Abstract

This study examines how the scarcity women experience returning to the community after prison affects cognitive functioning, leading to impulsive decisions that harm their health. Women (n = 92) with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders were assessed 5–6 months before, 1 month before (n = 59), and 1 month after (n = 66) prison release using cognitive functioning (fluid intelligence, impulsiveness, persistence, attention, pre-occupation), clinical (cravings, mental health, substance use, treatment received), and scarcity measures. We examined: (1) effects of hypothetical scarcity during incarceration on transient cognitive, craving, and clinical variables; (2) real-world changes in cognitive and clinical variables from baseline through release and their correlation with scarcity. Exposure to hypothetical scarcity during incarceration resulted in reduced cognitive persistence and increased craving for drugs or alcohol but did not induce immediate effects on other outcomes. During real re-entry, 6 of 7 cognitive functioning indicators worsened from baseline to post-release. More post-release scarcity was associated with worse cognitive functioning, more cravings, worse mental health, more substance use, and less treatment received. Worse post-release cognitive functioning partially mediated effects of scarcity on post-release cravings and mental health. Findings suggest scarcity at re-entry can limit women’s choices and their ability to think clearly to make those choices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are 8 million releases from U.S. jails or prisons each year1,2. Women leaving prison are a particularly vulnerable group, with high rates (~ 50%) of co-occurring mental health (e.g., psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder) and substance use disorders3.

Re-entry from prison to the community often involves high stakes competing demands, trade-offs, and scarcity (see Table 1 for glossary of terms). Women with co-occurring disorders (COD) in particular face multiple demands, typically with few resources4,5. To re-integrate successfully, they must procure a safe place to live, a legal income, find and maintain treatment for mental health and addiction, meet family obligations, and avoid victimization. Discharge planning and community services are limited and fragmented4,6,7,8. Individuals may not find the treatment, housing, job, or other resources they need, even after contacting several agencies. Exposure to drugs is ubiquitous in most available living environments9 including shelters, posing near constant challenges to self-control. Many see few options other than to return to partners or others who are violent toward them5,10. Requirements of parole officers and treatment providers or other agencies may conflict6. Many women leaving prison are single parents, making child care and custody primary concerns. Competing demands of obtaining housing and a livelihood, trying to reunite or rebuild relationships with children, and maintain their own physical and mental health may be located miles apart and women often have no transportation. Upon re-entry, women are often faced with large and consequential trade-offs: meeting a need in one area may compromise another (e.g., the only housing available is with a relative who uses drugs; the only treatment facility available is 40 miles away from her children).

Laboratory research in the fields of behavioral economics and cognitive psychology demonstrates that under similarly challenging circumstances, decision-making ability can be impaired. Research finds that dealing with scarcity (defined as any deficit—in money, time, social ties or any resource—that people experience in trying to meet their needs) creates its own mindset, changing how people look at problems and make decisions11. Specifically, scarcity automatically elicits greater cognitive engagement with immediate problems that concern the scarce resource11, leading to neglect of other important issues (e.g., health, employment) with potentially serious long-term consequences. Attentional engagement with problems of scarcity requires cognitive resources that would otherwise go to other concerns, decreasing fluid intelligence and the ability to inhibit impulses11. The difference in cognitive capacity (fluid intelligence, ability to inhibit impulses) in the same individual under scarce and not scarce circumstances can be as much as 13 IQ points12. This effect has been both induced experimentally and observed in naturalistic studies of subsistence farmers12.

A second line of research13,14 suggests that, in the short-term (i.e., over a day), self-control is a finite and depletable resource. Once expended, additional attempts at effortful control are impaired (i.e., self-control is “depleted”). Depletion in one domain leads to less self-control in other domains15. Decision-making, planning, and initiative draw from the same cognitive resource, so depletion caused by one of these could affect the others14. Tasks that deplete self-control include controlling attention13,15, controlling emotion13,15, controlling impulses/resisting temptation15, and being the target of stigma16, a common experience for women leaving prison. In lab studies (typically with undergraduate students), individuals randomized to depleting tasks perform worse than those randomized to non-depleting tasks on subsequent tests of impulse control17,18,19, persistence20, logic and reasoning13, and social processing (e.g., resisting persuasion, processing social cues)15. Of relevance for prison re-entry, individuals randomized to depleting tasks are more likely than non-depleted participants to be violent, aggressive, or hostile17,21,22,23, to engage in potentially risky sex in hypothetical scenarios18, to lie or cheat for profit24, to expose themselves to temptation24, and to engage in addictive behaviors25,26.

Nonrandomized community studies have also shown that regulating urges and desires (including for sleep, food, or leisure) exacts a cumulative effect over a day27,28,29. Community studies also show that interpersonal conflict (which is common in settings where women go after leaving prison) is highly depleting, and that depletion leads to more conflict14. Depletion decreases deliberation and increases reliance on habit30,31. For women with COD leaving prison, habits can include drug use, poor health behaviors, and abusive relationships.

Finally, randomized lab studies show that making choices is mentally depleting, especially when trade-offs have large consequences32. Decisions requiring many trade-offs lead to reduced self-control (less physical stamina, reduced persistence, more procrastination) and impaired cognitive performance33, and render subsequent decisions prone to favoring impulsive, extreme32, and often regret-inducing options27,34. Re-entry is filled with near-constant temptation and large consequences for mistakes (violence, substance relapse, incarceration). Scarcity adds pressure by leaving little room for error – one poor decision can trigger cascading negative consequences11.

This study examines how the context of re-entry affects the cognitive processing of women with COD, leading to poor or impulsive decisions that put their health at risk (e.g., substance use, lack of treatment, risky sex) during the vulnerable re-entry period. Instead of focusing on intrinsic deficits of individuals who are incarcerated that may lead to poor decision-making, we hypothesize that circumstances of re-entry (i.e., scarcity, tradeoffs, challenges to self-control) interfere with cognitive processes needed for successful re-entry and COD recovery. There is some recognition that practical barriers in communities and services available contribute to failures at re-entry4,7. However, if the cognitive effects of scarcity and depletion hold for women with COD leaving prison, one implication would be that society’s failure to devote adequate resources to discharge and re-entry services may contribute to some women having not only practical challenges, but being cognitively overwhelmed and able to do only what is familiar (like substance use or petty crime). This may be part of the reason that women and their providers describe supportive re-entry services as so essential, and why without them, some “get defeated so quickly.”5.

Results extend findings from lab and community samples to a high-risk clinical population, examining a novel mechanism (i.e., contextually driven decrements in cognitive functioning) that leads to re-entry failures and opens new avenues for intervention. Characteristics of individuals leaving prison that can profoundly affect health behaviors (fluid intelligence, self-control) previously thought to be static individual difference variables may be influenced by contextual factors and thus more open to remedies than previously believed.

This study examines a novel population. Lab studies on self-control depletion and scarcity have typically enrolled undergraduate students or other convenience samples, but not clinical samples. Observational studies of scarcity have used subsistence12 or convenience samples, but not clinical ones, and have largely focused on cognitive and financial rather than clinical outcomes.

Scarcity and depletion effects are stronger in psychologically vulnerable individuals, such as those with low trait self-control15. To demonstrate proof of concept, this study focuses on re-entering women with COD because they are psychologically vulnerable, face post-release tradeoffs in managing mental health and addiction, represent a high-risk group needing more services and research, and because COD is common among women leaving prison3.

Method

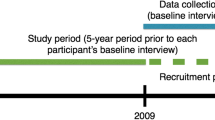

Participants (n = 92 women in prison with COD) were assessed 5 months before re-entry (before re-entry stressors became salient; twice, about one week apart), 1 month before re-entry (n = 59), and 1 month after re-entry (n = 66; Suppl Table 1). The first assessment provided baseline measurements. Because cognitive effects of scarcity are fluid and change when circumstances change, the study’s two components (an in-prison experiment with hypothetical scenarios and a naturalistic longitudinal study) did not influence each other’s results (see Table 2.). Including both components helped to strengthen study conclusions and eliminate alternative explanations. The trial was approved by the Michigan State University (FWA00004556) and Brown University (FWA00004460) Institutional Review Boards. All participants provided informed consent.

Participants

Women with COD were recruited from two state women’s prisons in the Midwest and the Northeast 5–6 months prior to their expected release date (before re-entry concerns were salient). Eligibility criteria included: (1) a DSM-5 mental health disorder [lifetime schizophrenia, schizoaffective, or bipolar disorder; and/or current major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia]; (2) moderate to severe substance use disorder (4 + DSM-5 criteria met35) in the month prior to incarceration, as assessed by the SCID-536; (3) 5 + on a 1–10 scale of desire to quit using at least one substance on the Thoughts About Abstinence scale (TAA)37 and reported they have something to lose if they do not quit, so that we could evaluate their success in trying; and (4) could speak and understand spoken English. Women unable to consent or provide reliable data (e.g., floridly psychotic) were excluded. Recruitment involved flyers, announcements, and individual meetings. Due to funding and time constraints, we consented the final 16 of the 92 participants to the first two assessments (exposure to hypothetical scarcity) only.

Procedures

Randomized experiment with exposure to hypothetical scarcity during incarceration (between-subjects; Hypotheses 1a-1c)

This experiment attempted to: (1) replicate lab findings in the target population, and (2) extend previous findings to clinical outcomes. The experiment was conducted during two visits, one week apart, five months before release. At the first visit, women were screened, consented, and completed baseline assessments (see Suppl Table 1). At the 2nd visit, we randomized participants to consider a set of high scarcity (few resources, large trade-offs) or low-scarcity scenarios (more resources, few trade-offs) hypothetical re-entry scenarios to induce a high or low scarcity mindset (see Suppl Table 2). Dr. Johnson drafted the scenarios based on interviews with almost 200 women leaving prison5,10,38,39,40,41,42 and then the research team reviewed, discussed, and edited them for clarity and correspondence to scarcity and depletion constructs. Scenarios were piloted among 10 potential participants for clarity and appropriateness using think aloud and focused probing cognitive-based interviews and then finalized by the research team.

Cognitive and clinical analogue outcomes were measured immediately afterward, using unrelated cognitive tasks (i.e., not answers to questions posed during the experiment). We also asked how well each scenario matched each woman’s experience of scarcity and trade-offs.

Effects of actual scarcity at community re-entry on cognitive and clinical outcomes (within-subjects; Hypotheses 2a-2e)

Naturalistic observation (i.e., repeated administration of cognitive tasks) over time from baseline to post-release examined the effects of actual re-entry experiences on cognitive functioning and the relationship between cognitive functioning and clinical outcomes. Naturalistic observation examined: (1) whether cognitive decrements were observed during actual re-entry, (2) whether cognitive variables had the expected associations with scarcity and with clinical outcomes, and (3) whether impaired cognitive functioning explained the effects of post-release scarcity on post-release clinical outcomes.

Assessments

Assessments (Suppl Table 1) took place in prison or in community locations that were safe, convenient for participants and had space for private interviews. Trained research assistants were masked to study hypotheses. Cognitive assessments were computerized to standardize inter-task interim period and assessment order. Task versions were counterbalanced across pre-release and post-release interviews. Practice effects worked against our hypotheses. Depleting dependent tasks (e.g., handgrip) were administered last15.

Sample descriptors

Eligibility was established using the TAA and SCID5. Descriptive information included demographics, number of prior arrests, trait self-control (Consideration of Future Consequences-Immediate; CFC43), and distress tolerance (Distress Tolerance Scale; DTS44).

Independent variables and predictors

Independent variables

Were experimental condition (Hypotheses 1a-c) and time (Hypotheses 2a-e). Scarcity (predictor) indicators included the number of areas in the Effectiveness Obtaining Resources (EOR45) scale in which women had current unmet needs (e.g., housing, transportation, employment, treatments, identifying documents, Medicaid enrollment, childcare, etc.), perceived effectiveness in addressing those needs (EOR), a 6-item food insecurity questionnaire from the U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module46, 6 yes/no questions (shown in Table 3), and monthly household income.

Cognitive dependent variables

Fluid intelligence was assessed using four (24 item) versions of Raven’s Progressive Matrices47, a well-validated measure of the capacity to solve problems48 that is not dependent on literacy47. This test presents a sequence of shapes with one shape missing, and requires participants to choose which shape best fits the missing space47. Ability to inhibit impulses was assessed with the Flanker Inhibitory Control & Attention Test from the NIH Toolbox49, which requires participants to exert selective attention by focusing on a stimulus while inhibiting attention to the stimuli flanking it50. These are standard, well-validated measures of cognitive control that have been used in both literatures from which we draw. Attention was measured with the Flanker Task and with reaction time to an unpredictable stimulus with a long lag. Persistence was measured using the most commonly used task in the self-control depletion literature15, the hand-grip task, in which participants are asked to hold a spring-loaded handgrip to exhaustion51,52. Time spent maintaining a grip serves as the outcome52. We also assessed cognitive persistence using visual search without a target53. Preoccupation with re-entry-related worries was assessed using items adapted from the PACS and the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS54) assessing how frequently and how much time in a day is spent thinking about re-entry related issues, interference due to these thoughts, and perceived degree of control over one’s attention to these thoughts. An implicit measure of preoccupation (or “tunneling”) was simple reaction time to a visual stimulus with a long and unpredictable lag. Ability to delay gratification was measured with a simple 3-question measure of temporal discounting (“Would you rather have $20 now or $60 in 2 weeks?”).

Clinical dependent variables

Momentary fluctuations in cravings for one’s substance of choice and perceived ability to resist use were assessed using the Bohn Alcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ55), adapted to ask about women’s most-craved substance. Past-week craving for substances generally was measured using the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS56). Motivation and confidence to abstain from substances were assessed using an expanded TAA37. As in Gailliot18, craving for and perceived ability to resist risky sex and illegal behavior were assessed with hypothetical scenarios. Mental health symptoms were measured with the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)57 and the state anxiety subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)58. Baseline (evaluating behavior in the 3 months prior to incarceration) and post-release (1 month after release) substance use (drug using or heavy drinking [4 + drinks] days) was assessed using the Timeline Followback calendar method59,60. We collected post-release urine drug screens using the 5-drug Onsite CupKit. Ability to generate reasons for attending post-release mental health and substance use treatment was assessed by asking participants to list as many reasons as they could. Perceived ability to find and persist in treatment was assessed using items adapted from the TAA. Mental health and substance use treatment and medication compliance was assessed using Treatment Services Review (TSR)61 items (How many days have you seen a professional about a mental health or substance use issue since release? How many days have you taken a medication for a mental health or substance use issue since release?).

Analyses

Primary tests were two-sided with α = 0.05.

Randomized experiment with exposure to hypothetical scarcity during incarceration (between-subjects; Hypotheses 1a-1c).

We tested the hypothesis that, relative to those given the less-scarce re-entry scenarios, women given the scarce set would show greater decrements from baseline on (a) fluid intelligence (Raven’s) and ability to inhibit impulses (Flanker), (b) cognitive and physical persistence, lower perceived ability to find and persist in post-release treatment, lower ability to generate reasons for doing so, and (c) higher craving for and lower perceived ability to resist substances and other risky (sexual, illegal) behaviors. Differences between hypothetical scarce and non-scarce conditions were estimated from general linear models (one model for each outcome) that included baseline version of each outcome as a covariate.

Manipulation checks

We administered a brief questionnaire at the end of each of the 3 scenarios to assess how well each scenario fit each woman’s specific experiences of scarcity and how much stress the scenario caused (rated on a 1–10 scale). We examined whether perceived similarity or current stress moderated the effects of scarce scenarios on outcomes. This allowed us to eliminate scenario dissimilarity or stress as likely alternative to explanations for findings.

Effects of actual scarcity at community re-entry on cognitive and clinical outcomes (within-subjects; Hypotheses 2a-2e).

Hypothesis 2a

We tested the hypotheses that preoccupation with re-entry-related worries would increase and that fluid intelligence, ability to inhibit impulses, attention, and cognitive and physical persistence would decrease from Day 1 (baseline) to follow-up assessments (1 month before release and 1 month after release) using matched pairs t-tests within participants.

Hypotheses 2b-2d

To simplify examination of associations among scarcity, cognitive, and clinical continuous outcomes and reduce the number of tested associations (from 138 possible), principal component analyses were used to create summary scores (Suppl Table 3). Proportions of heavy drinking and drug use days post-release were summed into an index. A similar index was created reflecting receipt of substance use care, mental health care, and medication adherence (Suppl Table 3). Hypotheses 2b (more post-release scarcity will be associated with worse post-release clinical outcomes), 2c (more post-release scarcity will be associated with worse cognitive functioning), and 2 d (worse post-release cognitive functioning will be associated with worse post-release clinical outcomes) using Pearson correlations among summary scores.

Hypothesis 2e

We tested the hypothesis that post-release cognitive functioning would mediate the effects of post-release scarcity on post-release clinical outcomes. Mediation analyses were performed using Preacher and Hayes bias-correcting analytic strategy implemented in PROCESS macro in SAS 9.4. Using 5,000 bootstrap samples, we estimated total effect of scarcity on clinical outcomes and its partition into the direct effect and indirect effect via the mediator. Confidence interval (CI) for the indirect effect that did not include zero supported mediation.

Statistical power

Randomized exposure to hypothetical scenariosBased on the literature, the mean between-groups effect size for randomized studies of self-control depletion was d = 0.62 (95% CI d = 0.57–0.67)15. Mani et al.’s study with a similar design to ours found between-groups effect sizes of scarcity of d = 0.88-0.9412. Given the available N = 41 and N = 42 in each of two groups in this study, differences corresponding to the effect size Cohen’s d = 0.62 were detectable as statistically significant with power of 0.80 or greater in two-sided tests at 0.05 level of significance. Naturalistic observation. Mani et al. found a within-subjects effect size of d = 0.65 using a similar design12. We were only able to follow the first 66 participants longitudinally because we ran out of time near the end of the study. Given the range of N = 57 to 66 observed pairs of measures (baseline to pre-release or baseline to post-release) across outcomes, the detectable effect sizes Cohen’s d in matched pairs tests ranged from 0.35 to 0.38.

Results

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 3. The flow of participants through the study is shown in Suppl Fig. 1. Urine drug screen results were available for 52 of the 66 participants completing post-release interviews (some interviews occurred in locations without restrooms). Only 5 cases who denied post-release drug use had positive urine drug screens.

Randomized experiment with exposure to hypothetical scarcity during incarceration (Hypothesis 1a – 1c; n = 89)

Immediately following exposure to scarce or non-scarce scenarios on Day 2, relative to the control condition and controlling for baseline values, participants in the scarce condition had significantly lower cognitive persistence and significantly higher cravings for their most-craved substance than did those in the non-scarce condition, with moderate to large effect sizes (Table 4). However, they did not show significantly lower fluid intelligence (Raven’s scores), ability to inhibit impulses (Flanker test accuracy score), physical persistence (hand grip), perceived ability to find and persist in treatment post-release, ability to generate reasons for doing so, or perceived ability to resist substances, risky sex, or crime (Table 4).

Manipulation checks

We did not find that similarity or stressfulness moderated the relationship between scarce vs. non-scarce scenarios on outcomes, eliminating these as likely alternative explanations for findings. Women’s perceptions of how similar to their own situations and how stressful each of the three hypothetical scenarios were varied, using the full 1–10 range for all 6 questions (means = 4.0 to 5.2, standard deviations = 3.1 to 3.7).

Effects of actual scarcity at community re-entry on cognitive and clinical outcomes (Hypotheses 2a-2e; n = 51–66)

Hypothesis 2a. Within-subjects changes in hypothesized cognitive variables over time (baseline, 1 month prior to release, 1 month after release; Table 5).

At one month before release, participants showed medium to large decreases in attention and ability to inhibit impulses (Flanker accuracy score, Flanker response time, visual stimulus with a long lag) and cognitive persistence compared to baseline (5 months before release). This may suggest that, a month prior to release, women were already starting to have cognitive energy consumed by post-release issues. At one month after release, participants showed even larger decreases in fluid intelligence (Raven’s scores), attention and ability to inhibit impulses (Flanker accuracy score, Flanker response time, visual stimulus with a long lag), cognitive persistence, and physical persistence compared to baseline. Pre-occupation with re-entry related worries (Y-BOCS scores) did not change significantly over time.

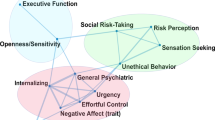

Factor analysis for Hypotheses 2b-2e

Principal component analyses to reduce the number of potential tested associations among scarcity, cognitive, and clinical outcomes resulted in one factor for scarcity measures, two for cognitive functioning, and a factor reflecting mental health symptoms and cravings (Table 6; Suppl Table 3).

Hypothesis 2b. More post-release scarcity will be associated with worse post-release clinical outcomes (Tables 5 and 6)

Relative to those experiencing less post-release scarcity, women experiencing more post-release scarcity reported worse mental health and cravings (r = 0.67), more substance use (r = 0.35), and less treatment and medication adherence (r = 0.36), with moderate to large effect sizes (Table 6). Mediation models also showed direct effects of scarcity on cravings and mental health symptoms, substance use, and treatment/medication (Table 7). Specifically, more post-release scarcity predicted worse mental health and cravings, more substance use, and lower receipt of treatment and medication adherence.

Hypothesis 2c. More post-release scarcity will be associated with worse post-release cognitive functioning (Table 6)

t-release scarcity will be associated with worse post-release cognitive functioning (Table 6)

Relative to those experiencing less post-release scarcity, women experiencing more post-release scarcity had worse cognitive functioning for one of the cognitive functioning factors (Cognitive Functioning Factor 2, r = −0.36) but not the other (Table 6).

Hypothesis 2d. Worse post-release cognitive functioning will be associated with worse post-release clinical outcomes (Table 6)

Women with worse functioning on Cognitive Functioning Factor 2 had worse post-release mental health and cravings (r = 0.51), but not post-release substance use or receipt of treatment. Cognitive Functioning Factor 1 was not associated with post-release mental health and cravings, substance use, or receipt of treatment (Table 6).

Hypothesis 2e. Post-release cognitive functioning will mediate the relationship between post-release scarcity and post-release clinical outcomes

Cognitive Functioning Factor 2 significantly mediated the association between post-release scarcity and worse mental health and cravings (see Table 7, indirect effects). In other words, at 1 month after release, women who experienced more scarcity had worse mental health and cravings partially because they had worse cognitive functioning (on Factor 2 measures). Cognitive functioning factors did not mediate (or explain) the effects of post-release scarcity on post-release substance use or treatment.

Discussion

This study examines how re-entry context affects the cognitive functioning of women with COD, worsening mental health and priming impulsive decisions that put their health at risk. It extends findings on the effects of scarcity and self-control depletion to a clinical population (women leaving prison with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders), examining a novel, important mechanism by which prison re-entry mental health failures may occur and opening new avenues for intervention.

Results suggest that difficult conditions women with COD may experience at release (i.e., scarcity, trade-offs, constant challenges to self-control) can limit both the choices of women with COD and their ability to think clearly while making those choices. Specifically: (1) women’s fluid intelligence, ability to inhibit impulses, attention, and cognitive and physical persistence all worsened significantly from baseline to 1 month post-release (Table 5); (2) compared to those experiencing less scarcity after release, women who experienced more scarcity after release had worse cognitive functioning (more difficulty focusing on things other than re-entry related worries, less ability to delay gratification, lower cognitive persistence), more cravings, worse mental health, more substance use, and received less treatment (Table 6); and (3) women who experienced more post-release scarcity had worse mental health and cravings than the others partly because they had worse cognitive functioning (specifically, more difficulty focusing on things other than re-entry related worries, less ability to delay gratification, and lower cognitive persistence; see indirect effects of Cognitive Factor 2 in Table 7). In other words, women with COD showed significant declines in cognitive functioning post-release, and those facing greater scarcity had worse mental health and cravings—partly due to their worsened cognitive functioning.

When women with COD do poorly after prison release, society and even providers often solely blame the woman5. However, policymakers and residents can influence scarcities in their communities that impact individuals’ ability to re-integrate62. These include accessibility of housing, safety, health and mental health care, drug treatment, transitional employment, food, safety, transportation, and other practical needs like ID and childcare. Communities can also make services easier to navigate for individuals with impaired cognitive functioning, whether due to scarcity or other causes (e.g., head injuries, developmental delays, dementia). Specifically, mental health, substance use, and other health and social services (disability support, public housing) could be designed to be less cognitively demanding (requiring clients to track multiple details, paperwork, etc.) and more fault-tolerant11 (so that small failures do not cause a complete breakdown of services or reincarceration for technical violations). Providing one easy access point for health, mental health, substance use, housing, employment, and other services may also simplify the cognitive demands of help-seeking.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study included rigorous experimental procedures (independent experimental and naturalistic components, counter-balanced Raven’s tests, practice effects that worked against hypotheses, manipulation checks) to minimize alternative explanations and reduce noise. The study also featured a comprehensive set of computerized cognitive tasks and clinical assessments in a high-risk, difficult to follow population in prison and after release in two states. To our knowledge, no one has administered tasks like these in prison and after release before.

Limitations included missing data, varied COD diagnoses, and having to recruit the final 16 participants for the baseline and in-prison experiment only, limiting sample sizes for some analyses. Actual scarcity had expected effects. However, hypothetical scarcity scenarios were less impactful, possibly because participants were exposed to before post-release issues were salient or scenarios had mixed similarity to participants’ experiences. Findings of this proof-of-concept study may not generalize to women without COD or to men leaving prison.

Conclusions

Difficult re-entry conditions can limit women’s options as well as their ability to clearly consider those options. In this study, post-release scarcity was associated with worse mental health, drug/alcohol cravings, substance use, less treatment received, and impaired cognitive functioning on some measures. One in 5 U.S. adults who die by suicide63, 1 in 4 individuals with HIV64, more people with serious mental illness in all mental health facilities combined65, and a significant proportion of individuals with substance use disorders pass through jail or prison each year. Strengthening and simplifying post-release services by ensuring basic needs and making health and social services simpler to access and more fault-tolerant11 could have significant public health impact.

Data availability

Datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available to qualified researchers upon request (email the corresponding author at [JJohns@msu.edu](mailto:JJohns@msu.edu)). Data are not shared to a public repository given additional protections to participants recruited in prison and because we did not obtain participants’ consent to post datasets publicly.

References

Zeng, Z. Jails report series: Preliminary data release. Preliminary Data Release, Jail Inmates. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/jails-report-series-preliminary-data-release-2023 (2024).

Carson, E.A. Prisoners in 2022 - Statistical Tables. 2023. https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/p22st.pdf (2023).

James D, Glaze LE. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. (2006).

Draine, J., Wolff, N., Jacoby, J. E., Hartwell, S. & Duclos, C. Understanding community re-entry of former prisoners with mental illness: A conceptual model to guide new research. Behav. Sci. Law 23, 689–707 (2005).

Johnson, J.E., Schonbrun, Y.C., Peabody, M.E., Shefner, R.T., Fernandes, K.M., Rosen, R.K., Zlotnick, C. Provider experiences with prison care and aftercare for women with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorder: Treatment, resource, and systems integration challenges. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 1–19 (2014).

Blakeslee, S. Women’s experiences in the United States criminal justice aftercare system. J. Fem. Fam. Ther.: An Int. Forum. 24(2), 139–152 (2012).

Kellett, N. C. & Willging, C. E. Pedagogy of individual choice and female inmate reentry in the U.S. Southwest. Int. J. Law Psych. 34(11), 256–263 (2011).

Luther, J., Reichert, E. S., Holloway, E. D., Roth, A. M. & Aalsma, M. C. An exploration of community reentry needs and services for prisoners: A focus on care to limit return to high-risk behavior. AIDS Patient. Care STDS 25(8), 475–481 (2011).

Binswanger, I., Nowels, C., Corsi, K.F., Glanz, J., Long, J., Booth, RE., Steiner. Return to drug use and overdose after release from prison: A qualitative study of risk and protective factors. Add. Sci. Clin. Pract.7 3 (2012).

Johnson, J. E. et al. “I know if I drink I won’t feel anything”: Substance use relapse among depressed women leaving prison. Int. J. Prison. Health 9(4), 1–18 (2013).

Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E. Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. Henry Holt and Company (2013).

Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E. & Zhao, J. Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science 341(6149), 976–980 (2013).

Schmeichel, B., Vohs, K. D. & Baumeister, R. F. Intellectual performance and ego depletion: Role of the self in logical reasoning and ohter information processing. J Pers Soc Psychol. 85(1), 33–36 (2003).

Baumeister, R. F., Andre, N., Southwick, D. A. & Tice, D. M. Self-control and limited willpower: Current status of ego depletion theory and research. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 60, 101882 (2024).

Hagger, M., Wood, C., Stiff, C. & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control. Psychol. Bull. 136(4), 495–525 (2010).

Inzlicht, M., McKay, L. & Aronson, J. Stigma as ego depletion: How being the target of prejudice affects self-control. Psychol. Sci. 17, 262–269 (2006).

Stucke, T. & Baumeister, R. F. Ego depletion and aggressive behavior: Is the inhibition of aggression a limited resource?. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 36, 1–13 (2006).

Gaillot, M. & Baumeister, R. F. Self-regulation and sexual restraint: Dispositionally and temporarily poor self-regulatory abilities contribute to failures at restraining sexual behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 33, 173–186 (2007).

Vohs, K. & Faber, R. J. Spent resources: Self-regulatory resource availability affects impulse buying. J. Consum. Res. 33, 537–547 (2007).

Wallace, H. & Baumeister, R. F. The effects of success versus failure feedback on self-control. Self Ident. 1, 35–42 (2002).

Finkel, E., DeWall, C. N., Slotter, E. B., Oaten, M. & Foshee, V. A. Self-regulatory failure and intimate partner violence perpetration. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97, 483–499 (2009).

DeWall, C., Baumeister, R. F., Stillman, T. F. & Gailliot, M. T. Violence restrained: Effects of self-regulation and its depletion on aggression. J. Experim. Soc. Psychol. 43, 62–76 (2006).

Ordali, E. et al. Prolonged exertion of self-control causes increased sleep-like frontal brain activity and changes in aggressivity and punishment. PNAS 121(47), e2404213121 (2024).

Mead, N., Baumeister, R. F., Gino, F., Schwietzer, M. E. & Ariely, D. Too tired to tell the truth: Self-control resource depletion and dishonesty. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45, 594–597 (2009).

Muraven, M., Collins, R. L. & Nienhaus, K. Self-control and alcohol restraint: An initial application of the self-control strength model. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 16(2), 113–120 (2002).

Shmueli, D. & Prochaska, J. J. Resisting tempting foods and smoking behavior: Implications from a self-control theory perspective. Health Psychol. 28, 300–306 (2009).

Vohs, K. The poor’s poor mental power. Science 341, 969 (2013).

Hofmann, W., Vohs, K. D. & Baumeister, R. F. What people desire, feel conflicted about, and try to resist in everyday life. Psychol. Sci. 23(6), 582–588 (2012).

Muraven, M., Collins, R. L., Shiffman, S. & Paty, J. A. Daily fluctuations in self-control demands and alcohol intake. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 19, 140–147 (2005).

Neal, D. T., Wood, W. & Drolet, A. How do people adhere to goals when willpower is low? The profits (and pitfalls) of strong habits. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 104(6), 959 (2013).

Hofmann, W., Rauch, W. & Gawronski, B. And deplete us not into temptation: Automatic attitudes, dietary restraint, and self-regulatory resources as determinants of eating behavior. J. Experim. Soc. Psychol. 43, 497–504 (2007).

Wang, J., Novemsky, N., Dhar, R. & Baumeister, R. Trade-offs and depletion in choice. J. Mark. Res. 47(5), 910–919 (2010).

Vohs, K. D. et al. Making choices impairs subsequent self-control: A limited-resource account of decision making, self-regulation, and active initiative. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 94, 883–898 (2008).

Pocheptsova, A., Amir, O., Dhar, R. & Baumeister, R. F. Deciding without resources: Resource depletion and choice in context. J. Mark. Res. 46(3), 344–355 (2009).

Hasin, D. et al. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: Recommendations and rationale. Am. J. Psych. 170(8), 834–851 (2013).

First, M. Biometrics research department. The official website for the structured clinical interview for dsm disorders (SCID). http://www.scid4.org/ (2013). Accessed 12–16–13

Hall, S., Havassy, B. & Wasserman, D. Commitment to abstinence and acute stress in relapse to alcohol, opiates, and nicotine. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 58(2), 175–181 (1990).

Johnson, J. E. & Zlotnick, C. Pilot study of treatment for major depression among women prisoners with substance use disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 46(9), 1174–1183 (2012).

Johnson, J.E., Schonbrun, Y.C., Stein, M.D. Pilot test of twelve-step linkage for alcohol abusing women leaving jail. Substance Abuse. (2013).

Johnson, J. E., Williams, C. & Zlotnick, C. Development and feasibility of a cell phone-based transitional intervention for women prisoners with comorbid substance use and depression. Prison. J. 95(3), 330–352 (2015).

Johnson, J. E. et al. Feasibility of an HIV/STI risk reduction program for incarcerated women who have experienced interpersonal violence. J. Interpers. Violence 30(18), 3244–3266 (2015).

Johnson, J., Schonbrun, Y. C., Anderson, B., Timko, C. & Stein, M. Randomized controlled trial of twelve-step volunteer linkage for women with alcohol use disorder leaving jail. Drug. Alcohol. Depend. 227, 109014 (2021).

Joireman, J., Balliet, D., Sprott, D., Spangenberg, E. & Schultz, J. Consideration of future consequences, ego-depletion, and self-control: Support for distinguishing between CFC-Immediate and CFC-Future subscales. Pers. Individ. Differ. 45, 15–21 (2008).

Simons, J. S. & Gaher, R. M. The distres tolerance scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motiv. Emot. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3 (2005).

Sullivan, C. & Bybee, D. Reducing violence using community-based advocacy for women with abusive partners. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 67, 43–53 (1999).

Economic Research Service US Department of Agriculture. U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form. https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8282/short2012.pdf (2012).

Raven, J. The Raven’s progressive matrices: Change and stability over culture and time. Cogn. Psychol. 41, 1–48 (2000).

Engle, R., Tuholski, S. W., Laughlin, J. E. & Conway, A. R. Working memory, short-term memory, and general fluid intelligence: A latent-variable approach. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 128, 309–331 (1999).

National Institutes of Health. NIH Toolbox for the Assessment of Neurological and Behavioral Function. National Institutes of health. http://www.nihtoolbox.org/Pages/default.aspx (2013). Accessed 12/5/13.

Davidson, M., Amso, C. & Anders, L. C. Diamond A Development of cognitive control and executive functions from 4 to 13 years: Evidence from manipulations of memory, inhibition, and task switching. Neuropsychologia 44(2037), 2078 (2006).

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M. & Tice, D. M. Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource?. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 1252–1265 (1998).

Muraven, M., Tice, D. M. & Baumeister, R. F. Self-control as a limited resource: Regulatory depletion patterns. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 774–789 (1998).

Greene, M. & Wolfe, J. M. Global image properties do not guide visual search. J. Vis. 11(6), 1–9 (2011).

Goodman, W. et al. The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale I development, use, and reliability. JAMA Psych. 46(11), 1006–1011 (1989).

Drummond, D. & Phillips, T. S. Alcohol urges in alcohol-dependent drinkers: further validation of the alcohol urge questionnaire in an untreated community clinical population. Addiction 97(11), 1465–1472 (2002).

Flannery, B. A., Volpicelli, J. R. & Pettinati, H. M. Psychometric properties of the penn alcohol craving scale. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 23(8), 1289–1295 (1999).

Derogatis, L. R. & Melisaratos, N. The brief symptom inventory: An introductory report. Psychol. Med. 13(3), 595–605 (1983).

Spielberger, C., Gorssuch, R.L., Lushene, P.R., Vagg, P.R, Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Consulting Psychologists Press Inc. (1983).

Fals-Stewart, W., O’Farrell, T. J., Frietas, T. T., McFarlin, S. K. & Rutigliano, P. The Timeline Followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 68, 134–144 (2000).

Sobell, L. C., Brown, J., Leo, G. I. & Sobell, M. B. The reliability of the alcohol timeline followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug. Alcohol. Depend. 42, 49–54 (1996).

McLellan, A. T., Alterman, A. I., Cacciola, J., Metzger, D. & O’Brien, C. P. A new measure of substance abuse treatment. Initial studies of the treatment services review. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 180, 101–110 (1992).

Western, B. Homeward: Life in the year after prison (Russell Sage Foundation, 2018).

Miller, T. R. et al. Share of adult suicides after recent jail release. JAMA Netw. Open 7(5), e249965 (2024).

Spaulding, A. et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus in correctional facilities: A review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35, 305–312 (2002).

Torrey, E.R,, Kerrnard, A.D,, Eslinger, D., Lamb, R., Pavle, J. More mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals: A survey of the states. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/more-mentally-ill-persons-are-jails-and-prisons-hospitals-survey (2010).

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; R21 MH105626; Johnson). NIMH had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRediT author contribution statement. Conceptualization (JEJ lead, SS supporting). Methodology (JEJ lead, SS and JZ supporting, ES and MR consulting). Software (JZ). Validation (MC, FR, LBG, CW, SA, JEJ). Formal analysis (AS and MC). Investigation (LBG, CW, SA). Resources (SS and JZ). Data Curation (MC and AS). Supervision (JEJ, LMW). Project administration (LBG). Funding acquisition (JEJ lead; SS, ES and MR supporting). Writing – Original Draft (JEJ lead, MC and AS supporting). Writing – Review and Editing (all).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, J.E., Zemla, J.C., Shafir, E. et al. Effects of scarcity on women’s cognitive ability to manage mental health and substance use after prison release. Sci Rep 15, 34655 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19736-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19736-7