Abstract

Uncomfortable ear pressure during vehicle door closure is associated with enhanced vehicle airtightness and an unreasonable reduction in cabin noise. Current computational simulation methods for ear pressure, however, suffer from low accuracy and inefficiency. In this study, we propose a porous medium model to represent the dynamic airflow resistance characteristics of the pressure relief valve, which improves both the efficiency and accuracy of precise ear pressure simulation. Additionally, an optimized sound insulation cover design is shown to effectively improve ear comfort. Using the overset mesh technique in STAR-CCM+, a transient in-vehicle flow field model was established. Model parameters were calibrated experimentally, and the optimization scheme was validated through combined simulation and experimental data. Results demonstrate that removing the silencer cover of the pressure relief valve reduces the peak ear pressure at the third-row right seat by 20%, with all simulation errors at the human ear remaining below 8%. Compared to the traditional fixed-opening model, the porous medium approach significantly improves the accuracy of simulating the actual pressure relief process. The dynamic pressure relief model and the optimized sound insulation cover effectively enhance ear pressure comfort, offering theoretical guidance for balancing door closing sound quality and vehicle sealing performance in automotive engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The dynamic characteristics of a car door closing have a significant impact on the comfort for passengers and drivers1,2,3,4.As the car door closes, a significant volume of air inside the occupant compartment is rapidly compressed, which leading to a transient pressure surge. This sudden pressureacting change acts on the tympanic membrane, causing tissue deformation and resulting in the characteristic sensation of “aural pressure”5. To numerically simulate the transient fluid dynamics during car door closure, aerodynamic models are commonly used for time-dependent analysis6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

In their research, Lee and Hwang16 used a simplified model with dynamic grids to simulate the door-closing process. The relationship between maximum cabin pressure and door-closing angular velocity were examined, and validated through experimental methods. Zhang17 conducted numerical simulations using a simplified vehicle model to investigate the effects of door-closing speed, leakage area and leakage location on ear pressure. They also analyzed the cabin flow field to elucidate the airflow mechanisms during car door closing and proposed mitigation strategies for models exhibiting excessive cabin pressure. Li et al.18 integrated the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) approach with the dynamic mesh technique to investigate the variation trend of the interior pressure during the car door closing process. They derived the effects of the closing speed and closing angle on the interior pressure and put forward solutions like reducing the closing speed and increasing the size of the pressure relief valve to decrease the interior pressure. Su et al.19 applied the Design of Experiments (DOE) method to study the influence of door-closing velocity, vehicle airtightness, and pressure relief valve area. Their study showed that the door-closing velocity and the effective area of the pressure relief valve significantly affected the ear drum pressure sensation, while vehicle airtightness also exerted a certain impact on it. The whole-vehicle airtightness test is employed. This test has to be conducted during the prototype vehicle phase in the later stage of product development. As such, it is not conducive to risk identification and solution optimization in the early stage of product development. Su et al.20 used the STAR-CCM + overset grid method to establish a simplified full-vehicle model, investigating the influence of airflow channel design on occupant ear pressure during door-closing events. Their study focused on optimizing the trunk interior opening area and the effective area of overflow valves, providing actionable solutions that significantly enhance ride comfort. Unadkat et al.21 utilized a k-ε turbulence model to simulate airflow and pressure distributions within the cabin and ventilation ducts during door closure. Their work examined the impact of the ejector rectifier slot’s effective area on peak cabin pressure, which was supported by the experimental validation. Ren et al.22 employed the overset grid method to carry out the simulation calculation of transient ear pressure during door closure. Their study explored the effects of the distance between the interior space and the tailgate sheet metal, and the effective area of the pressure relief valve on the ear pressure inside the vehicle. However, the impact of the dynamic opening of the pressure-relief valve blades on the simulation results was not taken into account. Moreover, the article did not present the ear-pressure test results obtained from the experiments. Additionally, no comparison of the accuracy between the CFD simulation method and the experimental verification was provided.

In previous studies, CFD simulations were conducted based on simplified vehicle models. However, there are significant differences between the simplified model and the actual vehicle configuration. Neither Su et al. (2022) nor Ren et al. (2024) took into account the influence of the dynamic opening of the pressure - relief valve blades on the CFD simulation results in their respective literature. Specifically, Su et al. (2022) employed the whole-vehicle airtightness test, which was carried out in the late stage of product development. In contrast, Ren et al. (2024) did not elaborate on the experimental testing work, and the accuracy of their simulation remained unverified.

This study presents a novel simulation approach that utilizes a simplified porous-medium model to characterize the dynamic aerodynamic resistance characteristics of the pressure- relief valve. In the early stage of product development, this method, through the performance testing of individual pressure - relief valves, incorporates experimental parameters to optimize and calibrate the dynamic airflow resistance of the valve body. Consequently, it can effectively simulate the dynamic airflow resistance characteristics during the door-closing process. Through a comparison between the simulation results and experimental verification, the accuracy is found to be over 92%.

In the early phase of product development, this research is capable of establishing a sophisticated simulation model that encompasses key components such as the steering wheel, seats, and anthropomorphic test devices (ATDs). After completing the system - level simulation analysis, a rectification plan is proposed based on the simulation analysis of the ear pressure during the door - closing process of a specific vehicle model, aiming to optimize the in - vehicle ear pressure. The optimized simulation results indicate that both the flow field and the ear - pressure variations during the door - closing process have been improved. Further analysis of the main factors influencing the peak ear pressure during door - closing provides a reference for optimized design to enhance the acoustic quality performance of the product.

Numerical simulation

Governing equations of fluid dynamics

The ear pressure during vehicle door closing is assumed to satisfy the mathematical statements of three fundamental physical principles: the conservation of mass, the conservation of momentum, and the conservation of energy. These principles are mathematically expressed to describe the phenomenon22,23:

where ρ is the density of the fluid; u, v and w are the velocity components in the x, y, and z directions, respectively; p is the pressure on the fluid element; ueff is the turbulent viscosity coefficient; t is time; ST represents internal heat sources and the portion of mechanical energy converted into heat due to viscous effects; K is the fluid thermal conductivity; Cp is the specific heat capacity; and T is the temperature24.

Model development and boundary conditions

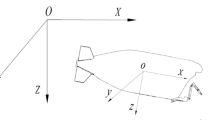

This study develops a transient aerodynamic simulation model for the door-closing process based on an SUV model25,26,27,28,29,30. The vehicle’s dimensions are as follows: length 5025 mm, width 1995 mm, and height 1800 mm.

Firstly, the vehicle geometry model was cleaned, which included geometric cleanup and surface meshing of the vehicle exterior, tires, doors, complete interior components, and dummies. The pre-processed model was then imported into STAR-CCM + for surface mesh reconstruction and volume meshing (Fig. 1).

The simulation model incorporates detailed interior data, it including the steering wheel, dummies, seats, interior ventilation grilles, and pressure relief valves. The configuration of the open door and the interior layout are illustrated in Fig. 2.

The door-closing ear pressure simulation uses the SUV model as the research subject. In STAR-CCM+, computational domains and refined mesh regions were created through component operations31,32,33,34,35. The dimensions and boundaries of the computational domain are shown in Fig. 3, and the size of the computational domain are L = 12 m, W = 8 m, and H = 5 m. In this simulation, the boundary conditions are configured such that the ground of the computational domain is defined as a Wall boundary, while the remaining surfaces of the computational domain are set as Pressure Outlet boundaries. Concerning the mesh quality, the Two-Layer All y + Wall Treatment was implemented. In the simulation model, the Y + values range from 0 to 190. Additionally, the skewness angle of the mesh is maintained within the range of 0 to 85 degrees. The Realizable K-Epsilon Two-Layer turbulence model is employed, along with the activation of the Ideal Gas assumption. This setup enables the simulation of compressible gas flow, allowing for an effective solution of the gas turbulence issues during the door-closing process. For the transient door-closing simulation, the time step is set to 0.001 s. The total computational time is 1 s. The simulation of a single model takes approximately 70 h (utilizing 128 CPUs), and the achieved accuracy of 92% meets the requirements of the project development. It should be noted that an excessively small-time step will lead to an increase in computational time, whereas an overly large time step may compromise the accuracy of the results.

The computational domain was generated by performing a subtractive operation between the computational domain and the vehicle model, resulting in the simulation fluid domain, also known as the primary domain, which is shown in Fig. 4. Within the components, a block enclosing the driver’s door was created as the door’s computational domain, referred to as the overlapping domain. Both the driver’s side door and the enclosing block were meshed separately within this computational domain. In this study, the boundary condition for the surface, specifically the block surface, was set as an overlapping mesh.

In their study, Wang36 introduced the basic theories of CFD analysis, along with methods for mesh generation and boundary setting in flow field simulations. Su37 studied the effects of airflow pressure relief channels and cavity volume on ear pressure during door closure, using a hemispherical computational domain with an 8-meter radius for the main vehicle simulation. Based on aerodynamic simulation and experimental research from Wang and Su, and references17,38,39, this paper considers the dynamic gas flow and pressure distribution changes in both the external flow field of the vehicle and the internal flow field of the passenger compartment40,41,42,43,44. A rectangular main domain and polyhedral mesh are used for transient aerodynamic simulation and modeling of the internal flow field during door closure. Surface and volume mesh are generated for overlapping domains, with their size consistent with the refined regions of the main domain. The simulation applies local refinement to key areas. The mesh size for the main driver’s side door is set to 8 mm, while key airflow channels, Such as the pressure relief valve and interior grille, are refined to a minimum mesh size of 1 mm and a maximum of 2 mm. Figure 5 illustrates the meshed results of the vehicle body, and the total mesh consists of approximately 55 million cells based on mesh sensitivity study.

In this study, the Overset grid technique is employed to simulate the motion of the vehicle door. A local coordinate system is established at the hinge of the vehicle door. Meanwhile, the parameters of the door-closing curve are imported to achieve the transient motion of the vehicle door around the hinge. Figure 6 shows the door closing speed, which is measured by using the door speed sensor in the real SUV car test and it is used as input data for the simulation model.

As shown in Fig. 7, a single performance test was conducted on the pressure relief valve, and multiple sets of data on the pressure drop and volumetric flow rate of the pressure relief valve were obtained through the test. The test data of pressure drop versus flow rate are presented, which is shown in Fig. 8.

Based on the law of Forchheimer, the inertial resistance coefficient and viscous resistance coefficient of the wind resistance of the pressure relief valve can be derived from the quadratic polynomial of the pressure gradient and velocity, as indicated by the following formula. The test data of the pressure relief valve are fitted by selecting the trend Line and adopting a quadratic polynomial, where the intercept of the quadratic function is set to 0. As depicted in Fig. 8(b), the resistance curve of the pressure relief valve is ultimately obtained. The polynomial formula is as follows:

where ∆p represents the pressure drop data obtained from the test, L is the thickness of the pressure relief valve in the direction of air flow, and v is the wind speed, which can be calculated by the air volume and ventilation area of the pressure relief valve. α is the inertial resistance coefficient, and β is the viscous resistance coefficient. The quadratic coefficient represents the inertial resistance coefficient of the pressure relief valve, which is 209.04 kg/m4, while the Linear coefficient represents the viscous resistance coefficient, which is 126.93 kg/m3⋅s. Finally, the dynamic pressure relief resistance parameters of the valve were input into STAR-CCM + for simulation.

As shown in Fig. 9(a), a simplified model of porous media is used for modeling the pressure relief valve, aiming to simulate the dynamic pressure relief effect of the pressure relief valve. Meanwhile, in order to compare the differences between the two pressure relief valve models, a simulation model of the real pressure relief valve (with a fixed opening) is also established as shown in Fig. 9(b). The physical structure diagram of the real pressure relief valve is presented in Fig. 9(c).

Basic vehicle simulation analysis results

Vehicle interior pressure cloud map analysis

A transient CFD simulation analysis is conducted on the basic vehicle model, with the Z = 0.44 m section selected for pressure cloud map analysis, This horizontal section can clearly show the pressure distribution in the front and rear of the vehicle’s passenger compartment and the pressure distribution at the pressure relief valve, so as to study the mechanism of the transient pressure distribution inside the vehicle during the door closing process, as shown in Fig. 10.

During the door closure process, the airflow around the door begins to move with the door, leading to changes in the internal pressure of the cabin, as illustrated in Fig. 11. In the initial 0–0.5 s period, only a small amount of air is pushed into the cabin by the closing door, resulting in a relatively minor change in the internal pressure. During this period, the sensation of ear pressure within the cabin remains negligible. However, at t = 0.75 s, as the door continues to close, the pressure differential between the vehicle interior and exterior steadily increases. At t = 0.86s, the door fully closes, causing a significant pressure difference between the interior and exterior of the vehicle. At this moment, a large volume of air is compressed into the cabin, resulting in a sharp increase in cabin pressure and discomfort to the human ear. At t = 0.875s, the airflow compressed in the cabin moves toward the rear of the vehicle, leading to a noticeable pressure rise at the rear. By t = 0.9s, as the compressed air begins to escape through the pressure relief valve, the cabin pressure rapidly decreases. By approximately t = 1 s, the cabin pressure equalizes with the ambient pressure. The pressure contour variations during the door-closing process (Fig. 11-c) indicate a sharp increase in cabin pressure at the moment of door closure, which adversely affects ear comfort for occupants. Furthermore, the installation of a sound insulation cover on the pressure relief valve will lead to an insufficient effective leakage area of the pressure relief valve. The airflow passage within the passenger compartment forms a bottleneck at the sound insulation cover, causing the gas in the passenger compartment to fail to be expelled from the vehicle rapidly and smoothly. The rise in the rear pressure is influenced by the hindrance of the airflow by the acoustic insulation cover, suggesting that the sound insulation cover plays a crucial role in the dynamic changes of ear pressure.

Vehicle cabin pressure curve analysis

Considering that pressure variations in the occupant’s ear directly affect ride comfort, the pressure changes at the occupant’s ear have become a primary focus of research in engineering practice. Therefore, this study emphasizes the peak pressure at the occupant’s ear location. As shown in Fig. 12, the ear pressure curves at different time and their corresponding local enlarged images are presented.

As shown in Fig. 12, the peak pressure curve reveals that the ear pressure of passengers attains its maximum when the vehicle door is closed. It can be seen from Fig. 11 that at the instant the door is closed, the air inside the vehicle is squeezed from the driver’s side to the rear. At this time, the pressure inside the vehicle gradually increases from the front to the rear. Combined with the ear pressure curve in Fig. 12, it can be seen that during the entire door closing process, the peak ear pressure of the passengers inside the vehicle gradually increases from the front to the rear. At t = 0.861s, the left ear pressure of the passenger on the driver’s side reached its peak in advance. At t = 0.868s, the right ear pressure of the passenger on the driver’s side and the left and right ear pressures of the passenger on the front passenger side all reached their peak values. Furthermore, the peak ear pressure of the passenger on the front passenger side exceeded that of the passenger on the driver’s side by approximately 10 Pa, indicating that the airflow was displaced from the driver’s side to the front passenger side, resulting in an increase in pressure on the front passenger side. At t = 0.871s, the left and right ear pressures of the passengers in the second row on both the driver’s side and the front passenger side reached their peak values. Among them, the peak ear pressure of the passenger on the front passenger side in the second row was 1.1 to 2.3 Pa higher than that of the passenger on the driver’s side, indicating that the difference in pressure increase caused by the air flow movement between the left and right seats in the second row was narrowing. At t = 0.873s, the ear pressures of all passengers in the third row reached their peak values. At this time, the difference in peak ear pressure between the passenger on the front passenger side and the passenger on the driver’s side in the third row was negligible, merely 0.1 Pa. The passenger sitting on the right seat in the third row had the highest peak ear pressure of 248.1 Pa. The left and right ear pressures of the passenger on the driver’s side and the left ear pressure of the passenger on the front passenger side in the third row were all 248 Pa. This shows that the difference in the peak ear pressure between the passenger on the driver’s side and the passenger on the front passenger side is further reducing from the front to the rear. Additionally, when the airflow is compressed and reaches the third row, the pressure increase caused by the airflow movement on the left and right seats is essentially consistent, which is in accordance with the pressure distribution diagram at the rear shown in Fig. 11. The maximum peak ear pressure of passengers inside the vehicle is 248.1 Pa, which is borne by the right ear of the passenger sitting on the right seat in the third row. This exceeds the peak ear pressure index requirement of the cabin and requires optimization of the vehicle’s pressure relief path.

Simulation results of the optimized vehicle

To optimize the pressure relief pathways, the sound insulation cover of the pressure relief valve was removed, as illustrated in Fig. 13. A transient CFD simulation was then conducted to evaluate the performance of the optimized design.

After extracting the ear pressure peaks at different locations for both the baseline and optimized schemes, the results are shown in Figs. 14 and 15. Upon removal of the sound insulation cover, a significant reduction in ear pressure peaks was observed at all locations. Notably, the maximum ear pressure experienced by the right ear of the third-row passenger decreased to approximately 200 Pa, representing a 20% reduction compared to the baseline and meeting the design requirements.

Figure 16 illustrates the velocity distribution in the YZ cross-section for both the baseline and optimized schemes. The airflow from the interior grilles and perforated panels is initially obstructed by the sound insulation cover and is discharged only after passing through the small cavity between the cover and the pressure relief valve. This significantly hampers the efficiency of airflow discharge. Removing the sound insulation cover may exacerbate road noise, tire noise, and exhaust noise issues. These problems can be mitigated by incorporating alternative solutions, such as adding foam materials, to optimize road noise.

Experimental testing and comparison with simulation

Comparison of ear pressure results between simulation and experiment

Door-closing ear pressure tests were carried out on the baseline vehicle and the optimization plan, as shown in Fig. 17. A door speed sensor was arranged at the driver’s door, and pressure sensors were placed at the ear positions inside the vehicle to test the pressure variations at the ear positions of the occupants during the process from the door being open to closed. The model of the ear - pressure testing equipment is EZSlam 9451 FZMetrology (Michigan, USA). Prior to the commencement of the ear-pressure experiment, it is essential to calibrate the accuracy of the pressure sensor. The accuracy calibration of the pressure sensor is performed using the equipment depicted in Fig. 17(e) (including metrological devices: digital pressure gauge 5700773, a sealed container, and a pressure sensor). The accuracy-calibration method is as follows: Under normal-temperature conditions, place the ear-pressure sensor device and the digital pressure gauge inside the sealed container. Then, apply pressures of 100 Pa, 200 Pa, 300 Pa, and 400 Pa successively. Record the readings for each pressure value. In the event of any deviation between the readings of the two devices, calibrate the ear-pressure sensor according to the accurate values of the digital pressure gauge.

As shown inFig. 18, pressure sensors were placed at the outer and inner ears of all passengers inside the vehicle, totaling 12 measurement positions. The ear pressure change data during the door closing process was collected, and the peak ear pressure data at the 12 positions of the passengers inside the vehicle was tested and obtained. In this experimental research, the objective is to measure the ear-pressure test results corresponding to a representative door-closing speed of 1.2 m/s. Regarding the measurement repeatability, the experiment was carried out at least three times, and the standard deviation was approximately 2.6 Pa.

The ear pressure tests at various positions (a) third row, right seat, right ear (3RR); (b) third row, right seat, left ear (3RL); (c) third row, left seat, right ear (3LR); (d) third row, left seat, left ear (3LL); (e) second row, right seat, right ear (2RR); (f) second row, right seat, left ear (2RL); (g) second row, left seat, right ear (2LR); (h) second row, left seat, left ear (2LL); (i) co-pilot seat, right ear (1RR); (j) co-pilot seat, left ear (1RL); (k) driver seat, right ear (1LR) and (l) driver seat, left ear (1LL).

Figure 19presents the interior structure at the tail pressure relief valve of the baseline vehicle and the structure at the exterior side of the pressure relief valve. The optimization plan for the interior ear pressure is to remove the sound insulation cover at the pressure relief valve, as depicted in Figure 19(b).

Through the acquisition of the test data on the changes in passengers’ ear pressure during the door closing process, the peak data of each ear pressure was collected and statistically analyzed. As depicted in Fig. 20, it presents the comparison between the simulation results and the experimental results of the peak ear pressure of passengers for the base sample vehicle and the optimized scheme, the horizontal coordinate axis in the Fig. 20 is the simplified notation for the positions within the vehicle. For example, 1LL represents the left ear of the left seat in the first row inside the vehicle, 1LR represents the right ear of the left seat in the first row, and 2RR represents the right ear of the right seat in the second row. Through simulation analysis, at the instant the door is closed, due to the compression of the driver’s cabin door, the air inside the vehicle is squeezed from the driver’s cabin to the rear. At this point, the internal pressure within the vehicle gradually increases from the front row to the rear row. Hence, in the simulation analysis, the peak ear pressure of passengers gradually rises from the front row to the rear row. The test results in Fig. 20 also demonstrate that the peak ear pressure of passengers gradually increases from the front to the rear of the passenger compartment. The simulation trend is in accordance with the test results.

By comparing the peak ear pressure data at 12 positions obtained from passengers by simulation and experiments, it can be seen that the peak ear pressure of both the simulated and experimental vehicles inside the cabin occurs at the right ear of the right seat in the third row. Among them, the measured peak ear pressure at the right seat in the third row of the base vehicle is 245.2 Pa, and that of the optimized scheme vehicle at the same position is 196.4 Pa. The errors between simulation and experimental results were as follows: The error of the basic scheme for the right ear of the right seat in the third row is 1.2%, and that of the optimized scheme is 1.4%. The maximum ear pressure simulation and experimental errors at the in-car human ear position are all within 5%, which indicates that the simulation accuracy at the maximum ear pressure position is relatively high. The peak ear pressures at other human ear positions were calculated and compared, and the simulation and experimental errors were within 8%, with the simulation accuracy reaching over 92%. Through the comparison between simulation and experiment, the results of the baseline prototype vehicle and the optimized solution are presented as follows: For the baseline prototype vehicle, the maximum deviation is 15.3 Pa, and the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) is 9.5 Pa. In the case of the optimized solution, the maximum deviation is 14.6 Pa, and the RMSE is 10.1 Pa. In this study, for the vehicle model under investigation, the target value of the peak ear pressure during door closing is set at 210 Pa. After optimization, the peak ear pressure measured from the prototype vehicle test is 196.4 Pa, thereby fulfilling the design objective.

Comparison of ear pressure peak values from different pressure relief valve simulation model and experiment data

As shown inFig. 21, the computational results for different pressure relief valve simulation models are presented. From the post-processing velocity contour, it can be observed that when the real structure of the pressure relief valve (with a fixed blade opening) has a larger opening angle, the airflow passing through the valve increases, and the pressure relief effect becomes more pronounced. However, compared to the actual experimental data, the ear pressure peak inside the passenger cabin is lower.

The porous media model effectively approximates the fluid filtration and regulation characteristics of components like the vehicle pressure relief valve. As shown in Fig. 22, simulations using different pressure relief valve models were conducted to calculate the ear pressure peak values for the third-row right seat passenger, which were then compared with experimental data. The results indicate that the porous media simplified model, which accounts for the dynamic pressure relief air resistance characteristics, produces predictions that are very close to the real structure test results. This suggests that the simplified model is more accurate. In contrast, the real structure of the pressure relief valve (with a fixed opening) requires a more refined mesh, significantly increasing the computational resources needed. Given that the actual operating condition of the pressure relief valve involves blades maintaining varying dynamic openings, utilizing the porous media model and incorporating parameters calibrated from valve unit tests enables more precise calculations, thereby enhancing the model’s effectiveness.

Conclusion

This study takes a specific SUV model as a case study and combines three-dimensional CFD numerical simulations with experimental testing. The following key conclusions are drawn:

(1) Optimization by removing the sound insulation cover:

The removal of the sound insulation cover Surrounding the pressure relief valve results in an increase in airflow velocity at the valve, enhancing discharge efficiency and significantly reducing the peak ear pressure within the cabin. Specifically, the peak ear pressure at the right-hand seat in the third row decreased from 245.2 Pa to 196.4 Pa, representing a 20% reduction, leading to an improvement in ear comfort. However, this modification may contribute to an increase in road noise, tire noise, and exhaust noise. These undesirable effects can be mitigated by employing alternative solutions, such as incorporating foam materials.

(2) Simplified porous media model for the pressure relief valve:

The application of a simplified porous media model for the pressure relief valve effectively replicates the dynamic airflow resistance characteristics during the door-closing process. By incorporating experimental parameters to refine the valve’s dynamic airflow resistance, the precision and efficiency of flow field simulations during door closure are significantly enhanced.

(3) Impact of blade opening angle in the pressure relief valve simulation:

In the realistic simulation model of the pressure relief valve (with a fixed blade opening), a larger blade opening results in an underestimation of the cabin ear pressure peak, whereas a smaller blade opening leads to an overestimation of the ear pressure peak.

(4) Impact of Interior Pressure during the Door-Closing Process:

At the instant the vehicle door is closed and due to the compression by the door of the driver’s cab, the air inside the vehicle is displaced from the driver’s compartment to the rear. At this point, the pressure inside the vehicle gradually increases from the front row to the rear row, and the trend of the ear pressure simulation analysis is consistent with the test results.

(5) Accuracy of transient CFD simulations:

The discrepancy between the transient CFD simulation results and experimental data is within 8%. This indicates that the simulation method accurately captures the changes in ear pressure during door closing, demonstrating the validity and reliability of the approach.

(6) Generalizability:

The newly developed porous media model effectively characterizes the dynamic airflow resistance of pressure relief valve vanes during door closure and is applicable to various vehicle types, such as sedans, hatchbacks, and trucks. During early product development, performance tests on individual valves provide experimental parameters for calibrating the model, enabling accurate simulation of airflow resistance. Since valve selection differs across models, specific test data are necessary to update and optimize the porous media parameters accordingly. This approach ensures reliable and precise simulations, supporting design optimization across different body styles. Although internal grille flow channels and sealing designs vary significantly among vehicles and require tailored modeling of key flow regions, the turbulence model and dynamic mesh methodology remain consistent for all body types.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Ding, F., Xie, W. & Xie, X. Research on optimization of car door closing sound quality based on the integration of structural simulation and test. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part. D: J. Automobile Eng. 237 (6), 1378–1390 (2023).

Garro, G. T., Warwick, B. T. & Mechefske, C. K. Analysis of an automobile door closure vibroacoustic response. J. Vib. Control. 27 (5–6), 597–611 (2021).

Wang, X., Song, Y., Su, L., Wang, Y. & Pan, Z. Recognition of abnormal car door noise based on multi-scale feature fusion. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part. D: J. Automobile Eng. 237 (6), 1353–1364 (2023).

Liu, Z., Gao, Y. & Yang, J. Numerical and experimental-based framework for vibro-acoustic coupling investigation on a vehicle door in the slamming event. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 158, 107759 (2021).

Chen, Z., Qiu, S., Xue, Z. & Li, L. Aerodynamic behavior during closing of sliding door based on fluid–solid coupled simulation. Physics Fluids, 36(2), 025129, (2024).

Zhang, Q., Su, C., Tsubokura, M., Hu, Z. & Wang, Y. Coupling analysis of transient aerodynamic and dynamic response of articulated heavy vehicles under crosswinds. Phys. Fluids, 34(1), 212013 (2022).

Gao, S., Shi, Y., Pan, G. & Quan, X. A study on the performance of the cavitating flow structure and load characteristics of the vehicle launched underwater. Phys. Fluids, 34(12), 125108 (2022).

Pan, D., Xu, X. & Liu, B. Numerical analysis on hydrodynamic performance and hydrofoil optimization for amphibious vehicles. Phys. Fluids, 35(8), 083330 (2023).

Dinh, C. T., Nguyen, T. M., Vu, T. D., Park, S. G. & Nguyen, Q. H. Numerical investigation of truncated-root rib on heat transfer performance of internal cooling turbine blades. Phys. Fluids, 33(7), 076104 (2021).

Schuetz, T. C. Aerodynamics of Road Vehicles (Sae International, 2015).

Gaylard, A. P. The Appropriate Use of CFD in the Automotive Design Process (No. 2009-01-1162) (SAE Technical Paper, 2009).

Samples, M., Gaylard, A. P. & Windsor, S. The aerodynamics development of the range rover evoque. In 8th MIRA International Conference on Vehicle Aerodynamics (Vol. 1, pp. 13–14). (2010), October.

Howell, J. & Gaylard, A. Improving SUV aerodynamics. In 6th MIRA international vehicle aerodynamics conference (Vol. 1, pp. 1–17). (2006), October.

Gaylard, A. Discovery 4 SDV6 GS (The Official Centre for Jaguar Land Rover, 2017).

Chaligné, S., Turner, R. & Gaylard, A. The aerodynamics development of the new land rover discovery. In FKFS Conference (pp. 145–159). Cham: Springer International Publishing. (2017), September.

Lee, Y. L. & Hwang, S. H. Flow characteristics in a cabin during door closure. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering, 225(3), 318–327. (2011).

Zhang, R. Research on Human Ear Preesure Comfort during Door Closure of Passenger Car (Jilin University, 2014).

Li, S., Chen, C., Hu, X. & Cao, J. Numerical simulation research on pressure during door closure of commercial vehicle. SAE Int. J. Commer. Veh. 10 (2017-01-9182), 453–459 (2017).

Su, L. et al. Study on empirical model and CFD about pressure rising in cab during door closure. Vibroeng. Procedia. 46, 73–79 (2022).

Su, L. et al. Research on simulation model of high precision ear pressure comfort of car door closing based on user experience. In Third International Conference on Mechanical Design and Simulation (MDS 2023) (Vol. 12639, pp. 687–692). SPIE. (2023), June.

Unadkat, S. B., Pandurangan, V. & Selvan, V. Optimization of air extraction path for superior customer comfort while door closing event of a sports utility vehicle (SUV). SAE Technical Paper 2023-01-0601, (2023).

Ren, L. et al. Numerical analysis of the influence of air flow channel on ear pressure during door closure. Vibroeng. Procedia. 55, 150–155 (2024).

Siavoshani, S. J. & Vesikar, P. Door closing sound quality methodology-airborne and structural path contributions. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars-Mechanical Syst. 8 (2015-01-2263), 938–947 (2015).

Yang, J., Zhang, D., Tang, J. & Hu, H. CFD-based Simulation and Optimization of Vehicle Door Closure Ear Pressure Proceedings of the 2024 China Society of Automotive Engineers Aerodynamics Division Annual Conference. (2024).

Al-Saadi, A., Hassanpour, A. & Mahmud, T. Simulations of aerodynamic behaviour of a super utility vehicle using computational fluid dynamics. Adv. Automob Eng. 5 (134), 1–5 (2016).

Al-Saadi, A., Hassanpour, A., Motlagh, Y. G. & Mahmud, T. Simulation of aerodynamic behaviour of a road vehicle in turbulent flow. In Proceedings of the 25th UKACM Conference on Computational Mechanics (Vol. 12, pp. 151–154). (2017), April.

Guo, L., Zhang, Y. & Shen, W. J. Simulation analysis of aerodynamics characteristics of different Two-Dimensional automobile shapes. J. Comput. 6 (5), 999–1005 (2011).

Sterken, L., Sebben, S. & Löfdahl, L. Numerical implementation of detached-eddy simulation on a passenger vehicle and some experimental correlation. J. Fluids Eng. 138 (9), 091105 (2016).

Sirenko, V., Pavlovs’ ky, R. & Rohatgi, U. S. July) methods of reducing vehicle aerodynamic drag. Asme Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting Collocated with the Asme Heat Transfer Summer Conference & the Asme International Conference on Nanochannels. American Society of Mechanical Engineers.. (2012).

Brown, Y. I., Windsor, S. & Gaylard, A. P. The effect of base bleed and Rear cavities on the drag of an SUV. SAE Technical Paper 2010-01-0512, (2010).

Pitman, J. & Gaylard, A. An experimental investigation into the flow mechanisms around an SUV in open and closed cooling air conditions. In FKFS Conference (pp. 61–79). Cham: Springer International Publishing. (2017), September.

Altinisik, A., Kutukceken, E. & Umur, H. Experimental and numerical aerodynamic analysis of a passenger car: influence of the blockage ratio on drag coefficient. J. Fluids Eng. 137 (8), 081104 (2015).

Kang, S. O. et al. Actively translating a Rear diffuser device for the aerodynamic drag reduction of a passenger car. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 13, 583–592 (2012).

Wood, A., Passmore, M., Forbes, D., Wood, D. & Gaylard, A. Base pressure and flow-field measurements on a generic SUV model. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars-Mechanical Syst. 8 (2015-01-1546), 233–241 (2015).

Tsai, C. H., Fu, L. M., Tai, C. H., Huang, Y. L. & Leong, J. C. Computational aero-acoustic analysis of a passenger car with a Rear spoiler. Appl. Math. Model. 33 (9), 3661–3673 (2009).

Wang, F. J. The computational fluid dynamics analysis-Principles and Applications of CFD Software [M]. (2004).

Su, R., Li, H., Su, L., Xu, Z. & Chen, Y. Study on the simulation analysis method of ear pressure during vehicle door closure for a certain model. Automot. Technol. 11, 33–37 (2020).

HU, X. J. & LI T.F, WANG, J. Y. Numerical simulation of influence of rear-end panels on flow field in wake of a heavy duty truck. J. Jilin. Univ., Vol.42. (2012).

Katsoulos, C. L. An experimental study on drag reduction of aftermarket additions on an SUV. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/372, (2017).

Gaylard, A. P. Simulation of A-pillar/side glass flows for bluff SUV geometries. In Fifth MIRA International Conference On Vehicle Aerodynamics (pp. 13–14). (2004), October.

Ariff, M., Salim, S. M. & Cheah, S. C. Wall y + approach for dealing with turbulent flow over a surface mounted cube: part 1—low Reynolds number. In Seventh international conference on CFD in the minerals and process industries (pp. 1–6). CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia. (2009), December.

Al-Saadi, A. A. S. Analysis of Novel Techniques of Drag Reduction and Stability Increase for Sport Utility Vehicles using Computational Fluid Dynamics (Doctoral dissertation, University of Leeds). (2019).

Krishna, R. & Gupta, P. K. Optimizing pressure drop in 90° bend horizontal pipelines for dense slurry flow: A response surface methodology approach. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part E: Journal of Process Mechanical Engineering, Article 09544089241271765. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089241271765

Gupta, P. K., Kumar, N. & Krishna, R. Near-wall flow characteristics in pipe Bend dense slurries: optimizing the maximum sliding frictional power. Int. J. Sedim. Res. 39 (3), 435–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsrc.2024.04.002 (2024).

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 5247121335), the Hunan Provincial Department of Education Youth Project (Grant number 22B0742) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 5227120232).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhong Yang: Conceptualization (lead); Data curation (lead); Methodology (lead); Software (equal); Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (lead).Luoxing Li: Conceptualization (supporting); Funding acquisition (lead); Project administration (lead); Resources (lead); Writing-original draft (supporting).Lin Li: Data curation (supporting); Validation (supporting); Writing-original draft (supporting).Ziming Niu: Data curation (supporting); Writing-original draft (supporting). Zhengqing Liu: Data curation (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Software (equal); Writing-original draft (supporting).Shaobo Yang: Conceptualization (supporting); Funding acquisition (support); Project administration (support); Resources (lead).Shuiping Liao: Data curation (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Software (support).Yang Wen: Data curation (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Software (support).Zhenhu Wang: Data curation (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Software (support).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Li, L., Li, L. et al. CFD-Based optimization of dynamic pressure relief and associated simulation methodology for vehicle door closure. Sci Rep 15, 35997 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19758-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19758-1