Abstract

ZnSe nanoparticles (NPs) are employed in multiple fields, including environmental, electronic, and materials science. However, their biological features have not been extensively studied. Thus, this study focused on the biosynthesis of ZnSe nanoparticles using the aqueous extract of Stachys lavandulifolia as the unique origin. Moreover, the biogenic ZnSe NPs were examined using UV–Vis, FTIR, XRD, SEM-EDX, and TEM techniques. The bioactivity of ZnSe NPs was evaluated using various trials. The ZnSe NPs showed a distinct absorbance peak in the UV–visible spectrum at 304 nm. The FTIR revealed the potential functional groups linked to biomolecules participating in the synthesis of ZnSe NPs. SEM and TEM showed that the ZnSe NPs were spherical, with a size range of 10–30 nm. XRD revealed that the crystallite size of the NPs was 15.2 nm, and EDX indicated that their elemental compositions included selenium and zinc in a 40.9:37.0 ratio. The DPPH scavenging potential of ZnSe NPs and plant extract was found to have IC50 values of 16.8 and 35.7 mg/mL, respectively. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity against three MDR pathogens exhibited two-fold potency against P. aeruginosa (NDM-1) compared to K. pneumonia (blakpc) and S. aureus (MRSA). Additionally, plasmid curing tests established resistance disruption in P. aeruginosa (hospital isolate) and K. pneumonia (blakpc). Cytotoxicity tests on the KB cancer and HF normal cell lines, based on IC50 values, showed that ZnSe NPs were equivalent to 23.43 µg/mL and 30.15 µg/mL, respectively. To conclude, the eco-friendly synthesis of ZnSe NPs can meet the essential requirements for therapeutic and preventive uses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanoparticles have been placed at the forefront of research due to their dimensions in the range of 1–100 nm and their unique chemical, physical, and biological characteristics. Metal nanoparticles have also proven helpful in biological and medical applications such as drug delivery, hyperthermia, biosensing, imaging, and gene delivery1. Today, nanotechnology represents a new industrial revolution. However, most techniques involving toxic chemicals, elevated temperatures, and pressure can adversely impact the environment and living organisms. Consequently, green chemistry techniques using plants/bio-molecules have emerged as eco-benign alternatives2. Plant leaf/synthesized metabolite-induced NP fabrication has several advantages over bacterial/fungal methods, such as ease of handling, no nutrient requirement for plant extracts, faster NP formation with maximum yield, and biogenic capping3. Recent efforts have been directed toward using natural compounds for nanomaterials. Secondary metabolites of various plants have been reported to synthesize gold, silver, zinc oxide, copper oxide, palladium, bimetallic, and metal-selenide nanoparticles4,5. Plants synthesize metal nanoparticles due to their reducing capacity through active compounds and their metabolites. Investigations have provided evidence that different phytochemicals (polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenes, polysaccharides, and plant peptides) act as reducing agents during the synthesis of metal nanoparticles by plants. The majority of these plant-derived compounds not only reduce metal ions but also provide stabilization by capping the naked nanoparticles during nucleation and growth, which stabilizes the resulting nanoparticles and prevents agglomeration6.

Zinc selenide nanoparticles (ZnSe NPs) have gained interest recently due to their unique properties and potential applications in optoelectronic devices. Different methods for synthesizing ZnSe NPs include chemical, colloidal, thermal evaporation, laser ablation, and electrochemical processes1,7. However, these approaches often require expensive chemicals, complex procedures, or toxic materials that can harm the environment. To address these concerns, researchers have been investigating alternative methods for NPs synthesis, one such approach being the use of plant extracts and other biological materials to synthesize NPs8,9,10.

Chronic infections, frequently worsened by biofilm development, are a major global cause of death; antibiotic-resistant organisms more often instigate these infections. The deaths resulting from antibiotic-resistant infections rose from 2019 to 2021, greatly exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The ongoing increase in antibiotic-resistant infections poses a public health risk in the 21st century11,12. A promising approach to combating emerging resistant pathogens is employing metal nanoparticles, which have demonstrated potent antimicrobial properties. Nonetheless, the harmful effects of specific nanoparticles on the host have constrained their application as antimicrobial agents. To address this challenge, nanoparticles created via green synthesis have attracted interest. Significantly, medicinal plants and their compounds possess considerable promise for generating a variety of nanoparticles in the medical sector, presenting an optimistic perspective for the future of nanoparticle exploration13. Meanwhile, zinc selenide nanoparticles are the focus and are characterized experimentally and theoretically. Their good biocompatibility and ability to erode gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial biofilms, even antibiotic-resistant ones, make them potential candidates for combating chronic infections14,15.

Stachys lavandulifolia, a plant deeply rooted in the tradition of herbal medicine, has been recognized and utilized by local society for hundreds of years. Its potent therapeutic qualities, steeped in history, have paved the way for addressing infectious diseases. Additionally, S. lavandulifolia is utilized in traditional Iranian medicine to treat infections, asthma, and rheumatism, among other conditions, in the context of medicinal plants16. The primary compounds of S. lavandulifolia include germacrene-D, beta-pinene, alpha-pinene, myrcene, and beta-phellandrene17.

While studies have explored the green synthesis of various nanoparticles, such as copper, silver, and gold, using S. lavandulifolia, there is a lack of comprehensive and systematic research on the bio-assisted synthesis of ZnSe nanoparticles using natural compounds18,19,20,21. Addressing the empirical gap, this study focused on fabricating ZnSe NPs using an aqueous extract of S. lavandulifolia. These nanoparticles are then investigated for their antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activities against three known pathogens with multidrug resistance, including P. aeruginosa (NDM-1), K. pneumoniae (blakpc), and S. aureus (MRSA). The potential impact of this research is significant, as it could lead to the development of new strategies for combating multidrug-resistant pathogens. Furthermore, this study focused on examining resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics carried by plasmids to estimate the effectiveness of the produced ZnSe NPs in plasmid-curing on these pathogens.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and biological equipment

All solvents were of high purity, as archived in the laboratory: sodium selenite and zinc nitrate. 4H2O was purchased from Merck. Bacterial and fungal strains and also the cell lines (oral cancer cell (KB-C152) and human skin fibroblasts (HFFF2-C163)) were obtained from a local collection at Razi Herbal Medicine Research Center, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences. This collection used was generously provided by other investigators from the Pasteur Cell Collection in Tehran, Iran, previously purchased. The culture media and related materials were prepared from Kiazist Company (Hamadan, Iran). The S. lavandulifolia was sourced from the Razi Herbal Medicines Research Center, Herbarium Reservoir, at Lorestan University of Medical Sciences. The systematic department conducts expert-approved plant authentication.

Extraction of water soluble metabolites from S. lavandulifolia.

The aqueous extract of S. lavandulifolia flowers was obtained by a bath-sonication extraction method as described by Singh et al. (2025)22. Briefly, 5 g of powdered dried flower was immersed in 100 mL of deionized water and placed in a bath-sonicator at 55 °C for 120 min. After that, the extract was filtered with Whatman paper No. 2, and the filtrate was used for the synthesis of nanoparticles. Additionally, to examine the bioactivity of plant extract, some of one was dried in an oven at 70 °C.

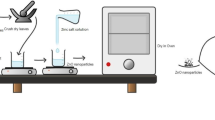

Biosynthesis of ZnSe NPs

ZnSe NPs were synthesized using a biological-based method using an aqueous S. lavandulifolia extract (SL extract). For this, stoichiometric ratios of 30 mL of sodium selenite (1 mM) and 30 mL of zinc nitrate tetrahydrate (1 mM) were mixed in a 200 mL beaker and placed on a magnetic stirrer. A 40 mL volume of SL extract was added to the precursor’s solution with constant stirring. The ZnSe NPs formation was promoted by adding 1 M sodium hydroxide drop-wise in the reaction solution. After the appearance of color change, the solution was maintained at the same conditions with stirring status for 24 h. Resultant NPs were harvested by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 15 min. Finally, the precipitated ZnSe NPs were washed twice with ethanol and distilled water and then dried in an oven at 80°C23.

Characterization of ZnSe NPs

Biogenic ZnSe NPs were characterized with various high-technologic analytical techniques. UV–visible spectroscopy (Jenway, 6505 model, UK) was conducted to confirm NPs formation. FTIR spectroscopy (Bruker IFS 66/s, Optics, Billerica, MA) examined possible Interactive functional groups of metabolites involved in NPs coating and stabilization. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and SEM (TESCAN MIRA3) images of ZnSe NPs were performed to determine their sizes and morphologies. Along with SEM, energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) provided precise compositions of the ZnSe NPs as separate chemical elements. The X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku Ultima IV) profile was constructed to evaluate the crystallinity level and size of ZnSe NPs.

Antimicrobial assay of ZnSe NPs

The antimicrobial potential of SL-ZnSe NPs was monitored against three pathogens, including K. pneumoniae ESBL (ATCC700603) and S. aureus MRSA (ATCC 12600) and P. aeruginosa (HI). These experiments were performed using minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and standard well diffusion agar (WDA) method. Firstly, MIC values for SL-ZnSe NPs and SL-extract in the concentration range of 1000 –3.9 µg/mL against three pathogens by microdilution method in 96-well plates. After determining MIC values, well diffusion agar was conducted at a single dose of SL-ZnSe NPs (MIC dose), SL-Extract (MIC), oxacillin (Ox, 30 µg/mL), SL-ZnSe NPs + Ox (1/2MIC + 30 µg/mL) as a 40 µl of them for each well.

Analysis of related resistance gene

Following the identification of resistance in the pathogens, oxacillin-resistant genes were examined in three particular organisms. At first, K. pneumoniae ESBL were evaluated for the existence of the blaKPC gene, linked to resistance against beta-lactam antibiotics. To detect the blaKPC gene, PCR was performed with two targeted primers: Forward: 5′-ACGACGGCATAGTCATTTGC-3′ and Reverse: 5′-CATTCAAGGGCTTTCTTGCTGC-3′. This procedure enhanced a DNA segment consisting of 538 base pairs24. To detect the resistance gene in MRSA, a 533 bp fragment of mecA was selected for PCR amplification. Two mecA primers used in the study were included, F: 5′-AAAATCGATGGTAAAGGTTGG-C-3′ and R: 5′-AGTTCTGCAGTACCGGATTTG-C-3′25. An oxacillin-resistant metallo‑beta‑lactamase gene named NDM1 of P. aeruginosa was used for amplifying using two primers included F: 5′-CATTAGCCGCTGCATTGATG-3′ and R: 5′-GCGAAAGTCAGGCTGTGTTG-3′ for amplification of 445 base pairs fragment26. PCR amplification was designed based on a thermal cycling program as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 15 min, 35 cycles with denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 30 s and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. After PCR, electrophoresis was conducted on agarose gel, and the DNA bonds were visualized using ethidium bromide staining.

Antibiofilm activity assay

The antibiofilm activity of SL-ZnSe NPs was examined using the microdilution method on a 96-well plate as describe in the previous study27. This step added 150 µl of LB broth medium plus 1% glucose to each well. Inoculation was performed by 10 µl bacterial cells (0.5 McFarland cell densities). After treatment with 40 µl of SL-ZnSe NPs dilutions, the plate was incubated at 35 °C for 24 h. The medium was gently discarded to detect the adherent bacterial cells (biofilms), and the wells were washed with PBS to remove nonadherent cells and debris. After that, 200 µl of crystal violet (0.1%) was added to each well until biofilm stained. Finally, the excess stain was removed by washing, and the stained biofilm was destained by acetic acid solution (1%). The biofilm formation was determined indirectly by measuring the absorbance of destained crystal violet at wavelength 480 nm using UV-visible spectrophotometry.

To qualitatively investigate the antibiofilm activity of SL-ZnSe NPs, overnight bacterial culture was prepared in flasks containing LB broth medium plus 1% glucose. A sub-MIC dose of SL-ZnSe NPs was added to each bacterial cell flask, and sterile glass slides were immersed in the culture medium. After 48 h of incubation at 37 ◦C, the glass slides were removed and washed with PBS. Biofilm staining was carried out on the surface of the slides using crystal violet (1% w/v), as described in our previous study.

DPPH radical scavenging assay

Antioxidant activity of SL-ZnSe NPs and SL-Extract were estimated in terms of DPPH radical neutralization in an aqueous phase. A slightly modified method is described by Shakib et al. (2024)28. At first, a primary stock of DPPH reagent was prepared with 0.1 mmol in absolute methanol. The sample tests were diluted with two-fold serial dilutions with a 1 to 100 mg/mL concentration range. After that, 1mL of sample dilutions was mixed with 1mL of DPPH reagent in glass tubes and incubated in darkness for 30 min. The sample reactions were then subjected to measure their absorbance at 517 nm. Acid ascorbic was considered a positive control with 100% potency to DPPH inhibition for calculating the antioxidant capacity of the sample in terms of the following equation:

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic impacts of SL-ZnSe NPs and SL-Extract were assessed through the MTT-reducing assay on the human oral epithelial (KB) and HF normal fibroblast cell lines. To accomplish this, the cells were individually seeded at a density of 5 × 10³ cells/well in a 96-well plate and exposed to various concentrations (0–1000 µg/mL) of SL-ZnSe NPs or SL-Extract. The plate was kept at 35 °C with 95% humidity and 5% CO2 for 24 h. Subsequently, the cultured cells were taken out from the used medium, and 100 µl of new medium with 10 µg/mL MTT reagents was introduced to each well. Again, the cells were incubated for 4 h to allow reducing MTT by living cells. Subsequently, the formazan precipitate (reduced MTT) was mixed with 100 µL of DMSO to form a solubilized form. Finally, produced formazan was measured colorimetrically at 595 nm using a microplate reader (ELISAMAT2000, DRG Instruments, Marburg, Germany). The amounts of the formazan were introduced as percentages by following the formula:

Statistical analysis

To ensure dependable outcomes, every experimental method has been conducted three times. The collected data was presented as the average value and the standard deviation (mean ± SD). Statistical evaluation was performed using the one-way ANOVA test, applying a 95% confidence interval significance level and a p-value threshold of 0.05. The Tukey test was utilized to identify the most significant difference between these two groups. All analyses and corresponding graphs were constructed using GraphPad Prism statistical software version 9.

Results and discussion

Characterization of SL-ZnSe NPs

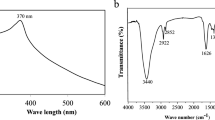

In forming ZnSe NPs, SL metabolites played a critical role in promoting nanoparticle growth after nucleation, which was caused by the reduction of zinc atoms29. Figure 1a and b illustrate the formation of ZnSe nanoparticles by SL metabolites, showcasing the color changes of the sample reaction before and after the process. The primary indication of the presence of ZnSe NPs was the change in color of the solution. Furthermore, the presence of some metabolites such as polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, proteins and polysaccharides can provide stabilization conditions during NPs growth and prevent the aggregation of NPs30,31. As shown in Fig. 1a, the formation of ZnSe NPs was confirmed visually by a color change from pale to yellowish-brown in the solution. As stated by Muntaz et al. (2018), the color change, linked to the quantum confinement effect, signifies the unique optical properties originating from the size and composition of NPs32.

Additionally, the UV-visible absorption spectra of SL-ZnSe NPs and SL-Extract were provided to determine the Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) of the NPs (Fig. 1c). In this study, SL-Extract exhibited a broad spectrum without clear absorbance peaks within the 250–700 nm scanning range. In contrast, SL-ZnSe NPs presented a distinct peak at 304 nm, attributed to the SPR of the synthesized nanoparticles. Chi et al. (2021) demonstrated that the absorption edge causes a sharp increase in absorption at wavelengths corresponding to the energy gap of ZnSe (approximately 300–400 nm in the UV region)33. Additionally, several studies have demonstrated that NPs generally display increased quantum yields compared to their corresponding bulk materials34,35.

Morphological and dimensional studies

SEM and TEM imaging were conducted to examine the size and morphology of the synthesized SL-ZnSe nanoparticles. As shown in Fig. 2a and d, SEM images of SL-ZnSe NPs were observed to be spherical with a size range of 20–30 nm. Accordingly, the TEM displayed coating agents within the nanoparticles as a less condensed structure embedded in the metal cores (Fig. 2b). The colloidal particles, such as SL metabolites, provide a support that coats nanoparticles during the synthesis process, preventing uncontrolled growth and aggregation30,36. As shown in Fig. 2c, the EDX pattern obtained from SL-ZnSe NPs not only confirmed the composition of the synthesized nanoparticles but also indicated that significant elemental ratios are associated with coating agents derived from SL extract, providing a high level of confidence in the accuracy of our findings.

The biological activity and behavior of ZnSe nanoparticles (NPs) are highly dependent on their size and shape. For instance, Chinnathambi et al. (2024) found that biogenic zinc-selenium nanoparticles, approximately 100 nm in size, were effective in antioxidant and anticancer activities. They also found DNA fragmentation and the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that led to apoptosis in cancer cells37. The shape and size (on the nanometer scale) observed by SEM suggest that the nanoparticles may have a sufficient surface area to interact within biological systems, and that their size might influence cellular uptake, distribution, and toxicity. Stepankova et al. (2023) have suggested that smaller nanoparticles tend to have an increased surface-area-to-volume ratio, which could improve reactivity and interactions with biomolecules, thereby enhancing biological efficacy in standard assays38.

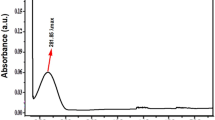

FTIR analysis

The chemical changes on the surface of the SL-ZnSe NPs were investigated using FTIR spectroscopy (Fig. 3). FTIR spectra elucidated active functional groups on the surface of NPs, as seen in Fig. 3, spectrum a (red color). Additionally, the black spectrum (b) revealed the presence of functional groups indicative of metabolites in the SL extract. A stretching peak in both the ZnSe NPs and plant extract at 3444 cm− 1 is associated with the involvement of hydroxyl groups from polyphenols in the stabilization or interaction of the Zn²⁺ ions during synthesis36. As seen in the spectra, shortening peak at 3444 cm−¹ in the ZnSe NPs can be related to the coordination of hydroxyl groups with Zn²⁺ and Se²⁻ during nanoparticle formation. The appearance of stretching peaks at 2925 cm− 1 corresponds to the C-H stretching of alkyl groups or long-chain carbonic compounds in the plant extract that actively interact with metal ions39. A stretching peak at 1636 cm− 1 that shifted to 1626 cm− 1 is attributed to carbonyl groups (C = O) in the ZnSe NPs spectrum. It can be concluded that flavonoids or polyphenols in the extract contribute to the formation of ZnSe NPs through reduction and potentially bind to the nanoparticle surface23. Two peaks at 1384 cm− 1 and 1396 cm− 1 in ZnSe NPs and SL-extract are predicted to be C-H bending or C-N stretching related to methyl or amine groups involved in ZnSe NPs formation40. A distinctive long peak differentially appeared in the plant spectrum at 1070 cm-1, shifting to 1084 cm− 1 in ZnSe NPs41. This coordination can potentially alter the electron density and vibration frequency of the bonds, which undergo a shortening or shift in the C-O stretching vibration42. Importantly, a peak at 748 cm− 1 is a clear indicator of ZnSe bond stretching, confirming the formation of ZnSe NPs. Moreover, the appearance of a distinct peak at 514 cm− 1 can be attributed to the lattice vibration of ZnSe NPs36.

XRD analysis

To examine the crystal structure of ZnSe NPs, XRD was employed as a standard technique, operating at a 2θ angle range of 10–70 degrees with 40 kV and 35 mA of Cu-Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å) radiation. Figure 4 presents the XRD pattern of SL-ZnSe NPs, with peaks emerging from Miller planes of (111), (220), (311), and (322) corresponding to 2θ angles of 27.2°, 45.2°, 53.45° and 66.35°. These peaks correspond well to the sphalerite-type cubic ZnSe structure and exhibit a significant resemblance to the standard data file No.37-1463, as deposited in JCPDS. Additionally, the broadness of the peaks indicates the nanostructured nature of the material. Additionally, the crystallite size for all peaks, as determined by the Scherrer equation, ranged from 10 to 20 nm, with the most prominent peak for the (111) orientation at 14.2 nm. As Verma et al. (2015) pointed out, ZnSe NPs with broader diffraction peaks at lower angles indicate a larger crystal size43. This understanding piques our curiosity about the role of XRD in uncovering the size and concentration of ZnSe NPs, which in turn influence their properties, as reflected in the XRD patterns44,45.

DPPH scavenging assay

The antioxidant activity of SL-ZnSe NPs was examined in comparison with S. lavandulifolia flower extract (SL-extract) as reducing or coating/stabilizing agents in NP synthesis. As shown in Fig. 5, the IC50 values for SL-ZnSe NPs, SL-extract, and ascorbic acid were 16.8, 35.7, and 11.6 mg/mL, respectively. Therefore, ZnSe NPs exhibit superior antioxidant activity compared to the SL extract, likely due to their increased surface area and reactivity46. The lower IC₅₀ value for ZnSe NPs indicates their higher efficiency in neutralizing DPPH radicals, which can be attributed to the unique properties of ZnSe NPs, such as electron transfer and surface reactivity47. The SL extract exhibits moderate antioxidant activity; however, the synergistic effect of the plant metabolites and ZnSe NPs may further enhance the overall antioxidant potential of the green-synthesized NPs. According to the literature, biogenic metal NPs can be explored for promising antioxidant-rich biomaterials to formulate in food, cosmetics and novel medicinal applications48.

Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of ZnSe NPs and SL extract was tested against three resistant pathogens. The MIC values for SL-ZnSe NPs against P. aeruginosa were 175 µg/mL, which is significantly lower than the MIC for the SL extract (100 mg/mL). These results indicate robust activity for SL-ZnSe NPs and moderate activity for SL-extract against P. aeruginosa. MIC of 350 µg/mL for S. aureus, MRSA, and K. pneumoniae, with blaKPC indicating that the ZnSe NPs are effective against these multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains. Still, the activity is weaker compared to that of the P. aeruginosa. SL-ZnSe NPs demonstrated the ability to interact with bacterial cells due to their large surface area, exerting increased bioactivity49. Furthermore, SL-ZnSe NPs may cross bacterial cell membranes more efficiently due to their small dimensions, resulting in the destruction and death of the bacteria. The SL extract acts as a capping agent in the biogenic process for ZnSe NP formation due to its bioactive compounds, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, and phenolic acids, thereby strengthening their antimicrobial effectiveness50. The pairing of zinc and selenium ions could also enhance the antibacterial characteristics, as zinc is recognized for its antimicrobial effects51. Additionally, antibacterial potentials of SL-ZnSe NPs, SL-extract and its combination with oxacillin were examined based on the well diffusion method (WDA) at a single dose (MIC) as seen in Fig. 6. According to the WDA assay, the antibacterial properties of ZnSe NPs demonstrated a synergistic effect when combined with oxacillin against multidrug-resistant pathogens, specifically K. pneumoniae, MDR. Therefore, employing metal NPs in combination with antibiotics can provide a synergistic mode against MDR pathogens52. Sometimes, it is observed that metal nanoparticles breach the resistance barrier due to the involvement of different modes of action and targets in antibiotic-resistant microorganisms53.

Biofilm inhibition assay

The antibiofilm activity of SL-ZnSe NPs was evaluated using a quantitative microdilution method to determine the minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) against the three aforementioned pathogens, making a significant contribution to the field. The findings revealed that SL-extract showed no antibiofilm at the treated concentration ranges applied for antimicrobial assay (0.97–1000 µg/mL). As shown in Table 1, the MBIC values for SL-ZnSe NPs against P. aeruginosa were 150 µg/mL, while this value against S. aureus MRSA and K. pneumonia MDR was found to be 200 µg/mL. The adhesion potential of biofilms of three pathogens was examined at exposure to a single dose of SL-ZnSe NPs (MBIC concentration) on the surface of glass slides. After 24 h of incubation, the biofilm formation was stained with crystal violet, and images were prepared in 2D and 3D, as shown in Fig. 7. The most pronounced biofilm inhibition was observed in P. aeruginosa, which is consistent with quantitative studies and the antibacterial potency of SL-ZnSe NPs. The analysis of the results suggests that the high surface area and reactivity of ZnSe NPs may interact with the biofilm matrix, preventing its formation or disrupting existing biofilms54. Bianchini Fulindi et al. (2023) demonstrated that ZnSe NPs could generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby inhibiting biofilm formation55. Studies by Mahamuni-Badiger et al. (2020) demonstrated that Zn-based nanoparticles disrupt the bacterial quorum sensing mechanism, a crucial signal for biofilm formation, thereby enhancing their effectiveness against various pathogens56. Accordingly, literature reported that zinc-based NPs have been found to weaken the structural integrity of biofilms by interacting with the extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that constitute the biofilm matrix57,58. Our findings are consistent with some studies, which demonstrate that metal NPs, such as ZnO, AgNPs, and ZnSe NPs, affect biofilm formation on various pathogens, including MRSA, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa30,59,60. These strategies include the direct alteration of biofilm structure, the induction of oxidative stress that leads to bacterial cell disruption, and the prevention of bacterial attachment to surfaces. These findings demonstrate the capability of metal nanoparticles, particularly ZnSe NPs, to serve as potent antibiofilm agents.

Molecular evaluation of resistant removal and plasmid curing

Molecular studies have been focused on the antimicrobial effects of ZnSe NPs in plasmid curing, targeting three resistant pathogens. After determining the MIC for each pathogen, the presence of plasmids containing resistance genes was examined under exposure to ZnSe NPs. Figure 8 illustrates the gel electrophoresis of pathogen samples treated with NPs. In Fig. 8A, bands of about 100 to 200 bp were visible in the gel electrophoresis of untreated samples, indicating the presence of plasmid DNA. In contrast, the samples treated with ZnSe NPs showed no plasmid bands. These plasmids in the bacteria carry resistance genes, such as blaKPC (for K. pneumoniae) and NDM1 (for P. aeruginosa), which are crucial for the development of their resistance61,62. S. aureus MRSA showed no bands on the gel, indicating the absence of plasmid DNA in both the control and nanoparticle-treated samples63. The effect of SL-ZnSe NPs on resistance genes in three pathogens was investigated using the PCR method, and the PCR product was run on 1.2% agarose gel (Fig. 8B). In this study, the presence of target genes was first confirmed in untreated or control samples. Thus, the genes of K. pneumoniae ESBL (blaKPC), P. aeruginosa (NDM-1) (NDM1) and S. aureus MRSA (mecA) were successfully amplified in the respective pathogens, indicating the presence of these key resistance genes. However, the genes of blaKPC (K. pneumoniae) and NDM1 (P. aeruginosa) showed inhibition in the presence of ZnSe NPs at MIC levels, indicating that these resistance mechanisms are sensitive to ZnSe NPs. In contrast, the mecA gene in MRSA showed the least inhibition, suggesting that MRSA may have a more potent resistance mechanism to ZnSe NPs or that the expression of the mecA gene is less affected. Several studies have highlighted the antimicrobial properties of metal NPs, like ZnSe NPs, against various pathogens. ZnSe NPs have been shown to exert antibacterial activity through multiple mechanisms49,64. As aforementioned, ZnSe nanoparticles can inhibit pathogens by producing reactive oxygen species (ROS), releasing metal ions and interacting with vital biomolecules, weakening bacterial defenses55,57,58. In the context of plasmid removal, ZnSe NPs can disrupt the stability of plasmids, thereby potentially reducing the expression of resistance genes65. Studies have shown that Zn-based nanoparticles can inhibit the expression of resistance genes, such as blaKPC and NDM1, associated with β-lactam and carbapenem resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Selim et al. (2024) showed that biogenic ZnO NPs could inhibit the growth and infection of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii strains isolated from burn wound patients. They also detected the blaKPC gene associated with carbapenem resistance in 85% of the isolated pathogens66. In another study, Masoumi et al. (2018) examined the effects of TiO2 and ZnO NPs against drug-resistant strains of P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and A. baumannii. Their results confirmed that the potential of the tested nanoparticles on the growth of pathogens was more potent when combined with two antimicrobial peptides, mastoparan-B and indolicidin67. In this regard, our findings indicated that these genes are inhibited by ZnSe NPs, except for S. aureus MRSA, which presents a more complicated case due to the chromosomal nature of the mecA gene and its distinct resistance mechanism25. However, mecA may be less affected by specific nanoparticles due to the multifunctional activity of nanoparticles against pathogens, which can impact other routes, such as ROS generation, ionic perturbation, cell wall disruption, enzyme inhibition, or combinations of these mechanisms.

PCR products of resistant genes for and untreated (control, C) and treated (T) groups with ZnSe NPs (at MIC values) against K. pneumonia (blakpc gene), P. aeruginosa (NDM-1 gene) and S. aureus (mecA gene). (a) The formation of DNA bands indicates the presence of gene in related pathogens. (b) Confirmation of the presence of plasmid in the bacterial cells.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity tests based on the MTT assay were calculated using GraphPad Prism software version 9 with a nonlinear regression method. Cytotoxicity of SL-ZnSe NPs and SL-Extract was examined on the KB cell line in comparison with HF normal fibroblast cells. Figure 9 represents the cell viability at various SL-ZnSe NPs concentrations (0–5000 µg/mL) for tumor and normal cell lines. The cytotoxicity effects of SL-ZnSe NPs and SL-extract exhibited a dose-dependent model for both cell lines. However, the IC50 values of SL-ZnSe NPs for KB and HF cell lines were determined to be 23.43 and, 30.15 µg/mL, respectively. The results demonstrated that SL-ZnSe NPs exhibited a selective mode of action for cancer and normal cells, allowing for a clear distinction between these cell types. In this regard, the cytotoxicity of the SL extract showed no differences between the two cell lines. Additionally, the positive control showed more cytotoxicity against normal cells compared to the cancer cell line. Studies have shown that the cytotoxic effects of ZnSe NPs are due to different mechanisms. ZnSe NPs can induce oxidative stress, leading to cell damage and apoptosis. ROS production is often size-dependent, and smaller nanoparticles induce more oxidative stress23.

Furthermore, the released zinc and selenium ions may further interact with cellular biomolecules, disrupting their normal metabolism. Studies have reported the cytotoxicity of ZnSe NPs against several cancer cell lines, with IC50 values commonly ranging between 10 µg/mL and 50 µg/mL. Such toxicity was assigned to particle size, surface charge, and biological or chemical modifications. In this regard, the literature approximated the toxicity level of ZnSe NPs with an IC50 range of 20–30 µg/mL against various cancer cell lines, aligning with our observations. They reasoned that these differences in toxicity might arise from variations in fabrication techniques and the types of coating and stabilizing agents utilized for the nanoparticles49,64,68. In a study by El-Zayat et al. (2021), biogenic ZnSe NPs were produced using Ephedra aphylla extract, which showed IC50 values of 23.92 µg/mL against HeLa cell lines, consistent with our observed IC50 for ZnSe NPs (23.01 µg/mL)69. This suggests that the green synthesis method for nanoparticles can significantly impact the basic cytotoxic profile of ZnSe NPs. Therefore, plant extract-mediated functionalization may modulate the efficacy and enhance the biocompatibility of nanoparticles68. This study confirmed the potential of ZnSe NPs and plant extracts to inhibit cancer cell growth. However, further optimization and formulation are needed to enhance the properties and targeted effects on cancer cells, thereby improving cytotoxicity and targeting efficiency for therapeutic use.

Conclusion

In this research, ZnSe NPs were effectively produced via a biogenic technique utilizing an aqueous extract from S. lavandulifolia. Significant biological activity was observed for ZnSe NPs, highlighting their promising potential in therapeutic and medical applications. Although ZnSe NPs have been suggested for multiple uses primarily due to their optical and semiconducting properties, this study aimed to explore them from a biomedical perspective in every aspect thoroughly. The potential of ZnSe NPs in various biological applications, such as antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anticancer purposes, is a reason for optimism in the field. Accordingly, outcomes demonstrated that ZnSe NPs made with S. lavandulifolia extract may be utilized in the future for these promising applications.

Data availability

The datasets obtained by experimentation in this study can be available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

References

Kirubakaran, D. et al. Eco-friendly synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles by clerodendrum heterophyllum leaf extract and their biological applications. BioNanoScience 13, 2252–2264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-023-01222-x (2023).

Abbigeri, M. B. et al. Potential in vitro antibacterial and anticancer properties of biosynthesized multifunctional silver nanoparticles using Martynia annua L. leaf extract. Nano-Structures Nano-Objects. 39, 101320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoso.2024.101320 (2024).

Abbigeri, M. B. et al. Antioxidant and anti-diabetic potential of the green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Martynia annua L. root extract. Nano TransMed. 4, 100070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ntm.2025.100070 (2025).

Bhavi, S. et al. Potential antidiabetic properties of Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels leaf extract-mediated silver nanoparticles. Austin J. Anal. Pharm. Chem. 11, 1168 (2024).

Kirubakaran, D., Selvam, K., Prakash, P., Shivakumar, M. S. & Rajkumar, M. In-vitro antioxidant, antidiabetic, anticholinergic activity of iron/copper nanoparticles synthesized using Strobilanthes cordifolia leaf extract. OpenNano 14, 100188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onano.2023.100188 (2023).

Lashgarian, H. E., Karkhane, M., Kamil Alhameedawi, A. & Marzban, A. Phyco-mediated synthesis of ag/agcl nanoparticles using ethanol extract of a marine green algae, Ulva fasciata delile with biological activity. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 11, 14545–14554. https://doi.org/10.33263/BRIAC116.1454514554 (2021).

Kirubakaran, D. et al. Bio-fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Strobilanthes cordifolia: characterization and evaluation of antioxidant, anti‐cholinergic, anti‐inflammatory and wound healing activities. ChemistrySelect 9, e202302792 (2024).

Nayak, R., Gupta, T. & Chauhan, R. P. Plant metabolites assisted green synthesis of znse: structural, optical and transport properties. Chem. Pap. 76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11696-022-02350-6 (2022).

Thokchom, B., Bhavi, S. M., Abbigeri, M. B., Shettar, A. K. & Yarajarla, R. B. Green synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications of Centella asiatica-derived carbon Dots. Carbon Lett. 33, 1057–1071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42823-023-00505-3 (2023).

Yalshetti, S. et al. Microwave-assisted synthesis, characterization and in vitro biomedical applications of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis Linn.-mediated carbon quantum Dots. Sci. Rep. 14, 9915. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60726-y (2024).

Church, N. A. & McKillip, J. L. Antibiotic resistance crisis: challenges and imperatives. Biologia 76, 1535–1550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11756-021-00697-x (2021).

Akram, F., Imtiaz, M. & Haq, I. u. Emergent crisis of antibiotic resistance: A silent pandemic threat to 21st century. Microbial Pathogenesis 174, 105923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105923 (2023).

Singh, A. et al. Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles as effective alternatives to treat antibiotics resistant bacterial infections: A review. Biotechnol. Rep. 25, e00427 (2020).

Mishra, A. et al. Metal nanoparticles against multi-drug-resistance bacteria. J. Inorg. Biochem. 237, 111938 (2022).

Himanshu et al. Nanobiotics and the one health approach: boosting the fight against antimicrobial resistance at the nanoscale. Biomolecules 13, 1182 (2023).

Alanazi, A. D., Majeed, Q. A., Alnomasy, S. F. & Almohammed, H. I. Potent in vitro and in vivo effects of Stachys Lavandulifolia methanolic extract against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Trop. Med. Infect. Disease. 8, 355 (2023).

Bingol, M. N. & Bursal, E. LC-MS/MS analysis of phenolic compounds and in vitro antioxidant potential of stachys Lavandulifolia vahl. Var. Brachydon Boiss. Int. Lett. Nat. Sci. 72 (2018).

Veisi, H. et al. Biosynthesis of CuO nanoparticles using aqueous extract of herbal tea (Stachys Lavandulifolia) flowers and evaluation of its catalytic activity. Sci. Rep. 11, 1983. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81320-6 (2021).

Zangeneh, M. M., Joshani, Z., Zangeneh, A. & Miri, E. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Stachys Lavandulifolia flower, and their cytotoxicity, antioxidant, antibacterial and cutaneous wound-healing properties. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 33, e5016 (2019).

Moghaddam, M. R. J., Tehranipour, M. & Molavi, F. Antitumor Activity of Biogenic Synthetized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Mediated Stachys Lavandulifolia: In-Vivo Study Model 1–9 (BioNanoScience, 2024).

Veisi, H., Farokhi, M., Hamelian, M. & Hemmati, S. Green synthesis of Au nanoparticles using an aqueous extract of Stachys Lavandulifolia and their catalytic performance for alkyne/aldehyde/amine A 3 coupling reactions. RSC Adv. 8, 38186–38195 (2018).

Singh, S. R. et al. The effect of clitoria Ternatea L. flowers-derived silver nanoparticles on A549 and L-132 human cell lines and their antibacterial efficacy in Caenorhabditis elegans in vivo. Hybrid. Adv. 8, 100359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hybadv.2024.100359 (2025).

Mirzaei, S. Z. et al. Phyco-fabrication of bimetallic nanoparticles (zinc–selenium) using aqueous extract of Gracilaria corticata and its biological activity potentials. Ceram. Int. 47, 5580–5586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.10.142 (2021).

Al-Agamy, M. H., Aljallal, A., Radwan, H. H. & Shibl, A. M. Characterization of carbapenemases, esbls, and plasmid-mediated quinolone determinants in carbapenem-insensitive Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Riyadh hospitals. J. Infect. Public Health. 11, 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2017.03.010 (2018).

Akter, S. et al. Detection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and their resistance genes from houseflies. Veterinary World. 13, 266–274. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2020.266-274 (2020).

Joji, R. M., Al-Rashed, N., Saeed, N. K. & Bindayna, K. M. Detection of VIM and NDM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase genes in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains in Bahrain. J. Lab. Physicians. 11, 138–143. https://doi.org/10.4103/jlp.Jlp_118_18 (2019).

Mirzaei, S. Z. et al. Bio-inspired silver Selenide nano-chalcogens using aqueous extract of Melilotus officinalis with biological activities. Bioresources Bioprocess. 8, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-021-00412-3 (2021).

Shakib, P. et al. Biofabrication of copper oxide nanoparticles mediated with Echium amoenum petal extract for evaluation of biological functions. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 14, 25651–25661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04796-4 (2024).

González-Panzo, I. J. et al. ZnSe nanoparticles growth by aqueous colloidal solution at room temperature. J. Cryst. Growth. 577, 126407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2021.126407 (2022).

Dehghani, S., Khandan Nasab, N. & Darroudi, M. Zinc Selenide nanoparticles: green synthesis and biomedical applications. Nanomed. J. 9, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.22038/nmj.2022.61875.1638 (2022).

Kim, O. et al. Effect of PVP-Capped ZnO nanoparticles with enhanced charge transport on the performance of P3HT/PCBM polymer solar cells. Polymers 11, 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11111818 (2019).

Muntaz Begum, S., Ravindranadh, K., Ravikumar, R. & Rao, M. Structural and luminescent properties of PVA capped ZnSe nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Innovations. 22, 37–42 (2018).

Chi, T. T. K., Hien, B. T. T., Nam, M. H. & Hai, P. N. Structural and optical properties of ZnSe nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 21, 2582–2587. https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2021.19114 (2021).

Gao, W. et al. Size-dependent anti-inflammatory activity of a peptide-gold nanoparticle hybrid in vitro and in a mouse model of acute lung injury. Acta Biomater. 85, 203–217 (2019).

Kim, B. J. et al. Unlocking invisible defects of ZnSe alloy shells in giant quantum Dots with near unity quantum yield. Adv. Energy Mater. 2400148. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202400148 (2024).

Kumar, R. et al. ZnSe nanoparticles reinforced biopolymeric soy protein isolate film. J. Renew. Mater. 7, 749–761 (2019).

Chinnathambi, A. et al. Biofabrication of bimetallic selenium@zinc nanoparticles using Champia parvula aqueous extract: investigation of anticancer activity and its apoptosis induction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 733, 150417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.150417 (2024).

Stepankova, H. et al. Unveiling the nanotoxicological aspects of se nanomaterials differing in size and morphology. Bioactive Mater. 20, 489–500 (2023).

Farooqi, M. A. et al. Eco-friendly synthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles from black roasted gram (Cicer arietinum) for biomedical applications. Sci. Rep. 14, 22922. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72356-5 (2024).

Çakıcı, T., Özdal, M., Kundakcı, M., Kayalı, R. & ZnSe and CuSe NP’s by microbial green synthesis method and comparison of I-V characteristics of Au/ZnSe/p-Si/Al and Au/CuSe/p-Si/Al structures. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 103, 104610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2019.104610 (2019).

Divyasree, M. et al. ZnSe/PVP nanocomposites: synthesis, structural and nonlinear optical analysis. Mater. Chem. Phys. 197, 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.04.069 (2017).

Gupta, P., Patel, P., Sujata, K. M., Litoriya, P. K. & Solanki, R. G. Facile synthesis and characterization of ZnSe nanoparticles. Mater. Today Proc. 80, 1556–1561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.01.389 (2023).

Verma, M., Patidar, D., Sharma, K. & Saxena, N. J. J. O. N. & optoelectronics. Synthesis, characterization and O.tical properties O. CdSe and ZnSe quantum Dots. J. Nanoelectronics Optoelectron. 10, 320–326 (2015).

Toufanian, R., Zhong, X., Kays, J., Saeboe, A. & Dennis, A. Correlating ZnSe quantum Dot absorption with particle size and concentration. Chem. Mater. 33, 7527–7536. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.1c02501 (2021).

Zaman, M. B. et al. Growth and properties of hydrothermally derived crystalline ZnSe quantum Dots. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 3953–3959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11026-1 (2021).

Somaghian, S. A. et al. Biogenic zinc Selenide nanoparticles fabricated using Rosmarinus officinalis leaf extract with potential biological activity. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-023-04329-6 (2024).

Razzaq, H. et al. Interaction of gold nanoparticles with free radicals and their role in enhancing the scavenging activity of ascorbic acid. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 161, 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.04.003 (2016).

Ge, X., Cao, Z. & Chu, L. The antioxidant effect of the metal and metal-oxide nanoparticles. Antioxidants 11, 791 (2022).

Anastasescu, C. et al. Antibacterial activity of znse, ZnSe-TiO2 and TiO2 particles tailored by lysozyme loading and visible light irradiation. Antioxidants 12, 691 (2023).

Deepika, D., Rakesh, Singh, S. & Kumar, A. Effect of capping agents on optical and antibacterial properties of cadmium Selenide quantum Dots. Bull. Mater. Sci. 38, 1247–1252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12034-015-1006-9 (2015).

Ahmad, A. et al. Zinc oxide–selenium heterojunction composite: synthesis, characterization and photo-induced antibacterial activity under visible light irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 203, 111743 (2020).

Bankier, C. et al. Synergistic antibacterial effects of metallic nanoparticle combinations. Sci. Rep. 9, 16074 (2019).

Agreles, M. A. A., Cavalcanti, I. D. L. & Cavalcanti, I. M. F. Synergism between metallic nanoparticles and antibiotics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 106, 3973–3984 (2022).

Tripathi, N. & Goshisht, M. K. Recent advances and mechanistic insights into antibacterial activity, antibiofilm activity, and cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 5, 1391–1463 (2022).

Bianchini Fulindi, R. et al. Zinc-based nanoparticles reduce bacterial biofilm formation. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e04831–e04822 (2023).

Mahamuni-Badiger, P. P. et al. Biofilm formation to inhibition: role of zinc oxide-based nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Engineering: C. 108, 110319 (2020).

Omran, B. A., Tseng, B. S. & Baek, K. H. Nanocomposites against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: recent advances, challenges, and future prospects. Microbiol. Res. 282, 127656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2024.127656 (2024).

Bouasla, N. et al. Antimicrobial activity of ZnS and ZnO-TOP nanoparticles Againts pathogenic bacteria. Chem. Biodivers. e202400724. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.202400724 (2024).

Ilahi, N. et al. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using endophytic fusarium oxysporum strain NFW16 and their in vitro antibacterial potential. Microscopy Res. 85, 1568–1579 (2022).

Gupta, P. et al. Enhanced antibacterial and photoluminescence activities of ZnSe nanostructures. ACS Omega. 8, 13670–13679. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c07654 (2023).

Shields, R. K. et al. Emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance due to plasmid-borne bla KPC-3 mutations during treatment of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 61 (2017).

Chen, H. et al. Novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains co-harbouring Bla NDM-1 Metallo β-lactamase and mcr-1 isolated from immunocompromised paediatric patients. Infect. Drug Resist. 2929–2936 (2022).

Jiang, J. H., Cameron, D. R., Nethercott, C., Aires-de-Sousa, M. & Peleg, A. Virulence attributes of successful methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 36, e00148–e00122 (2023).

Baruah, J., Narayan, J., Kalita, S. & Kandimalla, R. Green chemistry mediated facile synthesis of surface passivated ZnSe QDs and their cytotoxicity evaluation. Mater. Today Proc. 51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.11.587 (2021).

Ibraheem, M. R. & Al-Ugaili, D. N. Nanoparticle-Mediated plasmid curing in combating antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria. J. Angiotherapy. 8, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.25163/angiotherapy.839495 (2024).

Selim, M. I., Sonbol, F. I., El–Banna, T. E., Negm, W. A. & Elekhnawy, E. Antibacterial and wound healing potential of biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles against carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii: an in vitro and in vivo study. Microb. Cell. Fact. 23, 281. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-024-02538-3 (2024).

Masoumi, S., Shakibaie, M. R., Gholamrezazadeh, M. & Monirzadeh, F. Evaluation synergistic effect of TiO2, ZnO nanoparticles and amphiphilic peptides (Mastoparan-B, Indolicidin) against Drug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae and acinetobacter baumannii. Archives Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 6, e57920. https://doi.org/10.5812/pedinfect.57920 (2018).

Mir, D. et al. Antimicrobial and biocompatibility of highly fluorescent ZnSe core and znse@zns core-shell quantum dots. J. Nanopart. Res. 20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-018-4281-8 (2018).

El-Zayat, M. M. et al. The antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activity of Greenly synthesized selenium and zinc composite nanoparticles using ephedra aphylla extract. Biomolecules 11, 470 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The study received financial support from Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences with grant number: 3011565 and ethical approval code: IR.KUMS.REC.1400.418. Most experiments were conducted at Razi Herbal Medicines Research Center, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Investigation: R.S, R.A, Formal analysis: A.M Methodology: M.K, P.S, Project administration: A.M, B.N, Software: M.K, S.G, Writing–original draft: R.S, Methodology: S.Z.M, Writing– review & editing: A.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saki, R., Shakib, P., Nomanpour, B. et al. Bio-assessments of the antibiofilm, antioxidant, and plasmid inhibitory effects of zinc selenide nanoparticles synthesized using Stachys lavandulifolia extract. Sci Rep 15, 35633 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19525-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19525-2