Abstract

A limited understanding of the potential to reduce emissions and a lack of climate incentives hinder progress toward mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from beef production. This study explored the GHG mitigation potential in South America by evaluating nearly 30 beef cattle production systems across five key beef-producing countries (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Paraguay, and Uruguay). The study outlined a low-emission beef roadmap for this major beef producing region. Data from this study indicate that the current business-as-usual trajectory of improvements in South America’s beef cattle production is insufficient to reduce GHG emissions at a pace that aligns with the urgency of climate crisis. Results from this study show that scaling up existing practices -such as improved forages, rotational grazing, and feed supplementation- to match the performance of the region’s lowest-emission systems at 20thpercentile could deliver significant results. Emission intensities could decrease by 33–50% compared to the projected 2050 regional average (35 tons carbon dioxide equivalent/ton of carcass weight). This would flatten the emissions curve, cutting total emissions by 20–40% while simultaneously increasing beef production by 43%. With annual methane (CH4) emission reductions by 1.5%, the warming effect could decrease by 70–90%, offering a transformative pathway to lower GHG emissions from beef production. This emissions trajectory offers a feasible path toward net-zero warming from beef production, primarily through sustained reductions in CH4 emissions intensity and absolute emissions as systems become more production efficient. These findings highlight the need and an opportunity for a drastic reduction in emissions from beef cattle production and can foster collaboration among conservation, industry, and finance stakeholders towards a common climate-oriented beef production agenda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Paris Agreement’s objective to limit global temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels hinges on significant contributions from climate solutions within food systems1,2,3,4. The global mitigation effort especially needs to address greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from beef cattle production. Currently, global food systems contribute approximately one-third of total GHG emissions, that is close to 20.0 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year (GtCO2e/year), with the beef value chain alone responsible for generating 34% (around 7.0 GtCO2e ) of these emissions5,6,7.

Projections indicate a 40% increase in beef production by 2050 compared to current levels8,9. If met through existing practices, emissions from this value chain could escalate to about 11.0 GtCO2e/year, negatively impacting biodiversity and water resources, and jeopardizing global climate and environmental targets1. However, beef production offers significant mitigation potential. Adopting existing technologies to improve global beef production efficiency could reduce emissions by 70%, lowering them from 7.3 to 2.5 GtCO2e/year while meeting 2050 food demands5. This mitigation potential is especially relevant for regions with lower productivity systems, such as South America, where over a quarter of global beef production originates3,10,11.

Although significant productivity improvements have happened, South America’s beef production has still relied on expanding cattle herds and pasture areas, with productivity lagging potential. Between 1990 and 2020, pasture area in South America increased by 23%, the cattle herd by 30%, and beef production by 70%12,13. Large areas of degraded pastures, estimated at 90 million hectares, contribute significantly to this inefficiency13. South America houses approximately 80% of developing countrie’s cultivated pasture area and most livestock keepers widely plant African grasses14. Implementing efficient pasture and animal management practices in the region could increase beef productivity to over 200 kg of beef per hectare per year, more than three times the current rate15,16. This increased productivity could free up 49 million hectares of land by 2030, which is crucial given the projected expansion of crop cultivation in the region17.

Changes in livestock production and management practices can deliver substantial GHG mitigation while improving beef productivity. Improved pasture management—through pasture restoration, the use of high-quality forage varieties, and rotational grazing—lowers emissions intensity by enhancing forage yield and nutritional quality, enabling faster liveweight gain and shorter production cycles11,18. Complementary measures such as supplementary feeding and genetic improvements further enhance feed efficiency and animal performance. In addition, silvopastoral and agroforestry systems can improve system resilience, sequester carbon, and contribute to further reduction in GHG emissions18,19,20,21.

Collectively, these strategies reduce emissions intensity and, when combined with more efficient herd management, can also lower absolute emissions. Because methane (CH4) is the dominant GHG emitted by pasture-based beef systems, this mitigation pathway offers a unique opportunity to neutralize its warming effect over time—bringing the sector closer to a net-zero warming trajectory5,15. As a short-lived climate pollutant, a sustained annual decline of approximately 0.35% in CH4 emissions is required to halt its additional contribution to global warming—an effect comparable to reaching net-zero carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. This threshold is derived using the Global Warming Potential star (GWP*) metric, which accounts for the distinct atmospheric lifetimes and warming behaviors of CH4 compared to long-lived gases like CO222. This distinction is critical, as only sustained reductions in absolute CH4 emissions—not intensity alone—can deliver long-term climate benefits under a warming-based accounting framework.

However, independent actions towards sustainability—through livestock, farm, and land management—can sometimes work at cross purposes. Concerning the potential negative consequences of production intensification, including the risk of increased absolute emissions despite reduced emissions intensity. More profitable livestock systems could incentivize both beef production and pasture expansion. These outcomes lead some observers to raise the question of whether the focus should shift towards reducing meat consumption via a plant-based diet instead of solely improving beef production23.

In this context, this study introduces a novel aspect to the topic by addressing the intersection of mitigation potential and production efficiency in South America’s beef sector. Unlike previous studies, which often focus on single countries15,24,25, this study is the first to collect and analyze data across multiple key countries in South America, providing a regional perspective. By quantifying their potential to simultaneously meet future production demands and significantly mitigate GHG emissions, the study fills a critical knowledge gap. To accomplish these objectives, the study conducted a review and evaluation of nearly 30 beef cattle production systems across five major beef-producing countries in South America accounting for about 90% of the beef production in South America in 2020: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, AParaguay, and Uruguay12. GHG emissions intensities—measured as tCO2/t carcass weight (cw)—for these livestock systems were quantified using a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) approach. Subsequently, the study estimated the productivity gap and mitigation potential based on 2050 beef production projections. Finally, to align South America’s livestock systems with global climate goals, the study explored the potential role of sustainable intensification and climate finance mechanisms, particularly carbon markets.

Results

Beef production systems, greenhouse gas emissions and land-use intensity

The beef cattle production systems in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Paraguay, and Uruguay, Colombia accounted for about 90% of the beef production in South America in 2020—representing both tropical and temperate beef production trends in the region12. In those five key countries, beef production systems exhibit similarities in terms of animal and pasture management, reflecting the shared environmental conditions and cattle-raising traditions across the region.

These countries primarily rely on grazing practices, where cattle are raised on grasslands and pastures. However, livestock production systems in these countries are also characterized by three levels of intensification: extensive, semi-intensive, and intensive systems (Table 1). Most grazing methods emphasize the use of native and improved grass species. Some systems employ rotational grazing. Animal feed supplementation and finishing on feedlots can complement pasture and grassland grazing (Table 1).

As pasture-based intensification occurs in beef cattle production systems in South America, feeding quantity and quality improve significantly. Feed digestibility increases by up to 28.6% (from 55.0% in extensive rearing systems to 71.2% in intensive finishing systems). Stocking rates more than double, rising from 0.40 animal units per hectare per year (AU/ha/yr) in extensive systems to 2.20 AU/ha/yr in intensive finishing systems. Meat production per unit area also increases, with carcass weight gains increasing from 70 kg carcass weight per head per year (kg cw/AU/yr) in extensive systems to at least 230 kg cw/AU/yr in intensive systems (Table 2).

Improved systems enhance nutrient intake and energy efficiency. Dry matter digestibility increases from 56.4% in extensive calving systems to 80.0% in feedlots, while metabolizable energy rises from 8.0 megajoules per kilogram (MJ kg-1) in extensive systems to 13.0 MJ kg-1 in feedlots. Crude protein content also increases, from 8.10% in extensive systems to 16.0% in feedlots, reflecting higher feed quality and nutrient availability (Table 2).

Pasture productivity increased in intensified systems, with biomass yields increasing from 8.3 tons of dry matter per hectare per year (tDM/ha/yr) in extensive systems to 15.8 tDM/ha/yr in intensive finishing systems. These improvements are supported by inputs, such as the annual application of 200 kg of urea fertilizer per hectare per year and approximately 400 kg of lime per hectare per year—inputs that are absent in extensive systems (Table 2).

However, intensified systems demand higher inputs, presenting trade-offs in resource use. Diesel consumption, for example, increases from zero in extensive systems to 28.74 L per animal unit per year (L/AU/yr) in intensive finishing systems and 295.9 L/AU/yr in feedlots (Table 2).

Overall, the transition from extensive to intensive systems in South America demonstrates the potential to significantly enhance beef production efficiency through better feed quality, higher digestibility, and increased stocking rates. However, it also underscores the importance of adopting practices that minimize resource use and environmental impacts to ensure sustainable intensification.

Assessing GHG emissions across various South America’s various beef production systems reveal a spectrum of emission profiles, shaped by their distinct approaches to cattle raising. Emissions intensity varied from 15.1 to 77.5 tCO2e/tcw and was predominantly influenced by CH4 emissions (r2 = 0.82). Methane accounted from 57 to 93% of total emissions (Table 3), notably attributable to animal enteric fermentation. In general, the more intensified the production system, the lower the contribution of animal emissions (especially CH4). However, more intensified production also increases emissions (N2O and CO2) from other farming operations, which are largely associated with pasture fertilization and feed production (Table 3).

Broadly, beef production systems that predominantly employ traditional extensive grazing tend to generate higher GHG emissions intensity (35.8–77.5 tCO2/t cw produced) compared to more intensive production systems that incorporate improved pastures, rotational grazing, and feed supplementation (Tables 1 and 3). These systems usually offer low animal feeding quantity and quality, which prevents animals from being finished within 24 months. Conversely, production systems that combine intensive pasture practices (e.g., pasture fertilization, feed supplementation and rotational grazing) with feedlot systems for finishing typically exhibit the lowest emissions intensity (15.1–22.5 tCO2/t cw produced). Meanwhile, systems incorporating semi-intensive use of inputs and interventions demonstrate an intermediate GHG emissions intensity (23.0–37.3 tCO2/t cw produced) (Table 3).

The variation in land-use intensity between the different systems is as notable as the variation in emissions intensity (Table 3). Extensive systems require 11.7–37.9 ha of agricultural land to produce 1 ton of carcass per year, which includes the area for cattle grazing as well as the areas for silage and crop production for cattle feed. This area decreases to 4.1–14.1 ha for the semi‒extensive systems and to 3.8–5.4 ha for the intensive systems, representing an average reduction of 63–81%, respectively (Table 3). This significant land-sparing effect could contribute indirectly to reducing emissions from deforestation and increasing removals through reforestation, as it may free up land for agricultural expansion, forestry, conservation, and restoration without the need for pasture expansion26. This comparative analysis underscores the importance of tailored mitigation strategies based on pasture intensification, considering the unique characteristics and challenges within each country’s beef production system8,10,27.

Mitigation potential with large scale intensification of pasture-based beef production in South America

In 2020, South America produced around 14.7 million tons of beef (cw), resulting in emissions of approximately 0.67 GtCO2e and an emission intensity of 41.6 tCO2/t cw8,12. To meet the growing market demand, South America is expected to increase beef production by 43%, reaching 23.1 million tons by 20508. The region has been steadily increasing its beef production over the last three decades12. Business-as-usual (BAU) productivity improvements are supposed to reduce beef production emissions intensity by only 15.9% by 2050 (to 35.0 tCO2e/t cw)8,12. GHG emission intensities from beef production for 2030 and 2050 were estimated using FAO-STAT emissions data and FAO-Outlook production projections, focusing on enteric fermentation and manure management while excluding carbon pool changes (e.g., soil carbon) and emissions from other farming production sources (e.g., energy, fertilizers, lime application, and feed production), likely to make estimates conservative.

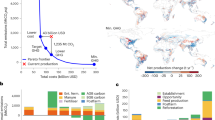

This level of BAU emission intensity, if maintained, falls short in reducing overall emissions. On the contrary, it would increase total GHG emissions by 20.9% (from 0.67 to 0.81 GtCO2e) by 2050 as the projected increase in beef production (43%) would outpace the level of mitigation (15.9%) (Fig. 1). Our study results indicate that the existing production systems in the region with emissions at the 20th percentile could potentially reduce emission intensities by 33% compared to the projected regional average by 2050 (35.0 tCO2e/t cw) (Table 3). The emissions level of these improved systems (23.5 tCO2e/t cw) could flatten the emission curve, reducing total emissions in 2050 by 20% compared to 2020 levels (from 0.67 to 0.54 GtCO2e) while producing 43% more beef (Fig. 1).

Total GHG emissions (bars, MtCO2e) and methane emissions (orange dots, MtCH4; values in italics) from South America’s beef production systems. Results are presented for the 2020 baseline (blue bar), the 2050 Business-as-Usual (BAU) projection (orange bar), and two intensified pasture-based scenarios: the Enhanced Scenario (green bar, representing the top 20th percentile of low-emitting production systems in the region) and the Enhanced Scenario + Soil Carbon Sequestration (gray bar, accounting for additional soil carbon gains from grasslands).

In parallel, improving pasture-based beef production systems with lower emission intensities may also unlock carbon sequestration in soils5. Roe et al.3 estimated a cost-effective soil carbon sequestration potential in grasslands at 139 MtCO2e/y over 2020–2050. Emission intensity for beef production in the region may reach 17.5 tCO2e/t cw and reduce total emissions by 40% compared to 2020 levels (Fig. 1). Taken together, these results indicate that the mitigation potential of large-scale pasture intensification is expected to deliver around a 30% reduction in total GHG emissions by 2050 compared to 2020 levels—positioned between a ~ 20% reduction when soil carbon sequestration is excluded and a ~ 40% reduction when it is included (Fig. 1). While carbon sequestration plays an important role in the enhanced scenario, the authors recognize that its contribution may plateau over time as soils approach new equilibrium levels. In this context, additional removals beyond 2050—such as through expanding agroforestry, novel forage systems, or engineered solutions—will be needed to sustain negative emissions.28,29,30,31.

While all emissions in this study are calculated and reported using the GWP100 metric, it is important to consider the warming implications of decreasing CH4 emissions using a complementary approach. Under the GWP* framework, a sustained CH4 emissions reduction of approximately 0.35% per year is sufficient to halt the additional contribution of CH4 to global warming over a 20-year period22,32. In the enhanced scenario, CH4 emissions are projected to decline by 1.5% per year by 2050—well above this threshold. Given that CH4 accounts for over 50% of total GHG emissions from these systems (Table 2), the ability to substantially reduce CH4 emissions and neutralize its additional warming effect, hile simultaneously increasing beef production, is needed to support this scenario.

Therefore, while total GHG emissions under GWP100 remain above zero, the net warming impact of on-farm beef production in South America could be reduced by 70–90% by mid-century, primarily through CH4 mitigation. This would position pasture-based intensification as a key strategy for substantially lowering emissions in beef production (Fig. 1). These improvements are made possible by reductions in emissions intensity—driven by gains in feed efficiency, animal productivity, and pasture quality—as well as structural changes that limit the number of animals and pasture area needed to meet projected beef demand, resulting in lower total emissions and freeing land for other uses (Table 3).

This dual benefit—climate mitigation through lower emissions and land-use efficiency through reduced stocking rates—highlights the transformational potential of improved beef cattle production systems. These systems could reduce the pasture area required for beef production in South America by 63–81% on average, freeing up more than 130 million hectares while still meeting projected beef demand by 2050. This contrasts sharply with the BAU scenario, which would require around 20% expansion (over 60 million hectares) in pasture area to meet the same demand (Table 3).

Not all pasture areas are suitable for intensification or alternative land uses. Many extensive systems are located on degraded or nutrient-poor soils that may require substantial investment to support crop production or afforestation. However, this does not suggest that land suitability is a constraint to intensification at scale. On the contrary, our findings indicate that improved pasture-based systems can meet future beef demand using a fraction of the land required by extensive systems, while delivering greater productivity (Table 3). This land-use efficiency creates opportunities to repurpose surplus pasture area for conservation, agroforestry, or ecosystem restoration. Strategically targeting intensification in moderately productive or restorable areas—rather than in highly degraded zones—may therefore unlock the greatest potential for both climate mitigation and climate-resilient land management.

Discussion

Intensified pasture-based beef cattle systems demonstrated lower emissions intensity compared to extensive systems. Therefore, adopting and disseminating improved production and management practices that enhance production efficiency should be the primary strategy towards reducing emissions in the South American beef industry. Effective emission intensity reduction relies on improving both animal and herd productivity rather than merely increasing productivity per unit area. In the enhanced scenarios, the primary emissions reductions were achieved through improvements in feed digestibility, feed conversion efficiency, and reduced time to slaughter—outcomes linked to production efficiency resulting from pasture improvement, supplementation, and better animal performance. These practices are currently deployable in pasture-based systems across South America, and align with several studies on sustainable beef production that prioritize pasture management and supplementary nutrition as a key first step in pasture intensification27,33.

For example, in the calving phase, emissions intensity is primarily influenced by the weaning rate. Better breeding practices, fixed-time artificial insemination, and effective cow management can reduce weaning rates. Enhancing pasture management and cow nutrition before breeding and during lactation further increases pregnancy rates and calf survival. Supplementary feeding for calves, or creep-feeding, also contributes to overall efficiency. Ranchers can increase productivity and reduce emissions by applying nature-based solutions, such as restoring degraded pastures and implementing rotational grazing. They can also build the necessary infrastructure for distributing supplements and water. Effective pasture management and supplementary nutrition are essential for reducing emissions intensity during rearing and finishing phases, by accelerating carcass weight gain and reducing the time animals remain in the system. Livestock producers could also adopt improvements in pasture management, including a combination of intensive pasture-based systems and feedlot systems for finishing. For optimal results, feedlot finishing should consist of a total mixed ration of 65–80% concentrate and 20–35% silage during the dry season33,34.

These findings align with other studies in South America15,24,25, which similarly highlight the relationship between management intensity and GHG emissions. For example, González-Quintero et al.24 and Becoña et al.25 observed that traditional systems with low feed quality are associated with higher emissions, whereas more intensive systems reduce emissions by improving feed conversion efficiency and animal productivity. Cardoso et al.15 further underscore the role of integrated practices, such as rotational grazing and targeted supplementation, in minimizing emissions and enhancing overall sustainability.

While intensification improves emissions and production efficiency, it may also require trade-offs. Extended confinement periods during feedlot for finishing can raise animal welfare concerns, and the adoption of high-performance breeds may reduce system resilience to climatic and health-related stressors compared to locally adapted breeds35,36. These dimensions are important to consider in scaling strategies and may influence adoption pathways in different contexts37.

In addition, several critical debates persist regarding intensification and its overall impact. First, enhancing pasture conditions could potentially lead to an increase in herd sizes and related emissions rather than the intended reduction. Second, the higher economic returns from intensified systems might incentivize producers to expand their pasture area, possibly promoting deforestation and offsetting the mitigation benefits of improved productions38. Finally, the increased beef production needed to satisfy growing demand may overshadow efforts to reduce livestock-based protein consumption as a means of cutting GHG emissions3,4,39,40,41,42,43.

However, these arguments often overlook the complex interactions between supply and demand and the pressing challenges facing beef production in the global food system. The dependence of supply on demand, as well as cost and price dynamics, must be considered. If pasture conditions and overall cattle ranching practices improve at scale, the projected demand for beef may be met with a significantly reduced land area and herd size. Conversely, if practices improve without a corresponding decrease in area and herd size, total production could exceed projected growth, raising questions about excessive supply. The hypothesis suggests that increased production will naturally lead to greater demand only if prices fall. For this to occur, either production costs or producers’ profits must decrease significantly. However, improved production methods do not substantially lower production costs, while livestock farming historically operates on low profit margins.

As intensification enhances herd productivity, enabling higher output per animal, results from this study show that it can also contribute to a gradual reduction in the total pasture area and the number of animals required over time for beef production. For instance, in the United States, beef production increased by 26% over four decades, despite a 21% reduction in the total cattle herd, demonstrating that higher output can coexist with fewer cattle44. South America should not replicate the U.S. model of intensive feedlots; it can continue to develop pasture-based systems that mitigate the environmental issues associated with highly intensive practices45.

Our findings also suggest that pasture-based intensification strategies identified in this study (Table 1)—centered on practices already available to producers, such as improved pastures, rotational grazing, and targeted feed supplementation—can deliver substantial reductions in CH4 emissions while improving productivity. These practices are widely adopted in the more intensive systems evaluated in this study and have been identified as primary mitigation strategies for reducing CH4 emissions from livestock, as they enhance forage digestibility and nutrient intake, improve feed efficiency, and shift rumen fermentation away from methanogenesis toward more energy-efficient pathways. This reduces CH4 emissions per unit of beef and shortens the time animals spend emitting CH4 during the production cycle29.Importantly, these practices are technically viable and compatible with the vast majority of pasture-based systems across South America, making them highly scalable and well-positioned for broader adoption. Together, they offer the most immediate and practical pathway to align the region’s livestock sector with global climate goals—particularly for CH4 mitigation targets outlined in initiatives such as the Global Methane Pledge46—and to support a broader transition toward low-emissions food systems5.

Importantly, the results indicate that sustained annual CH4 mitigation exceeding 1.5%—as projected in the improved systems scenario—surpass the ~ 0.35% threshold identified in the literature for halting additional CH4-driven warming under the GWP* metric. Given that CH4 accounts for more than 50% of total GHG emissions in many pasture-based systems, this implies that the warming impact of CH4 could be effectively neutralized by 2050. When combined with the land-sparing and potential carbon sequestration benefits of improved pasture management, these results point to a net-zero warming trajectory—not through complete elimination of GHG emissions, but through the strategic mitigation of CH4 and partial offsetting of remaining emissions via nature-based solutions.

As noted earlier, expanding agroforestry, incorporating novel forage systems, and adopting engineered solutions will be critical to maintaining long-term climate benefits. Advanced CH4-specific technologies such as 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP) and anti-methanogenic forages (e.g., Leucaena, red algae), have demonstrated CH4 mitigation potential exceeding 20% in controlled trials. However, these were not included in the modeled systems due to limited field-level adoption data across the region28,29. Integrating improved livestock systems with crops and forestry offers another promising approach to optimize land use, where soybean and other crops are rapidly replacing pastures47. These integrated systems create the potential for converting some pastureland to alternative uses while intensifying cattle ranching in the remaining areas. Additionally, they can offset a portion of cattle ranching emissions through carbon accumulation in soils and trees30,31. For instance, silvopastoral systems in Colombia, demonstrated a negative carbon footprint of -60 kg CO2e per kg liveweight gain. Similar benefits can arise from native species plantations, enhancing biodiversity, resilience, and potentially increasing income48. Roe et al.3 estimate, for example, that agroforestry systems—across both livestock and non-livestock sectors—could offer a mitigation potential of up to 107 Mt CO2e per year in South America between 2020 and 2050. Such approaches represent viable pathways to sustain lower emissions beyond 2050, complementing improved pasture management as soil carbon sequestration begins to plateau.

However, the transition to more efficient pasture-based systems often requires significant upfront investment, which may include costs related to pasture renovation, infrastructure, and herd management. The need for substantial financial capital can hinder the adoption of intensive cattle ranching, particularly for producers with limited capital or who lack access to financing. Furthermore, extensive ranching tends to attract low-risk and low-return investors and speculators. Higher investment levels may also be less attractive due to fluctuating commodity prices.

While this study focuses on the biophysical mitigation potential of improved pasture-based systems, further research is needed to assess the financial requirements, risk-sharing mechanisms, and enabling conditions for widespread adoption. Climate finance instruments—such as carbon markets—may play a key role in supporting these transitions, particularly when designed to be inclusive of smallholder producers.

In conclusion, pasture-based intensification is not only a mitigation opportunity, but a strategic entry point for aligning the livestock sector with net-zero warming trajectories. With the right support, it can deliver meaningful emissions reductions, strengthen food security, and enhance the sustainability of beef production in South America.

Methods

Characterization of beef cattle production systems

This research involved a comprehensive and collaborative effort to identify and characterize major beef production systems across five target countries in South America: Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia, and Paraguay. These systems were categorized based on farm management practices and levels of intensification, covering approximately 30 production systems ranging from extensive to intensive operations.

To achieve this, the study was conducted in partnership with renowned agricultural research institutions, including INTA in Argentina, INIA in Uruguay, EMBRAPA in Brazil, and the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT in Colombia, along with support from the Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT-affiliated consultants in Paraguay, among others. Local experts, including researchers, extension agents, and practitioners with in-depth knowledge of regional systems, were also integral to this process. These collaborations ensured the inclusion of region-specific insights and the accuracy of the characterization.

Experts identified three to eight common full-cycle production systems in each country, ranging from extensive to intensive operations, focusing on cow-calf, rearing and finishing operations15,34. Each system was assessed for its management practices, herd structure, pasture use, and other defining characteristics. This systematic approach ensured that the diversity of production systems, ranging from extensive grazing systems to highly intensive feedlots for finishing, was accurately captured.

To characterize representative production systems, data collection was conducted through structured workshops, guided interviews, and expert surveys in five countries: Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia, and Paraguay. Five experts were interviewed in each country—including senior researchers from national agricultural research institutions (e.g., Embrapa in Brazil, INTA in Argentina, INIA in Uruguay), livestock consultants, and representatives from government agencies and the beef industry. Each consultation process was complemented by one virtual multi-stakeholder workshop per country to validate system typologies and refine technical inputs. All expert interviews, questionnaires, and workshops followed institutional guidelines by the research ethics committee of the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT.

A standardized questionnaire was applied across all sessions, organized around four thematic blocks: (i) System characteristics, including production typology, geographic and agroecological context, land tenure, and herd size; (ii) Livestock management, covering herd composition, breed types, reproductive strategies (e.g., calving intervals, weaning age), feeding practices by production phase, and dry matter intake; (iii) Pasture and resource use, including pasture type (natural, improved, mixed), quality, rotational grazing practices, fertilizer and lime application, diesel use, and mechanization levels; and (iv) Productivity and performance, including average daily weight gain, weaning and calving rates, final animal weights, and carcass yield.

This process generated detailed, system-specific data on animal management, forage supply, and input intensity. This harmonized dataset formed the empirical foundation for the LCA, supporting the estimation of emission factors for CH4 (enteric fermentation, manure), nitrous oxide (N2O; fertilizer application, manure), and CO2 (feed production, energy use, mechanization).

To facilitate cross-country comparison while preserving scientific neutrality, production systems were harmonized across countries into typologies based on shared functional characteristics—such as pasture type, input intensity, feeding strategies, and productivity levels—rather than being attributed to specific countries. This design choice reflects the intent to assess mitigation potential at the system level, independent of national boundaries. While expert consultations were conducted in each country, the resulting typologies were synthesized into regional system categories (extensive, semi-intensive, and intensive) to support technical comparability and enable cross-cutting insights. This approach avoids the disclosure of country-specific production models and ensures that the findings remain policy-relevant, technically grounded, and free from unintended commercial interpretations.

GHG emissions metrics

All GHG emissions in this study were calculated using the GWP100 metric, following the IPCC 2006 and 2019 Guidelines for National GHG Inventories. The life cycle assessment (LCA) approach, as developed and described by González-Quintero et al.24, was applied consistently across cow-calf, rearing, and finishing phases in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Colombia. The same IPCC Tier 2 equations and input structure were used across all systems to ensure methodological consistency. Emissions were expressed in CO2e, allowing for comparability across CH4, N2O, and CO2. All LCA results—including emissions per hectare, per animal, and per ton of carcass weight (t/cw)—are based exclusively on GWP100 using values for CH4, CO2 and N2O of 28, 1 and 265, respectively49. The functional unit applied in this study was one ton (1,000 kg) of carcass. The LCA was done by the attributional method, which aims to quantify GHG emissions impact of a system’s main co-products in a status quo situation. Modelling of impact categories was carried out in Microsoft Excel. Calculations of GHG emissions were estimated using the 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines50. Table 4 summarizes the equations and emission factors (EF) used to estimate the primary emissions of CH4, N2O, and CO2.

To complement this emissions accounting framework, the GWP* (GWP star) metric was also applied in a separate analytical exercise to estimate CO2-warming-equivalent (CO2-we) values associated with CH4 mitigation. GWP* is a flow-based metric designed to capture the temperature impact of short-lived climate pollutants by accounting for changes in emission rates over time. Using the methodology described by Lynch et al.32 and Costa Jr. et al.22, CO2-e outcomes were modeled under scenarios of sustained annual CH4 mitigation exceeding 1.5% through 2050. These calculations were used only to conceptually illustrate the potential for reducing methane-driven warming and are clearly distinguished from the core GWP100-based LCA results.

System boundary definition

The system boundary was defined on a “cradle to farm-gate” perspective for cow-calf, rearing and finishing farms. The direct or primary emissions are those generated within the farm system (on-farm), and the secondary off-farm emissions are those upstream emissions related to the production and transport of imported resources such as feed, fertilizer, and soil amendments (Fig. 2). The system boundary for estimating the GHG emission from beef production includes:

-

Enteric fermentation CH4 emissions

-

CH4 emissions from manure management

-

Direct and indirect N2O emissions from manure management and nitrogen fertilizer

-

CO2 emissions from application of fertilizers (urea) and lime

-

Emissions from feed production i.e., direct and indirect N2O emission and CO2 emissions from application of fertilizer, lime and crop residues.

-

CO2 emissions from machinery used on farm and for feed production, and energy use.

-

CO2 and N2O emissions from fertilizer production are needed for feed production and pasture fertilization.

Emissions scenario development for 2050

To explore the long-term mitigation potential of pasture-based intensification, four illustrative GHG emissions scenarios were developed for the year 2050: a BAU scenario and three Improved System scenarios based on differing performance benchmarks.

For the BAU scenario, projections from FAOSTAT were used for the year 2050, which estimate CH4 and N2O emissions from beef production in South America under current trajectories. These projections account for emissions from enteric fermentation, manure management, manure left on pasture, and manure applied to soils, based on IPCC Tier 1 default methodologies and FAO activity data. The BAU scenario reflects a continuation of prevailing practices without widespread adoption of mitigation strategies.

To estimate total beef production volume in 2050, the analysis drew on projections from the FAO Agricultural Outlook 2018–202751, which anticipates approximately 40% growth in beef demand in South America between 2020 and 2050. These projections served as the production baseline for all scenarios.

For the Improved System scenarios, emissions were estimated by applying the emissions intensities derived from this study across the projected 2050 beef production volume. Specifically, three scenarios were constructed based on aggregation of production systems falling within the 40th, 20th, and 10th percentiles of the emissions intensity distribution observed in the dataset. These percentiles reflect moderate, ambitious, and high-performance improvements, respectively. Each scenario assumes the region shifts toward broader adoption of existing, real-world systems already operating at those efficiency levels.

In the Enhanced Mitigation scenario, soil carbon sequestration was explicitly included in addition to improved pasture management, drawing on regionally specific estimates from Roe et al.3, which suggest a cost-effective sequestration potential of 139 MtCO2e per year from restored grasslands in South America between 2020 and 2050.

Finally, to contextualize the potential warming impact of CH4 mitigation, the GWP* metric was applied conceptually. Studies by Lynch et al.32 and Costa Jr. et al.22 indicate that a sustained annual reduction of ~ 0.35% in CH4 emissions is sufficient to halt additional methane-induced warming.

Land use intensity for 2020 was estimated by dividing beef production values by the pasture area in South America (approximately 300 million hectares)12,13. For the 2030 and 2050 BAU scenarios, land use intensity was estimated proportionally, based on the projected changes in emissions intensity relative to 2020 and corresponding beef production forecasts for 2030 and 2050.8

Use of experimental animals and human participants

No experiments involving humans or animals were conducted in this study. All methods were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards and guidelines of the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT Institutional Review Board (IRB). The research consisted of expert interviews with livestock researchers, focused on professional perspectives on livestock systems, and did not involve the collection of personal or sensitive data. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. Researchers interested in accessing the data should contact the corresponding author. Data may be provided in formats suitable for analysis, along with relevant metadata to facilitate interpretation. To maintain the integrity of the research and protect any sensitive information, requesters may be asked to provide a clear purpose for data use and sign a data-sharing agreement, if necessary.

References

IPCC. Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2022).

IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, Switzerland, 2023).

Roe, S. et al. Land-based measures to mitigate climate change: Potential and feasibility by country. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 6025–6058 (2021).

Clark, M. A. et al. Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the 1.5° and 2°C climate change targets. Science 370, 705–708 (2020).

Costa, C. Jr. et al. Roadmap for achieving net-zero emissions in global food systems by 2050. Sci. Rep. 12, 15064 (2022).

Tubiello, F. N. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from food systems: building the evidence base. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 065007 (2021).

Crippa, M. et al. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat. Food. 2, 198–209 (2021).

FAO. The future of food and agriculture—Alternative pathways to 2050. (2018).

OECD-FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2022–2031. (OECD, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1787/f1b0b29c-en.

Gerber, P. J. et al. Tackling Climate Change through Livestock: A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2013).

Strassburg, B. B. N. et al. When enough should be enough: Improving the use of current agricultural lands could meet production demands and spare natural habitats in Brazil. Glob. Environ. Chang. 28, 84–97 (2014).

FAO-Stat. Food and Agriculture Data. (2024).

Zalles, V. et al. Rapid expansion of human impact on natural land in South America since 1985. Sci. Adv. 7(14), eabg1620 (2021).

Fuglie, K., Peters, M. & Burkart, S. The extent and economic significance of cultivated forage crops in developing countries. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, 712136 (2021).

Cardoso, A. S. et al. Impact of the intensification of beef production in Brazil on greenhouse gas emissions and land use. Agric. Syst. 143, 86–96 (2016).

Barbero, R. P. et al. Production potential of beef cattle in tropical pastures: a review. Ciênc. anim. bras. 22, 69609 (2021).

Alexandratos, N. & Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture towards 2030/2050: the 2012 revision. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2012).

Garcia, E., Ramos Filho, F. S. V., Mallmann, G. M. & Fonseca, F. Costs, benefits and challenges of sustainable livestock intensification in a major deforestation frontier in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability 9, 158 (2017).

Fisher, M. J. et al. Another dimension to grazing systems: Soil carbon. Tropical Grasslands 41, 65–83 (2007).

Maia, S. M. F., Ogle, S. M., Cerri, C. E. P. & Cerri, C. C. Effect of grassland management on soil carbon sequestration in Rondônia and Mato Grosso states. Brazil. Geoderma 149, 84–91 (2009).

Carvalho, J. L. N. et al. Impact of pasture, agriculture and crop-livestock systems on soil C stocks in Brazil. Soil Tillage Res. 110, 175–186 (2010).

Costa Jr, C., Wironen, M., Racette, K. & Wollenberg, E. Global Warming Potential* (GWP*): Understanding the implications for mitigating methane emissions in agriculture. CCAFS Info Note. Wageningen, The Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). (2021).

Kozicka, M. et al. Feeding climate and biodiversity goals with novel plant-based meat and milk alternatives. Nat Commun 14, 5316 (2023).

González-Quintero, R. et al. Environmental impact of primary beef production chain in Colombia: Carbon footprint, non-renewable energy and land use using life cycle assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 773, 145573 (2021).

Becoña, G., Astigarraga, L. & Picasso, V. D. Greenhouse gas emissions of beef cow-calf grazing systems in Uruguay. SAR 3, 89 (2014).

Cohn, A. S. et al. Cattle ranching intensification in Brazil can reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by sparing land from deforestation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 7236–7241 (2014).

Herrero, M. et al. Greenhouse gas mitigation potentials in the livestock sector. Nature Clim Change 6, 452–461 (2016).

Hegarty, R. S. et al. An evaluation of evidence for efficacy and applicability of methane inhibiting feed additives for livestock. A report coordinated by Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) and the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC) initiative of the Global Research Alliance (GRA). (2021).

Arndt, C. et al. 5 Full adoption of the most effective strategies to mitigate methane emissions by ruminants can help meet the 1.5 °C target by 2030 but not 2050. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2111294119 (2022).

Parra, A. S., Ramirez, D. Y. G. & Martínez, E. A. Silvopastoral systems ecological strategy for decreases C footprint in livestock systems of piedmont (Meta). Colombia. Braz. arch. biol. technol. 66, e23220340 (2022).

de Souza, J. P. et al. Carbon dioxide emissions in agricultural systems in the Brazilian Savanna. J. Agric. Sci. 11, 242 (2019).

Lynch, J., Cain, M., Pierrehumbert, R. & Allen, M. Demonstrating GWP*: A means of reporting warming-equivalent emissions that captures the contrasting impacts of short- and long-lived climate pollutants. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 044023 (2020).

Batista, E. et al. Large-scale pasture restoration may not be the best option to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in Brazil. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 125009 (2019).

Micol, L. & Costa Jr, C. Why and how to scale up low-emissions beef in Brazil, and the role of carbon markets: Insights for beef production in Latin America. Cali (Colombia): CGIAR Initiative on Livestock and Climate 50 (2023).

Tibbo, M., Iniguez, L. B. & Rischkowsky, B. Livestock and climate change: local breeds, adaptation and ecosystem resilience. in Review of Agriculture in the Dry Areas 37–39 (ICARDA, 2008).

Grandin, T. Evaluation of the welfare of cattle housed in outdoor feedlot pens. Veterinary Animal Sci. 1–2, 23–28 (2016).

Bonilla-Cedrez, C. et al. Priority areas for investment in more sustainable and climate-resilient livestock systems. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1279–1286 (2023).

Barona, E., Ramankutty, N., Hyman, G. & Coomes, O. T. The role of pasture and soybean in deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 024002 (2010).

Roe, S. et al. Contribution of the land sector to a 1.5 °C world. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 817–828 (2019).

Latawiec, A. E., Strassburg, B. B. N., Valentim, J. F., Ramos, F. & Alves-Pinto, H. N. Intensification of cattle ranching production systems: socioeconomic and environmental synergies and risks in Brazil. Animal 8, 1255–1263 (2014).

Tilman, D. & Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 515, 518–522 (2014).

Cusack, D. F. et al. Reducing climate impacts of beef production: A synthesis of life cycle assessments across management systems and global regions. Glob Chang Biol 27, 1721–1736 (2021).

Springmann, M. et al. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet. Health 2, e451–e461 (2018).

USDA. Overview of the United States Cattle Industry. https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/8s45q879d/9z903258h/6969z330v/USCatSup-06-24-2016.pdf (2016).

Merry, F. & Soares-Filho, B. Will intensification of beef production deliver conservation outcomes in the Brazilian Amazon?. Elem. Sci. Anthropocene 5, 24 (2017).

Global Methane Pledge. Global Methane Pledge. (2023).

Sekaran, U., Lai, L., Ussiri, D. A. N., Kumar, S. & Clay, S. Role of integrated crop-livestock systems in improving agriculture production and addressing food security—A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 5, 100190 (2021).

Soares, D. S., Calmon, M. & Matsumoto, M. Reflorestamento com espécies nativas: estudo de casos, viabilidade econômica e benefícios ambientais. Força-Tarefa Silvicultura de Espécies Nativas da Coalizão Brasil Clima, Florestas e Agricultura. (2021).

IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (Eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 Pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/ (2014).

IPCC. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. (2019).

OECD-FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2018–2027. (OECD, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1787/agr_outlook-2018-en.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of the One CGIAR Research Programs on Animal and Aquatic Food System and Climate Action, the One CGIAR Hub for Sustainable Finance – Impact SF, and with financial support from the Bezos Earth Fund project “Using genetic diversity to capture carbon through deep root systems in tropical soils,” and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Bezos Earth Fund project “Anti-methanogenic feedstock for livestock systems in Global South.” The authors acknowledge the Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT Science Editing Unit for copyediting of our manuscript. The views expressed in this document cannot be taken to reflect the official opinions of these organizations.

Funding

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Bezos Earth Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C.J. designed the research, wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. C.C.J., L.O.T., G.B., L.M., E.B.P., A.R.L., M.I., L.G., C.F., P.M.R., M.P.T., L.F.D.B. collected data. R.G.Q. and L.M. analyzed data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Costa, C., Tedeschi, L.O., Gonzalez-Quintero, R. et al. South america’s pasture intensification can increase beef production, reduce emissions by 30% and mitigate warming from methane by 2050. Sci Rep 15, 35734 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20394-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20394-y