Abstract

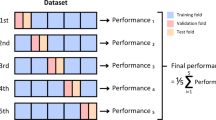

Malaria remains a critical global health challenge, requiring accurate and efficient diagnostic tools, particularly in developing countries with limited medical expertise. Detecting malaria parasites from red blood cell (RBC) blood smear images is challenging due to subtle color variations, indistinct demarcation lines, and diverse parasite morphologies. While numerous deep learning models address these issues, their high parameter counts often hinder practical deployment. We propose DANet, a lightweight Dilated Attention Network with approximately 2.3 million parameters, designed for robust malaria parasite detection. DANet employs a novel dilated attention mechanism to capture contextual information and highlight critical features in low-contrast smears, achieving an F1-score of 97.86%, accuracy of 97.95%, and an area under the curve-precision recall (AUC-PR) of 0.98 on the NIH Malaria Dataset, comprising 27,558 images (19,290 training, 2756 validation, 5512 test) from 150 infected and 50 healthy individuals. Compared to state-of-the-art models, including convolutional neural network-transformer hybrids, DANet offers superior efficiency, enabling deployment on edge devices like the Raspberry Pi 4. Its robustness is validated through 5-fold cross-validation and Grad-CAM visualizations, demonstrating enhanced interpretability. DANet provides a practical, high-performance solution for automated malaria diagnosis in resource-constrained settings. The source code of the proposed method is available at: https://github.com/asfakali/DANet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Plasmodium species include malaria parasites that are tiny and single-celled animals. They transmit malaria, which is a deadly mosquito-borne disease. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), malaria sickness increased by around 5 million per year in 2022, affecting 249 million people in total1. According to recent WHO estimates, malaria cases are expected to treble as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak. This motivates government and private organizations to investment more in malaria detection research.

Light microscopy is the standard method of detecting malaria parasites, but sometimes its accuracy is doubtful2,3. It has a sensitivity of 99%, specificity of only 57%4, and requires competent medical staff. Additionally, it includes time-consuming, repetitive, and error-prone processes. More advanced techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and rapid diagnostic assays, are evolving. Earlier, machine learning (ML) has made medical diagnosis easier to carry out, decreasing the need for experts and costly medical equipment. However, ML-based malaria detection and classification algorithms used manually generated feature extraction to discriminate medical images, which had limitations in terms of data dependency, accuracy and was not tested against a proper benchmark5.

In recent years, deep learning (DL) based methods have been adopted for medical image analysis using classification, recognition, localization, and segmentation tasks6,7. As a result of this development, the use of CNN models to detect malaria parasites is becoming more prevalent. CNN models can be more easily integrated into existing models because of their simplicity and ease of usage. CNN models excel at learning complex features and patterns from raw data. In the case of malarial parasite detection, these models can automatically learn discriminative features from microscopic images, which may not be easily identifiable or extractable using handcrafted features using traditional ML-based methods, however, the existing DL-based methods lack in terms of processing speed.

Several ML approaches for Red Blood Cell (RBC) classification have been developed, including support vector machine (SVM), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and linear discriminant analysis (LDA)8. Furthermore, sophisticated DL techniques, such as Attention-Dense Circular Net (ADCN)9, deep belief-based classification networks10, Mosquito-Net, LeNet11, AlexNet12, and GoogleNet13, have been developed to identify malaria-infected blood cells using the Malaria Cell Images Dataset from the NIH. Despite the effectiveness of DL-based categorization for malaria parasites, there are still significant obstacles that are mentioned below.

-

Challenges The availability of training data is limited, parasite similarities across classes, and poor smear quality, affect the effectiveness of detection algorithms. Malaria parasite detection in thin blood smears is difficult due to low contrast and blurry borders. Minor variations in these characteristics can impact the classification of malaria parasites. Furthermore, intra-class similarity and variance are important factors influencing the accuracy of malaria parasite detection.

-

Motivation and Contributions Pre-trained CNN models can be useful in such situations; however, when training data is limited, they may overfit and produce biased results. Furthermore, the huge number of parameters in these models makes them computationally expensive for inference tasks and causes slower processing times. To address these issues, this research presents a lightweight CNN model for distinguishing malaria-infected from uninfected blood smears. In addition, a Dilated Attention block is proposed to improve blood cell classification, thereby increasing the efficiency in malaria parasite identification. The proposed model achieves 97.06% classification accuracy and 96.98% F1-score using only 20% training data samples. The proposed DANet is designed to have fewer parameters while maintaining high accuracy and can be run on mobile devices such as Raspberry Pi 4b.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: section 2 explores past research on the topic to provide context for the proposed methodology. Section 3 expands on the proposed methodology, describing the methods adopted to solve the issues found in prior studies. Section 4 describes the experimental setup, dataset, pre-processing, and evaluation metrics. Section 5 describes the results achieved through experimentation and discusses the performance of the proposed model. Section 6 wraps up the paper by reviewing the important findings and suggesting some potential future research scopes.

Related work

Extensive research has been conducted for malaria parasite identification and classification tasks using computer-aided diagnostic systems, with two basic methodologies: the traditional ML techniques and the DL-based approaches, which is the emphasis of this section.

The traditional method of malaria parasite detection normally consists of several important stages: image preprocessing, blood component segmentation, component classification, and parasite candidate generation. Image preprocessing techniques are used to improve the quality of blood smear images, increasing the precision of future processing steps such as cell segmentation, feature extraction, and classification with typical machine learning approaches. Devi et al.14 developed a hybrid classifier that combined SVM, KNN, Naive Bayes, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), achieving a 96.3% accuracy. Their model extracted cell pixels from the background using thresholding and watershed approaches and then trained on morphologically segmented images. Gezahegn et al.15 suggested a method employing handcrafted Scale Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) features for malaria infection classification, utilizing an SVM classifier. However, due to the limitations of handcrafted features for training, their approach achieved just 78.89% accuracy. May et al.16 used a median filter to minimize impulse noise and a Wiener filter to reduce additive noise in the preprocessing stages. Malihi et al.17 used the Otsu thresholding approach to preprocess blood samples before classifying them with the KNN Classifier. Mandal et al.18 developed a logistic regression-based classification strategy for parasite identification, which achieved an accuracy of 88.77%. Anggraini et al.19 used a Bayesian classifier to categorize malaria parasites into various stages, such as ring shapes and other artifacts, and achieved a 93.3% accuracy. Kshipra Charpe et al.20 provided a method for finding 15 RBC images that used the watershed transform technique for segmentation and then parasite classification. Somasekar et al.21 used SVM based on morphological procedures to categorize infected cells from 76 images. For detecting malaria-infected RBC images, these strategies primarily used classic computer vision and ML techniques, such as thresholding algorithms and feature extraction. While some traditional methods produced satisfactory results, they frequently required substantial prior information, and complex preparation steps, and were tested on tiny datasets, limiting the reliability of their findings.

Recent advances in DL have transformed computer vision and disease identification, with CNN-based models leading the way. Popular DL architectures such as VGG, ResNet, AlexNet, InceptionNet, and EfficientNet have exhibited outstanding performance in a variety of computer vision applications, including medical image classification, after being pre-trained on large-scale datasets such as ImageNet. Bibin et al.10 developed a Deep Belief Network for malaria-infected image categorization, which uses Restricted Boltzmann Machines (RBM) to process image pixels. Vijayalakshmi et al.22 introduced VGG-SVM, a hybrid CNN and ML model in which a pre-trained VGG network extracts features and then classifies them using SVM. Notably, VGG-SVM attained an accuracy of 89.21% for VGG16 and 93.13% for VGG19. Pattanaik et al.23 developed an auto-encoder-based model, specifically the Stacked Sparse Auto Encoder (SSAE), to get improved features, with subsequent classification using Functional Link ANN (FLANN), obtaining 89.10% accuracy with only 1182 images. They also developed Multi-Magnification ResNet (MM-ResNet), which addressed the vanishing gradient problem by concatenating input and output layers and produced encouraging results. Furthermore, Kumar et al.24 introduced Mosquito-Net, an attention-based classification model designed for lightweight malaria detection that can be deployed on mobile devices. While existing models perform well, their computational complexity limits their applicability to mobile devices and several models lack validation against accepted benchmarks. To address these limitations, we present a lightweight attention-based CNN model for malaria detection and evaluate it on the publicly available in NIH database. A paper by Khan et al. (2023)25 specifically explores deep learning applications for COVID-19 detection, evaluating models like ResNet, VGG, and EfficientNet on radiographic and clinical datasets. Their methodology revolves around transfer learning and ensemble strategies, achieving high diagnostic accuracy but with significant computational costs.

Despite significant advances in malaria parasite detection, several important research gaps remain unaddressed in the literature. Many high-performing deep learning models, such as VGG, ResNet, and EfficientNet, involve millions of parameters and demand substantial computational resources, limiting their feasibility for real-time diagnosis in low-resource or point-of-care environments. Furthermore, most existing approaches adapt generic computer vision architectures without explicitly accounting for the unique morphological characteristics of malaria parasites, potentially overlooking subtle yet crucial features necessary for accurate detection. The robustness of current models is also hindered by their sensitivity to variations in blood smear quality, low contrast, blurry cell boundaries, and high intra-class similarity, all of which present persistent classification challenges. Additionally, various reported methods have been evaluated on small or homogeneous datasets, raising concerns about their generalizability to broader clinical scenarios. To address these limitations, we propose DANet, a lightweight attention-based CNN that integrates a novel Dilated Attention Block (DAB) to effectively capture multi-scale contextual features while preserving computational efficiency. DANet achieves a high classification accuracy of 97.95% with only 2.3 million parameters, offering a domain-specific, resource-efficient solution suitable for real-time and low-cost deployment in healthcare facilities.

Methodology

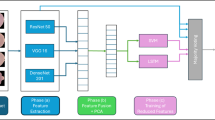

This section explains the basic components, provides an overview of the architecture, and discusses the theoretical framework behind the proposed Dilated Attention Network (DANet). The architecture of the proposed DANet is shown in Fig. 2.

Dilated attention block

Classifying malaria parasite-infected and uninfected RBC blood smear images provides unique problems. This is mostly owing to the blood smear’s similar color tones, the absence of defined boundaries, and the varying morphologies of diseased tissues as shown in Fig. 3. To address these challenges, attention mechanisms are crucial for increasing classification accuracy. In the proposed model, we introduce a Dilated Attention Block (DAB) to capture and highlight important characteristics in blood smear images.

We use a multi-dilation technique in our architecture to improve the receptive field without introducing substantial parameters while keeping the model high efficiency. Initially, a conventional convolutional layer with a \(1 \times 1\) kernel size is used. Next, we apply three independent \(3 \times 3\) convolutional layers with various dilation factors (DF) - precisely, DF=1, 2, and 3. This varied dilation method provides a wider perspective of the input while effectively gathering contextual information. The outputs of these convolutional layers are then combined to create a preliminary fused feature map, \(f_{preConcat} \in \mathbb {R}^{W \times H \times 3C}\). This fusion process helps to learn aspects associated with unclear boundaries and blood tissue variations, by combining information from a larger region surrounding each pixel and expanding the receptive field of the input features, the model acquires an extensive understanding of the image, making it easier to distinguish small details.

In Equation 1, \(f_c\) denotes the convoluted feature map derived from the \(1 \times 1\) kernel size convolutional layer. The notation \(Conv_k\) refers to a convolutional operation with a dilation factor of k, where k represents various DFs used in the model design.

The network then performs two distinct pooling operations: average pooling and max pooling. The features derived from these procedures are concatenated and denoted as \(f_{\text {poolConcat}} \in \mathbb {R}^{W \times H \times 6C}\). Max pooling identifies the most important properties within a region by extracting the largest value, whereas average pooling computes the average value to capture the data’s general trends and characteristics. This combination technique efficiently captures both detailed features and overarching patterns, improving the network’s generalizability and robustness.

Pooling can be done in two ways: first, by keeping the same dimensions as the input as shown in Fig. 1a, and second, by halving the size of the feature dimension relative to the input dimension as shown in Fig. 1b. Both methods of pooling have been tested in this paper to determine their effectiveness. The pooled features are enhanced with \(3 \times 3\) convolution layer, followed by layer normalization, a \(1 \times 1\) convolution layer, and a sigmoid operation. This procedure aims to create an attention map that can capture structural information of the affected blood smear.

Following this, we conduct an element-wise multiplication between the attention feature map and the input feature.

However, this step is only feasible if the pooling procedure produces the same feature dimension as the input. When the feature dimension is halved, there is a dimension mismatch with the input. To address this, we use MaxPooling and a \(1 \times 1\) convolution layer on input features. These halved features are then multiplied element by element using the attention feature map.

where \(f_{DAB}^h\) and \(f_{DAB}^s\) denote the same and halved version of dilated attention block outputs. The architecture of \(DAB-H\), \(DAB-S\) are shown in Fig. 1a and b, respectively.

Overall architecture

Figure 2 shows the complete architecture of the proposed model. This network has a convolution layer, a few max pooling layers, nine DABs, two fully connected layers, and an output layer with a LogSoftMax activation function. To accommodate various attention methods, we create two separate model versions, using \(DAB-H\) and \(DAB-S\), which are described in Fig. 2a and b, respectively.

DANet-H The model handles images of dimension \(224 \times 224 \times 3\), starting with a convolution layer with 8 filters of size \(3 \times 3\). This stage is followed by a max pooling layer with a pool size of \(2 \times 2\) and a stride of 2, lowering the spatial dimensions of the feature maps. Next, the model has nine \(DAB-H\) blocks. Following the initial attention block, the number of filters is doubled every two attention blocks, gradually increasing the model’s ability to capture increasingly complicated characteristics. To reduce the feature representation, an average pooling operation with a filter size of \(7 \times 7\) is used. This reduction stage is followed by two fully connected layers of 128 and 64 neurons, respectively, culminating in an output layer for classification.

DANet-S: In this configuration, the model uses nine \(DAB-S\) blocks and MaxPooling layers. The model starts with a convolution layer of 8 filters, each \(3 \times 3\) in size, to extract initial features from the input image. Next, a max pooling layer with a pool size of \(2 \times 2\) and a stride of 2 is used to reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature maps for better computational efficiency. The architecture includes \(DAB-S\) blocks, followed by max pooling to improve and emphasize key features while reducing spatial dimensions. Following the deployment of the initial attention block, the model adopts a strategy of stacking two \(DAB-S\) followed by max pooling. The number of filters is doubled for each consecutive pair of attention blocks. This systematic increase in filter count aims to gradually improve the network’s ability to detect and represent more complex features inherent in the data. The design of the fully connected layer remains consistent with the prior model version’s final classification result.

Experiments

Dataset

The suggested model is trained and evaluated using the Malaria Cell Images DatasetFootnote 1 from the National Institute of Health (NIH). RBC micrograph images were taken from the Chittagong Medical College Hospital. This dataset contains images of blood smear slides from 150 malaria-infected patients and 50 healthy persons, which were precisely labeled by professional physicians from the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit in Bangkok. The dataset is freely available on a variety of platforms, including the National Library of Medicine (NLM), Kaggle, and the NIH database. It is divided into two categories: parasitized and uninfected, as shown in the Fig. 3. With a total of 27,558 data points, half of which are malaria blood smear images and the rest representing uninfected samples. The dataset has been divided into three groups as shown in the Table 1: 70% for training, 10% for validation, and 20% for testing, though data-split variations may apply to the compared models as reported in their original studies.

Data pre-processing and augmentation

During the pre-processing stage, two fundamental processes are performed. The image is first downsized to \(224 \times 224\) dimensions, then normalized from the original range of [0, 255] to [0, 1]. This normalizing step is crucial for avoiding gradient separation and accelerating convergence during model training. Three augmentation strategies are used to reduce the risk of overfitting: random rotation, horizontal flip, and vertical flip. These strategies help to improve the model’s generalization capabilities. The random rotation has a maximum rotation angle of 15\(^\circ\), whereas horizontal flip and vertical flip are only conducted on 20% of the training set’s data at random. Figure 4 illustrates the data augmentation techniques applied to the NIH Malaria Dataset, showcasing original and augmented images of parasitized and uninfected cells. These augmentations simulate variations in smear orientation and appearance, improving DANet’s ability to handle low-contrast images and diverse parasite morphologies. This contributes to the model’s robustness, as demonstrated by its performance across reduced dataset samples.

Experimental setup

The proposed model has been trained on the Kaggle notebook environment, using a robust framework that includes a 16GB Nvidia Tesla T4 GPU and 12GB RAM. The programming language used is Python 3.7.6, and the model has been implemented using PyTorch version 1.9.0. All investigations and tests have been carried out with the Nvidia Tesla T4 GPU. The RMSprop optimizer is applied for model training, using a default learning rate of 0.001 and the Negative Log Likelihood (NLL) loss function. In addition, the model has been trained with the Binary Cross Entropy loss function for performance evaluation. The hyperparameters listed in Table 2 have been determined through empirical testing on the training set, with adjustments made to optimize accuracy and computational efficiency. The training process takes 75 epochs on the Malaria Cell Images Dataset from the NIH.

The hyperparameters used to develop the model are given in Table 2. We have not used any additional explicit regularization techniques because DANet has a very low parameter count, and it does not show any signs of overfitting during training.

Evaluation metrics

We use multiple performance metrics to evaluate the proposed model in this study, including accuracy, sensitivity (recall), specificity, precision, F1-score, and parameter count. The metrics are specified as follows:

Accuracy The accuracy metric calculates the percentage of successfully predicted cases to the total number of cases evaluated by the model. It provides a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s predicted performance.

Sensitivity (Recall) Sensitivity quantifies the proportion of true positive predictions relative to all actual positive cases. It gauges the model’s ability to correctly identify positive instances.

Specificity Specificity indicates the ratio of true negative predictions to all actual negative instances. It assesses the model’s capability to accurately identify negative cases.

Precision Precision represents the ratio of correctly predicted positive cases to all predicted positive samples. It reflects the model’s accuracy in identifying positive instances.

F1-score The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. It provides a balanced measure of a model’s performance by considering both precision and recall.

Here, TP denotes true positive outcomes, TN represents true negative results, FP signifies false positive outcomes, and FN denotes false negative results. These metrics collectively offer a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s effectiveness in malaria detection.

Sample images of uninfected and parasitized blood smears are shown with Grad-CAM-identified critical spots. These activation mappings identify certain pixels inside images that are important to the model’s decision-making in classification and attention performance of the proposed DANet-S + LogSoftMax.

Results and discussion

To evaluate and compare the classification performance of the proposed model, we have used several existing methods trained in the Malaria Cell Images Dataset from the NIH such as EfficientNetB026, ResNet15226, NASNetMobile26, InceptionV326, InceptionResNetV226, Yang F. et al.27, VGG1628, VGG1928, ResNet5024, DPN9232, DenseNet12131, DCNN(Falcon)-TL33, VGG16-SVM22, Mosquito-Net24, Alex-Net24, Xception-Net24, and DLRFNet34. This paper uses a variety of evaluation criteria, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1-score. Table 3 presents test results for existing and proposed models. The proposed models are compared to existing ones in three versions: DANet-S + Sigmoid, which incorporates a DAB-S block and Sigmoid activation in the final layer; DANet-S + LogSoftMax, which integrates a DAB-S block and LogSoftMax activation in the final layer; and DANet-H + LogSoftMax, which features a DAB-H block and LogSoftMax activation in the final layer. For models with Sigmoid activation in the final layer, Binary Cross Entropy loss is used for training, whereas NLL loss is used for those with LogSoftMax activation.

Figure 5 shows the accuracy and loss curves for the proposed models. Figure 5a demonstrates the performance of DANet-S + LogSoftMax, whereas Fig. 5b depicts DANet-H + LogSoftMax. These figures show that DANet-S + LogSoftMax has a faster convergence rate and stronger training stability than DANet-H + LogSoftMax. Furthermore, DANet-S + LogSoftMax has a smaller difference between training and validation accuracy and loss, indicating almost no overfitting than DANet-S + LogSoftMax.

Each version of the proposed model outperforms existing models on all evaluation measures. The DANet-S + LogSoftMax model has the maximum performance, with 97.95% accuracy, 97.76% precision, 98.07% sensitivity, 97.87% specificity, and 97.86% F1-score. In contrast, the DANet-S + Sigmoid model has the second-best performance, with 97.75% accuracy and 97.73% F1-score. In comparison, the DPN92 model produces the lowest results with 87.88% accuracy and 87.85% F1-score among the methods considered here for comparison. All versions perform similarly in terms of ROC. DANet-S + Sigmoid has an AUC of 97%, followed by DANet-H + LogSoftMax of 96% and DANet-S + LogSoftMax of 98%. Notably, the suggested model not only achieves higher accuracy and F1-score, but it also has the lowest parameter count, with just 2.3 million parameters. In comparison, DPN92, which has the lowest accuracy and F1-score, requires much more parameters (37.7 million). Figure 6 presents the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and Precision–Recall (PR) curves for three variants of the proposed model. The PR curves reveal that DANet-S+LogSoftMax maintains consistently high precision across a broad recall range, whereas alternative variants exhibit a sharper precision drop at higher recall levels, underscoring the robustness of the proposed approach in minimizing false negatives without sacrificing accuracy. In our comparison, we test the DANet-S + LogSoftMax model across increasing numbers of channels, measuring both accuracy and floating-point operations per second (Flops), as shown in Fig. 7. Our investigation shows that as the number of channels increases from 2 to 8, so do Flops and accuracy. However, increasing the number of channels to 16 reduces accuracy because it increases the model’s parameter count, thereby making the model more complex. This added complexity makes the model prone to overfitting. As a result, using 16 channels causes a small drop in accuracy, with about a 1% decrease in accuracy. In contrast, the use of 8 channels provides the optimal balance between the complexity and the performance, reducing overfitting and offering the best trade-off for accuracy.

Figure 8 illustrates a performance comparison of the proposed model on two different hardware platforms: a mobile device (Raspberry Pi 4b) and a high-performance device (Nvidia Tesla T4 GPU). The Raspberry Pi 4b is equipped with an ARM Cortex-A72 CPU and 2 GB of RAM, while the Nvidia Tesla T4 GPU boasts 16 GB of vRAM and 12 GB of system RAM. The results demonstrate that all three versions of the proposed model perform efficiently on both high-performing systems and mobile devices like the Raspberry Pi 4b. However, due to the significantly lower processing power of the Raspberry Pi 4b compared to the Nvidia Tesla T4 GPU, the processing speed on the Raspberry Pi is slower. Additionally, it is important to note that as the number of channels in the model increases, both the model parameters and FLOPs increase as shown in Fig. 7. This results in longer processing times on devices with limited computational capacity, such as the Raspberry Pi. Nevertheless, the proposed model remains lightweight, so the increase in processing time on high-performing devices like the Nvidia Tesla T4 GPU is minimal.

Table 4 shows how the model performs when trained on different proportions of a training dataset, from 20% to 100%. Despite the limited training data, the model is assessed using the same test set throughout. This experiment demonstrates the model’s capacity to generalize and remain resilient even with limited data. Interestingly, the model performs similarly across dataset sizes, indicating its robustness to the data shortage. While increasing data volume improves the model’s diagnostic capacity, it’s worth noting that limiting dataset size does not considerably reduce its diagnostic capability. The model outperforms larger datasets with only 40% of the training data, based on multiple classification measures.

We have used Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to better understand the input properties that impact the model in classification. The Fig. 9 shows both the input image and the associated Grad-CAM visualization. This visualization has a heatmap that highlights sections of the image, where the model concentrates its attention, showing the presence or absence of malaria infection and directing its decision-making process. In malaria-infected images, the model focuses attention on specific areas, but in uninfected images, it spreads attention across the cell. However, in both instances, the model does not focus on locations outside of the blood cell. This highlights the model’s attention capacity to identify significant characteristics within the cell and make correct classifications depending on the presence or absence of malaria infection.

To assess the performance of our binary classification model for distinguishing between Parasitized and Unparasitized cells, we have evaluated it on a test set comprising 2756 Parasitized and 2756 Unparasitized samples, totaling 5512 instances. The model’s performance is quantified using several metrics, including accuracy, precision, sensitivity (recall), specificity, and F1 score. Figure 10 presents the confusion matrix, which provides a detailed breakdown of the classification results.

Using t-SNE plots, we analyze how the proposed approach better aligns the target class distribution with that of the source. The graphic depicts the feature distribution across all samples under consideration. Notably, the clusters representing the two groups are very different, demonstrating the efficacy of our technique as shown in Fig. 11. However, some overlapping samples point to occasional misdiagnosis. Figure 11 also shows that the DANet-S + LogSoftMax configuration produces more unique t-SNE clusters than DANet-H + LogSoftMax, implying that the former arrangement performs better in terms of categorization.

Cross-validation results

To assess whether the DANet-S+LogSoftMax model is overfitting, a 5-fold cross-validation scheme is applied for testing. Table 5 presents the results, showing the model’s performance across multiple metrics. On the test set, the model achieves an overall accuracy of 97.95% and an F1 score of 97.87%. However, during cross-validation, the average accuracy decreases slightly to 97.25%, with an average F1 score of 97.20%. This slight reduction in performance reflects the more stringent evaluation provided through the cross-validation scheme, which better assesses the model’s robustness and generalization. Notably, to the best of our knowledge, none of the existing models in the literature have undergone cross-validation for testing, making a direct evaluation difficult.

The DANet-S+LogSoftMax model applies the same training protocol for both standard training and cross-validation scenarios, ensuring a consistent and rigorous evaluation process. Despite the minor decrease in the cross-validation performance, the model consistently outperforms existing models, demonstrating superior performance and robustness across different evaluation techniques. These results indicate that the model does not face the overfitting problem, as it performs well on both the test set and in cross-validation, confirming its suitability for real-world applications.

Statistical test

We have performed the McNemar’s test to evaluate the performance of the proposed three models trained on the Malaria Cell Images Dataset from the NIH. This non-parametric test examines the distribution of paired nominal data, as shown in Table 6. The p-value denotes the probability of similarity of the models. A p-value less than 0.05 (or 5%) indicates less similarity between the two models i.e., they are statically different. Table 6 shows a comparison of three versions of the proposed model, with p-values approaching zero for all combinations. Thus, we find that the outcomes of the models are statistically significant.

Additional experimentation

To evaluate the model’s performance on an additional dataset and assess whether it is biased towards the Malaria Cell Images Dataset, the Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)Footnote 2 image dataset is considered. This dataset contains 3256 peripheral blood smear images from 89 suspected ALL patients, whose blood samples were processed and stained by skilled lab workers. It includes two distinct classes: benign and malignant. The ALL group comprises Early Pre-B, Pre-B, and Pro-B ALL malignant lymphoblast subtypes, while hematogone represents the benign class. The sample distribution consists of 985 Early Pre-B, 963 Pre-B, 804 Pro-B ALL, and 504 benign cases.

The proposed model achieves an accuracy of 99.08% on the said dataset. In contrast, pre-trained models such as InceptionV345 and ResNet5046 perform lower, with accuracies of 96.93% and 97.85%, respectively. As shown in Table 7, the proposed model consistently outperforms state-of-the-art models, demonstrating superior performance and generalization across different datasets. This performance further highlights the proposed model’s effectiveness in distinguishing between malignant and benign cases in the ALL dataset. Figure 12 presents the ROC curve of the proposed model on the ALL dataset. The model demonstrates an impressive AUC of 0.99 for the benign class, 0.99 for the Early Pre-B class, 0.99 for the Pre-B class, and a perfect AUC of 1.00 for the Pro-B class.

Conclusion

This research presents DANet, a lightweight yet high-performing architecture for malaria parasite detection, which introduced the Dilated Attention Block (DAB) as a novel attention mechanism. Two variants, DANet-S and DANet-H, have been trained and evaluated on the NIH Malaria Cell Images Dataset, achieving competitive results, with DANet-S reaching 97.95% classification accuracy and 97.86% F1-score, while using only 2.3 million model parameters. The model demonstrated consistent performance across varying training samples, and its robustness has been statistically confirmed using the McNemar’s test. In addition to outperforming previous models, DANet ensures computational efficiency, making it suitable for deployment on edge devices such as the Raspberry Pi 4b for real-time diagnosis. However, our study is limited by its reliance on the NIH Malaria Cell Images Dataset due to the scarcity of open-access alternatives, which may affect generalization to different imaging conditions or populations. Furthermore, while no explicit regularization techniques were applied because the low parameter count prevented overfitting in our experiments, this choice may limit scalability to more complex datasets. Also, we acknowledge that McNemar’s test is applied only to DANet variants, as results of the external baseline models are unavailable. Future work will address these challenges by expanding validation to diverse datasets, integrating domain adaptation methods, and testing real-time deployment in clinical settings, thereby enhancing the model’s practical utility for accessible, rapid, and reliable malaria diagnosis in resource-limited environments.

Data availability

The Malaria Cell Images Dataset used and/or analysed during the current study is available at : https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/iarunava/cell-images-for-detecting-malaria

Notes

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/iarunava/cell-images-for-detecting-malaria

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mehradaria/leukemia

References

World Health Organization. Malaria, 2024. Accessed: date-of-access.

Salih, M. M., Abdulaali, A. R. & Falih, H. N. A proposed lightweight image encryption using chacha with hyperchaotic maps. Period Eng Nat Sci 8(4), 2138–2145 (2020).

Maximilian, H. C., Mengmeng, F. L. H. & Bekir, Ü. PCR amplification of repetitive DNA: A limitation to genome editing technologies and many other applications. Sci Rep 4(1), 5052 (2014).

Kenji, M. O. et al. A comparison of thick-film microscopy, rapid diagnostic test, and polymerase chain reaction for accurate diagnosis of plasmodium falciparum malaria. Malaria J 18, 1–8 (2019).

Vishnu, M., Yuhang, D., David, P. W. A comparison of feature selection methods for machine learning based automatic malarial cell recognition in wholeslide images. In 2016 IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI), pages 216–219 (2016).

Najm, Hayder, Hoomod, Haider K. & Hassan, Rehab. A proposed hybrid cryptography algorithm based on gost and salsa (20). Period Eng Nat Sci 8(3), 1829–1835 (2020).

Dinggang, S., Guorong, W. & Heung-Il, S. Deep learning in medical image analysis. Ann Rev Biomed Eng 19, 221–248 (2017).

Quan, Quan, Wang, Jianxin & Liu, Liangliang. An effective convolutional neural network for classifying red blood cells in malaria diseases. Interdiscip Sci: Comput Life Sci 12, 217–225 (2020).

Xian, Z., Oubo, G. Wenxin, H., Jingling, Y. Bo, M., Ryan Wen, L. Multi-scale residual network for image classification. In ICASSP 2020 - 2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2023–2027 (2020).

Bibin, Dhanya, Nair, Madhu S. & Punitha, P. Malaria parasite detection from peripheral blood smear images using deep belief networks. IEEE Access 5, 9099–9108 (2017).

Lecun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc IEEE 86(11), 2278–2324 (1998).

Krizhevsky, Alex, Sutskever, Ilya & Hinton, Geoffrey E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60(6), 84–90 (2017).

Christian, S., Wei, L., Yangqing, J., Pierre, S., Scott, Dragomir, A., Dumitru, E., Vincent, V., Andrew, R. Going deeper with convolutions. In 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 1–9 (2015).

Shuleenda, D. S., Shah, S., Anuradha, T. & Rabul, L. Malaria infected erythrocyte classification based on the histogram features using microscopic images of thin blood smear. Indian J Sci Technol 9, 1–10 (2016).

Girmay, G. Y., Hagos, G. M. Y., Adugna, E. E. & Niguse, G. T. G. Malaria detection and classification using machine learning algorithms. In Information and communication technology for development for Africa (eds Mekuria, F. et al.) 24–33 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018).

Zazilah, M., Aziz, M., Azreen, S. S., Rabi’ahtuladawiah, S. Automated quantification and classification of malaria parasites in thin blood smears. In 2013 IEEE International Conference on Signal and Image Processing Applications, pp. 369–373 (2013).

Leila, M., Karim, A.-A., Abdolamir, B. Malaria parasite detection in giemsa-stained blood cell images. 2013 8th Iranian Conference on Machine Vision and Image Processing (MVIP), 360–365 (2013).

Mandal, S., Kumar, A., Chatterjee, J., Manjunatha, M., Ray, A.K. Segmentation of blood smear images using normalized cuts for detection of malarial parasites. 2010 Annual IEEE India Conference (INDICON), 1–4 (2010).

Anggraini, D., Nugroho, A.S., Pratama, C., Rozi, I.E., Iskandar, A.A., Hartono, R.N. Automated status identification of microscopic images obtained from malaria thin blood smears using bayes decision: A study case in plasmodium falciparum. 2011 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems, 347–352 (2011).

Charpe, K., Bairagi, V.K., Desarda, S., Barshikar, S. A novel method for automatic detection of malaria parasite stage in microscopic blood image. International Journal of Computer Applications, 128(17), (2015).

Somasekar, J., Rama Mohan Reddy, A. & Sreenivasulu Reddy, L. An efficient algorithm for automatic malaria detection in microscopic blood images. In Global trends in information systems and software applications Springer (eds Venkata, P. et al.) 431–440 (Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, 2012).

Vijayalakshmi, A. & Rajesh Kanna, B. Deep learning approach to detect malaria from microscopic images. Multimedia Tools Appl. 79, 15297–15317 (2020).

Pattanaik, P. A., Mittal, Mohit, Khan, Mohammad Zubair & Panda, S. N. Malaria detection using deep residual networks with mobile microscopy. J King Saud Univ- Comput Inf Sci 34(5), 1700–1705 (2022).

Kumar, Aayush, Singh, Sanat B., Satapathy, Suresh Chandra & Rout, Minakhi. Mosquito-net: A deep learning based cadx system for malaria diagnosis along with model interpretation using gradcam and class activation maps. Expert Syst 39(7), e12695 (2022).

Khan, Asifullah et al. A survey of deep learning techniques for the analysis of covid-19 and their usability for detecting omicron. J Exp Theor Artif Intell 36(8), 1779–1821 (2023).

Montalbo, Francis Jesmar & Alon, Alvin. Empirical analysis of a fine-tuned deep convolutional model in classifying and detecting malaria parasites from blood smears. KSII Trans Internet Inf Syst 15, 147–165 (2021).

Yang, Feng et al. Deep learning for smartphone-based malaria parasite detection in thick blood smears. IEEE J Biomed Health Inf 24(5), 1427–1438 (2020).

Chakradeo, Kaustubh, Delves, Michael & Titarenko, Sofya. Malaria parasite detection using deep learning methods. Int J Comput Inf Eng 15(2), 175–182 (2021).

Muhammad, M. et al. Efficient deep learning-based approach for malaria detection using red blood cell smears. Sci Rep 14(1), 13249 (2024).

Qayyum, A.B., Islam, T., Haque, M.A. Malaria diagnosis with dilated convolutional neural network based image analysis. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Biomedical Engineering, Computer and Information Technology for Health (BECITHCON), 68–72 (2019).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L., Weinberger, K. Q.. Densely connected convolutional networks. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2261–2269 (2017).

Yunpeng, C., Jianan, L., Huaxin, X., Xiaojie, J., Shuicheng, Y., Jiashi, F. Dual path networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30 (2017).

Banerjee, T. et al. Deep convolutional neural network (falcon) and transfer learning-based approach to detect malarial parasite. Multimed Tools Appl 81(10), 13237–13251 (2022).

Murmu, A. & Kumar, P. Dlrfnet: Deep learning with random forest network for classification and detection of malaria parasite in blood smear. Multimed Tools Appl 83(23), 63593–63615 (2024).

Dev, A., Fouda, M. M., Kerby, L. & Fadlullah, Z. M. Advancing malaria identification from microscopic blood smears using hybrid deep learning frameworks. IEEE Access 12, 71705–71715 (2024).

Aanjan, K.S., Kumar, M.M., Kumar, P.S., Dhanaraj, L.S., Kumar, R., Karthikeyan, P. Application of hybrid capsule network model for malaria parasite detection on microscopic blood smear images. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 1–27 (2024).

Prema, A.T., Santosh, P., Sakshi, G., Divya, B., Bhagyashree, G. Classification of blood smear images using CNN and pretrained vgg16: Computer aided diagnosis of malaria disease. In 2024 First International Conference on Technological Innovations and Advance Computing (TIACOMP), pages 349–354. IEEE, (2024).

Kumar, A., Nelson, L., Rasher, S. and Surendran, R.: Mosquitonet based deep learning approach for malaria parasite detection using cell images. In 2024 International Conference on Automation and Computation (AUTOCOM), pages 164–169. IEEE, (2024).

Manish, M., Singh, K.A., Ankit, B., Abhishek, B., Eshika, J., et al. Automated malaria detection using deep learning: A convolutional neural network approach for microscopic cell image analysis. In 2024 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), pages 1–6. IEEE, (2024).

Retinderdeep, S., Neha, S., Priyanshi, A., Mukesh, S., Ravi, C.K. Revolutionary changes in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia classification: The impact of deep learning convolutional neural networks. In 2024 2nd International Conference on Computer, Communication and Control (IC4), pages 1–6. IEEE, (2024).

Gokulkrishnan, N., Nayak, T. and Sampathila, N.. Deep learning-based analysis of blood smear images for detection of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In 2023 IEEE international conference on electronics, computing and communication technologies (CONECCT), pages 1–5. IEEE, (2023).

Tusar, M.T.H.K. and Anik, R.K.. Automated detection of acute lymphoblastic leukemia subtypes from microscopic blood smear images using deep neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.08992, (2022).

Muhamad, B.A., Esa, P.B., Teguh, S.R. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia image classification performance with transfer learning using cnn architecture. In 2022 4th international conference on biomedical engineering (IBIOMED), pages 30–35. IEEE, (2022).

Manohar, N., Raj, V.N.P., Tejaswini, N.N., Phanivarma, M., Jahnavi, G. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia classification with jetson nano. In 2024 2nd International Conference on Device Intelligence, Computing and Communication Technologies (DICCT), pages 249–253. IEEE, (2024).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. and Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2818–2826 (2016).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. and Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770–778 (2016).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Advances in neural information processing systems Vol. 25 (eds Pereira, F. et al.) (Curran Associates Inc, Red Hook, 2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the resources and support provided by CMATER Laboratory, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. This research work was supported by the ongoing FIST program of the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Jadavpur University, titled ‘FIST Engineering Sciences Level B/C/D Project’. The program is funded by the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, under reference number SR/FST/ET-I/2022/1059(C).

Funding

Authors did not receive any funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Asfak Ali. Conception and design of the study, development of the algorithm, and writing of the manuscript. Rajdeep Pal. Development of the algorithm, code implementation, conducting experiments, and analysis of results. Ishandeep Dey. Code implementation, analysis of results, writing of the manuscript and Document revision. Erik Cuevas. Conception and design of the study, preparation of figures and tables, and writing of the manuscript. Marco Perez-Cisneros. Analysis of results, writing the manuscript, and Document revision. Ram Sarkar. Analysis of results, writing, supervision,.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. No clinical validation involving human participants was conducted in this study; however, future work will aim to include clinical validation in collaboration with medical professionals to assess real-world performance.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, A., Pal, R., Dey, I. et al. DANet a lightweight dilated attention network for malaria parasite detection. Sci Rep 15, 36689 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20402-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20402-1