Abstract

We evaluated the effectiveness of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based subregional texture analysis (TA) models for classifying knee osteoarthritis (OA) severity grades by compartment. We identified 122 MR images of 121 patients with knee OA (mild-to-severe OA equivalent to Kellgren–Lawrence grades 2–4), comprising sagittal proton density-weighted imaging and axial fat-suppressed proton density-weighted imaging. The data were divided into OA severity groups by medial, lateral, and articulation between the patella and femoral trochlea (P-FT) compartments (three groups for the medial compartment and two for the lateral and P-FT compartments). After extracting 93 texture features and dimension reduction for each compartment and imaging, models were created using linear discriminant analysis, support vector machine with linear, radial basis function, sigmoid kernels, and random forest classifiers. Models underwent 100-time repeat nested cross validations. We applied our classification model to total knee OA severity. The models’ performance was modest for both compartments and total knee. The medial compartment showed better results than the lateral and patellofemoral compartments. Our MRI-based compartmental TA model can potentially differentiate between subregional OA severity grades. Further studies are needed to assess the feasibility of our subregional TA method and machine learning algorithms for classifying OA severity by compartment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a prevalent degenerative articular disease that causes joint pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility1. The knee is among the most frequently affected joints by OA. The prevalence of OA increases with age and is considered to be a result of progressive wear and tear2. There are several different knee OA patterns. The most common and important types of OA are the medial and lateral compartmental types. The two compartments have different disease patterns, which is also a determinant of treatment options, such as unicompartmental surgery or total replacement. Patients with severe patellofemoral patterns require a patellofemoral arthroplasty. The site-specific severity of OA is important because it provides insights into the disease mechanism and has implications for prevention and treatment strategies.

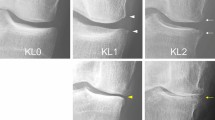

The pathogenesis of OA has been extensively studied with an emphasis has been mainly placed on articular cartilage degeneration. However, OA has been demonstrated to be a whole-joint disease that progressively affects articular cartilage, followed by the subchondral bone and periarticular structures3. Changes in subchondral bone are associated with OA4,5. Although plain radiography remains the mainstay of OA imaging, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful for early assessment of OA and plays a multipotent role in surveying bone and surrounding tissue abnormalities6,7. Currently, OA severity is assessed using grading systems, such as the radiographic Kellgren–Lawrence (K-L) grade8 and the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS)9. Although these scales offer a direct and intuitive interpretation of the disease, they are often criticized for their low precision and high interobserver variability. Furthermore, the K-L grading system is insensitive to early cartilage degeneration and projection bias. Additionally, the MOAKS system has the disadvantages of observer variability and inability to quantify the subchondral bone microstructure.

Texture analysis (TA) is an emerging technique that permits the quantification of image characteristics based on the distribution of pixels and their surface intensity or patterns10,11. It can generate phenotypic features related to the pathogenesis of diseases that are imperceptible to the human eye. TA can potentially improve clinical diagnosis and decision-making, opening up greater opportunities for developing new image-based diagnostic biomarkers12. TA has been applied to several medical imaging analyses, including oncological imaging13, neuroimaging14, and musculoskeletal imaging15. In knee OA, TA may capture the complexity of the trabecular bone and extract features related to subvisual degeneration associated with early OA16,17,18. These changes are believed to occur before visible or morphological changes become more apparent. Therefore, TA is more effective than histogram metrics and shape features for detecting degeneration in early OA. Several researchers have studied radiographic TA of the bone structure and demonstrated that structural or density alterations in the subchondral bone are associated with the onset and progression of OA16,17,18. However, few studies have used MRI-based TA to investigate bone abnormalities in patients with OA. Previous studies have shown that MRI-based TA significantly correlates with subchondral bone histomorphometry and is useful for identifying knee OA19,20. However, many prior studies have primarily focused on whole-knee OA rather than subregional compartmental differences (i.e., the medial, lateral, and patellofemoral compartments). Given the importance of site-specific evaluation and the management of knee OA, TA models based on these subregions are advantageous for clinical use.

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to develop MRI-based subregional TA models to classify knee OA severity by compartment.

Results

Dimension reduction of texture features (TFs)

All TFs showed good reproducibility in the interobserver reproducibility analysis. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) values are summarized in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Subsequently, a subset of TFs were selected for each knee compartment and imaging sequence using the sequential feature selection (SFS) algorithm, along with a collinearity analysis. The features selected for each classification attempt are listed in Supplementary Table S3. The collinearity status of the TFs in each imaging modality is shown in Supplementary Figures S1–12.

Classification model for OA severity of each knee compartment

Our MRI-based TA models performed moderately well in all the classification attempts. The overall accuracies were similar for each machine learning classifier. The results for each classifier are summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for all classification attempts are shown in Supplementary Figures S13–17. Among the knee compartments, the medial compartment showed better results than the lateral and articulation between patella and femoral trochlea (P-FT) compartments.

Classification model for OA severity of total knee

The selected TFs and the results of all classification attempts are summarized in Supplementary Table S4. The results for each classifier are summarized in Tables 6, 7, 8 and 9, and 10. The ROC curves for all the classification attempts are shown in Supplementary Figure S18. The best classification performance was observed for the proton density-weighted imaging (PDWI) using the Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier with a linear kernel, with an accuracy of 0.815 and a macro-average area under the curve (AUC) of 0.841.

Discussion

In the present study, we used MRI-based TA to target the subchondral bone in specific epiphyseal subregions and investigated whether our TA models could classify knee OA severity by compartment. Our results showed that our model is a modest predictor of OA severity by compartment type. We also found that the medial compartment showed better results than the lateral and P-FT compartments. Furthermore, we examined the classification of OA severity in the total knee using subregional TFs, which afforded moderate diagnostic performance. Several attempts have been made to differentiate OA severity groups using MRI-based TA20,21,22. Most of these studies considered the classification of OA for the entire knee. However, Hirvasniemi et al.20 evaluated the medial and lateral compartments of the tibial subchondral bone and suggested the feasibility of subregional TFs for OA severity classification. In clinical practice, it would be valuable to consider subregional models for OA severity classification. According to recent MRI-based knee OA scoring systems such as MOAKS9, OA severity is assessed on a compartmental basis. This idea is based on the fact that OA severity differs in each compartment, and the goal is to determine the best treatment for each compartment according to its severity. Therefore, developing subregional classification models such as ours may be worthwhile.

Xue et al.21 examined the MRI-based TA of the subchondral bones for knee OA severity and achieved an excellent classification performance with an accuracy of 0.920 and an AUC of 0.961 for distinguishing between normal and OA knees. They also reported accuracies of 0.964, 0.984, and 0.898, and AUCs of 0.995, 0.997, and 0.919 for discriminating between mild and severe OA, normal and severe OA, and normal and mild OA, respectively21. Because our model contains a multiclass classification, it is difficult to compare the two studies. However, compared to previous results21, the classification results of our models were inferior and modest. One possible reason for this is that Xue et al.21 used a sagittal 3D balanced fast-field echo sequence, which is ideal for precise imaging of the trabecular bone. Only 2D sequences were available for our study, which may have contributed to the unsatisfactory results. Another reason is that we used only the original TFs to avoid overfitting, whereas they used both the original TFs and TFs with Laplacian Gaussian filtering21. Hirvasniemi et al.20 also performed an MRI-based radiomic analysis of the subchondral bones to diagnose knee OA. They evaluated a larger study and obtained an AUC of 0.80 for distinguishing between knees with and without OA. Other studies have reported similar performance levels22,23, and our study may be consistent with these results.

Our study used FS-PDWI and PDWI to build TA models. However, in this study, FS-PDWI (axial image) and PDWI (sagittal image) were acquired in the orthogonal planes. Because TFs are plane-sensitive, cross-sequence comparisons are invalid. Both sequences are frequently used in routine MRI for articular diseases. Retrospectively, non-fat saturated PDWI has been preferred in related studies since it can efficiently detect the structural changes of trabecular bone associated with OA severity. Compared with PDWI, FS-PDWI can detect bone marrow edema-like lesions and cystic changes. Bone marrow edema-like lesions are related to cartilage injury and are important diagnostic indicators for predicting the occurrence and development of OA24,25. Li et al.22 examined the FS-PDWI-based TA for diagnosing knee OA and demonstrated an effective model with an AUC of 0.841. They argued that a TA model based on bone marrow edema may potentially diagnose OA at an early stage22.

This study examined the possibility of using subregional TA models to classify OA severity. Our results showed that the TA model of the medial compartment performed better than that of the other subregions. We speculate that this difference may be related to the frequency and severity of subregional knee OA. The medial compartment is most likely involved in knee OA26. The medial compartment bears approximately 60–80% of the knee’s load during walking27, making it more susceptible to OA than other compartments. The severity of OA in the medial compartment can differ from mild to severe. Therefore, we divided the severity groups into three for the medial compartment, whereas two groups for the lateral and P-FT compartments. In this study, the TA models of the lateral and P-FT compartments showed worse results than the medial compartment model. OA tends to be mild in the lateral and P-FT compartments and distinguishing between normal and mild OA may be difficult in these compartments. A previous study showed that the TA model was slightly inferior in distinguishing normal OA from mild OA compared with mild and severe OA21. Therefore, it is hypothesized that these factors make it difficult to classify the severity of OA in the lateral and P-FT compartments.

In our TA model, first-order features, such as the mean, minimum, maximum, 10th and 90th percentiles, kurtosis, and total energy, were selected, indicating that these primary statistics play a role in distinguishing OA severity. A previous study showed that a lower mean gray value in the subchondral bone is associated with OA28. Histologically, a higher bone volume fraction and thicker trabeculae are correlated with subchondral sclerosis in OA. The areas of sclerosis appear as areas of low signal intensity on MRI and thus have a lower mean gray value28. Higher-order features are also important in our TA model and have been suggested to reflect underlying pathomorphological texture patterns29,30. These features can provide additional information on the spatial organization of the subchondral bone and contribute to early structural alterations in OA subchondral remodeling before severe cartilage loss occurs. In a previous study, higher gray level variance was observed in the osteoarthritic subchondral bone, indicating greater heterogeneity28. Gray level run-length matrix (GLRLM) (gray level nonuniformity, run length nonuniformity, etc.) and GLCM (entropy, etc.) parameters are also important, indicating spatial disorganization within the image28. These parameters were also selected for our TA models, suggesting the importance of discriminating osteoarthritic bone changes.

Our results also demonstrate the usefulness of several machine learning classifiers. linear discriminant analysis (LDA) is the simplest algorithm and does not require long calculation times. However, the random forest (RF) algorithm is more complex and requires more time to produce results compared to the other algorithms. SVM are highly versatile because they can select several intrinsic kernels31. In our study, each machine learning algorithm produced similar results, and the stability of the features did not vary significantly across classifiers. LDA appeared to be the best-performing classifier when considering both accuracy and computation time. However, in terms of clinical applicability, RF typically performs better with larger datasets, suggesting that increasing the number of participants could enhance RF performance. For SVM, the radial basis function (RBF) kernel may be well-suited to our models. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that the RBF kernel outperforms other SVM kernels in predicting OA21.

There is increasing evidence that the uni- or bicompartmental pattern of knee OA is more common than the tricompartmental disease26. This contrasts with the lower frequency of partial or combined knee arthroplasty compared with total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Currently, the vast majority (~ 90%) of patients with OA undergo TKA, but only a quarter of these patients have tricompartmental disease26; therefore, a potentially large number of patients are overtreated with TKA. Single-compartmental diseases can be treated with partial knee arthroplasty (PKA), and there is increasing interest in combining PKA implants to treat bicompartmental diseases. Compared to TKA, PKA has the advantages of fewer perioperative complications, lower costs, and improved postoperative function32,33,34,35. Hence, it is clinically valuable to individually consider the severity of OA in each compartment to achieve the optimal treatment (e.g., TKA, PKA, or without surgery). Our method can be used to individually identify OA in subregions and is a promising means to facilitate treatment selection. If the OA severity of each subregion can be automatically and appropriately classified, the choice of treatment can be made smoothly and without errors.

The present study has some limitations. The sample size of this study was not sufficiently large to perform adequate statistical evaluations. The sample size calculation was based on the study by Rajput et al.37, which dealt with general machine learning guidance. It provides no guidance for radiomics analysis and is therefore inadequate for the sample size calculations in our study. In addition, as we focused on classifying OA severity, our cohort included patients with knee OA with K-L grades 2–4. We should examine the entire spectrum of the OA and normal groups and ideally classify them according to their OA severity grade. Furthermore, we evaluated only the subchondral bone and could not evaluate the cartilage or other structures. Additional evaluation of these structures may allow for a more accurate classification of OA severity. Image resampling was performed with a pixel size of 0.4 × 0.4 mm² per slice. This spatial resolution is not high enough to analyze bone microstructure, considering that the trabecular bone structure typically measures around 100–150 micrometers36. In addition, for knee MRI at our institution, T1-weighted imaging is not always performed, and PDWI scans are routinely performed. This was not favorable for the present study because T1-weighted images are superior to PDWI for assessing bone structure. At the same time, we used FS-PDWI in the axial plane and PDWI in the sagittal plane because these are routine sequences for knee MRI at our institution. Because the TFs are plane-sensitive, we could not compare these two sequences. These issues need to be addressed in future studies.

In conclusion, the efficacy of MRI-based compartmental TA models in classifying the severity of subregional knee OA was assessed. The overall performance of the proposed model is modest. The medial compartment showed better results than the lateral and P-FT compartments. We also found that our classification model could be applied to the OA severity of the total knee. Further studies are required to assess the feasibility of our subregional TA methods and machine learning algorithms for predicting OA severity.

Methods

Participants and image acquisitions

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Saitama Medical University Hospital (approval number 2023-085). The requirement for informed consent to participate was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Saitama Medical University because of the retrospective study. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The sample size was determined by referring to a previous work37. In machine learning, studies with insufficient sample sizes tend to suffer from data overfitting, whereas an increment in sample size increases predictive accuracy but may not produce significant changes beyond a certain number of samples. In one study, the effect size and performance of several machine learning methods were examined to derive sample size criteria37. They showed that the relative change in accuracy was large for samples smaller than 120, while the change in accuracy was relatively small for all classifiers for samples larger than 120. This may indicate that a minimum sample size of 120 is essential for the stable performance of machine-learning models. Thus, the sample size for this study was set at approximately 120.

Figure 1 summarizes the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We identified and reviewed 192 MRI data points from 190 patients referred from the Department of Orthopedics of our hospital who underwent knee MRI between January 2017 and December 2019. The inclusion criteria included: (1) patients ≥ 40 years; (2) diagnosed with mild-to-severe knee OA (equivalent to K-L grades 2 to 4) and (3) routine MRI scanning with sagittal PDWI and axial fat-suppressed proton density density-weighted imaging (FS-PDWI) in our hospital. The exclusion criteria included: (1) lack of routine MRI sequence (n = 5); (2) insufficient clinical data (n = 1); (3) suspected OA (equivalent to K-L grade 1) (n = 21); (4) infectious arthritis (n = 4); (5) rheumatoid arthritis (n = 13); (6) immediately after trauma (n = 9); (7) postoperative status (n = 9); (8) severe artifacts (n = 5); and (9) presence of mass lesions on bone marrow (n = 3).

Therefore, 122 MRI images from 121 patients of OA femurs (sex ratio 41/81 [male/female]; age 66.3 ± 12.0 [mean ± standard deviation]; side ratio 62/60 [right/left], including both sides of the knees in one patient) were used in the study. These data were subsequently categorized into OA severity groups for each knee compartment: medial, lateral, and P-FT. The categorization of OA severity per compartment was based on the total MOAKS score (osteophytes, bone marrow, and articular cartilage lesions)9. The patients were divided into two groups according to the severity of OA in the lateral and P-FT compartments. For comparison, the data were divided into three groups for the medial compartment because OA severity varied from mild to severe. In addition, the total knee OA severity was classified into three groups according to the K-L grade (K-L grades 2–4). OA severity was categorized independently by two radiologists (the same radiologists who delineated the distal femur and proximal tibia), and a consensus was subsequently reached.

All MRI scans were performed using a 3.0-T system (Ingenia Elition; Philips Healthcare, Netherlands) with a vendor-specific 16-channel knee coil. The knee flexion angle of each participant was approximately 30°. Among routine knee MRI protocols, sagittal PDWI and axial FS-PDWI were used for subsequent analyses because these two sequences were performed in all patients. The specific implementation protocol is as follows: repetition time, 3000 ms; echo time, 30 ms; flip angle, 90°; slice thickness, 2.5 mm; spacing between slices, 2.8 mm; acquisition matrix, 512 × 341; number of averages, 1; field of view, 15.0 cm for sagittal PDWI; as well as repetition time, 2500 ms; echo time, 18 ms; flip angle, 90°; slice thickness, 3.0 mm; spacing between slices, 3.3 mm; acquisition matrix, 332 × 264; number of averages, 1; field of view, 15.0 cm for axial FS-PDWI.

Segmentation and texture feature extraction

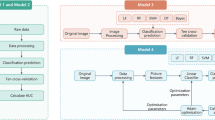

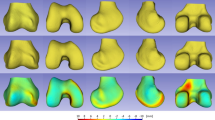

The workflow of this study is illustrated in Fig. 2. MR images were loaded into an open-source software (ITK-SNAP version 3.8.0) using the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format. Subsequently, the areas of the distal femur, proximal tibial epiphysis, and patella were manually delineated for each slice. Two radiologists with nine and eight years of experience, blinded to the clinical information, independently performed this delineation to assess interobserver reproducibility in the segmentation process. The delineated areas of the distal femur and proximal tibia were subsequently divided into medial, lateral, and P-FT regions by the plane along the edge of the facet, using another open-source software package (3D Slicer version 5.0.3). A schematic of the segmentation methodology is shown in Fig. 3. Subsequently, the medial and lateral regions of the distal femur and proximal tibia were used to analyze the medial and lateral compartments, respectively. The regions of the articulation between patella and femoral trochlea were used to analyze the P-FT compartment.

A visual schematic of the segmentation methodology. The areas of the distal femur, proximal tibia epiphysis, and patella are manually delineated for each slice. The delineated areas of the distal femur and proximal tibia are subsequently divided into three regions by the plane along the edge of the facet: medial, lateral and the articulation between patella and femoral trochlea. The areas of red, yellow, orange, blue, purple and light green correspond to lateral, trochlea and medial femur epiphysis, lateral and medial tibia epiphysis, and patella.

To reduce variability in the data, all MRI images were normalized by scaling their intensities to a 0–100 range and resampled to the same resolution prior to feature extraction. Image resampling was performed with a pixel size of 0.4 × 0.4 mm² per slice. We then computed TFs using an open-source software package capable of extracting a large panel of features from medical images (PyRadiomics version 2.1.0). The TFs were calculated based on six feature classes (first-order statistics, GLCM, gray level dependence matrix [GLDM], GLRLM, gray level size zone matrix [GLSZM], and neighboring gray-tone difference matrix [NGTDM]).

First-order statistics were computed using the pixel-value histogram of the image. The most significant advantage of these features is that they are easily obtained. The first-order statistical features were energy, kurtosis, 10th percentile, 90th percentile, entropy, robust mean absolute deviation, interquartile range, maximum, mean, mean absolute deviation, median, minimum, range, root mean square, skewness, total energy, variance, and uniformity.

The GLCM calculates the occurrence of pairs of pixels with a specific value in a specific direction. In this study, the GLCM was calculated using a two-dimensional symmetric approach. The distance was set to 1, considering pixels at a distance of 1 pixel from each other. The direction was divided into four angles: 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135°. This method can extract 24 statistical features: autocorrelation, cluster tendency, cluster shade, cluster prominence, contrast, correlation, difference variance, difference average, difference entropy, informational measure of correlation-1, informational measure of correlation-2, inverse variance, inverse difference normalized, inverse difference moment normalized, inverse difference moment, inverse difference moment, inverse difference moment, joint entropy, joint entropy, joint energy, maximal correlation coefficient, maximum probability, sum average, sum of squares, and sum entropy.

GLDM is a method for measuring the number of connected pixels within the distance of a center pixel. The distance between the center pixel and connected pixel was set to 1. The cutoff value for dependence is by default set to 0. This method can extract 14 statistical features: small dependence emphasis, large dependence emphasis, small dependence low gray level emphasis, gray level non-uniformity, dependence non-uniformity, low gray level emphasis, high gray level emphasis, dependence entropy, dependence non-uniformity normalized, gray level variance, dependence variance, large dependence high gray level emphasis, large dependence low gray level emphasis, and small dependence high gray level emphasis.

The GLRLM is a method for defining the length/number of consecutive pixels (runs) that have the same gray-level value along an angle in the image. By default, the value of a feature was calculated separately in the GLRLM for each angle, after which the mean of these values was returned. This matrix can extract 16 statistical features: gray level non-uniformity, gray level non-uniformity normalized, low gray level run emphasis, short run emphasis, long run low gray level emphasis, long run high gray level emphasis, gray level variance, high gray level run emphasis, long run emphasis, run entropy, run length non-uniformity, run length non-uniformity normalized, run percentage, run variance, short run low gray level emphasis, and short run high gray level emphasis.

The GLSZM is used to quantify several pixels whose values have the same gray level (zone). This method can extract 16 features: gray level non-uniformity, gray level non-uniformity normalized, zone%, gray level variance, low gray level zone emphasis, size zone non-uniformity, size zone non-uniformity normalized, high gray level zone emphasis, large area high gray level emphasis, large area low gray level emphasis, small area high gray level emphasis, small area high gray level emphasis, small area high gray level emphasis, small area low gray level emphasis, small area low gray level emphasis, small area low gray level emphasis, zone entropy, zone variance, and small area emphasis.

The NGTDM quantifies the difference between the gray value and the average gray value of its neighbors within a distance. The distance was set to 1 by default. This method extracts five statistical features: business, coarseness, complexity, contrast, and strength.

A total of 93 TFs were extracted and analyzed to select the most valuable features for discriminating OA grades using each compartment and imaging method. Textural features were computed on a slice-by-slice basis and then averaged.

Dimension reduction of TFs

Dimension reduction of the TFs was initially performed to avoid overfitting and generalization errors in the classification models. After normalizing the numeric values as z-scores, the ICC was calculated to evaluate the interobserver reproducibility. TFs with poor reproducibility (ICC < 0.75 or lower 95% confidence interval [CI] < 0.6) were excluded. Feature selection was performed using a SFS algorithm, a wrapper-based greedy search algorithm, and collinearity analysis. The SFS algorithm identifies feature subsets that maximize the performance of predictive models by incrementally adding or removing features based on a user-defined classification algorithm. A collinearity analysis was conducted using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Threshold for collinearity was r = 0.6. Features with high collinearity were excluded from analysis. In the case of a feature pair with a high collinearity, the pair with the lowest collinearity with the other features and a high preference for the SFS algorithm remained in the analysis. Our feature-selection algorithm can determine the optimal set of parameters that yields the most favorable performance. We considered three representative classification algorithms: LDA, SVM, and RF. In the SVM algorithm, several kernel functions provide different decisions and versatility. We adopted three kernels and separately evaluated their performances: linear, RBF, and sigmoid kernels. Therefore, five classifiers were tested: LDA, SVM with a linear kernel, RBF, sigmoid kernel, and RF. The subset of features that provided the best classification accuracy was selected using the SFS algorithm.

Classification model for OA severity of each knee compartment

Classification models were created for each knee compartment and imaging sequence. To build the classification model for each compartment, selected TF subsets of the corresponding compartment were used (e.g., for the medial section, TF subsets derived from the medial compartment of the distal femur and proximal tibia were used). Simultaneously, models were constructed using the two imaging methods (sagittal PDWI and axial FS-PDWI) and their combination. All models were developed using LDA, SVM with linear, RBF, and sigmoid kernels, and RF classifiers separately and were validated using a ten-fold cross-validation method with 100 repetitions to ensure the stability and reproducibility of our results. The performance of the classifiers was evaluated using ROC analysis and the AUC. Accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F-measure (macro-average values in multiclass classification) were calculated based on the confusion matrix of the classification results.

Classification model for OA severity of total knee

Furthermore, the performance of the classification model for total knee OA severity was evaluated. The SFS algorithm, along with collinearity analysis, was used for feature selection, and TFs were selected from all compartments and imaging methods. Classification models were created using LDA, SVM with linear, RBF, and sigmoid kernels, and RF classifiers, and the performance was evaluated by ROC analysis using the ten-fold cross-validation method with 100 repetitions.

Statistical analyses were performed using the open-source software package (Python scikit-learn 0.22.1). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

- FS-PDWI:

-

Fat-suppressed proton density density-weighted imaging

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- K–L grade:

-

Kellgren–Lawrence grade

- LDA:

-

Linear discriminant analysis

- MOAKS:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging osteoarthritis knee score

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- PDWI:

-

Proton density-weighted imaging

- P-FT:

-

Articulation between the patella and femoral trochlea

- RF:

-

Random forest

- SFS:

-

Sequential feature selection

- SVM:

-

Support vector machine

- TA:

-

Texture analysis

- TF:

-

Texture feature

References

Hawker, G. A. Osteoarthritis is a serious disease. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 37 (5), 3–6 (2019).

Shane Anderson, A. & Loeser, R. F. Why is osteoarthritis an age-related disease? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 24, 15–26 (2010).

Weinans, H. Periarticular bone changes in osteoarthritis. HSS J. 8, 10–12 (2012).

Funck-Brentano, T. & Cohen-Solal, M. Subchondral bone and osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 27, 420–426 (2015).

Li, G. et al. Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: insight into risk factors and microstructural changes. Arthritis Res. Ther. 15, 223 (2013).

Braun, H. J. & Gold, G. E. Diagnosis of osteoarthritis: imaging. Bone 51, 278–288 (2012).

Roemer, F. W., Eckstein, F., Hayashi, D. & Guermazi, A. The role of imaging in osteoarthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 28, 31–60 (2014).

Kellgren, J. H. & Lawrence, J. S. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 16, 494–502 (1957).

Hunter, D. J. et al. Evolution of semi-quantitative whole joint assessment of knee OA: MOAKS (MRI osteoarthritis knee Score). Osteoarthr. Cartil. 19, 990–1002 (2011).

Gillies, R. J., Kinahan, P. E. & Hricak, H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology 278, 563–577 (2016).

Rizzo, S. et al. Radiomics: the facts and the challenges of image analysis. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2, 36 (2018).

Kumar, V. et al. Radiomics: the process and the challenges. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30, 1234–1248 (2012).

Nagawa, K. et al. Diagnostic utility of a conventional MRI-based analysis and texture analysis for discriminating between ovarian thecoma-fibroma groups and ovarian granulosa cell tumors. J. Ovarian Res. 15, 65 (2022).

Hainc, N., Stippich, C., Stieltjes, B., Leu, S. & Bink, A. Experimental texture analysis in glioblastoma: A methodological study. Invest. Radiol. 52, 367–373 (2017).

Nagawa, K. et al. Texture analysis of muscle MRI: machine learning-based classifications in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Sci. Rep. 11, 9821 (2021).

Woloszynski, T. et al. Prediction of progression of radiographic knee osteoarthritis using tibial trabecular bone texture. Arthritis Rheum. 64, 688–695 (2012).

Janvier, T. et al. Subchondral tibial bone texture analysis predicts knee osteoarthritis progression: data from the osteoarthritis initiative: tibial bone texture & knee OA progression. Osteoarth Cartil. 25, 259–266 (2017).

Almhdie-Imjabbar, A. et al. Trabecular bone texture analysis of conventional radiographs in the assessment of knee osteoarthritis: review and viewpoint. Arthritis Res. Ther. 23, 208 (2021).

MacKay, J. W. et al. Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: association between MRI texture analysis and histomorphometry. Osteoarth Cartil. 25, 700–707 (2016).

Hirvasniemi, J. et al. A machine learning approach to distinguish between knees without and with osteoarthritis using MRI-based radiomic features from tibial bone. Eur. Radiol. 31, 8513–8521 (2021).

Xue, Z. et al. Radiomics analysis using MR imaging of subchondral bone for identification of knee osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17, 414 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Radiomics analysis using magnetic resonance imaging of bone marrow edema for diagnosing knee osteoarthritis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 12, 1368188 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Nomogram model based on radiomics signatures and age to assist in the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Exp. Gerontol. 171, 112031 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Ultrastructural change of the subchondral bone increases the severity of cartilage damage in osteoporotic osteoarthritis of the knee in rabbits. Pathol. Res. Pract. 214, 38–43 (2018).

Kon, E. et al. Bone marrow lesions and subchondral bone pathology of the knee. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 24, 1797–1814 (2016).

Stoddart, J. C., Dandridge, O., Garner, A., Cobb, J. & van Arkel, R. J. The compartmental distribution of knee osteoarthritis - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 29, 445–455 (2021).

Jones, R. K. et al. A new approach to prevention of knee osteoarthritis: reducing medial load in the contralateral knee. J. Rheumatol. 40, 309–315 (2013).

MacKay, J. W. et al. Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: association between MRI texture analysis and histomorphometry. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 25, 700–707 (2017).

Fritz, B. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-based grading of cartilaginous bone tumors: added value of quantitative texture analysis. Invest. Radiol. 53, 663–672 (2018).

Muehlematter, U. J. et al. Vertebral body insufficiency fractures: detection of vertebrae at risk on standard CT images using texture analysis and machine learning. Eur. Radiol. 29, 2207–2217 (2019).

Hara, Y. et al. The utility of texture analysis of kidney MRI for evaluating renal dysfunction with multiclass classification model. Sci. Rep. 12, 14776 (2022).

Siman, H. et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty vs total knee arthroplasty for medial compartment arthritis in patients older than 75 years: comparable reoperation, revision, and complication rates. J. Arthroplasty. 32, 1792–1797 (2017).

Drager, J. et al. Shorter hospital stay and lower 30-day readmission after unicondylar knee arthroplasty compared to total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 31, 356–361 (2016).

Agarwal, A. et al. Comparison of gait kinematics in total and unicondylar knee replacement surgery. Ann. R Coll. Surg. Engl. 101, 391–398 (2019).

Kleeblad, L. J., van der List, J. P., Zuiderbaan, H. A. & Pearle, A. D. Larger range of motion and increased return to activity, but higher revision rates following unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty in patients under 65: a systematic review. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 26, 1811–1822 (2018).

Wehrli, F. W. Structural and functional assessment of trabecular and cortical bone by micro magnetic resonance imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 25, 390–409 (2007).

Rajput, D., Wang, W. J. & Chen, C. C. Evaluation of a decided sample size in machine learning applications. BMC Bioinform. 24, 48 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 23K14902).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception: Keita Nagawa, Yuki Hara and Saki Tsuchihashi.Design of the work: Keita Nagawa, Yuki Hara, Saki Tsuchihashi, Kaiji Inoue and Eito Kozawa.Patient acquisition: Naoki Sugita.Data analysis: Keita Nagawa, Yuki Hara, Shinji Kakemoto, Taira Shiratori, Akane Kaizu, Masahiro Koyama, and Saki Tsuchihashi.Data interpretation: Keita Nagawa, Yuki Hara, Saki Tsuchihashi and Hirokazu Shimizu.Drafted the work: Keita Nagawa and Yuki Hara.Substantively revised: Keita Nagawa, Yuki Hara, Kaiji Inoue and Eito Kozawa.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagawa, K., Hara, Y., Kakemoto, S. et al. Using magnetic resonance imaging-based subregional texture analysis models to classify knee osteoarthritis severity by compartment. Sci Rep 15, 36173 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19909-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19909-4