Abstract

Menstrual irregularity is a common health concern among female adolescents, with potential impacts on their family life, social participation, academic performance, and overall well-being. Therefore, this study aims to assess the prevalence of menstrual irregularity and identify its associated factors among female high school students in the region. A multicenter, facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 714 female students from 11 high schools, selected using a multistage sampling technique. Data were collected through a pre-tested, self-administered questionnaire, entered into EpiData version 4.6, and analyzed using statistical package for the social sciences version 26. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics. Binary logistic regression was performed to assess the association between independent variables and menstrual irregularity, with crude odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Variables with a p value < 0.25 in the bivariable analysis were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. Model fitness was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance tests. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05. The prevalence of menstrual irregularity was 29.10% (95% CI 25.90%–32.50%). Significant factors associated with menstrual irregularity included: age 18–19 years [AOR 3.08, 95% CI 1.15–8.28], early menarche (≤ 12 years) [AOR 2.60, 95% CI 1.45–4.67], sleeping ≤ 5 h per night [AOR 3.65, 95% CI 1.02–13.09], perceived moderate stress [AOR 2.04, 95% CI 1.05–3.98], and perceived high stress [AOR 3.52, 95% CI 1.60–7.76]. The prevalence of menstrual irregularity in this study was lower than that observed in previous studies. Significant factors associated with menstrual irregularity included age, early menarche, insufficient sleep, and high stress levels. It is recommended that school-based health education and stress management programs be strengthened to help reduce menstrual irregularities among female students

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Menstruation is a cyclical process of uterine bleeding caused by endometrial shedding due to hormonal interactions, primarily through the hypothalamo-pituitary-ovarian axis1. A typical menstrual cycle lasts 28 days, beginning on the first day of menstruation and ending on the first day of the next cycle2. Menstrual irregularities involve deviations in onset, frequency, flow, duration, or volume3. It is estimated that 14–25% of women experience irregular cycles, with periods that are heavier or lighter, or cycles lasting longer than 35 days or shorter than 21 days4.

Globally, an estimated 500 million people experience menstrual-related issues5. This problem is widespread among female students, with prevalence rates ranging from 23% to 76.6%, reflecting an increasing trend in both developing and developed countries6,7,8. In Africa, menstrual irregularities among female adolescents vary between 12.5% and 55% %9,10. Additionally, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization reports that in Sub-Saharan Africa, one in ten girls misses school during their menstrual period, which can result in missing up to 20% of the school year11. In Ethiopia, 26.5% to 32.6% of females report experiencing menstrual irregularities12,13. Similarly, in Ethiopia, one in four girls miss one or more days of school due to menstruation14. Menstrual irregularities are most prevalent in females under the age of 23 years15.

Various factors have been associated with menstrual irregularities in previous studies. Hormonal imbalances are a primary cause, influencing symptoms such as fatigue, stress, and anxiety, which in turn affect academic performance and social functioning16. Menstrual-related problems, particularly dysmenorrhea, are well-known for contributing to school absenteeism and reduced academic performance17. Additionally, studies have shown that menstrual irregularities can have long-term effects on health, including infertility, cardiovascular disease, and gestational diabetes mellitus18,19,20.

Despite the availability of studies reporting a high prevalence of menstrual irregularities13,21, particularly in urban settings, there is a notable gap in research focused on pastoral and agro-pastoral communities, including the Somali Region. To date, no studies have specifically examined menstrual irregularities among female students in this region. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of menstrual irregularity and its associated factors among adolescent girls in high schools in Jigjiga, Somali Region, Ethiopia.

Method and materials

Study design, area and period

A multicenter, school-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Jigjiga City, the capital of the Somali Regional State in Eastern Ethiopia. The study was carried out from May 22 to June 8, 2023. Jigjiga has seven governments and 13 non-government high schools, with a total high school student population of 24,559 comprising 13,866 males and 10,693 females (Jigjiga City Administration Education Bureau, 2023). This setting was selected to ensure diverse representation of high school female students across the city.

Eligibility criteria

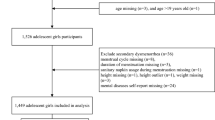

The study included adolescent girls aged 13 to 19 years who were enrolled in selected high schools, had reached menarche, and were willing to provide informed consent (and assent, along with parental or guardian consent where required). Students were excluded if they had known chronic illnesses such as diabetes, thyroid disorders, or polycystic ovary syndrome; were currently using hormonal medications that could affect the menstrual cycle; were pregnant or had been pregnant in the past; had not yet experienced menarche; or submitted incomplete or inconsistent responses to the questionnaire.

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated using Epi Info with the following assumptions: a 95% confidence level, 80% power, and proportions of menstrual irregularity among exposed (sleep duration ≤ 5 h) at 40.9% and unexposed at 28.7%, based on a previous study conducted among undergraduate students at Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia12. The variable “sleep duration” produced the largest sample size among the considered predictors. A design effect of 2 was applied to account for the multistage sampling technique, and a 10% non-response rate was added. This resulted in a final sample size of 760 participants.

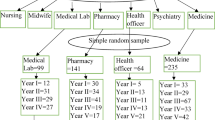

Sampling procedure

A multi-stage sampling technique was used to select participants. Total schools in Jigjiga were first stratified into public and private, and then 11 schools (4 governmental and 7 private) were randomly selected. Eligible students were identified based on inclusion criteria, and participants were chosen from each school using systematic random sampling, proportionate to the number of eligible students.

Data collection instrument

A self-administered questionnaire, adapted from previous studies12,22,23,24,25 was used to collect data. The questionari was primery prepared in English and teranslated to Somali and Amharic, and Afan Oromo using bilingual person and back translated to English to maintain the consiatancy. The questionnaire was divided into four sections: The first section gathered socio-demographic information, including age, school type, religion, parents’ educational status and occupations, and a family history of menstrual irregularities. The second section addressed lifestyle and behavioral factors such as physical activity, alcohol and coffee consumption, smoking, sleep duration, and stress levels. The third section focused on menstrual-related details, including age at menarche, contraceptive use, menstrual duration, amount, frequency, and pain during menstruation. The final section involved measuring the participants’ weight and height. Seven experienced female midwives were recruited as data collectors, and two health officers (one female and one male) served as supervisors for the study.

Data collection procedure

Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire, with respondents being informed about the purpose of the study and the importance of their participation. The questionnaire collected detailed information from the selected respondents on socio-demographic factors, reproductive health, lifestyle, and behavioral factors related to menstrual irregularity.

Variables and measurements

The dependent variable in the study was menstrual irregularity, while the independent variables included nutritional status (underweight, normal, overweight/obese), socio-demographic factors (such as age, place of residence, and family education), age at menarche, stress levels, alcohol consumption, smoking, high-intensity physical activity, sleep duration, family history of menstrual irregularity, female genital mutilation, sexually transmitted diseases, goitre, and head injuries.

Irregular menstrual cycle is characterized by any of the following: Long cycle—a cycle that occurs once every 38 days to less than 3 months; Short (frequent) cycle—a cycle that occurs once every less than 24 days; Prolonged duration—lasting 8 days or more; Heavy cycles—requiring 5 or more sanitary/vulvar pads per day; Scant cycles—requiring 2 or fewer pads per day; or a cycle-to-cycle variance of more than 10 days13,26.

Measurements of amount of menstrual blood flow per a day are Scanty (1–2 pads/day), Moderate (3–5 pads/day), Heavy (> 5 pads/day)26,27,28.

Sleep duration is categorized into three categories based on the National Sleep Foundation’s recommendation of sleep time as follows: Short sleep duration: sleeping less than seven hours of sleep per night, Normal (optimal) sleep duration: seven to nine hours per night and Long sleep duration: sleeping more than nine hours per night29.

Physical activity as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure30. Regular physical activity: High intensity physical activity is consider as regular if respondents perform it for more than or equal to 3 days per week for ≥ 20 min31, while Irregular physical activity: if it is performed for less than 3 days per week31.

Perceived stress scale

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) is a widely used 10-item multiple-choice self-report questionnaire designed to assess stress perception. Each response is scored from 0 to 4, and the total PSS score is calculated by summing all items, yielding a range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress. Scores of 0–13 indicate low stress, 14–26 indicate moderate stress, and 27–40 indicate high perceived stress32.

Data quality control

Data quality was ensured using a self-administered questionnaire translated into Amharic, Somali, and Afan Oromo. Data collectors and supervisors received two days of training on study procedures and data handling. A pretest involving 5% of the sample was conducted outside the study area to validate the tool. Supervisors monitored data collection to ensure proper participant guidance and accurate anthropometric measurements. The principal investigators and supervisors continuously oversaw the process to ensure data completeness and accuracy.

Data processing and analysis

The collected data were cleaned, coded, and entered into EpiData version 4.6 software, then exported to SPSS version 26 for analysis. Descriptive analysis was conducted to summarize the characteristics of the study participants, with the results presented in text, tables, and figures. Binary logistic regression was performed to examine the association between each independent variable and the outcome variable, using crude odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval. Variables with a p value less than 0.25 were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. The model’s fitness was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and multicollinearity was evaluated using the variance inflation factor and tolerance tests. A p value of less than 0.05 in the multivariable analysis was considered statistically significant for identifying associations.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 714 female students participated in this study, achieving a response rate of 93.9%. The participants’ ages ranged from 15 to 19 years, with a mean age of 18.09 years (SD: ±0.80). The majority of the participants were Muslim 640, (89.6%) and single 677, (94.8%). In terms of parental education, 237 (33.2%) of participants’ fathers and 292 (40.9%) of participants’ mothers had no formal education. Most mothers were housewives 445, (62.3%), while the largest proportion of fathers were merchants 198, (35.9%). Additionally, nearly all participants 707, (99.0%) resided in urban areas (Table 1).

Lifestyle characteristics of study participant students

The study revealed key findings regarding the lifestyle and health characteristics of the respondents. A vast majority (98.9%) reported no alcohol consumption in the past 30 days, with minimal consumption of beer (0.4%), wine (0.3%), and only (1.0%) drinking monthly and (0.14%) weekly. Coffee consumption was reported by (16.7%) of respondents, with 4.9% consuming one cup daily, (10.2%) drinking 1–3 cups daily, and (0.3%) drinking more than 5 cups daily. In terms of sleep, 19% slept ≤ 5 h per day, (73%) slept 6–8 h, and 7.1% slept ≥ 9 h. Body mass index (BMI) classifications showed 60.1% of participants were of normal weight, 25.4% underweight, 11.5% overweight, and 3.15% obese. Physical activity levels were predominantly low (95.2%), with only 2.8% reporting moderate and 2.0% high-intensity activity. Perceived stress was low for 22.7% of respondents, moderate for 59.5%, and high for 17.8%. Almost all participants reported no history of sexually transmitted diseases (99.44%), goiter (99.9%), head injuries (97.1%), or smoking (99.6%).

Menstrual patterns of the respondent

Out of all the study participants, 29.13% (95% Confidence Interval: 25.9% to 32.5%) reported experiencing an irregular menstrual cycle. Among those with menstrual irregularities, 231 participants (32.35%) described their menstrual flow as light, defined as using fewer than two sanitary pads or towels per day. Additionally, 167 participants (23.4%) reported irregular onset, and 146 (20.45%) had cycles shorter than 24 days. Over the past three months, 647 participants (90.6%) reported experiencing long periods lasting eight days, while 430 (60.22%) had cycles within the normal range of 24 to 38 days. The average age at menarche was 13.53 years (SD ± 1.455 years).

Regarding menstrual hygiene, 528 participants (73.9%) reported using pads during menstruation. Pain during menstruation was common, with 442 (61.9%) experiencing it, and 299 (41.9%) reporting pain lasting 1–2 days. Furthermore, 245 participants (34.3%) used pain relief methods during menstruation. In terms of family history, 415 participants (58.1%) reported no family history of menstrual irregularities. Most participants (98.6%) did not use contraceptive methods during menstruation, and 604 (84.6%) reported being circumcised (Table 2).

Factors associated with menstrual irregularity

In the bivariate analysis, factors such as the respondent’s age, marital status, parents’ education and occupation, age at menarche, sanitation materials, pain duration, family history, contraceptive use, circumcision type, head injury, coffee consumption, sleep duration, perceived stress, and obesity were found to be significantly associated with menstrual irregularity, with a p value < 0.25. These variables were therefore considered as candidates for multivariable analysis.

However, in the multivariable logistic regression analysis, respondents aged 18–19 years, those with early menarche (≤ 12 years), those who slept ≤ 5 h, and those experiencing moderate to high perceived stress were found to have a significant association with menstrual irregularity, with a 95% confidence level and p < 0.05.

The study identified that students aged 18–19 years were three times more likely to experience irregular menstruation [AOR 3.08, 95% CI (1.15–8.28)] compared to those aged 15–17 years. Additionally, participants who experienced early menarche (≤ 12 years) had a 2.6 times higher more likely [AOR 2.60, 95% CI (1.45–4.67)] of menstrual irregularity compared to those with medium or average menarche (13–14 years). Furthermore, individuals who slept ≤ 5 h per night were 3.6 times more likely [AOR 3.65, 95% CI (1.02–13.09)] to have menstrual irregularity compared to those who slept ≥ 9 h. Moderate stress was also found to be a significant factor, with participants reporting moderate stress being twice as likely [AOR 2.04, 95% CI (1.05–3.98)] to experience menstrual irregularity compared to those with low stress. Finally, those who experienced high perceived stress were 3.5 times more likely [AOR 3.52, 95% CI (1.60–7.76)] to have menstrual irregularity than those with low stress (Table 3).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence and determinants of menstrual irregularities among female adolescent high school students in Jigjiga. The findings revealed that the prevalence of menstrual irregularities was 29.1%. Significant factors associated with menstrual irregularities included being aged 18–19 years, experiencing early menarche, having a sleep duration of 5 h or less, and reporting moderate to high levels of perceived stress.

The prevalence of menstrual irregularity in the current study was consistent with studies conducted in Delhi, India (29.1%) and Indonesia (34%)33,34. Similarly, studies conducted at Debre Berhan University reported magnitude of 32.6% and 33.4%13,21. The similarity in findings could be attributed to the use of similar measurement tools and comparable sample sizes across these studies. Incontarary, there are a number of studies done several countries which are higher magnitude than the current study. Eviedences revealed that studes done in Al Neelain University in Sudan, Nepal, King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia with magnitude of 55.0%, 76.6%, 48.2% respectively35,36,37. Also nearly similar study was done in Bahir Dar University, and it was reported that magnitude of menstrual irregularity was 46.2%38. The differences in menstrual irregularity magnitude between studies may be due to variations in study design, sample populations, and age groups.

On the other hand, several studies reported lower magnitude of menstrual irregularity compared to the current study. A study conducted in Ghana found 7.7%, while another study in Kerala, India reported 24%39,40. Similarly, a study conducted at Debre Berhan University in Ethiopia reported 14.6%41. The differences in prevalence rates may be due to variations in age distribution, definitions of menstrual irregularity, socio-economic and socio-cultural factors.

The study identified that students aged 18–19 years were three times more likely to experience irregular menstruation, this finding was consistent with the result of previous studies42,43. A similar study in Debre Berhan, Ethiopia, also linked being under 20 years old with menstrual irregularity21. This might be attributed to biological, environmental, and psychosocial factors. Late adolescence is a period of continued hormonal adjustments as the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis matures, which may result in delayed stabilization of menstrual cycles. Additionally, older adolescents often face heightened academic pressures and social responsibilities, leading to increased stress levels that disrupt hormonal balance. Lifestyle factors such as poor sleep, irregular eating habits, and reduced physical activity further contribute to the observed irregularities44.

Additionally, participants who experienced early menarche (≤ 12 years) had a 2.6 times more likely to expariance menstrual irregularity compared to those with medium or average menarche (13–14 years). This finding is consistent with earlier studies conducted in Debre Berhan, Lebanon, and Korea21,45,46. However, it was contradicting with studies in Taiwan and Italy, where late menarche was identified as a risk factor for menstrual irregularity47,48. This might be due to prolonged exposure to hormonal fluctuations and the immature hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis during early adolescence. Early menarche can also reflect underlying genetic, nutritional, or environmental factors that influence hormonal regulation, potentially predisposing individuals to cycle irregularities later. Differences in findings across studies, such as those in Taiwan and Italy, may stem from variations in study populations, cultural factors, or definitions of menstrual irregularity49.

Furthermore, particupants who slept ≤ 5 h per night were 3.6 times more likely [AOR 3.65, 95% CI (1.02–13.09)] to have menstrual irregularity compared to those who slept ≥ 9 h. This finding is consistent with studies conducted in Debre Berhan colleges, Debre Berhan universities, and Korea, which reported similar results13,21,50. Disruptions in the body’s circadian rhythms and sleep-wake patterns, which regulate the secretion of hormones such as melatonin, cortisol, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and prolactin, may contribute to these menstrual irregularities51.

Furthermore, stress has been identified as a significant factor contributing to menstrual irregularity. This study found that individuals with high and moderate stress levels were more likely to experience menstrual irregularities compared to those with low stress. This aligns with findings from studies in Debre Berhan Colleges, Debre Berhan Universities, and research conducted in China, North America, and Korea13,17,21,52,53,54. Psychological stress may disrupt the HPO axis, affecting the coordinated functioning of key glands involved in menstrual regulation55.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study focused on high school adolescent girls, a population particularly vulnerable to menstrual irregularities, thereby addressing a significant gap in the existing literature, especially within the Somali Region of Ethiopia. The use of a multicenter, facility-based design with a multistage sampling technique across 11 high schools enhances the internal validity and representativeness of the findings within the region. However, the results may not be fully generalizable to the broader Ethiopian student population due to regional differences in lifestyle, socioeconomic status, and cultural practices. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to infer causal relationships between menstrual irregularity and associated factors. The reliance on self-reported data over the past three months also introduces the potential for recall bias, and the sensitive nature of the topic may have led to underreporting by some participants.

Conclusion

The prevalence of menstrual irregularity in this study was lower than that observed in previous studies. The factors linked to menstrual irregularity include age (18–19 years), early menarche (≤ 12 years), sleep duration of less than 5 h, and moderate to high perceived stress levels.

Recommendation

Healthier lifestyle practices, including stress management and adequate sleep, are crucial for managing menstrual irregularities in adolescent girls. Regional health and education bureaus should promote strategies for healthy sleep, stress control, and menstrual health education. Students are encouraged to adopt these practices to improve menstrual health and academic performance. Further research is needed to explore causal factors and effective interventions.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- WHO:

-

World Health organization

- PSS:

-

Perceived stress scale

- SPSS:

-

Statistical pakage for social scince

References

Dutta, D. Textbook of DC Dutta’s Gynecology 6th edn (Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd, 2013).

ACOG. The Menstrual cycle: Menstruation, ovulation, and how pregnancy occurs. [cited 2024 1 January]; (2022). Available from: https://www.acog.org/womens-health/infographics/the-menstrual-cycle

Jyothi, G., Kumar, A. & Murthy, N. S. Correlation of anthropometry and nutritional assessment with menstrual cycle patterns. J. South. Asian Federation Obstet. Gynecol. 10 (4), 263–269 (2018).

Gomes, H. et al. Abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescence: when menarche reveals other surprises. Rev. Bras Ginecol E Obstet. 43 (10), 789–792 (2021).

BANK, W. Menstrual Health and Hygiene (2022). Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water/brief/menstrual-health-and-hygiene

Tewari, D. & Tewari, P. Assessment of menstrual disorders among adolescent girls. Int. J. Home Sci. 6 (3), 462–465 (2020).

Marques, P., Madeira, T. & Gama, A. Menstrual cycle among adolescents: Girls’ awareness and influence of age at menarche and overweight. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 40, e2020494 (2022).

Latif, S. et al. Junk food consumption in relation to menstrual abnormalities among adolescent girls: A comparative cross sectional study. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 38 (8), 2307 (2022).

Anikwe, C. C. et al. Age at menarche, menstrual characteristics, and its associated morbidities among secondary school students in abakaliki, Southeast Nigeria. Heliyon 6 (5), e04018 (2020).

Ali, A., Khalafala, H. & Fadlalmola, H. Menstrual Disorders among Nursing Students at Al Neelain University, Khartoum State (Sudan Journal of Medical Sciences (SJMS), 2020).

UNISCO. Menstrual Hygiene Management. [cited 2024 May 2024]; (2014). https://pacificdata.org/data/dataset/b08f10df-3115-4beb-980c-e761eb176c1b/resource/eebe0ff0-4e9a-48d5-b00e-21bed26d5df5/download/mhm-in-kiribati-schools-10pt-1.pdf

Mittiku, Y. M. et al. Menstrual Irregularity and its Associated Factors among College Students in Ethiopia, 2021 3 (Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 2022).

Zeru, A. B., Gebeyaw, E. D. & Ayele, E. T. Magnitude and associated factors of menstrual irregularity among undergraduate students of Debre Berhan university, Ethiopia. Reproduct. Health. 18 (1), 101 (2021).

Sahiledengle, B. et al. Menstrual hygiene practice among adolescent girls in ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 17 (1), e0262295 (2022).

Aber, A. Prevalence of menstrual disturbances among female students of fourth and fifth classes of curative medicine faculty. IJRDO—J Health Sci. Nurs. 3 (4), 1–14 (2018).

Demeke, E. et al. Effect of menstrual irregularity on academic performance of undergraduate students of Debre Berhan university: A comparative cross sectional study. Plos One. 18 (1), e0280356 (2023).

Ansong, E. et al. Menstrual characteristics, disorders and associated risk factors among female international students in Zhejiang province, china: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Women’s Health. 19 (1), 1–10 (2019).

Wang, Y. X. et al. Pre-pregnancy menstrual cycle regularity and length and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: Prospective cohort study. Diabetologia 64 (11), 2415–2424 (2021).

Musa, S. & Osman, S. Risk profile of Qatari women treated for infertility in a tertiary hospital: A case-control study. Fertil. Res. Pract. 6, 1–17 (2020).

Rostami Dovom, M. et al. Menstrual cycle irregularity and metabolic disorders: A population-based prospective study. PLoS One. 11 (12), e0168402 (2016).

Mittiku, Y. M. et al. Menstrual irregularity and its associated factors among college students in Ethiopia. Front. Glob. Women’s Health. 2022 (3), 917643 (2021).

Sreelakshmi, U. et al. Impact of dietary and lifestyle choices on menstrual patterns in medical students. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 8 (4), 1271–1277 (2019).

Alhammadi, M. et al. Menstrual Cycle Irregularity and Examination Stress Among Female Medical Students at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. (2022).

Abd Elwadood, A. A. et al. The effect of hormonal contraception and intrauterine device on the pattern of menstrual cycle. J. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 4 (2), 225 (2019).

Sen, L. C. et al. Study on relationship between obesity and menstrual disorders. Asian J. Med. Biol. Res. 4 (3), 259–266 (2018).

Muluneh, A. A. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of dysmenorrhea among secondary and preparatory school students in Debremarkos town, North-West Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health 18 (1), 1–8 (2018).

Rahayu, E. P. The Relationship nutritional status with the menstrual cycle and dismenorea incident in midwifery diploma Unusa, in Proceeding Surabaya International Health Conference 2017 (2017).

Liu, X. et al. Early menarche and menstrual problems are associated with sleep disturbance in a large sample of Chinese adolescent girls. Sleep 40 (9) (2017).

Hirshkowitz, M. et al. National sleep foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 1 (1), 40–43 (2015).

WHO. Physical activity. [cited 2024 November]; (2024). Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity

WHO. Global status report on physical activity 2022. [cited 2024 16 January 2024]; (2022). Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/physical-activity/global-status-report-on-physical-activity-2022

Cohen, S. & Williamson, G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the US In S. Oskamp & S. Spacapam, in The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology (Sage Publications, 1988).

Bhardwaj, P., Yadav, S. K. & Taneja, J. Magnitude and associated factors of menstrual irregularity among young girls: A cross-sectional study during COVID-19 second wave in India. J. Fami. Med. Prim. Care 11 (12), 7769 (2022).

Erye, E. et al. The relationship between food consumption patterns and the menstrual cycle in aldoscent girls. MIKIA: Mimbar Ilmiah Kesehatan Ibu dan Anak (Maternal and Neonatal Health Journal) 40–48 (2021).

Ali, A., Khalafala, H. & Fadlalmola, H. Menstrual disorders among nursing students at al Neelain university, Khartoum state. Sudan. J. Med. Sci. (SJMS) 199–214 (2020).

Chhetri, D. D. & Singh, M. S. Menstrual characteristics among the nepali adolescent girls. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 11(7) (2020).

Alhammadi, M. H. et al. Menstrual Cycle Irregularity during Examination among Female Medical Students at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Vol. 367, 22 (BMC Women’s Health, 2022).

Shiferaw, M. T., Wubshet, M. & Tegabu, D. Menstrual problems and associated factors among students of Bahir Dar university, Amhara National regional state, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional survey. Pan Afr. Med. J. 17 (2014).

Osonuga, A. & Ekor, M. N. The menstrual characteristics of undergraduate students in a Ghanaian public university. Jos J. Med. 12 (1), 57–63 (2018).

Varghese, L., Prakash, P. J. & Lekha, V. A study to identify the menstrual problems and related practices among adolescent girls in selected higher secondary school in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India. J SAFOG (South Asian Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology) 11 (1), 13–16 (2019).

Derseh, B. et al. Prevalence of Dysmenorrhea and its Effects on School Performance: A Cross-sectional Study., Vol. 6, 6 (2017).

Varghese, L., Saji, A. & Bose, P. Menstrual irregularities and related risk factors among adolescent girls. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 11, 2158 (2022).

Zafar, M. et al. Pattern and prevalence of menstrual disorders in adolescents. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res., 9(5) (2017).

Guzha, B. T. et al. Assessment of the impact of HIV infection on the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and pubertal development among adolescent girls at a tertiary centre in zimbabwe: A cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr. Disorders. 25 (1), 16 (2025).

Karout, N., Hawai, S. & Altuwaijri, S. Prevalence and pattern of menstrual disorders among Lebanese nursing students. EMHJ-East. Mediterr. Health J. 18 (4), 346–352 (2012).

Jung, A. N. et al. Detrimental effects of higher body mass index and smoking habits on menstrual cycles in Korean women. J. Womens Health (Larchmt). 26 (1), 83–90 (2017).

Chang, P. J. et al. Risk factors on the menstrual cycle of healthy Taiwanese college nursing students. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 49 (6), 689–694 (2009).

De Sanctis, V. et al. Age at menarche and menstrual abnormalities in adolescence: does it matter? The evidence from a large survey among Italian secondary schoolgirls. Indian J. Pediatr. 86 (Suppl 1), 34–41 (2019).

Rigon, F. et al. Menstrual pattern and menstrual disorders among adolescents: An update of the Italian data. Ital. J. Pediatr. 38 (1), 38 (2012).

Kim, T. et al. Associations of mental health and sleep duration with menstrual cycle irregularity: A population-based study. Arch. Women Ment. Health. 21, 619–626 (2018).

Shechter, A. & Boivin, D. B. Sleep, hormones, and circadian rhythms throughout the menstrual cycle in healthy women and women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Int. J. Endocrinol. 259345 (2010).

Bhardwaj, P., Yadav, S. K. & Taneja, J. Magnitude and associated factors of menstrual irregularity among young girls: A cross-sectional study during COVID-19 second wave in India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 11 (12), 7769–7775 (2022).

Nillni, Y. I. et al. Mental health, psychotropic medication use, and menstrual cycle characteristics. Clin. Epidemiol. 1073–1082 (2018).

Jung, E. K. et al. Prevalence and related factors of irregular menstrual cycles in Korean women: The 5th Korean National health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES-V, 2010–2012). J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 39 (3), 196–202 (2018).

Stephens, M. A. & Wand, G. Stress and the HPA axis: Role of glucocorticoids in alcohol dependence. Alcohol Res. 34 (4), 468–483 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Haramaya University deserves our heartfelt gratitude for allowing us to conduct this research and, We also appreciate the dedication and time spent by data collectors, supervisors, and study participants during the data collection period.

Funding

The study was not funded by any organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (NH, KS, TYN, AAL, and HM) equally contributed to the conception of the research problem, initiated the research, wrote the research proposal, conducted the research, made data entry, analysis, and interpretation, and wrote and reviewed the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee of the College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, (Reference Number: IHRERC/087/2023). and was subsequently delivered to the Somali Regional Education Bureau (SREB) and Jigjiga city administrations for their official approval. Letters were prepared and submitted to the local authorities of the selected schools. Signed, voluntary, written, Informed consent was obtained from each participant. For participants under the age of 18 years, informed, voluntary, written, and signed consent was obtained from their parents or guardians. Confidentiality was maintained at all levels of the study. Participant selection was based on their willingness to participate, and they were fully informed of the voluntary nature of the study, including their right to withdraw at any time.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hussein, N., Shiferaw, K., Lonsako, A.A. et al. Menstrual irregularity and associated factors among female adolescents in Somali region high schools Ethiopia 2023. Sci Rep 15, 36591 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20342-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20342-w