Abstract

Understanding of Southern Hemisphere glacier response to climatic changes is limited by a paucity of direct observations. However, glacier Equilibrium Line Altitudes (ELAs), which are determined by air temperature and precipitation and represent glacier mass balance, can be approximated using remote sensing of end of summer snowline altitudes (SLAEOS). This study shows that SLAEOS increased on the majority of 6364 glaciers and by up to 7.18 m yr−1 between 2000 and 2023 across five Southern Hemisphere mountain regions. Over this period anomalies from the multi-decadal mean SLAEOS became predominantly positive for all regions. In the most extreme cases, the rate of SLAEOS rise accelerated by up to x 4.0 in the western Southern Alps of New Zealand when comparing pre- and post-2010 rates of change. Contrastingly, the western Antarctic Peninsula and the western Southern Andes experienced declining SLAEOS and slowing rates of change at -1.0 and − 8.1 m yr−1, respectively. These spatio-temporal patterns reveal the interplay of temperature and precipitation, and the effects of them on a wide variety of mountain glaciers and ice cap outlet glaciers, with implications for understanding glacier response times, committed ice losses and overall meltwater production in the coming decades.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Just 10% of glaciers with direct mass balance monitoring are located within the Southern Hemisphere1. Understanding of Southern Hemisphere glacier response to climatic changes is therefore lacking spatio-temporal coverage, and more specifically, inter-annual and seasonal changes of glacier mass balance remain poorly quantified2. Remote sensing geodetic mass balance methods have revealed widespread glacier mass loss3 but have also highlighted considerable spatial and temporal variability in patterns and rates. An alternative solution for evaluating glacier response is to use annual end-of-summer snowline altitudes (SLAEOS) as a proxy for the glacier Equilibrium Line Altitude (ELA) and thus long-term glacier mass balance4,5,6,7. SLAEOS can be defined as the lowest elevation on a glacier where snow cover remains at the end of a summer season (Fig. 1). Annual SLAEOS depends directly on air temperature and precipitation and more specifically on the surface energy balance, which is composed of turbulent heat fluxes; sensible heat due to temperature changes, latent heat due to phase changes e.g. solid to liquid for melting, and radiation fluxes; dominated by shortwave incoming radiation. SLAEOS can either be retrieved from glacier mass balance monitoring, or automatically from satellite images. However, there are only seventy glaciers in the world with long-term ELA records8 and just seven of them are located in the Southern Hemisphere. There is therefore a research gap for developing automatic retrieval of annual snowline altitudes from satellite images to determine the ELA of Southern Hemisphere glaciers. The aim of this study is to determine spatial patterns and temporal trends of SLAEOS for thousands of glaciers across the Southern Hemisphere from 2000 to 2023.

Study area

Our study encompasses mountain regions across the Southern Hemisphere, namely; Southern Alps of New Zealand, Antarctic Peninsula, Central Andes, Central Chilean Andes and the Southern Andes. These regions are split between east and west to recognise major morpho-climatic zones (Fig. SI_1).

Methodology to gain spatio-temporally resolved end of summer snowline altitudes (SLAEOS)

This study developed a novel approach using Google Earth Engine (GEE) to retrieve, filter and analyse satellite images to firstly classify snow cover versus bare ice, and to then derive the elevation of the boundary between those parts for multiple glaciers for multiple years. Our approach enables coverage of thousands of glaciers across multiple world regions and spanning several decades. Specifically, the workflow of Li et al.11 was expanded to gain SLAEOS values across a sequence of years for multiple glaciers simultaneously. Our workflow was entirely within Google Earth Engine and includes image and elevation data processing, snow classification and SLAEOS identification, was in GEE (Fig. SI_2), and iterated across a list of years and a list of glaciers. Our datasets are described in our Table SI_1).

Near-annual SLAEOS values were retrieved for 6364 glaciers across the Southern Hemisphere between 1 st January 2000 and 31 st December 2023 and at 30 m horizontal resolution (Fig. 1, Table SI_2). Our results are presented in a conservative manner, only including glaciers with ten or more observations of annual SLAEOS and combining glaciers in both spatially-aggregated and temporally-averaged forms, thereby mitigating locally-specific glaciological or topographic controls, uncertainty in the end-of-summer timing, and inter-annual variability, for example. Overall, major spatial patterns and temporal trends are discerned in Southern Hemisphere SLAEOS that are associated with climate change. Inter- and intra-region spatial variability and temporal trends are examined for the full study period 2000 to 2023, as well as for sub-periods 2000 to 2010 and 2011 to 2023.

Image and elevation data processing

Landsat collections were filtered to the period 2000 to 2023 and to the end-of-summer timeframe for each region. For the Andes and Southern Alps, previous studies support the timeframe of mid-February to early-April12. For the Antarctic Peninsula, annual peak snow melt has been documented in January13. Therefore, SLAEOS values reported in this study are the maximum of all SLAs retrieved from all available images between 01/02 and 30/04 for the Andes and Southern Alps, and between 01/01 and 30/04 for the Antarctic Peninsula, to allow for fluctuations in the timing of maximum SLA between years. East African and Indonesian glaciers are too small and too few to yield statistically robust spatial patterns or temporal trends and so are omitted from our study.

Filtering Landsat images were filtered to retain only those images with < 50% cloud cover. Images were then clipped to each glacier outline and the C Function of Mask (CFMask) algorithm was applied to mask any cloud-covered pixels that could have a similar reflectance to snow. Erroneous pixels (usually with a value > 65535) were also masked. The valid pixel ratio of every image for a given glacier was calculated, and only images with > 65% visible pixels remaining following cloud masking were retained for further analysis11. This step also minimised the effect of Landsat 7 scan line corrector error that created tracks of invalid image pixels over some glaciers.

The AW3D30 v. 3.1 Digital Elevation Model (DEM), which is a mosaic dataset composed of data from 2006 to 2011 and with a median date of 2009, was static (unchanged) throughout our study and workflow, enabling direct comparison of SLAs obtained for each year per glacier. Functions were run to calculate the minimum and maximum elevation of individual glaciers, and to generate a List sequence of contour elevations between these values at 20 m intervals.

Snow classification

Images in our filtered collection were individually processed to detect snow-covered parts of glaciers. Each image was topographically corrected by sun-canopy-sensor correction, SCS + C15 using GEE-based code adapted from top-of-atmosphere topographic correction methods15 and surface reflectance topographic correction methods16. Topographic correction reduces underestimation of snow-covered pixels caused by topographic shadow17 and the SCS + C method is well-supported by previous studies, which encourage its use for mountainous environments18,19. Although part of image preparation, topographic correction took place at this stage of our workflow for efficiency (versus correcting entire image collections simultaneously).

As the use of different band ratios, NDSI and NIRSWIR, currently divides automated snowline analyses20,21 annual mean SLAEOS was initially calculated in this study using both NDSI and NIRSWIR ratios and compared them to those collected by the New Zealand aerial survey10 (Fig. SI_10). SLAEOS results from the NIRSWIR approach showed a weak positive correlation with aerial survey results (r = 0.19), while results from the NDSI approach showed moderate negative correlation (r = −0.44). Although aerial survey data cannot necessarily be treated as ground-truth due to the uncertainty introduced with converting the snowline viewed on an oblique image to an elevation, this study chose to use the NIRSWIR Otsu method, interpreting the problems the NIRSWIR for each glacier image by using bands 4 and 5 in Landsat 4 TM/5 TM/7 ETM+, and bands 5 and 6 in Landsat 8 OLI.

The Otsu method21 of binary image segmentation was applied to classify the image into ‘snow’ and ‘ice’ pixels using a histogram from the NIRSWIR. This statistical algorithm identifies glacier-specific classification thresholds, by identifying the maximum between-class variance, corresponding to the maximum between-sum-of-squares of pixel values in each of our filtered images (Fig. SI_3). Otsu has been applied in several automated snowline detection studies e.g23. as it is favoured over manual and semi-automated methods for adaptively identifying snow-ice boundaries over large numbers of clipped images6,7,23. Clipping images to glacier outlines was necessary because this method assumes each image contains only snow and ice pixels so if other light-absorbing land cover types (e.g., rock or vegetation) are erroneously contained within the glacier area, they will likely be classified as ‘ice’ and cause a shift in the Otsu threshold value.

SLAEOS identification

Topographic and climatic factors can cause hollows, shadows, avalanche deposits and wind-blown snow to create perforated snow cover in the vicinity of a glacier snowline, so that the snowline may be non-continuous and span a range of altitudes6. Consequently, the World Meteorological Organisation recommends that SLAEOS be represented as an altitudinal zone rather than a specific altitude. The classified glacier image was then separated into 20 m elevation bins using the list of contours created in data preparation, and the snow cover ratio (SCR) of each bin was calculated from its ‘snow’ and ‘ice’ pixel counts.

A function was then applied to identify the lowermost set of 5 consecutive elevation bins which each had SCR > 0.5 (snow coverage > 50%). If a set was identified, SLAEOS was taken as the average elevation of the lowest bin in that set. If unidentified, the required number of bins in a set was reduced by 1, until the condition for SCR was met. If no elevation bin with SCR > 0.5 was identified, SLAEOS was returned as a null value. When there were multiple usable images for a glacier in a given year, multiple SLAEOS values were produced. In this case, the maximum SLAEOS value was taken. When only one SLAEOS value was produced it was not recorded, meaning that every SLAEOS result used in this study is a maximum SLAEOS compared to at least one other SLAEOS result for that glacier and that year. Temporal trends were identified with a best-fit linear regression through the annual regional and sub-regional SLAEOS values. The significance of that trend was assessed with a t-test on the slope coefficient (whether it being different to zero).

Accuracy and uncertainty

Our remotely-sensed observations are evaluated in three independent ways. Firstly, our SLAEOS are compared to the aerial survey dataset of annual SLAEOS of ~ 50 glaciers across the Southern Alps5,9,10 (SI).

Secondly, our SLAEOS are compared to ELAs calculated from direct mass balance measurements on the 6 reference glaciers in the Southern Hemisphere (Table SI_3). The latter a yielded positive correlation (r2 = 0.76) between our sub-regional median rate of SLAEOS change and change in ELA. Martial Este Glacier in the Southern Andes is not well-represented by the regression line, and as it is a strongly maritime glacier it could be considered as an anomaly and if it is removed then the correlation increases to r2 = 0.95 (Fig. SI_12).

Thirdly, random point assessments were made for each sub-region, selecting glaciers with a range of aspects and assessing uncertainty for two separate years. Both Landsat 7 ETM + and Landsat 8 OLI were represented. Each assessment comprised 100 points (per clipped image; Fig. SI_4) classified visually and manually into snow, ice, and N/A (blank image) groups, by interpretation of false-colour images (bands 5, 4, and 3 for Landsat 5TM/7ETM+, and bands 6, 5, and 4 for Landsat 8 OLI), and consideration of the likely locations of accumulation and ablation zones (Fig. SI_4). These interpretations were then compared to our automatic SLAEOS classifications to calculate percentage uncertainty. The mean accuracy of snow classification was 87.4 ± 6.2% across all regions and all years assessed. Landsat 7 ETM + images increased the number of N/A validation points due to gaps associated with scan Line error, but uncertainty did not vary between cases where Landsat 7 ETM + images were present (87.5%) and cases where only Landsat 8 OLI images were present (87.2%). Overall, our estimated mean accuracy of snow classification was 87.4% across all regions and all years. An uncertainty was assigned to each median SLAEOS (per year, per sub-region) of one standard deviation.

Uncertainty varied more strongly between regions and particularly across the four Andean regions, with the Central Chilean region displaying highest (93.9%) snow classification accuracy (Fig. SI_5). This outcome could be expected due to regional differences in cloud cover27 (Fig. SI_6), which made for increased image clarity in the Central Chilean region. We noted the problems introduced by bush fire ash and topographic shading on our classifications, for example (Fig. SI_7).

Sources of uncertainty within our automated SLAEOS calculation arise from (i) vertical accuracy of elevation data, (ii) accuracy of satellite images used in glacier outline generation and snowline analysis, and (iii) accuracy of the SLAEOS identification method. Assuming that the uncertainty sources are uncorrelated, SLAEOS uncertainty was calculated as the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of the sum of the uncertainty in the (i) ALOS AW3D30 v. 4.1 DEM, which is ± 5 m vertically, (ii) spatial referencing of Landsat satellite images, considered as ½ pixel size ± 15 m28and (iii) the zonal method used for SLAEOS identification, where SLAEOS is taken as the average elevation of a 20 m bin. Overall, for any individual SLAEOS absolute uncertainty is ± 18.7 m. For our groups of glaciers (space and time; Figs. SI_8, SI_9) typically the standard error is > 15 m in any year for any sub-region and approximately one tenth of that when aggregating into 5-year bins.

Annotated field photo showing end of summer snow line (SLAEOS) and multi-panels depicting the spatial coverage of our analysis; glaciers in black. The number of glaciers in each region depended on filtering glacier sizes and filtering satellite images for timing and cloud cover. Annual counts of glaciers included per sub-region are given in Figure SI_8 and the % area coverage per sub-region is annotated on this figure. The maps in this figure were made using ArcGIS Pro software https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview.

Results: trends in SLAEOS between year 2000 and 2023

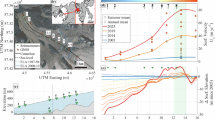

Average SLAEOS increased across the Southern Hemisphere between 2000 and 2023 (p = 0.01), especially between 2011 and 2023 (Figs. 2 and 3). Only the Southern Andes and the Antarctic Peninsula experienced region-wide overall decline in median SLAEOS of −0.98 m yr−1 and − 0.28 m yr−1, respectively (Fig. 3I and J), caused by negative values in the western sub-regions only (Fig. 2B and E).

The Southern Alps of New Zealand had the greatest west – east similarity in absolute SLAEOSs (< 100 m) of any region (Fig. 3G and H), the most consistent pattern between east and west, and the lowest inter-annual variability (Fig. 2A). Between 2000 and 2023, SLAEOS rose in the western and eastern parts of the Southern Alps by 1.26 ± 0.21 m yr−1 (p = 0.049) and 3.19 ± 0.20 m yr−1 (p = 0.002), respectively (Fig. 3) SLAEOS anomalies, relative to the study period mean, have been consistently slightly positive across the Southern Alps for the last 13 years since 2010 (Fig. 2A).

The Antarctic Peninsula had SLAEOS rates of change of −0.28 ± 0.32 m yr−1 in the west (insignificant p = 0.921), and contrastingly the east showed the fastest rate of rise of any region at 6.39 ± 0.39 m yr−1 (p = 0.013) (Fig. 3). There was a slight deceleration in the rate of SLAEOS rise in the west (x −1.0) and only a slight increase in the east (x 0.8) of the Antarctic Peninsula comparing the decade 2000 to 2010 with the decade 2011 to 2023 (Fig. 2B).

Spatio-temporal patterns in SLAEOS varied in magnitude considerably across the Andes. Aside from the aforementioned west Southern Andes, the other Andes regions all showed accelerated rates of SLAEOS rise, when comparing rates between 2000 and 2010 with those of 2010 to 2023. Region-wide median rates in the west and the east of the Central Andes were not statistically significant at 5.5 ± 2.07 m yr−1 (p = 0.120) and 6.13 ± 0.25 m yr−1 (p = 0.052), respectively (Fig. 3A and B). The Central Chilean Andes had the greatest west – east differences in absolute SLAEOS of any region, typically of c. 900 m, and also the greatest inter-region variability (largest inter-quartile range; Fig. 3C and D). The west and east region-wide median rates were 5.36 ± 0.95 m yr−1 (p = 0.003) and 3.08 ± 0.38 m yr−1 (p = 0.002), respectively (Fig. 3C and D). In the Southern Andes the west and east region-wide median rates changed insignificantly by −0.98 ± 0.13 m yr−1 (p = 0.486) and 2.30 ± 0.07 m yr−1 (p = 0.119), respectively, between 2000 and 2023 (Fig. 3E and F). SLAEOS anomalies in the Central Andes and Central Chilean Andes regions have been increasingly positive, compared to the study period mean since 2015 and 2012, respectively (Fig. 2C and D).

Time series of SLAEOS for each major glaciated region of the Southern Hemisphere, split east and west (left column), and annual anomalies; differences with the study period mean (right column). The quantity in bold inset to the SLAEOS plots denotes the acceleration when comparing pre-2010 to post-2010 rates of change. Note all y scales for SLAEOS span 1000 m except that for the Central Chilean Andes. Open triangles are where n < 10. Dashed Lines are a 5-year moving average. Region-wide annual anomalies are calculated relative to the 2000 to 2023 mean.

Spatial patterns and variability

In the Southern Alps, SLAEOS persistently increased in elevation from south-west to north-east. The eastern side of the Southern Alps main divide showed consistently higher mean SLAEOS than the west over the study period, but typically by only ~ 75 m (Fig. 4A and B). However, there is no discernible spatial pattern in the mean rate of SLAEOS change across the Southern Alps during the entire study period 2000 to 2023 nor in the difference between the two sub time periods (Fig. 4C).

SLAEOS was highly variable spatially across the Antarctic Peninsula, with inland parts having higher SLAEOS (> 1100 m a.s.l.) than most coastal parts (< 200 m a.s.l., including the periphery South Shetlands and South Orkneys). The north-east coast of the Peninsula showed notably higher SLAEOS (~ 300 to 800 m a.s.l.) than other coasts, particularly between 2000 and 2010 (Fig. 4A). Western parts of the Peninsula had higher mean SLAEOS than eastern parts except in years 2010, 2014, 2016 and 2020. SLAEOS increased significantly (5.2 m yr−1; p = 0.013) in the east, whereas it decreased non-significantly (−0.3 m yr−1; p = 0.921) in the west. Comparing the rates of the two sub time-periods, the north-east of the Peninsula had rates of SLAEOS that increased faster than in the south-west (Fig. 4C).

The acceleration in SLAEOS rise, as defined by an increased rate of change when comparing rates between 2000 and 2010 with rates from 2010 to 2023, has been much more pronounced in the west (x 4.0) of the Southern Alps than the east (x 1.2) (Fig. 2A). SLAEOS rise has been really remarkably consistent across the Andes east sub-regions, whilst varying greatly in the west Andes sub-regions (Fig. 4a and B). The Central Andes, Central Chilean Andes and Patagonia had mean rates of SLAEOS change that were generally positive (Fig. 4A, B and C), whereas Tierra del Fuego had mean rates of change in SLAEOS that were negative during the study period 2000 to 2023 (Fig. 4C).

Spatial pattern of the mean rate of change in SLAEOS for all glaciers within each tessellation cell from 2000 to 2010 (A) and from 2011 to 2023 (B). The difference in rate between the two time periods (C) uses the same colour scale. The maps in this figure were made using ArcGIS Pro software https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview.

Discussion

Our comparisons for each sub-region of the multi-decadal mean SLAEOS (Fig. 3), inter-annual anomalies (Fig. 2) and the difference between the pre- and post-2010 mean SLAEOS (Fig. 2) all reveal rising and accelerated rates of rise. The sub-regions that are exceptions are western Antarctic Peninsula and western Southern Andes where decreases in SLAEOS occurred, probably reflecting the role of effective precipitation; with rising temperatures remaining below zero and thus increasing snowfall29. There is therefore a pervasive pattern across most of Southern Hemisphere glaciers of diminishing glacier accumulation areas, enlarging glacier ablation areas and hence increasingly negative glacier mass balance, which has implications for committed meltwater production in the coming decades. We tested for statistically significant correlations of SLAEOS with summer (December to March) air temperature and snowfall but the trends in the climate data are slight (Fig. SI_13, Table SI_4) reflecting high variability even within sub-regions. Such high inter-regional variability could reflect the importance of micro-climate; e.g. warming crossing the zero degree threshold for solid versus liquid precipitation, and control of local topographical and glaciological factors (e.g. Fig. SI_7).

Where glaciers are ice cap type, such as the glacierised volcanoes and Patagonian ice fields of South America, many parts of the mainland Antarctic Peninsula and surrounding islands, rising SLAEOS intersecting plateau edges will cross a tipping point whereby large proportions of the glacier accumulation area will be exposed to melt, fundamentally changing glacier geometry and velocity regimes30,31as well as lowering glacier albedo and raising the possibility of extremely rapid mass loss32,33.

The positive correlations of these SLAEOS rises with geodetic mass balance3 (Fig. 5) highlights that inter-regional differences in SLAEOS across the Southern Hemisphere span > 5500 m in elevation, and that is well-known to reflect extremely diverse climate - topography interactions and hence glacier types. In particular, the intra-regional differences in SLAEOS is greatest in the Central Chilean Andes (Fig. 3), but through time, in 5-year bins, the greatest mass balance range occurs in the Southern Alps (Fig. 5). More generally, Fig. 5 suggests that the response of glaciers in the Southern Hemisphere to changes in SLA is heterogeneous. Glaciers situated at very high-elevation (Central Andes) have experienced some of the fastest changes in SLAEOS, but the impact on mass balance has been low. Glaciers in the mid- and high-elevation range (Central Chilean Andes, Southern Andes and the Southern Alps) have experienced mostly rapid rises in SLAEOS, and the impact on mass balance has been high. Glaciers at the lowest elevations (i.e. mostly on the Antarctic Peninsula) have seen changes in SLAEOS that vary, but the mass balance changes have been moderate, as well as positive. These groups primarily reflect the dominant climate regime within each region, along with glacier-specific factors such as area, slope and elevation, which together define the mass balance gradient (rate of input vs. output) and therefore a glacier’s sensitivity to changes in accumulation and ablation34,35,36.

Comparison of glacier mass balance (dMdtdA)3 with our SLAEOS for 5-year bins and for each sub-region. Where our SLAEOS trends are significant, the dotted trend Line has an arrow centred on the 2015 to 2019 data point.

Associations of SLAs with climate

In the Southern Alps the spatial pattern of change comprising increasing SLAEOS from south-west to north-east is supported by analysis of the independent aerial survey dataset5,9,10 (Figs. SI_10, SI_11). Lower SLAEOS on the west of the main divide can be explained by the synoptic climate control on snow accumulation. Specifically, the steep elevation increase from sea level at the west coast to > 3000 m a.s.l., coupled with prevailing westerly air circulation over the Tasman Sea, produce a strong east-west orographic precipitation gradient37 and ~ 30% greater snowfall on glaciers to the west when compared to those on the east of the topographic divide38,39. The north-south pattern in SLAEOS is likely due to a weak but persistent latitudinal air temperature gradient40,41 and possibly also to the more southerly aspect of southernmost glaciers that affects solar radiation intensity5.

The lowering SLAEOS between 2000 and 2008 and increases thereafter (Fig. 2A), coincides with a period of well-documented42 glacier advance between 1983 and 2008 relating to a period of reduced air and sea surface temperatures (SST). Mass balance simulations42 confirm that year 2000, when a positive anomaly is observed on the SLAEOS (Fig. 2A), had the most negative Southern Alps mean mass balance on record from 1972 to 2011, attributed to positive temperature anomalies enhancing snow and glacier ice ablation in the 1999/2000 summer. Another peak in SLAEOS in 2016 (Fig. 2A) can also be explained climatically; a strong ENSO in 2015/2016 austral summer43,44,45 caused air temperatures across New Zealand > 1.2˚C above average (NIWA, 2016); the Tasman Sea experienced an extreme and prolonged marine heatwave10,46,47,48and elevated precipitation to the West Coast and Tasman zones49.

The pattern of SLAEOS across the Antarctic Peninsula from 2000 to 2023 is closely associated with glacier/terrain elevation. Coastal sub-regions had consistently lower SLAEOS (Fig. 3B) than inland sub-regions and it is these coastal parts of the Antarctic Peninsula and surrounding islands that host low-lying marine-terminating glaciers and ice cap outlet glaciers50. Our finding of generally higher SLAEOS in the west (Fig. 2B) contradicts claims that glacier ELAs are higher in the east of the Antarctic Peninsula51,52 and also suggestions of a west-to-east precipitation decline53 arising from an orographic influence of the inland plateau on westerly moisture transport54.

Our results from the Antarctic Peninsula imply that temporal trends in SLAEOS accelerated from 2011 with a faster rate of rise in the east, slower rate of rise in the west, and overall more positive SLAEOS anomalies from 2017 (Fig. 2B). This temporal trend suggests that the well-reported temperature sensitivity of these glaciers55,56,57 is reflected in SLAEOS as the Antarctic Peninsula experienced overall cooling from the late 1990 s to the mid-2010s58,59followed by warming to 202061. The decreased rate of SLAEOS rise in the west can be explained by increased temperatures bringing more snowfall, as has been credited for especially low glacier ELA on King George Island and on the Antarctic Peninsula61,62.

The Central Andes show SLAEOS values that are higher overall for western glaciers than for eastern glaciers, but this spatial pattern is reversed for the Central Chilean and Southern Andes (Fig. 2C, D, E and F). The SLAEOS east-west pattern(s) across the Andes (Fig. 3A and B) are directly aligned with the direction of east-west precipitation gradients with latitude. North of ~ 23–29˚S, moisture transport within the Central sub-regions primarily originates in the Atlantic and circulates easterly to the Andes, which themselves act as a topographic barrier largely preventing moisture transport to western glaciers63,64. South of 29˚S, Pacific moisture transport becomes more prominent64although between 29˚S and 35˚S the east-west precipitation contrast is reduced65 as easterly circulation becomes more dominant in summer66. South of 35˚S, strong westerly circulation delivers high quantities of precipitation to western glaciers, enhanced by orographic effects, which minimise precipitation delivery to the east63,65.

The Central Andes SLAEOS lacks a significant trend, characterised instead by very high inter-annual variability (Fig. 2D). The multiple short periods of snowline lowering (particularly 2004 to 2006, but also 2013 to 2015 and 2016 to 2018) (Fig. 2D) partly correspond with the negative SLA trend noted at Zongo Glacier, Bolivia, from 1996 to 20066869,. SLAEOS variability in the Central Andes is seemingly linked with ENSO fluctuations; mean SLAEOS was very low in 2001, indicating the La Niña event that brought the lowest maximum and minimum summer air temperatures and third-highest summer precipitation quantity of the period 2000 to 201770. Additionally and independently, Veettil et al.70 demonstrated that SLA at a Central Andes site rose rapidly in 2003, similar to the trend in our Fig. 2D, and when the ENSO was in a warm and dry phase and when simultaneously the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) was in its most positive phase of the period 2000 to 2015.

Rising glacier SLAs across the Central Chilean Andes is well-documented71 as is a rise in minimum glacier elevation72 summer snow cover decline73 and glacier mass loss74. Saavedra et al.71 reported SLA rise at 10 to 30 m.yr−1 south of 29–30˚S and those rates approximately correspond to 75th and 99th percentiles of our data for this region (10 and 40 m.yr−1, respectively). The higher rate of mean SLAEOS rise in the Central Chilean Andes compared to the Central Andes has been attributed to reduced precipitation71 and indeed a ‘mega-drought’75 has persisted across the Central Chilean Andes since 2010, causing accelerated glacier thinning76 declined snow persistence77 and early-summer snowline rise78. Accordingly, the rate of change in SLAEOS more or less doubled during 2011 to 2023 compared to the rate during 2000 to 2010, slightly more so in the east than in the west (Fig. 2E).

Our SLAEOS anomalies were greatest in the Central Chilean Andes in 2009, 2015, 2018, 2021 and 2023, and lowest in 2003 (Fig. 2E), and concurrent with minimum summer snow extent in 2009 and 2015 for the 34–40˚S sub-region73. The timing of low SLAEOS and maximum snow extent of 2003 corresponds to an El Niño period73 which, unlike in the Central regions at lower latitude, is associated with anomalously warm temperatures and high snowfall south of 29˚S78,79. The Central Chilean SLAEOS highs of 2009 and 2015 (Fig. 2E) correspond with strongly positive Southern Annular Mode (SAM)73 and therefore weaker mid-latitude westerlies80 whilst minimum SLAEOS in 2003 (Fig. 2E) correspond to strongly negative SAM, and stronger westerlies. In contrast, inter-annual variability in Central Chilean SLAEOS compares less well to variations in ENSO phase between 2000 and 201574, implying increased SAM conditions in the Central Chilean region71 and persistently so since 2018.

The SLAEOS trends (Fig. 2F) and patterns (Fig. 3A, B, C) across the Southern Andes are the most complicated of all the Southern Hemisphere regions, illustrating marked contrasts in sub-regional climate and climate change. Rates of change in SLAEOS were slightly positive for the North Patagonian Icefield (NPI: 2.78 m.yr−1) and South Patagonian Icefield (SPI: 1.49 m.yr−1) and negative for Cordillera Darwin (CD: −3.05 m.yr−1). The reduced rate of SLAEOS rise in the SPI compared to the NPI corresponds to reports of SPI glaciers displaying neutral or positive mass balance, and/or stable or advancing extents in recent years81,82,83. Increasingly stable SLAs in the higher-latitude CD (Fig. 3C) can be explained by increasing precipitation84 that has arisen from southward displacement and intensification of westerlies at ~ 60˚S following increased SAM index and formation of anomalous low pressure near Drake Passage80,85,86.

Much of our observed inter-annual variability in Southern Andes SLAEOS is consistent with reported variability in glacier change and reported climatic variability. For example, the low mean SLAEOS and strongly negative SLAEOS anomaly in 2001 (Fig. 2F) coincides with a positive summer precipitation anomaly and negative summer temperature anomaly observed in the Aysén river basin at 45–46˚S87. Pérez et al.87 also document 2001 as the year of maximum summer snow extent in Patagonia between 2000 and 2016. Our greatly reduced SLAEOS in 2010/2011 (Fig. 2F) coincides with a sudden decrease in frontal ablation rates of SPI glaciers, Uppsala and Jorge Montt, in 2010/201189 and is Likely explained by positive summer precipitation anomalies between 2009 and 2011, and a coincident negative summer air temperature anomaly in 201088. Overall, our Southern Andes results imply that the well-reported poleward displacement of SAM-driven westerlies73 is causing increased aridity in the Patagonian Icefields and increased snowfall in Tierra del Fuego.

Summary and conclusions

In summary, our study is novel in showing that SLAEOS on Southern Hemisphere glaciers have been rising over the last two decades, and with an accelerating rate of rise in almost all mountain regions. Our quantification of temporal trends suggests large-scale region-wide warming but also influence of westerlies bringing precipitation to the west Southern Alps, west Antarctic Peninsula and western Andes. Inter-regional comparisons reveal teleconnections between Andean and Southern Alps glaciers; in-phase for northern Andes and out-of-phase for Patagonia88. Inter-annual variability (highly positive or negative anomalies) in regions such as the Antarctic Peninsula and Southern Andes suggests spatio-temporally complex climate systems, or confounding influences of warming and precipitation regime (solid v liquid) shifts. Elsewhere, such as in the Central Chilean Andes, consistently positive anomalies suggest that some climate system modes appear to be persistent and perhaps becoming stronger.

Given projected air warming for all regions89,90and projections of a strengthening SAM91,92 and thus intensified westerlies93 high- and mid-latitudes can expect summer drying75,94,95,96 and any increases in precipitation at lower latitudes will not alleviate glacier mass loss97,98. The frequency and intensity of ENSO phase transitions is also expected to amplify over coming decades43 which will affect the variability of drought conditions79,99 and blocking episodes100.

The most vulnerable glacier sub-regions to ongoing change, as indicated by our SLAEOS observations, are (i) the eastern parts of the high-latitude ranges owing to downslope wind (e.g., foehn) driven by westerly wind intensification101,102 (ii) the Central Chilean Andes where both SAM and La Niña effects bring increased drought, and (iii) the maritime Southern Alps where marine heatwaves are set to intensify75 (iv) large parts of ice caps and icefields becoming exposed to ablation as SLAEOS rises above plateau edges.

In conclusion, the upward and accelerating rate of rise of SLAs across the Southern Hemisphere that this study identifies and quantifies is likely to continue. Those rising SLAs and hence ELAs are forcing glaciers to be out of equilibrium with present day climate and to amount that is determined by glacier response times and with committed loss of ice. Unravelling the spatio-temporal patterns in SLAEOS and hence ELAs will aid understanding glacier response times, committed ice losses and overall meltwater production in the coming decades, respectively.

Data availability

Glacier outlines are available from Global land Ice Measurements from Space via the National Snow and Ice Data Center (GLIMS and NSIDC, 2005, updated 2018) [http://glims.colorado.edu/glacierdata/](http:/glims.colorado.edu/glacierdata)Landsat Surface Reflectance at 30 m resolution from the U.S. Geological Survey is available from several data portals [https://www.usgs.gov/landsat-missions/landsat-data-access](https:/www.usgs.gov/landsat-missions/landsat-data-access)Elevation data at 30 m resolution is available from JAXA ALOS World 3D Digital Surface Model [https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ALOS/en/dataset/aw3d30/aw3d30_e.htm](https:/www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ALOS/en/dataset/aw3d30/aw3d30_e.htm)ERA-5 Land monthly aggregated data [https://confluence.ecmwf.int/display/CKB/ERA5-Land%3 A+data+documentation](https:/confluence.ecmwf.int/display/CKB/ERA5-Land%3 A+data+documentation)Drainage Basins are available from World Wildlife Fund HydrSHEDS [https://www.hydrosheds.org/](https:/www.hydrosheds.org).

Code availability

An annotated copy of our SLAEOS code for GEE is available at: https://code.earthengine.google.com/c578633c5a8b1d480eef09c97ec8fcb0.

References

Zemp, M., Hoelzle, M. & Haeberli, W. Six decades of glacier mass-balance observations: a review of the worldwide monitoring network. Ann. Glaciol. 50 (50), 101–111 (2009).

Braithwaite, R. J. & Hughes, P. D. Regional geography of glacier mass balance variability over seven decades 1946–2015. Frontiers in Earth Science, 8, 302. (2020).

Hugonnet, R. et al. Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century. Nature 592 (7856), 726–731 (2021).

Braithwaite, R. J. Can the mass balance of a glacier be estimated from its equilibrium-line altitude? J. Glaciol. 30 (106), 364–368 (1984).

Carrivick, J. L. & Chase, S. E. Spatial and Temporal variability of annual glacier equilibrium line altitudes in the Southern Alps, New Zealand. NZ J. Geol. Geophys. 54 (4), 415–429 (2011).

Mernild, S. H. et al. Identification of snow ablation rate, ELA, AAR and net mass balance using transient snowline variations on two Arctic glaciers. J. Glaciol, 59, 649–659 (2013).

Benn, D. I. & Lehmkuhl, F. Mass Balance and equilibrium-line Altitudes of Glaciers in high-mountain Environments. Quaternary International, 65, 15–29 (2000).

Ohmura, A. & Boettcher, M. On the shift of glacier equilibrium line altitude (ELA) under the changing climate. Water, 14(18), 2821. (2022).

Chinn, T. J. H. Glacier fluctuations in the Southern alps of New Zealand determined from snowline elevations. Arct. Alp. Res. 27 (2), 187–198 (1995).

Lorrey, A. M. et al. Southern alps equilibrium line altitudes: four decades of observations show coherent glacier–climate responses and a rising snowline trend. J. Glaciol. 68 (272), 1127–1140 (2022).

Li, X., Wang, N. & Wu, Y. Automated glacier snow line altitude calculation method using Landsat series images in the Google Earth engine platform. Remote Sens. 14 (10), 2377 (2022).

Abrahim, B., Cullen, N., Conway, J. & Sirguey, P. Applying a distributed mass-balance model to identify uncertainties in glaciological mass balance on Brewster Glacier, New Zealand. J. Glaciol., 1–17. (2023).

Zwally, H. J. & Fiegles, S. Extent and duration of Antarctic surface melting. J. Glaciol. 40 (136), 463–475 (1994).

Soenen, S. A., Peddle, D. R. & Coburn, C. A. SCS + C: A modified Sun-Canopy-Sensor topographic correction in forested terrain. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 43 (9), 2148–2159 (2005).

Stringer, C. D. [code]ontemporary (2016–2020) land cover across West Antarctica and the McMurdo dry valleys [Code] (Version 1). Zenodo. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6720051 (2022). Last accessed May 23.

Poortinga, A. et al. Mapping plantations in Myanmar by fusing Landsat-8, Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-1 data along with systematic error quantification. Remote Sens. 11 (7), 831 (2019).

Jasrotia, A. S., Kour, R. & Ashraf, S. Impact of illumination gradients on the raw, atmospherically and topographically corrected snow and vegetation areas of Jhelum basin, Western Himalayas. Geocarto Int. 37 (26), 14027–14049 (2022).

Vázquez-Jiménez, R., Romero-Calcerrada, R., Ramos-Bernal, R. N., Arrogante-Funes, P. & Novillo, C. J. Topographic Correction to Landsat Imagery through Slope Classification by Applying the SCS + C Method in Mountainous Forest Areas. International Journal of Geo-information, 6(287). (2017).

Al-Doski, J., Mansor, S. B., San, H. P. & Khuzaimah, Z. No. 7 SCS + C Topographic Correction To Enhance SVM Classification Accuracy. Journal of Engineering Technology and Applied Physics. Special Issue 1. (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Landsat satellites observed dynamics of snowline altitude at the end of the melting season, Himalayas, 1991–2022. Remote Sensing, 15(10), 2534. (2023).

Otsu, N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybernetics. 9, 62–66 (1979).

Paul, F., Winsvold, S. H., Kääb, A., Nagler, T. & Schwaizer, G. Glacier remote sensing using Sentinel-2. Part II: Mapping glacier extents and surface facies, and comparison to Landsat 8. Remote Sensing, 8(7), 575. (2016).

Sun, X. et al. Integrating Otsu Thresholding and Random Forest for Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Classification and Seasonal Analysis of Water and Snow/Ice. Remote Sensing, 17 (5), p.797. (2025).

Singh, D. K., Thakur, P. K., Naithani, B. P. & Kaushik, S. Quantifying the sensitivity of band ratio methods for clean glacier ice mapping. Spat. Inform. Res. 29, 281–295 (2021).

Ortiz Diaz, I., Lenzano, M. G. & Araneo, D. Temporal Estimation of snow line altitude in glaciers of the Southern Patagonian icefield using Google Earth engine. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 48, 19–24. (2013).

Gaddam, V. K., Boddapati, R., Kumar, T., Kulkarni, A. V. & Bjornsson, H. Application of OTSU—an image segmentation method for differentiation of snow and ice regions of glaciers and assessment of mass budget in Chandra basin, Western himalaya using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194, 337 (2022).

Prudente, V. H. R., Martins, V. S. & Vieira, D. C. Rodrigues de França e Silva, N., Adami, M., and Sanches, I.D. Limitations of cloud cover for optical remote sensing of agricultural areas across South America. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, 20, 100414. (2020).

Paul, F. et al. On the accuracy of glacier outlines derived from remote-sensing data. Ann. Glaciol. 54 (63), 171–182 (2013).

Turner, J., Lachlan-Cope, T., Colwell, S. & Marshall, G. J. A positive trend in Western Antarctic Peninsula precipitation over the last 50 years reflecting regional and Antarctic-wide atmospheric circulation changes. Ann. Glaciol. 41, 85–91 (2005).

Rippin, D. M., Sharp, M., Van Wychen, W. & Zubot, D. Detachment’of icefield outlet glaciers: catastrophic thinning and retreat of the Columbia glacier (Canada). Earth. Surf. Proc. Land. 45 (2), 459–472 (2020).

Davies, B. et al. Topographic controls on ice flow and recession for Juneau Icefield (Alaska/British Columbia). Earth. Surf. Proc. Land. 47 (9), 2357–2390 (2022).

Davies, B. et al. Accelerating glacier volume loss on Juneau Icefield driven by hypsometry and melt-accelerating feedbacks. Nature Communications, 15 (1), 5099. (2024).

Ing, R. N., Ely, J. C., Jones, J. M. & Davies, B. J. Surface mass balance modelling of the Juneau Icefield highlights the potential for rapid ice loss by the mid-21st century. J. Glaciol. 71, e11 (2025).

Bahr, D. B., Pfeffer, W. T., Sassolas, C. & Meier, M. F. Response time of glaciers as a function of size and mass balance: 1. Theory. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth. 103 (B5), 9777–9782 (1998).

Harrison, W. D., Elsberg, D. H., Echelmeyer, K. A. & Krimmel, R. M. On the characterization of glacier response by a single time-scale. J. Glaciol. 47 (159), 659–664 (2001).

Raper, S. C. & Braithwaite, R. J. Glacier volume response time and its links to climate and topography based on a conceptual model of glacier hypsometry. Cryosphere 3 (2), 183–194 (2009).

Chinn, T. J. New Zealand glacier response to climate change of the past 2 decades. Glob. Planet Change. 22 (1–4), 155–168 (1999).

Henderson, R. D. & Thompson, S. M. Extreme rainfalls in the Southern Alps of New Zealand. J. Hydrology (New Zealand). 38 (2), 309–330 (1999).

Purdie, H., Mackintosh, A., Lawson, W. & Anderson, B. Synoptic influences on snow accumulation on glaciers east and west of a topographic divide: Southern Alps, New Zealand. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 43 (1), 82–94. (2011).

MetService. New Zealand Climate. Available online: (2023). https://about.metservice.com/our-company/learning-centre/new-zealand-climate/ Last accessed August 2023.

NIWA. Overview of New Zealand’s climate. Available online: (2024). https://niwa.co.nz/education-and-training/schools/resources/climate/overview#:~:text=New%20Zealand’s%20climate%20is%20complex,conditions%20in%20the%20mountainous%20areas Last accessed August 2023.

Mackintosh, A. N. et al. Regional cooling caused recent New Zealand glacier advances in a period of global warming. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 14202 (2017).

Cai, W. et al. Climate impacts of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation on South America. Nat. Reviews Earth Environ. 1 (4), 215–231 (2020).

Bodart, J. A. & Bingham, R. J. The impact of the extreme 2015–2016 El Niño on the mass balance of the Antarctic ice sheet. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46 (23), 13862–13871 (2019).

Vera, C. S. & Osman, M. Activity of the Southern annular mode during 2015–2016 El Niño event and its impact on Southern Hemisphere climate anomalies. Int. J. Climatol. 38, e1288–e1295 (2018).

Oerlemans, J. & Reichert, B. K. Relating glacier mass balance to meteorological data by using a seasonal sensitivity characteristic. J. Glaciol. 46 (152), 1–6 (2000).

Clare, G. R., Fitzharris, B. B., Chinn, T. J. H. & Salinger, M. J. Interannual variation in end-of-summer snowlines of the Southern Alps of New Zealand, and relationships with Southern Hemisphere atmospheric and sea surface temperature patterns. Int. J. Climatol. 22, 107–120 (2002).

Oliver, E. C. et al. The unprecedented 2015/16 Tasman sea marine heatwave. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 16101 (2017).

NIWA. Seasonal Climate Summary: Summer 2015-16 Available online: (2016). https://niwa.co.nz/sites/niwa.co.nz/files/Climate_Summary_Summer_2016_FINAL.pdf Last accessed August 2023.

Huber, J., Cook, A. J., Paul, F. & Zemp, M. A complete glacier inventory of the Antarctic Peninsula based on Landsat 7 images from 2000 to 2002 and other pre-existing data sets. Earth Syst. Sci. data, 9(1), 115–131. (2017).

Carrivick, J. L., Davies, B. J., James, W. H., McMillan, M. & Glasser, N. F. A comparison of modelled ice thickness and volume across the entire Antarctic Peninsula region. Geogr. Annaler: Ser. Phys. Geogr. 101 (1), 45–67 (2019).

Davies, B. J., Carrivick, J. L., Glasser, N. F., Hambrey, M. J. & Smellie, J. L. Variable glacier response to atmospheric warming, Northern Antarctic Peninsula, 1988–2009. Cryosphere 6, 1031–1048 (2012).

González-Herrero, S. et al. Extreme precipitation records in Antarctica. Int. J. Climatol. 43 (7), 3125–3138 (2023).

Slonaker, R. L. & Van Woert, M. L. Atmospheric moisture transport across the Southern Ocean via satellite observations. J. Geophys. Research: Atmos. 104 (D8), 9229–9249 (1999).

Abram, N. J. et al. Acceleration of snow melt in an Antarctic Peninsula ice core during the twentieth century. Nat. Geosci. 6 (5), 404–411 (2013).

Davies, B. J. et al. Modelled glacier response to centennial temperature and precipitation trends on the Antarctic Peninsula. Nat. Clim. Change. 4, 993–998 (2014).

Navarro, F. J., Jonsell, U. Y., Corcuera, M. I. & Martín-Español, A. Decelerated mass loss of Hurd and Johnsons glaciers, Livingston island, Antarctic Peninsula. J. Glaciol. 59 (213), 115–128 (2013).

Oliva, M. et al. Recent regional climate cooling on the Antarctic Peninsula and associated impacts on the cryosphere. Sci. Total Environ. 580, 210–223 (2017).

Turner, J. et al. Absence of 21st century warming on Antarctic Peninsula consistent with natural variability. Nature 535 (7612), 411–415 (2016).

Carrasco, J. F., Bozkurt, D. & Cordero, R. R. A review of the observed air temperature in the Antarctic Peninsula. Did the warming trend come back after the early 21st hiatus? Polar Sci. 28, 100653 (2021).

Falk, U., Gieseke, H., Kotzur, F. & Braun, M. Monitoring snow and ice surfaces on King George island, Antarctic Peninsula, with high-resolution TerraSAR-X time series. Antarct. Sci. 28 (2), 135–149 (2016).

Zhou, C., Liu, Y. & Zheng, L. Satellite-derived dry-snow line as an indicator of the local climate on the Antarctic Peninsula. J. Glaciol. 68 (267), 54–64 (2022).

Garreaud, R. D. The Andes climate and weather. Adv. Geosci. 22, 3–11 (2009).

Masiokas, M. H. et al. A review of the current state and recent changes of the Andean cryosphere. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 99 (2020).

Viale, M. et al. Contrasting climates at both sides of the Andes in Argentina and Chile. Front. Environ. Sci. 7, 69 (2019).

Viale, M. & Garreaud, R. Summer precipitation events over the Western slope of the subtropical Andes. Mon. Weather Rev. 142 (3), 1074–1092 (2014).

Rabatel, A. et al. Can the snowline be used as an indicator of the equilibrium line and mass balance for glaciers in the outer tropics? J. Glaciol. 58 (212), 1027–1036 (2012).

Veettil, B. K., Wang, S., Bremer, U. F., de Florêncio, S. & Simões, J. C. Recent trends in annual snowline variations in the northern wet outer tropics: case studies from the Southern Cordillera Blanca, Peru. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 129, 213–227 (2017).

Imfeld, N. et al. A combined view on precipitation and temperature climatology and trends in the Southern Andes of Peru. Int. J. Climatol. 41 (1), 679–698 (2021).

Veettil, B. K., Bremer, U. F., de Souza, S. F., Maier, É. L. B. & Simões, J. C. Influence of ENSO and PDO on mountain glaciers in the outer tropics: case studies in Bolivia. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 125, 757–768 (2016).

Saavedra, F. A., Kampf, S. K., Fassnacht, S. R. & Sibold, J. S. Changes in Andes snow cover from MODIS data, 2000–2016. Cryosphere 12, 1027–1046 (2018).

Malmros, J. K., Mernild, S. H., Wilson, R., Yde, J. C. & Fensholt, R. Glacier area changes in the central Chilean and Argentinean Andes 1955–2013/14. J. Glaciol. 62 (232), 391–401 (2016).

Cordero, R. R. et al. Dry-season snow cover losses in the Andes (18°–40°S) driven by changes in large-scale climate modes. Sci. Rep. 9, 16945 (2019).

Dussaillant, I. et al. Two decades of glacier mass loss along the Andes. Nat. Geosci. 12 (10), 802–808 (2019).

Garreaud, R. D. et al. The central Chile mega drought (2010–2018): a climate dynamics perspective. Int. J. Climatol. 40 (1), 421–439 (2020).

Farías-Barahona, D. et al. 60 years of glacier elevation and mass changes in the Maipo river basin, central Andes of Chile. Remote Sens. 12 (10), 1658 (2020).

Masiokas, M. H., Villalba, R., Luckman, B., LeQuesne, C. & Aravena, J. C. Snowpack variations in the central Andes of Argentina and Chile, 1951–2005: large-scale atmospheric influences and implications for water resources in the region. J. Clim. 19, 6334–6352 (2006).

Garreaud, R. D. et al. The 2010–2015 megadrought in central Chile: impacts on regional hydroclimate and vegetation. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21 (12), 6307–6327 (2017).

Rivera, J. A., Penalba, O. C., Villalba, R. & Araneo, D. C. Spatio-temporal patterns of the 2010–2015 extreme hydrological drought across the central Andes, Argentina. Water 9 (9), 652 (2017).

Thompson, D. W. et al. Signatures of the Antarctic ozone hole in Southern Hemisphere surface climate change. Nat. Geosci. 4 (11), 741–749 (2011).

Bravo, C. et al. Assessing snow accumulation patterns and changes on the Patagonian icefields. Front. Environ. Sci., 7, 30. (2019).

Minowa, M., Schaefer, M., Sugiyama, S., Sakakibara, D. & Skvarca, P. Frontal ablation and mass loss of the Patagonian icefields. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 561, 116811 (2021).

Wilson, R., Carrión, D. & Rivera, A. Detailed dynamic, geometric and supraglacial moraine data for glaciar Pio XI, the only surge-type glacier of the Southern Patagonia Icefield. Ann. Glaciol. 57 (73), 119–130 (2016).

Carrasco, J. F., Osorio, R. & Casassa, G. Secular trend of the equilibrium-line altitude on the Western side of the Southern Andes, derived from radiosonde and surface observations. J. Glaciol. 54 (186), 538–550 (2008).

Aguirre, F. et al. Snow cover change as a climate indicator in Brunswick Peninsula, Patagonia. Front. Earth Sci. 6, 130 (2018).

Carrasco-Escaff, T., Rojas, M., Garreaud, R. D., Bozkurt, D. & Schaefer, M. Climatic control of the surface mass balance of the Patagonian icefields. Cryosphere 17 (3), 1127–1149 (2023).

Pérez, T., Mattar, C. & Fuster, R. Decrease in snow cover over the Aysén river catchment in Patagonia. Chile Water. 10 (5), 619 (2018).

Fitzharris, B. B., Clare, G. R. & Renwick, J. Teleconnections between Andean and New Zealand glaciers. Glob. Planet Change. 59 (1–4), 159–174 (2007).

Mao, R. et al. Increasing difference in interannual summertime surface air temperature between interior East Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula under future climate scenarios. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48 (16), e2020GL092031 (2021).

Pabón-Caicedo, J. D. et al. Observed and projected hydroclimate changes in the Andes. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 61 (2020).

Boisier, J. P. et al. Anthropogenic Drying in central-southern Chile Evidenced by long-term Observations and Climate Model Simulations. Science of the Anthropocene, 674. (2018).

Goyal, R., Sen Gupta, A., Jucker, M. & England, M. H. Historical and projected changes in the Southern Hemisphere surface westerlies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48(4), e2020GL090849. (2021).

Deng, K. et al. Changes of Southern hemisphere westerlies in the future warming climate. Atmos. Res. 270, 106040 (2022).

Bodeker, G. et al. Aotearoa New Zealand climate change projections guidance: Interpreting the latest IPCC WG1 report findings. Prepared for the Ministry for the Environment, Report number CR 501, 51p. (2022).

Bozkurt, D., Bromwich, D. H., Carrasco, J. & Rondanelli, R. Temperature and precipitation projections for the Antarctic Peninsula over the next two decades: contrasting global and regional climate model simulations. Clim. Dyn. 56 (11–12), 3853–3874 (2021).

Zazulie, N., Rusticucci, M. & Raga, G. B. Regional climate of the subtropical central Andes using high-resolution CMIP5 models—part I: past performance (1980–2005). Clim. Dyn. 49, 3937–3957 (2017).

Neukom, R. et al. Facing unprecedented drying of the central andes?? Precipitation variability over the period AD 1000–2100. Environ. Res. Lett. 10 (8), 084017 (2015).

Potter, E. R. et al. A future of extreme precipitation and droughts in the Peruvian Andes. Clim. Atmospheric Sci. 6 (1), 96 (2023).

Sulca, J., Vuille, M., Silva, Y. & Takahashi, K. Teleconnections between the Peruvian central Andes and Northeast Brazil during extreme rainfall events in Austral summer. J. Hydrometeorol. 17 (2), 499–515 (2016).

Patterson, M., Bracegirdle, T. & Woollings, T. Southern hemisphere atmospheric blocking in CMIP5 and future changes in the Australia-New Zealand sector. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46 (15), 9281–9290 (2019).

Mao, R. et al. Increasing difference in interannual summertime surface air temperature between interior East Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula under future climate scenarios. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48 (16), e2020GL092031. (2021).

Carrivick, J.L. and Brewer, T.R. Improving local estimations and regional trends of glacier equilibrium line altitudes. Geografiska Annaler: Series A,Physical Geography, 86(1), 67–79 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Environment Research Council highlight topic grant Deplete and Retreat (NE/X004031/1). Li et al. 11 are thanked for making their code available. Chris Stringer and Will James are thanked for their assistance with coding. Comments from anonymous reviewers much improved the manuscript, thank you to them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived the study. M.M conducted developed the code, conducted the analysis, produced the results and a draft text. J.L.C. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared the final figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent from all subjects has been gained for publication of identifying information/images.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

MacFee, M., Carrivick, J.L. & Quincey, D.J. Rising snowline altitudes across Southern Hemisphere glaciers from 2000 to 2023. Sci Rep 15, 35683 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19486-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19486-6