Abstract

Objective Dental anxiety is a significant barrier for patients seeking oral healthcare and can be influenced by biological, psychological, and demographic factors. This study aimed to investigate how different phases of the menstrual cycle affect dental anxiety in women immediately before undergoing root canal treatment, using both psychometric scales and physiological indicators. Gender-based comparisons were also included for contextual understanding. Methods An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted with 259 participants (aged 18–50 years, 191 women) requiring root canal treatment. Women were categorized into menstrual, proliferative, and secretory phases based on self-reported cycle data. The Severity of anxiety were assessed using the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), alongside physiological measures such as blood pressure and oxygen saturation. In addition to Kruskal-Wallis and Chi-squared tests, multiple linear regression analyses were performed to adjust for potential confounders, including age, education, preoperative pain, and physiological parameters. Results Women in the menstrual and secretory phases reported significantly higher MDAS and STAI-T scores compared to men (p < 0.001). Regarding the STAI-S, scores in all three menstrual phases were significantly higher than those of men (p = 0.001). Multiple regression analysis confirmed that these associations remained significant after adjustment for potential confounders, while age, education, preoperative pain, and physiological parameters showed no significant effects. Physiological parameters, including blood pressure and oxygen saturation, showed no significant variations across groups (p > 0.05). A strong positive correlation was observed between MDAS and both STAI-S and STAI-T scores. Conclusion Women in the menstrual and secretory phases reported higher levels of dental anxiety compared to men, but no significant differences were observed in physiological markers. These findings suggest that estrogen reduction during certain phases of the menstrual cycle may increase anxiety and highlight the potential clinical value of individualized anxiety management during these phases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anxiety is a psychological state characterized by feelings of worry and unease that arise in the presence of perceived threats, whether real or imagined, and is often associated with the anticipation of a potential future danger1. Dental anxiety, a specific form of anxiety, affects individuals undergoing dental procedures, often resulting in delayed or avoided treatment, which exacerbates oral health problems and reduces quality of life. This possess the potential for creating a vicious cycle between dental problems and treatment avoidance2,3,4. Despite significant advancements in dental technologies and treatment approaches, fear and anxiety remain prevalent in many patients, ranking dental anxiety among the top five most common anxiety-inducing situations5.

The origins of dental anxiety are multifactorial. Environmental factors such as the clinical setting, the sounds and appearance of dental instruments, and the distinctive smells of a dental clinic contribute to heightened anxiety. Additionally, low pain tolerance, past traumatic dental experiences, and ineffective communication between patient and dentist—and lack of trust in dentists—may contribute significantly to dentist anxiety6,7. Patients may be more anxious when they feel that the dentist is not establishing a supportive relationship8. These factors are further compounded by demographic influences such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status. For example, younger patients generally report higher levels of anxiety9. Regarding gender differences, substantial epidemiological evidence from studies and systematic reviews suggests that female patients tend to experience and report higher levels of dental anxiety than males. This gender disparity has been consistently observed across populations and age groups10,11,12,13,14. Various biological, psychological, and sociocultural mechanisms have been proposed to explain this difference. Biologically, hormonal fluctuations are known to regulate emotional responses and anxiety sensitivity in women15. Psychologically, women may exhibit greater emotional expressiveness16. From a sociocultural perspective, societal norms may inhibit men from expressing their fears17. However, it is important to note that some studies have not reported statistically significant gender differences in dental fear18,19, suggesting that individual variability also plays an important role. In a longitudinal study, dental anxiety has shown that it is associated with depression and anxiety symptoms, especially in women. Findings show that dental anxiety is related to environmental factors as well as psychological factors20.

Menstrual cycle phases are another potential influence on anxiety in women21. The complex relationship between fear responses and the menstrual cycle can be influenced by psychological factors, individual differences, and hormonal fluctuations15. The menstrual cycle, regulated by hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, affects not only physical health but also emotional and psychological states21. Research has shown that women tend to handle stress more effectively during the proliferative (follicular) phase of their menstrual cycle, a time when estrogen levels are on the rise. However, this changes in the secretory (luteal) phase, when estrogen drops and progesterone becomes more dominant. These hormonal shifts can reduce emotional stability and heighten anxiety, which may make dental procedures feel more distressing than usual22. Understanding the influence menstrual cycle phases on dental anxiety may provide a valuable perspective on the biological underpinnings of anxiety in dental contexts. Previous research has established links between hormonal fluctuations and anxiety responses23,24, but few studies have specifically examined these variations in the context of dental procedures.

Patients are more likely to experience anxiety during interventional procedures such as tooth extraction, fillings, and root canal treatment, which are commonly associated with pain25,26,27,28. One of the most widespread misconceptions among patients about root canal treatment is its association with excessive pain29,30. Consequently, the anticipation of a negative experience may further heighten anxiety levels31. Therefore, investigating the relationship between root canal treatment and anxiety is important for understanding patients’ attitudes toward dental care and for developing more effective anxiety management strategies in clinical practice. Despite these findings, the relationship between menstrual cycle phases and dental anxiety has not been sufficiently investigated, especially in the context of endodontic procedures such as root canal treatment. Understanding the influence of menstrual cycle phases on dental anxiety can provide valuable insights into the biological basis of anxiety in the dental context. By exploring these understudied areas, the current research may contribute to the development of more specific treatment approaches that take hormonal influences on dental anxiety into account. Such insights are particularly important in the context of endodontic procedures, which tend to cause greater anxiety due to their invasive techniques and close association with pain32.

This study aims to investigate the relationship between menstrual cycle phases and dental anxiety in women undergoing root canal treatment and to examine gender differences in anxiety. Two null hypotheses were tested: (1) anxiety severity in female patients does not vary across different phases of the menstrual cycle, and (2) there is no difference in anxiety severity between male and female patients undergoing root canal treatment.

Materials and methods

Study design and ethical approval

This analytical cross-sectional study was conducted at the Endodontics Clinic of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University Faculty of Dentistry. Ethical approval was obtained from the Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University Ethics Committee (Approval Number: 2023/185). Data collection took place between September 2023 and October 2024. All participants were informed about the study’s purpose and procedures, and written informed consent was obtained before participation. All data were gathered through structured interviews conducted by trained personnel prior to the dental procedures, ensuring accuracy and consistency in the analysis.

Power analysis

A priori power analysis was performed with G*Power 3.1 (one‑way ANOVA, fixed effects). Assuming a medium effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.25), α = 0.05, and 80% power for four independent groups, the minimum required sample size was 180 participants (≈ 45 per group). Our final sample comprised 259 participants (64, 64, 63, 68 per group, respectively), providing an achieved power of approximately 0.93. Therefore, the study was adequately powered to detect medium or larger differences among groups.

Study population

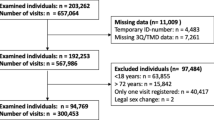

Participants were selected according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure a homogeneous study population representative of the research objectives. Inclusion criteria required participants to be between 18 and 50 years of age and in need of endodontic treatment for at least one tooth. Female participants were eligible if they had regular menstrual cycles, defined as occurring every 21 to 35 days with consistent timing. The menstrual cycles of female patients were calculated using their responses to the questions on the last menstrual period and average cycle length in the questionnaire. The menstrual cycle phases were divided into three phases: menstrual phase (Days 1–4), proliferative phase (Days 5–14) and secretory phase (Days 15–28). Male participants were also included as a comparison group to assess possible gender-based differences in dental anxiety.

Participants were divided into four groups based on gender and menstrual cycle phase:

Group 1: Women in the menstrual phase (n = 64).

Group 2: Women in the proliferative phase (n = 64).

Group 3: Women in the secretory phase (n = 63).

Group 4: Male participants (n = 68).

Exclusion criteria were created to minimize confounding factors that could affect anxiety or vital signs. Patients were excluded if they were currently taking antidepressants, anxiolytics, or hormonal treatments (oral contraceptives, etc.) that could affect anxiety or hormonal balance. Additionally, patients with systemic conditions, including cardiovascular, endocrine, or neurological disorders, were not included. Individuals with diagnosed psychiatric conditions, such as generalized anxiety disorder or depression, were also excluded to avoid interference from pre-existing anxiety or mood disorders. Pregnant women were excluded due to significant hormonal changes unrelated to the menstrual cycle that could impact anxiety levels.

Demographic data collection

Demographic data, including age, gender, and education level, were collected to characterize the study population and control for potential confounding factors. Age was recorded both as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable (18–35 years and 36–50 years), while education level was categorized as primary school, high school, or university. The presence of preoperative pain (yes/no) was also documented to assess its possible impact on anxiety levels. All demographic information was obtained using a structured questionnaire administered prior to the dental procedures.

Anxiety assessment with vital anxiety indicators

In addition to self-reported anxiety scales, vital physiological parameters were recorded as objective measures of anxiety. These included:

Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure: Blood pressure was measured using an manual aneroid sphygmomanometer [Erka Perfect Aneroid, German made]. Normal blood pressure is below 120/80 mmHg33. For healthy adults, systolic blood pressure of 120–139 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure of 80–89 mmHg is considered high34. Oxygen Saturation (SpO2): Oxygen saturation was assessed using a fingertip pulse oximeter (Respirox, Jiangsu, China) to monitor potential respiratory changes associated with anxiety. Normal oxygen saturation in healthy adults typically ranges from 85 to 99%35,36, although low oxygen saturation values may indicate respiratory changes that may be associated with anxiety states37.

Anxiety assessment with self-reported anxiety scales

Severity of anxiety were assessed using two validated scales: STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) and MDAS (Modified Dental Anxiety Scale). Both the MDAS and STAI were used to examine the relationship between dentistry-specific and general anxiety. Including the STAI allowed for assessment of broader psychological anxiety traits that may impact dental experiences. The MDAS is a five-item questionnaire that evaluates dental-specific anxiety. Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not anxious”) to 5 (“extremely anxious”), with total scores ranging from 5 to 25. The MDAS is simple to administer and provides a reliable measure of anxiety related to dental treatments38,39,40. MDAS scores between 5 and 10 suggest low anxiety, while scores from 11 to 18 indicate moderate levels. A score of 19 or more points to high dental anxiety that may require attention40. The STAI consists of two subscales: the STAI-S, which measures anxiety in response to current situations, and the STAI-T, which evaluates general anxiety as a personality trait. Both subscales contain 20 items each, with scores ranging from 20 to 80 for each scale. Scores ≥ 40 on the STAI-S indicate clinically significant state anxiety, while scores ≥ 45 on the STAI-T suggest high trait anxiety41,42. These scales are widely used for their comprehensiveness and reliability43. For this study, validated and reliable Turkish versions of both scales were utilized: the MDAS validated by Tunc, et al.44 and the STAI validated by Öner, et al.43 ensuring their applicability and accuracy in the Turkish population. Participants completed the MDAS and STAI questionnaires before their dental procedures in a calm clinical environment to minimize external influences on their anxiety.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Jamovi software (version 2.3.28). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of continuous variables. Non-normally distributed data were analyzed using non-parametric tests. The Kruskal-Wallis test was employed to compare continuous variables, such as MDAS and STAI scores, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and oxygen saturation, across the four groups. When significant differences were detected, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner test. Categorical variables, such as preoperative pain presence and education level, were analyzed using the Chi-squared test. Results were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic variables (age, education, pre‑operative pain) were evenly distributed across all menstrual‑phase groups and men (all p > 0.05), confirming a well‑matched sample (Table 1).

Physiological anxiety markers—oxygen saturation and systolic/diastolic blood pressure—remained stable across groups (oxygen sat. p = 0.724; systolic p = 0.079; diastolic p = 0.145), indicating no meaningful phase‑ or sex‑related variation (Table 2).

Psychometric analysis showed that MDAS and STAI‑T scores were significantly higher in the menstrual and secretory phases than in men (MDAS: p < 0.001; STAI‑T: p < 0.01), with no differences for the proliferative phase (p > 0.05). State anxiety (STAI‑S) was consistently elevated in women versus men (p < 0.05) but did not fluctuate across phases (Table 3; Fig. 1).

Distribution of Anxiety Scale Scores (MDAS, STAI-S, STAI-T) by Menstrual Cycle Phase and Gender among a Sample of Male and Female Dental Patients (n = 259) in Turkey (MDAS; range 5–25), State Anxiety Scale (STAI‑S; range 20–80), Trait Anxiety Scale (STAI‑T; range 20–80). Data presentation: Boxes show median and interquartile range (IQR); whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values.

Correlation analysis revealed a very strong positive relationship between systolic and diastolic blood pressure (rho = 0.723, p < 0.001) and moderate‑to‑strong associations among the anxiety scales (rho = 0.332–0.478, all p < 0.001), whereas other variable pairs showed weak, non‑significant correlations (Fig. 2).

The results of the multiple regression analysis presented in Table 4 demonstrate that, even after adjusting for demographic and physiological variables, being in the menstrual or secretory phase is independently associated with significantly higher dental (MDAS) and general anxiety scores (STAI-S, STAI-T). Specifically, the menstrual phase was associated with an average increase of approximately 3.5 points in MDAS (p < 0.001), while both the menstrual and secretory phases significantly elevated anxiety scores across all models. In contrast, age, education level, preoperative pain, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation did not show any significant associations with anxiety outcomes. Overall, cyclical hormonal status accounted for about 4–6% of the variance in anxiety scores.

Discussion

This study investigates the relationship between menstrual cycle phase and dental anxiety in women undergoing root canal treatment, while also examining gender differences in anxiety severity. The findings revealed that women experienced significantly higher dental anxiety compared to men, particularly during the menstrual and secretory phases, when anxiety was measured by the MDAS, STAI-S, and STAI-T. However, no major significant changes were observed in anxiety levels across the different menstrual phases. Additionally, demographic characteristics and vital anxiety indicators (blood pressure and oxygen saturation) did not show statistically significant differences between the groups.

In the study, the vital signs (blood pressure and oxygen saturation) of women before the procedure were not affected by the different phases of the menstrual cycle and were similar between women and men. This finding suggests that these values are not significantly affected by anxiety in healthy individuals and that there is no statistically significant difference between men and women. Although there are studies in the literature that support the findings of the study and show that there is no relationship between anxiety and blood pressure changes45, some studies investigating the relationship between blood pressure and dental anxiety have reported that the dental clinic environment and the treatment process can lead to significant increases in blood pressure46,47. Anxiety attacks can contribute to the development of a persistent risk for cardiovascular disease, which can be dangerous especially for people with hypertension48. Although studies showing that oxygen saturation is not affected by dental treatment support the current findings49,50, changes in respiratory patterns caused by anxiety may lower oxygen saturation, potentially disrupting respiratory function and creating a vicious cycle51.

In the present study, women were found to have higher anxiety scores than men across all types of scales. These findings are consistent with several previous studies that reported higher levels of dental anxiety among women, such as those by Khan, et al.52, Doerr et al.53, Marakoğlu et al.54, and Muğlalı et al.55. However, opposing findings have also been reported in the literature, with some studies indicating no significant gender-based differences in dental anxiety56,57,58. This difference between studies may be due to the methodological methods used, such as the study design, sampling techniques, anxiety measurement tools, and psychosocial and cultural differences of the study population. It should be noted that these differences are not universal and may vary in different sample groups. Indeed, preschool children, in whom social behaviors have not yet emerged, tend to express dental anxiety in a similar way59. Therefore, multifaceted studies that consider both biological and sociocultural factors are needed to more accurately assess gender-based anxiety differences. Our results align with the general trend in the literature suggesting that women exhibit greater anxiety responses than men. Although this gender difference was found to be statistically significant in our study, the extent to which it is clinically meaningful remains a complex issue that requires further evaluation. While higher anxiety scores may indicate increased psychological distress, they do not necessarily imply observable treatment-avoidance behaviors or disruptions in clinical procedures. The observed gender disparity in anxiety may reflect deeper emotional and psychological mechanisms shaped by biological, social, and cultural factors. For example, the concept of “gendered behavior” suggests that emotional responses such as fear and anxiety are influenced by societal expectations; men may downplay anxiety to conform to traditional male norms, whereas women may feel more comfortable expressing such emotions17. Muris, et al.60, also found that gender role orientation significantly influences fear responses, with female gender being positively associated with anxiety. Furthermore, it is widely recognized that women tend to exhibit greater emotional openness than men, which may further contribute to differences in reported anxiety levels61. tudies that holistically address these multifaceted and complex gender-related factors may provide deeper insights into the origins of these differences. Given that female patients may experience higher levels of anxiety compared to male patients in clinical practice, adopting more empathic communication strategies and developing sensitive approaches throughout the treatment process may enhance patient satisfaction and treatment compliance. In the present study, the higher anxiety scores observed in female participants may be attributable to the interaction of one or more of these factors. Accordingly, the second null hypothesis of the study, which stated that “there is no difference in terms of fear and anxiety between male and female patients undergoing root canal treatment,” was rejected.

The menstrual cycle is regulated by two important ovarian hormones, estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen affects a wide range of tissue types to variable degrees, initiating or modulating a multiple biological events. Progesterone also affects many tissues, but its effects are more limited and less extensively studied. Fluctuations in the levels of these two hormones lead to significant changes in the female body, with both physical and emotional consequences21. Especially during the secretory phase, when progesterone levels are high and estrogen levels are low, anxiety sensitivity can intensify fear responses62. The secretory phase is associated with a variety of premenstrual symptoms, such as mood swings and physical discomfort, due to hormonal fluctuations63. During this phase, women have been observed to exhibit increased sensitivity to negative emotional stimuli and heightened emotional perception, possibly due to the regulatory effects of progesterone on emotional processing64. This phenomenon may be linked to increased amygdala reactivity during the luteal phase. Glover, et al.22 stated that low estrogen levels are associated with impairments in fear inhibition and suggested that hormonal fluctuations may affect the ability to regulate fear responses. Similarly, Carpenter, et al.65 reported that fear responses may vary across different phases of the menstrual cycle. In addition, conditions such as premenstrual syndrome (PMS) have been reported to lead to heightened panic and anxiety during the premenstrual phase and contributing to increased fear responses66,67. The strong correlations were identified between measures of general anxiety (STAI-S, STAI-T) and dental anxiety (MDAS), highlighting the close relationship between these variables. These results suggest that hormonal fluctuations may affect the severity of dental anxiety in women, whereas the general pattern of state anxiety remains constant across the menstrual cycle. On the STAI-S scale, which assesses the patient’s current state of anxiety, anxiety severity was similar in women in different menstrual phases but significantly different from men. On the other hand, on the STAI-T scale, which assesses overall anxiety levels, no significant differences were observed between women or between women and men in the proliferative phase. These findings suggest that women’s mood changes may be influenced by menstrual periods. Questionnaires that include questions directly related to dental treatment, such as the MDAS, may produce different anxiety scores in response to the unknown, whereas scales that assess general anxiety about life, such as the STAI, may produce different responses. This difference may be due to patients’ lack of knowledge about dental treatment.

The increase in dental anxiety observed during menstrual and secretory phases in the study is consistent with current understanding of the anxiolytic effects of estrogen through neuromodulation. In women, there is an interaction between estrogen and serotonin that affects mood, cognition and various physiological processes. Hiroi, et al.68 showed that estrogen differentially activates tryptophan hydroxylase-2 (TpH2) in specific brain regions, thereby regulating serotonin levels. This effect is thought to result from estrogen’s modulation of neurotransmitter systems, particularly its role in balancing GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission in the brain69. The proliferative phase, characterized by high estrogen levels, showed anxiety scores similar to those of male participants, suggesting that estrogen may have a protective effect against dental anxiety. This finding is consistent with the study by Renczés, et al.70. Similarly, Khaleghi, et al.71 showed that higher estrogen levels were associated with a decrease in anxiety-like behaviors. Accordingly, the first null hypothesis of the study, “Fear and anxiety of female patients undergoing root canal treatment do not vary according to menstrual cycle phases” was rejected.

Study strengths

Despite these limitations, our study represents an important step in understanding the effects of menstrual cycle phases on dental anxiety and may provide a foundation for future research in this area. Our comprehensive assessment approach included both self-reported anxiety measures (MDAS, STAI-S, STAI-T) and objective physiological indicators (blood pressure and oxygen saturation), providing a multidimensional view of anxiety responses. Furthermore, our focus on root canal treatment provides valuable insights for endodontists and general dentists performing root canal treatments. Third, the interaction of menstrual periods with individual biological and psychological factors (e.g. stress, sleep patterns) was not considered. As fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone levels may have different effects on anxiety among individuals, not controlling for these factors may limit the generalizability of our findings. Finally, our study focused on a specific clinical scenario (root canal treatment) and may not be generalizable to other dental procedures or contexts. Furthermore, the relatively homogeneous nature of our findings from a single institution may limit the generalizability of our findings to a broader population. Future research should aim to clarify these questions using detailed sociodemographic data, personal information on the person’s life and laboratory findings (blood, saliva) to clearly define the menstrual cycle.

Study limitations

To standardize the study, we selected women with regular menstrual cycles, but the menstrual cycle was recorded by calculating the endometrial phase based on the calendar reported by the women. This is a limitation of the study as it requires calculations based only on the time frame provided by the patient. Given that hormone levels can vary significantly between individuals and may be influenced by multiple factors, this approach may affect the internal validity of our findings. Future studies should include serum or salivary hormone level measurements to more accurately define menstrual cycle phases. Second, a limitation is the exclusion of postmenopausal women from our study. Including these groups would provide valuable comparative data on anxiety levels. This limitation represents an important area for future research. Third, a limitation of the study is that certain individual and environmental factors that can influence anxiety were not controlled for. General stress levels, previous dental experiences, sleep quality, and lifestyle habits (such as caffeine consumption and physical activity) may act as potential confounders affecting the relationship between menstrual cycle phases and anxiety levels. Future studies that comprehensively evaluate such individual differences may contribute to a more accurate and in-depth understanding of the association between the menstrual cycle and anxiety.

Additionally, our study design did not include baseline anxiety measures taken at a time other than the dental appointment. This limitation makes it difficult to distinguish between trait anxiety and state anxiety resulting from the dental procedure. Future studies should consider including baseline measures taken days before the dental appointment to better isolate the effects of the dental context from general anxiety tendencies. Although this study found significant associations between menstrual cycle phases and dental anxiety levels, it is important to recognize that the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences. A longitudinal approach following the same individuals at different stages of the menstrual cycle would have reduced interindividual variability and allowed for a more controlled assessment of hormonal effects. However, this method was not feasible due to practical limitations in the clinical setting in which the study was conducted. These limitations included the need for multiple root canal sessions per participant, difficulties in matching treatment dates to specific menstrual phases, and the risk of participant withdrawal from the study. Therefore, a cross-sectional design was chosen because it allowed data to be collected from a larger and more diverse sample within a limited time period. Future studies should consider adopting a longitudinal design for a more accurate assessment.

Furthermore, this study included physiological parameters such as blood pressure and oxygen saturation to complement self-reported anxiety measures, it is important to acknowledge that these are indirect and relatively nonspecific indicators of acute psychological stress. More sensitive biomarkers such as heart rate variability (HRV) or salivary cortisol levels could have provided a more nuanced understanding of the physiological response to anxiety. However, due to practical constraints in the clinical setting and the need for non-invasive, easily applicable methods, these more advanced biomarkers were not employed. Future studies should consider incorporating HRV monitoring or salivary cortisol analysis to better capture physiological responses associated with acute dental anxiety.

Moreover, this study assessed anxiety levels only in the preprocedural period. While this approach was chosen to capture anticipatory anxiety and to minimize disruption during clinical care, it does not account for dynamic changes in anxiety that may occur during or after the dental procedure. Intraprocedural assessments were not conducted due to the invasive nature of root canal treatment, which made it impractical to administer questionnaires during treatment. Postprocedural assessments were also avoided to minimize recall bias. Future studies could incorporate multiple time-point measurements, including during and after the procedure, to more comprehensively assess anxiety trajectories.

Lastly, menstrual cycle phases were determined based on participants’ self-reported calendar data, including the date of the last menstrual period and average cycle length. This approach may be prone to recall bias, as participants may not accurately remember or report this information. Such misclassification could potentially affect the internal validity of the phase-based comparisons. Future studies should consider integrating hormonal validation (e.g., salivary estradiol or progesterone levels) to more precisely determine menstrual phases and minimize recall-related errors.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that women are especially vulnerable to heightened dental anxiety during both the menstrual and secretory phases of their cycle, regardless of age, education, preoperative pain, or physiological status. Recognizing these cyclical patterns offers clinicians a valuable opportunity to anticipate and address anxiety-related challenges in female patients. By taking menstrual cycle phase into account when planning and delivering dental care, practitioners can develop more individualized approaches that improve patient comfort, satisfaction, and overall treatment outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available considering that we have not required consents to publish this data, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bandyopadhyay Prasanta, S. et al. American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Dsm-5, Washington, DC, 2013. Ananth Mahesh, In defense of an evolutionary concept of health nature, norms, and human biology, Aldershot, England, Ashgate. Philosophy 39:683–724. (2014).

Armfield, J. M. What goes around comes around: Revisiting the hypothesized vicious cycle of dental fear and avoidance. Commun. Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 41, 279–287 (2013).

Berggren, U. & Meynert, G. Dental fear and avoidance: Causes, symptoms, and consequences. J. Am. Dent. Assoc (1939) . 109, 247–251. (1984).

Bohman, W., Lundgren, J., Berggren, U. & Carlsson, S. Psychosocial and dental factors in the maintenance of severe dental fear. Swed. Dent. J. 34, 121 (2010).

Hägglin, C., Berggren, U., Hakeberg, M., Hallstrom, T. & Bengtsson, C. Variations in dental anxiety among Middle-aged and elderly women in sweden: A longitudinal study between 1968 and 1996. J. Dent. Res. 78, 1655–1661. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345990780101101 (1999).

ter Horst, G. & de Wit, C. A. Review of behavioural research in dentistry 1987–1992: Dental anxiety, dentist-patient relationship, compliance and dental attendance. Int. Dent. J. 43, 265–278 (1993).

Willumsen, T., Lein, J. P. Å., Gorter, R. C. & Myran, L. Oral Health Psychology: Psychological Aspects Related To Dentistry (Springer, 2022).

Kheir, O. O. et al. Patient–dentist relationship and dental anxiety among young Sudanese adult patients. Int. Dent. J. 69, 35–43 (2019).

Egbor, P. E. & Akpata, O. An evaluation of the sociodemographic determinants of dental anxiety in patients scheduled for intra-alveolar extraction. Libyan J. Med. 9 https://doi.org/10.3402/ljm.v9.25433 (2014).

Silveira, E. R., Cademartori, M. G., Schuch, H. S., Armfield, J. A. & Demarco, F. F. Estimated prevalence of dental fear in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. 108, 103632 (2021).

Galletti, C. et al. Dental Anxiety, Quality of Life and Body Image: Gender Differences in Italian and Spanish Population (Minerva Dental and Oral Science, 2023).

Guentsch, A. et al. Oral health and dental anxiety in a German practice-based sample. Clin. Oral Invest. 21, 1675–1680 (2017).

Yildirim, T. T. et al. Is there a relation between dental anxiety, fear and general psychological status? PeerJ 5, e2978 (2017).

Tarrosh, M. Y. et al. A systematic review of cross-sectional studies conducted in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on levels of dental anxiety between genders and demographic groups. Med. Sci. Monitor Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 28, e937470–e937471 (2022).

Glover, E. M. et al. Inhibition of fear is differentially associated with cycling Estrogen levels in women. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 38, 341–348 (2013).

Kring, A. M. & Gordon, A. H. Sex differences in emotion: Expression, experience, and physiology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 686 (1998).

Rader, N. E. & Cossman, J. S. Gender differences in U.S. College students’ fear for others. Sex. Roles. 64, 568–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9940-5 (2011).

Talo Yildirim, T. et al. Is there a relation between dental anxiety, fear and general psychological status? PeerJ 5, e2978–e2978. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2978 (2017).

Dereci, O., Saruhan, N. & Tekin, G. The comparison of dental anxiety between patients treated with impacted third molar surgery and conventional dental extraction. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/7492852 (2021).

Hagqvist, O. et al. Changes in dental fear and its relations to anxiety and depression in the FinnBrain birth cohort study. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 128, 429–435 (2020).

Berga, S. L. The menstrual cycle and related disorders. Female Reproduct. Dysfunct. 23–37. (2020).

Glover, E. et al. Inhibition of fear is differentially associated with cycling Estrogen levels in women. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 38, 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.120129 (2013).

Sundström Poromaa, I. & Gingnell, M. Menstrual cycle influence on cognitive function and emotion processing—from a reproductive perspective. Front. NeuroSci. 8, 380 (2014).

Ossewaarde, L. et al. Neural mechanisms underlying changes in stress-sensitivity across the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 47–55 (2010).

Maggirias, J. & Locker, D. Psychological factors and perceptions of pain associated with dental treatment. Commun. Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 30, 151–159 (2002).

Heaton, L. J., Carlson, C. R., Smith, T. A., Baer, R. A. & de Leeuw, R. Predicting anxiety during dental treatment using patients’ self-reports: Less is more. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 138, 188–195 (2007).

Prathima, V., Anjum, M. S., Reddy, P. P., Jayakumar, A. & Mounica, M. Assessment of anxiety related to dental treatments among patients attending dental clinics and hospitals in Ranga Reddy District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Oral Health Prevent. Dentistry 12. (2014).

Salim Rayman, R. D. H. M., Dincer, E. & Khalid Almas, B. Managing dental fear and anxiety. NY State Dent. J. 79, 25 (2013).

Klages, U., Ulusoy, Ö., Kianifard, S. & Wehrbein, H. Dental trait anxiety and pain sensitivity as predictors of expected and experienced pain in stressful dental procedures. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 112, 477–483 (2004).

Watkins, C. A., Logan, H. L. & Kirchner, H. L. Anticipated and experienced pain associated with endodontic therapy. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 133, 45–54 (2002).

Grupe, D. W. & Nitschke, J. B. Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated Neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 488–501 (2013).

Carter, A. E., Carter, G., Boschen, M., AlShwaimi, E. & George, R. Pathways of fear and anxiety in dentistry: A review. World J. Clin. Cases WJCC. 2, 642 (2014).

Aronow, W. S. Initiation of antihypertensive therapy. Ann. Transl. Med. 6, 44 (2018).

Chobanian, A. V. et al. Seventh report of the joint National committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension 42, 1206–1252 (2003).

Levander, M. S. & Grodzinsky, E. The Development of Algorithms for Individual Ranges of Body Temperature and Oxygen Saturation in Healthy and Frail Individuals (Book title, 2024).

Hagman, I. & Grodzinsky, E. Interpretation of body temperature and oxygen saturation based on individual normal ranges in habitual condition: A step forward for applied precision medicine. Med. Res. Arch. 11 (2023).

Burtscher, J. et al. The interplay of hypoxic and mental stress: Implications for anxiety and depressive disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 138, 104718 (2022).

Humphris, G. M., Morrison, T. & Lindsay, S. The modified dental anxiety scale: Validation and united Kingdom norms. Community Dent. Health. 12, 143–150 (1995).

Humphris, G., Freeman, R., Campbell, J., Tuutti, H. & D’souza, V. Further evidence for the reliability and validity of the modified dental anxiety scale. Int. Dent. J. 50, 367–370 (2000).

Humphris, G. M., Dyer, T. A. & Robinson, P. G. The modified dental anxiety scale: UK general public population norms in 2008 with further psychometrics and effects of age. BMC Oral Health. 9, 1–8 (2009).

Spielberger, C. D. Assessment of State and Trait Anxiety: Conceptual and Methodological Issues (Southern Psychologist, 1985).

Julian, L. J. Measures of anxiety. Arthritis Care Res. 63, 20561. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr (2011).

Öner, N. & LeCompte, W. A. Durumluluk-süreklilik Kaygı Envanteri: El Kitabı (Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi, 1998).

Tunc, E. P., Firat, D., Onur, O. D. & Sar, V. Reliability and validity of the modified dental anxiety scale (MDAS) in a Turkish population. Commun. Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 33, 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00229.x (2005).

Benjamins, C., Schuurs, A. H., Asscheman, H. & Hoogstraten, J. Anxiety and blood pressure prior to dental treatment. Psychol. Rep. 67, 371–377 (1990).

Seto, M., Kita, R., Ishida, S. & Kondo, S. White coat hypertension in well-controlled hypertensives during dental surgery‐A case series. Oral Sci. Int. 17, 201–204 (2020).

Gil-Abando, G. et al. Assessment of clinical parameters of dental anxiety during noninvasive treatments in dentistry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 11141 (2022).

Celano, C. M., Daunis, D. J., Lokko, H. N., Campbell, K. A. & Huffman, J. C. Anxiety disorders and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 18, 1–11 (2016).

Olivieri, J. G. et al. Dental anxiety, fear, and root Canal treatment monitoring of heart rate and oxygen saturation in patients treated during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: An observational clinical study. J. Endod. 47, 189–195 (2021).

Alghareeb, Z., Alhaji, K., Alhaddad, B. & Gaffar, B. Assessment of dental anxiety and hemodynamic changes during different dental procedures: A report from Eastern Saudi Arabia. Eur. J. Dentistry. 16, 833–840 (2022).

Alishah, M., Bagheri-Nesami, M., Babaei, S. R. & Alishah, M. Death anxiety and its predictors among the companions of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J. Multidisciplinary Care. 10, 70–74 (2021).

Khan, S., Sarwat, S. & Khan, H. Dental anxiety in relationship to demographic variables and dental visiting habits among dental patients. Pakistan J. Appl. Psychol. (PJAP). 3, 236–242. https://doi.org/10.52461/pjap.v3i1.1299 (2023).

Doerr, P. A., Lang, W. P., Nyquist, L. V. & Ronis, D. L. Factors associated with dental anxiety. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 129, 1111–1119. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0386 (1998).

Marakoğlu, İ., Demirer, S., Özdemir, D. & Sezer, H. Periodontal Tedavi öncesi Durumluk ve Süreklik Kaygı Düzeyi. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi Diş Hekimliği Fakültesi Dergisi. 6, 73–79 (2003).

Muğlalı, M. & Kömerik, N. Ağız cerrahisi ve Anksiyete. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi Diş Hekimliği Fakültesi Dergisi. 8, 85 (2005).

Berggren, U. & Carlsson, S. G. Psychometric measures of dental fear. Commun. Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 12, 319–324 (1984).

Appukuttan, D. P., Tadepalli, A., Cholan, P. K., Subramanian, S. & Vinayagavel, M. Prevalence of dental anxiety among patients attending a dental educational institution in chennai, India–a questionnaire based study. Oral Health Dent. Manag. 12, 289–294 (2013).

Economou, G. C. Dental anxiety and personality: Investigating the relationship between dental anxiety and Self-Consciousness. J. Dent. Educ. 67, 970–980. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.0022-0337.2003.67.9.tb03695.x (2003).

Torriani, D. et al. Dental caries is associated with dental fear in childhood: Findings from a birth cohort study. Caries Res. 48, 263–270 (2014).

Muris, P., Meesters, C. & Knoops, M. The relation between gender role orientation and fear and anxiety in Nonclinic-Referred children. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 34, 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3402_12 (2005).

Madden, T. E., Barrett, L. F. & Pietromonaco, P. R. Sex Differences in Anxiety and Depression: Empirical Evidence and Methodological Questions. Book Title (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Lovick, T. A. & Zangrossi, H. Effect of estrous cycle on behavior of females in rodent tests of anxiety. Front. Psychiatry. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.711065 (2021).

Naher, L. A. D., Begum, N. & Ferdousi, S. Sympathetic nerve function status and their relationships with ovarian hormones in healthy young women. J. Banglad. Soc. Physiologist. 11, 13–17. https://doi.org/10.3329/jbsp.v11i1.29704 (2016).

Liu, M. et al. Opposite effects of estradiol and progesterone on woman’s disgust processing. Front. Psychiatry. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1161488 (2023).

Carpenter, J. K., Bragdon, L. & Pineles, S. L. Conditioned physiological reactivity and PTSD symptoms across the menstrual cycle: Anxiety sensitivity as a moderator. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy. 14, 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001129 (2022).

Milad, M. R. et al. The influence of gonadal hormones on conditioned fear extinction in healthy humans. Neuroscience 168, 652–658 (2010).

Indusekhar, R. & O’Brien, S. Psychological aspects of premenstrual syndrome. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 21, 207–220 (2007).

Hiroi, R., McDevitt, R. A., Morcos, P. A., Clark, M. S. & Neumaier, J. F. Overexpression or knockdown of rat Tryptophan hyroxylase-2 has opposing effects on anxiety behavior in an estrogen-dependent manner. Neuroscience 176, 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.019 (2011).

Khaleghi, M. et al. Estrogen attenuates physical and psychological stress-induced cognitive impairments in ovariectomized rats. Brain Behav. 11 https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2139 (2021).

Renczés, E. et al. The role of Estrogen in anxiety-like behavior and memory of middle-aged female rats. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 570560 (2020).

Khaleghi, M. et al. Estrogen attenuates physical and psychological stress-induced cognitive impairments in ovariectomized rats. Brain Behav. 11, e02139 (2021).

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Ç.Ö writed and investigated the study, Ö.H conducted data analysis, A.Ş.Ç reviewed and edited, F.P.H designed and reviewed and edited. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University Ethics Committee (Approval Number: 2023/185).

Informed consent

All participants were informed about the study’s purpose and procedures, and written informed consent was obtained before participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Çoban Öksüzer, M., Hatipoğlu, Ö., Şanal Çıkman, A. et al. Preoperative dental anxiety across menstrual cycle phases in women undergoing root canal treatment. Sci Rep 15, 35442 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19374-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19374-z