Abstract

Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) is recognized as an effective pain relief for treating chronic pain, though the mechanism of the analgesic effect remains unclear. Recent studies have focused on the potential anti-inflammatory effect in analgesia through PRF. Therefore, we investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of PRF using the knee pain mouse models induced by monoiodoacetic acid. Our findings demonstrated that PRF on the sciatic nerve significantly reduces knee pain, synovitis, and inflammatory cytokines, thereby supporting the hypothesis that PRF exerts an anti-inflammatory effect. Moreover, a tracer study and western blotting analysis revealed that PRF inhibited axonal transport in small dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons in the spinal cord and suppressed the secretion of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (SP), both of which are associated with persistent inflammation, into the knee joint. Finally, the administration of both CGRP and SP agonists to the knee joint nullified the analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of PRF. In conclusion, our studies revealed that PRF exerted analgesic effects based on anti-inflammatory effects through inhibition of CGRP and SP secretion caused by impaired axonal transport in small DRG neurons. We hope that these findings will lead to further dissemination of PRF treatment in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pulsed Radiofrequency (PRF) treatment has emerged as a significant advancement in the management of chronic pain, providing a minimally invasive alternative to traditional pain management techniques. PRF involves positioning a special needle probe close to the targeted nerve and connecting it to a machine that generates radio waves. These radio waves are generated from the tip of the needle probe, affecting the nerve. Unlike continuous radiofrequency (CRF), which generates heat to disrupt nerve function, PRF delivers electrical energy in short, controlled bursts, allowing for the modulation of pain signals without significant thermal damage to surrounding tissues1. This characteristic feature is crucial for its application in sensitive or densely innervated areas where traditional methods might pose a higher risk of complications.

PRF shows versatility in managing chronic pain, with evidence supporting its application in conditions such as cervical radicular pain2lumbar radicular pain3postherpetic neuralgia4and shoulder joint pain5. For trigeminal neuralgia and facet joint pain6,7the superiority of CRF over PRF is well-established, underscoring thermocoagulation’s advantage in these specific cases. However, PRF has shown utility in other painful conditions such as knee pain, occipital neuralgia, perineal pain, and carpal tunnel syndrome, and the potential for broad applicability in pain management8.

While PRF is a promising therapeutic approach, the exact mechanism in pain alleviation remains poorly understood. It is suggested that PRF exerts its pain-relieving effects through a complex interaction with biological processes. Reportedly, PRF may lead to an increase in cytosolic calcium concentration, which plays a crucial role in various cellular functions including neurotransmitter release and gene expression9. Another report suggested that PRF might modulate pain perception through the activation of noradrenergic and serotonergic descending pain inhibitory pathways via the enhancement of endogenous opioid signaling10. Moreover, PRF may contribute to a reduction in the formation of free radical molecules, which are known to cause tissue damage and pain through oxidative stress mechanisms11,12. Among some explored hypotheses, the suppression of microglial proliferation within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord emerged as a key mechanism, potentially addressing the inflammatory basis of chronic pain13. Additionally, it is thought that PRF may modulate immune responses that contribute to the pain pathway14,15. In fact, PRF reduced the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are key mediators of inflammation and pain16. Taken together, it is hypothesized that PRF can effectively disrupt pain signal transmission and reduce pain, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic tool in the management of chronic pain conditions.

In our study, we selected the monoiodoacetic acid (MIA) induced knee pain model in mice to investigate the anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of PRF. The MIA model effectively mimics key aspects of knee pain, including joint inflammation, resultant pain and cartilage loss17making it an apt choice for assessing the potential anti-inflammatory benefits of PRF. We focused on the anti-inflammatory effect and tried to elucidate the complex mechanism of PRF using the mouse model of chronic pain.

Results

PRF alleviated pain associated with knee pain mouse model

To investigate the analgesic effect of PRF in a mouse knee pain model, we performed weight-bearing and foot stamp tests using an MIA-induced knee pain mouse model. The baseline measurement in the weight-bearing test in the sham and PRF groups before MIA treatment was approximately 0.5, and the mice were homogeneously loaded between the right and left hind limbs. After an injection of MIA into the right knee joint, reduction of the load on the right hind paw in both groups was observed at 1 day that persisted until 7 days after injection. Whereas load imbalance was detected until day 14 in the sham group, it improved on day 10 in the PRF group (p = 0.019), and this improvement persisted until 14 days after injection (p = 0.0032) (Fig. 1e). Subsequently, a foot stamp test was performed for the sham and PRF groups. Before the administration of MIA, the stride lengths of both groups were almost 1 and were equal on both the left and right sides. After MIA injection to the right knee joint, the mice’s gait seemed as if they were protecting their right hind paw and the stride length between the left and right sides differed; the right stride length of both groups showed a significant decrease (Fig. 1f). Repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to evaluate time-dependent changes in behavioral tests within each group. In the weight-bearing test, a significant main effect of time was observed in both the Sham group [F (5, 45) = 27.75, p < 0.0001] and the PRF group [F (5, 45) = 15.65, p < 0.0001]. Similarly, in the foot stamp test, a significant main effect of time was found in the Sham group (F(5, 45) = 11.89, p < 0.0001) and the PRF group [F (5, 45) = 8.53, p < 0.0001]. These results indicate that both groups exhibited significant time-dependent changes. Notably, the F-values were higher in the Sham group, suggesting that the magnitude of behavioral changes was more pronounced in untreated animals, and that PRF may have attenuated the progression of pain-related behaviors. Whereas the ratio of the stride length of the sham group remained the same until day 14, the stride imbalance of the PRF group significantly improved from day 10 onward (days 10: p = 0.038, days 14: p = 0.0014).

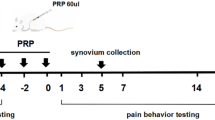

Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) alleviated symptoms of knee pain in mouse models. (a) Animal experimental schedule. The knee pain mouse models were established by a joint injection of MIA in saline (red arrow). The behavioral tests were performed on days 0, 1, 3, 7, 10, and 14 (yellow arrows). PRF or sham operation was performed on day 7 (left arrow). Tissue collection was done on day 14 (right arrow). (b) Representative photos during PRF (left: catheterized procedures for PRF or sham operation, right: grounding of the catheter tip and sciatic nerve). Red line: catheter needle; Yellow arrow: sciatic nerve. (c) Representative photos during the weight-bearing test. (d) Representative photograph during the foot stamp test. (e) The bar graphs of the average value of the weight-bearing test at 0, 1, 3, 7, 10, and 14 days. White: Sham and Grey: PRF group. Normal: 0 day, knee pain (pre-PRF): 1, 3, 7 days, and knee pain (post PRF): 10, 14 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way repeated-measures ANOVA within each group to evaluate time-dependent changes, and unpaired t-tests were used to compare PRF and Sham groups at each time point. †p < 0.05 vs. 0 day in the sham group, ♭p < 0.05 vs. 0 day in the PRF group normal, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the sham group on the same day. (f) The bar graphs of the average value of the foot stamp test at 0, 1, 3, 7, 10, and 14 days. White: Sham and Grey: PRF group. Normal: 0 day, knee pain (pre-PRF): 1, 3, 7 days, and knee pain (post-PRF): 10, 14 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way repeated-measures ANOVA within each group to evaluate time-dependent changes, and unpaired t-tests were used to compare PRF and Sham groups at each time point. †p < 0.05 vs. 0 day in sham group, ♭p < 0.05 vs. 0 day in the PRF group normal, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the sham group on the same day. (g) Representative photomicrograph of safranin O staining in the knee joint (top left: sham; top right: PRF; bottom: contralateral). Black arrows: knee cartilage. Scale bar: 50 μm. (h) The bar graphs of the average value of the Mankin score. White: Sham and Grey: PRF group.

To investigate whether the results of the behavioral test were caused by differences in the degree of knee articular cartilage loss between the sham and PRF groups, a pathological analysis with safranin staining was performed, in which the cartilage was detected using mouse knee joint tissue 14 days after injection. The results showed that the left knees in both groups exhibited normal knee joints with the Mankin score (Table 1) of 0, whereas the right knees treated with MIA showed a significant decrease in knee cartilage regardless of PRF treatment (Fig. 1g). The Mankin score of the right knee was 7.25 ± 0.089 in the sham group and 7.0 ± 0.93 in the PRF group (Fig. 1h). There was no significant difference in the joint deformity between the sham and PRF groups.

Next, to determine whether PRF treatment affects normal nerves, we performed comparative analyses using PRF-treated and sham-treated normal mice, using various behavioral tests to evaluate motor function, etc. Spontaneous activity measurement tests (Fig. 2a) and rotarod tests (Fig. 2b) showed no significant differences in spontaneous activity, motor coordination, or sense of balance between the two groups. In addition, an open-field test revealed that PRF treatment did not affect motor function (Fig. 2c–f). Furthermore, the neuromuscular reflexes of mice were examined using the tail suspension test. Regardless of whether they were treated with PRF or not, all mice analyzed showed normal leg posture, which is a neuromuscular reflex (Fig. 2g). In addition, we performed the weight-bearing and foot stamp tests in normal mice to examine whether PRF affects gait or limb loading in the absence of inflammation. Consistent with other motor function tests, no significant differences were observed between the PRF and sham groups (Fig. 2h, i). These behavioral test results demonstrated that PRF treatment did not affect normal neurons.

Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) had no effect on normal nerves. (a) Bar graph indicating the average measured value of spontaneous activity. White: Sham group and grey: PRF group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of twelve sham-ope-treated and thirteen PRF-treated normal mice per group, determined by Student’s paired t-test. (b) Bar graph indicating the average retention time in the Rotarod test. White: Sham group and grey: PRF group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of twelve sham-ope-treated and thirteen PRF-treated normal mice per group, determined by Student’s paired t-test. (c–f) Representative tracking image of Sham (left) and PRF group (right). Bar graphs showing (d) average travel distance, (e) average travel speed, and (f) activity time. White: Sham group and grey: PRF group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of twelve sham-ope-treated and thirteen PRF-treated normal mice per group, determined by Student’s paired t-test. (g) Representative images of the tail suspension test in the sham (left) and PRF groups (right). (h) The bar graph of the average value of Weight-bearing test. White: sham and Grey: PRF group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of twelve sham-ope-treated and thirteen PRF-treated normal mice, determined by Student’s paired t-test. (i) The bar graph of the average value of Foot stamp test. White: sham and Grey: PRF group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of twelve sham-ope-treated and thirteen PRF-treated normal mice, determined by Student’s paired t-test.

Taken together, these findings demonstrated that PRF alleviated knee pain without altering knee cartilage.

PRF alleviated knee inflammation associated with knee pain mouse model

Next, we investigated the effect of PRF on knee inflammation through pathological analysis using HE-stained specimen of the mouse knee 14 days after MIA injection. No cell infiltration was observed in the left hind paw of either group or the infrapatellar fat pad showed a network structure. In contrast, many cells had infiltrated the synovial membrane and fat pad in the right limb of the sham group. However, the right limb in the PRF group showed less cell invasion into synovial membrane and fat pad. The sham and PRF groups were quantitatively compared by calculating the ratio of the area other than fat pad in the synovium (Inflammatory damage area) to total synovial and fat pad area. There was no significant difference in the left knee in either group (p = 0.98); however, the eosin-stained area in the right knee was significantly larger than that in the left knee (p = 0.0023) (Fig. 3a, b). The infiltration of immune cells, particularly macrophages, into the synovium, is a representative histological change representing knee inflammation in knee arthritis18,19. Since macrophages play a major role in synovitis, immunofluorescence staining with a macrophage-specific F4/80 antibody in the damaged area identified by HE staining was performed. Although in both groups, macrophage infiltration was observed in the synovium and infrapatellar fat pad of the right hind paw (Fig. 3c), there was significantly less macrophage infiltration in the PRF group than in the sham group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3d). No macrophage infiltration was observed in the left knee of either group. Because knee pain is correlated with synovitis in knee pain20we also analyzed the correlation between the two behavioral tests and synovitis. When correlation analysis was performed separately for each group, PRF-treated mice showed a stronger correlation between synovitis markers (H&E staining, F4/80 staining) and weight-bearing test results (H&E: R2 = 0.41, F4/80: R2 = 0.63), suggesting a potential association between PRF-mediated anti-inflammatory effects and pain improvement (Fig. 3e). In addition to groupwise analysis, we also calculated the correlation using all samples regardless of group. The coefficient of determination (R2) between weight-bearing test results and HE-stained inflammatory area was 0.570, and that between weight-bearing test results and F4/80-positive area was 0.607. Considering these results, these findings suggest an association between knee pain and synovitis.

Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) alleviated knee joint inflammation associated with knee pain. (a) Representative HE images of the knee joints. Left: Sham group; right: PRF group. Upper, right knee; lower, left knee. Black arrow: synovial membrane. The black dotted line indicates the inflammatory area used for quantification in the HE-stained section. Scale bar: 100 μm. (b) Bar graph of the mean percentage of the inflammatory area. The area of inflammation in the infrapatellar fat pad was compared as a percentage. Both left (L) and right (R) knees are shown for each group. Statistical analysis was performed between the right knees of the PRF and Sham groups using unpaired t-test. **p < 0.01 vs. the sham group on the same day. (c) Representative micrographs of immunostaining with the F4/80 antibody. Yellow arrows indicate the synovial membrane. The white dotted line indicates the F4/80-positively stained area used for quantification. Scale bar: 100 μm. (d) Bar graph of the mean percentage of the cellular infiltration area. Both left (L) and right (R) knees are shown for each group. Statistical analysis was performed between the right knees of the PRF and Sham groups using unpaired t-test. ***p < 0.001 vs. the sham group on the same day. (e) Graphs of the correlation analysis between weight bearing test and HE staining (left) or immunostaining for F4/80 (right). Red dots indicate the sham group, and black dots indicate the PRF group. The correlation was analyzed separately for each group. The horizontal axis shows the values of the two behavioral tests, and the longitudinal axis shows the values of the HE staining of the knee joint (left) and the immunostaining with F4/80 (right). (f) Bar graph of the average values of mRNA expression of interleukin (IL)-1β (left), IL-6 (middle), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (right) in the left (L) and right (R) knee joints in the sham (white) and PRF groups (gray). Statistical analysis was performed between the right knees of the PRF and Sham groups using unpaired t-test. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. the right knee joint of the sham group on the same day.

Subsequently, to confirm the anti-inflammatory effect of PRF, we analyzed the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) using qPCR. The qPCR data demonstrated that the expression of all inflammatory cytokines in the right knee was significantly higher than that in the left knee in both groups, and the PRF group showed a significant decrease in the levels of all inflammatory markers compared with the sham group (IL-1β: p = 0.0093, IL-6: p = 0.0038, TNF-α: p < 0.001) (Fig. 3f). In contrast, in normal mice, no mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines was detected, regardless of whether or not they were treated with PRF (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

Taken together, these findings demonstrated that PRF alleviated knee pain by suppressing arthritis.

PRF impaired axonal transport in only small neurons of the 4th lumbar spinal DRG

According to a report on electron microscopy, the electromagnetic field generated by PRF has a greater effect on nerve fibers with smaller diameters21. The analgesic effect of PRF might stem from a process akin to neuromodulation, affecting either the synaptic transmission or the excitability of C-fibers22. Therefore, we focused on the C-fibers, which extend from the small neurons of the DRG, as the key to elucidating the mechanism of action of PRF. To investigate whether PRF impaired axonal transport in small neurons of the 4th lumbar spinal DRG (L4-DRG) that composes the sciatic nerve, we performed a retrograde nerve tracer study using Fast Blue 24 h before tissue removal and a comparative analysis by counterstaining with Nissl stain (Fig. 4a, b). The L4-DRG neurons were divided into two types: small neurons (cells with nuclei < 30 μm in diameter) and other large neurons, and the number of each cell was counted. There was no significant difference in the percentage of Fast Blue-positive neurons among all L4-DRG neurons between the two groups (p = 0.29), but the percentage of Fast Blue-positive small neurons in the PRF group was significantly lower than that in the sham group (p = 0.038) (Fig. 4c, d). To confirm that PRF affected the axonal transport of L4-DRG small neurons, we performed double staining with Fast Blue and peripherin, a small DRG neuronal marker23. The results revealed that the percentage of double-positive cells was significantly lower in the PRF group than in the sham group (p = 0.0034) (Fig. 4e, f). In contrast, the tracer analysis of the normal side showed no significant difference between the sham and the PRF group, and the positive cell rate showed a similar tendency to that of the affected side in the sham group (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, tracer analysis of PRF-treated healthy mice revealed that PRF had a small but not significant effect on DRG axons (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) impaired axonal transport in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) small neurons. (a) Experimental schedule. Fast Blue was injected on day 13 after MIA administration, and the tissue was collected on day 14. (b) Illustration of Neurotracer injection into the mouse knee joint using a Hamilton syringe. The next day, the L4 DRGs were collected. (c) Representative micrographs of Nissl staining (upper) and Fast Blue retrograde tracer (FB: bottom) in the L4 DRG of the sham (left) and PRF (right) groups. The yellow arrow indicates FB-positive neurons. Scale bar: 100 μm. (d) Bar graph of the mean percentage of FB-positive cells among total cells (top), FB-positive large cells among total large cell counts (bottom left), and FB-positive small cells among total small cell counts (bottom right) in the sham (white) and PRF groups (gray). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t-test. *p < 0.05, vs. the sham group on the same day, n.s.: no significant. (e) Representative images of FB staining (upper panel) and immunostaining with anti-peripherin antibody (bottom) in the L4 DRG of the sham (left) and PRF (right) groups. Yellow arrowheads indicate FB- and peripherin-positive cells; red arrowheads indicate FB-positive and peripherin-negative cells. Scale bar: 100 μm. (f) The bar graph shows the average percentage of both FB- and peripherin-positive cells among peripherin-positive cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t-test. **p < 0.01 vs. the sham group on the same day.

Taken together, these findings demonstrated that PRF inhibited axonal transport especially in small neurons of the L4-DRGs projecting to the knee joint.

PRF inhibited the secretion of CGRP and SP, which May have a persistent inflammatory effect on the knee joint

Small DRG neurons are reported to release CGRP and SP both anterogradely and retrogradely, potentially playing a role in chronic inflammation24,25,26,27. Moreover, Aso et al. reported that CGRP-positive lumbar spinal DRG neurons were increased in knee pain rat models compared with normal rats28. Furthermore, inflammatory mediators such as inflammatory cytokines released by MIA-induced chondrocyte destruction and synovitis promote the release of CGRP and SP from DRG neurons projecting to the joint via activation of pain receptors29,30. Therefore, we hypothesized that CGRP and SP may be involved in the persistence of inflammation in knee pain mouse models and investigated whether arthritis and PRF affected the expression of CGRP and SP in the knee. Western blot analysis revealed that the expression of both CGRP and TAC1, which is the precursor to SP, increased in the right knee than in the left knee in both groups, but the expression in the PRF group was significantly decreased compared to that in the sham group (CGRP: p = 0.047, TAC1: p = 0.013) (Fig. 5a-c, Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, in normal mice, no expression of CGRP or SP was detected, regardless of whether or not they were treated with PRF (Supplementary Fig. 1d-f). Furthermore, tracer analysis using fluorescent dextran as an anterograde tracer was performed to determine whether the PRF affected the projection of the L4-DRG to the joint. As a result, it was revealed that the positive signals of the DRG nerve terminals projecting to the knee joint were reduced compared to the sham group (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) treatment of the knee pain alleviated the increase in calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and tachykinin precursor 1 (TAC1). (a) Western blotting analysis of GAPDH (upper), CGRP (middle), and TAC1 (bottom) in the right (R) and left (L) joints. PRF inhibited the upregulation of CGRP and TAC1 accompanying knee pain. (b,c) Bar graph of the mean values in Western blotting band quantification of CGRP(B) and TAC1(C) in the left (L) and right (R) knee joints in the sham (white) and PRF (right) groups. Both groups showed an increased CGRP and TAC1 expression in the right knee than in the left knee, but the PRF group showed a significant decrease in CGRP and TAC1 expression compared to the sham group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6 per group). Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t-test between the right knees of the Sham and PRF groups. *p < 0.05, vs. sham group on the same day. No statistical analysis was performed for left knees; values are shown for reference only.

Taken together, these data revealed that PRF inhibited the secretion of CGRP and SP associated with arthritis into the knee joint via axonal damage to L4-DRG small neurons.

Administration of CGRP and SP agonists to the knee joint nullified the effects of PRF

To investigate whether the effect of PRF was due to the inhibition of CGRP and SP secretion, we conducted experiments using agonists. Each agonist was administered 6 days after PRF treatment (13 days after the injection of MIA). Symptoms associated with knee pain were assessed at 0–7 days after PRF treatment (7–14 days after the injection of MIA) using two behavioral tests (Fig. 6a). Consistent with previous results, PRF ameliorated hind limb load imbalance and gait deterioration associated with knee pain (Fig. 6b and c). However, statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc multiple comparison tests revealed that these effects of PRF were negated by the administration of both CGRP and SP agonists to the knee joint (weight-bearing test: p < 0.001, foot stamp test: p = 0.007). CGRP or SP agonist alone did not significantly alter the effect of PRF. Finally, proinflammatory cytokine expression was analyzed using qPCR to determine whether agonist administration nullified the anti-inflammatory effects of PRF. Administration of both agonists also nullified the anti-inflammatory effects of PRF (IL-1β: p = 0.0024, IL-6: p = 0.0084, TNF-α: p = 0.0025) (Fig. 6d). CGRP or SP agonists alone could not cancel out the effects of PRF. Taken together, the analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of PRF were exerted by suppressing the secretion of both CGRP and SP.

Knee joint injections of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (SP) agonists eliminate the effects of pulsed radiofrequency (PRF). (a) Experimental schedule. Behavioral tests were performed on days 7, 10, 13 and 14 after MIA administration. PRF was performed on day 7. Injections of normal saline (NS), CGRP agonist (5 ng), SP agonist (100 ng), or CGRP + SP (C + S) agonists were administered on day 13. Tissues were collected on day 14. (b) The bar graph shows the average values of the weight-bearing test measurements of the right knee joints in the NS (white), CGRP (green), SP (blue), and C + S groups (red). Treatment with CGRP and SP on day 13 counteracted the analgesic effect of PRF on day 14. Treatment with CGRP or SP alone did not counteract the effects of PRF. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, followed by post-hoc multiple comparison tests. ***p < 0.001 vs. NS group on the same day. (c) The bar graph shows the average values of the foot stamp test measurements of the right knee joints in the NS (white), CGRP (green), SP (blue), and C + S groups (red). Treatment with both CGRP and SP on day 13 counteracted the gait improvement effects of PRF on day 14. Treatment with CGRP or SP alone did not counteract the gait-improvement effects of PRF. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, followed by post-hoc multiple comparison tests. **p < 0.01, vs. NS group on the same day. (d) Bar graph of the average values of mRNA expression of interleukin (IL)-1β (left) and IL-6 (right) of the right knee joints in the NS (white), CGRP (green), SP (blue), and C + S groups (red). The C + S group showed increased proinflammatory cytokine levels. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, followed by post-hoc multiple comparison tests. **p < 0.01, vs. NS group on the same day.

Discussion

Recent evidence underscores PRF as a promising intervention for chronic pain management, characterized by minimal adverse effects. However, the precise mechanisms underlying its analgesic and anti-inflammatory actions remain unclear. This study was conducted on the hypothesis that PRF’s analgesic effects are intricately linked to its ability to mitigate inflammation. Using an MIA-induced knee pain mouse model, we investigated in detail the effect of PRF on anti-inflammatory effect and analgesia. Our findings revealed that PRF not only ameliorated mechanical stress-related symptoms, such as hind limb weight imbalance and gait deterioration, but also significantly reduces immune cell infiltration and proinflammatory cytokine expression within the knee joint. Moreover, the tracer study and Western blotting analysis demonstrated that PRF selectively inhibited axonal transport in small DRG neurons, which may lead to a diminished peripheral release of CGRP and SP. This reduction was particularly significant as it suggested a potential anti-inflammatory role for PRF, given that CGRP and SP were increasingly recognized for their contributions to modulating inflammatory responses.

Recent papers indicate a growing interest in the anti-inflammatory capabilities of PRF. In the animal experiments using pain mouse and rat models, it has been revealed that PRF reduces inflammatory cytokines in the affected area31,32reduces oxidative stress related to the persistence of inflammation33and suppresses the activation of microglia in the spinal cord related to central sensitization34,35,36,37,38. In clinical studies, a reduction in inflammatory cytokines by PRF was observed in patients with pain39,40. To clarify the relationship between analgesia and anti-inflammation, the MIA-induced knee pain mouse model was chosen specifically for its relevance to inflammation’s critical role at pain sites. This mouse model demonstrated that MIA-induced chondrocyte damage leads to the loss of knee cartilage tissue, which is further exacerbated by mechanical stress placed on the knee joint over time. Interestingly, PRF’s application targeted the axons of the sciatic nerve in the mid-thigh, away from the knee joint and neuronal cell bodies. Nonetheless, the anti-inflammatory effects within the knee joint suggested PRF’s potential to diminish pro-inflammatory mediators through its neural actions, leading us to further assess axonal transport and neurotransmitter expression changes. Reportedly, electron microscopy revealed that PRF treatment resulted in damage to C-fiber and mitochondria in the axons21. Axonal mitochondria and C-fibers are closely related to axonal transport functions. Mitochondrial damage leads to a decrease in ATP production, causing a reduction in the function of motor proteins such as kinesin and dynein, which facilitate microtubule transport. This dysfunction results in the retention of organelles and proteins in the axon, which may lead to nerve dysfunction and degeneration41. Moreover, C-fiber damage significantly inhibits axonal transport, leading to changes in nerve function and potentially contributing to various nerve disorders42. However, there have been no reports of severe damage caused by PRF43,44,45. Moreover, Western blotting analysis showed that PRF attenuated the increased expression of CGRP and SP associated with MIA-induced arthritis, but did not reduce them to the same levels as in the normal side (Fig. 5b, c). Furthermore, there is another report that low-frequency electromagnetic fields do not affect axonal transport (neither does crushing the sciatic bone)46. Therefore, it is believed that the effects of PRF on axonal transport are minor and reversible. On the other hand, morphological studies pinpointed a specific impact of PRF on the axons of peripherin-positive small DRG neurons (Fig. 4). Given that small DRG neuron axons are primarily composed of C-fibers47our findings lend support to the hypothesis that PRF exerts a significant modulatory effect on C-fibers22.

The intricate roles of CGRP and SP in inflammation and pain encompass a broad spectrum of physiological and pathological processes. Small DRG neurons are notably characterized by secretion of these neuropeptides both anterogradely and retrogradely25,26,27. CGRP, a neuropeptide of 37 amino acids, acts as a potent vasodilator, playing a critical role in cardiovascular function and wound healing24. Moreover, nerve excitation at peripheral endings facilitates CGRP release48. Furthermore, the adipocyte protein 2 (AP2) complex, containing α AP2α2 and preferentially expressed in CGRP-positive neurons within the DRG, has been associated with the modulation of nociceptive pain upon AP2 inhibitor protein administration49suggesting a profound involvement of CGRP-positive neurons in pain mechanisms. On the other hand, the definitive role of CGRP as a pro- or anti-inflammatory agent remains controversial. CGRP’s action on surrounding Schwann cells via the calcitonin-like receptor/receptor activity modifying protein (CLR/RAMP1) contributes to neurogenic inflammation and periorbital allodynia50Interestingly, whereas CGRP has been observed to downregulate macrophage TNF-α production in models of oxygen-induced retinopathy51. Considering previous reports, CGRP may have both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects.

SP (Tachykinins), belonging to the neuropeptide family, is involved in vital physiological processes of nociception and inflammation within both the nervous and immune systems52. The regulation of leukocyte activity by SP highlights its crucial role in mediating both acute and chronic inflammatory responses53. Moreover, SP has been reported to be involved not only in inflammatory symptoms but also in psychiatric symptoms (depression and anxiety) in inflammatory diseases (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease and asthma)54. The release of SP following acute CNS injuries including head trauma or stroke, plays a role in neurogenic inflammation, with neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists showing efficacy in ameliorating such conditions55. Furthermore, SP, alongside hydrogen sulfide, has been linked to the exacerbation of inflammation in various acute conditions, including pancreatitis, sepsis, burns, and arthritis56further supporting the possibility of pro-inflammatory action of SP. Notably, in the MIA-induced arthritis rat models, both CGRP and SP levels were significantly elevated in both DRG57 and joint through inflammatory cytokines released by MIA-induced chondrocyte destruction and synovitis29,30supporting our findings of increased CGRP and SP levels in MIA-treated joints and their suppression following PRF treatment (Fig. 5). The co-expression of CGRP and SP in small DRG neurons58and CGRP’s enhancement of SP-induced pain behavior59 suggest a synergistic role in sustaining arthritis-related knee pain and synovitis. CGRP suppresses the endopeptidase that degrades SP60 and increases the Ca2 + concentration at the primary sensory terminal of the DRG, thereby promoting the release of SP and glutamate24,29,61. Moreover, SP-induced degranulation of mast cells leads to extravasation accompanied by the release of histamine and pain substances (bradykinin and serotonin), vasodilation, and activation of other inflammatory cells, such as macrophages29,62resulting in enhanced pain stimulated by CGRP. Therefore, the suppression of both neuropeptides’ secretion emerges as a strategic approach in arthritis-induced knee pain treatment. Our research demonstrated that the analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of PRF were reversed upon the simultaneous administration of CGRP and SP agonists (Fig. 6), emphasizing the pivotal roles of CGRP and SP in arthritis-related knee pain pathogenesis. In conclusion, PRF ameliorated arthritis-induced pain and inflammation by inhibiting the peripheral release of these neurotransmitters.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that PRF mitigated knee pain symptoms by exerting anti-inflammatory effects within the knee joint. These effects were based on the disruption of axonal transport in small DRG neurons and the subsequent reduction in peripheral secretion of CGRP and SP. The elucidation of PRF’s analgesic and anti-inflammatory actions represented a significant advancement in our understanding of its therapeutic mechanism, offering promising avenues for the treatment of chronic pain. These findings underscore the potential of PRF as a multifaceted chronic pain treatment strategy that also targets underlying inflammatory process. Furthermore, the findings that PRF does not affect normal nerve function not only proves the safety of PRF but also raises the possibility that it may become a treatment for various types of pain. Future research should focus on clarifying the molecular pathways involved in PRF’s effects and exploring its applicability to a broader range of chronic pain conditions. We believe that further studies, including our findings, will be crucial in optimizing PRF protocols for enhanced patient outcomes in chronic pain management.

Methods

Mouse model of knee pain

Eight-week-old ddY male mice were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). Mice were housed at a temperature of 23–25 °C and a 12-h day/night cycle with free access to food and water. A MIA (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemicals Corporation, Osaka, Japan) solution was prepared at a concentration of 0.75 mg in 10 µL of sterile saline and injected into the right knee of mice with a Hamilton syringe (GL Sciences inc., Tokyo, Japan). Under general anesthesia induced with sevoflurane, a 5-mm skin incision was made in the knee, and intra-articular injection was performed under direct visualization. After the injection, the skin was closed with a 5 − 0 silk thread (Alfresa, Tokyo, Japan). One week after treatment, PRF was performed. Another week later, behavioral tests and morphological and biochemical analyses were performed (Fig. 1a). We minimized the number of animals used and removed tissues after euthanizing the animals under deep anesthesia using a combination of medetomidine (0.3 mg/kg), midazolam (4.0 mg/kg), and butorphanol (5.0 mg/kg) to mitigate pain.

PRF treatment on mouse sciatic nerve

The electromagnetic field generated by PRF is very narrow63 and is effective only when the nerve is in contact with the needle tip. Therefore, we modified the method described by Erdine et al.21 to improve the reliability of PRF. PRF was performed using the JK3 Neuro Thermo® (Abbott medical Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The mouse thigh was incised under general anesthesia, and the sciatic nerve was exposed by dissecting the muscle layer. Unlike the saphenous nerve, muscle contraction could be easily identified in the sciatic nerve, improving the reliability of PRF (Fig. 1b). After confirming the generation of muscle contraction by electrical stimulation, the PRF group was subjected to PRF (intermittent current 2 Hz, cycle 20 ms, needle tip temperature below 42 °C) 4 times for 2 min each time (total 8 min). The sham group received only electrical stimulation for 8 min.

Behavioral tests

Assessment of motor function in MIA-induced arthritis mouse models

The analgesic effect of PRF on knee arthritis was examined using two types of behavioral tests (weight-bearing and foot stamp tests). In the weight-bearing test, mice are placed in a small cage and held stationary on their hind paws, and the weights of the left and right hind paws are measured simultaneously to evaluate the left-right balance of each hind paw. When measuring the weight, the tail was gently held in place and lifted off the scale by hand, and the mouse stood in the center of the two scales in a straight and still posture (Fig. 1c). The gait of the model mice was evaluated by examining the stride length in the left and right foot stamp tests. The foot stamp test is a method of measuring stride length and other parameters from footprints made by applying water-based paint to the forelimbs and hindlimbs of mice as they walk in a straight line through a tunnel made of a 2.5-inch wide, 3-inch high, and 13-inch-long acrylic plate (Fig. 1d). The experimental procedure was performed according to the protocol described by Virginia et al.64.

Analysis of the effects of PRF treatment on normal nerves

To investigate the effects of PRF treatment on normal neurons, the following behavioral tests were performed to evaluate various motor functions using PRF-treated mice. The experimental preparation was performed as previously described65. Moreover, to assess joint pain and degeneration linked to inflammation, the muscle-nerve reflex was measured in the open-leg position using the tail suspension test.

Measurement of spontaneous activity using supermax system

Spontaneous activity was measured for 10 min in home cages using an infrared sensor system that detected mice’s body heat (Muromachi Kikai Co., Tokyo, Japan), with data digitally recorded and analyzed using dedicated software (CompACT AMS Ver.3; Muromachi Kikai Co.).

Open field test

Spontaneous activity in a novel environment was assessed using an open-field test (Muromachi Kikai Co.), where mice were placed in a square arena and their movements were tracked for 10 min to measure travel distance, speed, and activity time using video tracking software (ANY maze; Muromachi Kikai Co.).

Rotarod test

Motor coordination and balance were assessed using an accelerating rotarod test (Muromachi Kikai Co.), where mice were habituated at low speed before being tested with increasing rotation speed. Each mouse underwent two trials, and the average time spent on the rod was used for statistical comparison.

Paraffin-embedded tissue sample Preparation and staining

After perfusion fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde fixative, both knees of mice were removed. For demineralization, the knee joints were immersed in EDTA solution at 4 °C for 1 week. The paraffin section and HE staining were conducted according to Koyama’s report66. Safranin staining performed with Weigert’s iron hematoxylin working solution (Muto Chemical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), staining with fast green solution (Muto Chemical Co. Ltd.), immersion in 1% acetic acid solution for 10 s, and immediate staining with 0.1% safranin O solution (Muto Chemical Co. Ltd.). To assess the validity of the model, HE- and safranin-stained specimens were used to confirm that the cartilage tissue was destroyed. Knee pain was assessed morphologically using the Mankin score used to assess the severity of cartilage damage (Table 1), scoring the right and left knee joints in all the mice67,68. Higher scores indicate more severe cartilage damage. After HE staining, the evaluation of knee joint inflammation was performed using ImageJ 1.54 software (https://imagej.net/, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The quantification of inflammatory cell infiltration was assessed by measuring the cell density (number of inflammatory cells per unit area) in the synovial membrane and the infrapatellar fat pad.

Immunostaining

The procedures were performed according to the protocol described by Koyama et al.66. After perfusion fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, the L4-DRG and knee joints of the mice were removed. Knee joints were prepared as paraffin-sectioned specimens as described above, and DRGs as frozen section specimens. The macrophage marker, F4/80 rat monoclonal antibody (1:100; ab6640, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or the small DRG cell marker, peripherin rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100; 17399-1-AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA) were used as the primary antibody. Alexa488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:500; Peripherin, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) or rat IgG antibody (1:500; F4/80, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used as secondary antibodies. The stained slides were observed and analyzed using a BX53 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The quantification of immunopositive cells was performed using ImageJ software with an automatic thresholding method (Auto Thresholding). The quantification of inflammatory cell infiltration was assessed by measuring the cell density (number of F4/80-positive macrophages per unit area) in the synovial membrane and the infrapatellar fat pad.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) method

Under deep anesthesia, the knee joints were removed, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and crushed. The procedures of RNA purification and qPCR were performed according to the protocol described by Koyama et al.66. Primer sequences see Table 2. The analysis was performed by correcting the measured values of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α using the measured value of GAPDH.

Tracer analysis

Fast Blue (Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA) and Fluoro-gold (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemicals Corporation) were used as the retrograde tracer. Fast Blue and Fluoro-gold was used at 1% (10 mg/mL), 2% (20 mg/mL) in a saline solution, respectively. Using a Hamilton syringe, 10 µL of Fast Blue was injected into the knee joint. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia induced by sevoflurane, and 24 h after nerve tracer administration, the knee joints and L4 dorsal root ganglions (DRGs) were harvested for morphological analysis by Nissl staining and fluorescent immunostaining using an anti-Peripherin antibody. The stained slides were observed and analyzed using a BX53 microscope (Olympus Corporation). Neurons were categorized into small neurons (nuclear diameter < 30 μm) and large neurons based on morphological criteria.

Western blotting analysis

The left and right knee joints were harvested while ensuring that the synovial membrane remained intact. The femur, tibia, and fibula were carefully separated at the closest possible point to the joint to preserve the entire knee structure. The obtained whole knee joints were then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized for protein extraction. After electrophoresis (30 mA for 90 min) on an SDS-PAGE gel, the proteins were transferred (10 V for 90 min) onto a membrane (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, IPVH00010) in a transcription device. Primary antibody reactions were performed using antibodies such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP; 1:1000; ZRB1267-25UL, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), TAC1 [the precursor to Substance P (SP); 1:1000; 13839-1-AP, Proteintech], and GAPDH (1:300; MAB374, Merck KGaA). TAC1 (tachykinin precursor 1) is a gene that encodes a precursor protein called preprotachykinin-1. This precursor protein is important for the production of several neuropeptides including SP. The procedures were performed according to the protocol described by Koyama et al.69. Western blot signal quantification was performed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The band intensity of CGRP and TAC1 was measured and normalized to GAPDH as an internal control. Three independent experiments were conducted, and the average values were calculated. The complete raw data for the Western blotting analysis are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Agonist experiments

Six days after the PRF treatment, a CGRP agonist (1161/100 U, Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and an SP agonist (S8009, LKT Laboratories, Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) dissolved in saline were injected into the knee joints. The dose of each agonist (CGRP: 5 ng; SP, 100 ng) was determined by referring to the following papers: CGRP70 and SP71. The mice were divided into four groups: saline-only group, 5 ng CGRP-injected group, 100 ng SP-injected group, and both agonist-injected groups. One day after the agonist injection, two behavioral tests were performed, and RNA was sampled from the joint for qPCR.

Statistical methods

In all studies comparing two groups, Student’s t-test was used. For comparisons involving multiple groups, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc tests was performed as appropriate. Specifically, for Fig. 6, a one-way ANOVA was used to compare the effects of CGRP and SP agonists, followed by post-hoc multiple comparison tests. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. For correlation analysis, separate linear regression models (Pearson correlation) were applied to the sham and PRF groups to examine the relationship between synovitis markers (H&E, F4/80) and behavioral test results. The coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated for each correlation. Results of statistical analysis were considered significant at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared to untreated (†p vs. sham normal, ♭p vs. PRF normal). The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Study approval

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Osaka University (Approval No. 28-071-004) and followed by the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Additionally, the study complied with the ARRIVE guidelines. Every effort was made to reduce the number of animals used and to alleviate their distress. If any abnormalities or predefined humane endpoints were observed—such as impaired feeding or drinking, respiratory distress, self-injury, or rapid weight loss of 20% or more over several days—the animals were promptly euthanized via intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (200 mg/kg).

Data availability

Data and materials availabilityAll relevant data are within this paper.

References

Sluijter, M. E. & Imani, F. Evolution and mode of action of pulsed radiofrequency. Anesth. Pain Med. 2, 139–141. https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm.10213 (2013).

Van Zundert, J. et al. Pulsed radiofrequency adjacent to the cervical dorsal root ganglion in chronic cervical radicular pain: a double blind Sham controlled randomized clinical trial. Pain 127, 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.002 (2007).

Simopoulos, T. T., Kraemer, J., Nagda, J. V., Aner, M. & Bajwa, Z. H. Response to pulsed and continuous radiofrequency lesioning of the dorsal root ganglion and segmental nerves in patients with chronic lumbar radicular pain. Pain Physician. 11, 137–144 (2008).

Makharita, M. Y., Bendary, E., Sonbul, H. M., Ahmed, Z. M., Latif, M. A. & S. E. S. & Ultrasound-guided pulsed radiofrequency in the management of thoracic postherpetic neuralgia: A randomized, Double-blinded, controlled trial. Clin. J. Pain. 34, 1017–1024. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000629 (2018).

Yan, J. & Zhang, X. M. A randomized controlled trial of ultrasound-guided pulsed radiofrequency for patients with frozen shoulder. Med. (Baltim). 98, e13917. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013917 (2019).

Kroll, H. R. et al. A randomized, double-blind, prospective study comparing the efficacy of continuous versus pulsed radiofrequency in the treatment of lumbar facet syndrome. J. Clin. Anesth. 20, 534–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.05.021 (2008).

Agarwal, A. et al. Radiofrequency treatment of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia (Conventional vs. Pulsed): A prospective randomized control study. Anesth. Essays Res. 15, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.4103/aer.aer_56_21 (2021).

Vanneste, T., Van Lantschoot, A., Van Boxem, K. & Van Zundert, J. Pulsed radiofrequency in chronic pain. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 30, 577–582. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000502 (2017).

Garcia-Sanchez, T. et al. Successful tumor electrochemotherapy using sine waves. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 67, 1040–1049. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2019.2928645 (2020).

Park, D. & Chang, M. C. The mechanism of action of pulsed radiofrequency in reducing pain: a narrative review. J. Yeungnam Med. Sci. 39, 200–205. https://doi.org/10.12701/jyms.2022.00101 (2022).

Brasil, L. J., Marroni, N., Schemitt, E. & Colares, J. Effects of pulsed radiofrequency on a standard model of muscle injury in rats. Anesth. Pain Med. 10, e97372. https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm.97372 (2020).

Usselman, R. J., Hill, I., Singel, D. J. & Martino, C. F. Spin biochemistry modulates reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by radio frequency magnetic fields. PLoS One. 9, e93065. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093065 (2014).

Xu, X., Fu, S., Shi, X. & Liu, R. Microglial BDNF, PI3K, and p-ERK in the spinal cord are suppressed by pulsed radiofrequency on dorsal root ganglion to ease SNI-Induced neuropathic pain in rats. Pain Res. Manag. 2019 (5948686). https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5948686 (2019).

Teixeira, A. & Sluijter, M. E. Intravenous application of pulsed radiofrequency-4 case reports. Anesth. Pain Med. 3, 219–222. https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm.10242 (2013).

Schianchi, P. M., Sluijter, M. E. & Balogh, S. E. The treatment of joint pain with Intra-articular pulsed radiofrequency. Anesth. Pain Med. 3, 250–255. https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm.10259 (2013).

Choi, S. et al. Inflammatory responses and morphological changes of radiofrequency-induced rat sciatic nerve fibres. Eur. J. Pain. 18, 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00391.x (2014).

Pitcher, T., Sousa-Valente, J. & Malcangio, M. The monoiodoacetate model of osteoarthritis pain in the mouse. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/53746 (2016).

van Lent, P. L. et al. Crucial role of synovial lining macrophages in the promotion of transforming growth factor beta-mediated osteophyte formation. Arthritis Rheum. 50, 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.11422 (2004).

Blom, A. B. et al. Synovial lining macrophages mediate osteophyte formation during experimental osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 12, 627–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2004.03.003 (2004).

Dainese, P. et al. Association between knee inflammation and knee pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 30, 516–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2021.12.003 (2022).

Erdine, S., Bilir, A., Cosman, E. R. & Cosman, E. R. Jr. Ultrastructural changes in axons following exposure to pulsed radiofrequency fields. Pain Pract. 9, 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00317.x (2009).

Hata, J. P. K. et al. Pulsed radiofrequency current in the treatment of pain. Crit. Rev. Phys. Rehabil Med. 23, 213–240 (2011).

Goldstein, M. E., House, S. B. & Gainer, H. NF-L and peripherin immunoreactivities define distinct classes of rat sensory ganglion cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 30, 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.490300111 (1991).

Russell, F. A., King, R., Smillie, S. J., Kodji, X. & Brain, S. D. Calcitonin gene-related peptide: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 94, 1099–1142. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00034.2013 (2014).

Stucky, C. L., Lewin, G. R. & Isolectin B(4)-positive and -negative nociceptors are functionally distinct. J. Neurosci. 19, 6497–6505. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06497.1999 (1999).

Bennett, D. L. et al. CGRP and IB4 expression in retrogradely labelled cutaneous and visceral primary sensory neurones in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 206, 33–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3940(96)12418-6 (1996).

Barabas, M. E., Kossyreva, E. A. & Stucky, C. L. TRPA1 is functionally expressed primarily by IB4-binding, non-peptidergic mouse and rat sensory neurons. PLoS One. 7, e47988. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047988 (2012).

Aso, K. et al. Nociceptive phenotype alterations of dorsal root ganglia neurons innervating the subchondral bone in Osteoarthritic rat knee joints. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 24, 1596–1603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.009 (2016).

Bullock, C. M. & Kelly, S. Calcitonin Gene-Related peptide receptor antagonists: beyond migraine Pain—A possible analgesic strategy for osteoarthritis?? Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 17, 375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-013-0375-2 (2013).

Moilanen, L. J. et al. Monosodium iodoacetate-induced inflammation and joint pain are reduced in TRPA1 deficient mice–potential role of TRPA1 in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 23(11), 2017–2026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2015.09.008 (2015).

Vallejo, R. et al. Pulsed radiofrequency modulates pain regulatory gene expression along the nociceptive pathway. Pain Physician. 16 (5), E601–E613 (2013).

Jiang, R. et al. Pulsed radiofrequency to the dorsal root ganglion or the sciatic nerve reduces neuropathic pain behavior, decreases peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokines and spinal β-catenin in chronic constriction injury rats. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 14, rapm–2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2018-100032 (2019).

Sluijter, M. E., Teixeira, A., Vissers, K., Brasil, L. J. & van Duijn, B. The Anti-Inflammatory action of pulsed Radiofrequency-A hypothesis and potential applications. Med. Sci. (Basel). 11 (3), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci11030058 (2023).

Cho, H. K. et al. Changes in pain behavior and glial activation in the spinal dorsal Horn after pulsed radiofrequency current administration to the dorsal root ganglion in a rat model of lumbar disc herniation: laboratory investigation. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 19 (2), 256–263. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.5.SPINE12731 (2013).

Cho, H. K. et al. Changes in Neuroglial Activity in Multiple Spinal Segments after Caudal Epidural Pulsed Radiofrequency in a Rat Model of Lumbar Disc Herniation. Pain Phys. 19(8), E1197–E1209 (2016).

Park, H. W. et al. Pulsed radiofrequency application reduced mechanical hypersensitivity and microglial expression in neuropathic pain model. Pain Med. 13 (Issue 9), 1227–1234 (2012).

Chen, R. et al. High-voltage pulsed radiofrequency improves ultrastructure of DRG and enhances spinal microglial autophagy to ameliorate neuropathic pain induced by SNI. Sci. Rep. 14, 4497. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55095-5 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. Pulsed radiofrequency on DRG inhibits hippocampal neuroinflammation by regulating spinal GRK2/p38 expression and enhances spinal autophagy to reduce pain and depression in male rats with spared nerve injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 127, 111419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2023.111419 (2024).

Zhao, J., Wang, Z., Xue, H. & Yang, Z. Clinical efficacy of repeated intra-articular pulsed radiofrequency for the treatment of knee joint pain and its effects on inflammatory cytokines in synovial fluid of patients. Exp. Ther. Med. 22 (4), 1073. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2021.10507 (2021).

Moore, D. et al. Characterisation of the effects of pulsed radio frequency treatment of the dorsal root ganglion on cerebrospinal fluid cellular and peptide constituents in patients with chronic radicular pain: A randomised, triple-blinded, controlled trial. J. Neuroimmunol. 343, 577219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2020.577219 (2020).

Errea, O. et al. The disruption of mitochondrial axonal transport is an early event in neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation. 12, 152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-015-0375-8 (2015).

Yan, J. G., Matloub, H. S., Sanger, J. R., Zhang, L. L. & Riley, D. A. Vibration-induced disruption of retrograde axoplasmic transport in peripheral nerve. Muscle Nerve. 32(4), 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.20379 (2005).

Pastrak, M. et al. Safety of conventional and pulsed radiofrequency lesions of the dorsal root entry zone complex (DREZC) for interventional pain management: A systematic review. Pain Ther. 11, 411–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-022-00378-w (2022).

Jia, Y. et al. Effectiveness and safety of high-voltage pulsed radiofrequency to treat patients with primary trigeminal neuralgia: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled study. J. Headache Pain. 24, 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-023-01629-7 (2023).

Wan, C. F. et al. Bipolar High-Voltage, Long-Duration Pulsed Radiofrequency Improves Pain Relief in Postherpetic Neuralgia. Pain Phys. 19(5), E721–E728 (2016).

Sisken, B. F., Jacob, J. M. & Walker, J. L. Acute treatment with pulsed electromagnetic fields and its effect on fast axonal transport in normal and regenerating nerve. J. Neurosci. Res. 42 (5), 692–699. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.490420512 (1995).

Tohyama, M. Molecular brain and functional neuroanatomy.

De Logu, F., Nassini, R., Landini, L. & Geppetti, P. Pathways of CGRP release from primary sensory neurons. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 255, 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2018_145 (2019).

Powell, R. et al. Inhibiting endocytosis in CGRP(+) nociceptors attenuates inflammatory pain-like behavior. Nat. Commun. 12, 5812. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26100-6 (2021).

De Logu, F. et al. Schwann cell endosome CGRP signals elicit periorbital mechanical allodynia in mice. Nat. Commun. 13, 646. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28204-z (2022).

Toriyama, Y. et al. Pathophysiological function of endogenous calcitonin gene-related peptide in ocular vascular diseases. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 1783–1794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.02.017 (2015).

Steinhoff, M. S., von Mentzer, B., Geppetti, P., Pothoulakis, C. & Bunnett, N. W. Tachykinins and their receptors: contributions to physiological control and the mechanisms of disease. Physiol. Rev. 94, 265–301. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00031.2013 (2014).

Payan, D. G. Neuropeptides and inflammation: the role of substance P. Annu. Rev. Med. 40, 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.40.020189.002013 (1989).

Rosenkranz, M. A. Substance P at the nexus of Mind and body in chronic inflammation and affective disorders. Psychol. Bull. 133, 1007–1037. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.1007 (2007).

Corrigan, F., Vink, R. & Turner, R. J. Inflammation in acute CNS injury: a focus on the role of substance P. Br. J. Pharmacol. 173, 703–715. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13155 (2016).

Bhatia, M. H(2)S and substance P in inflammation. Methods Enzymol. 555, 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.mie.2014.11.024 (2015).

Donaldson, L. F., Harmar, A. J., McQueen, D. S. & Seckl, J. R. Increased expression of preprotachykinin, calcitonin gene-related peptide, but not vasoactive intestinal peptide messenger RNA in dorsal root ganglia during the development of adjuvant monoarthritis in the rat. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 16, 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-328x(92)90204-o (1992).

Lee, Y. et al. Coexistence of calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P-like peptide in single cells of the trigeminal ganglion of the rat: immunohistochemical analysis. Brain Res. 330, 194–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(85)90027-7 (1985).

Wiesenfeld-Hallin, Z. et al. Galanin-mediated control of pain: enhanced role after nerve injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 89, 3334–3337. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.89.8.3334 (1992).

Le Greves, P., Nyberg, F., Terenius, L. & Hokfelt, T. Calcitonin gene-related peptide is a potent inhibitor of substance P degradation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 115, 309–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2999(85)90706-x (1985).

Ma, Q. in Itch: Mechanisms and Treatment Frontiers in Neuroscience (eds E. Carstens & T. Akiyama) (2014).

Dunnick, C. A., Gibran, N. S. & Heimbach, D. M. Substance P has a role in neurogenic mediation of human burn wound healing. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 17, 390–396. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004630-199609000-00004 (1996).

Cosman, E. R. Jr. & Cosman, E. R. Sr. Electric and thermal field effects in tissue around radiofrequency electrodes. Pain Med. 6, 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00076.x (2005).

Wertman, V., Gromova, A., La Spada, A. R. & Cortes, C. J. Low-Cost gait analysis for behavioral phenotyping of mouse models of neuromuscular disease. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/59878 (2019).

Harada, S. et al. A mouse model of autoimmune inner ear disease without endolymphatic hydrops. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1870 (5), 167198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2024.167198 (2024). Epub 2024 Apr 25. PMID: 38670439.

Koyama, Y. et al. A new therapy against ulcerative colitis via the intestine and brain using the Si-based agent. Sci. Rep. 12, 9634. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13655-7 (2022).

Pritzker, K. P. et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 14, 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.014 (2006).

Mankin, H. J., Dorfman, H., Lippiello, L. & Zarins, A. Biochemical and metabolic abnormalities in articular cartilage from osteo-arthritic human hips. II. Correlation of morphology with biochemical and metabolic data. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 53, 523–537 (1971).

Koyama, Y. et al. Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (FALS)-linked SOD1 mutation accelerates neuronal cell death by activating cleavage of caspase-4 under ER stress in an in vitro model of FALS. Neurochem Int. 57, 838–843 (2010).

De Logu, F. et al. Migraine-provoking substances evoke periorbital allodynia in mice. J. Headache Pain. 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-0968-1 (2019).

Iwamoto, I., Tomoe, S., Tomioka, H. & Yoshida, S. Substance P-induced granulocyte infiltration in mouse skin: the mast cell-dependent granulocyte infiltration by the N-terminal peptide is enhanced by the activation of vascular endothelial cells by the C-terminal peptide. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 87, 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb02975.x (1992).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant number JP 17K11108 and JST SPRING Grant Number JPMJSP2138. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing and the Center for Medical Research and Education, Graduate School for Medicine, Osaka University for technical support.

Funding

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant number JP 17K11108, 21K08992 and JST SPRING Grant Number JPMJSP2138.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Y and Y.K. designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. S.H. Y.K. H.U. A.T. and Y.M. performed experiments and quantifications. Y.F. and S.S. supervised study and provided intellectual directions. All authors discussed the findings and commented on this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the research protocol approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Osaka University School of Medicine (Approval No. 28-071-004) and the ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuba, T., Koyama, Y., Uematsu, H. et al. Elucidation of the treatment mechanism of pulsed radiofrequency based on its antiinflammatory effects. Sci Rep 15, 33611 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19045-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19045-z