and whether the processes of weighing and measuring blood pressure are convenient would affect the satisfaction degree of patients.

-

(c)

Instructions after hemodialysis (\(C_{13}\)). After completing the hemodialysis, patients need to know the instructions for pressing the blood access puncture point and weighing again. Clear instructions after the hemodialysis would increase the satisfaction degree of a patient.

-

(d)

Improvement of clinical outcome (\(C_{14}\)). Patients need to assess hemodialysis adequacy through regular examinations. Efficient cleansing of the blood of all relevant uraemic toxins and corrected metabolic disorders (e.g. anaemia, mineral bone disease) are key factors for patients to be satisfied with hemodialysis treatment.

-

(e)

Patient privacy protection (\(C_{15}\)). Hospital is responsible for protecting patients’ privacy. It includes protecting patients’ privacy when they communicate with doctors, take medicines or get their analysis reports. When patients feel they are being protected, they will be more satisfied with the medical institution.

-

(a)

-

2.

Medical staffs of hemodialysis The aspect of medical staffs of hemodialysis refers to the professionalism and performance of the medical staff, and it has four sub-criteria:

-

(a)

Arteriovenous fistula puncture comfort (\(C_{21}\)). In the process of hemodialysis, the professional operation of nurses, the pain caused to patients, and the success rate of puncture would affect the experience of patients.

-

(b)

Service attitude (\(C_{22}\)). Because of illness, it is inevitable that patients feel nervous when they go to the hospital. The bad attitude of the staff can directly reduce the patients’ experience.

-

(c)

Timely response from staff (\(C_{23}\)). Patients are not familiar with medical knowledge and the environment of the hospital. Hence, they need timely responses from staff when they ask for help.

-

(d)

Emergency response (\(C_{24}\)). Whether the medical staff can deal with emergencies quickly and effectively is an important evaluation standard for patients’ satisfaction. The emergencies during hemodialysis include hemodialysis disequilibrium syndrome, venous air embolism, hemolysis, venous needle dislodgement, vascular access hemorrhage, major allergic reactions to the dialyzer or treatment medications, and disruption or contamination of the hemodialysis water system.

-

(a)

-

3.

Environment of hemodialysis room (\(C_3\)) The environment of the hemodialysis room is also an important dimension to affect the satisfaction degree of patients who need hemodialysis, and patients may spend most of their time there. There are four sub-criteria in this aspect:

-

(a)

Guide sign (\(C_{31}\)). Clear guide signs to the hemodialysis bed would help patients quickly find their destination, which not only saves the patients’ time, but also facilitates the flow of patients.

-

(b)

Order in the hemodialysis room (\(C_{32}\)). The order in the hemodialysis room influences the impression of patients in the room. Moreover, a well-organized environment can reduce anxiety in patients.

-

(c)

Comfort of the hemodialysis room (\(C_{33}\)). It means that patients can rest in a comfortable place during hemodialysis. A satisfactory hemodialysis room should have clean beds, proper temperature, convenient charging, and a clean and tidy hall.

-

(d)

Rescue equipment (\(C_{34}\)). The life-threatening complication may occur during hemodialysis. Complete rescue equipment and modern hemodialysis machines with numerous safety features contribute to the low rate of hemodialysis emergencies and increase patient satisfaction in hemodialysis rooms.

-

(a)

Method

In this section, in order to handle the ambiguity and fuzziness in patient satisfaction assessment with linguistic assessment information, an R-BWM-GLDS method is proposed. The proposed method consists of two phases. In the first phase, a group of experts is invited to determine the weights of criteria using R-BWM. In the second phase, assessment information from patients is gathered and transformed into rough numbers, and different alternatives are ranked using R-GLDS.

Let there be a patient satisfaction assessment problem PSA, which is a MADM problem. Suppose there is a group of experts \(E_k(k=1,2,\dots ,T)\), a group of patients \(P_{k'}(k'=1,2,\dots ,T')\), m alternatives \(A_i(i=1,2,\dots ,m)\) and n criteria \(C_j(j=1,2,\dots ,n)\) with corresponding weight vector \(\omega =(\omega _1,\omega _2,\dots ,\omega _n)^T\). In this study, the group of T experts is invited to evaluate the importance of the criteria and the group of \(T'\) patients is invited to assess the performance of different alternatives with regard to the assessment criteria.

In this section, the proposed method is described in four different parts. Firstly, the basic definitions of rough numbers are introduced. Secondly, the weight calculation process based on R-BWM is described. Then, the process of assessing and ranking different alternatives based on the R-GLDS method is introduced. Finally, the process of the R-BWM-GLDS method is presented.

Rough number

In many practical applications, there often involves more than one decision-maker in the MADM problem. It is essential for group decision-making problems to properly determine a method for integrating individual assessments and judgments from a group of decision-makers. Zhu et al.21 introduced the rough number method to model the assessments of a group of decision-makers by calculating lower and upper approximations.

Let U be a universal set containing all objects and R be a set of l classes \((e_1,e_2,\dots ,e_l)\) covering all objects in U. \(R=\{e_1,e_2,\dots ,e_l\}\) is a ordered set such that \(e_1<e_2,\dots <e_l\), and it can be used to define object properties. Y is an arbitrary object of U. Then, \(\forall Y\in U\), \(e_r\in R\) and \(1\le r\le t\), the lower and upper approximations \((\underline{apr}(e_r),\overline{apr}(e_r))\) of \(e_r\) is defined as:

According to the definitions of lower and upper approximations, a group of decision-makers judgments could be expressed by the rough lower and upper limits \((\underline{lim}(e_r),\overline{lim}(e_r))\). The rough lower and upper limits are calculated using the mean of the elements in the lower and upper approximations as:

where \(a_i\) and \(b_i\) denote the elements in the lower and upper approximations of \(e_r\), \(N_L\) and \(N_U\) represent the total number of elements involved in the lower and upper approximations of \(e_r\), respectively.

For a group of decision-makers, its linguistic assessments could be equivalently transformed into a set of rough numbers \(RB(e_r)\) as:

Let \(RN(a)=[\underline{lim}(a),\overline{lim}(a)]\) and \(RN(b)=[\underline{lim}(b),\overline{lim}(b)]\) be two rough numbers, the distance between RN(a) and RN(b) is calculated by:

Let \(RN(a)=[\underline{lim}(a),\overline{lim}(a)]\) and \(RN(b)=[\underline{lim}(b),\overline{lim}(b)]\) be two rough numbers, and k be a real positive number, then there is:

Unlike traditional fuzzy sets, which require the definition of membership functions that may introduce subjectivity, rough numbers rely only on observed data and avoid auxiliary assumptions. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets and hesitant fuzzy sets extend the fuzzy framework by incorporating additional parameters such as non-membership degrees or hesitation information. However, these approaches still depend on parameters that must be specified in advance, which may reduce transparency and bias the results.

By contrast, rough numbers are constructed in a fully data-driven manner and require no external information beyond the collected evaluations. This makes them particularly appropriate for healthcare service assessment, where patient judgments are typically expressed in linguistic terms and involve significant subjectivity and uncertainty. Through preserving the natural variability of patient inputs while avoiding arbitrary parameterization, rough numbers enhance the objectivity, reliability, and interpretability of the decision-making process.

The R-BWM method

In the proposed method, the group of T experts is invited to assess the relative importance of different criteria using linguistic judgments, and the R-BWM, detailed in this section, is used to determine criteria weights.

Suppose that a group of T experts \(E_k(k=1,2,\dots ,T)\) are invited to assess the weights of n criteria \(C_j(j=1,2,\dots ,n)\) using linguistic judgments based on their experience and knowledge. Then the initial pairwise comparison matrix of the group of experts can be expressed by

where \(a_{ij}^k\) represents the relative importance of the ith criterion over the jth criterion determined by the kth expert. It can be noted that for AHP, the above matrix would require \(n(n-1)/2\) pairwise comparisons, whereas for BWM, only \(2n-3\) pairwise comparisons are required to determine the optimal weights, thus, the BWM could significantly reduce the computation burden for the experts.

For the problem with a set of n criteria \(\{C_1,C_2,\dots ,C_n\}\), each expert \(E_k\) is invited to determine the best (most important) criterion \(C_B\) and the worst (least important) criterion \(C_W\) based on their experience. It should be noted that different experts may choose different best and worst criteria as their opinion may differ. When that happens, experts that choose the same pairs of best and worst criteria are assigned to the same group.

For the identified best and worst criteria, each expert \(E_k\) is invited to provide his/her judgments on the preference of the best criterion \(C_B\) over each criterion \(C_j\) using linguistic terms, which could be equivalently transformed to a scale number, and the best-to-others vector of expert \(E_k\) could be obtained as:

Similarly, the preferences of the criteria \(C_j\) over the worst criterion \(C_W\) are assessed by each expert, and the others-to-worst vector of expert \(E_k\) is expressed by:

It should be noted that the relative importance of each criterion over itself is 1, that is \(v_{BB}^k=v_{WW}^k=1\).

According to Eqs. (5) and (6), the best-to-others and others-to-worst vectors of T experts are obtained. As the judgments of these experts may not be necessarily the same, their preferences could be integrated to obtain more comprehensive results. In this study, the rough number is utilized to represent the integrated preferences of the best criterion over other criteria and other criteria over the worst criterion. It is noted that only vectors of the same group of experts, i.e., experts choosing the same best and worst criteria, could be integrated. The integrated rough best-to-others and others-to-worst vectors are expressed as:

Based on the integrated rough best-to-others and others-to-worst vectors, the rough weights of the criteria could be determined. Ideally, if the judgments of all experts are fully consistent, there will be \((\underline{\omega }_B,\overline{\omega }_B)/(\underline{\omega }_j,\overline{\omega }_j)=(\underline{v}_{Bj},\overline{v}_{Bj})\) and \((\underline{\omega }_j,\overline{\omega }_j)/(\underline{\omega }_W,\overline{\omega }_W)=(\underline{v}_{jW},\overline{v}_{jW})\). However, as inconsistency is inevitable for a group decision-making problem like the one in this study, the rough optimal weights of the criteria could be obtained by minimizing the maximum absolute differences \(|(\underline{\omega }_B,\overline{\omega }_B)/(\underline{\omega }_j,\overline{\omega }_j)-(\underline{v}_{Bj},\overline{v}_{Bj})|\) and \(|(\underline{\omega }_j,\overline{\omega }_j)/(\underline{\omega }_W,\overline{\omega }_W)-(\underline{v}_{jW},\overline{v}_{jW})|\) for all j, which can be expressed by the following optimization model:

By multiplying the denominator, Eq. (9) could be equivalently transformed into an linear optimization model as:

It should be noted that the same importance is assigned to both the lower and upper bounds of weights. By solving Eq. (8), the rough optimal weights \(\delta (\omega ^*)=([\underline{\omega }_1^*,\overline{\omega }_1^*],[\underline{\omega }_2^*,\overline{\omega }_2^*],\dots ,[\underline{\omega }_n^*,\overline{\omega }_n^*])\) and the optimal value of \(\varepsilon\), denoted by \(\varepsilon ^*\) can be obtained. It is worth noting that as stated above, when different best and worst criteria are selected by the experts, the experts could be divided into h groups, and the rough criteria weights of all h groups could be obtained using R-BWM. Moreover, the overall rough optimal weights of different groups could be integrated by assigning each group a relative importance as:

where \(\Phi _i\) denotes the relative importance of group i with \(\sum _{i=1}^h{\Phi _i}=1\), and \(\delta (\omega _j^i)\) is the rough optimal weight of criterion \(C_j\) obtained by group i.

To ensure the reliability of the pairwise comparisons, the consistency of each expert’s judgments is evaluated using the consistency ratio (CR). The CR is obtained by solving the optimization model of the BWM and reporting the optimal deviation \(\xi ^{*}\) as a consistency index, which is then normalized by the maximum allowable deviation \(\xi _{\max }\) according to the comparison scale. A smaller CR indicates more reliable and consistent judgments, and a value below 0.1 is generally considered acceptable.

The R-GLDS method

In this section, the rough GLDS (R-GLDS) method is introduced to assess and rank different alternatives using patients assessments. The basic idea of the R-GLDS method is to compare the dominance flow among different alternatives under each criterion. The procedures of the R-GLDS method are as follows:

Step 1: Obtain the initial matrix

Suppose that there are \(T'\) patients in the group of patients, n assessment criteria and m hemodialysis alternatives. The initial matrix representing the patients assessments is expressed as:

where \(h_{ij}^{k'}\) denotes the assessment of the ith hemodialysis alternative over the jth criterion provided by the \(k'\)th patient.

Step 2: Construct the rough matrix

The assessments provided by the patients are represented by linguistic terms, hence, the assessments of different patients could be converted into a rough number using Eq. (3). Correspondingly, the rough matrix could be constructed based on the initial matrix as:

where \(\delta (h_{ij}\) is represented by a rough number \([\underline{h}_{ij},\overline{h}_{ij}]\).

Step 3: Obtain the normalized rough matrix

Due to the differences in the value of different rough numbers, it is necessary to unify these assessments by setting their ranges between 0 and 1 using normalization. The rough matrix is normalized as:

where \(h_j^*=\max _i(h_{ij})\) is the positive ideal number of the jth criterion.

Step 4: Calculate weighted normalized rough matrix

By multiplying the criteria weights and the normalized rough matrix, the weighted normalized rough matrix that considers the relative importance of the criteria is obtained as:

Step 5: Calculate the dominance flow

For two different alternatives \(A_{p}\) and \(A_{q}\), \((p,q=1,2,\dots ,m)\), the integrated rough assessments of \(A_p\) and \(A_q\) under the jth criterion \(C_j\) are \(\delta (h_{pj}^*)\) and \(\delta (h_{qj}^*)\). The dominance flow of \(A_p\) and \(A_q\) under \(C_j\) is expressed by:

where \(d(\delta (h_{pj}^*),\delta (h_{qj}^*))\) is the distance measure between rough numbers \(\delta (h_{pj}^*)\) and \(\delta (h_{qj}^*)\).

Step 6: Obtain the normalized dominance flow

As several criteria are involved in the assessment, directly integrating dominance flows of different criteria could lead to biased results. Hence, it is necessary to normalize the dominance flow to set its range between 0 and 1. Considering the relative relation of different alternatives, the dominance flow is normalized using the vector normalization method as:

Step 7: Compute the net gained dominance score

The normalized dominance flow \(df_j^*(A_p,A_q)\) represents the degree to which \(A_p\) outranks \(A_q\) under \(C_j\), thus, by combining the normalized dominance flows of \(A_p\) over different alternatives under \(C_j\), the gained dominance score of \(A_p\) under criterion \(C_j\) could be obtained. Then, considering the weights of different criteria obtained by R-BWM, the overall gained dominance score of \(A_p\) could be computed by:

By comparing the values of \(DS_1\) of different alternatives, we can obtain the ranking order of these alternatives as \(R_1=\{r_1(A_1),r_1(A_2),\dots ,r_1(A_m)\}\), such that \(r_1(A_i)\) represents the ranking of \(A_i\).

Step 8: Compute the net lost dominance score

The net lost dominance score represents the negative performance of an alternative, which is calculated based on the maximum dominance flow that an alternative is inferior to other alternatives as:

It should be noted that based on the net lost dominance score, different alternatives could be ranked in ascending order of \(DS_2(A_p)\), and the ranking order could be obtained as \(R_2=\{r_2(A_1),r_2(A_2),\dots ,r_2(A_m)\}\).

Step 9: Calculate the integrated score

In order to obtain more reliable and comprehensive results, neither the net gained dominance score nor the net lost dominance score could effectively represent the performance of the alternative alone. Thus, the net gained and lost dominance scores are integrated to obtain the integrated score of the alternative as:

where \(DS_b^*(A_i)\) is the normalized value of \(DS_b(A_i)(b=1,2)\) such that \(DS_b^*(A_i)=\frac{DS_b(A_i)}{\sqrt{\sum _{i=1}^m{(DS_b(A_i))^2}}}\). According to descending order of \(IS_i\), the final ranking of the alternative \(R=\{r(A_1),r(A_2),\dots ,r(A_m)\}\) could be obtained.

The R-BWM-GLDS method

In order to better demonstrate the process of the R-BWM-GLDS method, its procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1 and Fig. 2.

Case study

In this section, a practical case study is presented to validate the proposed method and provide guidance for hemodialysis improvements. In Jinan, China, there are more than 10 hospitals that could provide hemodialysis for patients, including several well-known tertiary public hospitals such as Shandong Provincial Hospital, Qilu Hospital, and Qianfoshan Hospital. However, the feedbacks from patients vary, as some patients have come up with complaints. As uremia patients have to undergo hemodialysis every week, and usually have to spend several hours in the hemodialysis room, it is necessary to assess the satisfaction of patients to help identify possible improvements. However, how to assess the satisfaction of patients over the hemodialysis procedure. On the one hand, there are several hospitals that provide hemodialysis operations, with different patient satisfaction. On the other hand, prioritizing these hospitals according to patients assessments could help determine possible improvements for other hospitals. Therefore, we need to gather information from patients receiving hemodialysis operations from different hospitals. Aiming to analyze the patient satisfaction of different hospitals, we can help identify the most superior hospital with regard to patient experience and identify potential improvements.

In this study, five different hospitals are analyzed. For confidential reasons, the hospital’s name is not specified. In this case, the analyzed hospitals are denoted as Hospital A, Hospital B, Hospital C, Hospital D, and Hospital E.

The case study is investigated under several assumptions that clarify its scope and boundaries:

-

Patient linguistic evaluations are assumed to be reliably represented by rough numbers, allowing subjective and uncertain judgments to be captured directly from the original data without requiring predefined membership functions.

-

Patient responses are considered independent, such that each evaluation reflects an individual perception without systematic influence from others.

-

Experts providing pairwise comparisons in the BWM are assumed to be knowledgeable and capable of delivering consistent judgments.

-

The set of 13 criteria identified for the case study is assumed to comprehensively reflect the dimensions of patient satisfaction in hemodialysis.

Survey design and implementation

With the help of the above-mentioned hospitals, empirical surveys are conducted to gather information regarding patient satisfaction. A questionnaire with 13 questions, corresponding to the 13 criteria identified in Section 2, is used to gather information from patients. To facilitate the ambiguity and fuzziness in making judgments with regard to these criteria, a seven-level linguistic term set is used to provide possible options for the patients, namely, \(S=\{s_0=very\ bad,s_1=bad,s_2=slightly\ bad,s_3=moderate,s_4=slightly\ good,s_5=good,s_6=very\ good\}\). In order to maintain the reliability of the survey results, the survey is conducted over one week at different time, so that randomness could be achieved. Moreover, the patients are selected randomly from the patients in the hemodialysis operation room from each hospital, so the patients would have first-hand experience with the hemodialysis procedure. In order to ensure the integrity of this study, we conduct the survey independently from the hospital. For each studied hospital, we obtained substantial information about satisfaction with the hemodialysis experience from patients who are receiving the hemodialysis, and the collected assessments of the patients with respect to different criteria are listed in Table 1. For Hospital A, Hospital B, Hospital C, Hospital D, and Hospital E, 95, 104, 113, 87, and 102 valid questionnaires are collected, respectively.

Patient satisfaction based on R-BWM-GLDS

In this section, the R-BWM-GLDS method is adopted to assess the satisfaction of patients in different hospitals.

Step 1. Let five hospitals be expressed by alternatives \(A_1\), \(A_2\), \(A_3\), \(A_4\), and \(A_5\), respectively. The assessment criteria includes total waiting time (\(C_{11}\)), procedure before hemodialysis (\(C_{12}\)), instructions after hemodialysis (\(C_{13}\)), improvement of clinical outcome (\(C_{14}\)), patient privacy protection (\(C_{15}\)), arteriovenous fistula puncture comfort (\(C_{21}\)), service attitude (\(C_{22}\)), timely response from staff (\(C_{23}\)), emergency response (\(C_{24}\)), guide sign (\(C_{31}\)), order in the hemodialysis room (\(C_{32}\)), comfort of the hemodialysis room (\(C_{33}\)) and rescure equipment (\(C_{34}\)).

Step 2. Construct the expert group by inviting eight experts from different departments, namely neurology, quality control, and medical response departments, each with more than 10 years of experience. The experts are denoted as \(E=\{E_1,E_2,E_3,E_4,E_5,E_6,E_7\}\), respectively. The expert group is invited to determine the most important criterion and the least important criterion based on their knowledge and experience. Table 2 summarizes the best and worst criteria selected by these experts. Moreover, the experts are invited to evaluate the relative importance of the best criterion \(C_B\) to other criteria \(C_j\) using a scale of 1 to 9, where a higher number indicates greater relative importance. Similarly, the experts determined the relative importance of other criteria \(C_j\) to the worst criterion \(C_W\). The best-to-others and others-to-worst vectors are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

The judgments of each expert should pass the consistency test before the subsequent calculation. The CRs of the BWM survey completed by the experts are all less than 0.1, thus having acceptable consistency. As shown in Table 2, the best and worst criteria determined by the experts are different, which can be divided into three groups, namely \(G_1\), \(G_2\), and \(G_3\).

Step 3. Based on the rough number calculation method, the rough best-to-others and others-to-worst vectors of different groups are calculated by integrating the judgments of the experts, and the rough optimal criteria weights of different groups are obtained using Eq. (10), as listed in Table 5.

Step 4. For each alternative, a corresponding patient group is to assess the criteria using linguistic variables, and the assessments are listed in Table 1. Subsequently, the rough matrix (see Table 6) could be constructed based on the assessments of patients by using the rough number calculation method. Then, the rough matrix could be normalized using Eq. (14), and the weighted rough matrix could be obtained, as listed in Table 7.

In addition to calculating the criteria weights, the consistency ratios of the expert comparisons are evaluated. The CR values for all experts are below 0.1, which confirms that the pairwise comparisons are consistent and that the derived weights are reliable.

Step 5. Based on the weighted rough matrix, the dominance flows could be computed. Firstly, the dominance flows of each alternative pair under different criteria are calculated using Eq. (16), as shown in Table 8. It can be noted that the dominance flow exists if an alternative is superior to the other.

Then, the normalized dominance flow could be computed using Eq. (17), and the results are listed in Table 9.

By using Eqs. (18) and (19), the net gained and lost dominance scores, and the corresponding rankings, could be obtained, as shown in Table 10. Subsequently, the integrated score of each alternative could be calculated as \(IS_1=3.3658\), \(IS_2=2.1734\), \(IS_3=1.3908\), \(IS_4=0.9888\) and \(IS_5=-0.0466\). Thus, the overall ranking of all five hospitals with regard to patient satisfaction with the hemodialysis experience could be obtained as \(A_1\succ A_2\succ A_3\succ A_4\succ A_5\), which indicates that Hospital A has the highest satisfaction.

Comparison analysis

In order to validate the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed method, in this section, we apply two classical MCDM methods, namely, the rough TOPSIS (R-TOPSIS) method53 and the rough VIKOR (R-VIKOR) method54 to this case and compare the obtained results with the results of the proposed method.

R-TOPSIS approach

The main concept of the R-TOPSIS method is to find the optimal that is nearest to the best (positive ideal) solution and farthest to the worst (negative ideal) solution, and its procedures are as follows.

Let the weights of criteria be the ones obtained by the R-BWM, as shown in Table 4, and the obtained assessments of patients are the same. The same rough number integration, normalization, and weighting process are applied to the gathered assessments. Then, the positive ideal solution PIS and the negative ideal solution NIS could be determined by comparing the weighted normalized rough number as:

Then, the separation distance of each alternative to the PIS \(d_i^+\) and the NIS \(d_i^-\) could be computed using the distance measure \(d=\sum _{j=1}^n{\sqrt{((r_j^+-\underline{h}_{ij})^2+(r_j^+-\overline{h}_{ij})^2)/2}}\) as:

Based on the PIS and NIS separation distance among all alternatives, the relative closeness coefficient could be calculated to rank the alternatives using the following formula:

For the five alternatives, the relative closeness coefficient is obtained as \(RC_1=0.0224\), \(RC_2=0.0143\), \(RC_3=-0.0027\), \(RC_4=0.0116\), \(RC_5=-0.0457\), where larger relative closeness coefficient indicates better results. Therefore, the ranking of the alternatives is obtained as \(A_1\succ A_2\succ A_4\succ A_3\succ A_5\).

It can be noted that the results are different from the results of the proposed method, as the ranking of \(A_3\) and \(A_4\) has changed. This is contributed by the fact that the specific dominant relations among the alternatives are not considered in the calculation process, thus affecting the overall assessment of the alternatives.

R-VIKOR approach

The R-VIKOR method uses group utility and individual regret to determine the optimal solution that is with maximum group utility of the majority and minimum individual regret of the opponent.

For the R-VIKOR method, the rough weights of the criteria are retained from the results obtained using R-BWM, and the normalized rough matrix is constructed based on patients assessments. Similar to the R-TOPSIS method, the PIS and the NIS are obtained. Then, based on the normalized rough matrix, the rough group utility \([\underline{S}_i,\overline{S}_i]\) and the rough individual regret \([\underline{R}_i,\overline{R}_i]\) could be using the following formula:

Hence, the rough group utility and the rough individual regret of different alternatives are obtained as:

Subsequently, the rough compromise measure is obtained as:

where a smaller value indicates better results. Therefore, based on the values of Q, the alternatives could be ranked as \(A_2\succ A_1\succ A_4\succ A_3\succ A_5\). However, it should be noted that when considering the group utility and the individual regret, the ranking results are different, and only a compromise result is obtained, which affects the reliability of the result.

Analysis of the results

The ranking results obtained from the R-TOPSIS method, the R-VIKOR method, and the proposed R-BWM-GLDS method are illustrated in Fig. 3. Although the overall rankings produced by these three methods are generally similar, certain differences can be observed. In particular, the ranking of \(A_3\) and \(A_4\) differs: the proposed method places \(A_3\) above \(A_4\), whereas both R-TOPSIS and R-VIKOR assign \(A_3\) a lower position than \(A_4\). This discrepancy is mainly attributed to the simplified calculation processes of R-TOPSIS and R-VIKOR, which may not fully capture the performance trade-offs under uncertainty. By contrast, the proposed method not only generates the final rankings but also calculates the gained and lost dominance scores, enabling a more detailed evaluation of the alternatives. This additional information provides decision-makers with clearer insights into pairwise preferences under individual criteria, making the results more interpretable and actionable. From this comparison, it can be concluded that the proposed method offers more robust and reliable results than the R-TOPSIS and R-VIKOR methods.

Furthermore, based on the characteristics of the calculation processes, the following observations can be made:

(1) The proposed R-BWM-GLDS method employs gained and lost dominance scores to derive the final assessments and rankings of alternatives. This approach ensures that the alternatives are not only ordered according to their overall performance but also safeguarded against poor performance on specific criteria. As a result, the method produces more consistent and reliable outcomes than R-TOPSIS, which aggregates closeness measures without explicitly considering negative performance. Although R-VIKOR incorporates both group utility and individual regret in its formulation, the final results remain sensitive to changes in weights, which can reduce stability across scenarios.

(2) The proposed method provides the ability to compare alternatives criterion by criterion through the dominance flow analysis. This feature allows decision-makers to pinpoint the specific criteria that contribute to weaker performance and to prioritize areas requiring improvement. By contrast, both R-TOPSIS and R-VIKOR mainly provide an overall ranking of alternatives, with limited interpretability regarding individual criteria. Consequently, the R-BWM-GLDS method offers richer diagnostic information, which enhances its value for practical healthcare decision-making.

Results and discussion

In order to validate the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed method, we further conduct several sensitivity analysis and comparison analysis in this section.

Results analysis

To illustrate the superiority of the proposed R-BWM-GLDS method, various experiments are conducted for comparison based on the above case. Firstly, conventional BWM using crisp values (crisp BWM), fuzzy BWM (F-BWM) and rough AHP are used to calculate criteria weights for comparison with the proposed rough BWM. The criteria weights calculated by crisp BWM, fuzzy BWM, rough AHP and the proposed rough BWM are illustrated in Fig 4. From Fig 4, it can be found that all four methods have the same priority of the criteria weights, however, the values are different. The crisp BWM uses crisp numbers to represent the criteria weights without considering the subjectivity and uncertainty, whereas the fuzzy BWM, rough AHP and R-BWM use interval values to represent the criteria weights. The different ranges of the interval values express the differences in uncertainty due to the different approaches to handling subjectivity. It can be noted that the intervals show the uncertainty and vagueness in the criteria weight calculation process by different methods, where the rough AHP method and R-BWM use a flexible interval boundary, and F-BWM uses a fixed boundary based on the corresponding membership function. Due to the use of the membership function, additional subjective information is added in F-BWM, thus increasing its uncertainty. Moreover, the rough AHP requires 78 pairwise comparisons from experts while the R-BWM only needs 23 pairwise comparisons. Therefore, the R-BWM could more effectively model the subjective judgments of experts and reflect the true opinion of decision-makers with more objectivity while having fewer computations.

Based on the calculated criteria weights, C-BWM-GLDS, F-BWM-GLDS, and the proposed R-BWM-GLDS are compared to validate the overall performance. As shown in Fig. 5, the ranking results of C-BWM-GLDS are \(A_1 \succ A_2 \succ A_4 \succ A_3 \succ A_5\), whereas both F-BWM-GLDS and R-BWM-GLDS produce \(A_1 \succ A_2 \succ A_3 \succ A_4 \succ A_5\). The integrated scores of \(A_3\) and \(A_4\) under C-BWM-GLDS are very close, which explains the instability in their positions. Furthermore, F-BWM-GLDS uses crisp values in the GLDS step, leading to narrower intervals than R-BWM-GLDS. By contrast, R-BWM-GLDS allows the direct propagation of rough numbers through the entire procedure, maintaining more realistic ranges of uncertainty. Across all three methods, \(A_1\) emerges as the best-performing hospital, but the consistency and transparency of the R-BWM-GLDS results demonstrate its superior reliability.

Compared with fuzzy and intuitionistic fuzzy extensions, the use of rough numbers in the proposed method avoids reliance on arbitrary membership function definitions or auxiliary hesitation parameters, and instead derives interval bounds directly from expert and patient inputs. This feature reduces modeling bias, increases transparency, and provides a clearer interpretation of the inherent uncertainty. In terms of computational complexity, R-BWM also requires significantly fewer comparisons than rough AHP, reducing the burden on experts. In addition, the GLDS component enables both overall rankings and criterion-level dominance flow analysis, offering decision-makers richer diagnostic information than methods such as R-TOPSIS or R-VIKOR, which mainly provide aggregate results.

From these results and comparisons, it can be concluded that the proposed R-BWM-GLDS method not only determines the relative importance of criteria and the ranking of hospitals, but also does so with greater robustness, interpretability, and efficiency. The method converts crisp or linguistic judgments into rough numbers without loss of information, accommodates flexible interval ranges to represent varying levels of uncertainty, and enhances the objectivity of patient satisfaction assessment. These characteristics highlight the superiority of the R-BWM-GLDS framework over conventional crisp, fuzzy, or rough approaches in modeling subjectivity and uncertainty in healthcare decision-making.

Sensitivity Analysis

The robustness of the proposed R-BWM-GLDS framework is examined by perturbing two sets of input parameters: (i) the criteria weights obtained from the R-BWM, and (ii) the lower and upper approximation bounds of the rough numbers representing patient judgments. This analysis provides insight into whether the results depend critically on the model assumptions, namely that patient judgments can be reliably expressed using rough numbers and that expert-derived weights are reasonably consistent.

For the criteria weights, the values obtained from the R-BWM are perturbed within a range of \(\pm 10\%\) while maintaining normalization. In each perturbed scenario, the rankings of the five hospitals are recalculated and compared with the baseline order (Hospital 1 \(\succ\) Hospital 2 \(\succ\) Hospital 3 \(\succ\) Hospital 4 \(\succ\) Hospital 5). As shown in Fig. 6, the results show perfect stability: Hospital 1 and Hospital 5 always occupy the best and worst positions, with top-1 and bottom-1 stability of 100%. Hospitals 2, 3, and 4 also remain in the same positions across all 1000 trials. This outcome indicates that the framework is not sensitive to small deviations in expert weight judgments, which supports the assumption of expert consistency.

For the rough number bounds, the lower and upper approximation values are expanded or contracted by up to \(\pm 15\%\), subject to the validity condition (\(0 \le\) lower \(\le\) upper \(\le 1\)). As shown in Fig. 7, across 1000 perturbed scenarios, the baseline order remains essentially unchanged. Hospital 1 retains the top position in 99.6% of cases, with Hospital 2 occasionally rising to first place (0.4%). Hospital 5 is consistently ranked last. Limited fluctuations occur among the intermediate hospitals: Hospital 2 is second in 97.9% of scenarios and third in 1.7%; Hospital 3 is third in 93.8% and fourth in 4.5%; Hospital 4 is fourth in 95.5% and third in 4.5%. These localized shifts confirm that the conclusions are robust to reasonable deviations in patient judgments, consistent with the assumption that rough numbers provide a reliable representation of linguistic evaluations.

Overall, the sensitivity analysis shows that the best and worst hospitals remain stable across all perturbation scenarios, while only minor reordering is observed among the middle-ranked hospitals. These results indicate that the R-BWM-GLDS framework produces stable and interpretable outcomes even when expert weights or patient assessments vary within plausible ranges.

First, the weights obtained from the R-BWM were systematically perturbed within a range of \(\pm 10\%\) while maintaining normalization. The resulting rankings showed no changes in the top-ranked and bottom-ranked hospitals, while only minor shifts were observed among the mid-ranked hospitals. This suggests that the relative importance of criteria does not critically alter the main decision outcomes, thereby confirming the stability of the weighting procedure.

Second, the lower and upper approximation bounds of the rough numbers were expanded and contracted by up to \(\pm 15\%\) to simulate variability in patient linguistic judgments. Similar to the weight perturbation analysis, the rankings of the best and worst hospitals remained unchanged across all tests. Although some intermediate hospitals exhibited rank fluctuations, the differences were small and did not affect the overall decision validity.

Taken together, the sensitivity analysis demonstrates that the R-BWM-GLDS framework produces stable and reliable results under a range of plausible variations in input data. The robustness of the method is particularly important in healthcare service evaluation, where judgments are inherently subjective and uncertain, yet decision-makers require confidence in the resulting prioritizations.

Discussion

In this study, the assessment of patient satisfaction with the hemodialysis experience is investigated, and we try to provide answers to three research questions, specifically,

RQ1: What are the factors that could affect the satisfaction of the patients toward the hemodialysis experience, and to which degree would these factors affect the overall patient satisfaction?

RQ2: How to model the linguistic and uncertain judgments collected from the patients receiving the hemodialysis without scarifying the accuracy and reliability of the results?

RQ3: How to integrate the collected judgments of different hospitals on the factors to determine the preference and ranking of different hospitals with regard to hemodialysis experience satisfaction?

Through this study, the following conclusions could be drawn for these research questions:

-

(1)

For RQ1, like other decision-making problems, the identification and prioritization of the assessment criteria are mainly a subjective process. That is, experienced experts are invited to provide information on which factors should be considered and the importance of these factors, and subjective weight calculation method is needed for criteria weight calculation. Compared with other subjective weight calculation methods, BWM could achieve higher consistency with less computation, and is used in this study. As seen from the comparative results, R-BWM used in this study could effectively determine the weights of different criteria. Hence, this study provides an effective way to identify and weigh factors that affect the satisfaction of the patients toward the hemodialysis experience.

-

(2)

For RQ2, as the judgments of the patients are gathered through questionnaire, linguistic terms are often used by the patients. Hence, it requires an effective method to gather and aggregate the judgments of different patients. Rough number, as a useful knowledge representation method, is well-suited to aggregate and represent the judgments of hundreds of experts, and it is used to represent the linguistic information from the patients in this study. As shown in the results, by introducing rough number to represent patients judgments, the proposed method could more accurately and flexibly reflect the actual opinion of different patients.

-

(3)

For RQ3, many MCDM methods could be used to assess and rank different alternatives. However, the GLDS method is unique for its ability to reflect both the overall performance and the individual performance of each alternative, so that the selected alternative is guaranteed to be optimal from different standpoints, whereas in patient satisfaction assessment problem, the best alternative should be able to perform well on all criteria. As shown in the case study, compared with other typical MCDM methods, the proposed method could provide reasonable ranking results. Hence, the GLDS method is an effective way to solve the patient satisfaction assessment problem.

Implications

This study provides several important implications for healthcare service management, particularly in the context of hemodialysis. As most uremia patients require treatment several times per week, a positive hemodialysis experience can help alleviate anxiety and improve quality of life. A reliable patient satisfaction assessment framework is therefore critical for ensuring continuous quality improvement and for supporting evidence-based hospital management.

First, the determination of weights for the 13 identified criteria offers valuable guidance for managers. These weights reflect the relative importance of different aspects of patient satisfaction, such as waiting time, staff responsiveness, and treatment environment, and can help hospital administrators allocate resources more effectively. By highlighting which criteria are most influential from the perspective of patients, the results provide clear priorities for managerial attention.

Second, the calculation of dominance flows enables criterion-level insights into hospital performance. Beyond the overall rankings, hospitals can identify their strengths and weaknesses under each criterion and implement targeted improvements. For example, if a hospital performs poorly under the criterion of timely staff response, managers can introduce training or process redesigns to address this gap. This diagnostic capability adds practical value that goes beyond simple ranking outcomes and supports continuous service improvement.

Third, the confirmation of the research hypothesis carries both theoretical and practical significance. The integration of rough numbers with BWM and GLDS is shown to yield reliable and interpretable results, consistent with expert expectations and alternative validation methods. Importantly, the sensitivity analysis demonstrates that the top- and bottom-ranked hospitals remain unchanged under perturbations of both weights and rough bounds, while only minor variations occur among mid-ranked hospitals. This robustness reassures hospital managers that the conclusions drawn from the model are not unduly sensitive to small fluctuations in patient or expert inputs. By explicitly linking the findings to the key assumptions of the model, the analysis further clarifies the conditions under which the framework is applicable and trustworthy.

Taken together, these implications suggest that the proposed R-BWM-GLDS method not only advances methodological development in multi-attribute decision-making under uncertainty but also provides hospital managers with a practical, transparent, and reliable tool for evaluating patient satisfaction. The framework can guide strategic resource allocation, support benchmarking among hospitals, and ultimately contribute to the delivery of more patient-centered healthcare services.

In general, this study could not only assess and rank different hospitals with regard to patient satisfaction with the hemodialysis experience, but also provide references for future improvements based on the dominance flows. It is also worth noting that though the study is conducted with five hospitals in Jinan, China, the proposed method could be broadly applied to different situations.

Conclusion

Patient satisfaction is a major goal for hospitals, and its proper assessment could help enhance the communication between patients and hospitals, thus helping to improve the quality of medical services and to establish a more harmonious relationship between doctors and patients. However, the patient satisfaction assessment problem is a complex MAGDM problem that involves both subjectivity and uncertainty, and current studies often fail to properly model the subjective and uncertain information. Motivated by these limitations, this paper proposes an integrated MAGDM method, called R-BWM-GLDS to assess patient satisfaction with the hemodialysis experience. The rough number is used to represent the linguistic judgments of decision-makers under subjectivity and uncertainty. Then, the R-BWM, where the preference information of experts is expressed by rough numbers, is used to determine the weights of different criteria, and the R-GLDS method is used to assess patient satisfaction. Considering the factors that affect patient satisfaction during the hemodialysis experience, a criterion system is constructed based on literature analysis and empirical analysis. Given the fact that patient satisfaction could be used to assess the performance of hospitals and identify possible improvements, five hospitals from Jinan China are selected to conduct experimental study to test the proposed method. The patient satisfaction with regard to the hemodialysis experience of the five hospitals is analyzed, and the hospitals are ranked according to patient satisfaction. It is determined that Hospital A has the highest patient satisfaction among all five hospitals. In addition, the effectiveness and feasibility of the proposed method are further validated through comparison analysis. The findings of this study confirm the research hypothesis. The integration of rough numbers with BWM and GLDS yields a decision-making framework that produces reliable and interpretable rankings of hospitals. The robustness of the results, as shown by both comparative analysis and sensitivity analysis, highlights the value of the R-BWM-GLDS method for practical healthcare service evaluation.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized into two parts. Firstly, with regard to the theoretical aspect, this study proposes the R-BWM-GLDS method for MAGDM problems under subjectivity and uncertainty, which provides a novel and effective way for weight calculation and alternative ranking. In addition, the performance of alternatives under each criterion could be obtained based on the dominance flow, thus enabling more practical and effective improvements. Secondly, with regard to the practical aspect, we establish a comprehensive criteria system for assessing patient satisfaction with hemodialysis experiences for the first time, which could help lay the foundation for future research. More importantly, a practical case is studied using the proposed method, as five hospitals from Jinan China are analyzed and ranked with regard to patient satisfaction with hemodialysis experiences, which could help hospital managers identify possible improvements. In conclusion, this study provides a novel and feasible way for assessments in the healthcare sector, and it could be applied to other similar problems such as hospital service assessment and doctor performance evaluation.

Importantly, the findings of this study confirm the research hypothesis that combining rough numbers with BWM and GLDS enhances the robustness and interpretability of patient satisfaction assessment. The proposed framework not only produced consistent results across comparative and sensitivity analyses but also offered more transparent insights by balancing overall performance with worst-case performance. This validation demonstrates that the R-BWM-GLDS method is both theoretically sound and practically applicable for healthcare decision-making.

Despite these contributions, certain limitations remain. For instance, methods for incorporating group consensus into the framework require further exploration, and the adaptability of the proposed approach could be enhanced to support broader applications.

Future research can extend this work in several directions. First, applying the framework to other healthcare services, such as surgical recovery or outpatient care, would broaden its relevance and test its adaptability. Second, incorporating alternative uncertainty models, such as intuitionistic fuzzy sets or probabilistic linguistic fuzzy sets, may increase flexibility in representing diverse forms of subjective judgment. Third, integrating big data from electronic health records and real-time patient monitoring could improve both scalability and timeliness, thereby enabling dynamic satisfaction assessment in practice. Finally, conducting cross-cultural studies would help test the generalizability of the criteria system and reveal differences in patient expectations across healthcare contexts. Together, these directions highlight the potential for the R-BWM-GLDS framework to evolve into a more versatile tool for decision-making and evaluation in healthcare service management.

Data Availability

The datasets used in this study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ming, Y. et al. Managing patient satisfaction in a blood-collection room by the probabilistic linguistic gained and lost dominance score method integrated with the best-worst method. Comput Ind Eng 145, 106547 (2020).

Liang, J. et al. The experience and challenges of healthcare-reform-driven medical consortia and regional health information technologies in china: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Med. Inf 131, 103954 (2019).

Adhikary, G. et al. Factors influencing patients’ satisfaction at different levels of health facilities in Bangladesh: Results from patient exit interviews. PLoS ONE 13, e0196643 (2018).

Goodrich, G. W. & Lazenby, J. M. Elements of patient satisfaction: An integrative review. Nurs. Open 10, 1258–1269 (2023).

Cai, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, S., Wang, C. & Jiang, Y. A cross-sectional study on the relationship between length of stay and patient satisfaction based on the servqual model. Sci. Rep. 15, 5605 (2025).

Fatima, T., Malik, S. A. & Shabbir, A. Hospital healthcare service quality, patient satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation in context of private healthcare systems. Int J Qual Reliab Manag 35(6), 1195–1214 (2018).

Ferreira, D. C., Vieira, I., Pedro, M. I., Caldas, P. & Varela, M. Patient satisfaction with healthcare services and the techniques used for its assessment: A systematic literature review and a bibliometric analysis. Healthcare 11, 639 (2023).

Mai, S., Chang, L., Xu, R. H., Su, S. & Wang, D. Doctor interaction behavior, patient participation in value co-creation and patient satisfaction: Cross-sectional survey in a tertiary-level hospital from guangzhou, china. Sci. Rep. 14, 23025 (2024).

Manzoor, F., Wei, L., Hussain, A., Asif, M. & Shah, S. I. A. Patient satisfaction with health care services; an application of physician’s behavior as a moderator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 3318 (2019).

Ramaswamy, A. et al. Patient satisfaction with telemedicine during the Covid-19 pandemic: Retrospective cohort study. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e20786 (2020).

Lotfi, M., Zamanzadeh, V., Valizadeh, L. & Khajehgoodari, M. Assessment of nurse-patient communication and patient satisfaction from nursing care. Nurs. Open 6, 1189–1196 (2019).

Fathollahi-Fard, A. M., Ahmadi, A., Goodarzian, F. & Cheikhrouhou, N. A bi-objective home healthcare routing and scheduling problem considering patients’ satisfaction in a fuzzy environment. Appl. Soft Comput. 93, 106385 (2020).

Javed, S. A., Liu, S., Mahmoudi, A. & Nawaz, M. Patients’ satisfaction and public and private sectors’ health care service quality in Pakistan: Application of grey decision analysis approaches. Int. J. Health Plann. Manage. 34, e168–e182 (2019).

Bani-Doumi, M., Serrano-Guerrero, J., Chiclana, F., Romero, F. P. & Olivas, J. A. A picture fuzzy set multi criteria decision-making approach to customize hospital recommendations based on patient feedback. Appl. Soft Comput. 153, 111331 (2024).

an observational study. Al Hayek, A. A., Al-Saeed, A. H., Alzahrani, W. M. & Al Dawish, M. A.,. Assessment of patient satisfaction with on-site point-of-care hemoglobin a1c testing. Diabetes Therapy 12, 2531–2544 (2021).

Garvin, P. L. On linguistic method. In On Linguistic Method (De Gruyter Mouton, 2019).

Liao, H., Jiang, L., Lev, B. & Fujita, H. Novel operations of PLTSS based on the disparity degrees of linguistic terms and their use in designing the probabilistic linguistic electre iii method. Appl. Soft Comput. 80, 450–464 (2019).

Gao, F. An integrated multi criteria decision making method using dual hesitant fuzzy sets with application for unmanned aerial vehicle selection. Sci. Rep. 15, 12637 (2025).

Borujeni, M. P., Behzadipour, A. & Gitinavard, H. A dynamic intuitionistic fuzzy group decision analysis for sustainability risk assessment in surface mining operation projects. J Sustain Mining 24, 15–31 (2025).

Gitinavard, H., Ghaderi, H. & Pishvaee, M. S. Green supplier evaluation in manufacturing systems: A novel interval-valued hesitant fuzzy group outranking approach. Soft. Comput. 22, 6441–6460 (2018).

Zhu, G.-N., Hu, J., Qi, J., Gu, C.-C. & Peng, Y.-H. An integrated AHP and Vikor for design concept evaluation based on rough number. Adv. Eng. Inform. 29, 408–418 (2015).

Akram, M., Zahid, S. & Deveci, M. Enhanced critic-regime method for decision making based on Pythagorean fuzzy rough number. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 122014 (2024).

Song, J., Jiang, L., Liu, Z., Leng, X. & He, Z. Selection of third-party reverse logistics service provider based on intuitionistic fuzzy multi-criteria decision making. Systems 10, 188 (2022).

Zheng, P., Xu, X. & Xie, S. Q. A weighted interval rough number based method to determine relative importance ratings of customer requirements in qfd product planning. J. Intell. Manuf. 30, 3–16 (2019).

Zhu, Y., Tian, D. & Yan, F. Effectiveness of entropy weight method in decision-making. Math Probl Eng. 2020(1), 3564835 (2020).

Al-Harbi, K.M.A.-S. Application of the AHP in project management. Int. J. Project Manage. 19, 19–27 (2001).

Alqahtani, F. M. & Noman, M. A. An integrated fuzzy Delphi and fuzzy AHP model for evaluating factors affecting human errors in manual assembly processes. Systems 12, 479 (2024).

Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 53, 49–57 (2015).

Gao, F., Han, M., Wang, S. & Gao, J. A novel Fermatean fuzzy bwm-vikor based multi-criteria decision-making approach for selecting health care waste treatment technology. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 127, 107451 (2024).

Vaezi, A., Rabbani, E. & Yazdian, S. A. Blockchain-integrated sustainable supplier selection and order allocation: A hybrid bwm-multimoora and bi-objective programming approach. J. Clean. Prod. 444, 141216 (2024).

Ji, C., Gao, F. & Liu, W. Dependence assessment in human reliability analysis based on cloud model and best-worst method. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 242, 109770 (2024).

Gao, F. & He, W. Pathway to smart aviation: Identifying and prioritizing key factors for smart aviation development using the fuzzy best-worst method. Systems 13, 291 (2025).

Hafezalkotob, A. & Hafezalkotob, A. A novel approach for combination of individual and group decisions based on fuzzy best-worst method. Appl. Soft Comput. 59, 316–325 (2017).

Wan, S. & Dong, J. A novel extension of best-worst method with intuitionistic fuzzy reference comparisons. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst 30(6), 1698–1711 (2021).

Lin, M., Huang, C., Xu, Z. & Chen, R. Evaluating IoT platforms using integrated probabilistic linguistic MCDM method. IEEE Internet Things J. 7, 11195–11208 (2020).

Chen, Y.-L., Shen, S.-L. & Zhou, A. Assessment of red tide risk by integrating critic weight method, topsis-assets method, and monte Carlo simulation. Environ. Pollut. 314, 120254 (2022).

García Mestanza, J. & Bakhat, R. A fuzzy AHP-mairca model for overtourism assessment: The case of Malaga province. Sustainability 13, 6394 (2021).

Zhang, C., Chen, C., Streimikiene, D. & Balezentis, T. Intuitionistic fuzzy multimoora approach for multi-criteria assessment of the energy storage technologies. Appl. Soft Comput. 79, 410–423 (2019).

Becerra, C. E. T. et al. A holistic quality improvement model for food services: Integrating fuzzy kano and promethee II. Systems 12, 422 (2024).

Wu, X. & Liao, H. A consensus-based probabilistic linguistic gained and lost dominance score method. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 272, 1017–1027 (2019).

Liang, X., Wu, X. & Liao, H. A gained and lost dominance score ii method for modelling group uncertainty: Case study of site selection of electric vehicle charging stations. J. Clean. Prod. 262, 121239 (2020).

Wu, M., Ma, S. & Fan, J. A spherical z-number multi-attribute group decision making model based on the prospect theory and GLDS method. Complex Intell Syst 10, 8501–8524 (2024).

Wu, X. & Liao, H. A gained and lost dominance score method with conflict analysis for green economy development evaluation. Ann. Oper. Res. 316, 623–655 (2022).

Wang, W.-Z., Liu, X.-W. & Liu, S.-L. Failure mode and effect analysis for machine tool risk analysis using extended gained and lost dominance score method. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 69, 954–967 (2019).

Liao, H., Chang, J., Zhang, Z., Zhou, X. & Al-Barakati, A. Third-party cold chain medicine logistics provider selection by a rough set-based gained and lost dominance score method. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 22, 2055–2069 (2020).

Nazarian-Jashnabadi, J., Rahnamay Bonab, S., Haseli, G., Tomaskova, H. & Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. A dynamic expert system to increase patient satisfaction with an integrated approach of system dynamics, ISM, and ANP methods. Expert Syst. Appl. 234, 121010 (2023).

Gitinavard, H., Moosavi, S. M., Vahdani, B. & Ghaderi, H. A new decision making method based on hesitant fuzzy preference selection index for contractor selection in construction industry. Ind Manag Stud 15, 121–144 (2017).

Gitinavard, H., Mousavi, S. M., Vahdani, B. & Siadat, A. Project safety evaluation by a new soft computing approach-based last aggregation hesitant fuzzy complex proportional assessment in construction industry. Sci Iran 27, 983–1000 (2020).