Abstract

Active suspension systems are crucial for improving vehicle ride comfort and handling under road disturbances. However, tuning the parameters of advanced controllers in such systems remains a complex challenge due to the nonlinear nature of vehicle dynamics. This study investigates the control of a quarter car active suspension model using two advanced controller structures: the Proportional–Integral–Derivative with filter (PIDN) and the hybrid Fractional Order PI plus PD (FOPI + FOPD) controller. To enhance controller performance, six recent metaheuristic algorithms—Educational Competition Optimizer (ECO), Escape Optimization Algorithm (ESC), Fata Morgana Algorithm (FATA), Jason Healing Optimization (JHO), Memory, Evolutionary Operator and Local Search Based Improved Grey Wolf Optimizer (MELGWO), and Starfish Optimization Algorithm (SFOA)—are employed for parameter tuning. Simulation results, obtained in the MATLAB/Simulink environment, demonstrate that the ESC-optimized FOPI + FOPD controller achieves the most effective vibration suppression, significantly outperforming classical and fuzzy logic-based approaches in terms of peak overshoot, settling time, and control stability. These findings emphasize the importance of selecting suitable controller structures in conjunction with robust optimization techniques for intelligent suspension system design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suspension systems play a critical role in ensuring both ride comfort and vehicle safety. These systems mitigate vibrations and shocks transmitted from the road surface by absorbing external disturbances, thereby providing a more stable and comfortable driving experience. A well-designed suspension system efficiently absorbs road irregularities, improving both passenger comfort and vehicle handling performance1. Suspension systems are generally classified into two main categories: passive and active. Passive systems operate based on predefined spring and damper characteristics, aiming to absorb impacts mechanically without external input. In contrast, active suspension systems utilize sensors and control algorithms to continuously monitor road and driving conditions, enabling real-time adjustment of suspension responses. This dynamic adaptation significantly enhances both ride comfort and handling capability2.The evolution of suspension technology began in the 1960 s when some luxury vehicle manufacturers implemented hydro-pneumatic active suspension systems. These early implementations were purely mechanical and did not involve any electronic control components3. In the 1980 s, the advancement of analog electronics enabled the development of fully active suspension systems, particularly gaining attention through their use in Formula 1 racing, where they demonstrated superior dynamic performance4. However, the high cost, increased energy consumption, bulky components, and reliability issues of these systems limited their commercial viability5.

During the 1990 s, semi-active suspension systems emerged as a practical alternative. Offering a favorable trade-off between performance and cost, these systems were widely adopted by automotive manufacturers6. Today’s suspension technologies have evolved further, incorporating advanced electronics, sensors, and software-based controllers. High-end vehicles now feature predictive systems that detect road irregularities using cameras and adjust suspension settings in real time7,8. Other adaptive solutions dynamically optimize suspension behavior based on current driving conditions and selected driving modes9. Figure 1 illustrates the Quarter Car Model (QCM) suspension configuration used in this study.

Numerous studies in the literature have been conducted using various vehicle suspension models. These studies typically focus on quarter car, half car, and full car models. Quarter car models are widely used as simplified representations of the vehicle system, particularly for the testing and comparison of control strategies. While half car models incorporate additional dynamic behaviors such as pitch and roll, full car models offer a more comprehensive and realistic representation of overall vehicle dynamics and performance. These models are frequently combined with advanced control methods to enhance suspension performance and improve vehicle dynamics.

Recent advancements in control engineering have introduced various hybrid algorithms and fractional-order controllers that demonstrate improved performance in dynamic system control applications, while recent studies have also explored state-of-the-art fractional control strategies such as low-order fractionalized PID designs and optimization-based PID variants for enhanced system dynamics and adaptability. For instance, Idir et al.10 introduced a fractionalized PID controller optimized via Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO), significantly improving transient and frequency responses in aircraft pitch angle control systems. In automotive applications, a fractionalized PID design utilizing Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) was successfully implemented for cruise control systems, exhibiting enhanced stability and reduced overshoot compared to traditional PID methods11. Similarly, Prusty et al.12 employed an improved moth swarm algorithm-based fractional-order type-2 fuzzy PID controller (FO-T2F-PID), effectively addressing frequency regulation challenges in microgrids. Further, Nayak et al.13 demonstrated that a sunflower optimization algorithm-based fractional-order fuzzy PID controller achieved superior performance in frequency regulation for solar-wind integrated power systems. These studies collectively underscore the efficacy and adaptability of fractional-order and hybrid-optimized control strategies in enhancing dynamic system performance across diverse engineering applications.

In QCM-based research, several control strategies have been extensively applied. Common approaches include the Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller14, Fuzzy Logic Controller (FLC)15, Modal Control (MC)16, Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR)17, State Feedback Controller (SFC)18, and Static Output Feedback (SOF)19. Maximizing the performance of control systems critically depends on the accurate tuning of controller parameters. Optimization algorithms developed for this purpose help eliminate the need for manual trial-and-error processes, enabling fast, efficient, and robust tuning. Today, a broad spectrum of optimization techniques is available. In addition to classical algorithms, including direct or gradient-based techniques, nature-inspired, and bio-inspired artificial intelligence algorithms have gained popularity. Among these are the Genetic Algorithm (GA)20, Ant Colony Optimization (ACO)21, PSO22, Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA)23, Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)24, Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), and Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm 2 (SPEA2)25.

The literature on vehicle suspension systems includes a wide range of studies that integrate various controller designs with optimization algorithms. These studies aim to improve system performance by optimizing controller parameters according to specific objective functions. Notable recent works are summarized in Table 1.

Research gap and contribution to literature

Although existing research on quarter car suspension models has achieved significant advancements in terms of control strategies and optimization techniques, several critical gaps remain in the literature. While conventional PID controllers are widely employed, the dynamic performance of Proportional-Integral-Derivative with filter (PIDN) and Fractional Order PI–PD (FOPI–FOPD) controllers on two-degree-of-freedom (2 DOF) quarter car models has not been thoroughly investigated.

In addition, prior studies often suffer from limitations such as a narrow focus on single controller types, insufficient exploration of fractional-order dynamics, and a lack of multi-objective performance evaluations. Moreover, widely used algorithms like PSO and GA are known to encounter issues related to premature convergence and sensitivity to initial conditions, which may compromise their robustness in complex search spaces.

Furthermore, most studies rely on popular optimization algorithms such as GA, PSO, and GWO. However, newer or less explored metaheuristic algorithms—such as Educational Competition Optimizer (ECO), Escape Optimization Algorithm (ESC), Fata Morgana Algorithm (FATA), Jason Healing Optimization (JHO), Memory, Evolutionary Operator and Local Search-Based Improved Grey Wolf Optimizer (MELGWO), and Starfish Optimization Algorithm (SFOA)—have not been systematically evaluated under the Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error (ITAE) criterion. To address these gaps, this study performs a comparative evaluation of PIDN and FOPI–FOPD controllers on a 2 DOF QCM. Additionally, the performance of six distinct optimization algorithms is comprehensively analyzed based on the ITAE performance index.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

-

The dynamic responses of PIDN and fractional order FOPI–FOPD controllers are systematically compared on a 2 DOF QCM, highlighting the effectiveness and differences of each control strategy.

-

Six less-explored metaheuristic algorithms (ECO, ESC, FATA, JHO, MELGWO, and SFOA) are applied to tune suspension controllers using the ITAE criterion, offering alternative optimization strategies beyond commonly used methods like PSO and GA.

-

The simulation results are assessed based on the ITAE performance metric, and the effectiveness of different controller–optimizer combinations is analyzed and discussed in detail to offer practical insights for future controller design in active suspension systems.

Paper organization

This paper is structured to help the reader follow the study in a clear and logical manner. Section Introduction provides an overview of the historical development and significance of vehicle suspension systems, summarizes existing literature, and outlines the motivation and scope of this research. Section Materials and methods presents the mathematical formulation of the quarter car active suspension model, along with a detailed explanation of the employed control strategies and optimization algorithms. The optimization methods used for controller parameter tuning are also discussed in this section. Section Simulation and results describes the simulation setup and provides a comparative performance analysis of the proposed methods against conventional approaches. The results are presented clearly using tables and graphical illustrations. Section Discussion offers an interpretation of the findings, evaluates the strengths and limitations of the methods, and discusses potential directions for future research. Finally, Sect. Conclusion concludes the study by summarizing its key contributions and highlighting its importance in improving active suspension system performance.

Materials and methods

This section presents a detailed description of the mathematical model of the quarter car active suspension system, the controller structures, and the parameter optimization process used in this study. The system was modeled using the MATLAB/Simulink environment, and two controller types—PID with filter (PIDN) and Fractional Order PI–PD (FOPI–FOPD)—were implemented. These controllers were tuned using six different metaheuristic algorithms (ECO, ESC, FATA, JHO, MELGWO, and SFOA) under the ITAE performance index. The section elaborates on the system dynamics as well as the fundamental working principles of the selected optimization techniques.

Quarter car active suspension model

Automotive suspension systems play a vital role in optimizing both ride comfort and road handling. These systems are generally categorized into three types: passive, semi-active, and active suspensions. Among them, active suspension systems offer superior performance compared to conventional passive systems, as they can dynamically adjust damping and stiffness values through the application of external forces. The QCM is a simplified representation widely used in the mathematical modeling of vehicle suspension systems. This model represents only one wheel of the vehicle and includes components such as the sprung mass, unsprung mass, spring, and damper40,41. The QCM provides a practical framework for developing, testing, and comparing control algorithms due to its reduced complexity and computational efficiency.

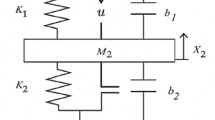

In this study, the active suspension system is analyzed based on the QCM. The dynamic behavior of the system is described using differential equations, and the control and optimization procedures are implemented accordingly. A schematic representation of the QCM used in the simulations is presented in Fig. 2.

The quarter car active suspension model consists of two degrees of freedom (2 DOF), representing the vertical displacement of the vehicle body (zcar) and the wheel (zwheel). The system is modeled using linear spring and damper elements, supplemented by an active suspension force42. The equations of motion for the sprung and unsprung masses are given in Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively:

The variables and parameters used in the model are defined as follows:

-

\(\:{m}_{car}\): Mass of the vehicle body (kg),

-

\(\:{m}_{wheel}\): Mass of the wheel and suspension assembly (kg),

-

\(\:{k}_{s}\): Suspension spring stiffness coefficient (N/m),

-

\(\:{k}_{t}\): Tire stiffness coefficient (N/m),

-

\(\:{d}_{s}\): Suspension damping coefficient (Ns/m),

-

\(\:{f}_{a}\): Active suspension force (N),

-

\(\:{z}_{car,}{\:z}_{wheel},\:{z}_{road}:\) Vertical displacements of the vehicle body, wheel, and road surface, respectively (m).

These differential equations represent the dynamic behavior of the system and can be reformulated into a state-space model for controller design and simulation purposes.

To facilitate effective control and analysis of the system dynamics, the equations of motion are transformed into the state-space form. Accordingly, the state-space representation of the quarter car suspension system is derived as follows.

where the state vector \(\:x\left(t\right),\) input vector \(\:u\left(t\right)\), and output vector \(\:y\left(t\right)\) are defined as:

The system matrices are given by:

In this model, the output vector \(\:y\left(t\right)\) includes the vertical displacements of both the wheel and the car body, which are the primary quantities of interest for ride comfort and road handling evaluations.

Controllers

Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controllers are widely used feedback control mechanisms that are effective in both linear and nonlinear systems43. Due to their simple structure and robust performance, PID controllers have been applied extensively in industrial and automotive control systems. The standard form of the PID controller in the Laplace domain is given in Eq. (21)44:

Here, \(\:{K}_{P}\), \(\:{K}_{I}\), and \(\:{K}_{D}\) denote the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively.

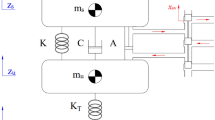

The PIDN controller is a modified version of the classical PID controller. In this structure, the term “N” refers to the derivative filter coefficient, which plays a critical role in attenuating high-frequency noise that typically arises in real-time control systems45. By integrating this filter, the PIDN controller enhances stability and responsiveness, particularly in noisy or nonlinear systems. The transfer function of the PIDN controller, considering the derivative filter, is expressed as in Eq. (22):

As illustrated in Fig. 3, the PIDN controller architecture combines classical PID components with a first-order low-pass filter applied to the derivative term, thereby improving robustness and performance in practical implementations.

Fractional Order PI (FOPI) and PD (FOPD) controllers are generalized and more flexible extensions of the classical PI and PD controllers46. These controllers are particularly well-suited for systems exhibiting slow or complex dynamics, offering greater tunability and robustness in control design47. The combined structure of the FOPI and FOPD controllers is illustrated in Fig. 4, and its transfer function is defined in Eq. (23):

In this expression, λ and µ represent the fractional orders of integration and differentiation, respectively. In this study, the feedback signal is derived from the vertical displacement of the quarter vehicle body mass (zcar), which corresponds to one-fourth of the total vehicle body mass. The road profile (zroad ) is used as the reference input. The output of both the PIDN and FOPI–FOPD controllers is the control force (fa ), which is applied back to the system as an actuation signal.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the control system, several performance criteria can be utilized. Among these, the ITAE is a widely accepted metric in the literature, especially for assessing the time-domain performance of control systems. ITAE emphasizes long-duration errors more heavily, thereby encouraging faster settling and reduced oscillations48,49. A lower ITAE value indicates a more effective control response50,51. The ITAE is defined mathematically in Eq. (24):

where: t represents time, e(t) is the error between the system output and the reference input, \(\:{t}_{sim}\) is the total simulation duration.

In the literature, apart from ITAE, there are also other error functions. Regardless of which technique is used for comparison, the best-performing technique and method ultimately remain the same.

Optimization algorithms

In recent years, metaheuristic optimization algorithms have gained considerable attention in control system tuning due to their flexibility, gradient-free nature, and ability to solve complex, nonlinear, and multimodal problems. These algorithms are particularly well-suited for optimizing parameters in dynamic systems where traditional optimization methods often struggle with local minima and computational inefficiency.

This study employs six different metaheuristic algorithms to optimize the controller parameters of the quarter car active suspension model: ECO, ESC, FATA, JHO, MELGWO, and SFOA. These algorithms were selected not only for their theoretical foundations but also for their diversity in exploration and exploitation strategies.

Each algorithm attempts to minimize the ITAE, which serves as the performance index. While all six methods are used under the same simulation and parameter settings, the comparative results suggest that the ESC provides the most consistent and accurate tuning performance for both the PIDN and FOPI + FOPD controllers.

Furthermore, a brief overview of the six employed algorithms is provided to clarify their selection rationale. ECO leverages competitive learning dynamics and helps avoid early convergence issues. ESC simulates emergency behavior patterns, striking a strong balance between exploration and exploitation. FATA mimics the mirage phenomenon to escape local optima. JHO is based on dynamic healing behavior and adapts well to uncertain environments. MELGWO enhances the classic GWO by incorporating memory and local refinement, improving convergence accuracy. Lastly, SFOA exploits regeneration-inspired search strategies, which offer strong diversification in early iterations. These complementary traits enrich the tuning diversity of the study.

The next subsection provides a detailed explanation of the ESC algorithm, including its working principles, advantages, and its specific impact on the tuning results in this study.

Escape algorithm (ESC)

The Escape Algorithm (ESC) is fundamentally inspired by human behavioral patterns observed during emergency evacuations. This section outlines the conceptual background of crowd evacuation mechanisms and discusses how these real-life behaviors have served as the foundation for the ESC’s design. By incorporating various reaction types—namely calm, herding, and panic—the algorithm skillfully manages the trade-off between exploration and exploitation to address complex optimization challenges52.

Origin of inspiration

This part elaborates on the historical context of evacuation studies and how these insights have shaped the creation of the Escape Algorithm. The conceptual basis of the ESC algorithm stems from a deep examination of the behavioral diversity exhibited by individuals under emergency conditions53. In high-pressure environments, such as natural calamities or human-made disasters, people often respond unpredictably, driven by elements like fear, spatial constraints, and the momentum of the crowd around them54,55,56. These spontaneous behaviors can either aid or obstruct evacuation effectiveness, making them valuable cues for modeling adaptive and intelligent systems. The ESC algorithm encapsulates this real-world complexity by translating human behavior into a metaheuristic computational structure that is capable of solving optimization problems in various domains.

One of the most influential behavioral models behind ESC is the “leader-follower” dynamic57,58, often observed in group evacuations. Within such environments, certain individuals—either by instinct or necessity—take on leadership roles and guide others, while the rest of the group follows based on proximity or perceived trust. This natural hierarchy is algorithmically implemented in ESC by dividing agents into three distinct behavioral roles: calm, herding, and panic-driven59. Each group brings a unique contribution to the search dynamics and collectively steers the algorithm toward global optimization.

-

Calm Crowd: This segment models individuals who maintain composure in the face of stress and respond analytically. In ESC, calm agents are responsible for a strategic and calculated exploration of the solution space. They act similarly to rational evacuees who calmly navigate to the safest and most efficient exits, subtly guiding others with their logical path choices.

-

Herding Crowd: Herding behavior is characterized by people who, lacking clear individual direction, follow the movement of the majority. In the ESC framework, these agents concentrate on the exploitation of promising areas within the search space, mirroring how real individuals often move collectively toward exits perceived as safe, even without firsthand knowledge.

-

Panic Crowd: Representing the unpredictability seen in those overtaken by fear or stress, panic agents introduce a level of randomness into the search process. Their chaotic, often erratic movement patterns not only prevent early convergence to suboptimal solutions but may also lead to discovering hidden or unconventional solutions—just like a panicked individual might stumble upon an alternative escape route in real life.

-

Through this behavioral modeling, ESC integrates the inherent logic found in real-world crowd movement under stress. By channeling the synergy of calm analysis, social conformity, and chaotic exploration, the algorithm creates a well-rounded search methodology. It serves as a testament to how behavioral insights from human nature can be innovatively adapted into technical problem-solving methods.

Algorithm and population initialization

The Escape Algorithm (ESC) aims to emulate the real-time behavior of individuals in a crowded evacuation scenario, where participants must make rapid decisions to reach safety in an ever-changing and uncertain setting. To effectively mimic this behavior, ESC introduces a specialized structure known as the Elite Pool. This pool consists of top-performing candidates, symbolizing the most promising exit routes as perceived by the crowd. The incorporation of this mechanism significantly enhances the algorithm’s ability to conduct broad and effective exploration of the solution space, thus reducing the risk of stagnating in local optima by diversifying the directions considered52.

The algorithm starts with the random generation of a population composed of \(\:N\) individuals. Each individual is encoded as a \(\:D\) -dimensional vector \(\:{x}_{i}=({x}_{i,1},{x}_{i,2}\dots\:,{x}_{i,D})\) The value for each dimension \(\:j\) of the \(\:i\) -th individual is computed using the following Eq. (25):

In this formulation, \(\:{lb}_{j}\) and \(\:{ub}_{j}\) denote the lower and upper limits for the \(\:j-th\) dimension, respectively. This ensures that all individuals are initialized within a defined and permissible space. The random term \(\:{r}_{i,j}\) is drawn from a uniform distribution \(\:U\left(\text{0,1}\right)\), symbolizing the inherent unpredictability of decision-making in an evacuation environment, where individuals choose paths based on partial or misleading information.

Once the initial population is formed, each individual’s quality or suitability is assessed through a fitness function \(\:{f}_{i}=f\left({x}_{i}\right)\). After evaluation, the entire population is sorted based on their fitness values in ascending order. The best-performing individuals—the ones offering the most promising paths—are selected and placed into the Elite Pool, denoted as follows Eq. (26):

These elite members act as pivotal guides in the ongoing optimization process. Much like how evacuees identify and gravitate toward visible or perceived exits, the Elite Pool provides valuable reference points that shape the movement and decisions of the broader population in future iterations. This mechanism not only steers the search towards high-quality solutions but also preserves the diversity required for effective global optimization.

Panic index and iterative dynamics

In the ESC algorithm, the optimization process is modeled to mirror the dynamic evolution of individual behaviors throughout an evacuation scenario. Each step in the iteration cycle adjusts the behavior of individuals based on their assigned roles: calm, herding (conforming), or panic-driven. These classifications are meant to reflect how real people might respond differently under the escalating pressure of an emergency situation52.

To simulate how levels of panic shift over time during an evacuation, ESC introduces a Panic Index, denoted as \(\:P\left(t\right)\), which is computed at the beginning of every iteration \(\:t\). The calculation of this index is defined as Eq. (27):

Here, \(\:T\) represents the total number of iterations in the optimization process. The panic index functions as a dynamic parameter that modulates the overall emotional state of the simulated crowd. A higher value of \(\:P\left(t\right)\) reflects a scenario with greater levels of anxiety and disorder, typically seen in the early phases of an evacuation when individuals are uncertain and the situation is rapidly unfolding.

As the number of iterations increases, the value of \(\:P\left(t\right)\)gradually declines, symbolizing how individuals adapt to the environment and begin making more informed decisions. This transition from chaos to order is essential for mimicking real-world behavior, where initial panic can slowly give way to more organized evacuation efforts as exits become visible and group behavior becomes more coordinated.

The panic index, therefore, not only introduces time-dependent variability into the algorithm but also ensures a realistic simulation of crowd psychology over time. This allows ESC to adaptively balance exploration and exploitation across the search process, leading to more efficient problem-solving.

Exploration phase

During the exploration phase, when \(\:t\le\:\frac{T}{2}\) (\(\:T\) is the maximum number of iterations of the algorithm, and t is the current number of iterations), the population is divided into calm, conforming, and panic groups based on their fitness levels. Specifically, the population is sorted in ascending order of fitness, and individuals are stratified into three groups according to the proportions,\(\:\:c=0.15\),\(\:h=0.35\),and \(\:p=0.5\) for the calm, conforming, and panic groups, respectively. This stratification reflects the varied responses of individuals in a crowd during an evacuation, where some remain calm, others conform to the group’s behavior, and some panic52.

In the early phase of the ESC algorithm—specifically when the current iteration count \(\:t\le\:\frac{T}{2}\), where \(\:T\) denotes the maximum total iterations—the population is strategically divided to simulate the diverse behavioral responses observed during real-life emergency evacuations. This division helps replicate how people naturally react under stress: some remain level-headed, others follow the majority, and some succumb to panic.

To accomplish this, all individuals in the population are ranked based on their fitness values in ascending order. Once sorted, the algorithm categorizes the individuals into three distinct behavioral subgroups: calm, conforming, and panic. The segmentation is guided by predefined proportions that mimic real-world scenarios:

-

Calm Group (\(\:c=0.15\)): Represents the top 15% of the population with the best fitness scores—those who remain rational and strategic under pressure.

-

Conforming Group (\(\:h=0.35\)): Comprises the next 35% of individuals, reflecting those who tend to follow others, often due to uncertainty or lack of independent information.

-

Panic Group (\(\:p=0.5\)): Encompasses the remaining 50%, modeling the erratic and unpredictable behavior of those overwhelmed by fear or confusion.

This structured grouping allows the ESC algorithm to simulate the heterogeneity of human decision-making during a crisis. The calm group tends to guide the direction of exploration, using methodical and logical movement. The conforming group enhances the algorithm’s ability to exploit promising areas by clustering around strong candidates. Meanwhile, the panic group introduces necessary chaos and variability, helping the algorithm avoid becoming trapped in local optima.

By mirroring how real people behave under duress, this stratified approach ensures a more dynamic and effective exploration phase, setting the stage for a balanced and adaptive search strategy as the algorithm progresses.

Calm group update

Members of the calm group exhibit logical and composed behavior, emulating individuals who make informed decisions during evacuations. Their movements are directed toward a central consensus point \(\:{C}_{j}\), which reflects the average decision or direction preferred by the group in the \(\:j-th\) dimension. The position of each individual in this group is updated using Eq. (28).

Here, \(\:{C}_{j}\) represents the centroid of the calm group’s positions in the \(\:j-th\) dimension—essentially the mean location of all calm individuals along that axis. The term \(\:{v}_{c,j}\) is a variation vector described in Eq. (29), which incorporates controlled randomness:

where \(\:{R}_{c,j}\) is a randomly selected point within the positional boundaries of the calm group in the \(\:j-th\) dimension. This random position is calculated by Eq. (30):

In this Eq. (30), \(\:{r}_{min,j}^{c}\) and \(\:{r}_{max,j}^{c}\) denote the minimum and maximum values observed in the calm group for the given dimension. The adjustment term \(\:{\varepsilon}_{j}\) is defined as Eq. (31):

This small perturbation simulates slight variations in decision-making, allowing for more natural and nuanced exploration behavior.

Moreover, the binary variable \(\:{m}_{1}\) follows a Bernoulli distribution, taking values of 0 or 1 with equal probability. This stochastic mechanism imitates the selective movement of individuals in crowded environments, where not every directional component can be updated due to constraints like congestion or obstruction. The adaptive weight \(\:{w}_{1}\), calculated based on a Lévy distribution (detailed in Sect. 3.6), determines the magnitude of the step taken during exploration. This design allows the calm group to gradually refine their positions toward optimal regions while maintaining enough variability to escape stagnation.

Figure 5 visually illustrates how members of the calm group update their positions over time, progressively aligning their actions toward collective consensus while maintaining subtle flexibility in movement.

Updated schematic of the Calm Group52.

Herding group update

Individuals in the herding group exhibit behavior that is influenced by both calm and panic-driven individuals. Their updates are guided by a blend of attraction to rational behavior and unpredictable shifts, reflecting a crowd-following tendency often observed during evacuations. The new position of each herding individual is determined by several factors. First, there is a pull toward the calm group’s center \(\:{C}_{j}\), representing logical guidance. Simultaneously, there’s also an influence from a randomly selected individual in the panic group, denoted as \(\:{x}_{p,j}\), which introduces an element of unpredictable behavior into their movement.

These influences are scaled by two separate adaptive weights, \(\:{w}_{1}\) and \(\:{w}_{2}\), both generated using Lévy distributions to simulate step size variability during exploration. The calm influence is modulated by \(\:{w}_{1}\), while \(\:{w}_{2}\) controls the weight of the panic-based movement. Additionally, binary variables \(\:{m}_{1}\) and \(\:{m}_{2}\), generated from independent Bernoulli distributions, determine whether each influence is applied in a given dimension, allowing partial updates and modeling the incomplete behavioral shifts that often occur in dense or chaotic crowd environments.Another crucial component is the variation vector \(\:{v}_{h,j}\) , which introduces local randomness. This vector is constructed by taking the difference between a random position The \(\:{r}_{min,j}^{h}\) within the herding group’s bounds and the individual’s current position \(\:{x}_{i,j}\), and then adding a slight perturbation \(\:{\varepsilon}_{j}\), where \(\:{\varepsilon}_{j}\) is obtained by dividing a normally distributed random number \(\:{z}_{j}\sim N\left(\text{0,1}\right))\) by 50. The random position \(\:{R}_{h,j}\) is calculated by selecting a point within the range defined by the minimum and maximum values of the \(\:j-th\) dimension for all members of the herding group, scaled by a uniform random factor. This carefully crafted combination of influences allows herding agents to move with a balance of guidance and unpredictability. Their behavior mimics real-world crowd dynamics, where individuals often oscillate between following rational leaders and reacting to surrounding panic. A visual example of this updating mechanism is provided in Fig. 6.

Updated schematic of the herding crowd52.

Panic group update

Individuals in the panic group exhibit the most erratic and unpredictable behavior within the ESC framework. Their movement reflects high uncertainty and rapid reactions, as they explore the solution space under the influence of both perceived optimal exits and random stimuli—similar to how panicked individuals might impulsively respond to their environment during an actual evacuation. Each panic agent adjusts its position by considering two primary influences. The first comes from a randomly selected elite individual, drawn from the Elite Pool, denoted as \(\:{E}_{j}\). This elite reference represents a potential escape route that a panic-driven individual may instinctively move toward. The second influence stems from a randomly chosen individual within the overall population, \(\:{x}_{\text{rand,}j}\), which introduces an element of randomness and allows panic agents to potentially deviate in new directions.

These influences are weighed by using two adaptive step sizes, \(\:{w}_{1}\) and \(\:{w}_{2}\), both derived from Lévy distributions. These weights control the magnitude of each directional component and ensure varied movement scales across iterations. Additionally, two binary variables, \(\:{m}_{1}\) and \(\:{m}_{2}\), are generated using Bernoulli distributions to determine whether each influence is applied, allowing for partial updates in dimensions—capturing the fragmented and inconsistent nature of decision-making under stress. To further diversify movement, a variation vector \(\:{v}_{p,j}\) is incorporated. This vector is formed by calculating the difference between a randomly generated position \(\:{R}_{p,j}\) within the panic group’s bounds and the current position \(\:{x}_{i,j}\), and then adding a small perturbation term \(\:{\varepsilon}_{j}\). The position \(\:{R}_{p,j}\) is determined by selecting a random point between the minimum and maximum values of the \(\:j-th\) dimension for the panic group, scaled by a uniform random factor. The adjustment term \(\:{\varepsilon}_{j}\) introduces fine-grained randomness and is computed by dividing a standard normally distributed variable \(\:{z}_{j}\) by 50.

Through this combined influence of elite guidance, population-level randomness, and chaotic variability, panic agents ensure that the algorithm does not get trapped in local optima. Their unpredictable behavior allows the search to escape stagnation and continue exploring new, potentially better regions of the solution space. Figure 7 illustrates how the panic group’s update mechanism operates across iterations.

Panic crowd update schematic52.

Exploitation phase

Once the iteration count exceeds half of the maximum limit—specifically when the algorithm passes \(\:\frac{T}{2}\)—it transitions from exploration to exploitation. In this later phase, all individuals in the population are treated as calm agents. The primary goal now becomes refinement: rather than searching broadly, the algorithm begins to narrow its focus, improving the quality of existing promising solutions by adjusting positions more precisely.

During this stage, the movements of individuals are directed toward both the best solutions discovered so far and other randomly selected agents from the population. This strategy mimics the real-life tendency of a crowd gradually converging toward clearly identified exits as panic diminishes and people begin to follow more deliberate and optimized paths. To carry out this behavior, each individual updates their position by combining two influences. One influence comes from a randomly selected elite member, representing a known successful direction or exit, and the other influence comes from a randomly chosen individual in the overall population, introducing diversity and preventing premature convergence. These directional movements are modulated by adaptive weights, \(\:{w}_{1}\) and \(\:{w}_{2}\), each controlling the scale of movement, and two binary variables, \(\:{m}_{1}\) and \(\:{m}_{2}\), which determine whether each component is applied. These binary values are generated using Bernoulli distributions, simulating the partial decision-making process where not all factors influence behavior equally.

This fine-tuning mechanism ensures that the population collectively shifts toward optimal regions in the solution space, drawing closer to elite solutions while still maintaining a degree of randomness. The dynamic interaction between structured improvement and stochastic variation reflects a real-world evacuation’s final moments, where individuals begin to move with more purpose and alignment.

Figure 8 visually demonstrates how the population is updated in this exploitation phase, showing the gradual convergence pattern as the algorithm hones in on the best outcomes.

Population update schematic in the exploration phase52.

Adaptive lévy weights and behavioral dynamics simulation

To dynamically modulate the intensity and scale of individual movements throughout the optimization process, the ESC algorithm integrates adaptive Lévy weights. These weights are instrumental in emulating the spectrum of behavioral transitions observed in evacuation scenarios, ranging from erratic exploration to methodical convergence. By adjusting the step sizes in accordance with algorithmic progress, the ESC framework mirrors the psychological evolution of a crowd under duress. For each dimensional component \(\:j\), the corresponding Lévy weight is computed as the ratio of two normally distributed variables. The numerator follows a normal distribution with zero mean and variance \(\:{\sigma\:}^{2}\), while the denominator is drawn from a standard normal distribution and raised to the reciprocal of a dynamically adjusted exponent \(\:\beta\:\). The scaling parameter \(\:\sigma\:\) is derived from a formulation involving the Gamma function, incorporating \(\:\beta\:\), and is designed to preserve the statistical properties of a Lévy flight distribution, thereby ensuring a heavy-tailed step size behavior conducive to both global and local search capabilities.

The exponent \(\:\beta\:\), which governs the degree of tail heaviness in the Lévy distribution, is not held constant but evolves over time to reflect the algorithm’s transition from exploration to exploitation. Initially anchored at a base value consistent with empirical studies—particularly those employed in algorithms such as Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO)— \(\:\beta\:\) gradually increases as a sinusoidal function of the current iteration. This adjustment facilitates the natural tapering of exploratory behavior and the emergence of fine-grained search patterns as the algorithm approaches convergence.

Specifically, lower values of \(\:\beta\:\) during early iterations enable the algorithm to perform large and frequent exploratory jumps, akin to the disordered movements of a panicked crowd. As the search progresses, the increasing \(\:\beta\:\) values yield smaller, more deliberate steps, effectively simulating the rational and coordinated behavior that typically emerges in the latter stages of an evacuation. This behavioral emulation not only enhances the realism of the algorithmic model but also strengthens its capacity for avoiding local optima while achieving high-precision convergence.

Fitness evaluation and elite pool update

In each iteration of the ESC algorithm, the fitness of every updated individual is reassessed to determine the quality of the newly proposed solution. This assessment is conducted through a greedy selection mechanism, whereby the current solution is compared against its updated counterpart, and the superior one is retained for subsequent iterations.

The fitness of an individual at its new position is calculated using the predefined objective function. If this new fitness value yields a better outcome—specifically, a lower value in the context of a minimization problem—then the individual’s position is updated to the new state. Conversely, if the new solution does not improve upon the existing one, the original position is preserved. This strategy ensures that the population consistently progresses toward more optimal regions of the solution space, while avoiding regressions that could hinder convergence.

Formally, each individual’s position is updated based on a conditional rule: the new position is adopted only if its corresponding fitness is superior to the previous one. This approach aligns with classic exploitation strategies in evolutionary algorithms, facilitating efficient refinement without sacrificing solution quality.

Concurrently, the Elite Pool—comprising the top-performing individuals within the population—is refreshed at every iteration. This elite subset is dynamically maintained to always represent the best solutions discovered to date. Functioning as a collective memory of optimal paths or exits, the Elite Pool not only preserves high-quality solutions but also acts as a strategic guide for the population’s future movements. By consistently updating this reference set, the algorithm strengthens its capacity to navigate toward global optima, thus improving both accuracy and convergence speed.

If the newly computed fitness value fi new is lower than the previous fitness \(\:{f}_{i}\), indicating a superior solution in the context of minimization, the position \(\:{x}_{i}\) is updated accordingly; otherwise, it remains unchanged. This approach ensures monotonic non-degradation in the fitness landscape over successive iterations, as no worse solutions are accepted. Moreover, at each iteration, the set of top-performing individuals is used to update the Elite Pool \(\:E\), which retains the most promising solutions discovered thus far. This elite archive serves as a guiding reference for the swarm, facilitating convergence toward globally optimal regions of the search space while preserving solution diversity.

Computational complexity

This section outlines the computational burden associated with the ESC algorithm. Its overall complexity is primarily influenced by two stages: the initial population setup and the iterative optimization process that involves fitness computation, sorting, and solution updates. Let \(\:N\) be the number of agents, \(\:T\) the maximum iteration count, and \(\:D\) the problem’s dimensionality. During initialization, where each agent is defined as a vector of \(\:D\) dimensions, the time complexity is \(\:O(N\times\:D)\). Evaluating the fitness values across all individuals incurs an additional \(\:O(N\times\:D)\) cost. Sorting the population based on fitness requires \(\:O(N\times\:logN)\), assuming a comparison-based sorting method.

Within each iteration, the population is categorized into calm, herding, and panic groups, and every agent’s position is updated accordingly. Updating the population takes \(\:O(N\times\:D)\), and reevaluating fitness again adds \(\:O(N\times\:D)\). Including the sorting step, each iteration results in a total complexity of \(\:(N\times\:D+NlogN)\). Thus, across TTT iterations, the ESC algorithm’s overall complexity becomes \(\:O(T\times\:N\times\:\left(D+logN\right))\). To contextualize this, ESC is compared with the computational profiles of the Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA)60 and Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO)61. According to their respective formulations, SMA shares the same asymptotic complexity as ESC, i.e., \(\:O(T\times\:N\times\:\left(D+logN\right))\), due to its inclusion of both fitness evaluations and ranking mechanisms. In contrast, HHO has a simplified computational model of \(\:O(T\times\:N\times\:D)\), focusing on position updates without incorporating sorting procedures or additional structural adaptations. In conclusion, the ESC algorithm, by integrating sorting and structured group-based updates, has a slightly higher theoretical cost than HHO but offers enhanced control and adaptability in complex optimization tasks. While ESC and SMA are well-suited for structured problem landscapes requiring additional internal coordination, HHO offers advantages in scenarios demanding rapid convergence with minimal overhead. The procedural flow of ESC is depicted in Fig. 9. The step-by-step process of the ESC algorithm is illustrated in the pseudocode presented in Fig. 10.

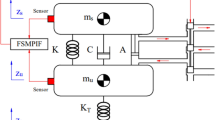

Simulation and results

The simulation of the proposed system was performed in the MATLAB/Simulink environment using both graphical and script-based modeling tools. Figure 11 illustrates the simulation model of the quarter car active suspension system developed for this study. The system parameters used in the active quarter car suspension model are selected based on the typical ranges reported in the literature. The specific values adopted in this study, along with corresponding minimum and maximum ranges observed in previous works, are summarized in Table 2.

The system is controlled using two different controller types: PIDN and FOPI + FOPD. The controller parameters are optimized using six distinct metaheuristic algorithms: ECO, ESC, FATA, JHO, MELGWO, and SFOA. The search space for the optimization is defined as follows:

-

For all gains: \(\:-100\le\:{K}_{P}\:,\:{K}_{I}\:,\:{K}_{D}\:\le\:100\)

-

For the filter coefficient: \(\:0.001\le\:N\le\:\)5000.

-

For fractional orders: \(\:0.001\le\:\lambda\:\:,\mu\:\le\:2\)

Each algorithm is executed with a population size of 50 and 100 iterations, totaling 5000 evaluations per algorithm. The PIDN controller consists of 4 tuning parameters (KP, KI, KD and N), while the FOPI + FOPD controller includes 6 parameters (KP1, KI1, λ, KP2, KD2 and µ). The ITAE performance index is used as the objective function for optimization. In total, 12 different controller-algorithm combinations (2 controllers × 6 algorithms) are tested and compared.

The road disturbance profile depicted in Fig. 12 spans from + 0.10 m to − 0.15 m, representing typical real-world surface irregularities such as road bumps and potholes. Positive displacement values correspond to elevation changes (bumps), while negative values indicate surface depressions (dips). This excitation signal has been deliberately designed to reflect dynamic and asymmetric road conditions, enabling a realistic evaluation of the suspension system’s ability to maintain ride comfort and stability. Such profile magnitudes are commonly encountered in practical scenarios and have been adopted in various benchmark studies for active suspension testing. Therefore, the proposed road profile is both realistic and sufficient to test the dynamic responsiveness and robustness of the controllers under varying surface conditions.

Table 3 presents the optimization results of the PIDN controller using six different metaheuristic algorithms. The best performance, in terms of the ITAE value, was obtained using the ESC, yielding an ITAE of 0.11337. It is worth noting that the results obtained by all algorithms are relatively close to each other, indicating the robustness and stability of the PIDN structure across different optimization techniques.

In Table 4, the results of the FOPI + FOPD controller optimized with the same set of algorithms are provided. For each algorithm, the best-performing parameter set is Listed. Among all, the ESC algorithm again achieved the lowest ITAE value of 0.066154, which is significantly lower than the best result achieved with PIDN. This observation highlights the superior performance of the FOPI + FOPD controller structure in handling the dynamic response of the quarter car system. It is evident that fractional order controllers provide finer tuning capability, leading to improved time-domain performance metrics.

As the ESC achieved the best ITAE performance among all tested methods, its optimal parameter set was used to simulate the final system response. The resulting output of the PIDN-controlled active suspension system is illustrated in Fig. 13. This figure presents four critical time-domain plots: body acceleration, body velocity, body displacement in comparison with the road profile, and the control error signal. The first subplot demonstrates the vertical acceleration of the vehicle body, which is directly related to passenger comfort. The response indicates that the system effectively limits high-amplitude oscillations following road disturbances. The second subplot, representing body velocity, confirms the ability of the PIDN controller to rapidly attenuate oscillations and return to equilibrium after external excitations. The third subplot compares the vehicle body position (solid line) with the reference trajectory derived from the road disturbance (dotted line). The close overlap between the two curves suggests that the controller is capable of closely tracking the road profile, minimizing suspension travel deviations. The final subplot displays the control error signal, which remains minimal and stable throughout the simulation period. This indicates high control accuracy and fast settling time. Overall, the ESC-optimized PIDN controller demonstrates effective suppression of road-induced disturbances and provides a smooth ride experience. The performance confirms the algorithm’s capability to tune control parameters in a way that optimizes both stability and comfort.

In addition to the body dynamics, the wheel-level response of the system was also analyzed using the ESC-optimized PIDN controller. Figure 14 presents the time-domain simulation results for wheel acceleration, wheel velocity, wheel displacement in relation to the road surface, and the accumulated ITAE performance index over time. The first plot shows that the wheel acceleration exhibits sharp spikes in response to abrupt changes in the road profile. Despite these high-frequency disturbances, the system is able to quickly stabilize, indicating the effectiveness of the damping and control force applied. The second plot demonstrates the wheel velocity behavior, where initial disturbances are followed by rapid attenuation, illustrating the controller’s responsiveness. The third plot compares the road disturbance (dotted line) with the actual wheel position (solid line). While there is a noticeable deviation at the moment of road excitation, the wheel position quickly converges back, which highlights the suspension system’s ability to absorb shocks effectively and protect the vehicle chassis from excessive vibration. The final plot displays the cumulative ITAE value over the course of the simulation. The curve shows a gradual increase with pronounced steps at moments of significant disturbance. This cumulative representation confirms the ability of the controller to minimize time-weighted error, especially after the system stabilizes following each road event. These results emphasize that the ESC-optimized PIDN controller provides not only robust body-level performance but also effective wheel control, ensuring both comfort and mechanical stability under varying road conditions.

To further assess the impact of different optimization algorithms on system behavior, Fig. 15 presents the body displacement response of the PIDN controller optimized using all six metaheuristic methods. The reference road profile is depicted by a dotted line, while the controller outputs for each algorithm are shown as colored solid lines. As can be observed in the plot, all displacement curves practically overlap with one another, making them visually indistinguishable. This observation aligns with the numerical findings summarized in Table 3, where the ITAE values for different algorithms were remarkably close. The negligible variance among the displacement responses confirms that, despite differences in optimization mechanisms, each algorithm successfully identified a control parameter set that yields nearly identical performance for the PIDN controller. This consistency also highlights the robustness and stability of the PIDN controller structure when subjected to optimization via various metaheuristic techniques. Regardless of the algorithm used, the PIDN controller maintained accurate trajectory tracking and minimized body oscillations under variable road conditions.

Figure 16 illustrates the time-domain simulation results for the vehicle body when the system is controlled using a FOPI + FOPD controller tuned via the ESC. The subplots include body acceleration, velocity, displacement relative to the road profile, and the tracking error. The acceleration response shows that the system reacts sharply but quickly stabilizes after encountering road disturbances. The velocity curve confirms that the controller rapidly damps out oscillations and maintains vehicle stability. In the third plot, the body position closely follows the reference road displacement signal, with minimal deviation even during rapid profile changes. The error signal remains close to zero after each disturbance, indicating precise and responsive control. These results demonstrate that the FOPI + FOPD controller not only effectively tracks the desired trajectory but also provides smooth control with reduced overshoot and fast settling. Figure 17 presents the wheel-level simulation results for the same controller configuration. The plots display wheel acceleration, velocity, displacement relative to the road, and the cumulative ITAE value.

The wheel acceleration and velocity graphs reveal that the system undergoes high-frequency oscillations immediately following road disturbances. However, the oscillations decay quickly, showing that the suspension system is actively absorbing the road impact. The wheel displacement plot, compared with the road input, shows oscillatory but bounded behavior, suggesting that the controller is effectively managing road-induced vibrations. The cumulative ITAE curve increases gradually, with sharper rises corresponding to points of significant disturbance, indicating how performance varies over time. These results suggest that while the FOPI + FOPD controller offers precise body control, its interaction with the wheel dynamics involves active energy absorption and damping. The controller’s ability to manage both ride comfort and stability is evident from its simultaneous control of body and wheel dynamics. Figure 18 compares the tracking performance of various optimization algorithms used with the FOPI + FOPD controller by displaying the body displacement response alongside the reference road profile. Unlike the PIDN controller results, where differences between algorithms were barely noticeable, the variations here are more distinct. Specifically, the trajectory obtained using the FATA shows a slight but visible deviation from the reference signal.

The remaining algorithms—ECO, JHO, MELGWO, and SFOA—closely follow the reference path, but subtle differences can still be observed in their transient responses. Among all the tested methods, the ESC once again achieved the best tracking performance, with its output almost entirely overlapping the reference input. When the results are evaluated in terms of road disturbance tracking, it becomes evident that the PIDN controller performs worse than the FOPI + FOPD controller, especially in scenarios involving abrupt or nonlinear road changes.

This highlights the enhanced adaptability and responsiveness of fractional-order control structures in handling complex dynamics. These observations confirm that the FOPI + FOPD controller is more sensitive to parameter tuning, and algorithmic efficiency plays a greater role in achieving optimal control. As such, the selection of a robust optimization technique like ESC becomes more critical when using advanced control structures like fractional-order controllers.

Figures 19 and 20 present the convergence curves of all six optimization algorithms used to tune the PIDN and FOPI + FOPD controllers, respectively. These curves illustrate the evolution of the best fitness values (i.e., ITAE) over 100 iterations. For clarity, each figure includes a magnified view that highlights the final stages of convergence, where the performance of the algorithms becomes more distinguishable.

In Fig. 19, which corresponds to the PIDN controller, the majority of the algorithms converge rapidly within the first 10 to 20 iterations. After this initial phase, improvements become marginal, and most curves plateau. Nevertheless, the ESC consistently achieves the lowest ITAE value, confirming its superior tuning capability even within a relatively small number of iterations. This reflects both its efficiency in exploration and effectiveness in fine-tuning control parameters for a relatively simpler control structure like PIDN. On the other hand, Fig. 20, associated with the FOPI + FOPD controller, displays a more gradual convergence trend for most algorithms. This is expected given the increased complexity and higher dimensionality of the parameter space for fractional-order controllers. Despite the slower convergence, ESC again outperforms the other methods by reaching the best ITAE value, demonstrating its robustness and adaptability in complex optimization landscapes. The curve for ESC shows both steady progress and early stabilization, indicating a strong balance between exploration and exploitation throughout the optimization process. Overall, these convergence curves emphasize the importance of algorithm selection in control system optimization. ESC not only yields the best final results but also shows faster and more stable convergence behavior in both controller structures, making it a highly suitable algorithm for time-critical and performance-sensitive applications in active suspension control.

Discussion

This study focused on enhancing the performance of a quarter car active suspension system through the application of two advanced control structures: the PIDN and the Fractional Order PI plus PD (FOPI + FOPD) controllers. By optimizing the parameters of these controllers using six different metaheuristic algorithms, the goal was to improve vehicle ride comfort by minimizing vibrations and achieving more stable suspension dynamics. A total of twelve unique control configurations were analyzed, combining two controller types with six optimization algorithms. The simulation results reveal that the FOPI + FOPD controller significantly outperformed the PIDN controller in terms of overall time-domain performance, particularly in its ability to track road disturbances with higher accuracy and reduced error. While the ITAE values obtained across different algorithms were generally close, indicating consistent algorithmic performance, the ESC emerged as the most effective method for both controller types, delivering the lowest ITAE values in all cases. It was also observed that simulating the system with various optimization strategies provides valuable insights into the behavior and limitations of each controller structure. The use of ESC not only yielded better final results but also demonstrated faster convergence and stability during optimization. These findings underscore the importance of selecting an appropriate optimization technique when designing intelligent suspension systems. Prior to finalizing the optimization set, several other algorithms were tested, and only the configurations that yielded the best performance are presented in this paper. Taken together, the outcomes of this work confirm that combining fractional-order control with intelligent optimization presents a powerful approach for suspension system tuning. The methodology presented here contributes to the growing body of research on advanced suspension control, offering insights that could be extended to more complex vehicle models or implemented in real-time embedded systems for next-generation ride comfort enhancement.

Conclusion

Road irregularities such as bumps and potholes can significantly reduce passenger comfort during vehicle travel. As a solution, this study proposed the development of more effective active suspension systems by utilizing intelligent control methods. A quarter car suspension model was controlled using two advanced controllers—PID with filter (PIDN) and Fractional Order PI plus PD (FOPI + FOPD)—whose parameters were tuned via six metaheuristic algorithms: ECO, ESC, FATA, JHO, MELGWO, and SFOA. Among these, the FOPI + FOPD controller optimized using the ESC consistently delivered the best overall results.

Compared to a previously published study using a fuzzy logic controller, which exhibited a peak overshoot of approximately 0.7 m at t = 0.5s, the ESC-optimized FOPI + FOPD controller achieved a significantly reduced peak of 0.07 m—representing nearly a tenfold improvement. Similarly, the undershoot value at t = 3.5 s was reduced from − 0.25 to −0.04 in this study. While the original work reported an undershoot of −0.175 at t = 5.5 s, this value was − 0.21 in the current implementation—slightly worse in this instance. At t = 8 s, the maximum overshoot increased marginally from 0.025 m to 0.03 m. However, when comparing the overall settling times across all disturbances (with a threshold of 0.02% for final value convergence), the FOPI + FOPD controller clearly outperformed prior approaches, as visualized in Fig. 1842. These improvements were quantitatively compared with the results reported in42, clearly highlighting the superiority of the ESC-tuned FOPI + FOPD controller in terms of overshoot, undershoot, and settling time.

Previous works predominantly employed fuzzy logic or classical PID controllers. In contrast, this study introduced and tested PIDN and FOPI + FOPD structures, concluding that the FOPI + FOPD controller yields superior performance in nearly all evaluated scenarios. Furthermore, the best tuning results for this controller were obtained using the ESC algorithm, confirming its robustness and optimization capability. These findings highlight the critical importance of controller selection when designing control strategies for mechanical systems such as suspension setups. While optimization algorithms significantly contribute to performance, their impact is meaningful only after the appropriate controller has been chosen. Therefore, an effective suspension system design should follow a structured approach, including (1) the selection of a suitable suspension model, (2) the identification of an appropriate controller structure, and (3) the optimization of controller parameters. This sequential design process is essential to achieve high-performance results in active suspension applications.

As a direction for future work, the proposed control strategies can be extended and validated on more complex suspension configurations, such as half-car or full-car models, which account for additional dynamics like pitch and roll for a more realistic representation of vehicle behavior. Moreover, implementing the controllers on real-time platforms using hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) systems could provide insights into practical feasibility and computational efficiency. Additionally, exploring adaptive or learning-based control strategies may enhance robustness and performance under varying and uncertain road conditions. These extensions would contribute to closing the gap between simulation-based results and real-world implementation in advanced automotive suspension systems.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ACO:

-

Ant colony optimization

- ADP:

-

Adaptive dynamic programming

- AFTC:

-

Active fault tolerant control

- BA:

-

Bat algorithm

- CMA-ES:

-

Covariance matrix adaptation-evolutionary strategy

- DO:

-

Dingo optimization

- DOF:

-

Degree of freedom

- DRLB:

-

Deep reinforcement learning

- ECO:

-

Educational competition optimizer

- ESC:

-

Escape

- FATA:

-

Fata morgana algorithm

- FLC:

-

Fuzzy logic controller

- FRF:

-

Frequency response function

- FOPD:

-

Fractional order proportional-derivative

- FOPI:

-

Fractional order proportional-integral

- FOPID:

-

Fractional order proportional-integral-derivative

- GA:

-

Genetic algorithm

- GSA:

-

Gravitational search algorithm

- GWO:

-

Grey wolf optimization

- HJB:

-

Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman

- IAE:

-

Integral of absolute error

- ISE:

-

Integral square error

- ITAE:

-

Integral of time weighted absolute error

- ITSE:

-

Integral of time square error

- JHO:

-

Jason healing optimization

- LDFC:

-

Linear dynamic feedback control

- LMI:

-

Linear matrix inequality

- LQR:

-

Linear quadratic regulator

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- MELGWO:

-

Memory, evolutionary operator, and local search based improved grey wolf optimizer

- MMO:

-

Min-max optimization

- MSE:

-

Mean squared error

- NMSA:

-

Nelder mead simplex algorithm

- NN:

-

Neural network

- NSGA:

-

Non dominated sorting genetic algorithm

- OFC:

-

Output feedback control

- PI:

-

Proportional-integral

- PID:

-

Proportional-integral-derivative

- PIDN:

-

Proportional-integral-derivative with filter

- PPO:

-

Proximal policy optimization

- PSO:

-

Partial swarm optimization

- QCM:

-

Quarter car model

- RMS:

-

Root mean square

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- SFC:

-

State feedback controller

- SFOA:

-

Starfish Optimization Algorithm

- SMC:

-

Sliding mode controller

- SOF:

-

Static output feedback

- SPEA:

-

Strength pareto evolutionary algorithm

- TRM:

-

Trust region method

- VRFC:

-

Virtual reference feedforward controller

- WO:

-

Walrus optimization

- \(\:{d}_{s}\) :

-

Suspension damping coefficient

- \(\:{f}_{a}\) :

-

Active suspension force

- KD :

-

Derivative gain

- KI :

-

Integral gain

- Kp :

-

Proportional gain

- \(\:{k}_{s}\) :

-

Suspension spring stiffness coefficient

- \(\:{k}_{t}\) :

-

Wheel hardness coefficient

- \(\:{m}_{car}\) :

-

Vehicle body mass

- \(\:{m}_{wheel}\) :

-

Wheel and suspension system mass

- N:

-

Derivative action filter constant

- s:

-

Second

- t:

-

Time

- \(\:{z}_{car}\) :

-

Vertical displacement of the vehicle body

- \(\:{z}_{road}\) :

-

Vertical displacement of the road surface

- \(\:{\:z}_{wheel}\) :

-

Vertical displacement of the wheel

- λ:

-

Fractional integrator order

- \(\:{d}_{s}\) :

-

Suspension damping coefficient (Ns/m)

- e(t):

-

Error

- \(\:{f}_{a}\) :

-

Active suspension force (N)

- \(\:{K}_{D}\) :

-

Derivative gain

- \(\:{K}_{I}\) :

-

Integral gain

- \(\:{K}_{P}\) :

-

Proportional gain

- \(\:{k}_{s}\) :

-

Suspension spring stiffness coefficient (N/m)

- \(\:{k}_{t}\) :

-

Tire stiffness coefficient (N/m)

- \(\:{m}_{car}\) :

-

Mass of the vehicle body (kg)

- \(\:{m}_{wheel}\) :

-

Mass of the wheel and suspension assembly (kg)

- N:

-

Derivative filter

- t:

-

Represents time

- \(\:{t}_{sim}\) :

-

Total simulation duration

- \(\:{z}_{car}\) :

-

Vertical displacements of the vehicle body (m)

- \(\:{z}_{road}\) :

-

Vertical displacements of the vehicle road (m)

- \(\:{z}_{wheel}\) :

-

Vertical displacements of the vehicle Wheel (m)

- λ:

-

Integration fractional order

- μ:

-

Differentiation fractional order

References

Goodarzi, A. & Khajepour, A. Vehicle Suspension System Technology and Design (Springer, 2017).

Al-Ashmori, M. & Wang, X. A systematic literature review of various control techniques for active seat suspension systems. Appl. Sci. 10, 1148 (2020).

Crolla, D., Firth, G. & Horton, D. An Introduction To Vehicle Dynamics (University of Leeds, Department of Mechanical Engineering, 1992).

Savaresi, S. M., Poussot-Vassal, C., Spelta, C., Sename, O. & Dugard, L. Semi-active suspension control design for vehicles (Elsevier, 2010).

Kaldas, M. M. S. Improvement of semi-active suspensions through fuzzy-logic and top mount optimization (Shaker-Verlag, 2015).

Heißing, B. & Ersoy, M. Chassis Handbook, Vieweg & Teubner Verlag (Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, 2011).

M.-B. o. Charleston. What is Mercedes-Benz MAGIC BODY CONTROL. accessed 26.01.2025, (2025). https://www.mercedesbenzofcharleston.com/mercedes-benz-magic-body-control/

Tesla Model S Owner’s Manual. https://www.tesla.com/ownersmanual/models/en_us/GUID-538D748E-6DDF-4910-A898-C17E2B671A77.html (accessed 2025, 26.01.2025).

BMW & Adaptive M Suspension. https://www.bmw.co.uk/en/shop/ls/dp/VDC_Offer_gb (accessed 2025, 26.01.2025).

Idir, A., Bensafia, Y. & Canale, L. Influence of approximation methods on the design of the novel low-order fractionalized PID controller for aircraft system. J. Brazilian Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 46, 1–16 (2024).

Idir, A. et al. PID Controller Design with a New Method Based on Fractionalized Integral Gain for Cruise Control System. Proc. – 24th EEEIC Int. Conf. Environ. Electr. Eng. 8th I CPS Ind. Commer. Power Syst. Eur. EEEIC/I CPS Eur. 1–6 (2024) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/EEEIC/ICPSEurope61470.2024.10751521

Prusty, U. C., Nayak, P. C., Prusty, R. C. & Panda, S. An improved moth swarm algorithm based fractional order type-2 fuzzy PID controller for frequency regulation of microgrid system. Energy Sources, Part A Recover Util. Environ. Eff. 47, 96 (2022).

Nayak, P. C., Nayak, B. P., Prusty, R. C. & Panda, S. Sunflower optimization based fractional order fuzzy PID controller for frequency regulation of solar-wind integrated power system with hydrogen aqua equalizer-fuel cell unit. Energy sources, part A recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 47, 9550–9568 (2025).

Bittencourt, T. C., Fagundes, J. T. & de Oliveira Evald, P. J. D. Enhancing quarter car active suspension performance using Walrus optimization algorithm-based PID controller, in 2024 16th Seminar on Power Electronics and Control (SEPOC), : IEEE, 1–6. (2024).

Nagarkar, M. et al. Design of passive suspension system to mimic fuzzy logic control active suspension system. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 11(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-022-00291-3 (2022).

Dogruer, C. U. Improving ride-comfort of a quarter-car model using modal control, in 2019 7th International Conference on Control, Mechatronics and Automation (ICCMA), : IEEE, pp. 237–242. (2019).

Yuvapriya, T., Lakshmi, P. & Elumalai, V. K. Experimental validation of LQR weight optimization using bat algorithm applied to vibration control of vehicle suspension system. Iete J. Res. 69(11), 8142–8152. https://doi.org/10.1080/03772063.2022.2039079 (2023).

Yakub, F., Muhammad, P., Daud, Z. H. C., Abd Fatah, A. Y. & Mori, Y. Ride comfort quality improvement for a quarter car semi-active suspension system via state-feedback controller, in 2017 11th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), : IEEE, pp. 406–411. (2017).

Jeong, Y., Sohn, Y., Chang, S. & Yim, S. Design of static output feedback controllers for an active suspension system. IEEE Access. 10, 26948–26964 (2022).

Nagarkar, M. P., Bhalerao, Y. J. & Vikhe Patil, G. J. Zaware patil, GA-based multi-objective optimization of active nonlinear quarter car suspension system—PID and fuzzy logic control. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 13, 1–20 (2018).

Manna, S. et al. Ant colony optimization tuned closed-loop optimal control intended for vehicle active suspension system. IEEE Access. 10, 53735–53745 (2022).

Mata, G. T., Mokenapalli, V. & Krishna, H. Performance analysis of MR damper based semi-active suspension system using optimally tuned controllers. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D-J. Automob. Eng. 235, 2871–2884. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544070211004467 (2021).

Mahmoodabadi, M. J. & Nejadkourki, N. Optimal fuzzy adaptive robust PID control for an active suspension system. Aust. J. Mech. Eng. 20, 681–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/14484846.2020.1734154 (2022).

Liu, Y. Y. et al. Online optimal tuning of fuzzy PID controller using grey wolf optimizer for quarter car semi-active suspension system. Adv. Mech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/16878132231219620 (2024).

Florea, A., Cofaru, I., Patrausanu, A., Cofaru, N. & Fiore, U. Superposition of populations in multi-objective evolutionary optimization of car suspensions. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 126, 107026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107026 (2023).

Yan, H., Sun, J., Zhang, H., Zhan, X. & Yang, F. Event-triggered $ H_\infty $ state estimation of 2-DOF quarter-car suspension systems with nonhomogeneous markov switching. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybernetics: Syst. 50 (9), 3320–3329 (2018).

Jin, X. & Wang, J. Modeling and µ Synthesis Control for Active Suspension System of Electric Vehicle, in 2021 5th CAA International Conference on Vehicular Control and Intelligence (CVCI), : IEEE, pp. 1–6. (2021).

Coskun, S. & Ozgur, O. Hybrid Fuzzy Control of Semi-Active Suspension System Using Magnetorheological Damper, in 2021 5th International Symposium on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies (ISMSIT), : IEEE, pp. 141–146. (2021).

Boulaaras, Z., Aouiche, A. & Chafaa, K. PID controller optimized by using Genetic Algorithm for Active Suspension System of a Quarter car, in 2022 19th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), : IEEE, pp. 779–784. (2022).

Hurel, J., Amaya, J., Peralta, J., Alvarado, D. & Flores, F. Particle Swarm Optimization applied on Fuzzy Control: Comparative analysis for an Quarter-car Active Suspension Model, in IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), 2022: IEEE, pp. 1–8. (2022).

Długosz, M. & Skruch, P. Optimization of the Stabilization Problem for the Vehicle Active Suspension System Using Linear Dynamic Feedback Control, in 2022 26th International Conference on Methods and Models in Automation and Robotics (MMAR), : IEEE, pp. 260–263. (2022).

Li, Y., Wang, T., Liu, W. & Tong, S. Neural network adaptive output-feedback optimal control for active suspension systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybernetics: Syst. 52 (6), 4021–4032 (2022).

Jeong, Y., Sohn, Y., Chang, S. & Yim, S. Design of virtual reference feedforward controller for an active suspension system. IEEE Access. 10, 65671–65684 (2022).

Setyawan, N., Mardiyah, N. A., Achmadiah, M. N., Effendi, R. & Jazidie, A. Active fault tolerant control for missing measurement problem in a Quarter car model with linear matrix inequality approach, in 2017 International Electronics Symposium on Engineering Technology and Applications (IES-ETA), : IEEE, pp. 207–211. (2017).

Sejal, S., Kumar, S., Bosch, R. M. U. & Conference, E-M. Study of Anti-Lock Braking System Using GWO Tuned PID Controller, in 2023 IEEE Renewable Energy and Sustainable (RESEM), : IEEE, pp. 1–6. (2023).

Kim, S. R., Kim, C., Shin, S. & Kim, S. W. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Semi-Active Suspension: A Feasibility Study, in 2023 International Conference on Electronics, Information, and Communication (ICEIC), : IEEE, pp. 1–5. (2023).