Abstract

Adolescent mental health has garnered increasing attention worldwide, necessitating greater understanding of its dynamic predictors over time. While sport participation is widely recognized for its psychological benefits, the longitudinal mechanisms through which it relates to self-control ability and mental health remain underexplored. This study aimed to examine the temporal associations among sport participation, self-control ability, and mental health in adolescents across a one-year period. A three-wave longitudinal survey was conducted among 1,306 Chinese adolescents, with data collected at three time points within a single academic year. Cross-lagged panel modeling revealed that sport participation at Time 1 significantly predicted self-control ability (β = 0.18) and mental health (β = 0.25) at Time 2, and sport participation at Time 2 predicted self-control ability (β = 0.12) and mental health (β = 0.08) at Time 3. Self-control ability at Time 1 predicted mental health at Time 2 (β = 0.30), and self-control at Time 2 predicted mental health at Time 3 (β = 0.17). A reciprocal direction of influence was also identified: mental health at Time 1 predicted self-control ability at Time 2 (β = 0.23), and mental health at Time 2 predicted self-control ability at Time 3 (β = 0.23). Multi-group structural analyses further demonstrated that the identified cross-lagged associations were invariant across gender, school stage, residence type, and sports type, indicating structural stability of the model across diverse subgroups. These findings support a mutually reinforcing relationship between sport participation, self-regulatory development, and psychological functioning in adolescence, with implications for theory-based school health promotion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescence constitutes a critical stage of human development marked by rapid physical maturation, emotional fluctuation, and cognitive reorganization, during which individual trajectories of psychological health are shaped with enduring consequences for adult well-being and social adaptation1. In response to mounting concerns over the global burden of adolescent mental health challenges, sustained efforts have been directed toward identifying modifiable behavioral factors that may foster psychological resilience and developmental competence. Among such factors, sport participation, which is defined as structured and recurrent engagement in organized physical activity with clearly delineated rules and goals, has attracted growing interdisciplinary interest, not only for its physiological benefits such as improvements in cardiovascular endurance and musculoskeletal strength2,3,4, but also for its potential contributions to psychological outcomes including emotional regulation, stress recovery, and affective well-being5,6. While existing literature often centers on general physical activity, emerging evidence has suggested that sport-based formats, due to their goal-directed, socially interactive, and discipline-oriented nature, may exert distinct effects on adolescents’ self-regulatory systems and mental health indicators7,8.

Among the psychological resources relevant to adolescent development, self-control occupies a foundational position as a capacity to manage impulses, delay gratification, and flexibly adjust behavior in accordance with long-term goals9. It has been consistently associated with academic success, emotional stability, and prosocial functioning, and is increasingly regarded as a core competence underlying resilience against mental health difficulties. Prior empirical studies have indicated that consistent sport participation, particularly within contexts demanding effort regulation and persistence, facilitates the development of self-control10, which in turn mitigates internalizing symptoms and enhances social adaptation11. Nevertheless, most existing research has employed cross-sectional designs, thereby limiting the capacity to ascertain temporal ordering or to test hypotheses concerning reciprocal influence. Given the developmental interdependence of sport participation, self-control, and mental health, it remains imperative to examine not only the prospective effects of sport participation on psychological functioning but also the potential feedback pathways through which mental health status may influence behavioral engagement and self-regulatory development.

This study seeks to address these theoretical and methodological limitations by employing a three-wave cross-lagged panel design to explore the dynamic longitudinal associations among sport participation, self-control ability, and mental health in a large sample of Chinese adolescents. Drawing upon self-determination theory (SDT), which posits that sustained engagement in structured activities fosters psychological growth through the fulfillment of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs, and the framework of positive youth development (PYD), which emphasizes asset-building through socially embedded opportunities, the present research examines how sport participation contributes to adolescents’ psychological adjustment via self-regulatory mechanisms. The study also tests for structural invariance across gender, school stage, residence type, and sports type, thereby evaluating the generalizability of the proposed developmental model across key demographic subgroups and advancing context-sensitive understanding of adolescent mental health promotion.

Literature review and research hypotheses

Theoretical foundations

This study is grounded in two complementary theoretical frameworks, namely SDT and PYD, both of which offer integrated perspectives on the developmental mechanisms linking sport participation, self-control, and mental health in adolescence. According to SDT, human functioning is optimized when three basic psychological needs are fulfilled: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When adolescents engage in sport activities that allow them to experience personal agency, demonstrate skill mastery, and form meaningful social bonds, their intrinsic motivation is enhanced, which subsequently promotes behavioral persistence and internalized self-regulation. In this motivational context, sport participation becomes not merely a physical practice but a developmental experience that fosters regulatory control and emotional well-being through sustained engagement in challenging and socially embedded activities12,13.

From the perspective of PYD, sport participation is conceptualized as a structured opportunity for adolescents to develop internal strengths and social assets. Through regular engagement in individual or team-based sports, adolescents are exposed to situations that require emotional regulation, adaptive coping, and interpersonal cooperation, all of which serve as protective factors against psychological distress. In addition to promoting physical competence, such contexts also contribute to the development of psychosocial resources that are essential for sustained mental health. Prior studies have identified sport-based environments as key settings in which adolescents practice and consolidate self-regulatory behaviors while building resilience and positive identity14,15,16.

Integrating these frameworks, the present study conceptualizes sport participation as a contextually grounded and motivationally infused developmental environment. Within this environment, self-control is not only cultivated through repeated engagement in structured activity but also serves as a mechanism that reinforces psychological health outcomes over time. The reciprocal and longitudinal associations among sport participation, self-control, and mental health are thus hypothesized to reflect a cyclical developmental process in which behavioral engagement and psychological adjustment interact in mutually sustaining ways.

Sport participation and adolescent development

Adolescence represents a period of accelerated growth across physical, emotional, and cognitive domains, during which sport participation functions not only as a medium for physical conditioning but also as a developmental context conducive to psychological adjustment. Substantial empirical evidence has demonstrated that regular engagement in sport-based activities contributes to improved cardiovascular health, muscular endurance, and skeletal integrity, while also playing a protective role in the reduction of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and stress-related outcomes3,4,17. These psychological benefits are closely linked to the behavioral structure and social affordances inherent in sport settings, which emphasize goal orientation, persistence, and rule adherence, thereby providing adolescents with opportunities to exercise effortful control and behavioral regulation in socially meaningful contexts.

Moreover, sport participation facilitates the development of self-regulatory competencies that are essential for navigating the increasing demands of academic life and peer interactions. Through repeated exposure to tasks requiring focus, sustained attention, and strategic adaptation, whether situated within team-based settings or individual formats, adolescents develop enhanced capacities for impulse control, goal-directed decision-making, and emotional modulation18,19,20,21. These competencies are particularly salient in organized sport environments, which embed individual agency within collective pursuits and foster cooperation, mutual accountability, and resilience. In such contexts, psychological growth is not merely a by-product of physical exertion but a core developmental outcome shaped by structured participation and relational engagement. These psychosocial processes collectively support more stable emotional functioning and contribute to long-term mental health trajectories across adolescence22.

The role of self-control ability in sport participation and mental health

Self-control represents a foundational psychological capacity in adolescence, encompassing the ability to modulate attention, emotion, and behavior in accordance with situational demands and long-term objectives23. This capacity enables individuals to suppress impulsive tendencies, tolerate delay of gratification, and make intentional decisions that align with personally or socially valued goals. Adolescents demonstrating higher self-control are more likely to exhibit consistent academic engagement, emotional stability, and adaptive social functioning, as they are better equipped to manage stress, overcome distractions, and navigate complex interpersonal situations24,25,26.

In relation to health-related behaviors, self-control plays a critical role in facilitating the initiation and maintenance of structured routines such as sport participation. Individuals with stronger regulatory capacity are more inclined to adhere to demanding physical activity schedules, manage discomfort associated with training, and sustain motivation in the face of setbacks, thereby supporting long-term benefits for both physical health and psychological adjustment27,28. Furthermore, self-control is positively associated with the adoption of constructive coping strategies, including cognitive reframing and help-seeking, which enhance resilience and reduce vulnerability to emotional disturbances29,30. Conversely, deficits in self-control are consistently linked to avoidant coping styles, impulsive decision-making, and engagement in health-compromising behaviors, all of which heighten the risk for psychological distress during adolescence31.

The direct and indirect effects of sport participation on mental health

Sport participation contributes to adolescent mental health through multiple, interrelated pathways that encompass both intrapersonal regulation and social-environmental resources. Directly, engagement in structured sport activities fosters emotional balance and psychological resilience by enhancing perceptions of competence, autonomy, and relatedness, the three foundational psychological needs emphasized by self-determination theory. When these needs are satisfied through consistent and meaningful physical activity, adolescents are more likely to experience elevated intrinsic motivation, which supports psychological well-being and buffers against internalizing symptoms. This motivational mechanism is further reinforced by repeated experiences of mastery and self-efficacy gained through sport engagement, which foster positive self-appraisals and emotional self-assurance32,33.

In parallel, sport participation facilitates the development of self-regulatory skills that indirectly protect mental health. Regular involvement in physically demanding and socially organized contexts requires the exercise of impulse control, delay of gratification, and emotional self-monitoring, all of which contribute to enhanced executive functioning and behavioral stability. These regulatory competencies improve adolescents’ capacity to manage stressors, make goal-consistent decisions, and maintain psychological coherence in the face of environmental challenges18,19. From a relational standpoint, team-based sport activities offer structured opportunities for peer collaboration, mutual responsibility, and social affiliation, which cultivate perceived social support and reduce vulnerability to emotional isolation. These interpersonal experiences are particularly relevant during adolescence, a period when peer belonging becomes a critical determinant of emotional well-being34,35.

The feedback effect of mental health on sport participation and self-control ability

Mental health not only emerges as an outcome of sport participation and self-regulatory development but also plays a formative role in sustaining these adaptive behaviors over time. Adolescents who experience greater psychological well-being typically exhibit stronger motivation to engage in sport-based activities, as emotional stability and positive affect promote the initiation and maintenance of physical routines36. In such cases, adolescents are more likely to perceive physical activity as rewarding and purposeful, which reinforces continued involvement and facilitates the internalization of health-promoting behaviors37.

In parallel, mental health supports the cultivation of self-control by enhancing emotional clarity, cognitive coherence, and behavioral consistency. When adolescents experience lower levels of psychological distress, they are more capable of managing impulses, maintaining goal-oriented focus, and implementing strategic responses to environmental challenges38,39,40. This self-regulatory advantage, in turn, strengthens adherence to beneficial habits, including regular participation in sport activities. Consequently, mental health contributes not only to the immediate experience of emotional well-being but also to the long-term maintenance of self-discipline and behavioral stability.

Research hypotheses

Anchored in the conceptual foundations of self-determination theory and positive youth development, and informed by the empirical gaps delineated above, the present study advances the following hypotheses to guide the examination of cross-lagged relationships among sport participation, self-control ability, and mental health over time:

H1: Sport participation at Time 1 positively predicts mental health at Time 2, and sport participation at Time 2 positively predicts mental health at Time 3.

H2: Sport participation at Time 1 positively predicts self-control ability at Time 2, and sport participation at Time 2 positively predicts self-control ability at Time 3.

H3: Self-control ability at Time 1 positively predicts sport participation at Time 2, and self-control ability at Time 2 positively predicts sport participation at Time 3.

H4: Self-control ability at Time 1 positively predicts mental health at Time 2, and self-control ability at Time 2 positively predicts mental health at Time 3.

H5: The longitudinal influence of sport participation on mental health is mediated by self-control ability.

H6: Mental health at Time 1 positively predicts sport participation at Time 2, and mental health at Time 2 positively predicts sport participation at Time 3.

H7: Mental health at Time 1 positively predicts self-control ability at Time 2, and mental health at Time 2 positively predicts self-control ability at Time 3.

Based on the above hypotheses, we propose the following theoretical model to examine the cross-lagged relationships among sport participation, self-control ability, and mental health across three time points (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Research participants and data

Sample size justification

To determine an adequate sample size for the planned statistical analyses, an a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1. The analysis was based on a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), a significance level of α = 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.80. Under these parameters, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 350 participants. In addition to this criterion, standard methodological recommendations in social science research suggest a sample size approximately 10 to 15 times the number of questionnaire items. As the final instrument contained 39 items, this guideline indicated a recommended range of 390 to 585 participants. The present study retained 1,306 valid cases, which substantially exceeded both the power analysis threshold and empirical guidelines for model estimation in structural equation modeling.

Participant selection process

To ensure broad demographic and geographic representativeness, the study employed a stratified multistage random sampling strategy across five major regions of mainland China. These regions, namely eastern, central, western, southern, and northern China, were selected to capture national diversity in socioeconomic development and educational conditions. Within each of the five regions, three provinces were randomly chosen, resulting in a total of fifteen provinces. Schools were then randomly sampled within these provinces, followed by the random selection of students enrolled in Grades 7 through 12, corresponding to the upper stages of primary education and the entirety of lower secondary schooling. This hierarchical sampling framework preserved randomization at each level and ensured adequate coverage of the adolescent population across diverse regional contexts. The detailed provincial distribution of the sample is reported in Table 1.

Data collection methods

Data collection was conducted in accordance with a standardized protocol designed to ensure procedural consistency, respondent comprehension, and data quality. Prior to implementation, members of the research team delivered structured training sessions to designated physical education and homeroom teachers at participating schools. These instructors were responsible for administering the surveys under supervised classroom conditions and monitoring adherence to standardized procedures. All adolescent participants were provided with a verbal explanation of the study objectives and ethical safeguards. Written informed consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians, and verbal assent was secured from the students themselves. Throughout the process, strict confidentiality and anonymity were maintained in compliance with ethical research standards and institutional guidelines.

Data processing

The same cohort of students was surveyed at three distinct time points between September 2023 and September 2024, using an identical set of instruments to ensure consistency. To uphold data integrity, the research team applied predefined screening criteria to exclude invalid questionnaires, specifically those with missing responses, logical inconsistencies, or evident patterns of disengagement. The first wave of data collection took place on September 1, 2023, yielding 1,467 valid responses from 1,600 distributed questionnaires, corresponding to a 91.69% response rate. The second wave, conducted on March 1, 2024, retained 1,384 valid responses from the original sample (94.34%), while the third wave, administered on September 1, 2024, obtained 1,306 valid responses (94.36%).

Surveys were spaced approximately five months apart, with no interventions applied during the intervals. This timing, based on adolescent development and best practices in longitudinal research, captures key transitions in academic cycles and minimizes short-term disruptions41. Empirical studies on adolescent development support 5–6 month intervals for observing meaningful changes in cognitive and behavioral patterns42. Basic demographic information of the respondents is presented in Table 2.

Measurement

Sport participation

Sport participation was measured using the Physical Activity Rating Scale (PARS-3), which was adapted for use in Chinese populations by Liang43. This instrument captures structured physical engagement through three dimensions: exercise intensity, exercise duration, and exercise frequency. Each dimension is assessed using a five-point Likert-type item, ranging from one to five. Specifically, intensity is rated from light to vigorous, duration from less than ten minutes to more than one hour, and frequency from once per month to almost daily. The final score is calculated by multiplying the three dimension scores and applying a weighting coefficient to yield a composite index ranging from 0 to 100. Previous research has confirmed the reliability, construct validity, and applicability of the PARS-3 for assessing sport-related physical activity among Chinese adolescents44.

Self-control ability

Self-control ability was assessed using the Chinese version of the Brief Self-Control Scale, developed and validated by Luo et al.45. This instrument comprises seven items designed to capture key aspects of behavioral regulation, including impulse inhibition, goal persistence, and attentional control. Respondents indicated their agreement with each statement using a five-point Likert scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). Prior studies have demonstrated satisfactory psychometric performance of this scale, including high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.83) and adequate test–retest reliability across adolescent samples in China46.

Mental health

Mental health status was evaluated using a 25-item scale developed by Su et al.47, specifically designed to capture the emotional and psychological adjustment of Chinese adolescents. The scale comprises five subdomains: life satisfaction, academic motivation, interpersonal functioning, emotional stability during examinations, and general emotional well-being. Each item is rated on a five-point scale reflecting the frequency or intensity of the respective experiences. Previous validation research has confirmed the internal consistency of the scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.83), as well as its factorial validity and suitability for large-scale educational or psychological assessments in youth populations48.

Data analysis procedure

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 26.0. To evaluate the potential impact of common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was performed using exploratory factor analysis, with the threshold for concern set at 40% of total variance explained by the first unrotated factor49. Descriptive statistics were computed to assess central tendencies and variability of key variables, while Cronbach’s α was used to assess internal consistency reliability, with coefficients above 0.70 considered acceptable50. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the strength and direction of bivariate associations, with coefficients of 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 interpreted as small, moderate, and large effects, respectively51. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted to evaluate the construct validity of models, using conventional model fit indices including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Acceptable model fit was defined as CFI and TLI greater than 0.90, SRMR less than 0.06, and RMSEA less than 0.0852,53. Longitudinal confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess measurement invariance across time, sequentially testing configural, metric, and scalar models. Invariance was evaluated based on changes in model fit indices, with ΔCFI less than 0.010 and ΔTLI less than 0.010 indicating acceptable invariance at each level54. The main structural analysis employed a three-wave cross-lagged panel model, estimated using maximum likelihood in AMOS. This model allowed for the simultaneous estimation of autoregressive and cross-lagged paths among sport participation, self-control ability, and mental health, thereby identifying the temporal directionality of relationships across time points55. Multi-group confirmatory factor analyses were additionally conducted to examine the structural invariance of the model across demographic groups defined by gender, school stage, residence type, and sport type. Model comparisons relied on absolute and incremental fit indices including χ2/df, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR, with a change of less than 0.01 in CFI or TLI considered indicative of invariance across groups56.

Result

Common method bias

The result of Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the first unrotated factor accounted for 32.49% of the total variance, which falls below the recommended threshold of 40% and suggests that common method bias is unlikely to be a major concern.

Descriptive statistics and psychometric properties

Table 3 summarizes the descriptive statistics, internal consistency coefficients, and psychometric fit indices for the three study constructs across all waves. Cronbach’s α coefficients ranged from 0.835 to 0.935, exceeding the conventional reliability threshold of 0.80. CFA conducted for self-control and mental health across the three time points indicated consistently acceptable model fit, with CFI and TLI values above 0.96, RMSEA ranging from 0.059 to 0.083, and SRMR values between 0.017 and 0.025. These results support the internal consistency and structural validity of the two latent constructs. The composite sport participation measure was excluded from CFA due to its formative scoring structure57.

Correlation analysis

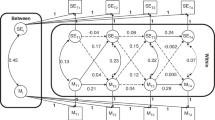

Figure 2 presents the Pearson’s correlations among sport participation, self-control ability, and mental health across all three time points. All associations were positive and statistically significant (p < 0.001). At Time 1, sport participation was moderately correlated with self-control ability (r = 0.38) and mental health (r = 0.39), while self-control and mental health showed a stronger correlation (r = 0.48). At Time 2, the correlation between sport participation and self-control increased to r = 0.44, with mental health remaining at r = 0.39; the correlation between self-control and mental health was notably strong (r = 0.62). At Time 3, sport participation was correlated with self-control ability at r = 0.42 and with mental health at r = 0.32, while the correlation between self-control ability and mental health was r = 0.47. These results indicate consistent positive relationships among the three constructs across time.

Cross-sectional measurement models

As shown in Table 4, all models demonstrated good fit, with χ2/df values of 2.749 (Time 1), 3.540 (Time 2), and 3.250 (Time 3). The CFI ranged from 0.978 to 0.985, and the TLI ranged from 0.976 to 0.983, both exceeding 0.90. The SRMR was consistently 0.019, and RMSEA values ranged from 0.037 to 0.044, all within acceptable thresholds. These results indicate that the measurement models at each wave were psychometrically sound.

Multi-group invariance test for the measurement model across time points

Table 5 summarizes model fit indices for measurement invariance testing across three time points. The configural model demonstrated adequate fit (χ2/df = 3.390, CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.977, SRMR = 0.018, RMSEA = 0.025), indicating a consistent factorial structure. When factor loadings were constrained to equality, model fit remained stable (ΔCFI = 0.000, ΔTLI = 0.001). Further constraints on item intercepts yielded similarly acceptable changes (ΔCFI = − 0.003, ΔTLI = 0.000). These results indicate that both metric and scalar invariance were established across waves.

Cross-lagged panel model

The initial model, which included all theoretically hypothesized paths, showed good fit to the data (χ2/df = 1.708, CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.994, SRMR = 0.011, RMSEA = 0.023). However, four cross-lagged paths were not statistically significant: self-control at Time 1 did not predict sport participation at Time 2 (β = 0.007, p = 0.802); mental health at Time 1 did not predict sport participation at Time 2 (β = 0.033, p = 0.254); self-control at Time 2 did not predict sport participation at Time 3 (β = − 0.020, p = 0.562); and mental health at Time 2 did not predict sport participation at Time 3 (β = 0.007, p = 0.836). These results indicated a lack of support for H3 and H6. A revised model was subsequently tested with the non-significant paths removed, yielding improved fit indices (χ2/df = 1.352, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.997, SRMR = 0.014, RMSEA = 0.016). Full model fit comparisons are presented in Table 6.

In the refined model, autoregressive paths were all statistically significant (p < 0.05) and stable across waves, sport participation (β = 0.44 from T1 to T2; β = 0.35 from T2 to T3), self-control ability (β = 0.33; β = 0.34), and mental health (β = 0.31; β = 0.24). All cross-lagged paths retained in the model also reached statistical significance (p < 0.05), sport participation at Time 1 predicted self-control (β = 0.18) and mental health (β = 0.25) at Time 2, and sport participation at Time 2 continued to influence self-control (β = 0.12) and mental health (β = 0.08) at Time 3, supporting H1 and H2. Self-control ability predicted subsequent mental health across both waves (β = 0.30 from T1 to T2; β = 0.17 from T2 to T3), supporting H4. Mental health significantly predicted subsequent self-control ability across two consecutive waves, with Time 1 mental health predicting Time 2 self-control (β = 0.23), and Time 2 mental health predicting Time 3 self-control (β = 0.23), providing evidence for H7. Additionally, an indirect pathway from sport participation at Time 1 to mental health at Time 3 via self-control at Time 2 was identified, consistent with H5. Standardized coefficients are displayed in Fig. 3.

Cross-lagged model of sport participation, self-control ability and mental health. SP = sport participation, SCA = self-control ability, MH = mental health. “e” represents the error terms associated with each construct. To improve model clarity, the coefficients for “e” are not shown in the figure. All path coefficients in this figure are standardized path coefficients.

Multi-group invariance test for the structural model

Model fit indices across gender, school stage, residence type, and sport type are presented in Table 7. Across all demographic comparisons, the CFI and TLI values consistently exceeded 0.90, RMSEA remained below 0.08, and SRMR was under 0.06. Differences in CFI and TLI between nested models were within the accepted threshold of 0.01, indicating that the structural paths did not differ meaningfully across groups. These results support the invariance of structural relations among sport participation, self-control ability, and mental health across demographic subgroups.

Discussion

Key findings and interpretations

This study provides robust longitudinal evidence supporting the role of sport participation as a foundational behavioral context within which adolescents’ self-control ability and mental health are mutually reinforced over time. The cross-lagged analyses clearly indicated that earlier sport participation significantly predicted later improvements in both self-control and mental health, consistent with fundamental propositions of SDT12. According to SDT, structured sport environments inherently facilitate adolescents’ internalization of self-regulatory competencies by satisfying their basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Specifically, autonomy-supportive contexts enable adolescents to experience behavioral choices aligned with intrinsic motivations, competence-supportive structures provide repeated mastery experiences, and socially connected environments fulfill relatedness needs. Together, these mechanisms enhance adolescents’ internal psychological resources, enabling effective self-regulation, emotional integration, and consequently, better psychological health.

Further supporting this theoretical perspective, the results identified a clear mediational pathway through which the positive effect of sport participation on mental health operated indirectly via self-control. This finding aligns with neurodevelopmental frameworks that posit adolescence as a critical period for prefrontal cortex maturation, underpinning the consolidation of executive functions and emotional regulation capacities. Previous neuropsychological studies have demonstrated that sustained sport engagement facilitates structural and functional enhancements in brain regions associated with self-regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex58,59,60,61. Thus, the mediating role of self-control observed in the current longitudinal study substantiates and extends existing neurocognitive evidence, highlighting sport participation as a vital experiential scaffold through which adolescents acquire durable self-regulatory capabilities, subsequently enhancing emotional stability and psychological resilience.

Another notable finding was the reciprocal predictive relationship between self-control and mental health observed across subsequent waves. This bidirectional association provides empirical substantiation for developmental cascade models proposed within PYD theory, emphasizing reciprocal influences between adaptive psychological competencies and emotional well-being14. Adolescents with enhanced self-control capacities are better equipped to regulate emotions, manage stress, and maintain adaptive social relationships, thus protecting against psychological maladjustment24,25. Conversely, stable mental health status provides the cognitive-emotional resources necessary to sustain effective self-regulation over time, creating a self-reinforcing adaptive system. The reciprocal interaction between self-control and mental health thus embodies the essence of PYD’s “developmental assets” framework, whereby initial strengths in one domain catalyze sustained developmental gains across multiple psychological dimensions.

Importantly, the absence of significant paths from self-control and mental health back to subsequent sport participation raises important theoretical considerations. This result challenges simple bidirectional assumptions and instead underscores the asymmetry between psychological resources and behavioral engagement in sport. A plausible theoretical explanation, grounded in ecological systems theory, is that while psychological resources can sustain participation once initiated, behavioral initiation itself is predominantly shaped by external contextual factors rather than internal psychological states alone62,63. Institutional access, peer norms, and cultural expectations are likely critical determinants in the initial adoption and maintenance of sport engagement, highlighting the need for structural and systemic approaches to promoting adolescent physical activity.

Moreover, multi-group invariance tests revealed stable structural relationships across diverse demographic subgroups (gender, school stage, residence type, and sport type). This structural invariance provides important evidence for the generalizability and theoretical robustness of the identified developmental pathways. From a practical standpoint, such population-level consistency suggests broad applicability of intervention strategies informed by SDT and PYD frameworks. Nevertheless, while structural invariance demonstrates theoretical consistency, it should not obscure the nuanced contextual dynamics influencing adolescents’ actual engagement with sport. Previous studies indicate substantial contextual variability shaped by factors such as resource accessibility, cultural attitudes towards sport, academic pressures, and social norms related to gender and residence contexts64,65,66. Thus, future interventions must balance fidelity to these general developmental mechanisms with adaptability to specific contextual factors, ensuring that health-promotive efforts remain both theoretically grounded and contextually relevant.

Educational implications

The temporal ordering observed in this study, in which sport participation predicts improvements in self-control followed by gains in mental health, positions structured physical activity as an upstream determinant that schools can deliberately mobilise to promote psychological development. To translate this evidence into practice, physical-education curricula should be redesigned around progressive learning trajectories that integrate explicit self-regulatory goals. Lesson sequences can begin with instructor-guided goal identification and simple monitoring routines, advance toward student-led planning and reflection, and culminate in peer-supported projects that require sustained collaboration under emotionally demanding conditions. Such sequencing treats sport settings as developmental micro-contexts in which students rehearse attention shifting, delay of gratification, and emotion differentiation. To sustain these processes beyond discrete class periods, schools can embed “reflection loops” in which students briefly document regulatory strategies used during activity, link those strategies to emotional outcomes, and revisit the records in subsequent sessions. Teacher preparation therefore needs to encompass motivational climate design, feedback techniques centred on autonomy support, and formative assessment of regulatory behaviours, complementing traditional skill-instruction competencies67,68.

System-level implementation demands alignment among scheduling, facilities, and data infrastructure. Multi-semester physical-activity pathways should be protected in timetables to create cumulative exposure; facilities must remain accessible before and after the school day to reinforce habit formation; and low-burden monitoring tools (for example, periodic self-report check-ins combined with wearable-device step counts) can supply iterative evidence for programme adjustment. Because the structural model proved invariant across gender, educational stage, residence type, and preferred sport, the core intervention logic appears transferable. Nonetheless, resource disparities and culturally specific valuations of sport require local adaptation. Schools in resource-constrained areas may prioritise low-equipment activities and partner with community organisations for space and coaching; academically intensive settings may integrate brief, high-frequency activity bouts within classroom transitions to mitigate opportunity costs. Embedding mental-health literacy modules within sport programmes can further ensure that emotional challenges encountered during strenuous activity are framed as occasions for skill acquisition rather than indicators of weakness. Such context-sensitive design applies the universal developmental mechanism identified here while attending to the heterogeneous constraints and affordances that shape adolescents’ daily experience69,70.

Limitations and directions for future research

Although the three-wave design strengthens temporal inference, several limitations temper the conclusions and shape priorities for future work. First, reliance on self-report introduces measurement bias, particularly for sport participation; upcoming studies should incorporate objective indices such as accelerometry or wearable trackers to improve accuracy71. Second, the observational design clarifies temporal ordering but cannot establish causality, underscoring the value of randomised or quasi-experimental trials that manipulate physical-activity exposure and self-regulation training. Third, the sample is nationally diverse yet culturally homogeneous, so replications across socioeconomic strata and international contexts are needed to test the boundary conditions of the reported pathways. Finally, the present study did not include neurobiological, cognitive, or social-environmental indicators, limiting insight into the mechanisms through which sport participation shapes self-control and mental health; integrating multimodal measures in future research would address this gap and support the development of more precise intervention strategies.

Conclusion

The present study offers longitudinal evidence that sport participation serves as a significant predictor of subsequent improvements in self-control ability and mental health among adolescents. Cross-lagged associations and mediation analyses support a developmental pathway in which sport engagement facilitates psychological adjustment, partly through enhanced self-regulatory capacity. The findings align with the theoretical premises of self-determination theory and positive youth development, and structural invariance across demographic groups suggests that the identified pathways are stable across gender, school stage, residence type, and sport type. These results contribute to ongoing efforts to clarify the psychological mechanisms linking physical activity to adolescent well-being and provide a foundation for future studies employing experimental designs, objective activity assessments, and multimodal indicators to further advance this area of research.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because this is part of a series of ongoing studies. However, data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Best, O. & Ban, S. Adolescence: physical changes and neurological development. Br. J. Nurs. 30(5), 272–275. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.5.272 (2021).

Josefsson, T., Lindwall, M. & Archer, T. Exercise intervention in depressive disorders. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 24, 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12050 (2014).

Chin A Paw, M. J., van Uffelen, J. G., Riphagen, I. & van Mechelen, W. The functional effects of physical exercise training in frail older people: a systematic review. Sports Med. (Auckland N Z). 38(9), 781–793. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200838090-00006 (2008).

de Vries, N. M. et al. Effects of physical exercise therapy on mobility, physical functioning, physical activity and quality of life in community-dwelling older adults with impaired mobility, physical disability and/or multi-morbidity: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 11(1), 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2011.11.002 (2012).

Mahindru, A., Patil, P. S. & Agrawal, V. Role of physical activity on mental health and well-being: A review. Cureus 15(5), e33475. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.33475 (2023).

Liu, Y., Feng, Q. & Tong, Y. Physical exercise and college students’ mental health: Chain mediating effects of social–emotional competency and peer relationships. Social Behav. Personality: Int. J. 52(7). https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.13159 (2024).

Shantakumar, S., Sahabdeen, H., Abidin, F., Perumal, G. & Kumar, N. Association of type and duration of exercise with the mental and physical health and academic performance of medical undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study. Bangladesh J. Med. Sci. 21(1), 135–139. https://doi.org/10.3329/bjms.v21i1.56339 (2022).

Guo, Z. & Zhang, Y. Study on the interactive factors between physical exercise and mental health promotion of teenagers. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 4750133. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4750133 (2022).

Vohs, K. D., Baumeister, R. F. & Schmeichel, B. J. Motivation, personal beliefs, and limited resources all contribute to self-control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48(4), 943–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.03.002 (2012).

Schöndube, A., Bertrams, A., Sudeck, G. & Fuchs, R. Self-control strength and physical exercise: an ecological momentary assessment study. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 29, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.11.006 (2017).

Şimşir Gökalp, Z. Examining the association between self-control and mental health among adolescents: the mediating role of resilience. School Psychol. Int. 44(6), 649–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343231182392 (2023).

Ten Cate, T. J., Kusurkar, R. A. & Williams, G. C. How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. AMEE Guide 59 Med. Teacher. 33(12), 961–973. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.595435 (2011).

Wilson, P. M., Mack, D. E. & Grattan, K. P. Understanding motivation for exercise: A self-determination theory perspective. Can. Psychol. / Psychologie Canadienne. 49(3), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012762 (2008).

Balsano, A. B., Phelps, E., Theokas, C., Lerner, J. V. & Lerner, R. M. Patterns of early adolescents’ participation in youth development programs having positive youth development goals. J. Res. Adolescence. 19, 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00595.x (2009).

Hoyt, L. T., Chase-Lansdale, P. L., McDade, T. W. & Adam, E. K. Positive youth, healthy adults: does positive well-being in adolescence predict better perceived health and fewer risky health behaviors in young adulthood? J. Adolesc. Health: Official Publication Soc. Adolesc. Med. 50(1), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.002 (2012).

Weiss, M. R., Kipp, L. E., Phillips Reichter, A., Espinoza, S. M. & Bolter, N. D. Girls on the run: impact of a physical activity youth development program on psychosocial and behavioral outcomes. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 31(3), 330–340. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.2018-0168 (2019).

Salmon, P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 21(1), 33–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00032-X (2001).

Ludyga, S. et al. Effects of cognitive and physical load of acute exercise on inhibitory control and prefrontal cortex hemodynamics in children. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc. 56(7), 1328–1336. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000003410 (2024).

Martinez, V. M. & Martins, M. D. Neurobiological Origins of Impulsive Behavior in Adolescence: Possibilities of Physical Exercise (Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 2024).

Wang, J. et al. Association between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity trajectories and academic achievement in Chinese primary school children: a 3-year longitudinal study. BMC Public. Health. 25(1), 341. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-21487-z (2025).

Koh, S. H. Analyzing the influence of physical exercise interventions on social skills in children with autism spectrum disorder: insights from meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 15, 1399902. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1399902 (2024).

Marqués-Sánchez, P., Benítez-Andrades, J. A., Calvo Sánchez, M. D. & Arias, N. The socialisation of the adolescent who carries out team sports: a transversal study of centrality with a social network analysis. BMJ Open. 11(3), e042773. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042773 (2021).

Tsukayama, E., Toomey, S. L., Faith, M. S. & Duckworth, A. L. Self-control as a protective factor against overweight status in the transition from childhood to adolescence. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 164(7), 631–635. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.97 (2010).

MacLean, E. L. et al. The evolution of self-control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111(20), E2140–E2148. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1323533111 (2014).

Kumar, S. & Sharma, A. Association between self-control and emotional maturity among adolescents. Int. J. Social Sci. Res. Rev. 7(6), 758–760 (2019).

Casanova, J., Sinval, J. & Almeida, L. Academic success, engagement and self-efficacy of first-year university students: personal variables and first-semester performance. Anales De Psicología. 40(1), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.479151 (2024).

Camp, N. et al. It is not just a matter of motivation: the role of Self-Control in promoting physical activity in older Adults—A. Bayesian Mediation Model. Healthc. 12(16), 1663. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161663 (2024).

Postrel, S. & Rumelt, R. P. Incentives, routines and Self-Command. In: (eds Dosi, G. & Malerba, F.) Organization and Strategy in the Evolution of the Enterprise. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-13389-5_4 (1996).

Wills, T. A., Walker, C., Mendoza, D. & Ainette, M. G. Behavioral and emotional self-control: relations to substance use in samples of middle and high school students. Psychol. Addict. Behaviors: J. Soc. Psychologists Addict. Behav. 20(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.265 (2006).

Mota, C. P., Mateus, D., Relva, I. C. & Costa, M. Peer attachment and self-control: implication on social anxiety in young adults. Social Sci. 13(9), 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090445 (2024).

Şimşir, Z. Examining the association between self-control and mental health among adolescents: the mediating role of resilience. School Psychol. Int. 44(5), 439–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343231182392 (2023).

Wei, X. et al. The effect of physical activity on depression in university students: the mediating role of self-esteem and positive psychological capital. Front. Psychol. 15, 1485641. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1485641 (2024).

Belcher, B. R. et al. The roles of physical activity, exercise, and fitness in promoting resilience during adolescence: effects on mental Well-Being and brain development. Biological psychiatry. Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 6(2), 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.08.005 (2021).

McLaren, C. D., Shanmugaratnam, A. & Bruner, M. W. Peer-initiated motivational climate, mental health and adherence in competitive youth sport. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coaching. 19(2), 851–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541231179879 (2023).

Williams, C. R., McKenna, J. L., Artessa, L. & Moore, L. B. M. Team effort: A call for mental health clinicians to support sports access for transgender and gender diverse youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 62(8), 837–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2023.01.022 (2023).

Li, W., Wang, J., Zu, J. & Li, C. An analysis of cross-lagged on the relationship between social anxiety, self-control and loneliness of primary school students. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 40(5), 687–694. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2024.05.09 (2024).

Li, W. & Lu, J. The impact of school physical exercise on negative emotions in junior high school students: an empirical analysis based on CEPS data. J. Shenyang Sport Univ. 42(1), 29–35 (2023). https://link.cnki.net/urlid/21.1081.G8.20230109.1047.002

Yu, L., Xia, J. & Zhang, W. The effect of exercise intervention on the mental health and self-efficacy of students with weak physiques. J. Wuhan Sports Univ. 47(8), 73–76. https://doi.org/10.15930/j.cnki.wtxb.2013.08.014 (2013).

Zhang, Y. & Zhang, L. Research progress on the classification of self-control training for athletes. Chin. J. Sports Med. 36(10), 910–914. https://doi.org/10.16038/j.1000-6710.2017.10.014 (2017).

Chen, Z. & Wu, H. Intrinsic motivation and its antecedent variables. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 16(1), 98–105 (2008).

Duckworth, A. L. & Yeager, D. S. Measurement matters: assessing personal qualities other than cognitive ability for educational purposes. Educational Researcher. 44(4), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X15584327 (2015).

Faden, V. B. et al. Collecting longitudinal data through childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood: methodological challenges. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 28(2), 330–340. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.alc.0000113411.33088.fe (2004).

Liang, D. Stress levels of college students and their relationship with physical exercise. Chin. J. Mental Health. 1, 5–6 (1994).

Dong, Y., Wang, X. & Yuan, W. & others. The impact of physical exercise on school bullying among middle school students: A chain mediation effect of psychological capital and self-control. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 31(5), 733–739. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2023.05.018 (2023).

Luo, T., Cheng, L. & Qin, L. & others. Reliability and validity testing of the Chinese version of the Brief Self-Control Scale. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 29(1), 83–86. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.01.017 (2021).

Wu, M., Chen, D. & Yan, M. & others. The relationship between family rituals and adolescents’ self-control: A chain mediation effect of parent-child attachment and the sense of life meaning. Psychol. Behav. Res. 21(6), 832–838 (2023).

Su, D. & Huang, X. Initial exploration of the structure of psychological health in adolescents with an adaptation orientation. Psychol. Sci.(6), 1290–1294 (2007).

Liu, Y., Liu, J. & Zhang, K. & others. The relationship between academic attribution styles, academic emotions, and mental health in middle school students. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 22(5), 760–763. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2014.05.048 (2014).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 (2003).

Adamson, K. A. & Prion, S. Reliability: measuring internal consistency using cronbach’s α. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 9(5), e179–e180 (2013).

Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1(3), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783 (1992).

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999).

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J. & Mullen, M. Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods. 6(1), 53–60 (2008).

Cheung, G. W. & Rensvold, R. B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 (2002).

Keith, T. Z. Multiple Regression and Beyond: An Introduction to Multiple Regression and Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315162348 (Routledge, 2019).

Byrne, B. M. Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: A road less traveled. Struct. Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 11(2), 272–300. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1102_8 (2004).

McDonald, R. P. & Ho, M. H. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods. 7(1), 64–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64 (2002).

Matta Mello Portugal, E. et al. Neuroscience of exercise: from neurobiology mechanisms to mental health. Neuropsychobiology 68(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1159/000350946 (2013).

Schmahl, T., Steinhäuser, J. & Goetz, K. Association between orthodontic treatment and psychosocial factors in adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Orthod. 47(1), cjae082. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjae082 (2024).

Kita, I. Physical exercise can induce brain plasticity and regulate mental function. Adv. Exerc. Sports Physiol. (2014).

Meijer, A., Verburgh, L. & Hartman, E. The effects of physical exercise on the brain and neurocognitive functioning during childhood. In Exercise to Prevent and Manage Chronic Disease Across the Lifespan (eds Feehan, J. et al.) 65–71 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-89843-0.00011-8 (Elsevier, 2022).

Dobbins, M., Husson, H., DeCorby, K. & LaRocca, R. L. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Dtabase Syst. Rev. 2013(2), CD007651 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007651.pub2 (2013).

Pate, R. R., O’Neill, J. R. & McIver, K. L. Physical activity and health: does physical education matter? Quest. 63(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2011.10483660 (2011).

Zhang, P. et al. Assessment of factors associated with mental well-being among Chinese youths at individual, school, and Province levels. JAMA Netw. Open. 6(7), e2324025. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.24025 (2023).

Wang, H. & Feng, T. Academic stress and mental health in adolescents: A retrospective analysis, influence mechanisms, and coping strategies. People’s Educ. 9, 16–21 (2024).

Rodrigues, L., Safeekh, A. T. & Veigas, J. Mental well-being among adolescents: A cross-sectional survey. J. Health Allied Sci. NU. 14(4), 271–276. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1771384 (2023).

Lewin-Bizan, S., Bowers, E. P. & Lerner, R. M. One good thing leads to another: cascades of positive youth development among American adolescents. Dev. Psychopathol. 22(4), 759–770. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000441 (2010).

Dobbins, M., De Corby, K., Robeson, P., Husson, H. & Tirilis, D. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6–18. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (1), CD007651. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007651 (2009).

Pérez-Ramírez, J. A., González-Fernández, F. T. & Villa-González, E. Effect of school-based endurance and strength exercise interventions in improving body composition, physical fitness and cognitive functions in adolescents. Appl. Sci. 14(20), 9200. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14209200 (2024).

Dishman, R. K. et al. Self-efficacy partially mediates the effect of a school-based physical-activity intervention among adolescent girls. Prev. Med. 38(5), 628–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.007 (2004).

Sallis, J. F. & Saelens, B. E. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 71(sup2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2000.11082780 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants and their families for their cooperation and support throughout this study. We also extend our gratitude to the School of Sports Training at Chengdu Sport University and the School of Leisure and Sports at Chengdu Gingko College of Hospitality Management for their resources and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.C. and B.P. contributed to the study conceptualization, methodology, and data collection. W.C. and L.Y. performed data analysis and interpretation. W.C. and L.L. wrote the original draft, with contributions from B.P. and L.Y. H.H. and L.L. revised the manuscript based on reviewer feedback, with additional input from W.C. L.L. supervised the project and served as the corresponding author. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, W., Peng, B., Hu, H. et al. A study on the cross-lagged relationships between adolescents’ sport participation and self-control ability and mental health. Sci Rep 15, 35497 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19457-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19457-x