Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disease frequently accompanied by sleep disorders. Conventional insomnia interventions are often unsuitable for ALS patients due to cognitive and respiratory impairments. There is a lack of targeted studies addressing sleep-related issues using multifactorial analyses specific to this group. This cross-sectional study included 266 ALS patients at the Motor Neuron Disease Rehabilitation and Treatment Center of Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Participants were evaluated using tools like the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R). Regression models identified factors affecting sleep disorders and quality. Patients with sleep disorders were more likely to have non-motor symptoms like anxiety, depression, pain, and excessive daytime sleepiness compared to those without. Fatigue severity and anxiety levels were identified as independent influencing factors of sleep disorders. Additionally, fatigue, anxiety, pain intensity, and disease progression rate were significantly linked to sleep quality. This study is the first comprehensive analysis of sleep-related factors in Chinese ALS patients, highlighting the crucial roles of fatigue, anxiety, pain, and disease progression rate. It provides a basis for future personalized, non-pharmacological interventions tailored to the specific needs of ALS patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a rare and fatal neurodegenerative disease primarily characterized by progressive muscle atrophy, motor dysfunction, and a variety of non-motor symptoms. The pathological hallmark of ALS is the selective degeneration of both upper and lower motor neurons, which ultimately leads to death, most commonly as a result of respiratory failure.1,2,3. Despite significant advances in understanding its pathogenesis in recent years, no curative treatment is currently available. Current therapeutic strategies are primarily supportive, focusing on symptom management to alleviate discomfort, slow disease progression, and improve patients’ quality of life2.

Sleep disorders represent some of the most prevalent non-motor symptoms associated with ALS, occurring at significantly higher rates than in the general population4. Research indicates that approximately 63% of individuals with ALS experience sleep disorders, in contrast to 37% of healthy controls5. These disturbances not only impair subjective well-being and quality of life but may also accelerate disease progression and complicate comprehensive disease management. A study by Li et al. found that patients with poor sleep quality exhibited more rapid respiratory decline at the time of diagnosis6. Consequently, the early identification and management of sleep disorders may contribute to decelerating ALS progression and enhancing patients’ quality of life.

In the general population, the primary treatments for insomnia include cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) and pharmacological interventions. CBT-I enhances sleep quality by modifying maladaptive sleep behaviors and alleviating anxiety. Common pharmacological options include benzodiazepines, non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, and certain antidepressants7. However, in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), early sleep disturbances may aggravate cognitive impairment8,9. Nocturnal intermittent hypoxia can induce oxidative stress, which impairs synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and consequently disrupts memory consolidation, attention, and executive functioning. Moreover, sleep fragmentation and nocturnal hypercapnia further impair memory performance, accelerate cognitive decline, and contribute to excessive daytime sleepiness, reduced attention span, and slower information processing. These cognitive deficits significantly compromise daily functioning and present substantial challenges to the effective implementation of CBT-I10. In addition, progressive respiratory muscle atrophy in ALS leads to ventilatory insufficiency, which increases the risk of sedative-induced respiratory depression and may ultimately precipitate or exacerbate respiratory failure. Therefore, conventional insomnia treatments are often unsuitable for widespread application in this patient population.

Therefore, a comprehensive investigation of the factors contributing to sleep disorders in patients with ALS is crucial for informing the development of safe and feasible individualized intervention strategies. This study aimed to identify the key determinants of sleep quality in individuals with ALS, thereby providing a theoretical basis and strategic guidance for the future development of non-pharmacological interventions tailored to the context of respiratory and communication impairments.

Method

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Ethics approval number: HBZY2024-C38-01). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians. The study was conducted in full compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

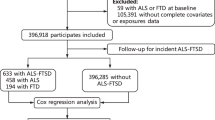

Study participants

Inclusion criteria

Between January 2022 and January 2025, a cohort of consecutive patients diagnosed with ALS and receiving treatment at the Motor Neuron Disease Rehabilitation and Treatment Center of Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine were enrolled in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a confirmed diagnosis of ALS in accordance with the 2020 International Gold Coast Criteria; (2) clinical staging between stages 1 and 3 as per the London criteria, with no prior history of gastrostomy, continuous 24-h non-invasive ventilation (NIV), or tracheostomy; (3) voluntary participation with the provision of signed informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

(1) A history of severe sleep disorders; (2) Coexisting severe chronic respiratory or cardiac diseases; (3) Use of psychoactive medications within the past six weeks; (4) Cognitive impairments preventing accurate comprehension of questionnaire items.

General data assessment

Demographic data included age, sex, smoking history, alcohol consumption, site of disease onset, disease duration, years of education (high school or below, junior college, university or above), marital status (married, divorced, or single), employment status (full-time employed or retired), and monthly household income (5000 RMB or ≥ 5000 RMB).

Clinical data assessment

All scale-based assessments were conducted by trained physicians from the Motor Neuron Disease Rehabilitation and Treatment Center at Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Disease progression rate was calculated as:[(48 − baseline ALSFRS-R score)/48 × 100%]11.

Sleep disorders assessment: Sleep disorders were assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which provides a comprehensive evaluation of sleep quality in ALS patients. The PSQI is a self-reported questionnaire that evaluates sleep over the past month across seven domains: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disorder, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction . It consists of 19 self-rated items, each domain scored from 0 to 3, for a total score ranging from 0 to 21. This standardized tool has demonstrated adequate validity and reliability in various populations, including ALS patients, and can be used for longitudinal assessment of sleep quality12,13. A total score greater than 5 indicates poor sleep quality.

Disease severity assessment: Disease severity was assessed using the revised ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS-R), which evaluates physical function and disease progression in ALS patients14,15. This instrument includes 12 items covering bulbar function, limb mobility, respiratory function, and activities of daily living. Each item is scored based on functional performance, with total scores ranging from 0 to 48; higher scores indicate better physical function and daily living ability.

Daytime sleepiness assessment: Daytime sleepiness was assessed using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), a widely used instrument to evaluate excessive daytime sleepiness in ALS patients16. The ESS consists of eight items, each scored from 0 to 3, with a total score ranging from 0 to 24. A total ESS score ≥ 10 suggests significant daytime sleepiness, while a score ≥ 15 indicates severe somnolence.

Fatigue condition assessment: Fatigue was evaluated using the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)17, which includes nine items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree), with total scores ranging from 9 to 63. Scores ≥ 36 indicate clinically significant fatigue requiring intervention.

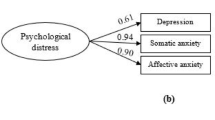

Anxiety and depression assessment: Anxiety and depression are critical factors affecting the quality of life in ALS patients18,19. Therefore, anxiety and depressive symptoms were evaluated using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)18,19. The HARS comprises 14 items, each scored from 0 to 4; a total score > 7 indicates the presence of anxiety symptoms. The HDRS includes 17 items, each scored from 0 to 4, with a total score > 7 suggesting depressive symptoms.

Pain assessment: Pain intensity over the past 30 days was evaluated using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS)20. The VAS is a self-reported tool in which respondents are presented with a numeric rating scale and asked to indicate their pain level on a continuum from 0 to 10, where 0 represents no pain and 10 represents the worst imaginable pain. A VAS score of ≥ 4 was considered indicative of moderate to severe pain, while a score < 4 indicated mild pain.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.3). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was employed to assess the normality of baseline characteristics and clinical variables. Continuous variables that followed a normal distribution were described using the mean and standard deviation (SD). Non-normally distributed continuous variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The independent samples t-test was used to compare continuous variables with normal distribution between two groups; the Mann–Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed continuous variables; the chi-square test was used to analyze differences between categorical variables in the two groups.

To investigate factors associated with sleep disorders, the presence of sleep disorders was treated as a binary outcome variable. Univariate logistic regression was performed to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Variables with a P-value < 0.05 in univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate logistic regression model to identify independent risk factors. Model fit was assessed, and multicollinearity was examined using the variance inflation factor (VIF).

Subsequently, to further investigate factors influencing sleep quality, the total score of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used as a continuous outcome variable. Univariate linear regression was first conducted, and variables with a P-value< 0.05 were included in a multivariable stepwise linear regression model. The model was tested for assumptions including linearity, independence of residuals, homoscedasticity, and normality to ensure analytical rigor. A two-tailed P-value< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

Baseline data characteristics

A total of 266 patients with ALS were enrolled in this study, of whom 163 were male and 103 were female, with a mean age of 54 years and a mean disease duration of 17.44 months. Among them, 176 patients (66.16%) reported sleep disorders, including 103 males (58.52%) and 73 females (41.48%). No significant differences were observed between ALS patients with and without sleep disorders in terms of ALSFRS-R Bulbar (ALSFRS-RB), ESS, FVC, disease duration, education level, caregiver status, working status, region of onset, smoking history, drinking history, or sex (P > 0.05) (refer to Table 1).

However, compared to ALS patients without sleep disorders, those with sleep disorders demonstrated lower scores on the on the ALSFRS-R Limb (ALSFRS-RL), ALSFRS-R Respiratory (ALSFRS-RR), and overall ALSFRS-R, while exhibiting higher scores on the FSS, VAS, HARS, and HDRS scores. Additionally, patients with sleep disorders exhibited more rapid disease progression and were of an older age (refer to Table 2).

Logistic regression analysis of sleep disorders in patients with ALS

Using the presence of sleep disorders (PSQI> 5) as the dependent variable, this study included variables such as the FSS, VAS, HARS, HDRS, ALSFRS-RL, ALSFRS-RR, Age and disease progression rate in univariate binary logistic regression analyses, with univariate binary logistic regression results detailed in Supplementary Table 1. Variables that achieved a significance level of P < 0.05 in the univariate analyses were subsequently included in a multivariate logistic regression model. Predictor variables were selected using a bidirectional stepwise regression method. The findings revealed that anxiety levels (as measured by the HARS score) and fatigue severity (as measured by the FSS score) were independent risk factors for sleep disorders in patients with ALS (refer to Table 3).

Linear regression analysis of sleep quality

Utilizing the total PSQI score as a continuous dependent variable, further univariate linear regression analyses were conducted to explore potential clinical correlates of sleep quality. The variables included ALSFRS-RB, ESS score, disease duration and FVC in addition to the previously described factors. Detailed results of the univariate regression are presented in Supplementary Table 2. Variables with P-values < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate stepwise linear regression model. The results indicated that FSS score, VAS score, HARS score and disease progression rate were the primary factors influencing sleep quality in patients with ALS, as presented in Table 4. Collinearity analysis indicated that all VIFs were below 10, as shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate factors associated with sleep disorders in patients with ALS. The results revealed that, compared with patients without sleep disorders, those with such issues were more likely to exhibit non-motor symptoms such as anxiety, depression, pain, and excessive daytime sleepiness. Multivariate logistic and linear regression analyses identified fatigue severity and anxiety levels as independent predictors of both the presence of sleep disorders and overall sleep quality in patients with ALS. Additionally, linear regression analysis demonstrated that pain intensity and disease progression rate were significantly associated with the severity of sleep disturbances.

Anxiety may influence sleep in ALS patients through multiple biological and psychological mechanisms. First, the progressive and incurable nature of ALS may induce persistent anxiety, which in turn activates the brain’s fear and salience networks21, leading to hyperarousal, difficulty relaxing, and impaired sleep initiation22. Second, anxiety may alter the levels of several neurotransmitters involved in sleep regulation, including adenosine, gamma-aminobutyric acid, dopamine, and serotonin, thereby disrupting sleep architecture23. Furthermore, anxiety may elevate cortisol levels and activate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, which disturbs circadian rhythm and impairs the initiation and maintenance of deep sleep24,25.

Fatigue is a prevalent symptom among patients with ALS and is significantly associated with sleep disorders. In ALS, fatigue can be categorized into physical and mental components. Physically, fatigue primarily results from muscle weakness and increased energy expenditure due to the degeneration of motor neurons, manifesting as progressive muscular decline that severely restricts daily functioning.. Impaired motor abilities often hinder patients from adjusting their posture or finding a comfortable sleeping position, leading to persistent physical discomfort that markedly compromises sleep quality.26. Mentally, fatigue arises from increased cognitive load and emotional stress, which may disrupt central nervous system function, diminish the occurrence of deep sleep stages, and further exacerbate sleep impairment27,28.

Higher VAS scores indicate poorer sleep quality in ALS patients. ALS patients often experience muscle spasms, positional discomfort, and chronic pain, primarily arising from muscle cramps or prolonged static posture, especially in skeletal and joint regions. As the disease progresses, muscle atrophy renders these areas more susceptible to compression, thereby inducing persistent pain29, Muscle cramps in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are primarily attributed to the involvement of upper motor neurons (UMNs), which represents a hallmark pathological feature of the disease30. Dysfunction of UMNs results in heightened tendon reflexes and increased muscle tone, making patients more susceptible to nocturnal cramps. These sustained or intermittent muscle contractions intensify local tissue ischemia and metabolic stress, which in turn sensitize nociceptors and elicit spastic pain31,32. Such pain is often accompanied by soft tissue traction discomfort and severely disrupts sleep continuity. Clinically, this is manifested by prolonged sleep latency, frequent nighttime awakenings, decreased sleep efficiency, and fragmented sleep architecture. These nocturnal disturbances greatly impair daytime alertness and contribute to excessive daytime sleepiness, reduced attention, and executive dysfunction33,34,35,36. A deeper understanding of the multifaceted nature of pain and its impact on sleep can inform more effective intervention strategies, thereby improving the quality of life for ALS patients.

Disease progression rate in ALS is negatively correlated with sleep quality. Patients experiencing more rapid disease progression are more susceptible to severe sleep disturbances.. Accelerated progression leads to greater diaphragmatic and intercostal muscle weakness, which increases both the incidence and severity of nocturnal hypoventilation and sleep-related breathing disorders, thereby substantially reducing overall sleep efficiency and quality34,35. In addition, faster disease progression has been associated with more severe hypothalamic dysfunction., The hypothalamus, a critical regulator of the sleep–wake cycle, has been shown to undergo both atrophy and pathological alterations in ALS36,37. During periods of rapid disease progression, neurotoxic protein accumulation may accelerate structural and functional damage in the hypothalamus, further impairing its regulatory role in sleep and contributing to continued deterioration in sleep quality38.

In addition to the factors identified in this study, emerging evidence indicates that dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system and dysregulation of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) may constitute key mechanisms underlying sleep disturbances in patients with ALS39. Although ALS has traditionally been regarded as a disease that primarily affects motor neurons, growing evidence now supports the significant involvement of sensory and autonomic pathways40. In particular, an imbalance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity has been frequently observed. Studies have shown that even during the early stages of ALS, patients may exhibit impaired cardiovascular autonomic regulation, including elevated resting heart rate, reduced heart rate variability (HRV), and attenuated baroreceptor reflexes. Such autonomic dysfunction can directly disrupt the sleep–wake cycle. Compared with healthy individuals, ALS patients demonstrate markedly lower nocturnal HRV and significant disruptions in sleep architecture, including reduced total sleep time, decreased sleep efficiency, increased frequency of nighttime awakenings, a lower proportion of deep sleep, and shortened REM sleep duration41,42. These findings underscore a strong link between autonomic dysregulation and impaired sleep quality in ALS43.

Moreover, the ECS plays a critical role in regulating sleep–wake homeostasis. Through its endogenous ligands, the ECS modulates the balance between sleep and arousal within the central nervous system. Several studies suggest that the ECS is essential for maintaining a stable circadian rhythm and normal sleep structure44,45. For example, deletion of cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) leads to significant reductions in slow-wave sleep and prolonged periods of wakefulness, emphasizing its functional relevance. Additionally, the ECS interacts with the hypothalamic–melatonin axis and circadian clock genes to coordinate physiological sleep rhythms46. Under pathological conditions, ECS dysfunction may exacerbate sleep fragmentation and insomnia. Furthermore, by promoting neuroinflammation and metabolic dysregulation, impaired ECS signaling may aggravate the overall clinical burden in patients with ALS39.

This study has several notable strengths. First, a total of 266 patients with ALS treated at the Motor Neuron Disease Center of Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine were recruited. Given the rarity of ALS, this sample size provides adequate representativeness. All assessments were conducted by trained professionals using standardized instruments, ensuring data reliability and consistency. Second, this is the first systematic study in China to investigate factors associated with sleep disorders in ALS patients. In addition to traditional variables (pain, respiratory function, disease severity), we included psychological and behavioral factors (anxiety, depression, fatigue, daytime sleepiness) to provide a comprehensive, multidimensional understanding of potential mechanisms underlying sleep disturbances.

However, this study also has limitations. First, the cross-sectional design reveals only associations; future longitudinal cohort studies are needed to verify the impact of risk factors such as fatigue and anxiety on ALS prognosis and sleep disorder progression, thereby providing more robust evidence. Second, only patients in clinical stages 1 to 3 were included, excluding those in advanced stages (stages 4–5). This may limit the applicability of findings to late-stage patients and may not fully reflect sleep disorder characteristics across all disease stages. Future studies should broaden inclusion criteria to enhance representativeness across all disease stages. Finally, this study primarily relied on patient-reported measures to evaluate sleep quality, anxiety, and fatigue, which are inherently vulnerable to recall bias, common method variance, and self-reporting tendencies. Moreover, individual disease burden and current emotional status may systematically influence subjective responses, thereby introducing measurement error and residual confounding. These factors may compromise the validity of variable associations and limit both the objectivity and generalizability of the findings.In addition, respiratory impairment in ALS often begins during the early nocturnal period, typically manifesting as REM sleep-related hypoventilation, intermittent nocturnal hypoxemia, and nocturnal hypercapnia. These subtle ventilatory abnormalities often precede detectable changes in conventional daytime pulmonary function tests. However, standard self-report instruments lack the sensitivity to capture such physiological disruptions, increasing the risk of underdetection.To improve the accuracy and reliability of future research findings, objective sleep-monitoring tools should be integrated alongside existing subjective questionnaires. This multimodal approach would enable earlier and more comprehensive identification of disrupted sleep architecture and respiratory dysfunction in ALS, thereby providing a more robust foundation for developing precision-targeted interventions.

This study identified several key factors associated with sleep disturbances in patients with ALS, including anxiety, fatigue, chronic pain, and disease progression rate. Future intervention strategies should be tailored to the unique functional limitations of ALS patients, with particular attention to those experiencing speech impairments and restricted motor abilities. Locally adaptable, feasible, and high-adherence interventions are needed.

To address anxiety, simplified emotional regulation interventions should be developed to accommodate limitations in communication and cognitive function. Potential approaches include adapted CBT, emotional support groups, and mindfulness-based techniques, complemented by digital tools to enhance accessibility and adherence. For fatigue, standardized objective assessment criteria should be established. Interventions should integrate circadian rhythm optimization, energy management, and daily living modifications to mitigate its disruptive effects on sleep architecture. Chronic pain management should employ a comprehensive strategy, including positional adjustments, rehabilitation therapy, and non-pharmacological analgesia, focusing on optimizing nocturnal posture and individualized care. For patients with rapid disease progression, dynamic monitoring of respiratory function and the establishment of early-warning mechanisms should be prioritized. Attention should also be given to potential degeneration of central regulatory systems, such as hypothalamic function. Due to the absence of specific curative therapies for autonomic dysfunction, clinical management in ALS primarily focuses on multidisciplinary care and symptomatic relief, with the overarching aim of improving patients’ quality of life47,48. In clinical settings, a systematic evaluation of both autonomic and sensory symptoms should be incorporated into routine ALS care, and tailored intervention strategies should be applied accordingly. For symptoms arising from autonomic imbalance, anticholinergic agents may offer symptomatic benefits. For sensory disturbances such as muscle cramps, chronic pain, and paresthesia, a combination of muscle relaxants, analgesics, physical therapy, and assistive devices can be employed to alleviate the overall symptom burden35. Importantly, patients with ALS may present with increased sympathetic activity during the early stages of the disease, which tends to shift toward reduced sympathetic tone in the later stages. This pattern suggests that autonomic dysfunction may persist throughout the disease course and could potentially interact bidirectionally with motor neuron degeneration. Therefore, future research should aim to elucidate the role of autonomic imbalance in the pathogenesis of ALS, with particular emphasis on the disrupted regulation of sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways.

The identification of novel biomarkers also represents a key priority for future studies. Recent evidence indicates that lipidomic profiling of the endocannabinoidome (eCBome) in blood samples can categorize patients into distinct molecular subtypes39. These subtypes have been found to correlate with disease activity and survival outcomes, offering opportunities for prognostic stratification. Building on this framework, combining molecular subtypes with sleep phenotypes may allow for early identification of ALS patients who are at high risk of sleep disturbances, thus providing a window for early intervention.Furthermore, integrating biomarkers and objective sleep parameters into unified predictive models could help quantify the prognostic impact of sleep disruptions and contribute to the development of individualized risk prediction strategies. Future studies should adopt an integrative approach that merges clinical practice with laboratory-based research. This would enable the simultaneous collection of blood-based multi-omics data and objective sleep monitoring indicators, thereby enhancing the understanding of the biological heterogeneity of sleep disturbances in ALS and providing a more solid foundation for precision medicine and personalized disease management.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Fang, H. et al. Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23(4), 2324–2332. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.14170 (2019).

Fatemeh, G. et al. Effect of melatonin supplementation on sleep quality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Neurol. 269(1), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10381-w (2022).

Davies, S. K. et al. Effect of sleep deprivation on the human metabolome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111(29), 10761–10766. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1402663111 (2014).

Sun, X. et al. Study on sleep-wake disorders in patients with genetic and non-genetic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2020-324544 (2020).

Diaz-Abad, M. et al. Poor sleep quality in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis at the time of diagnosis. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 20(2), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1097/CND.0000000000000234 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Sleep disturbances as a potential risk factor for deterioration of respiratory function in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 26(5), 754–760. https://doi.org/10.4103/aian.aian_276_23 (2023).

Park, H. J. et al. Association between sleep disorder and panic disorder in South Korea: Nationwide nested case-control study of data from 2004 to 2013. Psychiatry Res. 260, 286–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.076 (2018).

Strong, M. J. et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal spectrum disorder (ALS-FTSD): Revised diagnostic criteria. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener 18(3–4), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2016.1267768 (2017).

Park, S. et al. Nocturnal hypoxia in ALS is related to cognitive dysfunction and can occur as clusters of desaturations. PLoS ONE 8(9), e75324. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075324 (2013).

Spisto, M. et al. Identifying mild behavioral and neurocognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MBNI-ALS) provides key prognostic insights. Eur. J. Neurol. 32(5), e70171. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.70171 (2025).

Franchignoni, F. et al. Evidence of multidimensionality in the ALSFRS-R Scale: A critical appraisal on its measurement properties using Rasch analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84(12), 1340–1345. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2012-304701 (2013).

Doi, Y. et al. Psychometric assessment of subjective sleep quality using the Japanese version of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI-J) in psychiatric disordered and control subjects. Psychiatry Res. 97, 165–172 (2000).

Backhaus, J. et al. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in primary insomnia. J. Psychosom. Res. 53(3), 737–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00330-6 (2002).

Hillel, A. D. et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis severity scale. Neuroepidemiology 8(3), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1159/000110176 (1989).

Cedarbaum, J. M. et al. The ALSFRS-R: A revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS study group (phase III). J. Neurol. Sci. 169(1–2), 13–21 (1999).

Sap-Anan, N. et al. The epworth sleepiness scale in epilepsy: Internal consistency and disease-related associations. Epilepsy Behav. 121(Pt A), 108099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108099 (2021).

Wang, M. Y. et al. Cultural adaptation and validation of the Chinese version of the fatigue severity scale in patients with major depressive disorder and nondepressive people. Qual. Life Res. 25(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1056-x (2016).

Rodriguez-Seijas, C. et al. A comparison of the dimensionality of the Hamilton rating scale for anxiety and the DSM-5 anxious-distress specifier interview. Psychiatry Res. 284, 112788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112788 (2020).

Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 23(1), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 (1960).

An, R. et al. The evaluation of pain with nociceptive and neuropathic characteristics from three different perspectives in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: A case controlled observational study in southwestern China. Neural. Plast. 2021, 5537892. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5537892 (2021).

Li, C. et al. Dynamic functional abnormalities in generalized anxiety disorders and their increased network segregation of a hyperarousal brain state modulated by insomnia. J. Affect Disord. 246, 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.079 (2019).

Seo, J. et al. Partial and total sleep deprivation interferes with neural correlates of consolidation of fear extinction memory. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 6(3), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.09.013 (2021).

Elmenhorst, D. et al. Recovery sleep after extended wakefulness restores elevated A(1) adenosine receptor availability in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114(16), 4243–4248. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1614677114 (2017).

Monachelli, G. G. et al. Progesterone and cortisol levels in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (sALS): correlation with prognostic factors. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 6(1), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1515/HMBCI.2011.006 (2011).

Spataro, R. et al. Plasma cortisol level in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 358(1–2), 282–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2015.09.011 (2015).

Chen, J. H. et al. Risk of developing pressure sore in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients—A nationwide cohort study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 32(9), 1589–1596. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14911 (2018).

Baglioni, C. et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J. Affect Disord. 135(1–3), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011 (2011).

Skapinakis, P. et al. Sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms: An investigation of their longitudinal association in a representative sample of the UK general population. Psychol. Med. 43(2), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001055 (2013).

Akerblom, Y. et al. Pain, disease severity and associations with individual quality of life in patients with motor neuron diseases. BMC Palliat. Care 20(1), 154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00848-6 (2021).

Boentert, M. Sleep disturbances in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Current perspectives. Nat. Sci. Sleep 11, 97–111. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S183504 (2019).

Lucia, D. et al. Disorders of sleep and wakefulness in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): A systematic review. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 22(3–4), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2020.1844755 (2021).

Gnoni, V. et al. Hypothalamus and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Potential implications in sleep disorders. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 1193483. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1193483 (2023).

Hurwitz, N. et al. Prevalence of pain in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 22(7–8), 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2021.1892765 (2021).

Rosa, D. et al. Perceived pain in people living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—A scoping review. Nurs. Rep. 14(4), 3023–3039. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040220 (2024).

Kwak, S. Pain in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A narrative review. J. Yeungnam. Med. Sci. 39(3), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.12701/jyms.2022.00332 (2022).

Delpont, B. et al. Clinical features of pain in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A clinical challenge. Rev. Neurol. 175(1–2), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2017.11.009 (2019).

Lechtzin, N. et al. Respiratory measures in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 19(5–6), 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2018.1452945 (2018).

Yan, J. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation significantly improved respiratory failure of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Gut. Microbes 16(1), 2353396. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2024.2353396 (2024).

Dubbioso, R. et al. Circulating endocannabinoidome signatures of disease activity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 31(10), e16400. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.16400 (2024).

Nolano, M. et al. Skin innervation across amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinical stages: New prognostic biomarkers. Brain 147(5), 1740–1750. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awad426 (2024).

Sivathamboo, S. et al. Cardiorespiratory and autonomic function in epileptic seizures: A video-EEG monitoring study. Epilepsy Behav. 111, 107271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107271 (2020).

Congiu, P. et al. Sleep cardiac dysautonomia and EEG oscillations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sleep https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsz164 (2019).

Dubbioso, R. et al. Autonomic dysfunction is associated with disease progression and survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. J. Neurol. 270(10), 4968–4977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-023-11832-w (2023).

Kesner, A. J. & Lovinger, D. M. Cannabinoids, endocannabinoids and sleep. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 13, 125. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2020.00125 (2020).

Fitzgerald, K. C. et al. Dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and risk for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 71(9), 1102–1110. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1214 (2014).

Xue, J. et al. Systematic review/meta-analysis on the role of CB1R regulation in sleep-wake cycle in rats. J. Evid. Based Med. 17(4), 714–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12643 (2024).

Vidovic, M. et al. Current state and future directions in the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12050736 (2023).

Bjelica, B. et al. Non-motor symptoms in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Current state and future directions. J. Neurol. 271(7), 3953–3977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-024-12455-5 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Joint Fund,2023AFD128, 2024AFD279,2025AFD532) and Science and Technology Special Project of State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (GZY-KJS-2025-008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work. JQ: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. YD: Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. JR: Supervision, Data curation. WS: Data curation. WM: Data curation. XD Supervision, Data curation. ZJ: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Wuhan, China, Ethics approval number: HBZY2024-C38-01).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Q., Yang, D., Jiang, R. et al. Analysis of factors influencing sleep disorders in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci Rep 15, 34104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20100-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20100-y