Abstract

This study investigates changes in the wind regime over the Caspian region and their impact on sea level fluctuations, utilizing MERRA-2 reanalysis data spanning the period 1980–2023. The analysis revealed no statistically significant variation in average wind speed between the phase of sea level decline (2005–2022) and the preceding phase of sea level rise (1984–2004). However, more detailed examination of specific wind parameters indicated notable shifts: the speed of resultant winds increased by 10.3%, accompanied by a 9.5° change in predominant wind direction, as derived from eastward and northward wind vector components. Furthermore, comparison of resultant wind characteristics with key climatic indices—specifically the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) and the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)—demonstrated a moderate relationship between wind regime variability and sea level dynamics, including interannual fluctuations. These findings underscore that sea level changes in the Caspian Sea are closely linked to climate variability, mediated in part through alterations in regional wind patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Caspian Sea is the largest enclosed body of water in the world. Due to its geographical location and isolation from the ocean, its water level is constantly changing. In the 20th century, the sea level fluctuated between 25.6 and 29 m below ocean level (Baltic system). Since the beginning of the 21st century, the Caspian Sea level (CSL) has shown a decreasing trend, reaching 28.9 m below ocean level and closely approaching the lowest recorded level of modern times, set in 1977 at -29 m. The phenomenon of prolonged anomalous low and high sea levels represents a significant feature of the sea’s hydrological regime, greatly affecting various economic activities in the countries within the Caspian region1. Additionally, the long-term fluctuations of the Caspian Sea level also influence the climate of the surrounding area2,3.

Given the ongoing climate warming, the future changes in sea level of the Caspian Sea are a topic of significant interest. However, research in this area is limited due to a lack of clarity regarding the causes and mechanisms that govern sea level variability, making long-term forecasting challenging. Recent studies conducted in different countries have significantly expanded our understanding of the primary factors influencing the sea level regime of the Caspian Sea4,5,6,7,8,9. Fluctuations in the Caspian Sea Level (CSL) depend on a range of climatic, tectonic, and anthropogenic factors10,11,12,13,14,15. These factors interact in complex ways and continuously change over time and across different locations. The level of the Caspian Sea is primarily determined by its water balance, which is connected to climatic elements, including the runoff from approximately 130 rivers that feed into it, precipitation falling on its surface, and evaporation from that surface. The discharge component of the Caspian Sea water balance also includes water outflow into the Kara-Bogaz-Gol, while the inflow component includes subsurface (groundwater) contributions. However, in comparison to the primary components of the water balance—namely riverine inflow, direct precipitation, and evaporation—these additional fluxes are relatively minor and tend to offset each other. Consequently, they are typically excluded from consideration in most practical hydrological assessments1,4,16,17.

Future Sea level change in the Caspian Sea has been evaluated under various climate scenarios. For instance, Samant and Prange18 estimated changes in Caspian Sea level (CSL) during the 21st century using outputs from 15 climate models participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) under three Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). In the Caspian Sea basin, the projected increase in evaporation significantly exceeds the increase in precipitation, resulting in a progressively negative water balance over the 21st century. The models project sea level declines of approximately 8 m (inter-model range: 2–15 m) under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, and about 14 m (inter-model range: 11–21 m) under the high-emissions SSP5-8.5 scenario by the end of the century.

Based on CMIP5 scenarios, Pavlova et al.19 additionally forecast an increase in the frequency and intensity of storm-induced wind waves in the Caspian Sea region throughout the 21st century.

From this perspective, if climate change—particularly global warming—and anthropogenic pressures continue to intensify at current rates, the Caspian Sea may face a fate similar to that of the Aral Sea and other terminal (closed-basin) water bodies across the globe. However, it should be noted that historically, unlike other enclosed bodies of water, the Caspian Sea has been characterized mainly by natural, relatively slow, and reversible fluctuations in water level, which are mitigated by its enormous volume. Meanwhile, the history of the Aral Sea clearly demonstrates how the irrational use of water resources from rivers flowing into the sea can lead to a rapid and largely irreversible ecological disaster, underscoring the importance of sustainable river basin management.

Sea level and total annual river discharge into the sea can be determined from contact observations. Only recently has the measurement and calculation of evaporation from the sea surface been made with sufficient reliability, as reanalysis and satellite data can now be used for this purpose4,20,21. However, in most cases, different methods and approaches for estimating evaporation from the sea surface are still insufficient for accurate modelling. This also applies to precipitation falling on the sea surface due to insufficient contact observation points throughout the Caspian Sea. For this reason, this paper will focus not so much on these parameters directly but on the various factors affecting them and estimates of their influence.

Relative humidity and wind speed affect the evaporation rate from the water’s surface because they influence air and water surface temperature in areas with upwelling22. Under conditions when other factors are held constant, the evaporation rate increases with increasing air and water surface temperature. However, evaporation does not significantly depend on the Caspian Sea region’s air and water surface temperature. For example, the average annual evaporation in the period 1930–1977, when the water level dropped sharply and the temperature was relatively low, was greater than the amount of evaporation in the period 1978–1995, when water levels rose sharply and temperatures were relatively high23,24. This suggests that other factors, especially wind, may play a role. From this point of view, it is of great interest to study the changes in the wind regime during periods of rising and falling water levels in the Caspian Sea.

The character of winds over the Caspian Sea is determined by the large-scale influence of atmospheric circulation, local baricocirculation, and thermal conditions. The diversity of wind conditions in the Caspian Sea is caused by the large meridional extent of the sea and by differences in the physical and geographical conditions of the coast25. The Caspian Sea is in the zone of influence of different types of atmospheric circulationAll these circulation types are continuously changing and, interacting with each other, create a stochastic (probabilistic) character of weather variability1.

A number of studies have been devoted to the wind regime in the Caspian Sea8,26,27,28,29,30. These studies consider various aspects of the spatial and temporal distribution of wind speed and direction, associated hazardous phenomena, etc. They showed evidence that when wind speed and direction over the sea underwent significant changes, it affected evaporation rates during periods of sea level fall and rise28,29. For example, in29, based on the NCEP/NCAR (R-1) data, it shows that during periods of sea level decline (1948–1976 and 1996–2017), the eastern component prevailed, which is characterized by significant dryness, leading to increased evaporation. Conversely, during the sea level rise period (1977–1995), the northern component of wind prevailed, characterized by relatively higher humidity and lower temperatures. Comparing the integrated values of recurrence and velocity of winds of different rhumbas with sea level they found that sea level decreases when easterly winds prevail and increase when northerly winds prevail. However, the coarse spatial resolution of the reanalysis data used in the study limits the ability to resolve region-specific characteristics of wind regime changes across different parts of the Caspian Sea.

During the last period of sea level decline (1996–2020), in addition to the influence of changes in wind characteristics, there was also an increase in mean annual sea surface temperature24, leading to increased evaporation. Serykh and Kostianoy30 analysed climate parameters from 1900 to 2015 and concluded that the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans influence the CSL with changes in the wind regime. However, all these works analysed the effect of wind on sea level changes qualitatively rather than quantitatively.

In the study by Kruglova and Myslenkov27, the meridional (V) and zonal (U) wind components were analysed to assess the impact of wind on storm activity. However, the potential influence of variations in these wind components on sea level fluctuations was not addressed in their analysis.

Despite numerous studies on the wind regime of the Caspian Sea, most analyses of wind direction have relied on wind rose diagrams constructed for individual coastal or offshore locations. This localized approach fails to provide a quantitative or spatially integrated assessment of wind regime dynamics across the entire sea surface.

The primary objective of this study is to quantify spatiotemporal changes in the Caspian Sea wind regime during periods of sea level rise and decline, utilizing the eastward (U) and northward (V) wind components from the MERRA-2 reanalysis dataset for the period 1980–2023. From these components, the study derives new, more informative parameters—specifically, the resultant wind speed and direction—which allow for a comprehensive evaluation of wind variability across the entire basin. This methodological approach has not previously been applied to the Caspian Sea and therefore constitutes a novel contribution to the understanding of wind–sea level interactions in closed-basin systems.

Study area

The Caspian Sea is located on the border of the Eurasian continent. The sea, a remnant of the ancient Tethys Ocean, lost its natural connection with the world ocean about 70 million years ago31,32. The sea, extending in meridional direction for about 1200 km, is located between 36°33’-47°07’ north latitudes and 45°43’-54°03’ east longitudes. The average sea width is 310 km, and the narrowest and widest parts are 196 and 410 km, respectively33. The Caspian Sea, located in a predominantly semi-arid zone, has five littoral states: Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Russia. The sea surface area at -28,0 m is 380,000 km2, and its volume is 78,000 km3. The Caspian Sea has a catchment area of 3.5 million km2, about nine times the sea’s surface area. This basin also covers the five littoral states and the territory of three other countries (Armenia, Georgia, and Turkey)34. The length of the sea coastline, including islands, is about 7500 km at a mark of -27 m, but this figure is constantly changing due to sea level fluctuations.

According to its physiographic and morphological conditions, the Caspian Sea is conventionally divided into three parts: the North Caspian Sea, the Middle Caspian Sea, and the South Caspian Sea (Fig. 1). The North Caspian is separated from the Middle Caspian by Chechen Island and Cape Tyub-Karagan1,25. Its area is about 91,500 km2. The North Caspian region is mainly located in the shelf zone. The average sea depth is 5–6 m, with a maximum depth of 15–20 m. The Volga and Ural rivers flowing into the sea create deltas along the coast surrounded by dense reeds. Relict forms of coasts and deltas are considered one of the main features that distinguish the North Caspian region due to its morphological structure25. The Middle Caspian covers an area of about 140,000 km2. The average sea depth here is 192 m, and the deepest place is the Derbend Depression (788 m). The line connecting Chilov Island and Cape Kuli was accepted as the middle and south Caspian boundary. The South Caspian Sea has an area of 148,500 km2 and is in a large depression belonging to the Alpine-Himalayan fold. The average depth of the sea here is 344 m, and the deepest place is the Lankaran depression (1025 m). The relief of the South Caspian seabed is characterized by numerous tectonic uplifts and mud volcanoes.

Caspian Sea map with the indication of water discharge, sea level points, rivers and divisions (with the background of open access ESRI35 satellite imagery basemap).

Data and research methodology

To analyse the impact of wind regimes on CSL fluctuations, this study integrates long-term hydrological, climatic, and meteorological datasets. Long-term (1938–2021) hydrological observations from key rivers feeding the Caspian Sea (Volga, Kura, Ural, Terek, Sulak, Sefidrud, Polrud, Shalus, and Kharaz) were used to assess variations in freshwater inflow and their contributions to sea level changes. Long-term sea level records (1900–2021) from the Makhachkala hydrological station (http://www.caspcom.com) provided data on the historical trends in water level fluctuations. Wind reanalysis data from 1980 to 2023, obtained from NASA Power Data Access Viewer (https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/) and Giovanni data repository (https://giovanni.gsfc.nasa.gov/), were analysed to wind characteristics at 10 m height. Climate index data from 1900 to 2021 were extracted from https://climexp.knmi.nl/ to evaluate broader atmospheric influences on CSL trends. Annual data on evaporation flux from the Caspian Sea surface from 1979 to 2022 were taken from ERA5. It should be noted that Kara-Bogaz-Gol Bay was excluded from the basin-wide averages and treated as an additional discharge sink for the Caspian Sea.

Various methods of mathematical statistics, including t-test of Student, trend and correlation analyses, were used to compare time series of data, identify their development trend, and possibly determine a relationship between them. The student’s t-test was used to test the statistical significance of changes in statistical series of different variables. To test the statistical significance of Pearson correlation coefficients between statistical series of different variables, we used the formula36:

where t is a value obeying Student’s distribution with n-2 degrees of freedom, n is the length of time series, and r is a correlation coefficient. It is compared with the critical value determined by the student’s distribution table at a given significance level and degree of freedom.

To assess the presence of autocorrelation in the time series data, we applied both visual and statistical methods. The Autocorrelation Function (ACF) and Partial Autocorrelation Function (PACF) were analyzed to identify significant lag dependencies, which are particularly common in climatological time series due to inherent persistence and seasonality. Additionally, the Ljung–Box Q-test (Ljung & Box, 1978) was used to formally test the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation across multiple lags.

Given the properties of meteorological and climate-related time series—such as slow-varying trends, persistence, and autocorrelated noise, we employed an Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model with no differencing (i.e., ARIMA(p,0,q)) to preserve long-term trends. This method is especially suitable for environmental data, where both signal structure and amplitude must remain intact37,38. The ARIMA model was fitted to each variable using optimal lag orders selected by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). After fitting, the residuals—which represent the “whitened” series with autocorrelation removed—were extracted and validated via the Ljung–Box test to ensure the removal of serial dependence. This approach ensured correction of autocorrelation without modifying the data’s trend or distribution, a key requirement in climatological analyses.

Granger causality testing was conducted on the autocorrelation-corrected residual series. This statistical test determines whether one time series contains predictive information about another (Granger, 1969). The test was applied in both directions (e.g., Variable A → Variable B, and Variable B → Variable A) using lag lengths determined through AIC minimization within a Vector AutoRegression (VAR) framework. The null hypothesis—that one series does not Granger-cause the other—was rejected at the 5% significance level (α = 0.05) based on the F-statistic.

To ensure that serial correlation was effectively removed before conducting causality analyses, the ARIMA model parameters were explicitly estimated for each variable. The optimal lag structure of the ARIMA(p,0,q) model was selected using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Table 1 summarizes the final model parameters used for each key time series.

The Ljung–Box Q-test confirmed that the residuals from each model were free of significant autocorrelation (p > 0.05), ensuring that the whitening process was successful and did not distort the underlying trends.

Because Granger causality tests are sensitive to non-stationarity, the original time series were first tested for stationarity using two complementary approaches: the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test and the Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin (KPSS) test.

Both tests were applied to each variable to ensure robust results. If a series was identified as non-stationary by either test, it was modeled using ARIMA without differencing (d = 0) to preserve the long-term climatic trend, while still removing short-term autocorrelation through AR and MA components.

Prior to causality testing, all time series were pre-whitened using ARIMA(p,0,q) models, with optimal parameters selected based on AIC (Table 1). Stationarity of the original series was confirmed using ADF and KPSS tests (Table 2), ensuring robust statistical inference.

As shown in Eq. (2), sea level is related to the integral characteristics, not the current values of water balance elements and the factors influencing them.

In general, the simple model for changes in the CSL can be represented as follows:

where H is the mean value of CSL, and t is time. P and E are precipitation and evaporation. R is river runoff, K is flow into Kara-Bogaz-Gol Bay, and U is groundwater flowing into the sea expressed in equivalent changes in water height over the Caspian Sea per unit time. River runoff rates R, measured in rates of change in water volume, are converted into equivalent changes in CSL height by uniform distribution of runoff over the Caspian Sea water area. Accordingly, H is the integral of the total fluxes P, E, R, and U over time.

As can be seen from Eq. (2), the current sea level value depends on the time-integrated values of the balance elements and the factors influencing them.

For the analysis of the influence of water balance elements and other factors on the sea level more visually, joint difference-integral curves were constructed along with traditional ones.

The difference integrals are presented in the form:

where n is serial number of the time series elements; φ(n) is difference integral for the nth element of the time series; ki is the modular coefficient, which is determined by the ratio of the current value\(\:{x}_{i}\) of the time series to its mean value \(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\); CV is the coefficient of variation, which is determined by the ratio of the standard deviation σ of the time series to its mean value \(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\)24,33 where \(\:\phi\:\left(n\right)\) is the dimensionless quantity. The integral difference curve is convenient when studying the influence of elements of the water balance of closed reservoirs, including the Caspian Sea, on their water level because the current level of a reservoir depends on the sum of accumulated positive and negative deviations from the average and not on the current value of the water balance elements24,39.

The two primary meteorological reanalysis datasets provided by ECMWF and NASA—ERA5 and MERRA-2—demonstrate strong agreement with observational data40. A comparative analysis of ERA5 and MERRA-2 revealed that ERA5 offers higher spatial and temporal resolution, enabling the detection of localized wind patterns over the Caspian Sea. However, this increased resolution results in more spatially variable fields, reflecting the model’s heightened sensitivity to fine-scale atmospheric processes. In contrast, MERRA-2 provides smoother and more homogeneous outputs due to its coarser resolution and stronger spatial averaging. MERRA-2 has shown robust performance and internal consistency in representing near-surface wind fields over large water bodies. Its relatively stable spatial and temporal wind field characteristics are advantageous for basin-scale climatological studies, as they help mitigate the effects of high-frequency noise that may be more pronounced in ERA5, particularly in coastal and marine grid cells41,42,43.

To ensure the reliability of the selected dataset, a comparative evaluation was conducted between MERRA-2 and ERA5, supplemented by validation against in situ wind observations from coastal meteorological stations surrounding the Caspian Sea. The results revealed moderate agreement in the seasonal and interannual variability of wind vectors, confirming that MERRA-2 is sufficiently accurate and stable for the objectives of this study (Fig. 2).

As illustrated in Fig. 2 (a and b) and Table 3, ERA5 exhibits a slight advantage in capturing point-based wind characteristics, primarily due to its higher spatial resolution compared to MERRA-2. However, since this study focuses on spatially averaged wind data across the Caspian Sea basin, the limitations associated with MERRA-2’s coarser resolution become negligible41.

Given these considerations—especially the need for a harmonized, long-term dataset with demonstrated stability over marine environments, the selection of MERRA-2 is scientifically justified and well aligned with the objectives of this study.

The Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2) is a global atmospheric reanalysis dataset produced by NASA’s Global Modelling and Assimilation Office (GMAO). It provides high-resolution weather, climate, and atmospheric composition data from 1980 to the present. MERRA-2 incorporates satellite-based observations and advanced assimilation techniques to improve accuracy, particularly in aerosols, precipitation, and land-atmosphere interactions. It is widely used for climate studies, air quality research, and meteorological applications. MERRA-2 assimilates GPS-Radio Occultation bending angle measurements from satellite missions like COSMIC, GRACE, and MetOp44. MERRA-2 uses 3DVAR with Goddard Earth Observing System Model 5.12.4 (2015) atmospheric data assimilation system with cubed-sphere horizontal discretization40. All points of MERRA-2 measurements are rationally distributed over the Caspian Sea with the sampling distance of 50 km.

To analyse the distribution of mean annual wind speed over the Caspian Sea and its variations during periods of sea level rise and decline, we utilized monthly MERRA-2 reanalysis data from 1984 to 2022. This dataset, available through NASA’s Power Data Access Viewer (https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/), has a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.625° and is publicly accessible. According to this data, for each node of grid cells in the sea area, the mean annual wind speed values for 1984–2004 and 2005–2022 were calculated, and maps of their distribution were developed in the geospatial environment using original grid of MERRA-2 reanalysis data.

To identify changes in wind directions over the Caspian Sea water area, MERRA-2 reanalysis data on the resulting wind projections at 10 m height (northward and eastward) were used for 1980–2022 (https://giovanni.gsfc.nasa.gov ). In the Cartesian coordinate grid, relative to the coordinate centre, the north and east winds have negative projections, while the south and west winds have positive projections. Therefore, if northward and eastward components are negative, the north and east wind components are predominant. However, sometimes, for ease of perception and comparison, we hereafter refer to northward and eastward winds in speed modules (Fig. 3).

According to the Northward and Eastward data, tan(α) and the corresponding resultant wind direction angles were found. In other words, the inverse problem was solved. As can be seen see in Fig. 3,

where α is the resultant wind direction in degrees relative to the north.

The resulting wind speed is calculated by the Equation:

Results

This section presents key findings on the relationship between CSL fluctuations and the primary hydrological and atmospheric factors influencing these changes. The results highlight the dominant role of river inflow, particularly from the Volga River, in determining sea level variations, while also accounting for the influence of evaporation, precipitation, and wind patterns. CSL is the outcome of the complex interactions of various water balance components, each differing in physical properties and formation conditions. The continuous variation in the ratio of inflow to outflow is driven by climatic factors that shape the formation and dynamics of these water balance elements. Additionally, the most influential climate system characteristics is atmospheric circulation, which serves as a primary driver of the processes that influence CSL fluctuations, including river runoff, evaporation, and precipitation. The uneven distribution of solar radiation across the globe is the main driver of these global circulation patterns1.

Analysis of historical data confirms that river discharge significantly impacts sea level trends, with the Volga River alone contributing more than 80% of total inflow. It should be noted that although evaporation from the surface has the greatest weight in the water balance, changes in the total flow of rivers flowing into the Caspian Sea play a significant role in the level fluctuations45. According to Georgievsky’s calculations, the role of the increase in total river runoff in the sea level rise of 2.45 m in 1978–1995 was 54%, the role of the decrease in evaporation from the sea surface was 29%, the role of the increase in precipitation falling on the sea surface was 10%, and the regulation of water discharge into the Kara-Bogaz-Gol Bay was 7%46. A similar assessment can be made for the period of level decline in 1930–1977, and it confirms that the role of general changes in river runoff in sea level fluctuations is large.

Figure 4a shows the time course of the annual runoff of the Volga River and all major rivers (Volga, Kura, Ural, Terek, Sulak, Sefidrud, Polrud, Shalus and Kharaz) flowing into the sea. The annual runoff of the Volga River and all the rivers flowing into the sea change in time almost synchronously, as the Volga River accounts for more than 80–85% of the total river runoff flowing into the Caspian Sea45,47. The curves of difference integrals of the Volga River runoff and all the rivers flowing into the sea are almost synchronous and parallel (Fig. 4b). Therefore, we will limit ourselves to using the Volga River flow data in further studies.

It is obvious that there is a relationship between Volga runoff, total river runoff and CSL (Fig. 4a). It is clearly manifested in the values of the difference integrals of river runoff calculated by formula 3 (Fig. 4b).

The relationship between the Volga River flow and the CSL can also be revealed by comparing the flow with inter-annual Caspian Sea level (DCSL) changes. Thus, DCSL was defined as the difference between the current sea level and the previous year. The correlation coefficients between the Volga runoff and DCSL calculated considering autocorrelation in time series is R = 0.56.

A closer look at Fig. 4b from 1938 to 2020 demonstrates a few notable periods when the river runoff and the sea level do not align. First, from 1947 to 1956, the slope of the curve corresponding to the sea level decrease was steeper than the slope of the Volga River flow. Additionally, from 1966 to 1976, the slope of the curve corresponding to the decrease in the Volga River runoff was steeper than the sea level decrease. In contrast, during 1956–1966, both curves were parallel and synchronous, suggesting that in this time interval, sea level changes were very strongly related to changes in the Volga River runoff.

During periods where river runoff and CSL do not align, other factors may play a role in CSL, most notably evaporation from the surface, which may increase and decrease during these periods. Wind dynamics, as discussed, can impact evaporation rates and water redistribution across the sea basin. Figure 5 (a and b) shows the distribution of annual mean wind speeds over the Caspian Sea area. The highest wind speeds are observed in the central parts of the Northern and Middle Caspian, and the lowest in the Southern Caspian, which show distinct characteristic differences during the periods in question.

Figure 5 (a and b) also suggests that data from coastal observation points cannot sufficiently and reliably characterize the wind regime of the entire Caspian Sea area. In these figures the wind gradually decreases from the centre to the periphery. This is important to consider as previous research from Arpe et al. 2020 about a significant increase in wind speed was using Iranian coastal stations, which cannot be attributed to the entire sea area.

Table 4 further shows the mean annual wind speed calculated in the ArcGIS platform for the periods under consideration over the entire water area. This demonstrates that the variability of wind speed over time is also not significant in all three areas of the Caspian, nor across the whole sea area. Differences between them do not exceed ± 0.2 m/s (Fig. 5c) and are not statistically significant at the significance level of 0.05 (assessed by Student’s criterion36.

However, wind characteristics may still be linked to changes in the CSL. Figure 6a shows the time course of the annual resultant northward wind component from 1980 to 2023, which decreases sharply in absolute value from 1997 onwards. During this period, the northward component has the highest values in 1997–1998 and the lowest in 2021 (in absolute value). In contrast to northward, the eastward component of the wind in absolute value increased with time (Fig. 6b). Its highest value was observed in 1996 when there was a sharp decrease in the CSL after reaching its highest level in 1995. A significant reduction in the Volga River flow also accompanied the sharp increase in the eastward component. Then, in 1997, the eastward component sharply decreased by |-1.5| m/s, and until 2004, it varied within the range of | (− 0.5) -(-1.2) | m/s. Starting from 2005, it varied within the | (-0.7) -(-1.9) | m/s range. This period is characterized by an almost constant decrease in sea level. It should be noted that a significant reduction in the eastward wind speed (in absolute value) was found during the period of CSL rise33.

Table 5 shows the resultant wind characteristics of the Caspian Sea. The resultant wind should not be confused with the average wind, which is determined without considering its direction. From 1996 to 2023, compared to 1980–1995, average northward winds across the entire Caspian Sea area decreased by 16.2%, and eastward winds increased by 23.4% (in absolute value). After 1995, the resultant wind direction angle, calculated by Eqs. 4 and 5, increased by 9.9° towards the east compared to the previous period. In the North Caspian, the northward wind decreased by 71.6%, and the eastward wind increased by 49% (in absolute value), increasing the wind direction angle of 17.6° towards the east. During the same periods in the Middle Caspian Sea, the decrease in the northward wind was 52.5%, and the increase in the eastward wind was 31.9% (in absolute value). Consequently, the resulting wind direction angle increased by 20.9° to the east.

In the South Caspian, in contrast to the North and Middle Caspian, the northward wind component increased slightly (5%) during the sea level decrease, while the increase in the eastward wind was 19.8% (in absolute value). The angle of deviation of the resulting wind direction angle to the east was insignificant (4.0°). In general, an increase in Northward is accompanied by a decrease in Eastward and vice versa. For the entire Caspian Sea area, the coefficient of inverse correlation between them is R = − 0.52. The Granger Causality test supports this conclusion, as Table 6 demonstrates a statistically significant relationship between the eastward and northward wind components, with the strongest influence observed at lag 1 and maintained up to a delay of three years (Table 7). This indicates that the response of the northward component to variations in the eastward wind may be delayed by up to three years. Although the strength of this response weakens over time, its statistical significance persists throughout the examined lag period.

Thus, it can be concluded that, compared with the period of sea level rise (1980–1995), during CSL decline (1996–2023), significant changes occurred in the wind regime: the eastward component increased, and the northward component decreased. Particularly significant changes in wind directions appear in the Middle Caspian, where the increase in the eastward components and the decrease in the northward component are the most significant. Eastward wind distribution patterns over the sea area for 1980–1995 and 1996–2023 also confirm the above (Fig. 7).

Discussion

The results confirm the changes in the wind regime of the Caspian Sea in different periods of its increase and decrease, as stated by other studies28,29. However, we also quantitatively assessed these changes for the sea’s entire water area and separate regions (North Caspian, Middle Caspian, and South Caspian). As a result, we observed changes in the wind regime in the Caspian Sea that led to an increase in evaporation from its surface, which ultimately is one of the reasons for the sharp decrease in the CSL in recent years. DCSL and the evaporation have a significant relationship at R=-0.61 (Table 6).

The Granger Causality test also reveals a strong statistical relationship between evaporation and detrended Caspian Sea level (DCSL) fluctuations (Table 7). The analysis indicates that the response of DCSL to changes in evaporation can exhibit a lag of up to five years while remaining statistically significant. However, the strongest response is observed with a one-year lag, after which the influence gradually diminishes with increasing lag time. This result is expected, as evaporation constitutes one of the principal components of the Caspian Sea water balance (see Eq. 2).

While Arpe et al.28 and Vyruchalkina et al.29 provided valuable insights into Caspian Sea dynamics, the present study adopts a distinct research focus and methodology, offering an original contribution that complements and broadens the existing body of knowledge. As previously mentioned, Arpe et al.28 also studied the influence of the wind regime on the CSL changes, however only the V component of the wind direction was considered along with mean velocity. In our study, this V component is captured as “northward wind.” The opposite signs of the correlation coefficient between DCSL and V obtained in Arpe et al.28 and in our work (0.413 and − 0.40, respectively) attract attention, which is cause for attention. If we consider that a positive sign of V corresponds to winds from the south, then a positive sign of the correlation coefficient between V and DCSL would imply an increase of the latter with increasing winds from the south or decreasing winds from the north. Since this conclusion is misleading, the sign of the correlation coefficient must be negative. In Vyruchalkina et al.29, the influence of wind direction on sea level was studied without considering the influence of individual wind components quantitatively. In contrast to our approach, their analysis focused on the recurrence frequencies of easterly and northerly winds. Nevertheless, the conclusions presented in that study are consistent with our quantitative findings regarding the overall relationship between sea level variability and wind characteristics.

As shown in Tables 6 and 7, both the northward and eastward wind components exhibit moderate relationships with detrended Caspian Sea level (DCSL). However, the eastward component demonstrates higher correlation coefficients and stronger Granger causality scores, indicating a more pronounced influence. Despite this, the strength of the impact diminishes progressively with increasing lag time.

The presence of a close relationship between the two wind components is further supported by the Granger causality test results (Table 7), which confirm a statistically significant interdependence. Physically, this can be explained by the nature of the wind blowing from different directions. When winds with predominantly northerly components blow, an upwelling phenomenon occurs in the eastern part of the sea under the influence of Coriolis force, which significantly cools the sea’s surface22. When easterly wind components prevail, the resulting surface currents transport warmer water masses from the southern part of the sea to higher latitudes. Thus, we believe that wind affects evaporation in direct and indirect ways.

As expected, we found a relationship between SST and evaporation (R = 0.68) (Table 6). The existence of a close relationship between SST and evaporation is confirmed by Granger causality test (Table 7), which shows the presence of a moderate significant response only in the first lag.

As shown in Fig. 8, changes in the wind regime over the Caspian Sea need to be considered when estimating CSL fluctuations. We found that the annual mean value of eastward/northward, which characterizes the direction of the resultant wind, was 1.43 from 1980 to 1995 and became 2.10 from 1996 to 2023 (Table 5), indicating a decrease in the northerly and an increase in the easterly wind components. This situation contributed to an increase in evaporation from the sea surface and, ultimately, to a decrease in sea level under conditions of unchanged or decreased inflow part of the water balance, especially the flow of the Volga River. The changes in sea level and wind regimes in the Caspian region are related, and the factors influencing their changes are similar. Changes in the wind regime affect the intensity of evaporation and the precipitation regime.

It is known that changes in the water balance, and therefore the level of the Caspian Sea, are mainly associated with climatic factors, which are usually expressed in the values of various climatic indices: Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), North Atlantic Oscillation index (NAO), Oceanic Niño Index (ONI), Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation index (AMO), The North Sea–Caspian Pattern Index (NCPI), etc16,48,49,50,51. Several studies show that these phenomena dramatically affect the global climate and lead to droughts, heavy rainfalls, and associated floods and inundations7,28,50,52,53,54. The mechanism of these indices’ impact on the Caspian region is still unclear. However, a phenomenon such as El Niño (negative phase of SOI) or NAO, being thousands of kilometres away from the Caspian region, can affect the region through the general circulation of the atmosphere, more precisely through air currents. Therefore, looking for a link between climate indices and wind characteristics in the Caspian region would be logical.

Here, we will consider the influence of only two indices, SOI and NAO, on the wind regime and the changes in the CSL. SOI is calculated from the difference between the atmospheric pressure values at the island of Tahiti in the central Pacific Ocean and at the Northern Australian city of Darwin6,55. Thus, the Southern Oscillation reflects the atmospheric situation over the western Pacific. Positive values represent La Niña events, and negative values represent El Niño events. NAO is a large-scale displacement of atmospheric masses between the Azores maximum and the Icelandic minimum. The North Atlantic Oscillation index is calculated as the pressure difference between the Icelandic minimum and the Azores maximum1,30,48,56,57,58. The NAO should primarily influence the changes in the CSL due to its proximity to the sea location5. However, the works of some researchers point to the advantage of SOI among other climate indices despite the remoteness from the sea6,28.

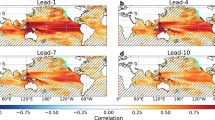

Table 6 shows the values of correlation coefficients between climatic indices (SOI, NAO) and some characteristics of wind and the CSL. The correlation coefficients between CSL and the SOI and NAO climate indices are insignificant. Much closer correlations are observed with DCSL. At the same time, compared to NAO (R = 0.24), the relationship between SOI and DCSL is more unambiguous (R=-0.51). There is a very low inverse relationship between SOI and NAO (R=-0.153) (Table 6). It should be noted that these data agree well with the data obtained in Arpe et al. 2020, who used actual observational data from the Iranian coast of the Caspian Sea. The Granger Causality Test confirms that the SOI exhibits a stronger statistical association with detrended DCSL than NAO (Table 7). As shown in Table 7, while the NAO does not demonstrate a statistically significant causal relationship with DCSL, the SOI maintains a robust and significant influence, with a response lag extending up to four years. However, the strength of this causal relationship decreases notably with increasing lag time.

Some characteristics of winds in the Caspian region also have links with sea level fluctuations (DCSL). The newly introduced characteristics – speed of the resultant wind Vresultant was more informative than the average wind speed Vaverage. (Tables 6 and 7).

The climate indices considered here and the resulting wind characteristics in the Caspian region have relatively close relationships with interannual sea level changes (DCSL). The study of the possible relationship between the climatic indices and the resulting wind characteristics is also of great interest in identifying possible factors influencing changes in the wind regime in the Caspian Sea region. Neither SOI nor NAO have a noticeable correlation with the mean annual wind speed over the Caspian Sea area (see Table 6). However, no discernible changes in mean annual wind speed were found during periods of sea-level rise and fall (see Fig. 5).

Noticeable correlations were found between the considered climatic indices and the resulting wind characteristic (Vresultant) (see Table 6). SOI and NAO have opposite signs of correlation coefficients with the resultant wind characteristics, resulting in different combinations of their development trends that may result in different resultant wind situations.

Thus, changes in the wind regime in the Caspian region are influenced by SOI and NAO simultaneously28. These significantly impact sea surface evaporation, air and sea surface temperature, and, ultimately, sea level variations.

As Table 6 shows, the correlation coefficients between CSL and the climate indices, wind characteristics, and water balance elements of the sea discussed above are not significant. This fact is also revealed in28. This is understandable since, according to Eq. 2, the CSL does not depend on the current values of the water balance elements but on their time-integrated values (difference integrals), calculated according to Eq. 3. These can also include climate indices and wind characteristics. Figure 4b shows a close relationship between CSL and the difference integrals curves of the annual Volga River runoff. The SOI and NAO difference integrals correlate well with CSL, but the correlation coefficient (R = -0.72) for SOI is more significant than that for NAO (R = 0.41) accounting for autocorrelation.

As can be seen in Table 7, the Granger Causality Test also confirms this. Although in the first lag (year) there is no significant response of CSL from the integral SOI, starting from the second-year significant responses appear with lags from 2 to at least 5 years.

CSL also correlates well with the integral wind characteristics, especially the resultant wind speed. Figure 9 further demonstrates this by showing the joint difference-integral curves against CSL variation. It should be noted that such an approach was also applied in29 to identify a possible relationship between the repeatability of winds of different humbles and sea level, and rather high values of correlation coefficients were obtained.

This relationship is also evident in broader time intervals (Fig. 10). Due to the negative correlation, the year the CSL reaches its highest level coincides with the year that the SOI curve was at its lowest, and vice versa. The intermediate maxima mostly coincide with the corresponding minima as well. The close correlation of climatic indices, especially SOI with CSL and Vresult, suggests that the influence of the former on sea level fluctuations is realized through air flows, which form a peculiar wind regime during periods of sea level rise and fall in the Caspian region. Quite large values of the correlation coefficients with CSL show that SOI and the vector of the resultant wind affect not only evaporation but also the other elements of the water balance (river runoff and precipitations).

It should be noted that the mechanism of SOI’s impact on the CSL change has yet to be made entirely clear so far28,30,49,52,53,54. However, with the rise in sea level, the absolute value of the eastward wind decreases, and the northward wind increases (Table 5). As is known, the El Niño phenomenon is a negative phase of SOI, during the activation of which the high-pressure centre is in the central equatorial part of the Pacific Ocean and the low-pressure centre in its eastern part. Therefore, at El Niño in the general atmospheric circulation, the westerly wind component is intensified in all tropospheric layers. Strengthening the westerly wind component weakens the eastward wind, and at the same time, due to a negative correlation, the northward wind increases (Table 5). As a result, evaporation intensity decreases, and the probability of precipitation increases. This process can be strengthened or weakened depending on the NAO index trend. When the positive phase of SOI (La Nino) is activated, the above processes go in the opposite direction, i.e., eastward wind increases, northward wind weakens, evaporation increases, precipitation decreases, and sea level decreases. This means that the long-term forecast of sea level changes depends on the success of SOI and NAO forecasts.

Arpe et al.28 demonstrated that both the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) and the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) influence the position of the jet stream over the Caspian Sea. The SOI exerts its effect through changes in the Walker circulation, while the NAO is often associated with atmospheric blocking over Europe, which in turn alters the jet stream trajectory. Weather anomalies in the region are closely linked to both surface-level and upper-atmospheric circulation anomaly patterns51.

Recent studies by59 have revealed that there is a rather close relationship between ENSO and NAO, which may also help in understanding the mechanism of ENSO’s long-range effects. All this once again proves the significant role of the oceans in changing the global climate60, including the wind regime, which in turn affects the CSL fluctuation.

It should be noted that the responses of other semi-enclosed seas (level changes) such as the Mediterranean and Black Sea to the various indices are less marked because of some of their connection to the global ocean. For example, during the maximum positive and negative phases of the NAO, sea level changes in these seas are less noticeable (up to 5–10 mm/year) than in the Caspian Sea, and the changes can be opposite in different parts of these seas61. However, the different phases of individual climatic indices affect the recurrence of cyclones and anticyclones occurring over the sea surface and, accordingly, the wind regime62.

Conclusion

In this study, new, more informative wind parameters (eastward/northward and Vresult) were proposed, characterizing the direction and speed of the resulting wind over the entire sea area using its eastern and northern components. This made it possible to determine more clearly the changes in the wind regime during the periods of sea level rise and fall. It was found that during the period of sea level fall (1996–2023), the average direction of the resultant wind increased by 9.90 and the resultant wind speed by 11.6% over the entire Caspian Sea area, which led to an increase in evaporation and sea level fall. These rates may differ slightly for individual parts of the sea. The correlation coefficients of these wind characteristics with sea level changes (DCSL) are R > ǀ0.5ǀ which are more significant than for the mean wind value (R=-0.21).

It was found that the mean annual wind speed over the entire sea area during the period of sea level lowering (2005–2022) did not change significantly compared to the period of sea level rise (1984–2004). Its increase in one part of the sea was followed by its decrease in the other part.

It is also shown that there is some relationship between the considered climate indices (SOI & NAO) and wind in the Caspian region, which is well manifested in the characteristics of the resulting wind, while the relationship with mean speed (Vaverage) is not significant. It is established that there is a correlation between DCSL and the climatic indices SOI and NAO, but the relationship with SOI is closer than with NAO. It is revealed that the current values of wind characteristics (resultant) and the considered climatic indices mainly influence DCSL. In contrast, CSL is best influenced by their integral values (difference integrals), evident from the Caspian Sea water balance. Relatively close causal relationships of SOI with CSL and characteristics of the resulting wind show that the former effects CSL by changing the wind regime in the Caspian region, on which evaporation intensity and precipitation depend to a certain extent. High values of correlation coefficients and close similarity of CSL and SOI time curves (difference integrals) may open the possibility of long-term forecasting of the former using the latter’s forecast.

The Granger causality test showed that SOI significantly influenced Caspian Sea level (CSL) and detrended CSL (DCSL) at lags 1–5 (p < 0.01), suggesting that large-scale atmospheric circulation associated with ENSO affects regional precipitation, inflow, and evaporation patterns. Evaporation showed the strongest causal link with CSL and DCSL (p < 0.01, lags 1–5), reflecting its direct role in modulating the water balance of the closed basin. Increased evaporation under warmer or windier conditions contributes to sea level decline.

Caspian Sea surface temperature (SST) also significantly affected CSL and DCSL (p < 0.01), likely through enhanced latent heat flux and feedback on evaporation and atmospheric stability. Eastward wind components influenced CSL and DCSL at lags 1–5 (p < 0.01), likely by increasing surface evaporation and redistributing water masses. Northward wind had a weaker but significant effect on DCSL, possibly via regional moisture transport.

In contrast, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index and Volga River discharge (VRD) showed no significant influence, indicating limited short- to mid-term impact on sea level. Causal links among variables showed that eastward wind affects SST, which in turn drives evaporation, forming a feedback chain in the ocean–atmosphere system.

In summary, the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), evaporation, sea surface temperature (SST), and eastward wind may be considered the most influential drivers of Caspian Sea level (CSL) variability at lags of 1 to 5 years, operating through interconnected climatic and hydrological processes.

In addition to advancing scientific knowledge, these findings have practical significance for improving the accuracy of sea level prediction models under changing climatic conditions. A better understanding of wind-driven mechanisms influencing evaporation and the regional water balance can support coastal infrastructure planning, risk assessment, and water resource management in Caspian-bordering countries.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Nesterov, E. S., Nesterov, E. S. & Greece Water balance and level fluctuations of the Caspian Sea. In: Ltd T,Modeling and Forecast 378 (Russian: Piraeus, 2016).

Koriche, S. A., Nandini-Weiss, S. D. & Prange, M. E. Impacts of variations in Caspian sea surface area on catchment-scale and large-scale climate. JGR Atmos. 126(18) (2020).

Farley-Nicholls, J. & Toumi, R. On the lake effects of the Caspian sea. Q. J. R Mete-orol Soc. 140 (681), 1399–1408 (2014).

Chen, J. L., Pekker, T. & Wilson, C. R. others. Long-term Caspian sea level change. Ge-ophys. Res. Lett. 44, 1–9 (2017).

Panin, G. N., Mamedov, R. M. & Mitrofanov, I. V. The Current State of the Caspian Sea; Nauka: St. Petersburg, Russia. 356. (2005).

Arpe, K., Bengtsson, L. & Golitsyn, G. S. others. L. Connection between Caspian sea L.vel variability and ENSO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27 (17), 2693–2696 (2000).

Safarov, E. S., Rodrigo, A. D. R. & Safarov, S. H. others. El Niño phenomenon and Caspian sea level fluctuations. Hydrometeorology Ecol. 1, 7–14 (2017). (in Russian).

Lahijani, H., Leroy, S. A. G., Arpe, K. & Crétaux, J.-F. Caspian sea level changes during instrumental period, its impact and forecast: A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 241, 104428 (2023).

Safarov, E. S. Investigation of the Caspian sea level fluctuations. Baku 164 (2024). (in Azerbaijani).

Woolway, R., Kraemer, B., Lenters, J. M., O’Reilly, C. & Sharma, S. Global lake responses to climate change. Nat. Reviews Earth Environ. 1, 388–403 (2020).

Ozyavas, A., Khan, S. D. & Casey, J. F. A possible connection of Caspian sea level fluc-tuations with meteorological factors and seismicity. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 299, 150–158 (2010).

Kovachev, S. A., Kazmin, V. G., Kuzin, I. P. & Lobkovsky, L. I. New data on seismicity of the middle Caspian basin and their possible tectonic interpretation. Geotectonics 40(5), 367–376 (2006).

Demin, A. P. Present-day changes in water consumption in the Caspian sea basin. Water Res. 34, 237–253 (2007).

Telesca, L., Babayev, G. & Kadirov, F. Temporal clustering of the seismicity of the Absheron-Prebalkhan region in the Caspian sea area. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 12, 3279–3285 (2012).

Lattuada, M., Albrecht, C. & Wilke, T. Differential impact of anthropogenic pres-sures on Caspian sea ecoregions. Mar. Poll. Bull. 142, 274–281 (2019).

Panin, G. N., Solomonova, I. V. & Vyruchalkina, T. Y. The regime of the components of the water balance of the Caspian sea. Water Resour. 41, 488–495 (2014).

Shiklomanov, V. Y. I. A. & Georgievsky The influence of economic activities on the water balance and changes in the level of the Caspian Sea. in: Aspects, H. (Ed), Of the Problem of the Caspian Sea and Its Basin; Gidrometeoizdat Petersburg, Russia, pp 267–277. (2003) (In Russian).

Samant, M. R. & Prange Climate-driven 21st century Caspian Sea level decline esti-mated from CMIP6 projections. Communications Earth and Environment 4, 357 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01017-8 (2023).

Pavlova, G. A., Myslenkov, S. & Arkhipkin, V. Surkova. Storm surges and extreme wind waves in the Caspian sea in the present and future climate. Civil Engineering Jour-nal 8, 2353–2377 https://doi.org/10.28991/CEJ-2022-08-11-01 (2022).

Lebedev, S. A., Sirota, A. M., Ostroumova, L. P. & Kostyanoy, A. G. Calculation of evap-oration from the Caspian Sea using remote sensing data [Electronic resource] [Internet]. Available from: http://d33.infospace.ru/d33

Ataei, H. S., Jabari, K. A. & Khakpour, A. M. others. Long-term Caspian sea level varia-tions based on the ERA-interim model and rivers discharge. Int. J. River Basin Manage. 17 (4), 507–516 (2019).

Safarov, S., Valizadeh Kamran, K., Ismayilov, V. & Safarov, E. Detection of upwelling events in the Caspian sea using thermal satellite image processing. Int. J. Eng. Geosci. 9 (2), 247–255 (2024).

Abuzyarov, Z. K. Role of the Caspian Sea water balance components in monthly and annual increments of its level. In: Proc of the Hydrometeorological Centre of the Russian Feder-ation Hydrometeorological Centre of the Russian Federation 341. pp. 3–27. (2006).

Safarov, E., Safarov, S. & Bayramov, E. Changes in the hydrological regime of the Volga river and their influence on Caspian sea level fluctuations. Water 16 (12), 1744 (2024).

Terziev, S. F. (ed.) Hydrometeorology and hydrochemistry of seas. in The Caspian Sea. Hydrometeorological conditions, Vol. 6. 360 (Gidrometeoizdat, 1992) (In Russian).

Imrani, Z., Safarov, S. H. & Safarov, E. S. Analysis of Wind-wave characteristics of the Caspian sea based on reanalysis data. Russ. Meteorol. Hydrol. 47 (6), 479–484 (2022).

Kruglova, E. & Myslenkov, S. Influence of Long-Term wind variability on the storm activity in the Caspian sea. Water 15, 2125 (2023).

Arpe, K., Molavi-Arabshahi, M. & Leroy, S. Wind variability over the Caspian sea. Its impact on Caspian seawater level and link with. ENSO Int. J. Climatology. 14, 6039–6054 (2020).

Vyruchalkina, T. Y., Diansky, N. A. & Fomin, V. V. Effect on level evolution of the Cas-pian sea, long-term changes in the wind regime over its region in 1948–2017. Water Resour. 47, 230–240 (2020). (In Russian).

Serykh, I. V. & Kostianoy, A. G. The links of climate change in the Caspian sea to the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Russ. Meteorol. Hydrol. 45, 430–437 (2020).

Aliyev, A. S. & Veliev, S. S. Dynamics of changes in the Caspian sea level in historical time and the near future. Meteorol. Hydrology. 3 (in Russian), 79–87 (1999).

Azizpour, J. & Ghaffari, P. Low-frequency sea level changes in the Caspian sea: long-term and seasonal trends. Clim. Dyn. 61(5–6), 2753–2763 (2023).

Panin, G. N. & Dzuyba, A. V. Current variations in the wind speed vector and the rate of evaporation from the Caspian sea surface. Water Res. 30(2), 177–185 (2003).

Bolgov, M. V. Caspian sea. In Encyclopedia of Lakes and Reservoirs (eds Bengtsson, L. & Fairbridge, H.) 136–141 (Springer, 2012).

Esri. World Imagery [basemap]. Available from: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=10df2279f9684e4a9f6a7f08febac2a9 (2025).

Förster, E. & Röntz, B. Methods of Correlation and Regression Analysis. Manual for econo-mists. Translation from German and Foreword by V. M. Ivanova (`Finance and Sta-tistics’, -;, 1983).

Wilks, D. S. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences 3rd edn (Academic, 2011).

Hyndman, R. J. & Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. OTexts; (2018).

Safarov, S. H. & Safarov, E. S. Characteristics of modern level changes of the Caspian Sea. In: conference III scientific-practical, editor. Modern problems of geography. 2023. Baku, 2023, Vol. 1, (in Azerbaijani: November 22–23); pp. 56–65. (2023).

Tulger Kara, T. G. & Elbir Evaluation of ERA5 and MERRA-2 Reanalysis Datasets over the Aegean Region, Türkiye. DEUFMD 26, 9–21 (2024). [Internet]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21205/deufmd.2024267602

Gelaro, B. R. et al. The Mod-ern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MER-RA-2). Journal of Cli-mate 30, 5419–5454 [Internet]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0758.1 (2017).

Jin, C. S., Lin, Y. H. & Huang, P. C. Evaluation of wind energy potential using MERRA-2 and ERA5 in offshore East Asia. Renew. Energy. 164, 388–404 (2021).

Rienecker, M. M., Suarez, M. J. & Gelaro, R. others. MERRA: nasa’s Modern-Era retrospective analysis for research and applications. J. Clim. 24 (14), 3624–3648 (2011).

Gelaro, R. et al. The Modern-Era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (MER-RA-2). J. Clim. 30 (14), 5419–5454 (2017).

Bolgov, M. V., Korobkina, E. A., Trubetskova, M. D. & Filippova, I. A. River runoff and probabilistic forecast of the Caspian sea level. Russ Meteorol. Hydrol. 43 (10), 639–645 (2018).

Georgievsky, V. Y. Changes in the Flow of Russian Rivers and Water Balance of the Caspian Sea under the Influence of Economic Activity and Global Warming. Ph D Disserta-tion, State Hydrological Institute, St Petersburg, Russia. 44, (2005). (In Russian).

Leroy, S., Lahijani, H. & Crétaux, J. F. others. Past and current changes in the largest lake of the world: the Caspian Sea. In: Large Asian Lakes in a Changing World (ed. Mischke, S.) pp. 978–3. (New York, NY: Springer, 2020).

Molavi-Arabshahi, M., Arpe, K. & Leroy, S. Precipitation and temperature of the Southwest Caspian sea region during the last 55 years: their trends and teleconnections with large-scale atmospheric phenomena. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 2156–2172 (2015).

Nesterov, E. S. N. A. Oscillation: Atmosphere and Ocean (– M.: Triada, Ltd. – (in Russian, 2013).

Semenov, V. A. & Cherenkova, E. A. Assessing the influence of the Atlantic multide-cadal Oscillation on large-scale atmospheric circulation in the Atlantic sector in the summer season. Rep. Acad. Sci. 478, 6 (2018).

Türkeş, M. & Erlat, E. Variability and trends in record air temperature events of Turkey and their associations with atmospheric oscillations and anomalous circulation Pat-terns//International. J. Climatol. 38 (14), 5182–5204 (2018).

Zhang, R., Sutton, R. & Danabasoglu, G. others. Comment on the Atlantic Multide-cadal Oscillation without a role for ocean circulation. Science 352, 1527 (2016).

Ward, P. J., Jongman, B. & Kummu, M. others. Strong influence of El Nino Southern Os-cillation on flood risk around the world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 15659–15664 (2014).

Zebiak, S. E., Orlove, B. & Muñoz ÁG, others. Investigating El Niño-Southern Oscilla-tion and society relationships. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. Clim. Chang. 6, 17–34 (2015).

Mokhov, I. I. & Smirnov, D. A. Study of mutual influence of El Niño - Southern Oscilla-tion and North Atlantic and Arctic Oscillation processes by nonlinear methods. Bull. Russian Acad. Sci. Phys. Atmos. Ocean. 42 (5), 650–667 (2006).

Polonsky, A. B., Basharin, D. V., Voskresenskaya, E. N., Atlantic, W. S. N. & Oscillation Description, mechanisms, and impact on the climate of Eurasia. Mar. Hydro-physical J. 2, 42–59 (2004). (in Russian).

Hurrell, J. W., Visbeck, M. & Busalacchi, A. others. Atlantic climate variability and pre-dictability: a CLIVAR perspective. J Climate. 19(24), 5100–21. (2006).

Nandini-Weiss, S. D., Prange, M. & Arpe, K. others. Past and future impact of the winter North Atlantic Oscillation in the Caspian sea catchment area. Inter J. Climat. 40 (5), 2717–2731 (2020).

Scaife, A. A. et al. ENSO affects the North Atlantic Oscillation 1 year l later. Science 386(6717), 82–86 (2024).

Narosky, V. Effects of the world’s oceans on global climate change. Am. J. Clim. Change. 2, 183–190 (2013).

Aksoy, A. Investigation of Sea Level Trends and the Effect of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) on the Black Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Online First: Theor (Appl. Climatol, 2016).

Bazyuraa, E. A., Gubareva, A. V. & Polonskii, A. B. Impact of the Scandinavia and East atlantic/western Russia patterns on wind stress curl over the black sea. Russ. Meteorol. Hydrol. 49(10), 866–875 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Reviewers 1 and 2 and the Editor for their insightful comments.

Funding

This study was funded by the Nazarbayev University through Collaborative Research Program (2024–2026) - Funder Project Reference: 211123CRP1606, Faculty Development Competitive Research Grant (FDCRGP) (AI and Data Science) (2024–2026) - Funder Project Reference: 201223FD2607, Faculty Development Competitive Research Grants Program (2025–2027) - Funder Project Reference: 040225FD4735 and 2021/2022 - SWISS GOVERNMENT EXCELLENCE SCHOLARSHIP Program (Personal ESKAS-Nr: 2021.0008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.S., E.B., S.S. wrote the main manuscript textE.S., E.B., S.S. created all maps and performed analyses E.S., E.B., S.S., J.N. and A.H. edited the main manuscript text E.S., E.B., S.S., J.N. and A.H. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Safarov, E., Bayramov, E., Safarov, S. et al. Impact of changes in the wind regime on the Caspian sea level fluctuation and its relationship with SOI and NAO. Sci Rep 15, 36380 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20346-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20346-6