Abstract

The intersection of recent mpox outbreaks with HIV infections has become cause for concern in the disproportionately affected community of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM). There is a growing need to explicitly consider how behaviour plays a role in the spread of such diseases transmitted through close, prolonged contact. In particular, the duration individuals spend single or in relationships has yet to be incorporated into deterministic co-infection models, potentially underestimating the protective effects of stable partnerships. We propose an mpox and HIV co-infection model that incorporates the formation of pairs between individuals. Through analyses of the basic (\(\mathscr {R}_0\)) and mpox invasion reproduction numbers (\(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\)), we studied the effects of a pair formation structure on early disease dynamics in the gbMSM population. We demonstrate that considering pair formation and dissolution rates are critical in determining outbreak potential and severity, as well as accurately estimating reproduction numbers. Through simulations of the Canadian context, we show that these considerations remain important beyond the initial stages of the outbreak and can lead to more accurate predictions. Our work highlights that the particular pairing context and serological status of the population should always be carefully considered prior to intervention on behavioural patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On August 14, 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the most recent mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern” after an alarming rise in reported cases, particularly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and other African countries1. The 2024 outbreak comes on the heels of the 2022 mpox public health emergency, which was the largest ever recorded outbreak in non-endemic areas2. Many cases were reported in individuals without a history of travel to endemic areas or contact with infected animals, suggesting community spread3. The 2022 outbreak involved clade II, which generally has a positive prognosis with a survival rate of approximately 99.9%. In contrast, the 2024 outbreak is predominantly associated with clade I, which is more transmissible and leads to more severe infections with a mortality rate of up to 10%4,5. The first travel-associated cases of clade I mpox in North America were detected in late 20246,7.

Mpox is a zoonotic disease brought on by a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the Orthopoxvirus genus8. It is primarily transmitted through close contact with skin lesions, bodily fluids, and inhalation of respiratory droplets of infected individuals9. Following an incubation period, infected individuals enter a prodromal phase where they experience symptoms such as headache, fever, and swelling of the lymph nodes. A few days after symptom onset, they can begin to experience a rash and skin lesions, which typically appear on the face and extremities, but can also be found in the mouth, genitals, and eyes2. These lesions usually resolve without intervention within 2-4 weeks.

The recent mpox outbreaks have disproportionately affected individuals who identify as gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM)2. According to WHO worldwide data, 85.8% of cases reported since 2022 involving sexual behaviour were among the gbMSM community. Furthermore, 51.9% of mpox cases that reported human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status were positive10. HIV is most commonly spread through contact with genital fluids. If left untreated, HIV will begin to invade the body’s immune system and can develop into acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Once in the AIDS stage of infection, individuals are severely immunocompromised and only live around three years without treatment11. Co-infections of HIV and mpox result in a more severe disease outcome and higher death rate, primarily in individuals with uncontrolled and/or untreated HIV12. The WHO data identifies a critical overlap between the populations most impacted by the effects of mpox largely due to the shared transmission route of both diseases during sexual contact13. It has been suggested that having HIV may make it more likely for someone to contract mpox, but the lack of scientific literature on the relationship between transmissibility and co-infections makes the validity of this hypothesis unknown.

There is a growing body of mathematical modeling literature that explores HIV and mpox co-infection14,15,16,17. These models treat the spread of HIV and mpox in the same way as diseases with other transmission pathways, such as respiratory viruses, by assuming instantaneous contact. However, HIV and mpox often require continuous and prolonged sexual contact in order for transmission to occur. Additionally, individuals who are in monogamous relationships with other individuals sharing the same disease status are not spreading or acquiring any diseases, as they are not sexually interacting with the rest of the population. To address this, we will follow the approach given in Kretzschmar et al. and Betti et al. to examine the spread of the diseases through a pair formation lens18,19,20. Pair formation explicitly considers the length of time that individuals spend single and in monogamous relationships21,22,23. To our knowledge, these specific considerations have not been incorporated into any previous models of co-infection, leading to a loss of accuracy in predicting transmission and an underestimation of the protection provided by stable relationships among infected individuals.

This study formulates a mathematical model to study the co-infection of mpox and HIV, incorporating the formation of pairs among individuals. The model is presented in Sect. “The Model”, followed by the derivation of the reproduction numbers in Sect. “Reproduction Numbers”. In Sect. “Effects of Pairing on the Reproduction Numbers”, we consider the effects of various pairing scenarios on the reproduction numbers and compare this to the spread of mpox in an HIV endemic population. We more deeply investigate and generalize these results with a sensitivity analysis in Sect. “Sensitivity Analysis”, where we identify which factors are most important in the early spread of the diseases. A scenario analysis is performed on the Canadian gbMSM population in Sect. “Scenario Analysis in the Canadian gbMSM Population”, where simulations are presented for various pairing scenarios and compared to outbreak data. Finally, our results are contextualized in Sect. “Discussion” and their broader implications are discussed. Studying the intersection of these diseases is crucial for understanding the impact of co-infections on the gbMSM community, which is particularly vulnerable to their spread. Given the beginning of the circulation of a more severe strain of mpox, there is a new and pressing need to quantify the potential impact on the community and identify ways in which public health can curb its spread.

The model

The mathematical model proposed represents an epidemiological scenario where individuals infected with only HIV, individuals infected with only mpox, and individuals co-infected with both viruses coexist. They transmit both diseases through forming pairs and then engaging in sexual contact. As we aim to perform a macroscopic, population level analysis of the Canadian gbMSM community, we propose a deterministic model. Therefore, it cannot capture certain situations such as finite-time extinction and superspreader events which could be observed using a stochastic framework.

We consider that infection of mpox follows a susceptible-infected-removed (SIR) framework, whereas infection of HIV follows an SI framework. In particular, the retention of long-term immunity gained from mpox recovery is not dependent on HIV status. As a simplifying assumption, we do not explicitly model the effect of antiretroviral therapies (ART) on HIV spread. However, as this is an important factor in the control and spread of HIV, we instead consider it implicitly by reducing the HIV transmission rate. No other preventative and/or protective measures are considered. Individuals with HIV are in an immunocompromised state, where it is possible for them be more susceptible to contracting mpox per sexual interaction.

We assume the probability of going from susceptible to co-infected in a single sexual interaction to be negligible. For the purposes of this article, pairing is defined as being in the close proximity of a person such that the spread of HIV or mpox is possible. Thus, pair formation could occur prior to sexual contact, but sexual contact necessarily requires pairing. If one individual of a mixed pair (a pair with individuals of different disease statuses) is removed naturally (eg. death or no longer sexually active) from the population, the other individual is returned to the single compartment and can pair again. In scenarios such as non-disease related death, where we cannot know which individual has been removed, we assume the individual is returned to either compartment with equal probability. For example, if a pair consists of a susceptible and mpox infected individual and an mpox death occurs, the susceptible individual is returned to their singles compartment. However, if someone in the pairing is no longer sexually active, we cannot know who, and so we assume that the pair dissociation has equal probability of returning an individual to a susceptible class or an mpox infected class. As in Betti et al.18, we also assume that pairs are monogamous for the duration of their pairing and groups of more than two cannot be formed.

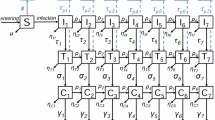

The model is presented graphically in Fig. 1, with no pair formation (left) and pair formation (right). The detailed equations for the model are in Supplementary Information Section 1 for the base model without pair formation and Supplementary Information Section 2 for the model with pair formation. Each variable is described in Table 1 and each parameter is presented in Table 2. We note restrictions on the transmission probabilities such that \(0 \le \tau _m, \tau _h \le 1\) and \(1 \le \phi\), but also require \(0 \le \phi \tau _m \le 1\).

Flowchart representing the mpox and HIV co-infection model with pair formation. The left figure represents the dynamics when there is no pair formation (base model), while the right figure represents all possible pairs that can be formed and the possible movement between pair compartments. In the base model (right), the green dotted lines represent transitions to the infectious compartments through pair formation by sexual contact. Disease death rates are omitted in the pair compartment diagram for visual clarity.

Results

Reproduction numbers

The disease free equilibrium (DFE) of an epidemiological model is defined as the steady state where no disease has been introduced into the population. For the model with pair formation, members of the population are either susceptible as individuals or pairs at the DFE, which is defined by

with all other compartments equal to zero.

The basic reproduction number represents the average number of infections produced by a single infectious individual in a fully susceptible population during their entire infectious period24. Using the next generation method (NGM), we determine the basic reproduction number of the co-infection model with pair formation to be \(\mathscr {R}_0 = max\{\mathscr {R}_0^h, \mathscr {R}_0^m, \lambda ^*\}\), where the definition of \(\lambda ^*\) and derivation of \(\mathscr {R}_0\) can be found in Supplementary Information Section 2. The HIV-only reproduction number is

and the mpox-only reproduction number is defined by

where \(K_m = \psi \tau _m(\rho +\delta _m+\mu +d_m) + (\delta _m+d_m+\mu )(\rho +\delta _m+d_m+\sigma +2\mu )\). It follows from the NGM method that the DFE is locally asymptotically stable for \(\mathscr {R}_0 < 1\)25.

It should be acknowledged that HIV is endemic in many current day populations. Therefore, a basic reproduction number which assumes disease emergence from a purely susceptible state is inapplicable and a more informative measure is an invasion reproduction number which captures the emergence of a secondary disease in an existing endemic state. Thus, an mpox invasion reproduction number \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) in a population with HIV endemicity can be derived. Details on the derivation of \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) for the pair formation model can be found in Supplementary Information Section 2. The HIV endemic/mpox free equilibrium requires \(\mathscr {R}_0^h > 1\) in order to exist, and is locally asymptotically stable for \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh} < 1\)26.

In the absence of pairing, we can similarly use the NGM methods to derive reproduction numbers for the base model. We define the basic reproduction number as \(R_0 = \max (R_0^h, R_0^m)\), where the HIV-only reproduction number is \(R_0^h = \frac{\psi \tau _h}{\mu + d_h}\) and the mpox-only reproduction number is \(R_0^m = \frac{\psi \tau _m}{\mu +\delta _m+d_m}\). We denote the mpox invasion reproduction number of the base model by \(R_i^{mh}\). For the explicit expression of \(R_i^{mh}\) and details on all reproduction number derivations performed on the base model, see Supplementary Information Section 1.

Effects of pairing on the reproduction numbers

In order to investigate the effects of the pairing parameters \(\rho\) and \(\sigma\) on reproduction numbers, we first establish a set of realistic baseline parameters in Table 2. In addition to the parameters sourced from literature, we assume a scenario where death from mpox is low so that that average death rates are comparable. Here, we assume \(1/d_m=48\) years and \(1/\mu = 50\) years. In the absence of ART, the average time from HIV infection to reaching the AIDS stage is about 10 years27. After an AIDS diagnosis, individuals live an average of 3 more years28. Therefore, we assume a total average disease lifetime of 13 years (\(1/d_h\)) for HIV. Opportunistic illnesses and co-infection become a serious threat to one’s health primarily when they are in the AIDS stage of their HIV infection. The life expectancy of an individual with AIDS falls to 1 year without treatment28. With this, we assume co-infected individuals have a decreased disease lifetime (\(1/d_c\)) of 11 years.

We choose an HIV transmission rate (\(\tau _h\)) that is 15% of the value found in literature to account for the lack of ARTs in the model29. This is approximately the percentage of the gbMSM population whose HIV remains detectable30. It is still unclear whether an HIV-positive status results in increased susceptibility to an mpox co-infection. For now, we assume there is no increased susceptibility (\(\phi = 1\)), noting that \(\phi\) does not appear in the formulations of \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\) and \(\mathscr {R}_0^h\). Finally, it is unknown how long it takes co-infected individuals to clear their mpox infection, but it has been suggested that in those with untreated HIV, it is longer than non-co-infected individuals31,32. Therefore, we assume an average of 32 days for a co-infected individual to recover (\(1/\delta _c\)), compared to the 27 days for a non-co-infected individual to recover (\(1/\delta _m\)).

When instantaneous contact is assumed, as in the model without pair formation, the reproduction numbers are \(R_0^m \approx 6.68\) and \(R_0^h \approx 2.6\) such that \(R_0 = R_0^m\) for the parameters in Table 2. This implies that both diseases will see outbreaks in an instantaneous contact scenario. We also have an mpox invasion reproduction number of \(R_i^{mh} = 7.39\), dictating that mpox will necessarily spread in an HIV-only endemic scenario.

When instantaneous pairing is not assumed, the contour plots in Fig. 2 show the type of pairing conditions giving rise to a co-infection outbreak in a fully susceptible population, with \(1/\rho\) and \(1/\sigma\) ranging from 3 days to 3 years (\(\rho , \sigma \in [1/1095, 1/3]\)). The plot for \(\mathscr {R}_0\) (Fig. 2(a)) shows the potential for either mpox or HIV to dominate in early transmission, whereas it was necessarily the case that mpox controlled the basic reproduction number for the model without pair formation. In this parameter range for \(\rho\) and \(\sigma\), \(\mathscr {R}_0 = \mathscr {R}_0^h\) for slower pair dissolution rates. This seems due to the low transmission rate of HIV, which requires more prolonged contact within a relationship in order to result in an infection. For HIV, long partnerships are not protective because the lifelong infection it causes means the disease will remain transmissible for the duration of the partnership. It is observed that \(\mathscr {R}_0 = \mathscr {R}_0^m\) for faster dissolution rates, likely due to the higher transmission rate of mpox and the disease more easily infecting a susceptible individual in a short period of time. Long relationships are also protective once the infected individual recovers. Importantly, the consideration of a pair formation structure allows for the possibility that both diseases could die out, which was impossible under the instantaneous contact scenario. Collectively, the plots also suggest that co-infection only occurs when pair-associated rates (\(\rho\), \(\sigma\)) are relatively quick.

Contour plots of reproduction numbers for an entirely susceptible population: (a) \(\mathscr {R}_0\), (b) \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\), (c) \(\mathscr {R}_0^h\), and (d) \(\lambda ^*\), varying the pair-associated parameters \(\sigma\) and \(\rho\) with remaining parameters set at baseline values in Table 2. The red lines reflect the outbreak threshold value of 1.

Across all plots in Fig. 2, the reproduction numbers increase for a fixed \(\sigma\) as \(\rho\) increases. This was to be expected, as the faster \(\rho\) is, the less time an individual spends single between pairings and the more pairings they are engaging in. However, this monotonic relationship does not hold for \(\sigma\). For example, as \(\sigma\) increases for \(\rho \approx 0.265\), Fig. 2a shows \(\mathscr {R}_0\) increasing from around 1.2 (orange) to over 1.4 (yellow), decreasing to under 1.2 (orange to green), increasing back to over 1.2 (orange), then finally decreasing again to just under 1.2 (green). This is caused by the non-monotonicities with respect to \(\sigma\) in \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\) and \(\mathscr {R}_0^h\) (Fig. 2b,c , respectively), demonstrating the complex nature of the reproduction numbers when pair dynamics are considered and the need to further understand the role of relationship length on disease spread.

In Fig. 3, plots for the initial spread of mpox in an HIV-only endemic population are shown. Figure 3a shows how pair formation and dissolution rates impact \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) for the baseline parameter set in Table 2. For the range of \(\rho\) and \(\sigma\) considered, \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) is distributed near 1. Similar to the basic reproduction number, this is drastically different to the pair-free model where we computed \(R_i^{mh} = 7.39\), indicating that pairing continues to have a strong influence on estimates of mpox spread in an endemic HIV state. We observe the dependence of \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) on \(\rho\) and \(\sigma\) to be similar to that of \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\), particularly with regard to the non-monotonicity in \(\sigma\). A natural question which arises here is how a potential increase in susceptibility to mpox infection due to HIV impacts the spread of mpox in the HIV endemic population. Figure 3b shows the contour plot for \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) where individuals with HIV instead have a \(20\%\) increased susceptibility to mpox \((\phi = 1.2)\). Although the invasion number increases slightly, no significant difference between the \(\phi =1\) and \(\phi = 1.2\) scenarios can be seen in the model with pair formation. However, in the base model with the instantaneous contact assumption, \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) increased from 7.78 to 8.87 with the increase in \(\phi\). Therefore, the sensitivity of the mpox invasion reproduction number to other parameters is also strongly influenced by pairing.

Contour plots of the mpox invasion reproduction number \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) for an HIV-endemic population, varying the pair-associated parameters \(\sigma\) and \(\rho\) with (a) \(\phi = 1\) and (b) \(\phi = 1.2\), with remaining parameters set at baseline values in Table 2. The red lines reflect the outbreak threshold value of 1. A comparison of the mpox reproduction number \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\) with the invasion reproduction number \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) in a (c) contour plot of the ratio \(\mathscr {R}_0^m / \mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) and (d) Venn diagram with threshold values for the baseline parameter set in Table 2, varying \(\sigma\) and \(\rho\).

In the base model, it was found that \(1<R_0^m < R_i^{mh}\) for the baseline parameters (Table 2). Figure 3c compares the relative magnitudes of the mpox reproduction number \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\) and the invasion reproduction number \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) for the model with pair formation (note the \(\sigma\)-axis has been modified for visual clarity). Similarly, it is observed that \(\mathscr {R}_0^m < \mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) in the ranges of \(\sigma\) and \(\rho\) tested. As such, the endemicity of HIV in a population is suggested to necessarily accelerate the initial spread of mpox in that population. This effect, however, dampens as \(\sigma\) increases, with \(\mathscr {R}_0^m / \mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) approaching 1. Within this space, there are several sub-cases regarding outbreak potential, shown in Fig. 3d. In the white region where \(\mathscr {R}_0^m< \mathscr {R}_i^{mh} < 1\), there is no mpox outbreak in both the entirely susceptible and HIV endemic scenarios. In the green region where \(1<\mathscr {R}_0^m < \mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\), an mpox outbreak occurs in either scenario. Finally, there is a small region in blue where \(\mathscr {R}_0^m< 1 < \mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\), meaning that an mpox outbreak would occur in an HIV endemic state but not in an HIV naive state. Importantly, the existence of this region demonstrates that the HIV status and pairing parameters together determine whether or not mpox becomes endemic in a given population.

Sensitivity analysis

The analysis on the effects of pairing on the reproduction numbers involved the selection of baseline parameters sourced from literature and reasonable assumptions, giving insight into the local sensitivity of the reproduction numbers to changes in the pairing parameters. We perform a global sensitivity analysis on the set of reproduction numbers using Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) and partial rank correlation coefficients (PRCCs)33. With this, a broader view of the effects of parameter changes on the reproduction numbers as well as a deeper understanding of their non-monotonic relationship with \(\sigma\) can be gained. In general, the closer the magnitude of a PRCC value is to 1, the more significant it is. As such, we take a magnitude \(\ge 0.5\) to indicate significance of the parameter. The sign of the value (positive or negative) indicates the type of correlation the parameter has with the chosen response variable.

Parameter ranges around the values found in literature (see Table 2) were chosen and uniform distributions were used for sampling, with 10,750 LHS samplings performed. Due to the lack of available information to guide the selection of parameters relating to co-infection and pairing, wider ranges were tested to ensure the possible parameter space is spanned. For \(\phi\), the upper bound was chosen such that \(max\{\tau _m\} \cdot max\{\phi \} \le 1\) to preserve model assumptions on the transmission probabilities.

Due to the non-monotonicities detected in the relationship between \(\sigma\) and the reproduction numbers, we first analytically identify where the changes in monotonicity occurs (see Supplementary Information Section 2 for details). For the HIV reproduction number, we obtain that if \(0< \sigma < \sigma ^*\), then \(\frac{d\mathscr {R}_0^h}{d\sigma } > 0\) and if \(\sigma ^* < \sigma\), then \(\frac{d\mathscr {R}_0^h}{d\sigma } < 0\), where

Using equation (4), the LHS samples were separated into two groups: \(0< \sigma < \sigma ^*\) (n = 1,223) and \(\sigma ^* < \sigma\) (n = 9,527). As such, the monotonicity requirement for PRCCs was met, and the results of the sensitivity analyses for both cases can be found in Fig. 4a,b, respectively. In each case, HIV-related parameters \(\psi\), \(\tau _h\), and \(d_h\) had significant, positive correlations with \(\mathscr {R}_0^h\). However, the pairing parameters play a very different role in the initial spread of HIV in a completely susceptible population. When \(0<\sigma <\sigma ^*\), the correlation with \(\rho\) is negligible, while \(\sigma\) emerges as the most significant factor, with increases in the parameter resulting in increases in \(\mathscr {R}_0^h\). In the majority of scenarios, it was the case that \(\sigma ^* < \sigma\). When this occurs, \(\rho\) has a significant, strong, positive correlation with \(\mathscr {R}_0^h\), and \(\sigma\) has a negative correlation with a PRCC of -0.4866. In other words, the longer the average relationship is, the greater \(\mathscr {R}_0^h\) becomes.

PRCC sensitivity analyses of the co-infection model with pair formation, with 10,750 LHS samples for the parameter ranges in Table 2 for (a) \(\mathscr {R}_0^h\) with \(0<\sigma <\sigma ^*\), (b) \(\mathscr {R}_0^h\) with \(\sigma ^* < \sigma\), (c) \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\) with \(\frac{d\mathscr {R}_0^m}{d\sigma } > 0\), and (d) \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\) with \(\frac{d\mathscr {R}_0^m}{d\sigma } < 0\). PRCC sensitivity analyses for \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) of the co-infection model with pair formation, with LHS samples for the parameter ranges in Table 2, where \(\mathscr {R}_0^h > 1\) and \(d_h = 1/4745\), for (e) slow (\(\sigma = 0.005\)), (f) moderate (\(\sigma = 0.1\)), and (g) fast pair dissolution rates.

Following a similar method (see Supplementary Information Section 2), we are able to implicitly determine when \(\frac{d\mathscr {R}_0^m}{d\sigma } > 0\) (n = 7877) and \(\frac{d\mathscr {R}_0^m}{d\sigma } < 0\) (n = 2873). Results of the sensitivity analysis are shown in Fig. 4c,d, respectively. In the case where \(\sigma\) is positively correlated, it emerged as the most significant factor with respect to changes in \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\), followed by the positively correlated \(\rho\). Increases in \(\delta _m\) result in significant deceases in the mpox reproduction number, whereas the positively correlated \(\tau _m\) fell short of the 0.5 threshold. In the case where \(\sigma\) is negatively correlated, the relationship between changes in the model parameters and changes in \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\) is different. All parameters except the pair dissolution rate \(\sigma\) are significant. Parameters \(\rho\), \(\psi\), and \(\tau _m\) are all strongly positively correlated with the mpox reproduction number. The mpox recovery rate \(\delta _m\) remains strongly negatively correlated with \(\mathscr {R}_0^m\).

The switch in correlation between \(\sigma\) and the reproduction numbers must be carefully understood within the context of the respective epidemiologies. In order for these diseases to be transmitted, sufficient close contact must occur. Risk of transmission increases over multiple exposures to the virus, meaning partnerships need to be long enough29. What is considered long enough on a population level is determined by the characteristics of the virus, and therefore the parameter set. For example, HIV has a relatively low transmission probability per contact, and so the disease and pairing characteristics (\(d_h, \psi \tau _h, \rho\)) dictate the value of \(\sigma ^*\). Due to this low probability and lifelong infection, the majority of samples fall into the \(\sigma ^*< \sigma\) (negatively correlated \(\sigma\)) scenario. By contrast, most samples for mpox fall into the positively correlated \(\sigma\) scenario due to higher transmission probabilities and immunity obtained from recovery. It is important to emphasize that HIV and mpox can still be transmitted even after a single exposure29.

Due to the complexity in deriving the mpox invasion reproduction number \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\), the non-monotonicity observed in the contour plots with respect to \(\sigma\) was not able to be isolated analytically. In order to test the sensitivity of \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) to the remaining parameters, we fix \(\sigma\) at slow (Fig. 4e), moderate (Fig. 4f), and fast (Fig. 4g) dissolution rates. The same LHS samples as before were used for the remaining parameters and it was ensured that \(\mathscr {R}_0^h > 1\) for each scenario. It should be noted that \(d_h\) and \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\) also have a non-monotonic relationship, and so \(d_h\) is fixed at its baseline value from Table 2.

The pairing rate \(\rho\) was strongly positively correlated with the mpox invasion reproduction number across the three scenarios, increasing in importance as \(\sigma\) increased. The parameters \(\psi\) and \(\tau _m\) did not meet the 0.5 threshold under slow dissolution, but did increase in importance as \(\sigma\) increased. The co-infection recovery rate \(\delta _c\) was the only other parameter found to be significant with a negative correlation with \(\mathscr {R}_i^{mh}\). These correlations went from strong to moderate as the pair dissolution rate increased. Interestingly, the mpox recovery rate (\(\delta _m\)), the increased susceptibility to mpox due to HIV (\(\phi\)), and the co-infection death rate (\(d_c\)) were found to be insignificant. Overall, these sensitivity analysis results confirm and generalize the relationships observed in the contour plots of the reproduction numbers for the baseline parameter set in Sect. “Effects of Pairing on the Reproduction Numbers”.

Scenario analysis in the Canadian gbMSM population

We consider and simulate various scenarios that can emerge within the context of HIV-mpox co-infection with pair formation in the Canadian context to gain a sense of the model’s qualitative behaviour. We set \(\Lambda =\mu P\), where \(P = 412,000\) is the approximate size of the Canadian behaviour-only gbMSM population (based on recent sexual experiences, regardless of identity)34,35. The remaining parameters are fixed at their baseline values (Table 2), while \(\sigma\) and \(\rho\) are varied with a focus on the region where both mpox and HIV obtain reproduction numbers greater than 1. For the initial conditions, it was assumed that approximately 8% (\(\approx\) 30,000 individuals) of the gbMSM population has HIV in accordance with data from the Public Health Agency of Canada, and that these individuals are distributed uniformly across the single and pair populations30. Additionally, we assume that 60% of gbMSM are single, as was found in a Vancouver study, and that most pairings are of individuals with the same disease status36. Finally, we chose the initial condition for individuals with mpox according to previous Canadian gbMSM modelling studies16. Accordingly, the initial conditions selected are: \(S(0) = 227,388\), \(I_m(0) = 36\), \(I_h(0) = 19,776\), \(P_{SS}(0) = 73,807\), \(P_{SI_m}(0) = 24\), \(P_{SI_h}(0) = 3,955\), and \(P_{I_hI_h}(0) = 4,614\).

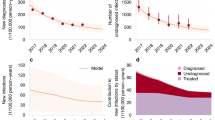

Results for the Canadian gbMSM population are presented for multiple pairing scenarios in Fig. 5. Across scenarios, multi-wave dynamics emerge in the spread of mpox, causing multi-wave dynamics to also emerge in co-infection cases. As \(\rho\) increased, increases in HIV, mpox, and co-infection cases and peak values are observed. The waves also become more frequent, with their duration becoming shorter. However, the relationship between \(\sigma\) and these metrics is more complex. When \(\rho = 1/3\), increases in \(\sigma\) result in increases to case counts and infection peaks. The \(\rho = 1/7\) scenario highlights that this is not always true for mpox and co-infection cases and peak values. Additionally, as \(\sigma\) increases in this range, cases of HIV in the population decrease. These results align with those observed in the contour plots for the mpox and HIV reproduction numbers. The characterization of the co-infection multi-wave dynamics also changes depending on the pairing scenario. In some cases, the initial peak is the largest, followed by waves of decreasing magnitude. In others, the second peak is the largest and then the waves become smaller. This demonstrates the ongoing, complex influence of the pair dissolution rate \(\sigma\) on mpox and HIV co-infection beyond reproduction numbers and the initial stages of the outbreak.

Scenario analysis of the model with pair formation for the Canadian gbMSM population with infection curves presented for (a–c) co-infected individuals, (d–f) mpox infected individuals, and (g–i) HIV infected individuals. Simulations are presented for (left) \(\rho = 1/7\) and (centre) \(\rho = 1/3\), varying \(\sigma\) (\(\sigma = 1/14, 1/10, 1/7, 1/5, 1/3\)), and (right) without pair formation with initial conditions in Sect. “Scenario Analysis in the Canadian gbMSM Population”. The inset graphs in (b,c,e,f) show the initial wave in more detail.

Simulations for the base model without pair formation (Fig. 5c,f,i) show that many of the aforementioned phenomena arise solely as a result of the pair formation structure. Without pairing, multiple waves of mpox and co-infection outbreaks still emerge, but they dampen more quickly over time. Additionally, a far greater number of cases are observed, with shorter and more severe outbreaks occurring and a shorter epidemic timescale overall.

These emergent differences in the simulations lead to a question of which model carries more predictive power. Figure 6 compares the pair formation and base models to monthly Canadian mpox case data collected by the WHO for the early stages of the 2022 outbreak10. As expected, the model without pair formation significantly overestimates case counts and the initial spread of mpox by assuming instantaneous contact. We wish to highlight that the model with pair formation was not explicitly fitted to the data, instead naturally aligning under the parameters sourced from literature (Table 2) up until the point of vaccination. When considering a pair formation structure, the model is able to more closely capture disease dynamics prior to public health intervention and awareness.

Plot of mpox cases for the pair formation model (blue, \(\rho , \sigma = 1/3\)) and base model without pair formation (yellow) vs monthly Canadian mpox data from the WHO10 (red) for the early stages of the 2022 outbreak. July 2022 marked the first full month of vaccine availability in Canada (dashed line), which is not accounted for in either model.

Discussion

Both HIV and the recent mpox outbreaks have disproportionately affected gbMSM individuals2. Co-infections in particular are cause for public health concern, as they can result more severe disease outcomes12. There are a few modeling studies focusing on co-infection, however all assume instantaneous contact between individuals in the gbMSM population14,15,16,17. In this study, we proposed an mpox and HIV co-infection model that incorporates pair formation dynamics. Through this, we sought to understand the importance of considering pair formation and dissolution rates on reproduction numbers and dynamics of disease spread.

We began by deriving the mpox and HIV reproduction numbers of the proposed model. Through contour plots, it was revealed that reproduction numbers are far lower in all considered pairing scenarios compared to those of the model with the instantaneous contact assumption. It is typical for basic reproduction numbers of diseases transmitted through close and/or sexual contact to be lower than those that are transmitted through respiratory pathways, aligning with our results. In the case of HIV, estimates of its basic reproduction number in the literature range depending on the specific context (age, locality, sexual behaviour of population, use of interventions, time of data collection, etc.). A recent estimate of the reproduction number in Canada for virally unsuppressed individuals was just around 137. Prior to the mpox outbreak of 2022, it was believed that an mpox outbreak could not be sustained in the human population (\(R_0^m < 1\))38. Estimates of \(R_0^m\) during the 2022 outbreak in the gbMSM population in regions of high incidence range from 1.4 to 1.839.

Together with the results in Sect. “Effects of pairing on the reproduction numbers”, this indicates that the reproduction numbers predicted by models with an instantaneous contact assumption can significantly overestimate disease spread in the initial stages of an outbreak and that pair formation models can more accurately estimate basic reproduction numbers. Consideration of pairing scenarios also presented the possibility that either disease could dominate in early transmission. The scenario of mpox spread in an HIV endemic population was additionally considered by deriving the mpox invasion reproduction number. We identified the possibility of a small pairing region where this consideration can lead to a tipping point in the spread of mpox.

A sensitivity analysis was performed on the reproduction numbers, with care given to the non-monotonicities detected with respect to the pair dissolution rate \(\sigma\). Where possible, the non-monotonic relationships were explicitly or implicitly identified, demonstrating the complex nature of the reproduction numbers when pair formation dynamics are considered. Overall, pairing dynamics (\(\rho\), \(\sigma\)) were found to be crucial to consider when determining the potential for outbreaks of disease. The degree of their significance and direction of correlation was directly dependent on each specific parameter set, highlighting the need to understand the particular pairing scenario occurring in a population. Other significant factors included the rate of sexual contact (\(\psi\)), mpox and co-infection recovery rates (\(\delta _m\), \(\delta _c\)), mpox and HIV transmission rates (\(\tau _m\), \(\tau _h\)), and the HIV death rate (\(d_h\)).

Finally, a scenario analysis was performed in order to understand the ways in which varying pair formation and dissociation rates can impact the dynamics of disease spread in the Canadian gbMSM population. Again, a non-monotonic relationship was identified between pair dissolution rate \(\sigma\) and key metrics such as infection case counts and peak values. The pairing model was then compared to Canadian mpox data from early in the 2022 outbreak and found to be a more accurate fit than the model with the instantaneous contact assumption. July 2022 marked the first full month the mpox vaccine availability in Canada, coinciding with the beginning of a decline in cases in the first wave40. Additionally, the gbMSM community responded to the outbreak with several behavioural changes, including reduction in sexual partners and casual sexual contacts around the same time41. These interventions were not accounted for in the model and can explain the difference between the data and pair model after the peak of mpox infections.

Figure 6 generally agrees with overall case data, however only 10% of those cases are being contributed through co-infections despite 30% of mpox cases in Canada reporting living with HIV42. While a lack of co-infection segregation in case data makes this co-infection disparity hard to robustly investigate, there could be modelling assumptions hindering the agreement. Even though HIV transmissibility was decreased to account for the lack of ARTs in the model, ART coverage is significant in Canada30. For the initial stages of the outbreak, this seems to be an appropriate assumption37. However, not distinguishing between treated and untreated individuals will eventually lead to overestimation of HIV cases. The model also assumes uniform mixing and monogamous pairing, which neglects scenarios of behavioural heterogeneity.

There are various extensions that could be implemented in future work to better align with empirical data. For example, one could distinguish between high risk and low risk individuals and incorporate concurrent relationships in deterministic models of pair formation43,44. It has been suggested that a small group of high risk individuals served as drivers of the 2022 outbreak, and so a model that can differentiate between such groups may lead to more accurate predictive results45,46. However, this added complexity would come at the cost of increased difficulty in analysis due a large model size.

Parameters were taken from literature followed by a sensitivity analysis to understand the impact of these assumptions. While the empirical agreement with overall case counts in the absence of data fitting is encouraging, we do not have robust estimates on parameter confidence or intervals. This is, in part, due to a lack of data informing partnerships and co-infection which limited the ability to identify model parameters. The sensitivity analysis was motivated to mitigate data gaps by assessing the impact of parameter assumption on model outcome. While the effects of variation of some key parameters was determined to be insignificant (eg. increased susceptibility to mpox due to HIV and co-infection death rates), uncertainty in other parameters limits the interpretation of quantitative results.

Our findings have demonstrated that considering behavioural factors is important if we wish to better understand and predict how diseases transmitted through prolonged, close contact spread within a population. In particular, our results show the complexity involved in addressing such diseases in a public health capacity. The use of a pair formation structure revealed that increasing the time an individual spends single is always going to decrease disease spread. However, increasing the time one spends in a relationship may or may not be helpful, and we must additionally be aware of the population’s HIV status. The specific context and characteristics of the population must be carefully considered before implementing interventions targeting behavioural patterns.

Data Availability

All data and code is available publicly at the link https://github.com/smarques01/HIV-mpox-co-infection-with-pair-formation.git.

References

WHO. WHO Director-General Declares mpox Outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (World Health Organization, 2024).

Lai, C. C. et al. Monkeypox: An emerging global threat during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 55, 787–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2022.07.004 (2022).

Hong, C. Mpox on reddit: A thematic analysis of online posts on mpox on a social media platform among key populations. J. Urban Health https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-023-00773-4 (2023).

CDC. About mpox (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024).

Likos, A. M. et al. A tale of two clades: Monkeypox viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 86, 2661–2672. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.81215-0 (2005).

CDC. Clade I mpox Outbreak Originating in Central Africa (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2025).

PHAC. Public Health Agency of Canada confirms the first case of clade I mpox in Canada (Canada.ca, 2024).

Karagoz, A. et al. Monkeypox (mpox) virus: Classification, origin, transmission, genome organization, antiviral drugs, and molecular diagnosis. J. Infect. Public Health 16, 531–541 (2023).

Wang, J., Nguyen, L., Volante, V., Daniel, J. & Preuss, C. Mpox: New challenges with the disease. Rising Contagious Diseases: Basics, Management, and Treatments 20–30 (2024).

WHO. Case profile (overall). 2022-24 Mpox (Monkeypox) Outbreak: Global Trends (2024).

CDC. About HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024).

Mitjà, O. et al. Mpox in people with advanced HIV infection: A global case series. The Lancet 401, 939–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(23)00273-8 (2023).

Ortiz-Saavedra, B. et al. Epidemiologic situation of HIV and monkeypox coinfection: A systematic review. Vaccines 11, 246 (2023).

Bhunu, C. P., Mushayabasa, S. & Hyman, J. M. Modelling HIV/AIDS and monkeypox co-infection. Appl. Math. Comput. 218, 9504–9518 (2012).

Marcus, O. I., Augustine, A. & Jonathan, T. A co-infection model for monkeypox and HIV/AIDS: Sensitivity and bifurcation analyses. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 30, 351–368 (2024).

Omame, A. et al. Understanding the impact of HIV on mpox transmission in an MSM population: A mathematical modeling study. Infect. Dis. Model. 9, 1117–1137. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4793888 (2024).

Peace, O. O., Godwin, O. A. & Bolaji, B. A compartmental deterministic epidemiological model with non-linear differential equations for analyzing the co-infection dynamics between COVID-19, HIV, and monkeypox diseases. Healthc. Anal. 2024, 100311 (2024).

Betti, M. I., Farrell, L. & Heffernan, J. A pair formation model with recovery: Application to mpox. Epidemics 44, 100693 (2023).

Kretzschmar, M. & Dietz, K. The effect of pair formation and variable infectivity on the spread of an infection without recovery. Math. Biosci. 148, 83–113 (1998).

Kretzschmar, M. & Heijne, J. C. M. Pair formation models for sexually transmitted infections: A primer. Infect. Dis. Model. 2, 368–378 (2017).

Castillo-Chavez, C., Huang, W. & Li, J. On the existence of stable pairing distributions. J. Math. Biol. 34, 413–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00167942 (1996).

Hadeler, K. P. Pair formation in age-structured populations. Acta Appl. Math. 14, 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00046676 (1989).

Schmitz, S. F. H. & Castillo-Chavez, C. A note on pair-formation functions. Math. Comput. Model. 31, 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-7177(00)00025-x (2000).

Heffernan, J., Smith, R. & Wahl, L. Perspectives on the basic reproductive ratio. J. R. Soc. Interface 2, 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2005.0042 (2005).

Driessche, P. & Watmough, J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 180, 29–48 (2002).

Mitchell, C. & Kribs, C. Invasion reproductive numbers for periodic epidemic models. Infect. Dis. Model. 4, 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idm.2019.04.002 (2019).

Fauci, A. S., Pantaleo, G., Stanley, S. & Weissman, D. Immunopathogenic mechanisms of HIV infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 124, 654–663 (1996).

HIV.gov. What are HIV and AIDS? (2023).

Standford Medicine. Risk of exposure to HIV/AIDS. Accessed: 2024-09-16 (2024).

PHAC. Canada’s Progress Towards Ending the HIV Epidemic (Government of Canada, 2024).

O’Shea, J. et al. Prolonged mpox disease in people with advanced HIV: Characterization of mpox skin lesions. J. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiad532 (2023).

S., Y. et al. Clinical features and viral load variations of Mpox: A retrospective study in Chongqing, China. BMC Infect. Dis. (2024).

Marino, S., Hogue, I. B., Ray, C. J. & Kirschner, D. E. A methodology for performing global uncertainty and sensitivity analysis in systems biology. J. Theor. Biol. 254, 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.04.011 (2008).

Challacombe, L. CATIE FACT SHEET: The epidemiology of HIV in gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. CATIE (2018).

Sorge, J. et al. Estimation of the population size of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Canada, 2020. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 48, 465–476. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v49i1112a02 (2023).

Mosley, T. et al. Trends in awareness and use of HIV prep among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada 2012–2016. AIDS Behav. 22, 3550–3565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2026-4 (2018).

Lima, V. D. et al. Longitudinal evolution of the HIV effective reproduction number following sequential expansion of treatment as prevention and pre-exposure prophylaxis in British Columbia, Canada: A population-level programme evaluation. Lancet HIV 11, e461–e469. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3018(24)00094-8 (2024).

Yang, Z. Monkeypox: A potential global threat?. J. Med. Virol. 94, 4034–4036. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27884 (2022).

Kwok, K. O., Wei, W. I., Tang, A., Wong, S. Y. & Tang, J. W. Estimation of local transmissibility in the early phase of monkeypox epidemic in 2022. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2022.06.025 (2022).

PHAC. Summary of National Advisory Committee on Immunization rapid response of June 10, 2022. NACI updated monkeypox immunization statement, June 10, 2022: Summary (2022).

Delaney, K. P. et al. Strategies adopted by gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men to prevent monkeypox virus transmission – United States, August 2022. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 71, 1126–1130. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7135e1 (2022).

PHAC. Epidemiological summary report: 2022-2023 mpox outbreak in Canada (2024).

Powers, K. A. et al. The role of acute and early HIV infection in the spread of HIV and implications for transmission prevention strategies in Lilongwe, Malawi: A modelling study. The Lancet 378, 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60842-8 (2011).

Xiridou, M., Geskus, R., Wit, J., Coutinho, R. & Kretzschmar, M. The contribution of steady and casual partnerships to the incidence of hiv infection among homosexual men in amsterdam. AIDS 17, 1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-200305020-00012 (2003).

WHO. Perceptions of Monkeypox from Those Most at Risk: Men Who Have Sex with Men Having Multiple Sexual Partners (World Health Organization, 2022).

Guzzetta, G. et al. The decline of the 2022 italian mpox epidemic: Role of behavior changes and control strategies. Nat. Commun. 15, 2283 (2024).

Xiridou, M. et al. The fading of the MPOX outbreak among men who have sex with men: A mathematical modelling study. J. Infect. Dis. (2023).

CDC. Risk of clade 1 mpox outbreaks among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the United States. Accessed: 2024-09-16 (2024).

PHAC. Rapid risk assessment: Clade 1 mpox virus outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, public health implications for Canada (2024).

WHO. Mpox. Accessed: 2024-09-16 (2023).

Griensven, F. et al. Sex frequency and sex planning among men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Thailand: Implications for pre-and post-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 13, 13–13 (2010).

Acknowledgements

S.M.M. acknowledges support from a Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) Trainee Scholarship. I.R.M. acknowledges support from a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant RGPIN-2025-06301. I.R.M. and B.N. acknowledge support from a Team Grant: Mpox and zoonotic threats - Public health.

Funding

This research is supported through the Discovery Grant program from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (I.R.M., B.N.), a Team Grant: Mpox and zoonotic threats - Public Health from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (I.R.M., B.N.) and from the Canadian Immunization Research Network (S.M.M.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.M., J.R.L., B.N., and I.R.M. designed research; S.M.M. and J.R.L. performed research; S.M.M. performed simulations, analytic calculations, and created visualizations; S.M.M. and J.R.L. wrote the paper; and S.M.M., J.R.L., B.N., and I.R.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Machado-Marques, S., Romero-Leiton, J.P., Nasri, B. et al. Considering the effects of pair formation dynamics on mpox and HIV co-infection in the gbMSM community. Sci Rep 15, 36028 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20039-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20039-0