Abstract

In this paper, a theoretical analysis and comparative study of pH BioFET sensor designs using silicon/silicon dioxide (Si/SiO2), multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT), and MXene/High-k dielectric materials is conducted. Being able to measure pH accurately and quickly is crucial in various fields, like clinical diagnostics, environmental study, food quality control, and industrial process management. Traditional sensing methods often have limitations in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, portability, and continuous observing. The incorporation of advanced materials, specifically carbon nanotubes and Ti3C2Tx MXene, into biosensor designs leads to improved sensing capacities, primarily attributed to their elevated surface-to-volume ratios, heightened sensitivity, and inherent biocompatibility. The study details the structural aspects of each BioFET device and employs a mathematical model to analyze their performance. Simulation results demonstrate that the MXene/High-k device exhibits superior electrical properties, including higher drain current, and transduction sensitivity, making it highly promising for advanced pH sensing applications compared to conventional Si/SiO2 and MWCNT-based sensors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sensors capable of detecting pH are crucial for diverse applications, ranging from clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring to food quality control, and industrial process management. The ability to accurately and rapidly measure these parameters is paramount for effective disease management, ensuring public health, and maintaining ecological balance. Traditional sensing methods often face limitations concerning sensitivity, selectivity, portability, and real-time monitoring capabilities. This has driven extensive research into novel materials and fabrication techniques for developing advanced sensor platforms1,2. Wearable biosensors made from field effect transistors for pH monitoring is an emerging field. The FET based biosensors are known for their sensitivity, versatility, and selectivity and wide range of detection possibilities. The fabrication of FETs is well established process, and it is cost effective also3,4.

The incorporation of new materials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) in biosensors provides a foundation for highly sensitive and conductive environment for detecting various analytes in sweat with their remarkable characteristics such as high surface to volume ratios, good sensitivity, biocompatibility, energy efficiency, and relatively easier fabrication5.

To boost the sensing capabilities of bio-sensing devices, the paper proposes incorporation of Ti3C2Tx MXene as channel material for BioFET. These two-dimensional transition metal carbides significantly enhance the performance of FET-based sensors. When added to the channel material, Ti3C2Tx MXenes improve electronic properties, increase reactivity, and elevate sensitivity due to their high surface area. Furthermore, their biocompatibility and catalytic role accelerate sensor response. The findings demonstrate that composites featuring Ti3C2Tx MXenes notably improve the performance of wearable sensors6,7.

Non-enzymatic sensors have attracted significant attention owing to their low cost, high stability, rapid response, and excellent low limit of detection (LOD). However, their sensitivity and selectivity still lag enzymatic counterparts. While invasive monitoring remains the conventional practice, non-invasive sensing is increasingly regarded as a more promising strategy for continuous, real-time monitoring of blood analytes. Moreover, valuable diagnostic information can also be extracted from alternative body fluids such as sweat, saliva, tears, and interstitial fluid. Based on their underlying detection principles, biosensors are generally classified into three main categories: electrochemical, optical, and bio-electronic8. The details of the bio-electronic BioFET pH sensor used in this work are discussed in the following sections.

Traditional Si/SiO2 based sensors

Silicon and its native oxide, silicon dioxide, form the cornerstone of modern semiconductor technology. The well-established fabrication processes and excellent material properties make Si/SiO2 an attractive platform for developing highly integrated and miniaturized sensors9.

Ion-Sensitive Field-Effect Transistors (ISFETs) are a prominent example of Si/SiO2 based pH sensors. In an ISFET, the gate metal of a conventional MOSFET is replaced by a pH-sensitive dielectric layer that is exposed to the analyte solution. The surface potential at the dielectric/electrolyte interface changes with pH, modulating the channel current of the transistor10. The Si/SiO2 layer, being the native oxide of silicon, offers good biocompatibility and can be easily integrated into standard CMOS fabrication processes. Researchers have explored various modifications to the Si/SiO2 surface to improve sensitivity, stability, and selectivity. For instance, modifying the Si/SiO2 surface with different functional groups or doping it with specific ions can enhance its affinity for H + or OH− ions, leading to improved pH response. Despite the advantages of Si/SiO2 in terms of miniaturization and cost-effectiveness, challenges related to long-term stability, drift, and calibration still need to be addressed for widespread clinical applications11.

Multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) based sensors

Composed of multiple concentric graphene layers, Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) are cylindrical nanostructures. Their unique combination of exceptional electrical conductivity, high aspect ratio, large surface area, mechanical strength, and chemical stability makes them perfect for a wide range of sensing applications. The MWCNTs can be readily functionalized with various chemical groups or biological recognition elements, significantly improving their sensing performance12.

MWCNTs exhibit inherent sensitivity to pH changes due to the presence of surface defects and functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, hydroxyl) that can protonate or deprotonate in response to variations in H+ ion concentration. This change in protonation state alters the charge carrier concentration and, consequently, the electrical resistance or capacitance of the MWCNT network, forming the basis for pH sensing. MWCNT-based potentiometric and impedimetric pH sensors have been developed, offering advantages such as fast response times and good stability. Furthermore, MWCNTs can serve as excellent electrode materials for immobilizing pH-sensitive dyes or conducting polymers, leading to composite sensors with enhanced performance6,13,14,15.

MXene/high-k dielectric based sensors

MXenes are a new family of two-dimensional (2D) transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides, characterized by the general formula M{n+1}XnTx, where ‘M’ is an early transition metal, ‘X’ is carbon or nitrogen, and ‘Tx’ represents surface terminations (e.g., –OH, –O, –F). Their unique properties, including high metallic conductivity, large surface area, tunable surface chemistry, and hydrophilicity, make them exceptional candidates for electrochemical sensing. High-k dielectrics (materials with high dielectric constants) are often integrated with MXenes to form heterostructures that can further enhance sensor performance by improving gate control and reducing leakage currents16. The abundant surface termination groups on MXenes can interact with ions in solution, making them inherently sensitive to pH changes. The layered structure and excellent electrical conductivity of MXenes allow for efficient charge transfer, which is crucial for potentiometric or impedimetric pH sensing. Integrating MXenes with high-k dielectrics can lead to the development of highly stable and sensitive pH sensors by leveraging the superior gate coupling provided by the high-k material. While research on direct MXene/High-k pH sensors is emerging, the principles of MXene’s pH sensitivity, coupled with the enhanced dielectric properties of high-k materials, suggest a promising avenue for advanced pH sensing devices with improved signal-to-noise ratios and stability in complex biological environments17,18.

Other bio-electronic pH sensors

Among the various dielectric/channel materials reported for ISFET pH sensors, oxides such as SnO2, Ta2O5, and sol–gel TiO2 are widely recognized for their stability and near-Nernstian performance19,20,21. These remain the dominant choices in many biomedical and chemical sensing studies. Further, pH monitoring is not only important in chemical and environmental contexts but also plays a critical role in bio-medical diagnostics. For instance, maintaining blood pH within the narrow physiological range of 7.35–7.45 is essential for homeostasis, and even small deviations may indicate conditions such as acidosis or alkalosis. Similarly, saliva pH (typically 6.2–7.6) is increasingly recognized as a non-invasive marker for oral and systemic health, while interstitial fluid (ISF) provides valuable information for wearable biosensors in personalized healthcare. These biological matrices, however, present unique challenges compared to standard buffer solutions, including protein adsorption, biofouling, high ionic strength, and viscosity, all of which can interfere with accurate pH measurement. Therefore, sensor materials designed for biomedical applications must combine high sensitivity with stability, robustness against interference, and compatibility with complex fluids. In this context, MXene based high-k dielectric structures offer strong potential due to their large surface area, hydrophilic nature, and superior charge-transport properties, which may support reliable operation even under bio-relevant conditions.

In the present work, however, our comparisons are focused on Si/SiO2 and MWCNT-based structures. Si/SiO2 represents the most classical ISFET configuration and serves as a useful baseline reference to highlight the improvements achieved with alternative materials. On the other hand, MWCNTs are an important class of carbon nanomaterials with excellent conductivity and surface properties and thus provide a relevant nanomaterial benchmark. By comparing our MXene/High-k with both a traditional (Si/SiO2) and a nanomaterial-based (MWCNT) reference, we demonstrate the advancement of our approach across two important categories of ISFET pH sensors, while also acknowledging the established contributions of oxide-based devices.

BioFET structural details

This section breaks down each of the three material profiles defined in the model, explaining the rationale behind their characteristic parameters.

Device 1: standard silicon (Si/SiO2) BioFET

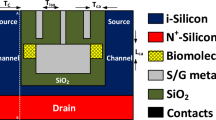

Figure 1 represents the most traditional and well-established BioFET architecture. It is based on a standard n-channel Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistor (MOSFET) built on a silicon substrate with a silicon dioxide (SiO2) gate dielectric. The sensing occurs when charged biomolecules at the SiO2 surface modulate the electric field in the silicon channel. The typical threshold voltage for a standard n-channel enhancement-mode silicon is around 0.5 V, which requires a positive gate voltage to turn on.

Device 2: proposed MWCNT BioFET

Figure 2A represents a BioFET where the channel is formed by a network of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) deposited on a standard SiO2 dielectric. This proposed FET sensor are front gate devices made on silicon substrate with SiO2 layer. The channel between source and drain are made up of MWCNT.

Device 3: proposed MXene BioFET

Proposed MXene BioFET shown in Fig. 2B models a next-generation BioFET using a 2D material, specifically MXene (Ti3C2Tx), as the channel. Due to the sensitivity of MXenes to oxidation, a protective and functional high-k dielectric layer of Al2O3 is used on top. These proposed FET sensors are front gate devices made on silicon substrate with SiO2 layer. The bio-recognition layer acts as a gate for detecting variations in pH and other bio-sensitive analytes, including ions, proteins, enzymes, and nucleic acids, thereby enabling selective and sensitive biochemical sensing.

Mathematical model of BioFET sensor

In 1970, P. Bergveld introduced the ion-sensitive FET (ISFET), a novel device derived from the conventional metal-oxide-semiconductor FET (MOSFET) where a liquid gate replaced the traditional metal gate electrode22. The ISFET can be transformed into a bio-FET by functionalizing its sensing surface with specific receptor molecules. The binding of charged target molecules to these receptors modulates the potential distribution and electrostatic interaction within the device. For a conventional MOSFET operating in the linear region, the drain-to-source current (Ids) is described by the following equation:

For saturation region, Ids is given as:

Here, COX denotes the insulator capacitance per unit area, µref is the carrier mobility within the channel, \(\:V\)gs and \(\:V\)ds are the applied gate and drain voltages, and L and W represent the length and width of the FET, respectively. \(\:{\uplambda\:}\) is channel modulation parameter. For the Si/SiO2 Bio-FET, the threshold voltage is calculated using the classical MOSFET equation as follows:

Here, \(\:{\varPhi\:}_{ms}\) signifies the work function difference between the metal (\(\:{\varPhi\:}_{m}\)) and the semiconductor (\(\:{\varPhi\:}\)s). QOX, QSS, and QB denote the charge in the oxide layer, the charge at the oxide-semiconductor interface, and the depletion charge within the semiconductor, respectively. \(\:{\varPhi\:}_{f}\) represents the Fermi potential. The values of \(\:{\varPhi\:}_{ms}\) ≈ − 0.75 V, 2\(\:{\varPhi\:}_{f}\) ≈ 0.87 V, QB ≈ 2.4 × 10−7 C/cm2, QOX ≈ 1.0 × 10⁻8 C/cm2 and Qss ≈ 4.8 × 10−5 C/cm2 are used in the calculations. The resulting threshold voltage is close to the 0.5 V used in our simulations.

For advanced channel materials (MXene and MWCNT), the threshold voltage expression simplifies to:

since bulk-related terms (2\(\:{\varPhi\:}_{f}\), QB) are not directly applicable. The threshold voltage in these cases is mainly governed by the work function difference (\(\:{\varPhi\:}_{ms}\)) and interface charges (Qss), with values consistent with experimental reports on these materials. For a bio-FET, since the gate is exposed to a solution and the gate voltage is applied via a reference electrode, its threshold voltage (Vt0, eff) is given below as:

where \(\:{\varDelta\:\text{V}}_{t0}\) is change in threshold voltage induced by bio sensing material is given by:

where \(\:{\delta\:}_{pH}\) is intrinsic chemical sensitivity (assumed to be 0.05 V/pH for all devices). pH and pHref are pH value of material and reference pH value. The parameter δpH is an intrinsic property of the sensing dielectric surface (e.g., SiO2, Al2O3, HfO2), rather than the semiconductor channel material (Si, MXene, MWCNT). In our comparative modeling framework, we assumed the same intrinsic chemical sensitivity across the devices in order to isolate and highlight the effect of different channel materials on the overall electrical transduction process. This ensures a fair comparison and the gate dielectric responds equally to pH changes, while differences in the device output arise from the channel properties and electrostatics. The model for drain current incorporates significant factors, one of which involves subthreshold conduction, temperature effects, noise effects and mobility degradation. Table 1 gives the details of parameters used for the model and their respective values for three devices.

Fabrication feasibility of the proposed MWCNT and MXene-based BioFET

MWCNT fabrication is the combination of bottom-up material deposition with top-down lithography. First start with a Si/SiO2 substrate. The SiO2 surface may be pre-treated to promote CNT adhesion. The process of dispersion is used to disperse MWCNTs in a solvent of deionized water with a sodium dodecyl sulfate surfactant. Then deposit the MWCNT solution onto the substrate via drop-casting or spin-coating to form a random network. The photolithography process is used to define the source and drain electrodes. Deposition of metal (Ti/Au) contacts that have good adhesion to carbon is used for creating the metal contacts. The area of the MWCNT network between the source and drain electrodes automatically becomes the transistor channel. Excess MWCNTs outside this area can be removed with a plasma etch if required. With passivation process a protective layer is deposited, leaving the CNT channel exposed for sensing. The method of acid treatment (with H2SO4/HNO3) is used to create carboxyl (–COOH) groups on the nanotube surfaces, which can then be used for covalent linking of probes. This helps to enable the probe attachment to achieve the bio-functionality of MWCNTs23,24.

MXene fabrication process involves a bottom-up approach for the channel material combined with top-down lithography. The process starts with a base substrate, typically a heavily doped Si wafer with a layer of SiO2 (Si/SiO2). With etch process, aluminium (Al) layer is etched from a MAX phase precursor (e.g., Ti3AlC2) using an acid like HF or HCl/LiF. Then we delaminate the resulting multilayered MXene into single or few-layer flakes in solution, often using sonication. The MXene channel is formed by the process of deposition. The MXene flakes from the solution is deposited onto the substrate using methods like drop-casting or spin-coating. The process of photolithography is used to define the source and drain contact areas. Deposition of metal (Au) contacts is done. The lift of process is used to remove unwanted metal. The another process of lithography can be used to remove excess MXene layer. The native surface terminations (–O, –OH, –F) on MXenes are highly suitable for direct covalent bonding of biomolecules, often simplifying the functionalization process compared to silicon25,26,27,28.

Results and discussions

The transfer characteristics drawn between drain current and gate to source voltage (Id–Vgs) is shown in Fig. 3, provide a fundamental comparison of the three device profiles at a baseline (pH 7). The drain to source voltage (Vds) is kept at 1 V. The Vgs is varied from − 1 V to 2.5 V. MXene/High-k device exhibits the highest drain current (Id) for a given gate voltage (Vgs). This is a direct consequence of the high carrier mobility and high gate capacitance assigned in the model, both of which contribute to a large transconductance. The negative threshold voltage effect is also evident as the device begins to conduct current even at slightly negative Vgs. The Si/SiO2 device shows moderate current levels. This represents the well-understood, standard performance of a traditional MOSFET. MWCNT/SiO2 device shows the lowest current. While the intrinsic mobility of a single nanotube is high, the model correctly captures the lower effective mobility of a network, resulting in a lower overall current drive compared to the other materials. Its turn-on voltage is very close to zero, consistent with a network containing metallic pathways. The MXene/High-k profile demonstrates the highest potential for generating a large electrical signal due to its superior electrical properties. A larger current allows for a larger absolute change upon sensing, which can improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Figure 4 shows the drain current as a function of pH. The MXene/High-k device shows the largest absolute change in current across the pH range, again due to its high transconductance. A given change in threshold voltage induced by a pH change results in a larger change in drain current for a high-transconductance device. The Si/SiO2 and MWCNT/SiO2 devices show a smaller, but still clear, response.

The Id-Vds plots in Fig. 5A–C illustrate how the drain current is modulated by pH at a fixed gate voltage (Vgs = 1.5 V). The Vds is swept between from 0 to 2.5 V. For each material, as the pH increases, the threshold voltage increases, leading to a lower drain current. The curves clearly show the linear and saturation regions of operation. The separation between the curves for different pH values is most pronounced for the MXene/High-k device, again indicating higher sensitivity. The Si/SiO2 and MWCNT/SiO2 devices also show clear modulation but with smaller current changes between pH steps.

The transduction sensitivity is shown in Fig. 6. It shows the ability of the transistor to convert the change in threshold voltage into a measurable drain current change is governed by its transconductance (gm), which is directly related to mobility and gate capacitance. The plot confirms that MXene/High-k device with higher mobility and gate capacitance produces a larger output signal for the same biological event, thereby offering higher sensitivity. While the MWCNT device shows lower current, its advantage in a real-world scenario would be its extremely high surface area, which could potentially lead to a larger number of binding events and thus a larger ΔVt than modeled, partially compensating for its lower electrical performance. The Si/SiO2 device serves as the reliable, well-understood benchmark against which these newer materials are compared.

For pH sensing, the MXene device with the highest transconductance (as portrayed in Fig. 7) provides the highest current sensitivity. The simulation results consistently demonstrate a key principle of BioFET design that is sensitivity of the sensor is a product of both the biological interface and the electrical properties of the transistor.

Table 2 presents a valuable comparison of various pH BioFETs based on their core performance indicators. It provides a comparison of different pH sensor technologies. The sensitivity of a pH sensor, measured in millivolts per pH unit (mV/pH), is a critical metric for determining how well it responds to changes in pH. The MXene/High-K design, labeled demonstrates the highest sensitivity at 65.35 mV/pH. This value is significantly higher than most other entries and surpasses the theoretical Nernstian limit of approximately 59 mV pH at room temperature, suggesting a highly efficient transduction mechanism. Materials like Iridium Oxide (17.15 mV/pH)30, Graphite (4 mV/pH)29, and PEDOT: BTB (8.3 mV/pH)31 show notably lower sensitivities. The CNT/Polyaniline32 sensors have sensitivities of 60 mV/pH and 45.9 mV/pH respectively, which are also high but still below the MXene/High-K design. The ZnO33 and PANI35 sensors show negative sensitivity values (− 59 mV/pH and − 56.2 mV/pH), indicating a reverse trend in response. This is not unusual for pH sensors and shows that their sensitivity is close to the Nernstian ideal.

Response time (RT) is crucial for real-time monitoring applications, such as in clinical diagnostics or industrial processes. The MXene/High-K design stands out with the fastest response time recorded in the table at just 2.4 s. The Graphite sensor has a response time of 5 s, and HxWO3 has a response time of 10.5 s. Most other entries lack a reported response time, which makes a direct comparison difficult, but the MXene/High-K sensor’s speed is a significant advantage. Linearity is measured by the coefficient of determination (R2) and indicates how well the sensor’s response follows a straight line over its detection range. A value closer to 1 signifies more reliable and accurate measurements. The MXene/High-K sensor exhibits a very high linearity with an R2 value of 0.9984, suggesting excellent consistency and reliability within its detection range. The PEDOT: BTB sensor also has a high linearity of 0.997. Other entries do not report this value.

Finally, in light of the comparative analysis with recent literature (Table 2), the MXene/high-k design demonstrates promising near-Nernstian voltage sensitivity and competitive transduction efficiency relative to leading oxide and 2D-material pH sensors within comparable pH windows and operating conditions.

To clarify the positioning of our proposed device, it is important to compare the three commonly reported ISFET-based pH sensing approaches—potentiometric, amperometric, and impedancemetric—against the BioFET configuration used in this work. Potentiometric ISFETs remain the most widely adopted for pH monitoring due to their simplicity and direct transduction of proton concentration into electrical signals, although they are often limited by drift and Nernstian sensitivity. Amperometric sensors offer high current-based responses but depend on specific redox reactions and can suffer from electrode fouling, while impedancemetric sensors provide excellent sensitivity but are prone to noise and stability issues in complex media. As summarized in Table 3, our BioFET belongs to the potentiometric ISFET family but leverages MXene/MWCNT High-k dielectric materials to achieve enhanced sensitivity, lower detection limits, and improved robustness against interference. These features make the proposed device highly promising for real-time biomedical applications, particularly in sweat, saliva, and interstitial fluid monitoring.

Discussions

In this paper, a theoretical comparison of Si/SiO₂, MWCNT/SiO2, and MXene/High-k BioFETs is done, which provides useful predictive insights but also involves some limitations. The results presented here should be interpreted as predictive benchmarks that highlight material/channel-dependent trends rather than absolute performance values. The model assumes ideal material properties, uniform High-k dielectric behavior, and stable interfaces, while neglecting variability in material synthesis, device fabrication, and surface chemistry. Real-world devices often encounter non-ideal electrolyte/dielectric interactions, including drift, hysteresis, and charge trapping, which can reduce long-term stability. This work specifically targets biomedical applications by proposing BioFETs for non-invasive monitoring of pH biomarkers. The sensors are envisioned in patch-based formats for detecting pH in sweat or saliva, which are valuable indicators for real-time health monitoring and disease management. This work highlights the significance of accurately tracking these biomarkers and demonstrates how the proposed pH BioFETs can enhance measurement precision. Furthermore, the devices are designed using biocompatible materials, with the potential to be flexible, bendable, and disposable, making them suitable for practical biomedical deployment.

The present analysis demonstrates a generic pH-sensing framework that achieves both high sensitivity and stability, features highly relevant to biomedical applications. The observed response across pH 5–9 covers the clinically important range of ~ 6–8, enabling accurate detection of subtle variations in blood or interstitial fluid (ISF) that are diagnostically significant. Furthermore, the high capacitance of the MXene/MWCNT dielectric improves the signal-to-noise ratio, which is particularly beneficial in protein-rich or viscous environments such as serum or saliva, where conventional ISFETs often exhibit drift and reduced accuracy. These advantages suggest that the proposed sensing platform holds promise for clinical applications, including continuous blood monitoring in intensive care units, saliva-based point-of-care diagnostics, and wearable pH monitoring through ISF. Nonetheless, experimental validation in real biological matrices remains a limitation of this study. Addressing challenges such as biofouling, protein interference, and long-term stability will be an important direction for future work to fully establish the biomedical potential of this approach.

Conclusions and future work

This paper has presented a comparative theoretical analysis of BioFET pH sensor designs based on Si/SiO₂, MWCNT/SiO₂, and MXene/High-k dielectric materials, highlighting their potential for bio-medical applications. The findings consistently demonstrate that the sensitivity of a BioFET sensor is a product of both the biological interface and the electrical properties of the transistor. The traditional Si/SiO₂ device serves as a reliable benchmark, leveraging well-established fabrication processes and good material properties for integrated and miniaturized sensors. However, challenges regarding long-term stability, drift, and calibration persist for widespread clinical use. MWCNT-based sensors, while exhibiting lower current drive in a network configuration, offer advantages due to their exceptional electrical conductivity, large surface area, and chemical stability, along with ease of functionalization for enhanced sensing capabilities. The proposed MXene/High-k device shows the most significant promise, demonstrating the highest drain current and transduction sensitivity. This superior performance is attributed to the high carrier mobility and gate capacitance of MXenes, which lead to a larger output signal for the same biological event, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio. The inherent sensitivity of MXenes to pH changes, coupled with the enhanced dielectric properties of high-k materials, positions them as excellent candidates for advanced pH sensing devices with improved stability in complex biological environments. The fabrication feasibility of both MWCNT and MXene-based BioFETs through combined bottom-up and top-down approaches further supports their practical implementation. This comparative study provides valuable insights for the design and development of next-generation BioFETs for accurate and real-time pH monitoring.

Overall, the present theoretical study should be regarded as a screening tool that highlights promising material/dielectric combinations. The encouraging results for the MXene/high-k configuration serve as motivation for further experimental exploration and optimization. The demonstrated superiority of MXene/High-k devices in the model represents theoretical potential, which will be experimentally validated focusing on fabricating prototype devices, and extending the modeling framework to incorporate reliability and interference factors as future study of this work. A combined theoretical-experimental approach will eventually be essential to validate the predicted advantages and establish the feasibility of these novel BioFET platforms for practical biochemical sensing applications.

Data availability

Yes, and this manuscript’s results are produced through mathematical modeling. The outputs of this modeling can be made available upon reasonable request once the manuscript is accepted. No supplementary datasets were generated or analyzed. Requests for data can be made to Gaurav Dhiman.

References

Ma, X. et al. Large-scale wearable textile-based sweat sensor with high sensitivity, rapid response, and stable electrochemical performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 16 (14), 18202–18212 (2024).

Simonian, A. Á., Flounders, A. W. & Wild, J. R. FET-based biosensors for the direct detection of organophosphate neurotoxins. Electroanal. Int. J. Devoted Fundam. Pract. Asp. Electroanal. 16 (22), 1896–1906 (2004).

Zhang, S. et al. Epidermal patch with biomimetic multistructural microfluidic channels for timeliness monitoring of sweat. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 15, 469–478. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c17583 (2023).

Zhao, H., Zhang, L., Deng, T. & Li, C. Microfluidic sensing textile for continuous monitoring of sweat glucose at rest. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 16, 19605–19614. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c01912 (2024).

Rdest, M. & Janas, D. Carbon nanotube wearable sensors for health diagnostics. Sensors 21, 5847 (2021).

Wang, K. et al. Carbon nanotube field-effect transistor based pH sensors. Carbon. 205, 540–545 (2023).

Sinha, S. & Pal, T. A comprehensive review of FET-based pH sensors: materials, fabrication technologies, and modeling. Electrochem. Sci. Adv. 2(5), e2100147 (2022).

Hwang, D. W., Lee, S., Seo, M. & Chung, T. D. Recent advances in electrochemical non-enzymatic glucose sensors—a review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1033, 1–34 (2018).

Diallo, A. K. et al. Development of pH-based ElecFET biosensors for lactate ion detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 40 (1), 291–296 (2013).

Bulgakova, A. et al. Solution pH effect on drain-gate characteristics of SOI FET biosensor. Electronics 12 (3), 777 (2023).

Sohn, I. Y. et al. pH sensing characteristics and biosensing application of solution-gated reduced graphene oxide field-effect transistors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 45, 70–76 (2013).

Sudha, P. B. & Narayanan, B. A review on ion-sensitive field effect transistors (ISFETs). Proc. Eng. 30, 111–118 (2012).

Bratov, A. V. & Schöning, M. J. pH-sensitive field-effect transistors. In Electrochemistry of Nanomaterials, 531–558 (Springer, 2007).

Kiani, M. J., Razak, M. A. A., Che Harun, F. K., Ahmadi, M. T. & Rahmani, M. SWCNT-based biosensor modelling for pH detection. J. Nanomater. 2015(1), 721251 (2015).

Zamzami, M. A. et al. Carbon nanotube field-effect transistor (CNT-FET)-based biosensor for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) surface Spike protein S1. Bioelectrochemistry. 143, 107982 (2022).

Xu, B., Zhi, C. & Shi, P. Latest advances in MXene biosensors. J. Phys. Mater. 3 (3), 031001 (2020).

Alvandi, H., Asadi, F., Rezayan, A. H., Hajghassem, H. & Rahimi, F. Ultrasensitive biosensor based on MXene-GO field-effect transistor for the rapid detection of endotoxin and whole-cell E. coli in human blood serum. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1348, 343816 (2025).

Han, M. et al. MXene-based electrochemical sensors: A review. TRAC Trends Anal. Chem. 133, 116082 (2020).

Guo, Y. et al. Fabrication and performance of a Ta2O5 thin film pH sensor manufactured using MEMS processes. Sensors 23 (13), 6061. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23136061 (2023).

Kamarozaman, N. S. et al. Highly sensitive and selective sol-gel spin-coated composite TiO2–PANI thin films for EGFET-pH sensor. Gels 8 (11), 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels8110690 (2022).

Chin, Y. L. et al. A novel SnO2/Al discrete gate ISFET pH sensor with CMOS standard process. Sens. Actuators B. 75 (1–2), 36–42 (2001).

Lee, D. & Cui, T. Low-cost, transparent, and flexible single-walled carbon nanotube nanocomposite based ion-sensitive field-effect transistors for pH/glucose sensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 25 (10), 2259–2264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2010.03.003 (2010).

Tam, P. D., Van Hieu, N., Chien, N. D., Le, A. & Tuan, M. A. DNA sensor development based on multi-wall carbon nanotubes for label-free influenza virus (type A) detection. J. Immunol. Methods. 350 (1–2), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2009.08.002 (2009).

An, J. et al. Extended-gate field-effect transistor consisted of a CD9 aptamer and Mxene for exosome detection in human serum. ACS Sens. 8 (8), 3174–3186 (2023).

Ali, A. et al. Recent advancements in MXene-based biosensors for health and environmental applications—a review. Biosensors 14 (10), 497 (2024).

Li, Q., Chen, X., Wang, H., Liu, M. & Peng, H. PT/MXENE-based flexible wearable non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor for continuous glucose detection in sweat. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 15 (10), 13290–13298. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c20543 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Superhydrophobic functionalized Ti3C2T X MXene-based skin-attachable and wearable electrochemical pH sensor for real-time sweat detection. Anal. Chem. 94, 7319–7328 (2022).

Chaudhary, V. et al. Towards hospital-on-chip supported by 2D MXenes-based 5th generation intelligent biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 220, 114847 (2023).

Siva, S., Bodkhe, G. A., Cong, C., Kim, S. H. & Kim, M. Electrohydrodynamic-printed ultrathin Ti3C2Tx-MXene field-effect transistor for probing aflatoxin B1. Chem. Eng. J. 479, 147492 (2024).

Manjakkal, L., Dang, W., Yogeswaran, N. & Dahiya, R. Textile-based potentiometric electrochemical pH sensor for wearable applications. Biosensors 9, 14 (2019).

Zamora, M. L. et al. Potentiometric textile-based pH sensor. Sens. Actuators B. 260, 601–608 (2018).

Mariani, F. et al. Design of an electrochemically gated organic semiconductor for pH sensing. Electrochem. Commun. 116, 106763 (2020).

Choi, M. Y. et al. A fully textile-based skin pH sensor. J. Ind. Text. 51, 441S–457S (2022).

Maiolo, L. et al. Flexible pH sensors based on polysilicon thin film transistors and ZnO nanowalls. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105 (2014).

Tang, Y. et al. Lattice proton intercalation to regulate WO3-based solid-contact wearable pH sensor for sweat analysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2107653 (2022).

Song, Y. et al. Wireless battery-free wearable sweat sensor powered by human motion. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay9842 (2020).

Sha, R., Komori, K. & Badhulika., S. Amperometric pH sensor based on Graphene–Polyaniline composite. IEEE Sens. J. 17 (16), 5038–5043. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2017.2720634 (2017).

Folkertsma, L., Gehrenkemper, L., Eijkel, J., Gerritsen, K. & Odijk, M. Reference-electrode free pH sensing using impedance spectroscopy. Proceedings. 2(13), 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2130742 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to DIT University, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India and Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.D.: Conceptualization, resources software, formal analysis, validation, conceptualization, data curation, validation, A.R.: Writing-original draft, visualization, writing review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

The author has given their consent to publish this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable. The work presented in this manuscript is mathematical modeling only for the proposed biosensor. No experiment was performed on the human body and living organism/ animal. So, ethical approval from an ethical committee is not required.

Consent to participate

The authors are willing to participate in the work presented in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dhiman, G., Routray, A. Theoretical analysis of MWCNT and MXene/High-k pH BioFET sensors for biomedical applications. Sci Rep 15, 35990 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19805-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19805-x