Abstract

Gallstone disease (GD) is a prevalent gastrointestinal disorder worldwide, closely associated with obesity, metabolic diseases, and liver fibrosis. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between liver fibrosis and waist circumference to height ratio (LFWHR) with GD and to construct a nomogram model to predict gallstones. A total of 8694 participants from the 2017–2023 NHANES database were included in this study. Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between LFWHR and GD, and subgroup analyses and interaction tests were performed. A predictive model was established using the absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and logistic regression for multivariate feature selection. Nomograms were created to demonstrate the predictive model. The model was evaluated using the area under the ROC curve, calibration curve, and decision curve. Finally, we performed interpretability analysis by calculating SHAP values and plotting force diagrams and swarm diagrams. In the fully adjusted multivariate logistic regression model (Model 3), each unit increase in LFWHR was associated with a 51% higher likelihood of gallstone formation [OR 1.51 (95% CI 1.30–1.75)]. After stratifying by LFWHR, the Q3 level was associated with a higher risk of gallstones [OR 1.74 (95% CI 1.35–2.26)], and the Q4 level was also associated with a higher risk of gallstones [OR 1.75 (95% CI 1.33–2.32)] compared to the Q1 level. This correlation was stronger in people under 60 years of age. After feature screening, nomograms and individual nomograms were constructed for the predictive model of gallstones, yielding an AUC of 0.767 (95% CI, 0.747–0.787). The DCA analysis of the present model indicated a net benefit in the high-risk threshold range of 2–93%. The blue bars in the important figure indicate the mean size of the SHAP value, which was 0.385 for LFWHR. The swarm plot demonstrates the direction and size of the sample contribution to gallstones for each variable. We found for the first time that elevated levels of LFWHR were significantly associated with a high incidence of gallstones, and the nomogram prediction model constructed using LFWHR has potential clinical predictive value. Clinicians can utilize this tool to identify high-risk factors for gallstones at an early stage and reduce the incidence of gallstones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gallstone disease (GD) is one of the more common chronic digestive disorders worldwide and its incidence shows a clear geographic epidemiologic trend1. According to global epidemiologic survey data, its prevalence is 5–6% in India, 10–15% in the United States, and as high as 20% in Europe, showing an increasing trend year by year2,3,4,5. Cirrhosis is the end stage of liver fibrosis with high morbidity and mortality, which is characterized by severe bleeding from fundic esophageal varices, intractable ascites, hepatic encephalopathy and jaundice6. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017, more than 1.32 million people died from cirrhosis, accounting for 2.4% of global deaths7. GD is strongly associated with gender, age, lifestyle, obesity, metabolic disorders, and liver fibrosis, causing a significant health burden worldwide8,9,10. The prevalence of gallstones in patients with cirrhosis has been reported in the literature to be approximately 23% with an annual incidence of 3.4%[11], whereas in the general population, the prevalence is as high as 10–30%12.

The global prevalence of gallstone disease has been increasing in recent years, and there is an urgent need to identify new risk factors and develop effective predictive models to facilitate early prevention of gallstones. Previous studies have established a relationship between hepatic fibrosis and gallstone formation, and several studies have shown that increased liver stiffness is associated with a higher risk of gallstones13,14. However, our study innovatively introduced LFWHR, a new metric that combines the assessment of liver fibrosis with anthropometric measurements, providing a new perspective on gallstone pathophysiology15,16. LFWHR represents the ratio of hepatic fibrosis to waist-height, and is calculated as LFWHR = ln[Liver fibrosis (kPa) ×Waist circumference (cm)/Height (cm)]. The use of LFWHR as a predictive tool is supported because of its ability to capture the complex interactions between liver health and metabolic risk factors17. SHAP stands for Shapley additive interpretation, which is a tool used to interpret machine learning models. In addition, using SHAP analysis improves the interpretability of the model by visualizing the decision-making process18.

This study used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database to investigate the correlation between LFWHR and GD. We used an integrated approach that included multiple logistic regression, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression for feature selection, and SHAP analysis for model interpretation. Our goal was to construct a column-line graph that not only predicts gallstone risk but also elucidates the contribution of individual risk factors, thereby facilitating individualized prevention strategies. This study is expected to contribute to the existing body of knowledge by providing a robust predictive model that can be easily integrated into clinical practice. By clarifying the role of LFWHR in gallstone formation and elucidating the predictive power of nomograms, we aim to improve the early detection of gallstones and ultimately reduce their incidence. In contrast to previous studies that focused mainly on the following aspects compared to single risk factors or limited clinical indicators, our study innovatively combined liver fibrosis assessment with anthropometric measurements via LFWHR to provide a more comprehensive GD risk assessment. This new approach not only enriches the understanding of the pathogenesis of GD, but also provides a more precise tool for predicting the occurrence of the disease, which is expected to fill the gaps in existing studies and provide new perspectives for the prevention and treatment of GD.

Methods

Study population

The data for the study were obtained from the NHANES database, which is a health survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), and the researcher was able to apply for free access to the NHANES database (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/) to download all relevant data. Each cycle of data consists of five sections: Demographics, Dietary, Examination, Laboratory, and Questionnaire. All NHANES data have been approved by the Ethics Committee and participants have signed a written informed consent form prior to administering the questionnaire, so there is no need to reapply for NHANES-related research. NHANES-related studies did not need to be approved by the ethics committee again.

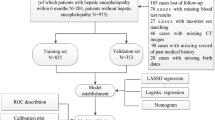

A search of all NHANES data revealed that only data on gallstones were involved in the questionnaire moderation from 2017– March 2020 and August 2021–August 2023, so we finalized this period and wrote it as 2017–2023 combined. Our study aimed to assess the predictive utility of LFWHR for gallstone development and to explore the correlation between LFWHR and gallstone prevalence and interpretable analyses of SHAP. Initially, our study included 17024 participants, and then we excluded 3489 participants who lacked data on ultrasound transient elastography and who were younger than 20 years of age, as well as 2550 participants who lacked data on gallstones and 2291 participants who lacked data on covariates. A final total of 8694 participants were included in the study. Figure 1 illustrates the specific screening process.

Variables

Definition of LFWHR and gallstones

Elastography measurements are obtained in the NHANES Mobile Examination Center (MEC) using the FibroScan Model 502 V2 Touch equipped with medium (M) or extra-large (XL) wand (probe). Instantaneous elastography has been cleared by the FDA as a test for the evaluation of liver fibrosis. The FibroScan® machine has also incorporated a novel physical parameter (controlled attenuation parameter or CAP™), which measures the ultrasound attenuation related to the presence of hepatic steatosis. The CAP measurements are recorded concurrently with liver stiffness measurements, which indirectly reflect the degree of hepatic steatosis and liver fibrosis. Elastography examinations are performed by NHANES examiners, including health technologists (HTs), radiologic technologists (RTs), and clinicians (registered nurses) trained and certified by NHANES staff and the equipment manufacturer (Echosens™ North America). Examinations are conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. NHANES body measurements are used to estimate the prevalence of overweight and obesity among U.S. adolescents and adults and to examine the relationship between body weight and the health and nutritional status of the U.S. population. LFWHR is calculated using the formula: LFWHR = ln[Liver fibrosis (kPa) ×Waist circumference (cm)/Height (cm)]. Statistics for gallstones were obtained from the MCQ questionnaire, “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told {you/SP} that {you/s/he} had gallstones?” to determine whether or not presence of gallstones.

Covariates information

Based on previous literature and clinical experience, we selected a number of composite covariates that may have a confounding effect on gallstones. NHANES collected demographic and health-related data through household interviews. These covariates included basic personal information such as age, gender, race, education level, marital status, occupation, poverty level index, body mass index (BMI), arm circumference, waist circumference, height, liver fibrosis, hepatic steatosis were obtained from examination data. “Ever have 4/5 or more drinks every day” to determine alcohol consumption. “Smoked at least 100 cigarettes in life” to determine smoking status. Hypertension, high cholesterol level, angina, coronary heart disease, heart attack, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), thyroid problem, arthritis, cancer - the presence or absence of the twelve diseases was determined by a “Yes” or “No” answer. Diabetes was defined as “Yes” or “No” and “Borderline”.

Statistical analysis

R software (version 4.3.3) was used for statistical analysis. Although the NHANES survey employed various complex sampling designs, our analysis utilised samples from only two study phases to estimate health-related data. First, participants were divided into four groups (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4) based on quartile levels of LFWHR. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) if they followed a normal distribution. Intergroup differences were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). If they did not follow a normal distribution, they were expressed as median (interquartile range) [M (P₂₅, P₇₅)], and intergroup comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (percentages) [n (%)], and intergroup differences were analysed using the Chi-squared test. Three models (Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3) were then constructed using multiple logistic regression to explore the relationship between LFWHR and GD. Model 1 included only LFWHR as a predictor. Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, and education level. Model 3 included additional predictors: occupation, poverty level index, BMI, arm circumference, hepatic steatosis, alcohol consumption, smoked status, high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, diabetes, angina, coronary heart disease, heart attack, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, COPD, thyroid problems, arthritis, and cancer. These models were selected based on the principle of progressively adjusting for potential confounding factors, ranging from basic demographic variables to more comprehensive health-related indicators. This approach allows us to assess the independent effect of LFWHR on GD risk while controlling for various levels of confounding factors. The generalised variance inflation factor (GVIF) test was employed, and the GVIF^(1/(2×df)) for all variables in the multiple logistic regression model was found to be less than 2.0. This indicated that the model estimates were reliable and there was no significant multicollinearity. To further elucidate this relationship, subgroup analysis and interaction tests were conducted. Subsequently, the final variables for the predictive model were selected using the minimum absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and multivariate logistic regression. Additionally, the dataset was randomly divided in a 6:4 ratio for internal validation, with ROC validation curves and DCA decision curves plotted for both the training and testing sets. Nomograms and individualized nomograms were utilized to illustrate the predictive models. Finally, interpretive analysis was conducted by calculating SHAP values and plotting force plots, importance plots, and beehive plots. Statistical analyses were performed with two-tailed tests, and the significance level was set at α = 0.05, with P < 0.05 indicating statistically significant differences.

Results

Participant characteristics

The basic characteristics of the 8694 participants are shown in Table 1. Participants were stratified according to the quartiles of LFWHR. There were 2174 participants in Q1, accounting for 25.01%, of whom 73.05% were aged ≤ 60 years, 26.95% were aged > 60 years, 42.96% were male, and 57.04% were female. Participants in Q2 numbered 2173, accounting for 24.99% of the total, with 65.67% aged ≤ 60 years and 34.33% aged > 60 years, 50.62% male and 49.38% female. Q3 had 2173 participants, accounting for 24.99% of the total, with 61.99% aged ≤ 60 years and 38.01% aged > 60 years, 52.37% male and 47.63% female. Q4 had 2174 participants, accounting for 25.01% of the total, with 56.72% aged ≤ 60 years, 43.28% aged > 60 years, 50.41% male, and 49.59% female. Analysis through LFWHR quartile stratification revealed significant differences among participants in terms of age, gender, race, education level, marital status, occupation, poverty level index, BMI, arm circumference, waist circumference, liver fibrosis, hepatic steatosis, alcohol consumption, smoked status, hypertension, high cholesterol level, diabetes, angina, coronary heart disease, heart attack, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, COPD, thyroid problems, arthritis, cancer, and gallstones (P < 0.01); whereas no significant differences were observed in height (P > 0.05).

Relationship between the LFWHR and GD

The results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis examining the association between LFWHR and gallstone disease are presented in Table 2. In Model 1 [OR 2.14 (95% CI 1.92–2.39)], Model 2 [OR 2.17 (95% CI 1.93–2.43)], and Model 3 [OR 1.51 (95% CI 1.30–1.75)], the association between LFWHR and gallstones was statistically significant (P < 0.05). This finding suggests that in models that have undergone full adjustment, an increase in LFWHR of one unit is associated with a 51% increase in the risk of gallstones. Subsequent sensitivity analysis demonstrated that this association maintained statistical significance when stratified by LFWHR quartiles (P for trend < 0.05). Compared with Q1 of LFWHR, in the fully adjusted model (Model 3), Q3 [OR 1.74 (95% CI 1.35–2.26)] and Q4 [OR 1.75 (95% CI 1.33–2.32)] had an increased risk of gallstone formation, indicating that the risk of gallstone formation increased by 74% and 75% in Q3 and Q4, respectively.

Subgroup analysis

To further investigate the relationship between LFWHR and GD, we conducted stratified analysis on categorical variables (age, gender, race, smoked status, angina, arthritis, COPD, cancer) following multivariate logistic regression (Fig. 2). The study results demonstrated an interaction between LFWHR and GD (P for interaction < 0.05), primarily dependent on age. Specifically, in individuals aged 60 or younger, an increase of one unit in LFWHR was associated with a 78% increase in the likelihood of gallstone occurrence [OR 1.78 (95% CI 1.14–2.77)]. Conversely, this positive association was not evident in individuals over 60 years of age.

LASSO regression for feature screening

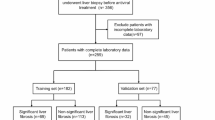

To construct the final predictive model, we employed LASSO regression analysis to preliminarily screen clinical variables. A total of 15 relevant variables were selected, including age, gender, race, occupation, smoked status, BMI, arm circumference, waist circumference, height, diabetes, angina, COPD, arthritis, cancer, and LFWHR (logarithm of the best λ = – 7.101) (Fig. 3).

Using LASSO regression to select features for predicting GD. (A) Regression coefficient curve, where each curve represents the trajectory of the coefficient for each feature. (B) Lasso regression cross-validation profile, where each red dot indicates the mean squared error (MSE) for each λ value. The vertical axis represents the magnitude of the coefficients, and the horizontal axes (top) represent the number of non-zero coefficients in the model, while the horizontal axes (bottom) represent the logarithm of the regularization parameter λ. The left dashed line indicates the minimum value of λ (λmin, log(λ) = – 7.101). To predict gallstones, we use λmin for variable selection.

Logistic regression for further feature screening

We further applied logistic regression analysis to screen the feature variables after LASSO regression analysis. Table 3 displays the results of the multivariate logistic regression, which further selected the following variables associated with the incidence of gallstones: age, gender, race, marital status, occupation, BMI, smoked status, diabetes, angina, COPD, arthritis, cancer, arm circumference, hepatic steatosis, and LFWHR. These 15 variables are independent risk factors for the occurrence of gallstones.

ROC curves for predictive modeling

Following the analysis of the results of the LASSO and multivariate logistic regression analyses, ten important variables were finally identified, including age, gender, race, smoked status, angina, COPD, arthritis, cancer, arm circumference, and LFWHR. The final prediction model was constructed. Subsequently, ROC validation curves were plotted for the training set and test set data respectively, and calibration curves and DCA decision curves were plotted to evaluate the model (Fig. 4). The model showed robust prediction performance, achieving an AUC of 0.767 (95% CI 0.747–0.787) with a sensitivity of 71.30% and a specificity of 70.21%. The calibration curve showed that nomogram prediction was in general agreement with the actual gallstone incidence. DCA analysis showed that the model was of net benefit within the high-risk threshold range of 2–93%, which has important clinical applications.

Construction of the nomogram for prediction

We constructed a nomogram using the final feature variables from the predictive model (age, gender, race, smoked status, angina, COPD, arthritis, cancer, arm circumference, and LFWHR) to provide an intuitive and clinically convenient visual tool for predicting gallstones. Each feature variable in the chart is assigned a score, and the scores of different risk factor intensities are summed up, with the total score indicating the likelihood of gallstone occurrence in the subject. Additionally, we also present specific individual nomograms (Fig. 5).

Interpretability analysis of SHAP values

Finally, we constructed a nomogram with the final variables from the predictive model (age, gender, race, smoked status, angina, COPD, arthritis, cancer, arm circumference, and LFWHR) and trained an XG Boost model to calculate SHAP values, followed by plotting force plots, importance plots, and beeswarm plots. The force plot illustrates the individual’s actual factors: a 54-year-old non-Hispanic white female with an upper arm circumference of 51.5 cm, LFWHR of 3.945, a history of smoked, and arthritis disease, has a high likelihood of developing GD with a risk [f(x) = 0.875]. The force plot more vividly explains the direction and magnitude of the effect of individual variables on the outcome. The importance plot shows that gender has the greatest overall influence (SHAP mean value of 0.645), while the SHAP mean value for LFWHR is 0.385. The beeswarm plot indicates that being female, increasing age, higher LFWHR values, larger upper arm circumference, a history of smoked, and having arthritis, COPD, angina, and cancer all contribute to the formation of gallstones(Fig. 6).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that LFWHR was significantly associated with GD risk. This association remained robust even after adjusting for various confounders, suggesting that LFWHR may be a reliable predictor of GD risk. Our findings are consistent with recent studies that have emphasized the role of liver fibrosis and metabolic factors in the development of gallstones19,20. The new metric of LFWHR, which combines liver fibrosis and anthropometric indices, adds a new dimension to the understanding of the pathophysiology of gallstones21. The positive association between LFWHR and the risk of GD, and the fact that for every one-unit increase in LFWHR, a 51% increase in the odds of GD prevalence [OR 1.51 (95% CI 1.30–1.75)], emphasizes the importance of considering liver health in the context of metabolic disease22. This was supported by stratified analyses, which showed that the risk was more pronounced in the higher quartiles of the LFWHR [OR 1.75 (95%CI 1.33–2.32)], with particular subgroup analyses showing a higher chance of gallstone incidence in those under 60 years of age or younger [OR 1.78 (95%CI 1.14–2.77)]23. These findings are consistent with a growing body of literature linking liver fibrosis to an increased risk of metabolic complications, including GD24. In particular, middle-aged women under 60 years of age have a significantly higher prevalence than men, which may be related to changes in their own estrogen levels, which decrease gallbladder contractile function and thus increase the risk of GD25.

However, the potential mechanisms regarding the association between LFWHR and the risk of GD have not been fully clarified in current studies.LFWHR may influence gallstone formation through multiple pathways, including alterations in bile composition and gallbladder function. In addition, interactions between LFWHR and factors such as insulin resistance, excess visceral adiposity, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and chronic inflammation may also play a role in the development of GD26. In particular, metabolic factors such as hepatic fibrosis occurring in obese populations with relatively large waist heights are more likely to contribute to the development of GD27. Future studies could further explore these mechanisms, as well as the relationship between LFWHR and factors such as blood glucose and lipid levels, in order to more fully understand its role in GD28,29. Although we considered a variety of factors in our study, there may still be unmeasured confounders, such as dietary choices, sleep status, and socioeconomic factors, which may also influence the risk of GD. Dietary habits (e.g., high-fat, low-fiber diets) and lower socioeconomic status were both associated with a higher prevalence of GD. Insomnia and insufficient sleep duration may also increase the risk of GD30. These factors may interact with LFWHR and other variables measured in the study (angina, COPD, arthritis, cancer, etc.) to influence gallstone formation. Therefore, future studies should consider incorporating these potential confounders while further validating the relationship between LFWHR and GD to more comprehensively assess the factors affecting GD risk.

The nomogram developed based on LFWHR and other clinical variables provides a clinically useful tool for predicting GD risk. This nomogram can help clinicians identify high-risk individuals early, potentially leading to the implementation of preventive interventions and a reduction in the incidence of GD. We used LASSO regression and logistic regression for feature selection and finally identified ten important variables, including age, gender, race, smoked status, angina, COPD, arthritis, cancer, arm circumference, and LFWHR, to construct the final nomogram prediction model. The performance of this nomogram, achieving an AUC of 0.767 (95%CI 0.747–0.787), with a sensitivity of 71.30% and specificity of 70.21%, indicates that it is a reliable predictor of GD risk. Individual nomograms demonstrate the status of single-sample variables and the probability of developing gallstones. Moreover, calibration curves confirm that the nomogram predictions are essentially consistent with the actual incidence of gallstones. DCA analysis indicates that this model is net-beneficial across a high-risk threshold range of 2–93%, possessing significant clinical application value.

In this study, we developed and validated an LFWHR-based nomogram model for predicting the incidence of GD. This nomogram model provides a clinical tool for predicting GD risk by integrating LFWHR and other clinical variables. It can help clinicians to identify high-risk individuals at an early stage so that preventive interventions can be implemented to reduce the incidence of GD31. For example, for patients predicted to be at high risk by the nomogram, physicians can adopt regular ultrasound examinations to enhance monitoring, and advance lifestyle interventions or medications to prevent gallstone formation or delay disease progression. In addition, the model can be used for patient education to help patients understand their risk factors and increase their attention to disease prevention. In conclusion, the incorporation of LFWHR into the nomogram model not only helps to identify high-risk individuals at an early stage but also may improve management strategies for GD in clinical practice and reduce the burden of disease.

Finally, applying SHAP analysis to our predictive model provides a deeper understanding of each variable’s contribution to GD prediction32. High SHAP values for gender, LFWHR, and other variables such as age emphasize their importance in GD risk prediction33. This model interpretability approach is gaining increasing attention in the fields of machine learning and artificial intelligence, providing valuable tools for translating complex models into clinically actionable insights34. Our beeswarm plot visually illustrates that factors such as being female, increasing age, higher LFWHR values, larger upper arm circumference, a history of smoked, and having arthritis, COPD, angina, and cancer all contribute to the formation of gallstones. Force plots vividly display the specific SHAP values for each variable in selected individuals and the magnitude of influence between variables.

In summary, our study shows that LFWHR is significantly associated with GD risk and can be integrated into predictive models to identify high-risk individuals. The development and validation of this nomogram represent a step forward in the clinical management of GD. Further research is needed to refine our understanding of the role of liver fibrosis in GD and to develop targeted interventions to reduce the global burden of this common disease.

While the NHANES database provides a wealth of data, it has a number of limitations: its self-reported data are susceptible to bias; missing data can be potentially biased; the complex sampling design makes analyses more difficult and the sample sizes of some subgroups are small; the cross-sectional data may not be able to fully determine causality; measurement error and data quality issues are difficult to avoid completely; and, in addition, there may be unmeasured or residual confounders affecting the results. These limitations need to be taken into consideration when interpreting the results of the study.

Conclusion

This study suggests that elevated LFWHR may be associated with an increased incidence of GD. Therefore, nomograms constructed using LFWHR can be used to predict the incidence of GD and have potential clinical predictive value.

Data availability

The original contributions to this study are included in the article. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author, Futao Wang, at wangfutao313@163.com.

References

Peery, A. F. et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the united states: Update 2021. Gastro-Enterol. 162, 621–644 (2022).

Patel, A. M., Yeola, M. & Mahakalkar, C. Demographic and risk factor profile in patients of gallstone disease in central India. Cureus 14, e24993 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Relationship of triglyceride-glucose index to gallstone prevalence and age at first gallstone surgery in American adults. Sci. Rep. 14, 16749 (2024).

Chen, C. H., Lin, C. L., Hsu, C. Y. & Kao, C. H. Risk of gallstones in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A nationwide observational cohort study. Sleep. Breath. 23, 355–362 (2019).

Li, Z. Z. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of gallbladder and biliary diseases from 1990 to 2019. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 15, 2564–2578 (2023).

Ginès, P. et al. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 398, 1359–1376 (2021).

GBD 2017 Cirrhosis Collaborators. The global, regional, and National burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 245–266 (2020).

Luo, X. et al. Gallstones and risk of cancers of the liver, biliary tract and pancreas: A prospective study within two U.S. Cohorts. Br. J. Cancer. 127, 1069–1075 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Insights into modifiable risk factors of cholelithiasis: A Mendelian randomization study. Hepatology 75, 785–796 (2022).

Liepert, A. E., Ancheta, M. & Williamson, E. Management of gallstone disease. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 104, 1159–1173 (2024).

Viscosi, F., Fleres, F., Cucinotta, E. & Mazzeo, C. Management of cholelithiasis in cirrhotic patients. J. Pers. Med. 12, 2060 (2022).

Wang, S. Y., Yeh, C. N., Jan, Y. Y. & Chen, M. F. Management of gallstones and acute cholecystitis in patients with liver cirrhosis: What should we consider when performing surgery?? Gut Liver. 15, 517–527 (2021).

Cho, T. et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease is a risk factor for gallstones: A multicenter cohort study. Hepatol. Res. 55, 663–674 (2025).

Dong, H. et al. Association between fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) and gallstones: An analysis of the NHANES 2017–2020 cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 25, 229 (2025).

Mallick, B. & Anand, A. C. Gallstone disease in Cirrhosis-Pathogenesis and management. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 12, 551–559 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Associations between novel anthropometric indices and the prevalence of gallstones among 6,848 adults: A cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 11, 1428488 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association between metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease and gallstones in the US population using propensity score matching. Sci. Rep. 15, 910 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Development of an interpretable machine learning model associated with heavy metals’ exposure to identify coronary heart disease among US adults via SHAP: Findings of the US NHANES from 2003 to 2018. Chemosphere. 311, 137039 (2023).

Alhamid, M. A. et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in cirrhotic patients: A retrospective study. Chirurgia (Bucur). 116, 34–41 (2021).

Roesch-Dietlen, F. et al. Prevalence of metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) in patients with gallstone disease. Study on a cohort of cases in South–Southeastern Mexico. Rev. Gastroenterol. Mex. (Engl. Ed). 88, 225–231 (2023).

Kumari, R. et al. Gallstone-Associated histopathological changes in liver: A prospective observational study. Cureus 16, e55417 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Diagnostic efficacy of vibration-controlled transient elastography in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease and chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract.. 6722810 (2024).

Cheng, Q. et al. Association of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHHR) and gallstones among US adults aged ≤ 50 years: A cross-sectional study from NHANES 2017–2020. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 265 (2024).

Indre, M. G. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 2D-SWE ultrasound for liver fibrosis assessment in MASLD: A multilevel random effects model meta-analysis. Hepatology https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000001190 (2024).

Yuk, J. S. & Park, J. Y. Menopausal hormone therapy increases the risk of gallstones: Health insurance database in South Korea (HISK)-based cohort study. PLoS ONE. 18, e0294356 (2023).

Unalp-Arida, A. & Ruhl, C. E. Increasing gallstone disease prevalence and associations with gallbladder and biliary tract mortality in the US. Hepatology 77, 1882–1895 (2023).

Rodríguez-Antonio, I. et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Histopathological analysis of metabolic associated fatty liver disease and fibrosis. Ann. Hepatol. 27, 100651 (2022).

Wu, B. et al. Correlation between gallstones and fasting blood glucose to serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio among American adults. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 12, 1528613 (2025).

Zhang, M. et al. Blood lipid metabolism and the risk of gallstone disease: A multi-center study and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 21, 26 (2022).

Hou, Y. et al. Depressive symptoms mediate the association between sleep disorders and gallstone disease: A causal mediation analysis of NHANES 2017–2020. Front. Psychiatry. 16, 1434889 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting sepsis in patients with pyogenic liver abscess. Sci. Rep. 13, 10849 (2023).

Agheli, A. & Aghabayk, K. How does distraction affect cyclists’ severe crashes? A hybrid CatBoost-SHAP and random parameters binary logit approach. Accid. Anal. Prev. 211, 107896 (2024).

Kim, H. J., Kang, T. U., Kim, M. J., Swan, H. & Park, S. M. Long-term weight patterns and physical activity in gallstones. Sci. Rep. 14, 25817 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Construction and SHAP interpretability analysis of a risk prediction model for feeding intolerance in preterm newborns based on machine learning. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 24, 342 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude for the support given by the participants involved in the NHANES study.

Funding

NA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yun Zhao: writing the original article. Feng Wang: data organization and statistical analysis. Guangya Zhang: produced tables and drew charts. Yukun Bie: editing and content revision. Yibin Feng: conceptualization and guidance. Futao Wang: proofreading and finalization. All authors participated and approved the submitted version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the NHANES Institutional Review Board and implemented in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all NHANES participants signed an informed consent form. Details are available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Y., Wang, F., Zhang, Gy. et al. Evaluating the liver fibrosis and waist-to-height ratio(LFWHR) as a gallstone disease predictor: a nomogram model and SHAP analysis. Sci Rep 15, 35189 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19194-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19194-1