Abstract

Gastric cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality and highlights the need for early detection of gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection, which is a major risk factor. Early non-invasive and convenient diagnostic tools capable of capturing the dynamic molecular alterations during carcinogenesis and HP infection is needed. In this study, we use Raman spectroscopy and machine learning algorithms to detect different gastric lesions and HP infection condition with gastric juice samples. 133 patients from Peking University Third Hospital were involved and categorized into groups based on histopathological diagnosis: early gastric cancer (EGC), dysplasia (DYS), intestinal metaplasia (IM), and chronic superficial gastritis (CSG), with further classification based on HP infection. The stacked machine learning model demonstrated high diagnostic performance, achieving 90% accuracy, 90% sensitivity, and 97% specificity in distinguishing pathological stages, along with 96% accuracy, 96% sensitivity, and 96% specificity in HP detection. The multilayer perceptron (MLP) model based on gastric juice Raman spectroscopy showed excellent discrimination capability, with an AUC of 0.98 for differentiating controls from patients with DYS and EGC. Additionally, Raman spectroscopy achieved an AUC of 0.95 in distinguishing control gastric mucosa from precancerous lesions (IM, DYS) and EGC. The approach offers a rapid, accurate, and minimally invasive diagnostic tool, demonstrating significant potential for clinical application in rapid and accurate detection of precancerous lesions, early gastric cancer, and HP infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer ranks as the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and stands as the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality, underscoring a profound global public health challenge1. Timely and precise detection in the initial stages of gastric cancer is essential for reducing the incidence and mortality rates2. The Correa’s cascade model delineates the multistep progression from normal gastric mucosa to gastric cancer, encompassing stages such as chronic superficial gastritis (CSG), chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG), intestinal metaplasia (IM), dysplasia (DYS), and, ultimately, gastric cancer3. This model underscores the possibility of early diagnosis. Although endoscopic biopsy pathology is widely regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing gastric cancer and precancerous lesions, it comes with notable limitations, including invasiveness, patient discomfort, high costs, and procedural complexity. Serological biomarkers (e.g., pepsinogen I/II ratio, gastrin-17) testing have improved non-invasive risk stratification, yet their sensitivity and specificity for detecting early-stage lesions remain suboptimal4. Imaging modalities and emerging liquid biopsy approaches targeting circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or exosomes show promise but face challenges in cost, technical complexity, and applicability to precancerous stages5,6. Therefore, a significant unmet need lies in developing minimally invasive, convenient for detection, and cost-effective diagnostic tools capable of capturing the dynamic molecular alterations within the gastric microenvironment during carcinogenesis.

Helicobacter pylori (HP), the most significant and preventable risk factor of gastric cancer, is a Class I carcinogen strongly linked not only to gastric cancer but also to various gastrointestinal diseases, including peptic ulcers, atrophic gastritis, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma7. Thus, early detection and timely eradication of HP are pivotal for preventing gastric cancer and related gastrointestinal diseases8. While several diagnostic methods for HP infection currently exist—including serological antibody tests, urea breath tests, stool antigen tests, urease tests9,10 as well as tissue-based immunohistochemical detection —each is hampered by certain limitations, such as suboptimal accuracy and sensitivity, high false-positive rates, and procedural complexity11. These drawbacks highlight the pressing need for a diagnostic approach that is not only simple and cost-effective but also rapid and reliable, thereby enhancing the efficiency and accessibility of HP detection.

Gastric juice, as a proximal biofluid directly reflecting the pathophysiological state of the stomach, holds untapped potential12. It contains a rich repertoire of biomarkers—including proteins, metabolites, nucleic acids, and microbiota-derived components—that may mirror epithelial injury, inflammatory activity, and neoplastic transformation. In this context, the analysis of gastric juice presents a compelling diagnostic alternative. Unlike blood samples, gastric juice can more directly reflect alterations in the gastric mucosa, providing valuable biomarkers for the early detection of gastric cancer and precancerous lesions. Moreover, the current use of a traction line collector also enables minimally invasive gastric juice collection. This study proposes a novel integrative approach leveraging gastric juice analysis to address existing gaps in early detection. By characterizing stage-specific molecular profiles within gastric fluid, we aim to establish a minimally invasive platform for precise risk stratification and timely clinical intervention, ultimately bridging the translational divide between biomarker discovery and actionable diagnostic applications.

Raman spectroscopy as an advanced bioanalytical technique captures spectral information with high spatial resolution at each pixel, enabling qualitative, quantitative, and spatial molecular analysis. By imaging the composition and structure of materials, this technology accurately reveals the biochemical characteristics of biological samples13. Raman spectroscopy has been successfully applied in pathogen detection14,15 and the early diagnosis of various cancers16,17,18. When applied to gastric juice samples, it detects changes in biomolecular components—such as proteins, lipids, and nucleotides—thereby aiding in the diagnosis of HP infection and distinguishing among different pathological stages of gastric mucosa. Raman spectroscopy offers notable advantages with its minimally invasive, rapid, reagent-free, and real-time molecular insight—meets the needs of early diagnosis of gastric cancer19. With advances in Raman spectroscopy and the integration of machine learning algorithms, the accuracy and efficiency of diagnosing gastric cancer, precancerous lesions, and HP infection can be further improved, offering a more reliable diagnostic tool for clinical use.

To date, studies on staging of gastric mucosal lesions and HP diagnosis based on Raman spectral analysis of gastric juice have been limited. Here, we propose a novel, rapid, label-free diagnostic method for precancerous lesions, early gastric cancer (EGC), and HP infection using Raman spectroscopy and machine learning algorithms. In this study, CSG samples serve as controls, while gastric precancerous lesions are classified as IM and DYS based on disease progression. Multiple machine learning algorithms were employed to construct classification models, with a final stacking model achieving remarkable performance in pathological staging, while maintaining equally high diagnostic metrics for HP detection. Notably, the Raman spectroscopy combined with MLP model showed outstanding discriminative power between controls and patients with DYS or EGC. Our study demonstrates that combining machine learning algorithms with Raman spectroscopy of gastric juice offers a novel and reliable tool for rapid and accurate detection of precancerous lesions, early gastric cancer, and HP infection.

Methods

Experimental design and participant enrollment

A total of 133 patients who underwent gastroscopy at Peking University Third Hospital were recruited for this study. All participants provided voluntary consent after being thoroughly briefed on the study details, and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Peking University Third Hospital (No. IRB00006761-M2017414).

Patients were stratified into four groups based on histopathological findings from gastroscopic biopsies, following the 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) classification criteria20: 35 patients in the EGC group, 31 patients in the DYS group, 28 patients in the IM group, and 39 patients in the CSG group. Furthermore, according to the histological WS staining results from biopsies, the patients were further classified into two subgroups according to HP infection status: 27 patients were HP positive, while 106 patients were HP negative. Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining images of four groups of representative gastric tissues are shown in Supplementary Figure.

The final study cohort included 131 patients (after excluding 2 samples with undetectable Raman spectra due to intense fluorescent background), with a mean age of 51.9 years and 53.4% males (70/131). The histopathological distribution was: 38 CSG, 28 IM, 30 DYS, and 35 EGC, with 27 HP + and 104 HP- cases. Comprehensive demographic and clinic-pathological characteristics are detailed in Supplementary table S1 and S2.

Sample collection

Gastric juice samples were collected via suction into sterile containers immediately following endoscope insertion in patients who had fasted for 8–12 h prior to gastroscopy. The gastric juice was first centrifuged at 1,800 rpm (4 °C) for 10 min, followed by a second centrifugation at 15,000 ×g (4 °C) for 30 min to clarify the supernatant.

Raman spectroscopy generation

A 10-µL aliquot of the final gastric juice supernatant was deposited onto a calcium fluoride (CaF₂) low-background Raman substrate and air-dried. Raman spectra were acquired using a WITec alpha 300R confocal Raman microspectrometer (WITec GmbH, Germany) under optimized experimental conditions.

The Raman spectra were collected using a 532 nm laser, 100× microscope objective, 600 gmm-1 grating, 20 mW power, and 3–5 s accumulation time. The spectra range was from 400 to 3200 cm− 1. To reduce noise, an average of three consecutive acquisitions was made at the same sample position. The sample was randomly selected at different locations for Raman spectrum measurement to avoid any bias. Each sample was measured more than 25 spectra for further analysis.

Raman spectroscopy data process and analysis

The raw Raman spectral data were first removed cosmic rays and then smoothed using vector transformation with WItec spectral analysis software. Subsequently, baseline were corrected using a polynomial fitting method21. The averaged spectra were normalized by area and presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Machine-learning algorithm and model

Multiple dimensionality-reduction machine learning algorithms, including t-distributed stochastic neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), principal component analysis (PCA), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), were used to extract the most significant feature peaks from the Raman spectra and to visualize the data in lower dimensions. Machine learning algorithms were applied to classify different groups. The data analysis employed the classifiers such as gate recurrent unit (GRU), multilayer perceptron (MLP), artificial neural network (ANN), gradient boosting (GB), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), random forest (RF), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), logistic regression (LR), quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA) and naive bayes (NB). LSVM denotes a support vector machine using a linear kernel, whereas RSVM denotes a support vector machine using a radial basis function (RBF) kernel. Traditional machine learning models, including SVM, LDA, QDA, RF, GB, KNN, and ANN (single-layer), were optimized using GridSearch (CV = 5), selecting the best hyperparameters (Supplementary table S3), validating the model, and making predictions on the test set. The dataset was split into training (80%) and test (20%) sets using a sample-level stratification strategy to ensure proportional representation of each pathological group. Specifically, samples were first partitioned into training and test subsets while preserving the class distribution. All spectra from a given sample were assigned entirely to either the training or test set to prevent data leakage. For model training, a fivefold cross-validation was performed within the training set, where each fold contained a random subset of samples. Deep learning models, including MLP and GRU, were fine-tuned based on common architectures, with a validation split of 0.2. The training set was also divided into five folds for cross-validation. The batch size was set to 128, with a learning rate of 0.001, and the learning rate was automatically adjusted using ReduceLROnPlateau to enhance training efficiency. After model construction, the model’s discriminatory and predictive performance was evaluated by calculating accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and plotting receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Among the aforementioned machine learning and deep learning models, the four best-performing models from different categories were stacked for prediction. Multi-model stacking significantly improved the model’s performance. After stacking, the prediction for each individual spectrum was determined by majority vote. All machine learning algorithms and model analyses were performed using Python 3.9.

Statistics

Statistical analysis of potential biomarkers between groups was performed using SPSS software. The normality of data distribution for Raman peak intensities was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variances across groups was assessed via Levene’s test. All analyzed spectral peaks met the assumptions of normality (P > 0.05) and equal variance (P > 0.05). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc test was used to assess differences. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study cohort and workflow

The workflow for gastric juice diagnosis based on Raman spectroscopy and machine learning is illustrated in Fig. 1A. Gastric juice was placed on a microscope slide for Raman spectral measurement, which captures chemical molecular components; the data were further analyzed using machine learning algorithms for diagnostic purposes. Pathological feature clustering analysis was performed between controls (CSG), precancerous lesions (IM, DYS), early-stage cancer (EGC), HP+, and HP- (Fig. 1B), focusing on changes across pathological stages and HP infection status to enable rapid and accurate detection. The distribution of HP positivity across the four pathological groups was as follows: 23.8% (10/38) in the CSG group, 14.3% (4/28) in the IM group, 13.3% (4/30) in the DYS group, and 25.7% (9/35) in the EGC group. A chi-square test showed no statistically significant differences in HP positivity rates across these groups (χ2 = 2.967, P = 0.397).

Workflow for gastric juice diagnosis based on Raman spectroscopy and machine learning for gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori (HP). (A) Clinical sample processing and Raman spectral acquisition protocol. (B) Machine learning-enabled diagnostic analysis of Raman spectra for gastric cancer and HP detection.

Gastric juice Raman spectral generation and pathological feature clustering analysis

Bright-field microscopy of unlabeled gastric juice samples showed no significant differences across the four groups (Fig. 2A). A total of 3887 Raman spectra were collected across the four groups, with a spectral resolution of 3.3 cm⁻¹ and a wavenumber range of 300 to 3000 cm⁻¹. Specifically, 1137, 822, 900, and 1028 Raman spectra were collected from the CSG, IM, DYS, and EGC groups, respectively. The average Raman spectra and standard deviations for the four groups were shown in Fig. 2B. While the shapes of the Raman spectra from each group appeared similar, the relative intensities of some Raman peaks differed, which could be further distinguished using machine learning algorithms.

Considering the high dimensionality of the Raman spectra, we applied multivariate dimensionality-reduction algorithms to extract the main features of the spectra and visualize the data in lower dimensions. First, t-SNE was employed to extract the major features of the data with significant differences (Fig. 2C). Subsequently, unsupervised linear dimensionality reduction using PCA was applied to identify the primary directions of variation in the data (Fig. 2D). Through supervised multivariate dimensionality reduction methods: LDA and OPLS-DA, we observed clear classification differences between the CSG, IM, DYS, and EGC groups, indicating that Raman spectroscopy can serve as a potential and precise method for histopathological diagnosis based on gastric juice (Fig. 2E & F).

Collection and analysis of Raman spectra of gastric juice. (A) The representative bright field micrographs of gastric juice. (B) Average curves of the Raman spectra of the four groups. The shaded area of each group was the standard deviation. (C) Multivariate visualization analysis of the Raman spectra by t-SNE. (D) Multivariate dimension-reducing analysis of the Raman spectra by PCA. (E) Scatter plots of the LD contribution from Raman spectral data. (F) Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) of the Raman spectra.

Machine learning analysis of gastric juice Raman spectra to distinguish gastric mucosal lesions

To accurately distinguish and predict different histopathological types through gastric juice sample spectral analysis, we applied machine learning algorithms to process the collected Raman spectral data and assessed their predictive capabilities. 80% of the spectral data were used as the training dataset, with 20% of the spectral data randomly selected as a test set to evaluate classification performance. To achieve optimal diagnostic performance, we employed 12 different machine learning algorithms, including MLP, ANN, GRU, GB, KNN, RF, LSVM, LDA, LR, QDA, NB, and RSVM, to construct classification models (Supplementary table S4). Among these, the MLP algorithm demonstrated the best recognition performance for differentiating gastric mucosal lesions, achieving an accuracy of 78%, sensitivity of 78%, and specificity of 93%.

The top four performing models (MLP, GRU, ANN, and GB) were selected for stacking, and the stacked model demonstrated improved recognition performance, achieving an accuracy of 90%, sensitivity of 90%, and specificity of 97%. The discriminative ability of the stacked model was evaluated using ROC curve (Fig. 3A). The AUC values for CSG, IM, DYS, and EGC were 0.95, 0.91, 0.91, and 0.96, respectively, indicating that the model has good classification performance in diagnosing both precancerous lesions and gastric cancer. The confusion matrix (Fig. 3C) illustrates the predictive performance of the stacked model. The model correctly classified 219 out of 228 control spectra (96.1%), 138 out of 164 IM spectra (84.1%), 151 out of 180 DYS spectra (83.9%), and 196 out of 206 EGC spectra (95.1%). The sensitivities for diagnosing CSG, IM, DYS, and EGC were 96%, 84%, 84%, and 95%, respectively (Table 1). The specificities for CSG, IM, DYS, and EGC diagnosis were 94%, 97%, 99%, and 97%, respectively (Table 1). These findings further strengthen the potential application of gastric juice Raman spectroscopy combined with machine learning algorithms in the identification of different stages of gastric mucosal lesions.

To demonstrated whether the gastric juice Raman spectroscopy could be used to screen the intraepithelialneoplasia (combined DYS and EGC) according to WHO classification. ROC analysis further demonstrated the high diagnostic performance of the MLP model based on gastric juice Raman spectroscopy, which effectively discriminated controls from patients with DYS and EGC, with an AUC of 0.98 (Fig. 3D). The confusion matrix (Fig. 3E) illustrates the predictive performance of the MLP model. Additionally, Fig. 3F and G also demonstrates the performance of Raman spectroscopy in distinguishing control gastric mucosa from precancerous lesions (IM, DYS) and EGC, achieving an AUC value of 0.95.

Taken togetherthe gastric juice Raman spectroscopy combined with machine learning algorithms could discriminate different stages of gastric mucosal lesions and also have good distinguishing effect to distinguish intraepithelialneoplasia, gastric mucosal lesions and gastric cancer.

Diagnostic performance and potential biomarkers of gastric juice Raman spectroscopy in distinguishing gastric mucosal lesions. (A) Machine learning integrated stacking model analysis procedure. (B) ROC curves of the stack model of the gastric juice Raman spectra diagnosing precancerous lesions and gastric cancer. (C) Confusion matrix diagram of Raman spectra prediction of the four gastric histopathological based on the stack model. (D) ROC analysis of MLP model performance in discriminating control from intraepithelial neoplasia (dysplasia, and early gastric cancer) using gastric juice Raman spectroscopy. (E) Confusion matrix diagram of Raman spectra prediction of gastric intraepithelial neoplasia. (F) ROC curves of MLP model performance in discriminating control from gastric lesions (intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and early gastric cancer) using gastric juice Raman spectroscopy. (G) Confusion matrix diagram of Raman spectra prediction of gastric lesions (intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and early gastric cancer).

Identification of potential biomarkers for gastric mucosal lesion diagnosis from gastric juice Raman spectral fingerprints

The Raman spectra could be analyzed to extract biomolecular information, serving as a unique observation feature in the process of disease onset and progression. To demonstrate disease-specific molecular signatures across the continuum of gastric carcinogenesis, we analyzed the distribution of different Raman spectral peaks across the four gastric pathological types. As shown in Fig. 4A, diferential peaks included the vibration of adenine at 717 cm− 1, phenylalanine at 1003 cm− 1, Amide III vibration at 1235 cm− 1, CH3, CH2 wagging (collagen assignment) glucose at 1343 cm− 1, followed by semi-quantitative analysis (Fig. 4B). Notably, progressive increases in adenine and glucose levels (reflected by peaks at 717 cm− 1 and 1343 cm− 1, associated with CH3/CH2 wagging vibrations of collagen) were observed along the pathological sequence from CSG to IM, DYS and EGC. Similarly, phenylalanine levels (1003 cm− 1) exhibited a stepwise elevation across disease progression stages. Conversely, amide III signals (1235 cm− 1) displayed a gradual attenuation from controls through premalignant lesions to EGC.

Spectral characterization and quantitative analysis of gastric lesions by Raman Spectroscopy. (A) Assignment of the characteristic Raman peaks in different gastric histopathological types. (B) The violin plots of Raman normalized quantification intensity based on the characteristic Raman peaks. The results were displayed as mean ± SD. *represents p < 0.05, **represents p < 0.01, ***represents p < 0.001, and ****represents p < 0.0001.

Clustering analysis of Raman spectra from HP positive and negative gastric juice samples

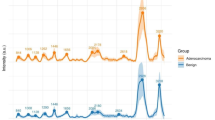

To distinguish HP infection using gastric juice Raman spectroscopy, the study cohort was further divided into two groups based on HP infection status: HP positive(+) and HP negative(-). A total of 806 Raman spectra were collected from the HP + group, and 3081 Raman spectra were collected from the HP- group. The average Raman spectra and standard deviations for each group are shown in Fig. 5A. To assess the differences between gastric juice samples from the two groups, we applied four clustering algorithms—t-SNE, PCA, LDA, and OPLS-DA for data visualization. As shown in Fig. 5B, there is a distinguishable difference between HP + and HP- samples. To better understand the data structure and identify the primary directions of variation, we utilized a PCA plot (Fig. 5C). Additionally, the LDA results revealed a clear classification trend between the Raman spectra of HP + and HP- groups (Fig. 5D).

Raman spectral analysis of gastric juice for HP diagnosis. (A) Average Raman spectra curves of the HP + and HP- groups. The shaded area in each group represents the standard deviation. (B) Multivariate visualization analysis of Raman spectra using Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). (C) Dimensionality reduction of Raman spectra using Principal component analysis (PCA). (D) Dimensionality reduction of Raman spectra using linear discriminant analysis (LDA).

Machine learning analysis of gastric juice Raman spectra to discriminate HP infection

To accurately distinguish and predict HP + and HP- samples, we employed machine learning algorithms to process the collected Raman spectral data and evaluate their predictive capabilities. 80% of the spectral data were used as the training dataset, with 20% of the spectral data randomly selected as a test set to assess classification performance. We constructed classification models using 12 different machine learning algorithms, including MLP, ANN, GRU, GB, KNN, RF, LSVM, LDA, LR, QDA, NB, and RSVM (Supplementary table S5). Among these, the MLP algorithm demonstrated the best discrimination performance in HP diagnosis, with an accuracy of 89%, sensitivity of 81%, and specificity of 81%. The top four models (MLP, GRU, KNN, and GB) were stacked, and the stacked model exhibited improved recognition performance, with an accuracy of 96%, sensitivity of 96%, and specificity of 96%. The classification ability of the stacked model was evaluated using the ROC curve (Fig. 6A). The AUC value for the ROC curve, representing the classification ability of HP + and HP-, was 0.94, suggesting that Raman spectroscopy combined with the stacked model can serve as a potential method for diagnosing HP infection from gastric juice. The confusion matrix (Fig. 6B) provides a visual representation of the predictive capabilities of the stacked model. As shown in Fig. 6B, of the 617 HP- spectra, 606 were correctly classified, and of the 161 HP + spectra, 144 were correctly classified. The sensitivity for HP + and HP- patients was 89% and 98%, respectively (Table 2), and the specificity for HP + and HP- patients was 98% and 89%, respectively (Table 2). These results support the potential application of Raman spectroscopy combined with machine learning algorithms in diagnosing HP infection from gastric juice.

Identification of potential biomarkers for HP diagnosis from gastric juice Raman spectral fingerprints

To identify HP infection-specific molecular signatures, we also analyzed the distribution of different Raman spectral peaks across the HP + and HP- groups. Figure 7A showed the assignment of differential Raman spectral peaks between HP + and HP- groups. Characteristic peaks were identified and semi-quantitatively analyzed (Fig. 7B), including phosphatidylinositol at 415 cm− 1, adenine at 717 cm− 1, nucleic acid at 1576 cm− 1, and CH2 asymmetric stretching vibration at 2930 cm− 1. Notably, the HP + group exhibited significantly higher phosphatidylinositol levels at 415 cm− 1 compared to HP- samples. Furthermore, at 717 cm− 1, elevated adenine levels were detected in the HP + group.

Spectral characterization and quantitative analysis of HP infection by Raman Spectroscopy. (A) Assignment of the characteristic Raman peaks in different HP types. (B) The violin plots of Raman normalized quantification intensity based on the characteristic Raman peaks. The results were displayed as mean ± SD. *represents p < 0.05, **represents p < 0.01, ***represents p < 0.001, and ****represents p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Raman spectroscopy has been utilized in the diagnosis of various tumors and infectious diseases, yet its application in gastric cancer diagnosis have been limited. Our study demonstrates the feasibility of Raman spectroscopy combined with machine learning for minimally invasive diagnosis of early gastric cancer (EGC), premalignant lesions (IM, DYS), and HP infection using gastric juice samples. Gastric juice analysis provides more comprehensive gastric mucosal profiling, eliminates tissue sampling bias, and can be obtained using traction line collector devices. Moreover, by improving the combination of Raman spectroscopy and machine learning modeling, the diagnostic accuracy and specificity of precancerous lesions, early gastric cancer, and HP infection have been significantly enhanced. Particularly noteworthy was the model’s discriminative ability for precancerous lesions (IM, DYS) and EGC (AUC = 0.95) compared to control CAG groups. Therefore, our results indicate that this method is rapid and accurate, with the potential to be integrated into endoscopic systems for future clinical screening assistance.

Although endoscopic biopsy combined with histopathological analysis is regarded as the diagnostic gold standard, it has several limitations, including procedural invasiveness, high operator dependency, and risk of sampling errors. Our diagnostic approach, while utilizing gastroscopy for sample collection, qualifies as minimally invasive due to its avoidance of gastric mucosal biopsy. Unlike traditional invasive methods that require tissue sampling (with associated risks of bleeding, perforation, or infection), gastric juice collection via the endoscope’s traction line during routine examination eliminates the need for additional invasive steps, reducing procedural trauma and patient risk. This distinction positions it as a safer alternative for repeated monitoring, particularly in high-risk cohorts. Compared to narrow-band imaging-enhanced endoscopy, which relies on vascular/structural changes, our approach detects premalignant metabolic shifts at the molecular level, enabling earlier intervention. While tissue-based Raman studies also provide localized molecular insights19, gastric juice Raman spectroscopy integrates biochemical alterations across the entire gastric lumen, capturing field cancerization effects often missed by focal biopsies. A recent study by Si et al. introduced a non-invasive method that combines surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) with machine learning algorithms for accurately diagnosing various stages of gastric diseases, including chronic non-atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia22. However, this study did not include gastric cancer samples, which limited its ability to assess the diagnostic accuracy across all stages of the Correa model22. In our research, by comparing the spectral peaks of gastric juice from CSG, IM, DYS, and EGC patients, this study not only reveals the molecular differences among these lesions but also offers key clinical guidance. Specifically, patients with IM can be monitored regularly, DYS requires endoscopic resection, and EGC treatment depends on specific conditions, involving either endoscopic or surgical intervention23. We used different clustering analysis methods to reduce the dimensionality of high-dimensional data and minimize the influence of intergroup differences on classification results. The clustering results showed that the Raman spectra of gastric juice from the four disease types exhibited excellent clustering performance. Clinically, this differentiation directly informs management: surveillance for IM, endoscopic resection for DYS, and tailored therapy for EGC—decisions previously requiring repeated biopsies. Moreover, building on successful in vivo Raman applications in nasopharyngeal cancer24 and esophageal dysplasia25, our method could be adapted for endoscopic integration. A fiber-optic Raman probe deployed through the endoscope working channel could enable real-time, in situ diagnosis during routine gastroscopy, this may revolutionize gastric cancer screening paradigms.

In addition to distinguishing the different stages of gastric mucosal lesions, we also explored the detection of HP infection. Currently, the urea breath test is widely used for HP infection screening at the population level, but it has a relatively high false-positive rate and is influenced by many other factors such as food and medications26. The fecal antigen test can be used for routine HP infection diagnosis but requires a high concentration of HP in fecal samples, which lowers its sensitivity. Serum antibody tests for HP are also limited in that they cannot differentiate between current infections and past exposures27. Tissue-based urease and immunohistochemical methods are commonly used but are restricted by sampling and sectioning locations, making comprehensive assessment difficult. Therefore, there is a need for new methods to assist in the rapid and accurate detection of HP infection. Raman spectroscopy of gastric juice reflects overall local gastric changes and evaluates infection at the molecular level, improving specificity and accuracy. Recent research by Tang et al. focused on detecting HP infection in gastric juice using Raman spectroscopy, with diagnostic accuracy reaching 82.15% in an independent test cohort11. However, the SERS substrates used in their study could be expensive, limiting their clinical feasibility and widespread application. Our study compared the Raman spectral features of gastric juice from HP + and HP- groups. Initially, unsupervised classification using t-SNE was not effective, suggesting that the data were not easily separable in two-dimensional space and required more complex pattern differentiation methods. In contrast, supervised classification methods like LDA and OPLS-DA were more effective in distinguishing between HP-positive and HP-negative samples. Similarly, using machine learning algorithms, we built and compared several machine learning models, and the final stacked model showed a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 98% for HP positive prediction. This result demonstrates the significant potential of using gastric juice Raman spectroscopy combined with machine learning algorithms in detecting HP infection.

Machine learning is widely regarded as a powerful tool for data analysis, particularly adept at identifying and leveraging local features while effectively extracting characteristics from signal data. These features make it highly applicable in clinical settings28. In this study, we used machine learning algorithms to analyze the Raman spectra of gastric juice samples to diagnose different stages of gastric diseases. We built and compared multiple machine learning models, mainly focusing on evaluating the predictive ability of supervised learning methods for different disease stages. Stacking multiple models for prediction significantly improved model performance. First, by combining the strengths of different models, prediction accuracy and stability were enhanced. Each model captures different data features and patterns, and stacking helps to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the data. Second, this method reduces the risk of overfitting in individual models, enhancing their generalizability and making their performance on new data more robust. Additionally, stacking allows for flexible combinations of different model types, fully utilizing the strengths of various algorithms, thus providing more powerful and diverse solutions to complex problems. In this study, The stacked model integrates the strengths of diverse algorithms—including MLP’s nonlinear modeling, GRU’s sequence sensitivity, KNN’s local pattern recognition, and GB’s focus on feature interactions—to comprehensively capture the complexity of Raman spectra, thereby achieving superior performance. After stacking, the majority vote decision rule was used to determine the prediction result for each individual spectrum. Our findings showed that the stacked model achieved excellent predictive accuracy, reaching 90%. The sensitivity and specificity for EGC diagnosis were 95% and 97%, respectively. These results support the potential use of Raman spectroscopy and machine learning algorithms in identifying different stages of gastric mucosal lesions, particularly for the early diagnosis of gastric cancer.

Raman spectra can be analyzed to extract biomolecular information, providing unique insights into the onset and progression of disease. The distribution of different Raman spectral peaks across the four gastric pathological types showed that progressive increases in adenine and glucose levels (reflected by peaks at 717 cm− 1 and 1343 cm− 1, associated with CH3/CH2 wagging vibrations of collagen) were observed along the pathological sequence from CSG to IM, DYS and EGC, potentially indicative of enhanced cellular proliferation and metabolic reprogramming during malignant transformation. Adenine, a critical component of purine metabolism, accumulates in rapidly proliferating cells due to increased demand for nucleic acid synthesis. Concurrently, elevated glucose levels reflect enhanced glycolysis, a well-documented metabolic shift in gastric cancer cells that supports energy production and biosynthesis even under aerobic conditions. The stepwise increase in these markers across stages suggests they may serve as quantitative indicators of lesion progression. Similarly, phenylalanine levels (1003 cm− 1) exhibited a stepwise elevation across disease progression stages, a finding that gains particular significance in light of reported tryptophan-to-phenylalanine codon reassignment events in Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated gastric carcinogenesis29. Conversely, amide III signals (1235 cm− 1) displayed a gradual attenuation from controls through premalignant lesions to EGC, suggesting progressive loss of native protein structural integrity during tumor development. For HP infection, the HP + group exhibited significantly higher phosphatidylinositol levels at 415 cm− 1 compared to HP- samples. This observation aligns with previous reports that HP may regulate cell migration and apoptosis through activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway30. Furthermore, at 717 cm− 1, elevated adenine levels were detected in the HP + group, suggesting that HP infection might stimulate cellular proliferation.

Although this study achieved preliminary results in differentiating gastric mucosal lesions at different stages and detecting HP infection using gastric juice Raman spectroscopy and machine learning algorithms, there are some limitations that need to be addressed in future research. First, our sample size is relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the model, the unequal distribution of samples across pathological groups may have contributed to the lower accuracy and sensitivity. Second, all samples were collected from a single hospital, which may introduce sample selection bias and affect the representativeness and extrapolation of the results. Furthermore, we lack an independent validation cohort to test the predictive performance of the model, an important step in evaluating model stability and reliability. In future studies, we plan to expand the dataset to include samples from multiple hospitals, which will improve the accuracy and robustness of the machine learning models. This will help enhance the ability to differentiate between different stages of gastric mucosal lesions and HP infection, supporting the future clinical application of this new method for the diagnosis of HP infection and early gastric cancer detection, thereby reducing the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer.

Conclusion

This study underscores the utility of Raman spectroscopy combined with machine learning as an effective tool for distinguishing different histopathological stages of precancerous and early gastric cancer, as well as for diagnosing HP-positive and HP-negative samples. By leveraging the biochemical specificity of Raman spectral analysis alongside advanced machine learning algorithms, our approach demonstrates significant promise for rapid, accurate and convenient diagnostic applications.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HP:

-

Helicobacter pylori

- EGC:

-

Early gastric cancer

- DYS:

-

Dysplasia

- IM:

-

Intestinal metaplasia

- CSG:

-

Chronic superficial gastritis

- ctDNA:

-

Circulating tumor DNA

- CAG:

-

Chronic atrophic gastritis

- MALT:

-

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- LDA:

-

Linear discriminant analysis

- OPLS-DA:

-

Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis

- GRU :

-

Gate recurrent unit

- MLP:

-

Multilayer perceptron

- ANN:

-

Artificial Neural Network

- GB:

-

Gradient boosting

- KNN:

-

K-nearest neighbors

- RF:

-

Random forest

- LSVM:

-

Linear support vector machine

- LR:

-

Logistic regression

- QDA:

-

Quadratic discriminant analysis

- NB:

-

Naive Bayes

- RSVM:

-

Radial basis function kernel support vector machine

- SVM:

-

Support vector machine

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- t-SNE:

-

T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

- EBV:

-

Epstein–Barr virus

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74 (3), 229–263 (2024).

den Hollander, W. J. et al. Surveillance of premalignant gastric lesions: A multicentre prospective cohort study from low incidence regions. Gut 68 (4), 585–593 (2019).

Tan, P. & Yeoh, K. G. Genetics and molecular pathogenesis of gastric adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 149 (5), 1153–1162e3 (2015).

Huang, R. J. et al. Pepsinogens and Gastrin demonstrate low discrimination for gastric precancerous lesions in a multi-ethnic United States cohort. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20 (4), 950–952e3 (2022).

Gasparello, J. et al. Liquid biopsy in gastric cancer: A snapshot of the current state of the Art. J. Liquid Biopsy. 7, 100288 (2025).

Zheng, Z. et al. Functions and clinical applications of exosomes in gastric cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 21 (5), 2330–2345 (2025).

Lee, Y. C., Dore, M. P. & Graham, D. Y. Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Annu. Rev. Med. 73 (1), 183–195 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Single-Cell identification, drug susceptibility test, and whole-genome sequencing of Helicobacter pylori directly from gastric biopsy by clinical antimicrobial susceptibility test ramanometry. Clin. Chem. 68 (8), 1064–1074 (2022).

Wang, Y. K. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection: Current options and developments. WJG 21 (40), 11221 (2015).

Charach, L. et al. Comparison of four tests for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Healthcare 12 (15), 1479 (2024).

Tang, J. W. et al. Detection of Helicobacter pylori infection in human gastric fluid through surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy coupled with machine learning algorithms. Lab. Invest. 104 (2), 100310 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Levels of malondialdehyde in the gastric juice: Its association with Helicobacter pylori infection and stomach diseases. Helicobacter 23 (2), e12460 (2018).

Guo, S., Popp, J. & Bocklitz, T. Chemometric analysis in Raman spectroscopy from experimental design to machine learning–based modeling. Nat. Protoc. 16 (12), 5426–5459 (2021).

Jadhav, S. A. et al. Development of integrated microfluidic platform coupled with surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for diagnosis of COVID-19. Med. Hypotheses. 146, 110356 (2021).

Ho, C. S. et al. Rapid identification of pathogenic bacteria using Raman spectroscopy and deep learning. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 4927 (2019).

Lee, W. et al. Label-free prostate cancer detection by characterization of extracellular vesicles using Raman spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 90 (19), 11290–11296 (2018).

Zhang, K. et al. Label-free diagnosis of lung cancer with tissue-slice surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy and statistical analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 34 (9), 1849–1855 (2019).

Zúñiga, W. C. et al. Raman spectroscopy for rapid evaluation of surgical margins during breast cancer lumpectomy. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 14639 (2019).

Li, C. et al. Combining Raman spectroscopy and machine learning to assist early diagnosis of gastric cancer. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 287, 122049 (2023).

Nagtegaal, I. D. et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology 76 (2), 182–188 (2020).

Huang, Z. et al. Near-infrared Raman spectroscopy for optical diagnosis of lung cancer. Intl J. Cancer. 107 (6), 1047–1052 (2003).

Si, Y. T. et al. Identification of chronic non-atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia stages in the correa’s cascade through machine learning analyses of SERS spectral signature of non-invasively-collected human gastric fluid samples. Biosens. Bioelectron. 262, 116530 (2024).

Li, P. et al. Chinese national clinical practice guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of early gastric cancer. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 137 (8), 887–908 (2024).

Žuvela, P. et al. Fiber-optic Raman spectroscopy with nature-inspired genetic algorithms enhances real-time in vivo detection and diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Anal. Chem. 91 (13), 8101–8108 (2019).

Bergholt, M. S. et al. Fiberoptic confocal Raman spectroscopy for real-time in vivo diagnosis of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 146 (1), 27–32 (2014).

Miftahussurur, M. & Yamaoka, Y. Diagnostic methods ofHelicobacter pyloriInfection for epidemiological studies: Critical importance of indirect test validation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 1–14 (2016).

Sousa, C., Ferreira, R., Santos, S. B., Azevedo, N. F. & Melo, L. D. R. Advances on diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infections. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 49 (6), 671–692 (2023).

Potcoava, M. C., Futia, G. L., Gibson, E. A. & Schlaepfer, I. R. Lipid profiling using Raman and a modified support vector machine algorithm. J. Raman Spectrosc. 52 (11), 1910–1922 (2021).

Zheng, Z. et al. Hyperactivation of mTOR/eIF4E signaling pathway promotes the production of tryptophan-to‐phenylalanine substitutants in EBV‐positive gastric cancer. Adv. Sci. 11 (35), e2402284 (2024).

Nagy, T. A. et al. Helicobacter pylori regulates cellular migration and apoptosis by activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase signaling. J. Infect. Dis. 199 (5), 641–651 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The work was supported by China Health and Medical Development Foundation Cooperation Project (to WF and to SD), the Ningbo Science and Technology Plan Project (2024T017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.F. conceived and directed the study. J.W. and Y.X. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. K.Z. and Y.W. collceted the samples. J.Z. performed pathological analysis. Y.Z. and W.F. prepared the manuscript. K.Z., J.Z., J.W., and S.D. revised the manuscript and supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Peking University Third Hospital, and all participants provided written informed consent (No. IRB00006761-M2017414).

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed the final version of the manuscript and approved it for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, W., Zhang, Y., Zhai, K. et al. Raman spectroscopy and machine learning for early detection of gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori with gastric juice. Sci Rep 15, 36332 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20270-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20270-9