Abstract

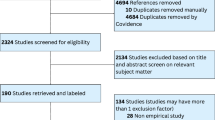

Clinical oncology generates vast, unstructured data that often contain inconsistencies, missing information, and ambiguities, making it difficult to extract reliable insights for data-driven decision-making. General-purpose large language models (LLMs) struggle with these challenges due to their lack of domain-specific reasoning, including specialized clinical terminology, context-dependent interpretations, and multi-modal data integration. We address these issues with an oncology-specialized, efficient, and adaptable NLP framework that combines instruction tuning, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and graph-based knowledge integration. Our lightweight models prove effective at oncology-specific tasks, such as named entity recognition (e.g., identifying cancer diagnoses), entity linking (e.g., linking entities to standardized ontologies), TNM staging, document classification (e.g., cancer subtype classification from pathology reports), and treatment response prediction. Our framework emphasizes adaptability and resource efficiency. We include minimal German instructions, collected at the University Hospital Zurich (USZ), to test whether small amounts of non-English language data can effectively transfer knowledge across languages. This approach mirrors our motivation for lightweight models, which balance strong performance with reduced computational costs, making them suitable for resource-limited healthcare settings. We validated our models on oncology datasets, demonstrating strong results in named entity recognition, relation extraction, and document classification, and showing consistent performance across multiple lightweight architectures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clinical oncology and related disciplines such as radiology or pathology often capture patient-related information in an unstructured or semi-structured way. At the same time, there is an increasing need to use real-world data to enable data-driven therapy decisions as a strategy that complements standardized evidence-based (study-informed) decision making.

In the typical healthcare setting, oncologists must gather vast amounts of information from different data sources, including radiology images and reports, pathology reports, molecular analyses, clinical notes, and patient histories. They rely on these diverse sources to guide diagnosis, the assessment of prognosis and stage, and the decision on therapy. However, much of this data is in free text format within electronic health records (EHR)1,2. Clinicians waste time and resources as they parse these notes by hand. This leads to slow, inconsistent, and error-prone decision-making, especially in resource-limited environments3.

Natural language processing (NLP) offers tools to extract insights from free-text clinical records, with early approaches such as rule-based systems, machine learning methods with hand-engineered features, co-occurrence statistics, and rule-based patterns identifying entities like diseases and treatments4 but struggling to generalise to new datasets5. These methods fail to handle the nuanced language and variability of clinical data. Pretrained language models (LMs), such as BERT6, BioBERT7, and ClinicalBERT8, improve performance on tasks like entity recognition and literature mining by leveraging large biomedical corpora9,10,11,12. Despite these advances, such models focus primarily on classification, lack flexible reasoning capabilities, and are limited in their ability to generate coherent text for summarization or prediction13. Moreover, these models predominantly support English, overlooking the multilingual requirements of many healthcare systems.

Large language models (LLMs), such as GPTs14 and LLaMA15, overcome some of these limitations by handling diverse tasks and adapting to new domains with minimal labeled data. Researchers have used them to summarize medical records, answer questions, and support clinical decisions16,17. More recent work evaluates whether general large language models can handle relation extraction without extensive fine-tuning18. Recent systematic studies have benchmarked GPT-3 and Flan-T5 on relation-extraction datasets, showing that few-shot prompting can match, and sometimes exceed, fully-supervised baselines19. Conversely, a thorough evaluation in the biomedical domain found that GPT-3 in-context learning still lags behind fine-tuned, smaller PLMs for NER and RE20. One study framed relation extraction as a binary classification task and combined an open-source LLM with document retrieval, extracting over 248000 relation triplets from semi-structured biomedical websites21. A case study on acupuncture point locations fine-tuned GPT-3.5 and found it outperformed BioBERT and LSTM22. General-purpose LLMs often fail in specialized fields like oncology. They lack domain-specific knowledge, produce inconsistent reasoning23,24, and require substantial computational resources, which many healthcare institutions cannot afford. Lightweight models provide a practical alternative by delivering strong performance with significantly reduced resource requirements.

Recent research has adapted LLMs for oncology-specific applications, often addressing single tasks such as named entity recognition (NER) or relation extraction25,26,27,28. However, these approaches lack scalability and multilingual flexibility. Newer methods integrate biomedical corpora, retrieval mechanisms, and parameter-efficient fine-tuning to handle complex tasks. Some studies have curated large corpora (e.g., from the TCGA dataset) to build prognostic models or classify cancer subtypes, but these often rely on manual feature engineering or rule-based systems25. Other works used transformer-based models for TNM extraction, disease coding, or limited classification tasks29.

We propose an oncology-specialized NLP framework that combines lightweight models, bilingual adaptability, and advanced reasoning techniques. Given the Swiss healthcare system’s nature, incorporating German alongside English ensures the framework can address the linguistic diversity encountered in clinical practice at institutions like USZ. We curated minimal German instructions from clinical queries at the University Hospital Zurich (USZ) and systematically varied their number (100, 200, 400) to test whether small amounts of bilingual data can transfer domain-specific knowledge effectively across languages. Both bilingual adaptability and lightweight models align with our overarching goal of creating scalable NLP systems that can adapt to diverse healthcare environments, from large hospitals to resource-limited clinics.

Our framework tries to solve key challenges in oncology NLP by integrating instruction tuning, retrieval-augmented generation, and graph-based reasoning. Each component targets specific issues in processing clinical data.

Instruction tuning fine-tunes a pre-trained language model using paired instructions and responses to better follow user directives, and it has become a popular way to align models without reinforcement learning. In specialised domains such as oncology, it can handle named entity recognition, relation extraction, TNM staging, and treatment response prediction with precision. Bilingual instructions in English and German align with real clinical use cases such as ICD-10 coding and treatment classification. However, recent analyses show that this technique has important limitations: it does not enhance a model’s factual knowledge and may even degrade that knowledge if full-parameter tuning is used. A recent evaluation showed that instruction-tuned Llama-2 and Mistral models labelled more entities than their chat-tuned or base counterparts30. A cohort study on lung-cancer reports found that encoder-only transformers still outperformed several instruction-based LLMs, which achieved high precision but suffered from low recall31. Encoder-only models typically require institution-specific fine-tuning to reach clinical accuracy, whereas instruction-tuned generative LLMs can often be deployed in a zero-shot or few-shot fashion. Models often learn to copy response patterns from the instruction data, which can reduce response quality and increase hallucinations32. LoRA-based instruction tuning, which adapts only a small subset of parameters, can partially incorporate domain-specific knowledge, but its benefits depend on model size and do not completely solve domain-adaptation challenges33. Studies developing medical foundation models report that instruction tuning alone cannot compensate for a lack of specialised pre-training; only when combined with extensive domain-specific pre-training do models achieve strong performance across diverse medical tasks34.

RAG improves outputs by retrieving relevant clinical data from trusted sources. External datasets such as MIMIC-IV and curated German oncology reports add real-time context to the model’s responses. The retrieval process connects queries with factual information from oncology corpora. Using hierarchical methods, RAG retrieves critical details efficiently without overwhelming the input with unnecessary context.

Graph-based reasoning ensures outputs are reliable and factually grounded. A knowledge graph integrates resources like UMLS, linking extracted entities to verified medical facts. Relationships between entities, such as treatments and stages, are organized as nodes and edges. Triple graph construction connects entities to authoritative references, reducing ambiguity and improving reasoning. This process strengthens the clinical reliability of model-generated outputs.

Lightweight models spanning a range of architectures and parameter sizes (0.6B–8B) combine these methods to balance efficiency and performance. This includes configurations from the LLaMA and Qwen families as well as the DeepSeek LLM series, each selected for their strong multilingual capabilities, efficient inference, and suitability for retrieval-augmented and graph-based reasoning in oncology. The framework adapts to resource-limited clinical environments while maintaining high accuracy and flexibility across oncology-specific applications.

Our contributions are as follows:

-

1.

Oncology-Specialized Modeling: Lightweight models fine-tuned for oncology tasks like TNM staging, named entity recognition, relation extraction, document classification, and treatment prediction. Benchmarks include datasets like NCBI-Disease, i2b2-2010, and labeled subsets of TCGA.

-

2.

Multilingual Adaptability: Minimal German instructions collected from USZ improve cross-lingual performance on ICD-10 coding and TNM staging. The bilingual framework supports diverse healthcare systems by addressing multilingual requirements.

-

3.

Model Efficiency: Lightweight models such as LLaMA-2-7B deliver high accuracy with lower computational costs. This ensures advanced NLP tools remain accessible to institutions with limited resources.

-

4.

Task Adaptability: The framework applies to diverse tasks, including relation extraction, document classification, and multilingual ICD-10 coding. Models adapt to new domains and tasks.

The integration of instruction tuning, RAG, and graph-based reasoning provides oncology NLP systems that deliver accurate, efficient, and context-aware solutions for multilingual and resource-limited settings.

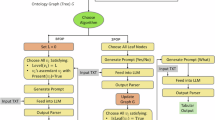

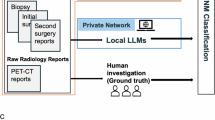

(A) Fine-tuning and evaluation workflow: This panel shows the process of data collection, instruction building, fine-tuning, and evaluation against clinician annotations. (B) Document and graph retrieval: This panel highlights the integration of document retrieval and graph-based reasoning for query-based inference.

Data sources

We use a combination of bilingual clinical datasets and diverse public benchmarks to fine-tune and evaluate our oncology NLP framework. These datasets enable the exploration of bilingual adaptability, cross-lingual generalization, and task scalability.

USZ oncology dataset

The USZ oncology dataset is derived from German-language clinical reports of the University Hospital Zurich, containing both structured and unstructured data from 2,049 unique cancer patients. Patients who had agreed to the general informed consent were included. The dataset comprises around 110 structured datapoints, including ICD diagnoses, TNM annotations, and medications extracted from electronic health records. Data were represented in RDF, encrypted, and securely transferred to institutional repositories. Semantic rules (SHACL) and a validation pipeline ensured harmonization, integrity, and consistency of patient timelines. Treatment lines and drug regimens were reconstructed and corrected with expert input. Unstructured elements such as treatment histories, radiology, histology, and genomic reports were manually annotated by physicians. Diagnoses and genomic information were linked to free-text records via patient IDs, ensuring integration of structured and unstructured data. All methods complied with ethical and regulatory standards. Protocols were approved by the Northwest and Central Swiss Ethics Committee (EKNZ; protocol no. 2020-00347) and ratified by local ethics committees.

Public datasets

Our dataset selection is inspired by the Biomedical Language Understanding and Reasoning Benchmark (BLURB)9, which established a comprehensive evaluation suite for biomedical NLP by combining multiple tasks and datasets. We assembled a diverse set of publicly available resources spanning named entity recognition (NER), relation extraction (RE), natural language inference (NLI), and document classification. This multi-task, multi-domain design enables us to evaluate both the task-specific performance and the cross-task adaptability of our models, reflecting the heterogeneous and complex nature of language encountered in practice.

NER: We use NCBI-Disease35, BC5CDR (Disease/Chem)36, BC2GM37, JNLPBA38, and i2b2-201239 to test how well the model extracts biomedical entities such as diseases, chemicals, or genes from text. These datasets focus on biomedical literature and primarily employ the standard BIO (Beginning-Inside-Outside) labeling scheme.

Relation Extraction: i2b2-201039 and GAD40 measure how well the model links genes, diseases, and treatments. This step tests the model’s ability to identify relations, for example, a gene-disease association or a drug-disease treatment link. The i2b2-2010 dataset centers on clinical narratives, where relationships are defined between problems, test results, and treatments.

NLI: MedNLI41 tests logical reasoning about clinical statements, requiring the model to determine whether a conclusion follows logically from given premises. This task is particularly relevant in oncology, where clinicians must reconcile conflicting findings from reports, pathology notes, or imaging summaries. For instance, determining whether a pathology report implies disease progression based on an imaging report involves reasoning over subtle textual cues.

Document Classification: Document classification addresses the task of assigning labels to entire texts, such as clinical reports, based on their content. We use the Hallmarks of Cancer (HoC)42 dataset and the TCGA Pathology Report Dataset29 for these experiments.

The Hallmarks of Cancer dataset provides multi-class labels aligned with ten canonical hallmarks of cancer, including sustained proliferative signaling, immune evasion, and genomic instability. These categories represent critical biological processes that drive cancer progression. By applying these labels, the model learns to classify biomedical literature according to underlying cancer-related themes.

The TCGA Pathology Report dataset grounds this classification in clinical practice. It includes 9,523 pathology reports spanning 32 distinct cancer types, each processed through OCR and careful post-processing. Beyond cancer-type classification, the TCGA reports include TNM staging annotations (T1–T4, N0–N3, M0–M1). TNM staging provides essential prognostic information and guides treatment decisions. We split this dataset into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% test, ensuring a balanced approach to model development and performance evaluation.

We also incorporate the MSK-IMPACT43 dataset, a curated resource from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. It includes 1,479 patients treated with systemic immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). This dataset provides binary labels for treatment response, where patients are categorized as responders or non-responders based on clinical response criteria, such as the RECIST v1.1 guidelines. Responders include both complete responders (CR), defined as the disappearance of all target lesions, and partial responders (PR), defined as at least a 30% decrease in the sum of the diameters of target lesions. Non-responders encompass patients with stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD).

Methodology

Our methodology transforms pretrained language models into specialized oncology tools by integrating instruction tuning, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and graph-based knowledge integration. In Figure 1, we illustrate the fine-tuning process (Panel A) and the document and graph retrieval mechanisms (Panel B). Panel A demonstrates the end-to-end workflow for building labeled datasets, constructing instructions, and fine-tuning lightweight models. Panel B highlights how the system integrates document retrieval, graph-based reasoning, and query embeddings to generate clinically relevant responses. Together, these steps form the core of our methodology for transforming general-purpose LLMs into oncology-specialized tools.

These components enable the models to process complex oncology data, reason about medical facts, and generate precise predictions for clinical workflows. By emphasizing bilingual adaptability through minimal German instructions and resource-efficient lightweight models, we ensure our approach scales across multilingual and resource-limited healthcare environments.

Our framework proceeds through a sequence of well-defined steps that can be reproduced. We first construct a bilingual instruction dataset and fine-tune lightweight LLaMA variants by minimising the cross-entropy loss

where \(x_i\) denotes an input clinical text, the “instruction” encodes the task, and \(y_i\) is the expected output. During training, we use a batch size of 32 and a learning rate of \(3\times 10^{-5}\) for 3 epochs, with early stopping on the validation loss.

We then embed incoming queries and document chunks using a domain-specific sentence transformer (described below) and index these embeddings in a FAISS vector store. For a query Q and a candidate document D with embeddings \(\phi (Q)\) and \(\phi (D)\), we compute their cosine similarity

and retrieve the top-k documents by similarity. Retrieved passages are concatenated with the query and passed to the fine-tuned LLM. Finally, we enrich the model’s reasoning with a knowledge graph built from external ontologies, encoding entities with TransE embeddings and representing relations as directed edges. This detailed description clarifies the computational steps and hyper-parameters used in our experiments.

Instruction tuning across languages

To fine-tune our lightweight generative language models (LLaMA-2-7B, LLaMA-3.1-8B, LLaMA-3.2-1B, and LLaMA-3.2-3B), we use curated instruction-response pairs in English and German. These instructions simulate real-world oncology queries, such as identifying cancer-related entities, TNM staging annotations, or extracting treatment protocols. Each instruction-response pair provides structured outputs, such as JSON-formatted annotations specifying entity types, attributes, and their spans within the text. For instance, a tumor-related entity recognition query might yield outputs categorizing “lung cancer” or “EGFR-positive adenocarcinoma” with attributes like diagnosis date or molecular markers. Table 1 provides examples of instructions used across different oncology tasks, highlighting their diversity and task-specific objectives. These examples demonstrate how instructions align with tasks like named entity recognition, natural language inference, and relation extraction, ensuring task relevance and improving model generalization44.

To evaluate cross-lingual adaptability, we augment public datasets with minimal German instructions, ranging from 100 to 400 examples. These instructions cover tasks such as ICD coding, TNM staging, and treatment annotation. Training minimizes the instruction tuning loss:

where \(x_i\) represents the input text, “instruction” specifies the task, and \(y_i\) is the expected response. Cross-validation splits are applied to ensure generalization to unseen instructions and languages. The instruction tuning data is publicly available at: https://huggingface.co/datasets/nlpie/Llama2-MedTuned-Instructions.

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG)

Oncology workflows often require reasoning over large, diverse, and evolving datasets. To address this complexity, we integrate retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), which grounds model responses in external knowledge. We use a sentence embedding model, fine-tuned for oncology-specific tasks, to encode user queries (\(Q\)) and candidate documents \(D\) into dense vector representations. These embeddings capture semantic similarity between clinical terms and contexts. To store and index these embeddings efficiently, we use the FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search) library45. FAISS provides high-speed similarity searches across large document collections, enabling real-time retrieval and processing of oncology data. User queries \(Q\) and candidate documents \(D\) are encoded into dense vector representations, with cosine similarity determining their relevance:

Our retrieval pipeline relies on a domain-adapted sentence transformer to produce query and document embeddings. We use the sentence-transformers/paraphrase-multilingual-MiniLM-L12-v2 model, which provides 384-dimensional multilingual embeddings suitable for both English and German clinical texts. We normalise all embeddings to unit length and store them in a FAISS index configured for inner-product similarity. At inference time we encode the user query, perform a nearest-neighbour search to retrieve the top-k relevant chunks (with \(k=3\) in our experiments), and append these chunks to the query as additional context. This explicit description of the embedding model and retrieval parameters makes our RAG setup reproducible.

We implement semantic document chunking to ensure that the retrieval module processes coherent units of text rather than arbitrary token spans. Given a long document D divided into paragraphs \(P_{1}, \dots , P_{n}\), we compute embeddings \(\psi (P_{i})\) for each paragraph using the same sentence transformer that we use for retrieval. We initialise a chunk with the first paragraph and iteratively append the next paragraph \(P_{i+1}\) when two conditions are met: (i) the combined token length stays below the model’s context window (1024 tokens in our experiments) and (ii) the cosine similarity between \(\psi (P_{i})\) and \(\psi (P_{i+1})\) exceeds a threshold \(\delta _{c}\). We set \(\delta _{c}=0.65\) (empirically tuned on the validation set).

When either condition fails, we start a new chunk with \(P_{i+1}\). We also add a small buffer of one sentence overlap between adjacent chunks to preserve context. This procedure groups semantically similar paragraphs together and produces chunks that respect both the model’s token limit and the topical structure of the source document.

We optimize retrieval further using a hierarchical U-Retrieval strategy. High-level clinical tags, such as tumor stage, disease type, or treatment categories, guide the initial retrieval, reducing the document pool to a manageable size. The system then iteratively integrates broader contextual summaries, balancing precision with global context awareness. This multi-layered retrieval enables comprehensive reasoning over complex oncology-specific scenarios.

Graph-based knowledge integration

To enhance factual reliability and interpretability, we integrate a domain-specific knowledge graph \(G\), constructed from standardized resources UMLS, SNOMED-CT, and ICD-10. This graph encodes entities as nodes and their relationships as edges:

where \(v_i\) and \(v_j\) represent medical entities (e.g., “adenocarcinoma” or “Osimertinib”), and \(e_{ij}\) represents relationships (e.g., “treated_with”).

Graph enrichment occurs through triple graph construction, linking retrieved entities to authoritative references and professional definitions:

For instance, a TNM stage extracted from text is mapped to corresponding UMLS nodes and linked to oncology treatment guidelines, ensuring outputs remain grounded in verified medical knowledge.

To encode the graph, we employ a two-step process:

-

1.

Node Encoding: Each node is represented as a dense vector embedding using a pretrained graph embedding model TransE46. These embeddings capture the semantic meaning of entities based on their attributes and the structure of the graph. For example, the embedding for “adenocarcinoma” encodes its connections to treatments, symptoms, and associated genes.

-

2.

Edge Encoding: Relationships (edges) between nodes are represented as directional vectors. These are computed by applying transformation functions to the embeddings of the connected nodes. For instance, the edge “treated_with” between a disease node and a medication node reflects the nature and direction of the relationship.

Hierarchical tagging further improves graph efficiency and interpretability. Each graph node is tagged with categories such as “Symptoms,” “Medications,” or “Patient History,” creating a multi-level abstraction. During inference, the model accesses relevant graph layers, ensuring fast and precise retrieval for tasks that require high-level summaries and fine-grained details.

The combined encoding of nodes and edges enables efficient traversal and reasoning over the graph. By embedding the graph in a high-dimensional space, the model can retrieve semantically similar nodes and relations, supporting robust and context-aware clinical predictions.

Model implementation and evaluation metrics

The instruction tuning, RAG, and graph-based reasoning components are integrated into lightweight LLaMA variants, creating a unified inference pipeline. Scalability is evaluated by varying the number of German instructions and the model size. Minimal German instructions (100–400 examples) are used to test cross-lingual adaptability, highlighting how small bilingual datasets influence performance. During training, we systematically vary the instructions to improve the model’s adaptability. Lightweight models are compared with larger variants to assess their performance in resource-constrained environments.

We evaluate the framework’s performance using metrics tailored to specific tasks. For entity recognition, relation extraction, and document classification, we report the F1 score. For imbalanced datasets like TCGA-C, we use the area under the precision-recall curve (AU-PRC) to emphasize performance in uneven class distributions. Binary tasks, such as TNM staging and treatment response prediction, are evaluated using the area under the curve (AUC).

Results

We evaluated our instruction-tuned LLMs across biomedical and oncology tasks, covering a spectrum of architectures and parameter counts, as shown in Tables 2 and 3. This included LLaMA, Qwen, and DeepSeek configurations, all integrated into our instruction-tuning, RAG, and graph-reasoning pipeline under the same experimental conditions. Each model variant progressed from a base configuration through instruction tuning, RAG integration, and finally Graph-RAG enhancement. We observed consistent performance boosts at every stage, especially on the oncology tasks. Larger models like LLaMA-3.1-8B achieved the highest accuracy, but smaller models such as Qwen3-1.7B remained competitive while requiring markedly fewer resources.

Instruction tuning substantially increased F1 scores on standard NER benchmarks (Table 2). For example, LLaMA-3.1-8B improved from 86.3 to 89.5 on NCBI-Disease after tuning, while LLaMA-3.2-3B rose from 82.8 to 86.0 on BC5CDR-Disease. In parallel, Qwen3-8B climbed from 86.0 to 89.1 on the same dataset, confirming that the gains generalize beyond the LLaMA family. On BC5CDR-Chem, contextual information reduced confusion about similar chemical mentions; for LLaMA-3.1-8B the +RAG stage lifted performance to 94.7, and Graph-RAG maintained 94.4.

Instruction tuning also helped relation extraction. The models learned to link diseases with treatments or genetic variants. LLaMA-3.2-3B reached 92.5 on i2b2-2010, while LLaMA-3.1-8B achieved 93.2; Qwen3-8B followed closely at 93.0. Using RAG and Graph-RAG, the models matched gene–disease pairs more precisely.

Natural-language inference tasks such as MedNLI tested logical reasoning. Instruction-tuned LLaMA-3.1-8B improved from 88.0 to 90.5, and LLaMA-3.2-3B advanced from 86.6 to 89.8.

On oncology-specific tasks (Table 3), the graph-based models excelled. In TNM staging, Graph-RAG enhanced entity linking by referencing established oncology guidelines, boosting F1 scores by up to 2.6. This structured reasoning allowed the models to generate consistent, verifiable outputs even in complex staging scenarios. LLaMA-3.1-8B now classifies biomedical literature into canonical cancer hallmarks with an F1 of 84.5, surpassing its previous 83.8. Linking TNM attributes to known ontologies supported correct category assignment and raised F1 scores on T, N, and M labels. Despite their compact size, DeepSeek-LLM-7B and Qwen3-1.7B each surpassed 80 macro-F1 once graph reasoning was added, underscoring the generality of the approach.

Cross-lingual tests further highlighted the value of bilingual instruction. With only a few hundred German demonstrations, LLaMA-3.1-8B improved from 78.4 to 83.3 on ICD-10 coding, and Graph-RAG pushed the score to 86.5. Comparable trends appeared for Qwen3-8B (80.1 \(\rightarrow\) 83.5 \(\rightarrow\) 85.3 ) and DeepSeek-LLM-7B (77.9 \(\rightarrow\) 81.2 \(\rightarrow\) 82.9 ). The multilingual tuning also benefited SNOMED classification and TNM staging in German. Figure 2 shows that gains peak with roughly 200 instructions, demonstrating that even small bilingual datasets enable substantial cross-lingual generalisation.

As seen in Figure 2, performance improves as the number of German instructions increases from 100 to 400, with gains plateauing around 200 examples for many tasks. Complex tasks still benefited from 400. LLaMA-3.1-8B, with its larger capacity, made better use of these extra instructions. Smaller models also gained but reached a plateau sooner. LLaMA-3.2-3B maintained a favourable balance between efficiency and accuracy, making it attractive for clinical environments with limited computational resources.

Discussion

Our findings show the promise of combining instruction tuning, retrieval augmentation, and graph-based knowledge integration for oncology NLP. The incorporation of a few instructions in another language demonstrated the potential of cross-lingual capabilities. By using minimal bilingual training data, our approach bypassed the usual costs associated with large-scale multilingual training, offering a practical and scalable solution for global healthcare systems with diverse linguistic needs. This tuning step aligned the models with domain-specific tasks and helped them recognise disease names, biomarkers, and chemical entities. Adding retrieval further refined results.

Retrieval augmentation added critical agility to the system, allowing the model to dynamically access up-to-date information at inference time instead of relying solely on static, parameter-encoded knowledge. This design enables models to adapt to evolving oncology guidelines and clinical practices, which often change multiple times a year. For example, retrieval mechanisms can help the model navigate newly introduced therapies or updated TNM staging criteria without requiring expensive retraining. The integration of retrieval from trusted clinical sources highlights its potential in dealing with incomplete or ambiguous clinical data.

Graph-based knowledge integration improved the model’s reasoning by structuring relationships between clinical entities. Rather than merely retrieving relevant concepts, the knowledge graph enabled the model to place these concepts into a structured context, improving logical reasoning and reducing errors due to ambiguous terms. This structured reasoning aligns closely with clinical workflows, where decisions depend on clear relationships between diagnoses, treatments, and outcomes. By linking predictions to specific nodes in the graph, the model can help with traceability and explainability, which are crucial for building clinician trust.

Model size played a role in performance. Larger models, like LLaMA-3.1-8B, excelled in extracting biomedical entities. However, smaller models such as LLaMA-3.2-3B and Qwen3-1.7B achieved comparable results on many tasks–particularly when supported by retrieval and graph integration. This trade-off between performance and computational cost is especially relevant for resource-constrained settings. DeepSeek-LLM-7B likewise illustrated that mid-sized checkpoints, when paired with our pipeline, can match or exceed larger baselines. Smaller models, paired with efficient retrieval and graph-based reasoning, offer a viable pathway for deploying advanced NLP tools in clinics with limited hardware capabilities.

Our experiments showed diminishing returns with high instruction counts. After approximately 200 German instructions, improvements plateaued for simpler tasks such as ICD-10 coding. Complex tasks, like TNM staging, showed marginal gains up to 400 instructions. This finding underscores the importance of tailoring instruction counts to task complexity and resource availability. Future exploration of instruction prioritisation or curriculum learning could optimise the cost-benefit balance, ensuring that effort is directed where it yields the most significant gains.

The cross-lingual modelling approach demonstrated real-world applicability. Bilingual instruction tuning, combined with retrieval and knowledge graphs, empowered the model to navigate clinical texts in another language–even with minimal supervision. Notably, Qwen3-8B and DeepSeek-LLM-7B both surpassed 85 macro-F1 on ICD-10 coding after Graph-RAG, confirming that cross-lingual gains are architecture-agnostic. This adaptability can address challenges faced by rural or underserved regions where linguistic diversity often limits access to advanced clinical technologies. Adding a modest number of domain-specific glossaries or synthetic training examples may further enhance performance on rare or compound medical terminology.

Qualitative analyses revealed model limitations. On NER tasks, confusion between biomarkers such as EGFR and HER2 highlighted the need for more robust contextual disambiguation. Graph-based reasoning mitigated these issues in part by linking terms to authoritative definitions, yet uncommon or rare entities continued to pose challenges. Similarly, for TNM staging extraction, the model excelled with standard terminology but struggled with vague or non-standard formulations. Retrieval partially addressed these gaps by surfacing canonical TNM definitions, while graph integration provided structured connections between terms and staging guidelines. However, cases where clinical texts themselves lacked clarity remained problematic, underscoring the dependence of NLP systems on the quality of source data.

Cross-lingual coding introduced unique challenges. While minimal German instructions helped the model perform ICD-10 coding and SNOMED classification tasks, the model occasionally failed with long compound German words or uncommon clinical expressions. Further refining multilingual embeddings and leveraging Qwen’s larger vocabulary coverage may alleviate these errors, especially when handling specialised oncology terminology.

A deeper look at the model’s performance on the MSK-IMPACT dataset revealed its ability to correctly match common mutations, such as EGFR, to appropriate therapies. However, the model struggled with rare genetic variants due to sparse retrieval references. In such cases, indirect reasoning and inference from related mutations proved insufficient. Future work could address this limitation by integrating curated genomic knowledge bases or using generative retrieval strategies to synthesise knowledge from related contexts.

Future directions could refine these methods further. Expanding multimodal capabilities by integrating text-based NLP with imaging data–such as radiology scans or histopathology images–could create a more comprehensive oncology assistant. Generative retrieval strategies and graph embedding techniques may raise the performance ceiling by improving the depth and scope of retrieved knowledge. Extending cross-lingual integration to low-resource languages could address global disparities in healthcare technology access. Testing the framework in clinical trials with real-world practitioners will provide critical insights into its usability, reliability, and impact on decision-making.

Data Availability

The Llama2-MedTuned-Instructions dataset used for instruction tuning is publicly available at: https://huggingface.co/datasets/nlpie/Llama2-MedTuned-Instructions. The TCGA Pathology Report dataset, used for document classification and TNM staging, can be accessed at: https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga. The MSK-IMPACT dataset, used for treatment response prediction, is available from cBioPortal: https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=msk_impact_2017. The aggregated data used for modeling in this study can be requested from the authors’ institution for non-commercial research and validation purposes, subject to a data transfer agreement and approval from the relevant ethical and data governance boards.

References

Pardoll, D. M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 252–264 (2012).

Topol, E. J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 25, 44–56 (2019).

Bedogni, G. Clinical prediction models–a practical approach to development, validation and updating (2009).

Alawad, M. et al. Automatic extraction of cancer registry reportable information from free-text pathology reports using multitask convolutional neural networks. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 27, 89–98 (2020).

Xing, R., Luo, J. & Song, T. Biorel: Towards large-scale biomedical relation extraction. BMC Bioinf. 21, 543 (2020).

Devlin, J. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 (2018).

Lee, J. et al. Biobert: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 36, 1234–1240 (2020).

Alsentzer, E. et al. Publicly available clinical bert embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.03323 (2019).

Gu, Y. et al. Domain-specific language model pretraining for biomedical natural language processing. ACM Trans. Comput. Healthc. (HEALTH) 3, 1–23 (2021).

Huang, X., Khetan, A., Cvitkovic, M. & Karnin, Z. Tabtransformer: Tabular data modeling using contextual embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.06678 (2020).

Rohanian, O., Nouriborji, M., Kouchaki, S. & Clifton, D. A. On the effectiveness of compact biomedical transformers. Bioinformatics 39, btad103 (2023).

Rohanian, O. et al. Lightweight transformers for clinical natural language processing. Nat. Lang. Eng. 30, 887–914 (2024).

Ruder, S. An overview of multi-task learning in deep neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.05098 (2017).

Brown, T. et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 1877–1901 (2020).

Touvron, H. et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 (2023).

Singhal, K. et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 620, 172–180 (2023).

Saab, K. et al. Capabilities of gemini models in medicine. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.18416 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. A study of biomedical relation extraction using GPT models. AMIA Summits on Translational Science Proceedings 2024, 391 (2024).

Wadhwa, S., Amir, S. & Wallace, B. C. Revisiting relation extraction in the era of large language models. In Proceedings of the conference. association for computational linguistics. meeting, vol. 2023, 15566 (2023).

Gutierrez, B. J. et al. Thinking about gpt-3 in-context learning for biomedical ie? think again. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.08410 (2022).

Yang, H., Li, J., Zhang, C., Sierra, A. P. & Shen, B. Large language model-driven knowledge graph construction in sepsis care using multicenter clinical databases: Development and usability study. J. Med. Internet Res. 27, e65537 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Relation extraction using large language models: a case study on acupuncture point locations. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 31, 2622–2631 (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Medical graph rag: Towards safe medical large language model via graph retrieval-augmented generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04187 (2024).

Hu, Y. et al. Grag: Graph retrieval-augmented generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.16506 (2024).

Alawad, M. et al. Integration of domain knowledge using medical knowledge graph deep learning for cancer phenotyping. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.01337 (2021).

Zhou, S., Wang, N., Wang, L., Liu, H. & Zhang, R. Cancerbert: a cancer domain-specific language model for extracting breast cancer phenotypes from electronic health records. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 29, 1208–1216 (2022).

Nishio, M. et al. Zero-shot classification of tnm staging for japanese radiology reports using chatgpt at the rr-tnm subtask of ntcir-17 mednlp-sc. Proceedings of the NTCIR-17 Conference . RR-TNM Subtask, MedNLP-SC Track. (2023).

Fujimoto, K. et al. Classification of cancer tnm stage from japanese radiology reports using an on-premise llm at the ntcir-17 mednlp-sc rr-tnm subtask. Proceedings of the NTCIR-17 Conference. RR-TNM Subtask, MedNLP-SC Track. (2023).

Kefeli, J., Berkowitz, J., Acitores Cortina, J. M., Tsang, K. K. & Tatonetti, N. P. Generalizable and automated classification of TNM stage from pathology reports with external validation. Nat. Commun. 15, 8916 (2024).

Moral-González, R., Gómez-Adorno, H. & Ramos-Flores, O. Comparative analysis of generative LLMS for labeling entities in clinical notes. Genomics & Informatics 23, 1–8 (2025).

Arzideh, K. et al. From bert to generative ai-comparing encoder-only vs. large language models in a cohort of lung cancer patients for named entity recognition in unstructured medical reports. Computers in Biology and Medicine195, 110665 (2025).

Ghosh, S. et al. A closer look at the limitations of instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.05119 (2024).

Sukeda, I., Suzuki, M., Sakaji, H. & Kodera, S. Jmedlora: medical domain adaptation on japanese large language models using instruction-tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.10083 (2023).

Xie, Q. et al. Medical foundation large language models for comprehensive text analysis and beyond. npj Digital Medicine 8, 141 (2025).

Doğan, R. I., Leaman, R. & Lu, Z. Ncbi disease corpus: a resource for disease name recognition and concept normalization. J. Biomed. Inform. 47, 1–10 (2014).

Li, J. et al. Biocreative v cdr task corpus: a resource for chemical disease relation extraction. Database2016 (2016).

Ando, R. K. Biocreative ii gene mention tagging system at ibm watson. In Proceedings of the second biocreative challenge evaluation workshop, 23, 101–103 (Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas (CNIO) Madrid, Spain) (2007).

Collier, N., Ohta, T., Tsuruoka, Y., Tateisi, Y. & Kim, J.-D. Introduction to the bio-entity recognition task at jnlpba. In Proceedings of the International Joint Workshop on Natural Language Processing in Biomedicine and its Applications (NLPBA/BioNLP), 73–78 (2004).

Uzuner, Ö., South, B. R., Shen, S. & DuVall, S. L. 2010 i2b2/va challenge on concepts, assertions, and relations in clinical text. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 18, 552–556 (2011).

Bravo Serrano, À., Piñero González, J., Queralt Rosinach, N., Rautschka, M. & Furlong, L. I. Extraction of relations between genes and diseases from text and large-scale data analysis: implications for translational research. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015 Feb 21; 16 (1): 55 (2015).

Romanov, A. & Shivade, C. Lessons from natural language inference in the clinical domain. arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.06752 (2018).

Baker, S. et al. Automatic semantic classification of scientific literature according to the hallmarks of cancer. Bioinformatics 32, 432–440 (2016).

Zehir, A. et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med. 23, 703–713 (2017).

Rohanian, O. et al. Exploring the effectiveness of instruction tuning in biomedical language processing. Artif. Intell. Med. 158, 103007 (2024).

Johnson, J., Douze, M. & Jégou, H. Billion-scale similarity search with GPUS. IEEE Trans. Big Data 7, 535–547 (2019).

Bordes, A., Usunier, N., Garcia-Duran, A., Weston, J. & Yakhnenko, O. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational data. Advances in neural information processing systems26 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception, design, and analysis of the work and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Andreas Wicki reports funding from the Precision Oncology Program, a public-private partnership between University of Zurich, University Hospital Zurich, and Hoffmann-La Roche. Support for attending meetings and/or travel: Andreas Wicki received support from Amgen and ESMO 2022. Leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, paid or unpaid: Andreas Wicki serves as a Board Member of the Swiss Society of Medical Oncology and as Chair of the Human Medicines Expert Committee at the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products (Swissmedic). Morteza Rohanian declares no competing interests. Tarun Mehra declares no competing interests. Nicola Miglino declares no competing interests. Farhad Nooralahzadeh declares no competing interests. Michael Krauthammer declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rohanian, M., Mehra, T., Miglino, N. et al. Towards scalable and cross-lingual specialist language models for oncology. Sci Rep 15, 35480 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19282-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19282-2