Abstract

Data drift caused due to network changes, new device additions, or model degradation alters the patterns learned by ML/DL models, resulting in poor classification performance. This creates the need for a generalized, drift-resilient model that can learn without retraining in dynamic environments. To maintain high accuracy, such a model must classify previously unseen IoT devices effectively. In this study, we propose a three-tier incremental architecture (CNN-PN-RF) combining Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for feature extraction, Prototypical Network (PN) for class embedding, and Random Forest (RF) for robust classification. The model utilizes six aggregated diverse IoT datasets.Two similarly structured datasets (Dataset 1 and Dataset 2) were created from it, differing in training-testing splits, with some device CSV files withheld to test on unseen classification. Phase 1 employs a stand-alone CNN-based model with L2 regularization, dropout, and early stopping, achieving 70.96% accuracy. Phase 2 integrates CNN with RF, using SMOTE for class balancing and PCA for dimensionality reduction, attaining 83.79% accuracy. Phase 3 introduces PN to finalize the CNN-PN-RF model, enhancing classification issue of feature clustering, intra-class separability, and small-class support. Final accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were 99.56%, 99.66%, 99.56%, and 99.59% for Dataset 1, and 99.80% for all metrics on Dataset 2. The model was compared with state-of-the-art approaches and validated on unseen IoT subsets of both datasets, showing better generalization capability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Internet of Things (IoT) adoption is expected to grow to 75 billion devices by 20251. The need for efficient unseen device classifications has become increasingly important for device management, network security, and performance optimization in smart environments2,3,4. The classification task becomes complicated by the need for interoperability and changing network configurations5,6,7. Moreover, the increasing diversity of IoT devices and their data heterogeneity, along with each IoT device having its own set of requirements and Quality of Service (QoS) parameters, further complicates the process of unseen IoT device classification. AI-driven approaches, in particular machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), are widely used to process large datasets and networks, and to identify unique device patterns within data for efficient IoT device classification8,9. Their ability to detect hidden patterns strengthens anomaly detection, mitigates network congestion, and improves oversight within IoT ecosystems10,11. However, traditional ML/DL models often suffer from poor generalization when confronted with unseen/unknown/new IoT devices or exposed to shifting network behaviors, network upgrades, or natural model-accuracy degradation12,13. Additionally, these models often use the same data for training and testing. Their architectural design fails to capture real-world variations, leading to performance degradation over time14,15. Frequent retraining and continuous updates of ML/DL models are necessary to handle data distribution shifts (commonly known as data drifts)16. Failure to address these data drift effects can result in security vulnerabilities, resource inefficiencies, device misbehavior, and higher computational costs, which can prevent their large-scale deployment. Hence, a well-generalized model should be resilient to the data drift effect and must recognize previously unseen devices by leveraging learned patterns without having to constantly retrain or update externally17.

Recent studies have explored various approaches to investigate generalization in several single ML/DL models to reduce their retraining burdens18,19,20. While these models can perform well in controlled scenarios, they remain ill-equipped to manage the continuous, large-scale data streams generated by diverse IoT environments. Likewise, most of the single ML models21,22, particularly those relying on manual feature engineering, hamper models scalability and adaptability in dynamic contexts. Eventually, single DL models have addressed a few limitations of ML models (getting control of the overlapping device category issue) by automatically extracting features from raw data, eliminating manual engineering, and providing better classification results23,24. Yet, they are still limited in IoT environments where complex nonlinear relationships exist in the data and also classification performance on small samples cannot be avoided. Furthermore, their practicality in real-world IoT deployments is hindered by the overfitting issue. They require large, diverse datasets for training along with robust hyperparameter optimization and significant computational resources25.

CNNs are capable of learning effectively and efficiently even on non-image tasks, such as network traffic classification in IoT environments. They can learn spatially and temporally correlated patterns of features26,27 fast and proficiently, especially when data is tabulated and presented as a statistical dataset.The statistical, temporal, and protocol-level features are structured directly into a matrix format for CNN input. This allows the convolutional filters to learn cross-feature interactions and local correlations that are not usually learned by dense networks. Thus, the CNNs can offer intra-class variability robustness, parameter efficiency due to weight sharing, and effective local pattern extraction28,29. CNN’s, when used as a feature extractor, can facilitate unseen device classification without the need for retraining. Additionally, CNNs are highly effective at extracting subtle features from input data, capturing key spatial and hierarchical patterns that are critical for accurate classification.

Prototypical networks, being a type of metric-based Few-shot learning, are utilized for classification techniques in various IoT scenarios30 that allow for significant generalization due to the similarity measure, such as the Euclidean distance, where distances are computed to prototypes of the classes31. Unlike the traditional models that require huge labeled datasets32, they can adapt to unknown instances. Likewise, previous authors33 utilized them in a classification-by-class approach. They reduce retraining costs in the classification of IoT devices to designing generic representations of classes that place unseen data in categories based on their similarity to prototypes, which is accurate, flexible and successful34.

Random Forest (RF), a machine learning technique that builds an ensemble of decision trees to improve classification performance.They reduce overfitting by employing bagging and random feature selection35,36. RF performs well, particularly for IoT device classification, where specific network traffic metrics are extracted and used to differentiate devices37. Prior works have shown that RF handles heterogeneous and high-dimensional IoT traffic data with excellent accuracy.

Hybrid models combining ML and DL have also been explored38,39,40, showing improved classification in complex datasets. However, they still face issues such as overlapping device categories, nonlinear dependencies, and small-category imbalance41,42,43. Their unseen evaluation is often unjustified, limiting their cross-domain generalization.

To address these gaps, this research proposes a generalized hybrid CNN–PN–RF model that integrates CNN for feature extraction, PN for few-shot generalization, and RF for robust classification. The model is explicitly designed to handle unseen IoT devices and evolving network environments with minimal computational cost, improved scalability, and strong adaptability.

Main objective and contribution

This research aims to enhance unseen IoT device classification through a generalized three-tier hybrid CNN–PN–RF model. The main contributions are:

-

1.

An aggregated dataset was prepared by merging six publicly available datasets to create a generalized and diverse dataset comprising 82 features.

-

2.

An incremental hybrid model was developed starting from a standalone CNN with (70.96% accuracy), then CNN–RF with (83.79% accuracy), and finally CNN–PN–RF with (99.56% and 99.80% accuracy on two aggregated datasets).

-

3.

The proposed model was validated on two datasets Dataset 1 and Dataset 2 with test and train subsets, enabling unseen classification without retraining.

-

4.

Comparative analysis showed that the proposed hybrid model outperforms state-of-the-art across multiple evaluation metrics.

Research questions

The following RQs guide this study:

-

RQ1: How to develop an effective three-tier incremental model from phase 1 to phase 2 and then to phase 3 for unseen IoT device classification?

-

RQ2: What are the additional tuning processes utilized at each phase, along with incremental evolution?

-

RQ3: Does PN between CNN and RF enhance classification performance and generalization in phase 3?

-

RQ4:How effective is this hybrid phase 3 CNN–RF-RF in comparison with phase 1 CNN and stage 2 CNN–PN?

-

RQ5: How does the proposed model compare with state-of-the-art methods on unseen device classification?

Research motivation and gap analysis

The motivation for this research originates from the limitations in the generalization capabilities of current machine learning (ML) as well as deep learning (DL) models for IoT device classification. They are unable to handle the concept of data drift and performance degradation caused by network changes, new device additions, or configuration updates12,13,44. These traditional single ML models tend to need frequent retraining. They are not scalable or adaptable, while as single DL models are capable of better feature extraction45. Yet, they fail to achieve perfect generalization, even when used in combined/hybrid models46.

To overcome these challenges, this study proposes a generalized hybrid model that combines convolutional neural networks (CNN) for powerful feature extraction, prototypical networks (PN) for few-shot generalization, and random forests (RF) for robust and efficient classification. This CNN–PN–RF integration eliminates the need for manual preprocessing, feature engineering, protocol dependence, and frequent retraining, all of which are common shortcomings in prior work (detailed in the next section: Related Works). This proposed model is explicitly designed to handle unseen devices and evolving network environments with minimal computational cost and no performance drop, unlike traditional models that suffer performance decay over time47. This model was trained on six combined diverse IoT datasets spanning a wide range of device categories and communication protocols and was evaluated separately. It showed strong cross-domain generalization. Additionally, high accuracy was achieved without any dataset-specific tuning. The model not only offers superior scalability and long-term stability but also achieves reliable performance in real-world and resource-constrained IoT deployments. By bridging ML and DL techniques in a unified hybrid model with strong architectural design, this approach addresses a pressing research gap and sets a new benchmark for generalizable unseen IoT device classification, achieving high adaptability, reduced operational overhead, and improved real-world applicability.

Organization of the paper

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related work, while Section 3 presents the proposed methodology. Section 4 describes the architectural design, and Section 5 discusses the incremental model development. Section 6 outlines the experimental tools and setup, followed by Section 7, which presents the results. Section 8 provides a comparison with state-of-the-art approaches, and Section 9 discusses the key findings. Finally, Section 10 concludes the paper and highlights future research directions.

Related works

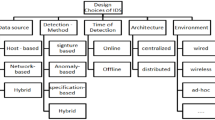

The unseen classification of IoT devices has gained much attention in recent years, and numerous studies have been conducted over a very diverse range of models, including machine learning (ML) models, deep learning (DL) models, and hybrid models. Despite demonstrating high performancein certain limited experimental settings, a large proportion of these studies have experienced unremitting challenges in dealing with unseen classification with robust generalization. The issue includes factors such as low scalability, use of handcrafted features, or lack of dynamic environments, responsiveness of static features, and inadequate generalization of previously unseen devices. These studies have been classified into two main subsections as follows:

A. Feature engineering-based models

Cvitic et al.48 developed an ensemble-based machine learning solution to IoT device classification with network traffic features in a smart home. They also applied logistic regression and other supervised learning methodologies. They trained their model on a proprietary dataset comprising of 41 devices. Through the application of 13 important characteristics of network traffic, the framework dynamically classified devices and exhibited a high level of accuracy of classification with 99.79%. In spite of its good performance, the method had some weaknesses when it comes to implementation in real-life settings because it was limited by the device diversity, fixed test settings, and the inability to scale to dynamic network settings.

Kostas et al.49 used standard ML models, along with multistage feature selection and genetic algorithms, to maximize the performance of classification. They recorded an accuracy of 83.30% and 94.30%on the Aalto and UNSW datasets, respectively. The model that they used worked fairly well but was dependent on expertly designed features and did not generalize to previously unseen device types, limiting its applicability and robustness in open-world deployment.

The technique of Aqil et al.47 proposed a temporally aware method of identifying IoT devices based on robust statistical features. Their model presented an average accuracy of 85 percent 85% on IoT Traffic Traces (2018) and 96 percent 96% on IoT-FCSIT (2022) datasets. However, the suggested method was ineffective when working with encrypted traffic or very dynamic traffic, and they did not present critical evaluation parameters (e.g., precision, F1-score, or recall), needed for comprehensive evaluation.

Xu et al.50 introduced a fine and lightweight architecture of ML in resource-constrained settings. They obtained 99.08%, 98.15%, and 95.28% percent precision on the CIC, UNSW, and SMPS datasets, respectively. The model focused on efficiency in its performance, yet it did not consider behavior variability and encryption in network traffic. The test was also limited to semi-controlled environments and, therefore was not suitable for realistic implementations.

Fan et al.51 proposed a semi-supervised learning strategy using convolutional neural networks to reduce reliance on labeled data. On the UNSW dataset, the proposed method achieved 99% accuracy. However, recall and F1-score were not reported as key performance indicators, and therefore it did not demonstrate robustness in open-set conditions.

Niu et al.52 developed a stacked ensemble learning model trained on the UNSW and TMA-2021 datasets, reporting high performance with an accuracy of over 98% on both datasets. Despite these promising metrics, the models showed high computational complexity, required frequent retraining to include new devices, and lacked scalability for large-scale IoT deployments.

B. Architecture-based models

Kotak et al.53 studied deep learning approaches for IoT device identification using a public dataset with 10 devices, achieving an accuracy of 99%. Although high accuracy was achieved, the evaluation was constrained to a small set of known devices and did not address performance across multiple communication protocols or diverse device categories, thereby limiting the model’s generalization capabilities.

Deng et al.54 proposed a hybrid model integrating Transformer-based tokenization with clustering for open-set device identification, achieving 99.89% and 99.68% accuracy on the UNSW and YourThings datasets, respectively. Their model demonstrated strong performance on encrypted traffic. However, it was not validated against previously unseen devices, leaving its real-world applicability uncertain.

Bao et al.41 introduced a hybrid deep learning model combining supervised and unsupervised learning with clustering and dimensionality reduction. While their results showed an average accuracy between 81.8% and 92.9%, other critical evaluation metrics were not reported. A key limitation was its reliance on easily spoofed features such as MAC addresses. Moreover, the model was data-integrity dependent and computationally intensive, making it unsuitable for real-time applications in resource-constrained environments. It also required frequent data updates to accommodate newly added devices.

Liu et al.55 proposed a 1D convolutional neural network using directional packet length sequences to reduce manual feature engineering and improve accuracy. Their model achieved promising results (99% across all metrics) while eliminating the need for handcrafted features. However, it relied solely on time-series-based features and did not consider payload, statistical, or header-based features. Additionally, the dataset used had an imbalanced distribution of data instances per device.

Yin et al.56 introduced GraphIoT, a lightweight identification model based on graph neural networks and incremental learning for IoT classification. With an F1-score of up to 96.37%, the model transformed traffic data into IoT Device Traffic Graph Representations (IoT-DTGRs), utilizing node, edge, and subgraph features for improved classification. The model adapts to new devices without retraining. However, it requires continuous hyperparameter tuning and involves complex graph construction, making it sensitive to changes in edge attributes and thus less practical for large-scale dynamic environments.

Table 1 provides a detailed summary of existing literature.In contrast, our proposed generalized three-tier hybrid CNN–PN–RF model offers full generalization and provides an end-to-end, protocol-agnostic solution for unseen IoT device classification. By integrating the deep feature extraction capabilities of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), the few-shot learning strengths of Prototypical Networks (PN), and the robust classification performance of Random Forest (RF), the model achieves strong class-wise identification and generalization. It has been validated on blind test data entirely excluded from training, demonstrating effectiveness in identifying previously unseen devices. Unlike conventional methods, this proposed approach does not require retraining, supports multi-protocol and multi-source data (spanning six diverse datasets), and operates effectively without extensive preprocessing or manual feature engineering.

Methodology

The detailed step-by-step methodology and corresponding subsections used to develop this generalized hybrid model are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Data collection

In this research, six widely used public datasets were utilized, which include:

-

1.

UNSW Dataset: https://iotanalytics.unsw.edu.au/iottraces.html

-

2.

ShIoT Dataset: ShIoT Dataset Link

-

3.

Ping-Pong Dataset: https://athinagroup.eng.uci.edu/projects/pingpong/data/

-

4.

IoT Sentinel Dataset: https://github.com/andypitcher/IoT_Sentinel

-

5.

IoT Finder Dataset: https://yourthings.info/data/

-

6.

Home Mole Dataset: https://github.com/DongShuaike/iot-traffic-dataset

We analyzed these six datasets one by one and found that they lacked data variety, especially in the type of information presented in their columns. For example, the UNSW dataset mostly uses MAC and IP addresses, many of which are repeated frequently. In numerous packets, the same addresses appear as both the source and the destination. MAC addresses (like "ec:1a:59:79:f4:89”, "ec:1a:59:83:28:11”) and IP addresses (like "192.168.1.223”, ”192.168.1.193”) show up repeatedly across multiple packets. This repetition limits the data’s diversity within individual packets/files and across IoT device files, making it difficult for the model to learn varying network behaviors. Similar issues were observed in the ShIoT, Ping-Pong, IoT Sentinel, IoT Finder, and Home Mole datasets, a common limitation in many IoT-related studies, i.e., the failure to capture the richness of device interactions.

To improve generalization, a multi-dataset approach was adopted by integrating multiple sources to create a more representative dataset while maintaining consistency in common device categories. We selected six IoT device categories with variations in manufacturer specifications, firmware versions, and configurations. The corresponding datasets include raw IoT traffic and PCAP packet traces. For example, although Amazon Echo devices are present in both the UNSW and ShIoT datasets, differences in firmware and hardware result in different MAC and IP addresses for each, adding to dataset diversity. Similarly, IoT Finder’s D-Link DSC-50009L camera shares functional similarities with IoT Sentinel’s D-Link DayCam, but they are not the same device. By using all six datasets, we created a more diverse, representative, and reliable depiction of IoT network behavior, helping minimize biases and improve generalization in our findings.

Data preparation

To develop a robust and generalizable CNN model for classifying unseen IoT devices, we transformed raw PCAP network traffic into structured data through effective feature extraction. This step was essential for capturing diverse behavioral patterns and avoiding overfitting to specific device signatures. We used CICFlowMeter , an open-source tool widely adopted for flow-based network analysis. It extracts 82 standardized statistical features from packet captures, including flow duration, packet/byte counts, ports, protocol types, and timestamps, and outputs the structured data in CSV format. These features provided a comprehensive representation of each network flow in every dataset and served as the foundation for our analysis. The complete list of features used in our experiments is presented in Table 2.

This study integrated six publicly available IoT datasets: SHIoT, IoT Sentinel, UNSW, IoT Finder, Ping-Pong, and HomeMole. Initially, these datasets consisted of multiple CSV files corresponding to various IoT devices but lacked a consistent labeling scheme. To unify them, CICFlowMeter was used to extract flow-level features, after which each device was manually categorized into one of six functional categories: Smart Speakers, Media Streaming Devices, Home Automation, Home Security Cameras, Smart Home Hubs/Controllers, and Home Appliances. Following standardization, the datasets were merged while maintaining consistent category labels across all sources. This balanced composition was crucial to ensure that the model learned generalized patterns across device types rather than overfitting to individual devices.

To critically evaluate generalization, we generated two similarly structured datasets (Dataset 1 and Dataset 2) based on the same six source datasets, with identical classes and devices. Theydiffered in their training-testing splits; in each, we randomly withheld some device CSV files for testing only, to assess unseen classification,, but the withheld files were different in the two datasets. This approach tested the model’s ability to identify category-level behavioral patterns instead of memorizing device signatures. The whole dataset collection and preparation details are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Preprocessing

The first step was to load and merge the data of several CSV files into one data frame. This was crucial in forming a single dataset that can be used for model analysis and training. Data files were maintained in an organized manner in separate folders, reflecting the various categories of devices and a well-structured approach to data management. Reading of each CSV file into a DataFrame was performed by using Pandas functions such as pd.read_csv(), after which they were concatenated to form a larger DataFrame. During this process, a column, the label column, indicating the category of each device, was kept, thus retaining the required data for supervised learning.

The load_data_from_folder() function reads the contents of each CSV file in a specific folder, iterates through each file, and labels it accordingly. In particular, it uses the library pandas to load each file as a DataFrame.

Considering an example, a file will be read when it is found in the directory by using \(D_i = \mathrm {pd.read\_csv}(\texttt {file\_path})\).

in which \(D_i\) is the DataFrame of the \(i^{\text {th}}\) file. This organized format allows loading the data efficiently so that further data manipulation and analysis would be more convenient.

On the second stage of data preprocessing, the file paths are used to extract the labels to categorize the files appropriately. As an example, files with the label ’smart_speaker’ are placed together. Once all the individual DataFrames are labeled, a final dataset of shape \((N, M + 1)\) where \(N\) is the total number of data entries and \(M\) is the number of features in each file will be obtained by using pd.concat(). To ensure the quality of data, empty files are skipped.

Rows with missing labels are removed using dropna(), ensuring data integrity and resulting in a dataset of shape \((N', M + 1)\), where \(N' \le N\).

In this research, missing values were handled using the SimpleImputer function with the strategy=’mean’ option. Any missing values are replaced by the mean of each numeric feature column using this function. Before this stage, non-numeric values were converted to numeric form and invalid entries such as NaN, inf, and -inf were standardized by replacing them with NaN. By ensuring that the imputation approach could be used consistently and accurately across the dataset, this maintained the data integrity for subsequent preprocessing and model training.

To improve model stability, features are standardized using StandardScaler(), ensuring a mean of 0 And a standard deviation of 1. This step helps normalize the data and enhances the performance of machine learning models.

Categorical features are processed by separating the features and labels. The feature matrix is created using \(X = \text {combined\_df.drop}(\text {'label'}, \text {axis}=1)\), with a size of \((N', M)\), while the label vector is extracted as \(y = \text {combined\_df['label']}\), with a size of \((N', 1)\). Labels are then converted into numerical values using LabelEncoder(), transforming categories into unique integers, where

and \(C\) represents the number of unique categories. For instance, if there are six classes, labels are assigned values from 0 to 5. Non-numeric features are converted into numeric values using LabelEncoder(), ensuring that all feature columns are in numerical format. Each non-numeric column is transformed separately, resulting in a fully numeric feature matrix represented as

Table 3 displays a conceptual change made to the dataset during the preparation stage. The word ”conceptual” is used because the table is a sample abstraction meant to demonstrate how significant preprocessing steps were implemented, rather than a verbatim duplicate of the raw dataset. A simplified example is given for clarification because the collection’s size (more than X million entries) makes it impractical to display every value.

The adjustments shown include imputation of missing data, normalization, and category encoding. This conceptual approach provides a clear illustration of how unprocessed IoT traffic elements were systematically transformed into modeling-suitable inputs.

This consolidated dataset is then structured and formatted to be compatible with machine learning models in the final preprocessing stage. \(X_{\text {encoded}}\) and \(y_{\text {encoded}}\) are transformed into numeric representations for training and classification purposes. Specifically, it \(X_{\text {encoded}}\) takes the form \((N', M)\), where \(N'\) is the number of samples and \(M\) is the number of extracted features. \(y_{\text {encoded}}\) is a label vector of shape \((N', 1)\), containing one encoded label per sample. This well-defined structure guarantees that the dataset is ready for input into standard machine learning pipelines.

Feature selection

IoT device classification is heavily influenced by feature selection, which shapes model accuracy and generalization57. In this phase, the dataset is refined to contain a well-defined yet complete set of features. For this study, all 82 original features were included, along with a labeling feature, resulting in a total of 83 columns per device file. All features are important, as each brings a different perspective to the data, capturing fine-grained patterns and relationships in IoT behavior. This comprehensive inclusion minimizes information loss and enables the model to learn from the full range of device characteristics. Additionally, exposure to diverse data patterns increases robustness, allowing the model to generalize well to unseen devices, which is crucial in the heterogeneous environment of IoT58. Moreover, by preserving all attributes, the model becomes resilient to changes in device behavior (e.g., data drift, new devices, and system upgrades), resulting in better predictive performance across heterogeneous datasets. Maintaining a wide feature set adds adaptability, ultimately improving classification accuracy and generalization, and making the classification more reliable in real-world IoT settings.

In this research, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was adopted for feature transformation rather than feature selection, allowing the retention of all 82 original features’ variance in a reduced-dimensionality space. Recent studies59,60 support the effectiveness of PCA over traditional feature selection methods in maintaining model accuracy, generalization, and robustness across both binary and multiclass classification tasks.

Architectural design

This section defines the overall structure and workflow of the proposed hybrid three-tier CNN–PN–RF architecture. The model begins by feeding input data into a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to perform deep feature extraction, capturing essential patterns and representations from the data. The extracted features are then passed to the second (middle) layer, Prototypical Networks (PN), where they are further refined by organizing around “prototypes,” which are representative feature vectors for each class that enhance class separation. Finally, these refined features are sent to the third layer, a Random Forest (RF) classifier, which uses an ensemble of decision trees to classify the data accurately. This three-layered structure combines the strengths of the CNN for deep feature extraction, the PN for structured class representation, and the RF for robust and accurate classification. For clarity, this proposed architectural design is illustrated in three key layers, as shown in Fig. 3.

Tier 1: Feature extraction with CNN (CNN layer 1)

In this first tier, the CNN functions as the initial gatekeeper of the proposed generalized three-tier hybrid CNN–PN–RF model.CNNs are highly effective at extracting subtle features from input data, capturing key spatial and hierarchical patterns that are critical for accurate classification. The CNN architecture includes several convolutional layers for feature extraction, max pooling layers to reduce dimensionality, and flattening layers before connecting to the dense layers. Regularization techniques and dropout are carefully applied to prevent overfitting, ensuring that the model generalizes well to unseen data.

Once training is complete, the CNN produces a set of rich feature vectors, high-level representations of the input data, which serve as the foundation for the subsequent stages of the classification framework. These feature vectors are then passed to the next stage of the prototypical network. Although CNN-based feature extraction reduces the semantic value of original features, but this trade-offis balanced by combining the CNN with the prototypical network (PN) in the next phases.

Tier 2: Prototypical network (Prototypical network layer 2)

Once the CNN completes feature extraction, the framework transitions seamlessly to the Prototypical Network61. In this tier, the concept of class prototypes is utilized by aggregating the feature representations generated by the CNN. Each prototype is computed as the mean feature vector of all instances belonging to a particular class, effectively serving as a representative point in the feature space. This approach facilitates efficient distance-based comparisons by enabling the model to assess how closely a new instance aligns with each class prototype. With Euclidean distance, the prototypical network measures similarity in an easily calculated and understandable way, which is essential to prototype-based classification. Once the prototypes are set, each test case is categorized by how close it is to the prototypes. The model provides the number of assignments by assigning the instance to the nearest class prototype, that is, tthe class with the shortest distance in feature space. This mechanism improves the model’s capability to determine the best possible class for each instance and serves as an important precursor of classification to classification by the Random Forest.

Tier 3: Random forest classifier (RF layer 3)

In the final tier, the Random Forest (RF) classifier receives the output of the Prototypical Network, specifically, the distance vectors representing the similarity between test instances and the class prototypes. These distance-based features, are rich and provide a concise description of the relationship of each instance to all classes. The Random Forest uses this information, to improve the robustness of classification and to avoid overfitting owing to its ensemble character and its ability to work with non-linear decision boundaries. In this three-tier architecture, all components have a specific and significant role to play. The CNN performs deep hierarchical extraction, the prototypical network allows easy and fast multi-class classification by utilizing distance measures in feature extraction, and the RF classifier uses the generalizing capabilities of the RF to stabilize the final predictions. This interconnected learning approach is very important, as it enhances the predictive ability of the model. Intensive testing validated the effectiveness of this proposed architecture. Prototypical network is integrated for better performance in unseen classification. The fully hybrid model delivered the accuracy of 99.56% on previously unseen devices, which is a notable improvement over the 70.96% accuracy obtained using the CNN alone and the 83.79% accuracy achieved by the CNN–RF hybrid. This optimal accuracy is mainly attributed to the prototypical network’s ability to produce class-representative prototypes, which enable fine-grained class separation even in adversarial, unbalanced data scenarios. These better results not only confirm the high classification accuracy of the proposed model but also its strong generalization capability across diverse IoT device datasets. The effectiveness of this three-level hybrid model manifests the utility of combining deep learning and traditional machine learning methods to develop a scalable and reliable model that can be used in real-world device classification.

Incremental model development

This section discusses the systematic, incremental approach we took to build and refine this architecture for a generalized, unseen IoT device classification. This research employs a three-phase methodology to attain optimal accuracy and generalization capability. Phases 1 and 2 focus on experiments with the CNN and integrating the CNN with the RF. Phase 3 introduces the PN to improve generalization, resulting in a hybrid CNN–PN–RF model designed for classifying unseen IoT devices. In the final phase, the proposed three-tier model is evaluated against existing approaches. Results shown that it achieves high classification accuracy, better generalization to new devices, and greater resilience to data drift. These final high-accuracy outcomes demonstrate that this hybrid model’s unseen classification has outperformed current approaches in managing the dynamic IoT environment, making it a reliable choice for real-world network management and security. Figure 4 presents the incremental model development phases

Phase 1–Experiments with CNN

In Phase 1, the CNN neural network model starts with a convolutional layer that has 96 filters And a kernel size of 3, using the ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activation function to add non-linearity. Additionally, this layer also applies an L2 regularization set at \(3.0645 \times 10^{-3}\) to reduce models’ overfitting by penalizing the large weights. After this, there is a max pool layer with a pool size of 4 to make the data more dimensionally reduced while retaining the crucial features.

This is then fed to a dense layer of 256 neurons, where ReLU activation function and L2 regularization are applied to keep the model simple. Further to avoid overfitting, a dropout layer at a 30% rate is used, such that 30% of the neurons are deactivated randomly in the training process.

Lastly, the model has a thick output layer with the number of neurons equal to the distinct classes in a target variable, having a softmax activation function. It yields a probability distribution over all classes, which sums to 1, and the most probable class is chosen as the model’s prediction; hence, it is applicable in multi-class classification. Even though the network is built using fully connected (dense) layers, it still handles sequential one-dimensional feature vectors like a 1D CNN. The model is built on Adam optimizer and the sparse categorical cross-entropy loss. To further combat overfitting, an early stopping callback is used during training to monitor the validation loss and terminate training when the loss no longer decreases.

Regularization and dropout

L2 regularization acts as a form of prevention against overfitting by penalizing large weights, which forces the model to learn simpler and more general patterns. It introduces a penalty term in the loss function, which is proportional to the square of the magnitude of the weights. Consequently, the model is not encouraged to rely on one feature, and thus, its capability to identify more features is increased for bettergeneralization on unseen data.

The neural network begins with a fully connected Dense layer consisting of 256 neurons. This layer employs the ReLU activation function and applies L2 regularization with a coefficient of 0.01 to mitigate overfitting by penalizing large weight values. To further enhance generalization, a Dropout layer with a rate of 0.3 is introduced, randomly deactivating 30% of neurons during training. The final layer is another fully connected Dense layer, where the number of neurons corresponds to the total number of unique output classes. This output layer uses the Softmax activation function to provide normalized class probabilities, enabling effective multi-class classification.

These configurations will make sure that big values of weight are penalized in the process of training, which will work to promote more generalized learning. Secondly, batch normalization is used to normalize the training by ensuring a similar distribution of activations in all the layers. The method can help to achieve faster convergence, and it can increase the performance of the model on unseen or novel IoT devices; thus, improving its generalization capacity.

Another type of regularization is dropout, which is employed to minimize the Likelihood of overfitting by discouraging the model from falling into the trap of overfitting. it is too dependent on particular neurons. We use a dropout rate of 0.3 so that 30 percent of the neurons are dropped in our implementation. Each iteration of training will randomly deactivate. This randomness compels the model to learn stronger and more generalized feature representations.

Early stopping

One of the most important strategies to prevent overfitting during training of our model is early stopping. It halts the training process when the model no longer improves on the validation data, ensuring that training does not continue unnecessarily, which would otherwise reduce generalization to unseen data. In this hybrid model development, this technique, is crucial as achieving robust performance on unseen IoT devices requires balancing training efficiency with high classification accuracy.

After each epoch, the validation loss is monitored, and training stops when no progress is observed after five epochs (patience=5). We achieved a final unseen classification accuracy of 70.96% with our CNN model. The steps of Phase 1 (CNN) are explained in Table 4.

Phase 2 – Merging CNN with random forest and hyperparameter tuning

The results of our previous phase (Phase 1–Experiments with CNN) were promising but failed to discover complex patterns in the dataset, along with poor generalization to new devices, leading to performance below acceptable standards for real-world IoT applications. The model proved to be unadaptable for better generalization, highlighting the weakness of the CNN architecture when handling unseen data. We therefore explored hybrid models (ML-DL) and found that combining CNN with Random Forest (RF) would improve performance effectively. CNN excels at feature extraction, while RF is well-suited for classification tasks. Hence, the proposed hybrid CNN-RF model aimed to leverage ID CNN’s ability to learn hierarchical features and RF’s strength in generalization, reducing the risk of overfitting.

To further improve performance, batch normalization was implemented along with the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) to address class imbalance. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was also used for dimensionality reduction. The use of SMOTE balanced the data by creating synthetic examples of underrepresented classes, whereas PCA assisted in transforming the features and removing noise, allowing ID CNN to put more focus on the most useful features. These methods collectively improved the overall accuracy and generalization ability of the CNN-RF model. The tuning details of Phase 2 are mentioned below:

Synthetic minority over-sampling technique (SMOTE)

In this study, the dataset exhibited class imbalance, with some classes containing many device files (.csv files), while others had few or none. Because of this skewed data, biased model performance was anticipated, wherein the majority classes were preferred and generalization became low.

To overcome this problem, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied likewise as in36,62. It deals with the issue of imbalance in classes by creating artificially generated minority classes and balancing out the classes. The method allows the model to learn better on the underrepresented classes and results in better predictive performance.

The SMOTE process can be mathematically represented as:

where \(X\) denotes the original feature matrix and \(y\) represents the corresponding label vector. After applying SMOTE, \(X_{\text {balanced}}\) and \(y_{\text {balanced}}\) denote the new, class-balanced feature set and labels, respectively.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is particularly advantageous in scenarios involving high-dimensional data. With many features (82 in our case), it becomes inefficient to analyze them all directly. PCA reduces the dataset to components that capture the most variance while addressing multicollinearity, a condition where original features are highly correlated. By removing redundancy, PCA simplifies the dataset, making it easier to interpret and improving model effectiveness in generalization. In this study, PCA was applied with the parameter n_components = 0.95, ensuring that 95% of the dataset’s total variance was retained while reducing dimensionality.

This is achieved by solving the eigenvalue problem of the covariance matrix:

Where \(W\) is the matrix of eigenvectors corresponding to the largest eigenvalues?

The goal was to transform 82 potentially correlated features into a smaller set of uncorrelated components while preserving as much variance as possible. Unlike feature selection methods, which discard features based on certain criteria, PCA converts the entire feature set into orthogonal principal components63,64. This ensures that the maximum amount of information is preserved, which in turn supports better model generalization and efficiency65,66,67. However, it comes with a trade-off that the transformed components may lose some interpretability and semantic meaning compared to the original features.

Additionally, the utilization of PCA over feature selection is another trade-off. To overcome this and support our PCA utilization, our PCA transformed Data Plot Fig. 5, shows noticeable improvement in class separation within the new feature space. Additionally, the PCA Cumulative Variance Plot Fig. 6 confirms that approximately the first 15 components captured nearly 90% of the variance, while extending to 20 components retained up to 95% overall.. This balance guaranteed minimal information loss and the least noise despite dimensionality reduction.

These results all provide credence to PCA’s value as a feature extraction method. Instead of relying on all of the original features, a smaller number of PCs, roughly 20, is sufficient to keep the majority of the underlying data. PCA not only fixes dimensionality problems but also boosts computing performance, reduces the risk of overfitting, and improves model generalization. Hence, PCA is more efficient than feature selection in this case for this dataset.

To support our PCA utilization over feature selection, previous research continues to recognize PCA as a robust method for dimensionality reduction, particularly when the focus is on maximizing classification accuracy rather than preserving the interpretability of individual features. Foundational reviews like68 remain influential for articulating PCA’s role in variance maximization and model generalization. Recent advancements reinforce this paradigm69 demonstrate that PCA and similar dimensionality reduction methods often maintain or even enhance classification accuracy in various scenarios. For complex, high-dimensional domains70 a more interpretable dimensionality reduction variant is introduced that still supports effective downstream prediction performance. This type of contemporary findings corroborate the choice of selecting the PCA71. These findings support our selection because predictive performance was the primary objective of this research.

Reshaping data for CNN

The final step in Phase 2 model development involved reshaping the data to match the input requirements of the 1D CNN. CNNs typically expect inputs in the form of three-dimensional arrays: (samples, features, channels). Therefore, the data was transformed accordingly to ensure compatibility for training and evaluation.

After processing, the data is reshaped into a 3D array where each sample is represented as a feature matrix with a single channel:

Where \(n\) is the number of samples and \(m\) is the number of features?

This reshaping allows the 1D CNN to effectively process the structured data.

While the CNN-RF hybrid model delivered strong results, the pursuit of further improvement continued. The aim was to develop a more robust and fully generalized model for unseen classification tasks. To bridge this gap, advanced techniques such as prototypical networks72 were explored. These are particularly effective in handling imbalanced datasets and multi-class classification problems.

Our CNN-RF model demonstrated a total unseen classification accuracy of 83.79%. The pseudo-code for Phase 3 (CNN–RF) is shown in Table 5.

Phase 3: Merging CNN, prototypical network, and random forest

In Phase 3, a prototypical network (PN) is inserted between the CNN and RF classifiers to improve classification accuracy. Prototypical networks are capable of learning with few examples, making them especially valuable in scenarios where only a limited number of labeled instances are available for each class.

We leverage this few-shot learning capability by integrating PN into the architecture. The PN computes a prototype (or centroid) for each class using a support set of labeled examples. These prototypes represent the mean vector of the embeddings for each class in the learned embedding space.

The CNN is defined as a function:

Which maps the input vector space \(\mathbb {R}^{n_v}\) to an \(n_p\)-dimensional embedding space. In this space, intra-class samples are clustered closely together, while inter-class samples are well separated.

This embedding representation notably enhances the RF classifier’s ability to distinguish between classes, particularly in imbalanced and unseen data scenarios, thereby improving overall model generalization and accuracy.

For each class c, the prototype \(p_c\) is computed by averaging the 1D CNN embeddings of the support examples \(S^c_e\) from that class:

where \(|S^c_e|\) is the number of support examples in class c.

Given a query sample \(q_t\), we compute a distance d between its embedding and each class prototype to classify the query. We compute the probability that the query belongs to class c through the softmax function over the negative distances:

The model is trained by minimizing the classification loss using stochastic gradient descent (SGD). After training, new query samples can be classified by identifying the nearest class prototype. Various ”processes” of the prototypical networks are discussed below :

Prototype calculation

The prototypical_network()function computes a prototype for each class using CNN-extracted features.

-

Mean Feature Calculation: It calculates the mean feature for each unique class label in the training dataset. The prototype is stored as this average vector, which is the central tendency of the class in the feature space. In this way, we obtain a resulting array of prototypes with shape \((\texttt {num\_classes},\ \texttt {feature\_dim})\), where num_classes is the number of distinctive class labels and feature_dim is the dimensionality of the 1D CNN output.

Classification with prototypes

The classify_prototypes()function applies a distance-based classification method through:

-

Euclidean Distance Calculation: For each test sample, Euclidean distances to all class prototypes are computed using the cdist function from scipy.spatial.distance.

-

Assignment: Each test sample is assigned to the class of the closest prototype, implementing a non-parametric method that captures data variations missed by traditional classifiers.

Distance features for RF

The distances computed from the prototypical network are used as features to train our random forest classifier:

-

Robustness to Overfitting: Random Forest is an ensemble method that is resistant to overfitting and is particularly useful in high-dimensional and imbalanced classification problems.

-

Performance: By using prototype distances as features, the random forest benefits from a refined representation that simplifies decision boundaries and improves generalization.

Overall, the advantages of using a prototypical network in this architectural design include adaptability to unseen classes, the addition of few-shot learning capabilities, minimal reliance on large labeled datasets, and high computational efficiency. This makes it particularly effective for IoT and cybersecurity domains, where real-time, robust, and scalable classification is essential73. The pseudo-code for Phase 3 (CNN–PN–RF) is shown in Table 6.

Training RF classifier

The random forest classifier is trained using distance-based features derived from the prototypical network.

-

Training Phase: The features describing Euclidean distances from each test sample to the class prototypes are used to train the classifier. We employ 100 estimators (decision trees) to balance computational cost and model performance.

-

Evaluation: After training, the classifier predicts the class labels of test samples based on the learned distance features. This enables robust multi-class classification by interpreting proximity to prototype representations.

Incorporating the prototypical network into the Phase 2 architecture transformed the model from a 2-tier to a 3-tier structure (CNN \(\rightarrow\) Prototypical Network \(\rightarrow\) RF). Our final CNN-PN-RF model demonstrated a total classification accuracy of 99.56%. The improvement is primarily attributed to the prototypical network’s ability to generalize effectively in scenarios with imbalanced or limited data. By summarizing class features into representative prototypes, the model exhibits increased adaptability, particularly for unseen device classification tasks in dynamic environments.

Experimental tools and setup

Initial experiments were conducted on a personal computer with an Intel Core i5-10210U CPU (1.60 GHz, boost up to 2.11 GHz), 8 GB RAM, and a 500GB hard drive, running on Windows 11 Home. Machine learning implementations were carried out using Python (Anaconda).

As computational demands increased, we transitioned to cloud-based resources using a Microsoft Azure (student free) account to efficiently process the data. Subsequently, we upgraded to Google Colab Pro to access more computational power And GPU support, necessary for training our large And hybrid machine learning model. The final phase of experiments was executed on a high-performance system equipped with An NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1060 (6 GB), optimized with CUDA for GPU acceleration.

Model’s unseen evaluation and metrics

The training set structure was followed by the test sub-dataset, which consisted entirely of unseen CSV files that had not been used during training. This separate test sub-dataset was used to determine the final accuracy validation. It ensures a fair estimate of the model’s generalization capability.

During training, we used a validation split of 20%, meaning that 80% of the data was used for training, while the remaining 20% was reserved for validation. The test sub-dataset was loaded from a separate folder (test_data_path) and was never used in the training or validation phases. Model performance was monitored after each epoch, and overfitting was mitigated by applying early stopping.

The accuracy and generalization ability of the proposed model were evaluated using Dataset 1 and Dataset 2.

Evaluation metrics

The proposed model is evaluated in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score74,75. A comparison of actual versus predicted values, which reflects the model’s performance, is carried out using a confusion matrix. It includes four key components: true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN). Precision measures the percentage of predicted positive cases that are truly positive. The F1-score, which is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, ensures the model does not favor accuracy at the expense of precision.

The classifier’s performance at various threshold levels is visualized using a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, which plots the true positive rate (TPR) against the false positive rate (FPR). The area under the curve (AUC) serves as a single-value summary of classification effectiveness, with a higher AUC indicating better model performance.

Results

The results of this research provide a deeper analysis at the instance level, rather than just at the device level. Each row of data from the .csv files for each IoT device is classified individually. This method offers more detailed and granular insights for analysis.

Dataset 1 was used in most experiments throughout this research. However, Dataset 2 was also employed in Phase 3 to further validate the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed hybrid model.

Phase 1 Results–experiments with CNN (Dataset 1)

In this initial phase, a CNN achieved an accuracy of 70.96% while incorporating L2 regularization, batch normalization, dropout, and early stopping. This indicates the model’s ability to learn complex patterns while mitigating overfitting. L2 regularization penalized large weights, and batch normalization helped stabilize learning and accelerate convergence. Dropout increased robustness by preventing over-reliance on specific neurons, and early stopping ensured optimal performance by halting training at the right time.

Despite these enhancements, the CNN did not outperform expectations. It struggled to differentiate features across classes, especially with unseen IoT data, reducing its flexibility. This outcome underscores the need for hybrid models to enhance generalization, particularly for security-sensitive applications.

PHASE 1: Confusion matrix (Dataset 1)

Figure 7a highlights classification strengths and weaknesses. The highest number of correct predictions (297,024) occurred for Security Cameras. However, notable misclassifications were observed: 22,216 Home Appliances were wrongly identified as Security Cameras, and 29,577 Security Cameras were misclassified as Smart Speakers, likely due to overlapping features.

Home Appliances, though correctly classified 4,811 times, were misclassified as Security Cameras (1,179) and Smart Speakers (767). Streaming Devices had 1,618 correct classifications but were confused with Security Cameras 184 times. Minor categories Like Hubs and Controllers showed weak performance with only 9 correct predictions.

The CNN struggled with classes that share functional features (e.g., Security Cameras, Smart Speakers, and Home Appliances), leading to misclassifications due to non-linear relationships (e.g., voice control, network connectivity). High error rates in smaller categories indicated weak decision boundaries and model bias toward dominant classes. Overfitting to Security Cameras further limited adaptability.

PHASE 1: ROC for classes (Dataset 1)

The multi-class ROC curve in Fig. 8 illustrates model performance across classes. Home Appliances achieved the highest AUC of 0.98,that is, 98%, suggesting near-perfect classification. Smart Home Hubs and Controllers also performed well (AUC = 0.87,, that is, 87%). Security Cameras and Smart Speakers achieved moderate AUC values (0.68, that is, 68%),, while Media Streaming Devices followed at 0.63 (that is, 63%). The Home Automation class had the weakest performance, with An AUC of 0.58 (that is, 58%), , near random guessing. Overall, the model demonstrated wide variability in classification capability across different categories.

PHASE 1: Performance metrics evaluation (Dataset 1)

Table 7 summarizes key performance metrics. The model achieved a precision score of 0.8238, indicating that 82.38% of positive predictions were correct. This was affected by class confusion; for instance, Home Appliances were often misclassified as Security Cameras. The recall score of 70% reflects the model’s ability to detect true instances, though affected by frequent misclassifications like Security Cameras as Smart Speakers or Streaming Devices.

The F1-score, balancing precision and recall, was 75%, showing a moderate overall performance. The final model accuracy was also 0.7096, meaning the model correctly classified 70.96% of instances, supported by strong performance in dominant classes like Security Cameras and Smart Speakers. However, lower performance in smaller categories, such as Home Automation, reduced the overall accuracy.

Phase 2 Results–merging CNN with random forest and hyperparameter tuning (Dataset 1)

To overcome the limitations observed in Phase 1, a hybrid CNN–Random Forest (CNN–RF) model was developed. This approach integrates the feature extraction capabilities of 1D CNNs with the classification strengths of random forests to enhance generalization and reduce misclassification, particularly among overlapping categories. Preprocessing techniques such as batch normalization and SMOTE were incorporated to stabilize training and address class imbalance. SMOTE synthesized samples from minority classes, while batch normalization accelerated convergence. Combined with optimal hyperparameters, this strategy achieved an accuracy of 83.79%, reflecting an improvement of over 13% from Phase 1. In addition to improved accuracy, the model also demonstrated enhanced interpretability and stability, making it suitable for real-world IoT security applications.

PHASE 2: Confusion matrix (Dataset 1)

As shown in Fig. 9, the model classified 375,139 Security Camera instances correctly, showing its strength in identifying dominant categories. However, misclassifications persisted, including 24,662 Security Cameras incorrectly labeled as Smart Speakers and 1,004 Home Appliances misclassified as Security Cameras, suggesting overlapping features remain a challenge.

Smart Speakers achieved 45,423 correct predictions but were commonly confused with Security Cameras, reflecting feature overlap in audio and connectivity traits. Streaming Devices showed improved performance with 1,841 correct predictions and only 155 misclassified as Smart Speakers. Hubs and Controllers (23 correct) and Home Automation devices (125 correct) still underperformed due to limited data representation.

The 1D CNN component contributed to robust feature extraction, while the RF classifier provided decision-level robustness. Nonetheless, the model continued to exhibit overfitting towards dominant classes, such as Security Cameras. While classification improved over Phase 1, further refinement is needed for underrepresented and overlapping classes. Fine-tuning the Random Forest or using architectural enhancements could mitigate misclassifications where functional similarities exist, such as between Home Appliances and Smart Speakers.

PHASE 2: ROC for classes (Dataset 1)

The multi-class ROC curve shown in Fig. 10 evaluates the model’s discriminatory power across categories. Home Appliances (Class 0) exhibited the weakest performance with An AUC of 0.11 (11%), indicating very poor separability. Home Automation (Class 1) and Media Streaming Devices (Class 3) had AUCs of 0.50 (50%), equivalent to random guessing. Home Security Cameras (Class 2) followed with An AUC of 0.47(47%). Smart Home Hubs and Controllers (Class 4) slightly outperformed random with An AUC of 0.51 (51%). Smart Speakers (Class 5) showed the best AUC of 0.58 (58%), but still reflected weak predictive performance. In general, the model’s ROC values show limited capability to confidently distinguish between categories, particularly those with shared attributes.

Note: Class 0 = Home Appliances, Class 1 = Home Automation, Class 2 = Security Cameras, Class 3 = Media Streaming Devices, Class 4 = Smart Home Hubs and Controllers, and Class 5 = Smart Speakers. These classes reflect the diversity and overlapping functionalities in smart home environments.

PHASE 2: Performance metrics evaluation (Dataset 1)

Table 8 summarizes the evaluation metrics. The model achieved a precision of 0.8123, indicating that 81.23% of positive predictions were correct. A recall of 0.8379 reveals that the model successfully identified 83.79% of the actual relevant instances. The F1-score of 0.8229 (82%) demonstrates a strong balance between precision And recall. Finally, the overall accuracy also stands at 83.79%, signifying a robust performance. While false positives And class confusion persist, especially in overlapping categories, the results demonstrate clear improvements in both predictive reliability and class generalization compared to Phase 1.

PHASE 3 Results–merging CNN, prototypical networks and random forest (Dataset 1) and (Dataset 2)

The main objective of this research is addressed in this phase, which ultimately results in the development of a generalized, final hybrid CNN-based model and the implementation of optimizations, such as prototypical networks, to improve the accuracy of unseen device classification. Prototypical networks cluster features into contextual groups, effectively capturing non-linear dependencies and minimizing the misclassification of overlapping categories. Incorporating a prototypical network between the CNN and RF models has led to a significant accuracy boost in this strategic hybrid architecture.

For Dataset 1, accuracy improved by 15.77% from 83.79% to 99.56% (Phase 2 to Phase 3). Additionally, the model also achieved an exceptional accuracy of 99.80% for Dataset 2. These results emphasize the ability of this optimized model configuration to perform effectively across multiple datasets.

Results of dataset 1

PHASE 3: Confusion matrix (Dataset 1)

The confusion matrix (Fig. 11) highlights the model’s strong classification accuracy, particularly for Security Cameras, with 400,940 correct classifications. However, 1,000 Home Appliances and 31 Smart Speakers were misclassified as Security Cameras, indicating minor feature overlap. Home Appliances achieved 6,740 correct classifications, with only 17 misclassified as Security Cameras, demonstrating high precision. Home Automation recorded 127 correct classifications, though 7 instances were misclassified as Security Cameras, suggesting a need for refinement. Streaming Devices performed well, with 1,994 correct classifications and only 5 misclassified as Security Cameras. Smart Speakers had 59,066 correct classifications, although 1,001 Home Appliances were misclassified as Smart Speakers, hinting at shared feature characteristics. Hubs and Controllers had only 25 correct classifications, reflecting challenges in identifying underrepresented categories.

In this phase, the hybrid model was enhanced by incorporating a CNN-Prototypical Layer (PN)–Random Forest (RF) architecture for generalized IoT device classification. This addressed the Limitations of Phase 2 (CNN–RF model) and Phase 1 (CNN-only model). The prototypical layer improved generalization by refining intra-class feature similarities, thereby aiding RF in more accurately classifying unseen devices.

A significant reduction in misclassification was observed, especially for dominant categories. Security Cameras showed 400,940 correct classifications, with only 1,000 misclassified as Home Appliances and 31 as Smart Speakers, reflecting improved RF feature consistency. Overlapping device categories, such as Smart Speakers, also benefited, hence achieving 59,066 correct classifications, with just 1,001 misclassified as Home Appliances, therefore demonstrating the prototypical layer’s ability to distinguish devices with similar functionalities (e.g., audio and connectivity features).

Improvements were also evident in minority and underrepresented classes. Hubs and Controllers were correctly classified 127 times, while Home Automation achieved 25 correct classifications, showing enhanced RF sensitivity to small classes. Precision was high, with rare misclassifications minimized. For instance, Streaming Devices achieved 1,994 correct classifications with only 5 errors, indicating better-defined decision boundaries.

The model’s ability to manage complex, non-linear dependencies was strengthened, particularly for Home Automation and Streaming Devices.By enabling RF to extract deeper, more discriminative features without overfitting. Efficient generalization to unseen devices was achieved through the formation of representative class anchors, which reduced reliance on dominant class features and improved overall classification accuracy.

The model balanced accuracy across all classes by minimizing overfitting to frequent categories, avoiding bias toward dominant devices such as Security Cameras and Home Appliances. Lastly, the scalability of the Prototypical Layer in multi-class IoT classification was evident in the model’s consistent performance across categories, ensuring adaptability to evolving device types while reducing classification complexity.

PHASE 3: Training and validation accuracy along with loss (Dataset 1)

The training and validation accuracy curves, as shown in Fig. 12, and the corresponding loss curves in Fig. 13, highlight the improved performance of the final-phase model. With the integration of Prototypical Networks, the model demonstrates consistent and stable improvement in both training and testing accuracy. Additionally, the clear reduction in loss values signifies effective model optimization and enhanced generalization to unseen data, indicating successful learning and minimal overfitting.

PHASE 3: ROC for classes (Dataset 1)

The ROC curve depicted in Fig. 14 illustrates the final model’s exceptional performance across all six smart home device categories. Each class, like Home Appliances (Class 0), Home Automation (Class 1), Home Security Cameras (Class 2), Media Streaming Devices (Class 3), Smart Home Hubs and Controllers (Class 4), and Smart Speakers (Class 5) achieved a perfect Area Under the Curve (AUC) score of 1.00 (100%). This shows that the model is capable of making perfect distinctions between positive and negative instances of each category. The ROC curves always touch the upper left corner of the graph, which is an ideal classification ability with zero false positives or negatives, which proves the model has good generalization to new/unseen data.

PHASE 3: Performance metrics evaluation (Dataset 1)

Table 9 contains a summary of performance indicators of the final model. The score of the precision 0.9966 shows that 99.66 percent of all positive predictions were correct and this shows that the model is very reliable with the lowest number of misses. The recall value of 0.9956 indicates that the model was able to identify 99.56 percent of actual positive cases and this reveals that it successfully picked up relevant classes. The small discrepancy between the precision and recall implies there are minimal false negatives..

Furthermore, the F1-score of 0.9959 (99%)demonstrates a near-perfect balance between precision and recall, confirming the model’s robustness in handling both correctness and completeness of predictions. Lastly, the overall accuracy of 0.9956 indicates that 99.56% of all predictions across both positive and negative classes were accurate. This performance showcases the model’s excellent classification capability with only a very small proportion of misclassifications.

Results of dataset 2

Phase 3: Confusion matrix (Dataset 2)

The confusion matrix (Fig. 15) illustrates the model’s strong classification performance across device categories. Streaming Devices achieved 1,368,530 correct classifications, with minimal confusion, only 16 instances misclassified as Smart Speakers and 47 as Hubs and Controllers. Security Cameras also performed well, with 8,323 correct classifications; however, 1,000 instances were misclassified as Streaming Devices, likely due to shared video-related functionalities.

Hubs and Controllers showed robust accuracy, with 8,407 correct classifications and very few misclassifications i.e 4 into Streaming Devices and 2 into Smart Speakers. Smart Speakers recorded 128,851 correct classifications, though 6 were misclassified as Security Cameras and 3,169 as Streaming Devices, suggesting partial feature overlap. Meanwhile, Home Automation devices (578,317 correct) exhibited minimal confusion, with only 13 misclassifications into Streaming Devices.

Although major categories exhibit high accuracy, further refining feature extraction could enhance differentiation, particularly between Security Cameras, Streaming Devices, and Smart Speakers, which share overlapping functional traits.

Phase 3: Performance metrics evaluation (Dataset 2)

Table 10 reports the evaluation metrics of the final model on Dataset 2. The precision score of 0.9980 signifies that 99.80% of all positive predictions were accurate, indicating extremely low false positives. Similarly, the recall of 0.9980 shows that 99.80% of actual positive instances were successfully identified, implying negligible false negatives.

The F1 score of 0.9980 (99%) confirms a near-perfect balance between precision and recall, reinforcing the model’s ability to correctly and comprehensively identify each class. The overall accuracy of 0.9980 means that 99.80% of all predictions, whether positive or negative, were correct. These consistently high performance values demonstrate the model’s exceptional reliability and robustness in real-world multi-class IoT classification scenarios.

Phase-wise result interpretation in regard with OFSI, NLRI, and UI

The Phase-wise result interpretation regarding OFSI, NLRI, and UI from phase 1 (CNN) to phase 2 (CNN-RF) And then phase 3 (CNN-PN-RF) is presented in Fig. 16.The classification performance across Phases 1, 2, and 3 reveals a progressive evolution of this model’s ability to distinguish between complex and overlapping IoT device categories. These phases demonstrate how iterative refinements and architectural adjustments impact the model’s learning capability, generalization, and robustness. Three primary challenges were identified and tracked across these three phases:

The challenges associated with feature learning in classification tasks can be mapped to three key issues. Firstly, the Overlapping Feature Set Issue (OFSI) is closely tied to intra-class separability. When intra-class separability is poor, the feature distributions of different classes overlap notably, making it difficult for the model to distinguish between them effectively. Secondly, the Non-Linear Relationship Issue (NLRI) relates to feature clustering, where non-linear dependencies within the data disrupt simple clustering patterns. This requires the use of more complex models to accurately capture the underlying data structure. Lastly, the Underperformance in Smaller Categories (UI) issue corresponds to the need for small-class support. Smaller classes often suffer due to data imbalance, which can lead to disproportionately poor performance unless they are given specific attention during training.

Phase 1 interpretation

In the first phase, a standalone CNN model was employed to capture complex patterns and resolve overlapping feature similarities. However, the results indicate that the model faced significant limitations, particularly with Overlapping Feature Similarity Issues (OFSI). Notably, Smart Speakers were heavily misclassified as Security Cameras (27,138 instances), and conversely, Security Cameras were frequently predicted as Smart Speakers (72,342 instances). A similar trend was observed between Home Appliances and Security Cameras. These high bidirectional misclassification rates suggest that the CNN struggled to distinguish between these categories due to highly similar traffic characteristics such as continuous data flows, similar packet sizes, and temporal patterns typically observed in streaming or voice-based devices.

While CNNs are generally strong in handling overlapping classes in image or sequence data, in this case, the lack of spatial or temporal structure in the tabular network traffic features diminished the CNN’s ability to learn distinctive representations. Unlike image pixels or time-series segments, these features did not provide meaningful local dependencies for convolutional filters to extract. As a result, the CNN learned general but non-discriminative patterns, leading to blurred class boundaries in the latent space.

The model also exhibited signs of Non-Linear Relationship Inefficiency (NLRI). For example, Security Cameras were incorrectly predicted as Home Appliances (2,216), Home Automation (180), and Streaming Devices (601), indicating that the CNN’s current depth and non-linearity were inadequate to disentangle such complex overlaps in feature space. The latent representations lacked sufficient expressive power to form well-separated decision boundaries.

Additionally, Underrepresented Class Instability (UI) was evident in minority categories such as Home Automation and Hubs and Controllers, with only 0 and 12 correct predictions, respectively. Most samples from these underrepresented classes were redirected to dominant categories, a behavior indicative of class imbalance and sparse data learning. The CNN’s softmax output layer likely favored the majority classes when handling uncertain or ambiguous feature patterns from these low-frequency groups.

These limitations in Phase 1 highlight the need for architectural enhancements and advanced learning mechanisms to improve class separation, nonlinear feature mapping, and sensitivity to underrepresented categories.

Phase 2 interpretation

In Phase 2, a Random Forest (RF) classifier was integrated with 1D CNN outputs to leverage RF’s strength in handling non-linear class boundaries. This hybrid model demonstrated noticeable improvements over Phase 1, particularly in mitigating Overlapping Feature Similarity Issues (OFSI). The bidirectional confusion between Smart Speakers And Security Cameras improved notably. Misclassifications of Smart Speakers as Security Cameras increased from 27,138 to 45,423, while the reverse happened in the case of Security Cameras, which were misclassified as Smart Speakers, decreasing from 72,342 to 24,662. This reduction of nearly 40% in one direction illustrates RF’s effectiveness in refining decision boundaries that 1D CNNs alone could not adequately distinguish in high-dimensional feature spaces. The enhancement likely stems from RF’s ability to generate non-linear decision paths and capture complex feature interactions beyond what 1D CNN convolutional layers can isolate.