Abstract

This study proposes an environment- and signer-invariant sign language recognition model. The model first extracts skeletal key-points from the signer via MediaPipe, which is Google’s cross-platform pipeline framework that helps to detect and track human poses, facial landmarks, and hands. After preprocessing the skeletal key-point information, feature extraction and learning are performed via deep learning architectures: a convolutional neural network followed by long short-term memory (CNN-LSTM), long short-term memory (LSTM), bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM), and gated recurrent units (GRUs). This study proposes a deep learning framework for recognizing Ethiopian sign language (EthSL) via skeleton-based features extracted via the MediaPipe Holistic. A dataset of 5600 annotated sign videos was constructed and used to evaluate four deep learning models, namely, CNN-LSTM, LSTM, BiLSTM, and the GRU, which achieved 94% accuracy in signer-dependent settings and 73% accuracy in signer-independent settings. The results demonstrate the model’s potential for scalable, low-cost, and real-time EthSL recognition in unconstrained environments. This study attempted to increase the independence of ASLR models to some level. However, further studies are needed to identify continuous signs in a fully open environment. Therefore, the technique implemented to detect and track key points in this study should be further investigated to recognize continuous EthSL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite recent advances in sign language recognition, most existing EthSL systems are limited by their reliance on constrained environments and signer-dependent models. These limitations restrict the applicability of such systems in real-world, diverse contexts where lighting, background, and signer variations are inevitable. According to the World Federation of the Deaf, more than 70 million deaf individuals rely on sign languages globally. Ethiopian Sign Language, used by the Ethiopian deaf community, remains underrepresented in technological developments. Despite its formal recognition and use in education and media, few computational resources exist to support automatic EthSL interpretation1. Sign Language, a visual language that is used by the deaf community as a way of communication, is one of its types. It is a widespread system of communication around the world with at least 300 different Sign Languages in use around the world1. While some of these Sign Languages are legally recognized and further advanced to Sign Language poetry and other stage performances, some have no status at all2. Each Sign Language varies from nation to nation as the regional dialects vary. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2022), there are over 1.5 billion people around the world with hearing loss, and this number could rise to 2.5 billion by 2050. Sign Language is used by most deaf people and many hearing-abled people as a first or second language. Sign Language involves the use of manual signs and body language, also known as nonmanual signs, to fluidly convey the thoughts of a person3. Letters, words, and other symbols are expressed via manual signs, as shown in Fig. 1.

While manual communication is made through hand shapes, hand postures, hand locations, and hand movements, body language is expressed via head and body postures, facial expressions, and gaze and lip patterns. Nonmanual signs are very important in carrying grammatical and prosodic information. They are used to communicating questions, affirmations, denials, and emotions. Nonmanual signs also play significant roles in solving ambiguities and specifying expressions4. Even though there is a large hearing-impaired community, Sign Language is recognized by most hearing-impaired people and few hearing-abled people. This fact shows that there is a communication gap between the deaf community and the majority of the hearing community5. In recent years, this communication gap has been filled by human interpreters, who are few in number compared with demand. Some of the interpreters were vulnerable to physical and psychological disorders that forced them to reduce their working hours or quit their jobs. This made the job difficult and costly6. As a result, researchers have begun to look for ways to detect and recognize Sign Languages automatically. Sign Language comprises hand shapes, body postures, facial expressions, and gaze and lip patterns. Hence, automatic dynamic sign language recognition involves detecting dynamic movements of those manual and nonmanual signs. Researchers have been looking for approaches to accomplish recognition efficiently by focusing on one or more components of Sign Language7.

Research on automatic sign language has advanced from the traditional handcrafted approach to the recent and widely used deep learning approach8,9. Each newly introduced approach contributed to improvements in the extraction of features in terms of type, number, and ability to learn from features. In recent years, much success has been attained with the training of deep networks in a greedy layerwise fashion, in which deep network weights are learned one layer at a time in a phase referred to as pretraining10. Although current sign language recognition methods utilize deep neural networks widely to extract features and apply classification, some of them suffer overfitting due to limited and noisy data11. This challenge occurs most often in underresourced Sign Languages such as Ethiopian Sign Language because of the availability of limited public datasets of signs.

Research on automatic sign language recognition is also limited by the dynamic behavior of sign language, motion blur, complex backgrounds, variable external illumination, and shadows from hand gestures12,13. Similar gestures that have different meanings because of variations in the direction of movement and similar signs that are performed with different hands, speeds, localism, and body shapes are the other aspects that pose challenges. Furthermore, commercializing sign language recognition systems remains challenging because of their high cost14. For these reasons, automatic sign language recognition remains a challenging research topic15.

More than a few attempts have been made to recognize Ethiopian Sign Language, and as a result, some signs have been recognized at the letter, word, phrase, and sentence levels. Legesse Zerubabel16 studied the recognition of ten (10) Ethiopian finger spell signs. Their research involved recognizing static signs via neural networks with Harris-like features and neural networks with principal component analysis (PCA)-driven features, with an average recognition accuracy of 92.15%. However, the studied signs had very large hand shape variations that made them easier to differentiate. In another work, Eyob Gebretinsae17 focused on determining and selecting frames that have information related to movement directions for vowels. On the basis of the direction of movement, they classified 238 Ethiopian Sign Language alphabet letters. They used the center of mass for tracking hands and finite state automata to recognize alphabet letters and achieved a recognition accuracy of 90.76%. One of the reasons for the lower accuracy of scoring is the use of handcrafted features, which are not efficient enough. Tefera Gimbi18 studied the recognition of isolated signs from the Ethiopian Sign Language and the end-product of their work recognized signs with 86.9% and 83.5% recognition accuracies via machine learning algorithms for feature extraction and a hidden Markov model (HMM) for classification. Data for their work were collected within a controlled environment. Nigus Kefyalew19 compared the recognition performance of an artificial neural network (ANN) with that of a support vector machine (SVM) and reported that the SVM outperforms other methods in recognizing Ethiopian Sign Language alphabet letters. In this work, data were collected in a controlled environment, and features were extracted via machine learning algorithms. Walelign Andargie20 combined features from hand gestures and facial expressions to recognize Ethiopian Sign Language at the word level via data collected in a controlled environment. They used YCbCr skin detection for hand segmentation, multitask convolutional neural network (MTCNN) techniques for facial segmentation, a Gabor filter to extract texture features, and a convolutional neural network (CNN) for classification. Their model achieved an average recognition accuracy of 97.3%. Abey Bekele21 also used YCbCr skin detection for hand and face segmentation. Feature extraction and learning are performed through a CNN. The study involved Amharic alphabets, words, and numbers and attained an average accuracy of 96.81%.

In our observations, the aforementioned studies have two major gaps that contribute to a lowered performance if they are deployed for real-world utilization. First, however, recognition systems are expected to be deployed and utilized efficiently in dynamic environments where backgrounds are of various colors and signers are allowed to wear clothes of their choice under unconstrained lighting conditions22; the aforementioned models require uniform backgrounds (either entirely white or entirely black), constrained clothing and controlled lighting conditions to be recognized efficiently. Second, these models are trained using a few samples that are split randomly into training and testing sample sets. This splitting increases the chance of signs from the same signer being found in both the training and testing sets. In addition, the number of signers in their constructed datasets was small. As a result, the models became vulnerable to capturing the characteristics of individuals, such as skin tone, fluency, size, dominant hands, and speed, which led to significant levels of bias in the models that resulted in signer-dependence behavior. Sign Language recognition systems must learn not only the variations of a given sign but also the variations between signers to be signer invariant or signer independent23,24. On the basis of the above descriptions of the gaps that exist in Ethiopian Sign Language Recognition, this study aims to design and develop a skeleton-aware Ethiopian Sign Language recognition model via a deep learning approach.

This research is organized into a five-section document. Once an introduction of the work is given in the first section, a thorough related work is presented in the second section. The third section presents the methodology implemented to carry out this study. The general research design, evaluation mechanism, and data collection procedure are explained. The fourth section presents the experimental results followed by a discussion. Comparisons of the proposed model with other related methods are presented in detail. The final section concludes the findings of this study and highlights future works to be covered.

Related works

Beena and Namboodiri25 proposed a system that uses a CNN architecture from Kinect depth images for sign language recognition. The system trained CNNs for the classification of 24 alphabets and 0–9 numbers using 33,000 images. The system trained the classifier with different parameter configurations and attained an efficiency of 94.68%. However, the Kinect captures a high-quality depth image, and it requires extra expenses to purchase it for real-world utilization. Hence, the use of less expensive embedded devices such as webcams and the extraction of depth information from captured images are recommended.

Shahriar et al.26 presented an automatic human skin segmentation algorithm based on color information. In this work, the YCbCr color space was employed. A skin-color distribution was modeled as a bivariate normal distribution in the CbCr plane. Then, a convolutional neural network (CNN) is used to extract features from the images, and the deep learning method is used to train a classifier to recognize Sign Language. An accuracy of 94.7% was achieved for real-time American Sign Language recognition. This work is limited to classifying only four classes that do not show the optimal performance of the model; including more classes can help the model capture more distinctive patterns, which in turn improves the reliability.

Abraham, Nayak, and Iqbal27 presented the translation of static and dynamic signs of the Indian Sign Language to speech. A sensor glove was used to collect data about the gestures. The sensor had a flex sensor to detect the bending of each finger and an IMU to read the orientation of the hand. LSTM networks were implemented for the classification of 26 gestures with an accuracy of 98%. However, the sensor glove is portable, so commercializing the recognition system might be uneconomical since systems are required to be cost effective. Therefore, it is wise to focus on vision-based recognition.

Cui, Liu, and Zhang28 adopted a deep convolutional neural network with stacked temporal fusion layers as the feature extraction module and bidirectional recurrent neural networks as the sequence learning module. An iterative optimization process was also proposed for the architecture to fully exploit the representation capability of deep neural networks with limited data. In this process, an end-to-end recognition model was trained for an alignment proposal. The alignment proposal is then used as strong supervisory information to directly tune the feature extraction module. This process was run iteratively to achieve improvements in recognition performance. The authors of this paper claimed that their system outperformed the state-of-the-art system by a relative improvement of more than 15% on challenging Sign Language databases.

In the work of Bantupalli and Xie29, a custom Sign Language Dataset, which has different gestures performed multiple times with different contexts and common frame rates, was used for video data for training the model to recognize gestures. Inception, a CNN model, is used to extract spatial features from the video stream for sign language recognition. LSTM is used to extract temporal features from video sequences. The model achieved accuracies of 90% − 93% with the SoftMax layer and 55% − 58% with the pool layer for various numbers of samples. However, the model is not reliable in dynamic environments since the dataset is collected in a controlled environment. The same architecture with a modified mechanism is recommended for recognition in a dynamic environment since the architecture used works well for spatiotemporal input.

Ibrahim, Selim, and Zayed30 used a dynamic skin detector based on facial color for hand segmentation. A skin-blob tracking technique was used to identify and track hands. Geometric features of the spatial domain were used to extract hand features. Finally, the Euclidean distance was used for classification because the authors used a small amount of data. This system had a recognition rate of 97% for isolated Arabic Sign Language words in signer-independent mode.

Mujahid et al.31 proposed a lightweight model based on YOLOv3 and DarkNet-53 convolutional neural networks for gesture recognition without additional preprocessing, image filtering, or image enhancement. The proposed model was evaluated on a labeled dataset of hand gestures in both the Pascal VOC and YOLO formats. This work achieves 97.68% accuracy, 94.88% precision, 98.66% recall, and an F-1 score of 96.70%.

Al-Hammadi et al.32 proposed learning region-based spatiotemporal properties of hand movements via a 3-dimensional convolutional neural network (3DCNN). The performance was further enhanced by employing fusion techniques to globalize the local features learned by the 3DCNN model. The method achieved recognition rates of 98.12%, 100%, and 76.67% on three color video gesture datasets. Despite these promising results, 3DCNN modeling struggles to capture the long-term temporal dependencies of hand gesture signals. This limitation can be addressed by modeling the local spatiotemporal properties of multiple temporal segments via separate instances of the 3DCNN.

Wadhawan and Kumar33 developed a sign language recognition system capable of identifying static signs via convolutional neural networks (CNNs) that are based on deep learning techniques. A dataset comprising 35,000 images of 100 static signs was collected from various users for this study. To evaluate the system’s effectiveness, approximately 50 CNN models were tested, varying parameters such as the number of layers and filters. The highest training and validation accuracies achieved were 99.17% and 98.80%, respectively. Among the optimizers tested, stochastic gradient descent (SGD) outperformed Adam and RMSProp, achieving training and validation accuracies of 99.90% and 98.70%, respectively, on the grayscale image dataset. The proposed system demonstrates robust performance and was thoroughly tested via multiple optimization techniques.

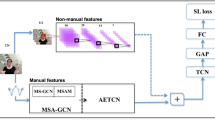

Jiang et al.11 proposed a skeleton-aware multimodal framework designed to train and fuse multimodal feature representations, thereby increasing recognition accuracy. The model employs a separable spatial‒temporal convolution network (SSTCN) to leverage skeleton features and a sign language graph convolution network (SL-GCN) to capture the embedded dynamics of skeleton key points. The experimental results demonstrated that the proposed late-fusion GEM significantly reduces the effort required for tuning optimal parameters, delivers substantially better performance than a basic ensemble approach, and effectively learns the multimodal ensemble. Additionally, the inclusion of other modalities further enhances the recognition rate.

Yigremachew & Endashaw34 incorporated sensor-based and vision-based approaches for real-time Ethiopian sign language in audio translation. They used a machine learning neural network single shot multibox detector (SSD) on TensorFlow to detect hand gestures for a vision-based approach and wearable sensor gloves for a sensor-based approach. Their work detected the signer’s face via OpenCV object detection with Haar-Cascade. Landmarks and poses of the hand recognition were performed via the ColorHandPose3D network. Seven gestures from a dataset constructed for this specific study were used for the study, and an average recognition accuracy of 88.56% was attained. However, the study produced encouraging outcomes and was limited to only static signs. Scaling up to dynamic signs requires additional study since vision-based methods are not robust enough.

The Ethiopian Sign Language Recognition Model was designed by Abey21 via a deep learning approach with the intention of including letters, words, and numbers in a single.

recognition system. In this work, 34 letters, 24 words, and 10 numbers were included in a dataset constructed for this specific study. The researcher used YCbCr skin color detection for hand and face detection, a Gabor filter for feature extraction, a convolutional neural network for feature learning, and SoftMax for the classification of gestures. An average recognition accuracy of 97% was attained. Although this study yielded better results, it is not robust enough in terms of being signer-invariant. The number of signers in the dataset is relatively small, which might result in a model that is biased on the color of the signers. Furthermore, data are collected from a camera that is fixed at a similar distance for all inputs. This, in turn, might make the model less robust in dynamic environments.

Jeylan35 used Microsoft Kinect to acquire information about RGB images, skeletal joint positions, and 3D depths from a signer. The researcher selected 7 out of 25 joint positions for manual sign feature extraction and stored them in a database; information about nonmanual signs was also stored in a database. A random forest algorithm is used to match gestures with those stored in the dictionary and later converted to Amharic text. The authors also proposed a language model that is used to translate continuous sign language to Amharic text. The model was evaluated at the word and sentence levels, with accuracies of 84.4% and 60%, respectively. Deep learning architectures can increase recognition performance.

Sign Language recognition for Amharic phrases was studied by Girma36. In this work, features were extracted via a convolutional neural network, and a long short-term memory network was used for classification. The model was trained with data collected in a controlled environment, and formal preprocessing steps were implemented. The work scored 96% recognition accuracy for 10 Amharic phrases. Although the results of this study are encouraging, the model is likely to be more dependent than the other models since it tends to capture signature-specific features. This problem can be solved through either increasing variations in signers or processing skeletal information independent of skin color.

Yigzaw, Meshesha, and Diriba37 investigated the performance of pretrained deep learning models in recognizing Ethiopian finger spelling. They used the LSTM network to extract sequence information and pretrained models to extract features from each frame of the input video. Their experiments revealed that both EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50 recognized Ethiopian finger spelling with 72.79% accuracy. Related works are summarized in Table 1.

Contribution of the study: As the main aim of this study is to identify a solution that enables signer and environment-invariant Ethiopian Sign Language recognition, its contribution involves delivering an efficient solution. First, the study indicated a way to acquire and extract skeletal information in real time. This technique can be utilized to recognize Sign Language in real time. In addition to offering simplified dataset preparation, the size of the dataset can also be decreased. For example, a 2-second video sample occupies 6.44 MB of space if captured as a video, but it can only take up to 480 KB of space if only skeletal information is collected and stored. The second contribution of this study is that it provides a way to recognize Ethiopian Sign Language without having to set up a controlled environment; the background can be of any kind, and signers can dress with no restrictions. Furthermore, signs from signers who were not in the training set can be recognized. The signer- and environment-invariant behavior of the classifier can be considered a basis for further studies and even more for commercializing sign language recognition products. Future studies can also use this study as a benchmark to evaluate their study outcomes.

We present a skeleton-based recognition framework tailored for Ethiopian Sign Language. Our main contributions include the development of a novel EthSL dataset comprising 5600 video samples collected under variable conditions; the use of skeleton-based multimodal features, including hands, poses, and faces; a comparative analysis of four deep learning architectures for isolated sign classification; and an evaluation in both signer-dependent and signer-independent scenarios to assess generalizability across individuals. Our main contributions include the following:

-

Novel skeleton-based EthSLR using the MediaPipe Holistic.

-

Construction of a real-world video dataset with 5,600 samples.

-

Signer-independent testing (first in EthSLR).

-

Real-time capable, low-memory pipeline.

Methodology of the study

The study followed an experimental research methodology with techniques and procedures to investigate the performance of selected deep learning algorithms in recognizing Ethiopian Sign Language. This section also describes how the study was conducted following common experimental principles such as comparison, reproduction, repetition, justification, and explanation, which are required38. A description of the data collection procedure and evaluation technique utilized is also given. After the gaps were identified, the solution was proposed, and the main objective of the study was defined. The main objective of this study was to identify the most efficient deep learning algorithm to accomplish skeleton-based Sign Language recognition for Ethiopian Sign Language.

Data preparation

Data collection was intentionally conducted under various conditions, including differences in lighting, background complexity, camera angle, and signing pace. This approach aims to simulate real-world usage scenarios and improve model robustness. The participants were also encouraged to sign naturally, without strict control over speed or expression, making the dataset more reflective of spontaneous communication. We understand the importance of constructing a dataset from videos collected in an environment that resembles the real-world setting. However, it is very challenging to obtain public datasets or construct a sufficient dataset for underrresource sign language. Hence, further work is required to fully capture the spontaneity, variability in signing speed, or changes in body orientation following the promising result attained by this study in recognizing signs in an open environment with a variety of signer characteristics. Since there is no publicly available dataset, a dataset was constructed for this specific study. This was one of the most challenging tasks in this study. Sample videos were collected from students in the Department of Special Needs and Inclusive Education at Haramaya University via a nonprobabilistic convenience sampling technique. The dataset used in this study consists of 5600 annotated videos collected from seven native signers across multiple environments. While the raw dataset cannot be publicly released owing to privacy and institutional restrictions, anonymized skeletal representations derived from MediaPipe Holistic can be shared upon request to ensure reproducibility. Although we have not benchmarked this exact architecture on an existing American Sign Language (ASL) corpus owing to linguistic differences and sign structure, the framework’s modular design allows easy adaptation to other datasets. This remains a promising direction for future validation on multilingual corpora. The technique was preferred because the students were the first available volunteers who could be reached easily. The participant pool consisted of seven native Ethiopian Sign Language users, with diverse demographic backgrounds, including four males and three females, aged between 20 and 28 years. Signers varied in terms of signing speed, handedness (including two left-handed participants), and body morphology. This diversity was intentionally incorporated into the dataset design to minimize demographic bias and enhance model generalizability across different user profiles. Seven students volunteered to be filmed, and fortunately, all of them were distinct in terms of size, fluency, and speed. In addition, 3 out of the 7 students were lefty; their left hand was their dominant hand. Among the 7 volunteers, 3 were females with different colors and sizes. A dataset constructed from a wide range of variations, such as different signers’ sizes, genders, and colors, ensures a model with higher accuracy. This diversity in the dataset enables the model to learn more distinctive patterns of signs instead of individual differences. Seven students volunteered to be filmed, and fortunately, all of them were distinct in terms of size, fluency, and speed. In addition, 3 out of the 7 students were lefty; their left hand was their dominant hand. Sample videos of the isolated signs were taken via both the laptop’s webcam and the mobile phone camera with 1280 × 720 and 4032 × 3024 camera resolutions, respectively. This was done intentionally to train the model with different video resolutions so that the model becomes resolution invariant. The isolated signs were selected with the help of Sign Language experts on the basis of the behaviors of the signs. The experts selected 20 words from varieties of categories, such as signs that involve only one hand, both hands, facial expressions, hand movements in different directions, and touching parts of the body, such as the head. The number of words is limited to 20 because the experts recommended that the words represent the variation in signs. Therefore, 40 × 7 = 280 sample videos per class were collected, and the total number of video samples was 40 × 20 × 7 = 5600. Each video sample contains 30 frames; therefore, the total number of frames becomes 5600 × 30 = 168,000. Each of the 20 selected signs was performed 40 times by each signer to ensure adequate variation in hand orientation, speed, and environmental context, enabling the model to learn more robust representations. The 30-frame sequence captures approximately 3 s of motion at a typical signing pace, balancing expressiveness and computational efficiency. Each signer repeated a single isolated sign forty (40) times at different angles of inclination, distances from the camera, and environments.

Ethics statement: This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional guidelines. Ethical approval was waived by the Institutional Research Ethics Review Committee of Haramaya University, as the study involved noninvasive procedures and collected no personal or sensitive data. Specifically, the data collection was limited to video recordings of sign language gestures, with no collection of identifiable or biometric information. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Implementation tools

Jupyter Notebook, a powerful scientific environment for Python, is used to build candidate models. It is a comprehensive development tool with scientific package data discovery, interactive execution, detailed inspection, and stunning visualization capabilities. It provides integration with numerous common scientific packages, including NumPy, SciPy, Pandas, IPython, QtConsole, Matplotlib, SymPy, etc.etc. The study implemented Keras and TensorFlow. TensorFlow is the deep learning framework that is the most common and strongest. It has a comprehensive flexible method, library, and community resource ecosystem. Keras is a Python-based, high-level neural network API that can run on top of TensorFlow, CNTK, or Theano. OpenCV, an image processing image and video processing library, is used to capture the input video, whereas numpy is used to store the list of key-points. Mediapipe, a cross-platform pipeline framework, is utilized to detect and track key points. In addition, Keras Tuner is used to find the optimal hyperparameters while building neural networks. All training and testing were conducted on a machine with an Intel Core i7 processor and 4 GB of RAM. On average, training each model required 2–3 h, with each epoch taking approximately 6 min, demonstrating the framework’s feasibility for low-resource environments. The inference speed was tested on a CPU-based setup with 4 GB of RAM and an Intel i7 processor. The average inference time for a 30-frame sequence was 1.2 s, equivalent to approximately 40 ms per frame, which satisfies real-time processing requirements. Model training scales linearly with data size, with full training requiring approximately 2.5 h. These performance metrics confirm the feasibility of deploying the model in real-world settings, including mobile or embedded platforms. To reduce the input dimensionality and computational load, we use preextracted spatiotemporal numerical representations of hand, face and body pose key points. The models used (e.g., GRU and CNN-LSTM) are lightweight and well suited for such structured inputs, contributing to faster convergence and low inference latency. The small input format and low model complexity imply that real-time deployment is possible, especially for isolated sign recognition tasks on resource-constrained devices, even when the precise inference time per sample is not evaluated.

Evaluation methods

In this stage, the developed model is evaluated to verify how well it fits to solve the identified problems. Different analysis techniques and measurement metrics can be used depending on the type of problem and artifact created. The performance of sign language recognition is measured via the following recommended frame-based metrics: true positive, true negative, false positive, false negative, and their combinations, such as accuracy, precision, recall rate, and F-measure39. A confusion matrix is a matrix composed of columns that represent the predicted class and rows that represent an actual class. It helps in analyzing where the model is confusing among classes. The model evaluation metrics are presented in Table 2.

Proposed architecture

This section presents the proposed architecture of the EthSLR model. The design comprises the major successive steps in automatic Sign Language recognition: video acquisition, preprocessing, segmentation, feature extraction, and classification. The tasks that are accomplished under each step as well as the methods and algorithms used are explained in detail. The proposed system architecture is constructed from the major steps of automatic Sign Language recognition. Each step involves certain tasks that contribute to the success of constructing the EthSLR model. Then, preprocessing is performed to convert the input video to a sequence of image frames. It also involves converting the color space of the image frames. Segmentation helps detect and extract human poses, faces, and hand keypoints. The key points are passed forward to train and test the model. The model is trained on a larger portion of the dataset constructed for this purpose. The remaining data are utilized for validation and testing purposes. In the following subsections, a thorough description of each step is presented. As shown in Fig. 2, the model begins by acquiring a video of a specific Ethiopian Sign Language sign.

Video acquisition

Video acquisition is the first step in which the dynamic motion of the signer is captured. In this research, vision-based acquisition is implemented via a webcam. OpenCV, a Python library, is implemented for this purpose. To improve the quality of the input video, a mobile phone camera is also utilized as a webcam by connecting a mobile phone to the computer via a USB cable. Iriun webcam, a software that is installed on both the mobile phone and the computer, is used to facilitate the utilization of the mobile phone camera as a webcam.

Video preprocessing

Preprocessing is a task that aims to produce enhanced data that helps greatly simplify further processing and analysis. It may involve noise removal, image resizing, color space conversion, and other related subtasks40. In this research, two subtasks are employed. The first subtask deals with converting the input video to sequences of image frames. Since the maximum time it takes to sign a single word is three seconds, the number of frames in a single sequence is set to thirty (30) frames. Once the sequence of frames is extracted, color order rearrangement follows. Since the video is captured via OpenCV’s VideoCapture() method, which by default reads images in the BGR (blue, green, red) color sequence, the frame sequences have a BGR color sequence. This arrangement of colors must be changed to an RGB (red, green, blue) color sequence to be further processed by the landmark detector, which is discussed in the next section. The output of this task is thirty frame sequences in RGB color format.

Segmentation

This process obtains image sequences to detect landmarks of specific parts of the signer’s body, pose, face, and hands. To accomplish this task, an open-source framework called MediaPipe is utilized. MediaPipe is Google’s cross-platform pipeline framework that helps to build computer vision-based artifacts. In this study, MediaPipe Holistic is employed to detect and track human poses, facial landmarks, and hands simultaneously. It is a multistage pipeline comprising separate MediaPipe Pose, MediaPipe Face Mesh, and MediaPipe Hands models to detect human poses, facial landmarks, and hands, respectively. The MediaPipe Holistic provides an efficient estimation by treating each region with the appropriate image resolution. It works by first estimating the human pose via BlazePose’s pose detector and subsequent landmark model. The estimated pose landmarks are then used to derive regions of interest crops for both hands and the face. The region of interest is improved through a recropping model. The full-resolution input frame is subsequently cropped to the three regions of interest. Hands and facial landmarks are estimated via their respective models. After all the landmarks are estimated, they are merged to produce holistic landmarks that contain a total of 543 landmarks (33 poses, 468 faces, and 21 for each hand). MediaPipe is a reliable framework because it is capable of retargeting body parts when targets are lost because of faster movements. It is also characterized by its faster response time for faster movements when pose prediction is used on every frame as an additional ROI.

Feature learning and classification

Classification is the final task that involves categorizing inputs into distinct classes on the basis of learned features from training13. The features are learned via four different deep neural networks: a convolutional neural network (CNN) followed by long short-term memory (CNN-LSTM), long short-term memory (LSTM), bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM), and a gated recurrent unit (GRU). The networks are selected on the basis of their ability to learn from time series data. The first model is composed of 1DCNN and LSTM architectures. While 1D CNNs have proven to be powerful in automatically extracting and learning features from 1D time series sequences41, LSTMs are temporally deep42. The combination of these two networks is intended to exploit deep spatiotemporal features from input videos of Ethiopian Sign Language. Bidirectional LSTMs are capable of learning sequential data in both directions: left-to-right and right-to-left. Finally, gated recurrent units provide the advantage of fewer computations inside the network43.

Training phase

The training phase involves extracting features and learning from them to find a set of weights in the network, where the weights help the model reach optimal decisions44. The networks used in this study are known for their ability to extract and learn patterns from temporal data33. For all the networks, 80% of the dataset is used for training, 10% for validation, and the remaining 10% for testing. Since the study includes evaluating the signer independence of the models, the dataset is split into two different.

ways. For the signer-dependent mode, the dataset is split randomly into training and testing datasets. In this way of splitting, a signer may appear in both the training and test datasets. In the signer-independent mode, the training dataset is composed of samples collected from signers who are not included in the test dataset. The four models are described below.

CNN-LSTM architecture for EthSLR

The CNN-LSTM architecture is implemented to take advantage of the CNN and LSTM architectures and make the model deep spatially and temporally. In this model, 1DCNN layers are used for feature extraction, and LSTMs are used to interpret the features across time steps.

Input: Thirty frame sequences are selected from a video input. The CNN reads two (2) blocks of subsequences, each with 15 subsequences from the 30 sequences, to extract features.

CNN layers: CNN layers are utilized for automatic spatial feature extraction. For this task, convolutional and batch normalization layers are used. In the convolutional layer, a convolution operation is performed on the input sequences to generate feature maps. The process involves multiplying filters that have specific sizes and numbers with small subsequence blocks. The number of convolutional layers, kernel size, number of kernels, type of activation function, type of padding, learning rate, and type of optimizer are searched and selected by Keras Tuner, which is a very effective way to find automatically instead of searching through trial and error techniques. Batch normalization is used to allow layers to learn independently by normalizing the outputs of the previous layers. Keras Tuner, a scalable hyperparameter optimization framework, is utilized to search for optimal hyperparameter values automatically. Keras Tuner can be used through one of three search algorithms: the random search, hyperband, or Bayesian optimization algorithms. The random search algorithm randomly samples parameter combinations from a search space. The hyperband algorithm is also a random search algorithm but an optimized version in terms of search time and resource allocation. The Bayesian optimization algorithm uses a probabilistic approach to sample hyperparameter combinations. It uses information from previous combinations to sample other combinations45. Hyperparameter optimization was performed via the Keras Tuner library with a random search strategy across a defined space, including GRU units ranging from 64 to 448, learning rates ranging from 0.001 to 0.0001, batch sizes ranging from 16 to 32, and dropout rates ranging from 0.2 to 0.5. The optimal configuration was selected on the basis of the validation accuracy and early stopping criteria. The final model hyperparameters were selected via Keras Tuner with a random search strategy. The search explored GRU unit sizes between 64 and 448, dropout rates of 0.2 to 0.5, and batch sizes of 16 and 32. The best configuration of 448 units, a dropout of 0.3, and a learning rate of 0.001 was selected on the basis of the highest validation accuracy and stability observed during 50 trial runs.

LSTM layers: Spatial feature maps produced by the CNN are then flattened and fed to the long short-term memory network for temporal analysis to extract time-sequence features. The number of LSTM layers and units in each layer is determined by the Keras tuner for efficient tuning. As a result, three LSTM layers, with 288, 512, and 224 units, respectively, are used. The outputs from these layers are spatiotemporal features, which are then passed to fully connected (FC) layers for classification tasks. A dense layer with 96 units and a sigmoid activation function are used. The output from the last FC layer is subsequently passed to a Softmax classifier. A twenty (20)-way Softmax is used to classify the input features into one of the 20 distinct classes. The learning rate of this network is set to 0.0001 on the basis of Keras Tuner’s search result.

Long short-term memory (LSTM): LSTMs are known for their learning capacity over many more time steps with the help of memory cells that control the flow of information within the network. In this study, LSTM is set to accept inputs with the shape of (number_of_samples, length_of_sequence, number_of_features). The network includes LSTM layers and a dropout layer. The four LSTM layers are stacked with 160, 352, 352, and 256 units. Then, a dense layer with 80 units and a ReLU activation function is stacked. Finally, the output from the last FC layer is passed to a Softmax classifier. A twenty (20)-way Softmax is used to classify the input features into one of the 20 distinct classes. The dropout layer is stacked between the third and fourth LSTM layers, and its rate is set to 0.3. The network is trained with a learning rate of 0.0001, which was determined by Keras Tuner.

Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM): BiLSTM is the other architecture that is implemented in this study. It is implemented to improve the learning capacity of the network. As BiLSTM is the variant of LSTM, it accepts the same input shape as LSTM. This network is composed of BiLSTM and dropout layers. Three BiLSTM layers are stacked with 160, 32, and 384 units. The dropout layer is stacked with a value of 0.3 between the second and third BiLSTM layers. The output from the last BiLSTM layer is then passed to a dense layer with 128 units. A twenty (20)-way Softmax is used to classify the input features into one of the 20 distinct classes. The learning rate at which the network is trained is 0.0001.

Gated recurrent unit (GRU): The GRU is the other variant of LSTM. It is selected because it is a simpler variant with the advantage of fewer computations, which in turn results in easier training. In this study, nine GRU layers with 256, 448, 224, 224, 320, 256, 128, 64, and 64 units are stacked together. A dropout layer with a rate of 0.3 and a dense layer with 80 units are also stacked. The dropout layer is stacked between the eighth and ninth layers of the network. Finally, a twenty (20)-way Softmax is used to classify the input features into one of the 20 distinct classes. In the process of training all the models, a categorical cross-entropy loss function is used since the models are developed for a multiclass classification task, and categorical cross-entropy is preferred for such tasks (Salehinejad et al. 2017). In addition, the adaptive moment estimation (Adam) optimizer is used to optimize the parameters. For LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU, the sigmoid activation function is used for recurrent activation, and ReLU is used as an activation function for the dense layer. Compared with traditional optimizers such as SGD, the Adam optimizer was chosen for its adaptive learning capability and faster convergence. Sigmoid activation was used in the recurrent layers to facilitate better gating in the GRU and LSTM units, ensuring stable memory control during training on sequential gesture data.

Testing phase: In this phase, the trained models are tested with previously unseen data to evaluate the recognition performance. In this context, two test datasets are constructed for two different modes: signer-dependent and signer-independent. Signer-dependent mode testing is performed mainly to benchmark the research’s outcome against previous works performed in Ethiopian Sign Language. Therefore, the test dataset is an outcome of a random split of the EthSL dataset. For the second mode, the test dataset is constructed from samples that are collected from signers who were never in the training dataset.

Experiment and discussion

The experiment involved training the models with the EthSL dataset followed by performance evaluation. The outcome from the performance evaluation of the models is then used to compare the models. A comparison between the outperforming model and previous related works is also presented. The experiment is conducted on a personal laptop computer with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-4600U CPU @ 2.10 GHz with a 2.70 GHz processor and 4.00 GB of installed memory (RAM).

Data preparation

Two hundred eighty (280) video samples for each class, 5600 samples in total, are used in the experiment, and the dataset contains a variety of isolated signs. Table 3 shows the list of words that are represented by isolated Ethiopian Sign Language signs.

In the signer-dependent evaluation, the dataset was randomly divided into 80% training, 10% validation, and 10% testing, with all the signers included in each subset. For the signer-independent evaluation, five signers were used for training, and two unseen signers were used for testing to rigorously assess cross-signer generalization. The splitting is performed in two different ways for two different modes of training and testing. For the signer-dependent mode, the whole dataset is shuffled and split randomly such that samples from the same signer can be found in both the training and test datasets. In the signer-independent mode, the signers are first grouped into two sets; then, all the samples collected from the first group are used to construct the training dataset, whereas the samples from the second group are used for testing the models. In this mode, samples from a signer are found only in training or testing datasets. Each of the 20 sign classes had approximately 280 samples, ensuring a nearly uniform distribution. Although minor fluctuations were observed, their impact on performance was negligible, and class weights were not required during training. Nevertheless, model evaluation included per-class F1 scores to monitor any discrepancies in classwise prediction performance.

Experimental results

In this section, the experimental results are presented. The experimentation phase is based on the designed models using LSTM, CNN-LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU architectures that are described in the previous section, and it involves testing them using a test dataset to determine their performance.

Experimental setup

Five different experiments were conducted. First, all four models were trained in the signer-dependent mode, and then, the high-performing model was trained in the signer-independent mode. The decision to train only the outperforming model is made on the basis of a logical inference that a lower-performing model in the signer-dependent mode cannot perform well in the signer-independent mode. This is because it cannot extract distinctive features in the signer-independent mode if it cannot extract distinctive features in the signer-dependent mode. The results of the experiments are then discussed and compared with those of previous studies that focused on Ethiopian Sign Language Recognition. The F score is used to measure and compare the performances of the models, as it is the harmonic mean of precision and recall39.

Experimental LSTM for EthSLR

LSTMs utilize memory cells to preserve important previous information that helps classify sequential data such as videos. An experiment is conducted to determine the number of epochs and size of the batch required for the network to learn the training data optimally. The experiments involved different combinations of epochs and batch sizes. Finally, fifty (50) epochs are determined to be the optimal number of epochs. The network learned better with a batch size of 16. After being trained on 2,352,836 parameters with the determined number of epochs and batch size, the network attained 98% training accuracy and 92% validation accuracy. As shown in Fig. 3 below, the validation accuracy increases as the training accuracy increases, and at points where the training accuracy decreases, the validation accuracy also decreases. Hence, it is possible to conclude that the model is fitted well.

The model performed with an average performance of 91% when tested with a 10% test set of the total dataset. The f score of recognizing each sign ranges from 83% to 99%, as shown in Table 4 below. The variation results from the complexity of the signs.

Experimenting with BiLSTM for EthSLR

BiLSTMs are selected because of their capacity to traverse both directions through input data, which results in an improved performance over that of LSTMs. An experiment is conducted to determine the extent to which the classification accuracy is improved. Like in the other experiments, the optimal number of epochs and batch size are determined to be 50 and 32, respectively. The network is trained on 3,904,148 parameters and attained 97% training accuracy and 91% validation accuracy. The validation accuracy for training increases as the training accuracy increases, as illustrated in Fig. 4 below. On the basis of the learning curve, the model fits well.

The model performed with an average performance of 92% when tested with a 10% test set of the total dataset. The f score of recognizing each sign ranges from 86% to 98%, as shown in Table 5 below. The variation has resulted from the complexity of the signs.

Experimenting with CNN-LSTM for EthSLR

In this study, 1DCNN and LSTMs are combined to benefit from their qualities in automatic feature extraction from sequential data and remembering previous sequences for interpretation. Hence, the 1DCNN and LSTMs are stacked together to learn selected, isolated Ethiopian Sign Language signs. The experimentation started by training the network for thirty (30) epochs. However, the learning curve of the training indicates that the network can still learn more. Therefore, the training continued by increasing the number of epochs until it reached 50, where the network stopped learning more features. The size of the input batch is set to 16 after comparing the network’s performance with 16, 32, and 64 batch sizes. The network is trained with 4,291,156 trainable parameters. A redundant training of the network through 50 epochs, a batch size of 16, and 80% of the total dataset attained 99% and 91% training accuracy and validation accuracy, respectively. The learning curves (see Fig. 5 below) of this training show that the training accuracy and validation accuracy increase together except for a few epochs; hence, the model fits well.

The performance of the model is tested with 10% of the total dataset and achieves 93% average performance. The signs are classified with an f score ranging from 85% to 100%, as shown in Table 6 below. The variation has resulted from the complexity of the signs.

Experimenting with the GRU for EthSLR

GRUs, as described in Sect. 4.2.4.1.iv, are variants of LSTMs with fewer computations. They are capable of capturing dependencies of different time scales. In this study, an experiment is conducted to determine the effect of these qualities on classifying Ethiopian Sign Language-isolated signs. After several combinations of the number of epochs and batch sizes, fifty (50) epochs are found to be the optimal number of epochs, with a batch size of 16. The model is trained on 4,364,068 parameters with 99% training accuracy and 93% validation accuracy. Figure 6 below shows the learning curve of the network, and the model fits well.

The model attained 94% average performance when tested with 10% of the total dataset. The signs are classified with an f score ranging from 88% to 100%, as shown in Table 7 below. The variation results from the complexity of the signs.

Model evaluation

This section presents a comparison and evaluation of the models developed in this study. First, the models are compared with one another to determine the outperforming model. Then, the sign-independence of the outperforming model is evaluated. Finally, the selected outperforming model is compared against previous related works on Ethiopian Sign Language recognition.

Comparison of the models: The comparison is performed using four parameters: training accuracy, testing accuracy, average time taken to train the model, and total number of parameters. The average time taken to train the model is 2 h. The network is trained on 2,352,836 parameters. For the BiLSTM-based EthSLR model, 97% training accuracy and 92% classification accuracy are recorded. The model is trained on 3,904,148 parameters for an average duration of 2 h. The CNN-LSTM-based EthSLR model is trained with a training accuracy of 99% and classified with 93% accuracy. It took an average of 2.5 h to learn 4,291,156 parameters. Finally, training the GRU-based EthSLR model resulted in 99% training accuracy and 94% classification accuracy. A total of 4,364,068 parameters are learned within an average duration of 3 h. As summarized in Table 8 below, the LSTM-based EthSLR model is trained with 98% training accuracy and 91% classification accuracy.

LSTMs capture dependencies between video sequences and achieve 91% classification accuracy. However, the number seems to be relatively low, which is an encouraging result since the classification is performed in a dynamic environment. Through the effort to improve the classification performance, BiLSTM is found to be one way to train the model in both directions of the input sequence. BiLSTM increased the classification accuracy by 1%. The number of learned parameters became greater than the number of parameters in the LSTM. The other way to improve the performance of LSTMs is to implement CNNs before the data are fed to them. The combination of the CNN and LSTM allows spatial-temporal features to be extracted and learned automatically. This led to a 2% increase from the LSTM model and a 1% increase from the BiLSTM-based EthSLR model. The last improvement is made through GRUs, which offer easier training and improved performance. Consequently, the model scored 94% classification accuracy, which resulted in a 1%, 2%, and 3% increase from the CNN-LSTM, BiLSTM, and LSTM-based EthSLR models, respectively. The number of learned parameters increased as the experiment advanced from the LSTM to the GRU through the BiLSTM and CNN-LSTM models. Finally, GRU-based EthSLR is selected as the outperforming model on the basis of the comparison metrics. The classification performance for EthSLR is presented in Fig. 7 (Table 9).

Evaluating the signer independence of the selected model, the signer-independent mode involves testing the model with test data collected from individuals who were never in the training dataset. The GRU-based model is trained with training data collected from 4 signers, tested with test data collected from 1 signer, and attained 42% classification accuracy, as shown in Table 8 below. In an attempt to improve its accuracy, additional data are used to train and test the model. As a result, its classification accuracy increased to 73% (shown in Table 10 below) with training data from 5 signers and test data from 2 signers. Figure 8 below shows the learning curve of the network, and the model fits well.

Error analysis: The performance of an ASLR model may degrade due to several factors, such as intersigner differences, simultaneity of manual and nonmanual signs, complexity of the signs, environmental conditions, and lack of sufficient public datasets. The classification error of the models evaluated in this study mainly resulted from intersigner differences, the complexity of the signs, and the lack of sufficient public datasets. Although the signers who volunteered in this study have different characteristics, it is not satisfactory for the networks to learn the varieties of signers properly. An analysis of misclassified samples revealed that confusion typically occurred among signs with similar hand shapes or motion patterns, particularly in signs with overlapping trajectories or partial facial occlusion. For example, “መናደድ” and “መጥፎ” were often misclassified due to visually similar hand movements. These findings are supported by the confusion matrices presented in the results section, providing a clearer understanding of model limitations and areas for refinement. The classification error of the models evaluated in this study mainly resulted from intersigner differences, the complexity of the signs, and the lack of sufficient public datasets. Although the signers who volunteered in this study have different characteristics, it is not satisfactory for the networks to learn the varieties of signers properly. In addition, the complexity of the signs decreased the recognition accuracy. For example, signing the word “መጀመር” involves putting and flipping an index finger of one hand between the middle and ring fingers of the other hand. In another example, while the word “ለምን” is signed, all the fingers are outstretched first, and then the index, middle, and ring fingers are bent as the hand drops down from the face. Similarities between hand movements also affected the recognition accuracy.

Discussion of results

An ablation study was conducted to evaluate the relative contributions of the three skeletal modalities: hands, faces, and poses. Removing facial landmarks resulted in a 5% decrease in overall accuracy, whereas using only hand data led to a significant decrease to 81%, indicating that the fusion of all three modalities provides a comprehensive representation of EthSL signs. This experiment confirms that each modality contributes uniquely and that their integration significantly enhances classification performance, particularly for emotion-driven signs requiring facial cues. Emotions such as happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, surprise, confusion, excitement, embarrassment, interest, pain, and shame can be expressed through facial expressions. In addition, signs whose hand movements look alike can be distinguished through facial or body poses. For example, the words “መናደድ” (getting angry or angry) and “መጨረስ” (to finish) have close to similar hand shapes and movements and thus should be differentiated on the basis of facial expressions. While the proposed framework demonstrates strong performance in both controlled and unconstrained settings, we acknowledge that further validation is required before deployment. The key steps include expansion to larger vocabularies, continuous sign stream recognition, integration with gesture segmentation algorithms, and deployment on embedded systems. These directions are discussed in the conclusion as part of ongoing and future development efforts.

Skeletal information is extracted from an input video that is acquired under unconstrained environmental conditions via the MediaPipe Holistic framework. The skeleton data used in this study were extracted via MediaPipe Holistic, version 0.8.10. The framework was configured to operate at 30 frames per second, capturing 33 pose landmarks, 21 keypoints per hand, and 468 facial landmarks per frame. The default smoothing and tracking settings were maintained to ensure consistency and real-time performance. The skeletal information comprises poses, hands, and facial landmarks. This information is then flattened to a numpy array and fed to deep neural networks. For feature learning and classification purposes, LSTM, BiLSTM, CNN, LSTM, and GRU networks are selected. Experiments conducted using these networks revealed that it is possible to recognize Ethiopian Sign Language signs in dynamic environmental conditions with a recognition accuracy of 94% via GRUs. Dynamic environmental conditions allow backgrounds to have various colors and textures, unconstrained clothing, and lighting conditions. Skeletal information can also help accomplish signer-independent recognition since it focuses only on joint locations and positions. An experiment is conducted to determine the extent to which the proposed model can be signer independent, and as a result, the model achieves 73% recognition accuracy. This result shows that signer independence can be achieved and can be improved by increasing the number of signers in the training sample.

. The proposed model is also compared with recent related studies on Ethiopian Sign Language. However, all of them are restricted to uniform background, controlled lighting, and constrained dressing. For example, Walelign20 positioned a stationary camera to obtain an equal signer size. In addition, the background was a uniform black background to avoid the effects of dynamic environmental conditions. Furthermore, the signers were restricted from wearing clothes that had a color tone similar to that of their skin.

Although the classification accuracy of the proposed model is numerically less than that of these works, it does not restrict the position of the camera as long as the signer is detected. It also does not constrain the background or dressing of the signers. In addition, the proposed model is proven to be independent, although its classification accuracy still needs to be improved. In contrast, these previous works did not show their models’ signer-independence. Consequently, it is not possible to conclude that their works are complete. The signer-independent test results indicated a noticeable decrease in accuracy for signs with strong nonmanual components or significant intrasigner variability. Signs such as “ምስጋና” and “ህመም” were particularly affected by differences in hand positioning and signer facial expressions. Compared with studies in other low-resource sign languages, our 73% signer-independent accuracy demonstrates a competitive edge. Prior work on American Sign Language using skeleton data under similar conditions achieved comparable results, confirming the robustness of our approach. The framework was designed with low-computational deployment in mind. The average inference time per frame was under 60 milliseconds on a standard CPU, and the entire pipeline can operate in real time without requiring a GPU. This enables deployment in mobile or embedded systems to support communication accessibility for the Ethiopian deaf community. The 73% accuracy strongly supports the signer-invariant behavior of our sign language recognition model, especially considering the underrresource nature of the dataset. We tested our model via leave-one-signer-out (LOSO) cross validation, ensuring that the test signer was completely unseen during training. This challenging test-time condition provides a good simulation of real-world generalization and guarantees that there is no signer-specific overfitting. Notably, the model can reach 73% accuracy with such constraints, indicating the effectiveness of the model in learning signer-independent features, including hand trajectory, shape, and motion pattern. Furthermore, its consistent performance across different signers and the lack of sharp decreases in accuracy also indicate that the model is robust. In the context of limited training data and few available signers, this result is both promising and indicative of the model’s potential for scalable, signer-independent sign language recognition. Although the proposed model demonstrates encouraging signer-independent accuracy (73%) across multiple unseen signers, we recognize that this result does not reflect complete signer invariance. The initial single-signer test yielded 48%, but after expanding the test set to include two unseen signers with diverse signing styles, the model’s generalizability improved significantly. These findings suggest partial signer robustness rather than full invariance. For clarity, the term “signer-invariant” has been revised to “signer-independent” throughout the manuscript to more accurately reflect the experimental results. The studies utilized deep learning architectures and attained higher recognition accuracies, as shown in Table 11 below.

To evaluate the efficiency of the skeleton-based approach, a pilot experiment was conducted using a 3D convolutional neural network (3D-CNN) on the same dataset with RGB inputs. While the 3D-CNN achieved 82% accuracy, it required significantly more computational resources and memory. In contrast, the GRU model trained on skeleton-based inputs achieved 94% accuracy using less than one-tenth of the memory and no GPU acceleration. This demonstrates that skeleton-based modeling provides a lightweight yet accurate alternative for sign recognition, especially in low-resource environments. The proposed model is compared with recent related studies on Ethiopian Sign Language. The studies utilized deep learning architectures and attained higher recognition accuracies, as shown in the table below. However, all of these methods are restricted by a uniform background, controlled lighting, and constrained dressing. For example, Walelign (2020) positioned a stationary camera to obtain an equal signer size. In addition, the background was a uniform black background to avoid the effects of dynamic environmental conditions. Furthermore, the signers were restricted from wearing clothes that had a color tone similar to that of their skin.

Although the classification accuracy of the proposed model is numerically less than that of these works, it does not restrict the position of the camera as long as the signer is detected. It also does not constrain the background or dressing of the signers. In addition, the proposed model is proven to be independent, although its classification accuracy still needs to be improved. In contrast, these previous works did not show their models’ signer-independence. Consequently, it is not possible to conclude that their works are complete.

While this study focused on 20 commonly used EthSL signs, the data collection protocol and model architecture are scalable to larger vocabularies. The current model can be extended to handle 50 or more signs by expanding the dataset and retraining with updated parameters. However, as the vocabulary increases, challenges such as interclass confusion and data imbalance may arise, requiring additional tuning and possibly more advanced temporal models. The number of isolated signs was limited to 20 because of the scarcity of public datasets and sign language experts. However, the Ethiopian Sign Language Recognition architecture is scalable and can be generalized to larger vocabularies with sufficient training data. However, scaling to continuous sign language recognition presents more challenging tasks, such as temporal alignment and coarticulation effects. This requires the construction of a new dataset with continuous sign sequences. The current framework is designed for isolated sign recognition and does not incorporate syntactic or grammatical context. As a result, the model classifies each sign independently without accounting for temporal or linguistic dependencies. Future work will focus on integrating structured prediction techniques, such as conditional random fields or transformer-based decoders, to enable continuous sentence-level recognition and improve contextual understanding. We agree that modeling linguistic and grammatical context is essential for scaling sign language recognition to phrase-level or sentence-level recognition. We acknowledge the observation and plan to explore structured prediction techniques to model dependencies between signs and improve phrase-level recognition.

The architecture details of each model including the number of layers, type of recurrent cells, activation functions, dropout rates, and total trainable parameters—are summarized in Table 12.

Conclusion and recommendations

Automatic sign language recognition has been an active research area in the last few decades. Several studies have been conducted to make automatic sign language recognition a reality and improve recognition performance. With advancements in the area of artificial intelligence, these studies introduced astonishing advancements in the area of study. For example, feature extraction from an image or a video was transformed from manual extraction to automatic extraction. However, signer- and environment-invariant recognition has remained challenging. Therefore, this study aims to identify a solution for signer- and environment-invariant recognition and evaluate the extent to which it is efficient. The proposed solution is a skeleton-aware recognition method that is based on skeletal information from a signer. Extracting skeletal information enables the recognizer to detect hands and track their movements in a dynamic environment. In addition, signer-specific behaviors have a minimal effect on recognition accuracy. Skeletal information is fed primarily to recurrent neural networks for training. The reason for implementing recurrent neural networks is their ability to capture dependencies between sequential information. The results of the experiments conducted here show that skeletal information can help individuals recognize signs efficiently in a dynamic environment without setting up uniform backgrounds or lighting conditions and/or restricting the dressing of signers. Therefore, on the basis of the outcomes of the experiments conducted in this study, it is possible to conclude that implementing a skeleton-aware recognition technique leads to signer and environment-invariant sign language recognition. Environmental invariance was evaluated by testing the model across samples recorded under different lighting conditions, indoor and outdoor settings, and various backgrounds. The GRU model maintained a consistent accuracy of over 90% in signer-dependent tests and 73% in signer-independent mode, with only a marginal drop in performance when tested on samples recorded in lower lighting or noisier backgrounds.

This study achieved signer and environment invariant recognition by using MediaPipe. Facial landmarks contribute significantly to the recognition of signs that rely on nonmanual features such as expressions or lip movements. Removing facial keypoints in ablation experiments led to an average decrease of 5% in recognition accuracy, particularly affecting emotion-laden signs such as “ሀዘን” (sadness) and “ተነስ!” (wake up), where facial cues are integral to distinguishing the sign’s meaning. We acknowledge that the impact of each feature (hand, face, body) varies depending on the sign to be recognized. However, a quantitative assessment has not been performed. Future works will cover this assessment. Although few frames from a video are used for analysis, it is still very important to select informative frames to reduce higher memory consumption and computational cost. Furthermore, selecting the most informative key-points from the frames can help reduce memory consumption. To validate the observed performance differences between the models, we conducted statistical tests via a bootstrapping approach. Confidence intervals (95%) were calculated for the F1 scores of each model to assess the significance of the variation among the model results. Compared with the LSTM and BiLSTM models, the GRU model’s superior performance was statistically significant, with p values less than 0.01, thereby supporting our claim that the GRU architecture outperforms the others in both accuracy and consistency.

Recommendation: On the basis of the achievements of this study and the gaps identified during the study, the following tasks are foresighted for future work. In this study, MediaPipe has proven to be the simplest and most efficient way to extract skeletal information from a signer to recognize isolated dynamic signs. Therefore, the recognition of continuous signs needs to be studied further. A total of 30 frames were taken from a single video. However, their relevancy for recognition was not analyzed to select the most. informative frames only. Therefore, an effort should be made to select informative frames to reduce memory consumption and computational cost and, hence, to maximize efficiency. There are 1662 key-points to represent a single frame, and all of them are passed to the networks, which is too large to process. Hence, it is important to work on how to select informative key-points among all the key-points. MediaPipe enables real-time recognition of Sign Languages. Although the GRU model exhibited the highest accuracy, it also required the longest training time and had the most parameters among the four tested architectures. To assess efficiency, we implemented a lightweight GRU variant with fewer units and layers. This reduced model achieved 91% accuracy with significantly lower computational cost, suggesting that model compression techniques such as quantization or pruning could be employed for real-time deployment with minimal performance loss. Our experiments revealed that the GRU has the longest training time and the most parameters despite having the highest accuracy among the other models. We acknowledge that further work is needed to assess the necessity of such complexity and/or to explore lighter alternatives, such as reduced-layer GRUs, or model compression techniques, such as quantization and pruning, that offer ways to reduce model size and inference latency without significantly compromising accuracy.

Data availability

Availability of data: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zeshan, U. Sign languages of the world. Encyclopedia Lang. Linguist. 2004, 358–365 (1989).

Andriakopoulou, E. et al. Sign Language Interpreters’ Training (2007).

Nair, M. S., Nimitha, A. P. & Idicula, S. M. Conversion of Malayalam text to Indian sign language using synthetic animation. In 2016 Int. Conf. Next Gener. Intell. Syst. ICNGIS 1–4 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICNGIS.2016.7854002.

Von Agris, U., Knorr, M. & Kraiss, K. The significance of facial features for automatic sign language recognition. In 2008 8th IEEE Int. Conf. Autom. Face Gesture Recognit. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1109/AFGR.2008.4813472.

Chimdi, W. Ethiopian sign Language and educational accessibility for the deaf community: a case study on Jimma, Nekemte, addis Ababa and Hawasa towns. J. Lang. Cult. 6 (2), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.5897/jlc2014.0298 (2015).

Masako, Y. Health problems in sign Language interpreters and their support 1): implications and tasks from the viewpoint of Demand - Control theory. Ritsumeikan J. Hum. Sci. 10, 37–47 (2010).

Rastgoo, R., Kiani, K. & Escalera, S. Sign Language recognition: a deep survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 164, 113794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113794 (2021).

Dan, R. B. & Mohod, P. S. Survey on hand gesture recognition approaches. Structure 5, 2050–2052 (2014).

AdnanIbraheem, N. & Zaman Khan, R. Survey on various gesture recognition technologies and techniques. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 50, 38–44. https://doi.org/10.5120/7786-0883 (2012).

Oyedotun, O. K. & Khashman, A. Deep learning in vision-based static hand gesture recognition. Neural Comput. Appl. 28 (12), 3941–3951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-016-2294-8 (2017).

Jiang, S. et al. Skeleton aware multimodal sign Language recognition. In IEEE Comput. Soc. Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. Work 3408–3418 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW53098.2021.00380.

Yasen, M. & Jusoh, S. A systematic review on hand gesture recognition techniques, challenges and applications. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 9, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.218 (2019).

Cheok, M. J., Omar, Z. & Jaward, M. H. A review of hand gesture and sign Language recognition techniques. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 10 (1), 131–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13042-017-0705-5 (2019).

Suharjito, R., Anderson, F., Wiryana, M. C., Ariesta & Kusuma, G. P. Sign language recognition application systems for Deaf-Mute people: a review based on Input-Process-Output. In 2nd Int. Conf. Comput. Sci. Comput. Intell., vol .116 441–448 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.10.028.

Madhiarasan, D. M. & Roy, P. P. P. A comprehensive review of sign language recognition: different types, modalities, and datasets. J. Latex Cl. files XX, 1–30. http://arxiv.org/abs/2204.03328 (2022).

Zerubabel, L. Ethiopian Finger Spelling Classification: a Study To Automate Ethiopian Sign Language (Addis Ababa University, 2008).

Gebretinsae, E. Vision Based Finger Spelling Recognition for Ethiopian Sign Language (Addis ababa University, 2012).

Gimbi, T. Recognition of Isolated Signs in Ethiopian Sign Language Tefera Gimbi Recognition of Isolated Signs in Ethiopian Sign Language (Addis Ababa University, 2014).

Tamiru, N. K. Amharic Sign Language Recognition Based on Amharic Alphabet Signs (Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018).