Abstract

Terracing is widely distributed in mountainous and hilly areas worldwide to increase grain production, control soil erosion, increase soil moisture, and improve soil quality, potentially impacting soil carbon pools. This study investigates how agricultural activities and ecological restoration measures affect soil carbon pools in terraced areas of the Chinese Loess Plateau. We established an observation system in typical terraces and collected soil samples from 0 to 100 cm depth in terraces with different crops and ecological restoration vegetation. Our results show that terracing effectively increases soil organic carbon (SOC) content, with terraced cropland (7.7 g kg− 1) having higher SOC than sloping cropland (4.9 g kg− 1), In the 0–100 cm layer, SOC content in terraced wheat fields was 1.5 times higher than in sloping wheat fields, with the most significant increase in the top 0–30 cm. This increase is attributed to improved soil and water conservation capacity and agricultural activities. Short-term abandonment led to SOC loss, while replanting fruit trees and crops increased SOC. Our findings provides valuable insights for agricultural management and ecological restoration in terraced areas of the Loess Plateau and contributes to the development of effective carbon sequestration policies for terraced arable lands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil organic carbon is a key element of the global carbon cycle1 and serves as a significant indicator for assessing soil quality and land productivity2,3. In the context of global climate change, understanding SOC dynamics in anthropogenic landscapes, is of great importance to is crucial for developing effective carbon sequestration strategies while maintaining agricultural sustainability. Despite the importance of soil carbon, SOC reserves have been declining worldwide4, highlighting the urgent need for management practices that can enhance carbon storage while supporting agricultural production and ecological restoration.

Agricultural terracing is a crucial landscape engineering measure to reduce soil erosion, maintain soil fertility, and increase agricultural productivity5,6, which is one of the ways to achieve sustainable agricultural development. The conversion of slopes into terraces significantly increases the cultivated area. Moreover, it helps prevent erosion problems7 and effectively increases food production8. Terraces are widely distributed and have created environmental benefits in countries in East Asia, the Mediterranean, and Southeast Asia9. Terracing has been practiced in China for millennia as a traditional agricultural technique, with some ancient terraces dating back to the Han Dynasty over 2000 years ago. However, the widespread implementation of terraced fields in the Loess Plateau region is relatively more recent, with approximately 85% of the current terraces constructed between 1950 and 2000 as part of systematic soil and water conservation efforts. The terracing promotion during this stage significantly altered regional soil organic carbon (SOC) dynamics: Surface SOC content and carbon storage exhibited a phased accumulation trend under the synergistic effects of cultivation intensity, cover management, and crop rotation practices, while the improvement of microbial habitats and aggregate structure promoted carbon stabilization. Currently, terracing construction is transitioning towards more refined management and enhanced ecological functions, gradually incorporating governance approaches that integrate agroforestry complexes, energy-food coupling, and carbon sink function optimization. Terraced fields that were established earlier typically have higher soil organic carbon content. This is because these older terraces have undergone a longer process of soil organic matter accumulation, resulting in the accumulation of more fresh organic matter, which enhances soil organic carbon storage. This enhancement is primarily attributed to reduced erosion, improved water retention, and the gradual accumulation of organic matter over time10,11. In contrast, newly constructed terraces often have lower organic carbon content due to the removal of topsoil, which requires a longer time for soil organic matter reconstruction12,13. The construction process of terraces fundamentally alters soil structure and carbon dynamics. During terrace establishment, the excavation of hillslopes and redistribution of soil materials unavoidably disrupts the original soil profile, often resulting in topsoil removal and subsoil exposure on terrace surfaces14. This disturbance temporarily reduces SOC content and alters its vertical distribution within the soil profile15. However, over the long term, the enhanced water retention capacity and reduced erosion rates of properly maintained terraces create favorable conditions for carbon accumulation and stabilization. Research has shown that terraced soils can contain significantly more unprotected SOC (such as coarse particulate organic carbon) compared to non-terraced soils, indicating enhanced potential for carbon storage when appropriate management practices are implemented16,17. During the construction of terraces, it is inevitable to strip topsoil and expose deep soil, resulting in a large amount of new subsoil covering the surface of the terraces. This severe soil disturbance may alter soil organic carbon dynamics12, but the potential long-term benefits of terrace construction are considerable15. Nevertheless, many terraces are experiencing ridge damage and collapse due to a lack of maintenance or land abandonment. This not only reduces soil and water conservation benefits but also potentially increases erosion and carbon emissions7.

Beyond physical landscape modification, vegetation type plays a crucial role in determining SOC content and distribution within terraced systems18. Since 2000, significant land use changes have occurred across the Loess Plateau region, through the implementation of ecological restoration programs, including the conversion of arable land to woodland and grassland19,20,21. These vegetation changes have profound implications for carbon sequestration, as different plant communities vary in their capacity to contribute organic inputs to soil and influence microbial processes that regulate carbon cycling22. Recent research has shown that natural vegetation and afforested sites typically exhibit higher SOC storage compared to croplands, with variations in both the quantity and quality of stored carbon23. The integration of trees with crops in agroforestry systems has demonstrated particular promise for enhancing SOC sequestration while maintaining agricultural production24,25,26.

While previous studies have documented the general effects of terracing and vegetation type on topsoil organic carbon, several critical knowledge gaps remain. First, most research has focused exclusively on surface soils (0–30 cm), potentially overlooking significant carbon dynamics in deeper soil layers that may respond differently to land management practices27. Recent studies suggest that deep soil carbon (below 30 cm) constitutes a substantial portion of the total soil carbon pool and may exhibit distinct responses to management interventions28. Second, the interactive effects of terracing, abandonment duration, and vegetation succession on SOC fractions remain poorly understood. Carbon fractions differ in their stability and turnover rates, with implications for long-term carbon sequestration potential. Understanding how management practices influence different carbon pools is essential for developing effective carbon management strategies22. Third, there is limited information on how specific management practices modify the carbon sequestration benefits of terracing15. Therefore, we collected soil samples from terraced fields and slopes, including terraces with different land uses and crop types. Our focus was on three main aspects: (1) to quantify and compare SOC stocks and vertical distribution patterns (0–100 cm depth) across terraces under different land use types (cropland, grassland, forest) and management regimes, assessing how these factors interact to influence carbon storage potential; (2) to investigate the temporal dynamics of SOC following terrace abandonment by analyzing a chronosequence of abandoned terraces, determining how carbon content and fractions change with abandonment duration and vegetation succession; (3) to evaluate the relationships between different vegetation types and SOC fractions, identifying mechanisms through which vegetation influences carbon stabilization and long-term sequestration in terraced systems. This study provides innovative insights for comprehensively understanding the carbon cycling processes in the terraced systems of the Loess Plateau, proposing targeted management measures to promote the sustainable development of terraced agriculture and mitigate climate change.

Data and methods

Study area

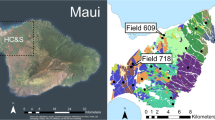

Zhuanglang County is located in the central region of the Loess Plateau (Fig. 1). The area has a temperate continental climate with an average annual precipitation of 542 mm, of which more than 60% occurs in summer and autumn (July to October), and an average annual temperature of 7.5 °C. The area is characterized by loess hilly terrain, with deeply incised gullies, complex topography, and an altitude of 1,521 to 1,784 m29. The dominant soil type in this area is fine loessial soil, the natural vegetation is mainly herbaceous, shrubs, coniferous forests, and locust trees, and the crops are wheat, maize, potatoes, and apple trees. The construction of terraces in Zhuanglang County began in the 1960s as part of a large-scale soil and water conservation effort aimed at controlling soil erosion and improving agricultural productivity. The terraces in the area are mainly level bench terraces, constructed by cutting and filling hillsides to create flat planting surfaces with stable risers. This terracing method has been systematically implemented throughout the county, resulting in one of the most extensive and well-preserved terraced landscapes on the Loess Plateau. Due to the constraints of soil properties and irrigation water sources in this region, the growth of crops depends on natural rainfall. In recent years, however, there has been a significant increase in abandoned terraces, highlighting the widespread issue of terrace abandonment in the Loess Plateau area.

Terraced soil sample collection

We carried out soil sample collection at the terrace observation system in Yangpota mountain, Dazhuang Town, Zhuanglang County, with the sampling date being October 2020. The agricultural fields in the area had been constructed in 1991. The main terracing structure built in the region is the horizontal terrace, which is an agricultural field with stepped sections along contours on the slopes of loess hills. The width of the terraces varies from 1.6 to 6 m, and the height of the terrace steps varies from 0.3 to 0.8 m. The terraced slopes are slightly counter-sloped to collect more precipitation and the slope ranges from 0% to 11%.

We randomly set up 84 sampling sites in the study area, with 77 terraced sampling sites and 7 slope sampling sites. Crop type, cropping pattern, and agricultural abandonment all affect the soil carbon pool of the terraces, so the terraces included sampling points for different cropping patterns of apple trees (9), number of sampling points, vegetable (9), wheat (9), legume (9), potato (9), maize (9), apple tree-legume (3) and apple- potato (3) (Appendix, Fig. S1). Five abandoned apple tree terraces were included in the terraces and the apple trees were not removed from the terraces and there was a large amount of weed growth. Three types of restored vegetation were planted on the terraces: Robinia pseudoacacia L. (4), Pinus tabuliformis Carr. (4) and Medicago sativa L. (4). The seven slope sites included four wheat plantations and three natural grassland sites (Table 1).

Measuring SOC concentrations in the surface layer of the soil (10–20 cm) alone does not imply soil changes due to tillage management, so we designed the sampling depth as 1 m. For each identified sample plot, a 2 × 2 m² area was randomly delineated, and soil samples were collected along the diagonal line at three points within this area. For each soil layer (0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, 20–30 cm, 30–40 cm, 40–50 cm, 50–60 cm, 60–70 cm, 70–80 cm, 80–90 cm, and 90–100 cm), the three samples collected from the same plot were thoroughly mixed after removing plant roots and debris to create a composite sample representative of that layer. This process resulted in a total of 840 mixed soil samples (84 plots × 10 depth intervals).

The soil pH value data and soil organic carbon (SOC) distribution data are sourced from the National Tibetan Plateau Scientific Data Center30 (https://doi.org/10.11888/Soil.tpdc.270281).

Experimental analysis and data statistics

The collected soil samples were placed in sealed plastic bags and pre-weighed aluminum boxes. The soil samples in the aluminum box were dried in the bake oven at 105 °C for 24 h to measure the soil moisture. After the samples were completely air-dried at ambient temperature in a shaded laboratory area (to prevent direct sunlight exposure that could affect organic carbon), gravels and plant roots were removed from the samples using a sieve with a particle size of 2 mm. A 0.2 g soil sample was weighed and the concentration of SOC was measured using a wet oxidation method with dichromate31. The soil texture, including sand, silt, and clay content, was analyzed through a laser diffraction technique utilizing a Mastersizer 2000 (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, England).

All data in this paper were analyzed by SPSS 21 statistical software. All collected data underwent normality testing using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and were assessed for homogeneity of variance with Levene’s test, ensuring P > 0.05. Comparative analysis of various management types was performed utilizing a one-way ANOVA, with significance considered at P ≤ 0.05.All data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. Graphs were made using Origin 2021 software.

Results

SOC characteristics of different land use types

The SOC content of the abandoned apple tree terraces (7.46 ± 0.76 g kg-1) was lower than that of the in-use apple tree terraces (8.16 ± 1.02 g kg-1), with a difference of 0.7 ± 1.27 g kg-1. However, this difference was not statistically significant according to ANOVA (F = 0.01, p = 0.92). The SOC content of the wheat-grown sloping fields was significantly lower than that of the wheat-grown terraces, with the SOC content of the terraces being 1.5 times higher than that of the sloping fields, with a difference of 3.8 g kg-1 between the two (7.7 g kg-1 > 4.9 g kg-1). ANOVA confirmed this difference was statistically significant (F = 5.10, p = 0.045). The SOC content of natural grassland was slightly higher (6.0 g kg-1 > 5.6 g kg-1) compared to planted grassland, although natural grassland with weeds had not been terraced. Slopes with natural vegetation were higher in SOC (6.0 g kg-1) than those under cultivation (4.9 g kg-1) (Table 1).

The vertical variation of SOC at 0–100 cm depth varied among land use types (Fig. 2). Except for the abandoned land, all land use types showed an irregular decreasing change pattern from the surface layer to the deep layer of the soil. In the 0–10 cm soil layer, the highest SOC content was found in terraces planted with wheat and the lowest SOC content was found in terraces planted with M. sativa (ANOVA, F = 8.24, p = 0.007). Terraces planted with fruit trees had significantly higher SOC content at 80–100 cm depth than terraces planted with crops, M. sativa, and natural grassland (ANOVA, F = 4.15, p = 0.032). The vertical variation of SOC in sloping fields and terraces planted with wheat was consistent, with their greatest SOC content occurring at 0–20 cm depth and their smallest SOC content at 90–100 cm depth. In the abandoned terraces, SOC varied between 0 and 80 cm, with the smallest SOC content occurring in the 80 cm soil layer.

Bars denote the standard deviation of the mean, n represents the number of soil profiles.

Characteristics of SOC in terraces of different planting patterns

Differences in SOC were smaller in terraces planted with apple trees and greater between terraces planted with a single crop (ANOVA, F = 3.14, p = 0.024). Among all crop types, legumes had the lowest SOC content (4.5 g kg− 1) and maize had the highest SOC content (7.7 g kg− 1). The SOC content of concurrent apple tree - legumes and apple tree - potatoes was higher than that of legumes and potatoes grown alone (5.4 g kg− 1 > 4.5 g kg− 1 and 6.7 g kg− 1 > 5.2 g kg− 1) (Table 1).

The vertical distribution of SOC content across a depth of 0–100 cm showed a consistent decline from the surface soil to the deeper layers for all crops. The SOC content (15.1 g kg− 1) of wheat cultivated terraces was the highest among all crops at the soil surface (0–10 cm). Terraces planted with apple trees, maize, or wheat had higher SOC content in deeper soils (30–100 cm). Beans and potatoes had lower SOC content at 50–100 cm depth than terraces planted with other crops. The difference in SOC content between potato terraces planted alone and apple tree-potato terraces at 0–20 cm depth was not significant. However, below 20 cm depth, the SOC content of the apple tree-potatoes combination was significantly higher than that of the terraces planted with potatoes alone. This difference is also reflected in the legumes and apple tree-legumes (Fig. 3).

Bars denote the standard deviation of the mean, n represents the number of soil profiles.

Characteristics of SOC in terraces with different ecologically restored vegetation

Comparing the SOC characteristics of the three types of ecologically restored vegetation after terracing, the average SOC content of terraces planted with trees 0–100 cm was higher than that of terraces planted with forage (ANOVA, F = 6.32, p = 0.013) (Table 1). In the 0–10 cm surface layer, the SOC content under alfalfa was significantly lower than that under the two tree species (ANOVA, F = 7.18, p = 0.009). This difference became smaller in the 10–20 cm depth (ANOVA, F = 2.86, p = 0.073, not significant). However, the difference increased again in the 20–60 cm depth (ANOVA, F = 4.92, p = 0.022). At 70–100 cm, the difference between the three vegetation types became smaller, with their SOC contents converging (ANOVA, F = 1.25, p = 0.318, not significant).

The difference in SOC between different silvicultural species was higher in P. tabuliformis than in R. pseudoacacia at 0–100 cm depth, with a difference of 1.83 g kg− 1 (ANOVA, F = 9.78, p = 0.006). The significant difference in SOC between the two species was mainly at 0–70 cm depth, where P. tabuliformis had a higher SOC content than R. pseudoacacia. The difference in SOC content between the two species became smaller at the depth of 70–100 cm, and the SOC content of R. pseudoacacia was slightly higher than that of P. tabuliformis (Fig. 4).

Bars denote the standard deviation of the mean, n represents the number of soil profiles.

Effects of terrace construction and abandonment on soil properties

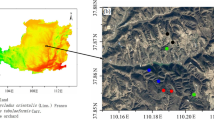

In the Loess Plateau area, the average SOC content of terraces 0–100 cm is 1.4 times higher than that of sloping farmland (ANOVA, F = 5.10, p = 0.045) (Table 1). The SOC content decreases with increasing depth, as shown in Fig. 5. The data show that areas with steeper slopes generally have lower soil organic carbon (SOC) content, while areas with gentler slopes tend to have higher SOC content. Figure 5 demonstrates that the soil organic carbon (SOC) content in the surface layer is significantly higher than that in the deeper layers. Compared to sloping land, terraces have a higher content of both clay and silt in the soil.

(a): Slope; (b): Distribution of SOC at 0–5 cm; (c): Distribution of SOC at 5–15 cm; (d): Distribution of SOC at 15–30 cm; (e): Distribution of SOC at 30–60 cm; (f): Distribution of SOC at 60–100 cm.

A significant increase in SOC was observed in terraces compared to sloping lands, particularly in the 0–30 cm soil layer (Fig. 6). The rate of SOC change was more pronounced in the surface layer (0–20 cm) compared to the deeper layer (20–100 cm).

(a): Variation in surface morphology by terrace construction; (b): variation in SOC content; (d): variation in soil moisture; (d), (e), and(f): variation in soil grades. The number of profiles is 9 for terraces and 4 for sloping fields. Bars denote the standard deviation of the mean.

Regarding terrace abandonment, we measured the physicochemical properties of the soil in terraced fields with different usage statuses (Table 2). The results show that the soil bulk density in abandoned terraces is significantly higher compared to the actively used ones (ANOVA, F = 4.26, p = 0.037). The soil pH in abandoned terraces has also decreased compared to in-use terraces (ANOVA, F = 3.95, p = 0.042). The surface soil organic carbon (SOC) content in abandoned terraced fields (0–15 cm) is significantly lower than that in actively used terraced fields (ANOVA, F = 5.73, p = 0.018). After short-term abandonment, the terraced fields showed a special change pattern at different depths. SOC content first decreased and then increased with increasing soil depth. The vertical variation of SOC in abandoned terraces varied between 0 and 80 cm, with the smallest SOC content occurring in the 80 cm soil layer.

Discussion

Effect of terrace construction on SOC

Our results demonstrate a positive feedback relationship between soil moisture and soil carbon in the terraced systems we studied. The terraced fields showed higher soil moisture content (24.2% in terraced wheat fields compared to 21.3% in sloping wheat fields, Table 1) along with higher SOC content. This positive relationship occurs because increased soil moisture in terraces provides favorable conditions for plant growth, leading to greater biomass production and subsequently more organic matter input to the soil. The increased organic matter then enhances the soil’s water-holding capacity, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that benefits carbon sequestration32. In the Loess Plateau, terraced farmland exhibits higher soil organic carbon content than sloping farmland, with carbon levels decreasing with soil depth33. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that horizontal terraces alter the surface morphology, prolonging the surface water retention time during rainfall, which increases soil moisture in the rain-fed agricultural regions of the Loess Plateau29. There is a positive feedback relationship between soil moisture and soil carbon34. This may be due to the interception of precipitation by the terraced fields, which provides water for plant growth, increases plant biomass, and subsequently enhances the organic matter input into the soil. Additionally, the interception of rainfall by the terraces means that less soil fine particles are washed away, leading to an increase in the clay content of the soil. Soil clay particles have a larger specific surface area, allowing them to adsorb more soil organic carbon and enhancing the accumulation of organic carbon35. Compared to sloping land, terraces have a higher content of both clay and silt in the soil. The terraces therefore further contribute to carbon accumulation in the terraces by protecting the fine particles in the soil. In a study on the Loess Plateau36, the SOC content of 0–100 cm in unterraced date palm orchards was 2.6 g kg− 1, which was lower than the soc content of terraced orchards. This evidence further demonstrates the positive effect of terracing on soil organic carbon sequestration.

The SOC varies significantly in terms of the amount of plant and animal residues entering the soil and the depth of the soil under agricultural cultivation37. The impact of agricultural activities on the surface soil levels was stronger compared to the deeper soil levels38. This is particularly significant because surface soil plays a crucial role in agricultural productivity and ecosystem functioning. Therefore, the soil and water conservation effect brought by terrace construction is limited, so for the soil depth increases, this effect will become smaller. The impact of terracing on SOC sequestration diminishes as soil depth increases10. As soil depth increases, the water stored in the terraces cannot penetrate deeper soils and deeper soils will maintain their properties. Therefore, the management and conservation of terrace topsoil are important to ensure local food production and enhance the carbon sink function39.

Effect of terraces abandonment on SOC

As in other parts of the world, industrialization and urbanization have led to a large population flock from rural to urban areas as in China, resulting in the abandonment of a large number of productive potential farmlands15,40. Furthermore, climate change induced extreme weather events such as drought and heavy rainfall can also accelerate soil erosion and loss of soil organic carbon in the abandoned terraces41. Several mechanisms appear to drive the SOC decline in abandoned terraces. First, the cessation of fertilization inputs removes a significant source of organic matter. Second, the increased soil bulk density observed in abandoned terraces likely restricts root growth and microbial activity, hampering organic matter incorporation and decomposition processes. Third, the absence of active management may lead to increased erosion, particularly during the initial abandonment phase before natural vegetation becomes established. However, climate change can also impact the vegetation succession on abandoned terraces, which in turn affects the soil organic carbon dynamics42. When the terraced fields were abandoned in this research, the SOC content of the abandoned terraces was lower than that of the terraces in use. This is caused by the limited abandoned time. Abandoned terraces may have accumulated a significant amount of organic matter during their previous use. However, due to a lack of fertilization now, this organic matter is gradually being mineralized and decomposed, which reduces the soil organic carbon (SOC) content41,43. In contrast, terraces that are still in use maintain higher SOC levels thanks to continual fertilization44. Additionally, the abandoned terraces are more susceptible to climate change induced soil disturbance and erosion, leading to the loss of nutrient-rich topsoil, which further decreases SOC levels45. To produce significant environmental benefits, the land must remain abandoned for an extended period to accumulate substantial amounts of both plant biomass and the species that constitute intact ecological communities. This process can take decades to reach levels of carbon sequestration or biodiversity comparable to those of undisturbed ecosystems46,47. Due to the limited water resources available in semi-arid areas, a longer natural or assisted recovery time is required. Therefore, the duration of land abandonment is a crucial factor influencing the dynamic changes SOC48,49. In related studies in other regions, soil carbon stocks increased by 13% and 16% in cropland abandoned for 15 and 35 years, respectively50. However, outcomes are highly dependent on field conditions. For example, nitrogen deficiency in abandoned sites can significantly limit vegetation recovery and subsequent SOC accumulation51, while climate limitations in semi-arid areas like the Loess Plateau often necessitate a longer natural or assisted recovery time. Therefore, the duration of land abandonment, along with site-specific soil nutrient status and climatic factors, are crucial determinants influencing the dynamic changes in SOC following abandonment52. Therefore, ecological restoration of newly abandoned terraces should be carried out as soon as possible. After short-term abandonment, the terraced fields showed a special change pattern at different depths in this study. After short-term abandonment, the terraced fields showed a distinctive vertical pattern of SOC change. Surface SOC content decreased primarily due to reduced agricultural inputs such as fertilizers, while deeper soil layers (below 30 cm) showed some increase in SOC content. This deeper-layer increase may be attributable to the downward transport of labile soil organic matter from surface layers through leaching processes. This vertical redistribution mechanism becomes particularly important once the plant root-derived organic matter is depleted, as it represents one of the few pathways for carbon to reach deeper soil horizons in the absence of active root growth. Additionally, the death of crop roots following abandonment can temporarily contribute to deep soil carbon as these roots decompose in situ.

Effect of vegetation type and planting patterns on SOC in terraces

As demonstrated by Xin et al. (2016)53, planted forests significantly influence soil carbon dynamics through multiple mechanisms. Their study showed that forests reduce soil temperature, decrease soil moisture evaporation, and minimize soil erosion while increasing both the quantity and quality of organic matter inputs that compensate for carbon losses from previous crop cultivation. Vegetation types can influence SOC by modifying the soil’s physicochemical structure and altering both the input and decomposition rates of SOC40,54,55. Our data shows that there are significant differences in soil pH values under different vegetation types (Table 2). For instance, forested areas have higher pH values, while grasslands have lower pH values. This could be an important factor contributing to the differences in SOC content among various vegetation types, as pH levels influence the decomposition and stability of organic matter. Our study demonstrated that, compared to terraced fields, the SOC content of afforested land at a 0–100 cm depth was higher and that the forest litter biomass was more than that of farmland, which was the main reason for this difference. Planted forest land reduces soil temperature, soil moisture evaporation, and soil erosion while increasing the quantity and quality of organic matter input to compensate for carbon decomposition from crop cultivation51. The soil bulk density in forested areas is significantly lower than that in agricultural land, which is beneficial for the decomposition and accumulation of organic matter (Table 2). The afforested land is terraced forests, and the effect of preventing soil erosion is more significant. Some study shows that the SOC in immature forests (10 years old) is 17.91% higher than that in terraced cropland.

Due to the problem of ecological degradation and soil erosion, various ecological measures have been taken in the Loess Plateau area, such as returning farmland to forest and grass and planting trees22. Considering the climate and soil quality factors, the main species selected in the Loess Plateau region are drought-tolerant types of trees, and the carbon accumulation effect of different species selection also differs significantly38. P. tabuliformis has a higher SOC content than R. pseudoacacia, especially in the 0–50 cm soil layer. The conifer species selected in this region is Chinese red pine (Pinus tabuliformis Carr.), which contributes a large quantity of pine needles and cones to the soil during winter. This seasonal litter input increases the organic matter in the surface layer, resulting in higher SOC content in the pine forests’ surface soil (0–10 cm). Studies conducted in the Tibet region of China show that fir (Abies) forests have the highest carbon density (144.80 t ha⁻¹) among all forest vegetation types in this mountainous area56. Other studies have shown that tree species such as P. koraiensis, L. gmelinii, and P. tabuliformis increase soil organic carbon stocks more as silvicultural species22. The biomass of the herbaceous plants themselves is much lower than that of trees, and the limited amount of organic matter entering the soil, and the fact that M. sativa is mainly used as a source of fodder for the animals raised by farmers in the region, leads to a lower SOC content in terraces planted with M. sativa than in those undergoing afforestation.

The SOC content of natural grassland at a depth of 0–100 cm is lower than that of terraced farmland in our study area. This comparison refers specifically to natural grassland on slopes, not to agroforestry systems or orchards that combine trees with grasses. It’s important to note that grassland management practices significantly influence SOC dynamics. In our study region, grasslands are typically used for grazing. This management approach limits the return of organic matter to the soil. In contrast, terraced farmland areas, particularly those planted with apple trees (which should be classified as orchards), benefit from higher organic matter inputs as fallen leaves and pruned branches are often left to decompose on site. The lower pH value of the soil in grasslands may be a significant reason for its lower SOC content (Table 2). Grassland is a sloping land that has not been terraced, leading to slope erosion that removes a significant amount of organic matter from the soil surface. As a result, the SOC content in grassland is lower than in terraced fields (Fig. 2). The ecological advantages of sequestering SOC and enhancing soil fertility could be significant, largely thanks to the widespread implementation of reforestation and various land use strategies in terraced fields across China and numerous other mountainous areas globally22.

Crops may differ in their ability to increase SOC content due to differences in their photosynthetic capacity and root characteristics57. The pattern of intercropping in this area is typical of Agroforestry systems (AFS), where other crops are planted between the rows of apple trees. The SOC content of apple trees in combination with other crops was higher than in monocultures, especially in the lower and middle layers of the soil (30–100 cm). The amount of tree litter and root decomposition are important reasons for this57. The fallen leaves of fruit trees and decomposing fruits in the orchard are left in place, allowing these organic materials to incorporate into the soil and contribute to soil organic carbon pools. Additionally, belowground carbon inputs occur through the turnover of fine roots and the release of root exudates, which can contribute significantly to soil carbon sequestration in orchard systems58. For soils below 30 cm depth, tree roots produce an important role in the accumulation of soil organic carbon. When potato or legume crops are harvested, all the fruit and plant roots are removed and these lands will be tilled to grow other crops, so the input of organic matter is very limited. Agroforestry systems increase the distribution of roots in the soil and increase the recalcitrant compounds which slow the rate of mineralization through the input of organic matter.

Study limitations

While our study provides valuable insights into the effects of terracing on SOC dynamics, several limitations should be acknowledged. Our analyses are based on field data collected over a relatively short period, which may not capture long-term carbon accumulation processes. Due to the inherent complexity of field conditions, the number of soil profiles in some comparative analyses was not entirely consistent across all land use types, potentially introducing sampling bias. Additionally, we could not fully account for all factors known to influence SOC in terraced systems, such as fine-scale variations in root biomass, detailed fertilizer management histories, and specific tillage practices. To address sampling limitations, we incorporated high-resolution remote sensing data into our analyses. However, this approach cannot fully replace comprehensive field measurements, potentially affecting the representativeness of our results. Future research should expand the sampling frame, particularly for abandoned terraced fields, and collect a wider range of soil physical, chemical, and biological indicators to enable a more comprehensive assessment of the impacts of terracing and subsequent abandonment on SOC dynamics. Further work is also needed to develop practical guidelines for optimizing carbon storage in terraced systems while maintaining their economic viability and ecological functions in the Loess Plateau region.

Conclusions

The results showed that the SOC content in 0–100 cm of terraced fields planted with wheat was 1.5 times higher than that of sloping fields planted with wheat. Compared with sloping land, terrace construction significantly increased the SOC content of cultivated land, especially in the top soil layer (0–30 cm), and converting some sloping land into terraces would enhance the carbon sequestration capacity. Abandonment, vegetation type and planting structure affect the SOC of terraces. planting other crops between rows of apple trees can increase the SOC content. Since vegetation restoration takes a long time, short-term abandonment will lead to a decrease in terrace SOC, and some abandoned terraces can be planted with ecological restoration vegetation. Among the ecologically restored plant species, the vegetation with the highest SOC content is Pinus oleifera. The SOC content of terraces planted with artificial forage is lower than that of natural grassland, so it is necessary to protect the natural grassland left behind and choose tree species with better ecological benefits when planting trees. In the face of China’s huge food pressure and the goal of increasing carbon sinks to mitigate global climate change, terraces have significance and importance. Continuous strengthening of terraces management will give full play to their carbon sequestration role.

Funding.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, soil organic carbon data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Rossel, R. V. et al. Continental-scale soil carbon composition and vulnerability modulated by regional environmental controls. Nat. Geosci. 12 (7), 547–552. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0373-z (2019).

Guillaume, T., Bragazza, L., Levasseur, C., Libohova, Z. & Sinaj, S. Long-term soil organic carbon dynamics in temperate cropland-grassland systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.107184 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Temporal and Spatial variations in soil organic carbon sequestration following revegetation in the hilly loess plateau. China Catena. 99, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2012.07.003 (2012).

Jones, C. et al. Global climate change and soil carbon stocks; predictions from two contrasting models for the turnover of organic carbon in soil. Glob Chang. Biol. 11 (1), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00885.x (2005).

Doetterl, S., Six, J., Van Wesemael, B. & Van Oost, K. Carbon cycling in eroding landscapes: geomorphic controls on soil organic C pool composition and C stabilization. Glob Change Bio. 18 (7), 2218–2232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02680.x (2012).

Zhu, G. et al. Land-use changes lead to a decrease in carbon storage in arid region, China. Ecol. Ind. 127, 107770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107770 (2021).

Arnáez, J., Lana-Renault, N. & Lasanta, T. Effects of farming terraces on hydrological and Geomorphological process. Rev. Catena. 128, 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2015.01.021 (2015).

Tarolli, P., Preti, F. & Romano, N. Terraced landscapes: from an old best practice to a potential hazard for soil degradation due to land abandonment. Anthropocene 6, 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2014.03.002 (2014).

Wei, W. et al. Global synthesis of the classifications, distributions, benefits and issues of Terracing. Earth Sci. Rev. 159, 388–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.06.010 (2016).

Deng, L., Liu, G. & Shangguan, Z. Land-use conversion and changing soil carbon stocks in china’s ‘Grain-for-Green’ program: a synthesis. Glob Change Biol. 20 (11), 3544–3556. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12508 (2014).

Rong, G., Zhang, X., Wu, H., Ge, N. & Wei, X. Changes in soil organic carbon and nitrogen mineralization and their temperature sensitivity in response to afforestation across china’s loess plateau. Catena 202, 105226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2021.105226 (2021).

Sidle, R. C. et al. Erosion processes in steep terrain – truths, myths, and uncertainties related to forest management in Southeast Asia. Ecol. Manage. 224, 199–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2005.12.019 (2006).

Rong, G. et al. Dynamics of new-and old-soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Following Afforestation of Abandoned Cropland along Soil Clay Gradient319107505 (Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2021).

Aguilera, E., Lassaletta, L., Gattinger, A. & Gimeno, B. S. Managing soil carbon for climate change mitigation and adaptation in mediterranean cropping systems: a meta-analysis. Agr Ecosyst. Environ. 168, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.02.003 (2013).

Cai, A., Feng, W., Zhang, W. & Xu, M. Climate, soil texture, and soil types affect the contributions of fine-fraction-stabilized carbon to total soil organic carbon in different land uses across China. J. Environ. Manage. 172, 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.02.009 (2016).

Zhang, H., Wei, W., Chen, L. & Wang, L. Effects of Terracing on soil water and canopy transpiration of Chinese pine plantation in the loess plateau, China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Dis. 2016, 1–30 (2016).

Wang, Y., Fan, J., Cao, L. & Liang, Y. Infiltration and runoff generation under various cropping patterns in the red soil region of China. Land. Degrad. Dev. 27 (1), 83–91 (2016).

Wang, Q. et al. Agricultural activities increased soil organic carbon in Shiyang river basin, a typical inland river basin in China. Sci. Rep. 15, 11727. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90424-2 (2025).

Bellamy, P. H., Loveland, P. J., Bradley, R. I., Lark, R. M. & Kirk, G. J. D. Carbon losses from all soils across England and Wales 1978–2003. Nature 437, 245–248. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04038 (2008).

Heikkinen, J., Ketoja, E., Nuutinen, V. & Regina, K. Declining trend of carbon in Finnish cropland soils in 1974–2009. Glob Chang. Biol. 19, 1456–1469. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12137 (2013).

Rong, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal patterns and socio-economic drivers of land use and land cover changes in the Chinese loess plateau. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-021-08842-y (2021).

Hong, S., Yin, G., Piao, S., Dybzinski, R., Cong, N., Li, X., Chen, A. (2020). Divergent responses of soil organic carbon to afforestation. Nat. Sustain. 3(9), 694. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0557-y.

Smith, L. G. et al. Assessing the multidimensional elements of sustainability in European agroforestry systems. Agric. Syst. 197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103357 (2022).

Lorenz, K. & Lal, R. Soil organic carbon sequestration in agroforestry systems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 34 (2), 443–454 (2014).

Cardinael, R. et al. High organic inputs explain shallow and deep SOC storage in a long-term agroforestry system–combining experimental and modeling approaches. Biogeosciences 15 (1), 297–317 (2018).

Shi, L., Feng, W., Xu, J. & Kuzyakov, Y. Agroforestry systems: Meta-analysis of soil carbon stocks, sequestration processes, and future potentials. Land. Degrad. Dev. 29 (11), 3886–3897 (2018).

Nair, P. K. R., Kumar, B. M. & Nair, V. D. Agroforestry as a strategy for carbon sequestration. J. Plant. Nutr. Soil. Sci. 172, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200800030 (2009a).

Ran, Q., Chen, X., Hong, Y., Ye, S. & Gao, J. Impacts of Terracing on hydrological processes: a case study from the loess plateau of China. J. Hydrol. 588, 125045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125045 (2020).

Xu, Y., Zhu, G., Wan, Q., Yong, L., Ma, H., Sun, Z., Qiu, D. (2021). Effect of terrace construction on soil moisture in rain-fed farming area of Loess Plateau. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 37, 100889.

Shangguan, W., Dai, Y., Liu, B., Zhu, A., Duan, Q., Wu, L., Zhang, Y. (2013). A China data set of soil properties for land surface modeling. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, 5(2), 212–224.

Nelson, D. W. & Sommers, L. E. Total carbon, organic carbon and organic matter. In: (eds Page, A. L., Miller, R. H. & Keeney, D.) Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties. Agronomy Monograph, vol. 9. ASA and SSSA, Madison, WI, 539–579. (1982).

Nie, X. et al. Soil organic carbon fractions and stocks respond to restoration measures in degraded lands by water erosion. Environ. Manage. 59 (5), 816–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-016-0817-9 (2017).

Zhang, J. H., Wang, Y. & Li, F. C. Soil organic carbon and nitrogen losses due to soil erosion and cropping in a sloping terrace landscape. Soil. Res. 53 (1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR14151 (2015).

Green, J. K., Seneviratne, S. I., Berg, A. M., Findell, K. L., Hagemann, S., Lawrence,D. M., Gentine, P. (2019). Large influence of soil moisture on long-term terrestrial carbon uptake. Nature 565(7740), 476. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0848-x.

Post, W. M., Emanuel, W. R., Zinke, P. J. & Stangenberger, A. G. Soil carbon pools and world life zones. Nature 298 (5870), 156–159 (1982). https://www.nature.com/articles/298156a0

Gao, X., Meng, T. & Zhao, X. Variations of soil organic carbon following land use change on deep-loess Hillsopes in China. Land. Degrad. Dev. 28, 1902–1912. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2693 (2017).

Koga, N., Shimoda, S., Shirato, Y., Kusaba, T., Shima, T., Niimi, H., Atsumi, K.(2020). Assessing changes in soil carbon stocks after land use conversion from forest land to agricultural land in Japan. Geoderma 377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114487.

Li, Q., Li, A., Dai, T., Fan, Z., Luo, Y., Li, S., Wilson, J. P. (2020). Depth-dependent soil organic carbon dynamics of croplands across the Chengdu Plain of China from the 1980s to the 2010s. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26(7), 4134–4146. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15110.

Li, L., Yao, Y. F. & Qin, F. C. Distribution and affecting factors of soil organic carbon of terraced fields in chifeng, inner Mongolia. Chin. J. Ecol. 33 (11), 2930–2935. https://doi.org/10.13292/j.1000-4890.20141022.013 (2014).

Wiesmeier, M., Hübner, R., Spörlein, P., Geuß, U., Hangen, E., Reischl, A., Kögel-Knabner,I. (2014). Carbon sequestration potential of soils in southeast Germany derived from stable soil organic carbon saturation. Global change biology, 20(2), 653–665.

Lal, R. & Beyond COP 21: potential and challenges of the 4 per thousandinitiative. J. Soil. Water Conserv. 71, 20A–25A. https://doi.org/10.2489/jswc.71.1.20a (2016).

Davidson, E. A. & Janssens, I. A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440 (7081), 165–173 (2006).

Wiesmeier, M., Urbanski, L., Hobley, E., Lang, B., von Lützow, M., Marin-Spiotta,E., Kögel-Knabner, I. (2019). Soil organic carbon storage as a key function of soils-A review of drivers and indicators at various scales. Geoderma, 333, 149–162.

Nardi, S. et al. Soil organic matter mobilization by root exudates. Chemosphere 41 (5), 653–658 (2000).

Zhao, G., Mu, X., Wen, Z., Wang, F. & Gao, P. Soil erosion, conservation, and eco-environment changes in the loess plateau of China. Land. Degrad. Dev. 24 (5), 499–510 (2013).

Crawford, C. L., Yin, H., Radeloff, V. C. & Wilcove, D. S. Rural land abandonment is too ephemeral to provide major benefits for biodiversity and climate. Sci. Adv. 8 (21), eabm8999. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abm8999 (2022).

Poorter, L., Bongers, F., Aide, T. M., Almeyda Zambrano, A. M., Balvanera, P., Becknell,J. M., Rozendaal, D. (2016). Biomass resilience of Neotropical secondary forests.Nature, 530(7589), 211–214. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16512.

Djuma, H., Bruggeman, A., Zissimos, A., Christoforou, I., Eliades, M., Zoumides,C. (2020). The effect of agricultural abandonment and mountain terrace degradation on soil organic carbon in a Mediterranean landscape. CATENA, 195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104741.

Badalamenti, E., Battipaglia, G., Gristina, L., Novara, A., Ruhl, J., Sala, G., La Mantia, T. (2019). Carbon stock increases up to old growth forest along a secondary succession in Mediterranean island ecosystems. PLOS ONE, 14(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220194.

Novara, A., La Mantia, T., Ruehl, J., Badalucco, L., Kuzyakov, Y., Gristina, L.,Laudicina, V. A. (2014). Dynamics of soil organic carbon pools after agricultural abandonment. Geoderma 235, 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.07.015.

Jia, B., Liang, Y., Mou, X., Mao, H., Jia, L., Chen, J., Li, X. G. (2025). Soil mineral–associated organic carbon fraction maintains quantitatively but not biochemically after cropland abandonment. Soil and Tillage Research, 246, 106355.

Liu, M., Han, G. & Zhang, Q. Effects of agricultural abandonment on soil aggregation, soil organic carbon storage and stabilization: results from observation in a small karst catchment, Southwest China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 288, 106719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.106719 (2020).

Du, J., Liu, K., Huang, J., Han, T., Zhang, L., Anthonio, C. K., Zhang, H. (2022).Organic carbon distribution and soil aggregate stability in response to long-term phosphorus addition in different land-use types.Soil Tillage Res. 215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2021.105195.

Wan, Q. et al. Influence of vegetation coverage and climate environment on soil organic carbon in the Qilian mountains. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 17623. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-019-53837-4 (2019).

Xin, Z. B., Qin, Y. B. &, X. X. Spatial variability in soil organic carbon and its influencing factors in a hilly watershed of the loess plateau, China. CATENA 2016 (137(-)), 660–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2015.01.028 (2016).

Jia, L. Y., Wang, G. X., Luo, J., Ran, F., Li, W., Zhou, J., Yang, Y. (2021). Carbon storage of the forest and its spatial pattern in Tibet, China. Journal of Mountain Science, 18(7), 1748–1761.

Wegener, F., Beyschlag, W. & Werner, C. Dynamic carbon allocation into source and sink tissues determine within-plant differences in carbon isotope ratios. Funct. Plant Biol. 42 (7), 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP14152 (2015).

Godbold, D. L., Hoosbeek, M. R., Lukac, M., Cotrufo, M. F., Janssens, I. A., Ceulemans,R., Peressotti, A. (2006). Mycorrhizal hyphal turnover as a dominant process for carbon input into soil organic matter. Plant and Soil, 281(1), 15–24.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42371040), Key Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province(23JRRA698), Key Research and Development Program of Gansu Province (22YF7NA122), Cultivation Program of Major key projects of Northwest Normal University (NWNU-LKZD-202302), Oasis Scientific Research achievements Breakthrough Action Plan Project of Northwest normal University (NWNU-LZKX-202303).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guofeng Zhu and Qinqin Wang conceived the idea of the study; Siyu Lu and Ling Zhao analyzed the data; Dongdong Qiu, Longhu Chen and Rui Li were responsible for field sampling; Qinqin Wang and Yuanxiao Xu participated in the experiment; Yinying Jiao, Gaojia Meng and Jiangwei Yang participated in the drawing; Qinqin Wang wrote the paper; Yuhao Wang and Enwei Huang checked and edited language. All authors discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Xu, Y., Zhu, G. et al. Terraced fields increased soil organic carbon content in croplands of the loess plateau. Sci Rep 15, 36020 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19872-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19872-0