Abstract

The pathogenicity of Klebsiella pneumoniae is continuously on the rise owing to variations in virulence. The polyketide synthase (pks) gene plays a crucial role in the expression of microbial virulence genes. However, Klebsiella pneumoniae, often considered a colonizing bacterium, has been shown to possess significant virulence and antibiotic resistance properties, which might be a significant factor contributing to the persistent difficulty in curing clinical gastrointestinal infections. This study analyzed the pks gene expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae and the associated clinical features in digestive infections over the past year. Gene editing technology and genomic analysis were employed to identify the virulence genes of Klebsiella pneumoniae in digestive tract infections. Experimental results demonstrated that a higher proportion of pks-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae were detected in the digestive tracts of clinical patients, and these strains carried more virulence factors. The clbA gene fragment can be utilized independently as a detection fragment for the pks gene. The pks gene may influence the virulence expression of Klebsiella pneumoniae through different signal pathways associated with other virulent genes. Testing for the pks gene can offer experimental evidence to support clinical treatment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intestinal infectious diseases are a common clinical issue intricately linked to the complex ecosystem of the intestinal microbiota1. Klebsiella pneumoniae, a bacterium that is widely distributed in the human gut microbiome, has been identified as the second most abundant component of the gut microbiota according to metagenomic studies2. The gut microbiota, which consists of a vast array of bacteria, including beneficial and potentially pathogenic strains, plays a crucial role in human health, influencing digestion, immune function, and overall well-being. Klebsiella pneumoniae is commonly found as a commensal bacterium in the intestinal tract of healthy individuals, but it can also act as a conditionally pathogenic bacterium, particularly when the immune system is weakened or the microbial balance is disrupted. However, recent research has revealed that Klebsiella pneumoniae is significantly enriched in the gut of patients with inflammatory bowel disease3. Klebsiella pneumoniae also maintained a stable and high proportion in the gut microbiota in ulcerative colitis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae Kp-2H7 (Kp2) has been found to positively correlate with the severity of intestinal inflammation, as evidenced by studies linking this bacterium to inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD)4.

The colonization of Klebsiella pneumoniae in the intestines can lead to the migration of microbial communities across the intestinal barrier, potentially causing diseases such as liver abscess and cirrhosis. Studies have shown that the use of antibiotics like ampicillin and amoxicillin can alter the intestinal flora balance, promoting the overgrowth of Klebsiella pneumoniae and increasing the risk of liver abscess5. Moreover, Klebsiella pneumoniae has been linked to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, where the presence of this bacterium in the gut is associated with a significant proportion of cases2. Recent research has identified a significant increase in the presence of Klebsiella pneumoniae within the gut microbiota of individuals diagnosed with liver cancer6. And Klebsiella pneumoniae notably accelerated the progression of inflammation in a mouse model6. However, the mechanisms underlying the interaction between Klebsiella pneumoniae and the host remain unclear. Klebsiella pneumoniae and intestinal diseases remain poorly understood. Besides, in routine microbiological diagnostics for acute infectious gastroenteritis, pathogen detection prioritizes Salmonella and Shigella species as primary targets7. As a consequence, targeted interventions for Klebsiella pneumoniae, which exhibits comparable pathogenicity, are frequently ignored in clinical practice.

The pks gene island encodes the genotoxin colibactin in Escherichia coli. Since colibactin is difficult to detect, researchers have also proposed using the expression of the pks gene to infer the expression of colibactin8. Colibactin secreted by pks-positive bacteria can damage intestinal epithelial cells, activate immune cells, trigger the release of inflammatory factors such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and induce intestinal mucosal inflammatory responses9. Recent studies have revealed a close association between the presence of pks genes and the generation of Klebsiella pneumoniae10. Additionally, significant phenotypic differences, such as in biofilm formation, have been observed in pks positive strains10,11. The pks gene can also help strains to colonize in the gut by secreting genotoxins and altering the microbiota composition12. Moreover, it can contribute to the development of invasive diseases through the action of these genotoxins13. However, the pathogenic status and virulence gene expression characteristics of the pks gene in intestinal Klebsiella pneumoniae remain unclear.

Klebsiella pneumoniae harbors virulence genes such as rmpA (capsule synthesis factor gene), iro (iron-regulated outer membrane protein cluster), iuc (aerobactin biosynthesis cluster), ureA (urease subunit A gene), and pks gene, among others. The rmpA gene product promotes capsule synthesis, leading to a hypermucoid phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Klebsiella pneumoniae strains harboring the rmpA gene frequently cause severe community-acquired infections in immunocompetent hosts, such as liver abscesses and pneumonia, and may be associated with multiorgan system co-infections or bacteremia14. The iro gene cluster encodes the synthesis of salmochelin, while the iuc gene cluster encodes aerobactin. Both are siderophore-related genes. Aerobactin and salmochelin show strong association with severe pneumonia and invasive diseases, such as liver abscesses and pneumonia, which are serious community-associated infections15. The ureA gene encodes a subunit of urease, an enzyme that hydrolyzes urea to produce ammonia, facilitating bacterial survival and dissemination within the host. This gene is commonly found in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates and may play a role in processes such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), promoting infection development16. The pks gene is also a virulence factor in Klebsiella pneumoniae, contributing to liver abscesses and severe bacteremia17, although its role in gastrointestinal infections remains less well understood.

In this study, we collected a total of 58 clinical samples of intestinal Klebsiella pneumoniae over the past year to investigate the impact of pks gene expression on virulence and antibiotic sensitivity. We further compared the relationship between pks gene, virulence genes, and strain virulence through data analysis, and validated the expression and virulence characteristics of the pks gene based on clinical information. This study aims to verify the significant role of pks genes in the detection and understanding of Klebsiella pneumoniae’s antibiotic resistance mechanisms. Klebsiella pneumoniae in the gut. This study could offer practical guidance for improving the accuracy of diagnosis and the effectiveness of treatment for infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Results

Analysis of Pks gene expression and clinical information of Klebsiella pneumoniae

In this study, 58 isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae were collected from clinical cases at the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University between June 2024 and February 2025. A total of 45 cases (77.59%) of fecal specimens, 6 cases (10.34%) of anal swab specimens, and 7 cases (12.07%) of bile specimens were obtained. The isolated strains were verified as target wild-type strains using MALDI-TOF MS and other techniques. Among these isolates, 27 strains (46.55%) were isolated from samples of patients with gastrointestinal infection symptoms, while 31 strains (53.45%) were isolated from patients presenting with other clinical symptoms. There were 33 male patients (56.90%) and 25 female patients (43.10%) involved in the study. Patients aged 60 to 80 years old had a relatively higher proportion compared to other age groups, accounting for 35% of the total. Moreover, the average age of samples from pks-positive strains was 52 years, whereas the average age of samples from pks-negative strains was 37 years. In patients exhibiting gastrointestinal infection symptoms, the incidence included 11 cases of enteritis (40.74%), 4 cases of Crohn’s disease (14.81%), and 2 cases of cholecystitis (7.41%). What’s more, 14 cases in this study showed distinct gastrointestinal imaging changes and were definitively diagnosed. Seven patients had normal imaging findings. However, six of these patients harbored Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates carrying the pks gene and other virulence factors. Notably, 5 of these patients were under 10 years old. Additionally, 7 patients (all under 10 years old) presented with clinical gastrointestinal symptoms. The study found that 65.51% of the strains (38 out of 58) expressed the pks gene (clbA+clbB+clbN+), while 34.48% (20 out of 58) did not show any expression of the pks gene. The expression of the pks gene in the isolated strains, along with the specific clinical details of the cases from which they were sourced, are presented in detail in Tables 3 and 4. A significant correlation was found between the clbA + strain and pks gene expression (clbA+clbB+clbN+), with a significance level of p < 0.01. The expression of pks gene in the isolated strains and the specific clinical information of the source cases are detailed in Tables 1 and 2, which are integral to understanding the clinical distribution and antibiotic resistance patterns of Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Analysis of bacterial resistance

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) highlights the significant impact of carbapenemase-resistant strains on clinical diagnosis, treatment efficacy, and patient outcomes. The detection of carbapenemase production can serve as a standalone diagnostic tool to inform clinical treatment decisions and infection control strategies, independent of traditional antimicrobial susceptibility testing, as evidenced by comprehensive guidelines and clinical practices18. The Vitek 2 compact system was utilized to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of bacterial strains against carbapenem antibiotics. A total of 58 microbial samples were collected based on patients’ symptoms; however, only 13 patients attracted clinical attention, with relatively complete clinical information and corresponding antimicrobial susceptibility results. Therefore, analyses were conducted on these 13 patients with complete clinical information. Sensitivity tests for carbapenem antibiotics were performed on all isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Among them, two CRE strains were identified (2 out of 13, accounting for 15.38%), and both of these strains were positive for the expression of the pks gene. Despite the increasing prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections, the remaining strains in this study exhibited sensitivity to carbapenem antibiotics. The detailed results are presented in Table 3.

The proteomics and bioinformatics analysis of pks gene and related proteins

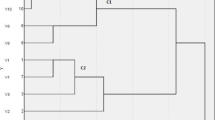

Through proteomic analysis, significant differences in capsule-related proteins in Klebsiella pneumoniae were discovered, as shown in Fig. 1. The experiment demonstrated that in proteomic analysis, 46 differentially expressed capsular proteins were significantly enriched in pks-positive strains compared to pks-negative strains. The high expression of the capsule-related gene rmpA, as indicated by recent studies on hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKp), supports the notion that the pks gene can enhance bacterial virulence at the protein level by influencing the expression of capsule-related genes.

Combined with PCR experiment results (Results 4), significant changes were found in iron-carrier related genes such as entC.

Our analysis demonstrated that pks-positive strains exhibited differential expression of siderophore-related proteins compared to pks-negative strains, including Iron Binding Protein SufA, Iron-Sulfur Cluster Scaffold Protein IscU (Table 4).

Expression of pks genes and virulence genes

Studies have demonstrated that specific gene fragments, including entC, rmpA, ybtA, and fruA, are highly virulent in Klebsiella pneumoniae. These gene fragments are instrumental in distinguishing between hypervirulent and classical strains of the bacterium. Statistical analysis revealed a significant correlation between the expression of pks-positive gene strains and the virulence genes (entC, rmpA, ybtA, fruA), with strong statistical significance, p < 0.05. The differences in virulence gene expression between strains with positive pks gene expression (clbA+clbB+clbN+) and strains with weak pks gene expression (incomplete or non-expressing pks gene) are presented in Table 5.

Expression of iron carriers

Iron carrier production capacity of Klebsiella pneumoniae was acquired by monitoring the iron carrier content through ultraviolet spectrophotometry.

Among the strains with high pks gene expression, 40% (6/15) strains exhibited high expression of iron carriers. The Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with overexpressed pks genes demonstrated a stronger ability to express iron carriers compared to the strains with low pks gene expression, p < 0.05, as shown in Table 6.

Discussion

The gastrointestinal microbiota is fundamental to maintaining the stability of the digestive system. However, recent research has firmly established a strong association between the gut microbiota and diseases like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Specifically, changes in gut microbiota, particularly in virulence genes, have been shown to correlate positively with the active phase of intestinal inflammation20,21. However, the relationship between the virulence gene carriage levels in the gut microbiota and disease progression remains incompletely understood, and the mechanisms by which hypervirulent strains reshape the gut microbiota’s colonization patterns and functional regulatory networks are yet to be fully elucidated.

This study has revealed that Klebsiella pneumoniae harboring the pks gene hold significant clinical value in the context of gastrointestinal diseases. Previous investigations about Klebsiella pneumoniae have demonstrated that the pks gene plays a pivotal role in modulating bacterial virulence and pathogenicity7, attracting increasing attention from the scientific community. Epidemiological research in Taiwan showed that pks-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae strains were associated with a higher disease incidence22. Furthermore, research has indicated that pks-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae strains are significantly more likely to cause liver abscesses and bloodstream infections compared to pks-negative counterparts23. In the present study, Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from clinical cases were collected, and it was found that pks-positive strains accounted for 65.51% of the total. Combined with antimicrobial resistance analysis results, pks-positive and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains are more prevalent in elderly patients (> 70 years old) and exhibit strong occult characteristics. Given their high drug resistance and virulence traits, clinicians must remain vigilant against missed diagnoses caused by underlying diseases masking the infection. Among the cases yielding pks-positive isolates, 39.47% of patients were diagnosed with infectious gastrointestinal diseases such as enteritis. Our research has firmly established that the pks gene assumes a pivotal role in Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in the gastrointestinal tract. It is intricately and directly linked to the pathogenicity of Klebsiella pneumoniae, a relationship that cannot be explained by the dysbiosis of the gut microbiota. Consequently, it is of utmost importance to approach the diagnosis and treatment of pks-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in the gastrointestinal tract with due diligence.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is generally regarded as a normal commensal bacterium in the intestinal tract within the context of gastrointestinal microbiota research. Clinically, Klebsiella pneumoniae in the digestive has not been fully recognized as a major pathogenic agent, and insufficient attention has been paid to its virulence potential. However, among 58 evaluated cases, 14 demonstrated distinct gastrointestinal imaging abnormalities, while 7 showed normal imaging. Notably, 6 of these 7 “imaging-negative” patients yielded Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates harboring pks pathogenicity island and other virulence genes (i.e., rmpA, entC), with 5/6 (83%) being pediatric cases (< 10 years old). Additionally, all 7 clinically symptomatic patients (all under 10 years old) presented with persistent gastrointestinal manifestations (e.g., diarrhea, abdominal pain), despite normal initial imaging.These findings highlight the potential of pks gene detection as a valuable tool for predicting the virulence of gastrointestinal strains.

Pks-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae strains exhibit a coordinated enhancement mechanism with other virulence genes(entC, rmpA, ybtA, fruA). The pks gene island comprises 19 genes, which encode a complex enzymatic machinery for the synthesis of colibactin23,24. In this study, clbA, clbB, and clbN fragments were selected to investigate the relationship between the pks gene and other virulence determinants in the gastrointestinal tract. The gene encoded by clbA represents the rate-limiting step in the biosynthetic pathway of the genotoxin colibactin7. ClbB is the most core non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) module in the pks genomic island, playing a critical role in functions such as peptide chain elongation and enzyme complex assembly25. ClbN serves as a key auxiliary module of NRPS, exerting effects in scaffold extension and modification25. Virulence genes such as entC, rmpA, ybtA, and fruA have been shown to augment bacterial virulence and pathogenicity. Our study demonstrated significant associations between the pks gene and these four virulence genes. EntC is part of the siderophore synthesis gene island, which is closely linked to bacterial virulence26. Clinical studies have also shown that high expression of siderophore genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with invasive diseases such as liver abscesses and bloodstream infections27. The pks gene domain collaborates with non -ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) modules to participate in siderophore production, demonstrating functional synergy with the ent gene island10. The rmpA gene activates the capsular polysaccharide synthesis gene cluster, promoting the secretion of capsular polysaccharides (e.g., K1 and K2 types)28. Studies have shown that deletion of capsule synthesis genes like rmpA reduces capsule thickness and serum resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae29. Additionally, pks+ strains have been reported to have significantly thicker capsules and a stronger association with K1 - type capsule production10. Our findings further support the cooperative role of pks and rmpA in enhancing bacterial virulence even in digestive infection. Yersiniabactin, which is encoded by the ybtA gene, enables bacteria to acquire iron from host iron-binding proteins, thereby facilitating their survival and colonization30. Studies using mouse infection models have shown that ybtA-deficient Klebsiella pneumoniae strains exhibit reduced colonization ability and lower bacterial counts in the lungs31. The observed correlation between pks and ybtA expression in our study suggests an interconnected virulence regulation mechanism involving iron uptake. The result in this study might indicate that the pks gene enhances the colonization of pathogenic Klebsiella pneumoniae by influencing the expression or function of ybtA. The fruA gene is essential for bacterial energy metabolism and pathogenicity32. fruA might also be associated with siderophore secretion and capsule formation33. The correlation between pks and fruA expression in our study implies a potential link to the pathogenicity of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Therefore, pks-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae strains exhibit a higher capacity for carrying virulence genes, making them valuable biomarkers for assessing bacterial pathogenicity. These strains are intricately linked to multiple virulence mechanisms, including siderophore secretion, capsule formation, Yersiniabactin synthesis.

Furthermore, clbA-positive strains showed a highly significant association (p < 0.001) with pks-positive strains (clbA + clbB + clbN+), compared to clbA-negative strains. The pks gene island, approximately 54 kb in length and containing 19 genes (clbA - clbS), has clbA located at its start. Deletion of clbA completely abolishes colibactin synthesis and eliminates the bacteria’s ability to induce host DNA damage34. clbA also contributes to siderophore production34 and is associated with reduced meningitis - related infectivity in mouse models when deleted35. Our analysis further showed that clbA-positive strains carried more virulence genes, with significant correlations observed between clbA-positive strains and the expression of entC, rmpA, ybtA, and fruA. Using the clbA gene fragment alone for strain virulence assessment may offer clinical advantages in terms of efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

The emergence of hypervirulent and drug - resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in the gastrointestinal tract is a cause for concern. In this study, two pks-positive strains resistant to carbapenem antibiotics were identified among 13 gastrointestinal isolates. Currently, in routine microbiological diagnosis for acute infectious gastroenteritis, prioritizing Salmonella and Shigella species as primary targets for pathogen detection7. Although previous studies have reported that pks-positive strains are more susceptible to antibiotics than pks-negative strains36,37, our findings deviate from this trend. Based on our experimental findings, hypervirulent and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains exist in gastrointestinal infections. In recent years, an increasing number of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates have concurrently exhibited both hypervirulence and carbapenem resistance, leading to severe clinical outcomes. Carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (CR-hvKP) emerged in the early 2010s and has since become increasingly prevalent38. It is necessary to be vigilant against the prevalence of corresponding highly drug-resistant and hypervirulent strains in gastrointestinal infections. The detection of pks virulence genes also has important implications for fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). FMT is used clinically to treat Clostridioides difficile infections by restoring normal gut microbiota colonization. However, concerns regarding microbiota safety and standardization persist. In this study, 61.53% of pks+ Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates were from cases without obvious gastrointestinal diseases. Given the immune-evasion mechanisms associated with pks-positive strains39, hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae may colonize the gut of healthy individuals without causing symptoms. This poses a risk of transmitting hypervirulent strains during FMT, potentially leading to complications. Therefore, screening donor microbiota for virulence genes, including pks gene, is crucial for enhancing the safety and efficacy of FMT.

In conclusion, Klebsiella pneumoniae present in the gastrointestinal tract harbors potential pathogenicity. The pks-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae strains exhibit a significant correlation with the age of clinically infected patients and antibiotic resistance profiles, particularly in hypervirulent isolates .Screening for the pks gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from the gastrointestinal tract can contribute to more accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment of gastrointestinal infections. Moreover, clbA can function as an effective and cost-efficient molecular marker for the screening of virulence genes in cases of gastrointestinal infections. Additionally, the functional role of the pks gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae infection demonstrates a positive association with siderophore expression.

Methods

Sample collection

Clinical infection specimens were inoculated onto blood agar medium and incubated overnight at 35 °C. This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University School [number 2022-81]. All methods were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent has been obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardians for the collection of clinical samples and relevant clinical information. All colonies of Klebsiella pneumoniae were screened and identified by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS). Klebsiella pneumoniae was isolated from a standard blood agar plate, and individual colonies were purified on the same plate.

The inclusion criteria for all patient specimens are based on the following criteria: ①There are obvious intestinal irritation symptoms, systemic reactions to infection, and special gastrointestinal infection symptoms such as nausea and vomiting.②Laboratory assisted diagnosis confirms the presence of infection symptoms.③Fecal pathogen detection can isolate significant growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Patients with other unrelated gastrointestinal symptoms will be included in the control group for comparison. There was data regarding the drug (carbapenems) resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae that could be used for retrospective analysis.

Detection of pks genes and virulence genes of Klebsiella pneumoniae in digestive infection

The RNA of Klebsiella pneumoniae was extracted from the strain by RNA extraction kit (Cell/Bacterial Total RNA EXtration Kit (RE716, Genesand Biotech Co., Ltd). The BioDrop UV spectrophotometer was utilized to ascertain the purity and concentration of the isolated RNA, employing the principles of spectrophotometry. Subsequently, The biological bacterial RNA reverse transcription kit was utilized for cDNA synthesis (E047, Novoprotein Scientific Inc.). The procedure was done according to the manufacturers’ protocol.

The pks gene was analyzed and screened according to their expression levels determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

The SYBR Green I intercalating fluorescence-based method was performed using NovoStart® Universal Fast SYBR qPCR SuperMix (E401, Novoprotein Scientific Inc.). Klebsiella pneumoniae strain 1084 and Klebsiella pneumoniae NTUH-K2044 were used as positive and negative controls for the pks gene, respectively. The 16s RNA gene served as the internal reference. Relative expression levels of target genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Each gene from each strain was analyzed in triplicate technical replicates, and melting curve analysis was conducted to verify amplicon specificity. Strains were categorized into high-expression and low-expression groups based on the pks gene expression levels. Meanwhile, conduct qPCR amplification experiments to detect the virulence genes of the strains. Specific primers were cited from the literature (refer to Table 1). The qPCR amplification system and PCR conditions are presented in Tables 7 and 8.

Antibacterial drug sensitivity test

The Vitek 2 compact was utilized to ascertain the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for carbapenems, specifically Imipenem and Meropenem, against bacterial strains.

The disk diffusion method was utilized to measure the diameter of the inhibition zone of the target strain against Imipenem and Meropenem, with Escherichia coli ATCC25922 serving as the quality control strain. The antimicrobial susceptibility test was reported according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) 2024 edition of the Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (M100 S30).

Construction of pks gene silencing strain Δpks and complementation strain C-Δpks

To investigate the specific mechanism underlying the differential expression of the pks gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae, we further constructed a pks gene silencing strain, designated as Δpks, and a complementation strain, named C-Δpks.

First, the target pks+ strain was cultured, and a bacterial suspension was prepared. The bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation and washed three times with 10% glycerol. Subsequently, the bacterial cells were resuspended in 2 mL of 10% glycerol to obtain the electrocompetent state of the prepared strain.

Next, 90 µL of the prepared competent cells were taken, and 10 µL of the plasmid was added. The mixture was left to stand on ice for 5 min. After electroporation at 2500 kV, 1 mL of LB medium was added, and the culture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Following the incubation, the culture was spread onto a tetracycline-resistant plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C to obtain the electroporated pTcCas9 plasmid.

The recombinant pTcCas9 plasmid was then electroporated into Cas9 competent cells. After homologous recombination and screening by PCR identification, the pks gene deletion strain Δpks was successfully obtained.

Finally, the complementary plasmid pTcCas9 containing the pks gene was transformed into the Δpks strain to construct the complementation strain C-Δpks. The constructed strain was preserved for use in subsequent experiments.

Proteomic testing experiments

Wild-type pks+ strain, the pks gene-deficient strain Δpks, and the complementation strain C-Δpks were set as the experimental groups, while the wild-type pks-strain was used as the control group. These strains were analysed by in-depth proteomic analysis. First, proteins were extracted from samples and subjected to enzymatic digestion. The digested peptides underwent TMT reagent labeling and enrichment separation before being analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry to generate mass spectrometry data. Protein identification was performed using MaxQuant (v2.1.4.0) software against the Klebsiella pneumoniae Uniprot database. Subsequently, functional annotation of identified proteins was performed using multiple functional databases (GO, Pathway, eggNOG, etc.) to reveal protein functional classifications. A comprehensive evaluation of all protein intensity data from sample identification and quantification was conducted, including protein intensity distribution, inter-sample relationships, reproducibility analysis, etc. Protein quantification was carried out using MaxQuant (v2.1.4.0). Finally, differentially expressed proteins between pairwise phenotypic groups were screened primarily via univariate analysis. Differentially expressed proteins were identified using a Fold Change (FC) threshold of > 1.5 and statistical significance determined by T-test (p-value < 0.05). Suitable visualization charts were generated using the data visualization software R (v4.5.1).

Determination of the relative content of iron carrier

First, transfer an appropriate 1 ml 3 × 108 CFU/mL bacterial solution into a centrifuge tube and centrifuge it at 10,000 revolutions per minute (r/min) for 10 min. Then, carefully pipette 100 µL of the supernatant and combine it with an equal volume of the Chrome Azurol S detection solution (CAS). After thorough mixing, place the mixture in the dark and let it stand for 30 min. Using double-distilled water as the blank control, measure the absorbance value (As) of the sample at a wavelength of 630 nm. Subsequently, prepare a control by mixing an equal volume of the blank culture medium with the CAS detection solution, and record its absorbance value as the reference value (Ar). Finally, calculate the relative content of the iron carrier using the following formula: [Ar(Ar − As)]×100%.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- PKS:

-

Polyketide synthases

- NRPS:

-

Non-ribosomal peptide synthetases

- MALDI-TOF/MS:

-

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

References

Lei, T. Y. et al. Hypervirulent and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: A global public health threat. Microbiol. Res. 288, 127839 (2024).

Yin, Q. et al. Ecological dynamics of Enterobacteriaceae in the human gut microbiome across global populations. Nat. Microbiol. 10(2), 541–553 (2025).

Zheng, J. et al. Noninvasive, microbiome-based diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Med. 30(12), 3555–3567 (2024).

Furuichi, M. et al. Commensal consortia decolonize Enterobacteriaceae via ecological control. Nature 633(8031), 878–886 (2024).

Choby, J. E. et al. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae - clinical and molecular perspectives. J. Intern. Med. 287(3), 283–300 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Gut–liver translocation of pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae promotes hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Nat. Microbiol. 10(1), 169–184 (2025).

Chagneau, C. V. et al. The Pks island: a bacterial Swiss army knife? Colibactin: beyond DNA damage and cancer. Trends Microbiol. 30(12), 1146–1159 (2022).

Smith, A. et al. Molecular detection guidelines for acute infectious gastroenteritis. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 92(2), 83–95 (2025).

Thakur, B. et al. Dietary fibre counters the oncogenic potential of colibactin-producing Escherichia coli in colorectal cancer. Nat. Microbiol. 10(4), 855–870 (2025).

Chenshuo, L. et al. Genetic and functional analysis of the pks gene in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. Microbiol. Spectr. 11(4), e0017423 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae induces inflammatory bowel disease through caspase-11-mediated IL18 in the gut epithelial cells. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15(3), 613–632 (2023).

Tronnet, S. et al. The genotoxin colibactin shapes gut microbiota in mice. mSphere 5(4), e00589–620 (2020).

Mccarthy, A. J. et al. The genotoxin colibactin is a determinant of virulence in Escherichia coli K1 experimental neonatal systemic infection. Infect. Immun. 83(9), 3704–3711 (2015).

Turton, J. F. et al. Virulence genes in isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from the UK during 2016, including among carbapenemase gene-positive hypervirulent K1-ST23 and ‘non-hypervirulent’ types ST147, ST15 and ST383. J. Med. Microbiol. 67(1), 118–128 (2018).

Lam, M. M. C. et al. Tracking key virulence loci encoding aerobactin and salmochelin siderophore synthesis in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Genome Med. 10(1), 77 (2018).

Ballaben, A. S. et al. Different virulence genetic context of multidrug-resistant CTX-M- and KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from cerebrospinal fluid. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 104(3), 115784 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Genomic and clinical characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae carrying the pks Island. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1189120 (2023).

CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 35th ed. CLSI supplement M100. (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2025).

Atarashi, K. et al. Ectopic colonization of oral bacteria in the intestine drives TH1 cell induction and inflammation. Science 358(6361), 359–365 (2017).

Zechner, E. L. & Kienesberger, S. Microbiota-derived small molecule genotoxins: host interactions and ecological impact in the gut ecosystem. Gut Microbes. 16(1), 2430423 (2024).

Sankarasubramanian, J. et al. Gut microbiota and metabolic specificity in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 7, 606298 (2020).

Chen, Y. T. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of pks genotoxin gene cluster-positive clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 7, 43120 (2017).

Shi, Q. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of Pks gene cluster harbouring Klebsiella pneumoniae from bloodstream infection in China. Epidemiol. Infect. 148, e69 (2020).

Nowrouzian, F. L. & Oswald, E. Escherichia coli strains with the capacity for long-term persistence in the bowel microbiota carry the potentially genotoxic pks island. Microb. Pathog. 53(3–4), 180–182 (2012).

Auvray, F. et al. Insights into the acquisition of the pks island and production of colibactin in the Escherichia coli population. Microb. Genom. 7(5), 000579 (2021 ).

Sheldon, J. R., Laakso, H. A. & Heinrichs, D. E. Iron acquisition strategies of bacterial pathogens. Microbiol. Spectr., 4(2) (2016).

Holden, V. I. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae siderophores induce inflammation, bacterial dissemination, and HIF-1α stabilization during pneumonia. mBio. 7(5) (2016).

Song, S. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae adaptive evolution of carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent in the urinary tract of a single patient. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121(35), e2400446121 (2024).

WalkerK, A. et al. A Klebsiella pneumoniae regulatory mutant has reduced capsule expression but retains hypermucoviscosity. mBio, 10(2) (2019).

Perry, R. D. & Fetherston, J. D. Yersiniabactin iron uptake: mechanisms and role in Yersinia pestis pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 13(10), 808–817 (2011).

Lawlor, M. S., Oconnor, C. & Miller, V. L. Yersiniabactin is a virulence factor for Klebsiella pneumoniae during pulmonary infection. Infect. Immun. 75(3), 1463–1472 (2007).

Zeng, L., Wen, Z. T. & Burne, A. A novel signal transduction system and feedback loop regulate fructan hydrolase gene expression in Streptococcus mutans. Mol. Microbiol. 62(1), 187–200 (2006).

Chakraborty, B., Zeng, L. & Burne, A. The FruB gene of Streptococcus mutans encodes an endo-levanase that enhances growth on levan and influences global gene expression. Microbiol. Spectr. 10(3), e0052222 (2022).

Martin, P. et al. Interplay between siderophores and colibactin genotoxin biosynthetic pathways in Escherichia coli. PLoS Pathog. 9(7), e1003437 (2013).

Meng, X. et al. Phosphopantetheinyl transferase ClbA contributes to the virulence of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli in meningitis infection of mice. PLoS One. 17(7), e0269102 (2022).

Tan, Y. et al. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae employs genomic Island encoded toxins against bacterial competitors in the gut. ISME J. 18(1), wrae054 (2024).

Elashry, A. H., Hendawy, S. R. & Mahmoud, N. M. Prevalence of Pks genotoxin among hospital-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae. AIMS Microbiol. 8(1), 73–82 (2022).

Lan, P. et al. A global perspective on the convergence of hypervirulence and carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 25, 26–34 (2021).

Cuevasramos, G. et al. Escherichia coli induces DNA damage in vivo and triggers genomic instability in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107(25), 11537–11542 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(grant:82172327), The National Natural Youth Science Foundation of China(grant:82402686).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L. and W.H. conceived and designed the experiments. W.H. and Y.S. performed the experiments. S.C. analyzed the data. Y.L. and B.Y. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. W.H. wrote the manuscript. W.H. and C.L. edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University School [number 2022-81]. All methods were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, C., Huang, W., Shi, Y. et al. High polyketide synthase gene expression boosts pathogenicity of Klebsiella pneumoniae in the digestive infection. Sci Rep 15, 35839 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19771-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19771-4