Abstract

Reconstructing hidden thermal and flow structures from limited observations is a fundamental challenge in many scientific disciplines. Particles passively advected by the surrounding fluid often encode valuable information along their trajectories, but such data are typically sparse and noisy. To infer the comprehensive dynamics of thermally driven flows from such limited information, we develop a four-dimensional variational (4DVar) Marker-in-Cell method. Its application to laboratory data demonstrates successful reconstruction of the time-dependent temperature field and the Rayleigh number—unobservable yet essential for understanding thermal forcing and heat transport—by assimilating particle trajectories with the governing equations. Furthermore, our method enables prediction of future evolution beyond the assimilation window, yielding results that are consistent with actual observations. We critically assess the method’s performance in light of convective dynamics, identifying the conditions under which it is effective and outlining directions for future refinement. These findings highlight the utility of 4DVar not only for retrospective reconstruction but also for forward prediction of convective behavior, offering a robust framework for analyzing thermally or compositionally driven flows in geophysical and engineering systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is a common challenge across various research fields to estimate the dynamics of fluids, including their flow patterns, thermal and chemical structures, and time evolution. In many geoscientific settings, fluids contain passive particles that carry information about their surrounding environment. For example, floating pumice originating from submarine volcanoes is attached with organisms such as barnacles, and therefore it can provide insights into its source and the oceanic flow process1. The distribution and mineral composition of volcanic ash can indicate eruption mass rates, cooling processes, and wind speed and direction2,3,4. Similarly, metamorphic rocks derived from the deep Earth may record pressure, temperature, and strain, thereby revealing the convective processes of the surrounding mantle5,6,7,8,9. These particles not only offer spatial information, but also preserve the chemical and thermal evolution of the surrounding fluid over time. In this context, physical quantities in fluid systems—such as temperature, flow velocity, or pressure—can be described from two complementary perspectives: the Eulerian perspective, which observes how these values change at fixed points in space, and the Lagrangian perspective, which follows how individual passive particles experience these values along their trajectories.

In natural systems, the motion of Lagrangian tracers such as mantle rocks and volcanic ejecta can often be observed only incompletely or indirectly. For instance, the trajectories of deep Earth materials may be inferred from metamorphic pressure-temperature histories, and plate motions can be estimated from seafloor magnetic anomalies6,7,10. Similarly, the dispersal of volcanic materials can be observed using meteorological satellites or in situ field surveys3,11. Such observations typically provide only partial and sparse trajectories relative to the full complexity of the underlying flow. Moreover, in situ measurements of the surrounding fluid’s thermal or compositional state are often unfeasible due to the large spatial scales or technical limitations. This lack of direct measurements introduces uncertainty in key fluid properties such as density and viscosity, which fundamentally govern convective behavior. Consequently, these uncertainties propagate into model predictions, making it inherently difficult to reconstruct or forecast the spatio-temporal evolution of convective systems.

To estimate key unknown variables from limited data, data assimilation (DA)—which integrates observational data with governing physical models—provides a powerful approach. However, examples of DA that incorporate individual Lagrangian particles remain limited12,13,14, and thus establishing such a framework holds substantial value. To validate its effectiveness, it is appropriate to first apply DA to laboratory experiments, where key variables are at least partially observable, before extending it to natural systems in which those quantities are difficult or impossible to measure directly. Most existing approaches estimate unknown parameters such as temperature from fully known Eulerian velocity fields, whether in forward simulations or inverse modeling15,16,17,18. In contrast, we focus on particle tracking velocimetry (PTV), which provides Lagrangian particle trajectories that are irregularly sampled in both space and time—closely mimicking realistic environmental conditions. This makes PTV a promising observational basis for Lagrangian DA in geophysical applications. To make use of such data, we have developed a four-dimensional variational Marker-in-Cell method (4DVarMiC). This framework enables the quantitative estimation of thermal and flow structures, along with their temporal evolution, based on information encoded in passively advected tracer particles.

While 4DVarMiC has been successfully applied to synthetic datasets19, its use for experimental or field-based particle tracking data—where noise and irregular sampling are inevitable—has not yet been demonstrated. The method is expected to yield solutions closer to the true state than raw observations by strictly satisfying the governing equations of fluid dynamics. This makes 4DVarMiC well suited for assimilating noisy experimental data. Compared to physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), which incorporate physical constraints as soft penalties in their loss functions20,21,22, 4DVarMiC enforces these constraints exactly. As a result, PINNs may overfit noisy data and generate solutions that violate conservation laws, whereas our variational approach offers greater robustness and physical consistency.

To demonstrate the applicability of DA, we apply our method to particle tracking data from Rayleigh–Bénard convection (RBC) experiment—a canonical system where a fluid layer heated from below and cooled from above develops buoyancy-driven flow. Despite its simplicity, RBC serves as a fundamental model for a variety of natural and geophysical phenomena, including mantle convection23,24, magma migration along dykes25, and hydrothermal circulation26. In general, the dynamics of RBC are governed by the Rayleigh number (Ra), the Prandtl number (Pr), and the system geometry. Ra represents the ratio of thermal buoyancy to viscous and thermal dissipation, while Pr characterizes the ratio of viscous to thermal diffusivity:

where \(\rho _0\) is the reference density, g is the gravitational acceleration, \(\alpha _T\) is the thermal expansivity, \(\Delta T\) is the temperature difference between the upper and lower boundaries of the fluid layer, h is the height of the fluid layer, \(\eta\) is the dynamic viscosity, and \(\kappa\) is the thermal diffusivity. Key flow characteristics such as velocity magnitude, convection roll size, boundary layer thickness, and heat transfer efficiency can be captured by these nondimensional parameters23,27,28. In this study, Ra is treated as a target parameter that is inferred in addition to the thermal and flow fields through DA.

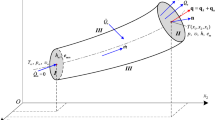

Schematic illustration of this study. The upper panel shows data obtained from a laboratory experiment. A narrow rectangular tank filled with a thermally convecting, highly viscous fluid is illuminated by light, allowing tracer particles to be visualized and tracked over time. Their trajectories are recorded as video and used to extract the time series of particle positions. The lower panel shows the estimated variables obtained through data assimilation. Observed particle tracks are assimilated into the conservation laws of fluid dynamics. \(\varvec{x}^\textrm{obs}_i\): observed positions of particle i; T: temperature; \(\varvec{u}\): velocity; \(\varvec{x}_i\): particle position; Ra: Rayleigh number. All variables, except Ra, are functions of time t.

More specifically, Fig. 1 illustrates the overall scheme of this study. Under the constraints of the conservation laws of fluid dynamics—namely, the equations of motion and heat transfer (Eqs. 3 and 4)—the time series of temperature, velocity, and particle positions are estimated using 4DVarMiC, so as to reproduce the particle trajectories observed in the experiment. These quantities are optimized simultaneously to minimize the cost function J, which quantifies the discrepancies in position and velocity between observed and modeled particles (Eq. 7). In addition to reconstructing the thermal and flow fields, we aim to estimate Ra, a key control parameter in thermal convection. Although Ra is typically treated as a known or given input in theoretical and experimental studies, it is, in practice, not directly observable and must be inferred from indirect measurements. Unlike conventional forward simulations, DA enables the objective estimation and validation of model parameters by integrating data and physics. In particular, we demonstrate that time-resolved comparisons with validation data allow us to quantitatively evaluate the fidelity of the reconstructed solution. This approach establishes a robust and objective framework for inferring thermofluid dynamics from sparse and noisy Lagrangian observations.

Results

Thermal convection experiment

In the laboratory experiment, a viscous aqueous xanthan gum solution containing tiny passive tracer particles undergoes thermal convection within a narrow rectangular vessel (\(h=\) 50 mm in height \(\times\) 200 mm in width \(\times\) 6 mm in thickness; Fig. 1). That is, the ratios of the horizontal length to the height are 4 for the wider direction and 0.12 for the narrower direction (\(\Gamma _x = 4.0\) and \(\Gamma _y = 0.12\)). Inertial effects can be negligible in this setting because of a high Pr (= 70) and strong geometric confinement imposed by the experimental vessel29,30. The vessel is heated at the bottom plate and cooled at the top plate, both maintained at constant temperatures, giving rise to RBC. The fluid motion is visualized as the movement of particles at the central vertical cross-section of the vessel illuminated by a laser sheet whose thickness is approximately 1 mm. Here, we intentionally employ the Hele-Shaw geometry, a narrow vessel that constrains the particle motions quasi-two-dimensional (quasi-2D)30,31. This configuration allows us to simplify the governing equations for DA and reduce its computational cost, while maintaining the convective dynamics to be time-dependent32.

Figure 2a shows a portion of the detected particle tracks, with a spatial resolution of 0.11 mm and a temporal resolution of 0.2 s (see Methods for particle detection method). Due to thermal buoyancy, five large convection rolls (\(\sim\)40 mm in width and \(\sim\)50 mm in height) form, accompanied by two smaller convection rolls (\(\sim\)20 mm in width and \(\sim\)25 mm in height) in the top-left and bottom-right corners. Near the four boundaries, slower particle velocities are observed, suggesting that the boundaries impose a no-slip condition. Additionally, as some particle tracks intersect around these corner rolls, weak periodic flow occurs near the side boundaries, indicating that the convection mode can be classified as a quasi-steady Hele-Shaw regime30,31,32.

Ra in 2D and 3D domains

As mentioned above, the consequential convective dynamics is quasi-2D due to the lateral confinement. It is necessary to carefully compare Ra in the 3D laboratory experiments and that in the 2D numerical models because the meaning of the value of Ra depends on the geometry. Theoretically derived critical value for the onset of convection for an infinitely extended plane layer is 1708, when the top and bottom are no-slip boundaries33. When there exist sidewalls as in actual settings, the critical value of Ra for the onset increases more or less due to the no-slip velocity boundaries at the sidewalls. If the horizontal confinement is not so strict, that is, the shorter horizontal length is larger or comparable to the layer height, the increase of this value is very small. If it is shorter than unity, the effect of no-slip side walls becomes dominant and the value increases with the narrowness of the space. In case of the geometry of the present setting (\(\Gamma _x = 4.0\) and \(\Gamma _y = 0.12\)), the critical value for the onset of convection is Ra = \(3.0 \times 10^4\)32,34.

Hereafter, we distinguish two Rayleigh numbers; one is \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}}\) that is the value to express the actual setting of the experiment, and the other is \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) that we use for 2D simulations. The 2D condition means that any variable does not depend on y and that the flow velocity does not have y-component. Then the values for the onset of convection are \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}} = 3.0 \times 10^4\) and \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 1.7 \times 10^3\), respectively.

Convective motions in such a narrow geometry were studied systematically in Yanagisawa et al.32 and confirmed to be quasi-2D below a certain \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}}\) (\(\sim 3 \times 10^6\) in the present setting), i.e., gap-wise velocity component is negligibly small and Poiseuille-like parabolic velocity profiles are achieved30. The particles hardly deviate from the observing plane, however, the trajectories inherently contain interruptions because of experimental noise (see Methods). We therefore simplified the governing equation for 4DVarMiC to be 2D, although it is conceptually applicable to 3D flows. Note that the consequential quasi-2D convective flows in such a narrow geometry are developed via 3D process and therefore cannot be reproduced in a 2D domain. When we start 2D simulation from random or any given wavenumber of initial perturbation, the pattern evolves into horizontally elongated one with two or three rolls and time dependency is observed everywhere (Fig. S13). We selected a case with \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}} \sim 1.6 \times 10^6\) and \(\Delta T =\) 9.0 K for the experimental condition, leading to quasi-2D and unsteady (oscillatory) fluid motions. In this case, the period of oscillation is approximately 1.5 min, and the circulation time for a convection roll is comparable to this.

Observed particle trajectories and data assimilation results. (a) Detected particle tracks from t = 0 to 1 min. One out of every ten trajectories was randomly selected from 7890 particles for visibility. Brighter colors indicate later stages. The movie of the particle track data can be available from Supplementary Information (Movie S1). (b) Same as (a), but simulated using 4DVarMiC with \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\) after 2000 iterations. The particles corresponding to those in (a) are shown in the same colors. Portions of the particle tracks where data is missing have been omitted. (c) Estimated thermal structure and flow velocity at \(t = 1\) min in the 4DVarMiC simulation with \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\) after 2000 iterations. The estimated thermal structure, shown as a colored contour, is scaled so that the upper boundary is 0 and the lower boundary is 1. The flow velocity is represented by arrows. The snapshots and movie of this 4DVarMiC run can be available in Supplementary Information (Fig. S5 and Movie S3).

4DVarMiC solutions

By assimilating two minutes of the particle track data, which is almost one cycle of the oscillation observed in the particle track data, 4DVarMiC successfully reconstructs the thermal and flow structures (Fig. 2b, c). The estimated temperature field (Fig. 2c) drives the modeled flow such that thermal buoyancy governs the motion of all particles (Fig. 2b). For instance, four downwelling flows align with cold anomalies, while four upwelling flows correspond to hot anomalies.

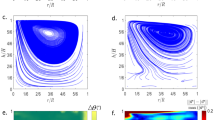

The inferred thermal structure is notably sensitive to the a priori value of \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\), whereas the flow patterns and velocities remain similar across simulations (Fig. 3). In the three cases shown in Fig. 3, each with different \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) values, the thermal anomalies produce vertical particle motions consistent with observations. At \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^4\) (Fig. 3a), the cold and hot regions exhibit temperatures beyond those at the cooled top and heated bottom boundaries, respectively. These unrealistic values, arising despite the absence of internal heat sources or sinks, compensate for weak thermal forcing at low \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) via large horizontal gradients \(\partial T/\partial x\) (Eq. 3). A similar behavior was reported in an earlier study using synthetic data35, suggesting that the true \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) exceeds \(3 \times 10^4\). At \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\) (Fig. 3b), the temperature anomalies are more moderate, and the estimated temperatures remain bounded by the top and bottom boundary values. The flow structure remains consistent across cases. The cost function reaches a minimum near \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\) (Fig. 3d), and we adopt this value for further analysis. At \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^6\) (Fig. 3c), the thermal anomalies nearly vanish while the velocity field remains. However, the cost function increases due to excessive flow velocities associated with high \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) (Fig. 3d).

A plausible value of \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\) is supported by the following: (1) the reconstructed temperature remains within physical bounds (\(0 \le T \le 1\) in the non-dimensional form); (2) the cost function J reaches a minimum at this value, while the flow features remain robust throughout the assimilation time window (ATW; Fig. 3d); and (3) the recovered solution captures quasi-steady corner-roll oscillations, a behavior restricted to a narrow range of \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}}\)30, not observed in standard forward 2D simulations with random thermal perturbations (Fig. S13). This suggests that physically plausible assimilation is achieved. Altogether, we find that \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}} = 1.6 \times 10^6\) corresponds well to \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\). As will be discussed later, additional forward simulations have independently confirmed that \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}} = 1.6 \times 10^6\) yields the same level of flow velocity and surface Nusselt number as \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\) (see Fig. S14).

While the main results use the full available particle dataset, we also evaluated 4DVarMiC performance with fewer particles and lower temporal resolution (Figs. S8 and S9). These tests confirm that the current data resolution is sufficient for the analysis. However, uniformity in the spatial and temporal distribution of particles remains a key factor influencing assimilation performance, meriting further study, especially in more complex or turbulent regimes.

Results of the 4DVarMiC simulations for different \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) values. (a) 4DVarMiC with \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^4\) at \(t = 2\) min after 2000 iterations. The colored contours represent the estimated non-dimensional temperature, and the arrows indicate the flow velocity. The white lines indicate isotherms at temperatures of 0 and 1. (b) Same as (a) but \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\). (c) Same as (a) but \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^6\). (d) Values of the cost function J (Eq. 7) plotted against the assumed \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) (horizontal axis) and the number of iterations (vertical axis).

Evolution after the 4DVarMiC solutions

Flow velocity and the Nusselt number within and after the ATW (Assimilation Time Window). (a) Time series of the observed horizontal flow velocity at a depth of \(z = 0.25\) (12.5 mm), with horizontal distance on the horizontal axis and time on the vertical axis. Cool colors indicate rightward motion; warm colors, leftward motion. (b) Same as (a), but for a long-term forward simulation initiated from the optimized 4DVarMiC solution with \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\) after 2000 iterations. (c) Time series of the root mean square velocity \(u_\textrm{RMS}\) (Eq. 17) comparing data and the three 4DVarMiC simulations. Yellow shading denotes the ATW. (d) Time series of the Nusselt number at the upper boundary, \(\mathrm{Nu_0}\) (Eq. 18). \(\mathrm{Nu_0}\) from the steady-state analysis (SSA), shown as a blue arrow, is estimated by assuming a constant time-averaged velocity field and using the method of Noto et al.17 (see Fig. S11).

The 4DVarMiC solution in Fig. 3 demonstrates successful reconstruction of thermal structures solely from randomly sampled particle trajectories within a two-minute ATW. We next assess how well the optimized \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) predicts convective dynamics beyond the ATW by continuing forward simulations, as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4a, b compare the time series of observed and simulated horizontal flow velocity at a depth of \(z = 0.25\) (12.5 mm). In the observations (Fig. 4a), the velocity is on the order of \(10^2\) in non-dimensional units (\(\sim\)0.2 mm/s), exhibiting nearly steady convergence and divergence boundaries associated with five major convective rolls. Oscillatory motion near the left wall, with a period of approximately 1.6 minutes, is also visible and attributed to small corner rolls (see intersecting trajectories in Fig. 2a). This behavior is reproduced in the 4DVarMiC simulation beyond the ATW (Fig. 4b), though with a slightly lower oscillation frequency near the left boundary. This may indicate a limitation of 2D modeling, as it is difficult to produce spatiotemporally small structures even with 2D forward simulations given the same Ra (Fig. S13).

Figure 4c presents the time evolution of the root mean square velocity \(u_\textrm{RMS}\) (Eq. 17) for both observations and three 4DVarMiC simulations with different \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) values. Similarly, Fig. 4d displays the Nusselt number at the upper boundary, \(\mathrm{Nu_0}\) (Eq. 18), indicating the ratio of convective to conductive heat transfer. They are commonly used as global indicators to characterize the overall behavior of thermally driven convective flows32. For \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\), both \(u_\textrm{RMS}\) and \(\mathrm{Nu_0}\) remain in close agreement with observations during and after the ATW. For \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^4\), while \(u_\textrm{RMS}\) is consistent during the ATW, it decreases afterward as DA-estimated thermal anomalies dissipate upon reaching the opposite wall (Figs. S4, S10). This leads to a drop in \(\mathrm{Nu_0}\) as well, due to weakened heat advection (Fig. 4d). For \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^6\), \(u_\textrm{RMS}\) is significantly elevated (Fig. 4c), and the upwelling/downwelling zones exhibit large horizontal oscillations, even far from the sidewalls (Fig. S10), resulting in an overestimated \(\mathrm{Nu_0}\) due to enhanced thermal advection (Fig. 4d). Since we are not measuring \(\mathrm{Nu_0}\) directly in the experiment, we estimate it by the time-averaged velocity field with assuming steady-state following the method of Noto et al.17, shown as “SSA” (steady-state analysis) in Fig. 4d and Fig. S11. The result agrees well with that from the 4DVarMiC simulation at \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\). These findings suggest that a well-constrained 4DVarMiC solution is capable of predicting future states beyond the ATW with high fidelity.

Discussion

This study presents several key contributions to the analysis of thermally driven flows. First, we highlight the mechanism by which both the temperature field and Ra can be simultaneously estimated from sparse Lagrangian observations. Our inverse approach enables this simultaneous estimation, which is generally unfeasible in forward modeling frameworks. The advantage stems from fundamental differences in how temperature is constrained. As shown in the Results section, 4DVarMiC reconstructs the temperature field such that the resulting thermal buoyancy force balances the viscous stresses required to reproduce the observed particle velocities, even in the case where the data contains missing particle trajectories (Figs. S8, S9). In contrast, the method proposed by Noto et al.17 assumes a fully-known steady-state velocity field and iteratively adjusts the temperature field to satisfy the heat transport equation. While effective under idealized conditions, this method cannot estimate Ra from data and is instead limited to reconstructing the steady-state thermal structure. Our approach, by contrast, does not assume thermal steady state, and it infers both the thermal structure and Ra as outputs directly constrained by the partly observed Lagrangian data. This makes 4DVarMiC particularly suitable for analyzing unsteady thermally driven viscous systems such as Earth’s mantle, magmatic intrusions, and other geophysical flows where temperature and Ra are not directly measurable but play critical roles in controlling flow dynamics23,24,25,26. In solid Earth systems, among the parameters that constitute Ra, viscosity is especially poorly constrained because laboratory deformation experiments often fail to robustly constrain the temperature dependence of viscosity (i.e., activation energy)36,37.

In this study, we chose not to treat Ra as a direct optimization variable; instead, our focus was on clarifying how the thermal field inferred from sparse trajectories constrains Ra indirectly, and on demonstrating the perspectives from which the two quantities can be jointly restricted. At the same time, estimating Ra as an unknown parameter remains an important direction for future work. Incorporating prior experimental knowledge into a Bayesian framework may provide a natural way to capture the coupled uncertainties of temperature and Ra, thereby enabling more robust joint estimation.

Despite the strengths of our inverse approach, certain limitations in the temperature reconstruction were observed. Specifically, regions with sparse particle observations—such as the right-hand side of the domain (Fig. 2a), where fewer particles were detected due to dim laser illumination, exhibited reduced estimation accuracy. These areas correspond to locations where the optimization failed to capture the expected thermal structure, leading to asymmetries in the reconstructed temperature field. In the present implementation, all particles were assigned equal weights, but this result suggests that spatial variability in observational density could be accounted for by incorporating adaptive weighting schemes. Additionally, the near-boundary regions, particularly the cooled upper boundary and the heated lower boundary, were not accurately reproduced (upper and lower boundaries at \(t=0\) of Fig. S5). This shortcoming is manifested in the anomalous \(\mathrm{Nu_0}\) values at \(t = 0\) in Fig. 4d. Because thermal conduction rapidly enforces boundary temperatures, the initial thermal structure in these regions is less influential on the subsequent flow evolution. We intentionally used a spatially uniform initial temperature field as the initial guess in order to minimize the use of prior knowledge; however, incorporating physically informed priors that reflect the effect of thermal conduction near boundaries—such as preconditioned boundary layers—may improve estimation accuracy in these regions.

Another novel contribution of this study lies in addressing a nontrivial dimensionality issue: how to relate \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}}\) of a quasi-2D experimental system to \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) used in 2D modeling. In our analysis, we determined that \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}} = 1.6 \times 10^6\) corresponds to \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\), based on the inversion results from 4DVarMiC. This estimate was independently supported by a separate set of forward simulations: a 2D model with \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} \sim 3 \times 10^5\) reproduced the same \(u_{\textrm{RMS}}\) as the experimental case with \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}} = 1.6 \times 10^6\) (Fig. S14). Furthermore, the forward simulations showed that a similar level of \(\textrm{Nu}_0\) was obtained under the 2D simulation with \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 6 \times 10^5\) and the 3D simulation with and \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}} = 1.6 \times 10^6\) (Fig. S14). \(\mathrm{Nu_0}\) of the 2D forward simulation with \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}} = 3 \times 10^5\) is slightly lower than that from 4DVarMiC after ATW and SSA under the same \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) (Figs. 4d, S14) because heat transfer is less effective in the 2D forward simulation due to the smaller number and the longer wavelength of convective rolls (Fig. S13) than that observed (Figs. 2a). Thus, consistent results have been obtained from different approaches when comparing \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}}\) and \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\). Such dimensional scaling is of practical importance because 2D models are frequently employed to reduce computational costs, particularly in geoscience applications24,25,26. Our results offer a data-informed framework for translating insights from idealized 2D models into the context of quasi-2D dynamics in natural or experimental convective systems.

While the present experiments targeted a quasi-2D regime, which enabled the 2D implementation of 4DVarMiC to successfully reproduce the observed flow structures, we recognize that systems where three-dimensionality is more pronounced and inertial terms cannot be neglected are beyond the scope of the current framework. As shown by Yanagisawa et al.32, the system investigated here is characterized by strong two-dimensionality and negligible inertial effects, and our formulation was built upon these assumptions. For convective regimes where three-dimensional effects are significant and inertial contributions play a major role, the present governing equations would be insufficient and a dedicated 3D formulation would be required. Nevertheless, the core Marker-in-Cell framework adopted here can be naturally extended to three dimensions, making the development of fully 3D data assimilation methodologies a promising direction for future studies.

While this study has focused on thermally driven convection, density anomalies arising from compositional variations—such as solute concentration—also act as key drivers of convection in many natural and engineered systems. Geological carbon sequestration is a prominent example, where compositional convection governs the dissolution and transport of injected CO\(_2\)38,39,40. These systems often exhibit dynamics analogous to thermal convection, including finger-like instabilities, stratification, and enhanced mixing. The 4DVar framework developed in this study, particularly its Marker-in-Cell implementation, offers a distinct advantage in that it models and tracks individual Lagrangian particles explicitly. This enables the separate treatment of different particles and thus allows for accurate estimation of component-specific transport processes, such as solute advection24,35. As a result, the method can be naturally extended to solutal or thermo-compositional systems, where the interaction between thermal and compositional fields governs the overall dynamics. This represents a promising avenue for future research, where simultaneous estimation of temperature and composition fields from sparse particle trajectories may unlock deeper insights into the coupled multiphysics behavior that characterizes many natural and engineered convective systems.

The present study demonstrates that 4DVar, while classically used to reconstruct past system states within an ATW, can also forecast the future evolution of thermally driven flow beyond the ATW to some extent, analogous to sequential DA in weather forecasting41. This predictive capability, confirmed by forward simulations initialized from optimized states, suggests that 4DVar provides a robust framework for both retrospective and prospective analysis of geophysical systems, complementing previous applications in retrodiction and parameter estimation42,43,44,45. This advantage cannot be achieved with DA based on PINNs, which are typically limited to interpolation within the ATW20. In this study, future prediction beyond the ATW was achieved by extending the forward simulation from the optimized initial state; therefore, the extent of predictive skill is inherently influenced by the Reynolds number, the degree of nonlinearity, and the sensitivity to initial conditions46,47. Although further evaluation is necessary in turbulent or chaotic regimes, our findings underscore the promise of 4DVar as a physically grounded and computationally stable method for time-resolved estimation and forecasting in nonlinear convective systems.

Methods

Laboratory experiment

The top and bottom of the vessel are copper plates to keep the temperature constant at the boundaries, whereas the side walls are transparent acrylic plates whose thickness is 30 mm to approximately realize adiabatic temperature conditions at walls. The working fluid is a dilute xanthan gum aqueous solution (0.02 wt%) that can be treated as a Newtonian fluid in the low range of shear rate O(0.1) /s realized in the experiment32. The Prandtl number of the fluid is 70, which can be regarded as high Pr in the studied range of \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}}\). The Rayleigh number is calculated by the measured temperature difference between the top and bottom plates. We used the data obtained by the temperature difference of 9.0 K for the assimilation, in which \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}}\sim 1.6 \times 10^6\). The flow structure is assured to be quasi-2D at this \(\mathrm {Ra_{exp}}\).

Particle tracking

The motions of tracer particles seeded into the test fluid are recorded on digital image sequences at the spatial resolution of \(\approx 0.1\) mm/pixel and the time resolution of 10 Hz. The particles are detected and labelled in every frame by identifying local peaks on cross-correlation maps computed with a 2D Gaussian distribution48. The detected positions are linked over image frames to create trajectories with the in-house particle tracking code utilized earlier49, building on the nearest-neighbor method and the universal outlier detection50,51 to ensure spatial continuity. Discontinued trajectories are not recovered as they do not influence the subsequent assimilation, but only trajectories longer than 10 frames are utilized. Note that the resultant particle trajectories distribute uniformly neither in space nor time because the laser illumination attenuates with x positions for the opacity of the fluid, not because of the actual particle distributions.

4DVarMiC equations and computation

The 4DVarMiC DA19 is applied to the tracer particle trajectories obtained using the method described in the previous section. The algorithm iteratively solves the forward and adjoint models to minimize a cost function. We consider a two-dimensional, incompressible, highly viscous fluid, and neglect inertial effects.

The forward model includes the equation of motion and the heat balance within a two-dimensional spatial domain with the horizontal distance \(x \in [x_0, x_1] = [0,4]\) = [0, 200 mm] and the vertical distance \(z \in [z_0, z_1] = [0,1]\) = [0, 50 mm] (top left is the origin of the coordinate) and time domain \(t \in [t_0, t_1]\) = [0, 120 sec]:

where \(\psi\) is the stream function, \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) is the thermal Rayleigh number in 2D modeling (Eq. 1), \(\varvec{u}\) is the velocity field, T is the temperature, \(\varvec{x}_i\) is the position of particle i (i = 1, ..., N; N = 7890), and \(\varvec{u}_i\) is the velocity of particle i. The stream function \(\psi\) is defined as

For the equation of motion, zero-slip conditions are imposed for the boundaries of \(x=x_0,x_1\) and \(z=z_0,z_1\). For energy conservation equation, we imposed the insulating condition along \(x=x_0, x_1\), and constant temperatures \(T=0\) along \(z=z_0\) and \(T=1\) along \(z=z_1\).

The cost function J includes the error distance \(J_1\) and the error velocity \(J_2\) between observed and modeled particles and is defined as

where

We used time-dependent hyperparameters \(\alpha = (t-t_0)/(t_1-t_0)\) and \(\beta = 10^{-5} (t-t_0)/(t_1-t_0)\); larger weight is put on the data of the early stages so that the initial condition is efficiently constrained.

The Lagrange multiplier method to minimize J subject to the forward governing equations yields the following adjoint equations:

where \(\varphi\) is the adjoint stream function, \(\tau\) is the adjoint temperature, \(\varvec{\lambda }_i\) is the adjoint position of particle i, and dS is a grid cell.

Forward and adjoint equations are discretized both in space and time. The rectangular grid contains 150 uniform 1-mm-width cells along the horizontal axis and 50 uniform 1-mm-height cells along the vertical axis (Fig. S12), whereas a time step is 0.02 sec, satisfying the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy condition. The forward and adjoint equations are repeatedly solved to update unknown target parameters \(T (t_0)\) and \(\varvec{x}_i\) until J becomes sufficiently small. The \(\mathrm {Ra_{2D}}\) value remains constant throughout the optimization process.

Validation indicators

Two validation indicators were calculated to evaluate the 4DVarMiC results: the root mean square of the velocity field and the Nusselt numbers at the upper boundary, defined as

respectively, where k is the horizontal node index, K is the number of the horizontal nodes \((K=201)\), l is the vertical nodes index, L is the number of the vertical nodes \((L=51)\), \(\varvec{u}_{kl}\) is the velocity at grid node k, l, and \(\varvec{u}_{kl}^\textrm{obs}\) is the observed velocity at grid node k, l calculated from particle motions. When observation is missing, the misfit for the missing part is excluded from the summation. Note that the denominator of the Nusselt numbers, the heat flow in the case where heat transport is completely conductive, is \(\Delta T/h\) in the dimensional form and 1 in the non-dimensional form.

Data availability

The data for this work can be downloaded from Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15495028).

References

Watanabe, H. K. et al. Heterogeneous shell growth of the neustonic goose barnacle Lepas anserifera: Its potential application for tracking floating materials. Mar. Biol. 171(8), 161 (2024).

Matsumoto, K. & Nakamura, M. Syn-eruptive breakdown of pyrrhotite: A record of magma fragmentation, air entrainment, and oxidation. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 172, 1–19 (2017).

Connor, C. B., Hill, B. E., Winfrey, B., Franklin, N. M. & Femina, P. C. L. Estimation of volcanic hazards from tephra fallout. Natl. Hazards Rev. 2, 33–42 (2001).

Shimizu, H. A., Koyaguchi, T. & Suzuki, Y. J. The run-out distance of large-scale pyroclastic density currents: A two-layer depth-averaged model. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 381, 168–184 (2019).

Iwamori, H. Viscous flow and deformation of regional metamorphic belts at convergent plate boundaries. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 108, 1 (2003).

Kuwatani, T., Nagata, K., Yoshida, K., Okada, M. & Toriumi, M. Bayesian probabilistic reconstruction of metamorphic \(P\)-\(T\) paths using inclusion geothermobarometry. J. Mineral. Petrol. Sci. 113, 82–95 (2018).

Kuwatani, T. et al. Recovering the past history of natural recording media by Bayesian inversion. Phys. Rev. E 98, 043311 (2018).

Gerya, T. V., Stöckhert, B. & Perchuk, A. L. Exhumation of high-pressure metamorphic rocks in a subduction channel: A numerical simulation. Tectonics 21, 1–6 (2002).

Warren, C., Beaumont, C. & Jamieson, R. A. Modelling tectonic styles and ultra-high pressure (UHP) rock exhumation during the transition from oceanic subduction to continental collision. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 267, 129–145 (2008).

Müller, R. D. et al. A global plate model including lithospheric deformation along major rifts and orogens since the triassic. Tectonics 38, 1884–1907 (2019).

Capponi, A. et al. Refining an ensemble of volcanic ash forecasts using satellite retrievals: Raikoke 2019. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 6115–6134 (2022).

Apte, A., Jones, C. K. & Stuart, A. A Bayesian approach to Lagrangian data assimilation. Tellus A: Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 60, 336–347 (2008).

Salman, H., Ide, K. & Jones, C. K. Using flow geometry for drifter deployment in Lagrangian data assimilation. Tellus A: Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 60, 321–335 (2008).

Honnorat, M., Monnier, J. & Dimet, F.-X. Lagrangian data assimilation for river hydraulics simulations. Comput. Vis. Sci. 12, 235–246 (2009).

Bauer, C., Schiepel, D. & Wagner, C. Assimilation and extension of particle image velocimetry data of turbulent Rayleigh-Bénard convection using direct numerical simulations. Exp. Fluids 63, 22 (2022).

Agasthya, L., Clark Di Leoni, P. & Biferale, L. Reconstructing Rayleigh-Bénard flows out of temperature-only measurements using nudging. Phys. Fluids 34, 015128 (2022).

Noto, D., Ulloa, H. N. & Letelier, J. A. Reconstructing temperature fields for thermally-driven flows under quasi-steady state. Exp. Fluids 64, 74 (2023).

Weiss, S., Emran, M. S., Bosbach, J. & Shishkina, O. On temperature reconstruction from velocity fields in turbulent Rayleigh-Bénard convection. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 242, 126768 (2025).

Nakao, A., Kuwatani, T., Ito, S. & Nagao, H. Adjoint-based marker-in-cell data assimilation for constraining thermal and flow processes from Lagrangian particle records. J. Geophys. Res.: Mach. Learn. Comput. 2, e2024JH000288 (2025).

Du, Y., Wang, M. & Zaki, T. A. State estimation in minimal turbulent channel flow: A comparative study of 4DVar and PINN. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 99, 109073 (2023).

Clark Di Leoni, P., Agasthya, L., Buzzicotti, M. & Biferale, L. Reconstructing Rayleigh-Bénard flows out of temperature-only measurements using physics-informed neural networks. Eur. Phys. J. E 46, 16 (2023).

Toscano, J. D. et al. AIVT: Inference of turbulent thermal convection from measured 3D velocity data by physics-informed Kolmogorov-Arnold networks. Sci. Adv. 11, eads5236 (2025).

Turcotte, D. & Schubert, G. Geodynamics (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Nakao, A., Iwamori, H., Nakakuki, T., Suzuki, Y. J. & Nakamura, H. Roles of hydrous lithospheric mantle in deep water transportation and subduction dynamics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 5336–5343 (2018).

Yamato, P., Tartese, R., Duretz, T. & May, D. A. Numerical modelling of magma transport in dykes. Tectonophysics 526, 97–109 (2012).

Kawada, Y., Yamano, M. & Seama, N. Hydrothermal heat mining in an incoming oceanic plate due to aquifer thickening: Explaining the high heat flow anomaly observed around the japan trench. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 15, 1580–1599 (2014).

Ahlers, G., Grossmann, S. & Lohse, D. Heat transfer and large scale dynamics in turbulent Rayleigh-Bénard convection. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 503–537 (2009).

Doering, C. R. Turning up the heat in turbulent thermal convection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 9671–9673 (2020).

Letelier, J. A., Mujica, N. & Ortega, J. H. Perturbative corrections for the scaling of heat transport in a Hele-Shaw geometry and its application to geological vertical fractures. J. Fluid Mech. 864, 746–767 (2019).

Noto, D., Letelier, J. A. & Ulloa, H. N. Plume-scale confinement on thermal convection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2403699121 (2024).

Ulloa, H. N., Noto, D. & Letelier, J. A. Convection, but how fast does fluid mix in hydrothermal systems?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL112097 (2025).

Yanagisawa, T., Takano, S., Noto, D., Kameyama, M. & Tasaka, Y. Quasi-steady transitions in confined convection. J. Fluid Mech. 1000, A44 (2024).

Reid, W. H. & Harris, D. L. Some further results on the Bénard problem. Phys. Fluids 1, 102 (1958).

Shishkina, O. Rayleigh-Bénard convection: The container shape matters. Phys. Rev. Fluids 6, 090502 (2021).

Nakao, A., Kuwatani, T., Ito, S. & Nagao, H. Adjoint-based data assimilation for reconstruction of thermal convection in a highly viscous fluid from surface velocity and temperature snapshots. Geophys. J. Int. 236, 379–394 (2024).

Karato, S.-I. & Wu, P. Rheology of the upper mantle: A synthesis. Science 260, 771–778 (1993).

Korenaga, J. & Karato, S.-I. A new analysis of experimental data on olivine rheology. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 113, 1 (2008).

Backhaus, S., Turitsyn, K. & Ecke, R. Convective instability and mass transport of diffusion layers in a Hele-Shaw geometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 104501 (2011).

Letelier, J., Ulloa, H., Leyrer, J. & Ortega, J. Scaling CO\(_2\)-brine mixing in permeable media via analogue models. J. Fluid Mech. 962, A8 (2023).

Paoli, M. Convective mixing in porous media: A review of Darcy, pore-scale and Hele-Shaw studies. Eur. Phys. J. E 46, 129 (2023).

Kalnay, E. Atmospheric Modeling, Data Assimilation and Predictability (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Colli, L., Ghelichkhan, S., Bunge, H.-P. & Oeser, J. Retrodictions of Mid Paleogene mantle flow and dynamic topography in the Atlantic region from compressible high resolution adjoint mantle convection models: Sensitivity to deep mantle viscosity and tomographic input model. Gondwana Res. 53, 252–272 (2018).

Ghelichkhan, S., Bunge, H.-P. & Oeser, J. Global mantle flow retrodictions for the early Cenozoic using an adjoint method: Evolving dynamic topographies, deep mantle structures, flow trajectories and sublithospheric stresses. Geophys. J. Int. 226, 1432–1460 (2021).

Rudi, J., Gurnis, M. & Stadler, G. Simultaneous inference of plate boundary stresses and mantle rheology using adjoints: Large-scale 2-D models. Geophys. J. Int. 231, 597–614 (2022).

Hu, J., Rudi, J., Gurnis, M. & Stadler, G. Constraining Earth’s nonlinear mantle viscosity using plate-boundary resolving global inversions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2318706121 (2024).

Lorenz, E. N. Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow 1 (Routledge, 2017).

Palmer, T. & Hagedorn, R. Predictability of Weather and Climate (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Takehara, K. & Etoh, T. A study on particle identification in PTV particle mask correlation method. J. Vis. 1, 313–323 (1999).

Noto, D., Terada, T., Yanagisawa, T., Miyagoshi, T. & Tasaka, Y. Developing horizontal convection against stable temperature stratification in a rectangular container. Phys. Rev. Fluids 6, 083501 (2021).

Westerweel, J. & Scarano, F. Universal outlier detection for PIV data. Exp. Fluids 39, 1096–1100 (2005).

Duncan, J., Dabiri, D., Hove, J. & Gharib, M. Universal outlier detection for particle image velocimetry (PIV) and particle tracking velocimetry (PTV) data. Meas. Sci. Technol. 21, 057002 (2010).

Nakao, A. Particle data of Rayleigh–Bénard convection and 4DVarMiC results [Data set]. Zenodo (2025).

Wessel, P. et al. The generic mapping tools version 6. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 5556–5564 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sota Takano for conducting the laboratory experiments. Simulation results were visualized using Generic Mapping Tools53. Some part of numerical simulation was performed on the Earth Simulator at JAMSTEC.

Funding

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants (22K14131 and 25K00228) and Joint Research Programs of the Earthquake Research Institute, University of Tokyo (2024-B-01 and 2025-B-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N. conducted data assimilation and wrote the main text. D.N. sampled particle track data and wrote the method section. T.Y. validated the results and wrote the method and result sections. Y.T. set up the laboratory experiments. T.K. conceptualized the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakao, A., Noto, D., Yanagisawa, T. et al. Reconstruction of thermally-driven flows using Lagrangian particle data assimilation. Sci Rep 15, 35838 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19724-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19724-x