Abstract

Patients with significant primary mitral regurgitation (MR) can develop left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction (DD). We sought to study LV structural correlates, and prognostic significance of DD. Patients with ≥ moderate primary MR with echocardiographic and CMR scans within a median time of 5 days were included. LV volumes, EF, MR volume and fraction, presence of scar, and extracellular volume (ECV) were assessed by CMR. LV diastolic function (DF) was assessed by echocardiography using time delay between onset of mitral E velocity and mitral annulus e’ velocity, deceleration time of mitral E velocity, and duration difference between pulmonary vein atrial velocity and mitral A velocity. DF score was computed based on these 3 variables. Event rate (heart failure hospitalizations, cardiovascular death, or mitral valve surgery) was higher in patients with DD versus patients with normal DF (P < 0.05). MR volumes, and ECV were significantly higher in patients with DD (P < 0.001). In multivariable cox proportional hazard model, inclusion of DF score increased AUC from 0.83 to 0.86. Thus, DD is associated with ECV, MR severity, and clinical outcomes. DD score provides incremental value for the prediction of adverse outcomes when added to clinical characteristics, MR severity, and LV end diastolic volume index.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mitral regurgitation and myocardial abnormalities

Primary mitral regurgitation (MR) is an organic disease of the mitral valve apparatus, and up to 20% of asymptomatic patients experience mortality or heart failure hospitalization within 10 years of their diagnosis1. The most common etiology is degenerative, including myxomatous degeneration and fibroelastic deficiency disease2. Significant chronic primary MR has profound effects on cardiac structure and function, as the left atrial volume overload leads to its dilation and the eventual rise in its pressure when compensatory mechanisms fail, with invasive studies relating MR regurgitant fraction to wedge pressure3. The left ventricle (LV) is also subjected to volume overload which induces structural changes. A study including 86 primary MR patients showed the presence of patchy fibrosis on LV myocardial biopsy even in asymptomatic patients4. Additionally, a recent review of pathological studies on mitral valve prolapse found a high proportion of patients (up to 82%) had LV replacement fibrosis, with the most common site being the inferobasal myocardial segment (5). Recent CMR studies reported an increase in late-gadolinium enhancing lesions as well as expanded extracellular volume fraction (ECV), which was correlated with the severity of MR4,5. Further, these structural changes were associated with adverse events6. While these structural abnormalities are the substrate for LV myocardial dysfunction, the clinical relevance of LV diastolic dysfunction in patients with primary MR remains elusive.

Diastolic dysfunction is associated with adverse outcomes in several patient populations7,8. Its significance in primary MR has not been fully elucidated, due to the challenges in the noninvasive assessment of diastolic function in patients with primary MR and normal LV ejection fraction (EF). A multicenter study found the group of primary MR patients with increased LV volumes had similar outcomes (total number of events in the study was 60 events of surgery for MR or cardiovascular death) to those with preserved LV size but abnormal annular early diastolic velocity (e’) and peak tricuspid regurgitation (TR) velocity9. Of note, e’ velocity is directly related to MR volume in patients with primary MR, and E/e’ ratio is not related to left atrial (LA) pressure in this group of patients with primary MR and normal LV EF10. TR velocity can be taken as a surrogate of LA pressure but has no direct relation to LV diastolic function and can be increased due to the rise in LA and not LV diastolic pressures. In comparison with the above measurements, there are echocardiographic signals that have a direct relation with LV relaxation, LV stiffness, and LV end diastolic pressure (EDP). For LV relaxation, the time delay between the onset of mitral peak early diastolic (E) velocity and onset of e’ velocity is directly related to the time constant of LV relaxation10,11,12. When LV relaxation is normal, LV expansion in the long axis precedes mitral inflow such that onset of e’ velocity precedes or occurs at the same time as mitral E velocity. With impaired LV relaxation e’ velocity is delayed such that it occurs after the development of the peak early diastolic trans-mitral pressure gradient11, and thus mitral E velocity occurs before annular e’ velocity11,12. Deceleration time (DT) of mitral E velocity has a strong correlation with LV chamber stiffness constant in animal models of heart failure and in patients with cardiac disease13,14. Finally, the time difference between the duration of pulmonary vein atrial velocity and that of mitral A velocity has a direct relation with LV EDP and is not affected by MR by itself as MR volume affects early but not late diastolic events15.

Therefore, we sought to investigate the relationship between the above direct indices of LV diastolic function and LV structural changes in patients with primary MR. We also examined the association of LV diastolic function by these specific signals and the outcomes of cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization and mitral valve repair or replacement.

Methods

Patient population

Patients undergoing CMR for assessment of chronic MR at Houston Methodist Hospital (Houston, TX) from 2011 to 2022 were enrolled in a prospective observational registry16. Patients with at least moderate MR (defined by CMR value for MR regurgitant fraction > 30% or regurgitant volume > 30 mL) were identified and included in the analysis. Only patients with primary MR were included and all other cardiovascular diseases were excluded including CAD, cardiomyopathies, amyloidosis, previous cardiac surgery, congenital heart disease, LV EF < 50%, or coexisting valvular disease greater than mild severity. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Houston Methodist Research Institute, and patients provided informed consent. Imaging and data collection were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Echocardiographic imaging and analysis

Parasternal, apical, and subcostal views were acquired using multifrequency transducers. Pulmonary vein flow, mitral inflow at level of mitral annulus and tips, and hepatic vein flow were recorded using Pulsed wave Doppler. Continuous wave Doppler was used to record isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT) with the sample volume midway between LV outflow tract and mitral valve tips, and tricuspid regurgitation (TR) velocity from multiple windows. Intravenous injection of saline and ultrasound enhancing agents were utilized as needed to obtain complete TR jet. Pulsed wave tissue Doppler was applied to record mitral annulus velocities at septal and lateral sides of the mitral annulus. Sweep speed was 100 mm/s. Echocardiographic measurements were the average of three beats in patients in sinus rhythm, and the average of five beats in patients in atrial fibrillation.

Measurements were not taken from clinical reports but were performed at a later date by investigators without knowledge of CMR findings or clinical outcomes. Biplane left atrial (LA) maximum volume index, and inferior vena cava (IVC) maximum diameter and its change with spontaneous respiration and sniffing were noted. Mitral inflow (tips level) was analyzed for peak E and A velocities, E/A ratio, deceleration time (DT) of mitral E velocity, and mitral A duration was measured at mitral annulus level. The duration of pulmonary vein Ar velocity was measured as well as the difference between its duration and that of mitral A velocity: (Ar-A) duration. IVRT was obtained as the time interval between aortic valve closure and mitral valve opening. Right atrial pressure (RAP) was estimated based on IVC size and its collapse along with hepatic vein flow17. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure was estimated as: 4 (peak TR velocity in m/s)2 + RAP17.

Annular e’ velocity was measured at the septal and lateral sides of the mitral annulus and the average E/e’ ratio was computed. The time interval between the peak of the R wave and the onset of mitral E velocity, as well as the time interval between the peak of the R wave and the onset of e’ velocity at septal and lateral sides of the mitral annulus, were measured. R-R intervals within 10 ms were selected for timing the onset of mitral E and the onset of e’ velocity. The average time delay TE-e’ was then computed10,12. The interobserver variability for measuring TE-e’ is 5 ± 2%. The ratio of IVRT to TE-e’ was obtained as a surrogate of LA pressure10,12. Abnormal TE-e’ duration was defined by time difference > 11 ms based on mean + 2SD of values seen in normal subjects12, short DT was defined as ≤ 150 ms18, and abnormally prolonged Ar-A duration was defined as ≥ 30 ms18.

A composite score of LV diastolic function was obtained by assigning one point to each of TE-e’, DT, and Ar-A duration (score range 0 to 3). A value of 1 for a given variable was assigned if the measurement at least met the cutoff bar. If the cutoff bar was not met, a value of zero was assigned to the variable. In computing the score, if a measurement could not be obtained, its value was taken as zero and the score was the sum of the 2 other measurements that could be performed. In patients with atrial fibrillation, only TE-e’ and DT were used to derive the score.

CMR imaging and analysis

Patients underwent CMR scans on either a 1.5-Tesla or a 3.0-Tesla clinical scanner (Siemens Avanto or Verio, respectively; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with phased-array receiver coil systems. Imaging protocols included ECG gated cine and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging. Patients also underwent modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) sequences for T1 mapping just prior to and 15 min after contrast administration. Cardiac cines were acquired with a steady-state free precession sequence (SSFP) using sequential short-axis stacks (i.e., ventricular base to apex) with 10-mm increments (6-mm thickness, 4-mm gap) and standard cardiac long-axis views (i.e., left ventricular [LV] based 3-, 4-, and 2-chamber views). Cardiac chamber parameters were measured and indexed for body surface area. MR volume was computed as: (LV EDV -LV ESV) – flow through the aortic root.

LGE images were acquired over slice positions matched to cines about 10–15 min following intravenous gadolinium-based contrast administration (gadopentetate dimeglumine, gadoterate meglumine; 0.15 mmol/kg). LGE images were obtained using inversion-recovery gradient echo sequences with inversion times set to null myocardial tissue signal (inversion time [TI] 250–350 ms). The presence and extent of myocardial LGE, a measure of replacement fibrosis or scar tissue, was assessed using the AHA 17-segment model by level III trained CMR readers independently of ECV analysis results. For each myocardial segment, the extent of regional LGE was scored according to the spatial extent of LGE within each segment (0 = no LGE; 1 = 1%–25%; 2 = 26%–50%; 3 = 51%–75%; and 4 = 76%–100%). The total scar burden for the entire left ventricle was expressed as a percentage of LV myocardial volume and derived by averaging the score for all 17 segments.

T1 mapping and ECV

An ECG-gated MOLLI sequence with SSFP image readout with motion correction was performed at a representative mid short-axis view of the left ventricle at two distinct time points within a CMR scan: once following cine imaging but prior to contrast administration (pre-contrast), and once ~ 15 min following LGE imaging (post-contrast). The mid short-axis was chosen due to concerns with partial volume due to through-plane cardiac motion near the base and near the apex. The pre-contrast MOLLI acquisition was performed using a 5(3)3 sampling scheme, and the post-contrast acquisition used a 4(1)3(1)2 sampling scheme.

A single reader (blinded to all clinical, other CMR and echocardiographic measurements) post-processed all cases in randomized order and measured T1 values for ECV calculations. ECV was assessed for the mid septum (excluding areas with replacement fibrosis) at the same location for pre- and postcontrast. ECV was calculated as (1 – Hct) × (ΔR1myocardium / ΔR1blood), where Hct is the hematocrit level and ΔR1 represents the change in T1 relaxivity (R1 = 1/T1) before and after gadolinium-based contrast administration.

Outcomes

Prospective follow-up was conducted through phone interviews with the participants, and review of electronic health records (EHR). The primary endpoint was a composite of first occurrence to a heart failure hospitalization, death from cardiovascular causes, or mitral valve surgery following the baseline CMR scan. Heart failure hospitalization was defined as any hospitalization with a primary diagnosis of heart failure where the patient has a length of stay of at least 24 h, with symptoms and objective evidence of new or worsening heart failure, and initiation or intensification of heart failure therapies as documented in the hospital course or discharge summary by the admitting physician. Deaths and cause of death were ascertained from EHR review and/or National Death Index query. Mitral valve surgery included valve repair and valve replacement.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables in demographic, clinical and imaging data are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR) or mean and standard deviation depending on whether data had a normal distribution. Categorical variables are reported as number and percentage of observations. For continuous variables without a normal distribution, overall difference between groups was tested using the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed post-hoc by the Dunn test for pairwise comparison in case of significance. For normally-distributed continuous variables, one-way ANOVA was performed, followed post-hoc by the Holm-Sidek test for pairwise comparison in case of significance. For categorical variables, the difference between groups was tested using Chi-squared for variables with at least 5 observations in each “diastolic function score” group, and Fisher’s exact test otherwise. The cox proportional hazard model was first used for univariate analysis to determine which demographic, clinical, and imaging variables are associated with the outcome. Before use, the proportional hazard assumption was confirmed using the Schoenfeld Residuals Test which returned a p-value of 0.46. Variables for the multivariable cox proportional hazard model were selected based on clinical significance (e.g. age, sex, comorbidities) and univariate association with outcome (e.g. Indexed LV end-diastolic volume). Model discrimination was checked by the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUC), and model calibration was confirmed with the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, where p > 0.05 pointed to good model calibration. To balance model fit and complexity, the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was used for probabilistic model selection. A lower BIC indicates a better-fitting model while penalizing unnecessary complexity. A difference in BIC of less than 2 is considered non-significant, a difference of 2–5 indicates significant evidence favoring the model with the lower BIC, a difference of 5–10 suggests strong evidence, and a difference greater than 10 indicates very strong evidence favoring the model with the lower BIC19. Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analysis, and a P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study included 173 primary MR patients with a regurgitant fraction ≥ 30%, enrolled between 5/10/2011 and 4/4/2022. Mean age was 63 years and 53% were males. The median duration between echocardiography and CMR was 5 days (interquartile range: 0–15 days). Among the included patients, 129 cases were attributed to mitral valve prolapse (MVP), 24 to degenerative changes, 5 to rheumatic heart disease, 4 to infective endocarditis, and 11 to unspecified etiologies. Of the MVP cases, 17 were due to anterior leaflet prolapse, 78 to posterior leaflet prolapse, and 34 to bileaflet prolapse. Median follow-up time for the study was 70.4 months (IQR 10.2 – 88.1 months), during which 5 patients died due to cardiovascular causes, 8 were hospitalized for heart failure, and 119 underwent mitral valve surgery. Accounting for overlap in events, 123 patients out of 173 (71.1%) had at least one event.

Diastolic function relation to clinical and imaging findings

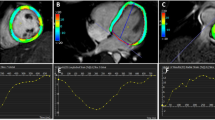

Out of 173 patients, 54 (31.2%) showed evidence of myocardial scarring. The basal inferolateral segment accounted for the largest proportion of scars (38%), followed by the basal inferior segment (11%), and the basal anterolateral, inferoseptal, and anteroseptal segments, each contributing 10%. Notably, none of the patients had subendocardial scarring or signs of myocardial infarction. Table 1 presents the summary of demographic and clinical findings according to the diastolic function score. Event rate was significantly higher in patients with diastolic dysfunction when compared to patients with normal diastolic function and it was highest in patients with a score of 3. Table 2 presents the summary of echocardiographic findings according to the diastolic function score. Expectedly, indices of LV diastolic function were significantly different between patients with diastolic dysfunction and the normal group with progressive abnormalities seen from score 1 to score 3. Table 3 presents the summary of CMR findings according to the diastolic function score. There was no significant difference in LV EF, prevalence of scar, or LV mass between patients with diastolic dysfunction and patients with normal diastolic function. However, MR volumes and fraction and ECV were significantly higher in patients with diastolic dysfunction. Figure 1 shows echocardiographic and CMR findings from a patient with normal diastolic function, and Fig. 2 displays these findings for another patient with diastolic dysfunction and a score of 3. Figure 3 shows the whisker plots for ECV in patients who met the cutoff value defining diastolic dysfunction for each of the three components of the score versus those who did not meet the cutoff value. In addition, ECV was also significantly higher in patients with IVRT/TE-e’ ratio < 5.6, which was shown to have good accuracy in identifying patients with significant MR who have elevated LV filling pressures.

Echocardiographic and CMR findings in a 66-year-old female with primary MR and normal diastolic function. The Echocardiogram shows early mitral velocity (E) of 100.0 cm/s, late mitral velocity (A) of 83.2 cm/s, and E/A ratio of 1.2. No time delay is present between onset of E velocity and onset of mitral annulus septal e’ velocity. Deceleration time is 176 ms (A). Mitral A-duration is 128 ms, while pulmonary vein atrial flow (Ar) duration is 140 ms and Ar-A = 12 ms (B). By CMR (1.5 T), the MR jet is visualized in the horizontal long axis view (C). Pre-contrast T1 map is shown (D), and ECV is 23.8%. The patient was followed up for 137 months with no events.

Echocardiographic and CMR findings in a 67-year-old female with primary MR primary MR and advanced diastolic dysfunction. The echocardiogram showed early mitral E velocity at 119.7 cm/s, mitral A velocity at 60.0 cm/s, E/A ratio of 2, The time delay between onset of E velocity and onset of mitral annulus septal e’ velocity is 28 ms, and deceleration time is 138 ms (A). Mitral A-duration is 85 ms, while pulmonary vein atrial flow (Ar) duration is 125 ms, and Ar-A = 40 ms (B). By CMR (1.5 T), the MR jet is visualized in the vertical long axis 2-chamber view (C). Pre-contrast T1 map is shown (D), and ECV is 31.9%. During follow-up, the patient had mitral valve repair and died 12 months later.

Box-and-whisker plots of ECV by diastolic function score (A), Ar-A duration (B), deceleration time (C), and time delay between onset of E velocity and onset of mitral annulus e’ velocity (D). *: P < 0.05 compared to DF score 0, ¶: P < 0.05 compared to DF score 1, + , P < 0.05 compared to DF score 2.

Association of LV diastolic function with outcome events

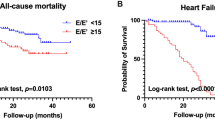

Figure 4 shows the events over time based on diastolic function score and its individual components. We next explored the incremental value of LV diastolic function score in multivariable modeling. The variables pursued included those that are clinically used for decisions to intervene in patients with primary MR. Variables previously shown to be associated with outcomes in MR patients (age, sex, comorbidities and risk factors, indexed LV EDV and ECV) were evaluated alongside the diastolic function score. Five comorbidities were recorded for the purpose of this study, and they were used to create a comorbidity score from 0 to 5 in the multivariable analysis. These comorbidities were congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension and atrial fibrillation. The variables selected in the comorbidity score are based on their association with outcomes in patients with primary MR. Of note, neither annular e’ velocities nor E/e’ ratio (septal, lateral, and average) was associated with outcome events.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing events-over-time in primary MR patients based on diastolic function score (A), and its components, Ar-A duration (B), deceleration time of mitral E velocity (C), and time delay between onset of E velocity and onset of mitral annulus e’ velocity (D). For panel (A), DF diastolic function score of 0 is shown in blue, score of 1 in purple, score of 2 in green, and score of 3 in yellow. For panel (B), Ar-A duration < 30 ms is shown in blue, and Ar-A duration ≥ 30 ms is shown in purple. For panel (C), DT > 150 ms is shown in blue, and DT ≤ 150 ms is shown in purple. For panel (D), TE-e’ ≤ 11 ms is shown in blue, and TE-e’ > 11 ms is shown in purple.

Table 4 shows the multivariable cox proportional hazard models for the aforementioned variables and the composite outcome of cardiac death, heart failure hospitalization and mitral valve surgery. Age, sex and comorbidity score (M1) were not significantly associated with the outcome.

The addition of indexed LV EDV and MR RF (M2) increased the AUC from 0.60 to 0.83 and both were independently related to the outcome (HR = 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.02, P = 0.044 and HR = 1.06, 95% CI 1.04–1.08, P < 0.001, respectively). Further addition of either diastolic function score (M3) or ECV (M4), etc increased the AUC to 0.86 and 0.87, respectively, and each was independently associated with the outcome events when included in separate models. Of note, the model (M2) with LV EDV index, MR RF and clinical variables had a BIC of 1032, while the model (M3) including LV diastolic function score in addition had a BIC of 1026 indicating a better fit.

The net reclassification improvement (NRI) for Model 3, compared to Model 2 as the baseline, was 0.5934 (p < 0.001), indicating a 59% improvement in reclassification accuracy with the inclusion of the diastolic function score alongside age, sex, comorbidity score, LVEDV index, and MR RF. Furthermore, the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) for Model 3 over Model 2 was 0.047 (p = 0.0248), reflecting a 4.7% enhancement in overall model discrimination.

Discussion

LV diastolic dysfunction as defined by specific indices of LV diastolic properties and pressure has a high prevalence in patients with primary MR that it is at least of moderate severity as defined by CMR measurements. One particular strength of this investigation is the fact that diastolic dysfunction was related to MR as patients with other etiologies for diastolic dysfunction, as cardiomyopathies, were excluded. In our study, diastolic dysfunction was associated with LV ECV, MR severity, and clinical outcome events. A diastolic dysfunction score that captures LV relaxation (TE-e’), LV operating chamber stiffness (DT), and LV EDP (Ar-A duration) provides incremental value to the prediction of adverse outcomes in primary MR patients when added to clinical characteristics, MR RF, and LV end diastolic volume index.

MR and changes in LV diastolic function

Primary MR of at least moderate severity results in increased LV volumes as a compensatory mechanism to allow for preserved stroke volume despite the regurgitant volume leaking into the LA during systole20. With progressive increase in MR severity, LV EDV increases further. The change in LV volume is not only due to increased myocyte volume but is also due to expansion of the ECV as documented by CMR studies6. Further, the expanded ECV is associated with worse clinical outcomes. LV diastolic dysfunction sheds light on the mechanism of this association between ECV and outcome events. There are clinical studies showing a significant direct correlation between ECV measurement by CMR and LV chamber stiffness in heart transplant recipients21. In our study in patients with chronic MR, the increased ECV was associated with short DT and increased LV EDP indicating the presence of increased LV stiffness and LV diastolic pressures. Interestingly, there are data showing abnormally increased chamber stiffness constant by cardiac catheterization in patients with primary MR and LV EF < 57%22. Likewise, there are similar findings in patients with primary MR undergoing mitral-transcatheter edge to edge repair using conductance catheters and preload changes to study LV EDP and EDV relationship23.

Animal studies in canines after three months of chronic severe MR showed depression of all indices of LV contractility24. More recently, prolonged LV time constant of LV relaxation (tau) was shown in patients with primary MR (versus controls) undergoing mitral-transcatheter edge to edge repair using conductance catheters to obtain tau measurements23. Thus, the presence of abnormal LV relaxation is an important finding that can be taken into account when studying the effects of MR on LV function. Despite the importance of this finding, it is challenging to rely on e’ velocity for this objective10,25. In that regard, TE-e’ is a specific measurement that was validated in this patient population10, and in this study, we show its association with outcome events. The primary component of the composite outcome was mitral valve surgery. Importantly, the diastolic function score components are not included in the clinical reports and thus not considered in MR surgery decisions. Given the demonstrated incremental value for the diastolic function score in predicting outcomes in this study, prospective studies are needed where diastolic function assessment is examined for determining timing of intervention for patients with primary MR. Interestingly, a recent study26, showed that patients with mitral valve prolapse and concave-shaped chest wall conformation (MHI or modified Haller index which is the chest transverse diameter divided by the distance between the sternum and the spine > 2.5) have a low prevalence of diastolic dysfunction, non hemodynamically significant MR and good outcome over mid-to-long-term follow-up period.

Limitations

This is a single center study and examination of the score in an independent sample from other centers would provide additional validation. The inclusion of patients with both echocardiographic and CMR imaging raises concerns for selection bias. However, this was unavoidable as we wanted to rely on CMR measurements for MR severity and also study the relation between myocardial fibrosis and LV diastolic function. The early onset of events, mostly mitral valve repair, indicates that the study sample had significant disease burden and needed timely treatment. Additional studies can shed light on the prognostic role of LV diastolic function in patients with a lower disease burden. The feasibility of Ar-A duration may be lower in labs that do not routinely acquire pulmonary vein signals. However, the feasibility of pulmonary vein flow recording is > 90% in the outpatient setting18. Further, pulmonary vein flow recordings should be pursued in this patient population given the importance of recognizing changes in pulmonary vein systolic flow and the recommendation for the consideration of this finding for the evaluation of MR severity20. While TE-e’ can take a longer time to measure, it has a high feasibility of acquisition by virtue of the high feasibility of acquiring mitral inflow and mitral annulus velocities. To increase the feasibility of making accurate measurement of the time delay, attention is needed during scanning to gain and filter settings, acquisition of 5–10 cardiac cycles for each of mitral inflow and septal and lateral annular velocity signals, velocity and time scale settings, and sweep speed. In our experience in this and other studies, it takes on average 1–2 min to complete the measurement. It is also possible to acquire E and e’ velocity simultaneously from the same cardiac cycle using dual Doppler probes which are now available in some ultrasound platforms27. While some of the measurements are not analyzed routinely in echocardiographic studies, the current data showing their strong association with outcome events provides solid justification for their application in day-to-day assessment in patients with significant primary MR. Of note, despite the availability of only 2 measurements in patients with atrial fibrillation (TE-e’ and DT), the diastolic function score was still associated with outcome events in this subgroup of patients.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Avierinos, J.-F. et al. Natural history of asymptomatic mitral valve prolapse in the community. Circulation 106, 1355–1361 (2002).

Enriquez-Sarano, M., Akins, C. W. & Vahanian, A. Mitral regurgitation. Lancet 373, 1382–1394 (2009).

Bakkestrøm, R. et al. Hemodynamic characteristics in significant symptomatic and asymptomatic primary mitral valve regurgitation at rest and during exercise. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 11, e007171 (2018).

Liu, B. et al. Myocardial fibrosis in asymptomatic and symptomatic chronic severe primary mitral regurgitation and relationship to tissue characterisation and left ventricular function on cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 22, 86 (2020).

Edwards, N. C. et al. Quantification of left ventricular interstitial fibrosis in asymptomatic chronic primary degenerative mitral regurgitation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 7, 946–953 (2014).

Kitkungvan, D. et al. Prognostic implications of diffuse interstitial fibrosis in asymptomatic primary mitral regurgitation. Circulation 140, 2122–2124 (2019).

AlJaroudi, W. et al. Impact of progression of diastolic dysfunction on mortality in patients with normal ejection fraction. Circulation 125, 782–788 (2012).

Liu, D. et al. Impact of diastolic dysfunction on outcome in heart failure patients with mid-range or reduced ejection fraction. ESC Heart Failure 8, 2802–2815 (2021).

Choi, Y.-J. et al. Network analysis of cardiac remodeling by primary mitral regurgitation emphasizes the role of diastolic function. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 15, 974–986 (2022).

Diwan, A., McCulloch, M., Lawrie, G. M., Reardon, M. J. & Nagueh, S. F. Doppler estimation of left ventricular filling pressures in patients with mitral valve disease. Circulation 111, 3281–3289 (2005).

Hasegawa, H. et al. Diastolic mitral annular velocity during the development of heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41, 1590–1597 (2003).

Rivas-Gotz, C. et al. Time interval between onset of mitral inflow and onset of early diastolic velocity by tissue Doppler: a novel index of left ventricular relaxation: experimental studies and clinical application. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 42, 1463–1470 (2003).

Little, W. C., Ohno, M., Kitzman, D. W., Thomas, J. D. & Cheng, C. P. Determination of left ventricular chamber stiffness from the time for deceleration of early left ventricular filling. Circulation 92, 1933–1939 (1995).

Garcia, M. J. et al. Estimation of left ventricular operating stiffness from Doppler early filling deceleration time in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circul. Physiol. 280, 554–561 (2001).

Rossi, A., Cicoira, M., Golia, G., Anselmi, M. & Zardini, P. Mitral regurgitation and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction similarly affect mitral and pulmonary vein flow Doppler parameters: the advantage of end-diastolic markers. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 14, 562–568 (2001).

Kitkungvan, D. et al. Extracellular volume in primary mitral regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 14, 1146–1160 (2021).

Lang, R. M. et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the american society of echocardiography and the european association of cardiovascular imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 28, 1-39.e14 (2015).

Nagueh, S. F. et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the american society of echocardiography and the european association of cardiovascular imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 29, 277–314 (2016).

Raftery, A. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociol. Methodol. 25, 111–163 (1995).

Zoghbi, W. et al. Recommendations for noninvasive evaluation of native valvular regurgitation: a report from the american society of echocardiography developed in collaboration with the society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 30, 303–371 (2017).

Ellims, A. H. et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis evaluated by post-contrast T1 mapping correlates with left ventricular stiffness. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 1112–1118 (2014).

Corin, W. J., Murakami, T., Monrad, E. S., Hess, O. M. & Krayenbuehl, H. P. Left ventricular passive diastolic properties in chronic mitral regurgitation. Circulation 83, 797–807 (1991).

Nagueh, S. F. et al. Understanding the effects of mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair on left ventricular function using pressure-volume loops. JACC Adv. 4, 101627 (2025).

Ishihara, K. et al. Left ventricular mechanics and myocyte function after correction of experimental chronic mitral regurgitation by combined mitral valve replacement and preservation of the native mitral valve apparatus. Circulation 86(5), 16–25 (1992).

Olson, J. J., Costa, C., Young, C. E. & Palac, R. T. Early mitral filling/diastolic mitral annular velocity ratio is not a reliable predictor of left ventricular filling pressure in the setting of severe mitral regurgitation. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 19, 83–87 (2006).

Sonaglioni, A., Nicolosi, G. L., Rigamonti, E. & Lombardo, M. Impact of chest wall conformation on the outcome of primary mitral regurgitation due to mitral valve prolapse. J. Cardiovasc. Echogr. 32, 29–37 (2022).

Kusunose, K. et al. Clinical utility of single-beat E/e′ obtained by simultaneous recording of flow and tissue Doppler velocities in atrial fibrillation with preserved systolic function. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2, 1147–1156 (2009).

Funding

Dr Nagueh is the Levant Foundation Chair for Cardiovascular Diseases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hossam Lababidi, Kinan Carlos El-Tallawi, Clara L Angulo, Danai Kitkungvan, Dipan J Shah, and Sherif F Nagueh. reviewed records and analyzed echocardiographic images and CMR studies, Hossam Lababidi performed statistical analysis, Hossam Lababidi prepared figures, Dipan J Shah, William A. Zoghbi. reviewed the manuscript and provided critical comments. Hossam Lababidi and Sherif F Nagueh wrote the main manuscript text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lababidi, H., El-Tallawi, K.C., Kitkungvan, D. et al. The prognostic importance of left ventricular diastolic function in primary mitral regurgitation and its relation to structural changes by CMR. Sci Rep 15, 35079 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18965-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18965-0